|

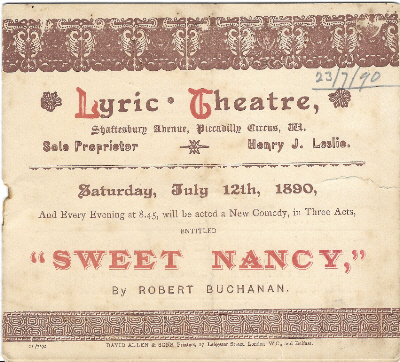

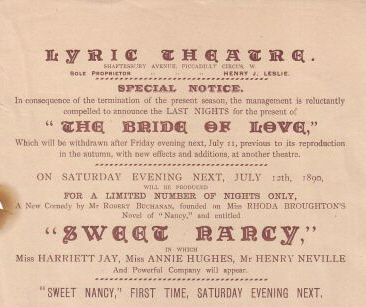

[Lyric Theatre handbill announcing the end of The Bride of Love

and the opening of Sweet Nancy on Saturday, July 12th, 1890.]

The Daily Telegraph (11 July, 1890 - p.3)

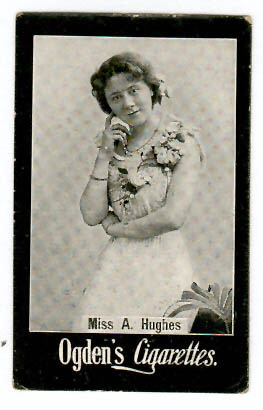

In Mr. Robert Buchanan’s new comedy, founded on Miss Rhoda Broughton’s “Nancy,” to be produced at the Lyric to-morrow, Mr. Henry Neville will be Sir Roger Tempest, the old soldier, and the sisters Barbara and Nancy Grey will be played by Miss Harriett Jay and Miss Annie Hughes. We are to see still another parson, the Rev. James Braithwaite, rector and bachelor, in the new comedietta, “An Old Maid’s Wooing,” written by Mr. Arnold Golsworthy and Mr. E. B. Norman. The clergyman will be played by one of the authors, Mr. Norman, and the old maid by Miss Ethel Hope.

___

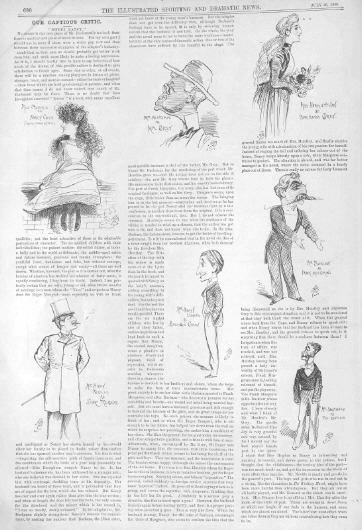

The Illustrated Sporting and Dramatic News (12 July, 1890 - p.32)

“NANCY” is one of the best of Miss Rhoda Broughton’s later novels, albeit lacking in the ill-regulated though unmistakable power which characterised her first passionate romances. It scarcely looks like the framework of a comedy or domestic drama, but Mr. Robert Buchanan thinks otherwise, and with the authoress’s permission is trying a dramatic version of her story for the last few nights of his occupation of the Lyric. Mr. Buchanan is indefatigable, and it seems to be his ambition to have one or other of his pieces occupying simultaneously every stage in London. He must take care lest, like the great Napoleon, he try to do too much and succeed in doing it.

THESE are the lines in which, after his wont, Mr. Buchanan has burst into song over the subject of his piece:

Flowers, these bright summer days,

Answer love’s glances!

Glad in the garden-ways

Bloom the “Sweet Nancies!”

Flower of the sun and dew,

Quaint, yet love laden,

Bloom in the garden, too,

Nancy, my maiden!

Roses red, lilies fair,

Others may fancy,

Fittest to pluck and wear

Is the Sweet Nancy.

But what is a Sweet Nancy? We never heard of it as in demand for button holes. For the production of the new play the company at the Lyric is reinforced by Miss Annie Hughes and Mr. Henry Neville.

___

Reynolds’s Newspaper (13 July, 1890)

LAST NIGHT’S THEATRICALS.

LYRIC THEATRE.

Mr. Robert Buchanan having withdrawn the charming play, “The Bride of Love,” replaced it last night by a new comedy, entitled “Sweet Nancy,” founded on Miss Rhoda Broughton’s famous and charming story, “Nancy.” The story, familiar to many, tells of a young girl’s sacrifice, in order to benefit her brothers and sisters—brow-beaten and bullied by their father—who enters into a May and December marriage with an elderly general, Sir Roger Tempest, and who at first, doubtful of her love for him, ends with being violently jealous of his attentions to a Mrs. Huntley, a grass widow, who had previously set her cap at him, and now ridicules Sir Roger for having a girl-wife, and marrying not only one member, but the whole family. The play is much too long, and at times verbose, but the length of the piece was everywhere condoned by the admirable acting of the excellent company engaged. There is an abundance of juvenile characters, but playgoers, having been surfeited with Fauntleroys, princes and paupers, and the like, would certainly exclaim, “Not too much juvenile, but juvenile enough.” It is here we think the play could be curtailed, inasmuch as the characters serve little or no purpose in forwarding the action of the play, though they help towards making a series of pretty stage pictures. Miss Annie Hughes, as Nancy, the tomboy girl-wife, endowed the part with a pathos, a spirit, and a charm that was quite enchanting; in fact, had the part been written purposely for her, it could not have suited her better. Mr. Henry Neville, sound actor as he is, was perfect in every way as Sir Roger Tempest; and Mr. Ernest Hendrie, as the tyrannical and somewhat parsimonious father, gave an excellent character sketch. Miss Harriet Jay, as Nancy’s sister Barbara was excellent, and Miss Ethel Hope as the mother of the tribe of paternally-awed juveniles, lent excellent service. Other characters were carefully portrayed by Mr. H. Esmond, Mr. Bucklaw, and Mr. C. M. Hallard. Miss Frances Ivor as Mrs. Huntley, not quite perfect in her part, looked charmingly, and acted excellently. The comedy was preceded by a delightful and well-written comedietta by Messrs. Arnold Golsworthy and E. B. Norman, called “An Old Maid’s Wooing,” in which the Squire and the Rector of Churton are each in love with the same woman. The former enlists the service of the parson to make known his affection, but the lady preferring the latter, the Squire, though defeated, acts honourably. Mr. E. B. Norman undertook the part of the Rev. James Braithwaite; Mr. E. Hendrie was excellent as the uneducated Squire, who made his money in hams; and Miss Ethel Hope played quietly and admirably as the Old Maid, Miss Hester Grayson. It was close on the witching hour of midnight when the entertainment terminated, when calls were given for the principal characters, to which they responded, as did also Mr. Robert Buchanan.

___

The Referee (13 July, 1890 - p.3)

LYRIC—SATURDAY NIGHT.

It is difficult to excite sympathy with the love affairs of middle-aged people, and with regard to “An Old Maid’s Wooing, by Messrs. Arnold Golsworthy and E. B. Norman, the audience is forced, despite the author, to the conclusion that the old maid and her two suitors ought to know better. The old folks have it all their own way at the Lyric now, for in “Sweet Nancy” again the heroine marries an old man, comparatively speaking, for though Sir Roger Tempest is young for “a General in the English Army,” he is old for the husband of such a slip of a thing as Nancy. Turning his attention from the old novelists to the modern school, Mr. Robert Buchanan has adapted Miss Rhoda Broughton’s popular story, “Nancy,” and he has, as usual, effected certain changes, which are not always improvements, in the plot. There is nothing very dramatic in the story as it is related in the pages of Miss Broughton, and the scenes of domestic comedy which Mr. Buchanan has translated from the novel to the stage lose a good deal of their interest when put into action. The children’s constant talk, which is so unaffectedly charming in print, becomes tiresome, and they and their low-comedy father and their enervated mother become unendurable after a while, with the single exception of the dear little imp Tou-Tou. The part of this child of ten years of age is prettily played by Miss B. Ferrar, whom it was difficult to recognise in her short skirts as the representative of the country wench of the little piece performed before “Sweet Nancy.” The part of the tomboy, Nancy, who marries Sir Roger Tempest to please her family rather than herself, is just the character to suit Miss Annie Hughes. She is more successful, however, in her wayward moments than in the emotional passages of the play, which are a severer strain upon her than upon Mr. Henry Neville, who revels in this kind of thing. Still, she comes out strong in the scene of the parting with her husband, when he is ordered off to the wars. The scene is one with which we are familiar. It is as old as Homer, to go back no further, and it has been treated on the stage with more delicacy and dramatic point by Robertson in “Caste” than by Mr. Buchanan in “Sweet Nancy.” The courtship of Nancy by her not particularly ancient warrior is delightful comedy, but when the story progresses, at a very slow rate of progress, the patience of the audience is sorely tried. Mr. Henry Neville represents Sir Roger Tempest as an intensely emotional lover, but there is really nothing in his wife’s conduct to justify his ridiculous suspicions when he comes back to her from South Africa. There is too much ado about nothing more than the simple fact that a contemptible young man, who was supposed all along to be paying his addresses to Nancy’s sister Barbara during Sir Roger Tempest’s absence, has had the audacity to declare a passion for Lady Tempest on the day of her husband’s return from abroad. This is the first inkling of an intrigue in the piece, and to make up for coming late, it is prolonged beyond reasonable limits, for Sir Roger takes a most unconscionable time coming round. To make matters incomplete, Barbara is left inconsolable after all. If we remember rightly, Barbara dies at the end of the novel. It would have been well if she had died at the beginning of the play, for it is beyond the art of Miss Harriett Jay, who makes the most of a poor chance, to render the character interesting. Slight as it is, the plot is dissipated in a weariness of words and it was nigh on midnight when the curtain fell.

___

The Daily News (14 July, 1890)

THE THEATRES.

_____

“SWEET NANCY” AT THE LYRIC

THEATRE.

Miss Rhoda Broughton’s “Nancy” has been some years before the world, but no dramatist appears to have seen in it promising material till it occurred to Mr. Buchanan the other day to take it in hand. Mr. Buchanan is, however, the most skilful of those playwrights who practice the art of transferring works of narrative fiction to the stage, and his tact and ingenuity have not forsaken him on this occasion. “Sweet Nancy,” which on Saturday evening took the place of “The Bride of Love” at the Lyric Theatre, is not without faults; but happily its faults are of a kind very easily remedied. It is not merely that the three acts are too long, though the play, beginning at the late hour of nine in the evening, detained the audience till not very far from the stroke of midnight. It is rather that the subject is too slight to bear the elaboration which Mr. Buchanan and his interpreters bestow upon it. Of pathetic or serious interest there is really none. It is a mere storm in a matrimonial teacup, which is not even brewing in anything like earnest till the play is well nigh at an end. The charm of the piece—and it is a rare charm indeed upon the modern stage—is the uncompromising truthfulness of its portraiture, and the unconstrained freshness of its dialogue. The spectators who had the misfortune on Saturday to arrive early enough to witness the performance of the little one-act play by Messrs. Goldsworthy and Norman, with its milksop parson, its painfully exemplary heroine, its imbecile squire, and its much-too-highly-coloured village poacher, could not fail to feel a welcome relief in the presence of Mr. Buchanan’s Nancy, who has at least the merit of speaking and acting like a human being, and who, with all her failings, is, in the congenial person of Miss Annie Hughes, a really delightful personage.

When Nancy confesses to her middle-aged suitor, Sir Roger Tempest, that she has no particular fancy for him, though she is glad that there will be some “good shooting for the boys,” it is instinctively felt that this mood is quite as likely to ripen into a genuine regard as if she had received his offer with more conventional phrases. When, in the later scenes, she repulses the insolent advances of her sister Barbara’s reputed admirer, and saucily tells him that he is not the sort of man to make her unmindful of her marriage vows, it is perceived in like manner that, with all her sharpness of tongue and lack of skill or desire to hide her girlish impulses, she is not a whit the less likely to make a loving and a faithful wife. Nancy is in brief the central figure and unfailing source of the interest of the story; and what defects the play presents are all due to momentary forgetfulness of this fact. The husband’s suddenly aroused fit of jealousy is really only of value for its effect in drawing out the more subtle and delicate traits in the character of the wife. Hence the efforts of Mr. Henry Neville to convert the situation into a mild variation upon the tragic relations of Othello and Desdemona were in excess of the occasion, and indeed his too fervid and emotional style was more in keeping with romantic drama than with the lighter key in which the story is pitched. The other performers of the cast were, with scarce an exception, excellent in their way. On the stage Barbara, unlike the poet’s “thing of beauty,” exhibits a decided tendency to “pass into nothingness;” but as it stands the part is filled with perfect taste and thoroughly womanly grace and tenderness by Miss Harriet Jay, while Mr. Hendrie with many sharp and clever touches brings into relief the humour of Mr. Grey’s selfish domestic despotism. An artistic sketch of the maliciously fascinating Mrs. Huntley, contributed by Miss Ivor, also deserves mention; while the spirit and cleverness of Mr. Esmond, Mr. Hallard, Mr. Highland, and Miss B. Ferrar, in their respective parts of Algernon, “Bobby,” “The Brat,” and Tow Tow, are not the less worthy of acknowledgment because the mischievous pranks and unruly utterances of this quartet are too often permitted to interrupt the more direct purpose of the play. “Sweet Nancy” will presumably undergo some compression. In that case it ought to prove one of the most popular, as it is certainly one of the freshest and most diverting, productions of the modern stage.

___

The Scotsman (14 July, 1890 - p.8)

LONDON, Saturday night — Mr Robert Buchanan has taken advantage of his brief tenancy of the Lyric Theatre to produce there a new comedy from his own pen, founded on Miss Rhoda Broughton’s novel called “Nancy,” withdrawing “The Bride of Love.” On Friday night he followed on with “Sweet Nancy” (as he calls his latest venture.) This evening there was a large audience, including Mr A. M. Palmer, the American manager; Miss Genevieve Ward, Miss Wallis, Miss Kate Santley, Mr Edward Terry, and other well-known people, and it proved very liberal in its applause, especially at the conclusion of the first and the second acts. The third act was found inordinately long, the performance not ending until close upon midnight; nevertheless very few hisses mingled with the cheers that followed the fall of the curtain, and so far the reception given to the comedy was favourable. The third act, however, will need to be relieved of much of its verbosity and repetition, and even then the play will not rank high in the list of Mr Buchanan’s productions. The subject is thin, and it is treated for the most part conventionally. The first act, which exhibits Nancy as the “tomboy” of a large family of children, and illustrates the processes by which she yields to the addresses of her middle-aged lover Sir Roger Tempest, is fresh and bright, but as soon as the illicit lover Frank Musgrave and the scheming “grass widow” Mrs Huntley come upon the scene, the interest begins to lag. Nancy gets jealous of Mrs Huntley. Her soldier husband is called to the wars, the lover whom Nancy has all along regarded as the suitor of her sister Barbara pays violent court to the former, the husband returns to find Nancy’s name linked slanderously with Musgrave’s, and after explanations too many and too long, Musgrave’s treachery is exposed, Nancy’s innocence vindicated, and Sir Roger reassured. All this is very jejune, besides being clumsily worked out, and it would not have been tolerated to-night but for the admirable acting of Miss Annie Hughes as Nancy. This clever young artist, delightfully naive in the opening scenes, showed herself capable later on not only of pretty pathos, but of genuine passion, and altogether enhanced her reputation very considerably. The sound method of Mr Henry Neville was of great service in making Sir Roger an impressive figure; Mr Hendrie was humorous as Nancy’s father, of whom, however, there is too much; and Mr Henry Esmond was effectively natural as Nancy’s brother, who is ensnared by the wiles of Mrs Huntley. Apart from these, the cast is not especially strong, for Miss Harriet Jay as Barbara is amateurish. Mr Bucklaw as Musgrave seems ill at ease, and Miss Ivor, clever in many things, is not well suited as the “grass widow.”

___

The Times (14 July, 1890 - p.4)

LYRIC THEATRE.

Mr. Robert Buchanan is not as careful of his reputation as he might be. The comedy of Sweet Nancy, which he brought out upon his own responsibility at the Lyric Theatre on Saturday night, is not in his best style. Adapted from a novel of Miss Rhoda Broughton’s of the year 1873, it bears every sign of being an early an d immature work, and exhibits none of that happy blending of the arts of the playwright and the novelist which has distinguished the author’s Sophia and Clarissa. The courtship and marriage of a sedate, elderly gentleman with a young romp of 19, who knows that he has “been to school with father,” is not an interesting subject for the stage, where there beats a fiercer light than on the pages of a novel; and when the serenity of the household is disturbed by jealousies for which there is no real foundation, and which a timely and natural word of explanation would dissipate, the spectator’s patience is apt to be a little tried. Sweet Nancy is a very small story— a mere episode, indeed—beaten out into three acts of extraordinary tenuity. Here and there it contains pleasing suggestions of truth and human nature, as in the case of the tyrannical father who is followed about by a brow-beaten wife and a troop of insufferable children of all ages from 12 upwards; but, as often happens in a piece which has been derived from a book, the odds and ends of character put forward are somewhat inconsequent; they look for the most part what they are, the mere débris of a novel rather than the living material of a play. Mr. Henry Neville acts the middle-aged lover, and Miss Annie Hughes the hoyden of 19 in a pinafore. The choleric paterfamilias finds a very plausible representative in Mr. Hendrie. In an incidental part appears Miss Harriett Jay. Oddly enough, a new first piece, entitled An Old Maid’s Wooing, also deals with the unsympathetic subject of an elderly courtship.

___

St. James’s Gazette (14 July, 1890 - p.6-7)

A SCHOOL-ROOM COMEDY.

It is, as was to be expected, an odd sort of play that Mr. Robert Buchanan has fashioned out of Miss Rhoda Broughton’s novel “Nancy;” and it is an adaptation which, save in one important particular, hardly catches or reproduces the characteristic spirit of its original. Most of Miss Broughton’s romances have their dramatic moments; but none of them that we can call to mind is dramatic as a whole—“Nancy” even less than the rest. “Nancy” is not nearly so strong a story as “Red as a Rose is She” or “Cometh Up as a Flower,” and it depends for its effectiveness largely upon the commonplace realism of its sketches of an unconventional but not particularly interesting home-circle—comprising, as is usual with this novelist, a very objectionable father, a subdued mother, a beauty, a tomboy, and a horde of more or less rebellious younger children much given to rough badinage and practical jokes. The household does not strike the reader as a pleasant one to live in, though the sprightly sayings and doings of the lively young people cause much the same kind of merriment as that aroused by the graceless remarks of the Rude Boy in Lieutenant Cole’s ventriloquial entertainment. It is all fresh and funny enough for a little time; but after a while the unsophisticated humours of the school-room begin to pall when they are transferred to the stage. When the young Greys have got their sister Nancy on the top of the garden wall, and have taken away the ladder on the approach of the girl’s elderly admirer, they have really done all that is needed of them behind the footlights; and although the Brat and Tow Tow and the rest all have competent representatives, they are soon felt to be dramatic superfluities.

The fact is, that the more lifelike such creations are the more irritating they become: they begin by causing roars of laughter, and end by distressing the nerves of the spectator. Happily, however, Nancy herself—whether Nancy the romp or Nancy the child-wife of General Sir Roger Tempest—is a delightful creature, and is delightfully embodied by Miss Annie Hughes; who, we are glad to see, has soon given up her intention of leaving the stage. We cannot profess to take much interest in the thin and perfunctory plot concerning Nancy’s baseless jealousy of the fast grass-widow and Nancy’s compromising association with Frank Musgrave, the faithless lover whom she desires to bring to her sister Barbara’s feet. There is scarcely dramatic material in it all for a short single act of alternate misapprehension and éclaircissement, much less for the three exceptionally long acts of which Mr. Buchanan’s play consists. But Nancy’s own share in the intrigue, such as it is, throws so vivid a light on her winning character, her loveable frankness and naïveté, her childish impulsiveness and simplicity, and, above all, the sincere unselfishness of her affectionate nature, that the faulty construction and the redundant conversation are forgotten or forgiven, at any rate so long as Miss Hughes is on the stage. It is not often that any young actress has been fortunate enough to find a part so exactly made to her measure, and it is rarer still to see such an opportunity employed to such perfect advantage. Bright and light in her earlier scenes, Miss Hughes fully rises to the more ambitious occasion presented in the passages of strong emotion which come later on; and though she cannot render plausible Nancy’s unaccountable delay in proclaiming her innocence before her husband, she can at least win the fullest possible sympathy for the girl’s open-eyed distress. Mr. Henry Neville, too, deserves high praise for the dignity and tact with which he handles the manly but not very romantic role of the middle-aged husband whose girl-bride has married him chiefly for the sake of the benefits which she expects him to confer upon her brothers and sisters. The popular success, indeed, which these two players scored on Saturday night may well suggest to Mr. Buchanan the advisability of strengthening and abbreviating a comedy which was felt even by the most indulgent of audiences to be alike weak and diffuse. With this view, the characters of Barbara Grey and her disloyal suitor, Frank Musgrave, might well be so elaborated as to gain a little more individuality, whilst the juvenile chorus might still more usefully be reduced in its dimensions. As the play stands, Miss Harriett Jay and Mr. Bucklaw really have no chance of imparting vitality to the subordinate love interest, though they both do their best with their shadowy opportunities. Miss F. Ivor, again, has an uphill task in filling out the hazy outlines of the grass-widow’s conventional malice; but she is more successful than is Mr. Hendrie in his effort to realize the cross-grained humours of Miss Broughton’s typical paterfamilias Mr. Grey. A word should, in conclusion, be said for the youthful freshness given by Miss B. Ferrar to her impersonation of the troublesome twelve-year-old nicknamed Tow Tow, whom she makes much less offensive than the average specimen of long-legged short-skirted girlhood upon the stage. Upon the whole the reception of “Sweet Nancy” on Saturday evening was decidedly encouraging; though somewhere about midnight there were heard sounds which suggested that even the most child-loving of audiences may have too much of school-room comedy.

___

The Daily Telegraph (14 July, 1890 - p.5)

LYRIC.

In the old school editions of classical poets, such as Virgil, Ovid, and Horace, there was appended to the verse text a marginal prose rendering called an “interpretatio.” We ought to need no such assistance from a dramatist who turns a novel into a play. In fact, we ought not to be concerned with Miss Rhoda Broughton’s novel of “Nancy” at all when we sit down to see Mr. Robert Buchanan’s “Sweet Nancy.” It may be, as he says, a very “famous story,” and doubtless it is perfectly true that the authoress has created a very “sweet character;” but there ought to be no necessity to pay a visit to a circulating library before understanding a play or estimating a character. The difficulty of Mr. Buchanan’s task is obvious from his workmanship. He has been hampered with too much incident and detail, the pride of the novelist, the worry of the dramatist. He has been far too loyal to the authoress, and has not had the courage to cut away. The play is only in three acts, but the last one has material for two, and should be so reconstructed at once to the immediate advantage of the story. An English officer, just returned from a campaign at the Cape to the arms of his adored little “child wife,” does not after a hurried embrace rush off to give a message to the wife of a comrade, who lives hard by, and immediately enter into a family court-martial that must last several hours without breaking bread or tasting food. No; in this case the curtain should fall on the arrival of General Sir Roger Tempest from the wars. The court-martial on his baby bride may well occupy a dramatic chapter all to itself.

The character of Nancy is certainly not convincing in the stage version of the story, and it may be doubted if this contradictory little person is, after all, very interesting. She becomes a Frou-Frou without her singular charm, and a Dora without the excuse of her feeble amiability and her inexperience. We can understand Nancy fairly well under her irritating old father’s roof in the country, the Nancy who climbs up ladders and takes possession of fruit walls and hay lofts, the petted idol of her brothers and sisters, the pretty pickle of the family, the Nancy in pink frocks and pinafores, whose innocence and naiveté attract a handsome and middle-aged bachelor. We can appreciate the mystery that comes into the child’s life when she does not know exactly what love is, when she owns that she likes the general better than her father, who has not experience to understand sympathy, but who candidly owns that, child as she is, she can find comfort and “oh, such rest” on the broad manly chest of the brave man who has asked to protect her. The first act of Mr. Buchanan’s play and the first view of his “Sweet Nancy” are wholly natural and charming. The audience seemed delighted with the author’s exposition and charmed with the treatment of it, particularly by Miss Annie Hughes, the drolly argumentative little maiden, and by Mr. Henry Neville, who, in bearing, taste, and tenderness, was an ideal Sir Roger. And in other respects the play opened well. The children were clever and unobtrusive, and Mr. Henry V. Esmond, the boy of twenty, was a positively life-like representative of the natural Algernon Grey.

It is, however, when this curiously innocent, but unquestionably clever, Nancy becomes a married woman that we lose touch with her. Her intellect, always pronounced, does not advance, but goes back. She charms us at the outset with her innocence; she irritates us afterwards with her folly. There never was a more unreasonable, capricious, or contradictory little person. Her conduct is enough to drive the most amiable husband in the world half-crazy, and how such a Nancy with her nursery tears and her baby grief could be a companion for a man of the sympathetic nature of Sir Roger is puzzling indeed. She has sense enough to feel what jealousy is, but is hopelessly blind as to the effect of it on others. She does not like her husband to interest himself in the attractive “grass widow,” but she is so absurdly innocent that she cannot see or feel that Frank Musgrave, the man her sister loves, is attracted by the baby bride as he walks, talks, and hangs about her from morning till night. Such innocence as that on the part of a grown-up woman who is not at all destitute of common sense is inconceivable. A woman’s innocence does not deaden her instinct, and it is assuredly a very dangerous virtue when it does. A married woman who tempts away her sister’s lover has no right to say, when he catches her round the waist and makes furious love to her, “Who would have thought it?” This is exactly what happens to Mrs. Tempest (Nancy) when her husband is away at the wars. The dangerous and cynical Musgrave has been dangling at her side all day for months past, looking into her eyes, sighing for her, and, according to the man’s account, making love to her, but when her tacit encouragement is misunderstood all she has to say in excuse is, that she thought she was only aiding the cause of her sister Barbara. The innocent little flirt has been making love by proxy—a very convenient and plausible arrangement for everyone but her absent husband and her sister Barbara. But after all no harm has been done. When her sister’s lover clasps Nancy’s waist and tries to kiss her she very properly repels him. The scene that ensues is discovered, but it is easily explained. Nancy, according to her own account, has done no harm, so why not without any fuss tell her husband, and rid the house of the conceited Musgrave, without compelling poor Barbara to bring the poor repentant cavalier back in order to make a humiliating confession before the three people he has wronged? However, there is the play, and there is the stage Nancy. They must have pleased the audience, in spite of their apparent inconsistencies, for the curtain did not fall until nearly midnight—on a Saturday of all days in the week—and such was the courtesy extended towards author and artists that they were called, cheered, and Mr. Buchanan, after a slight opposition, was allowed to give Miss Broughton all credit for her work. It may sound paradoxical, but “Sweet Nancy” can only be shortened by lengthening it. The play must be relieved of much “top-hamper,” the valuable blue pencil must be called into play, and for all that it must be played in four acts instead of three.

Mr. Henry Neville never swerved in his task, and played the manly husband admirably from end to end. As someone has already aptly observed, he was too young for a general in the English army, and a little too old for such a pinafore pet as Nancy, but the charm of Mr. Neville’s performance was that he showed the young heart and the tender nature under the iron-grey exterior. He was in reality younger, and, perhaps, more attractive to women than the blasé and cynical lady-killer, Musgrave. In action, in attitude, in facial expression, tender in love and stern in command, a husband-lover, but a domestic disciplinarian, surely the Sir Roger of the story could not have been better played than by Mr. Neville. It was in the emotional scenes that Miss Annie Hughes failed to touch the right note of pathos. The Nancy of the orchard was more natural than the Nancy of the drawing-room. If it was not the author’s intention that Nancy should give even the semblance of a woman’s cry when her husband left her for the wars, she might have given us the child’s cry. It should have been a cry with meaning in it, but it was an empty, hollow cry that meant nothing. We doubt if the grief of Nancy—whatever it was—touched many in her audience. Miss Annie Hughes made the whole house laugh with her, but never cry for her. The Algernon Grey of Mr. Henry V. Esmond was really a very remarkable performance, observant, incisive, and wholly natural. The character is the obverse of that of Nancy. The sister is tempted by a vicious man; the brother is caught in the toils of a vicious woman. The chivalry of this lad towards his handsome temptress, the earnestness and impulse of his first love affair, were expressed with surprising force and nature by this young actor, who has evidently the artistic temperament. Miss Frances Ivor was not happily selected for the character of the “grass widow” who wanted style; Mr. Bucklaw played the villain in the conventional stage manner, and made love to order, automatically. Mr. Ernest Hendrie and Miss Ethel Hope were both successful as the dictatorial husband and the meek wife, and Miss Harriett Jay did excellent service by playing with so much tact and judgment the part of poor Barbara, who ought to be prominent on the stage, but is almost a “persona muta.” All our sympathies ought to go out to this patient Martha of the romance, but poor Barbara has been unaccountably neglected. The child, “Tow Tow,” by Miss B. Ferrar, was delightful. When the new play has been curtailed and better rehearsed it will no doubt prove interesting, and will be warmly discussed by those who are so fond of analysing character and motives. It played slowly on Saturday because no one seemed confident. When will managers understand the value of adequate rehearsal?

___

The Yorkshire Post (14 July, 1890 - p.4)

Mr. Robert Buchanan is varying his wide experience as a dramatic author by doing a little theatrical management on his own account. The Lyric Theatre has fallen temporarily into his hands, and on Saturday night a new piece, entitled, “Sweet Nancy”—the product of his prolific pen—was presented for the first time. It is an adaptation from Miss Rhoda Broughton’s novel of the same name, and tells the story of a young girl who marries an old General out of respect for his good qualities, and subsequently becomes the innocent object of his suspicion through the designs of a young rascal whom she supposes to be in love with her sister, and admits to her house on terms of intimacy. As in most plays of the kind the plot depends for its success upon misunderstandings and misconceptions which a few words would explain, but which, somehow or other, never are explained until the last moment. This imparts an air of unreality to most of the scenes, and leaves the audience at the end a little exasperated with the characters who are so foolish as to wilfully place themselves in the wrong by avoiding common-sense methods of clearing themselves. There are, however, so many bright episodes in the play and such strength in the dialogue that one feels almost inclined to forgive the flimsiness of the superstructure upon which the piece is constructed. A little compression would certainly be of advantage, but if that is done there is no reason why “Sweet Nancy” should not have a good run.

___

The Derby Daily Telegraph (14 July, 1890 - p.2)

OUR LONDON LETTER.

_____

LONDON, Monday Morning.

. . .

’Tis true ’tis pity, pity ’tis ’tis true that Mr. Robert Buchanan is a little too fertile. Of late he has out-distanced all rival dramatists in productiveness, and the latest sample of his stage-work “Sweet Nancy” is creditable pot-boiling, and that is all. It was performed at the Lyric Theatre on Saturday night to an expectant house, b ut when the curtain fell at midnight there was a chill of disappointment. Miss Broughton’s novel of “Nancy” is an extremely clever bit of characterisation, but in the adaptation some of the bloom was taken from the flower. It would seem as if Mr. H. A. Jones’s dictum that modern drama cannot be literary if realism is to be retained, bears truth in its kernel. Some bright bits that read so charmingly in the novel rather bore one on the stage. But the comedy allows Miss Annie Hughes to show herself in a part that must go a long way to attract crowded houses. She is the hoyden who marries the middle-aged military man, not because she loves him, but to keep things pleasant in the family. There is a strong scene when Mr. Henry Neville, as General Tempest, starts for South Africa on active service. Emotion is not Miss Hughes’s strong point. but the mixture of complaisance and regret, mischievous yet dolorous, with which she received her doting husband’s farewell, seems just the outcome of the pretty tomboy’s temperament. A young man hangs around pretending to be infatuated with her sister Barbara, but really in love with Sweet Nancy, who tries to help the couple to an understanding, but unfortunately places herself in an awkward position with the treacherous lover on the eve of her husband’s return. Were the piece a trifle less thin in plot, and much of the verbosity cut out, “Sweet Nancy” would be an ideal comedy, fresh and exhilarating as the charming actress who creates the title rôle.

___

Truth (17 July, 1890 - p.21-22)

PLAYS AND PLAYERS.

It is quite clear to my mind that Mr. Robert Buchanan writes too much. The amount of work he gets through in the course of the year is prodigious. When he is not adapting Fielding and Smollett for the Vaudeville, he is tinkering French plays for the Haymarket; when he is not pouring forth his poetic soul into classical plays for the Lyric, he is discussing social questions in the Daily Telegraph, or knocking off little lyrics for theatrical advertisement. And now he is afflicted with the inevitable mania, and has rushed wildly into theatrical management. They all do it, and live to repent their folly. It is the same story with women and men alike. The constant calls on the cheque-book necessitate medical certificates. So the enthusiastic manageress, when she has exhausted her bank balance, is found to be suffering from such depression that she is sent away for change of air; and the ardent young manager, who intended to undertake the labours of Hercules acting, managing, dining out, organising charitable matinées, entertaining the aristocratic hangers-on of the playhouse—suddenly is attacked with clergyman’s sore throat, and is compelled to pull down the curtain. “Nancy” would have been a far better play than it is had Mr. Buchanan not been his own manager. He had it all his own way, and it was exactly this fact that kept the audience on Saturday night in the theatre until midnight, and filled the theatre with yawning friends and despairing critics. The successful author of the day deprecates managerial interference. His triumphant cry is, “I did it!” But he conveniently forgets what the manager, and the stage-manager, and the practical prompter do behind his back. In most cases they do not “cut” his work; they literally “knife” it. They pull whole pages out of his manuscript, pin them together, and cast them away, as Beau Brummel’s valet did to his master’s spoiled cravats. “These are our failures!” grins the prompter, as he eases the text of a burden of words and flings them into his desk. It is all done secretly in the dark; it is the deed of the midnight assassin. The author comes next morning betimes and bawls out, “Stop! where are my words?” There is an explanation, an altercation, an apology, a temporising—what not. The author flies into a passion, he will not be responsible, his best lines have gone; he rushes away into the corridor and tears his hair. But the play is saved, and when it makes a success, the bitter past is forgotten, and it is the author who has done everything. If there had been any one on the stage when “Nancy” was rehearsed who knew his business or cared to interfere, there would have been no need to ask Mr. Buchanan to use the reaping-hook, and to cut out a good hour’s superfluous talk.

As a play “Nancy” seems to be a kind of protest against the doctrines of the realists. It was supposed that the cry of the period was for women as they are on the stage, not for women as they are not. I doubt if an Ibsen or a Tolstoi would have shown us the infatuation of a man of forty-seven for a maiden tomboy, a raw, inexperienced weed in the garden of girls. An “old man’s darling” usually belongs to men of a more advanced age. Experience goes to forty; innocence charms sixty. An officer on active service would be somewhat inconvenienced by such a perplexing partner as Nancy, who is sharp enough to understand the world and its ways when it suits her, but lapses into the kittenish stage when it is more convenient to play the game of buttercup innocence. The rustic romp, who, tired of climbing ladders, soiling her pinafore, playing monkey tricks with her brothers and sisters, finds the broad and manly chest of a handsome English officer, is at least an intelligible being. There is a trace of the old Eve in her. But the married woman who encourages the attentions of a philandering cynic—engaged, by the way, to her own sister—and cannot see that this vicious fellow is making desperate love to her, is either an amiable little fool or a deceitful little baggage. Nancy is the kind of woman who “looks behind,” and when the inevitable consequences of “looking behind” are brought home to her she pretends to be vastly indignant. This is an old trick, and condemned alike by women and men. There is no sympathy for the innocent girl who looks over her shoulder and “makes eyes.” For such a wife there should be very short shrift, and it becomes a little tedious when Nancy’s husband comes home and holds a kind of informal trial; hearing witnesses and getting evidence on the subject of Nancy’s moral delinquencies. It really does not matter one straw. A man who marries a little fool with his eyes open must expect folly as the result of his good nature. It does not seem to me that Mr. Buchanan has on the stage rightly interpreted Miss Rhoda Broughton’s idea. It is certain that he cannot have done so, for Miss Broughton’s heroine is everywhere pronounced “charming,” whereas Mr. Buchanan’s “Nancy” may fairly be considered—at least in her married state—as a little whimpering nuisance.

It is said that the play has been in existence for years, but has been constantly postponed, for the very good reason that no “Nancy” was forthcoming. In that case it ought to have been postponed a little longer, for Miss Annie Hughes only understands one phase of the character. She is a delightful romp, but she has apparently no appreciation of any subtlety that may exist in the study of a strangely contradictory little person. It is acting on the surface as it were. Miss Hughes can pout and pet, and speak her cheeky love admirably, but she is always Miss Annie Hughes, and never “Nancy.” She is the clever actress, not the character. She plays the part easily, but without thinking very much about it. As an example of the other and truer method, look, for instance, at the “boy-man,” the newly-fledged officer entrapped by a wary married woman, played by a Mr. Esmond, whom I never remember to have seen before. How thoroughly the young fellow understands the position. The remnants of the boy are left in him when he larks with his brothers and sisters; the ambition of the man is present when he tries to influence and captivate this middle-aged flirt. The high spirits of the lad, the chivalry of youth, the blind, sentimental devotion of the neophyte are admirably expressed. This was by far the best bit of acting in the play, and Mr. Neville was at hand—as he ever is—to give weight and dignity and power to the play. Mr. Neville is an actor who understands his business, and is always fresh and interesting. He never acts as if he were bored with a part, but always as if he liked it. We do not see too much of such acting nowadays. When “Nancy” has been properly edited and prepared for stage production it may do; but after its trial trip on the measured mile it wants a considerable amount of overhauling. There is something wrong with the safety-valve, and it should be put into dock for repairs before it can safely go on a long cruise.

___

The Stage (18 July, 1890 - p.10)

THE LYRIC.

On Saturday, July 12, 1890, was produced at this theatre a three-act comedy. founded by Robert Buchanan upon a novel of Miss Rhoda Broughton’s, and entitled:—

Sweet Nancy.

Sir Roger Tempest ... Mr. Henry Neville.

Frank Musgrave ... Mr. Bucklaw.

Mr. Grey ... Mr. Ernest Hendrie.

Mrs. Grey ... Miss Ethel Hope.

Barbara Grey ... Miss Harriett Jay.

Algernon Grey ... Mr. Henry V. Esmond.

Nancy Grey ... Miss Annie Hughes.

Robert Grey ... Mr. C. M. Hallard.

James Grey ... Master Walter Highland.

Teresa Grey ... Miss B. Ferrar.

Mrs. Huntley ... Miss Frances Ivor.

Pendleton ... Mr. Smithson.

Footman ... Mr. A. R. Bennett.

There is, perhaps. no one better versed than Mr. Robert Buchanan in the difficult art of transferring the incidents of a novel to the stage—an art which he has practised with conspicuous success, even in the case of novels, like “Tom Jones,” previously accounted undramatic. High expectations were, therefore, formed of his version of Miss Rhoda Broughton’s “Nancy.” Perhaps it was for this reason that a certain amount of disappointment was felt with regard to the new piece which has followed The Bride of Love in the evening bill of the Lyric. It has been hinted in some quarters that Sweet Nancy is really an old play extracted from Mr. Buchanan’s pigeonholes because he happens to find himself in possession of a theatre. That may well be the case. Indeed, Mr. Buchanan has himself stated publicly that the vogue of Sophia, and other recent productions of his pen, enables him to find a market for MSS. that had accumulated in his desk during the previous ten or fifteen years. As Miss Broughton’s novel dates from 1873, and considering the multiplicity of Mr. Buchanan’s engagements, it is not unreasonable to suppose that Sweet Nancy is not the work of yesterday. At all events, we prefer to think of it as an early and immature work, seeing that, as it stands, Sweet Nancy is by no means worthy of its author’s reputation. The really dramatic portion of Miss Broughton’s story, which is Mr. Buchanan’s by adoption, is not strictly new. That a soldier husband should be ordered off to the wars and be possessed on his return by a fear that his wife has been unfaithful to him, is one of the earliest ideas of fiction. Hector and Andromache, or Ulysses and Penelope are perhaps the remotest examples in point, and the annals of the Divorce Court might furnish a parallel to them at the present day. There is no doubt, however, that such a situation is good material for drama. The only debateable question is its method of treatment. In Sweet Nancy we have an elderly general, Sir Roger Tempest—for elderly he considers himself at 47—and, not without some misgiving, he marries a young romp and madcap in Nancy, who is quite young enough to be his daughter. Such a theme a novelist may treat at great length and in much psychological detail without ceasing to be interesting. On the stage, however, effects must be made sharply and swiftly, and in the drawing of his chief characters we feel that the adapter has, of necessity, fallen into a certain sketchiness, which detracts from their interest. With all the care which Mr. henry Neville bestows upon Sir Roger Tempest, we hardly know what manner of man is this middle-aged warrior, who speaks as if women had, all his life, been to him a sealed book, and who allows himself to fall over head and ears in love with a graceless young hoyden, scarcely dignified enough to be in long frocks. Is it mere naïveté on the general’s part, or is it one of those consuming passions that come, we know not how? Mr. Buchanan does not tell us. On the other hand, Nancy’s passion seems to have no deeper roots, to begin with, than a kind of filial respect for Sir Roger, who, although he “has been to school with father,” is a much nicer and more agreeable man. The novelist has time to show us this sort of attachment ripening into love, but in the play we have to take it for granted. In the first act of Sweet Nancy, therefore, where the foundations of the story are laid, there is a certain vagueness of outline in character and situation, which rather deadens the sympathy of the house. It is, perhaps, the inevitable result of an attempt to dramatise Miss Broughton’s psychology. As a settling to the love affairs of the General and Nancy we have a troop of Nancy’s young brothers and sisters playing the part of Greek chorus—that is to say, commenting upon the action at every turn. They may be interesting enough in a book; on the stage their childish babble becomes a little irritating to sensitive nerves. In the whole of the first act, in fact, there is but one character who has the true dramatic ring, namely, the tyrannical, brow-beating, irritable, and cantankerous father of the numerous Grey family. He is a living type; Nancy and her General are but unsubstantial phantoms. In the second act we see the happy home of Sir Roger and his young bride, who has now left off pinafores, and become woman enough to be jealous of her husband’s apparent attentions to a grass widow. As she is entirely mistaken in her interpretation of these attentions, however, the interest looked for by the episode is but languid, and the end of the second act is reached before anything like a dramatic situation occurs, namely, the young wife’s realisation of the fact that her husband is ordered off upon active service. Such as it is, of course, this situation has been more than anticipated in Caste. The kernel of the play, which so far has been, like the novel, chiefly of a descriptive characters, is reserved for the last act. Barbara has been courted by Frank Musgrave, but during the General’s absence this young man, who, as the French would say, is a bit of a fin de siècle-ist, turns his attention to Lady Tempest, while she is innocent enough to encourage him, under the impression that she is promoting Barbara’s interests. Here, again, we may complain that the dramatist has not kept in touch with human nature. No woman could be quite so naïve as Lady Tempest. The relations arising between Lady Tempest and Frank Musgrave set the grass widow’s scandalous tongue wagging, and Sir Roger comes home accordingly in a furious state of jealousy. Does Lady Tempest at once clear her character, as under the circumstances she is bound to do? Not at all. Like the attorney who has a bad case, she abuses the opposite side, though, as Sir Roger aptly reminds her, two blacks to not make a white. This childish misunderstanding prolonged the last act on the opening night beyond all reasonable limits, a course all the more inadvisable, because the audience are perfectly aware of the true state of matters. In the end, Sir Roger is convinced of his wife’s innocence by Musgrave’s giving him a positive assurance to that effect, as if the correspondent in a divorce suit were not expected, as a matter of course, to swear to the lady’s innocence. We have indicated some of the points that tend to make Sweet Nancy an unsatisfactory play. Whatever the result may be in a pecuniary sense, no reproach will attach to the acting. Mr. Henry Neville lent the author invaluable aid by his manly and carefully thought-out rendering of the part of the tardily-smitten General; Miss Annie Hughes delighted her audience in the earlier scenes by her girlish embodiment of the title-rôle, albeit in the more pathetic scenes her performance was less convincing; Miss Harriett Jay did all that was possible with the effaced rôle of Barbara, and the same remark applies to the Frank Musgrave of Mr. Bucklaw. To Miss Frances Ivor was allotted the task of appearing as the fascinating and scheming grass widow who ensnares young Algernon Grey, a character very cleverly impersonated by Mr. Henry V. Esmond, and the parts of Mr. and Mrs. Grey were in the safe hands of Mr. Ernest Hendrie and Miss Ethel Hope. Nancy’s ladder-climbing and romping brothers and sister were interpreted by Messrs. C. M. Hallard, Walter Highland, and Miss B. Ferrar, the last-named creating a most favourable impression throughout the piece. The smaller parts of the butler and footman were adequately rendered by Mr. Smithson and Mr. A. R. Bennett.

Preceding Sweet Nancy, a comedietta by Arnold Golsworthy and E. B. Norman was performed, entitled:—

An Old Maid’s Wooing.

Rev. James Braithwaite ... Mr. E. B. Norman

Henry Higgins, Esq. ... Mr. E. Hendrie

Roger Gammon ... Mr. Henry Bayntun

Miss Hester Grayson ... Miss Ethel Hope

Naomi Wild ... Miss B. Ferrar

This little trifle treats of the courtship, late in life, of a kindly-disposed and benevolent old maid by a couple of somewhat unromantic admirers—to wit, the rector of the village, the Rev. James Braithwaite, and an enriched retired tradesman, who is called the Squire, though his manners are rougher than those of H. J. Byron’s Perkyn Middlewick. It is only very languid interest at the best that is felt for the loves of elderly people on the stage, and as there is nothing special in the treatment of the subject by Messrs. Golsworthy and Norman, the general verdict in such cases is hardly likely to be reversed, albeit the acting of the comedietta left little to be desired. Mr. E. B. Norman gave a capital rendering of the part of the country rector, his make-up being equal to his acting; and Miss Ethel Hope was suitably sympathetic as the old maid, who appears to be everybody’s benefactress in the village of Churton-cum-Wolcote. Mr. E. Hendrie, needlessly we think, accentuated the vulgar manner of the retired tradesman, and Mr. Henry Bayntun also gave a rather too highly-coloured portraiture of the poaching farm labourer. Miss B. Ferrar, however, made a delightful young servant-girl, and An Old Maid’s Wooing was, on the whole, well received.

___

The Era (19 July, 1890)

THE LYRIC.

On Saturday, July 12th, for the First Time,

a New Comedy, in Three Acts, by Robert Buchanan,

Founded on Miss Rhoda Broghton’s Story “Nancy,” entitled

“SWEET NANCY.”

Sir Roger Tempest ... Mr HENRY NEVILLE

Frank Musgrave ... Mr BUCKLAW

Mr Grey ... Mr ERNEST HENDRIE

Mrs Grey ... Miss ETHEL HOPE

Barbara Grey ... Miss HARRIETT JAY

Algernon Grey ... Mr HENRY V. ESMOND

Nancy Grey ... Miss ANNIE HUGHES

Robert Grey ... Mr. C. M. HALLARD

James Grey ... Master WALTER HIGHLAND

Teresa Grey ... Miss B. FERRAR

Mrs Huntley ... Miss FRANCES IVOR

Pendleton ... Mr SMITHSON

Footman ... Mr A. R. BENNETT

Those familiar with Miss Rhoda Broughton’s charming story “Nancy” must have expected a great treat from Mr Robert Buchanan’s adaptation of the same, announced for production at the Lyric Theatre on Saturday last. There is certainly little plot in the novel; but it has been proved, in the case of Little Lord Fauntleroy and other pieces, that a story can be almost dispensed with, provided idyllic charm is present. Enthusiastic applause followed the descent of the curtain on the first act on Saturday, and the audience prepared themselves for an evening of enjoyment. Unfortunately, the high expectations thus created were not realised. Mr Buchanan, experienced adaptor as he is, had missed his way in his treatment of Miss Broughton’s delightful book, and had overloaded hii idyll with commonplace dramatic effects. If the promise implied in the programme had been fulfilled—if Sweet Nancy had begun at nine and ended at eleven, it would have been difficult for the most clumsy versionist—and that character does not describe Mr Buchanan—to smother in weariness the enjoyment which the audience could not fail to take in the humour and sentiment of the story. But, altogether, the work of dramatic presentation was unadroitly and carelessly done. A piece which of all pieces required finished rehearsal was so imperfectly prepared for performance that blunders and hesitations on the part of the artists were frequent; and what with the dialogue being taken in too slow time, what with the unnecessary elaboration of certain situations, the audience, when a quarter to twelve was reached, were utterly out of patience. When the curtain fell a difference of opinion was freely expressed, and Mr Buchanan, coming before the curtain, in vain endeavoured to shift from his own shoulders some of the responsibility of the failure by referring to Miss Rhoda Broughton as the responsible authoress of the piece. It was not Miss Broughton’s book but Mr Buchanan’s adaptation that was hissed and hooted by a large number of those present.

Most of us are pleasantly familiar with the slight narrative of “Nancy,” and remember how the heroine, growing up in the flower of simple English girlhood at an old country house, snubbed, like her brothers and sisters, by a pragmatical parent, and as free from affectation as from selfishness or sentimentality, is admired and wooed by a middle-aged officer, one Sir Roger Tempest. Her elder sister, Barbara, is being courted in a dubious, unsatisfactory manner by Frank Musgrave, who is really secretly smitten by the attractions of Nancy herself. The latter becomes Lady tempest, and soon learns to deeply love her elderly husband. But the serpent, in fact two serpents, soon present themselves in this connubial Eden. Mrs Huntley, an artful grass-widow with whom Sir Roger is connected by a friendship for her absent husband, his old comrade-in-arms, lives near the Tempests; and Nancy’s jealousy is roused by this fine lady’s tone of familiarity with Sir Roger, and by her patronising and satirical manner to the young Lady Tempest herself. Before Nancy and her husband can come to an explanation on the subject, he is called away to the seat of war in the Soudan, and she is left behind with Frank Musgrave, and with her sister Barbara, with whom Nancy believes that the young man is in love. After an interval of a twelvemonth, Sir Roger’s return is announced, and Musgrave, in desperation, dashes into an avowal of his passion, which astonishes as much as it disgusts the unhappy Nancy, who bursts into tears, and is found with Musgrave in a compromising situation by Mrs Huntley and Nancy’s hobbldehoy brother, who is “mashed”—to use a vulgar but expressive term—on the fascinating grass-widow. The latter mentions the incident to Sir Roger, who demands an explanation from his wife. She is too much hurt and astonished by his suspicion to answer, and is further kept silent by her wish to conceal the fact that her sister has been to all intents and purposes jilted by the worthless Musgrave, who after Nancy’s repulse has gone up to London and announced his intention of thence proceeding to the Continent. There is a strong scene in which Mrs Huntley, brought face to face with Nancy, reiterates her insinuations, and finally the General’s suspicions are entirely removed by Musgrave, who, having been sent for by Barbara, makes a full confession of the truth, and clears Nancy from all blame.

The audience on Saturday were undoubtedly bored by the piece as a whole; ut it may not be too late, if vigorous measures are immediately taken, to turn the quasi-failure of Sweet Nancy into a success. It is simply a question of elision and judicious condensation. The children—by making one of whom, Tow-Tow, a pretty little lass instead of the gaunt, spindle-shanked, youngster described in the book, the author and management lost a chance—should be less seen and heard; the emotional passages should be curtailed, especially the parting scene at the end of the second act. The lovesick Algernon should recede into the background, and all the interest should be kept concentrated upon Nancy and Sir Roger. In doing this the piece would naturally be cut down forty minutes; and certainly two hours is quite long enough for an idyll of this kind to play.

We can hardly believe that a performance containing so exquisite an embodiment of ingenuous maidenhood as Miss Annie Hughes’s creation of Nancy is doomed to early oblivion. Miss Hughes has almost a monopoly of parts of this kind, and her impersonation of the charming child-wife was delightful in its delicacy of touch, its artless grace, its quaint and unstrained humour. For the sake of her Nancy alone, the piece ought to ripen into a success. Mr Henry Neville’s Sir Roger Tempest surprised even those who, knowing how long this excellent actor has been before the public, know also how wonderfully, by his potent art, he can defy the hand of Time. His Sir Roger was a performance admirable in every respect. In the earlier acts the General, elderly as he was, seemed a man any woman might be proud of being loved by; and it is hardly necessary to write that his imitation of angry emotion in the last act was forcible and convincing in a very high degree. Miss Harriett Jay, in the rather redundant rôle of Barbara, played with quiet cleverness; and Miss Frances Ivor, though now and then at a loss for a word, neatly suggested the insincerity and artfulness of Mrs Huntley. Mr Bucklaw as Frank Musgrave made the most of his opportunities, and managed to realise exactly the personage suggested by the novelist. Mr H. V. Esmond hit off the peculiarities of the amorous Algernon very neatly. It was an excellent bit of character acting, and deserved none the less credit because the youth became, from no fault of Mr Esmond’s, an irksome bore. The “boys,” as Nancy was so fond of calling them, were cleverly represented by Messrs C. M. Hallard and Walter Highland; and Miss B. Ferrar looked very pretty indeed as “Tow-Tow.” Mr Hendrie, though hardly aristocratic and vinegarish enough, made the stern parent, Mr Grey, sufficiently funny; and Miss Ethel Hope was just what was required as the submissive wife. The scenery was pretty, and Miss Hughes’s dresses were charmingly artistic. Sweet Nancy was preceded by a piece, in one act, by Arnold Golsworthy and A. B. Norman, entitled

“AN OLD MAID’S WOOING.”

Rev. James Braithwaite ... Mr E. B. NORMAN

Henry Higgins, Esq ... Mr E. HENDRIE

Roger Gammon ... Mr HENRY BAYNTUN

Miss Hester Grayson ... Miss ETHEL HOPE

Naomi Wild ... Miss B. FERRAR

This sketch, previously played at the St. George’s Hall, proved too tame and conventional to interest the audience at the Lyric Theatre last Saturday. The idea of a vulgar suitor getting a friend to plead his cause with a lady, with the result of the said friend winning her love, is far from novel. That, however, would have mattered little had the authors utilised the notion in a fresh and dramatic manner, but the reverse was the case. An Old Maid’s Wooing is an instance of the managerial notion that anything will do to play thee stalls and dress-circle in with and to keep the pit and gallery quiet for half-an-hour. This system has brought levers de rideau into such disrepute that everyone endeavours, if possible, to escape from seeing a “first piece.” So long as managers look upon the curtain-raiser only as a necessary expense to be reduced to a minimum, so long will this state of things exist. Mr Hendrie may be commended for his neat impersonation of the sporting squire, and Miss Ethel Hope and Mr Norman were efficient as the old maid and her clerical wooer. There can be no doubt that the irritated feeling produced in the popular parts of the house by the feebleness of the first piece had a good deal to do with the severely critical verdict passed upon Sweet Nancy by the pit and gallery.

___

The Graphic (19 July, 1890)

THEATRES.

THE jaded playgoer who is always pining for something fresh and truthful—something which betokens observation of life as opposed to a mere re-dressing of the too-familiar puppets of the playwright’s conventional world—has just now an excellent opportunity of showing his sincerity. Freshness and disregard of stage tradition are the pre-eminent characteristics of the new play which Mr. Buchanan has fashioned out of a novel by Miss Rhoda Broughton, and produced at the LYRIC Theatre; but the obligations which the author of Sweet Nancy has conferred upon the playgoing public do not end here. He has not only furnished an original and interesting play, but contrived to get it acted by a company who are with scarcely an exception able to free themselves from that besetting failing of their profession—a tendency to fall into the vein which is popularly known as “stagey.” There are no intricacies of plot, no very startling situations, no “sensations” of any kind; but the story is nevertheless interesting, and the types of character are admirable both in themselves and in the skill with which they are contrasted in the working-out of a clearly-defined purpose. All that happens between the rising and the fall of the curtain upon the third and last act may be summed up in the facts that a middle-aged officer in the Army falls in love with a schoolgirl, marries her, grows needlessly jealous àpropos of her alleged flirtations during his absence abroad, discovers his mistake, and finally takes her to his arms again. Yet the spectators follow the history of the courtship and wedded life of General Tempest and Nancy Grey with a constantly increasing sympathy, and find in the dialogue and incidents of the play—in spite of some occasional redundancies which may easily be removed—unfailing entertainment. For this fortunate result the author is indebted in no small degree to Miss Annie Hughes’ delightful portrait of the impulsive, wayward, but thoroughly sound-hearted heroine, whose career put in so strong a light the truth of the maxim that if a free and open nature and a habit of giving unconstrained utterance to thoughts and feelings in plain English have their inconveniences, they may also have their countervailing advantages. Nancy is at all events a very natural as well as a very womanly personage. We not only grasp her character, but we also understand how it has been nurtured and developed in the unruly playground of Mr. Grey’s ill-regulated establishment. The very frankness and honesty of the overgrown schoolgirl appear to be fostered by the harsh domestic despotism and systematic self-seeking of her father—a character played, by the way, with a very artistic eye to essentials and a true sense of humour by Mr. Hendrie. It is the natural antagonism of an unsophisticated nature. The General is the man of her father’s choice, and Nancy does not pretend to have any sentimental regard for him; but what regard she does profess is at least honest, and the spectator is quite prepared to find her feeling towards her high- minded and chivalrous husband develop into genuine affection. If Mr. Henry Neville would but pitch the tone of the elderly officer’s passion in a little less heroic vein, the situation would gain a touch of truth. “Bobby,” “The Brat,” and “Tow-Tow,” together with their brother Algernon, aged twenty, who falls so romantically in love with the “grass widow,” Mrs. Huntley—the evil genius of the story—are cleverly “differenced,” and presented with wonderful spirit by Mr. Hallard, Master Walter Highland, Miss B. Ferrar, and Mr. H. V. Esmond respectively; while Miss Harriet Jay gives a pleasing individuality to the portrait of Barbara, who in the play fills a less important part than in the novel. We are not quite sure whether the perfect harmlessness of its story will recommend the piece to the jaded playgoer; but we are certain, at least, that Sweet Nancy ought to prove to be one of the most popular of the recent productions of our stage.

___

The Illustrated London News (19 July, 1890 - p.3)

THE PLAYHOUSES.

The trial trip of Mr. Robert Buchanan’s “Sweet Nancy” was, on the whole, very favourable. Audiences are apt to become impatient, particularly n a Saturday night, and an author who allows his play to last until midnight runs a very considerable risk; but this particular Saturday-night audience sat patiently, and sacrificed the parting glass, until the clock struck twelve at the Lyric Theatre. All this speaks volumes in favour of Nancy, and, by the time she is ready for Mr. A. M. Palmer’s theatre in New York, I expect her skirts will be shortened that were found trailing on the ground, and that this delightful creature will be smartened up a bit. As for myself, I candidly own that I have never read Miss Rhoda Broughton’s novel, nor do I think it is necessary to do so in order to enjoy Mr. Buchanan’s play. But I can guess how a clever novelist would revel in the scenes that deal with the Grey children, how she would describe and enjoy, in the impudence of the Brat and Tow Tow, scenes that belong to the descriptive writer and not to the dramatist. Mr. Buchanan has very wisely kept all this episodical and incidental matter carefully in the background. He knows by experience well enough that a theatrical audience resents exactly what the novel-reader enjoys. A little more of these children, and they might have irritated instead of charmed. It is always the case when children are brought out of the nursery or the school-room. The central figure of the play is—as she should be—Nancy, and, thanks to Mr. Buchanan and Miss Annie Hughes, it is Nancy to whom all our interest is devoted. The play opens charmingly, and the “pleasant little devil,” as Nancy calls herself, is realised to the very life by the clever actress. We understand her thoroughly—a romp, a tease, the favourite of her rough brothers, the idol of her younger sister. The scenes between the middle-aged soldier and the innocent child at the outset are charming—he so earnest, she so provokingly natural; he so bashful and diffident, she so assertive and demonstrative in her baby philosophy. Anyone can understand the position of the handsome General who is so strangely attracted by this child of nature. He has arrived at the age when, as a celebrated French dramatist puts it, “a man has fear” so far as a woman is concerned. His nervousness is, to the child, incomprehensible. What should she know of the world or love? She cannot precisely differentiate between her father and her lover, but she only knows vaguely that she fears the one and is attracted by the other. The father has a dictatorial, irritating way with him; the lover has a broad manly chest on which the child pillows her head, and there she feels “Oh! so restful!” So far, we seem to understand Nancy thoroughly.

It is when she becomes a married woman that she and her actions are not quite so intelligible. I am told that it was the object of the novelist to keep up the childlike innocence of Nancy to the very end, that she was to be the child-wife throughout—a most difficult task for dramatist and actress to perform on the stage. I cannot quite decide whether it was the fault of Mr. Buchanan or Miss Annie Hughes, but I candidly own that my warm interest in Nancy seemed to fade away directly she became a married woman. She seemed no longer natural, but artificial. She was a real girl, but not a real woman. There may be women whose childlike innocence is preserved through the cares of married life, women who are children to the very end; but they are phenomena, and surely it may be said that the innocence that is the cause of encouraging vicious men, and breaking innocent women’s hearts, is a very dangerous kind of innocence. There is such a thing as instinct even with the most innocent women in the world; and a woman’s instinct would impress upon her the danger of winning to her side the man who was to marry her own sister. Just conceive the position. Barbara, the sister of Nancy, is seriously attached to a modern cynic and blasé man of the world. Barbara and Nancy have their sisterly confidences. Nancy wants Barbara to marry the man she loves. The cynic is apparently attached to Barbara, and yet the innocent Nancy actually conceives she is assisting her sister’s cause by attracting her lover to her side, and is so blind that she cannot see that the lover in question has no eyes for Barbara but all eyes for Nancy. So innocent, indeed, is Nancy that it comes upon her as a thunderclap when her sister’s lover suddenly turns round and makes desperate and passionate love to Nancy, the wife of the cynic’s best friend. Now, all this may be natural. Doubtless it has occurred in real life, but this particular quality of innocence is not such as would commend itself to our sympathies. The purest and most innocent women should be on their guard. Instinct puts them on their guard. Nancy may be true to life, but her attitude in this dilemma is not one that should be quoted as an example that young girls may very safely follow. You see, the difficulty is that Nancy is first presented to us as rather a knowing young lady; so far as her experience goes, she “knows her way about”; she can argue with surprising facility; she is jealous by instinct of a grass widow in whom her husband takes an interest; and yet she cannot, for the life of her, see that her sister’s lover is making love to her. I cannot help thinking that Miss Annie Hughes did not quite get under the character at this juncture. It is a most difficult task, no doubt, requiring the greatest subtlety in distinction on the part of the actress; but I own that Nancy’s attitude of mind when she was married I could not quite follow. I am reminded at this point of cynical Iago’s remarks on women, and of a part of his description in particular—

She, that could think, and ne’er disclose her mind,

See suitors following, and not look behind;

She was a wight,—if ever such wight were,—

To suckle fools, and chronicle small beer.

It would be difficult to secure an actor better suited to the part of the General than Mr. Henry Neville. He has all the passion of a young man preserved under the dignity and decorum of middle age. He is at once earnest and tender. He rules a woman with precisely the force that women love, and no more. He is never angry, always firm. He shows all the protective power of the father with the devotion of the lover. Presumably, this was exactly what Mr. Buchanan wanted in his hero. And there was another part excellently played—the boy-lover, by Mr. Esmond, the chivalrous youth who is caught in the dangerous snare set by the grass widow. The part was played in exactly the right spirit, naturally and without affectation, like a boy, but with all the budding enthusiasm of a man. I somehow think that more might have been made of the character of Barbara. In art, Barbara is a deliberate contrast to Nancy, but she is only a half-and-half contrast in the play. It looks to me as if “Nancy” were written with the deliberate intention of making it a “one part play,” and Barbara was purposely kept down in order that the star’s triumph might not be interfered with. Otherwise, the suppression of Barbara is unaccountable, for she is relatively as interesting as Nancy. If this be the case, if it be true that a clever author purposely kept Barbara under in order that the star heroine might not cry her eyes out or turn round and say, “Why, Miss So-and-So has got quite as good a part as mine,” then we could not have a finer example of the evils of actor or actress management. All credit to Miss Harriett Jay for doing what she did with Barbara. She played the part so charmingly that we wanted more of her. She should have been brought out of the background and put into relief. Miss Jay spoke Mr. Buchanan’s pretty speeches admirably, but she was “Charles’s friend,” whereas she should have been Charles’s companion. In interest there should not have been a pin to choose between Barbara and Nancy. Miss Harriett Jay was loyal to her task, and the very excellence of her acting showed what a beautiful part Barbara might have been made. It is said that “Nancy” has been long on the shelf, failing a stage Nancy. But was not the part precisely made for Miss Winifred Emery, who has shown Mr. Buchanan what she can do in sentiment and sport both in “Clarissa” and “Miss Tom Boy”? “Nancy” ought to have been another Vaudeville success, ought it not? However, it is very good as it is, and when it has been altered it will be a great deal better still.

I must postpone until next week my notes on the delightful rendering of “As You Like It” by the Daly Company at the Lyceum, and my description of Miss Ada Rehan’s superb rendering of Rosalind, incomparably the best ever seen on the modern stage. We seem to live again with the “giants of old” when Miss Rehan acts. She sweeps everything before her with her grand style.

C. S.

___

The Illustrated Sporting and Dramatic News (19 July, 1890 - p.17)

LYRIC THEATRE.

IT is often difficult to understand the enthusiasm with which third-rate efforts are received at those trial matinées where one would expect the “trial” to be one not only of the piece, but of the spectator. But this is after all comparatively easy to account for, since an afternoon audience is known to be slow to anger and readily pleased, whilst those playgoers of another class who chance to be present come expecting very little, and are in consequence thankful for extremely small mercies. These considerations, however, did not apply to the first performance at the Lyric Theatre of Mr. Buchanan’s Sweet Nancy, a poor and inartistic play which throughout two of its three acts was received as though it were a masterpiece. The mystery of the undeserved applause must therefore remain unsolved and insoluble, save on a hypothesis we for our part should be very reluctant to entertain: but the author-manager will none the less do wisely not to attach too much importance to Saturday night’s friendly verdict.