ROBERT WILLIAMS BUCHANAN (1841 - 1901)

|

ROBERT WILLIAMS BUCHANAN (1841 - 1901) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

THE LITERARY LADIES’ DINNER

Harriett Jay attended the first ‘Literary Ladies’ Dinner’ at the Criterion Restaurant, London on May 31st 1889. The Daily Telegraph (24 May, 1889 - pp.4-5) WHAT is called without much felicity of phrase a “literary lady dinner” is announced to take place at the Criterion on the last day of this month. We wish it every success, although we hardly see the necessity of this separatist system in public festivity. No doubt the idea may have been started by way of revenge. Men at their public dinners exclude women, as a rule, although there are a few happy exceptions. Many reasons, no doubt, exist for this ungallant custom. In the first place, few ladies are so fond of a very good dinner and first-class wines as to pay a guinea or a guinea and a half for the elaborate feast set before the guests on the occasion of charity or commemoration banquets. Then they hardly have the patience to sit through the long meal, tasting dish after dish. A third reason for their absence is the extension of smoking. There was a time when, after men had dined, as many as liked adjourned to another and smaller room to smoke; now the smoking often commences immediately after the cloth is removed, and it is not every lady who can stand the ordeal of two or three hundred gentlemen smoking at once. These are put forward not as reasons why ladies are not usually invited to public dinners, but as excuses more or less legitimate for the fashion of the day. We fail to perceive, however, why the authoresses should dine by themselves. Were they all young mothers, anxious to compare notes as to baby’s first tooth or the comparative merits of rival infant foods, we could understand why the presence of men might prove a hindrance to the ample discussion of these really great questions. A féte of fashionable women might also find gentlemen in the way, for the details of dress can never be comprehended by men; they simply, as husbands, know the cost, or as admirers note the general effect. The authoresses, however, who are to assemble at the Criterion on the 31st are not all young mothers. Some of them are unmarried ladies, and “the children born of them” are essays, pamphlets, articles, and books. Then, as persons of high intellect, they are above the frivolities of the costumier or the milliner, preferring severe simplicity to the newest gown or hat from Paris. Why, then, are men to be excluded from this feast of reason and this flow of soul? One exception is made: there are to be male attendants, not waitresses. Is not this a slur upon the softer sex? Besides, who is to guarantee the conclave from the intrusion of all the authors of Great Britain, disguised as waiters, and anxious to gaze upon their fair rivals assembled around the board? ___

Pall Mall Gazette (29 May, 1889 - p.7) THE LITERARY LADIES’ DINNER. Much interest is being manifested in the literary ladies dinner which is to be held at the Criterion Restaurant on Friday. The number of guests is to be thirty, and the affair is to be strictly feminine, although on this point there has been some protest. One lady, indeed, who declined the committee’s invitation because she was going into the country, added that she would come to town for the dinner if the brethren of the craft were invited to share the feast with their sisters. But the committee stood firm, and even resisted the plea of seven gentlemen novelists who offered to come as waiters since they were not to be admitted as guests. When these were rejected, Mr. Robert Buchanan and Mr. Roden Noel asked if they might not come, being “only poets.” But even this plea failed. Miss Olive Schreiner will occupy the chair, and among the guests expected are Mrs. Humphry Ward, Mrs. Lynn Linton, and Mrs. Mona Caird. The idea of the dinner, which it is hoped will draw literary women into closer union, originated with Miss Honor Morten, a niece of William Black, and the beautiful wretch who is the heroine of one of his stories.—Manchester Examiner. ___

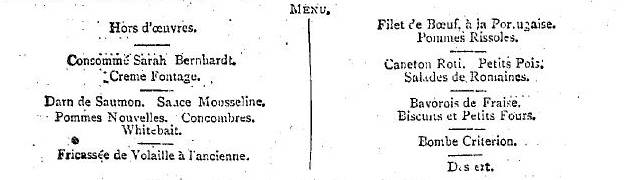

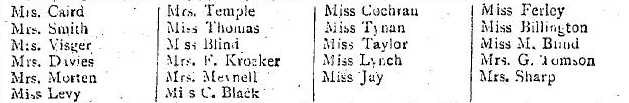

The Daily Telegraph (1 June, 1889 - p.5) Last night in the Prince’s Room of the Criterion Restaurant twenty-two of the fair sex sat down in solemn state to consume what was described on the menu (may we say ungrammatically?) as a “Ladies’ Literary Dinner.” The bill of fare in question may in itself be termed a quaint work of art, for it had on the one side a portrait of the King of Hades, with motto “Copy please,” and on the other, two cats, presumably females, disputing the possession of a small mouse of the masculine gender. The appropriate quotations were: “They could not sit at meals but feel how well it sooth’d each to be the other by,” and “Her ’prentice han’ she tried on man, and then she made the lassies, oh!” It must be admitted that the dainties consumed were not extravagant. “Consommé Sarah Bernhardt,” salmon, whitebait, filets of beef, roast duckling, and ices are not expensive articles of food. Nor can the literary lady be blamed for qualifying the solids with dry champagne, claret, and sherry, or finishing up with black coffee and liqueurs. The table was arranged in horseshoe shape, Mrs. Mona Caird taking the chair. Special instructions were issued to prevent the intrusion of man, except in his capacity of waiter. Indeed, the banquet, from the jealous way in which it was watched, might have been a feast of the favourites of the Seraglio. In default of a real guard of the Harem, the defence of the repast was left in the hands of M. Négro, who performed his duties most efficiently. It cannot be said that there were any beautiful dresses; rather be it recorded that the costumes were æsthetically comfortable, the silken blouse being especially conspicuous. After dinner there was speechmaking, less in denunciation of the old Adam and his descendants than in praise of the new Eve and her ways. There was a piano in the room; there were players and singers present. There was scope for recitation; Miss Harriett Jay is a dramatist and actress. The dinner at the Criterion was clearly a step further towards the goal of Woman Franchise. And like a votive offering, the fumes of cigarettes ascended to the shrine of Pallas Athene, as the literary ladies crowned one another with flowers of speech. ___

Pall Mall Gazette (1 June, 1889) WOMEN WHO WRITE. THE LITERARY LADIES’ DINNER. [BY OUR LADY REPRESENTATIVE.] They say—— What do they say? Well, broadly, this—that there never was and never is, and never will be, a more insipid and uninteresting assembly than that at which “women only” gather together for social purposes. And yet, with the dread possibility of a failure before our eyes, a failure which would be reported the next morning as surely as we saw the gentleman of the Daily News (I abstain in mercy from mentioning his name, though I could if I would) lounging round the doors of our antechamber when the clock was pointing towards 11 P.M., we entered the portals of the Criterion last night with the consciousness that we would be a party of women only. Eight o’clock was the dinner hour, and at eight we filed into our temporary drawing-room, most of us strangers to each other, but all of us eager to be strangers no more, but to do our “level best” for the establishment of a sisterhood of letters. Who knows not the subdued agony of the mauvais quart d’heure before a dinner party? But so resolved were we all to smooth matters over that in less than five minutes after entering the room, each guest was engaged in conversation with another guest, an entire stranger hitherto. A group of lively, laughing girls sat in a corner; a stately brunette leaned against the mantel-piece, intently studying a mysterious plan, together with a cheery, bright-eyed matron; a young Greek goddess in draperies of rosy pink stooped gracefully down to a bevy of ladies discussing some interesting topic, and ever and again a dark-haired girl in a gown of soft grey and vieux rose darted from group to group. Then dinner was announced, and presently we were (openly) studying the Mephistophelean menu. The menu was as follows:— |

|

|||||||||||||

|

They could not sit at meals but feel how well Her ’prentice han’ she tried on man TABLE TALK. The result of our study of the menu having proved satisfactory, we commenced our “consommé Sarah Bernhardt,” but ere yet the whitebait made its appearance we were “chez nous,” each and all. Mrs. Mona Caird, in a gown of white and gold brocade, with rosebuds on her dress and in her hair, and a fan framed with velvety pansies, sat at the head of the table. On her right Mrs. Meynell, whose exquisite sonnets are known to all lovers of true poetry, and on her left Mrs. W. Sharp, whose artistic robes of terra cotta formed a beautiful contrast to the rich gold of Mrs. Graham Tomson’s lovely gown. Before long the hum of many voices filled the room; subdued peals of laughter came from various groups; and in aggressive wickedness we did what the mysterious voice of one of our brethren of the press had gloomily foreboded (together with a prophecy that “proceedings would be extremely slow”)—namely, we discussed each other’s books and writings with all the gusto and the delight which only things novel and unknown are able to call forth. One moment I was roaming over the wide, wide world with “J. A. Owen” (Mrs. Visger), and listening with intense delight to that bright-eyed lady’s account of the wonderful naturalist down in the green Surrey country nooks; the next I discussed “the pictures of the year” with another, or took mentally a note of the merits and demerits of several of our great publishers; and ever and anon I exchanged a glance charged with deep meaning with a fair-haired sister-journalist whose laughing eyes met mine from the dim distance. COFFEE AND CIGARETTES. Long before our coffee was brought in at ten we had conquered what little shyness and constraint there was, and presently I heard a soft rustle behind my chair, and a little silver cigarette-box was coyly held out to me, while the voice of a girl in pink and grey, who was the heart and the soul as well as the head of the party, whispered cajolingly into my ear, “Look here, take a cigarette, but don’t say anything about them in your paper!” “What, bribing the British press? Your name, together with your cigarettes, shall stand as a cross heading in the P.M.G. ere yet the week is out!” “No, no, keep my name down, and, above all, don’t say that I am my literary uncle’s niece; he does not approve of the lustre which I reflect upon his name.” She pleaded so eloquently, and, with her cigarette held daintily between her white fingers, looked at me so bewitchingly, that I could not but promise. And as I looked up again the whole scene was changed. My journalistic friend’s girlish face was surrounded by an aureole of light blue cigarette smoke; Miss Harriet Jay leaned back on her chair and looked thoughtfully at the gleaming point of her cigarette; Miss G. Tomson’s delicate dark beauty was dimmed by the clouds of incense from her “weed;” Miss Levy toyed with the ashes on her plate; and the “beautiful wretch” in pink and grey called vainly upon her miniature match-box to return to her. OUR ABSENT FRIENDS. This was the beginning of the best part of the evening, which began after the toast to her Majesty, by Miss Honor Morten reading out the letters of those who could not or who would not come. The first among them was a letter from Miss Olive Schreiner, whose absence everybody much regretted. She had promised to take the chair before the day of the dinner was settled, but had since vanished from everybody’s eyes, and was only discovered yesterday after the telegraph wires had been wildly busy about her. Miss Schreiner’s letter was full of regret at her absence and also full of sympathy with the gathering, and she expressed the hope, which was fervently echoed by all, that this would not be the last opportunity for literary women to meet together on similar occasions. Miss Mabel Robinson, Mrs. Macquoid, Mrs. Humphry Ward, Lady Wilde, Edna Lyall, Mrs. Lynn Linton, and many others “regretted” their enforced absence; Mrs. Louisa Parr did not come because she was in favour of “mixed affairs;” and “John Strange Winter” remained at home because, having been twice at dinners of the same kind, which were “ghastly,” she, like a wise woman, remained at a safe distance from the “dangerous experiment.” THE SPEECHES. Mrs. Michael Smith—what lady journalist knows not her tall figure and her intelligent face, surrounded by an aureole of grey hair?—then cheerfully gave “The martyrs of life, the married ladies,” for whom Mrs. Mona Caird responded in a short, thoughtful speech, expressed now with mirth and humour as she pointed out that our present marriage system was “perfectly straight—except in some cases,” and again with an earnestness bordering on pathos as she talked of all the new ideas floating about like souls looking for bodies. I have no space to repeat all the good things that were said in the subsequent speeches, but I would not be a woman could I forbear to say what Mrs. Meynell told us, as, with dreamy eyes, she responded for “Poetry.” She talked of the discord which the hum of mixed voices generally produced, but at to-night’s gathering, she said, “even the Superior Being looking down would be almost pleased in hearing the blending of the soft women voices.” Miss Mathilde Blind raised a different note by a noble and eloquent speech on the dreams, needs, hopes, and aspirations of woman now that there is a general up-lifting of her nature to new aims and ideals. Miss Levy, the fair young authoress of “Reuben Sachs,” spoke for fiction; Mrs. Smith gave “The Press,” “the growing power in literature”; Miss Harriet Jay, who looked like a Greek goddess, gave, in a low, sympathetic, voice, “The ladies of the drama,” concluding, with excellent effect, “and I am to-night as proud of being an actress as I am of being an authoress.” Then, amidst much laughter, Miss Ferley, with a roguish look, proposed “The spinsters.” Curiously enough, the spinsters were all young women brimming over with high spirits, and with just the slightest soupcon of Bohemianism about them. “BURYING THE HATCHET.” And then, for just another short half hour, we “grouped” once again about the room; fiction and the drama played with their fans and flowers; poetry swept with graceful robes through the wide room, and under one of the electric lamps stood and knelt the press, of all shades of opinion, the hatchet being buried for the nonce in the endeavour to obtain the vanished triolet, a copy of which comes to me this morning by post out of the camp of the arch-enemy, who claims “sweetness and honesty” for sending to me what was originally mine! Here it is; it is worthy of Freiligrath’s bright daughter:— “I found this little triolet There was a piano in the room; there were musicians, singers, and reciters, but we were so pleased with our own society that it never entered any one’s head even to allude to those straws at which those faintly catch who are being swept away by the seas of drawing-room dulness. |

|||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||

|

and your—humble? no, not at all humble, after the “parliament of women”—and your servant. ___

The Daily News (1 June, 1889) LADIES’ LITERARY DINNER. This interesting event took place last night at the Criterion, and there were present some twenty ladies, all more or less known to fame—but chiefly less! Still with Mrs. Mona Caird in the chair, supported by Mrs. Meynell and Miss Mathilde Blind, known names were not wanting. The flow of talk was unceasing during dinner, and the presence of the waiters—though they were men—seemed to exercise no restraint on the “feast of reason.” The menus were aptly decorated to anticipate all ridicule, and represented cats in various contortions fighting over a saucer of milk, and below the quotation from Keats— They could not sit at meals but feel how well The health of the Queen was drunk in coffee with great heartiness, and then Mrs. Mona Caird responded to the toast of the Married Ladies. This gave her an opportunity of dilating on her special subject, and indignantly denying that marriage was a “contract” in any judicial sense of the word. Mrs. Meynell, well known for the exquisite sonnets written as Alice Thomson, spoke well in praise of women’s voices in poetry, remarking on the musical tones which had predominated in the evening chatter. Mrs. Freiligrath Kroeker illustrated this speech by an exquisite little triolet, which she maintained had been given her by a pink domino as she came up in the lift. Miss Blind spoke on literature generally, with all the weight her name could give, and Miss Harriett Jay, speaking on the drama, gave that skilful intonation which showed training. The evening was certainly bright and amusing, and it is hoped the dinner will be repeated in the future with even greater success. ___

The Shields Daily Gazette (4 June, 1889 - p.3) It was not for nothing that the literary ladies who dined together in London the other night had their menu card decorated with a representation of cats fighting over a bowl of cream. Listen to what is said by one literary lady who was present on the occasion. “I went,” she says, “to oblige a great friend, and am horribly disgusted. . . It was in no sense a literary ladies’ dinner, as literature was conspicuous by its absence. Miss —— was the only woman of any note present, and she went to oblige another lady who did not turn up.” Commenting on the fact that no lady was found to respond to the toast of “Absent Sweethearts,” this critic of feminine festivity remarks grimly, “I did not wonder.” The menu, she admits, was good; but, “I counted only six empty champagne bottles, so the dinner was not convivial, if harmonious.” But what do literary ladies want with more than six bottles of champagne? ___

The Southern Reporter (6 June, 1889 - p.2) A LADIES’ DINNER. The Daily Telegraph has made some amusing “copy” out of Mrs Mona Caird’s little dinner, given to twenty ladies of the pen, at the Criterion Restaurant, of which gentlemen were not invited to partake. We are given the menu, and told of the champagne, cigarettes, and coffee which finished the repast, whilst the enthusiastic reporter tells us further that at this dinner “the literary ladies crowned one another with flowers of speech,” and that it was obviously “a step towards the goal of woman’s franchise.” To Mrs Mona Caird, who is best known by her famous question, “Is marriage a failure?” the last statement may be apparent; but there is a distinguished board of modest literary women amongst us who can also make their voices heard above the fumes of cigarettes at a Criterion Restaurant dinner, to whom woman’s franchise does not offer the same attractions; and we shall no doubt hear from them before the question gains much Parliamentary importance. ___

The Saturday Review (8 June, 1889 - Vol. 67, p. 696) L. L. THE Literary Ladies of the Age have met at the Criterion and dined. The reporters, or one reporter, unkindly and unnecessarily remarks that the guests were “of more or less celebrity, chiefly less.” But may people not dine together unless they are celebrated, and is it necessary that all women of letters should be famous? Many of them, no doubt, prefer to be like violets by a mossy stone half hidden, and to sweeten the prose of the magazines with the fragrance of their unassuming poetry. The Literary Ladies were not graced by the presence of some of their most learned sisters, but the learned author always rather prefers to keep out of the way of the herd; a fair herd in this case, no doubt, but a herd for all that. The lady poets and novelists are declared to have enjoyed themselves, to have defended the character (not the moral character) of Mr. ROCHESTER, in Jane Eyre, and to have said very little about SAPPHO. ___

The Scots Observer (8 June, 1889 - pp.67-68) THE L L.’S DINNER. ‘On Friday, May 31st, at the Criterion, the Literary THIS bald announcement does scant justice to the event of the season. Women burning with a sense of wrong have played cricket-ball matches, how’s-that-umpire, ere now; but it was felt that they would never show themselves the equals of men until they dined together at a restaurant and left vesuvians about. So a Literary Ladies’ dinner was arranged by a committee, some of whom thought a few men should be scattered through the room, though the majority said that the male sex were a bore. As a compromise it was suggested that the editor of The Woman’s World be admitted. Finally it was decided firmly to dine absolutely alone; and, as it turned out, the hosts were ladies who would be literary if it was not so expensive while the guests were literary ladies who did not attend. The chair was taken by the famous Mrs. Mona Caird, and among other celebrities present were several who have contributed to the leading waste-paper baskets of the day. [Written by J. M. Barrie.] ___

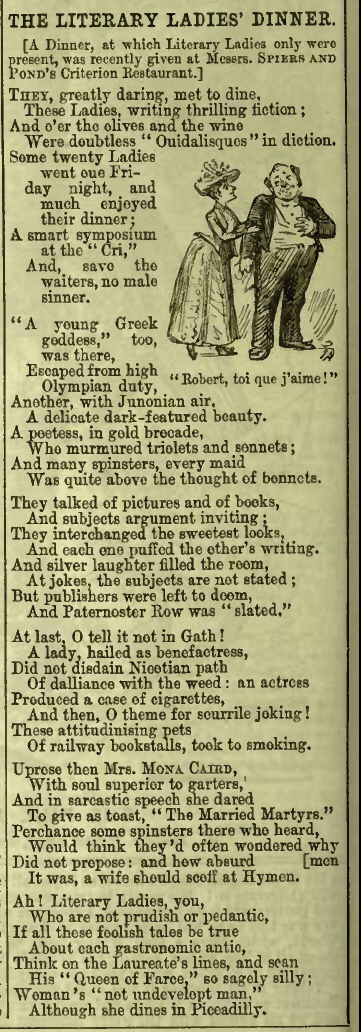

Punch (15 June, 1889 - Vol. 96, p.296)] |

|||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||

|

The Brisbane Courier (Australia) (16 July, 1889 - p.6) LITERARY LADIES AT DINNER. At the Criterion—gracefully alluded to by more than one of the fair diners as the “Cri.”—no fewer than Two-and- Twenty Ladies who Write (and sometimes print) sat down to a sufficient, but not extravagant, repast, on the 31st May. We are able (says the St. James's Gazette) to contradict on the best authority the false rumour that there was a course of Bath Buns on the menu, and that among the vins was Tea. On the contrary, the literary ladies consumed whitebait, and salmon, and filets of beef, and other wholesome and sufficient articles of food. The Amphitryon who gave this lavish entertainment is understood to be a lady who has written (and occasionally published) something herself; but literary ladies are so modest that we shrink from giving her name. Mrs. Humphry Ward did not come, nor did Mrs. Lynn Linton, nor the author of “An African Farm,” nor Miss Rhoda Broughton; but Mrs. Mona Caird was present (in the chair), and Mrs. Meynell, and Miss Harriet Jay, and Miss Mathilde Blind, and eighteen other almost equally famous authoresses. The menu-cards were gracefully and appropriately adorned with a picture in black and white, representing two cats (presumably cats of the more literary ses) disputing over a bowl of cream. Proud man was not admitted to the feast, except in the fitting capacity of waiter. After dinner he retired, and the ladies drank the health of the Queen, chiefly in black coffee, and made speeches to one another, and those more truly conscious of their mission lighted their cigarettes. Mrs. Mona Caird worked round to the great subject with which she has linked her name to all time, and favoured the company with her views on the marriage contract. Mrs. Kroeker recited a triolet, a little thing of her own which she had composed in the lift on her way up to the gilded halls in which the banquet was held. Mrs. Meynell, who has composed sonnets, spoke of poetry; Miss Harriet Jay had every right to speak on the drama, and Miss Mathilde Blind responded to the toast of “Literature.” The dresses, it is recorded, were more remarkable for comfort than for vain and empty show, and that species of garment known as the “silken blouse” was especially conspicuous. The proceedings were kept up with unabated spirit till a late hour; the bell was several times rung for more coffee; and it was not till past 11 that the company adjourned to catch their omnibuses. ___

Te Aroha News (New Zealand, 10 August, 1889 - p.3): Included in ‘A Lady’s Letter From London’ (dated June 14th): “Mrs Mona Caird (who has been much run after by lion-hunters since “The Wing of Azrael” raised a storm of discussion) presided at a new departure called the “Literary Ladies’ Dinner” last Tuesday. None of the male sex were admitted, even the attendants being waitresses. The conversation is understood to have been of the most sparkling and brilliant description, and the speeches far above the level of masculine post-prandial eloquence. Mrs Lynn Linton excused herself from attending in a characteristically caustic effusion, which was read amidst much laughter and not a few blushes; and Mrs Oliphant, Mrs Humphrey Ward and Miss Olive Schreiner also found themselves somehow unfortunately unable to be present. The dinner was, however, graced by Miss Alice Cockran (of “The Queen”), Mrs T. P. O’Connor (a practised platform orator), Miss Friedrichs (“Miss Mantalini” of the “Pall Mall Gazette”) and Mrs Humphreys (of the “Daily News” and “Truth”). _____

The annual Literary Ladies’ Dinner (in 1893 the name was changed to the Women Writers’ Dinner) continued until the outbreak of the First World War. Harriett Jay did not attend the event in 1890, an account of which is available below. |

|||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||

|

[From The Daily News (31 May, 1890 - p.6).] Harriett Jay’s absence the following year could be explained by this passage from ‘A Club of Their Own: The “Literary Ladies,” New Women Writers, and Fin-de-Siècle Authorship’ by Linda Hughes (Victorian Literature and Culture Vol. 35, Issue 1, March 2007, pp. 233-260 - available from JSTOR) which provides a history of the ‘Literary Ladies’ Dinner’. It includes an extract of a letter from Honnor Morten to Elizabeth Robins Pennell regarding the new method of inviting women writers to attend the 1891 event (”Five invitations will be sent to each member of the committee to send to the five literary ladies she would prefer present.”): ‘The method was not failsafe. As Morten’s 19 June letter to Pennell commented, “You are splendid! All your people reply most promptly whereas I have not heard a word of any of those Mrs Meade undertook. ... I suppose Miss Blind is ill; I can get no letters from her and Miss Jay has flown at me—wants to know why she - and she only of the old guests —has not been invited to this year’s dinner. It is awfully unpleasant for me, but I have followed Matilda’s example and taken refuge in silence.” ’ An account of the third event is available below: |

|||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||

|

[From The Daily News (26 June, 1891 - p.6).] Harriett Jay is mentioned as attending the fourth Dinner in the following report from The Edinburgh Evening News (3 June 1892 - p.2): |

|||||||||||||

|

|

But she is not mentioned in the report below: |

|

|

[From The Daily News (3 June 1892 - p.3).] The York Herald (4 June, 1892 - p.5) Some amusement was caused at the literary ladies’ dinner last night by the steady refusal of one of the company to give her name. The authoress of “Dr. Edith Romney,” was there, and received congratulations on the success of her new novel, but all efforts to ascertain her identity were futile. Under the circumstances, it is a matter of surprise that she attended the banquet, which appears to have been highly successful, though it was not graced by the presence of most of the best known literary ladies. ___

Harriett Jay’s attendance at the renamed Women Writers’ Dinners seems to have ended with the 1893 event, at least I have not found any further mentions of her name. A possible reason for this is the financial problems of the Buchanan household in 1894, which resulted in an appearance in the Bankruptcy Court for both Robert Buchanan and Miss Harriett Jay.

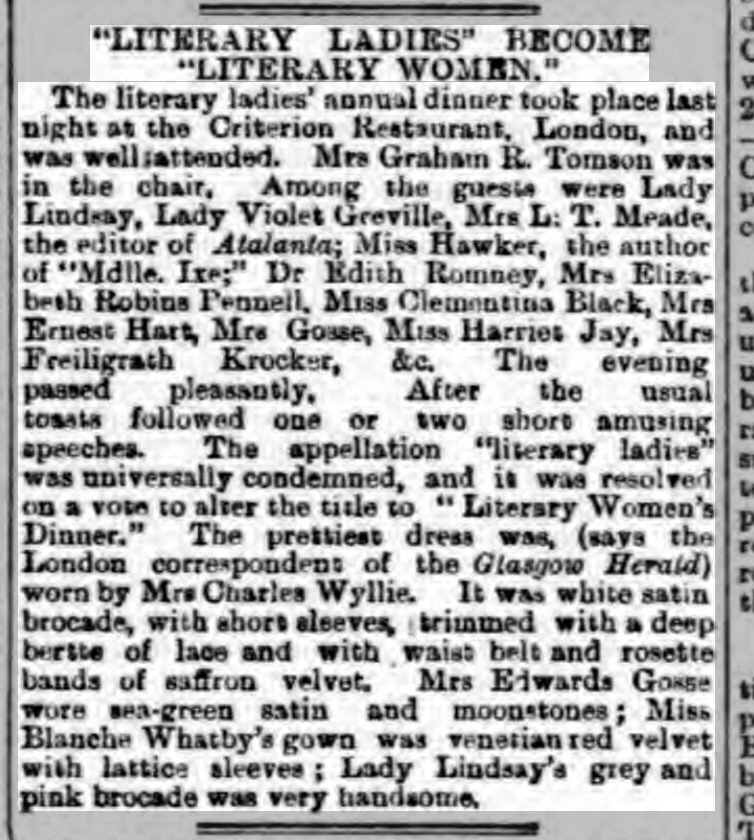

Lloyd’s Weekly Newspaper (4 June, 1893) WOMEN WRITERS’ DINNER. Under a slightly different title the “Literary Ladies” of former years met on Wednesday at the Criterion to hold their fifth annual dinner. The attendance was larger than usual, there being more than 50 guests present. Miss Mathilde Blind took the chair. The table was arranged in horse-shoe shape, and presented a very pretty sight, the bright dresses not being intermingled with black coats, as is usual at large gatherings. After dinner Miss Blind rose to propose the toast of “The Queen,” and stated that the Victorian age could boast a more celebrated roll of authoresses than all other ages put together, and this development was particularly gratifying as taking place under a woman Sovereign. In conclusion, Miss Blind suggested it would be well if Miss Christina Rossetti could be appointed Poet Laureate. The next speaker was Miss Christabel R. Coleridge, granddaughter of the poet, who took fiction for her theme. Miss Harriett Jay then gave a brief recitation, which was followed by a speech on poetry by Mrs. Hinkson, better known under her maiden name of Katherine Tynan. Mrs. Hinkson spoke with a delightful brogue. Miss Lowe, editor of the Queen, then spoke with authority on journalism, and gave an amusing account of the difficulties between lady reporters and printers. She said the only fault of the lady reporter was that she could not condense. When asked for an inch, she invariably gave an ell. Mme. Chevreur, who under the nom-de-plume of “Tasma,” has written some charming Australian novels, and who had come over from Brussels on purpose to be present, made a brief but bright speech, pleading that an International congress of women-writers ought to be held next year in Brussels. These speeches being over, it was proposed that the dinner should next year be replaced by a tea, but this feminine notion was scouted with laughter and cheers, and there seems no reason to believe that this annual feast will be abandoned. Amongst those present were Lady Lindsay, Lady Margaret Hamilton, Mrs. Molesworth, Mrs. L. T. Meade, Miss Alice Corkran, Mrs. William Sharp, Mrs. Meynell, Miss Emily Hickey, Mrs. Alfred Marks, Miss Beatrice Whitby, Mrs. Kent Spender, Miss Heather-Biggs, Miss Adeline Sergeant, Miss Mabel Collins, Miss Florence Balgarnie, and Miss Helen Shipton. _____

|

|

|

|

|

|

|