|

ROBERT WILLIAMS BUCHANAN (1841 - 1901) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

SITE DIARY

22 September 2024 Sorry, I have to start with this: |

|

|

It’s a cover of one of those print-on-demand ‘editions’ of out-of-copyright books. Nice that it’s Lady Kilpatrick as well since there are doubts as to whether Buchanan actually wrote the novel, although it was based on one of his plays. There’s an amusing sequence in the Chatto & Windus correspondence, where Buchanan tries desperately to stop the publication of the newspaper serialisation as a book, and finally has to admit defeat. ___ A faux-Soviet book cover is not the only strange thing I came across on ebay: |

|||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||

|

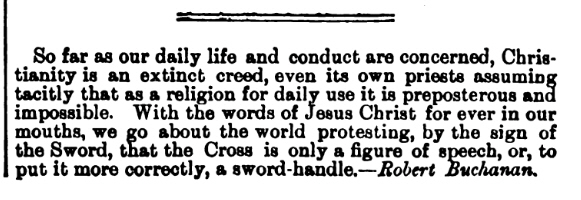

These are two of the actual film reels from the 1936 version of When Knights Were Bold. They were on sale for £395 and there are more details in the When Knights Were Bold Films section. ___ Enough of this nonsense. I have added Buchanan’s 1873 book of essays to the site: I know this is a bit redundant since I could just add a link to the copy at the Internet Archive (Hathi Trust, Google Books etc.) but, as I’ve explained many times before, when I started this site there was no Buchanan online, just some people moaning about the Fleshly School scandal, so I decided to put all his poetry and essays on this site, and so I will continue to do so. As for the essays, there’s only A Poet’s Sketchbook and A Look Round Literature to go, so I might as well finish the job. I promise I will not add the novels, although I did intend to do one of the plays this year, and I was all ready to purchase a copy from the British Library, when they were attacked by the hackers demanding ransom, which they refused to pay. This was last October, and I’ve just had another look at the site and it seems they’re still not completely back to normal. Anyway, just to add a note about Master-Spirits. It includes a section called ‘Scandinavian Studies’, one of which is ‘Danish Romances’, which was originally published in The St. James’s Magazine under the name of Newton Neville. This was the item which proved conclusively that ‘Newton Neville’ was one of Buchanan’s pseudonyms. In fact he had been using it since before he left Scotland. Master-Spirits also contains two pieces originally published under another pseudonym, ‘Walter Hutcheson’. Anyway, I thought it might be useful to list all of Buchanan’s and ‘Neville’s’ Scandinavian-inspired writings on a separate page, which I’ve called, rather unimaginatively, ___ I came across this from The Freethinker (8th August, 1897 - p. 509). |

|||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||

|

No idea where it originates - I thought it might be from the ‘Wandering Jew’ controversy, but I can’t find it. I suppose it could even be Buchanan’s father, but - 1897 - I doubt it. Thought it was neat, though and worth mentioning here. Another bit from The Freethinker (4th September, 1898) - although really commenting on a Buchanan piece in The Star (which is still unavailable online) with Buchanan supporting the bookseller who was prosecuted for selling Havelock Ellis’s The Psychology of Sex. |

|||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||

|

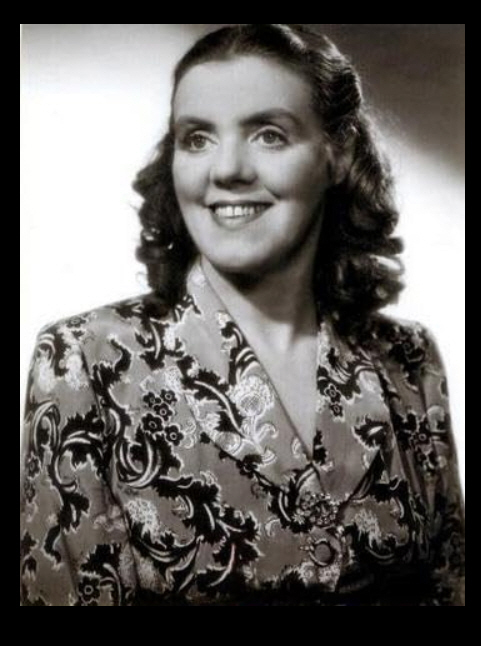

I’m always surprised when I come across admirers of Robert Buchanan. One such was Milton S. Stewart, whose book, Californian Sonnets and Poems, published in 1920, contains two poems in praise of Buchanan. Searching for more information about Mr. Stewart, I happened upon a sad tale, which I have recounted in the Miscellanea section. ___ And finally, back to ebay, and four more programmes for When Knights Were Bold. An early one (18th February, 1915) from the New Theatre, St. Martin’s Lane, London, with the James Welch Company, sans Mr. Welch, replaced on this occasion by Compton Coutts. I don’t have a review of this particular version of the play, but I do have photos of Muriel Kidner (Lady Rowena) and Doris Johnstone (Sara Isaacson). The New Theatre still stands, but its name was changed, twice in fact. This from wikipedia: ‘The Noël Coward Theatre, formerly known as the Albery Theatre, is a West End theatre in St. Martin's Lane in the City of Westminster, London. It opened on 12 March 1903 as the New Theatre and was built by Sir Charles Wyndham behind Wyndham's Theatre which was completed in 1899. The building was designed by the architect W. G. R. Sprague with an exterior in the classical style and an interior in the Rococo style. In 1973, it was renamed the Albery Theatre in tribute to Sir Bronson Albery who had presided as its manager for many years. Since September 2005, the theatre has been owned by Delfont-Mackintosh Ltd. It underwent major refurbishment in 2006 and was renamed the Noël Coward Theatre when it re-opened on 1 June 2006. The building is a Grade II Listed structure.’ The other three programmes are later and are all from Eastbourne (somebody’s having a clearout). The first from The Devonshire Park Theatre (17th November, 1947) with Leslie French as Sir Guy de Vere. Leslie French had a really long career. He was 94 when he died in 1999 and was still working (according to imdb) until 1994. One credit, which imdb choose to highlight, is his appearance in The Living Daylights as ‘Lavatory Attendant’. I must admit I can’t remember any details of his performance, whether James Bond’s visit to the Lavatory was of crucial importance to his mission. I have only seen the film once and, although I do like Timothy Dalton’s other appearance as Bond in Licence To Kill, I’m afraid The Living Daylights comes from that curious period when the cinematic heroes of the West (Rambo was also involved) were firmly behind the Afghan rebels who wanted to overthrow their Communist government (backed by Russia) and get rid of all those pesky equal rights for women. Maybe the Lavatory Attendant tried to persuade Bond of the error of his ways but was ignored. Still, we digress. The other name that stands out in the Devonshire Park Theatre production is Peter Bayliss as Wittle. I think I recall his name, more for the fact that I used to confuse him with Peter Sallis (of Wallace and Gromit fame), but checking out his page on imdb, I find he has a notable list of credits, including a brief appearance (not attending to a lavatory) in my favourite Bond film, From Russia With Love. The next programme is an amateur performance by St. Gertrude’s Amateur Dramatic Society at the Winter Garden Pavilion on 3rd and 4th February, 1950. And the final one is perhaps the most intriguing. It’s a production at the Royal Hippodrome from 31st December, 1951 by the Court Players, starring Frank Mitchell as Sir Guy de Vere. I have not been able to find any information about Frank Mitchell, unless - and this will require much searching on the British Library Newspaper Archive site, when my finances have improved - he is the American actor of that name. There was a practice in the 1950s to bring B-list or C-list actors over from Hollywood to star in the cheap British films needed to fill the quota system. These were usually crime dramas, mostly set in London (an inordinate amount around Teddington Lock). There’s no evidence that the American Frank Marshall ever made a ‘quota-quickie’, or ever came to England, for that matter. But I shall investigate further. The other interesting thing about the Court Players’ production is that it includes two names which I was familiar with: Marjorie Rhodes, whose speciality was put-upon housewives or weary mothers, |

|||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||

|

and Delphi Lawrence, who was of much posher bent, and who played Lady Rowena in 1951. The photo below is not from that production and is certainly not how I remember her (the saucy minx), but I thought I would risk frightening the horses. |

|||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||

|

5 April 2024 God Damn the Pusher Man I forgot to mention a couple of things in the last update. Firstly, this brief account of the Fleshly School affair from the man who introduced Dante Gabriel Rossetti to the ‘benefits’ of chloral, from The Autobiography of a Journalist by William James Stillman. And I also added a page about the movie actress/producer and star of the silent film version of Alone in London, Florence Turner. The Stillman piece made me take another look around to see if there was anything else on the Fleshly School front which I’d missed. I found these: 1. Buchanan’s essay makes Grace Lavery’s Reading List of Queer Treasures at the Literary Hub: Robert Buchanan, The Fleshly School of Poetry Meanwhile another of Gilbert’s influences was a strange and more manically phobic tract of a different sort: Robert Buchanan’s 1871 essay “The Fleshly School of Poetry,” which issued a slew of anxious insults against Dante Gabriel Rossetti, whom Buchanan labeled “an intellectual hermaphrodite.” Interestingly, Buchanan’s sense of Rossetti’s effeminacy connected to Rossetti’s famous heterosexual incontinence—it was as though having sex with all those girls had turned him into one. Buchanan’s Rossetti is trans lesbian avant la lèttre, a person whose reprehensible feminization threatened the sexual order of things—and yet again, the zealot concealed a secret desire, as Buchanan admitted after Rossetti’s death, in a poem entitled “To an Old Enemy,” in which he imagines giving him “a lily-flower,” a symbol of erotic tenderness. 2. ‘The Fleshly School of Comedy: Similarities Between Buchanan’s Criticism of the Pre-Raphaelites and Punch’s Mockery of Aestheticism’ at Victorian Culture and Thought. 3. ‘D. G. Rossetti, Browning, A Pair of Harlots, & the Fleshly School of Poetry’ a lecture by Tom d’Egidio, given at the New York Browning Society at the National Arts Club on Wednesday, October 16, 2019. If you want to skip to the section about Buchanan (“the completely forgotten poet”), that’s around the 44:40 mark, but you’ll miss the opening comments by a very enthusiastic M.C.

|

|||||||||||||||||||

|

Eh up! Not being one to ignore new technology (although I haven’t got one of those mobile phone thingies yet) I thought I’d try an AI essay writing programme to see what it would make of ‘Robert Williams Buchanan (1841 - 1901)’. I requested a 1,000 word critical essay from MyEssayWriter.ai and this is what I got: ‘Robert Williams Buchanan was a prolific poet, playwright, and novelist, born in 1841 in Caverswall, Staffordshire, England, and passed away in 1901. He was a significant figure in Victorian literature, although his reputation has fluctuated over the years due to the controversial nature of his works and his public persona. Buchanan’s writing explores themes of social injustice, moral degradation, and the complexities of human nature, making him a keen observer of the society in which he lived. This essay will delve into the life and works of Robert Williams Buchanan, shedding light on his contribution to English literature. Buchanan’s early life was marked by hardship and poverty. He grew up in Glasgow, Scotland, where his father worked as a journalist. Despite financial struggles, Buchanan showed early promise in writing and was determined to make a name for himself in the literary world. He studied at the University of Glasgow and later relocated to London to pursue his career as a writer. One of Buchanan’s most famous works is the poem sequence titled “Sonnets of the Portuguese,” inspired by his love for a woman named Mary Jay. These sonnets are regarded as some of his best poetic works, showcasing his lyrical prowess and emotional depth. Buchanan’s ability to capture the complexities of love and desire in his poetry set him apart as a poet of great skill and sensitivity In addition to his poetry, Buchanan was also known for his plays and novels, which often tackled controversial subjects such as prostitution, poverty, and the hypocrisy of society. One of his most controversial plays, “Lady Clare,” caused a scandal due to its depiction of a fallen woman seeking redemption. Despite the backlash he faced from critics and the public, Buchanan remained steadfast in his commitment to addressing social issues in his writing. Buchanan’s writing style is characterized by its intensity, vivid imagery, and intricate use of language. He was a master of wordplay and metaphor, weaving complex narratives that drew readers into his world of moral dilemmas and societal injustices. His writing is marked by a sense of urgency and passion, reflecting his deeply held convictions about the need for social reform and moral introspection. Despite his talent and dedication to his craft, Buchanan’s reputation suffered in later years due to his outspoken views and confrontational nature. He engaged in public feuds with other writers, including Algernon Swinburne and Dante Gabriel Rossetti, which tarnished his image in literary circles. However, his literary legacy remains intact, with scholars recognizing his contributions to Victorian literature and his unique voice in addressing pressing social issues of his time. In conclusion, Robert Williams Buchanan was a complex and multifaceted figure in Victorian literature. His works continue to intrigue and challenge readers with their exploration of love, morality, and societal norms. While his reputation may have waned in recent years, his place in the canon of English literature is secure. Buchanan’s ability to capture the human experience with honesty and insight makes him a master of his craft, deserving of further study and appreciation. In summary, Robert Williams Buchanan was a remarkable figure in Victorian literature, with a rich body of work that delves into the complexities of human existence. Despite facing criticism and controversy during his lifetime, his writing continues to resonate with readers today, offering profound insights into the societal issues of his time. Buchanan’s legacy as a poet, playwright, and novelist is a testament to his talent and dedication to the craft of writing. His works deserve to be explored and celebrated for their enduring relevance and literary merit.’ It starts well, recognising that his birthplace is in Caverswall, Staffordshire, which is more than Harriett Jay does in her biography of her brother-in-law. The next bit’s ok, but a bit woolly, and I’m not sure whether Buchanan’s reputation fluctuated over the years, or just plummeted headlong after his death. The second paragraph starts with a mistake. Obviously all Victorian authors, especially those growing up in Glasgow, must perforce have had a hard, poverty-stricken life (I’m surprised Mr. AI didn’t send him up a chimney), but Buchanan’s early life was fairly comfortable, especially after the move to Glasgow when his father was a newspaper proprietor (not just a journalist). The financial struggles didn’t begin until his father’s bankruptcy and Buchanan’s move to London. “His works deserve to be explored and celebrated for their enduring relevance and literary merit.” _____

24 March 2024 Well, that was a gap. I had intended to do an update at the end of last year, but things got complicated around Christmas, so I thought I’d leave it till January. Then I was down in London for a few days at the end of January, so I thought I’d take the opportunity to visit Robert Buchanan’s house in Hampstead - something I’d been meaning to do for years - so now it’s the end of March. So, sorry about that, but I don’t actually think people are waiting on tenterhooks to see what has been happening in the crazy world of Robert Buchanan - there’s been no mention of it on the news, anyway. Let’s get on. 1. I Visit 25, Maresfield Gardens I’ve put a full account of the visit in the Miscellanea Section, here: The way I’m going on about this seems to be implying that one can visit the house and see where Robert Buchanan spent his days during the height of his fame, and mayhap sit on his sofa and peruse his library. Banish that thought - you can do all that, over the road at No. 20, which is the Sigmund Freud Museum. 25, Maresfield Gardens still stands and you can go and look at it, and for some of us, that’s enough. 2. Mormons Not because I’ve just finished watching Under The Banner Of Heaven - strange, very strange - but because I came across a mention of Buchanan’s St. Abe and His Seven Wives in an article in the Journal of Mormon History (Volume 34, Issue 1 - Winter 2008): “The Assault of Laughter”: The Comic Attack on Mormon Polygamy in Popular Literature 3. Truth ... ... is the journal which keeps on giving. I’ve been adding a few more reviews and items about Buchanan, among them this review of Sweet Nancy which begins: ‘It is quite clear to my mind that Mr. Robert Buchanan writes too much.’ And doesn’t end much better: ‘When “Nancy” has been properly edited and prepared for stage production it may do; but after its trial trip on the measured mile it wants a considerable amount of overhauling. There is something wrong with the safety-valve, and it should be put into dock for repairs before it can safely go on a long cruise.’ Presumably the overhauling was done since Sweet Nancy was still touring the provinces in 1908 - 18 years later. There were also bad reviews in Truth of The Struggle For Life and The Sixth Commandment and a follow-up to both of these in which Buchanan finds himself among some strange bedfellows: ‘The public voice has pronounced unanimously against Ibsen, against Zola, against Daudet, and against Robert Buchanan.’ And it all ends with a GBNews-style cri de cœur: ‘At present we want no more Russian novels by unpronouncable authors. Our own novelists and dramatists are good enough for us for the time being.’ There was also a poem in Truth about Buchanan’s poem, The Outcast, or at least about Buchanan’s reaction to criticisms of it: Truth (17 September, 1891 - p.7) TO MR. ROBERT BUCHANAN. The best of the critics, you shrilly complain, It is true from your language you seem to protest, Yes, the public believe that so long as you fail And finally, I spotted this. which appeared just above the poem: |

|||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||

|

Absolutely nothing to do with Robert Buchanan, but I’ve just been watching a lot of Tyrone Power films lately, so it is merely a coincidence. As is this: |

|||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||

|

4. Philip Woodville vs. Svengali I recently read Captivated: J M Barrie, the du Mauriers & the Dark Side of Never Never Land by Piers Dudgeon and a couple of things struck me. Buchanan wasn’t mentioned, of course, but he must have known Barrie. I think the only direct connection between the two was the letter Barrie wrote on 26th November, 1900, supporting Buchanan’s application for financial support from the Royal Literary Fund following his massive, incapacitating stroke. Then there was the coincidence of Buchanan’s Ibsen spoof, The Gifted Lady (aka Heredity) being produced at the same time as J. M. Barrie’s Ibsen's Ghost, or Toole Up-to-Date (which, of course, got better reviews). Reading books about the ‘goings-on’ in London’s literary world around the same time as Buchanan was active, does make you feel that he was very much the poor relation, or the eternal outsider. Reading Captivated, odd names keep cropping up, Walter Besant, Edmund Gosse, minor characters, but seemingly fully-engaged in the exciting world of the Du Mauriers, but Buchanan is never there, he always seems to be sat at home with Harriett and his mum. Anyway, what did intrigue me most about Captivated as it applied to Buchanan was the mention of Herbert Beerbohm Tree and his appearance in the play of George Du Maurier’s Trilby, as Svengali. |

|||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||

|

Herbert Beerbohm Tree as Philip Woodville in The Charlatan. Herbert Beerbohm Tree as Svengali in Trilby. |

|||||||||||||||||||

|

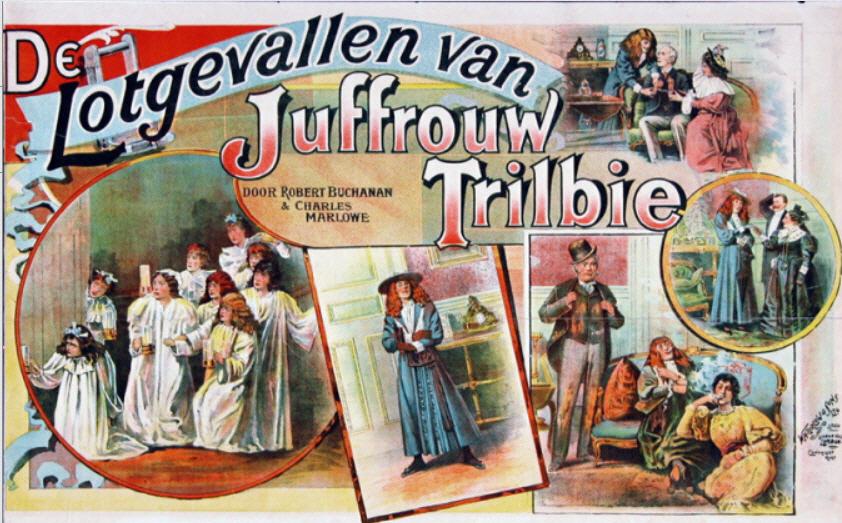

The review of The Charlatan in Truth begins with a thinly veiled accusation of plagiarism on Buchanan’s part, citing ‘Hypnotised’, an anonymous shilling shocker, and Alexandre Dumas’ Joseph Balsamo, as possible sources. Quite possible if the latter, and ‘Joseph Balsamo’ (aka Cagliostro) would be a character in Buchanan and Jay’s ‘final’ play, The Diamond Necklace, written for Lily Langtry and unproduced by that lady. The Truth review ends with the following: ‘I do not remember that hypnotism has ever before been used for the purposes of the drama. It is the fashionable craze of the moment, in conjunction with Theosophy, now that cabinets and roped men and table-turning and slate-messages and jerked tambourines have gone out of fashion. Possibly the “Charlatan” will attract as a play of curiosity. Whatever Mr. Beerbohm Tree does is interesting, and he has a following who believe that the last thing he does is the best thing he has ever done in his artistic life.’ The Charlatan had a three month run at the Haymarket Theatre from January 18th to March 17th, 1894. In contrast, Herbert Beerbohm Tree’s production of the Paul M. Potter adaptation of Trilby is one of his greatest successes. After a brief tour of the provinces it opened at the Haymarket in London on October 30th, 1895. One wonders if Buchanan would have had a greater success with The Charlatan if he’d given full rein to his melodramatic, Alone in London, side and made Philip Woodville an out-and-out villain rather than a more nuanced, anti-hero. I feel that, since plagiarism has been mentioned, I should specify the dates of The Charlatan, which took to the Haymarket stage on 18th January, 1894, and the first appearance of Trilby as a serial in Harper’s New Monthly Magazine in January, 1894. A coincidence, then, nothing more. Another coincidence is the fact that Buchanan’s Dick Sheridan nemesis, Paul M. Potter, was the playwright who adapted Trilby for the stage. And a final, rather strange one. Here is the poster for the Dutch production, at the Tivoli Theatre, Rotterdam, in December, 1895, of The Strange Adventures of Miss Brown, which had been renamed The Adventures of Miss Trilbie. |

|||||||||||||||||||

|

|

Still on The Charlatan (and a lot more to come), The Trilby Phenomenon and Late Victorian Culture by ‘The title of The Charlatan (1895), by Robert Buchanan and Henry Murray, does not permit the reader any question about the nature of the main character’s talents. Having wielded his critical pen against the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood in his notorious 1871 Contemporary Review article, “The Fleshly School of Poetry,” Buchanan aimed, with the publication of this novel, to provide an explicit contribution to “the elimination of humbugs and charlatans from the ranks of the faithful” (n.p.). Although the “Note” at the beginning of the novel insists that “’The Charlatan’ is not an attack upon theosophy nor a satire against hypnotism” (n.p.), Theosophy and hypnotism certainly bear the brunt of Buchanan and Murray’s satirical ire. Woodville, a celebrated Theosophist and guest at the home of the Earl of Wanborough, is without doubt the charlatan of the title. Unlike the narrative strategy of Herr Paulus. which requires the reader to wait for several hundred pages before Paul’s cheating ways are revealed, The Charlatan explains Woodville’s imposture even before he arrives on the scene. In a sort of soliloquy, Madame Obnoskin, his partner in crime, reveals their plan to take advantage of the Earl. Woodville’s plans also include revenging himself upon Isabel Arlington, the beautiful if relatively poor daughter of Colonel Arlington, who has gone missing in India. Isabel and Woodville share the secret of their past relationship in India. Although Isabel was then attracted to Woodville, her companions convinced her to reject him. As Woodville explains, Once I thought I had won her heart. Had I, indeed, done so, I would have been her servant, her slave, till life was done. Then, through the calumny of evil tongues, she learned to despise me. She drove me from her with insult. I pursued her; I accepted humiliation upon humiliation. Her door was closed in my face. My letters were returned unopened. At last, to avoid me, she came to England. I followed her; and I am here! (101-102) Woodville’s plans hit a snag, however, when he encounters Isabel one night, in a hypnotic trance. She has sleepwalked onto the terrace and from there wends her way to the turret room in which he is staying. When she admits, in her somnambulant state, that she loves him, Woodville cannot bring himself to take ruthless advantage of her vulnerability: Aware of his evil command over her, he had expected to find himself face to face with a helpless, will-less woman, spell-bound beyond the power of resistance, physical or moral—a woman who, in her waking moments, felt for him nothing but distrust and even dread, and who, even when hypnotized and powerless to resist him, would be conscious only of a dull, numb sense of pain. How different was the reality! Had he been her dearest and nearest friend, instead of her most dangerous enemy, the sound of his voice could not have awakened in her a more subtle sense of pleasure. (163-64) Moved by “the girl’s perfect trust and utter surrender, her complete unconsciousness of any evil, her helplessness, her divine gentleness and affection” (167), Woodville packs her off to her own bedroom in an effort to avoid impugning her reputation. I also came across a review of The Charlatan by Willa Cather from the Nebraska State Journal of 25th March, 1894. Willa Cather also had this to say about a novel of Buchanan’s according to this note:: ‘In one of her weekly columns for the Journal during 1896, Cather observes that "It is strange that from Felicia down, the stage novel has never been a success....The last and best of these futile attempts is by Robert Buchanan and is called Diana's Hunting."’ And, to bring this section to an end, and going back to how it began with J. M. Barrie, I finally tracked down his article about the Literary Ladies Dinner of 1889 in the Scots Observer. I also found another review of the event in the Saturday Review. 5. Oscar Wilde (and The Charlatan) I warned you there’d be more. In Oscar Wilde as a Character in Victorian Fiction by Angela Kingston (Palgrave Macmillan US, 2007) there’s a section about the character of Mervyn Darrell in The Charlatan and his possible resemblance to Oscar Wilde. Darrell was played by Frederick Kerr, who, a year later, was to have a greater success with a Buchanan and Jay, playing the title role in The Strange Adventures of Miss Brown (or Trilbie to the Dutch). Mervyn Darrell’s similarity to Oscar Wilde was mentioned in some contemporary reviews, including this from Freeman’s Journal: ‘Mr Frederick Kerr as the Hon Mervyn Darrell gave one of those character sketches in which he excels. The Hon Mervyn Darrell is an exponent of the new spirit, and he indulged in numerous paradoxes of the usual description which no one seemed to enjoy more than Mr Oscar Wilde, who sat in the second row of the stalls.’ Angela Kingston discusses the relationship between Buchanan and Wilde and mentions that Wilde sent Buchanan a copy of The Picture of Dorian Gray. To which Buchanan replied with this letter: Merkland My dear Oscar Wilde, I ought to have thanked you thus for your present of Dorian Gray, but I was hoping to return the compliment by sending you a work of my own: this I shall do in a very few days. You are quite right as to our divergence, which is temperamental. I cannot accept yours as a serious criticism of life. You seem to me like a holiday maker throwing pebbles into the sea, or viewing the great ocean from under the awning of a bathing machine. I quite see, however, that this is only your “fun,” & that your very indolence of gaiety is paradoxical, like your utterances. If I judged you by what you deny in print, I should fear that [you] were somewhat heartless. Having seen & spoken with you, I conceive that you are just as poor & self-tormenting a creature as any of the rest of us, and that you are simply joking at your own expense. With thanks & all kind wishes Oscar Wilde Esq. This letter is published in Oscar Wilde Revalued: An Essay on New Materials and Methods of Research by Ian Small (ELT Press, 1993) (p.81.). I’d never seen it before - so thanks to Angela Kingston and Ian Small - and I’ve added it to the Published page in the Letters Section. Note the date of its first publication. I’ve been doing this site for over 20 years now. You know my description of Buchanan as the poor relation, when it comes to the world of academia, I feel a bit like that myself. I think I’ll leave it there. _____

14 October 2023 So, I was going through the material culled from the BLNA and, through a complicated set of coincidences, realised that a key anti-Buchanan text was now available. I had mentioned it before in the Letters to the Press section, but it was just referred to in other newspapers. Now it’s available in its full glory: Written by George Moore, this attack on Buchanan was published in Truth on 4th April, 1889. Its title referred to Buchanan’s letter to The Daily Telegraph of 22nd March, ‘Is Chivalry Still Possible?’, but its real object was to reply to Buchanan’s article in the Universal Review, ‘The Modern Young Man As Critic’. Buchanan responded with another article in the same journal, ‘Imperial Cockneydom’, and George Moore came back with ‘No! Buchanan Is Not Still Possible!’ Both Universal Review essays were included in The Coming Terror and those are the versions which have been on this site for some while now. However, when I read the second of George Moore’s ‘Possible’ pieces, I realised there were differences between ‘Imperial Cockneydom’ in The Coming Terror and the Universal Review original. For example there is this long explanation of the Fleshy School affair, which Buchanan then cut from the later version: ‘If I were to tell in full detail the story of my own persecutions on account of a single expression of opinion the world would open its eyes . My offence was criticising a body of writers whom I believed to be extravagantly praised, but whom I should never have attacked on literary grounds alone, if I had not, rightly or wrongly, fancied them to be offenders against the higher ideals of their generation. This article, published in the Contemporary Review, met with a mixed reception. All the puritan world (with which I had little sympathy) approved it, many artistic notabilities sympathised with it, but a noisy Cockney clique, commanding the bastions of nearly all the critical journals, resented it—and swore to avenge it. Now, it contained not one syllable which had not been expressed viva voce by men of accepted eminence, by Carlyle, by Emerson, and by others equally famous who are still living and whom I need not name. It was a hasty article, a frivolous article; in some respects, as I acknowledged afterwards, an unfair and uninstructed article; but no portion was half as violent and hasty as the normal criticisms on contemporaries of some of the writers satirised. I had, however, committed the one unpardonable sin—attacked the gods of Nepotism. Thenceforth all Nepotism was armed against me. I do not exaggerate when I say that my very life, my very means of subsistence, was threatened, and had I not been a strong man I should have been crushed and destroyed. Nearly every critical journal persistently attacked or ignored me, until the matter became so serious that it became inexpedient to publish any work under my own name. Tongue cannot tell, words cannot convey, the extent of this persecution. My very life and private character were not spared. I wrote certain novels; it was because I had ‘failed’ in literature. I wrote for the stage; it was because I had ‘failed’ in fiction. Not even Carlyle, when he was ‘cut’ by Mill because he was ‘reported’ to have made a certain little joke, suffered more torture. I, who had all my life been the friend and helper of my fellows, was described as a bitter, an envious, and a hateful person—a Tartuffian Scotchman. 1 Yet, curiously enough, I survived. My books, my failures, were being read in every English speaking country. While the small gods of Nepotism were still avowing that I had done nothing, I had written inter alia ‘Balder the Beautiful,’ ‘The Shadow of the Sword,’ ‘God and the Man,’ ‘White Rose and Red,’ ‘St. Abe,’ and ‘The City of Dream,’—works on which I am quite content to take my stand when I am brought face to face with the shadowy Rhadamanthus, the Arch-Destroyer of Cockneys, Posterity. My point here is, that nine writers out of ten would have been silenced by the clamour of the cliques of Nepotism. That I was not — 1 I cannot, as I have pointed out, even claim that national distinction, though I am, I am proud to say, Scotch on the paternal side. — silenced, was due to three facts—that I had always had a very low opinion of merely ‘literary’ persons, that I was a man of the world, in the habit of rubbing shoulders with all classes of people, and that, on the whole, I attached very little value to popular opinion. ‘Woe to you when the world speaks well of you,’ was a dictum echoed in my heart very constantly. I knew that to be frank, and fearless, and free, was not the way to ‘get on’ with worldlings. Above all, I never posed before my own looking-glass as a martyr, felt no self-pity, but when I received a blow took it as one I had doubtless earned. Writing for the stage was for me, I may say in this connection, a sort of moral salvation; with its Bohemianism, its rough and ready manliness, its necessity for practical good humour and friendliness, it saved me from becoming a literary ‘prig’; it made me familiar with a world which, with all its faults, is lighthearted, gladsome, and not too conceitedly ‘intellectual.’ One loves actors, when one knows them well, for their simplicity and innocence of character. The social sympathy which follows them may be (to quote one of my young men) ‘Mummer-worship,’ but it is the wise and unerring sympathy of generous human nature, which knows that for earnestness, for catholicity, and above all, for personal ‘charm,’ the heirs of Betterton and Garrick compare favourably with the followers of any profession under the sun. Perhaps, if he had not been bred a ‘mummer,’ Shakespeare would never have learned his way so easily to the intellects and the souls of men. It is wise, no doubt, to ‘humour one’s reputation’—a fragment of Cockney gospel which the late George Lewes was ever fond of quoting. The more varied a man’s gifts and sympathies, the more difficult is his road upward. But let any young writer, conscious of his power yet fearful of his contemporaries, only survey the history of literature, and take comfort . It is never—well, ‘hardly ever’—the man whom Cockneydom praises that rises in the end to genuine eminence, to the sad sunless aureole of Fame. Cockney Nepotism is a little chamber, hot, ill-ventilated, full of noisy chatter; but outside, is the busy storm of Life, and far above, the silence of the patient heavens. Inside, John Dennis, Hazlitt, Gifford, and Mr. Andrew Lang; outside, in the open air, Shakespeare and Milton, Wordsworth and Coleridge, Schiller and Heine, Balzac and Victor Hugo, and, whether greater or smaller, thousands more.’ Perhaps Buchanan decided in the three years between the original ‘Imperial Cockneydom’ and the publication of The Coming Terror, there was no need to drag the whole sorry saga out again and so he dropped this passage. However I think it worth noting that he does write, ‘the matter became so serious that it became inexpedient to publish any work under my own name’, which I still believe is not strictly true, but which has become the generally accepted reason for the anonymity of his ‘American’ poems and the various things he wrote while editing The St. Pauls Magazine. St. Abe was already being advertised, as an anonymous work, by Strahan on 30th October, 1871, long before Buchanan had been confirmed as the writer of ‘The Fleshly School’ article, and as for the St. Pauls material, whenever Buchanan was editing a magazine, it was his practice to fill it with anonymous or pseudonymous work written by himself - that went all the way back to his first job, editing The West of Scotland Magazine and Review in 1859. Anyway, I transcribed the original version of ‘Imperial Cockneydom’ so both versions are now on the site (Universal Review and The Coming Terror).. I did wonder whether I should add a separate section for all the George Moore material. Buchanan had earlier objected to George Moore’s criticism of Sophia in articles in The Evening News in December, 1887 and had sued the newspaper for libel. In November, 1889 The Fortnightly Review published an essay by George Moore entitled ˜Our Dramatists and Their Literature’ which criticised Buchanan and led to a further spat in the papers. In a way, it is a shame that the two did not get along, especially since they both defended Henry Vizetelly. But, in a way, that echoed the earlier championing of Walt Whitman when both Buchanan and Michael Rossetti were the strange bedfellows. For those wishing to find out more about George Moore, I direct you to The George Moore Association. Which led me to George Moore Interactive At present only a blog, but in the future who knows? I thought I was ambitious when I started this site, hoping to resurrect the reputation of Robert Buchanan (how’s that going, Pad?), whereas Dr. Robert S. Becker, of Oak Park, Illinois, seems intent on resurrecting George Moore himself. Not in some scary Frankenstein fashion (“It’s alive!”) but more in the current A.I. scary fashion. He hopes to reconstruct George Moore’s voice, although no known recording exists, and will presumably also create an avatar based on the numerous portraits of Mr. Moore - a rather odd-looking cove. Dr. Becker outlined his plans in a lecture entitled “Kick-Starting Literary Legacies in the Digital Age”, which he gave at the Oak Park Public Library on 25 February 2023, the full text of which is available on his fascinating site. |

|||||

|

|||||

|

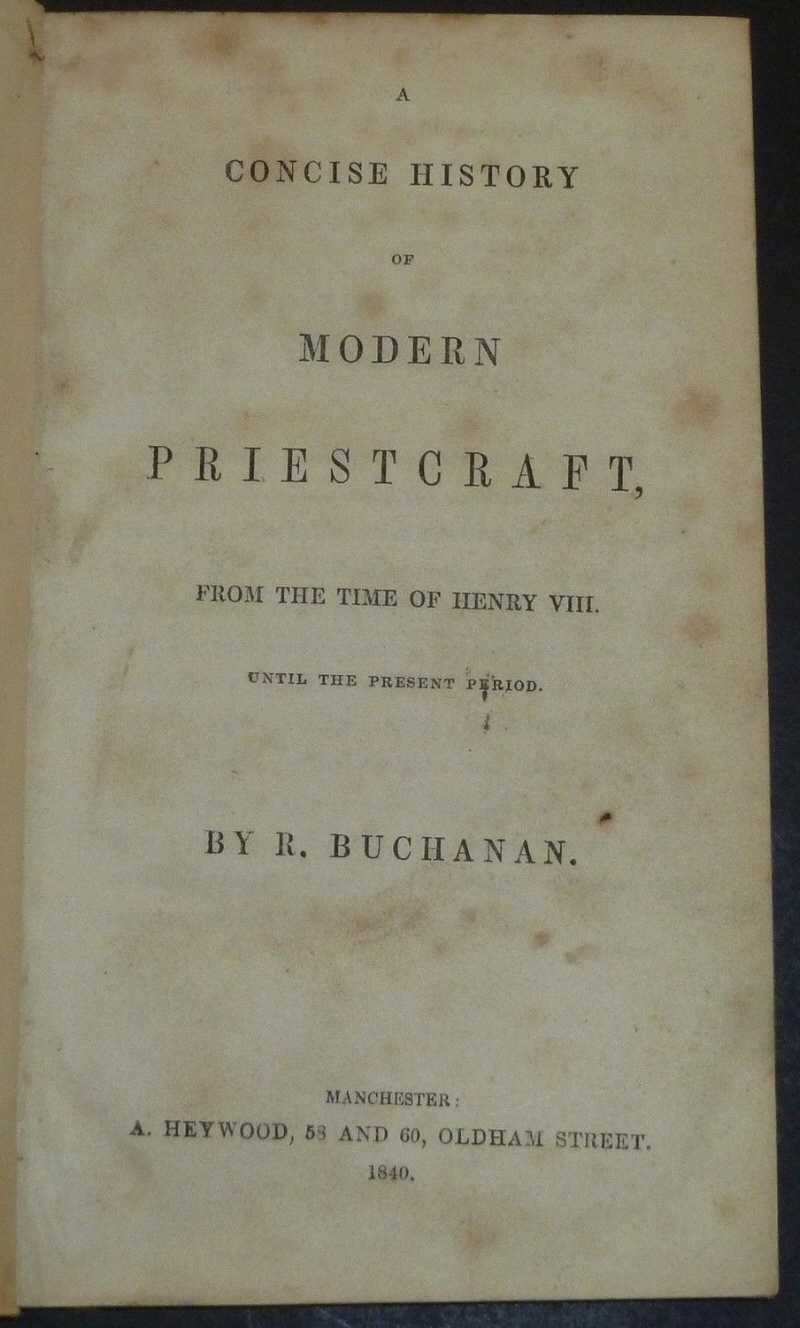

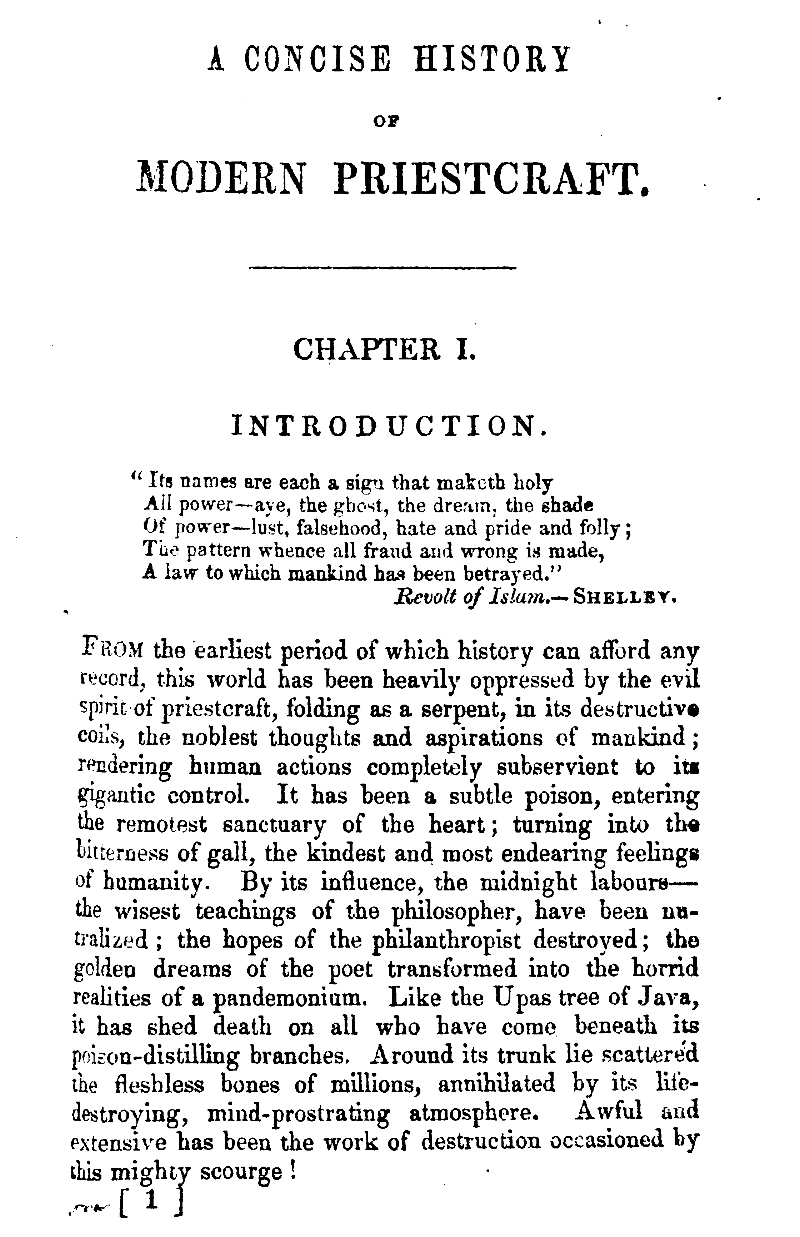

[George Moore by Walter Sickert] ___ I also found some particularly juicy reviews of Buchanan plays in Truth. This is how they open their appreciation of Alone in London during its London premiere season in November, 1885: ‘There may be some faint and lingering doubt concerning the capacity of Robert Buchanan to write plays, but there surely cannot exist, even in the author’s enthusiastic brain, a hope that ever again will comely Miss Harriett Jay be enabled to enact “a waif.” A more substantial, portly, and apparently well-fed beggar was surely never put forward to enlist our sympathies. Anything more unlike a starving boy, anything less resembling a ragged outcast than this handsome, shapely lady never occurred to any one but the manufacturer of realistic drama. There is not a trace of the characteristics of a boy about this pseudo-pathetic chickweed-and-groundsel seller, with his well-favoured limbs and shambling gait. His attempted snivel and continual crawl have apparently been introduced for the mere purpose of showing how utterly unlike life are the stock characters in modern realistic drama. As a clever writer has already pointed out, the much-persecuted but equally well-favoured Miss Amy Roselle is not “Alone in London” at all, for she is perpetually followed by the epicene vendor of chickweed, who crawls about the floor of the stage, and spoils every situation in what—but for the wearisome boy—might have been made an effective drama. But the truth should be told about realism as applied to modern art on the stage. The well-nurtured and bright-eyed waif is not the only blot on a series of characters and pictures that are about as unlike life in the East-end, or the West-end, as any that could be possibly conceived.’ In October 1899, reviewing a revival at the Princess’s Theatre, their opinion does not seem to have changed much during the intervening fourteen years: “‘Alone in London’ has seen the footlights upon more than one occasion. It is the work of Mr. Robert Buchanan, and about on the level of his poetry. A detailed account of this pasteboard production would be out of place. ... The water of the floodgates also did what it could to atone by its absurdity for the obviousness of the proceedings. So far as one could see from the stalls, it consisted of a large table-cloth violently agitated by many hands, from under which emerged eventually Mr. Cooper triumphant in his shirt sleeves. Here there is no vile plagiarism of the real water of Drury Lane. And then there’s this review of Fascination which begins: “Modesty is not one of the strong points of the poet Buchanan. He is one of the “cock-sure” school. He alternately cringes to and abuses his critics, and bolster-up ever failure with bunkum and bombast. If ever man were treated well by those he habitually libels it is the poet Buchanan, whose “Sophia” has been justly praised as a capable and enduring bit of stage work, and whose recently-produced “improbable comedy” has been treated in many quarters with exceptional charity. It is only necessary to read a recently-published “interview,” full of gratuitous impertinence towards the profession by which he lives, and the journalists who advertise him beyond his merits, to see how ignorant the man is of everything connected with stage work. “Fascination” is a case in point. A good idea is hopelessly spoiled by vulgarity of treatment and ignorance of what the stage really requires. The poet Buchanan, as a humourist, is as clumsy as a bull in a china shop.“ ___ Going back to that statement about the Fleshly School in the Universal Review article, and Buchanan’s mention of his love of the theatre, I also came across more evidence of that in an article he wrote for The People (11th March, 1888) under the title: ‘Plays and Players: Some Early Recollections’. ___ And with the ‘Holy Land’ once more embroiled in vicious war, it seems apposite that Robert Buchanan Snr.’s 1840 work, A Concise History of Modern Priestcraft, from the Time of Henry VIII until the Present Period (Manchester: A. Heywood, 1840, 172 pp.) is now available on Google Books (or download it here). Here’s the title page and the first page of the Introduction. |

|||||

|

|

|

10 August 2023 Mary Buchanan’s Photograph Album I’ve had a selection of pages from Mary Buchanan’s Photograph Album on this site for a few years, but it’s now online in its entirety at its final resting place - the Armstrong Browning Library of Baylor University, Waco, Texas. I’ve left my original, cut-down version, on this site since it does include some additional notes which may be of interest. Also, from the same source, came two more pieces of the Browning/Buchanan correspondence - two letters from Robert Browning - which I’ve now inserted among the Alexander Turnbull collection, both from 1869, one from January, the other from 20th March. And, for the Miscellanea section, some passing mentions of Robert Buchanan in the correspondence of Edward Dowden and his future wife, Elizabeth Dickinson West. ___ More from the BLNA I’ve also been back to the British Library Newspaper Archive to see what’s appeared there since my last visit. Some items of note: T. P. O’Connor’s speech following his unveiling of the Buchanan memorial in St. John’s Churchyard in Southend. This is from the July 30th, 1903 edition of The Southend Standard, which also contains this discussion at a meeting of the Westcliff Ratepayers’ Association on the subject of ‘Free Libraries’. Plus ça change. Various items, again from Southend newspapers, relating to the Buchanan Memorial and the grave of Robert Buchanan, including a Harriett Jay interview, reviews of the performance of Night Watch and Sweet Nancy to raise money for the Memorial and a report of a prizegiving ceremony at Southend College for Girls where Harriett Jay distributed the prizes and addressed the girls. There’s also an advert for the Sweet Nancy performance and on the same page of The Southend Standard of 3rd April, 1902 I spotted this. |

||||||||

|

||||||||

|

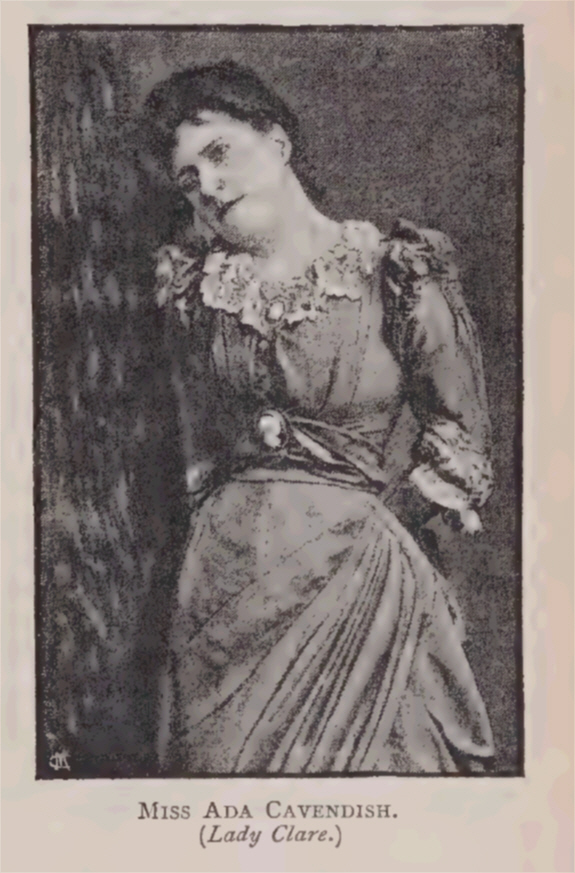

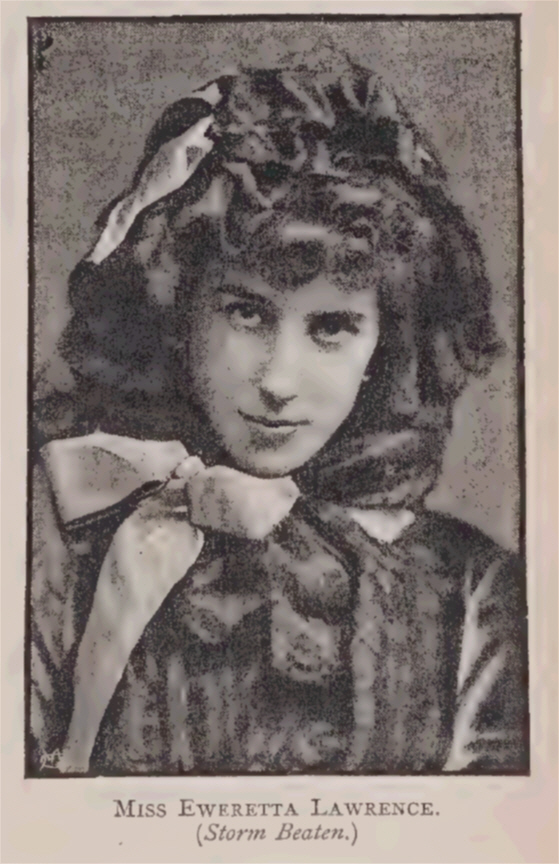

There are also some more reports of ‘Buchanan Day’, which was celebrated on the anniversary of his death with a small ceremony at the gravesite. These petered out over the years and the last report I found was for 1913. ___ Theatre Reviews Talking of Sweet Nancy, I found George Bernard Shaw’s review of the play in The Saturday Review. And talking of Theatre reviews, there are some beauties from Truth, especially that of Lady Clare which begins: “Robert Buchanan has clearly proved that he is no dramatist. He has not studied the stage; nor does he understand it. His characters are as feeble and insipid as his situations are tawdry and commonplace. His Adelphi drama of “Storm-Beaten” is a noisy, exaggerated, over-coloured succession of unconnected scenes; his Globe play of “Lady Clare” is a thin, nervous, amateurish work, in which some of the finest dramatic positions of recent modern plays have been used, apparently to show how they can be spoiled by a bungling workman. Having, in “Storm-Beaten,” demonstrated how incapable he was to dramatise his own novel, Buchanan, in “Lady Clare,” shows how he can dramatically ruin the book of a contemporary novelist.” I feel I should point out that Truth was the magazine of Henry Labouchère, which Buchanan had satirised in his 1882 novel, The Martyrdom of Madeline: ‘What, don’t you know him? That’s Lagardère of the “Plain Speaker.”’ A lie which is all a lie can be met with and fought with outright, Lagardère has achieved the complete art of so mingling truth and falsehood together that it is impossible even for himself to distinguish the one from the other. What wine will you take?’ This was a continuation of Buchanan’s original attack on the ‘society journals’ in his essay, ‘The Newest Thing In Journalism’, published in The Contemporary Review in September, 1877. The Truth review of A Sailor and His Lass is equally amusing, although the reviewer’s acid in this case is mostly hurled towards Augustus Harris. I also came across another interesting review of the play in The Athenæum which compared Robert Buchanan to Emile Zola: “Mr. Buchanan has gone further and put on the stage a dancing saloon in Ratcliffe Highway, crammed with drunken sailors and shameless women, and has depicted the details of an execution in Newgate. No touch of sentiment is there to elevate one at least of these scenes. Before the arm of a bouncing virago the half-tipsy sailors in the dancing saloon drop like ninepins. This scene, moreover, is unneeded, and is introduced for no reason beyond the expectation that it will hit the public taste. In favour of the picture in Newgate it may be urged that the convict is innocent, and that a species of sympathy is thus inspired on his behalf. Altogether inadequate is, however, this fact to reconcile us to the painful and inartistic details which are exhibited. The whole belongs to the style of work brought into favour by M. Zola. To attack it is accordingly to open out the wide question of realism. This there is little temptation to do. To us, however, this art of M. Zola is indescribably pitiable and offensive. No charge of plagiarism from Zola is to be brought against Mr. Buchanan. ‘A Sailor and his Lass’ is a mere carrying out of views already put forward in ‘Nell,’ a poem which is earlier than any of M. Zola’s best known work..” And a couple of photos to finish off - from Dramatic Notes: An Illustrated Year-Book of The Stage by Austin Brereton, here’s Ada Cavendish as Lady Clare and Eweretta Lawrence as Priscilla Sefton in Storm-Beaten. |

||||||||

|

||||||||

|

||||||||

|

Two poems I’ve also found a couple of ‘new’ poems, ‘Trial’ and ‘Yearning’. These were published in Lays of the Sanctuary, and Other Poems, compiled and edited by G. Stevenson de M. Rutherford (London: Hamilton, Adams, and Co., 1859) and since they are credited to ‘ROBERT W. BUCHANAN, ESQ. I suspect their source was Buchanan’s second book of poetry (which is the only one I’ve never seen). So I’ve given them their own page on the site, until matters are clarified. ___ ? I was going to head this last bit ‘How Old Harriett Jay?’ in a nod to the Cary Grant telegram (‘Old Cary Grant Fine, How You?’) but checking it on google, it turns out it was apocryphal (odd the stuff you can find on the internet) so I’ll just have to plunge right in. I found a piece about Harriett Jay in The Oban Times (reprinted from the Daily Mail) which I’ve put on The Nine Days’ Queen page, since it related to the production of that play in Glasgow. There are a couple of reasons for reprinting it here: The Oban Times (26 March, 1881 - p.6) THE COMING ACTRESS. In view of the appearance in Glasgow to-night at the Gaiety Theatre of the gifted young lady who is best known to the world as the authoress of that famous novel, “The Queen of Connaught,” a few further particulars that are not yet generally known may interest our readers. Miss Harriet Jay was born in the neighbourhood of London in 1857. When a child of nine or ten she became an inmate of the house of her brother-in-law—Mr Robert Buchanan, the poet—and from that day forward has been the companion of the erratic poet’s wanderings. Her surroundings throughout have been romantic as well as literary. It is no mere conjecture which assures us that, apart from her own fine gifts, she is the centre of much that is best in Mr Buchanan’s poetry. She is the “Clari” of many well-known lyrics—“Clari in the Well,” for example, and “Will-o’-the-Wisp, a Ballad written for Clari in a Stormy Night,” which first appeared in Good Words— And now you’ve the reason that Clari is gay, Elsewhere, in the “Asrai,” she appears again:— When Clari, from her chamber overhead, She commenced to write when very young, and her first effusions were in verse. It was not, however, until Mr Buchanan went to reside in Ireland, occupying a lonely lodge in one of the wildest parts of Connaught, that the young authoress began to discover her true bent. For years she studied Irish character. The result was at last seen in her first story, “The Queen of Connaught”—a book which took the world by surprise, and ran through many editions. Of the thousands who read it, not one guessed it to be the work of a young girl. It was attributed, at various times, to Mr Charles Reade, to a popular landed proprietor, and to a renegade Catholic priest. The very language was startling and fearless in its naturalism. “It has about it a strange fascination,” said the critic of the Morning Post; “quite unlike any other tale that has ever appeared.” The first success was followed rapidly by “The Dark Colleen,” a tale of deeper pathos and more perfect finish, containing descriptions that could scarcely be surpassed. From that time Miss Jay’s position as a novelist was assured. Little more than a year ago she resolved to gratify another ambition and go upon the stage, chiefly to realise her own heroines, and also those of Mr Buchanan’s play’s. For many months she acted in the country under another name; and then, when her novitiate was over, she appeared in London. Her success soon came, when, after a preliminary trial under disheartening conditions, “The Nine Days’ Queen” was produced, with Miss Jay in the title role. The chief metropolitan critics declared that it was many a day since such a face and form had appeared on the stage; and by more than one she was compared to the late Mrs Rousby. She appears to be fortunate in her choice of a first part. By birth, personal beauty, and education, she is an ideal Lady Jane Grey. The London press are unanimous in pronouncing Mr Buchanan’s play one of the most stirring dramas of recent years. One scene, that where Lady Jane refuses the crown in presence of the dead body of Edward VI., is said to have perfectly electrified the London audiences. It is to be hoped that before Miss Jay leaves Glasgow she may appear in the title role of the celebrated Olympic drama founded by Mr Buchanan on her own “Queen of Connaught”—a drama that ran for many months in London, but which has not yet been seen in Glasgow.—Daily Mail. First, the confusion over her date of birth. Harriett Jay was born on September 2nd, 1853 (here’s a copy of her birth certificate), not 1857 (which I’ve also seen elsewhere). However this report does confirm my belief that she wasn’t ‘adopted’ by the Buchanans when she was ‘at a very tender age’ (as she writes in her biography of Robert Buchanan) but I reckon around 11 years old (which is when the Buchanans would be living in Bexhill). The other point about this item which is worth noting, is the revelation that Harriett is Clari. I always wondered whether Clari referred to Clara Leigh Hunt, whom Buchanan met when staying with Thomas Love Peacock, then decided it was more of a poetic convention - like all the ‘Mary’ poems of his early Scottish books. I never considered it might have been his ‘adopted’ daughter, Harriett, but it does make more sense. He could hardly have called her ‘Hari’. _____

22 March 2023 Still tinkering with stuff, nothing important. I came across a poster for another film version of When Knights Were Bold, which was never made, which sent me down a rabbit hole, checking for any more versions of the film which I may have missed. Details of what I found are here and this is the poster; |

||||||||

|

|

Then I was contacted by Rudolf Blind’s great, great, great grandson, suggesting a grand quest, which I decided against, but led me to find a few more Blind works, which are available here. And here’s a new (well, 2020) German translation by Peter M. Richter of Buchanan’s second novel, A Child of Nature - Ein Kind der Natur. |

|

|

Let’s end with a performance by The Two Leslies of a song from Tulip Time, the musical adaptation of The Strange Adventures of Miss Brown, ‘Noah Had Two Of Everything’.

|

|

5 January 2023 Thought I’d better clock in for the New Year. Just a couple of things. I found some more meditations on ‘The Ballad of Judas Iscariot’. There’s one from April, 2020 on the Center for the Restoration of Christian Culture site, and Joanna Seibert’s site has a page relating to Morton T. Kelsey’s book, The Other Side of Silence: A Guide to Christian Meditation (published in 1976) which included an extract from the poem. I also came across an annoying reference to a version of Buchanan’s poem read by Ken Nordine on American TV in his series, Faces In The Window on 4th April, 1953, which seems to have been lost. Bugger. And I also added a few more book reviews to the site. The City of Dream from The Spectator and several from the New York magazine, The Nation. These begin with the American edition of Poems which included Undertones and Idyls and Legends of Inverburn and concluded with a couple of selections from London Poems. The Nation reviewer was not impressed by Undertones, but did quite like Inverburn and ended the review with the following: “That we think highly of Mr. Buchanan the reader may, perhaps, infer from what we have written, despite the fault which we found with him at the beginning. He seems to us one of the few young singers of the day who is really a poet, and who has a future before him.” I could find no review of London Poems, but with North Coast, either there was a different reviewer or his admiration for Buchanan had begun to cool. This one ends with: “Mr. Buchanan is, so far as he is at all valuable, a poetical preacher of love and charity, enforcing his text by moving examples. Thus he does a noble work; and he does it more than tolerably well, but is hardly a poet, or he would not have chosen themes that might better have been treated in prose; at the utmost, would have treated them less prosily.” And then there’s a coruscating demolition job done on The Book of Orm, which concludes: “There is more in the volume, but none is better than these poems we have mentioned, and the whole work is as weak and pretentious, and every way unprofitable, as any book of poems that has come within the last ten years from the hand of a person of any repute. It is irredeemably feeble and secondary.” The rest appears to be silence, apart from a brief review of Saint Abe and His Seven Wives. One wonder what they would have made of that if they knew the author was Buchanan. _____

Diary Archives:

|

|

|

|

|

|

|