|

of the blest bread covered with flowers; of the Christmas night, when fantastic carol-singers mingle their music with the roaring of the sea. All that is to come; and in the meantime I am off with my landlord, the captain, for a shooting excursion on the water.

JOHN BANKS.

_____

From The Argosy - March 1866 - Vol. I, pp. 315-324.

WINTERING AT ÉTRETAT.

SECOND PAPER.

MARIE-CELESTE, Alexandrine-Clarisse, and Pauline-Adèle (for so men name the great, yet silver-voiced bells of Our Lady’s Kirk) have plenty of singing to do all the year round,—chanting for prayers, tolling for funerals, shrieking aloud in times of peril; but they are busiest of all during the last days of the old year and the first days of the new. Far inland along the Petit Val, and out seaward between the tall cliffs, awakening echoes in the weirdly garlanded caverns under the heights, and dying along the crumbled streets of that subterranean city on which I have pinned my faith, the voices of the sisters ring joyfully on this Sunday before Christmas; and very sweet it is to sit on the cliffs and listen, with the pious folk thronging down below in the narrow streets, and the sunlight shining down through a rent in the clouds drifting northward.

There are white waves on the sea; but on board a little brig, that passes along at a short distance from land, I can see the sailors standing bareheaded, hearkening and praying. If there were snow, the luxury, the melancholy sweetness, of the holy season would be complete; but snow there is none, and there is no sign of frost, and one dare dip in the sea. Nay, to render matters worse, there has been rain, and more is coming. Weariest, dreariest, unfittest of all things, is rain in the holy season; when all should be still, silent, solemn,—white as the purity by which we stand appalled, pale as the Soul dreaming on Christ’s Day in the chancel of His universal church. Yet the thundering of the sea, and the chiming of the three dark ladies in the steeple, make some amends for the vigour of the sun, who, as Goethe finely says, endures no white, and who, by the way, was consequently very fond of shining upon Goethe.

By the time that I have ceased musing on the heights above the Porte d’Aval, and am descending the precipitous path that leads down to the village, the people have done praying, and are returning home to dinner. So I wend my way through the main street of the village, inland to the Petit Val, recently a dark and narrow glen, where the church stood solitary, but now dotted here and there by the chalets of summer residents. There stands the old church still, with its sombre masonry, its grim square tower, its quaint burial-place: a strange contrast to the pretentious little masonic impertinences that are beginning to cluster around it. Bleak and barren, covered with dark herbage, but without a tree, was the valley, when the village consisted only of a few fishermen’s cottages, clustering close upon the strand, just above high-water mark. Years and years ago, when papal bulls were common, and church decorations in good taste (for Europe, as yet, lacked her Rabelais and her Calvins), there dwelt in Étretat a fair lady named Olive, who, though very rich, was not above washing her own linen down yonder at the fountain, and who, while so engaged one day, at low tide, was set upon by a band of Norman freebooters, heathens. Landing from their bark in search of plunder, and arrested 316 by the vision of a lady so fair, the villains wanted to be rude. But Olive fled, calling on the Virgin. “Save me in this peril, O Blessed Lady!” she cried; “and I vow to build thee a church upon my land.” Saved by a miracle, she kept her word, and erected L’Eglise de Notre Dame;—not here, in the Petit Val, but somewhere within easier reach of the sailors and fishermen. For the story goes that the devil, disgusted at the state of affairs, conveyed the church by night to the spot on which it now stands, thereby hoping to cheat the poor folk out of a mass or two, and get a surer chance of their souls.

The grass is deep in the churchyard. The ancient burial stones lie broken, slimy, and streaked with green moss. I cannot stir a foot without stepping on the dust of the dead. Strangely in contrast with the old tombs are the modern graves, with their little railed-in patches of garden-soil, their headstones adorned with wreaths and crosses of beads, little paintings on glass and papier-mâché beneath, and “Priez pour son âme” written under the chronicle of name and age. In one thick headstone is a glass door, through which is seen a memorial in white beads—a round wreath, a cross in the centre, and a bunch of immortelles above. A mother’s hands have fondly woven that simple circlet; and her baby-boy sleeps below, padded round with the dust of one who saw the Field of the Cloth of Gold. Here white and blue beads, and a little bright picture of a doll with wings, mark the resting-place of a maiden. Solemn black beads, and a black wooden crucifix, are placed yonder, above an old man. For some reason or other, the effect is not tawdry—in spite of the sombre background of the Petit Val. Frenchmen invest even death with nameless prettinesses, but they do this as no other nation of men could—sweetly, reverently, though without depth. They cover corruption with flowers and beads, and simple strewings, and write shallow little quatrains about the angels; and they do not pass out of the sunshine, but, shading their faces, look childishly at the threshold of the mystery.

Finding that the service within Our Lady’s Kirk is not fully over, I take a path up the hill-side, and wind my way meditatively until I stand on the north cliffs. Here, on the very pinnacle of the height, exposed to all the winds, open to the view of the whole village, and possessing a long prospect inland and seaward, stands solitary the tiny chapel of Our Lady of Safety—or Notre Dame de la Garde. The simple design of the building was furnished by a clever abbé at Yvetot, and in 1855, stones, bricks, pebbles, and clay, all things necessary for building, were carried up to the site by the sailors themselves. The Empress herself joined in the good work, contributing an altar-piece. No public service takes place here, but now and then the bell tolls, and special masses are said—for the dead, for the sick, or for a friend or sweetheart at sea. The chapel is chiefly used for private prayer, and seldom a day passes without the visit of one or more pious parishioners. Just now, as I enter, a young girl kneels before a chair close to the door, burying her face in her hands, and sobbing silently. Yonder, within the rails, is the altar-piece—a company of haggard, shipwrecked sailors upon a raft, raising eyes of mute appeal to the good Virgin, who appears among the clouds. Here, to the left of the altar, is the statue of Our Lady, crowned and gentle. Strewing the pedestal and hanging round her feet, are the simple childish offerings 317 of the sailors and fishermen, and their wives—with some costlier gifts of people richer in the world’s goods. Wreaths of coloured beads, such as adorn the graves in the churchyard; garlands of flowers deftly cut in white silk and satin; little rude pictures of the Virgin; rosaries, with crosses carved in wood, and one tiny piece of china, representing a little angel standing over a font of holy water. All these are pious gifts—bribes that the sailor at sea may reach home safely, tokens of gratitude for preservation during a long voyage, mementoes of those who sleep fathoms deep under the motion of the great waters. A white cameo, in a black ivory frame, betokens some wealthier donor. It represents a fair young girl, with a sweet, quiet face, and vision-seeing eyes. Is it a portrait? Of the living, or of the dead? Has some weather-beaten mariner placed here the likeness of his true love? or does some father plead by this picture for a daughter who has been wafted to the shores untrod by mortal foot? The little chapel is open night and day, but these gifts are sacred. The most hardened villain from the galleys would scorn to touch them. Jean Valjean would bare his head and glint up at the plaster Virgin, and hobble away hungry and athirst. It would need another revolution to imperil the little chancel and its contents, and even in that event, the sans culotte element would be small in Étretat.

This Sunday before Christmas is destined to be occupied in haunting holy edifices. At eleven o’clock in the evening, Marie-Celeste, Alexandrine-Clarisse, and Pauline-Adèle, summon the inhabitants of Étretat to attend midnight mass in Our Lady’s Kirk; and I am off with the rest. Thanks to my landlord the Captain, I get a seat up in the little gallery where the organ is placed, and. have a fine view of the whole church. The benches below are filling rapidly, and the clatter of wooden sabots, passing up the path in the centre, almost drowns the intoning of the priest’s assistants. Monotonous, dreary, proceeds the chant in dog Latin. The assistants move to and fro at the altar, and one tiny fellow of six solemnly kneels on the footstool. Nothing very solemn is taking place, if I may judge from the merry faces of the younger people. That gaily-dressed fellow with the cocked hat and gold-crowned staff, standing with his face to the altar, just without the rails, is the Bumble of the church, the beadle. He is not afraid to peep knowingly at the pretty girls, and signal with his eyebrows; he is pompous, but neither fat nor proud. The minutes wear on, and the chant continues; the tallow candles by which the church is lit, flicker and look faint. The altar, with the men thereon, looks like the stage of a little theatre. And now begins a sorry business. At the back of the altar a number of wax candles, yet unlit, are formed into the likeness of an immense papal crown; and a man in shirt-sleeves and corduroys steps forward with a ladder and a long pole with a candle at the end. It is a difficult task, this lighting up of the crown. The service goes on, but every one is watching the agonies of the man in shirt-sleeves; for some of the candles refuse to burn, and others go out directly they are lit. By midnight, however, the show is complete. The crown burns brightly at the altar. Then two choristers step forward, and seizing the ropes which depend without the rails, pull at the great bells, which first emit a faint sound, and then grow louder and louder, till the full, deep tone sounds solemnly. 318 All the congregation join in a hymn of the Nativity. But the pomp is not yet over. About half a dozen young lads of the village, clad in plain modern black, their Sunday’s best, appear at the altar. Each seizes a long wax candle, and then all, preceded by Bumble in his cocked hat, march down to the other end of the church. These are supposed to be the shepherds who bore abroad the news of the Nativity; but assuredly no “lumière divine les environa,” as they stand grinning at their friends, poking each other slily in the ribs, and winking at Bumble. “Quem vidistis, pastores? dicite; annunciate nobis in terris quis apparuit;'”—and one of the lads, selected for the task on account of having a severe cold in his throat, chants dismally, in Latin that sounds very like French, “Natum vidimus, et chorus Angelorum collaudantes Dominum!” Then the lads disappear for a moment, but shortly march back to the altar, preceded by Bumble, and carrying on a large salver, covered with a white cloth, a huge piece of sweet bread, shaped like a papal crown, and hung with many-coloured flowers. They pause at the altar, where the priest, waving his hands over the bread, blesses it silently; and it is soon after cut up into little pieces, and distributed among the congregation. With this ceremony of the Pain bénit, all my interest in the proceedings vanishes, and I take my leave of the kirk, still writhing under the incongruous associations of the man in shirt-sleeves and the grinning shepherds. Such things, to impress the imagination, must be well done; ill done, they are disheartening. I do not believe in the theatrical business of the papal crown in wax candles; but the ceremony of blest bread is very sweet and simple, and ought not to have been marred by Bumble and the other monkeys.

As I walk homeward, the streets of the little village are still full of people, shouting and singing; but all is still by the time I open my garden-gate. Only one couple pass by, a man and a girl, and the man’s arm is where the arm of a lover ought to be, and the Norman girl is singing to this effect:

Soldat! vois-tu ces eaux dociles

Suivre le pente du coteau?

C’est l’image des jours tranquilles

Qui s’écoulent dans le hameau.

Tes lauriers arrosés des larmes

N’offrent qu’un bonheur passager;

Crois-moi, soldat, quitte tes armes,

Fais-toi berger!—

though he who embraces her is not a soldier, but a sailor just returned from the cod-fishing in Newfoundland.

Christmas morning comes, dry and chilly. The streets are crowded with gay promenaders; the men in their dark-blue blouses, the women in their coloured skirts, red hoods, and high Norman caps. All are laughing and singing. But my thoughts are otherwhere. My chubby friend, Christmas, with his hand upon his heart, appears before me in the shadowy proportions of a ghost. “Epicuri de grege porce!” he exclaims, sadly. “Instead of rosbif and plum pudding, I can only offer you a pot au feu.” Such is the decree. For have we not already tried to roast beef on our stove, and have we not given up the attempt in despair? and have we not discovered that, even if we could procure 319 the proper ingredients for a pudding, we could not cook it decently? There is no help for it, and we soon resign ourselves to circumstances. A pot au feu, to a man with an appetite, is by no means a contemptible meal. So we leave the preparation of dinner to our bonne, and sally forth for a promenade on the cliffs. As we cross the threshold, a band of carol-singers, youths and maidens, is singing:

Venez, bergers, accourez tous,

Laissez vos pastourages:

Un autre roi est né pour nous;

Nous lui devons nos hommages!

and a little further on, walks another, raising a chorus to a similar effect:

Le matin quand je m’éveille,

Je vois mon Jesus venir—

Il est beau à merveille!

All are merry as crickets—chirping, singing, shouting, kissing; old men and children, boys and girls, merry matrons and lively shopkeepers. The little café is crowded, and its rooms are filled with the rattling of dominoes and billiards. The water of life, at ninepence a bottle, is already beginning to moisten many eyes; but there is no gross drunkenness. A contrast to all the mirth around him, stands the young man who dwells solitary in the “Telegraph Office” opposite my window. He is standing at the threshold, elegantly dressed in Parisian raiment, gazing in dreamy melancholy on the gay promenaders; his air is dignified, though depressed; he is thinking of the gay life of cities at the festive season, and of the dismal fate which dooms him to waste his sweetness on the air of Étretat; and suddenly, with a deep sigh, he plunges back into his office—to enjoy a quiet game of whist with a dummy, or to exchange a dreary conversation along the wires with a brother-clerk at Havre. He is a painful spectacle, that young man. He dare not desert his post, since a message might arrive in his absence; yet who sends or receives telegrams here during the winter season. He seems to know nobody. He dines solitary every afternoon in the Hôtel des Bains. He has a bowing acquaintance with me and mine. But his life is dreary, the summer season cometh not, he is a-weary, and he would that he were dead. What is nature to him? What cares he for the study of character? He is young, très gentille, and he has been christened Eugène-Achille; his aspirations are towards the Parisian boulevards. He is painfully conscious, too, that his position here is a sinecure and a mockery. Some day he will be found, dead of inanition, at his post, with a smile of scorn upon his downy cheek, and the poems of Alfred de Musset lying before him, open at the famous epitaph.

Climbing the northern height, and passing by the chapel of Our Lady of Safety, I walk along the grassy edges of the cliffs, carefully picking my footsteps, since a false step might be fatal, and ever and anon pausing to peer down at the shore. The brain turns dizzy at the sight. The large pebbles look like golden sand below, the large patches of seaweed are as faint stains on the water, and the seagull, wheeling half-way down, is little more than a speck. Here and there on the brink of the cliff the loose grass and earth have 320 yielded, and rolled down; and ever and anon I hear a low rumbling sound, made by the pieces of rocky soil as they loosen and fall. But here is La Valleuse—a precipitous flight of steps, partly built in on the soft soil above, and partly hewn out of the solid rock. As I descend, the roaring of the sea comes upon my ear louder and louder. Now and then I come to a point from whence I can gaze downward—on the bright beach spotted with black seaweed, over which the tide crawls in foamy cream. The steps are slippery with rain and mire, and the descent is slow. At last, passing right through the solid rock at the base, down a staircase dimly lit by little loopholes that look out to sea, I emerge on the shore, and see the huge cliffs towering precipitately above me. Close to the spot on which I stand, a huge piece of earth has just fallen, and small fragments are still rattling down like hail. Close before me, to the right, towers the Needle of Belval—an enormous monolith of chalk, standing at the distance of four furlongs from the cliffs, with the sea washing perpetually around its base. Its form is square from head to foot; but the sea has so eaten at the base that it seems to stand balanced on a narrow point, and the beholder expects every moment to see the huge structure crash over into the sea. The seagull and cormorant, secure from mortal intrusion, build their nests upon its summit. Regarded from the cliffs it appears like a great ship floating shorewards, with the white foam dashing round its keel, and the birds screaming wildly around its sails. But hard by, round yonder rocky promontory, is a sight still finer. Passing round I find that the cliffs, on the farther side, turn inland, and before me, at a distance of a hundred yards, is a huge flat hollow in the rock. That is La Mousse, so called on account of the thick green and yellow moss which covers one side of the hollow to the height of a hundred feet. At this distance one sees nothing remarkable, but on approaching nearer a sight of dazzling beauty bursts upon the gaze. From the projecting rocks above pours a thin stream of water, which, trickling downward, spreads itself over the moss and sparkles in a million drops of silver light; in one place scattering countless pearls over a bed of loveliest deepest emerald; in another forming itself into a succession of little silver waterfalls; and in a third gleaming like molten gold on a soft bed of yellow lichen. It is such a picture as one could never have conceived out of Fairyland—a downy mass of sparkling colours, played over by the cool soft spots of liquid light, and looking, with the great cliffs towering all around, and the windy sea foaming out before it, and the sea-wrack gathering darkly; as if about to destroy it, near its base. Never was sweeter spot to woo in, to kiss in, and to dream in! As I pass away, looking backward as I go, the silver drops melt away again like dew in the sun, the moss looks dry and shady on the cave, and the beauty I have witnessed seems like enchantment—the vision of an instant. But the low, faint murmur of the water is still in my ears, faint and sweet and melancholy, and my brow is yet wet and cool with the spray the invisible spirit of the place has scattered over me!

But I must hasten. The tide is rising quickly, and if I do not round the promontory with speed, it may go ill with me. As I pass the needle again, the waves have risen round it, and are beating against it in white foam, trying 321 with all the might of waves to drag it into the gulf. But it stands firm, and will in all probability do so for many a year to come. Looking in the direction of Étretat, I can see the spot where lately stood the Trou à Romain, midway up the cliff, in the rocks only lit upon by wild fowl.

Romain Bisson was a fisher of Étretat, and had been accustomed from infancy to range these shores in search of shell-fish, and to gather the sea- wrack in order to make soda,—the latter, in these days, a thriving branch of industry. His solitary life, the habit of constant communion with wild nature, joined to the semi-barbarous habits of his parents, made him a sombre and moody man while still very young. He had no friends save his parents, he made no acquaintances, but kept all his brother fishers at a distance. He had never rambled beyond these cliffs, and knew nothing of the great world that lay around¦ him. At the beginning of the present century came the imperial conscription, and Romain was ordered to leave Étretat and fight for his country. The other conscripts were gay as larks at the prospect, for Frenchmen are soldiers by instinct; but it was far otherwise with Romain. He was no coward, but one whose wild daring had on more than one occasion filled the fishers with wonder; yet the thought of quitting mother and father, and these wild waves that were his only playmates, was more than he could bear. He would rather leap from the heights and die. Encouraged by his parents, he took refuge in a hole midway down the cliffs, and so evaded those who were searching for him high and low. His parents, at dead of night, let down provisions to him by a cord, and supplied him, moreover, with wood for firing. The lad tolerated his solitary quarters, and remained in them throughout the course of a whole year, 1813. One night, however, some fishers in a sailing-boat, returning from the open channel, perceived to their astonishment a bright light in the centre of the cliffs. Crossing themselves and calling on the Virgin, they spoke of what they had seen, and were speedily confirmed by others who had had the same experience. The coastguards, hearing of the affair, suspected a nest of contrabandists, and kept sharp watch. It was soon discovered whose hands lit the fire, and the news spread that Romain was living in the cave. The authorities flocked to the foot of the cliff. They summoned him with a speaking-trumpet to come down. “I will never be a soldier!” he shouted back. They threatened, if he did not descend, to take him by force and have him shot. “Good,” he returned; “I would rather die than be a soldier.” They attempted to ascend, but in vain; and of what good were ladders to reach a height of two hundred feet. Certain daring men volunteered to go down by ropes from the top of the cliff; but Romain seized and shook the cords, and they desisted just in time to save their necks. They began cutting steps below; but a shower of huge stones soon made them give up the attempt in despair. They rushed to the sous-préfet. “The example is a dangerous one!” cried the functionary; “he must be taken, dead or alive.” So after more parleying, they began popping at Romain with their guns; but he was safe in his cave, and retaliated now and then with stones and boulders. The siege continued for four days. On the fourth day, Romain found all his provisions gone. He was fainting for thirst. He must make his escape or perish. Now, 322 the cliffs in whose midst he lay secure were at least three hundred feet in height, and entirely perpendicular; but almost under the cave, and leaning against the cliff, was a rock one hundred feet high, and projecting about fifteen feet seaward. At high tide the sea dashed right against this rock, rendering impossible all passage from side to side, but leaving a narrow space of dry shingle to right and left. Fortunately for Romain, it was then full moon. There was full sea by ten at night. In the rock, and in the full tide, lay his only hope. He spent the whole day collecting huge stones. As the tide crept up, Romain suffered none of the soldiers beneath to remain under his cave; but compelled them, by fearful showers of stones, to take refuge on the other side of the rock. Nor did his volleys cease till it was high sea, and the passage beyond the rock was impossible. In the full moonlight he emerged from his cave, and commenced to descend, aided only by his feet and hands. The soldiers on the other side fired at him again and again, but he continued his way undaunted; and passed down uninjured behind the rock, leaving the baffled soldiers wondering at his courage and cursing his success. Next day his blouse and sabots were found on the shore, but he himself had disappeared, and they sought him in vain.

He turned up, however, a year afterwards, when the amnesty granted to deserters made it safe to appear. But he was changed. There was a wild light in his eyes; the sufferings he had undergone in the cavern, the strange visions of the long stormy nights, the dreamy terror of it all, had made him mad, though harmless. For ten years he haunted the cliffs, a wild woebegone man, supported by public charity; but finally, in a wild fit, he leapt from the heights up yonder and was dashed to pieces.

As I reach the summits of the cliffs again, the sun is slanting to his rest, though it is only three o’clock. The cloudy west is stained in deep crimson light, against which the grassy hills, and fresh-ploughed fields, and squares of trees, by whose foliage the farms are hidden in summer, stand out in distinct and beautiful lines. So I hasten homeward. By the time I enter the village, the merry-making has reached fever heat, and not a few of the virtuous villagers are tipsy. There is little singing now, only loud laughing and shouting. The telegraph clerk is walking sadly to his silent meal.

During the whole week these festivities last: the singing and promenading, the tippling in the cafés, the romping and the flirting; but the climax comes on New Year’s Day. As I dress in the morning, a sound of Babel deafens me—singing, shouting, screaming, barking of dogs, rattling of carts. People are pouring in from all the farms and detached houses round about. Little fathers, driving knock-kneed horses, and seated in carts with fat mothers and bawling children; buxom lasses trotting on solemn ponies; the diligence from Fécamp tearing up the street, crowded from top to bottom and hung with garlands. Opposite my door the men are stopping the girls, snatching the privilege of a new year’s kiss from buxom cheeks, and some of them, more amorous than powerful, getting tumbled over into the dirt by the strong hands that will yet wear big rings and lead sharp children. Head-dresses are torn, dresses rumpled, blouses rent, in the merry scuffle. Everywhere, among the bigger folk, jump little ones, sucking chocolate and bonbons. Papas 323 and mammas, uncles and aunts, meet and chatter and kiss. The very dogs at the street corners—a numerous group—are sociable and merry with each other, and bark cheerily, without malice; among them, regarded with great respect, is my white ruffian, “Bob,” who doesn’t understand their manners and customs, but gets on famously by bullying and swearing. Only the telegraph clerk is unmoved; for a moment, he is seized by the weakness of humanity, and seems about to throw his arms around his next- door neighbour the tobacconist, who passes by with an enticing look; but his mind reverts to his wrongs, he conquers the weakness, and remains firm and patient. Indoors and out-of-doors, it is the same thing. Brothers, sisters, aunts, uncles, cousins, all sorts of relations by birth or in law, are clattering in their sabots along my passage to salute the Captain and his family—to kiss each other on both cheeks, sip a petit verre, and go off, happy, to repeat the same ceremony elsewhere. In the lobby, awaiting me, is a tiny independent-looking fellow of seven, clad in fisherman’s blouse and big sabots. “I salute you, m’sieu,” he says, with a polite bow, “the bonne année.” I have never seen my visitor before, but I thank him with a profound obeisance. But instead of going away, he stands in silence, gazing expectantly up at me. I ask him if he has anything more to say. He smiles compassionately at my ignorance. “It is customary,” he says, “at the new year, to give to the boys—sous; some, the poorer classes, m’sieu, content themselves with giving one or two; but others, more liberal, give more—from five to ten sous. Give me what you please; I shall be content.” Delighted with his coolness, I reward him to the height of his ambition. He places his hand upon his heart, bows again, and walks away; but he is not far from the threshold when his boy’s blood gets up, he gives a peep round to see if I am looking, and satisfied in that particular, bursts into a run and a shout. I naturally expect that he will put his comrades on the qui vive, and that I shall have more calls of the kind. But no! he is a boy of honour. Having succeeded with me as a private speculation, he is too high-minded to make me the public prey.

For many days, then, the little village is by no means the quiet spot I described it to be in my first article. So noisy are the streets, that it is difficult for one to write, impossible for one to compose; no wonder, therefore, that these notes seem made a little at random. Twelve days after Christmas comes the Day of Kings (Jour des Rois)—our own Twelfth-night. This day, in Étretat, and throughout France, is the great grand day of the children. Great is the glee. The air showers fruit, toys, and bonbons—of which last grown-up people partake in such a way as to give the observer a sense of stickiness which lasts for days. The Captain gives a grand children’s dinner, to which the little ones flock joyfully, attended by their relations. It is a pleasant affair, but conducted with dignity. There is no undue noise, no screaming, no crying. French children know how to behave themselves. These fishermen’s offspring—from Mademoiselle Bébé, aged two, to Monsieur Achille, aged ten—are little ladies and gentlemen. They sip their potage cleanly, they pick their bones elegantly, they dally with, instead of devouring, the dessert, and talk with subdued enjoyment. Happy as any there sits the bronzed old Captain, at the head of the table; yet he is a 324 disciplinarian, and would be shocked at an English children’s party. I show him a letter which Victor Hugo has written to a little boy who wrote thanking him for the pleasure he had had in perusing Les Enfants (!) The Captain thinks it beautiful; and as nothing could better show how different French ideas are from English ones, I subjoin a translation of it:—

“I have owed you a reply for a long time, my dear little child; but, see you, I have very bad eyes, and you must excuse me. The doctors forbid me to write; I obey the doctors as you obey your mother! Life is passed in obeying; do not forget that. But you, who are little, are more happy than I. At your age, obedience is always sweet; at mine, it is sometimes hard. You see, then, what has prevented me from writing to you. Farewell, my little friend!—become great, and remain wise.

“VICTOR HUGO.”

Only a Frenchman could have written that, and fancied it the real thing; only a French child could have perceived its drift. The majority of the little ones here, at the Captain’s dinner, would like it—not really understanding it, of course, but having a dim notion that they were good little people. What did the “little friend” think of it, I wonder? Enjoyed it, doubtless, and told his pretty maman that he would obey her ever, ever. O for a sight of the letter which Michael Angelo Titmarsh, who understood French character thoroughly, would have written to such a child!

As it grows dark, the children sally forth into the streets, singing carols and dancing. Each carries a pole, at the top of which is a lantern, made of coloured paper, and lighted with a piece of tallow candle. These lights look very pretty in the deep darkness, and even grown-up folks do not disdain to carry them. When a lantern catches fire, it is fine fun to the little ones. But to-night the noise of singing and shouting dies away earlier than usual. It is the children’s feast, and the children must go to bed betimes. When the moon is fairly up in heaven, they are all in their cots, dreaming of fairy lamps and sweetmeats; and instead of their innocent voices, the murmur of the sea is heard along the streets. Indeed, after this Day of Kings, there is little human sound in Étretat to drown the eternal crying of the waters; for the gay season is over, and the work of the new year has begun in earnest.

JOHN BANKS.

_____

From The Argosy - August 1866 - Vol. II, pp. 243-248.

ÉTRETAT IN THE BATHING SEASON.*

NORMANDY the beautiful has once more assumed all its summer glory. The air is one bright burst of sunshine. The tree-capped hills freshen the jaded eye with their intense greenness, while everywhere across the happy valleys stretch the golden yellow fields of colza, plenteously interspersed with poppies of profoundest crimson. In deep wind-swept patches the wheat waves its yellowing ears. Nested in the invariable square of tall trees, each farm or homestead sends into the air its pleasant scents and sounds; nay, every village is embowered in foliage, and its presence would be unguessed of by the passing traveller save for the glittering spire that towers above the greenery, and points to heaven— Faith’s finger pointing up to God, as some modern rhymester ingeniously expresses it. The absence of hedges—those delicious essentials to English landscape—is not long felt by the English visitor, who soon becomes accustomed to the fine though brilliant contrasts of colours to be found in Norman landscape. As I ride over the steep hills from Fécamp, after inspiriting myself with a little sip of the fine liqueur made by the monks of the Benedictine Abbey, the road affords constantly changing pleasures: now a long avenue of cool shade, with tall fir-trees on either side, and the sunshine drawing white webs through their topmost branches; again, a shining expanse of gold and red, with the quivering light pouring down on coleworts and poppies; and not seldom, a little village, with old women and maidens plying their ancient spinning-wheels in the shade of cottage doors, and blue-bloused loungers puffing their halfpenny cigars on the wooden forms outside the auberge. There are a few pedestrians on the road, and many old-fashioned vehicles. Now and then, a pretty girl, seated on a donkey, with a cumbrous wooden frame to support her shapely lower limbs, jogs by in holiday gear, fresh fruits and vegetables ranged around her, speedily to be disposed of in the market-place of Fécamp. From sun to shadow, from shadow to sun, I pass at leisure, until I gain the point where the highway curves round the shoulder of a great hill; and then, what a prospect opens itself before me! To my left hand stretches the fertile hollow of the Grand Val, —fields golden and red, deep-green clumps of woodland, quiet homesteads

_____

* See Argosy, vol. i., pp. 165, 315.

_____

244 bosomed in their trees, and, running through the midst of all, the straight white line of dusty highway. The hills beyond, covered with soft moss-like grass and underwood of many hues, lie clear, and distinct against a sky flecked with feathery cirrus. Before me, at the mouth of the Grand Val, lies Étretat—a mass of fishermen’s cottages, old buildings, and modern chalets, glittering cheerily in the sunlight, save where it is overshadowed by the great cliffs that rise to north and to south, and touched by the very lips of the sea. Yonder, diminished by distance to a small aperture, is the huge Porte d’Aval; and yonder, on the other side, on the brow of the cliffs, stands the solitary chapel of Our Lady of Safety. The sea is green and calm as glass, and a boat with furled red sails slowly makes its way, with a motion of oars, to the point where village and water meet. There seems no stir of life anywhere. All is still and beautiful. But while I pause to gaze, there is a jingle of bells behind me, and the diligence goes rattling down the hill in a cloud of dust. I follow at leisure.

It needs no sorcerer to guess that Étretat is no longer the charming solitude wherein I was so happy last winter. As I enter the principal street I pass several pedestrians attired after the last Parisian mode—more than one elegant carriage occupied by wealth and millinery. Shops which were hermetically sealed during the winter are thrown open for the display of all the thousand unnecessaries that flesh delights in. The tradesmen stand in their doorsteps, watching the diligence as it rattles by, and noting new arrivals. The young man at the telegraph office lounges in the threshold, looking radiant as the day. A pet poodle with a silken collar yelps at the diligence. Prettily adorned heads are popped out of first- floor windows. The words “Table d’hôte” are written up at every corner. In a word, the gay season has commenced. The dry boats are again wheeled down to the water; the flocks delight not in fold, nor the shepherd by the fire; Venus Cytherea leads the promenade under the burning sun; while the Parisian nymphs, linked with the Graces, holding the hands of the bathing-men, lie on their backs in the water and pop up alternate feet!

There is no lack of friendly faces to welcome me as I join the crowd in front of the hotel, where the diligence has just halted. Madame the hostess, shiningly bedight, drops a pretty curtsy and recognises me with a winning smile. Butcher and baker doff hats politely. The fat chef gives an oily bow. Only one fellow seems surly, and that is a bloated ostler, whose face brings up an unpleasant recollection. For when, in winter time, I abode here, it was my necessity to purchase meat from a savage butcher given to drinking—a horrible sans culotte ruffian, whose hand quivered like an aspen leaf as it handled chopper or cleaver, and who cut you a mutton chop as if he would better enjoy the job of cutting your head off. This amiable person drank on an average about six bottles of cognac daily, and was in every way the terror of his poor little wife—a sweet and delicate creature much younger than himself, who bore him two pretty children. Slowly but surely the little woman began to pine and sicken: her life was one of almost mortal terror, brightened by no gleam of domestic cheer—for the very little ones dared scarcely breathe in the presence of their father. On the day of the Feast of 245 Kings, when the children make merry with masks and coloured lanterns, there was a gathering at the board of my landlord, the captain; and among the happy faces there, I noticed those of the butcher’s two children. Their mother brought them, and became quite merry with her relations. The Brute was off on some distant expedition. The happy afternoon passed. Hastening home with her children, the little woman found her husband lying in the shop stupified with drink. What else happened, I know not; but three days after the woman was a corpse. She was choked by a long- standing ulcer in the throat, and her danger was unperceived until all hope was over. Entering one morning, a neighbour found the children crying, the wife stretched dead on her bed, and the husband lying delirious on the floor. They tried to rouse the man—they led him to the bedside—they showed him the pretty dead face; but he only glared and shivered, and called for drink. As the light dawned on him, he crept away into the dark like a dog. More cognac strengthened him, and his drunken frenzy soon made doubly hideous that house of horror.

It is this very fellow’s face, then, which looks so surly on me in front of the hotel. From a thriving tradesman, the Brute has dropped into a sullen, sodden hanger-on of the stables; and in his eyes there is less speculation than ever, and the imbecile glare of normal intoxication is rapidly deepening over his features. With a shudder I make my way into the hotel, and speedily find a vacant corner at the table d’hôte, which is just commencing. The gathering is not large, but select,— fantastic costumes predominating. There are no English present; to them Étretat is yet terra incognita. But there are visible an eccentric lady with a little bull-dog in her lap, two or three pretty girls, a chatty married lady, some commercial travellers, a languid youth of the genus swell, and a French man of letters. It is on this last individual that I concentrate my attention. He has passed the sunny side of life; his flowing locks are grey; but his smile is juvenile, his dress gay, his jewellery fantastic. His name is Eugene de —— something or other, and he has written two or three romances—a tale of Bohemia, a tale of the demi-monde, a tale of a wicked married lady with the faintest hint of a moustache. He is a charming child of nature. He whispers prettily wicked things—O so innocently—to the married lady at his side. He tells little anecdotes about Paris, with a dark hint here and there about a terrible love-drama in which he himself has been a principal performer. He would be very spirituel if he would eat less. I am lost in wonder at the number of little dishes that he manages to empty, with his napkin tucked under his chin like a bib, and his little white fingers darting here and there at their own sweet will upon fresh prey.

It is growing dusk when I sally forth. The natives throng the streets, but are very quiet and subdued: the greater light of Paris awes and humbles them. Winding my way through the narrow streets, I speedily gain the embankment immediately above the beach. All is changed here. Gay promenaders chatter everywhere. The sailors and fishermen cluster round the old-fashioned boat-houses; but they exhibit a stiller and a hungrier air. Pretty bonnes trip among the cordage, guiding odiously well-dressed 246 children. But what gingerbread edifice is this obtruding its wooded tawdriness just above high-water mark? It is the Casino. Transported mysteriously away, like Aladdin’s palace, at the end of every autumn, it reappears mysteriously at the beginning of every summer. It contains, besides the dancing-chamber, a very excellent reading-room and library, and a commodious billiard-room. In front of it is a parade, overlooking the sea, with seats for the weary and swings for the agile. Situated here, among the simple cottages and boat-houses of the fishermen, and between the two towering precipices of the Porte d’Aval and the Coté du Mont, the Casino seems singularly out of place. The natives, indeed, regard it as an innovation; and the very sea, wrought to frenzy by the contemplation of such flippancy and flimsiness, has attempted to demolish it more than once. Nevertheless, a stroll on the parade in the deepening twilight is by no means disagreeable. It is something to see such pretty faces and such bewitching female costume as throng here at present. I have not seen an ugly lady since I entered the village. The amusements at the Casino to-night are very harmless. Some languid young men are playing at billiards. One active young man is having a swing. A few gentlemen, with their wives and daughters, are seated in the reading-room, and one stout old fellow, seated in the midst of a small group, is reading aloud, translating as he proceeds, from the English papers. There are two cases of flirtation on the parade, where, by the way, the great Eugene stands puffing his cigar, gazing seaward with a patronizing smile, and taking creation generally under his protection.

When, after a brief interval of deep twilight, the moon arises over the water, the scene is filled with a strange beauty. Far above one, in clear outline against the sky, stands the little chapel on the mount, and underneath it the tall chalk cliffs gleam by fits in the moonlight. It is low tide now, and lanterns gleaming down yonder on the strand show that the women are busy at the fountain. Beyond them is the Porte d’Aval, with its vast cathedral-like surroundings, and its dark base of rocks and seaweed. Only the low sound of footsteps, and the faint wash of the sea breaks the stillness; till hark! the bells of Notre Dame, sounding sweetly inland, call the faithful to prayers. I speculate what kind of an effect surroundings like these have upon the fashionable promenaders around me,—transported hither, with the Casino, like a bit of Paris carried bodily and by magic to the brink of the sea. Here are to be found few of those distractions so abundant in the capital. Here are only the moonlight and the still sea. I fear many of the Parisians think at heart that Étretat is very dull; but it is fashionable, and that goes a very long way in its favour.

Soon after the moon has arisen, the group of promenaders greatly increases; for a sound as of twanging fiddles is heard from the Casino. The chief hall is brilliantly lighted up. A small fiddle-band, conducted by a bland gentleman in white kid gloves, occupies the central dais, and forms and chairs are ranged irregularly around. Now begins the formation of a very pretty picture. While the band dashes gaily into the performance of Offenbach’s last morceau, in troop ladies, gentlemen, and children, arranging themselves in little family groups all over the hall. The ladies, attired in the most provoking negligence, 247 fascinatingly and studiously careless, occupy themselves in sewing, knitting, and weaving fancy-work; nay, one determined matron is actually adorning what looks very like her husband’s nightcap. The amusement to-night is an instrumental concert; and as the music selected is excellent, and the execution by no means bad, the effect is very charming. You can, if you please, seat yourself, as I am doing, just outside in the moonlight, and contemplate the sea, and listen all the while to the melody of the band. Fix your eyes on the Porte d’Aval, where the white sheen glimmers, forget the gay folly in your neighbourhood, and hearken to a soothing murmur that was once a sweet trouble within Mendelssohn’s brain. What can be more delicious!—the music, the moonlight, and the soft undertone of the breaking tide, whose faint phosphorescent foam-line is glimmering yonder! Very pleasant it is, also when the band is playing from Gounod, to gaze into the hall, surveying the pretty faces bent over their fancy-work. There is a grace of purity about most of these French women; they have the sweetly confident air of innocence. They display none of the bad taste and awkward vanity so conspicuous in English watering-places. The very children behave themselves like little gentlemen and ladies.

As I betake myself to slumber, the music still lingers in mine ears, and seems the distant murmur of the subterranean river, on whose sunless banks, splashed with salt from the high tides, the Roman city lies in ruins. I arise betimes, and find the morning sunshine streaming golden over the shore, and the shadows of the cliffs falling long and cool into the glittering sea. The beach is gay and busy. All around the little cluster of bathing-boxes lying just under the parade, the visitors are grouping themselves to watch the bathers. The tide is well in, and the fun has commenced. Zephyr the bathing-man paddles a boat, to which is fastened a flight of wooden steps for bathers to rest upon, to and fro at a distance of a few yards from the shore; while the younger Zephyr plunges clad into the water, assisting the confident and encouraging the timid. Two tender creatures float on their backs close to his boat; and yonder, two or three hundred feet from the beach, three pretty faces float hither and thither, rosy with the kisses of the amorous waves. Mark that troop of ocean-sylphs tripping down over the shingle. Large light cloaks conceal their fair forms; but as they reach the edge of the sea, they fling their cloaks away, and appear attired in fantastically ornamented jackets and loose pantaloons. Then, with a ringing laugh, into the sea they plunge, scattering the bright water around them, and swim seaward, brightening the water as they go like a troop of Nereides. Maidens of the brine, they put to shame yonder shivering fellow, who crawls in water knee- deep and shivers through every limb. The sun strikes on their faces, glorifying the golden hair of the beauty who takes the lead. They are quite at home in the water. It is an odious comparison, but they swim as finely as frogs, playing all kinds of antics as they speed along. Yonder is an angel rolling over and over like a porpoise. See, now, they all join hands, and float silently side by side upon the water; till, with a silvery burst of laughter, they dash the foam from their faces, and swim onward. O to have an hour’s marine flirtation with that golden-haired child of Thetis! That flirtations do take place under 248 such circumstances, I have heard on the best authority. It is reported that one young gentleman, who swam indifferently, followed out into the sea a young lady, who swam excellently; that, panting with emotion and exertion, he assured her in the briefest possible manner of his attachment, and almost choked himself in the attempt to seize and kiss her hand; that, floating upon his back, he explained quietly his position and circumstances, and breathed words of tenderness, while the fair one again and again plunged under water to conceal her blushes; and that, finally, when they swam to shore, the daring youth had been accepted, at the cost of being almost paralyzed with cold.

Yonder is a party bathing en famille, after the manner of Leech’s sketch. Papa very fat and merry, mamma fat and clumsy, and the younger branches divided into two sections—the frisky and the fearful. It is great fun when mamma drops down in a sitting posture, and kicks and cries in a dreadful effort to regain her legs. But whom have we here? A tall, stately figure, wrapt into a theatrical-looking cloak, stalks from a bathing box, and strides seaward. It is the great Eugene. A confident smile brightens his features; his breast is filled with manly daring. He gazes patronizingly on the sea—nay, pityingly, as on an easily vanquished antagonist. He is Byron in imagination, and about to cross the Hellespont. He flings off his cloak with the air of a gladiator. He steps into the water. The smile begins to fade from his features. Another step, and yet another. A wave breaks upon him; he shrieks, and tumbles shuddering into the arms of young Zephyr. A rapid conversation ensues. Zephyr seizes the hero’s hand, and points seaward, but is resisted with wild gesticulations. Zephyr is firm, however. He drags his prey breast-deep, and then, by an ingenious movement, topples him over headlong. For a moment nothing is visible but the heroic legs; then the face emerges, but ah! how changed. Horror and agony are depicted on every lineament. Gasping, panting, spluttering, stumbling, Eugene makes for the shore, and pausing where the water is knee-deep, lies shiveringly down; and there he securely disports himself for some minutes. When he emerges, dripping like a sea-god, the air of confidence is his again, and he stalks up the shingle with the air of an ancient athlete.

With the morning bath the business of the day finishes, and visitors have little to do until evening, save to visit the places of interest around or amuse themselves in the bosoms of their homes. Yet the life seems very pleasant. There is so much in nature that is beautiful, so much in the manners and customs of the natives that is interesting. For my own part, I have made up my mind to pause here for a time and enjoy myself, quite persuaded that there is no more delicious summer residence in France or England. It is time that other English people followed my example; and I hope that what I have written may induce them to do so. They will soon conquer the prejudice that the French style of bathing is indecent. After a few weeks here, they will be virtuously horrified when walking, at the bathing hour, on the beach of Margate or Ramsgate.

JOHN BANKS.

_____

From The Argosy - September 1866 - Vol. II, pp. 306-312.

A WEDDING AT KOÄTSPLOU.

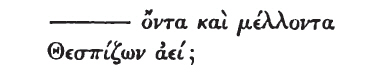

THE Tailor of Koätsplou is one of the merriest little fellows in the world; wit scintillates in his little blue eyes, fun lingers in the dimples at the edges of his mouth, and there is humour in the very antics of his little legs. How he manages to get through the ordinary work of his profession is to me a mystery; for on all occasions on which we have encountered, he has never kept still for a moment. He jumps, he skips, he snaps his fingers, he gesticulates. He is as restless as the Ignis-Fatuus in Faust, and might truly cry with the same—

Nur zickzack geht gewöhnlich unser Lauf.

Yet he is a great man for all that. In Brittany every tailor, if he possess the slightest mother-wit, can be a great man. In the first place, he is a poet, and as such, occupies a privileged place at all feasts and merry-makings, where he shines and chants in a halo of popular tradition. Secondly, he is a musician,—can set his own words to rude music, and accompany himself on the fiddle. Thirdly and lastly, he is the recognized go-between in all love affairs, the arranger of all trothplights, the presiding genius of all weddings. Should an ardent lover languish in bashful fear of avowing his passion, he applies to the tailor, who straightway undertakes his suit, and woos by proxy in such 307 honied rhyme as would melt a heart of stone. Should a maiden desire to encourage some youth who is in danger of losing a golden opportunity, she quietly hints to the tailor that her heart is not unfavourable to the silent one—and the silent one must be very dull indeed if, after that, he lacks animation and relinquishes the rosy prize to another. There is no love-mission, however delicate, that the tailor may not undertake; and he is well known to be as secret as the grave. To the other pursuits and functions incident to the tailor’s position, my friend of Koåtsplou adds that of village barber. He not only shaves the men, but clips the bright and dark tresses of the maidens: nay, I have heard it mentioned that he has actually a connection with a great house in Paris, which empowers him to offer handsome sums to such maidens as will part with their hair for money. Not a few Breton shepherdesses add to their savings the result of dealings in their own lovely locks, and thereby add something to their marriage dower; nor do they sacrifice much in personal appearance, since the snow-white cap common to Brittany covers alike the head adorned by nature and the head whose fair crops are being used for the adornment of some Parisian beauty. Now that the odious chignon is becoming so popular a portion of feminine attire, the maidens of Brittany are doing a fine trade; and the professional traders in hair, who have long haunted these districts, have multiplied themselves in every direction. The plump little beauties, I am sorry to say, are very fond of money. They would sell their sweet pink skins, if such a sale were possible.

I admire Johan, as my friend here is called, and he likes me. I am the occupant of a chamber, looking and smelling like a hayloft, in a little cottage, and am waited upon by a ghastly old woman, nearly six feet high, who calls me “her son,” and has almost gone the length of kissing me. Her daughter, a fat little beauty of sixteen, cooks me omelettes pretty decently, and roasts me apples, and serves me with coffee and cognac;—and on these, with the occasional assistance of a little broth, I manage to subsist. Hither, then, comes Johan, my sworn friend, though I have only been here a few days. In return for pipes of English tobacco, and other little delicacies from my travelling bag, he regales me with all the gossip, the poetry, the legendary and fairy lore, in which he is so rich. Habitually he speaks the horrible Kernewote patois, but to me, he can express himself in decent French. Very delightful are my evenings in his company. Often, too, he accompanies me on my pilgrimages to places round about, whiling the way with many a rude snatch of ballad-song, and charming the solitude with many a strange legend. For the country round about by no means possesses the charm of prettiness—a stretch of wild moorland, dotted with rocks and boulders, only relieved occasionally by a little wood, a few acres of cultivated land, or a running brook. Yet it is by no means deficient in wild grandeur. The atmosphere is full of superstition. The solitary dolmen, or place of sacrifice, is still visible in the midst of the windy waste. The Calvary, with its wild rude figures carved in wood, stands solemnly at the skirts of the little hamlet, frightening the timid and encouraging the pious. The good people still have their fairy rings in the meadow. The Korrigaun, or water-lady, still combs her hair in the lonely stream, wooing the unwary wayfarer with her fatal 308 song. Yet the inhabitants of Koåtsplou, like the inhabitants of most parts of the district of Cornouaille, are by no means of a gloomy disposition. In their gay recklessness and their love of practical joking, as much as in their piety and superstition, they bear a strong resemblance to the poor Irish; but they are infinitely cleaner and more polite. Though I have been only such a very short time among them, they have ceased to regard me with any suspicion, and are quite at home in my presence. The men, for the most part, are dark-haired sinewy fellows, with weather-beaten cheeks and shrewd faces. The old women are beyond conception hag-like and hideous,—as, indeed, they are all over this portion of France. The young women, on the contrary, are charming, and for the most part fair-complexioned—sly and merry to the last degree, very virtuous, and excessively fond of jokes which just pause on the borders of decency—partial, in fact, to what Béranger loved and sang so much, the gaudriole.

Who would not envy Johan his position among these buxom Breton maidens? He is in the prime of life, and not ugly, in spite of his red hair and grinning mouth; yet he has all the privileges of an old man; wherever he wanders, he may kiss, cuddle, and embrace at will. He does it all in so cold-blooded and business-like a way, that he arouses at once the envy and the indignation of a looker-on; for whether he smiles, or kisses, or embraces, his eye is ever bent on the sly trinket or bit of silver which he expects to be slipt into his palm. If he has love-business on hand, he is pretty certain to call at dinner-time, in the hope, almost the certainty, of being invited to take a share in the meal. To see Johan, in the centre of one or two merry maidens, would have quickened the blood of the leanest friar that ever abused King Harry on the divorce question. One he draws on his knee, another he encircles with his left arm, while his right hand pats the blushing cheek of the third. Then, his jokes, his whispered messages, his broad banter! He says things in a dreadfully open way—it is not his trade to mince matters. A girl may do anything with, and hear anything from old Johan—he is so harmless. A few of his fair confidantes, however, would blush if they knew how many of their secrets he had told to the eccentric Englishman over his pipe.

Johan does most of the wooing of the hamlet. The style is very simple. When a young fellow wishes to make a deliberate offer, he fees Johan, and acquaints him with the full particulars of his suit. Thus commissioned, and bearing a branch of broom, my friend dresses himself in holiday gear—a blue coat with glass buttons and a great hat decorated with ribbons—and sallies forth to the house of the lady’s parents. Of course they know beforehand the day of his visit, and the person on whose behalf he comes. When he crosses the threshold, the matter is soon determined. If the maiden turns her back on him, or ranges the logs upright on the hearth, he may as well be gone. Such a reception is not frequent. Usually, with the cries of “Aha, Johan,” “Welcome, Johan!” he is invited into the general room—the floor of which is the bare earth, the furniture a few benches and tables, and round the walls of which gleams the polished brasswork of the lits-clos, or closed beds. A white cloth is spread on the principal table, and the tailor is invited to partake of whatever is going. When he has satisfied both thirst and hunger, he 309 conducts the mother aside, and sets forth in the most glowing terms the advantages of an alliance with his client.. A debate ensues, for it is by no means etiquette for mamma to consent at once. All the art, all the blarney, of the tailor (or Bazvalan, as he is called, in virtue of his office), is called into play. He parries objections, he exaggerates merits, he insinuates into the mother’s heart the most delicate and honied flattery. At last the matron yields, Flushed with triumph, the Bazvalan, in the most poetic accents, announces the result to the maiden, who is flushed with joy. The day is named—the preliminaries are arranged—and Johan struts off to announce the glorious news, with any amount of flourishes, to his delighted client. The lover sees from afar off that he still bears the branch of broom, the emblem of success. If the branch of broom had been exchanged for a branch of hazel, that would be the proclamation of ignominious rejection.

I longed heartily to see a Breton wedding, and now my dear little Johan is about to gratify me. A month ago, he went through the above-described process in the house of a well-to-do farmer hard by, and the marriage is to take place this day. The sun is shining merrily, and all the hamlet is in commotion. I have arrayed myself in a suit of black to the amaze of everybody, my over-affectionate landlady included; and am about to amble over on an old horse to the spot where the pretty Tina dwells.

After a slow jog-trot over a mile of moorland I find myself among the crowd in the yard adjoining the bride’s house. A merry and a motley group they are. The bridegroom leads the way, mounted on a fine strong horse, which has just been taken from the plough. He is attended by his “best man,” similarly mounted; and among the others, who are seated on various kinds of sorry-looking nags, I notice one withered little old man doing his best to manage a refractory donkey. Both he and his donkey are well known to the people present, although he has come from a distant village. Indeed, I find that attendance at weddings is the old fellow’s occupation, and that he generally enacts the part of the Breutaër, or Bard of the Bride. There is much joking at his expense, but he pays as much attention to it as does his donkey. There is likewise much joking of another kind, the humour being founded on the broad and the indelicate; but altogether I am not sure that it is any more wicked or indeed more offensive, than might and would be found among the same class in England, where it is considered clever on such occasions to make remarks of such a nature as cause matrons to titter and maidens to blush. While the Breutaër passes quietly into the house and is lost to view—to reappear again, however, very soon—I look around and observe my friend Johan, who has just arrived—his obstinate little pony having been more than usually obstinate this morning. When in this state, Johan tells me, the only means by which he can induce his animal to behave like a rational pony, is to wring and twist his tail vigorously three or four times, and call him an ass. And now commences the business for which we are all of us assembled. Johan alights from his pony, and ascending the steps of the bride’s house, throws himself into the attitude of an inspired improvisatore, and emits some doggerel verses. He begins by invoking a blessing on all within the house in the name of the Trinity, and then, his 310 voice, becoming very melancholy in tone, hopes that more joy may be theirs than has fallen to his lot. “Why are you so sad, my friend?” inquires the Breutaër, gruffly, from within. Whereunto Johan replies, “I had a little white-fleeced lamb in my fold with my golden-horned little ram, but the great wolf came and has frightened my white-fleeced little pet away, and I know not what has become of her.” The Breutaër now opens the door, and looking very intently at Johan’s fine crop of red hair, says, “For a man to whom such a great misfortune has happened, you are in very fine condition. Are you going to a dance, that you have combed your beautiful hair with such care?” The bridegroom’s bard winces at this home-thrust; “but don’t insult me in my distress,” he loftily exclaims. “Have you not seen my white-fleeced little lamb? I am in search of her, and happiness will be mine no more till she is found.” The Breutaër avows that he has seen neither the white-fleeced little lamb, nor the golden-horned ram; and this so enrages the tailor, that he calls his brother bard all sorts of bad names. “The people,” he continues, “have told me that they saw my little pet fly to your farmyard for refuge from the great wolf.” But the bride’s bard persists in asserting that he has seen neither the little lamb nor the little ram. Whereupon the bridegroom’s bard, growing desperate, says, “My golden-horned ram will die if his white-fleeced mate be found not! My poor ram will die! I will go and look in your farmyard.” “Stay, my friend,” interposes the other; “I will see whether I can find your white-fleeced pet for you.” Then he goes away, and presently returns with a wonderfully pretty child. “Behold!” he cries, “I have not found your white-fleeced pet, but I have found a charming little chicken, which I present to you, old boy, that your soul may be gladdened.” “A delicious chicken, truly, Friend Thin-jaws,” replies Johan, “and were my golden-horned ram a chef among the cannibals, he would make of her a ravishing stew. But I must seek for my white-fleeced pet.” “Rest a moment, you donkey,” says the Breutaër, “I will search yet again:” and going into the house he returns this time with its mistress, a buxom dame of forty, who evidently enters into the ceremony with infinite zest, doubtless recalling the time when she played a leading, instead of a subordinate part, as now. “I have searched,” says the Breutaër, “but could only find this plump hen. Take her to your heart, old boy, and console yourself in your distress, for she will lay you plenty of eggs.” “What would my golden-horned ram do with so fine a hen? Besides, he is too young to feed on omelettes, and pines for his white-fleeced pet.” Thus speaking, the bridegroom’s bard pretends to make another rush after the missing lamb, but is again stopped by the bride’s bard, who insists on once more searching in person. This time he returns with the old grandmother, a dreadful-looking lady. “Everywhere have I searched,” he shrieks, “but only this old cow could I find. Take her, my friend, and perhaps even yet she may yield some milk for your white-fleeced pet, when you find her.” “Thank you,” replies the little tailor. “The cow, though old, deserves our respect, and I render to her my homage. But I do not want your chicken, nor your hen, nor your cow, and this time I must go to seek for my white-fleeced lamb myself.” “Ah! since you will take no denial,” exclaims the bride’s bard, “let us go together to your 311 white-fleeced lamb. She is not lost, for I have carefully guarded her from harm in a little fold made of all that is precious, and whereof the door can only be opened by the key of true love. He, he! There is your white-fleeced lamb all-beautiful, all-blushing. Her outward loveliness, I assure you, is surpassed only by the beauty of her mind, and the music of her pure heart is as the tinkling of sheep-bells on a sunny day.”

Hereupon, headed by Johan, who has already drawn his fiddle from a dirty bag, we all rush into the great room, where massive tables and benches, covered with plenty of nice things, are all ready for our reception; and there, in a truth, sits the bride, blushing in her gay gear—as sweet a little bit of pink loveliness as ever counted beads. A duck of a bride—or rather “a dainty little partridge of partridges,” as Johan gallantly terms her. In silk mantua, and embroidered cap, and stockings with delicious “clocks” upon her plump, shapely limbs, she flutteringly receives the bridegroom’s kiss, and the congratulations of all her friends. Mark those silver braids placed on her arm. According to the number of those is the number of thousands of francs she brings as a dowry. Four! That is four thousand francs, or about one hundred and sixty pounds sterling. So that little Tina is quite a bride of fortune. But an important part of the ceremony is about to be gone through. Tina’s papa, a jolly old farmer, who smells strongly of cognac, presents the bridegroom with a horse-girth. “Girdle her, my son!” he says, with a slight hiccup, and “girdle her! girdle her!” resounds on all sides. Thus urged, the bridegroom passes the horse-girth round little Tina’s waist, and the bride’s poet croaks the following doggrel song, while Johan faintly plays the air on his fiddle, and the wedding guests join in the chorus:—

Down in the field by the side of the farm,

What should I see but a fine young filly!

She frisk’d and she sported, and thought of no harm,

(He! he! thought of no harm !)

Her lips were like roses, her cheeks like a lily.

Ali! Ké! * the filly!

Her coyness is turning me silly!

CHORUS—Ali! Ké! the filly, &c.

A coat with gold buttons I wore, full of joy,

And seam’d with the silver were waistcoat and breeches—

Why, then, was the little one timid and coy?

(He! he! timid and coy!)

Why, then, did she tremble to hark to my speeches?

Ali! Ké! the filly!

She took my first wooings but illy!

CHORUS—Ali! Ké! the filly, &c.

But nearer and nearer she drew as she played,

And bent her white neck, and was kindly and gay with me;

I bridled her, sirs, and she wasn’t afraid,

(He! he! wasn’t afraid!)

I girdled her, sirs, and I led her away with me!

Ali! Ké! the filly!

She kisses with cheeks like a lily!

CHORUS—Ali! Ké! the filly, &c.

_____

* Ali! Ké!—Ho! Come!

_____

312 When the chant is over, Johan, who has hearkened with a savage sneer to the croaking of his rival, invokes all sorts of blessings on the bride, and (as far as I can make out) upon everybody. Little Tina cries, and throws herself into her mother’s arms. She rescues herself, however, to pledge troth with the bridegroom and exchange her ring for his, while the tailor rapidly repeats the “Ave Mary” in the local dialect. Then Johan claps hands, and the “best man” escorts Tina over the threshold, closely followed by the bridegroom, arm-in-arm with the principal bridesmaid. The bridegroom mounts his horse, and the bride is lifted up behind him. Then the others, men, women, and boys, are mounted on horses, mules, and even asses; the tailor cries, “Off!” and away they dash at a break-neck pace to the church, each man with a female clinging behind him. How the men shout! how the women scream!—till, in a panting crowd, they halt at the church gates.

The ceremony is soon over, and back they trot more soberly—little Tina quite fresh and confident, now that so much of the business is over. A ragged bagpiper has joined the troop, and fills the air with his wild music as they halt at the farm door. Great have been the preparations in their absence. Both indoors, and on the green in front of the house, are stretched tables loaded with eatables and drinkables, and the great room within is carpeted with white cloth and strewn with flowers. At the end of the board within, little Tina takes her seat, and garlands of leaves and flowers are hung over her. Then, after a prayer, all fall to, without and within. What a grinding of teeth! what a draining of flagons!

It would take me many a page to describe the rest of the festivities of the evening—the drinking! the dancing! the kissing! the song-singing! the wicked joke-making!

As the night advances most of the men are tipsy, and my friend Johan after a savage quarrel with his rival, has doubled his legs under him and sunk into a senseless heap. What more is there to do, and why do the guests linger? It is past eleven, and little Tina has yawned thrice. At last the bride rises, and her maids proceed—to undress her! That is a simple task, as she is well prepared, and the throwing away of outer apparel shows her clad in an embroidered night-gown of snowy white. How she cries and blushes as the bridesmaids pop her into the closed bed yonder. The bridegroom, looking very sheepish, joins her. Seated side by side in bed, they partake of soup, cake, and walnuts, while fiddle and bagpipes play, and all the guests join in a song. . . . But see! yonder is the chaste moon peeping in through the window. Shoulder the insensible Johan, cry “Benedicite,” and come away!

OUR IDLE VOYAGER.

[Note:

The quote from Goethe’s Faust (‘Nur zickzack geht gewöhnlich unser Lauf.’) can be translated as ‘Our course usually only zigzags.’]

_____

Back to Essays

|