|

Play List: 4. Corinne 7. The Mormons 9. Lucy Brandon 10. Storm-Beaten 11. Lady Clare 13. Bachelors 14. Constance 15. Lottie 16. Agnes 17. Alone in London 18. Sophia 19. Fascination 20. The Blue Bells of Scotland 21. Partners 24. Angelina! 25. The Old Home 26. A Man’s Shadow 27. Theodora 29. Clarissa 30. Miss Tomboy 32. Sweet Nancy 33. The English Rose 36. Marmion 37. The Gifted Lady 38. The Trumpet Call 39. Squire Kate 40. The White Rose 42. The Black Domino 44. The Charlatan 45. Dick Sheridan 47. Lady Gladys 48. The Strange Adventures of Miss Brown 49. The Romance of the Shopwalker 52. Two Little Maids from School ___ |

|

ROBERT WILLIAMS BUCHANAN (1841 - 1901) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

THEATRE REVIEWS 18. Sophia (1886)

Sophia September, 1887: Thomas Thorne purchases the sole rights of Sophia in England, America, and the Colonies, for £600. |

|

|

[Programme for the first run of Sophia at the Vaudeville Theatre, April, 1886.] |

|

|

[Programme for the 200th performance of Sophia at the Vaudeville Theatre 15th January, 1887.] |

|

|

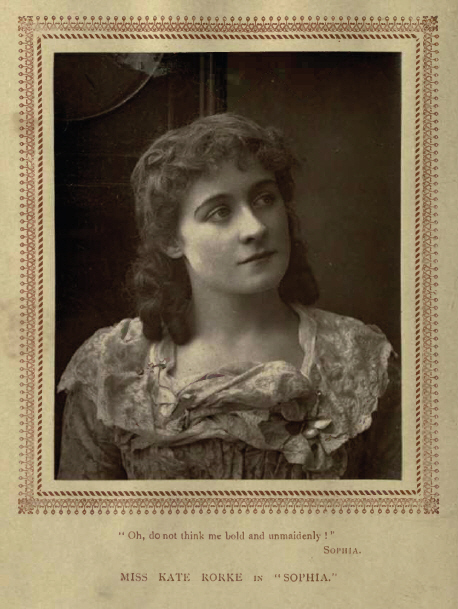

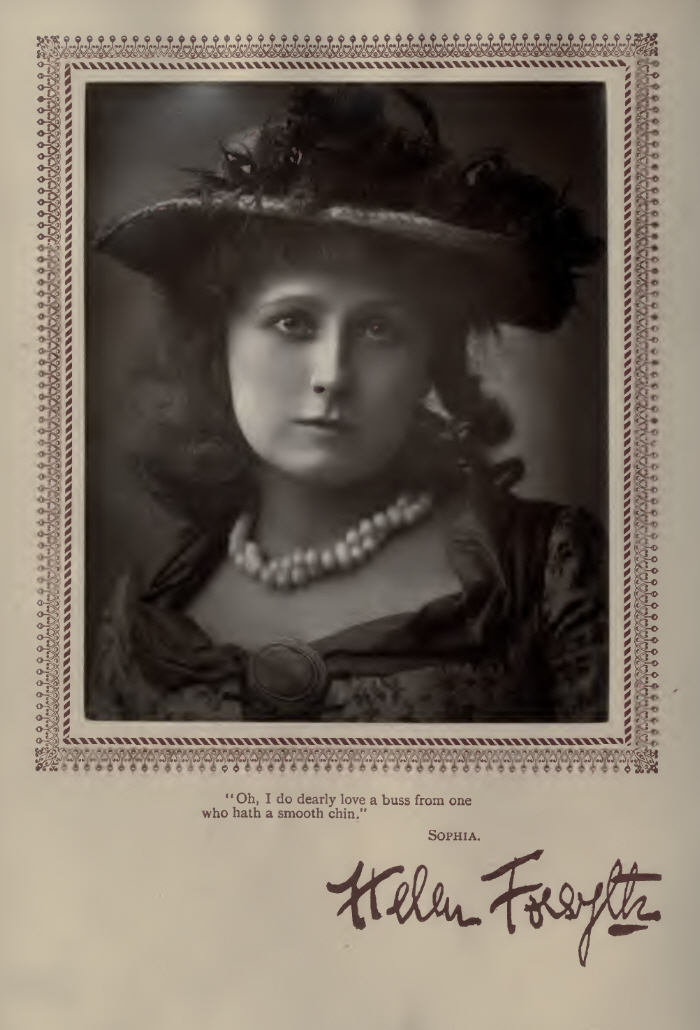

[Kate Rorke as Sophia from The Theatre (1 February, 1887).]

The Glasgow Herald (29 March, 1886 - p.7) Mr Robert Buchanan’s new drama, now on rehearsal at the Vaudeville, is founded on the interesting story of Fielding’s novel “Tom Jones.” The principal character will be Partridge, played by Mr Thorne, Squire Western falling to his brother Mr F. Thorne. Miss Sophie Larkin will play Miss Western, Miss Rose Leclerc the Lady Dellases, and Mr Ackhard the philosopher Square, the hero and heroine falling to Mr Charles Glenny and Miss Kate Rorke. Molly Seagrin has, of course, been struck out of the play. ___

Daily News (5 April, 1886 - p.3) The management of the Vaudeville Theatre have determined to produce Mr. Buchanan’s “Sophia,” at a morning performance, to be given on Monday next. This will be the first attempt to treat Fielding’s novel seriously on the stage. Joseph Reed’s “Tom Jones,” brought out at Covent Garden in 1769, comprised but few of the characters, and even excluded Partridge, who is to be played by Mr. Thomas Thorne, and will be a prominent personage in the Vaudeville piece. The older play is described as “wanting in incident,” a fault certainly not due to lack of material; and we are told that in the endeavour to make Jones more amiable and interesting, the author “contrived to reduce him to a mere walking gentleman.” Reed’s piece was furnished with songs, and was, in fact, an adaptation of Poinsinet’s opera, brought out with Philidor’s music in Paris a few years earlier. In the latter piece Dowling the Quaker furnished the grotesquely humorous element. A new adaptation of “Tom Jones” ought not to miss the excellent opportunities the story affords for scenery and costumes illustrative of English localities and manners in the days of George II. If the Western of the cast were equal to the task it would be well worth while to introduce Philidor’s famous hunting song. ___

Daily News (12 April, 1886 - p.6) Apropos of our recent observation that Mr. Robert Buchanan’s “Sophia” will be the first attempt to treat Fielding’s novel “seriously on the stage,” Joseph Reed’s old opera including but few of the characters, Mr. William Archer writes: “I have lately been looking over some Adelphi playbills, and find announced for Monday, the 9th of February, 1824, by permission of T. Dibdin, Esq., the burletta of ‘Tom Jones; or, the Foundling,’ with a very large cast of characters, including all the chief personages of the novel.” From the memoirs of Thomas Dibdin we gather that he brought out this piece at the Surrey Theatre about 1818. It is described by him as “an operatic burletta in three acts,” and is stated to have been produced as an afterpiece. Dibdin adds that it became a stock piece, and elsewhere he says, “My proposed system of dramatising popular classic novels, as ‘Tom Jones,’ ‘Roderick Random,’ ‘Humphrey Clinker,’ &c., having appeared to be successful, a similar plan was immediately adopted at the Coburg,” so that it appears that there was yet another “Tom Jones” in the field. ___

The Sheffield Daily Telegraph (12 April, 1886 - p.2) The dramatists of the day are killing first-nighting, which has grown a quite fashionable pastime. Since the Prince of Wales made a practice of witnessing the first production of new plays at certain houses the smart people have hankered after seats on those occasions. The world likes to see its celebrities, many of whom are to be found at home in the stalls of a theatre on the first night of a play. Latterly the harmonias of first-nighting have been marred by boisterous demonstrations made by the gods in the gallery and demons in the pit. The consequence of this has been that actors, naturally nervous in their new parts, are made more timid by fears of disturbance. To escape the scoffs and jeers of these boisterous critics, new plays are now experimented upon before friendly audiences at matinees. Mr. Thorne, of the Vaudeville Theatre, has had unpleasant experiences of first night audiences. He has therefore decided to produce Mr. Robert Buchanan’s “Sophia” on Monday afternoon. Great things are spoken on behalf of this piece, which is an adaptation of Fielding’s famous novel, “Tom Jones.” ___

Daily News (13 April, 1886 - p.5) “TOM JONES” AT THE VAUDEVILLE. Mr. Buchanan has not achieved the superhuman feat of putting Fielding’s voluminous novel upon the stage; but he has been able to present a fair outline of its story, suppressing or modifying with considerable tact its grosser features, while boldly and ingeniously seizing upon every opportunity that has arisen for developing dramatic situations. In so doing he has brought before us nearly all the leading personages; and though he has availed himself but little of the novelist’s dialogue, and has found it expedient to place some of Mr. Jones’s licentious adventures upon the shoulders of his insidious rival, Blifil, and to add a darkening touch to the portrait of Lady Bellaston, the relations of the parties remain substantially the same. It is more to the purpose, however, that the author of “Sophia” has produced a thoroughly- interesting play. Its four acts, including the time occupied in the construction of one or two substantial set scenes, occupied yesterday fully three hours; but the performance had secured from the first the sympathy of the audience, and at no point did the interest flag, until at the conclusion of the rhymed “tag” the curtain fell amidst a demonstration of satisfaction that no experienced eye or ear could have confounded with the languid approval which a complaisant afternoon audience will occasionally bestow upon works of little merit. The play has the great advantage of being admirably acted. Mr. Glenney’s Tom Jones is no doubt a more romantic personage than our old acquaintance of that name, and he is a trifle given to swagger and to dispense smiles of affability, but still he is a young man of spirit and such a one as the lovely Sophia, who is played by Miss Kate Rorke with great charm and sweetness and in the prettiest of Georgian costumes, might well be supposed to prefer to the smooth, intriguing, insinuating Blifil. Partridge in the play is also not quite the Partridge of the novel. As the action does not commence till the hero has arrived at manhood the worthy barber’s original pursuit is not impressed on the mind of the spectator, and hence his scraps of Latin have a more incongruous air; but the honest simplicity of the barber, and the unbounded trustfulness and admiration with which he regards Tom Jones, whose fate he shares, are brought into strong and agreeable relief by Mr. Thomas Thorne. A superadded touch of the humours of Caleb Balderstone, in the scene in which these twain are supposed to be suffering penury in the London garret, is not unwelcome; and there is genuine pathos in the tones in which the old man responds to Jones’s angry dismissal by offering to sit on the stairs until his companion’s vexation has passed. It is long since Mr. Thorne has been provided with a character filled in with so many pleasing contrasts, and so thoroughly acceptable to his audience. A capital portrait of the coarse, roaring, self-willed, but good-hearted Squire Western is furnished by Mr. F. Thorne. The character, however, is necessarily thinner in substance than in the book; though it is not quite so attenuated as Mr. Allworthy, who, however, so far as anything remains of that Somersetshire worthy, is efficiently represented by Mr. Gilbert Farquhar. Miss Sophie Larkin’s Miss Western is highly diverting, as are most of this amusing actress’s impersonations, though the severe dignity of that conscientious student of the Gazettes has somehow evaporated. Very clever impersonations of the waiting-woman, Honour, and the redoubtable village flirt Molly Seagrim, by Miss Lottie Venne and Miss Helen Forsyth respectively, have also to be noted. Miss Rose Leclercq, resplendent in hoops and furbelows and diamonds, played with great force and effect the part of Lady Bellaston. Square, we may note, is adroitly represented by Mr. Akhurst, though the total disappearance of his old friend and fellow-disputant Thwackum necessarily reduces him to rather shadowy proportions. Mr. H. Akhurst, who played the part of Blifil, has, if we mistake not, been hitherto unknown to the London stage. His performance was remarkable for its moderation, its ease, its high finish, its total freedom from all unworthy means of winning applause. So chaste a style is apt to seem wanting in force and colour; but it is certainly not so in this case. It would be absurd to call Mr. Akhurst young, though he appears to be a promising actor. As someone wittily observed, an actor should not promise but perform, and this Mr. Akhurst does in the very best sense of that expression. Sophia, we may take it, will quickly find its way to the evening bill. Its simple old-fashioned story, compactly and dramatically set forth, its adroitly contrived situations, and its pleasing glimpses of old manners render it a welcome relief from the strong excitements of melodrama. ___

The Morning Post (13 April, 1886 - p.5) VAUDEVILLE THEATRE. Mr. Robert Buchanan’s comedy “Sophia,” founded upon “Tom Jones” and produced at this theatre yesterday afternoon, is not the first stage version of Fielding’s famous novel. The earliest on record was a musical adaptation—a comic opera, based by the eccentric rope-maker, or “halter-maker” as he delighted to style himself, Joseph Reed, upon the lines of the French “Tom Jones,” also an opera, written by M. Poinsinet, in 1765. The English piece was brought out at Covent Garden on January 14, 1769; but though it had considerable merit, and was excellently acted by Shuter, Mattocks, Green, Pinto, and other players celebrated in their day, it does not appear to have been received with much favour. The Gallic dramatist was so fastidious that he went to the trouble of legitimating the hero; the British left him as he had found him, a foundling, but “stripped him of his libertinism to make him more amiable and interesting.” “Tom,” wrote a contemporaneous critic, was “by this supposed amendment reduced to a mere walking gentleman.” And there lies the great difficulty with which the writer has to contend who would tone down the joyous, exuberant personages of old- world fiction to the tame standard of modern taste. There is ever the danger that through the “Bowdlerizing” process they may lose in vigour and spirit more than they gain in elegance and propriety. But there is no help for it. The experiment must be made. The wild, rough tide of animal spirits which foams and flashes through the comedies and romances of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, like a vehement river through a bold landscape, must be reduced to a smooth and quiet but bright and pure current to suit the social manners of an age which, if not more moral, is at least more sober and decorous than its predecessors. ___

The Standard (13 April, 1886 - p.5) VAUDEVILLE THEATRE. Although there was no performance at the Vaudeville Theatre in the evening, Mr. Thorne, the manager, chose yesterday afternoon for the production of a new piece, a composition founded on “Tom Jones,” by r. Robert Buchanan. It is impossible to read Fielding’s book without perceiving that it contains the material for a play. There is a the honest, straightforward hero, with those manly faults which do not destroy esteem, and he is misunderstood as heroes should be in order to provoke sympathy, His rival is a despicable and hypocritical creature, who seeks the hand of the heroine; and thus Tom Jones, Blifil, and Sophia are ready to the playwright’s convenience. An eccentric figure is provided in Partridge, the barber; a pert waiting maid in Mrs. Honour, and the book contains an assortment of minor characters, who may be usefully brought in to those incidents which the compiler selects. Fielding, in fact, supplies an effective outline which is here borrowed, with some rather crude joins here and there, where the original is departed from. Mr. Buchanan makes a very unnecessary statement when he records on the bill that “whatever merit the play may possess belongs to him whose supreme genius inspired it; for whatever shortcomings it may show, the dramatist is alone to blame;” for there can be no danger that Fielding’s novel will be judged from Mr. Buchanan’s play. Among these shortcomings is the fact that in the course of transference to the stage Fielding’s characters have lost their freshness, brightness, and vigour. The reason is not far to seek. The personages bear the names which Fielding gave them, and they talk the language which Mr. Buchanan puts into their mouths. This at times does well enough for the furtherance of the familiar plot which has been extracted from the novel; only it is not Fielding. If the famous names were not retained little harm would be done; but it will be difficult for those who really appreciate the great English novelist’s story to avoid feeling that an outrage has been committed by the playwright who presumes to seize upon characters so vivid and firmly stamped as these and adopt them for his own—with variations. It would have been far better had Mr. Buchanan taken Fielding’s plot—if it were necessary that ti should be taken—admitted as indebtedness, and renamed the dramatis personæ. ___

The Daily Telegraph (13 April, 1886 - p.5) The best possible proof of the difficulty of dramatising “Tom Jones” is that “Tom Jones” has never been dramatised. We cannot, of course, accept the triding burlettas and episodical sketches dimly connected with Fielding’s immortal classic as standard plays in any popular sense. Until Mr. Robert Buchanan took the famous foundling under his wing, and determined to introduce him to the footlights, “Tom Jones,” to the ordinary playgoer, was non-existent. All the more credit, therefore, to Mr. Buchanan for the happy result of yesterday afternoon. The play proved interesting, the players were applauded with sincerity, up to a certain point it seemed as if Mr. Buchanan had cracked a very hard nut with boldness and effect, the author was called, Mr. Thorne was congratulated, and it was evident to the least partial playgoer that all present had been amused at what they heard and what they saw. The dramatist has contented himself with telling the life-story of a singularly unfortunate young man, who in his boyhood is very handy with his fists, and in his manhood almost too ready with his tears. The dramatic Tom Jones is the incarnation of virtue. He has a certain feverish propensity for kissing, it is true. But that is all. He kisses Mrs. Honour because he rises from the table refreshed with good wine, and would kiss her grandmother were she present at that moment. He kisses Molly Seagrim for old acquaintance sake, merely because they had gone blackberrying together as children; he would like to kiss Sophia Western uncommonly well, if he only dared; and he is kissed by Lady Bellaston simply because he could not help it, and could scarcely resist the attack. Apart from this osculatory fever Tom Jones is personified innocence. Mr. Robert Buchanan has generously forgotten and forgiven his every sin. This pretty fellow, this merry gentleman is merely the victim of ungenerous fate of most untoward circumstances. That little affair with Lady Bellaston in the neighbourhood of Hanover-square is not even hinted at. Tom Jones would not accept money from a lady of fashion in exchange for her favours, not he; he would scorn the action. Butter would not melt in the mouth of the bowdlerised foundling. As to Molly Seagrim, his old play-fellow inn the good old country days, our hero would scorn to follow in the footsteps of that arch humbug, Mr. Philosopher Square, and all allusion to the adventures in the inn is courteously omitted by the latest chronicler of the fortunes of Tom Jones. We must forget very much Fielding when we see “Sophia,” we must forgive very much human nature when we renew our acquaintance with the reformed rake, we must sigh over many a lost passage of a delightful book when we see it presented on the stage; but then, on the other hand, it is only fair to remember that if the dramatist had dared to paint human nature as Fielding painted it, to call a spade a spade as Fielding called it, to describe the viciousness and meanness of Tom Jones as well as his undergrowth of sincerity, the scented depravity of Lady Bellaston with her pandering and profligacy, the horrible degradation of Molly Seagrim, the licentious Pharisaism of Mr. Square, it is certain that Fielding would never have been foreshadowed in a play, and an audience would have been denied the pleasure that it unquestionably received yesterday. The classic, as we read it in the book, can never be presented on the stage, be it pure or coarse. “Olivia” is but a story of episodes from Goldsmith’s “Vicar of Wakefield,” just as “Sophia” is a series of suggestions from “Tom Jones.” An audience likes to see a reckless, high-spirited young man persecuted by an untimely fate, over-ridden by a canting hypocrite, discarded by a Puritanical old gentleman, watched over by a simple-minded and faithful friend, animated to energy and enthusiasm by a fond woman, and eventually clearing himself from every speck of mud that sticks to his coat. We can never have on the stage the real Tom, the true Sophia, the accurate Lady Bellaston, the genuine Molly Seagrim, the proper Squire Allworthy or Squire Western, but the dramatist must be forgiven for not attempting the impossible. He has told the old story of Charles and Joseph Surface in another form and with the puppets of another class, he has contrasted virtue and hypocrisy, he has intermingled humour and sentiment, he has in a word interested and amused his audience. Let any one take down Fielding’s “Tom Jones” from the bookshelves and then he will see the difficulty that Mr. Buchanan has attacked with such determination. We can all be wise after the event, and say what ought and what ought not to have been done; but to adapt “Tom Jones” to the tastes and the scruples of a nineteenth-century audience was no easy task, and the cheers of yesterday show that the dramatist has gone very far towards solving a difficult problem. ___

The Times (14 April, 1886 - p.4) VAUDEVILLE THEATRE. “First nights” at the Vaudeville having of late been more or less disastrous to the management, the new piece which has been prepared for this theatre by Mr. Robert Buchanan in the shape of an adaptation of Fielding’s novel of “Tom Jones,” was on Monday put forward in a purely tentative fashion at a matinée. The precaution proved, as it happened, to be uncalled for. The piece was in every respect successful, and would undoubtedly have met with a cordial welcome at the hands of the ordinary first night audience, whose so-called organized opposition to certain new plays is, we are convinced, purely a managerial fantasy. Mr. Robert Buchanan calls his adaptation Sophia. Why it should not have been called Tom Jones it is hard to say, for Tom Jones is as much the hero of the play as of the novel. Various as have been Mr. Robert Buchanan’s contributions to the stage, there can be little doubt but that this is his happiest effort in play writing. It is rare indeed that we find a purely English comedy so wholesome, so stirring, so interesting, and so full of human nature as Sophia. In dealing with Fielding’s romance, the author’s plan of action has been to set forth succinctly and consistently the love-story of Tom Jones and Sophia Western as complicated by the perfidies of Blifil and Lady Bellaston. Every incident not directly bearing upon this has been omitted, the result being four acts of highly dramatic material, tending towards a definite and, indeed, an inevitable dénouement—namely, the union of Tom Jones and Sophia and the discomfiture of their enemies. Mr. Robert Buchanan has wisely refrained from taking liberties with his author except on one or two minor points. In the play Square is a very estimable gentleman, whose only fault is susceptibility to the mature charms of Squire Western’s sister; it is Blifil who conducts the illicit amour with Molly Seagrim of which Tom Jones for a time incurs the odium, while Lady Bellaston’s overtures to the hero are only such as to entitle her to be described as an impressionable lady. Mr. Robert Buchanan in a playbill note claims credit for having eliminated every offensive element from the story, and not only may the claim be allowed, but it may be added that he has at the same time done full justice to his author’s genius so far as concerns the delineation of character and the conflict of the generous and the sordid motives of human nature. The weak point of the play, as presented at the Vaudeville, is that it affords but small opportunity for the display of Mr. Thomas Thorne’s comic powers as Partridge, the barber, who is rather an excrescence upon the action than otherwise. On the other hand, that excellent young actress, Miss Kate Rorke, has never been seen to better advantage than in the part of Sophia Western, who in the play as in the novel is perhaps the most lovable type of womanhood ever depicted in fiction. Her scenes with Mr. Glenney, as Tom Jones, are delightfully true and refreshing. Mr. Glenney might look the character better, but he plays with adequate manliness and vigour. Miss Larkin contributes with Mr. Thorne to the humours of the story in her own inimitable fashion by combining girlish artlessness with the mature charms of spinsterhood; Blifil’s hypocrisy is cleverly brought out by Mr. Carleton; Mr. Fred Thorne is a sufficiently vulgar, though perhaps somewhat too noisy representative of Squire Western; Mr. Gilbert Farquhar makes a smug Mr. Allworthy; and Miss Helen Forsyth plays picturesquely and intelligently as Molly Seagrim. In the minor parts of Seagrim and Square, Mr. Mellish and Mr. Akhurst are also deserving of commendation. The piece, in short, is admirably played and mounted, and placed in the evening bill, it will no doubt effectually revive the languishing fortunes of the theatre. ___

The Liverpool Mercury (14 April, 1886 - p.5) Mr. Robert Buchanan has made a dramatic success at length, which is likely to bring him good fortune. He has done what one would have thought impossible. He has dramatised Fielding’s “Tom Jones,” and in fitting the story for the stage, though he brings Lady Bellaston and Molly Seagrim on the boards, he has made it presentable to a nineteenth century audience. Tom Jones becomes as reputable a character as Pendennis or David Copperfield. He has his little weaknesses, but they are the exuberance of a generous youth. Lady Bellaston, instead of being a monster of vice, is only a little too prone to kiss Tom when she gets the chance. Molly Seagrim is not at all the character of the novel. In fact, everybody in the play is nice and good. But the piece is not dull; it is quite bright and cheery. It has fine dramatic points. It has excellent character sketches. Squire Western is, perhaps, a little too boisterously played, but that is not the author’s fault. Allworthy, Blifil, Mrs. Honour, and all the rest of them come upon the stage and remind one distantly of the book—not a good book but a great book—which every Englishman has read, and which is produced in a fresh edition nearly every year. ___

The Stage (16 April, 1886 - p.14) VAUDEVILLE. On Monday afternoon, April 12, 1886, was produced here a new comedy, in four acts, founded on Fielding’s “Tom Jones,” by Robert Buchanan, entitled:— Sophia. Tom Jones .......................... Mr. Charles Glenney The difficulty of adapting a successful novel for the stage has seldom been so clearly evinced as in this, the first serious attempt to place the world-famous story of “Tom Jones” in a dramatic framework. The novel reader generally forms his own ideal of the characters in a book, and herein arises the first stumbling block in the path of the adaptor, who must not only try to faithfully reproduce the characters as they have been conceived by their author, but he must endeavour to satisfy each individual spectator of these personages as transferred from the book to the stage. An additional difficulty has been presented in the present case, where the nature of manners and customs of a bygone age render the task of exact reproduction of characters and incidents well-nigh impossible. Such, we may remind our readers, was the coarseness displayed in Henry Fielding’s great work that its appearance in Paris was at first prohibited, and readers of “Tom Jones” will readily recall incident after incident, scene upon scene, and dialogue illimitable that could not possibly be presented to the playgoer of to-day. The vices and folly of our age are much the same as when Fielding wrote, but they are more carefully hidden, more adroitly concealed. To quote Mr. Buchanan’s prologue, “Modes of speech have now grown nicer; Folk, if not purer, are at least preciser.” It was obvious that no minute photograph of Fielding’s characters could be attempted now, but Mr. Buchanan has gone, as we think, a little too far in the purifying process. He has whitewashed the principal character with a vengeance. The adaptor confesses that “he has taken leave to purify the character of the hero somewhat.” He has, indeed; and he has left him Tom Jones in name only. A similar process has been pursued in regard to most of the other characters presented in the adaptation, which are but distantly allied to those in the novel. Readers of Fielding will on this account be disappointed in the play. The adaptation, however, possesses much to commend it. It is chiefly concerned in relating the story of the love of Tom Jones for Sophia, and, as such, the story is told well enough. The piece is neatly constructed, and the action is progressive and interesting throughout the first half. Thereafter it falls off, and it is felt that the conclusion is lamely and clumsily continued. Nor is the dialogue written in the best possible manner, and the listener is frequently compelled to wish that Mr. Buchanan had allowed Fielding’s own words to be occasionally heard. Despite its faults, Sophia shows a successful solution of a difficult task, and should win popular favour. The first act takes place before Squire Western’s house. Its incidents comprise the declaration by Tom Jones of his affection for Sophia, his defence of George Seagrim, and his thrashing of the hypocritical Blifil. The action of the second act takes place at first within, and latterly without the barber’s shop, where Partridge is introduced. It concludes effectively with the flight of Sophia to London. Lady Bellaston is introduced in the first scene of the next act where Tom Jones appears to have lost all spirit, and is shown white-faced and snivelling. A “garret in London,” where Tom Jones hides Mrs. Honour, Lady Bellaston, and Sophia, one after the other, and the scene of which is very like a French farce in its arrangement, concludes the act. Sophia renounces Tom Jones, and declares her intention of allowing her father to dispose of her as he will, a dramatic scene as it stands, but one that would be still stronger if Sophia were entrusted with a speech of greater power and impressiveness. In the final act the course of true love is made to run smoothly at last. Blifil is unmasked, and the impulsive Jones is restored to the arms of the forgiving Mr. Allworthy. The play, as a rule, is admirably acted. Mr. Charles Glenney plays the hero with dash, vigour, and in a fine manly style. He is better suited in the first part of the piece than in the latter, where the silly sentiment of the part naturally hampers an actor of a robust style. There could not be a better Blifil than Mr. Royce Carleton, at once smooth, polished, insinuating, and without the slightest trace of exaggeration. Mr. Gilbert Farquhar’s rendering of Mr. Allworthy is excellent, and by far the best impersonation we have yet seen him give. Mr. Fred Thorne has a good idea of Squire Western, but he was far too noisy on the occasion of the first performance. [Note: the next passage was illegible and has been omitted.] Kate Rorke [....] when momentarily believing Tom Jones to be worse than he really is, and consequently resigning herself to her father’s wishes, was also admirably expressed by the actress, who gives a consistent, pretty, and winning rendering of the character. Another hit is likewise made by Miss Helen Forsyth, a young actress who does now hesitate to sink her natural refinement of manner and her grace for the proper portrayal of the rustic Molly Seagrim, as the part is drawn by the adaptor. It is a very able sketch of character, and should go a long way in securing Miss Forsyth a permanent place on the metropolitan stage. Miss Lottie Venne is just as pert and pleasing as ever as Mrs. Honour; Miss Sophie Larkin is amusing as Mrs. Western; and the cast is completed by Miss Rose Leclercq, a handsome Lady Bellaston. No piece has been so well dressed or mounted at the Vaudeville for a considerable time as this. The costumes are by Miss Fisher and Messrs. May and Co., and the scenery has been supplied by Messrs. Perkins, Bruce, Smith, and Helmsley. A brilliant audience, including Mr. Henry Irving, Mr. W. S. Gilbert, and Mrs. Langtry, witnessed the first performance. Sophia was placed in the regular bill of the theatre on Tuesday evening, and there are every signs of its enjoying a successful career. ___

The Era (17 April, 1886) THE LONDON THEATRES. In the dramatic chronicle of the week the most notable event has been the production of Mr Robert Buchanan’s version of Fielding’s novel of “Tom Jones,” which, produced on Monday at an afternoon performance, has been since played every evening at the VAUDEVILLE, under the title of Sophia. At the LYCEUM Faust has now passed its hundredth night. With this week The Private Secretary closes its prolonged career at the GLOBE. Called Back at the GRAND now gives place to Adam Bede. At the BRITANNIA Miss May Holt has appeared in her drama called Every Man for Himself. The PAVILION has reproduced Rail, River, and Road. The ELEPHANT AND CASTLE has furnished a new version of Sweeney Todd, the Demon Barber of Fleet-street. The STRATFORD, East London, has represented the drama called My Partner, and at the PRINCE OF WALES’S, Greenwich, Miss Helen Barry has appeared in Led Astray. THE VAUDEVILLE. Tom Jones .......................... Mr CHARLES GLENNEY The Vaudeville management has had more than one slice of good luck in connection with morning performances, and more than one disaster in connection with “first nights.” It was not surprising, therefore, even if inconvenient, to find that Mr Thomas Thorne had decided to bring out Mr Robert Buchanan’s adaptation of Fielding’s “Tom Jones” at a matinée. Matinée audiences are, as a rule, amiably disposed, and in no way severely critical, and so, if we cannot credit manager and author with courage, we can give them excuse on the score of expediency. It has been very properly stated that Mr Buchanan has made the first attempt to treat Fielding’s novel seriously for the stage. Tom Jones, by Joseph Reed, produced at Covent-garden in 1769, was but a weak affair, and we are told that the author, in the attempt to make the hero more amiable and interesting than he originally was, contrived to reduce him to a mere walking gentleman. In Reed’s piece songs were introduced, and it was really an adaptation of Poinsinet’s opera, produced in Paris a few years before. We are reminded of another adaptation by Thomas Dibdin, brought out at the Surrey about 1818, and taking the form of an operatic burletta in three acts. Mr Buchanan, like Mr Reed, has made his hero more amiable and virtuous than he originally was; but, in subjecting him to a moral whitewashing, he has not exposed himself to the charge brought against his predecessor. The Vaudeville Tom Jones is a real flesh and blood hero, full of life and full of vigour, and he is none the less interesting because his virtues are made more prominent than his vices. In an “author’s note,” Mr Buchanan says, “Although the leading characters and incidents of this comedy are based on the greatest work of our first and greatest satirical novelist, care has been taken to select only what is perfectly stainless and void of offence. Despite a certain taint, which is coarseness rather than immorality, ‘Tom Jones’ has gained its immortality as a work of art because it is fundamentally right and pure in its pictures of human nature. The reader who discovers in it coarseness only would have to close the works of Cervantes and Le Sage, as well as those of Chaucer, Shakespeare, Dryden, and Molière. In the present play the author has tried to preserve Fielding’s healthy moral (which Sheridan also preserved when copying from the novel the characters of Charles and Joseph Surface), although he has taken leave to purify the character of the hero somewhat, to alter many of the incidents, and to invent others.” Mr Buchanan further claims that almost all the dialogue and the leading situations are original—so far, at least, as anything can be original, which is in no true or absolute sense the dramatist’s own, but the merest echo of a great master; and he modestly adds that whatever merit the play may possess belongs to him whose supreme genius inspired it, and that for whatever shortcomings it may show the dramatist is alone to blame. We may as well say at once that Monday’s audience recognised no shortcomings, that they discovered many merits, and that for these they were quite ready to give all the praise to the living author, whose work afforded unmixed enjoyment, and who was called at the end to receive the assurance of success in the enthusiastic plaudits of a crowded house. Friends! in the quaint old fashion flown away, Full seven score years! Tho’ far man’s feet have ranged You guess, from this, Love is to-day our theme? And if, while tricking for our modern stage ___

The Athenæum (17 April, 1886) DRAMA THE WEEK. VAUDEVILLE.—‘Sophia,’ a Comedy in Four Acts. Founded THE difficulties which have hitherto preserved the masterpieces of Fielding from serious attempt at dramatization are the same which have sheltered in later days the novels of Thackeray. Where the key-note to a novel is satire, however gentle and however blended with humour, the task of the adapter and that of the exponents he employs are arduous enough to daunt the boldest. It may be doubted whether any novel in the language is less suited to dramatization than ‘Tom Jones.’ Based upon the old conception of a novel as transmitted through the masterpieces of Cervantes and of Lesage, it was designedly and avowedly adorned by Fielding with all the wit and wisdom he possessed. Full of adventures often of the briskest and most diverting kind, it is not a novel of adventure; and revealing a power of characterization unequalled since the days of Shakspeare, it is not principally a novel of character. It is, indeed, like much of the highest work, an exquisite banter of human helplessness in the presence of circumstance. Written under such conditions of freedom of description as are now impossible, it furnishes another difficulty to the adapter, who, while he aims at showing results, is not allowed to indicate processes. ‘Tom Jones’ is, in fact, unadaptable. At the price of depriving the story of all charm and the characters of all significance, Mr. Buchanan has obtained precisely the amount of success to be hoped for under the most favourable conditions. In ‘Sophia’ he has produced a piece which is partly comedy, partly melodrama, and which has the one practical recommendation that it goes down with the public. To do this is to do much. Fielding is, however, little concerned with the success. ___

The Illustrated London News (17 April, 1886 - p.6) THE PLAYHOUSES. There was only one way of treating “Tom Jones” for the stage, and that is precisely the way that Mr. Robert Buchanan has treated it. It is idle—nay, it is mere waste of time, to cry aloud and shout for exactly that flavour of Fielding that no author of repute would ever offer, and no respectable audience would ever endure. The true “Tom Jones” is doubtless human; his creator has dissected him for our pleasurable consideration; he has contrasted the good and the bad in the man—his generosity and his meanness—he has shown just when his viciousness overrides his natural frank, lovable, and impulsive nature. We know the man as well now as when Fielding drew him for us with such masterly skill and glowing colours, but it would have been as impossible to place the true Tom Jones before the footlights, to discover the secrets of his life, to describe his adventures, his escapades, his most questionable relations with the Ballastons, the Seagrims, the waiting-maids, the inn servants, the flighty wives, and the fashionable beauties, as it would have been to put into the mouth of Squire Western the coarse oaths and dirty sentences that belong to another century, and were printed by a novelist of the “realistic school.” If Mr. Buchanan had followed Fielding, as some, with strange inconsistency, desire him to do, he would have respected the bookworm and disgusted the playgoer. As it is, he has given to Mr. Thorne at the Vaudeville a capital play, arranged with singular skill, with the comic and serious interest nicely interwoven: he has preserved the essential essence of “Tom Jones” without insisting on its high flavour, and he has provided some clever and careful actors with work far superior to the rubbish that is usually insisted on as requisite for the stage in the present condition of public taste. Why the new play should have been called “Sophia” it would puzzle one to say, except as an imitation of “Olivia,” the last and best version of “The Vicar of Wakefield”; but in the case of Mr. Wills’s play, his title was thoroughly justified. It was wholly and solely the story of the Vicar’s daughter, her temptation, her flight. her ruin, her despair, her return to her father’s home. But Mr. Buchanan’s play is not the story of Sophia, but of Tom Jones. She is a charming, but dramatically a subordinate figure. He is the hero here as he was of the novel. We follow his fortunes and career from end to end. His life in the country, his position at Mr. Allworthy’s, his secret detestation of the sneaking Blifil, his popularity with the girls he kisses and the peasants he protects, his growing love for the incomparable Sophia, his thrashing of Blifil, and his expulsion from the old home, are all told with ready wit and genuine dramatic force. Then comes the change. Tom, in company with the faithful Partridge, follows Sophia to London, is reduced to misery and despair, is inveigled and coaxed, and petted and spoiled, by a designing and not a vicious Lady Bellaston; is rejected by Sophia on evidence of duplicity too strong to resist; and is only restored to her good-will and pure heart when Blifil is unmasked, and the fateful cloud that has overshadowed the hero’s life sails away in the distance, and the true pure sky is blue and sunny again. The acting is throughout even, consistent, and interesting. In one or two instances, however, it rises to remarkable merit. Since Mr. Thomas Thorne played Caleb Deecie in the “Two Roses,” he has had no character that suited him so well, or one to which he has done more justice than Partridge, who is elevated into an important character in the play. These types of character, alternately sentimental and comic, neither unduly pathetic not broadly farcical, suit him admirably. The devotion of the old barber to the young master is charmingly expressed by the actor, and there is a Triplet tenderness in the poverty of the outcast that is very sympathetically told. It would be difficult, indeed, to find a more charming representative of that sweetest of women in all fiction, Sophia Western, than Miss Kate Rorke. This young actress is gaining strength, and showing signs of remarkable future excellence. She acts from her heart; there are wondrously tender-tones in her voice; and she has that most invaluable of all gifts—expression. She “phrases well,” as musicians would say, and she feels what she says, which is what so few modern actresses do. Miss Helen Forsyth made a remarkable success with Molly Seagrim, whose viciousness is of course toned down. The young actress gives us, instead a refined and devulgarised Audrey; a peasant girl with reduced hoydenism, and without the turnip; a loving, unblushing, ill-educated wench, who does not hesitate to say to every handsome lad, “give I a buss,” and to take it without ceremony. Miss Forsyth boldly attacked the character, and carried her audience with her from the first word she uttered. She understood what she was about, and this important fact was speedily known. Mr. Charles Glenny was successful enough with Tom Jones; his passion was perhaps a little theatrical, and his sentiment slightly overdrawn; but his acting was spirited, and he kept the play together. The most difficult character in the play to present properly was Blifil, and Mr. Royce Carleton thoroughly understood it. It was one of those cold, calm, bloodless scamps that Mr. Archer has before now played so remarkably well. His duplicity was absolutely deceptive. Nothing could have been better, in its way, than the acting of Miss Sophie Larkin as Miss Western, or of Miss Lottie Venne as Miss Honour. In smaller characters, Mr. Fuller Mellish, Mr. Akhurst, and Mr. Gilbert Farquhar were always in the picture. The handsome appearance of Miss Rose Leclercq was a good contrast to the simplicity of the rural scenes; and when Mr. Fred. Thorne remembers that the Vaudeville Theatre is not Drury-Lane, there will be very little fault to find with a play that is sure to find favour with future audiences. ___

St. Stephen’s Review (17 April, 1886 - p.23) Sophia, founded on “Tom Jones,” was produced at a matinée at the Vaudeville on Monday last. Opinions differ as to the merits of Mr. Robert Buchanan’s version. To some minds “Tom Jones” is too perfect a story in itself to admit of being “adapted” to the stage and to the present time by even Mr. Buchanan. There is in the piece a want of probability that does not suggest itself in the book. “Tom Jones” is made a very hero of polite comedy. His peccadilloes are lost sight of, and he appears, according to Mr. Buchanan, as a martyr rather than a scapegrace. “Master Blifil” is depicted in the blackest of colours, and is only little less of a prig than “Tom Jones.” With the exception of Mr. Fred. Thorne, who, as “Squire Western,” was so bad as to mar the effect of the scenes in which he appeared, all the characters deserve credit, and the management is to be congratulated on the admirable ensemble and general briskness of the performance. Mr. Gilbert Farquhar made a satisfactory “Mr. Allworthy,” and Mr. Charles Glenney, Mr. Carleton, and Mr. Akhurst were admirable exponents of the respective characters of “Tom Jones,” “Blifil,” and “Square.” Mr. Thomas Thorne essayed the rôle of “Partridge,” and extracted considerable fun from the part, though he was hardly the barber-phlebotomist conceived by Fielding. In my opinion one of the finest studies of female character lately depicted on the stage was the impersonation of “Molly Seagrim” by Miss Helen Forsyth. The part, though slight, required a deal of acting, and Miss Forsyth was eminently successful under trying circumstances. An almost painful realism pervaded her interpretation, and the coarse texture of the dull, heavy, stupid, but altogether lovable girl’s mind, was portrayed with the skilfulness of real genius. Miss Kate Rorke, who acted “Sophia,” was also deserving of all praise. Her manner when with her lover, “Tom Jones” (Mr. Glenny), was almost perfect, and a scene of spontaneous effusion between the pair. during which she throws herself into his arms, provoked an almost hysterical burst of enthusiasm from the audience. For the adapter, Mr. Buchanan, it may certainly be said that he has done a delicate piece of work with great tact; the main plot of the story is worked out with a conciseness that is not too common in recent dramatic productions; and, whatever may be the ultimate fate of Sophia there is no doubt whatever that those present received its production on Monday afternoon with signs of the most cordial approval. ___

The Weekly Dispatch (18 April, 1886 - p.7) THEATRICALS VAUDEVILLE. Mr. Robert Buchanan’s “Sophia” ought to be a success, although it has faults which are almost inevitable to a modern play “founded” on a long novel. Shakespeare constructed his masterpieces on the plots and suggestions offered to him by earlier story tellers; but Mr. Buchanan, although he considers himself competent to “purify” Fielding, in whom he deprecates “a certain taint, which is coarseness rather than immorality” (Mr. Buchanan credits the public with a short memory if he expects it to forget the more than tainted immoralities as well as coarseness that he has given out ere now in profusion), is not a Shakespeare. He has taken the names of his characters, some of their characteristics, the main idea of the plot, and as many of its incidents as he thought he could string together in a four-act play, from Fielding’s “Tom Jones,” and, we gladly admit, has thus built up a piece far superior in incident and dialogue to the average farcical comedy. Let no one suppose, however, that in seeing “Sophia” he is receiving a dramatic interpretation of “Tom Jones.” In a rare freak of modesty Mr. Buchanan admits that “whatever merit the play may possess belongs to him whose supreme genius inspired it; for whatever shortcomings it may show the dramatist is alone to blame.” This is true, and having said this much we may commend as very entertaining and capitally acted patchwork the play which, tentatively performed on Monday afternoon, was placed in the evening programme on Tuesday. Mr. Buchanan has shown some skill in selecting from Fielding’s novel, and sometimes materially altering, enough of its story to keep a modern audience amused during three hours. In the first act we see Tom Jones in his most rollicking mood, contrasting boldly with the hypocritical meanness of his fellow-pupil Blifil, incurring the wrath of his guardian, Mr. Allworthy, by his drunken gaiety, making a worse enemy of Squire Western by his friendship for a poacher, and, most lamentably of all to him, grievously offending Sophia Western by his real and supposed vices; the result of all being that he is driven from his home, and for a time cast off by Sophia, who all the while, and in spite of her principles and aversions, is honestly in love with him, and shrinks desperately from his favoured rival and her treacherous suitor, Blifil. In the next act, which brings Partridge to the front, Sophia, to escape from the marriage with Blifil which is appointed for her, runs away, and Tom Jones follows her at a distance, accompanied by his faithful friend Partridge. In the third, the Lady Bellaston incident being made much of, with perversions, Tom Jones discovers Sophia in London, and when he thinks he has won her forgiveness is again repudiated by her under more sensational conditions than Fielding provided. In the last act everything is set right by a rather clumsy process, which, however, enables all the characters to appear on the stage, and, Blifil being exposed and hopelessly disgraced, results in the concurrence of everybody else in the union of Tom and Sophia. To provide Mr. Thomas Thorne with a suitable part, much is made of Partridge, and, though he is by no means Fielding’s Partridge, Mr. Thorne acts so well, with so much humour and pathos, that his performance alone should suffice to make “Sophia” as it is now played, acceptable. Mr. Charles Glenney’s Tom Jones, also, though not Fielding’s, is vivacious, and Miss Kate Rorke is an altogether charming Sophia Western; while Mr. Royce Carleton gives a very careful and effective personation of the hypocritical Blifil. As Squire Western Mr. Fred Thorne is needlessly boisterous and vulgar, burlesquing rather than representing the manners of eighteenth-century country “gentlefolk”; but he is amusing, and so is Miss Larkin as Miss Western. No better representative of Sophia’s pert maid, Honour, could be found than Miss Lottie Venne, whose briskness makes the part nearly the most diverting in the play. Miss Helen Forsyth also puts in a very attractive appearance now and then as a gushing country wench called Molly Seagrim, but in no way resembling Fielding’s peasant girl of that name; and Miss Rose Leclercq tries hard to personate a heartless eighteenth-century lady of fashion as Lady Bellaston. Other parts are creditable played by Mr. H. Akhurst, Mr. Gilbert Farquhar, and Mr. Fuller Mellish. ___

News of the World (18 April, 1886 - p.7) THE DRAMA. VAUDEVILLE.—Mr. Thomas Thorne has scored a decided success with Sophia—a dramatic version of “Tom Jones,” written by Mr. Robert Buchanan—which, on being received with unquestionable approval on Monday afternoon, was transferred to the evening bills on Tuesday. Henry Fielding’s lively and witty story has been subjected to many changes to make it conformable to the supposed prejudices of modern playgoers, who, by the way, sometimes show a strange facility for swallowing camels when they strain at gnats; indeed the alterations are so numerous that Mr. Buchanan is perfectly justified in referring to his work as being only “founded on” the famous original. The generous light- hearted scapegrace Tom has for his principal companions in this piece the mean-spirited hypocritical Blifil (who is on terms of affectionate intimacy with buxom Molly Seagrim), the designing Lady Bellaston, the loud-voiced Squire Western, the amiable self-denying village barber Partridge, and, it need scarcely be said, the beautiful and innocent Sophia Western, as charming a type of true womanhood as ever found a place in the pages of romance, and whose engaging attributes Mr. Buchanan very effectively preserves upon the stage. The course of a comedy which contains much bright dialogue, and is constructively commendable, may be guessed by those who know “Tom Jones,” when it is stated that the hero is in the first act dismissed from the presence of the kindly Mr. Allworthy for making as is supposed a false accusation against Blifil in relation to Molly Seagrim, that in the second Sophia takes the coach to London rather than wed Blifil, that in the third Jones is ardently pursued by the wealthy woman of fashion Lady Bellaston, and that in the fourth the exposure of Blifil’s treachery restores Jones to the good opinion both of his sweetheart and her friends. Miss Kate Rorke supplies an exceedingly pretty picture to mind as well as to eye as Sophia Western, and the next most pleasant character—the faithful Partridge—is played with much quiet humour and taking geniality by Mr. Thomas Thorne, who has seldom of late had a part more adapted to his style. Excellent impersonations, too, are the Lady Bellaston of Miss Rose Leclercq, the Molly Seagrim of Miss Helen Forsyth, the Miss Western of Miss Sophie Larkin, the Honour (Sophia’s maid) of Miss Lottie Venne, the Tom Jones of Mr. Charles Glenney, the Blifil of Mr. Royce Carleton, and the Squire Western of Mr. Fred Thorne. All these are showy characters, and they could not be better represented. Sophia, it should be added, is not only an interesting but a wholesome and thoroughly English sample of nineteenth-century comedy. ___

Reynolds’s Newspaper (18 April, 1886) PUBLIC AMUSEMENTS. VAUDEVILLE THEATRE. What must chiefly have struck the intelligent playgoer who on Monday afternoon witnessed the performance of Mr. Robert Buchanan’s interesting dramatic version of “Tom Jones,” was, firstly, that Mr. Thorne had in the adaptation of this old standard work secured a piece likely to suit the general public taste; and, secondly, that Fielding’s novel offered another exemplification of the truth of the proverb which insists upon there being nothing new under the sun. As like as two peas, or as Mr. Pinero’s “Squire” to “Far from the Madding Crowd,” are many of the characters and sayings in Sheridan’s comedy of the “School for Scandal” and those which Mr. Buchanan has in his “Sophia” taken from the novel. Tom Jones is, in his light, buoyant humour, reckless generosity, and natural kindliness of heart, the prototype of Charles Surface. Blifil, with his assumed studiousness, oily hypocrisy, and oft-quoted philosophy, is the double of Joseph Surface and his sentiment; Sophia is the model of Maria; Lady Sneerwell might have been suggested by Squire Western’s sister; and but for her age and the fact of her having buried two husbands, Lady Bellaston and Lady Teazle occupy a very similar and equally do-nothing position in society. This similitude, however, in no wise detracts from the attraction of the play. We simply meet old friends in a new dress and with fresh surroundings. At the commencement of the piece, Tom Jones, who has been partaking of the cup which inebriates as well as cheers, shows a decided liking for Squire Western’s charming daughter, and a pretty talent for osculatory exercise, which, in more modern times, would have made “the foundling” a prime favourite at Sunday schools. But what Tom Jones does is done openly; he wears his heart upon his sleeve, and no wonder, therefore, that daws of the Blifil genus peck at it. In secret, this Blifil has won the affections of Molly Seagrim, a character which Mr. Buchanan has artistically changed from the unpresentable personage of the novel to a decidedly attractive Audrey. By his championship of Molly’s father, the hero excites the anger of Squire Western, and makes that Conservative member of the unpaid magistracy more than ever averse to a union between Tom and Sophia; whilst, on the other hand, the time-serving Blifil, by his moralizing upon the enormity of a man killing a hare for his starving family, makes himself a favoured suitor in the Squire’s eyes. By the devices of Blifil, who, much to the satisfaction of the audience, comes in for a thorough thrashing at the hands of his rival, mischief is made, not only between the hero and his kind, if pedantic, guardian, Mr. Allworthy, but also between Tom and his fair mistress, the lady being led to believe him the sweetheart of Molly. To avoid the odious match with Blifil, Sophia, with her vivacious maid, Honour, seeks shelter in London with her fashionable cousin, Lady Bellaston, and to London Tom, accompanied by the faithful and Latin-quoting barber, Partridge, follows her. Lady Bellaston, struck by the good looks of Tom, conceals from him the presence of her cousin Sophia, and behaves in a manner worthy of a Bowdlerized edition of Potiphar’s wife. In spite of his poverty and the attractions of Lady Bellaston’s wealth, Tom is as deaf as a second Joseph—the Joseph of Scripture, not of Sheridan—to the voice of the charmer, and remains true to the memory of his beloved Sophia. By a series of incidents, cleverly and naturally brought about, Honour, Lady Bellaston, and Sophia visit Tom’s attic, and—here an agreeable flavour of modern farcical comedy coming in—are concealed in cupboards and Tom’s bedroom. From the latter Lady Bellaston is “unearthed” by Squire Western, who has come in search of his daughter, whilst her presence is made to appear in Sophia’s eyes as a proof of her lover’s faithlessness. In the last act, my lady, irritated by Tom’s constancy for Sophia and indifference to herself, joins with his enemies, but is defeated by Honour, who from her hiding-place has been a witness of the whole scene. Molly Seagrim exposes the perfidy of Blifil, and Sophia and Tom enter that lover’s haven of rest, each other’s arms, without which no well-ordered comedy is complete. The new piece has the advantage of being exceptionally well played. Its hero is as well and heartily carried out by Mr. Charles Glenney as is that of “Harbour Lights” by Mr. Terriss. Both are admirable specimens of what our modern young actors can do. Mr. Glenney’s rollicking good-nature in the earlier scenes, his sympathetic acting in the more tender ones with Sophia, and his energetic castigation of his rival, won him golden opinions from his audience. Maybe one would have liked to see Tom Jones a more cheerful and blithe person than he is represented in the garret scene; but such an interpretation would have been at variance with the author’s text. Miss Kate Rorke formed a companion picture, matching well with Mr. Glenney’s of Tom, as the charming Sophia, whom she made one of the most dainty and lovable of old comedy heroines. The difficult part of Blifil was, in the hands of Mr. Royce Carleton, capitally represented, the oily hypocrisy, beneath which the viciousness of the character now and again peeps out, being a cleverly-conceived and executed study. In the village barber and phlebotomist, Partridge, with his humorous sayings, Latin quotations, and reminiscences of the late Mrs. partridge, Mr. Thomas Thorne was fitted with a part which exactly suited his quaint drollery, whilst his rendering of the more sympathetic side of the man’s character had more than one agreeable touch of pathos. Miss Sophie Larkin’s gushing middle-aged spinster has formed subject for mirth to Vaudeville patrons again and again; but so long as she can afford such amusement as she did as Miss Western on Monday no one would wish to see her in any new form of character. A very fresh and bright bit of acting was the Molly Seagrim of Miss Helen Forsyth; Miss Lottie Venne was a delightfully coquettish Honour; and Miss Rose Leclercq was an overwhelmingly grand Lady Bellaston, seeming in her gorgeous attire not only to fill the stage, but the whole house, with her presence. Mr. Fred Thorne’s reading of the noisy, choleric, hunting Squire is doubtless correct in theory, but it proved objectionable in practice. He seemed to want a few hundred acres of breezy downland to exercise his lungs upon, and until these are forthcoming, a little moderation of their power will make his acting of Squire Western more in accordance with his surroundings. Mr. Fuller Mellish as the Poacher, Mr. Gilbert Farquhar as Squire Allworthy, Mr. H. Akhurst as Square, and other parts by their respective representatives were adequately filled. Amongst the large audience which witnessed Mr. Buchanan’s play were Messrs. Irving and Gilbert, Mrs. Langtry, Miss Harriett Jay, and a host of theatrical celebrities. The excessively favourable reception awarded it was sufficient warranty for the management to place “Sophia” upon the evening bills on Tuesday night. ___

Lloyd’s Weekly London Newspaper (18 April, 1886 - p.5) PUBLIC AMUSEMENTS. VAUDEVILLE THEATRE. An interesting and attractive piece has been evolved by Mr. Robert Buchanan from Fielding’s “Tom Jones.” The play of Sophia fortunately differs from the book in being pure and healthy. Tom Jones, as we make his acquaintance on the stage, is a naturally merry young gentleman, but the villainy of a certain Blifil—a suave, moralising villain from whom Sheridan borrowed his Joseph Surface—casts the shadow of shame on Tom. He is thereupon disowned by his guardian, and becomes a gloomy, distressful gentleman. Sophie Western, the object of his affections, has to fly to London to avoid being forced into a marriage with Blifil. Tom Jones follows her to the metropolis, and although he falls upon evil days, does not hesitate to go in his shabby clothes to the house of Milady Bellaston to inquire after Sophia. Lady Bellaston, a gorgeous female in paint and patches, conceives a liking for him, and a fervent wish, she being a widow, to herself assume the ancient patronymic of Jones. She does not hesitate to go in person to the humble but exalted (fifth-storey garret) residence of Tom, to propose such a match. Here we have a truly remarkable scene. Lady Bellaston hides herself in an adjoining room as Sophia comes unexpectedly to see her sweetheart. Sophia herself presently has to seek refuge in another room as her father forces himself into the house; whilst to still further complicate matters there is a third lady, harmlessly enough concealed in a cupboard. The discovery of all three leads to Sophia declaring her intention of accepting Blifil, conceiving the worst of Tom from the presence of two other ladies. A happy reconciliation, however, takes place in the next act; and though such a finish is self-evident from the first, it is so skilfully put off that it finally gives unaffected pleasure to the interested spectator. Curiously enough, whilst the piece is chiefly Tom Jones in narrative, the interest follows Sophia, and irresistible result of the personal charm of Miss Kate Rorke, who plays it in the quaint hats and dresses of Fielding’s period. She is a most attractive picture; and her prettiness and daintiness steal upon one’s feelings imperceptibly. There is the true ring of earnestness in her Sophia. At the first presentation of the piece she took her audience by storm, and whilst Sophia as a play secured a success, Sophia as an actress secured even greater esteem. Mr. Charles Glenny plays Tom with so much spontaneity and brightness in the first act that his sorrows, most skilfully portrayed, awaken deep sympathy. It is an admirable and artistic performance throughout. Mr. Thomas Thorne has a capital part in a genial barber, who stands in the relation of a Mark Tapley to the hero. Other characters are well played by Mr. Royce Carleton, Miss Lottie Venne, Miss Rose Leclercq, Miss Larkin, and Mr. Fred Thorne. At the trial performance on Monday afternoon, Sophia was most favourably received, and it was immediately placed in the evening programme. ___

The Referee (18 April, 1886 - p.2) DRAMATIC & MUSICAL GOSSIP. SOPHIA is a very pretty name, but nowadays it would be voted plain and unfashionable. I first became acquainted with it, liked it, loved it in the days of my boyhood. Sophia Brown was the girl who threw the handkerchief at me in a Sunday-school kissing game, and at once fired my young heart with a burning and, as I thought, imperishable devotion. I never told my love—l hadn’t pluck enough—but I spent hours in all sorts of weather gazing at her beautiful face and form as she sat at work in the milliner’s shop where she earned her bread-and-butter. Ah me! many a sleepless night was caused by thoughts of Sophia, and so badly had I caught it that the wonder was I did not pine away into an early sepulchre. When I had learnt to forget Sophia—curiously enough I have discovered that she is now the wife of the man who comes for my gas—l got to like the name in another way. Having, as I was told, a very pretty voice, and being passionately fond of music, and especially vocal music, I became a member of a glee and catch club, and well do I remember how heartily I enjoyed the fun when we used to alarm the neighbours by giving forth, in what without a doubt was splendid harmony, “O, Sophia! O, Sophia!” which, being repeated and repeated after the catch fashion, suggested that there was a house a-fire, and occasionally sent somebody scampering for the turncock and the engines. My next association with the name of Sophia was——What’s that you say? Where am I driving to? O, well, if you don’t like an occasional digression I had better come to the point at once, and the point in this instance happens to be “Sophia,” which, as you know, is the title given by Mr. Robert Buchanan to his adaptation of Henry Fielding’s celebrated novel “Tom Jones,” brought out at a Vaudeville matinée on Monday before a crowded audience numbering plenty of members of the profession, including Henry Irving and Walter Joyce. A prologue was announced to be spoken after the old-fashioned way, but those in authority thought better of this part of the business, had the prologue printed, and planted a copy upon every seat for the edification of the occupant. From this prologue I was able to learn that Mr. Buchanan is “a trembling author.” From his “note” which prefaced the cast I gather that now he is a tolerably modest one, for, although he does compare himself with Sheridan, he attributes any merit his play may possess to him whose genius inspired it, and adds that the dramatist is alone to blame for any shortcomings it may show. In undertaking to dramatise “Tom Jones,” R. B. undertook a task of enormous difficulty, and the fact that he has come through it so well speaks volumes for his skill. Of course Fielding has had to suffer; that was inevitable, for Fielding pur et simple would never do for Mr. Gilbert’s young lady of fifteen, nor indeed for lady playgoers of a maturer growth. Nobody, therefore, must grumble when reading that Mr. Buchanan, while trying to preserve Fielding’s healthy moral, has taken leave to purify the character of the hero somewhat, to alter many of the incidents, and to invent others. Here it is all in a nutshell. Love is to-day our theme? The “two rivals ruffling” are, you will understand, Tom Jones, joyous and despondent by turns, and Blifil, the everlasting sneak and hypocrite. Tom Jones is a good young man now, although he does get gloriously drunk before the curtain goes up. He makes bibulous love to Sophia; he sobers himself by putting his head under the pump; he pleads for the release of poacher Seagrim; he kisses Seagrim’s daughter Molly, betrayed of Blifil, and to this plausible scoundrel he administers a splendid flogging. “Dear, dear me! whatever is the matter?” “Well, he has insulted me, and I’ve thrashed him, that’s all,” answers Tom, and Tom is forthwith turned adrift by “Guardie” Allworthy, and takes up his abode with Partridge, the village barber, a nervous shaver, a remarkable tooth-drawer, an expert blood-letter, and a wonderful scholar. Sophia, pressed to marry Blifil, whom she hates, takes coach to London, and seeks refuge with her relative, Lady Bellaston, who, when Tom comes along to look for his sweetheart, makes eyes at him and hints that be may have her—Lady B.—for the asking. “Get away,” in effect, says Tom, who isn’t half so amorous as he was in the beginning, when he had the wine aboard; and her ladyship has to get. In Tom’s sky parlour, to which we are presently introduced, Mr. Buchanan has contrived a very ingenious and amusing complication, which at once suggests a Criterion comedy of doors. Through no fault of his own, Tom finds himself all at once encumbered with three women. They are Mrs. Honour, Lady Bellaston, and Sophia Western. Not one of them is aware of the presence of the others. Lady B. is bold and brazen enough to say “I must have a kiss,” and to plant one on Tom’s cheek before she goes into hiding; and Sophia, who arrives last, receives an emphatic answer in the affirmative when she asks Tom if he will be constant and kind, and keep away from the bottle. Then Squire Western and Blifil come upon the scene, and Lady B. is dragged out and exposed; poor Sophia comes from her cupboard in a pretty pet, and it seems to be all u. p. with Tom’s chances of ever calling her wife. But, as you will guess, the needful exposure for the wicked comes with the last act, as also do the needful explanations between the good; Lady Bellaston—the brazen hussy—is held up to scorn and ridicule; Blifil is dismissed with contempt; omnia vincit amor; and just when the curtain is coming down, if you have a lively fancy, you may hear the first sound of the bells which proclaim the wedding morn of Tom Jones and Sophia Western. The Sophia was Miss Kate Rorke—therefore was Sophia beautiful, intelligent, interesting and lovable. Her hat in the first act was a work of art, and her tears in the second were so real that I sighed for the opportunity to wipe them away. Sophia’s loved one, Tom Jones, was represented by Mr. Charles Glenney, who, both drunk and sober, pleased me greatly, particularly when he was soundly beating the abominable Blifil, impersonated with rare skill by Mr. Royce Carleton, who won the hearty praise of the whole house, and scored a splendid success. Mr. Fred Thorne, albeit much too noisy, amusingly brought out the undesirable proclivities of the hard-drinking Squire; and Mr. Fuller Mellish as Seagrim, arrested for poaching and threatened with a gaol, put the true ring into his appeal for mercy. Mr. Thomas Thorne, as Partridge, was all lather and Latin in the second act, and further on his shop phrase “Next, please,” caused much laughter among those who, being accustomed to the ways of easy shavers, were able to see the point. The character suits Thorne, and Thorne suits the character, so that everybody ought to be satisfied. Miss Sophie Larkin as Miss Western was funny, as she always is when she gets a chance. Unfortunately her one good scene seriously hampers the action in Act II. Miss Helen Forsyth delighted everybody with her Molly Seagrim; Miss Lottie Venne was bewitchingly piquant as Mrs. Honour; and all the fashionable frivolity of my Lady Bellaston was well brought out by Miss Rose Leclercq. “Sophia,” I should say, is down for a long run. There will be a special morning performance of “Sophia” at the Vaudeville next Saturday, and another on Easter Monday. ___

The People (18 April, 1886 - p.14) THE THEATRES. VAUDEVILLE. In his adaptation of Fielding’s famous novel of “Tom Jones,” first produced at the Vaudeville at a morning performance on Monday, and consequently, upon the approval of the public, transferred to the evening programme on the following evening, Mr. Robert Buchanan has taken as many liberties with the hero as that free-and-easy young gentleman took with the various ladies with whom he was brought into association. These escapades the adaptor has suppressed altogether, or transferred to that radically wicked personage, Mr. Blifil, the moralising impostor from whom Sheridan borrowed the salient characteristics of Joseph Surface in “The School for Scandal.” In consideration, however, of the fact that Mr. Buchanan has evolved a clever and interesting drama more or less out of the story, playgoers will not take him to task too severely for not following its incidents with rigid exactitude. But in rendering Tom Jones morally consistent with the proprieties, as formulated by that eminently respectable social lawgiver, Mrs. Grundy, his rehabilitator has invested the bluff Squire Western with inconsistency by making him refuse the hand of his daughter Sophia to her lover without any apparent cause arising out of the young gentleman’s conduct to the lady herself or any other representative of her sex. Evidently with a politic view to enlisting the sympathies of spectators in his behalf, Tom Jones, as set forth in the play, is sorely misrepresented, not only by ill-designing individuals, but by hard fate into the bargain. Repudiated as a suitor for Sophia by her boorish bucolic father, Tom comes to London to seek his fortune, and, as ill-luck will have it, raises by his good looks a passion he cannot reciprocate in the breast of the Lady Bellaston. This amorous middle-aged dowager, visiting Tom’s poverty-stricken lodging in prosecution of her unwelcome suit, is found concealed there by Sophia, whose jealousy is naturally aroused, causing the passionate girl, as her father had previously done, to cast off her innocent buy unlucky suitor. All misconceptions are, however, cleared up at last, and true love meets with its just reward. The scenes by means of which this sympathetic result is finally brought about are so contrived as to give the audience a craftily qualified mixture of earnest action and humorous incident. The misunderstanding between Tom Jones and Sophia, cunningly intensified by the lying machinations of the insidious Blifil, leads to exhibitions of feeling on the part of the lovers which are prevented from becoming monotonous by the constant irruption of Partridge, the comic village barber, whose humours, none the less that they differ from those of Fielding, are, as presented by Mr. Thomas Thorne, a constant source of hilarious merriment to the audience. It is long since this excellent impersonator of quaint eccentricities has been fitted with a character so thoroughly suited to his powers as a comedian. His Partridge is, indeed, the best played part in the piece. Next to it in histrionic quality comes the Lady Bellaston, a repulsive personage by reason of her preposterous amativeness, played with courageous sincerity by Miss Rose Leclercq. The Sophia Western of Miss Kate Rorke is marked by genuine earnestness, though somewhat lacking in social distinction. The charm of simplicity is never absent, but it is indicative of a farmer’s pretty daughter rather than of a gentlewoman. As Tom Jones, Mr. Glenney, while always vigorous, is lacking in light and shade, proving himself too flamboyant in gesture with a marked tendency to gush both in verbal and facial expression. Admirably winsome in its quaint, old-fashioned primness, was the waiting-maid, Honour, as represent by Miss Lottie Venne, one of the few actresses with an innate sense of humour. Miss Larkin is another; the ancient spinster, Miss Western, however, gives this lady few opportunities of expressing her quality. The Squire Western of Mr. Frederick Thorne was altogether too boorish to be accepted as typical of the English country gentleman, however unsophisticated, of a century and a half ago. Mr. Royce Carleton, as Blifil, gave a faithfully consistent portrayal of smiling sentimental hypocrisy. The promising young actress, Miss Forsyth, need scarcely have disfigured her natural charms of presence by giving to Molly Seagrim, the gipsy girl, an aspect too coarse to be picturesque. Mr. Allworthy appears a a courtly gentleman of the old school of manners, as presented by Mr. G. Farquhar. The adaptation was received throughout with such unqualified manifestations of satisfaction as augur for it a long and prosperous run. ___

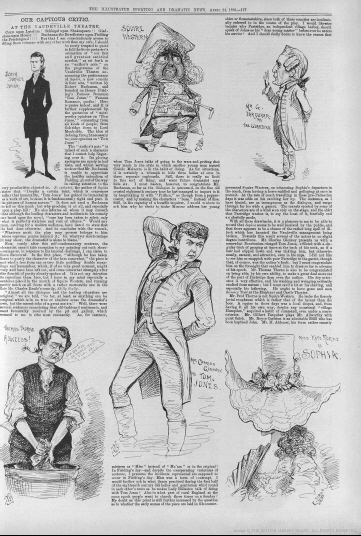

The Illustrated Sporting and Dramatic News (24 April, 1886 - p.21-22) OUR CAPTIOUS CRITIC. |

|

|

||

|

The Theatre (1 May, 1886 - pp.275-276) “SOPHIA.” A Four-Act Comedy, adapted by ROBERT BUCHANAN from Fielding’s Novel, “Tom Jones.” |

|

|

|

A crowded, not to say crammed, house greeted Mr. Buchanan’s version of “Tom Jones” at the Vaudeville, brought forward at a morning performance. This seems to have excited a certain amount of ingenious speculation, though the truth is it has been constantly done at this house—an ingeniously tentative mode of experimenting on an audience. The acting on this occasion was full of spirit and liveliness, and the distinct freshness of the characters gave unbounded satisfaction. It was curious to note the suggestions here for “The School for Scandal,” it being clear that Sheridan drew the characters of the two Surfaces from Blifil and Tom. It is not, however, so well known that the famous and ever-effective “screen scene” was taken from the same source, the screen being the old curtain, which fell so awkwardly and discovered the Tutor in Molly Seagrim’s room. Even the culprit’s protest on his detection is in the form of Joseph’s “Notwithstanding, Sir Peter, all that has passed,” &c. The amazingly light touch of Sheridan, his fashion of abstracting the very essence of a character, is happily shown by contrast with this work of Mr. Buchanan, who, at least, cannot be blamed for lacking the genius of the gifted Brinsley. Indeed, the modern system of bringing out details of a character is invariably to make every sentence illustrate the character as the hypocrite may only deliver hypocritical sentiments, &c., whereas, as we learn from Shakespeare, a colourless or indifferent line is often as appropriate. PERCY FITZGERALD. (pp.279-280) Another surprising success has been made in the course of the month by Miss Helen Forsyth, the bright, clever, human little Molly Seagrim attached to Mr. Robert Buchanan’s “Sophia” at the Vaudeville. Hitherto, Miss Helen Forsyth has only been known as the pretty girl in several Haymarket plays. With a sweet voice and a charmingly refined manner, she has justly been considered one of the best of the modern drawing-room young ladies. She was welcomed, and justly so, in “Dark Days,” and at the first performance of “Jim the Penman” she showed how a bright, happy English girl can be naturally and unaffectedly played. But few were prepared for the transformation as Molly Seagrim. Away went the pretty frocks, the fair skin was stained to the tint of a gipsy, and Miss Forsyth appeared to the very life as a country hoyden, loving, ignorant, passionate, unsophisticated, the very picture of a village wench who might have been a poacher’s daughter. But Miss Forsyth did not succeed alone as a picture of highly-coloured rusticity. She entered into the heart and spirit of the character. She understood Molly Seagrim, the tangled weed of the country lanes, soon to be crushed under a strong man’s heel. It was a clever performance because we felt there was art in it and not artifice. Directly Miss Forsyth came on the stage the whole attention of the house was directed towards her. She had enlisted the sympathetic attention of her audience, and she held it whenever she was on the stage. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|