|

BUCHANAN INTERVIEWS

The World (New York) (28 September, 1873)

TALKS WITH BRITISH BARDS

_____

ROBERT BROWNING AND ROBERT BUCHANAN

INTERVIEWED.

[CORRESPONDENCE OF THE WORLD.]

LONDON, September 14.—Robert Owen was undoubtedly a very extraordinary man—that is to say so far as notoriety is concerned. He managed to make himself popular for a time—he was a man greatly talked about. And he gathered around him certain enthusiasts who “went in” for socialism with a will and left their legitimate “tracks” to follow their apostle who was to regenerate mankind by loving kindness. But although this teacher, who from all accounts was a most lovable man, failed in his philanthropic efforts, his followers did not fare so badly. They had very little but the tools of their trade to throw down in order to follow him; they had little to lose and everything to gain. As a rule they were shrewd young men, combining the new creed with commercial interests; they possessed brains enough to see a way to “bettering” themselves, and so these disciples of Owen—comprising butchers and bakers and candle-stick makers, embryo tradesmen—went forth after a certain training to preach the new doctrine through the length and breadth of the British Isles.

The father of Robert Buchanan was one of the most successful lecturers in the new cause. The conviction of the truths of Owen’s doctrine came to him whilst pursuing the honest and useful occupation of a tailor in the town of Ayr. He was galvanized into elasticity, and uncrossing his limbs leapt almost in a bound from the “schneider’s'” board to the platform of the local lecturer.

Buchanan pere was the most successful and the most beloved of the flock. His name became popular; he “wrote to the papers” and picked up knowledge of all kinds whilst stumping the country, and when Robert Owen died he was able to face the world of London as a full-fledged journalist. In process of time he married a lady of Staffordshire—good- looking, highly intelligent, and imbued with socialistic views. After a successful sojourn in London, on the House of Commons staff of the Sun, Buchanan had a brilliant offer from Glasgow, and like a sensible Scot accepted it. He became first of all editor and then proprietor of the Glasgow Sentinel.

Robert (the only child), although born in Staffordshire, may be considered a Scotchman. He was raised from the age of five years in Glasgow, and, drew his first poetic inspirations from the classic banks of the Clyde.

“You must have been like Chatterton, a ‘marvellous boy,’” I said to him the other day, when discoursing about his early career.

“There was nothing startlingly marvellous about me except my idiosyncrasies as a boy of fourteen.”

“Wherein did these consist?”

“To speak candidly, my father was too indulgent to me and my mother too good.”

“You were a petted bairn, then?”

“Something like it, my dear fellow.”

“You were left very much to the freedom of your own will, I suppose?”

“A great deal too much till my parents sent me to a boarding-school at Rothsay, where the restriction on my liberty became proportionately severe. I do not hold with boarding-schools as a rule. In the case of sensitive boys the alienation from the parents produces a morbid melancholy and moral cowadice—a shrinking abhorrence, almost amounting to terror, of meaner but grosser natures. In the case of hardier youths the moral sensibilities (to whatever extent they may exist) are blunted, and lads of that kind become bullies proportionately to the power of their biceps.

“I could not stand the life,” continued the poet. “Twice I fled home, per steamboat, to Glasgow, and arrived tearful and desolated at the home of my parents. On both occasions I was conveyed back to Rothsay. I became stronger, and, fortified by the sympathy of my parents, plucked up heart of grace and pursued my studies with a will.”

“And of course, picked up a deal of knowledge?”

“Well, I mastered the rudiments of an English education; but I was generally considered a duffer, and had no chance with the other boys.”

“What about the influence of the elements around you?”

“Ah! therein consisted the sweetness. I used to ‘moon’ my mornings and afternoons inland amongst the hills, with the gleam of sea between me and the jagged peaks of Arran. I felt the ‘skyey’ influence upon me. Not to put too fine a point upon it, my boy, I began to think I was a poet, and it is extraordinary the comfort, if you call it so, this consciousness brought me.”

“It made you mad, I suppose?”

“‘Eccentric’ was the word used with regard to me when I returned to Glasgow by a select circle of admirers. There were others who put me down as a conceited young prig who ought to have been birched.”

“Ah! and your own opinion par example?”

“Well, I had a stupid idea that the ignobile vulgus of the Western metropolis ought to doff their bonnets as I passed.”

“A foolish idea.”

“Yes; very much so. I got more sense with the growth of my whiskers.”

“They are luxuriant enough now.”

“You are kind to say so.”

Thereupon, after a little badinage, Buchanan, whose career I had known in outline for many years, recounted to me graphically the struggles he had at the commencement of his life in London.

“You know, of course,” he said, “the loss I suffered by the death of David Gray. This oppressed me more than the family misfortunes. For a time I was consumed with melancholia. But I was obliged to be up and doing. I wrote almost night and day—scattering sheets of prose and verse over the magazines—cheered and encouraged by the friendship of Sidney Dobell, Lord Houghton, and G. H. Lewes, and earning a little money.”

“And about Charles Dickens?”

It is unnecessary to give Buchanan’s reply to this query. I have heard him over and over again recount with glistening eyes and fervid utterance his loving and grateful appreciation of the kindness and encouragement he had received from the great humorist. As I write these lines there flashes back upon my brain the recollection of a certain summer afternoon when myself and the subject of this brief sketch were reclining in lotos-eating ease on the deck of a little thirteen-ton yacht, just moored after a two days’ cruise round the Island of Barra and up and down the Sound of Mull. We were just thinking of bestirring ourselves to get home to the poet’s shooting-box, about two miles distance from the town, when, rounding the point, we descried the smoke from the funnel of the Glasgow steamer on her westward way. We agreed to wait for the newspapers; despatched the yacht-man to bring them. In process of time he arrived, and the first item of intelligence that fell upon our eyes was the announcement of the death of Dickens.

Buchanan was suffering from severe nervous debility at the time. I am sure he loved and reverenced Dickens as an elder brother and a master to the guild of literature. The shock of this intelligence threw him back for weeks.

Between Walt Whitman and Buchanan there exists the most intense sympathy. They frequently correspond by letter, and one of the most cherished portraits in the British poet’s library is the portrait of his distinguished brother across the Atlantic.

I am glad to be able to state that my distinguished friend has almost entirely recovered from his long illness, and is busily engaged upon ambitious literary venture.

ROBERT BROWNING.

“Take my word for it,” said Robert Browning in my hearing to a young poet who has since become popular, “’tis a mistake to go out of England for inspiration.”

His argument was something to the effect that Italy was all very well in its way—plenty of burning, blazing passion, but from a British point of view difficult to manage, distorted, unnatural.

“I regret nothing more than the time I have wasted on the land of the Madonna. I am convinced of this fact, that if I had written chiefly on English subjects my books would have been more popular.”

“Better understood, in fact.”

“Precisely.”

There was a shade of gloomy dissatisfaction on the poet’s brow as he spoke.

Browning’s grievance against the British public is that they will not take the trouble to analyze those wonderful efforts of his, and he is proportionately disappointed, not to say soured.

Not long ago I happened to be at a fashionable gathering at the West End of London where Browning was expected. The great man arrived late, but walked into the salon with the consciousness that he was the lion of the evening. And I am bound to say in strict candor that he looked as if he thoroughly enjoyed the distinction. Your readers I dare say are familiar with his clear-cut features, the exquisitely shaped nose and beautifully moulded chin. But photographs fail to do justice to the eye; there is something in it mild and yet watchful, keenness overshadowed at times with a kind of dreamy melancholy (the latter I believe inseparable from the genus).

At the risk of being considered almost profane I venture to state that the author of “Paracelsus” is a short, dapper little man, with a tendency to embonpoint. He would look well as captain of an Atlantic liner, pacing the poop with quick, jerky steps; nor would he look out of place as a respectable shopwalker in a fashionable emporium in St. Paul’s churchyard or a store in Broadway.

That is to say, provided he did not open his mouth to speak.

There can be no doubt about the fact that Browning of late years has got rather testy and intolerant of his contemporaries.

Walt Whitman is rather the fashion here at present, but Browning can’t be induced to believe in that eccentric writer.

“Pooh, pooh!” he said, in his deep, resonant voice, to one of a small coterie who was upholding the claims of the transatlantic bard; “coarse, untutored, absurd. What can you think of such an expression as this?”—

And here he quoted a line which certainly was not fit for feminine ears.

“Ah, my dear Browning, but these words were written many years ago.”

“There is not a page of “Leaves of Grass” or “Drum Taps” but is filled with absurdities—not to say bestialities—of the same description. I am astonished how it can be accepted as poetry.”

The little lion was wrathful and the subject was not pursued.

There can be no doubt about it that Robert Browning is a disappointed man; and the pity is that be betrays it. In society he is restless, nervous; destitute entirely of the dignified “repose” of the great Alfred. People who know him intimately tell me that he is greatly changed since the death of the gifted wife whom he loved so well.

By the way, it is not generally known how these two came together. The authoress of “Aurora Leigh” was the daughter of an English gentleman of an eccentric turn of mind. This eccentricity took the form of a morbid objection to the poetess getting married; and he kept her strictly secluded from the world in an old country mansion. The monotony of her life was relieved by intense, hard study; before she was twenty years of age she had mastered Greek, Latin, French, and German, and made her voice heard in lyric strains through the medium of the magazines. Her effusions attracted the notice of Browning. He managed to elude the vigilance of the father and the warder at the gates, and one day, presented himself before the poetess, unintroduced, almost unannounced, and boldly asked her hand in matrimony. They were above the conventionalities of ordinary society. The barriers were swept aside and the two gifted creatures were united. There was only one child, who is now a good-looking young fellow of about nineteen.

_____

[Note: The next two interviews from Buchanan’s visit to America are transcribed from rather imperfect scans. In both there was one sentence which defeated me, my ‘best guess’ is therefore rendered in a different colour. The New York Daily Tribune page is available here.]

New York Daily Tribune (Saturday, 6 September, 1884 - p.2)

A TALK WITH ROBERT BUCHANAN.

_____

THE NOVELIST’S ERRAND IN AMERICA.

_____

HIS DRAMATIC CAREER—OPINIONS OF ENGLISH

AND AMERICAN ACTORS.

Mr. Robert Buchanan, the well-known English author, who is now visiting in this country was visited Thursday, by a member of THE TRIBUNE staff, and in the course of a conversation, imparted some interesting news concerning his present trip to America. Mr. Buchanan is a typical Englishman in appearance and manner. He is of medium height and of stout build, and wears a handsome beard carefully trimmed after the manner of the Briton. Since his arrival in this country, about three weeks ago, he has been spending his time alternately at the Hoffman House, in this city, and the Pavilion Hotel, New Brighton, Staten Island. He is pleased with America and the Americans; but, like all English authors, deplores the absence of any satisfactory international copyright law. He has for many years been one of the most conspicuous defenders in London of American plays and players, against the hostile criticisms of some of the English papers. On being asked what was his chief object in visiting America, Mr. Buchanan replied:

“Purely practical. I have been, as you are perhaps aware, connected with practical management as well as playwriting, and I wish to complete an artistic and financial scheme, for which I have already secured valuable support in London; but I want to increase my capital by co-operation with a man of dollars in America. Then, I had to see Messrs. Shook & Collier about my new play, which they are anxious to secure, and to arrange for the production here of a new comedy, which will be produced in London late this fall, with one of our brightest actresses, Miss Kate Vaughan, in the leading part.”

“How many plays did you produce in England last season?”

“Too many—three; ‘Stormbeaten’ at the Adelphi, ‘Lady Clare’ at the Globe, and ‘A Sailor and his Lass’ at Drury Lane. The last named was only partially my handiwork. I received over £5,000 for my share in it, but had I had my own will in its arrangement, it would have been a different play.”

“Your collaborateur was Mr. Augustus Harris. Did he really do any of the work?”

“Certainly. Mr. Harris is one of the cleverest men I know, and it is quite a mistake to class him with uninstructed managers. I believe he formed too low an estimate of the public taste, but that is neither here nor there; he is educated, able and knows his business. However, I do not believe in collaboration, except under extraordinary circumstances. If a dramatic conception is worth anything it can be worked out best by the mind which incubated it.”

“Is your new play a melodrama?”

“No, a drama of society, with plenty of humor; I am convinced the public taste lies in that direction. It also deals much with American life and scenery. Some years ago I published two anonymous poems, ‘St. Abe,’ and ‘White Rose and Red,’ both of which had a phenominal success in Great Britain. Reviewing one of them, The Spectator said: ‘Would that in England we had humorists who could write as well, but with Thackeray our last great humorist left us.’ It was very funny to be taken as an American author.”

“Your poems and novels have a large public in England as well as here?”

“My publisher, Messrs. Chatto & Windus, could tell you best about that. This autumn they will issue my complete poetical works in a cheap edition, and they expect an immense sale. The edition published ten years ago in England, and republished here by Messrs. Field and Osgood, was not representative. My most popular poems are as dramatic as my plays; ‘Fra Giacomo,’ ‘Nell,’ ‘Liz,’ ‘Phil Blood’s Leap,’ ‘Tiger Bay,’ and hoc genus omne, are read wherever the English language is spoken. But I of course attach more value to my larger poems, which are caviare to the general. The ‘Book of Orm’ and ‘Balder the Beautiful,’ by the way, are in high favor among spiritualists—why, I could never quite make out.”

“In your latest novel you dealt a good deal with clerical and religious subjects. Was not ‘The New Abelard’ violently attacked by the English press?”

“By some newspapers; the press, from The Times downward, were friendly enough. The book was orthodox enough for my friend, Dr. Benson, the Archbishop of Canterbury, who introduced me on the strength of it to several of his bishops. But I must tell you that certain English journals abuse everything I write and do. It pleases them and doesn’t hurt me, much. My articles in the Contemporary Review on the ‘Fleshly School of Poetry’ and the ‘Newest Thing in Journalism’ have secured me this life-long honor. The Athenæum, in particular, pursues me with vampire-like pertinacity, which is ungrateful as at twenty years of age I was its leading literary critic! You and other little boys are doing what I did then. Theodore Watts, who lives permanently with Swinburne, is a power on the Athenæum. Personally, Watts is charming, and would not hurt a fly; as a critic, he is like us all—he loves his friends.”

“Is it true that you were reconciled with Rossetti before he died?”

“It is so far true, that he expressed his full appreciation of my amende to him in the dedication to ‘God and the Man.’ I believe he was a great and good man. My article on the ‘Fleshly School’ was a mere squib, written in hot haste. It was just neither to Rossetti nor to Swinburne. Personally, I have no animosities. I believe all criticism, my own criticism included, to be friendly or unfriendly by bias. Of myself I can at least say one thing, that I never refused my homage to moral or intellectual worth, and that I have done more than most men to assist my literary brethren.”

“Your life must have been a busy one, Mr. Buchanan. As poet, novelist, dramatist and critic you have had your hands pretty full, yet you are a young man?”

“Forty-three. I love all forms of work. In addition to the vocations you have named, I have been war correspondent to a London daily, I have acted, I have lectured, I have ‘run’ two London theatres. I know the grouse moors of Scotland and the salmon weirs of Ireland, and I am a yachtsman. But my strongest affection is for the stage.”

“What do you think of our American actors?”

“I think that you have one actor who surpasses all actors I have ever seen, except Robson; I mean Joseph Jefferson. Next to him I rank Edwin Booth; a superb actor when suited. I have always had a warm sympathy for American artists, and have noticed with regret the want of appreciation in England of American pieces. We lack your liberality and catholicity of sympathy. When ‘My Partner’ was recently produced in London, I was almost alone in praising; part of it stirred me to the depths. The ‘Danites,’ too, was a strong virile play.”

“Who, in your opinion, are the most successful artists in England?”

“Among women, Miss Terry and Mrs. Kendal are at the head of their profession. Mr. Irving, of course, is the most prosperous actor-manager, but he has a formidable rival, now, in Wilson Barrett. We have no juvenile actor of great power or genius, no one who could hold a candle to your own Charles Thorne. Charles Kelly and Henry Neville are admirable, and Neville possesses the talisman of perpetual youth. J. H. Barnes, who joins the Union Square this season, is a great favorite; handsome, capable and versatile, he only wants a notable part, to make a great impression.”

“Do you remain long in America?”

“That depends. I wish to produce what I consider my best play, the ‘Nine Days Queen,’ with my sister-in-law, Miss Harriett Jay, in the title rôle, and if I succeed I shall remain. The piece, however, is spectacular, and will entail a preliminary expenditure of about $10,000. I consider Miss Jay simply perfect as Lady Jane Gray, in addition to which she is facile princeps as a representative of stage boys—e.g., Cecil Brookfield, in ‘Lady Clare,’ a performance which was the talk of London. Last season she was leading lady of Drury Lane, but she will not appear again in melodrama. She is, also, as you may be aware, a popular and widely-read novelist, having a large constituency of readers in England and America. I have been in communication with Dr. Mallory concerning her appearance at Madison Square Theatre, but I fear the smallness of that theatre makes an engagement impossible. By the way, I am charmed with Dr. Mallory. It is a welcome surprise to find the highest culture and moral elevation of the time in the person of a theatrical manager. In England the Church will not tolerate the theatre. Here it is different, and for that very reason, if for no other, the American theatre of the future ought to surpass all the traditions of the old country. Fortunately for you, you have no censor of plays, for plays need no censor but the press and the public. So long as dramatic art is so fettered in England, playwrights will continue to walk in swaddling-clothes.”

_____

The Buffalo Express (Sunday, 21 September, 1884 - p.6)

Our Looker-on in New-York.

_____

New-York, Sept. 19.—

. . .

“Stage fright in beginners is as inevitable as distemper in a puppy,” said an old actor in discussing this case.

* * *

If anybody alive could, by self-satisfaction, be secure against any such affliction, that person is Robert Buchanan, the English poet, who is now in town. I met him at a performance of his melodrama, “Storm Beaten,” when some of the survivors of the Greely expedition were a part of the stage show. “Critics here and in England have decried the iceberg business in this play,” he said, “and I was curious to ascertain what effect the theatrical representation of Arctic scenes might have on those who knew the terrible reality. I asked Commander Schley what he thought of our polar views, and he told me that the illusion was perfect. The piece, however, has not been produced under my direction, and I disapprove entirely of some changes that have been made in it. As I wrote it, it is very far from being a blood-and- thunder drama. The book on which it is founded is one of the best and most successful of my novels. Clark Russell, who is easily first among writers about the sea, and who is a practical sailor, assures me that the marine descriptions are as grand as any to be found in literature. But it was practically impossible to put on the stage what is the best element of the book. My best play, however, has yet to be seen in America. I have been assured that it is one of the few poetical plays of modern times that will live. It is founded on the life and death of Lady Jane Grey, and my sister-in-law, Miss Harriett Jay, one of the most beautiful women in England—by birth, education, and loveliness, the ideal Lady Jane Grey—will act the heroine.”

How does that strike you for egotism? However, Buchanan is a good critic of other men’s work, and here is what he said to me regarding some Americans: “I have been assailed for saying that your literary men too commonly take a Bostonian view of the universe. Now my admiation of Walt Whitman is profound. He makes me feel the mightiness, the freedom, and the varied humanity of this continent. Other men on this planet are poets; he is a bard, aspiring to the heights of inspiration, and reaching the sublimity of prophecy. I think America possesses in him the most original poet in the world; the noblest soldier in Sherman, the profoundest philosphic physiologist in Draper, the greatest humorist in Mark Twain, the finest living actor in Jefferson, the wisest statesman in Lincoln, and the ablest interviewer in you. But your cigarettes are abominable. Your women—”

“You don’t like them?”

“Nowhere in the world have I encountered the feminine beauty to be found in New-York. Your women are lovely.”

Of course they are, Brother Buchanan, and in the exceptional instances where nature has not made them so they are wishing to do and endure a great deal to secure artificial improvement. ...

_____

The Echo (11 June, 1889 - p.1)

AN HOUR WITH ROBERT BUCHANAN.

“Well, what are we going, to talk about?” was the frank, cheery greeting that met me as I entered Mr. Buchanan’s pleasant sitting-room in Cavendish-place. On looking I beheld a strong-built, brown-bearded man, of middle-age, surveying me through a pair of spectacles, without which he is rarely if ever seen. “Well,” I replied, “Mr. Buchanan, that is rather hard to say. You have lately been so much en évidence that I feel it difficult to know exactly where to begin. Personally I have been interested in all your late appearances; for instance, with regard to your article upon the pessimism of the Modern Young Man, I have found myself so much in accord that I am quite pleased to have a chance of talking to you about it?”

“Yes,” was the slow reply; “the worst of these young gentlemen is they are never in earnest. Their pessimism is the natural reaction following the too great optimism, the too simple faith of their predecessors. They are the product of the spirit of the age. But pessimism in religion, art, in any great work or movement means destruction, pure and simple. The hope of humanity is its life; and without hope it cannot exist. The only remedy I can see for this disease is a wider, more generous knowledge of life. Each man must live his own life. It is that self-pride of the literary class, that hiding away of itself from the great wide world surging around it that is so terribly to blame for all the nonsense these young idiots talk and write. They know so little because they have read so little.”

“Do your remarks apply as much to women?”

“Well, no, but then I don’t know much about the literary woman; by-the-bye, how delightful it was those girls meeting to dine and chat the other day. I liked that very much. People have complained that the names of those present were not widely known. Exactly, and for that very reason were they met together. What need of advertising her whose name is a household word. The idea was to encourage the young beginner, and by word, they want encouragement now-a-days. And they spoke out pretty plainly too, those young ladies. Zola was fully discussed by them, and a general opinion was arrived at that he ought to be read, and they agreed also that all freedom ought to be allowed in literature, no matter how far that freedom might be carried. I am a strong believer in their political emancipation. I think they would vote just as well as men.”

“Ye-e-es,” I said, “but are they not too apt to be led away by impulse?”

“Very likely, and all the better, I like impulse; it is because they are so impulsive that the French are our superiors! But then, you know, I am enthusiastic about women, people tell me I am idiotic to believe in them as I do, but I can’t help it. I have always had faith in them, and I think such a belief is elevating to a man. The Roman Catholic Church is founded on the adoration of the Virgin, it is the basis of a great truth.”

“You mentioned Zola just now, Mr. Buchanan, do you not think he dives unnecessarily into nastinesses?”

“Well, that is a question of art; the English prejudice against him is partly the insular feeling against all that is French. He feels it right to do so, and who am I that should condemn him? Personally I detest his writings, but at the same time I consider him the greatest literary phenomenon of the age. He has innovated and created more than any other writer has ever done. He has opened up a new world. The absolute, naked truth cannot be spoken, more’s the pity. But, if you notice, Zola has always a good moral. He has some absolutely angel characters. One man is a modern Christ, some of his women the sweetest and purest ever known in fiction. Zola will be a classic; he represents an almost unformulated element in literature. No, as you are doubtless aware, I do not agree with the prosecution of Mr. Vizetelly. In his catalogue there is little that is objectionable. I am no believer in tyranny or in the power of the majority. Here the British public determines not to hear about the relation of the sexes; certain things are to be said or not; they hear no more. The vox populi determines these matters, and so, blindfolded, the world rushes on to its destruction. In this particular case of Vizetelly there is, I think, a strong religious inquisition. The collective religious spirit of all the sects is against him; for remember this, all materialism, all pessimism, must press upon priestcraft, and so the Zolas of this world are the sufferers, but in the end they will be the conquerors. Books do not make good or bad people. I hold with Milton, that stern old Puritan, that strong natures require strong food, and that mere knowledge of evil does not make a man or woman bad. In my late article on chivalry, I made a statement much cavilled at at the time, but which has since been voluntarily confirmed by the authorities at the Lock Hospital. But it is impossible whilst this restraint is being placed upon writers and publishers, to speak the truth as one knows it. It is simply the Star Chamber over again, and it will end in worse evil. I contend, for perfect freedom, we must describe things as they are if we are to do any good at all. For this very reason, my “Martyrdom of Madeleine” is all wrong, too conventional. Blackpool refuses to allow its grey-haired inhabitants to read “Foxglove Manor”—there’s hypocrisy for you! We cannot get a subject ventilated on the stage. The Lord Chamberlain licenses almost any nasty leg piece, but a strong, earnest story, with a moral, is tabooed.”

“You have a good many enemies, Mr. Buchanan, have you not?” I asked, with an amused smile.

“Well, yes, I suppose I have. I have an unfortunate way of speaking my mind. I am rather pugnacious; it’s the Irish blood in me, I suppose. But I never bear malice, and I am always ready to own I am wrong. For instance, I withdraw much I said about Rossetti. Froude pitched into me because of my remark that “he was the Nemesis of Carlyle.” And then, again, many of the goody-goodies liking some single remark I have made, have taken me up only to drop me like a hot coal; however, it’ll all come right in time, and I do not doubt I shall shake hands all round before the end.”

“Are you writing anything now?”

“Yes, my autobiography, I think it’ll be interesting. But, then, I have a lot of books lying about unprinted. All my books, except poetry, are almost word for word in my brain before I sit down to write. As a boy I used to sit and wait for inspiration. Now I know the turn of every phrase, and so it comes glowing red-hot to my pen’s point. I have no fixed mode of work, but I generally write just after breakfast. I find this play-writing a great relief. Indeed, had I not taken it up I should have gone mad. I am so exercised about the questions of the day—religious, social, literary. I was brought up in an atmosphere of thought. My father, a Socialist working tailor, ran away as a Socialist lecturer. Robert Owen gave my mother away. Well can I remember, on a steamer at Oban, years after, talking to a steward about the American War. He displayed a marvellous knowledge of the subject. ‘Why,’ I said, ‘where on earth did you get all your information from?’ ‘From your father, Sir, and the articles he wrote in his newspapers,’ was the very unexpected reply. Yes, Kingsley, Hughes, F. D. Maurice—they all knew my father.” R.

___

[Later on the same page the following anecdote about Buchanan occurs in the ‘Men And Things’ section.]

“I like your ballad on Judas Iscariot very much,” said the writer of “An Hour with Robert Buchanan,” in a preceding column of to-day’s Echo, “Is it original, or based on any old legend?” “Well, hardly,” with a slow smile. “I think the mediæval ages would not have treated Judas quite so tenderly as I did. Willard, the actor, told me a curious incident in connection with that little ballad. One night, at a supper at the ‘Green Room Club,’ when things were rather noisy, and stories rather racy, he was asked to recite. He knew nothing but this ballad, which faute de mieux he gave them. He said the effect was electrical, and the feeling intense.” At this moment a great flash of lightning illuminated the room, and Miss Harriet Jay, Mr. Buchanan’s charming sister-in-law, came rushing in. “Take off those spectacles, Robert, at once!” “I’ll do no such thing.” “But the lightning, you dreadful man!” “Can’t help it, my dear; I am not going to take off my spectacles, not even for you or the lightning. Sit down and talk quietly.”

_____

Pearson’s Weekly (20 February, 1892)

WORKERS AND THEIR WORK—No. XXV

—

MR. ROBERT BUCHANAN, POET, NOVELIST, AND DRAMATIST.

—

MR. ROBERT BUCHANAN may very fairly be described as one of the literary giants of the present day. There are few men whose works have been so popular, and who have excited so large an amount of interest both in the wide public who attend his plays, and among the critics who waste much time discussing his theories and opinions.

Mr. Buchanan is a typical Englishman in appearance and manner. He is of medium height, and of stout build, and wears a carefully trimmed beard. He was not born, as some fancy, in Scotland, but at Cavarswell, in Staffordshire, in the August of 1841. His father, whose name was also Robert, was first a Socialist missionary, under Robert Owen, who gave away the novelist’s mother.

He spent nearly all his earlier years in Scotland, being educated at the High School and University of Glasgow. There young Buchanan was cradled in a Socialist centre, and there is little doubt that much that took place in his after career may be traced to the influences which guided his youth. At a very early age, indeed, he showed special gifts for poetry, spending nearly all his spare time in writing.

There is no profession in the world in which it is so difficult to make a name as poetry, and, during those first years of struggle and privation, the future poet and dramatist showed indomitable pluck in surmounting all obstacles. The story of his coming to London when about eighteen years of age, with his friend and fellow-poet, David Gray, is a sad one, and should prove a warning to provincial lads who long to make a mark in London literary life.

It was amid the dusky and dreary darkness of Glasgow, in the year 1860, that David Gray and Robert Buchanan awoke to the fact that to live they must work. They had made each other’s acquaintance as boys, and had spent some years in dreaming and thinking together. One day Gray suddenly said to his companion:

“Bob, I am off to London.”

“Have you funds?” asked Robert.

“Enough for one; not enough for two,” was the response. “If you can get the money anyhow, we will go together.”

The two young men had arranged to meet at the railway station at Glasgow, but, by mistake, they each went to different stations, and so travelled to London at the same time, but by different roads. Oddly enough, they did not meet for some months in the great city, and poor Gray suffered the stings of poverty and privation. One morning, very early, as young Buchanan was walking through one of the parks, he met his old friend, who, although in the first stages of rapid consumption, had been obliged to spend the night in the open air.

Through the kindness of Monkton Milnes, Gray was sent back to his native land to die. Robert Buchanan deserves respectful praise for his fidelity to his suffering friend, and in the touching verses entitled “Poet Andrew,” he has embalmed his memory in lines full of tender heartbreak worthy of a lasting place in the literature of hopeless and baffled endeavour.

Robert Buchanan was more fortunate, and found employment on the staff of THE ATHENÆUM and THE LITERARY GAZETTE, being a fellow-worker on the latter with Mr. John Morley.

Probably none know how hard Mr. Buchanan worked during these early years but himself. Being one of the very few Englishmen of that day who knew the Danish language, he went to Schleswig Holstein and Denmark towards the end of the war as correspondent of THE MORNING STAR. It was on his return from thence that he published his translations of Danish ballads, and wrote freely on Scandinavian literature, an unknown world to the bookmen of that day.

Doubtless in early days he often sighed for such leisure as would enable him to pursue his favourite themes, for to a poet nothing is more dear than the writing of poetry, but the butcher and the baker must be paid, and if the verses will not do it, the poet may think himself fortunate if he can write plays and novels which will.

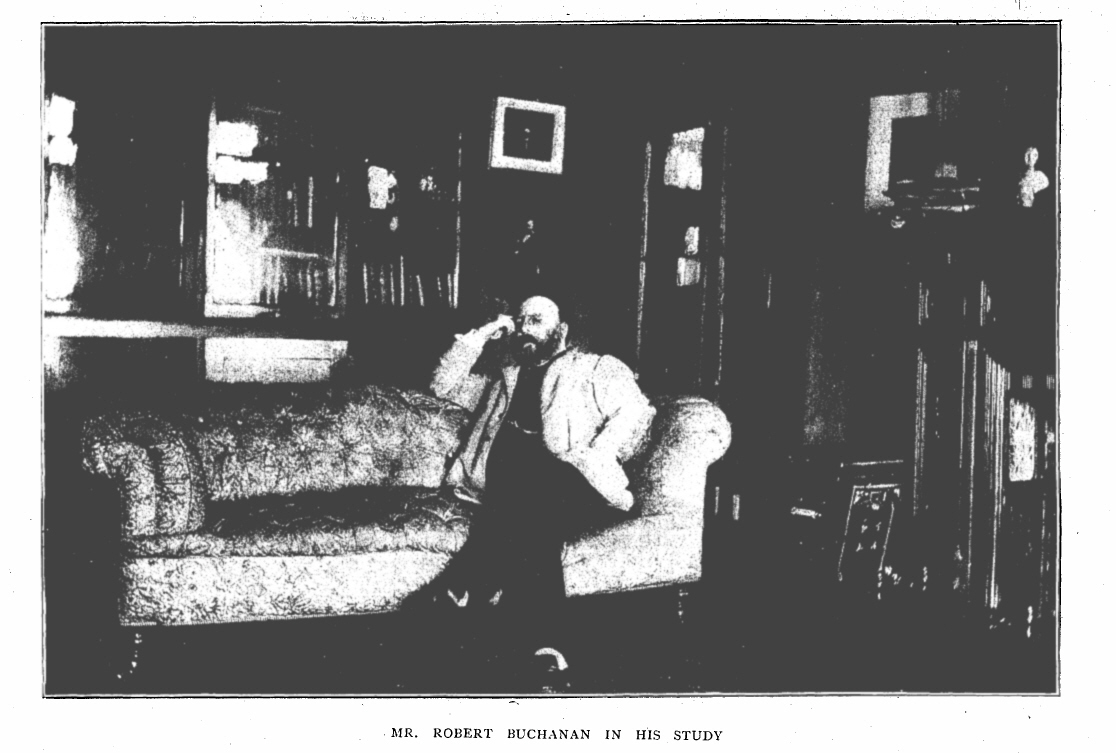

Mr. Buchanan now says himself that he would give worlds to recover some of his early journalistic work, but the magazines and papers in which it appeared have floated out into the space of time, and, as he often did not sign his writings, much that he has done has become lost not only to the world, but to himself. As you sit with the successful writer in his large, comfortable study in one of the most charming houses of South Hampstead, it is hard to realise what the powerful, genial-looking man before you went through some five and twenty years ago.

The man who set himself to make

“The busy life of London musical,

And phrase in modern scene the troubled lives

Of dwellers in the sunless lanes and streets”

has not lost his belief in the goodness of human nature. Like so many other poets, Robert Buchanan has learnt in suffering what he taught in verse. The years of struggle, instead of hardening his nature, have only made his intelligence more purely sympathetic.

“Now, Mr. Buchanan, what do you think of literature as a profession for the coming young man or woman?”

Sharp and clear came the answer. “No one ought to make literature their profession in life; none work so hard or are paid so comparatively little as writers. A great doctor or famous barrister, nay, even the doctor in average good practice or a fourth-rate Q.C., makes more than the cleverest novelist or dramatist. Look at Dickens, who I suppose may be said to have been one of the best paid literary men of the Victorian era—he worked himself to death, but amassed no real fortune.”

“Then, Mr. Buchanan, what would you do with a lad or girl determined to go in for a career of writing, and of no other?”

“I should send them a trip round the world; in fact, I should act with them as I should with a lovesick boy who had set his affections on an obviously impossible and unattainable person. Let those who wish to write, do so in their spare time. Let the profession provide the bread, and literature the butter, if you will.

“To begin with, I must tell you that I do not quite believe in the kind of literary beginner who seeks advice. If a man has it in him to write, he will put pen to paper, however adverse the circumstances round him may be to his doing so. The woman or man who has real literary faculty does not say, ‘I wish to be an authoress, I should like to become a poet.’ She is an authoress, he is a poet. Although I myself never asked anyone for their opinion as to the advisability of pursuing a literary career, Barry Cornwall wrote to me when I was still quite a boy, and strongly advised my not coming to London. I need hardly add that I disregarded his advice, and came, but I always follow my old friend’s example when young people come to me.”

“And yet you yourself must have done all kinds of literary work in your day.”

“I love all forms of work. I have acted, I have lectured, I have run two London theatres. As poet, novelist, dramatist, and critic, I have certainly had my hands pretty full.”

“And your plays, Mr. Buchanan? I suppose that your greatest successes have been made as a dramatist.”

“All my plays have not taken. It is so difficult to say what makes a play popular. So much depends on the interpreters—the actors and actresses. And even if they are all that could be desired, it is impossible to say what will catch the public taste.”

“And when you write a play, do you deliberately try and think out a plot, or do the ideas come of themselves?”

“Whenever I get an idea of any kind, I always jot it down, in order that it may come into use in its proper time. My best work has been done quickly. If I begin writing a play, and find that I stick in the middle, I put the manuscript aside. I have written a comedy within a week, but that is all a question of mood or power of work, and the week meant work all night as well as all day. I have, in my working days, sat up a whole fortnight with only a few winks of sleep. I prefer poetical plays to all others, but good, vigorous prose is worthy for anything. I try to make my characters, whether they be dukes or costermongers, speak naturally. That I hold to be the highest aim.”

“Then you do not believe in stage conventionalism?”

“Certainly not—that is to say, I do not believe that elderly gentlemen keep ancient retainers especially to listen to dream speeches, or that hungry signalmen leave their breakfast to make mathematical calculations of how much per second they are paid for pulling points; the consequence is I am told I write down to the pit and gallery.”

“And do you think that it will ever be possible to write a thoroughly unconventional play?”

“Well, I think all the nonsense about the elevation of the stage is a miserable business. Going to the theatre is merely a more or less harmless form of amusement, like the popular novel or Punch and Judy show. People go to the theatre to have a good time, not to be shown the way in which they should live. Although people think I delight in the melodrama, I am convinced that the public taste lies in the direction of plenty of humour, and my most popular hits have been made in the creation of comedy characters.”

Although Mr. Buchanan talks in this fashion, he has few equals in adapting a story for the stage. His first play was written and produced at Sadler’s Wells as far back as ’62, and was called “The Witch-finder.” Among his most popular plays have been “Alone in London,” which brought him in more money than any other two of his plays put together; “Sophia,” founded on TOM JONES, which ran for five hundred nights at the Vaudeville; “A Man’s Shadow,” “Dr. Cupid,” “Sweet Nancy,” “Clarissa,” and, in conjunction with Mr. George R. Sims, “The English Rose,” which met with such success at the Adelphi.

“I believe, Mr. Buchanan, that you are strongly opposed to the censor in any form?”

“Yes; I do not think that books make good or bad people. I hold with Milton, that strong natures require strong food, and that mere knowledge of evil does not make a man or woman bad. But it is impossible, while the kind of restraint which now exists is placed upon writers and dramatists, to speak the truth as one knows it. We cannot represent truthfully a subject on the stage. The Lord Chancellor licenses almost any music hall dancing or singing, but a strong, earnest, story with a moral, is tabooed.”

Mr. Buchanan’s first novel was THE SHADOW OF THE SWORD, a powerfully-written story, which, indeed, excited great attention, and which was shortly followed by GOD AND THE MAN. His other novels include THE MOMENT AFTER, MATT, and THE MARTYRDOM OF MADELEINE. Few modern works of fiction can compare with GOD AND THE MAN, which will make its author famous for many a long day to come.

His services to literature as a poet were recognised by the State many years ago, when Mr. Gladstone placed him on the Civil List for a pension of £100 per year. Mr. Buchanan resided for some time in France, and it was in Normandy and Brittany that he got the materials for THE SHADOW OF THE SWORD. He also spent a year in America, where his plays are very popular. His first book of poems, UNDERTONES, was published when he was about twenty-one years of age. This was followed by IDYLLS OF INVERBURN and LONDON POEMS. Many other volumes of verse have followed.

“All my books except poetry,” he said, “are almost word for word in my brain before I sit down to write. As a boy, I used to sit and wait for inspiration. Now I know the turn of every phrase, and so it comes clear and red-hot from my pen's point.”

Mr. Buchanan has no fixed mode of work, but he generally writes just after breakfast. He declares that he finds play- writing a great relief, and says that had he not taken it up he would have gone clean off his head, for, until he turned to things dramatic, he took too ardent an interest in the topics of the day, religious, social, and literary. Sometimes, though not often, Mr. Buchanan will talk about his father, the Socialist working tailor. Once, when he was on a steamer at Oban, talking to a steward about the American War, he said:

“Where on earth did you get all your information from?”

“From your father, sir, and the articles he wrote in the newspapers,” was the very unexpected reply.

Robert Buchanan has earnest sincerity visible in every line of his work. This advocate of chivalry is essentially optimistic, as he himself has said, in some noble lines:

“I sing of hope, that all the lost may hear,

I sing of light, that all may feel its ray,

I sing of heaven, that no one man may fear,

I sing of God, that some, perchance, may pray.”

_____

The Echo (25 January, 1893 - p.1)

AN INTERVIEW WITH

ROBERT BUCHANAN.

_____

BY ROBERT BUCHANAN.

The Editor having asked me to interview myself, with a view to answering certain questions which might interest his readers, I have endeavoured, as delicately as possible, to approach my subject. At the moment when the request arrived, I was seated at my own supper table, listening to my good friend Malato’s disquisitions on the subject of Anarchy, and enjoying the brilliant sallies of one of the noblest-hearted, yet least understood, of men, Henri Rochefort. Having been engaged all day with George Sims, disputing whether the heroine of a forthcoming drama should hang herself with her own garters or poison herself with rat-powder, I was not in the most amiable of tempers; but under soothing assurances that the larger portion of the world, including all professional critics, was to be dynamited, I gradually yielded to temptation, and unbosomed myself to the cross-questioner. The first question suggested by the Editor, and put by myself to myself, was categorical.

With what object did you write the “Wandering Jew”?

Because, I replied, I thought that only one subject remained to the modern singer—that of fin-de-siècle Christianity, and because, in my opinion, the legendary Christ of the Gospels was the one immortal spirit which had never been faithfully represented in poetry. All my life I had been haunted by the conception of a worn-out Saviour, snowed over with the sorrow of centuries, old, weary, despairing, yet indignant at the enormities committed in his name. This figure was no fancy to me, but an awful and ever-present Reality. I could not believe in his power to save the world or to discover the God of his promise. But I did believe in his suffering, in the beauty of his character, in his supremely loving tenderness to human sorrow. No longer the beautiful Good Shepherd of early imagination, he seemed to me sad with the sadness of piteous old age, still haunted by his youthful Dream, but scarcely hoping now that it would ever be realised. I was asked:—

Did you intend in the poem to satirise the progress of Christianity among the Churches?

Well, not to satirise—the subject, I think, being too pitiful for satire—but to describe, in a succession of vivid pictures, how Christianity had been a cloak to cover an infinity of human wickedness; how Churchmen had juggled, and cheated, and lied, in the name of Christ, and forgotten the real sweetness of his humanity. Here I was only to do, in verse, what the great historians, from Gibbon to Lecky, had done before me. There was to be nothing in my poem, and there is nothing in it, which could not be justified and illustrated by overwhelming historical testimony.

Why did you omit to describe such things as the cruelty of the Inquisition and the terrors of the Massacre of St. Bartholomew?

Because my book was to adumbrate the truth, not to support it by a mere catalogue of horrors. Because I wished to say just enough, and no more, to point home the charge on which Jesus Christ was to be arraigned, historically, and condemned. That charge was not to be the gist of my poem; otherwise I should be doing no more than other writers had done before me. What I desired to show was the despair of a supremely loving being who began in divine hope and has ended in apparent failure, not because his moral conceptions were false, but because his supernatural promises have never been verified. “Are men worth saving?” Jesus was, then, to ask himself, at the end of eighteen centuries of wasted effort. History, the record of man’s experience, was to supply the answer. Yet my Christ, clinging still to the hope of a heavenly explanation, clinging to that hope as men of his temperament will ever cling to it, was not wholly to despair. Had I made him continue to assert his miraculous pretensions, I should have pleased the so-called Christians. Had I made him admit his utter failure, I should have pleased the Materialists. I desired to please neither.

Do you believe, then, that Christianity is a failure?

Here I referred myself, rather irritably, to my own letters in a contemporary.

One journal says you are an Atheist. Is that so, Robert Buchanan?

I should not be the least ashamed of that even if I deserved it. Unfortunately, I am not an Atheist.

Why unfortunately?

Because, then, the whole question would be easy to me. I should not be lost in wonder at the eternal conflict between Good and Evil.

Do you believe in another life?

Do I believe I breathe and live? Do I believe that I came into this world to lose, not to find, my personality? To one who thinks as I do the question is absurd.

But that other life was Christ’s solution of the problem?

And it is mine; but it is only a belief, not a certainty; a hope, a faith, even, not a reality. The testimony of all Science is against it. The spectacle of human Stupidity, of the colossal selfishness and folly of Humanity, makes the mind despair often, as Christ despaired. And even the theory of another life, of an ever-continuing evolution, does not explain the horrible waste and anarchy of Nature.

Here I took myself severely to task—cornered myself, so to speak, on the subject of my irresolution. There was no escape; I had to answer.

Come, I said to myself, are you not falling between two stools? You think the failure of Jesus was his faithfulness to the conception of a personal immortality, of a God, and of heavenly kingdom, you believe centuries have been wasted over dogmas concerning the absolutely Unknowable; you know Herbert Spencer better, and really venerate him more, than your Bible (here I winced!); and yet you have not the courage to say boldly, this world is the only one, and all we can do is to make the best of it! You are not a Christian, you are not a Theist, and yet you absolutely and indignantly reject not merely Atheism, but Pantheism. Your own “Flying Dutchman,” indeed, was damned by reading the philosophy of Spinoza. What, in the name of common sense, are you? You reject all known creeds, and offer yourself no new one as a substitute.

All creeds, I answered, are to me attempts to verify through the intellect what can only be apprehended by the insight. Just in so far as a creed repels me on the human side, just in so far as it is dogmatic, arrogant, tyrannous over the will, do I cease to follow it. I have absolute, or comparatively absolute, knowledge of only one thing in the Universe—Myself. Sum; et percipi. All beyond myself exists only as phenomena.

In that sense, metaphysically speaking, you are God?

Just so!

God? You—Robert Buchanan!!—who collaborate in Adelphi dramas, write letters to the newspapers, and interview yourself to gratify the whim of an editor and your own self-conceit?

At all events, my own nature is the only touchstone by which I can apprehend the malevolence or beneficence of Nature at large. I love (when I am rational) my fellow-men. I sicken at the sight of human suffering. I would, if I were able, abolish all sin and sorrow. Surveying myself, I am chiefly conscious of one thing—that, without some more ample life than this I live, my functions would be incomplete; I should have existed for no purpose whatever. I yearn for the eternal help and sympathy of those most dear to me. I have held them in my arms as they died; I have been certain, I am certain, that they cannot be dead at all. Personally, I would not care to live a day longer if I were not to live indefinitely. Personally, again, I have no interest in a God outside of myself, whom so many say they “love”; to meet that God I would not care to step one foot beyond the grave! I wish to be reunited with those I have loved, and who have loved me. All Heaven, all hope, all faith, all continuance, is merely an image of my own personality, my own love.

We are getting too metaphysical. The Editor wants to know what you meant by those two lines in the dedication of the “Wandering Jew”:

Father on Earth, for whom I wept bereaven,

Father more dear than any Father in Heaven?

What I meant is expressed in my previous answer. I mean that it is impossible to love what is beyond our comprehension. To love God is to love the mystery of one’s own existence.

You appreciate the ties of this world so deeply, yet you suggest in your poem that human beings, after all, may not be worth saving?

That is the mood of despair which I have expressed through Jesus, in the “Wandering Jew.” Human baseness, and, above all, human stupidity, as expressed in history and corroborated in everyday experience, are so appalling, the aims of life are so trivial, the business of life is so mechanical! But here and there we catch a gleam of comfort, we come face to face with one of those quasi-divine characters, like Jesus,

“Who are the salt of the earth, and without whom

The world would smell like what it is—a Tomb!”

These things restore our faith, at least for a moment.

Your faith in what?

In Humanity, in the perfectibility of human nature. If we deny that, we take away the basis of all Religion, and become pessimists, pure and simple. Pessimism is moral Death, and since the root-idea of modern Christianity is pessimism, or a belief in natural depravity, Christianity is already a dead creed.

I am sorry for you, Robert Buchanan. Believer and unbeliever, outcast from all camps, enemy to all dogmas, where are you to rest your feet?

Here, on the rock of my own personality. If I admit my own baseness, I destroy all the godhead in the world. If I lose faith in my own infinite capacities of love and sympathy, I abolish the last hope of immortality. If I despise this life, this world, even the flesh and its happiness, I spit in the Fountain of all Grace, I accept everything that is human, I reject all the Christian cant about “sin” and “atonement.” It is because this life, at its highest, is supremely beautiful and sane that I believe it will continue. I respect my body too much to call myself a Christian, I loathe the phenomena of evil too utterly to admit myself a Pantheist, and I have too little reverence for what I do not understand to think myself a Theist. I might dub myself a Humanist, if that word did not imply some sort of satisfaction with the intellectual juggleries of Positivism. But I really do not wish to label myself at all. I am content to be in sympathy with all religions, just in so far as they respond to my yearning for personal sympathy and love.

Here, having had quite enough of myself, I cut short the interview.

[Note:

Harriett Jay included most of this ‘interview’ in Chapter 27 (‘The Wandering Jew’) of her biography of Buchanan, however she omitted the first paragraph.]

_____

Black and White (27 January, 1894)

|