ROBERT WILLIAMS BUCHANAN (1841 - 1901)

|

ROBERT WILLIAMS BUCHANAN (1841 - 1901) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

HARRIETT JAY THEATRE REVIEWS

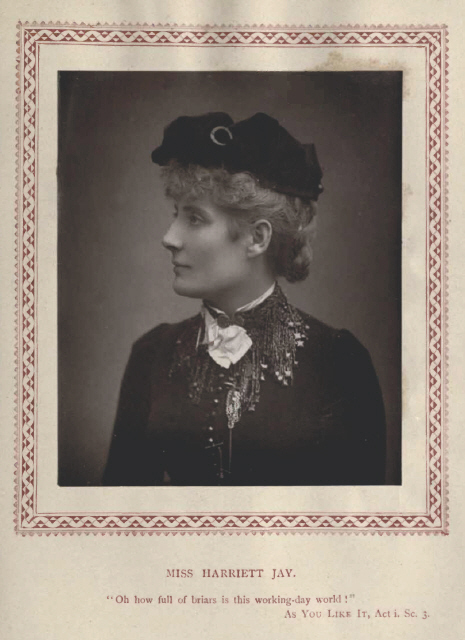

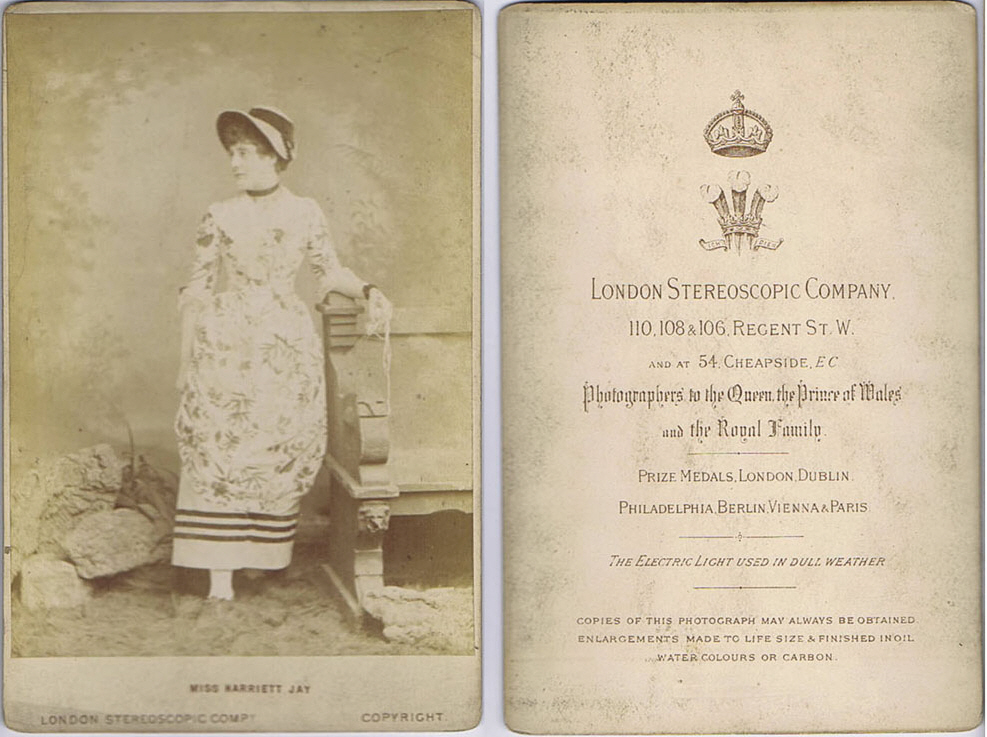

In April, 1888, The Theatre published this photograph of Harriett Jay and a brief biography. |

|

|||||||||||||

|

Miss Harriett Jay combines the twofold occupation of authoress and actress, and in both followings has made a reputation. For years past her pen has employed her leisure moments, and it was in 1879 that Miss Jay first trod the boards with a touring company to get a little insight into theatrical life. After gaining some experience, the subject of our portrait was engaged by Mr. Henry Neville for Kathleen in “The Queen of Connaught” (a part originally played by Miss Ada Cavendish) at the Crystal Palace, and then came to London to appear as Lady Jane Grey in Robert Buchanan’s poetical play entitled “The Nine Days’ Queen.” Miss Jay next went to the Olympic, and besides playing various characters in several pieces, sustained the dual rôles of a Puritan maiden and Charles the Second in “The Madcap Prince;” and then starred as Lady Clancarty in the provinces during a prolonged tour. On her return to London, Miss Jay created the part of the Hon. Cecil Brookfield in “Lady Clare” at the Globe, and also appeared as Lemuel the Gipsy in “The Flowers of the Forest.” After a season at Drury Lane, Miss Jay went to America to produce “Alone in London,” and was the original Tom Chickweed, the street arab, and also gained considerable success there as Lady Clancarty and Cecil Brookfield. At the Olympic she resumed the character of Tom Chickweed, and also played Nan in “Alone in London,” and has since appeared at several matinées. Among her most vivid creations was that of Sappho in the play of that name. Miss Jay was the original Lady Ethel Gordon in “The Blue Bells of Scotland” at the Novelty, but her most remarkable performance was that of Lady Madge Slashton in “Fascination,” which was universally admitted to be one of the most original, clever, and artistic characterisations that had been seen. _____

Harriett Jay’s first dramatic collaboration with Robert Buchanan was The Queen of Connaught in 1877 (although it is never listed as such but the play was based on her novel and there is anecdotal evidence that she was involved in its writing). Lottie was an adaptation of Jay’s novel, Through the Stage Door and was produced at the Novelty Theatre in November 1884 when Buchanan and Jay were both in America. There was no author’s name attached to the play but it was subsequently attributed to Buchanan and it is therefore likely that Jay was also involved in the adaptation. Alone in London and Fascination were both written during the height of Harriett Jay’s acting career and were produced under her own name. Following Buchanan’s bankruptcy in 1894 Harriett Jay collaborated on a number of plays with Buchanan, using the pseudonym ‘Charles Marlowe’. As well as the five plays which received theatrical productions, the Buchanan/Marlowe partnership also produced at least three other works: The New Don Quixote, The Diamond Necklace and the comic opera, The Maiden Queen. There are also newspaper references to an adaptation of Sarah Grand’s The Heavenly Twins although there is no evidence that the play was ever completed. Of course, Harriett Jay’s greatest theatrical success was When Knights Were Bold which was first produced in 1906 with the sole writing credit of ‘Charles Marlowe’. This was originally another Buchanan/Marlowe collaboration from 1896 called Good Old Times. Reviews of Harriett Jay’s theatrical collaborations with Robert Buchanan are included in the main Theatre Reviews section. The Queen of Connaught 1877. Lottie 1884. Alone in London 1885. Fascination 1887. The Strange Adventures Of Miss Brown (As Charles Marlowe) 1895. The Romance of the Shopwalker (As Charles Marlowe) 1896. The Wanderer from Venus (As Charles Marlowe) 1896. The Mariners of England (As Charles Marlowe) 1897. Two Little Maids from School (As Charles Marlowe) 1897. When Knights were Bold (As Charles Marlowe) 1906.

Some information is also available on Harriett Jay’s unproduced plays: The New Don Quixote (Copyright performance 19th February, 1896.) _____

Harriett Jay - Actress

New York Clipper (18 February, 1888 - p.1) |

|||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||

|

HARRIETT JAY. The portrait on this page is that of Harriett Jay, who was born in 1859, and adopted the stage in England about 1880, when she joined a country company and played for some time under an assumed name. Her first appearance under her own name was at the Crystal Palace, London, where she appeared with Henry Neville and played the part of the Queen of Connaught, which was originally sustained by Ada Cavendish. Her first appearance at a West-end theatre was as Lady Jane Grey, in “The Nine Days’ Queen”. After that she played for a season at the Olympic, and then accepted an engagement from George Rignold to star in the provinces as Lady Clancarty. Returning to London, Miss Jay created the part of the Hon. Cecil Brookfield in “Lady Clare,” a part she played during the run of that piece at the Globe. She then accepted an offer from Augustus Harris, and went for a season to Drury-lane. This was followed by a visit to America, where, during her brief stay, Miss Jay appeared as the Hon. Cecil Brookfield and Lady Clancarty, making her debut in this country in the latter role at a special matinee at the Madison-square Theatre, this city, Nov. 26, 1884. On her return to England she was seen at the Olympic in “Alone in London,” playing first the character of Tom Chickweed, a costermonger boy, and afterwards that of Nan. During the run of “Alone in London” she was engaged to appear at matinees at the Opera Comique, in the character of Sappho. During a provincial tour of “Alone in London” Miss Jay played the part of Nan. Many years of hard work were beginning to tell upon her health, so on the termination of this tour she took a long rest. Her next appearance was at the Novelty Theatre, where she filled the parts of Lady Ethel Gordon in “The Blue Bells of Scotland,” and of Lady Madge Slashton in “Fascination.” Miss Jay is the sister-in-law of Rohert Buchanan, the English poet and dramatist. ___

Harriett Jay’s entry in The Dramatic Peerage: Personal Notes and Professional Sketches of the Actors and Actresses of the London Stage, 1892 (compiled by Erskine Reid and Herbert Compton) gives the following brief overview of her career on the stage: Jay, Harriett.—Miss Jay ranks equally high as novelist or actress, and is a sister-in-law of Mr. Robert Buchanan. Although in receipt of a good income from her pen, she decided to take to the stage. Knowing the manager of a country company, she prevailed upon him to let her join it, and her first part was the Player Queen in Hamlet. She then studied for some time under Mrs. Stirling, and prepared herself to undertake the character of Kathleen in the dramatised version of her own novel, “The Queen of Connaught,” a rôle which was originally played by Miss Ada Cavendish. She was next allotted a part in Mr. Robert Buchanan’s play A Nine Days’ Queen, after which she migrated to the Olympic, and then was seen in the provinces in the title rôle of Lady Clancarty. She subsequently appeared at the Globe in Lady Clare, undertaking the boy’s part, a line of character in which she has been particularly successful. To enact this she went in for a regular course of training, adopted boy’s clothes at home, was drilled in a masculine gymnasium, learnt to dance boy fashion, and went so far as to hire a real Eton boy to “study.” The papers were full of her success, which after her elaborate preparations was deserved. And yet, strange to say, she has since developed a positive loathing for masculine impersonations, and regards with distaste any allusion to her triumphs in Lady Clare and Fascination, in which she played a similar character, and quite as successfully. The latter play was written by herself in collaboration with Mr. Robert Buchanan, and the part of Lady Madge Slashton, who masquerades in man’s attire, was evidently inserted on her own behoof. After a short spell at Drury Lane, she retired from the stage for awhile, but re-appeared in 1890 in The Bride of Love, a highly poetical play written by her brother-in-law. It should also be mentioned that in 1887 she was manageress of the Novelty. In the autumn of 1890, she opened at the Royalty with Sweet Nancy, in which she appeared. |

|||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||

|

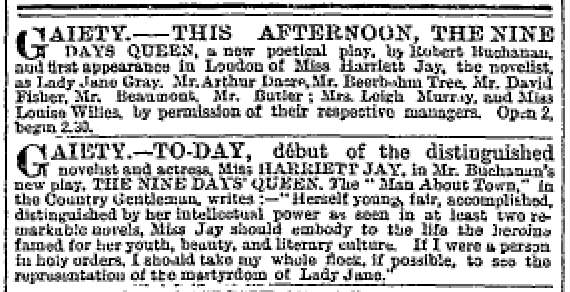

[Advert for Harriett Jay’s first appearance on a London stage, from The Times (18 November, 1880).]

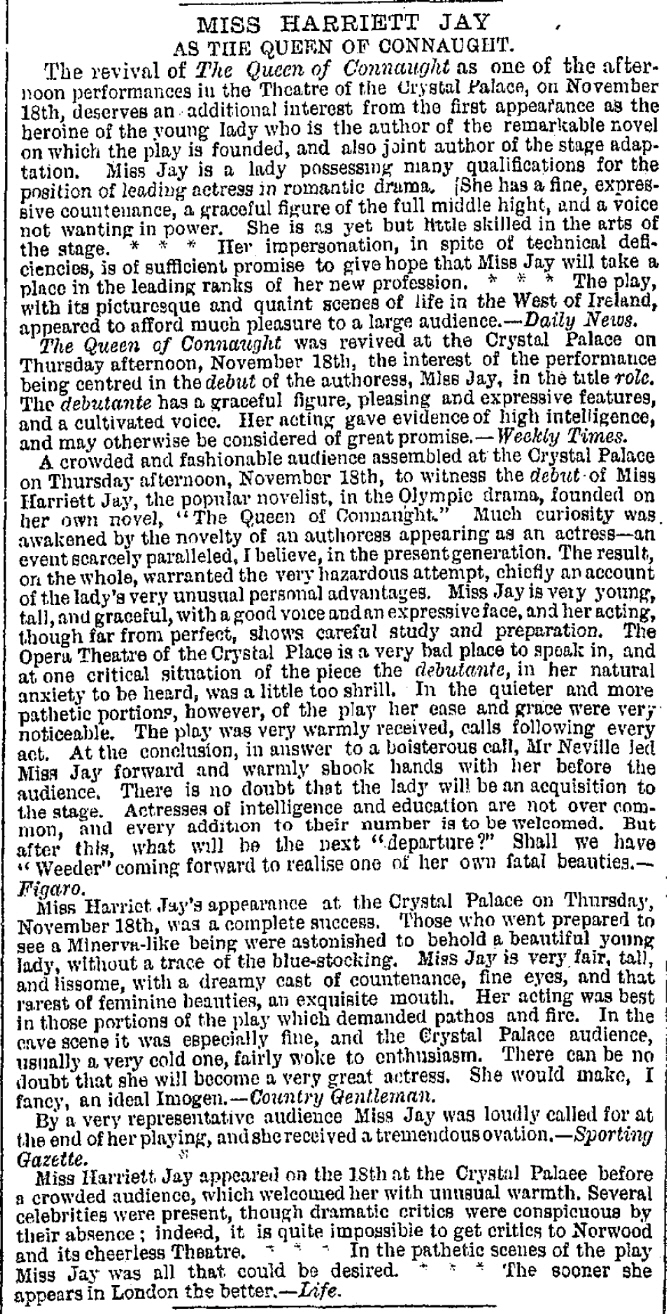

Harriett Jay made her London début as an actress at the Crystal Palace on November 18th, 1880. The Guardian (5 November, 1880 - p.5) “Miss Harriett Jay, the novelist, is about to make her début as an actress in the Olympic version of her own novel, “The Queen of Connaught.” She will appear for the first time in London at the Crystal Palace Matinée on November 17, and will play the part originally sustained by Miss Ada Cavendish.” ___

The Otago Witness (New Zealand) (29 January, 1881 - p.20) Another successful debut was that of Miss Harriet Jay, the authoress, as the Queen of Connaught, at Crystal Palace, on November 18th. “Much curiosity,” writes Cherubino, in the Figaro, “was awakened by the novelty of an authoress appearing as an actress—an event scarcely paralleled in the present generation. The result, on the whole, warranted the very hazardous attempt, chiefly on account of the young lady’s very unusual personal advantages. Miss Jay is very young, tall, and graceful, with a good voice and expressive face, and her acting, though far from perfect, showed careful study and preparation. At the conclusion, in answer to a boisterous call, Mr Neville led Miss Jay forward, and warmly shook hands with her before the audience. There is no doubt that the lady will be an acquisition to the stage.” The Daily News predicts for her a leading place in her new profession. |

|||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||

|

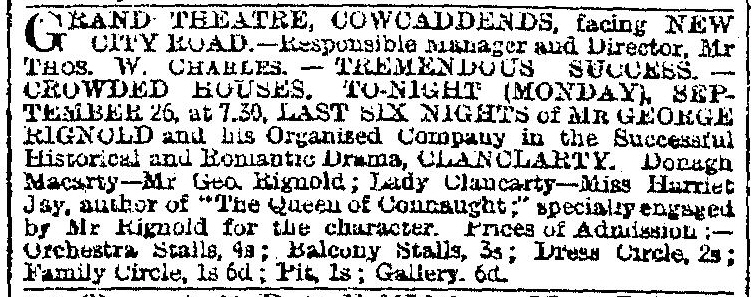

[Reviews of Harriett Jay in The Queen of Connaught from The Era (28 November, 1880).]

The following reviews in the main Theatre Reviews section mention Harriett Jay’s performances as an actress: The Nine Days’ Queen 1880. The Mormons 1881. Lucy Brandon 1882. A Madcap Prince (revival) 1882. Lady Clare 1883. The Flowers of the Forest 1883. A Sailor and his Lass 1883. Alone in London 1885. The Blue Bells of Scotland 1887. Fascination 1887. The Bride of Love 1890. Sweet Nancy 1890. The Wanderer from Venus 1896. In 1884 Robert Buchanan and Harriett Jay went to America. Material relating to the trip is available in the Buchanan’s Theatrical Ventures In America section and contains several press comments, mostly derogatory, about Harriett Jay’s skills as an actress. |

|||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||

|

[Advert for The Nine Days’ Queen from The Times (22 December, 1880 - p.8).]

For the most part Harriett Jay only appeared in plays written by Robert Buchanan, or the Buchanan/Jay partnership. The only exceptions I’ve come across are the Buchanan-produced version of J. B. Buckstone’s The Flowers of the Forest in 1883, her 1881 provincial tour in Tom Taylor’s Clancarty (which was also chosen for her American debut in November 1884), and the one-act, ‘lyrical romance’ of Sappho, written by Harry Lobb and Walter Slaughter.

|

|||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||

|

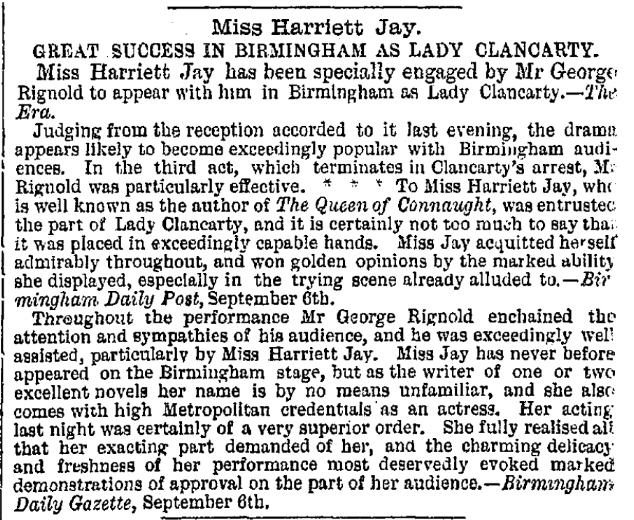

[Reviews of Harriett Jay in Clancarty from The Era (10 September, 1881).]

Glasgow Herald (26 September, 1881) MUSIC AND THE DRAMA. (FROM OUR OWN CORRESPONDENT.) LONDON, Sunday Night. . . . Next week there will be a valuable addition made to Mr George Rignold’s company now playing at your Grand Theatre. “Clancarty” will be put up, and Miss Harriet Jay, authoress of the “Queens of Connaught,” has been engaged to play the part of Lady Clancarty, in which she made so great a success in Birmingham. Miss Jay has in the press a new three-volume novel entitled “Two Men and a Maid.” The book will be published by White & Co., London, about the middle of October. ___

The Glasgow Herald (27 September, 1881 - p.6) THE GRAND. Last night Mr George Rignold’s Company entered upon their second week at the Grand Theatre, substituting for “Amos Clark” Mr Tom Taylor’s historical drama of “Clancarty.” As a matter of course, Mr Rignold appeared in the title role. His name has long been associated with the character, and his interpretation of it is an effective piece of acting, which can scarcely fail to make a favourable impression on an audience. Last night the audience, which was large, gave repeated expressions of admiration and several times called Mr Rignold before the curtain. Miss Harriet Jay gave a dignified and refined rendering of Lady Clancarty, and materially assisted Mr Rignold to make the piece a success. The other members of the company, especially Mr G. T. Minshull as King William III., gave excellent support. The piece is exceedingly well staged. ___

The Era (1 October, 1881) GLASGOW. . . . GRAND THEATRE.—Manager, Mr T. W. Charles.—This redecorated and partially reconstructed Theatre receives a liberal share of patronage notwithstanding strong counter attractions. Amos Clarke and Black-Eyed Susan—the pieces which constituted the opening programme—have given place to Clancarty, and the change of bill is certainly a judicious and welcome one. Tom Taylor’s admirably constructed play has been performed in Glasgow more than once, and is therefore not unknown to local playgoers. It was produced for the first time in this city, however, at the Gaiety, where it proved a brilliant success, and it is chiefly by that production the play is remembered. Now, as on the occasion referred to, Mr George Rignold is the Lord Clancarty. The part is one that suits him to a nicety, and he depicts its various phases most naturally and to the entire satisfaction of all beholders. Miss Brabrook Henderson enacts the part of Lady Betty Noel—which she also played in the Gaiety production—with charming piquancy, her sprightly acting being much enjoyed. Miss Harriet Jay has been specially engaged to sustain the role of Lady Clancarty. Remembering, as we do, Miss Louise Wallis’s splendid impersonation of this character, that of Miss Jay—although artistic throughout—is somewhat disappointing. In the quieter passages her acting is extremely pleasing; but in those scenes where a display of dramatic power is necessary—particularly in the scene upon which the third act closes—Miss Jay falls short of the mark. A word of praise is due to Miss Isabel Clifton, who plays Mother Hunt. Mr W. H. Pennington, as Lord Spencer, appears to greater advantage than he did last week. The King William of Mr G. T. Minshull is a very clever and conscientious bit of acting; and Mr J. A. Meade is a good Scum Goodman. The other roles are fairly well filled, and the performance, as a whole, is very enjoyable. The piece is tastefully mounted and deserves large audiences. |

|||||||||||||

|

|

[Advert for Clancarty from The Glasgow Herald (26 September, 1881 - p.1).]

The New York Times (27 November, 1884) MISS HARRIET JAY. Miss Harriet Jay made her first appearance in America at the Madison-Square Theatre yesterday afternoon before a numerous audience. The play was Tom Taylor’s “Clancarty,” a romantic drama of the Jacobite days, and the supporting actors, members of Wallack’s and the Madison-Square companies most of them, were efficient, so that the performance was smooth and satisfactory. Miss Jay, of course, played Lady Elizabeth Clancarty, daughter of the Earl of Sunderland and wife of Donagh Macarthy, an adherent of the Stuarts. Miss Jay is a lady of stately presence, with an interesting face, and her methods as an actress were evidently derived from a careful study of good models. Her voice is sufficiently strong, though her utterance is lacking in variety of tone, and therefore somewhat monotonous. In moments of excitement Miss Jay’s speech is apt to be thick, as if her mouth were filled with pebbles. This defect, however, may be partly attributable to the nervousness due to her first appearance before a strange audience. As a whole, her performance yesterday produced a decidedly favorable impression, and it is safe to predict that this lady will always please in characters which do not demand too great a display of emotional power. Her Lady Clancarty is a sweet and lovable gentlewoman, more at ease while hearing good tidings of her absent husband from the lips of the pseudo Hazeltine than in the subsequent scenes of sorrow and despair. Her graceful manner and her earnestness, however, pleased everybody, and she was warmly applauded. Mr. Charles Glenny was Clancarty, and Mr. Thomas Whiffen, in an admirable make- up, Scum Goodman, the smuggler and cut-throat. Mr. J. W. Piggott contributed an effective sketch of the King, William of Orange, and Mr. E. J. Henley, of Wallack’s, was the stern brother of Lady Clancarty. ___

New-York Daily Tribune (27 November, 1884 - p.5) HARRIETT JAY AS LADY CLANCARTY. At the Madison Square Theatre, yesterday afternoon, a performance was given, for the benefit of a local charity, and Miss Harriet Jay appeared there, in the character of Lady Clancarty. Miss Jay is an actress, and likewise a writer, of repute in London.—The author of “The Queen of Connaught” and “The Dark Colleen.” Tom Taylor’s drama of “Clancarty” is not unknown to the play-going public of New-York. It was presented here some time ago by that intellectual, brilliant, impetuous actress, Miss Ada Cavendish, and later by Mr. George Rignold. It is based upon an episode in English history, set forth in some of the most interesting and brilliant of the pages of Macaulay, and it contains, at least, one scene of extraordinary power. Miss Harriet Jay was received in it with the kindly favor of a crowded and brilliant audience, and her effort was recognized with sympathy and sincere good will. Miss Jay is a handsome English blonde, with a fine, commanding figure, a high-bred, expressive face, a soft and pleasing voice, and decided dramatic talent, especially for the expression of playfulness and the glad enjoyment of sensuous feminine happiness. The interest inspired by her personality was much more real and earnest than that inspired by her acting. For pathos and passion her faculties of dramatic utterance seemed wholly untrained—so that her voice and action went all to pieces for want of government. She evidently knows how Lady Clancarty ought to be played—but the execution of her design was hampered in many ways. Miss Jay received numerous floral tributes and much applause, particularly at the end of the scene in the chamber. Mr. Piggott, acting King William gave a most interesting presentment of that monarch, when in his bereavement and feeble asthmatic condition, after the death of Queen Mary. Mr. Glenny acted Lord Clancarty and Mr. Whiffen, Goldman. ___

The New York Mirror (6 December, 1884 - p.2) Harriet Jay’s matinee last Wednesday at the Madison Square Theatre was only a moderate success. Lady Clancarty, the play selected for the occasion, is not especially serviceable for showing off the talents of a new-comer. And yet the few scenes requiring dramatic treatment were passed over rather lightly by Miss Jay, who, perhaps, was wise in not entrusting herself in a more trying role than that of the heroine of Tom Taylor’s piece. Miss Jay is tall and good-looking. Her pronunciation is refined and her manner ditto. But there is an awkward constraint in her movements and a weakness about her voice which combine to thwart her efforts to simulate the more intense emotions. Her acting was certainly dominated by intelligence. Indeed, we scarcely expected less from such an intellectual woman as Miss Jay. But if her performance of Lady Clancarty was a fair specimen of her abilities, we cannot predict success for the lady in the profession. The audience, which was composed chiefly of the fair sex, gave Miss Jay an attentive hearing, and whenever there was opportunity to show its good-will it applauded liberally. The real success of the matinee was made by Adeline Stanhope, who played the warm-hearted, gay and mischievous Lady Betty with a great deal of zest and spirit. Miss Stanhope is such an excellent actress in serious as well as comedy parts that we should like to see her retained as a fixture in one of our stock companies. Charles Glenny “got through” with Clancarty. There were so many delicate suggestions of blended humor and pathos in his personation of the sunny, chivalrous Irishman that we could see great possibilities for him if he had been entirely easy in the lines and business. Tom Whiffen was capital as Scum Goodman, and E. J. Henley, although he made Lord Spencer a trifle too heavy, nevertheless deepened the impression he recently made in Constance at Wallack’s. J. W. Piggott gave a dignity and character to King William which lifted the role into more prominence than usually is accorded to a straight utility part. Charles Coote, Mrs. Whiffen and M. Morton had minor duties to perform. _____

The Flowers of the Forest (Produced by Robert Buchanan, reviews are available in the Theatre Reviews section.) _____

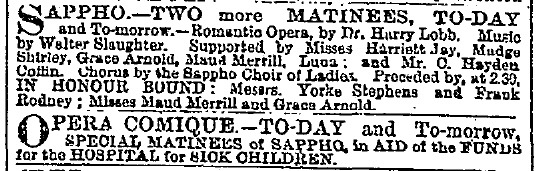

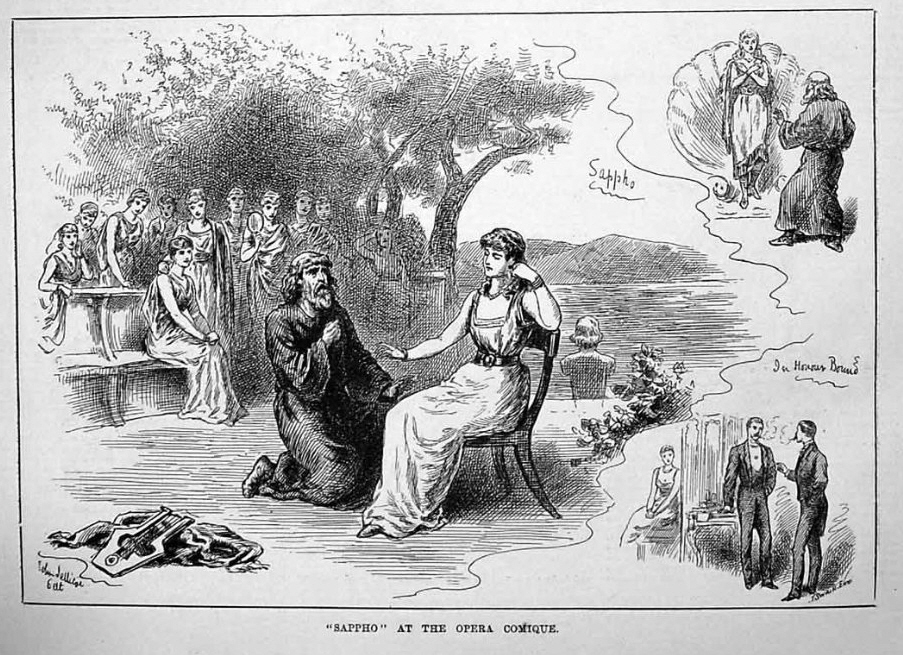

Sappho

The Era (30 January, 1886) As already announced, a romantic opera entitled Sappho, by Dr. Harry Lobb, music by Walter Slaughter, will be produced at the Opera Comique at three matinées, February 10th, 17th, and 18th. The opera is based upon the classic legend of Phaon and Sappho, and is in no way connected with M. Daudet’s Sapho, lately produced in Paris. Alma Tadema’s picture Sappho will be the scene of the tableau. Miss Harriet Jay will create the part of Sappho, and Mr C. Hayden Coffin that of Phaon. ___

The Stage (12 February, 1886 - p.13) OPERA COMIQUE. The first of a series of three matinées in aid of the funds of the Hospital for Sick Children, Great Ormond Street, Bloomsbury, was given here on the afternoon of Wednesday last, the 10th inst. The house was but poorly filled. The programme opened with Sydney Grundy’s one-act play, In Honour Bound, in which the best acting came from Mr. Yorke Stephens, who played well as Sir George Carlyon. Mr. Frank Rodney was the Philip Graham, Miss Grace Arnold acted Rose Dalrymple, and Miss Maud Merrill appeared as Lady Carlyon. The chief attraction of the afternoon was the production of a new lyrical romance, in one act, written by Harry Lobb, and composed by Walter Slaughter, entitled:— Sappho. Phaon ... ... ... Mr. C. Hayden Coffin This piece is supposed to represent the history of the connection of the licentious poetess, Sappho, with the boatman of Mitylene. The story accordingly opens with a chorus of girls in the train of Sappho, speedily followed by the entrance of the poetess herself, who, presumably tired of Lesbian delights, longs for the love of a man. The only man in Lesbos appears to be Phaon, the boatman, who, being old and ugly, is not unnaturally spurned by Sappho, who loves the young and beautiful. Phaon calls to his aid Venus, who gives him a girdle by means of which he can possess, so long as he retains the treasure, youth and good looks. Being transformed into a handsome young man, Phaon is sought after by Sappho. That person, however, is surrounded by a score of beautiful girls, to whom Phaon turns his attention, rejecting the hot passion of the poetess. “These girls are young, and know nothing,” pleads Sappho, in argument of her own charms. “It would be a pleasant task to teach them,” rejoins Phaon, and he immediately embraces, sings and dances with a couple of Sappho’s maidens. Sappho, despairing of ever gaining Phaon’s love, dashes herself off the Leucadian rock into the sea, and Phaon, having parted with his girdle and being restored to his old age, also throws himself into the sea, the piece closing with the ascent of Sappho and Phaon after Alma Tadema’s picture, “Sappho.” Whether it was a girdle or an ointment which Venus gave to Phaon is a point not worth disputing. But it seems pretty certain that Sappho and Phaon were together for some time when, Phaon tiring of Sappho, the latter threw herself into the sea, where she was not followed by Phaon. This, however, is a small matter when compared with the ludicrous nature of the dialogue furnished by Mr. Harry Lobb. What his lyrics are like we had no opportunity of judging, not being able to obtain a copy of the “book,” but his dialogue is sufficient to kill any musical piece, no matter how good may be the work of the composer. “Come, Sappho, give these girls a holiday,” says Phaon when he wants to be alone with Sappho, who herself talks—six hundred years before Christ—of “ménage.” It is also somewhat singular to find the Lesbian ladies quoting from Shakespeare. “Don’t ‘let concealment’”—says one damsel—“Yes, I know, ‘like a worm i’ the bud,’ but that’s not my way,” adds her companion. We could quote many other instances of incongruity and absurdity in the dialogue, but we have sufficiently indicated the weakness and futility of Mr. Lobb’s work. This failure is all the more to be regretted, because the music of Mr. Walter Slaughter is exceptionally good—it is nervous, dramatic, and it tells the story. By itself, it is a poem; allied to worthless words it loses half of its poetic charm. Miss Harriett Jay looked the character of Sappho, but the success of the afternoon was made by Mr. C. Hayden Coffin, whose voice was of great service to him. ___

The Times (12 February, 1886 - p.13) THE THEATRES. OPERA COMIQUE. A one-act musical piece called Sappho, by Mr. H. Lobb and Mr. Walter Slaughter, was produced at the Opera Comique on Wednesday afternoon for charitable purposes, and is to be repeated on several succeeding Wednesdays. It is not likely ever to be played for the purposes of general amusement, being, as regards its dramatic properties, extremely weak and amateurish. In the accounts of Sappho it is related that, being in love with Phaon and finding her love unrequited, she leapt down from the Leucadian rock. This incident, coupled with Phaon’s gift of youth from Aphrodite, furnishes the material for this so-called lyric romance, which appears to owe little or nothing to Mr. Lobb’s own invention. Sappho is surrounded by a bevy of nymphs, but the only prominent parts in the piece are those of the heroine and Phaon, which are played by Miss Harriett Jay and Mr. Hayden Coffin. The love interest is so meagre as to be practically non-existent, and the dénouement of the piece is involved in so much obscurity that it is hard to say whether a happy ending is secured or not, there being a species of tableau representing Sappho saved from a watery grave, with Phaon, who is restored to his original state, kneeling at her feet. The scene is a reproduction of Mr. Alma-Tadema’s picture of Sappho. For this story Mr. Walter Slaughter has provided a musical setting, but the librettist gives him no opportunity for rising above the level of commonplaceness. ___

The Graphic (13 February, 1886) “SAPPHO.”—Mr. Harry Lobb, the librettist of the “original lyric romance” Sappho, produced on Wednesday afternoon at the Opera Comique, has wisely not attempted to travesty the familiar legend. He has borrowed, from an earlier event in the history of the aged boatman of Mitylene, the pagan miracle of Phaon’s transformation into youth by Venus, and thus he is able to contrast the old man’s love for Sappho with the disdain the same man expresses for her after rejuvenescence. The character of Sappho is preserved almost as it has been handed down to us by the ancient writers. We see her surrounded by her maidens in the temple groves on the shores of the Ægean, we hear her inculcating in the minds of her fair disciples the powerful mission of woman, and in the course of the piece a realistic tableau is presented of Alma Tadema’s famous picture. Some violence is done to the legend in the dénouement, for after Sappho has leapt from the rock, Phaon springs after her, and both are brought up as a species of apotheosis at the feet of Venus, rising from the sea. The music, by Mr. Walter Slaughter, is of the simplest and most melodious character. As Miss Harriett Jay, who plays the heroine, is not a vocalist, Mr. Slaughter has made extensive use of mélodrame, Sappho declaiming the lines while the orchestra plays an accompaniment. The idea is not novel, but it is good, though it would have been far more effective if Mr. Slaughter had succeeded in investing his mélodrame with variety. Mr. Coffin was an excellent vocal Phaon, and the choruses were sung by a choir of lady amateurs, who gave their services for the benefit of the Hospital for Sick Children. ___

News of the World (14 February, 1886 - p.2) OPERA COMIQUE.—On Wednesday afternoon a special entertainment was given in aid of the Funds of the Hospital for Sick Children in Great Ormond-street, Bloomsbury, it being intended to repeat the same programme on Wednesday and Thursday afternoons next, with the similar deserving object. The performance began with Mr. Sydney Grundy’s little play In Honour Bound, which was very creditably acted by Miss Maud Merrill (Lady Carlyon), Miss Grace Arnold (Rose Dalrymple), Mr. Yorke Stephens (particularly good as Sir George Carlyon), and Mr. Frank Rodney (Philip Graham). The most important piece, however, was “a lyric romance” on the mythological story of Sappho, the words being by Mr. Harry Lobb, and the music by Mr. Walter Slaughter. For dramatic purposes some alterations have been made in the story, the old boatman Phaon receiving a temporary restoration of his youth, not for his services to Aphrodite, but as a special boon from the goddess, to be retained as long as he keeps her girdle, in order that he may win the love of the proud Sappho, who has rejected him as an old man in mean attire. When Sappho, on being slighted by the handsome young Greek, leaps from the Leucadian Rock into the sea, Phaon, who has previously given Aphrodite’s girdle to Fauna, a dancing girl, and has again become old, joins the poetess in death. Mr. Slaughter’s music is quite in keeping with the refined tone of the legend, and he employs with good effect the mélodrame device of instrumentally accompanying the blank verse speeches of the heroine, who, strange to say, is not called upon to sing. With the exception of Phaon (a baritone) all the characters are females, including the chorus. Miss Harriett Jay played with much grace and feeling, and recited her lines with elocutionary point, whilst Mr. C. Hayden Coffin as Phaon did ample justice to Mr. Slaughter’s agreeable airs. Miss Luna was the dancing Fauna, and other parts were allotted to the Misses Madge Shirley, Grace Arnold, and Maud Merrill, the lady chorus, it was understood, consisting of amateur helpers to the good cause, who executed their task with much intelligence. An admirable orchestra was conducted by the composer. The piece was nicely placed upon the stage, and was exceedingly well received. |

|||

|

|||

|

[Adverts for Alone in London and Sappho from The Times (17 February, 1886 - p.8).]

The New York Mirror (20 February, 1886 - p.11) London Gossip. LONDON. Feb. 6. . . . Speaking of elocutionists Edwin Drew, a most competent elocutionist, has brought about a capital idea in the shape of “The First Charles Dickens’ Birthday Celebration,” for next Monday at Free Masons’ Hall. It will consist of an entertainment of selections only from Charles Dickens, to be followed by a “Fancy Costume Ball,” in which the characters are entirely from Dickens’ novels. The patrons include the names of Rev. and Mrs. Compton Reade, Mr. Terriss, Professor Plumptree and Mrs. Kendal. Among the costumes of guests are to be those of Nancy, Rogue Riderhood, Newman Noggs, Ralph Nickleby, John Browdie, Squeers, Smike, Jeb Trotter, Old Weller, Jo, Fagin and Bill Sikes. Numbers of theatrical folks are expected to be on hand. Harriet Jay will be there, it is rumored, if her engagements will permit. ___

The Era (20 February, 1886) MISS HARRIET JAY on Wednesday met with a injury to her ankle, which prevented her appearance in Alone in London, at the Olympic, and in Sappho, at the Opera Comique matinée, on Thursday. On Thursday Miss Jay’s place at the Olympic was taken by Miss Adah Cox. |

|||

|

|

[From The Illustrated Sporting and Dramatic News (20 February, 1886).]

The New York Mirror (6 March, 1886 - p.9) London Gossip. LONDON. Feb. 13. The friends of Harriet Jay, the well-known novelist and actress, assembled in large numbers on Wednesday at the Opera Comique on the Strand to see the lady in the classic role of Sappho, at one of the morning performances to be given in the “sweet name of charity.” The object was a most worthy one— namely, to increase the funds of the “hospital for sick children” in Great Ormond street, Bloomsbury. Thus set forth the bills. By the way, who ever heard of a hospital for well children. ___

The Referee (20 March, 1887 -p.3) I may say that “one Lobb” writes me a pleasant and humorous letter, from which I learn that he is one of several Lobbs, and that his front name is Harry. Aha! I know him now. He gave off an imitation Greek play called “Sappho” last year, which was creditable to his culture, but had no money in it. Also Mr. Lobb is an electrician. The new Comedy manager might therefore do worse than turn Lobb on to put some light into “The Red Lamp.” |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|