ROBERT WILLIAMS BUCHANAN (1841 - 1901)

|

ROBERT WILLIAMS BUCHANAN (1841 - 1901) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

REMINISCENCES OF BUCHANAN

Among My Autographs by George R. Sims (1904) Fifty Years of an Actor’s Life by John Coleman (1904) My Story by Hall Caine (1908) A Stepson of Fortune by Henry Murray (1909) Some Celebrities I Have Known by Archibald Stodart-Walker (1909) Recollections of Fifty Years by Isabella Fyvie Mayo (1910) Mid-Victorian Memories by R. E. Francillon (1914) My Life: Sixty Years’ Recollections of Bohemian London by George R. Sims (1917) _____

Among My Autographs by George R. Sims (London: Chatto & Windus, 1904, pp. 17, 49-59, 90)

p. 17 It was Rossetti who was fiercely attacked by Robert Buchanan in his article “The Fleshly School of Poetry,” to which Swinburne replied in “Under the Microscope” with a wrath and bitterness which have never been equalled in a literary quarrel. Buchanan in after life regretted his attack on Rossetti, and made heartfelt amends in his later years. He told me once that it was the incident of his literary career which he most deeply deplored. ___

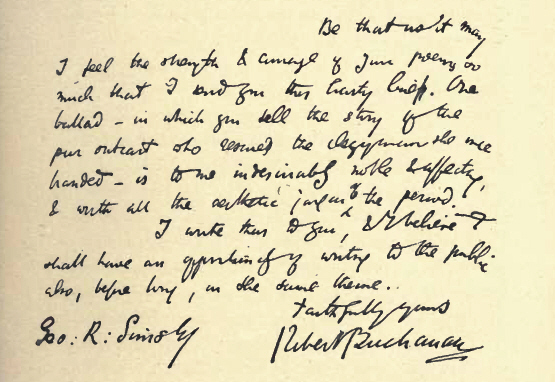

pp. 49 -59 VI Robert Buchanan was my friend and close companion for many years. I have most of his works, and among them many of the very early editions which are now rare. I have “Undertones,” the volume of poetry published by Edward Moxon in 1863, and “David Grey,” published by Sampson Low, Son and Marston in 1868; and I have those later works which he published with such extraordinary rapidity in the intervals of play-writing, theatrical lesseeship, financial worry, and much fierce letter-writing in and out of the newspapers. I have the books which he brought out himself at his own office in order to be his own publisher, “The Ballad of Mary the Mother” and “The Devil’s Case,” both “published by the author,” one in ’96 and one in ’97. 5 Larkhall Rise, Dear Sir,—Permit a disinterested reader to tell you how much he has been surprised and touched by some |

|

||||||||||||

|

of your “Ballads of Babylon.” I know by experience that such testimonies, when they come unexpectedly, sometimes convey pleasure; and it is also in my mind that long ago, when “I” also wrote poems of Babylon, a generous-hearted friend of yours, the late Mr. Tom Hood, wrote out of the fulness of his heart such words as gave me great content. The writer amply fulfilled his promise shortly afterwards in the pages of the “Contemporary Review.” Officer: Enter the church, Sergeant, and bring the fellow out! Of course that was set right at rehearsal, because the sergeant was played by a real sergeant, and the soldiers were real soldiers. The military words of command were substituted, and the sergeant did not argue with his superior officer. |

||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||

|

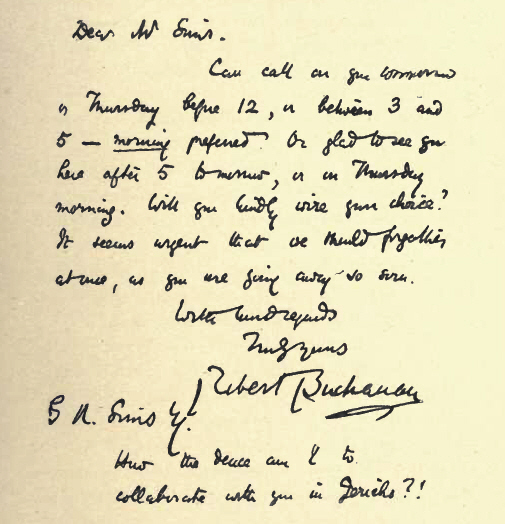

to Jericho is explained by the fact that I had written asking him to come to an early decision, as I wanted a holiday, and was thinking of going to the Holy Land: Dear Mr. Sims,—Can call on you to-morrow or Thursday before 12, or between 3 and 5—“morning” preferred. Or glad to see you here after 5 to-morrow, or on Thursday morning. Will you kindly wire your choice? It seems urgent that we should forgather at once, as you are going away so soon. With kind regards.—Truly yours, Our first play, “The English Rose,” made a good deal of money for all of us. Buchanan sold out after a time, and the Messrs. Gatti and myself gave him £2500 for his share. |

||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||

|

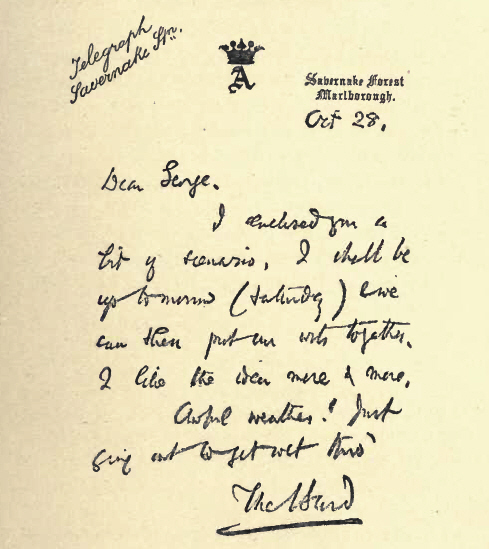

her brother-in-law by Miss Harriet Jay the critic objects to the insertion of a “reminiscence” by myself, in which “the Bard” is frequently mentioned. “We could have done with less of ‘the Bard,’” says the critic. Every one has a right to his opinion, but the story of Buchanan’s life would have been incomplete without a reference to this phase of it. He was always known as “the Bard,” and alluded to as “the Bard” by the little company who gathered constantly at his house on “supper-nights,” and at the little Sunday dinner-parties. It was a term of affection and respect bestowed upon him originally, I think, by his friend and frequent companion Mr. Henry Murray; and Buchanan himself, as the letter shows, had smilingly adopted it. The letter is written from the country seat of that Marquess of Ailesbury who was known to sporting fame as “Ducks.” Buchanan was one of a small party staying there for a few days: Savernake Forest, Dear George,— I enclosed you a bit of scenario. I shall be up to-morrow (Saturday) and we can then put our wits together. I like the idea more and more. The Bard. I have referred to Miss Jay’s story of his life’s work and his literary friendships. But there is another book, which may be published one day—the autobiography which Robert Buchanan had himself prepared, and in which he had frankly set forth his ideas of his contemporaries. ___

p. 90 Rochefort was a remarkable figure, with his erect bearing, hid French features, and his wealth of piled-up snowy hair. All the cabmen knew him, and I am bound to say liked him, for he was generous to a degree. To me he was always delightfully amiable, and he took a great fancy to Robert Buchanan, at whose house I met him more than once. _____

Fifty Years of an Actor’s Life by John Coleman (Vol. 2, New York: James Pott & Co., London: Hutchinson & Co., 1904, pp. 649-651, 652-654, 661) pp. 649-651 On the day when I commenced operations for my débût a crowd of authors, actors, journalists, and old friends came, some to seek engagements, others to congratulate me. First came Charles Reade, Wilkie Collins, and Tom Taylor to wish me God-speed. Next, a remarkable-looking man of forty and a girl scarce half that age, neither of whom I had ever seen before. He was clad in an ample Inverness cape of grey frieze, with a white muffler twisted round his huge neck. His fierce blue eyes asserted themselves defiantly through his blue binoculars. His hair was a mass of golden brown, and his beard of burnished gold. His assertant nose (too prononcé for Greek, yet not enough for Roman) and dilated nostrils, his leonine head and chest, combined with a certain “come if you dare” demeanour, suggested the very image of a Viking on the war-path. The girl was tall, slender, dark-eyed, dark-haired, clad in some dark clinging stuff, and there were even then suggestions of statuesque outlines, which indeed afterwards became more amply and superbly developed. He carried a huge, hideous “gamp,” pointed bayonet-wise at my breast, as if about to charge and pin me to the wall behind. The girl, who had evidently never penetrated Stage-land before, gazed curiously at me and the glittering paraphernalia of armour and jewellery scattered around, as who should say, “Where am I, and what manner of man is this player-king?” While they were doubtless summing me up, I took stock of them; hence I recall thus vividly my first impressions of the author of The Shadow of the Sword and London Poems and his pupil and protegée, the authoress of The Queen of Connaught. ___

pp. 652-654 Whatever diversity of opinion might possibly have existed as to the rendition of Henry V., there was but one opinion as to the splendour of the spectacle, which both Phelps and Greenwood and even Mrs. Charles Kean and Mr. Planché then generously acknowledged had never been equalled, while I am bold enough to assert even now that it has never since been surpassed. By the special grace of Dean Stanley we were permitted to photograph the Abbey and the Jerusalem Chamber, to model and reproduce the Coronation Chair and the mystic Stone of Scone beneath it. Mr. Kean was kind enough to lend me all the sketches and designs which had been prepared for Charles Kean’s sumptuous get-up at the Princesses’, while every scene, every costume, every weapon, every suit of armour, every trophy and banner were prepared from the highest authorities, after the designs of Mr. Godwin, the eminent archæologist. Permission was obtained from the Horse Guards for the pick of the British army to assist in the Coronation, the Siege of Harfleur, the Battle of Agincourt, the Royal Nuptials, and the Triumphant entry of Harry and Katharine de Valois into London. So extensive were the preparations that we had the greatest difficulty in getting ready for our opening. ___

p. 661 Soon after this I produced—at Brighton—an adaptation by the author and myself of Robert Buchanan’s noble romance, The Shadow of the Sword. I obtained great kudos in the part of the hero, Rohan Gwenfern, but when I brought the play to town during the dog-days (when every one was away) I gained neither money nor reputation by an experiment attempted under such adverse circumstances. ___

[Note: Coleman’s production of The Shadow of the Sword did not meet with Buchanan’s approval and led to a spirited exchange of letters in The Era.] _____

My Story by Hall Caine (London: William Heinemann, 1908, pp. 92-97, 222-223, 271-279)

pp. 92-97 Whatever the cause of the book’s immediate success, there can be no doubt that Rossetti himself took great delight in it, and that in the first flush of his new-found happiness he began afresh with great vigour on poetic creation, producing one of the most remarkable ballads of his second volume within a short time of the publication of the first. But then came a blow which arrested his energies and brought his literary activities to a long pause. ___

p. 222-223 I have one more memory of those cheerful evenings in the poet’s bedroom with its thick curtains, its black-oak chimney-piece and crucifix and its muffled air (all looking and feeling so much brighter than before), and that is of Buchanan’s retraction of all that he had said in his bitter onslaught of so many years before. One day there came a copy of the romance called “God and the Man,” with its dedication “To an Old Enemy.” I do not remember how the book reached Rossetti’s house, whether directly from the author or from the publisher, or, as I think probable, through Watts, who was now every day at Cheyne Walk, in his untiring devotion to his friend, but I have a clear memory of reading to the poet the beautiful lines in which his critic so generously and so bravely took back everything he had said: “I would have snatched a bay-leaf from thy brow, Rossetti was for the moment much affected by the pathos of the words, but in the absence of his name it was difficult at first to make him beheve they were intended for him. ___

p. 271-279 ROBERT BUCHANAN ABOUT two months after Rossetti’s death I was at work in my chambers in Clement’s Inn on one of my articles for the Mercury, when somebody knocked with his knuckles on the door, and, in answer to my call, came in. It was Robert Buchanan, whom I had never seen before, a thick-set man of medium height, with a broad fresh-coloured face, distinctly intellectual, but certainly not ascetic, or spiritual, or inspired. He had seen something I had written about Rossetti, with a reference to himself, and he had come to thank me and to reproach me at the same time. In a voice that had a perceptible tremor he said: _____

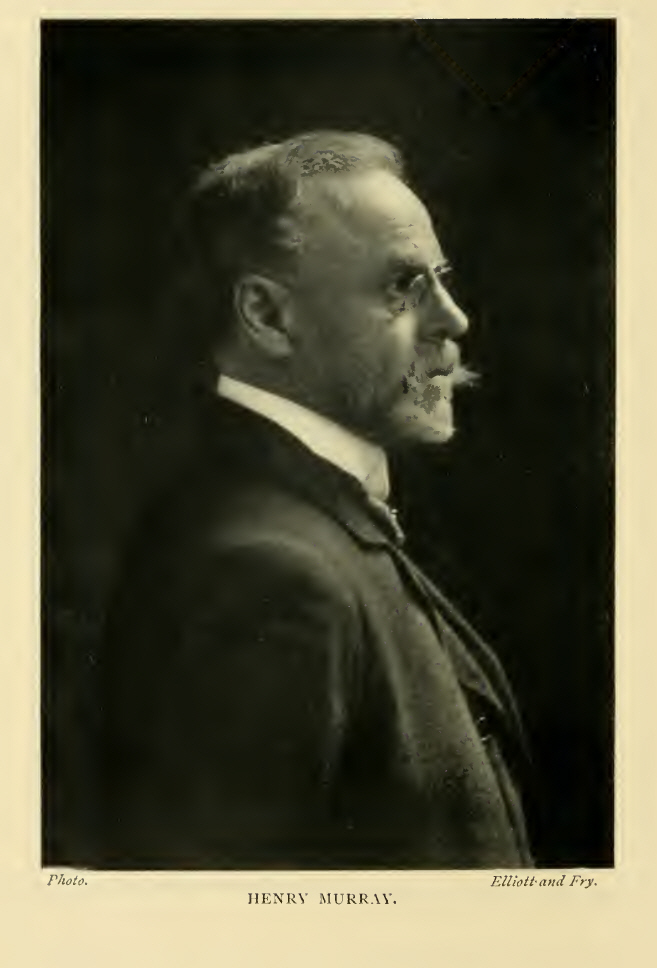

A Stepson of Fortune: The Memories, Confessions, and Opinions of Henry Murray (London: Chapman & Hall, Ltd., 1909, pp. 198, 204-237) |

||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||

|

p. 198 I may as well, while I am about it, make a clean sweep of the narration of my misfortunes in the merely literary line. In the year 1900, Robert Buchanan—of whom I shall presently have a good deal to say—was smitten with paralysis. His recovery was pronounced to be quite hopeless, and on the strength of my long and intimate connection with him I was commissioned by a young publisher, who had recently started in business, to write a critical study of his life-work. Buchanan lingered for nine months, and then died with almost startling suddenness, and the book was on the market within a week or two of his death. It went well, but, owing to the publisher’s retirement from business, it has disappeared from the list of the living as completely as the books I have already mentioned had done aforetime. ___

pp. 204-237 It was not long after parting with Christie at Nice that I made a journalistic liaison which resulted, in a rather odd and out-of-the-way fashion, in cementing the longest, firmest, and dearest friendship of my life. I joined the staff of the Hawk, a sixpenny weekly paper run and officered by a small crowd of cheery journalistic Ishmaelites, of whom one or two, including Augustus Moore and James Glover—the latter now and for many years past musical conductor at Drury Lane—were old friends of mine. It was an impudent, irreverent, utterly irrelevant and candidly libellous little sheet, which, by sheer dint of those qualities plus a good deal of slangy cleverness, rapidly became a power among that curious social contingent known as “The Smart Set.” Like the ideal Christian in relation to this passing world, I was rather in the Hawk office than of it, having neither the money nor the inclination to mix much with the crowd for which the paper catered. It had, or professed to have, a serious side, and it gave me chances which more “respectable” journals would never have afforded for the plain expression of my convictions on many subjects. I have always had a strong dash of l’esprit frondeur, and took full advantage of my liberty. The late Harry Quilter had just started his brilliant but short- lived Universal Review, and in one of his earlier numbers appeared an article by Robert Buchanan on “The Modern Young Man as Critic,” written with all that forthright candour which used to mark its author’s polemical utterances. Moore and myself were more or less liés with one or two of the people Buchanan most pitilessly attacked, and Moore suggested that I should reply to the article. The passage in which, in my “Critical Appreciation of Robert Buchanan,” I recounted the incident may as well do duty here. “Like a man in wrath, the soul “I don’t care a curse for your ‘scientific evidence,’” I have heard him say to a friend with whom he was disputing. “It isn’t thinkable that I should not meet certain people again. I must meet them, and I know that I shall.” He would not admit at such moments that his intense longing for the society of his lost friends was no proof of the validity of his hope, nor that future generations, nourished in the Thanatist creed, would accept eternal separation with none of the pangs he suffered. “They will lose more than they will gain,” was his reply to such attempts at consolation. “It is only the certainty of an immortality to be shared with the souls we love that can give such a wretched business as life the smallest value. If this existence is all, it is not worth a burned-out match.” “In that, and all things, will we show our duty.” That was the only reference, either to himself or his work, made in the entire article. These facts have been stated a score of times before, and will probably need to be stated as often again. “I’ve often, vexed by shrill annoys, It would have been very much better to have left such a task to other hands. Such small fry are as dangerous as hornets if provoked, and may be as useful as bees if fed and flattered, or even if left alone. It is not the gros bonnets of the Press, the stately three-deckers of literature and criticism, which it is principally the astute man’s business to conciliate. It is the journalistic cock-boat which swarms on the waters of the Press which does the real execution. As many a beautiful and fertile island owes its existence to the incessant efforts of millions of scarce-perceptible insects, so many a great reputation has been steadily and solidly built by the animalculæ of journalism. Years before a certain enormously popular novelist had attained to his present pride of place I prophesied his triumph, from the simple circumstance that whenever business took me to his place of residence I found him surrounded by a crowd of journalistic wirepullers, individually of small account, but with strength enough in their mass to create any number of literary reputations. Some day, no doubt, these scribbling condottieri will find their general. A man clever enough to form such a mob into a disciplined and obedient regiment could become a veritable artistic kingmaker, and might die worth any amount of money. Balzac’s immortal “Treize” would not be “a circumstance” compared with such a federation. Quite seriously, I see no impossibility in the suggestion, and recommend it to the attention of any reader who believes himself to possess a turn for business organisation. Buchanan never could be persuaded either to conciliate such people or to let them alone. The truth is, he loved a fight, and if there happened to be no single opponent in the field worthy of his steel he was not above charging and slashing among the horde of penny-a-liners. He seemed to say, with old Ruy de Silva in “Hernani”— “Êtes-vous noble? Enfer! Which was magnificent, but not war as wise men make it. The period of my more intimate acquaintance with Buchanan came about in a fashion characteristic of the somewhat “casual” natures of both of us. I had been for some time a frequent visitor at his house and guest at his table when, originally with the purpose of doing with him some piece of work which somehow never got done, I became an inmate under his roof. I went there for a day or two, like Ned Strong to Clavering Park, in “Pendennis,” and stayed there nearly two years. When from time to time I mooted the subject of my departure Buchanan would not hear of it, and I am glad to believe that his constant asseveration that I was of great use to him was more or less really true, though a third person might often have been excused for wondering in what the use consisted. The only joint work bearing our joint names we ever issued were the novelised version of his Haymarket play, The Charlatan, and the comedy, A Society Butterfly, produced at the Opéra Comique, and of which the history shall presently be given. My real utility was as an intellectual strop and chopping-block. Buchanan was in certain respects, and apart from his warm domestic affections, a lonely man. He had never been, nor cared to be, popular with the bulk of men of anything like his own intellectual rank. I have seen but few people under his roof whose names were known outside the circle of their personal acquaintance. Herbert Spencer, of whom I have already spoken, I saw there only once. Hall Caine, then a young man just beginning to rise above the literary horizon, came occasionally. That old-time actor, the late John Coleman, who in his ingrained staginess of voice and manner suggested Mr. Crummles, and in his lightning alternations between the depths of despair and the summits of irrational optimism recalled Mr. Micawber, was a more frequent figure. During his term of collaboration on Adelphi melodrama with Mr. George R. Sims he naturally saw a good deal of that genial jester, who could keep him in roars of laughter for hours at a time. The good things Sims said at Buchanan’s supper-table were infinite in number, and among the best was one at my expense. I had been holding forth with most convincing eloquence regarding the condition of English fiction, and proclaiming the absolute necessity, if the art was not to sink wholly beneath contempt, of a fuller and more fearless treatment of sexual problems, when Sims shot my rhetoric dead by interjecting the heartless remark—“Murray’s Guide to the in-Continent.” “Who, ’spite the bitter fight for bread, Mr. Israel Zangwill shed a welcome ray of light on Buchanan’s personality when he wrote: “The mistake people make about Buchanan is that they think that there is only one of him. There are at least a score of Buchanans, and most of them have not even a nodding acquaintance with the others.” As a pendant to that brilliant bit of analysis let me recount an incident from my recollections of Buchanan’s Turf career. It was at a time when he was amassing material for a study of the life of Christ. I found him standing in the middle of Tattersall’s ring, absorbed in the study of his Greek Testament, perfectly oblivious of the life about him until, at the warning clangour of the saddling-bell, he restored the volume to his pocket, marking his place with a tip-telegram, and plunged amid the roaring “pencillers,” as eager for the fray as any one among them. It was at once one of the quaintest oddities of my experience and a wonderful touch of unconscious self-portraiture. Augustus Harris was altogether too remarkable a personality to be passed over with a casual mention. My connection with him was never really intimate, but we were friendly acquaintances, and something more than that, for several years. Such intimacy as we had together began a little unpropitiously. The World, his first production at Drury Lane, and one which has never been surpassed in the peculiar features of the class of melodrama with which he was associated, was in the early nights of its hugely successful run when I turned up at the theatre one evening accompanied by a friend. I have learned since that it is not considerate to ask for “paper” for a declared success, but I was in the first flush of my short-lived happiness and importance as a critic of a London daily, and had a sort of unformulated conviction—which some critics seem to retain their whole lives long—that it should be the joy and pride of any manager to give me anything in that way I cared to ask for. Harris was standing beside the box-office, and I made my appeal to him personally for a couple of stalls. He set his thumbs in the armholes of his dress waistcoat—a favourite gesture—and replied, “My dear Henry Murray, would you like to put your hand in my pocket and take out a guinea?” Somewhat nettled, I replied to the effect that I had known the time, and that not so long ago, when the feat would have been impossible, and was turning away when he drew me back with a laugh, and gave me the vouchers with so charming a good temper that I repented me of my ill-natured retort. We got on together excellently afterwards, and he showed the kindness with which he regarded me on more than one occasion, and in his own peculiar fashion. I was sitting one night in the rotunda at Drury Lane, plunged in a brown study, when I became aware of somebody regarding me. Looking up I recognised Harris. “What are you looking so rotten miserable about?” was his greeting. I replied that I had not known that I did so look. “What’s the trouble?” he continued; and went on without waiting for an answer, “There’s only one trouble in the world that matters—money. Would twenty pounds do you any good?” “Do you know anybody it wouldn’t do good to?” I asked in return, perhaps a little crustily, for I thought of course that he was merely chaffing me. “A civil question deserves a civil answer,” said Harris, and repeated his query. I naturally replied, “Yes.” “Then come along and you shall have it,” he said, and in the calmest fashion led the way to his office, where he made out and handed to me a cheque for the amount mentioned. I never knew, and never shall know, his motive, if it was not sheer kindness of heart rather eccentrically exhibited. On another occasion I called on him on some matter of business at his house in St. John’s Wood. At the end of our interview, he said, “This is my birthday. What have you brought me?” I replied that being ignorant of the occasion I had nothing to offer but the customary good wishes. “That won’t do,” he said. “This is my birthday, and gifts must pass; so, if you won’t give me anything, I’ll give you something.” He presented me with a box of a hundred excellent cigars and a pretty little silver cigarette-case, the latter of which was filched from my pocket in the street less than a week after. To return to A Society Butterfly. Buchanan was, in sporting parlance, “going for the gloves,” and was determined to give adverse fortune no chances. Few pieces produced by a scratch management have been better cast. Beside Mrs. Langtry, our company comprised that admirable actor, the late William Herbert; Miss Rose Leclerq, the Dugazon of her country and generation, quite the best aristocratic old woman I have ever seen on the English boards; Mr. Fred Kerr, who had already won the place he has since retained in the affections of the London public; poor Edward Rose, a quaint comedian, a graceful jester, and a thoroughly good and lovable fellow, whose all-too-early death was at once a loss to the stage and to the drama; and Mr. Allan Beaumont, then an excellent “old man,” and now a Professor of Elocution at the Guildhall. All were happy in their parts, and all worked with right good will, although in that particular the palm must be awarded to Mrs. Langtry, who had not only to acquire the words and the business of the leading part, but also to study a “Butterfly Dance” specially arranged for her by Mr. Willie Ward. It would be an exaggeration of flattery to say that Mrs. Langtry, as we know her, is actually a great actress, but since my experience with her on the stage of the Opéra Comique, I have had a conviction that she has missed the highest distinction in her adopted profession only because she came to its practice too late in life. Had she begun her professional career ten, or even half a dozen years earlier, at a period when her personality was less fixed and more malleable, she might have made a truly great artist. She possesses in a high degree the sentiment of the boards, and she has a gift Providence is not too fond of bestowing upon women of unusual physical beauty—the gift of brains. I cannot acquit the beautiful lady of her share in our disaster, but that makes it only the more imperative that I should give her the meed she fairly earned, and no chorus girl on her promotion could have been more willing, more patient, more eager to give all possible satisfaction to the management than was Mrs. Langtry. And in one particular she acted with a rare generosity, for which both Buchanan and myself were deeply grateful. She insisted on taking from our shoulders the financial burden of dressing her for her part, and the series of Parisian “creations” in which she appeared would certainly have strained our modest resources. And here we made one mistake—a mistake so foolish that it will remain inexplicable to me until I die how we could have made it—we insisted on providing the “butterfly dress” in which she was to perform her dance. That mistake resulted in the ruin of our hopes. The butterfly dress arrived a night or two before the evening we had advertised for production, and at the first sight of it Mrs. Langtry refused, point-blank and absolutely, to appear in it. And here the syndicate came in and clinched our ruin. A postponement of a day or two would have given Mrs. Langtry time to slip across to Paris, to select a dress suited to her own taste, and so to appear in the dance, which was, as I have said, the very hub of our piece. But the syndicate raised a despairing wail about the folly, the madness, of “disappointing the public.” Buchanan and I pointed out to them that their fear was based on what is perhaps the hollowest of all the innumerable silly superstitions which beset—and besot—the managerial mind; that the public was profoundly indifferent whether or not A Society Butterfly was ever played at all; that all that that section of the public which would be present on the first night—whenever that might be—would care about, was whether the piece then presented interested or failed to interest them. But our logic was vain. They held us to the letter of our agreement—we had advertised to open on a certain night, and open we must. Without the dress, the dance was meaningless, and had to go by the board; so in hot haste we set to work to devise a series of “living pictures,” in the last of which Mrs. Langtry was to appear as “Lady Godiva” about to mount for her solitary progress through Coventry. _____

Reminiscences of Buchanan continued or back to Biography

|

|

|

|

|

|

|