|

Play List: 4. Corinne 7. The Mormons 9. Lucy Brandon 10. Storm-Beaten 11. Lady Clare 13. Bachelors 14. Constance 15. Lottie 16. Agnes 17. Alone in London 18. Sophia 19. Fascination 20. The Blue Bells of Scotland 21. Partners 24. Angelina! 25. The Old Home 26. A Man’s Shadow 27. Theodora 29. Clarissa 30. Miss Tomboy 32. Sweet Nancy 33. The English Rose 36. Marmion 37. The Gifted Lady 38. The Trumpet Call 39. Squire Kate 40. The White Rose 42. The Black Domino 44. The Charlatan 45. Dick Sheridan 47. Lady Gladys 48. The Strange Adventures of Miss Brown 49. The Romance of the Shopwalker 52. Two Little Maids from School ___ |

|

ROBERT WILLIAMS BUCHANAN (1841 - 1901) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

THEATRE REVIEWS 36. Marmion (1891)

Marmion

The Echo (8 June, 1889 - p.1) It is a long time since one of the first critics of his day—George Henry Lewes—founder and first editor of the Fortnightly Review—declared the new poet, Robert Buchanan, to be a man of genius. At that time, and since, we have had many smart versifiers who are not poets but poetasters, and critics who are only criticasters. For many a year Mr. Buchanan has been at war with the criticasters, who, like other bundles of sticks, found strength in union—the union of “log-rolling.” They tried to crush him, and they failed. When they boycotted him in the literary journals he took, for a time, to the stage; and the result was that Mr. Buchanan soon became recognised as one of the cleverest, most ingenious, and popular playwrights of his day. _____ Now, Mr. Robert Buchanan is a Scot—a patriotic Scot, none the worse, however, for having been “caught” tolerably young. And, like a patriotic Scot, he has been dramatising the great Sir Walter’s “Marmion”—and for Edinburgh, not for London, at any rate in the first place. Mere politicians of the windy tribe take to Scotch Home Rule as the proper instrument for cherishing the national spirit. But perhaps a week of a first-rate Marmion would be worth a decade of a Parliament in Edinburgh. _____ The new drama is to be put on the boards superbly, and regardless of expense. Holyrood, Castle Douglas, Flodden will be represented as faithfully as stage art can make them. Mr. Buchanan is a Glasgow man. He was born there forty- eight years ago. He took his degree at Glasgow University. He was only nineteen years old when his first volume of poems, “Undertones,” was published. It was his attack on the fleshly school of poetry, seventeen years ago, that first brought about the long war between him and the log-rollers. ___

Glasgow Herald (2 April, 1891) “MARMION” AT THE THEATRE-ROYAL. If there is one thing that more than another distinguishes the career of Mr Howard as a director of the public taste in the matter of stage representations it is his keen sympathy with all that may be regarded as belonging to the branch of the drama that peculiarly appeals to Scottish feeling and nationality. Were such an institution as a National theatre possible among an anti-theatrical people like the Scotch, Mr Howard, above all others, would be the man who might be trusted with its fortunes so far as these depended upon management in keeping with the mind and will of the community. Just because of his ability to accurately gauge the public taste he has been conspicuously successful in the conduct of his numerous enterprises in the dramatic world. To the many proofs he has already given of his desire to foster Scottish drama he is now about to add another, and again he has turned to the pages of the Bard of Abbotsford. In Scott’s romantic poem of “Marmion” Mr Howard has found a theme worthy alike of his purpose and his enterprise. It used to be said, not so very long ago, that it was impossible to “act” Sir Walter Scott. Time, which changes all things, has swept this fallacy away. Sir Walter Scott has now a place, and a high place too, on the lyric as well as the dramatic stage, and who shall set a limit to the position he yet may occupy? It is, however, with the latest achievement rather than future possibilities that we have here to deal. Even the least studious admirer of Scott must know that rich as “Marmion” is in romance, grand and picturesque descriptive poetry, and thrilling dramatic incident, it could not be adequately played in its epic form. Much has had to be accomplished alike in the way of interpolation and omission to meet the exigencies of stage representation. This part of the work has been undertaken by Mr Robert Buchanan, and his task of bringing the text into due compass, while at the same time preserving its spirit and its essential details, has been accomplished with conspicuous success. In the poem each of the six cantos contains a complete and, so to speak, semi-independent portion of the narrative. This division has been almost wholly discarded, and in two important instances at least the sequence of the poem, and even the course of its events, has been materially altered. As it now stands, the romance is much better adapted for stage performance than in the original. The additions of a material kind that have been made are few. Perhaps the most prominent is the introduction in one of the scenes laid in Edinburgh of a brief dialogue, in the dialect of the capital, among a group of the inhabitants as to the probabilities of the coming conflict between Scotland and England. Besides giving an acceptable touch of local colour, this serves, like one or two passages of a similar character, to afford an opportunity for the introduction of comedy. This, however, is very properly resorted to but sparingly, and while the narrative is thus agreeably lightened at some points, its grandeur is never impaired. The “tale of Flodden Field” is preserved throughout, and if some of the flights of poetic genius which mark the original poem—notably the magnificent description of the fatal field, and of the scenes and incidents immediately before the battle—have had to be greatly curtailed, sufficient remains to convey not merely in outline, but in substantial form, the story of “Marmion” in all its brightness and all its gloom, and of the epoch-marking conflict in which the flower of Scottish chivalry were “a’ wede away.” ___

The Scotsman (9 April, 1891 - p. 5) PRODUCTION OF “MARMION” AT THE THEATRE ROYAL, GLASGOW. IN the public compliments paid to Mr J. B. Howard as an actor-manager during the past few weeks special reference has been fittingly made to the attempts he has made to foster what may be called “the Scottish drama.” At the theatres with which he and his partner, Mr Wyndham, are connected the public are familiar with the revivals given from time to time of dramatised versions of the “Great Wizard’s” novels and poems, which with their beautiful Highland setting, and their more or less successful attempts to recall on the stage a bygone period of Scottish history, have been to the Scotsman, and more particularly in the summer time to the stranger within the gate, a source of much instruction and interest. In this connection it is almost needless to mention the operatic setting of “Guy Mannering,” the picturesque drama of “Rob Roy,” and the romantic play, so recently seen in Edinburgh, of “The Lady of the Lake.” Now we owe to Messrs Howard & Wyndham a stage version of that stirring tale of Flodden Field, “Marmion,” which was produced last night at the Theatre Royal, Glasgow, for the first time on any stage. The claim of “Marmion” to be a “national” drama may be questioned. Lord Marmion is an English knight, and it is with his fortunes that the drama, as the poem, mainly concerns itself. But in the production of the play Scottish hands and Scottish feeling have been predominant. The adaptation of the poem to fit it for stage representation has been made by Mr Robert Buchanan; Professor Mackenzie has written a Marmion overture and the incidental music; Mr Glover has painted the scenery; and Mr Howard, under whose direction the whole drama has taken shape, has lived so long in Scotland that in respect of his art, at least, he may be claimed as a son of the soil. We can all recall the pleasure which this well-told tale of chivalry has excited. We have sorrowed over the wrongs of the misguided and betrayed Constance Beverley; sighed over the persecution of Clare, and rejoiced in her victory; praised De Wilton for his constancy as a lover; and, despite the dark blot on Marmion’s escutcheon, admired the courage and gallant bearing of the Falcon Knight. Scott’s tale is, in fact, full of dramatic incident, but being from beginning to end a narration by the Northern Minstrel, without almost a shred of dialogue in it, the task of the adapter to fitting it for stage representation was not an easy one. In the drama, the thread of the story running through the poem is well preserved. Marmion first appears at Norham Castle, journeys under the guidance of De Wilton by Gifford to Edinburgh to have his interview with King James, and returns to his own country by Tantallon Castle. But for the sake of effect, incidents are introduced or amplified in a way which the playwright is quite justified in doing. Constance, for instance, accompanies Lord Marmion to Norham Castle in her page’s attire, and in the first and second acts is no inconsiderable figure. As she disappears from the scene in the gloomy dungeons of the Benedictine Convent, Clare appears, and thereby the continuity of the feminine element in the play is preserved. In the scene at Tantallon Castle, Marmion in the play is made to carry off Clare by force from under the roof of the Douglas; and a street scene in Edinburgh is represented in which groups of citizens discuss the prospects of the war. Mr Buchanan has cast the drama in the same metre as the poem, and where he has been able to do so he has of course used Scott’s lines. Where he has invented, he has very happily caught the spirit and rhythm of the poet’s versification, so that at many points, unless by those who know Marmion well, it is difficult to say where Scott ends and Buchanan begins. ___

Glasgow Herald (9 April, 1891) “MARMION” AT THE THEATRE-ROYAL. For the first time on any stage a dramatised version of Sir Walter Scott’s “Marmion” was performed last night at the Theatre-Royal. First productions—always important events in the dramatic world—are rare occurrences in Glasgow in these latter days, and the introduction of “Marmion” was, on that account, doubly interesting. Mr Howard’s present venture had been looked forward to with lively anticipation for some time, and the crowded state of the house when the curtain rose was a significant indication of the expectations that had been raised, and a flattering tribute to the popularity of the actor-manager. In the domain of Scottish drama Mr Howard long ago made an enviable reputation. In the hero of the poetic tale of Flodden he finds a part not less romantic and engaging than others with which his name is now peculiarly identified; while from the dramatic standpoint it is a more difficult and—if one may presume to say so with all respect—a more worthy study than even Rob Roy or Roderick Dhu. The Marmion of Sir Walter Scott is at once a knight, a courtier, a lover, and a soldier: in love and friendship as false as dicers’ oaths, in arms the bravest of the brave. It is a character which may well attract any actor, and in it Mr Howard has added to the many parts he has played one which, though coming late, will rank among the foremost and best of his creations. But it is not alone or mainly because Mr Howard has thus found fresh scope for his skill as an actor that the present production claims attention; it is noteworthy also, and chiefly, because it gives a new standard play to the comparatively limited field of Scottish drama, and because it has been inaugurated with a completeness as regards scenery and other stage accessories that make its first representation a memorable occasion in the annals of the local theatre. The difficulty of presenting an epic poem such as “Marmion” in the form of a stage play is self-evident. Changes in the sequence of events and even departures from the main lines of the narrative were inevitable, and in effecting these Mr Howard wisely availed himself of the assistance of a master in play-writing. Mr Robert Buchanan undertook the duty, and how well he fulfilled the task was amply testified last night. From the opening scene the interest was not only sustained but increased in intensity until the curtain fell upon the final tableau, while over all there seemed to breathe the poetic spirit and the martial fervour of the Bard of Abbotsford. As a play pure and simple, “Marmion” at once claims a leading place, and it has been richly embellished. Mr William Glover is an artist of whom any theatre may well be proud. The scenery of “Marmion” is his latest achievement; it is also undoubtedly his best. Dr A. C. Mackenzie has been equally happy in the incidental music. As has thus been indicated, the production was an unqualified success. In the course of a few words to the audience at the termination of the play, Mr Howard claimed for it a magnificent triumph. His claim was not overstated. It was conceded by unanimous and vociferous assent, and it is a safe prediction that subsequent representations will confirm and emphasise the verdict so justly won and so generously given. ___

The Stage (16 April, 1891 - p.14) PROVINCIAL PRODUCTIONS. “MARMION.” On Wednesday, April 8, 1891, at the Royal, Glasgow, was produced a version of Sir Walter Scott’s poem, “Marmion,” dramatised by Robert Buchanan, with music by Dr. A. C. Mackenzie, entitled,— Marmion. Marmion ... ... ... Mr J. B. Howard Scotland already owes a debt of gratitude to Mr. J. B. Howard and to the management with which he is associated for the splendid work they have done in fostering a national drama, particularly in the case of dramatised versions of the works of Scotland’s great son—Sir Walter Scott. The Rob Roy of this decade, as of the past, is that of Mr. Howard, not only from the lavish care which has been spent upon the production, but also because the part of the bold McGregor is one which Mr. Howard has made his own. The beautiful representation of The Lady of the Lake is still fresh in our minds with the lovely series of pictures of the wildest and grandest of the Scottish mountain and lake scenery. In many respects the present representation of Marmion not only excels Rob Roy and The Lady of the Lake, but as a spectacle rivals anything which has been presented on the Scottish stage. The battled towers, the donjon keep, Hither comes Lord Marmion at close of day on his way to the Court of King James at Holyrood, as the ambassador of King Henry of England, his errand being to make terms of amity between the two countries, and avert the threatened invasion of England by the Scottish King. Marmion enters the courtyard with his mail-clad retinue and is received with all the ceremony of those chivalric days by Sir Hugh, the Heron captain of the hold. The second scene is a front cloth of the armoury of the castle, and is chiefly occupied by preparations for the banquet in Marmion’s honour which is to follow. Here and interview takes place between the knight and Constance de Beverley, who accompanies him as his page. Marmion, who now loves Lady Clare (De Wilton’s bride), has tired of Constance, who for his love has broken her vows as a nun and fled from a convent. The banquet hall at Norham Castle, which forms the third scene, is a magnificent representation of an old baronial hall. It occupies the entire stage. It is enriched with every variety of accessory and detail, and yet preserves a noble simplicity and unity of design. The oak-beamed roof, the wide open fire-place, the elevated musicians’ gallery, the raised daïs on which sit Lord Heron and his guests, the tables ranged down the room at which are seated and grouped knights, squires, and pages, together form a mise-en-scene, the artistic impressiveness of which will remain long in the memories of those who have witnessed it. Marmion discloses his errand to Heron, and requests a guide to Holyrood. After rejecting those suggested by heron, Marmion accepts the offer of a Palmer. This, as the audience is at once permitted to see, although Marmion is himself ignorant of the fact, is no other than De Wilton, the noble knight whom marmion, by the aid of papers forged at his suggestion by Constance, has disgraced and dishonoured. There is a fine passage full of dramatic effect between the two men, the one knowing his enemy, and the other not recognising his former foe, who he thinks is dead, but uneasy at some vague recollection. The action of the second act takes place in the hostel, the landlord of which recounts the weird legend of the Pictish camp near at hand, where the man who is bold enough may at midnight, in flesh or in spirit, meet his most bitter foe. When the others have retired to rest, Marmion, who is restless and ill at ease, resolves to test the truth of the legend and steals out into the night. The Palmer, knowing his intention, also leaves, and doffing his gown and hood meets him at the Pictish camp. The scene here revolves and discloses the two in deadly combat among the ancient monoliths of the camp. De Wilton has got Marmion at his mercy, but spares his life in redemption of a promise he had made to a dying retainer who had followed his fallen fortunes in foreign lands. The scene reverts to the hostel where the ill-fated Constance is seized by the emissaries of the Church of Rome. Marmion makes a half-hearted pretence of rescuing her, but allows himself to be overawed by the Abbot’s threat of anathema. The third act is full of pictorial effect, ambitiously designed and most successfully executed. The Abbey of St. Hilda, at Whitby, is revealed when the curtain rises, and from the landing stage the Abbess, accompanied by Lady Clare and several nuns, embarks on a galley which is to carry them to Lindisfarne, where the trial of Constance for apostacy is to take place. There is here unrolled a panorama of the English coast from Whitby to Lindisfarne, which is best described in a transcript from the poem itself:— And now the vessel skirts the strand At Coquet Isle their beads they tell, On Dunstanborough’s caverned shore Then from the coast they bore away The various pictures are all beautifully marked by that living fidelity to nature and to art which always distinguishes Mr. Glover’s work. In the second scene (the Cloisters of the Abbey) De Wilton finds an opportunity of revealing himself to Clare, after which there is an impressive ecclesiastical procession singing the dies irae which fittingly preludes the succeeding solemn scene in the cell in which the trial of Constance takes place. The ill-fated girl is condemned to a painful death, and before being carried away she entrusts to the Abbess a packet of papers containing ample proofs of Marmion’s treachery to De Wilton. The first scene of the fourth act is the Camp near Crichton Castle, where Marmion is met by the Scottish Lion-King-at-arms, Sir David Lindesay, who bears with him messages from King James. After a front cloth of a street in Edinburgh, the third scene, an interior in Holyrood Palace, is revealed. It is perhaps hypercriticism to complain that this scene with all its magnificence, its brilliancy, and its gaiety—for it is eminently distinguished by all these characteristics—is yet from an artistic point of view unsatisfactory, marking as it does, with its commonplace note of colour, a falling away from the high level maintained in the series of tableaux. Marmion delivers his message to King James, who receives it courteously, but in a spirited speech informs him that the request is without avail: Our full defiance, hate, and scorn, The Abbess with Clare has come to Holyrood to crave protection from James, and is handed over to the care of Lord Douglas, with whom also Marmion is bidden to stay until the war has commenced. The scene closes with a graceful minuet, led by the King and Lady Heron, the fair and frail dame with whom it is said he dallied away his time at so dear a cost as victory and life. The fifth act opens with a room in Edinburgh Castle, where De Wilton and Clare have another meeting. In the second scene, the gardens of the castle, Douglas, has occasion to protect Lady Clare and the Abbess from Lord Marmion’s desire to carry them away. The third scene is a capital act representing the Courtyard of Tantallon Castle. De Wilton is now restored to the full honours of knighthood by Lord Douglas, to whom the contents of the packet held by the Abbess are revealed, and he departs to join the English army. Marmion enters and endeavours to persuade Clare to accept his love and depart with him. This she refuses to do, and is eventually carried off by force. Marmion then takes leave of Douglas, and offers his hand, which Douglas refuses to take. My castles are my King’s alone, For some reason which is not quite apparent this scene is to an extent robbed of its full effect by the omission of the fine speech from the poem, ending— Lord Angus, thou hast lied! This is the most dramatic passage in the poem, and should also be so in the play. In scene four Marmion with Clare and his retainers comes in sight of the opposing armies, and in the closing scene he leads her to a spot where she can in safety witness the fight, and departs himself to join the fray. The progress of the battle is vividly described in the exclamations of Clare and the two knights, Blount and Fitz-Eustace, who are left to guard her. When the knights see Marmion’s falcon pennon fall they rush off to the aid of their lord, and Clare is left alone. Soon Marmion—this brave soldier and false lover—is borne in from the field wounded unto death. he hears the thundering cheers which proclaim the day is with the English army, and then With dying hand above his head, and dies. ___

The Era (18 April, 1891) “MARMION.” Dramatised by Robert Buchanan, Marmion ... ... ... Mr J. B. HOWARD (FROM OUR OWN CORRESPONDENT.) For their spirited enterprise in producing this specially prepared stage adaptation of Sir Walter Scott’s “Tale of Flodden Field” Messrs Howard and Wyndham deserve the warmest thanks of all lovers of the poetic and beautiful in connection with dramatic art. The production is certainly one of the most elaborate— if not the most elaborate—witnessed in the provinces for twenty years past, and has only been placed before the public after many months of anxious thought, careful research, arduous labour, and a lavish outlay of money. The historical and archæological accuracy of scenery, costumes, properties, and general paraphernalia vouch for this, and show how much in earnest the management have been in their efforts to do justice to Scott’s grand narrative. Recognising this fact to the fullest extent, we have exceptional gratification in recording for Marmion a triumphant success. It is, however, a triumph for the scenic artist, costumier, and stage-manager, rather than for the dramatist; but if Mr Buchanan has not added to the literature of the stage a great acting play, he has provided a very pleasing and coherent vehicle for a grandly picturesque and animated spectacular display, which it would be difficult indeed to surpass. It may be freely conceded that Mr Buchanan has done his part well in adapting the poem to the stage. To dramatise an epic poem such as “Marmion” is no easy task, and if the play is sometimes lacking in dramatic action, and is occasionally weak in human interest, the blame does not belong entirely to the dramatist. It is apparent throughout that he has striven to do his work conscientiously, and in giving us the noble verse of Scott, descriptive of the shock of arms, instead of substituting realistic action, we recognise a lofty desire to take as few liberties with the original text as possible. In short, had Mr Buchanan been less reverent of the poem, the result of his labours might have been more satisfactory from a dramatic point of view. But, after all, any shortcomings noticeable in Marmion as a drama are amply atoned for by the almost embarrassing richness of the spectacular effects. The play is divided into five acts, which are subdivided into sixteen scenes in all, introducing in regular sequence a series of brilliant tableaux illustrative of the most salient incidents of the poetic romance. ___

The Era (25 April, 1891 - p.10) ONE of the minor parts in Marmion, now being played to crowded houses in the Theatre Royal, Glasgow, is that of the landlord of the hostel, played by Mr H. Dalton Robertson, and some natural curiosity has been expressed as to why Mr Robertson should hobble about on the stage like a Dutch lugger in a head sea, or a half-pay captain far-gone with gout. The reason is not far to seek. Some years ago, when Mr Robertson was playing a minor part in The Lady of the Lake, at the Lyceum Theatre, Edinburgh, he had to submit himself to the tender mercies of Fitz James, and allow himself to be thrown over a cliff. One unfortunate night, through the carelessness of an attendant, the throw was too realistic, for no one was at the foot of the cliff to receive Mr Robertson. He sustained serious injuries to his legs, and has not been so active on his feet since. It says much for the kindheartedness of Messrs Howard and Wyndham that they still retain Mr Robertson’s services. He acts his part admirably, and recites “The Host’s Tale” with considerable power. |

|

|||

|

[Advert for the final performances of Marmion from the Glasgow Herald (2 May, 1891).]

The Era (2 May, 1891) “MARMION.” Sir,—In the dramatic and musical columns of The Daily Telegraph of the 17th inst., speaking of the production of Marmion at Glasgow, was the following statement:—“It is noteworthy as being the first attempt to put the story of the poem into the form of a stage play.” ___

The Era (9 May, 1891) “MARMION.” Sir,—Permit me to supplement the remarks of Mr Telfer in his letter of last week referring to the production of Marmion at the Theatre Royal, Glasgow. The statement in the Daily Telegraph was incorrect. So far from Mr Robert Buchanan having any claim to be considered the first who has adapted the poem for stage purposes he comes in but as third or fourth on the list. _____

TO THE EDITOR OF THE ERA. Sir,—In reply to Mr Joseph Tilfor in last Saturday’s Era, let me say that the paragraph to which he refers as having appeared in the Daily Telegraph of April 17th, in connection with the production of Marmion in Glasgow, did not emanate from me. We have advertised the production of Marmion for the first time on any stage as arranged for dramatic representation by Robert Buchanan. ___

The Stage (14 May, 1891 - p.8) GLASGOW. ROYAL (Proprietors and Managers, Messrs. Howard and Wyndham; Acting-Managers, Messrs. Frank Sephton and Fred. C. Cowlard).—On Thursday the spacious auditorium was crowded in every corner with a large and brilliant audience, assembled to do honour to Mr. and Mrs. J. B. Howard on the occasion of their annual benefit. Mr. Howard deserves well of Scottish playgoers, and it was gratifying to notice that his claims were recognised with unmistakable heartiness by a large and representative gathering of Glasgow citizens. Mr. Howard in his arduous duties as actor and manager is ably seconded and assisted by Mrs. Howard, whose impersonation of the Abbess in Marmion is a feature in the production. Marmion, of course, formed the programme for the evening, and was throughout very warmly applauded. At the end of the fourth act, in response to a most enthusiastic call, Mr. Howard appeared in front of the curtain and addressed the audience. He expressed his heartiest thanks for many favours received from them during the past twelve months. That had been a memorable year; and he hoped in the history of the Scottish stage, and particularly the Glasgow stage, the production of Marmion would be a memorable event. The fame of Marmion had already reached London, and he had received an urgent request from a manager in London to transfer bodily the piece as it stood to one of the leading theatres in the metropolis. He was sorry he could not yield to the tempting offer because he considered the obligations and duties to friends at Edinburgh and Glasgow of more importance. They purposed to inaugurate the season here at the beginning of August with Marmion. (Applause.) During the autumn season they would have an opportunity of welcoming once more Mr. Tree and the entire Haymarket company. (Applause.) One of the memorable events of the present year would be Sir Arthur Sullivan’s Ivanhoe. (Applause.) Scott once more in the ascendant! (Applause.) Then in the course of the season—and no season would be complete without it—they would have the Carl Rosa Grand Opera Company. (Applause.) And last, and by no means least, additional interest and charm would be provided in the visit of Henry Irving, Miss Ellen Terry, and the entire Lyceum company in their répertoire. (Applause.) Among many other attractions would be their dear old friend, J. L. Toole. (Applause.) And to wind up with, the pantomime at Christmas would be Little Bo-Peep. (Applause.) ___

The Times (29 June, 1891 - p.7) A dramatised version of Scott’s “Marmion,” by Mr. Robert Buchanan, with special music by Dr. A. C. Mackenzie, was produced in the Royal Lyceum Theatre, Edinburgh, for the first time on Saturday night. All the most striking scenes and passages in the poem are reproduced in the drama. The performance was very successful, and was received with enthusiasm by a brilliant house. ___

The Glasgow Herald (29 June, 1891 - p.9) “MARMION” AT THE LYCEUM After its successful run in Glasgow, Messrs Howard & Wyndham on Saturday night presented “Marmion” to their Edinburgh patrons. The fame of the play had gone before it, and despite the beauty of the evening and the warmth of the summer air, the Royal Lyceum Theatre was crowded when the curtain rose with an eagerly expectant audience. It may at once be said that the production was a magnificent success, and that the proprietors may with certainty look forward to full houses for the few weeks during which the play is to occupy the boards. The audience on Saturday night were in a state of admiration all through the performance, and at many points they manifested the utmost enthusiasm. The ancillary circumstances, too, were such as to conduce to the full enjoyment of the play. During the few weeks of the annual recess, which are just ended, the theatre has been handsomely redecorated, and the pleasure this gave to the eye was enhanced by the comparative coolness of the atmosphere, despite the large audience, arising from the use of the electric light in place of gas. This method of lighting is not now a novelty at the Lyceum, but it seemed to chime in with a special feeling of fitness on Saturday evening. The surprise and delight of the spectators was aroused by the very first scene, and as picture after picture full of artistic beauty and strength was unfolded, these feelings were perpetuated with ever-increasing force. The dresses and accessories so true to the early part of the sixteenth century were only less admired. Probably Edinburgh playgoers can only recall one other instance of such elaborate and perfect stagecraft—that of the great productions of Mr Irving. In such circumstances one gladly looks over the defects of “Marmion” as a play. The lack of that intense unity which should be a characteristic of a romantic tragedy is forgotten, and the more so when one remembers that this is a stage representation of a romantic poem which has no dramatic pretensions whatever. For the same reason one overlooks the want of due proportion and subordination of character and incident, and instead admires the skill of Mr Buchanan in the adaptation he has succeeded in making. Mr J. B. Howard appeared to great advantage as Marmion. Acting with a proper reserve of power, he on the one hand sufficiently emphasised the unlovely traits of the warrior’s character, while on the other his bright touches in bringing out the nobler qualities as they struggled with the baser showed real histrionic power. Mr F. W. Wyndham gave a dignified, courtly, and altogether adequate representation of King James, and the same may be said of Mr F. Douglas as Lord Douglas. Mr Edward O’Neil as De Wilton was just a trifle stagey, but the part is a very trying one, and his performance was creditable. Miss Maggie Hunt as Constance Beverly had some exacting work in the first half of the play, and she nobly responded to the calls made upon her. The shrill shrieks and grotesque gesticulations of the conventional damsel in distress are quite foreign to Miss Hunt, and she acted with a sweetness and pathos which will make her a favourite of all visitors to the theatre during the next few weeks. Miss F. Kingsley, on the other hand, was scarcely so successful in giving interest to the part of Lady Clara; at some of the crucial points she seemed to lack power. The other parts were very fairly filled, and, taking it all over the caste is an excellent one. The curtain fell on the final tableau amid round after round of rapturous applause, and Mr Howard then came forward and addressed a few words to the audience. He said he thought they had heard quite enough from him that night, but he could not refrain from bringing before them one of the men who had contributed a great deal to the success of “Marmion.” (Applause.) Here Mr Howard presented to the audience Mr William Glover, the artist who painted the entire scenery. Mr Glover was received with loud applause. Continuing, Mr Howard said he would like to say a little, but he was somewhat exhausted, as they could imagine, not only with the work of that night, but also with the anxiety of the past week. But, as he was sure they would freely admit, his colleagues and he had achieved an unmistakable success. (Applause.) It had been the dream of his managerial life to do something for Sir Walter Scott that had not been done before in Edinburgh—(applause)—and were Sir Walter’s spirit permitted to revisit the glimpses of the moon he had been hovering over them that night, and he would be gratified and pleased with the magnificent pictures of his fancy and imagination that the management of the theatre by the aid of everybody around them had been able to put before the audience. (Applause.) He (Mr Howard) was sorry the dramatic constructor (Mr Robert Buchanan) was not present to hear the enthusiastic cheers, and last but not least, their dear old friend and true Edinburgh man and Scotsman, Dr Mackenzie. (Applause.) Mr Howard then brought forward his coadjuter, Mr Wyndham, who was also received with loud cheers. In conclusion, Mr Howard said he must not in the hurry and the anxiety of the occasion forget the invaluable assistance they had derived from those the audience had not seen, the management’s servants behind the curtain. (Applause.) It had been to them, as to the managers, an anxious time, and they had done their very best that not a single hitch should occur to mar the harmony of the whole representation. (Loud applause.) ___

The Era (4 July, 1891 - p.16) AMUSEMENTS IN EDINBURGH. . . . LYCEUM THEATRE.—Proprietors, Messrs Howard and Wyndham; Acting-Manager, Mr A. Weston.—On Saturday, the 27th ult., took place the first representation in Edinburgh of Marmion. The theatre which, during the recess, has been entirely redecorated and refurnished, was crowded in every part with a fashionable audience, and enthusiastic applause followed each of the sixteen romance-laden scenes presented. In this poetic production Mr Howard has surpassed himself. Immense pains and liberal expenditure have been lavished upon the preparation of the work, and Saturday evening’s success we are convinced will not only be permanent, but will still further enhance the high reputation of the management. Mr Howard said, at the conclusion, that it had been the dream of his life to do something for Sir Walter Scott that had never been done before, and certainly in this magnificent spectacle the actor-manager’s highest ideal has been realised. In arranging this stirring record of the days of feudalism and chivalry for the stage, the managers have been fortunate in securing the co-operation of some of the most eminent men of the day. Mr Robert Buchanan has performed the difficult work of dramatisation in a highly meritorious manner, and Dr. Mackenzie’s original music has been well received by his numerous admirers. The scenery by Mr William Glover is of a beauty that almost surpasses description, castle and tower, land and seascape, panorama and interior, affording wide range for the exercise of his picturesque powers as a painter. Dresses of the period, designed by Cattermole, historically correct armour and accoutrements by Kennedy, and properties of antiquarian exactitude, lend largely to the general effect, and a well-chosen company contribute satisfactorily to the dramatic interest of the occasion. Mr Howard’s Marmion was a grand performance. In his superbly handsome attire, he looked exactly the chivalric English knight, his bearing being noble and dignified, and his acting marked with great power and intensity. The impressive death scene gave a supreme opportunity for histrionic display, and was the crowning effort of an artistic and altogether admirable representation. Seldom, indeed, has a demonstration taken place within these walls so hearty and so enthusiastic as that which followed the final fall of the curtain. Mr F. W. Wyndham, who worthily shared the managerial honours of the evening, sustained the rôle of King James IV. with a royal bearing, a courtly animation, and a telling elocution that were alike effective. Mr A. Alexander was a painstaking Lord Heron, and Mr Walter Grayling an excellent FitzEustace, his song “Eleu loro” obtaining considerable applause. Valuable support was given by Mr Edward O’Neill as De Wilton, a remarkably fine performance; and by Mr F. Douglas, who was particularly good as Lord Douglas. Other characters were carefully filled by Messrs Henry Moxon, S. Barrington, and Tom Walker. Miss F. Kingsley’s impersonation of the Lady Clare was natural and pleasing, and Mrs Howard gave an impressive embodiment of the Abbess of St. Hilda. As Constance Beverley Miss Maggie Hunt exhibited deep tenderness and feeling, her shapely figure suiting well the page’s doublet and hose; while the tragic intensity and profound and exquisite pathos of her acting when the doom of Constance is finally sealed won for the actress a well-deserved recall. Miss Charlotte Hamilton sang Dr. Mackenzie’s “Young Lochinvar” with charming vocal freshness and characteristic effect; and Miss Effie Goodwin also had music which she rendered with excellent taste. The orchestra, largely increased, formed, under the able conductorship of Mr W. A. Leggatt, an attractive feature, and did full justice to Dr. Mackenzie’s spirited overture, as well as to the pleasantly scored songs and entr’actes so happily introduced throughout the play. ___

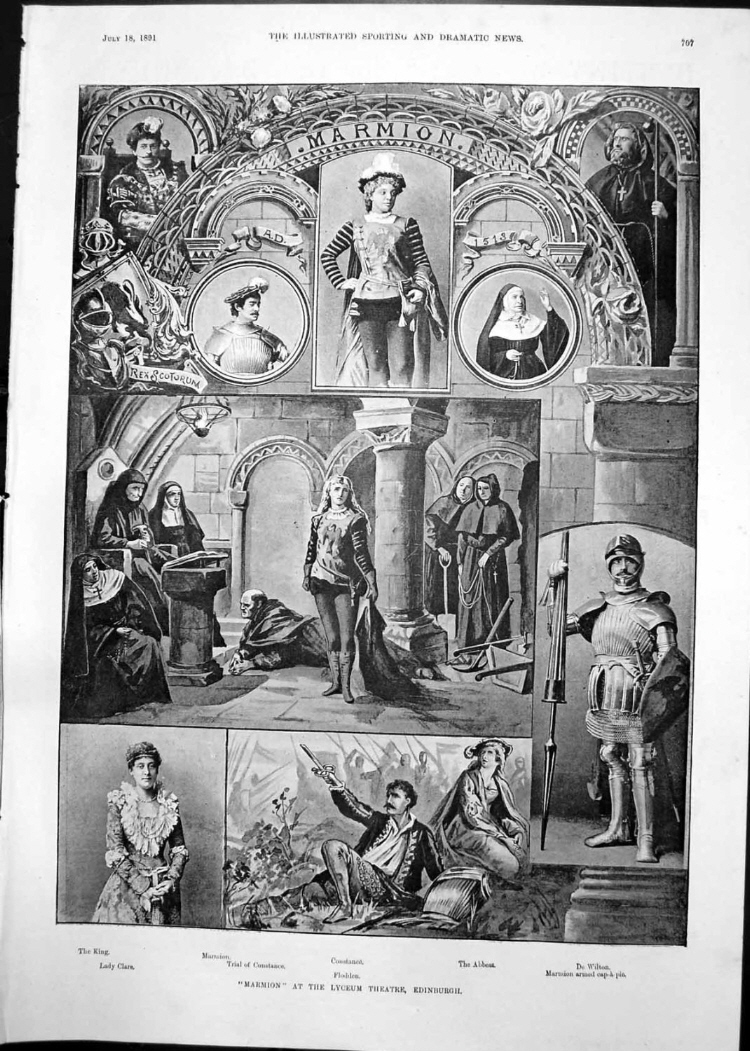

The Illustrated Sporting and Dramatic News (18 July, 1891) |

|||

|

|

The Era (12 September, 1891) MR ROBERT BUCHANAN’S adaptation of Sir Walter Scott’s poem “Marmion” has been withdrawn from the Scotch stage for a year, and it is understood that Messrs Howard and Wyndham intend producing it at a London theatre. It is also stated that they are making extensive preparations for the production of a dramatic version by Mr Buchanan of Scott’s “Lady of the Lake,” and that Mr William Glover, the veteran Scotch artist, has been commissioned to paint the scenery, which will be on as magnificent a scale as that of Marmion. _____

Next: The Gifted Lady (1891) Back to the Bibliography or the Plays

|

|

|

|

|

|

|