ROBERT WILLIAMS BUCHANAN (1841 - 1901)

|

ROBERT WILLIAMS BUCHANAN (1841 - 1901) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

THE FLESHLY SCHOOL CONTROVERSY The ‘Fleshly School’ Libel Action

|

|

|

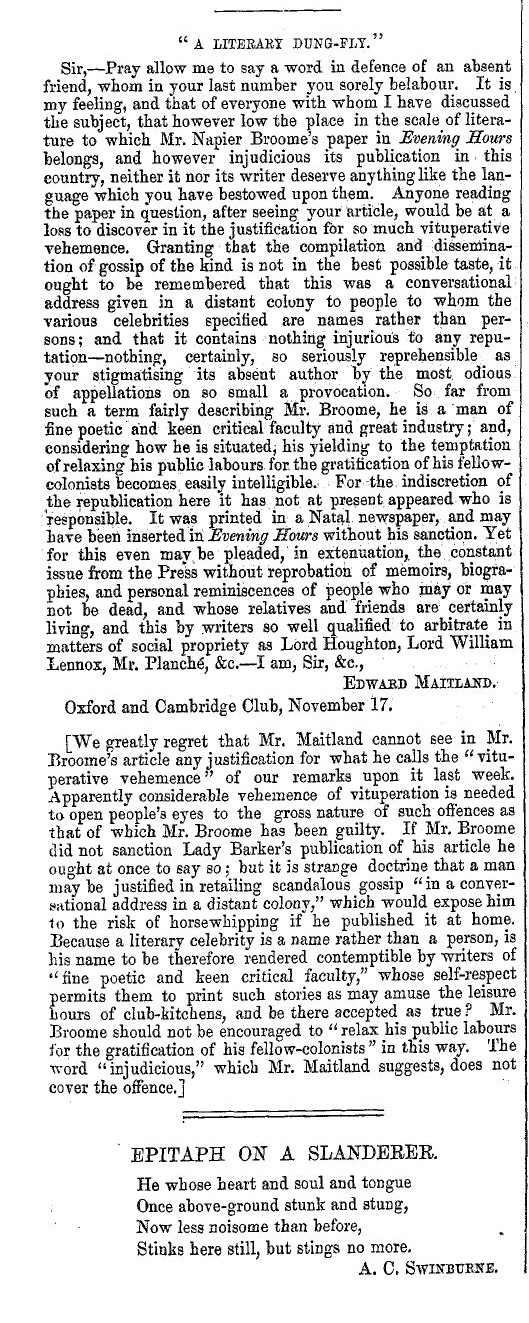

[The coincidence of the name of the correspondent above Swinburne’s ‘poem’ and the heading given to his letter is interesting. The letter was in response to a piece in The Examiner of 13th November, 1875 which had the same heading, and which is available here.] ___

The Aberdeen Journal (24 November, 1875 - p.5) NOTES BY THE WAY. . . . EPITAPH ON A SLANDERER. He whose heart and soul and tongue ___

The Examiner (27 November, 1875) Jonas Fisher. A Poem in Brown and White. London: Trübner and Co. This anonymous poem is said by the “London Correspondents” to be the work either of Mr. Robert Buchanan or of the Devil; and delicate as may be the question raised by this double-sided supposition, the weight of probability inclines to the first of the alternatives. That the author, whichever he is, is a Scotchman, may be inferred from one or two incidental sneers at the characteristic virtues of his countrymen. If a prophet has no honour in his own country, it must be said on the other hand that a country seldom gets much honour from its own prophet; the worst things said about countries have been said by renegade natives. There are other and more specific circumstances which favour the report that Jonas Fisher is another of the aliases under which Mr. Buchanan is fond of challenging criticism, rather than one of the equally numerous disguises of the Enemy. There is no reason why the Devil should go out of his way to abuse “the Fleshly School.” Now the hero of this poem has views on some of the tendencies of modern Poetry and Art which coincide very closely with Mr. Buchanan’s, exhibiting the same nicely balanced and carefully differentiated feelings of scorn for effeminate voluptuousness and delight in that voluptuousness which is manly. Jonas Fisher does not sing for girls, and yet there is not the smallest vice in him. Then Jonas Fisher has a friend who writes a great deal of poetry, very deep and mystical poetry, in dactyls and anapæsts, but who has such a horror of the bloodthirsty critics who lie in wait for him that he refrains from giving his poetry to the world. In this respect he is unlike Mr. Buchanan, but he is very like him in the strong language which he pours out upon A sort of wretch that lives by prey— Still, it may not be Mr. Buchanan after all, for happily he does not stand alone in reiterating the good old literary tradition and firmly-accepted truth among a certain order of poets, that everybody who ventures to suggest that perhaps some of their lines have not been immediately inspired by the divine Muse, must either be a base hireling, well paid for spreading abroad the infamous lie, or at the least a crawling, cringing, crafty fiend and a vampire. But now my days in comfort run, The poem is written partly to describe some of the miseries that he saw among the London poor in the course of his “mission-work,” but more especially to record the conversations he had with “Augustus Grace, Esquire,” a rich philanthropist, who gave Jonas as much money as he liked for benevolent purposes. Their talk has a very wide range. Religious matters in various aspects, the value of dogma, the influence of the Church of Rome, the “natural religion” of good deeds, and so forth, occupy a good deal of their attention, but Mr. Grace is a thinker and a poet as well as a philanthropist, and so he discusses the influence of Body on Spirit, modern Art criticism, Marriage with a Deceased Wife’s Sister, and many other social topics. Jonas very wisely invites his readers, if they like, to treat inverted commas as hints to skip. A large proportion of Mr. Grace’s talk is vulgar and trite enough, but his views are generally put with a certain rough force, and his images, if sometimes unnecessarily coarse, have usually the merit of vigour and vividness. Mr. Grace is the kind of man that might stump the Potteries against Dr. Kenealy with considerable chances of success. His analysis of the various reasons that lead men to Rome would tell with powerful effect from the stump on a demonstrative audience, and his fierce commination of priests for their opposition to the Deceased Wife’s Sister’s Bill would be simply irresistible. We mention this with no intention of disparaging ‘Jonas Fisher,’ whose aims are, on the whole, perfectly healthy if rather coarse, but simply to indicate the quality of the work and the peculiar power of the author. Reader, you might as well expect The clownish disguise is very fairly well sustained. The narrator’s bald language, and rude mixture of sacred and profane images, is sufficiently natural to have the appearance of being unconscious simplicity. His account of his visit to two Irishwomen is in very good keeping:— Notions do differ. Some good folk Attention thus they hope to draw, But I have always liked to act Well, at the opening door I paused, An inner porch I then perceived; “Off with you, dirty Protestant! On hearing this I breathed a prayer— “You’re not a Christian, sure, at all; This kind of wide-mouthed Irish folk, * * * * They really scarce would let me go, The priest, of course, had come meanwhile, But still when people take to hunt This episode will give some idea of the sort of “incidents” that are to be found in ‘Jonas Fisher.’ When the missionary has fully developed his character in his conversations with his patron, Mr. Grace, to whom he acts as a kind of Boswell, holding up a dark background of Evangelical prejudice to set off the Broad Church light of his hero, and when he presents us with a sketch of his outer man, meek and self-distrustful in bearing, clad in glossy black clothes, which in some places stick to him like plaster, and in others hang upon him as on a broomstick, we feel as if we had been introduced to a real personality. There is undoubtedly a remarkable power of dramatic consistency shown in the gradual unfolding of Jonas’s character, with it earnest goodness and narrow prejudices, its spiritual pride occasionally peeping up above the humble flats of its habitual timidity and self-abnegation, its fortress of resentful self-respect behind its wide tracts of meek compliance. The author occasionally forgets himself, and puts words into Jonas’s mouth which belong rather to a third party surveying Jonas from an unsympathetic distance, and making fun of his humility and simplicity; but in spite of occasional lapses, the character on the whole is a complete and consistent picture. “French polish for old British oak! “Well, Sir, why not?” said I. “The man Such little passes give a certain liveliness and reality to the otherwise one-sided dialogues in which Mr. Grace expounds his views on such social subjects as we have mentioned. Those views are not in themselves sufficiently removed from commonplace, either in matter or in form, to call for much remark. His indignant censure of the Church for its action regarding deceased wife’s sister is a fair sample of his gospel, and his manner of preaching it— “Although no Churchman, Sir,” said I, “And therefore I would have her rest “But (to return from whence we came) “To put it plainly, thus I speak— “‘And if, in secret, to devour “‘Forbear, likewise, to gull the land “Oh for a Samson strength to ban “Oh hush,” said I; “that sort of talk In the case of what he calls “Parisian art,” which Mr. Grace, in common with Mr. Robert Buchanan, most fervently hates, his vehemence is less well directed. Mr. Grace mentions no names, but if, as is probable, his reference is to what is sometimes called the Rossetti-Swinburnian school, he ought to be told that it is not becoming in one poet to try to raise a public prejudice against some of his brethren because their productions are as distasteful to him from a moral point of view as they certainly are, judged by artistic standards, above his powers. He probably believes that the objects of his censure have an immoral tendency; and if so, it would be unfair to deprive him merely because he is also a poet of his citizen’s right of protest. But he ought to remember that impartial spectators take a different view, and refuse to admit that there is any immoral motive in the works which are to him so objectionable. If men, who do not come under the spell of their legitimate influence, make food of them for their own prurient imaginations, the same may be said of Mr. Buchanan’s and Mr. Grace’s “manly voluptuousness,” and said, too, with more truth. By what hallucination Mr. Grace is brought to believe that the moral law that forbids Mr. Rossetti or Mr. Swinburne to carry out their ideals of art, permits him to draw such pictures as the following ideal of “a pretty woman,” it is impossible to conceive:— “A pretty woman,” answered he, “But nobleness-in-beauty—nay! “Of fantasies with which the fiend “No weasel slim to slip through holes “Such was each queenly Teuton wife, Any attractive picture of any object of desire, from a bright new sovereign or a prize ox upwards, would be condemned by moralists of Mr. Grace’s school, and if his practice were judged by his own precepts, he himself would be one of the first to be made an example of. There is no reasonable halting-place between those precepts and Plato’s absolute banishment of the poets. ___

The Examiner (4 December, 1875) Mr. Robert Buchanan has asked us to contradict the rumour that he is the author of ‘Jonas Fisher.’ He had not heard of the work till he saw our review. ___

The Athenæum (4 December, 1875 - p.751) MR. ROBERT BUCHANAN writes to us:— ___

The Examiner (11 December, 1875) In reviewing two weeks ago a poem called “Jonas Fisher,” we took occasion to discuss a “London Correspondent’s” rumour that the poem was the work “either of Mr. Robert Buchanan or the Devil.” The expression was not ours, but the “London Correspondent’s;” and last week, having no quarrel with Mr. Buchanan or desire to say anything ill-natured about him, we acceded to a request which he made, in most friendly terms, that we should “contradict the foolish rumour.” It was with some surprise therefore that we saw in a paragraph in one of our contemporaries the Examiner quoted as the authority for the strange alternative supposition of the “London Correspondent” (who might have been Mr. Buchanan himself for all that we knew); and our surprise was not lessened when we found that the author of the paragraph in our contemporary was Mr. Buchanan himself! Why Mr. Buchanan should quote us as an authority for a rumour which he knew to come from a different source is known only to himself. May we suggest to him that his talents, which are considerable, would meet with more respect if he would not take to such questionable ways of keeping his name before the public? ___

The Examiner (11 December, 1875) CORRESPONDENCE. THE DEVIL’S DUE. Sir,—It is with inexpressible interest that I receive, at this distance from New Grub Street, the important and doubtless trustworthy—I should say reliable—information that the Examiner has lately discovered a mare’s-nest, and that a poem which I certainly did not understand to be on your authority, but on quite another kind of authority than yours, attributable “either to Mr. Robert Buchanan or the Devil,” is at all events not assignable to my illustrious namesake in pseudonymy. So much the better, or so much the worse, as the case may be, either for the songster or the song—possibly for both at once. The invention of the mare’s-nest (I do not use the word “invention” in that sense in which the Church Universal talks, or used to talk, of the Invention of the Cross) is doubtless all in “the Way of the World”—the title and the subject of the greatest of English comedies. But I may perhaps take this occasion to remark that the mere suggestion of such an alternative in authorship as appears elsewhere to have been offered with less discretion than decision would be more perplexing to readers of ‘Paradise Lost’ than to readers of the Book of Job (I do not say the ‘Book of Robert Buchanan’) or of Peter Bell the Third. The devil of Scripture, as we all know, was addicted to “going to and fro in the earth, and walking up and down in it;” a locomotive habit which may suggest the existence on his part of at least one quality in common with the bard whose range of vision and visitation is supposed to oscillate between the Seven Dials and the Land of Lorne:— Whom green-faced Envy, sick and sore, And if this seer, this Vates, this teacher of a new truth—who “is one while what you call artists are legion” —might, on this one account, be mistaken for the tempter of Job, it is possible that on another score he might be confounded with the spirit whose portrait is thus drawn by Shelley:— The Devil was no uncommon creature; But it is certainly inconceivable that the authorship of any work whatever should be assignable with equal plausibility to the polypseudonymous lyrist and libeller in question and to the Satan of Milton, the Lucifer of Byron, or the Mephistopheles of Goethe. The work of which the credit was but now disputed on behalf of two such claimants is known to me as yet only by the extracts given in your columns; but from these I gather that the title of Mr. Robert Buchanan (seu quocunque alio nomine gaudeat) must have been disputable, apart from his own disclaimer, on at least two counts. An author haunted by “such a horror of the bloodthirsty critics who lie in wait for him” has evidently yet to learn the new and precious receipt discovered by Mr. Robert Buchanan (if that be his name), of “Every Poeticule his own Criticaster;” a device by which Bavius may at once review his own poems with enthusiasm under the signature of Mævius, and throw dirt up in passing with momentary security at the window of Horace or of Virgil. I notice also that the present writer has adopted as the object of his servile but ambitious imitation an inimitable contemporary model of original burlesque, on which I am not aware that the “multifaced” idyllist of the gutter has yet attempted to form himself. The apposition of two representative stanzas will suffice to establish at once the fact and the extent of this discipleship. You quote from “Jonas Fisher” the following notable quatrain:— “Oh, hush,” said I, “that kind of talk As an evidence of careful study this quatrain is creditable to the docile and obsequious pupil. But hear now the unmistakeable accents of his master:— Said Captain Bagg, “Well, really, I In the golden roll of the “Bab Ballads,” and perhaps in the very poem from which this particular stanza is taken at random, there may be stanzas of which the palpable imitation here attempted by the godson of Mr. Jonas Chuzzlewit is even closer and more flagrant; but, judging from what I see of his verse, the last line appears to me to realise with singularly felicitous exactitude the very words which might be expected to rise to the lips of a reader overcome with such emotion as would naturally seek the instant relief of apt expression, and could certainly find none fitter than the eloquent if ejaculatory remonstrance of the gallant Captain with his friend. A more impatient reader of the poem might probably be tempted, with Mrs. Gamp, to “wish it was [back] in Jonadge’s belly;” I will content myself with recommending the author—unless, as is indeed probable, he be also a disciple of the Bavio-Mævian theory (so excellently exemplified by the Mævio-Bavian practice) that Verse is an inferior form of speech—to study in future the metre as well as the style and reasoning of the “Bab Ballads.” Intellectually and morally he would seem to have little left to learn from them; indeed, a careless reader might easily imagine any one of the passages quoted to be a cancelled fragment from the rough copy of a discourse delivered by “Sir Macklin” or “the Reverend Micah Sowls;” but he has certainly nothing of the simple and perfect modulation which gives a last light consummate touch to the grotesque excellence of verses which might wake the dead with “helpless laughter.” P.S.—On second thoughts, it strikes me that it might be as well to modify this last paragraph and alter the name of the place affixed; adding at the end, if you please—not that I would appear to dictate—a note to the following effect:— The writer of the above being at present away from London, on a cruise among the Philippine Islands, in his steam yacht (the Skulk, Captain Shuffleton master), is, as can be proved on the oath or the solemn word of honour of the editor, publisher, and proprietor, responsible neither for an article which might with equal foundation be attributed to Cardinal Manning, or to Mr. Gladstone, or any other writer in the Contemporary Review, as to its actual author; nor for the adoption of a signature under which his friends in general, acting not only without his knowledge, but against his expressed wishes on the subject, have thought it best and wisest to shelter his personal responsibility from any chance of attack. This frank, manly, and consistent explanation will, I cannot possibly doubt, make everything straight and safe on all hands.

[Return to Extracts from the Letters of Swinburne, W. M. & D. G. Rossetti Relating to Buchanan) ___

The Echo (11 December, 1875 - p.4) ART AND LITERARY GOSSIP. Mr. Charles Reade denies that he is the author of The Queen of Connaught, and it is understood that the writer is a lady. . . . The editor of the Examiner desires us to state with reference to the remark that the poem “Jonas Fisher” was “written either by Mr. Buchanan or the Devil,” that the phrase did not originate with that journal, which merely discussed a previous rumour to that effect. ___

The Aberdeen Journal (15 December, 1875) NOTES ON LITERATURE, SCIENCE, AND ART. THE Examiner exposes a very pretty little game of Mr Robert Buchanan’s. It seems Mr Buchanan has been putting paragraphs into the papers, saying that “Jonas Fisher” is either by Robert Buchanan or the Devil, and then writing letters to say that it is not by Robert Buchanan! ___

Glasgow Herald (27 December, 1875) LITERATURE. (1) Jonas Fisher. The authorship of this poem has provoked a deal of speculation. Some think it is written by an Englishman, others that it is by a Scotchman. Two or three have a notion that it is the work of a layman, and a number imagine that a Scotch clergyman is the culprit. Whoever is the author, it seems to us that he has more ability than the poem reveals; that generally he writes down to the capacity of Jonas Fisher, the city missionary; and that this is proved by the quality of those passages in which Mr Grace, the strongest and in reality the most important character in the book, discusses the system of the Romish Church and a variety of much tougher themes. There are two clergymen in Scotland who could have written the book, and particularly the more piercing portions. But we shouldn’t be astonished to learn that “Jonas Fisher” is really the work of a woman—such a woman as wrote “Joshua Davidson,” of which peculiar but clever tale something in the poem is for ever reminding the reader. Mr Robert Buchanan, who has more than once cheated his enemies into admiration by shooting through a cloud of anonymity, declares that the book isn’t his, or, at least, that the statement to that effect is unauthorised. It is a marvel that no gossip-monger has accused George Macdonald of being the author. Remembering “David Elginbrod” and several strong characters in his other novels—characters which have a singular knack of speaking out—“Jonas Fisher” is not unlike a thing that he might write in the pauses of severer work. Indeed, the touches of his hand, or of one similar to it, are quite visible in some of its strangely graphic pictures, and in its more delicate and subtle touches. George Eliot might also be suspected of writing such a poem. In point of character, it is a kind of versified autobiography of Jonas Fisher, who tells the story—such story as there really is to tell. It were more accurate to say that the main purpose of the book is to put in striking light the opinions and sayings of Mr Grace. ... [The rest of this review (with no further speculation on the authorship of the poem) and the review from The Academy are available on the ‘Fleshly School’ Libel Action - additional material page.] ___

The Oshkosh Daily Northwestern (31 December, 1875) A short time ago, a poem was published in London entitled, “Jonas Fisher: a Poem on Brown and White,” which the Examiner, in a review, declared must have been written “either by Mr. Robert Buchanan or the devil.” It is now authoritatively stated that it was not written by Mr. Buchanan. ___

The London Quarterly Review (January, 1876) Jonas Fisher. A Poem in Brown and White. London: Trübner and Co., 57 & 59, Ludgate Hill. 1875. THE author of Jonas Fisher, “a Poem in Brown and White,” has not been good enough to set his autograph upon his work, and has thus afforded Mr. Robert Buchanan a favourable opportunity (not altogether lost) of getting up another fuss about himself. We cannot say we suspect Mr. Tennyson or Mr. Browning, or indeed anyone who has won ever such a small pair of spurs in the fields of verse, of the authorship of this anonymous volume,—which, by the bye, though very much too polemical for poetry, is not without merit. Of poetic merit properly so called it has but little; and the religious and social questions discussed in it in jumpy lengths of rhymed prose, might have been discussed better in plain, unrhymed prose. There is a wise attractiveness to the reader’s curiosity in the opening verses— “This story is not meant for girls, “The superfine of either sex, And we can endorse the assurance of the author that, if the young people of the present generation are tempted to read the book, it will not do them any particular harm. On the other hand, we are by no means convinced that it will do anyone any particular good, though written with obvious good intentions enough to furnish forth a dozen books with moral and religious purpose. It is a fairly interesting book of verse, and one not to be lightly taken up or put down; but we think it would have secured more readers had it been got into about half the number of stanzas contained in its two hundred and fifty pages. Jonas Fisher may have the luck to create something of a stir; but, even if it does, it will soon blow over. ___

The Leeds Mercury (20 January, 1876) SPECIAL CORRESPONDENCE. (BY PRIVATE TELEGRAPH.) LONDON, Wednesday Night. . . . I hear that Mr. R. Buchanan, who is described by the advertisements of the Gentleman’s Magazine as “the poet,” has brought an action for damages against the Examiner, in respect of a letter published therein, signed “Thomas Maitland,” which recently made fun of Mr. Buchanan’s modest estimate of his own merit, and of the somewhat curious style of prose which he writes. This article, if I am not mistaken, was written by one of the gentlemen whom Mr. Buchanan, under the signature of “Thomas Maitland,” ventured to arraign a year or two ago, and who could well have afforded to disregard all such anonymous attacks. Mr. Buchanan, I believe, in his statement of claim, rather takes the air of a public benefactor who has done his best to check the immorality of modern poetry, and who has been, in consequence, subjected to revengeful onslaughts. I have not seen this statement of claim, but it is sure to be pervaded by Mr. Buchanan’s altogether excessive modesty. ___

The Dundee Courier and Argus (22 January, 1876 - p.3) Mr Robert Buchanan has raised a libel action against the Examiner on account of a letter signed “Thomas Maitland” which recently appeared in that journal, and was meant as a reply to Mr Buchanan’s New Timon-like criticisms of a year or so ago. ___

Liverpool Mercury (27 January, 1876) Lord Southesk is now declared to be the author of that remarkable poem “Jonas Fisher,” which the Spectator said must have been written either by Mr. Robert Buchanan or the Devil. Lord Southesk is a Liberal peer, who has begun a literary career somewhat late in life. He is 48 years old, and I believe that until his recent book about sporting in America he had not appeared before the public. He is an old guardsman, succeeded his father, Sir James Carnegie, in the baronetcy, got the Scotch earldom of Southesk restored in his favour in 1855, and was made a peer of the United Kingdom in 1869. He married a daughter of the first Earl of Gainsborough, and she died in the year that he was raised to the peerage, leaving him with four children, of whom the youngest is his heir, and has lately come of age. ___

The Glasgow Herald (27 January, 1876 - p.5) The recent letter, under the signature of “Thos. Maitland,” which, in the Examiner, provoked the ire of Mr Robert Buchanan, is said to be the work of Mr Swinburne, who surely has as much right as any one to fall foul of Mr Buchanan, seeing how terribly mauled he was himself by Mr Buchanan’s hands. ___

The Manchester Courier and Lancashire General Advertiser (1 February, 1876 - p.5) The action for libel in which Mr. Robert Buchanan, the poet, threatens the London Examiner, has its amusing side. Mr. Buchanan deems himself unfairly attacked by a critic signing himself “Thomas Maitland.” This was the nom de plume used by Mr. Buchanan at one time, the signature under which he assailed the Fleshley School so vigorously, and he is naturally wrath that a foe should assume the same name. Mr. Swinburne was supposed to be the second Thomas Maitland, but those who know his scorn of the first and his dislike of anonymity ridicule the suspicion. ___

Trewman’s Exeter Flying Post or Plymouth and Cornish Advertiser (2 February, 1876) The recently published poem of Jonas Fisher, a poem which the Editor of the Examiner said must either be Robert Buchanan’s or the Devil’s, turns out to have been written by Lord Southesk, so that if the Editor of the Examiner may be taken to be an authority in matters of this kind, the question of the Personality of the Devil is settled. His Majesty is, when in the flesh, a middle aged English Peer, who began life in the Guards, and has now taken to poetry. ___

The Exeter and Plymouth Gazette (4 February, 1876 - p.8) I am told that a quarrel between two men of genius is waging which will not improbably find its way for settlement into the Law Courts, and if it does, some very lively reading is likely to be the result. The combatants are no less persons than Algernon Charles Swinburne and Robert Buchanan, the poets. Mr. Buchanan has written some rather sharp things of Mr. Swinburne, and in return the latter has pretty well roasted the former at various times, especially of late in the Examiner. The original cause of complaint was a statement in the Examiner, that the anonymous poem called Jonas Fisher was by “Robert Buchanan or the devil.” Mr Buchanan naturally did not like the analogy, and in disclaiming the authorship of the poem showed a good deal of temper, which was reciprocated by Mr. Swinburne, who wrote, it is stated, a letter in the Examiner above the signature of “Robert Maitland,” in which appear the specific statements complained of. Buchanan calls this a malicious slander, and claims, jointly from the Examiner and Swinburne, damages amounting to £5,000. ___

The Isle of Man Times (5 February, 1876 - p.2) There is to be another great literary libel case. Robert Buchanan, the poet, calls upon the Examiner to answer for a malicious slander upon him, and puts the damages at £5,000. The quarrel arose in the first place out of the statement made by the Examiner that the anonymous poem called “Jonas Fisher” was by “Robert Buchanan or the devil.” Buchanan declared that it was not his, and a little temper was shown on the subject on the one side and the other, and presently in the same paper appeared a severe attack upon Buchanan signed “Robert Maitland.” In this letter Mr Buchanan finds his libel, and the letter turns out to have been written by the poet Swinburne, against whom Buchanan has written many severe things from time to time. Buichanan’s friends are urging him to let the matter rest; but, on the other hand, it is urged that the letter in question contains language which could not be justified under the privileges of criticism. ___

The Aberdeen Journal (9 February, 1876) Mr Buchanan has raised an action against the Examiner for the modest sum of £5000. ___

The Leeds Mercury (9 February, 1876) I am afraid that, after all, the public may be deprived of its anticipated laugh over the “Thomas Maitland business.” Certain interrogatories have, according to the new procedure, been submitted by the defendant’s counsel, and it is just possible that when Mr. R. Buchanan comes to consider these he will, on reflection, consent to a withdrawal of the case. The comic papers, including the Saturday and the World, would regret this. ___

The Times (16 February, 1876 - p.11) BUCHANAN V. TAYLOR. This was a motion to rescind an order of Mr. Justice Denman at Chambers, allowing certain interrogatories to be administered by the defendant. ___ [Note: ___

The Morning Post (16 February, 1876 - p.7) BUCHANAN V. TAYLOR. The plaintiff in this case was Mr. Robert Buchanan, and the action was one of libel, brought against Mr. Peter Taylor, the proprietor of the Examiner. The matter came before the court upon an application to rescind part of an order of Mr. Justice Denman allowing a certain interrogatory to be exhibited by the defendant to the plaintiff. It was stated that the plaintiff about three years ago wrote a severe article in the Contemporary Review which gave great offence to Mr. Swinburne, Mr. Rosetti, and Mr. Morris, and to this article he did not append his own name. The editor, to prevent the article appearing anonymously, put to it the name of “Thomas Maitland.” The plaintiff, however, was found out to be the author, and he was severely attacked in the Athenæum and other journals. It was some of these attacks that led to the present action. It was alleged against the plaintiff that he had anonymously published unfair criticisms of certain writers, and that he had unfairly praised the poems and other writings of himself. The interrogatory asked him whether he had not written under a pseudonym or anonymously of Mr. Swinburne, Mr. Rosetti, Mr. Morris, “and other so-called writers of the fleshly school;” and also whether he had not written anonymously in reference to his own poems and other writings. ___

The Edinburgh Evening News (17 February, 1876- p.2) THE “FLESHLY SCHOOL” OF POETRY. The action which Mr Robert Buchanan, the poet, has raised against the Examiner is likely to prove more than usually interesting. I understand, writes the London correspondent of the Dundee Advertiser, that about a dozen leading literary men will figure in the proceedings, and that Mr Swinburne, Mr Morris, and Mr Rossetti will be put into the witness-box to be asked questions which, if answered, may throw some strange light on the art of literary criticism. Mr Buchanan himself will be put in the box, and, if all one hears be true, his examination will be quite an event. Readers of periodical literature have not forgotten the tumult created by Mr Buchanan’s attack on the “Fleshly School” of poetry. The tumult will be re-created in an altered form. Mr Buchanan, I believe, alleges that the Examiner has been the instrument of the “Fleshly” litterateurs, who have through its columns systematically attacked him because he put them down. He seems to suspect a conspiracy whose existence will, I hear, be easily disproved. The immediate cause of the fight is, singularly enough, Lord Southesk’s poem “Jonas Fisher.” The Examiner, quoting from the poem, attributed the authorship of “Jonas” to Mr Buchanan, which sad assertion was followed by a letter by Mr Swinburne, who, under a signature which Mr Buchanan could not like, said some things which Mr Buchanan could not endure. ___

The Manchester Courier and Lancashire General Advertiser (6 March, 1876 - p.5) Mr. Robert Buchanan, the poet, has just arrived in London from Connemara, Ireland, in order to prosecute his case against Mr. Taylor, M.P., and the proprietor of the Examiner, for alleged libels in that publication. The trial will come on in a few weeks, and will doubtless be the talk of the town. There will also be much food for merriment, for Mr. Swinburne, the most nervous of bards, will have to appear in the witness-box. Mr. George Barnett Smith, the editor of the Evening Echo is also one of those subpœnaed, as is also the Earl of Southesk. The noble earl, we have reason to believe, strongly sides with the complainant—the now avowed author of “Jonas Fisher”—as he is very much dissatisfied that it should have been attributed either to “Mr. Buchanan or the Devil.” A Q.C. has been retained as counsel on either side. ___

The Brisbane Courier (14 April, 1876 - p.3) Piccadilly Points of View. LONDON, February 3. . . . We are to have another libel case which will excite, if not the general interest which was attracted by Mr. Irving’s action against Fun—the details of which were exceedingly amusing, and especially the examination of Mr. Toole in Court—at least considerable attention on the part of the literary world. Mr. Robert Buchanan, who is a poet of some merit, and writes very creditable—if occasionally extravagant—essays, is unhappily a very vain and super-sensitive person. He is incensed by silence, and he is outraged by any comment which can be called criticism. “Praise everything, and quote the whole,” was Sidney Smith’s advice to a person who asked him how he ought to review a friend’s book. Mr. Robert Buchanan is seemingly of this way of thinking, but he has, if any writer can have an excuse for doing so undignified an act as criticising his critics, some reason for being angry with The Examiner. He has certainly been severely handled in its columns, but that is not saying that the criticisms are unjust, or their authors actuated by any reprehensible motive. However, Mr. Robert Buchanan believes himself to be the object of personal malice on the part of The Examiner, and is about to bring an action against that journal, claiming damages to the extent of £5000. He alleges that The Examiner’s criticisms of his work are notoriously and systematically prejudiced, and that a conspiracy to write him down has been formed in The Examiner office. It is rather amusing when one recollects that quite lately The Examiner published a paragraph in which the authorship of a poem called “Jonas Fisher,” which has been much talked of, was attributed to Mr. Robert Buchanan; followed it up with a letter from the irascible bard himself disclaiming the authorship of “Jonas Fisher,” and then came out with a statement that both the paragraph and the letter emanated from the same source—Mr. Buchanan himself. A special feature in the case—should it ever come into Court—will be the letters published in The Examiner under the signature “John Maitland,” the nom de plume which Mr. Buchanan adopted when he attacked the Swinburne and Rossetti clique in an essay upon “The Fleshly School of Poetry.” Mr. Swinburne is known to be the author of these letters, and he is naturally not fond of Mr. Buchanan, so that should the battle come to be fought in the open, it will no doubt prove to be a very pretty quarrel. ___

The Sheffield Daily Telegraph (28 June, 1876 - p.3) An interesting action for libel is down for to-morrow though no one can say when it may actually come on. The plaintiff is Mr. Robert Buchanan, the poet, and the defendant the printer of the Examiner. The case arises out of a letter published some months ago in the Examiner, in which Mr. Buchanan was rather cruelly chaffed. The added sting was given to the letter by the signature “Thomas Maitland,” that being the signature of the former article in the “Contemporary Review,” in which “The Fleshly school of poetry” was described, and Robert Buchanan was warmly eulogised. The wicked world has always had it that Buchanan himself wrote that article, and, indeed, I do not know that the soft impeachment has ever been seriously denied. It is scarcely less a secret that Swinburne wrote the letter in the Examiner which is the subject of the action. That distinguished poet will appear in the witness box, and his evidence is looked forward to with great interest. _____

The Trial

The Pall Mall Gazette (29 June, 1876) ACTION FOR LIBEL AGAINST A NEWSPAPER. In the Common Pleas Division of the High Court to-day Mr. Justice Archibald, with a special jury, is trying the case of Buchanan v. Taylor. This was an action by Mr. Robert Buchanan against the proprietor of the Examiner newspaper, Mr. P. A. Taylor, M.P. for Leicester, to recover damages for an alleged libel contained in notices of a poem which was supposed to have been written by the plaintiff, called “Jonas Fisher.” The defendant, in addition to “Not guilty,” justified the supposed libel as being only a fair criticism of the work. This anonymous poem is said by the London correspondents to be the work of either Mr. Robert Buchanan or the devil; and delicate as may be the question raised by this double-sided supposition, the weight of probability inclines to the first of the alternatives. That the author, whichever he is, is a Scotchman, may be inferred from one or two incidental sneers at the characteristic virtues of his countrymen. If a prophet has no honour in his own country, it must be said, on the other hand, that a country seldom gets much honour from its own prophet. The worst thing said about countries have been said by renegade natives. There are other and more specific circumstances which favour the report that Jonas Fisher is another of the aliases under which Mr. Buchanan is fond of challenging criticism, rather than one of the equally numerous disguises of the enemy. There is no reason why the devil should go out of his way to abuse the “Fleshly School.” Now the hero of this poem has views on some of the tendencies of modern poetry and art which coincide very closely with Mr. Buchanan’s, exhibiting the same nicely balanced and carefully differentiated feelings of scorn for effeminate voluptuousness and delight in that voluptuousness which is manly. This criticism, it was submitted by the learned counsel, was unfair and unjust to the plaintiff. This, however, was not all, for in the Examiner of the 11th of December last there appeared a letter headed “The Devil’s Due,” and signed with the name which had been placed to the plaintiff’s article in the Contemporary Review, “Thomas Maitland,” and dated from “St. Kilda.” The writer says:— It is with inexpressible interest that I receive, at this distance from New Grub-street, the important and doubtless trustworthy—I should say, reliable—information that the Examiner has lately discovered a mare’s nest, and that a poem which I certainly did not understand to be on your authority, but on quite another kind of authority than yours, attributable “either to Mr. Robert Buchanan or the Devil,” is at all events not assignable to my illustrious namesake in pseudonymy. So much the better, or so much the worse, as the case may be, either for the songster or the song, possibly for both at once. The invention of the mare’s nest (I do not use the word “invention” in that sense in which the Church Universal talks, or used to talk, of the invention of the Cross) is doubtless all in the “way of the world”—the title and the subject of the greatest of English comedies; but I may perhaps take this occasion to remark that the mere suggestion of such an alternative in authorship as appears elsewhere to have been offered with less discretion than decision, would be more perplexing to readers of “Paradise Lost” than to readers of the Book of Job. (I do not say the book of Robert Buchanan or of Peter Bell the third). The devil in Scripture, as we all know, was addicted to going to and fro on the earth, and walking up and down in it, a locomotive habit which may suggest the assistance on his part of at least one quality in common with the bard whose range of vision and visitation is suggested to oscillate between the Seven Dials and “the Land of Lorne. The article continued at considerable length in a similar strain. Mr. Buchanan sent a paragraph to the Echo simply stating that he had nothing to do with “Jonas Fisher;” and there also appeared a paragraph in the World in which some allusion was made to the Examiner; but with this the plaintiff had nothing whatever to do, though it was attributed to him in the Examiner. The plaintiff, through his solicitors, entered into a correspondence, in the course of which it was stated that “The Devil’s Due” was written by Mr. Swinburne, who, it was said, was prepared to take the full responsibility of the article, and it was suggested that proceedings should be taken against him, and not against Mr. Taylor, but this was declined, and the action went on. The learned counsel, in conclusion, said that in the course of what had been written in the Examiner of the plaintiff he was called “a skulk,” “a shuffler,” “a liar,” and “the idyllist of the gutter,” which surely could not be called fair criticism. Mr. Taylor might know nothing of the article, but he was responsible for it, for he gave an opportunity to Mr. Swinburne not to adversely criticise Mr. Buchanan’s works, but to vent the spleen, spite, and malice which he had conceived, so far back as 1871, against the article by “Thomas Maitland” upon the “Fleshly School,” and during all which time Mr. Swinburne appeared to have nursed his wrath. ___

The Times (Friday, 30 June, 1876 - p.11) SECOND DIVISIONAL COURT. This is an action by Mr. Robert Buchanan against Mr. Peter Taylor, M.P., for libels published in the Examiner, of which publication the defendant is the proprietor. The defendant pleaded that the articles complained of were written and published for the public good and in fair and bona fide comment on the critical writings of the plaintiff. ___

The Guardian (30 June, 1876 - p.8) EXTRAORDINARY ACTION FOR LIBEL. In the Common Pleas Division, yesterday, Mr. Justice Archibald, with a special jury, was engaged in trying the case of Buchanan v. Taylor. This was an action by Mr. Robert Buchanan against the proprietor of the Examiner newspaper, Mr. P. A. Taylor, M.P. for Leicester, to recover damages for an alleged libel contained in notices of a poem which was supposed to have been written by the plaintiff, called “Jonas Fisher.” The defendant, in addition to a plea of not guilty, justified the supposed libel as being only a fair criticism of the work.—Mr. Charles Russell, Q.C. and Mr. McClymont appeared for the plaintiff; and Mr. Hawkins, Q.C. Mr. Mathew, Mr. Warr, and Mr. Robert Williams for the defendant.—Mr. C. Russell, in opening the case, said that the plaintiff was a Scotchman by birth and a literary man by profession. He had attained a considerable amount of eminence in his profession, and he received by the hands of Mr. Gladstone some years ago an award from the Royal Literary Fund, which was the more creditable as having been entirely unasked for. The defendant’s paper was one which, to say the least of it, took strong and peculiar views of politics and religion. Some years ago there sprung up what was known as the “Fleshly School” of writers; and among the most prominent of the writers of this school were Mr. Swinburne, Mr. Rossetti, Mr. Maurice, and Mr. O’Shaughnessy. This school was disgraced by an amount of sensualism and subtle indecency such as was to be found in the French school of writers, but seldom, happily, among English writers. In 1870 Mr. Buchanan sent to the Contemporary Review an article upon the writers of this school, but wished that article to be judged of simply upon its own merits, and he did not, therefore, wish to append his name to it. It was, however, the custom to place names at the end of articles in that review, and the publisher therefore appended the name of “Thomas Maitland.” In consequence of some observations made upon this article the plaintiff came forward, and openly avowed the authorship. After this Mr. Buchanan was criticised most severely by Mr. Swinburne in a publication called “Under the Microscope,” in which article he was supposed to have used up every epithet of abuse in the English language. After this matters rested for a while, but in 1875 Messrs. Trubner published a poem called “Jonas Fisher,” in which the writer took somewhat the same views as the plaintiff might have taken. Thereupon the poem was attacked in the Examiner. It was said, “This anonymous poem is said by the London correspondents to be the work of either Mr. Robert Buchanan or the devil; and delicate as may be the question raised by this double-sided supposition the weight of probability inclines to the first of the alternatives. That the author, whichever he is, is a Scotchman may be inferred from one or two incidents, sneers at the characteristics of his countrymen. If a prophet has no honour in his own country, it must be said, on the other hand, that a country seldom gets much honour from its own prophet. The worst thing said about countries have been said by renegade natives. There are other and more specific circumstances which favour the report that Jonas Fisher is another of the aliases under which Mr. Buchanan is fond of challenging criticism rather than one of the equally numerous disguises of the enemy. There is no reason why the devil should go out of his way to abuse the ‘Fleshly School.’ Now, the hero of this poem has views on some of the tendencies of modern poetry and art which coincide very closely with Mr. Buchanan’s, exhibiting the same nicely balanced and carefully differentiated feelings of scorn for effeminate voluptuousness and delight in that voluptuousness which is manly.” This criticism, it was submitted by the learned counsel, was unfair and unjust to the plaintiff. This, however, was not all, for in the Examiner of the 11th December last there appeared a letter headed “The Devil’s Due,” and signed with the name which had been placed to the plaintiff’s article in the Contemporary Review, “Thomas Maitland,” and dated from “St. Kilda.” The writer says:—“It is with inexpressible interest that I receive, at this distance from New Grub-street, the important and doubtless trustworthy—I should say, reliable—information that the Examiner has lately discovered a mare’s nest, and that a poem which I certainly did not understand to be on your authority, but on quite another kind of authority than yours, attributable ‘either to Mr. Robert Buchanan or the devil,’ is at all events not assignable to my illustrious namesake in pseudonymy. So much the better or so much the worse, as the case may be, either for the songster or the song, possibly for both at once. The invention of the mare’s nest (I do not use the word ‘invention’ in that sense in which the Church Universal talks, or used to talk, of the invention of the Cross) is doubtless all in the ‘way of the world’ - - the title and the subject of the greatest of English comedies; but I may perhaps take this occasion to remark that the mere suggestion of such an alternative in authorship as appears elsewhere to have been offered with less discretion than decision, would be more perplexing to readers of ‘Paradise Lost’ than to readers of the Book of Job (I do not say the book of Robert Buchanan or of Peter Bell the third). The Devil in Scripture, as we all know, was addicted to going to and fro on the earth, and walking up and down in it, a locomotive habit which may suggest the assistance on his part of at least one quality in common with the bard whose range of vision and visitation is suggested to oscillate between the Seven Dials and ‘the Land of Lorne.’” The article continued at considerable length in a similar strain. Mr. Buchanan sent a paragraph to the Echo simply stating that he had nothing to do with “Jonas Fisher,” and there also appeared a paragraph in the World in which some allusion was made to the Examiner; but with this the plaintiff had nothing whatever to do, though it was attributed to him in the Examiner. The plaintiff, through his solicitors, entered into a correspondence, in the course of which it was stated that “The Devil’s Due” was written by Mr. Swinburne, who, it was said, was prepared to take the full responsibility of the article, and it was suggested that proceedings should be taken against him, and not against Mr. Taylor, but this was declined, and the action went on. The learned counsel, in conclusion, said that in the course of what had been written in the Examiner of the plaintiff he was called “a skulk,” a “shuffler,” “a liar,” and “the idyllist of the gutter,” which surely could not be called fair criticism, Mr. Taylor might know nothing of the article, but he was responsible for it, for he gave an opportunity to Mr. Swinburne not to adversely criticise Mr. Buchanan’s works, but to vent the spleen, spite, and malice which he had conceived, so far back as 1871, against the article by “Thomas Maitland” upon the “Fleshly School,” and during all which time Mr. Swinburne appeared to have nursed his wrath. “There sat, looking mooney, conceited, and narrow, (Laughter). And you also wrote of Mr. Swinburne— “Up jumped with his neck stretched out like a gander.” Has he a long neck?—I do not know.—You also make Mr. Tennyson say of him,— “ ‘To the door with the boy, call a cab, he is tipsy,’ Was he drunk?—He was drunk to publish such a book. No one in his sober senses would publish it. I think what I said was an exceedingly mild way of putting it. I meant only to refer to Mr. Swinburne’s literary character.—You allude to Mr. Tennyson as being— “With his trousers unbraced, and his shirt-collar undone, (Laughter).—This was descriptive of his character, as the other was of Mr. Swinburne.—You say— “Master Swinburne glared out of his hair,” How could a man do that?—(Laughter).—If his hair hung over his eyes it would be descriptive. ___

The Glasgow Herald (30 June, 1876) (p.4) The latest addition to the quarrels of authors is likely to attract some attention and excite a good deal of amusement. The parties involved are Mr Robert Buchanan on the one hand, and the editor and publisher of the Examiner and Mr Swinburne, who is an occasional contributor to that journal, on the other. The affair, which will be settled in the Court of Common Pleas, arose out of a criticism of “Jonas Fisher,” a poem published anonymously but afterwards found to be written by the Earl of Southesk. The Examiner, in the course of its review, discussed a rumour that “Jonas Fisher” was the work either of Mr Buchanan or of the devil, and a letter from Mr Swinburne (who signed “Thomas Maitland,” a former pseudonym of Mr Buchanan) was afterwards published on the same point. Mr Buchanan considers the remarks made as being beyond the limits of fair criticism, and is probably offended at being dragged before the public along with the Prince of Darkness. Hence the present action, which will prove a tit-bit for a few days for those who like a good row.

(p. 6) MR ROBERT BUCHANAN AND THE ACTION FOR LIBEL. In the Common Pleas Division of the High Court of Justice yesterday, Mr Justice Archibald, with a special Jury, heard the case of Buchanan v. Taylor. This was an action by Mr R. Buchanan against the proprietor of the Examiner newspaper, Mr P. A. Taylor, M.P. for Leicester, to recover damages for an alleged libel contained in notices of a poem, which was supposed to have been written by the plaintiff, called “Jonas Fisher.” The defendant, in addition to “not guilty,” justified the supposed libel as being only a fair criticism of the work. Mr Charles Russell, Q.C., appeared for the plaintiff; and Mr Hawkins, Q.C., for the defendant. “There sat, looking moody, conceited, and narrow, (Laughter.) And you also wrote of Mr Swinburne— “Up jumped with his neck stretched out like a gander.” Has he a long neck?—I don’t know. “To the door with the boy, call a cab, he is tipsy— Was he drunk?—He was drunk to publish such a book. No one in his sober senses would publish it. I meant only to refer to Swinburne’s literary character. “With his trousers unbraced, his shirt collar undone, (Laughter.)—This was descriptive of his character, as the other was of Mr Swinburne. _____

The Fleshly School Libel Action - continued

|

|

|

|

|

|

|