ROBERT WILLIAMS BUCHANAN (1841 - 1901)

|

ROBERT WILLIAMS BUCHANAN (1841 - 1901) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

HARRIETT JAY BOOK REVIEWS

1. The Queen of Connaught (1875) to Madge Dunraven (1879)

1. Novels The following is taken from Ireland in Fiction: A Guide to Irish Novels, Tales, Romances, and Folk-Lore by Stephen J. Brown, S.J. (Dublin and London: Maunsel and Company, Ltd., 1916 - p.121): JAY, Harriett. A sister-in-law and adopted daughter of the late Robert Buchanan, Scottish poet and novelist. She lived for some years in Mayo, and the result of her observations was two good novels. She wrote also Madge Dunraven, and some other novels, not of Irish interest. — THE QUEEN OF CONNAUGHT. (Chatto & Windus). Picture boards. 2s. n.d. (1875). — THE DARK COLLEEN. Three Vols. (Bentley). 1876. — THE PRIEST’S BLESSING; or, Poor Patrick’s progress from this world to a better. Pp. 308. (F. V. White). Two eds. 1881. — MY CONNAUGHT COUSINS. Three Vols. (F. V. White). 1883. _____

|

|

|

|

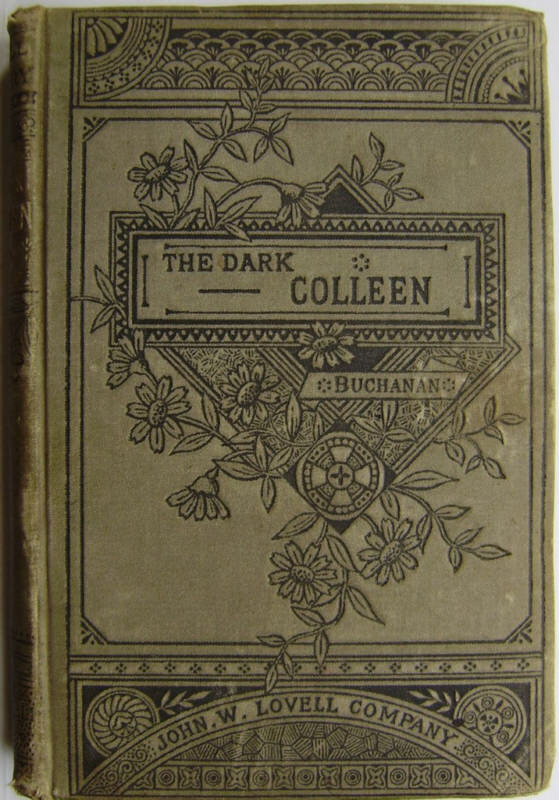

[Cover of an American edition of The Dark Colleen - note the ‘Buchanan’.]

The Nonconformist (24 January, 1877) “THE DARK COLLEEN.”* The author of the “Queen of Connaught” has here presented us with another story of Irish life, which certainly surpasses the first novel in variety of incident, racy dialogue, and broad humour. And this is no slight praise. Though it cannot be said that the representations of Irish character are all couleur de rose, we cannot but believe that they are as near as may be transcripts from reality—close studies. They convey to us the impression of real persons, however far they may fall short of the ideal of the gay, smiling, humorous Irish types, to which certain writers of the past have accustomed us. But it needs to be frankly said that, whilst the people in general are faithfully put before us, with all their prejudices and dark superstitions, we have here at least four characters which stand out pure and beautiful—the brighter from the excess of cloud and gloom which rests upon their surroundings. A glance at the main outlines of the story will, perhaps, bring this out. As the waters closed over her, the moonlight was quenched, and the hills, the cliffs, and the sky, seemed to dissolve away. What followed seemed like a dream. She had closed her eyes when she sank into the sea; when the opened them again she had reached the bottom. A strange grey light played upon the water above her head; she saw huge crimson flowers rising around her, magnified to double their ordinary size, swayed softly by the water, and gleaming coldly in the light. The splinters of rock and smooth-topped stones, lying embedded in the sand, became magnified before her, and the yellow-ribbed sand itself appeared in strange commotion. Morna could see nothing distinctly, all seemed moving and swaying to-and-fro in palpitating tremor. The patches of long grass and sea-moss which covered the spot known as the Isle na Rhuinish were bent this way and that way by the softly surging sea, and the clusters of sea anemones set amidst masses of tangled weed lifted up their heads beneath the water and moved too. All this was seen, as it were, only for a moment, in one quick flash of sense. She reached the bottom, mechanically stretched forth her hand, grasped one of the crimson sea-flowers, and uprooted it from the sand . . . . then she let the water uplift her again, and rising to the surface, swam slowly to the shore. Morna Dunroon is a new addition to our gallery of female types in fiction; and we think we may safely say that few will regret becoming more fully acquainted with her; for, though the weird and superstitious ideas of the people give the novel an air of romance, the heroine’s character comes out clear, real, and quietly commanding. * The Dark Colleen. A Love Story. By the author of the “Queen of Connaught.” In three vols. (R. Bentley and Son.) ___

The Daily News (30 January, 1877) There is an old Joe Miller about a Frenchman who wanted plum-pudding at Christmas-time. He weighed out suet, currants, flour, and all the ingredients with mathematical precision from a recipe which did not mention the pudding-cloth. So, having stewed our national dish with great pains for many hours he served it up in a soup tureen. The case of this Frenchman may be applied to the writer of “The Dark Colleen” (3 vols., Bentley). Her book combines all the ingredients of an excellent novel. Her heroine is handsome; her hero is handsome, the plan of the story is original, it is full of adventures, and the scenery is new and picturesque. But for want of some inexplicable quality the whole is a failure. The handsome heroine is a grotesque savage; and the hero is a monster without a heart. Where is the reader who would care to read the adventures of such a couple? As to the picturesque scenery, it is not more real than the scenery on the stage. It may be said that to make such a criticism good its writer should point out the one thing needful in this story, the missing touch of nature that makes the whole book kin. But while physiologists are unable to demonstrate the beginnings of life, a critic may be pardoned who follows their example. Perhaps such sentences as these contribute towards the grotesque impression left by the heroine on the reader’s mind. Morna “unconcernedly stretched forth her hand, took one of the steaming potatoes, squeezed it in her palm, and began to eat. . . . She set her white teeth into one after another of the hard brown potato skins.” A heroine showing her teeth over potato skins is in a grotesque position. Or take this, where after surviving a danger she embraces a donkey, which is not less of a donkey because it is written down an ass with a capital A. “For a moment all stood amazed, gazing silently upon the man’s senseless form;” the man had pursued Morna; “then Morna ran to the Ass, and fell with a low hysterical cry upon her neck.” As to the hero, readers who, to speak hyperbolically, try their impression of him by the fire of recollection, will find he dwindles away, like the naughty girl who played with matches in the nursery story, to a little heap of cigars and blue eyes; his only adjuncts. ___

The Athenæum (10 February, 1877) The author of ‘The Queen of Connaught’ has again given to the world an interesting and romantic tale. This time her Irish heroine is of a different type from the Kathleen we remember, but resembles her in her thorough nationality, and the wreck she makes of her life through an ill-fated marriage with one of a different race. The misery of Morna Dunroon, however, is in this more poignant than Kathleen’s, that the man she marries is one she can never learn to respect, though she lavishes all the affection of a simple and loyal nature upon the hero of her girlish imagination. Bisson is a gay young Frenchman, captain of a merchant ship, a dandy and a debauchee, blasé with the experiences of fast life in seaport towns, without the simplicity of a peasant or the culture of a gentleman. Morna, on the other hand, is a child of nature, lowly but not vulgar in her surroundings from her birth, the daughter of a fisherman on one of the Western isles, bred among the sights and sounds of a stormy corner of the wild Atlantic, and accustomed to no companionship more exciting than that of her kinsmen, and no novelty greater than the occasional visits of a far-travelled beggar from the mainland, or the atmosphere of devotion and conviviality imported by the parish priest on his expeditions to his distant cure. It is rather unfortunate that the story should suggest a comparison with Mr. Black’s delightful Princess, for Morna cannot be admitted to equal her northern prototype, though Bisson is distinctly a better imagined and completer foil to her than the merely common-place Lavender. For Bisson, worthless as he is, has positive and peculiar characteristics, and though totally unable to value his wild Irish bride, might have made his artificial little Frenchwoman a happy wife enough. But it was a luckless day for Eagle Island when the too amiable Emile was cast upon its shores, and not again committed to the deep by its gloomy and superstitious inhabitants. Very original is the charm of the early days of poor Morna’s romance, the rugged grandeur of her home, the ;picturesque habits and primitive ceremonies, the tenderness and ferocity of her melancholy Celtic kindred, relieved now and then by the humour of Irish visitors of a better-known type, such as Father Moy, the benevolent despot over the souls, and, within large limits, the bodies of his flock; Barron O’Cloaskey, the wandering piper, with his gentlemanly though impoverished father, a “cosherer” quite of the olden type, and his faithful ass, nearly as patrician in his instincts, and scarcely less dear to the affections of his owner. But these alleviations serve merely to enhance the tragedy of the tale, the exile and despair of Morna, and the long-suffering fidelity of her real lover, Truagh, who for her sake can forego even the vengeance on her betrayer which fortune offers him at last. ___

The Morning Post (23 February, 1877 - p.7) THE DARK COLLEEN.* In connection with a recent literary controversy to which it is unnecessary to refer more particularly, it is natural that interest of a special nature should attach to any new work by the author of “The Queen of Connaught,” and it must be acknowledged that the present novel contains excellencies which go far to justify the high opinion of its writer’s talents which has been already expressed. The book is not faultless, but its errors are not of such a nature as to militate against the theory that we may possibly find in its author a worthy successor, though in a somewhat different line, to those great bygone delineators of Irish life and character whose names have become household words. The chief objection to the tale of poor Morna Dunroon’s ill-starred love affair is its extremely unsatisfactory ending. After so much sympathy with the heroine has been excited it is disappointing to the reader who has followed her fortunes at home and abroad to be compelled to leave her, in company with Truagh and his mother, watching over the body of her worthless husband, without any indication of possible brighter days in store for her. She is the one character in the novel, excepting perhaps her deformed admirer, in whom one can take any vital interest, and at least some hint might have been given that she was not doomed to wear out her young life in unavailing regret for a scoundrel like Emile Bisson. As for Truagh, it would certainly have been irrational to expect that his faithful service should be rewarded with the hand of his cynosure; but it is evident that Morna’s happiness would have made his. Yet these two, the only thoroughly amiable personages of the story, are left in apparently hopeless misery, which may be in accordance with the frequent course of events in the real world, but sins against that canon of poetic justice which is demanded in the realm of fiction. The other characters are not calculated to excite more than a feeble interest; Dunroon and his fellows are rather conventional renderings of ignorant fishermen, with a dash of the wrecker element about them; Bisson, who must, faut de mieux, be accepted as the hero, is such a cold-hearted, selfish villain as not even his reported personal and social charms can rescue from detestation; whilst the only feeling that can arise touching Euphrasie is that, if she was deceived in her marriage, her thorough worldly heartlessness debar her from all claims upon general sympathy. It remains only to speak of Father Moy, the spiritual director of Eagle Island, and the task is rather a difficult one. It would be impossible to believe that the author intends to present the priest as a fair type of any class of Roman ecclesiastic; and yet if that was not the intention the portrait becomes a monstrous anomaly. He is more than hinted to be little better than a sot; though it is true that his abnormal potations do not intoxicate him; yet with this idiosyncracy, which must have lowered him in the eyes of his flock, he is represented as having been a tender-hearted, pious priest, sharing the joys and sorrows of his people, even to their poverty, as shown in the clever scene where Morna finds him thatching his four-post bed because the roof of his cottage let the water through. One wonders, by the bye, why the good father did not thatch the roof itself, since he was so clever. Undoubtedly that predilection for whiskey, at his parishioners’ expense, is a blemish in an otherwise agreeable sketch and one cannot avoid a secret suspicion that the trait is introduced in order to give a thrust at the man because he was a Roman Catholic priest. Throughout the novel there is too obvious a tendency to sneer at matters which, whatever may be a writer’s personal convictions, it should be remembered are sacred things to a vast number of our fellow- creatures. It can serve no good purpose, and must cause pain to many, to write such a description as that of the midnight mass at Bernise; and it is not clever to talk of a “sceneshifter” in connection with a solemn religious ceremony, nor to characterise the ecclesiastical vestments as “theatrical finery.” Scoffing will not bolster up a bad cause, and is inconsistent with a good one. *The Dark Colleen: A love story. By the author of “The Queen of Connaught,” 3 vols. London: R. Bentley and Son. ___

The Pall Mall Gazette (7 March, 1877 - p.12) “THE DARK COLLEEN.”* “THE Dark Colleen” may most briefly be described as an Irish Princess of Thule. Morna Dunroon, like Sheila in Mr. Black’s story, is the daughter of a peasant prince, the ruler of Eagle Island, far to the west of Ireland. Like Sheila, she is innocent, courageous, and beautiful; and, like Sheila, she marries a man quite unworthy of her, who wearies of his wife when he returns to civilization. But Emile Bisson, the shipwrecked French sailor who carries off Morna, is a much worse character than Lavender. The civilization in which he rejoices is that of small cafés and billiard-rooms in a little French sea town. Indeed, we refuse to believe in this dandified mariner, who wears gloves, uses perfumes, and generally minces in a very affected manner. Though there is this amount of resemblance in the motives of the Scotch and Irish stories, it is fair to say that the originality of the latter is complete. The charm of “The Dark Colleen” lies in the picture of a free and unfamiliar life, not like that of Ireland nor much like that of the Hebrides. The subordinate persons, priests and peasants, are not like Lever’s, Irishy. The natives of Eagle Island—part Spanish, part Celtic by blood—had institutions and superstitions which are no longer powerful even in Barra and Borva. They elected their own king, on the principles laid down in the “Rejected Addresses.” As long as no one “made the quartern loaf and Luddites rise,” or, rather, as long as there was no trouble with Fenians and potato disease, the elected monarch retained his position. But if anything went wrong, if herrings were scarce and gaugers inquisitive, the potentate’s luck was supposed to have turned and a new prince was elected. Now, it was the fate of Morna Dunroon to harm the island by saving a drowning man from being tossed back into the water by her father’s superstitious subjects. Hence it became necessary to propitiate the offended Lady of the Waters, and Morna attempted to do this by diving, in the full moonlight, down to the gardens of the deep. This is the second occasion on which we are permitted to see the heroine in quite unadorned beauty as of a “statue of marble on a lonely Athenian coast.” “The outlines of her form were perfect, as the moonlight fell upon her soft, white limbs and upon the tremulous shadow of her hair, which was scattered far over her neck and shoulders.” * “The Dark Colleen.” By the Author of “The Queen of Connaught.” (London: Richard Bentley and Son. 1877.) ___

The Graphic (17 March, 1877) “The Dark Colleen: a Love Story,” by the author of “The Queen of Connaught” (3 vols.: Bentley).— This is unquestionably a book of mark as it stands, and would have been a finer story than it is were it not that the author’s hand cannot always be trusted to work out her conceptions surely and unerringly, whilst we are all the more sensitive to any deficiencies in power inasmuch as the latter half of the tale is of so painful a character that we need wellnigh flawless work to reconcile us to it. In her “word-pictures” and still-life scenes the author is all that could be desired, but she seems less in her element when action is called for, sometimes going a long way towards spoiling the effect she is aiming at by a tendency to diffuseness. Eagle Island, the home of “the Dark Colleen,” and its strange life, is a veritable “find” for any novelist, and the author makes very nearly as much out of her subject as Mr. Black has made out of the Hebrides. Eagle Island lies far out in the Atlantic, off the north-west coast of Ireland, a spot little visited save by great flocks of sea- birds, peopled by strange beings with gloomy faces, who have never passed beyond the boundary of its shores, “a race apart, with their own language, their own manners and customs, and their own superstitions,” these last of the most gloomy character. Morna Dunroon, the Colleen, is the daughter of the man who for twenty years in succession has, according to the custom of the place, been elected “King” of the island, as the wealthiest of the people, and the best qualified to take the lead among them. Morna, from her solitary rearing, has all the innocence, simplicity, and warm affections of a child, and is besides perfect in shape as a Grecian statue, with the soft dark eyes and olive-tinted skin that come from the Spanish blood that flows in her veins. She saves the life of a shipwrecked sailor, washed half-dead upon the beach, the only survivor from his ill-fated vessel. This Emile Bisson is a French merchant captain, a man with a fair face, a splendid physique, and a certain winningness of manner, but, in truth, what Dr. Newman calls a “bad imitation of polished ungodliness,” utterly selfish and unprincipled, with views of life formed on what he has seen and heard in the casinos and cafés in which his time has been spent when not at sea. But sorry divinity as he is, he seems god-like in Morna’s eyes, and her heart is yielded to him unreservedly, whilst he, fascinated for the moment by the beauty of the belle sauvage, and finding that in her rustic simplicity she will not hear of those relations between them which he in his superior civilisation thinks the most natural and fitting, is at last impelled into marrying her, and carrying her off to his usual quarters in Normandy, that is to say, into what for Morna is another world. How, when he is tired of his fancy, and caught by a new beauty, he repudiates the tie between himself and Morna, and puts her from him with an almost incredible baseness and brutality,—being even ready to hand the girl over to his mate, who loves her in his own fierce way, and is eager to marry her—is told further on, and a very sickening story it is, though Morna’s bewilderment and dismay before the fact which she can neither understand nor ignore, that Bisson has ceased to love her, is painted with some fine and subtle touches. How Morna finally escapes the meshes of villany into which she is for awhile entrapped, and makes her way home to eagle Island, we must not attempt to tell here, any more than the details of the terrific storm which avenges Morna’s wrongs by again wrecking Bisson, this time with fatal result, on the Creag na Luing—an episode, this last, which from its extreme unlikelihood, we think, rather a blemish on the book, which had much better have closed with the unlucky heroine’s restoration to such peace as was possible for her. She is a very fascinating conception, and drawn with great truth and tenderness of feeling. We are not able within out limits either to do justice to the many excellent scenes and descriptions in the book or to call attention to what struck us in reading it as weak points, but we can have no hesitation in classing it amongst those books of the day that are pre-eminently worth reading. ___

The New York Times (20 April, 1877 - p.2) THE DARK COLLEEN. A Love Story. By the author of the “Queen of Connaught.” New York: LOVELL, ADAM, WESSON & CO. 1877. If William Black’s Princess of Thule should be cast in more vivid colors, and in place of the young Englishman one were to imagine a French sea captain, in place of Sheila an Irish peasant girl named Morna, one would have something very much like the present novel. It has power of a certain kind, and deals with unusual people—the inhabitants, namely, of a lonely member of the Western Isles. The people of Eagle Island are Irish fishermen, heavy, ignorant, and brutal, who have a local government of their own, and further, obey their parish priest, except when his creed interferes with certain favorite superstitions. Bisson is a Frenchman who is washed up from a wreck, and when about to be put to death by the fishermen, who fear that otherwise evil spirits will infest the island, is saved by Morna Dunroon, the daughter of the headman or elective chief. The stay of the stranger is a further complication, for the fishermen attribute to his influence a bad harvest and a barren fishing season. In order to mollify them and to keep her father in as chief of the island, Morna agrees to dive on a certain night for a mysterious water-flower growing on the sea bottom at a haunted spot on the coast. This she does, and the flowers are solemnly sowed in the earth to propitiate the fairies. Bisson falls in love with Morna, marries her, takes her to France, and tires of her. He tries to send her off, but she escapes, and returns only to find that he really cares no longer for her. At the last, another shipwreck throws him again on Eagle Island, where his deserted wife has taken refuge, but this time he is dead. The story is evidently based on personal knowledge of the wildest Irish fishing population, and many Irish words and expressions are to be found in the text. ___

New-York Daily Tribune (12 June, 1878 - p.4) PERSONAL. Miss Jay, the sister-in-law of Robert Buchanan, is the author of the novels “The Queen of Connaught” and the “Dark Colleen.” |

|

|

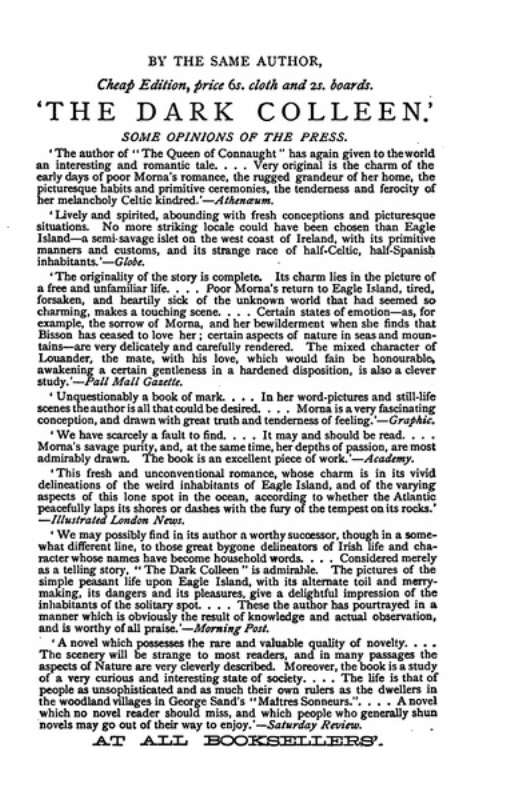

[Press notices for The Dark Colleen from Madge Dunraven (London: Richard Bentley and Son, 1879).] _____

The Examiner (4 October, 1879) MADGE DUNRAVEN.* WE must unwillingly confess to being somewhat disappointed with this second work of the author of the “Queen of Connaught.” For her first book was full of promise which we will not say has been quite unfulfilled, but has certainly not been fully carried out in “Madge Dunraven.” She is a wild Irish girl transplanted to the uncongenial atmosphere of an English village, with her uncle and cousin Conn, by Mr. Aldyn, the rich rector of Armstead, whose dead sister was Mr. Dunraven’s wife. We see a great deal of Mr. Aldyn in the first part of the book, when he goes to Shranamonragh Castle (why such terrible names?), near Ballymoy, to his sister’s funeral, and is much amazed at the scenes he witnesses, as indeed will the reader be when he reads of them. He pays off the mortgages on Shranamonragh, and settles the family in a nice little cottage near his own rectory. So far we must admit that, though the author distinctly dislikes Mr. Aldyn, and wishes us to do so, our narrow Saxon sympathies make us prefer him to the thoughtless Dunraven, although the latter has fine black eyes, and his kitchen is open to every beggar, while the hypocritical clergyman, who professes to teach Christian charity, is yet unaccountably unwilling that tramps should carry off his spoons, and churlishly bars his doors and windows at night. However, of this more anon. Of course having given that Mr. Aldyn has a son named George, who is to marry Miss Rosamond Leigh, the ward of Lord Rigby, it follows, as night the day, that George Aldyn falls in love with Madge Dunraven, and is anxious to get off his previous engagement. Conn, the wild young Irishman, is enchanted by Rosamond, the heartless coquette, and meets her clandestinely in Rigby Park. Up to this point his cousin Madge has been unobtrusively in love with him, but when he confides to her his admiration for, and meetings with, the lovely but heartless English girl, she resolutely suppresses her affection and resolves to look upon him in future as a brother. One evening in a poaching affray Lord Rigby is killed, and Conn, who is returning from one of his stolen interviews with Rosamond, is arrested by the villainous head keeper, John Scott, and charged with the murder. He is tried at the next assizes, and Rosamond, the only person who could prove an alibi, calmly swears his life away, which is no worse than we expected from her. For we have always noticed that when authoresses—we think we are hardly wrong in attributing “Madge Dunraven” to a lady—describe a bad woman, they make her much worse than any man would. How Conn escapes the “swinging” with which John Scott threatens him we will not betray, nor how the tale ends, for we have told as much of the plot as we dare without incurring the displeasure of both author and reader. It has already been remarked that we are clearly intended throughout the book to warmly sympathise with the untidy, down-at-heels, careless, but kindhearted Irish family, and to dislike the stiff, rigid, unfeeling English people. The author has so far succeeded that we do very much like Madge and Conn; but she has not succeeded in making our cheeks burn with indignation at the hard- heartedness of the Saxon. Such a scene as one described, in which a wretched returned convict is hunted down by the whole village and nearly stoned to death, is all but impossible in an English village, Indeed, it is sufficiently clear that the author knows more of Irish country life than of English. No person like John Scott, the wicked keeper, ever existed except on the stage of a transpontine theatre; for people in real life have some reason for their hatred, and don’t bring false charges against innocent persons without some motives. The behaviour of the keeper is, throughout, perfectly unaccountable; nor is at all clear why Lord Rigby was murdered. We are, indeed, informed of the cause of the murder in the third volume, but in the second one we had been told that it was a mistake. In this, as in many other points, the author has been careless in revision. Madge is first introduced to us in Rigby Woods plucking violets and primroses, yet when she emerges on the high road she sees fields of ripening corn. The same evening the nightingale is heard. We are sure that the author knows that violets and primroses bloom in early spring, while the nightingale seldom sings until they are long faded, while the corn, even in the most favourable seasons, declines to ripen until later still. A terrible discrepancy in hours occurs on page 225, vol. i., where Conn takes four hours to ride two miles; and further on, Conn is committed for trial on the very flimsiest of evidence by one single magistrate, not even assisted by a clerk in dispensing law and justice alone in his own house. “O fortunata nimium!” can we say of our author, who has so little knowledge of our rural magistracy, their fear of responsibility, their timidity, their absolute abhorrence of doing anything at all except on the bench. A committal such as here described is, fortunately or unfortunately, quite impossible in England. *Madge Dunraven. By the Author of the “Queen of Connaught.” (Richard Bentley and Son.) ___

The Academy (1 November, 1879) NEW NOVELS. Madge Dunraven. By the author of “The Queen of Connaught.” (R. Bentley & Son.) POWER and pain are the leading characteristics of the new Irish story by the author of The Queen of Connaught. Such an amount of physical suffering and mental agony has not for many a year been compressed within the three volumes of an English novel. Nearly every character in them is in a state of torturing struggle — Madge Dunraven, the heroine, with her oath to a homicidal outcast; the good-natured squireen, her uncle, with Irish poverty and English conventionalities; Conn, her cousin, with death and his love for a perjured “Madonna-like” sensualist; that heartless beauty, Rosamond Leigh herself, with her fear lest her secret indulgence in warm embraces should be discovered, and her terror for the just wrath of the man whom she has betrayed almost to death. The most wretched creature of all is the outcast, Matthew Dalton, who has been at war with Fate all his life, and whom, even at the last, Fate disappoints by making an accident of the death at his hands of the man who has ruined his sister. This account of one of his numerous plights may be said to be the keynote of the novel:— “The lightning flashed into his eyes, and almost blinded him; the heavy rain fell like a torrent upon his threadbare coat; the thunder pealed loud above him. For a moment he veiled with his hand his dazzled, half-blinded eyes, then, as the light quivered and faded, leaving the prospect dank and blackened by the heavy streams of rain, he thrust himself farther under the hedge, in the hope of finding shelter. But the heavy raindrops penetrated the thick hedge and soaked his skin; the dusty road was already thick with brown mud; every rustle of the boughs shook down an additional shower. Still, there was no better shelter nigh, and to make his way now towards the village would be madness. So he drew up his knees, crept closer beneath the rain-sodden hedge, while the water ran in a stream around him from the turned-down brim of his old felt hat.” If, however, this story is till nearly the close one vast wilderness of woe, there are no weaknesses in it. Madge and Conn are true to the life, and smack of the soil, superstition, and fervour of Ireland. Rosamond Leigh—a Cleopatra without the full courage of the flesh, at least in these volumes—though repulsive, is powerfully drawn. The most unsatisfactory character is Rector Aldyn, the English uncle of the young Dunravens. In the first volume he is simply a weak, fanatically circumspect, and not very warm-hearted man, and it is inartistic to make him degenerate in the third into little better than the hypocritical “old rogue” and “devil” that the soured and soaked Dalton would make him out to be. The trial of Conn for murder is in style an advance on anything that has yet been given us by the author of The Queen of Connaught, who moreover proves that she has not lost her art of describing the reckless ways, and entering into the soft hearts, of the Irish peasants. ___

The Morning Post (3 November, 1879 - p.3) MADGE DUNRAVEN.* The first impression which is left on the mind by this decidedly clever, if somewhat painful, novel is that it would have made a much better play. The author’s chief merit is dramatic force, and there are situations in the story which, comparatively tame in narration, would be powerful to a degree when expounded by a competent actor or actress. It is not in the strict sense of the term an Irish story, because the major part of the action—indeed, all that bears most strongly upon its legitimate interest—takes place in this country; still, as the principal characters hail from Connaught, and as the only other tolerably agreeable person in the novel is intimately connected with them, it may be classed amongst the works of fiction belonging to the sister island. * Madge Dunraven: A Tale. By the author of “The Queen of Connaught,” &c. 3 vols. London: Richard Bentley and Sons. ___

The Pall Mall Gazette (21 November, 1879 - p.12) “Madge Dunraven.” By the Author of “The Queen of Connaught.” Three vols. (Richard Bentley and Son.) “The Queen of Connaught,” if it did not open up new ground to the novel reader, at all events introduced him again to a kind of novel which has been almost unknown since the days of Lever; and the undoubted success which attended its production was as much due to the freshness and novelty of the story as to the vigour and raciness of the author’s style of writing. In “Madge Dunraven” we have again a good many of the same qualities which were manifest in “The Dark Colleen” and “The Queen of Connaught.” The peculiarities of the Irish characters are brought out in all these books with singular force; and if the scenes of Irish eccentricity are sometimes a little extravagant, they are always picturesque and striking. The charming scenes of peasant life upon Eagle Island, which did so much for the popularity of “The Dark Colleen,” and the similar scenes in the earlier novel where the society at O’Mara Castle is described, have, however, no exact parallel in “Madge Dunraven;” and to this extent the last of these novels is the least entertaining of the three. The author is tempted to bring his Irish family to England, where he entangles them with the kind of incidents one finds in an ordinary commonplace novel; and his peculiar power of describing Irish life and scenes is thus to some extent rendered unavailing. Madge Dunraven is a heroine of the kind that Lever or Carleton used to describe so well. Brought up in the Far West, she is impulsive, warm-hearted, and unconventional; and the best portion of the story describes the difference she and her foster-father find between the heartiness and happy poverty of their neighbours round Shranamonragh Castle and the cold etiquette and selfish wealth of the English gentry among whom they are thrown. Mr. Dunraven comes to England with the object of retrieving his fortunes, bringing with him a flock of dependants, and he shocks the English people among whom he settles by his utter indifference to all class-distinctions. On the other hand, Madge and her foster father and brother are annoyed at the dishonesty and meanness which they see on all sides in England. Madge does not “understand that the life which they led in Ireland could not be practised here. Ever since she could remember Shranamonragh Castle had been a refuge for the starving and destitute; any wandering beggar could rest his weary feet at their threshold, or, entering in, allay the pangs of hunger and cold.” Now, however, she finds that if she asks a beggar into the kitchen, he is pretty sure to steal the spoons or the table-cloth, and that her English friends will only laugh at her and tell her that she deserves to be so served. Her English cousin says to her, “Christian charity is all very well theoretically, but practically it won’t do. Let every man take care of himself, and the devil take the hindmost.” English charity, however, is not quite so theoretical as this; and it may, perhaps, be open to question whether the indiscriminate relief which Madge recommends does not work more harm than good. Be this as it may, Madge convinces herself that in England “the world is out of joint,” and so far as lies within her power she begins the work of reformation. Like the earlier novels from the same pen, the plot of “Madge Dunraven” is eventful and sensational; and it can only be very slightly indicated here. The story is chiefly concerned with the fate of Conn Dunraven, Madge’s cousin and foster- brother, whose love for an English beauty brings him within the reach of what the author terms the “fangs of justice.” Rosamond Leigh, the object of Conn’s enthusiastic if not very wise admiration, is as heartless a coquette as Lady Clara Vere de Vere. She is the affianced wife of young Dunraven’s cousin; but nevertheless she tempts Conn into holding secret meetings with her, and at the moment of one of these interviews, when “the lovers are locked in each other’s arms,” her guardian is killed in an encounter with poachers; and circumstances which can best be discovered in the story itself fix the guilt of his murder on her lover. To a prosaic lawyer, should such a one read the book, there is a good deal which may appear amusing in the manner in which Dunraven is charged with the crime and in the mode in which his trial is conducted; but the ordinary novel reader will not be inclined to criticise very closely the somewhat strange views of criminal procedure which are here advanced. Following the example of George Eliot in “Felix Holt,” our author avoids setting out all the commonplace incidents of the trial; but a good deal is left in which is neither artistic nor quite accurate. The real murderer was one of the outcasts whom Madge had succoured; and the moment after the commission of the crime he fled to her for protection. Tracked by the police, he forces her to take an oath not to divulge his secret—and except that no sane girl would, or at all events should, consider such an oath binding—the mental torture Madge passes through in her desire to save her cousin, and on the other hand to keep the promise she has sworn to, is exceedingly well described. A way is ultimately discovered for doing both, which no reader would thank us for disclosing here. As a sensational story “Madge Dunraven” deserves to rank with the best productions in this class of fiction; but it has merits, and merits of a higher order to our thinking, independent of its plot. ___

Daily News (3 December, 1879 - p.3) The natural and political conflict between the Irish and English races has long been a favourite and fertile subject for fiction. In itself it is a picturesque attitude, involving endlessly interesting emotional action, and, historically considered, the poet or novelist finds in it almost too abundant and too exciting material ready to his hand. A novel we lately had occasion to notice, “The Lords of Strogue,” was an instance of this difficulty in dealing with the events of the last eighty years, so crowded are the incidents and so painful the interest. The author of “Madge Dunraven” (3 vols., Richard Bentley and Son) has chosen to confine herself to the delineation of the natural antagonism of the two races domestically developed. In religion as well as in national feeling her prejudices are strongly with the Irish Catholic way of thinking, and she uses all her considerable powers of writing and description to enlist the sympathies of her readers on her side. She indulges in no exaggeration, nor in the slightest degree attempts to colour either the Irish people or the Irish landscape with imaginative charm. The opening chapters present a sketch of desolate Irish moorland under the worst aspect of dreary Irish climate, almost as realistic in its way as the famous first chapter of “Felix Holt.” She omits no detail to impress on the reader the exceeding barren desolation of the place, just as later on, when she has to paint the contrasting beauty of an English country scene, she passes over no bright touch of colour or indication of rich culture. The one is a study in Indian ink, life-like, but dull and colourless. The other is a brilliant canvas crowded with gay and lovely touches of brightness and beauty. But the artist loves the Irish moor, and has nothing but cold admiration for the rich English valley. In the same way she does not present Irish character under any intentionally false light. The Sligo peasantry go in rags and prefer bread given to that worked for, the young ladies have a sneaking tendency to leave off their shoes and stockings, and the young gentlemen entertain the vaguest ideas as to the limits between preserving and poaching. But then they all, gentry and peasantry, love a dance and a joke and a glass of whiskey. They have intense attachments, strong feelings, and no belief in the effectual working of the poor rate. It may easily be seen how strongly the dissonant note is struck when the impoverished Dunraven family, uprooted from their native home on the melancholy shore of Ballymoy, are placed in the centre of an English village under the cold protection of a Protestant rector-uncle. Nothing suits them and they suit nobody. The story of their troubled stay on English soil and joyful return to Ballymoy, their rags, their almsgiving, and their whiskey, is not only interesting as a story, but amusing and even instructive as a study of national character and feeling. It is very brightly, freshly, and entertainingly written. The weak point in construction is the rigid adherence of Madge Dunraven to an oath administered to her against her will and without her consent, and her obstinate silence when by speaking she might save her innocent cousin from death. But this is in the character, and from the author’s point of view; and, though it would be in real life a great mistake, its introduction into the story can scarcely be called a literary blunder. ___

The Graphic (6 December, 1879) “MADGE DUNRAVEN,” by the author of “The Queen of Connaught,” &c. (3 vols.: Bentley).—We cannot help thinking that the author has here somewhat mismanaged her play, and wilfully thrown away her trump card. Her strong point, as has been universally allowed, were her sketches of Irish life and character—as witness that picture of the strange life on Eagle Island, which constitutes the real attraction in “The Dark Colleen;” but here, after the briefest of introductions, the Irish trio among the dramatis personæ are whirled away to an inland English country parish, in which, and in the neighbouring assize-town, the scene lies for the rest of the book. Some amusement is, indeed, afforded by the account given of the efforts of Mr. Dunraven, his son Conn, and his niece Madge, to live at Armstead precisely as they had lived at Shranamonragh Castle—how they entertain tramps and beggars on the best the house can furnish, leave doors unbarred and windows unfastened at night, and then are astonished to find that teaspoons, table-cloths, and great coats have mysteriously disappeared in the morning; but, after all, this does not go a great way, and the author seems rather to overdo the contrast between Irish geniality and honesty and English knavery and churlishness. Another fault we have to find with the construction of the book is, that the tragic incident in which its interest is supposed to culminate is allowed unduly to dominate over the rest of the story. That some such catastrophe is coming—is in the air—we are hardly permitted to forget for a moment; and, no doubt, this sense of impending gloom and disaster may be most effective when it is skilfully handled. But then it is not every novelist who can deal with such an element as it should be dealt with, and the misfortune is that if it fails by a nail’s breadth in being impressive, it becomes rather tiresome—as we must own we have found it here. We might, very likely, have been more readily stirred as the author would have had us could we have brought ourselves to feel more real belief and interest in her characters; but in the delineation of character she does not seem at all at her best. No doubt she can give us strongly marked individualities, such as Morna and Bisson; but she appears at a loss when she would work out such ordinary men and women as one might anticipate rubbing shoulders against in the chances of daily life. We are told that Conn is very handsome, and we know that he is very unfortunate; but he remains a mere name throughout; whilst Madge herself, the principal figure in the story, Madge, the tender, admirable, heroic maiden, is never seen, except in the vaguest outline. The one personage in the tale of whom most might perhaps have been made, is the perjured beauty, Rosamund Leigh, though that type of woman, at once heartless and sensuous, is no longer a novelty in fiction. As readers will have seen, we have said a great deal in dispraise of the book, for it is one well worth while finding fault with, being in point of style, general ability, and most of the gifts that go to make the novelist, much in advance of the run of fiction of the day; and if the writer will only be true to herself, we are persuaded she may do much finer work than any she has yet given to the world. We cannot, however, take leave of her without one parting shot. We should strongly recommend her, when next she attempts to describe the proceedings in an English court of justice, to try to make them less grotesquely wild and impossible; and it is certainly odd enough that, though she repeatedly lays stress on the fact that Madge is a Catholic girl, it does not seem to have occurred to her that the first thing such a girl placed in such a dilemma as Madge is between her oath to the outcast not to betray him, and her obligation not to permit an innocent man, her own near and dear relative, to suffer for a crime she knows he has not committed, would do, would be to lay the whole matter before her spiritual director under seal of confession. A “few words emanating from an intelligent mind” would have soon solved Madge’s doubts as to her conflicting obligations, and saved herself and her friends many weeks of anxiety and heartache. ___

Harper’s New Monthly Magazine (January, 1880 - p.313-314) As a rule the genuine novel-reader prefers to enjoy without previous enlightenment the agreeable surprises by which an ingenious novelist contrives to intensify the interest of a story, and renders small thanks to the officious critic who robs it in advance of its freshness and flavor by an outline of its plot and incidents. Out of deference to this feeling we shall merely give our general impressions of the novels of the month. One of these, Madge Dunraven, is essentially an Irish tale, although the scene is shifted very early to England, and the narrative has little of the rollicking abandon of the conventional Irish novel. The characters for whom our sympathies are most keenly excited are indeed Irish of the Irish in their tastes and feelings; but the alchemy of love converts them to many English and thoroughly un-Irish ways, while their Irish virtues exert a mellowing influence upon their English associates. The author describes a “Castle Rackrent” which is no less dilapidated, and is even more genial in its dilapidation, than Miss Edgeworth’s. The narrative is seasoned with a double love story, several poaching adventures, a brace of homicides, and an exciting trial scene. It is, however, less sensational than might be inferred from these rather startling incidents. ___

The Spectator (23 April, 1881 - p.23) Madge Dunraven. By the Author of “The Queen of Connaught.” (Bentley.)—In this very Irish novel, Mr. Dunraven, his son Conn, and his niece Madge, are brought over from their native Ballymoy and their ancestral castle of Shranamonragh to the English village of Armstead, of which their kinsman and bringer-over, the Rev. Mr. Aldyn, is rector. The high jinks played by this little Irish colony in their strange English surroundings supply the action of the story. Such plot as there is consists in Conn’s trial for murder and his deliverance by confession on the part of the real criminal, who has been worked upon by Madge; and the best “point” in the book is the contrasted possession of a secret by Madge, on the one hand—who has sheltered the real murderer, and been sworn to silence by him—and by Rosamond Leigh on the other, who knows that Conn, at the time “when the gun had been fired which had shot down Lord Rigby,” was “holding her (Rosamond) in his arms, and kissing her tremulous lips.” Madge and Rosamond Leigh, the impulsive Irish girl and the cold English one, are contrasted; and, again, the Irish Conn and the English rector’s son, George Aldyn. But the contrasts are somewhat stagey, and the absence of reality in the drawing of the various characters is not made up for by a painful realism that is somewhat suggestive of careful scene-setting and elaborate stage-direction. Nor is this realism always very exact. Madge, for instance, after sitting with bare legs and feet “in the middle of a grassy dell, which was set close upon the margin of an extensive wood,” where “the grass was very thick and very tall—but now and then the soft westerly wind swept the tall blades apart, revealing, as it did so, glimpses of deep purple wood violets, tufts of pale primroses, and delicate patches of green and golden woodland moss”—climbs “up to the top of a grassy bank which shut in the highway,” and “looks around.” In the interval of her climbing, the spring has given way to late summer: “all seemed one luminous vision of yellow cornfields, dark, waving woods, green meadows, rich with after-math,— gardens laden with fruit.” And if we cannot praise the painting of nature, what is to be said of the description of passion? Of this, there is plenty in the book; but it is passion of the torn kind, which becomes wearisome, even if it has ever begun to be moving, and utterly unrelieved or supplemented by the slightest conception of the humorous or the grotesque. People’s eyes, on the shortest notice, “burn like balls of fire;” the English Judge, on Matthew Dalton’s confession in court, orders him into custody, “in a voice trembling with passion;” an irritated gamekeeper laughs “with the ferocity of a mastiff on the chain;” and Conn, in a farewell interview with Rosamond Leigh, “with his right arm held her firmly against his breast, with his left hand raised her face; then, in a hot frenzy of passion, he covered her face, her cheeks, her lips, with kisses,” with the sublimely bathetic result that “her face was scarlet; she rubbed her:scented handkerchief across her lips, and stared at him.” The writer has done much better than this before, and will, we hope, do better again. |

|

|

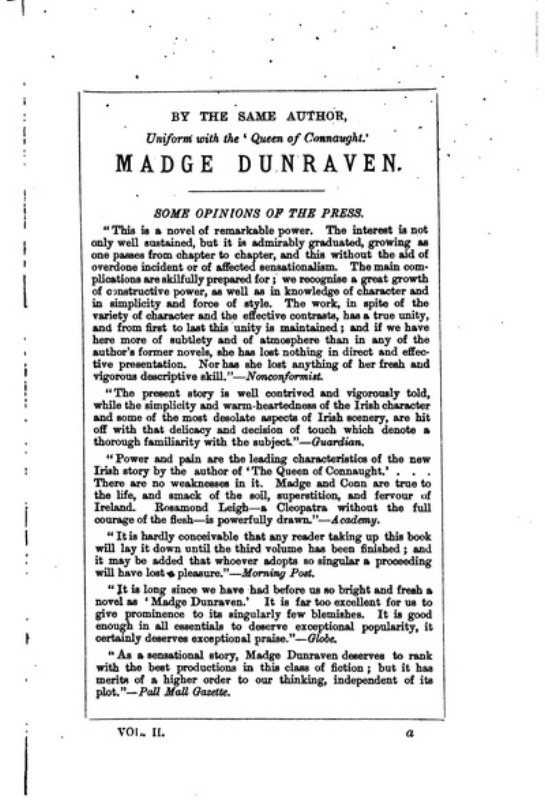

[Press notices for Madge Dunraven from My Connaught Cousins (London: F. V. White and Co., 1883).] _____

Harriett Jay Book Reviews continued The Priest’s Blessing (1881) to Two Men And A Maid (1881) or back to Harriett Jay Bibliography

|

|

|

|

|

|

|