|

Play List: 4. Corinne 7. The Mormons 9. Lucy Brandon 10. Storm-Beaten 11. Lady Clare 13. Bachelors 14. Constance 15. Lottie 16. Agnes 17. Alone in London 18. Sophia 19. Fascination 20. The Blue Bells of Scotland 21. Partners 24. Angelina! 25. The Old Home 26. A Man’s Shadow 27. Theodora 29. Clarissa 30. Miss Tomboy 32. Sweet Nancy 33. The English Rose 36. Marmion 37. The Gifted Lady 38. The Trumpet Call 39. Squire Kate 40. The White Rose 42. The Black Domino 44. The Charlatan 45. Dick Sheridan 47. Lady Gladys 48. The Strange Adventures of Miss Brown 49. The Romance of the Shopwalker 52. Two Little Maids from School ___ |

|

ROBERT WILLIAMS BUCHANAN (1841 - 1901) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

THEATRE REVIEWS 42. The Black Domino (1893)

The Black Domino |

|

|

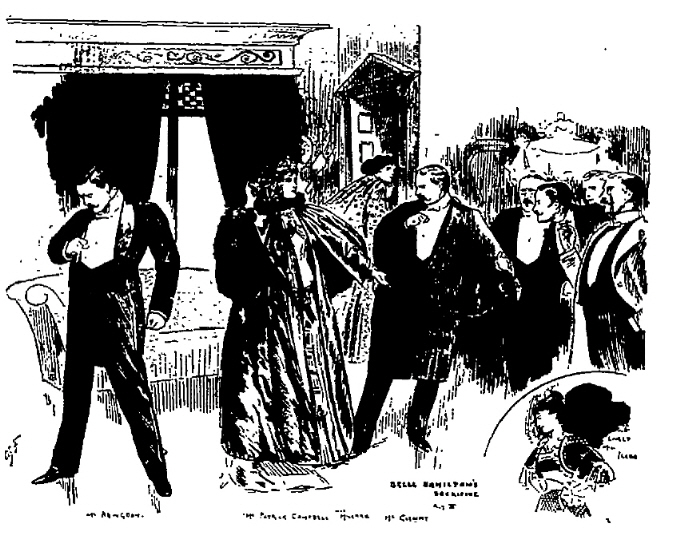

[W. L. Abingdon as Captain Greville, Arthur Williams as Joshua Honeybun

The Referee (16 October, 1892 - p.3) Mr. G. R. Sims and Mr. Robert Buchanan have been observed armed with guns in the neighbourhood of Leighton Buzzard, where the Highland minstrel has a shooting box. Up to the present no casualties are reported, not even to a rabbit. The poet is a most humane man, and whenever by accident his gun goes off and kills a rabbit he always sheds a sympathetic tear before he takes it home and gives instructions about the onion sauce. Mr. Sims assured an interviewer who found his with a gun that he only carried it to exercise his nerves, which have lately gone considerably wrong. He is at Leighton Buzzard with the Bard, collaborating not in game, but play—a play which in the fulness of time will face the footlights at the Adelphi. ___

The Leeds Mercury (31 March, 1893 - p.2) Messrs. George R. Sims and Robert Buchanan’s new play, “The Black Domino,” will be performed for the first time at the Adelphi Theatre, on Saturday evening. Some idea of the character of the piece may be gathered from following the description of the scenes:—Act 1. The Village Church; the Pink Wedding. Act 2. The Fancy Dress Ball at Covent-garden. Act 3. Covent-garden Market in the early morning; Bow-street Police-station. Act 4. Pierre Berton’s Lodgings; Honeybun and Co.’s Office. Act 5. The Terrace of the Star and Garter, Richmond. ___

Lloyd’s Weekly Newspaper (2 April, 1893) LAST NIGHT’S THEATRICALS ADELPHI. In the presence of a large and enthusiastic house, Messrs. G. R. Sims and R. Buchanan’s new drama, A Black Domino, was produced last night. The play is distinctly of the type made familiar to Adelphi patrons by these authors dealing with present-day life, and made as picturesque as possible by elaborate scenes. The literary merit of the work, however, is not so obvious as the desire to present elaborate stage pictures. It had, however, a hearty reception, and will be a strong holiday attraction. The story opens with a charming rural scene, a village church where Lord Dashwood, the master of the local hunt, is about to be married to Mildred Vavasour, after sowing very wild oats and casting off a notorious and worthless woman, who is the runaway daughter of an old Frenchman, the village organist. Coming back to her father’s home this woman hears the news of the marriage, and prompted by a disappointed lover of Mildred’s Captain Greville, is about to expose the past to the bride, when the old organist breaks in upon the scene, and compels her to silence. This is the keynote of the story, which proceeds with a conspiracy by Greville, a rascally money-lender named Honeybun, amusingly played by Mr. Arthur Williams, and “Belle Hamilton,” the old love, to ruin and disgrace Dashwood. Belle gets him into her toils, once more, ruins him by her extravagance, and he is even egged on to forge the name of his father to a bill. Mildred at last learns the truth, and as “the black domino” of a ball at Covent Garden, sees the depth of his shame. This scene is the great scene of the piece, a most remarkable and brilliant illusion by Mr. Bruce Smith, which drew the heartiest recognition from Sir Augustus Harris, who sat, an amused spectator, in the stalls. Another fine set is Covent-garden market at early dawn. But possibly the finest, from an artistic standpoint, was a lovely view of the terrace of the “Star and Garter” at Richmond, by night. The repentance of Dashwood begins at the ball, and his love for his deceived wife is aroused by the news that Greville has carried her off to his chambers in a fainting condition. From this danger, however, she is released by Belle, who also assumed the repentant role when she finds herself the tool of Greville. Finally Dashwood is forgiven, and a tragic ending is given to the piece by the suicide of Belle Hamilton. It must be admitted that the story is more dramatic than probable, and that the piece has not the solidity of previous dramas, but popular sympathy follows it. The crucial situation comes with the discovery of Dashwood’s forgery and the unexpected declaration from his father that he, the Earl of Arlington, wrote the signature. The drama is rather overweighted with superfluous characters, but there is a comic interest agreeably sustained by Mr. A. Williams, Mr. Welton Dale, and Miss Clara Jecks, the latter as a good-hearted music-hall artiste. Mr. Glenny makes the vacillating Dashwood as earnest as possible, and Miss Evelyn Millard is a sympathetic Mildred. To Mr. Abingdon is, of course, assigned the scheming Greville. The Belle Hamilton has an imposing representative in Mrs. Patrick Campbell, who was cold and ruthless in her sin, and touching in her repentance, brought about by the sorrows of her old father. Mr. W. Dennis, as the old Earl; Mr. G. Cockburn as the old organist; Mr. John Le Hay, as an Irishman on tour; Mr. T. B. Thalberg, as a good-natured young doctor, and Miss Bessie Hatton, as a virtuous daughter of the organist, each have parts of more or less importance. At the end there were enthusiastic calls for the authors, who appeared; for the stage manager; and for Messrs. Gatti; indeed, there were not wanting the usual recognitions of earnest endeavour. ___

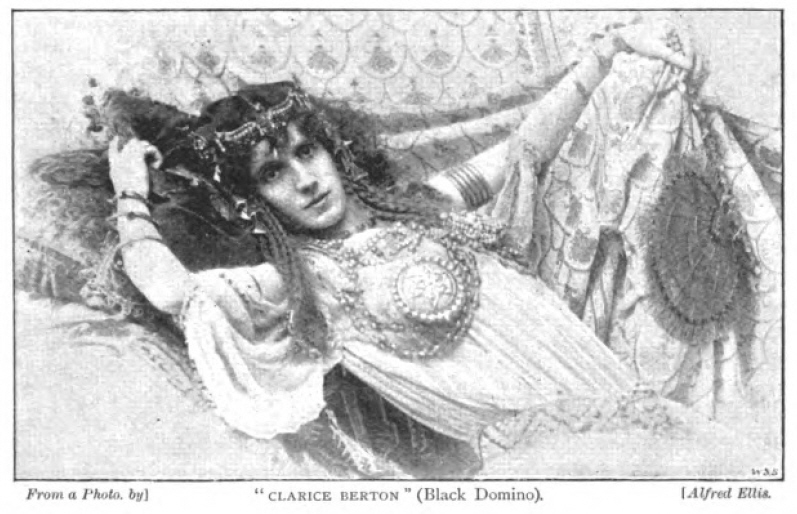

The Referee (2 April, 1893 - p.3) ADELPHI—SATURDAY NIGHT. In “The Black Domino,” Messrs. Sims and Buchanan have evidently sought to “catch the manners living as they rise,” and their daring has been justified by the success of the new play, which was received to-night (Saturday) with thunders of applause. It is a drama of the present day—up to the very minute. The central figure of the story, Lord Dashwood, is a fine young English gentleman all of the modern times, urging on his wild career through scenes that are striking in their actuality. The authors have availed themselves freely of the resources of the Adelphi Theatre. They afforded opportunities, in the course of the story, for a series of realistic pictures of modern life, which are presented on the spacious stage with an extraordinary power of illusion; but the craft of the dramatist is exercised with such tact that the interest of the play is never subordinated to the exigencies of the scene. The action is not arrested as it sometimes is in plays in which spectacular effect is no mere secondary consideration. The great scenes proceed naturally from the events of the drama. Yet such wonders have been worked in this direction that “The Black Domino” would still be a play to be seen and remembered even had it been less stimulating in itself. It is to the credit of the authors that they have made such good use of the means at their command. The play begins with the marriage of Lord Dashwood with Mildred Vavasour, a pretty touch being given to the scene by making a Pink Wedding of it. Lord Dashwood, who has the reputation of a sad rake, is bent upon reformation, but on the day of his wedding his sins find him out, for he not only receives an unexpected visit from a money-lender, but comes face to face again at the church-door with Clarice Berton, a woman who owes her ruin to him. Under the name of Belle Hamilton, Clarice has become a notorious character of the town, and it is when her father comes out of the church, at which he is engaged as organist, that he first hears of his daughter’s shame. In the next act the young husband’s good intentions are already helping to pave the old road, being assisted on the downward grade by his friend, Captain Greville, a determined villain, who means to revenge himself upon Dashwood for having supplanted him in Mildred’s affections. Greville finds an instrument for his malice in Clarice, and having arranged that Dashwood shall meet her at a Fancy Dress Ball at Covent Garden, to which the young lord agrees in the hope of being able to break off finally with her, Greville’s next move is to excite the wife’s jealousy. For the purpose of following her husband she persuades her brother to take her to the ball, and there she falls in with Greville, who sees through the disguise of her black domino and carries her off exulting to his chambers, when she faints after being presented to her husband, who is acting as cavalier to Clarice. A veritable masterpiece of realism is the scene of the Fancy Dress Ball at Covent Garden—better even than the real thing, for there is more wit going than may generally be heard in a crowd, and in the vestibule leading (in more than one sense) to the grand scene of the ball there is a smart passage between Miss Clara Jecks and “The Bust of Homer,” who is supposed by one young spark to have written “Paradise Lost.” The scene of the ball is a marvel of mise en scène, the interior of Covent Garden being represented crowded with dancers and an animated company in the boxes. Fancy dress balls we have had before on the stage, but this scene perhaps eclipses in its details and its perfection of ensemble any previous achievement of the sort. From the ball we pass to Covent Garden Market in the early morning, where Clarice, going homewards with the belated revellers, comes face to face with her sister, who is one of the early morning market girls. The better part of Clarice’s nature rebels against her desire for revenge, and when Dashwood forces his way into the captain’s chambers and asks for his wife it is Clarice who comes to the rescue. The ungallant captain presents his anonymous friend in her black domino, and when the domino is removed Clarice, not Mildred, stands before them. It is more than she can do, however, to prevent an estrangement of the husband and wife, but Dashwood has the satisfaction of thrashing the scoundrel Greville, in which he had the sympathy of the audience, who expressed their feeling in a round of applause when the villain went down before the fist of his opponent. The wife, however, comes back of her own accord to her erring husband just at the moment when the poor fellow, for whom life seems so hopeless, is contemplating suicide, the serenity of the scene on the terrace of the Star and Garter Hotel at Richmond contrasting effectively the conflict of emotions in the last act, which ends with the death of the hapless Clarice, who takes poison and dies as the curtain falls upon the reconciliation of the husband and wife whom she had come between. The end is unconventional; it is sad, but there was no mistaking the favourable impression it left upon the audience. Mr. Charles Glenney, who has not been seen for some time in London, plays Lord Dashwood with abundant energy, and the part of his wife is taken by Miss Evelyn Millard, in whose acting there is a genuine touch of feeling. It is a pleasure to welcome back Mrs. Patrick Campbell, whose performance of the fascinating Clarice does not belie this description, and encourages the very highest hopes for her future. Although the illness from which this gifted actress has lately recovered still leaves its traces, there was in her playing that charm of sensibility which marks all her work, and in the piteous scene in which she is reconciled to her blind father the pathos of an affecting situation was very touchingly rendered. The insensate captain is represented by Mr. W. L. Abingdon, who received the compliment of being roundly hissed, the disapproval of the audience being intended, of course, for the character he represented, not for the actor. Mr. Arthur Williams, as the rascally money-lender (whose face happens to be made up in the exact likeness of a well-known member of the Victoria Club) is humorous in his own way; and Mr. Welton Dale, Mr. G. W. Cockburn, Mr. T. B. Thalberg and Mr. John Le Hay figure in a cast that is as long as it is strong, and as strong as it is long. The success of the play was never for an instant in doubt. The rousing cheers with which the actors were called before the curtain at the end of the first act were repeated again and again during the evening, and when the play was over the authors appeared hand-in-hand before the curtain, and the actors, the stage-manager, and the managers of the theatre were all called to receive the congratulations of the audience upon an unequivocal success. ___

The Times (3 April, 1893 - p.2) ADELPHI THEATRE. This is the period of new departures on the stage, and the cherished formulas of Adelphi drama enjoy no immunity from the sacrilegious hand of the innovator. Most of the new departures resolve themselves into so many fausses sorties, the dramatist or the manager attempting an innovation, but rejecting it on finding that it fails to enlist the support of the public. Such was the recent diversion made at the Adelphi in the direction of the historic drama. In The Black Domino, which was produced on Saturday night, Messrs. Sims and Buchanan revert to the dramatic methods of the Buckstone period, and, judging from the frenzied applause bestowed upon their efforts by the public, to whom they more especially appeal, their boldness has met with its reward. The immaculate hero, who is the soul of honour, the champion of the bon motif, and who remains true to his matrimonial ideal through good and evil report, has not had a remarkably long career on the boards. Having Mr. Sims and Mr. Henry Pettitt as his sponsors he dates back ten or 12 years at the most. But, during his reign, the supremacy of this somewhat oppressive type of goodness has been undisputed. At each successive appearance he has been, if possible, more immaculate than before. His personality has been idealized in the same ratio as the villainy of his detractors and enemies in the play has been made more pronounced. But there are dangers besetting the career of this more than human character as grave as those encountered by Aristides the Just, and it is doubtless to a perception of these by Messrs. Sims and Buchanan that we owe the radical change of treatment adopted in The Black Domino, where the hero’s weaknesses of character are brought down almost to the level of criminality. After all the truest dramatic effects are evolved not from the greatness, but from the littleness of human nature. Old Adelphi playgoers remember with something like affection Buckstone’s Green Bushes, which was one of the great successes of Madame Celeste. Connor O’Kennedy was by no means the ideal hero of these later times. But his sins and the suffering they entailed served only to endear him to the public, whose eyes were wet with tears for the sorrows of his devoted and betrayed wife and her unwitting rival Miami. Exiled from home, the Irish patriot contracted new bonds in the far off valley of the Mississippi, and his expiation came when the two women he had wronged met face to face. Connor O’Kennedy’s fault lay in his allowing himself to drift. In The Black Domino, Lord Dashwood does more than this. He not only neglects to be off with the old love before he is on with the new; he weakly continues with both, forges his father’s name in order to comply with the demands of his mistress for money, and would in the end hopelessly fall between his two stools if by a somewhat daring coup de théâtre the authors did not suddenly cause the siren to reform and die the death of the conventional adventuress by means of a dose of poison on no less familiar a spot than the terrace of the Star and Garter at Richmond. But the saving clause in Lord Dashwood’s character is that at bottom he has no vicious intent; his heart is always in the right place, and when at last the cloud is lifted from his life and from that of his bride, the innocent victim of her husband’s irresolution, and of the wiles of his best friend, the demands of poetic justice are satisfied. ___

St. James’s Gazette (3 April, 1893 - p.5) THE THEATRES. “THE BLACK DOMINO” AT THE ADELPHI. “THE world’s mine oyster,” quoth Pistol, “which I with sword will open.” “London,” one can imagine Messrs. George R. Sims and Robert Buchanan saying in like manner, “is our garden in which together we will delve.” Thereafter, having completed their self-appointed task, they hie them to the Adelphi, there to display the fruits of their honest toil. They know, none better, that just as Terence, being a man, claimed to stand in touch with all things human, so are the tastes and interests of all good Londoners centred in the every-day life and work of the great metropolis. Curious as it may appear, the public never seems to tire of seeing the commonplace objects of its own existence placed upon the stage. The proverbial rule is in this instance reversed, and, instead of contempt, familiarity breeds only hearty admiration. It is upon their knowledge of this truth that the authors of “The Black Domino” have relied in evolving the scheme of their new play, which on Saturday evening was received at the Adelphi Theatre with salvoes of applause and every token of success. “They know their world,” as the French say, for they have felt the pulse of an Adelphi audience too frequently not to understand thoroughly what will give to it an added impulse and stir its heart to quicker action. And if, in seeking to achieve this result, Messrs. Sims and Buchanan have been content to draw only in the slightest degree upon either their powers of originality or their imagination, who shall blame them? “The drama’s laws the drama’s patrons give;” nor are the predilections of a popular audience to be decried simply because others take a keener delight in the subtlety of a Maeterlinck or the psychology of an Ibsen. |

|

|

“The Black Domino” is melodrama pure and simple, and to be regarded from that standpoint alone. Those who take no pleasure in the class of entertainment may be advised to leave the new play sternly alone; but to the many who love to have their feelings harrowed and their sympathy aroused by the woes of lovely woman in distress or the perfidy of peccant man, the piece will afford the liveliest pleasure. Nor is it likely that the satisfaction of these latter will be in any way lessened by the circumstance that the story unfolded by the authors presents no marked feature of novelty, and is, indeed, just a trifle thin to extend over the five acts devoted to its development. Reduced to its primitive elements it amounts merely to this. Lord Dashwood, forgetting the old adage that it is well to be off with the old love before you are on with the new, has married Mildred Vavasour without first putting an end to his liaison with a certain Clarice Berton, popularly known as Belle Hamilton. A year later Dashwood is discovered deep in debt and importuned by a rascally lawyer, Honeybun, the puppet of Captain Greville, Dashwood’s former rival for the hand of Mildred. To save himself from ruin, the hero forges his father’s name to a bill for £15,000, and then hurries off to a fancy-dress ball in order to break once and for all with the fascinating Belle. Thither he is followed by his wife, who is led to believe in the guilty purpose of her husband, and who, fainting, is carried off by Greville to his own chambers. Dashwood, apprised of the facts, speedily follows; not, however, before Belle, awakened to a better sense of things, has hurried there and changed places with Mildred, so that when the inevitable discovery occurs it is Belle and not his wife who confronts Dashwood. The situation, it may be remarked in passing, is exactly analogous to that presented by Mr. Oscar Wilde at the end of the third act in “Lady Windermere’s Fan.” Eventually, in order to save his son from dishonour, the Earl of Arlington accepts the responsibility of the forged bill, while Mildred learns the truth regarding her husband and Captain Greville from the lips of Belle Hamilton herself; who, having thus made atonement for her misdeeds, considerately takes a dose of poison, and so removes all obstacles to the uninterrupted happiness of Lord and Lady Dashwood in the future. |

|

|

From this slight sketch of the plot it may be gathered that in Lord Dashwood the authors have conceived a hero with whom it is difficult altogether to sympathize. But if his actions be base, his intentions are really unimpeachable. Unfortunately one gets just a little tired of his reiterated outbursts of self-reproach, which square so poorly with his actions. Yet so deeply imbedded in the public mind is the doctrine of hero-worship that even for so sorry a specimen of the genus as Lord Dashwood shows himself to be there is only pardon and approval. To pass, however, from the picture to its setting, nothing but praise can be given to the various beautiful and effective scenes presented in “The Black Domino.” Of these want of space prevents a detailed account; but from the first “set,” disclosing a lovely view of Ferndale Church and Park, up to the last, showing The Terrace at the Star and Garter, Richmond, with a distant glimpse of the river, all are excellent. What, however, will certainly attract the greatest attention, and probably ensure the lasting success of the piece, is the reproduction of one of Sir Augustus Harris’s Covent Garden fancy-dress balls—a triumph of realism for which Mr. Bruce Smith, the artist, is entitled to the highest praise. In the background are seen the private boxes rising tier upon tier and thronged with occupants; while the stage itself is literally covered with a moving mass of gaily dressed revellers, fantastic, quaint, elegant, and dainty. Except at the Lyceum nothing so effective, picturesque, or brilliant has been witnessed on the stage for many a day. Admirable also in its exactitude is the picture of Covent-garden Market in the early morning, with its throng of flower-girls, costers, and market-gardeners. Nor in the performance itself is any jarring note to be found; for, as far as opportunity favours, a capital all-round representation is given. Mr. Charles Glenney makes an earnest and vigorous Lord Dashwood; while Mr. A. L. Abingdon gives all necessary point to the wickedness and treachery of Captain Greville. Mr. Arthur Williams, as the rascally solicitor Honeybun, who is lured to the fancy-dress ball in the guise of an elderly Cupid, gets not a little fun out of a rather conventional part, and Mr. W. Dennis deserves a good word for his quiet and dignified rendering of the Earl of Arlington. As Belle Hamilton, Mrs. Patrick Campbell, who appears scarcely to have recovered entirely from her recent illness, again displays the greatest sensibility and power—two qualities which, combined with the charm of a singularly fascinating personality, should speedily raise her to the highest point in her profession. Miss Evelyn Millard’s portrait of Mildred is refined and sympathetic; while the younger sister Rose finds a sweet and graceful representative in Miss Bessie Hatton. Regrettably unimportant is the part of Dolly Chester, to which nevertheless Miss Clara Jecks, by her clever acting, contrives to assign a certain measure of significance. Of the remaining characters, Mr. G. W. Cockburn, Mr. Thalberg, Mr. John Le Hay, and Miss Ethel Hope deserve mention for good work done in small parts. “The Black Domino” was received throughout with enthusiasm, and, if not the best thing of its kind which the authors have given us, fully justified the hearty call which on Saturday evening brought Mr. Sims and Mr. Buchanan to the front after the final fall of the curtain. ___

The Pall Mall Gazette (3 April, 1893) “THE BLACK DOMINO” AT THE ADELPHI. THE “Black Domino” is, as far as can be decided by the enthusiasm of a first-night audience, a success. It was received with rapture by a crowded house. There were people in that audience who laughed at the piece’s sallies of humour; there were people in that audience who wept unquestionable tears at the piece’s pathos. If the success be unquestioned, then arises the question, Was the success deserved? That question may be met in two ways. It may be met by a comparison of the play with the average dramatic work of the day. It may be met by consideration of the aim of the piece, and of how far it succeeds in accomplishing that aim. Tested by either standard “The Black Domino” might safely be pronounced a masterpiece. A hurried survey of the drama of the day in London will show the student nothing that is very much better conceived, nothing that is very much better written, nothing that is much truer to life, more original in characterization, or more fertile in incident. What marvel, therefore, if, in the dearth of fame, “The Black Domino” should be saluted with all the honours! But there is the other test that we have suggested, and “The Black Domino” meets that test defiantly. If to be excellently fashioned for a certain purpose, if to be dexterously adapted to appeal to a certain level of taste, if to gain the major quantity of applause with the minor quantity of exertion be the qualifications for a masterpiece, then undoubtedly “The Black Domino” is a masterpiece. Why should its authors have been at any greater pains than was absolutely necessary to reap the ready laurel? Given a public that only asks for the familiar figures, for the familiar situations, for the familiar sentiments, and for the familiar jokes, what better thing can you do, if you are at once philanthropists, men of business, and men of the world, than to glut them with the familiar figures, the familiar situations, the familiar sentiments, and the familiar humour? If the elements that make for success in “The Black Domino” are as old as the everlasting hills, if its puppets are all made in the moulds of a venerable conventionality, if the events are the familiar events of aeons of melodrama, what does it matter? The more familiar the material the better those for whom it is intended will be pleased, and the less reason why two men of ability should bother themselves to make any departure from the old methods. But the conditions which make the success of a play like “The Black Domino” possible make the observer understand why a critic like Barbey d’Aurevilly, who hated the stage with all his heart, could maintain that the drama was the lowest form of art, the lowest form of literary expression. The sense aches to think of the admiration that was given to “The Black Domino” on Saturday night, and the kind of work that had to be done to win that admiration. Criticism, of course, retires in a graceful despair before it. It has nothing to do with criticism; it does not appeal to criticism. Nothing is changed; there is only one melodrama the more. And what is true of the play is true also of the acting. There is nothing whatever to be said about it of any serious kind. It was as good on the part of a large company as the conditions of the piece permitted. Nobody, either man or woman, was conspicuous for merits or for defects. It was an honest all-round interpretation of a melodrama which repeated, with audacity but with wisdom, all the old devices of what has come to be known as Adelphi melodrama. It was Adelphi melodrama from the Pink Wedding, with which the piece begins, to the moment when the beautiful Clarice—the evil-hearted Clarice—takes poison and dies on the terrace of the Star and Garter at Richmond, with a callous disregard for the feelings of the proprietor of that hostelry which puts the crown on her career of sin. It was, in its way, a sermon, with this for its text: “There’s nothing new, there’s nothing true, and it doesn’t signify.” ___

The Daily News (3 April, 1893) THE THEATRES. REOPENING OF THE ADELPHI. The curious process of moral deterioration which has been observed of late in our heroes of romantic drama must be assumed to have reached its culminating point in Messrs. Sims and Buchanan’s new play at the Adelphi. Mr. Jones’s Duke of Guisebury corrupted a Quaker girl; the Reverend Mr. Llewelyn in “Judah” deliberately swore to the truth of what he knew to be falsety, and audiences at the Opera Comique are just now brought face to face with a hero who expects them to overlook the little weakness that induced him to steal his employer’s valuable securities; but all these are really respectable persons in comparison with Lord Dashwood, the hero and central figure of “The Black Domino.” This heir to the title and estates of the venerable Earl of Arlington decoys from her rustic home an organist’s eldest daughter, and when he is tired of her goes down to marry a rich lady in the very church in which the organist officiates. As a married man Lord Dashwood’s conduct is even less exemplary. He neglects his wife, frequents the society of disorderly companions, and foolishly permits himself to be influenced by evil counsellors, even to the extent of adopting the suggestion that he shall forge his noble father’s endorsement on a bill of exchange. The fact that he appoints his late mistress Clarice Berton, alias “Belle Hamilton,” to meet him at a fancy dress ball at Covent Garden is excused on the ground that this is to be their farewell meeting, but the circumstances are sufficiently suspicious to induce Lady Dashwood, at the instigation of her husband’s false and designing friend, Captain Greville, to attend the ball in a “black domino.” When this has resulted in “a scene” Lord Dashwood, as on other occasions, meanly appeals to his late mistress to assist him. Having distressed and ruined the poor organist, together with his affectionate younger daughter Rose, brought a perilous scandal on Lady Dashwood which induces her to live apart, and very narrowly escaped prosecution for forgery, Lord Dashwood, after feasting one day with his gay acquaintances at the Star and Garter at Richmond, grows remorseful and thinks of committing suicide; but a friend who has learnt his purpose fetches the forgiving wife in time to deter him. It happens, however, that Clarice is also feasting that evening with friends at the same fashionable resort, and she, too, determines to commit suicide, but with a more fatal result, for she takes poison and expires on the terrace. Thereupon Lady Dashwood, now fearless, like Delilah, of “partners in her love,” is reunited to her weak and worthless husband, whose pecuniary circumstances have just been much improved by the victory of his horse in an important race. ___

The Morning Post (3 April, 1893 - p.6) ADELPHI THEATRE. Messrs. G. R. Sims and Robert Buchanan know exactly what is required to please an Adelphi audience, and again they have hit the mark in their new drama, “The Black Domino,” which combines all the essential elements of popularity. It has a sympathetic story with plenty of contrasts of love, hatred, revenge, and drollery. The scenery is magnificent, the acting everything that it should be, and the result was an enthusiastic verdict in its favour, and the promise of a long and successful run. To say that there is much originality in the play would be more complimentary than facts justify; but the question is, Do Adelphi audiences care for originality? There is one scene copied closely from Mr. Oscar Wilde’s very successful comedy, “Lady Windermere’s Fan,” and that was applauded most of all. The fact is, the patrons of Messrs. Gatti desire to see a play in which there is everything by turns and nothing long. A brisk and rapid succession of incidents, pleasant changes from pathos to fun, scenes of everyday London life and familiar places, animated acting, and admirable scenery—these are the essentials, and in these respects the Adelphi play is amply provided, and therefore it pleased the audience thoroughly on Saturday night, and will continue to do so for months to come. The hero is Lord Dashwood, a young gentleman who has been “sowing wild oats” by the acre. He has got deeply in debt, is in the hands of rascally lawyers, has become entangled with a notorious woman who calls herself Belle Hamilton, has backed horses to the extent of many thousands, and is generally “going the pace,” after the fashion of sundry fine young English gentlemen of the modern school. But in the height of his mad career he falls in love with a beautiful girl, Mildred Vavasour, and resolves to reform. He would probably have got into the right path but for a friend—a melodramatic Mephistopheles—Captain Greville, who has loved Mildred. Finding Lord Dashwood is his successful rival, he resolves to ruin him. He plunges the hero into greater difficulties by inducing him to forge the name of his father, the Earl of Arlington, in order to obtain advances of money, and when the wedding takes place Captain Greville acquaints Belle Hamilton, who comes to the country church bent on vengeance, but is prevented by her father, who has discovered the life she is leading. Captain Greville, thwarted at first, has other plans. He persuades Lord Dashwood to meet his abandoned mistress at the Covent Garden fancy ball, and then awakens the jealousy of the young wife, who goes in a “black domino” in order to see her husband in Belle Hamilton’s company. She is so overcome that she faints, and Captain Greville takes Lady Dashwood in an exhausted condition to his chambers. Then the scene form “Lady Windermere’s Fan” is imitated closely. Belle Hamilton, stricken with remorse, determines to prevent a scandal, and, going to Captain Greville’s chambers, changes dresses with Lady Dashwood, who passes quickly out of the room. When Lord Dashwood comes be sees only his former mistress. Meanwhile he has learned the treachery of his former friend, who still seeks his ruin. He is saved partly by an old college companion and partly by his own father, who, on being shown the bill for £15,000 with his signature forged, simply orders that it should be presented at his bank and paid, but the old college friend also advances the requisite cash to save the foolish young husband from disgrace. The difficulty only remains of making peace with Lady Dashwood. But the young wife is extremely forgiving, and when Belle Hamilton in her hearing declares that Lord Dashwood only met her at the Covent Garden fancy ball to bid her farewell for ever, and then makes her own quietus, not with “a bare bodkin,” but with a dose of poison, the erring husband is taken to his wife’s arms, and the curtain falls, the story having occupied five acts. The splendour of the stage setting surpasses everything previously achieved at the Adelphi. The picturesque country church, in the opening scene, is a triumph of stage realism. Even more elaborate is the representation of the fancy ball at Covent Garden Theatre, with its brilliant groups of figures in fantastic costumes, with the orchestra and performers in the centre of the area, its crowds of gay visitors in the boxes, and brilliant decorations. The entire stage is occupied with this remarkable scene, which “beats the record” of stage masquerade. Equally good in its way is Covent Garden Market in the early morning, with the revellers returning from the dance, while the market people are getting ready their stalls. Another effective scene is the “Star and Garter,” Richmond-hill, where the adventuress poisons herself. All these scenes were applauded with the greatest enthusiasm, the lavish expenditure of Messrs. Gatti in producing them being cordially recognised. Spirited acting all round made “The Black Domino” attractive. Mr. Charles Glenney as the hero played with his customary vigour, and made Lord Dashwood interesting in spite of his folly and extravagance. The scene in which the hero soundly thrashes Captain Greville delighted the audience as much as anything. Mr. Glenney and Mr. Abingdon, who represented the false friend admirably, did not spare themselves, but gave each other lusty blows. The final exit of the villain was not very brilliant, but that was no fault of the actor. The authors might plan a better situation without much difficulty. Mr. W. Dennis was to be praised for his judicious representation of the Earl of Arlington, and Mr. Cockburn was genuinely pathetic as the blind father of the adventuress. Mr. Welton Dale, as the college friend of the hero, was amusing. Mr. Arthur Williams revelled in the peculiarities of Joshua Honeybun, a solicitor, who cheats his clients with a smiling face and an affectation of idyllic simplicity. His appearance as Cupid at the fancy ball was extremely droll. Miss Evelyn Millard made a graceful heroine, not very forcible considering how badly Lady Dashwood is treated, but Miss Millard was always pleasing. Mrs. Patrick Campbell was seen to great advantage as the discarded mistress. She displayed as much ability as good taste in her rendering of this difficult character, and looked handsome and picturesque in her Cleopatra costume at the ball. Miss Bessie Hatton played with acceptance as the sister of the adventuress, and Miss Clara Jecks, although in a small part, made it amusing and effective. Hearty compliments were paid at the close to the authors and to all who took part in the performance. Messrs. Gatti may be congratulated on their Easter production. ___

Glasgow Herald (3 April, 1893) MUSIC AND THE DRAMA. (FROM OUR OWN CORRESPONDENT.) London, Sunday Night. In “The Black Domino,” which was successfully produced at the Adelphi last night, Messrs Sims and Buchanan have to a certain extent departed from the beaten track of Adelphi melodrama. The hero this time is not the incarnation of all the virtues, but is very much a human being, behaving, indeed, in more than one situation in the play very like a scoundrel. It is, perhaps, partly for this reason that the authors have made him a lord, for the titled personage of Adelphi melodrama usually is a double-dyed villain, and the much persecuted hero a member of the working class. Lord Dashwood is about to marry Mildred Vavasour in a pretty village church, when there arrives for his discomfiture Clarice Berton, a woman whom his Lordship has ruined and deserted, and who has now become a notorious character. The ceremony, a “pink wedding,” is, however, not stopped, and Mildred becomes Lady Dashwood. It is now the business of the typical Adelphi villain, Captain Greville, aided and abetted by a Jew money-lender (a part played by Mr Arthur Williams), to destroy the domestic happiness of the young couple, for Captain Greville, of course, was an unsuccessful suitor for Lady Dashwood’s hand. As his Lordship, despite his marriage, is by no means “off with the old love,” it is the captain’s object to betray him to his wife. This leads to the marvellously realistic scene of the fancy dress ball at Covent Garden, a merrier affair than the real ball, which is occasionally rather dull, but sufficiently true to life to elicit the hearty applause of Sir Augustus Harris, who was present in the stalls. Lady Dashwood has recognised at the ball her husband in company with Clarice Berton, and in a fainting condition, still disguised in her black domino, she is taken in a cab by the Captain to his chambers. Lord Dashwood also hears that his wife has left the ball with the Captain, and as he starts in pursuit we seem likely to have again a situation similar to that in “Lady Windermere’s Fan.” The Captain has little respect for his visitor, and his advances aroused the ire of the lady, who is rescued from her perilous situation by the now repentant Clarice. Clarice, on leaving the ball, finds herself in a wonderfully realistic scene of Covent Garden Market in early morning, and there she meets her sister, a market girl, and learns that her father has been assisted by the charity of the woman whom she is endeavouring to ruin. Clarice is therefore led to the Captain’s chambers, and when the host is called for a moment form the room she assists Lady Dashwood to escape, and donning the domino awaits the arrival of the husband. We need not tell in detail how Lord Dashwood goes from bad to worse, forges his father’s name, and contemplates suicide in an extremely picturesque scene on the terrace of the Star and Garter at Richmond. It will suffice that the erring husband is eventually forgiven by his wife after he has administered a well-deserved thrashing to the captain, and that he is saved the risk of further temptation by the suicide of Clarice Berton. The last-named part is cleverly played by Mrs Patrick Campbell. Mr Abingdon was the villain, and Mr Glenny and Miss E. Millard the husband and wife. ___

The Daily Telegraph (3 April, 1893 - p.2) ADELPHI THEATRE. On Saturday evening the latest dramatic outcome of Messrs. Sims and Buchanan’s joint authorship was efficiently and successfully produced in the presence of a typical “Adelphi audience,” deeply sympathetic with virtue, vehemently resentful of vice, and prompt in paying tribute of hearty laughter to the very feeblest shadow or suggestion of a joke. To such an audience, eager to applaud every entrance and exit—even those of humble supernumeraries, impersonating village chawbacons and entrusted with half-a-dozen words in a vague provincial dialect—thrilled by each sentimental platitude, and enraptured by the mildest of old farcical “wheezes,” a drama of the class to which “The Black Domino” belongs could not fail to be acceptable. At any time throughout the past half-century it has been customary to describe these works on the playbill as “new and original,” nor has the Adelphi management broken with a hallowed, if transparent, tradition in this case. Nearly all of them, however, are constructed upon identical lines, and bear a strong family resemblance to one another. It is obviously expedient that this should be so, for they suit the taste of the millions, yield golden harvests to theatrical lessees, and furnish young actors and actresses with abundant opportunities of achieving popularity. The question of art, save in relation to scenery and appointments, is not touched by these pieces. Their raison d’être is to afford amusement to multitudes of playgoers, and as a rule they fulfil their purpose effectively enough. Most assuredly no product of real genius, teeming with true wit and pathos, and fully justifying its description as “new and original,” could have aspired tot a more enthusiastic reception than that accorded to “The Black Domino” on Easter Eve. ___

The Era (8 April, 1893 - p.8) THE LONDON THEATRES. THE ADELPHI. Lord Dashwood ... Mr CHARLES GLENNEY The Black Domino is, in the matter of art and ethics, no worse and no better than its predecessors; in the matter of construction it is better than some pieces that have been given to the stage by its authors; but in the important point of interest it is hardly so strong as could be desired. We confess to a misgiving, not so much in connection with the new piece as with a tendency which it illustrates. There seems to us some danger that, in the endeavour to be unconventional, authors of melodrama may carry things too far in the direction of degrading the hero. Lord Dashwood in The Black Domino is a pitiful creature indeed. To use a common expression, he is “as soft as butter.” He has believed, at one time so much as to think of marrying her, in the notorious Belle Hamilton; and, when disillusioned, he finds great difficulty in shaking himself free. He gambles and gets deeply in debt, and he is firmly convinced of the friendship of that complete scamp Captain Greville. It is the old, old story, Greville has loved Mildred Vavasour, a rich heiress, but she has preferred the weak-kneed but amiable Dashwood. Greville and Belle Hamilton are, therefore, natural allies. It was a great pity that Dashwood did not have a definite understanding with Belle, instead of slipping away from her to get married at the little country church which makes so pretty a background for the wedding party—the men in their scarlet hunting coats—in the first act of The Black Domino. For Belle finds out about the marriage, and comes down to Ferndale with the intention of making things unpleasant for Dashwood. However, he and Mildred are married; Belle cannot alter that, but she nevertheless determines to have her say; and the audience naturally expect “a scene;” but old Pierre Berton, the organist of the church, recognises in Belle his long lost and depraved daughter Clarice; and, by a vigorous denunciation, awes her into silence. ___

The Penny Illustrated Paper (8 April, 1893) |

|

|

“The Black Domino.” THE Adelphi has in the new five-act drama of “The Black Domino” a play admirably suited to the tastes of this playhouse, the chief metropolitan home of melodrama. The authors, MM. George R. Sims and Robert Buchanan, have devised expressly for the Adelphians a series of moving situations and strongly contrasted characters; and the enterprising managers, Mr. A. and Mr. S. Gatti, have evidently given that accomplished scenic artist, Mr. Bruce Smith, carte blanche to embellish “The Black Domino” in the richest manner possible. The result is a succession of impressive tableaux exceptionally attractive, riveting the attention from start to finish, the most brilliant scene being the wonderfully realistic representation of a Fancy-Dress Ball at Covent Garden Opera House. This is a veritable triumph. Here we have an orchestra and private boxes built up on the stage, and gay pleasure-seekers gazing from these substantial boxes at the kaleidoscopic crowd dancing below—a gorgeous medley of costumes and a crowning managerial achievement that drew forth volleys of applause. Sir Augustus Harris and Mr. F. Latham were among those in front who testified most heartily to the success of this bal masqué, and of its complete triumph no possible doubt whatever could have been entertained when the curtain fell upon Lord Dashwood’s recognition of his wife in the “Black Domino,” and upon the villanous Captain Greville’s carrying off of the senseless form of Lady Dashwood. The chief interest centres in the illicit passion of Captain Greville for Lady Dashwood. It is this designing captain who manœuvres to frustrate Lord Dashwood’s marriage by drawing to the church on the wedding morning a knavish solicitor to whom his Lordship is heavily in debt, and also the lord’s cast-off mistress, Clarice Berton. Clarice is the elder and runaway daughter of the old French organist, Pierre Berton; and it is only the main force of her horror-stricken father that prevent the deserted woman from exposing the dissolute doings of her seducer before his bride. Apart from this sensational occurrence, the scene of this “Pink Wedding,” with bride and bridegroom passing through the avenue of hunting-men in pink, makes a very pretty opening picture. I don’t think it would be quite fair to the dramatists to explain by what ingenious expedient Clarice Berton saves the fair name of Lady Dashwood, or how she reunites the estranged lord and lady in the end. Suffice it to say, on this point, that the “soiled dove” who goes by the name of “Belle Hamilton” eventually dies by poison administered by her own hand, in a beautifully picturesque scene disclosing a lovely vista of the Thames at Richmond as viewed from the Star and Garter Hotel. Not less vivid than the fancy-dress ball is the elaborate set scene of Covent Garden Market in the morning, with the carnival revellers hieing home, and with Clarice’s discovery of her sister Rose in a florist’s assistant. This leads to the most sympathetic scene of all. It takes place in the garret of poor blind Pierre Berton; opening with the gift of a hamper, brought by light-hearted Chevenix Chase and Dolly Chester, and closing with Pierre’s reconciliation with his lost daughter Clarice and with little Rose’s surrender of her heart to her devoted lover. Infinitely touching is this exquisitely conceived and well-represented garret scene, admirably acted by Mr. G. W. Cockburn as Pierre Berton and by Miss Bessie Hatton and Mrs. Patrick Campbell as his daughters Rose and Clarice, and by piquante Miss Clara Jecks and Mr. Walton Dale as the music-hall star and her admirer. Miss Evelyn Millard, too, deserved praise for her embodiment of Lady Dashwood, while the earnest, buoyant style of Mr. Charles Glenney made the character of Lord Dashwood appear less despicable than it really was. Mr. W. L. Abingdon made a characteristically cool villain as Captain Greville. As the knavish, pleasure-loving solicitor, Joshua Honeybun, Mr. Arthur Williams caused much laughter; and Mr. John Le Hay, in the small part of Major O’Flaherty, added to the liveliness of “The Black Domino.” Actors and actresses, Mr. Sims and Mr. Buchanan, Mr. Bruce Smith, and Mr. Stefano Gatti well deserved the calls they obtained. It should be added that, as indicated in the drawing by a P.I.P Artist, “The Black Domino” was produced at the Adelphi under the personal direction of Mr. Sims and Mr. Buchanan, who were doubtless duly thankful to Mr. E. B. Norman, the stage manager, for the easy working of their elaborately mounted and brilliantly successful piece. |

|

|

[Click the pictures for a larger image.] ___

The Graphic (8 April, 1893) Easter Pieces BY W. MOY THOMAS “THE BLACK DOMINO” THE story of the new romantic drama at the ADELPHI fails to satisfy the claims of what is known as “poetical justice”; for it leaves the persistent wrongdoer in possession of rich rewards, while it brings his victim to a cruel and untimely end. All this, however, is strictly consonant with the cynical tone which has come over the Drama—it is to be hoped only temporarily—in these latter days. That Easter holiday audiences—as a rule a good-natured and a well-disposed race—have felt any special pleasure in the contemplation of the heartless profligacy and meanness of Messrs. Sims and Buchanan’s hero, or would have been less gratified if Lord Dashwood had been fashioned after such models as Harold Armytage and David Kingsley, no one can, with any degree of confidence, affirm. What is certain is that The Black Domino won great favour from a first-night audience, and appears to be in a fair way to rank among the successes of this popular house. ___

Black and White (8 April, 1893) THE DRAMA. “THE BLACK DOMINO.”—“THE BABBLE SHOP.”—“UNCLE JOHN.” THE unconscious humour in which Adelphi melodrama seldom fails to abound is not lacking in the latest specimen of the class, The Black Domino, by Messrs. G. R. Sims and Robert Buchanan. Its hero—if that name be applicable to a lordling who forges to pay his debts, and returns to his old mistress a few months after marriage—has a quaint fancy for transacting the most private affairs in the most public places. When he wants to arrange a parting interview with his mistress, he chooses for that purpose a fancy dress ball at Covent Garden; and when matters have come to such a pass with him that there is nothing left but suicide, he elects to shoot himself on the terrace of the “Star and Garter” at Richmond, in full view of the champagne-drinking crowd. That his attempt at suicide should be frustrated by his forgiving wife seems to me a pity, for a more contemptible cad never paced the melodramatic stage. But by administering a thrashing to a less empty-headed rogue than himself, he redeems his character in the eyes of the Adelphi gallery, which, apparently, will forgive anything for the sake of an exhibition of physical force. Fortunately, the play is not (and, doubtless the authors will say, does not pretend to be) in the least like life, in that the queer morality of some of its “sympathetic” personages is, as—Mr. Toots would say, of no consequence. It is only in the scenery that strict realism is attempted, and the pictures of the Terrace at Richmond, of Covent Garden Market, and (for aught I know) of one of Sir Augustus Harris’s Fancy Dress Balls are triumphs in that kind. Not a bit realistic (though like enough to please dwellers in cities) is the scene of the pink wedding at a little country church, with its gentlemen in ill-fitting scarlet (obviously on their way to the Fancy Dress Ball), and its rustics in costumes as extinct or imaginary as those of Watteau’s be-ribboned Arcadians. When, by the way, is the theatre going to give us the real costume of the country? You may travel fifty miles from town and not see a single smock-frock, while even sun-bonnets are becoming rare. The fact is ’Arry and ’Arriet in our villages dress very much like their cousins in town, and follow the same courses. Passing over a remote village-green the other day, many miles from a railway station, I found the urchins of the place yelling “The Man that broke the Bank at Monte Carlo”—but this is a digression. The cast at the Adelphi is long and fairly strong. Mr. Charles Glenney as the pitiful hero, Mr. W. L. Abingdon as his perfidious friend, and Mr. Arthur Williams as a low-comedy money-lender, all work with a will, while both the principal ladies, Mrs. Patrick Campbell (willowy and languorous, à la Sarah Bernhardt) and Miss Evelyn Millard, are exceeding fair to look upon. ___

The Bristol Mercury and Daily Post (8 April, 1893) Mr G. R. Sims has not been admiring Ibsen for nothing. The new play, “The Black Domino,” by him and Mr Robert Buchanan, produced on Saturday night by Messrs Gatti, instead of the ideal Adelphi hero has one who is not only a rogue, but a mean one to boot. The scenes are as pretty a series as have ever been seen at the theatre, and go far to blind the audience to the moral shortcomings of the hero. The first act is devoted to the wedding of Lord Dashwood (Mr Charles Glenney), which takes place in a moss-grown country church, attended by a gay party of red-coated huntsmen and by a throng of picturesque rustics. To the ceremony comes Belle Hamilton (Mrs Patrick Campbell), the revengeful mistress, bent upon insulting the bride; and here, also, is to be seen her aged father, a French musician, Pierre Berton, who, learning her true character for the first time, formally disowns her in order to lean upon the love of his younger daughter Rose, who, with himself, has been the grateful recipient of the bride’s bounties. Thanks to her father’s interposition, Belle is restrained from strong measures, but her revenge only takes the subtler form of drawing away the bridegroom from his allegiance, in which task she is assisted by Lord Dashwood’s best friend, Captain Greville (Mr W. L. Abingdon)—the sinister captain of convention. In the second act, which opens in Lord Dashwood’s house in town, the evil influences foreshadowed are in full swing. The young wife is being neglected, and Lord Dashwood is pretty deeply involved with Belle Hamilton, much against the dictates of his better nature. For purposes of his own, Captain Greville whispers the truth to Lady Dashwood (Miss Evelyn Millward) and informs her that her husband has an appointment with his mistress at the fancy dress ball at Covent Garden. As it happens, Lord Dashwood has only made this appointment with a view to breaking with his mistress for good, and the oddity of his plan to this end is to be explained, of course, by the dramatist’s necessities. The spectator is next conducted to the interior of Covent Garden Theatre, where a realistic representation of a fancy dress ball is give. In order to learn the truth, Lady Dashwood comes to the ball in the disguise which gives the play its title. The sight of her husband along with her worthless rival is too much for her nerves; she faints, and is promptly carried off to his chambers by Capt. Greville, whose object is to compromise her hopelessly. After the ball the roysterers make their way through Covent Garden Market, which, with its bustle, forms the next stage in the story. Here, again, dramatic as well as spectacular ends are served, as we make acquaintance with the honest Rose Berton, as a flower girl, who tells her disreputable sister, Belle Hamilton, of the benefits conferred upon their family by Lady Dashwood, and thus paves the way for the siren’s reformation. Belle Hamilton, having learnt that Lady Dashwood has been carried in an unconscious state to Captain Greville’s rooms, resolves to rescue her from this villain’s clutches. By this time Lord Dashwood, too, knows of his wife’s presence in Captain Greville’s rooms, but Belle Hamilton gets there before him, and by a trick of substitution, which Mr Sims originally employed with much effect in “The Lights of London,” the one woman takes the place of the other, Lady Dashwood escaping in her rival’s domino at the moment when her husband furiously invades the premises in search of her. Lord Dashwood does find a woman in his friend’s rooms, but to his surprise, no less than to the Captain’s, when her disguise is removed, it proves to be Belle Hamilton. In the fourth and fifth acts, Lord Dashwood’s monetary and conjugal difficulties are smoothed over. Something like a cordial understanding is even established between Lady Dashwood and the repentant courtesan, and the latter completes her self sacrifice by swallowing a dose of poison at one of her fast dinner parties on the terrace of the Star and Garter at Richmond. The hero has contemplated a similar immolation, but repented of it. ___

The Referee (9 April, 1893 - p.3) The Prince of Wales during the week has been to the Adelphi and the Empire. The Brothers Gatti and George Edwardes, I understand, have been trying to draw him as to which visit he enjoyed the more, but up to now H.R.H. has given warm approval to “The Black Domino” and “Round the Town” without expressing a preference for either. Diplomacy of this sort saves a lot of trouble. ___

The Theatre (1 May, 1893) “THE BLACK DOMINO.” A new and original drama, in five acts, by G. R. SIMS and ROBERT BUCHANAN. |

|

|

|

Lord Dashwood has studied what George Meredith calls “The Wild Oats Theory” to advantage. He has played prodigal son, and eaten the husks, and now intends settling down with loving Mildred Vavasour to one long course of fatted calf. One oat, however springs, full-blown from the earth, clad in sumptuous raiment, on his wedding morning. She is Clarice (alias Belle Hamilton) the seeming virtuous daughter of the French village organist. Despite this fact she would make a scene and proclaim Dashwood the libertine he is, but her father learns her secret, restrains her, and the wedded pair complete their triumphal march beneath the uplifted hunting crops of gentlemen in pink. Staid married life soon satisfies Dashwood, for in act ii. he is playing Samson to Belle’s languorous Delilah. The liaison has plunged him into debt, and the only way out according to Captain Greville, his friend (and Mildred’s rejected lover), is by forging his father’s name, which he obligingly consents to do. He determines once more, however, to be off with the old love, and decides to do it in the presence of witnesses, in fact at a Covent Garden fancy-dress ball. Thither Mildred, primed by Greville, follows him, to gather sufficient evidence to satisfy a jealous wife, to fall insensible, and be conveyed by Greville to his rooms. Meantime Clarice encounters her stolen sister acting as flower-girl in the market, learns that Mildred has been Lady Bountiful to this child and her now blind father, and hastens to the rescue. Arrived at Greville’s rooms she changes cloaks with the heroine, and when Dashwood comes to reproach Greville for his perfidy, shields her much as Mrs. Erlynne shielded Lady Windermere, or the showman the convict-hero of “The Lights o’ London.” Greville is now unmasked and receives a sound thrashing at the hands of Dashwood, who determines to suicide in the final scene—a lovely set of the Thames Valley as seen from the Star and Garter. But Belladonna Clarice is set upon the same end, clears him in the hearing of his forgiving wife, and takes morphia and dies—the forged bill trouble being concluded by the felonious purchase of the document by a wealthy friend. The acting was of the order known as popular. Mr. Abingdon as the villain was duly suave, cool, sinister. The comic money-lender of Mr. Arthur Williams was a playful usurer. The contemptible hero found salvation only through the vigour with which Mr. Glenny administered a drubbing to his quondam friend. Miss Hatton and Mr. Thalberg were the staunch, serious lovers. Mr. Dale and Miss Jecks, pitiably wasted upon a wretched part, the nagging comic ones. Mr. Cockburn as the blind organist was constrained to an over liberal use of the pathetic stop. Miss Millard had only to look pretty and winning. And Mrs. Campbell’s sensitive talent was employed upon Clarice. Upon her the interest centred, though the character was vaguely drawn. The method of the actress compelled attention, extorted admiration, and set one marvelling why the clever authors deliberately withheld from such an artist a study worthy of her quite exceptional powers. ___

Also in the May, 1893 issue of The Theatre, ‘The Black Domino’ was spoofed in the section entitled ‘Condensed Dramas’. I’ve placed this on a separate page: Condensed Dramas - The Black Domino ___

The Referee (7 May, 1893 - p.3) Next Saturday evening Miss Olga Brandon will return to the Adelphi, where she will play the part of Clarice Berton in “The Black Domino.” Miss Brandon will be agreeably remembered by Adelphi patrons as the leading lady there during the run of “The English Rose.” To-night (Saturday) the Duke and Duchess of Connaught and the Prince and Princess Louis of Battenberg witnessed the performance of “The Black Domino.” ___

The Referee (14 May, 1893 - p.3) There was an important change in the cast of “The Black Domino” this (Saturday) evening, Miss Olga Brandon, who is no stranger at the Adelphi, appearing as the fascinating Belle Hamilton. If anybody can play the siren, it is the ox-eyed Olga, and her acting produced an electric effect upon the audience, who applauded her vigorously, even when they must have felt the least sympathy with the wicked young person she represented. The funny men of the piece came in for their full share of applause in the excruciatingly comic scene before the Fancy Dress Ball; and Mr. Scenery, too, was cheered to the echo when the curtain fell upon the magnificent picture, as large as life and twice as gay, of the Fancy Dress Ball at Covent Garden. ___

The Era (20 May, 1893 - p.11) “THE BLACK DOMINO.” Since its production at the Adelphi Theatre, on April 1st last, the cast of Messrs Sims and Buchanan’s drama has been greatly strengthened by several alterations in, and additions to, the company. The most important is the substitution for Mrs Patrick Campbell of ___

The Derby Daily Telegraph (20 May, 1893 - p.2) The curious transitional stage through which things theatrical have been passing lately has entered on another development. The good old type of Adelphi melodrama is not the philosopher’s stone it once was. The latest Adelphi production “The Black Domino” by those enormously successful dramatists, George R. Sims and Robert Buchanan, will be withdrawn shortly after a comparatively brief run. Against this we have to place the revival of what may be termed the Charles Dickens type of play as sampled in “Liberty Hall.” The generation that has grown up since the passing of the Education Act is evidently on the look round for a new style of entertainment. Melodrama, farcical comedy, and comic opera do not spell fortunes as was the case a few years ago. The changes in play-goers’ tastes are becoming very marked. The tens of thousands who patronise the music-halls declare themselves bored by current theatrical productions. ___

Glasgow Herald (26 May, 1893) THE Adelphi is the latest victim to the prevalent theatrical depression, and Messrs Sims and Buchanan’s “The Black Domino,” which was produced on April 1, will be withdrawn on Saturday night, it thus having had a run of about two months. The piece should have had an excellent chance, but the present season is an extraordinary one, and has upset the best laid plans of many managers. It is understood that the Adelphi will remain closed for a short time, but some members of the company, among them Messrs Arthur Williams and Abingdon, will be transferred to strengthen the cast in “Forbidden Fruit” at the Vaudeville. |

|

|||||

|

|||||

|

[Mrs. Patrick Campbell in The Black Domino from The Theatre (1 June, 1893)

The Theatre (1 June, 1893) MRS. PATRICK CAMPBELL (the subject of one of our portraits this month), has leapt into prominence and popularity with the suddenness of a Miss Julia Neilson or a Mr. Rider Haggard. In June, 1890, she was an amateur, playing Marie de Fontanges in “Plot and Passion,” and known to few beyond that limited circle to whom the “Anomalies” of West Norwood are more than a name. In June, 1893, she is chosen from among the leading English actresses to fill the post of honour in Mr. Alexander’s notable St. James’s company, and, higher distinction still, to play the tragic heroine by whom Mr. Pinero’s fame as a great dramatist will stand. “The Second Mrs. Tanqueray” will not, however, be Mrs. Campbell’s introduction to its author. In November, 1889, she played Millicent Boycott in “The Money Spinner,” and impelled a writer in THE THEATRE to declare that, notwithstanding his vivid remembrance of Mrs. Kendal in the part, there was much in Mrs. Campbell’s rendering to commend, “much of strenuous effort and courage and womanliness, that exercised a great influence over her audience.” Before this, Mrs. Campbell had secured a flattering local success as Alma Blake in “The Silver Shield,” to which slap-dash person, however, her subdued and gentle style hardly permitted her to give suitable expression. A matinée of “As You Like It” two years ago introduced Mrs. Campbell to the London public. She received great encouragement from the critics as a body, and lavish praise from Mr.Clement Scott, whose ardent eulogy perhaps induced Mr. Buchanan and Mr. Sims to offer the actress the leading part, Astræa, in “The Trumpet Call,” in August, 1891. Her success was instant and emphatic. Her style was acclaimed as intellectual, and a roseate future was foreshadowed for one who could in an evening wean the Adelphines to semi-sympathetic villainy. Louder praise and predictions of a yet more brilliant future, rewarded her pathetic picture of Elizabeth Cromwell in “The White Rose” in April 1892, a still longer stride to the front being taken with Tress Purvis in “The Lights of Home” in September, 1892, and the extreme value of her severely restrained style becoming once more apparent in Clarice Berton in “The Black Domino,” which part Mrs. Campbell resigns in order to test her capacity for the higher drama in “The Second Mrs. Tanqueray.” ___

The Era (31 March, 1894 - p.9) THE BRITANNIA. Lord Dashwood ... Mr W. H. PERRETTE This successful Adelphi drama was a capital selection for the Easter holidays, and its first representation at the Britannia on Saturday night was witnessed by a crowded house. During the week Hoxtonians have been afforded an opportunity of seeing for themselves what a fancy dress ball at Covent-garden Theatre is like. They have gazed with delight upon the brilliantly lighted scene and the groups of merry masqueraders, and have thus gained a knowledge of a phase of life with which they must necessarily have only a very imperfect acquaintance. The famous ball scene has been thoroughly well done, the practised skill of Mr G. B. Bigwood, the stage-manager, being again evident in every detail. other scenes worthy of mention are Covent-garden Market—an effective picture much more familiar to East-enders than the interior of the theatre—and the Star and Garter, Richmond. The acting is worthy of the mounting. A regrettable accident has temporarily deprived Mrs Lane’s establishment of the services of Mr Algernon Syms, but nevertheless a strong cast has been secured. Lord Dashwood is not by any means an immaculate hero. He is, however, more human than the young gentleman of old-fashioned melodrama, who never under any circumstances does wrong, and whose very virtues are apt to become tiresome, just as the “goody-goody” youth in the storybooks strikes the average boy as being an intolerable prig. Mr W. H. Perrette, always forcible and effective, plays this character admirably, and the audience shouts with delight when in the fourth act Lord Dashwood denounces Captain Greville, and inflicts upon him severe personal chastisement. The recipient of this unwelcome attention proves to be a false friend and an unforgiving foe, and it is a source of satisfaction to know that in the end he will be defeated and disgraced. Captain Greville’s character is powerfully delineated by Mr Jackson Hayes, a recent addition to the Britannia stock company. Mr Edward Leigh supplies a carefully considered portrait of the blind organist, Pierre Berton, the reconciliation between him and his erring daughter, Clarisse, being exceedingly touching. Mr Joseph Rowland as Joshua Honeybun must be credited with a highly diverting character sketch, the humour of which is as telling as it is unexaggerated. Mr Walter Steadman, relieved for once of the responsibilities attaching to the portrayal of villainy of the deepest dye, seems to revel in the part of Chevenix Chase, and affords abundant evidence that he possesses a keen sense of humour. Mr Barrett has had more congenial parts than that of the Earl of Arlington, but he makes the most of his opportunities. Miss Beatrice Toy as Mildred gives a sympathetic rendering of the woman whose love for the man she has married induces her to overlook his faults. Miss Oliph Webb is decidedly successful in the by no means easy part of Clarisse Berton, and Rose Berton is ably portrayed by Miss Julia Summers. Dolly Chester, young Chase’s sweetheart, has a lively representative in Miss Lalor Sheil, and Mrs M. Arnold does well as Mrs Alabaster. M r Bruce Lindley is satisfactory as Dr. Maitland, and other parts are efficiently embodied by Messrs W. S. Parkes, F. Beaumont, Dans, Dunlop, Atterton, Bowen, Gregory, Mrs Leigh, and the Misses M. and F. Kelsey. The drama is followed by the appearance of the Villion Troupe of acrobatic bicyclists and Stage-Struck, in which is introduced a new burlesque duologue entitled “The Ghost of Hamlet’s Father,” by Mr J. Addison. |

|||||

|

|

[Mrs. Patrick Campbell as Clarice Berton in the Adelphi production of The Black Domino

From My Life and Some Letters by Mrs. Patrick Campbell (Beatrice Stella Cornwallis-West) (New York: Dodd, Mead and Company, 1922 - pp. 78-85.) ‘After the matinée of As You Like It, in which I was so valiantly helped by Mrs. Percy Wyndham, I was engaged, on the advice of Mr. Clement Scott and Mr. Ben Greet, by the Messrs. Gatti to play at the Adelphi in The Trumpet Call, by Mr. George R. Sims and Mr. Robert Buchanan. — * It is characteristic of a certain side of human nature that I received more than one anonymous post-card, saying the writer was sure I had arranged the dénouement to make certain of a success. — 80 stand or see. She called a hansom cab, helped me into it, and told the man to drive to “Newcote,” my uncle’s house in Dulwich. 82 CHAPTER V. IT was necessary for me to act again as soon as possible. I was still physically feeble, white and fragile—my hair only just beginning to grow again—but I could not refuse the Messrs. Gatti when they sent for me to play the role of “Clarice Berton” in The Black Domino, at a salary of £8 a week. “May 2nd, 1893. I had met Miss Robins first at the Adelphi, where she played the leading role in The Trumpet Call with me. I delighted in her seriousness and cleverness. She was the first intellectual I had met on the stage. _____

Next: The Piper of Hamelin (1893) Back to the Bibliography or the Plays

|

|

|

|

|

|

|