|

Play List: 4. Corinne 7. The Mormons 9. Lucy Brandon 10. Storm-Beaten 11. Lady Clare 13. Bachelors 14. Constance 15. Lottie 16. Agnes 17. Alone in London 18. Sophia 19. Fascination 20. The Blue Bells of Scotland 21. Partners 24. Angelina! 25. The Old Home 26. A Man’s Shadow 27. Theodora 29. Clarissa 30. Miss Tomboy 32. Sweet Nancy 33. The English Rose 36. Marmion 37. The Gifted Lady 38. The Trumpet Call 39. Squire Kate 40. The White Rose 42. The Black Domino 44. The Charlatan 45. Dick Sheridan 47. Lady Gladys 48. The Strange Adventures of Miss Brown 49. The Romance of the Shopwalker 52. Two Little Maids from School ___ |

|

ROBERT WILLIAMS BUCHANAN (1841 - 1901) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

THEATRE REVIEWS 10. Storm-Beaten (1883)

Storm-Beaten Film: God and the Man, directed by Edwin J. Collins, 1918 (based on the original novel).

The Referee (14 January, 1883 - p.2) The Reade-cum-Pettitt régime at the Adelphi will terminate on Saturday, February 17th, and then the unlucky Scotch poet, Robert Buchanan, will be allowed to come to the scratch again, and to have another try for success. Up to now he has produced only failures. The last poor stuff he gave to the stage was “Lucy Brandon,” and in the words of the song, “He’s never done anything since.” In the cast of his new piece—which I hear is to be in six acts—will be Charles Warner, J. H. Barnes, Beerbohm Tree, Amy Roselle, Harriet Coveney, and Clara Jecks. With such talent to help him even Robert Buchanan ought to be able to score. Charles Warner and J. H. Barnes will have one whole act to themselves in this new play. It is on the ice, and they snowball each other, and then one dies. There need not be much difficulty in guessing which will have to die before the last act, C. W. or J. H. B. ___

The Dundee Courier and Argus (15 January, 1883 - p.3) I understand that Mr Robert Buchanan is making a very desperate effort to effect a triumph with the play which he has written for the Adelphi Theatre, and which the Messrs Gatti have determined to produce without regard to cost. Mr Buchanan has failed so often as a dramatist that his present attempt is an affair almost of success or despair. Unfortunately this clever Scotch poet has many enemies on the London press. ___

The New York Times (8 February, 1883) . . . Mr. Robert Buchanan is to have “a last chance.” A poet of undoubted power and a successful novelist, he has made several conspicuous failures as a dramatist. This would seem to be a recommendation, however, in England, where the more frequently a writer for the stage fails the more he may be said to succeed. Managers and the public have, however, grown tired of Mr. Buchanan, who, judging from much of his literary work, and taking into consideration his many failures, ought at last to know something of the requirements of the stage. He is to have a new work produced at the Adelphi about the middle of next month. One of the strongest scenes in it will be between two men, (the characters by Warner and Barnes,) at the end of which one of them is killed. It is not rash to guess that it will not be Warner who dies, for he is the leading man at the Adelphi. Although Buchanan has made a host of enemies in the press and in literature, he may count upon fair play. Anybody who can give to the English stage an original and wholesome drama will always find a hearty and appreciative welcome at the hands of the public. ___

The Illustrated Sporting and Dramatic News (10 February, 1883 - p.6) MISS EWERETTA LAWRENCE plays a scene of Romeo and Juliet on Thursday morning with Mr. Bellew for that actor’s benefit. Her success as Pauline gives interest to this bolder effort. This young lady will also play the part originally intended for Miss Harriett Jay in Mr. Buchanan’s play at the Adelphi. ___

The Sheffield Independent (24 February, 1883 - p.12) Mr. Robert Buchanan’s new romantic drama in preparation at the Adelphi Theatre, London, is an adaptation of the same writer’s novel entitled “God and the Man.” It will be produced on the 10th of March. Miss Eweretta Lawrence, the young lady who made her debut at the Gaiety the other morning as Pauline, in “The Lady of Lyons,” will play a part in the piece. The principal characters are assigned to Mr. Chas. Warner and Miss Amy Roselle. ___

The Edinburgh Evening News (1 March, 1883 - p.2) THE Lord Chamberlain’s latest exploit is marked by all that superiority to common-sense which is naturally to be expected from an official whose existence and whose functions form a standing practical joke. In the exercise of his power, left to him by a confiding legislature of preventing the production of any play which he dislikes on any ground whatever, this functionary has objected to the title of Mr Robert Buchanan’s new play “God and the Man,” and consequently the play must be produced with a new title or not at all. To realise the full absurdity of the situation it is only necessary to remember that Mr Buchanan’s play is a dramatisation of his own novel with the same title. The title certainly does not impress one as having been chosen by either a wise philosopher or a sensible man of the world; and it need not be contended that the direct loss to dramatic literature would be great if “God and the Man” were suppressed for good and all; though M. Hugo, whose theism is of a similarly crude sort to Mr Buchanan’s, has produced some sufficiently strong plays. But all question as to the permissibility of the title is made idle by the fact that Mr Buchanan has been allowed to put his title on his romance and publish that as he pleases, whether in book form or in popular periodicals. Can anything be more exquisitely absurd than the system of literary regulation which, allowing a writer to print a given title on his book and on every page of his book, steps in to prevent his giving the same title to a dramatised version of his story? It appears that it was not Mr Buchanan’s intention to use his catchpenny phrase for advertising purposes; but nothing, it appears, will satisfy the Lord Chamberlain short of the complete suppression of a title which might possibly disturb the refined nerves of his dear friend Mrs Grundy. Having seen the play, his lordship is, of course, aware that the deity is not made one of the dramatis personæ. It is simply that his fine taste, nourished in the atmosphere of levées and the highest life below stairs, is offended by Mr Buchanan’s unconventional use of a name which, as he must have heard whispered, is used with deplorable frequency, and with much more than Mr Buchanan’s indecorum, by a large section of the patrons of the drama his lordship regulates. And, his lordship being shocked, the author and the British nation must make his taste theirs in so far as regards their theatre-going. They may have Mr Buchanan’s romance on their tables; but when they go to see it dramatised they must have another title on their programmes. It will perhaps occur to the theatre manager concerned that an appropriate substitute for the title of “God and the Man” would be “The Lord Chamberlain and Mr Buchanan;” and it is conceivable that a highly realistic drama might be written to suit, which should be rather more entertaining than Mr Buchanan’s. But then his lordship would not allow it; and his lordship’s power is of an immortal order. His office is the most senseless anomaly in English administration, and that is saying a good deal; but there is not the slightest prospect of the Government taking action to put him down. All nuisances and outrages discoverable by human ingenuity, save this, are brought under the notice of the Government by members of Parliament. No plots are directed against the Lord Chamberlain; no Home Ruler maligns him. It may well be questioned whether British drama can possibly rise to any literary dignity while it is thus controlled by Her Majesty’s major domo. |

|

|

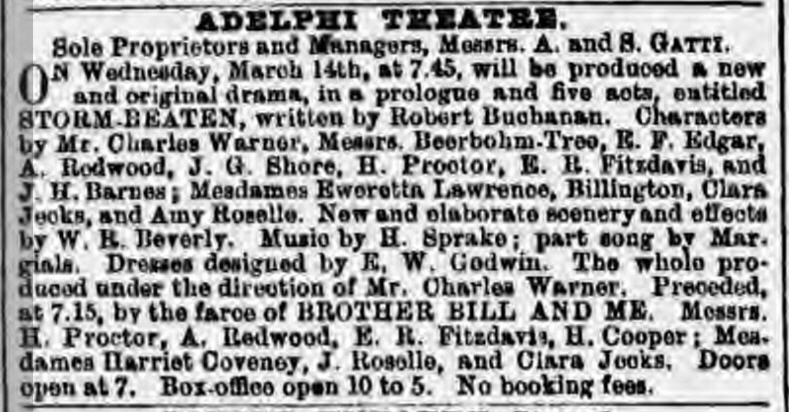

[Advert in Reynolds’s Newspaper (4 March, 1883 - p.4).]

The Stage (9 March, 1883 - p.10) Storm Beaten, the new drama to be produced at the Adelphi on the 14th inst., includes in the cast Messrs. Charles Warner, J. H. Barnes, and H. Beerbohm Tree, and Mrs. Billington, Miss Laurence, and Miss Roselle. The original title given to the piece by the author, Mr. Robert Buchanan, viz., God and the Man, was, it seems, rather too strong for the taste of my Lord Chamberlain, hence the alteration. ___

The Morning Post (15 March, 1883 - p.3) ADELPHI THEATRE. A terrible story of hatred and revenge brought at last to a comfortable arrangement is that of Mr. R. Buchanan’s new drama entitled “Storm Beaten,” which was produced at this theatre last night. The play is founded upon a novel by the same author bearing the strange title “God and the Man.” The scene is laid in a rural district of England. The time is about a century ago. Between the families of the Orchardsons and the Christiansons—the former aristocrats, the latter yeomen—there has raged for generations a desperate feud. Notwithstanding the difference of their social positions, the members of these hostile houses have frequently crossed one another’s paths, and always in a sense the most unfriendly. Richard Orchardson makes perfidious love to Kate Christianson, ruins, and leaves her. Thenceforward her brother Christian Christianson, dedicates his life to one purpose and one only—vengeance on the betrayer of his sister. What complicates the dramatic situation and gives additional fuel to the frenzy of the avenger is that his own sweetheart is solicited in marriage by this same man on whose destruction he is bent. On sea and shore the two men are perpetually together, for the young yeoman follows his victim like his shadow and vows to hunt him down. Their awful adventures are the business of the plot. They are shipwrecked in the Arctic seas, thrown upon ice floes, and at last cast away upon a desert island. There they stand face to face, the only inhabitants. But when it comes to the point and vengeance is within his grasp Christian cannot find it in his heart to slay his enemy. The sense of loneliness and desolation all around unnerves him. He cannot surrender the sound of a human voice, the touch of a human hand. So, when Richard falls ill and seems verging to death, Christian forgives him, attends him through his illness, and saves his life. Presently a ship arrives. The castaways are taken on board and brought back to England, where, of course, the wrongs of the forsaken girl are redressed, Richard turns over a new leaf, Christian is restored to his sweetheart, and all ends happily. The scenery, by Mr. W. R. Beverley, is exceedingly picturesque. It comprises sylvan landscapes, views of parks and mansions, and, above all, some finely painted pictures of icebergs and frozen seas, where ships have come to hopeless ruin. The two principal characters, Orchardson and Christianson, are impersonated by Mr. Charles Warner and Mr. J. H. Barnes respectively in a style which evokes the warm approval of the audience. The silliness and conceit of Jabez Greene, a poor, half-witted shepherd, are depicted with admirable fidelity by Mr. B. Tree. Miss Roselle, as Kate Christianson, acts with touching tenderness, and at times with brilliant passion. Miss E. Lawrence plays Priscilla Sefton, the sweetheart of Christian Christianson, with engaging grace and gentleness, and Miss Clara Jecks is charmingly piquante and vivacious as Sally Marvel, a little village coquette. The play was received with unanimous enthusiasm, and bids fair for a long run. ___

The Standard (15 March, 1883 - p.3) ADELPHI THEATRE. In Storm-Beaten, Mr. Robert Buchanan’s dramatic version of his novel “God and the Man,” a piece admirably adapted for Adelphi audiences has been provided. It is a play of exceptional power. The plot is carried on at least through the greater portion of it by extremely effective incidents; the dialogue is terse and telling, and opportunity is abundantly given for the introduction of those exciting scenes which waken the enthusiasm of impressionable spectators. In some places, it is true, the closeness of the sublime to the ridiculous come perilously near to exemplification. It may be urged against Storm-Beaten also that the horrors are accumulated to such an extent that they cease to horrify and begin to grow tedious, and the drama falls off somewhat in the latter portion. Nevertheless, it does something more than merely answer the main purpose of its production. Claims to be considered a work of art may be asserted on its behalf— claims which will be more readily conceded when a little revision has been bestowed upon it. ___

The Daily Telegraph (15 March, 1883 - p.5) ADELPHI THEATRE. “Storm-Beaten,” produced last night for the first time, is one of those grimly powerful and serious dramas concerning the fate of which it would be rash at the moment to predict anything with absolute certainty. If its rugged and painful power is occasionally in excess of the requirements of the melodramatic stage, and harps too much on a strained and harsh note of pathos, we must not be too hard on the actors, who had throughout a most difficult and trying task to perform; if its seriousness is inclined occasionally to take the tone of sermonizing, we must not, on the other hand, be too severe on the author, whose earnestness and purpose are at any rate better than much of the frivolity and mere stage carpentering to which the picturesque stage has too often been devoted. Mr. Buchanan’s weird play has all the storm and stress of old-fashioned Adelphi drama with plenty of modern rhetoric thrown in. A widow who curses the spoliator of her husband’s property, and swears her young children to vengeance on the Bible; a maiden who calls down the vengeance of heaven on the man who has betrayed her trust, and ruined her young and innocent life; a young man who, with all the desperate intensity of which youth is capable, calls upon the God of his fathers to punish the destroyer of his home and the heartless seducer of his sister, are but the figures in a grand central story of awful hate and terrible vengeance. Once upon a time Mr. Robert Buchanan wrote a novel with a purpose—it is his habit to write novels with a purpose, and they are both powerful and popular. The novel in question which dealt with the hate as between man and men, the ineradicable hate bred of family feuds—the kind of hate that George Eliot described so wonderfully in the “Mill of the Floss” in connection with the Tulliver family, with its desperate Tom Tulliver and its wild, loving Maggie—is called “God and the Man.” It is certainly a striking novel as novels go, alternately tender and strong, descriptive and dramatic. The story on which Mr. Buchanan has founded “Storm-Beaten,” or on which “Storm-Beaten” is founded—it does not much matter which—is certainly more interesting than the play. It is at least consistent to human nature, which the play very often is not. It works out a problem satisfactorily and to a definite conclusion which the play shirks or refuses to do. But after all this is immaterial. It is not necessary to read Mr. Buchanan’s novel in order to enjoy his drama; in fact we should not advise such a course except for showing what a far better novelist Mr. Buchanan is than a dramatist. In the one his prolixity is a charm; in the other it is a decided hindrance. The story to be told on the stage, with all the ramifications and elaborations possible, cannot bear the weight of six acts. Repetitions have to be resorted to, and variety of interest is scorned. But as a novel it fills its space excellently well, and the reader needs no skipping. ___

Glasgow Herald (15 March, 1883) MR BUCHANAN’S NEW DRAMA. (FROM OUR OWN CORRESPONDENT.) London, Wednesday Night. ___

The Edinburgh Evening News (15 March, 1883 - p.4) MR BUCHANAN’S NEW DRAMA. Mr Robert Buchanan’s new drama “Storm Beaten,” produced before a large audience at the Adelphi Theatre, London, last night, is an adaptation of the story of the author’s romance “God and the Man.” The story, Mr Buchanan has intimated, was written “with a particular purpose,” and he adds, “it descends to what some critics call the heresy of instruction.” The special purpose in the present case is “a study of the vanity and folly of individual hate.” The hero, Christian Christianson, nurtures against the villian, Richard Orchardson, a hereditary hate, aggravated by Orchardson’s conduct in seducing and deserting Christian’s sister Kate, and in attempting to win the girl whom Christian loves. This hate is fanned by a variety of circumstances, but at length gradually dies out when the two men are wrecked together on an ice-floe, and the villian comes to the point of death and repents. In the novel he dies, but in the play he recovers to marry Kate Christianson. It is doubtful (says a London correspondent) whether Mr Buchanan has rightly judged the taste of a popular audience in thus abandoning his original conception. The play went well last night, with every symptom of appreciation from the house, until the fourth act (there are five acts and a prologue) when the interest began to flag with the reconciliation of the two foes, and the final issues of the drama became too obvious. Viewing the production as a whole, Mr Buchanan can be congratulated on having scored a success which will keep the stage of the Adelphi for many days. He has found a most admirable exponent of his leading character, Christian Christianson, in Mr Charles Warner. The part requires no delicate artistic shading, but is just that boldly-sketched, highly-toned portraiture in which Mr Warner is seen at his best. The cast includes Miss Amy Roselle, Mr J. H. Barnes, Mr J. G. Shore, Mrs Billington, and other well-known names. The scenic effects also do justice to the play. One of them (the breaking up of the ship by icebergs) roused the audience to considerable excitement, and must have recalled to some the old Adelphi sensation of the “Sea of Ice.” The audience gave hearty recalls at the close of every act to the leading artistes, and, when the curtain fell, their warm acclamations to the author, who duly bowed an acknowledgment. ___

The Evening Telegram (New York) (15 March, 1883) “STORM BEATEN.” First Performance of Robert Buchanan’s New Play. A SUCCESS AT THE LONDON ADELPHI. Hate and Vengeance Ending in Reconciliation. A WONDERFUL ICE SCENE. VIA FRENCH ATLANTIC CABLE TO THE EVENING TELEGRAM. LONDON, March 15.—The much anticipated drama by Robert Buchanan, entitled “Storm Beaten,” founded upon his romance, “God and the Man,” was produced last night at the Adelphi Theatre. It is a play in a prologue and five acts, and its strong cast and elaborate scenic effects, added to its story of thrilling interest, combined to make the first performance exceptionally interesting. It attracted a large and brilliant audience who extended an enthusiastic welcome to it. THE CAST. The cast was as follows:— Squire Orchardson............................Mr. Edgar PURPOSE OF THE PLAY. Hate and vengeance form the purpose of the play, which is mellowed by the wholesome moral of the impotence of human revenge. The hate in question exists between two families, and has been handed down for years from father to son on both sides. In the prologue the cause of the hatred is forcibly depicted. The bullying Squire Orchardson forecloses a mortgage on the farm belonging to the widow of an old tenant, Farmer Christianson. The pitiless act of the Squire is aggravated by his expression of pleasure when he sees the family begging for bread. The widow swears Kate to vengeance, and this brings the prologue to a close. THE FIRST ACT. The first act opens on the May Day revels. Richard Orchardson and Christian Christianson becomes unconsciously worse enemies than the wildest dreams of their forefathers could have foretold. Both love Priscilla Sefton, the daughter of a blind Wesleyan Methodist preacher. Unknown to either Christian or his mother, who dies of a broken heart, Richard has secretly loved Kate Christianson, whom he has betrayed under a promise of marriage. The charming scene of the crowning of the May queen is here introduced, with a pastoral ballet and the May pole brought in. By a grim satire of fate, Kate, who had been cast aside by her faithless lover in favor of Priscilla, is crowned queen. The story of the heartless betrayal is divulged to Christian by Priscilla, who has been Kate’s confidant. The name of the betrayer, however, is not disclosed. THE SECOND ACT. This leads to the second act, where Sefton, who has been the guest of the Squire, is on the eve of going on a sea voyage for the benefit of his health, accompanied by his daughter. The Squire learning that the preacher is rich urges his son to press his suit, ultimately deciding that Richard should take passage on the same ship as the Seftons. This intention on the part of Richard coming to the ears of Kate, who has given birth to a child, she implores him to keep his promise and not forsake her. Ruthlessly flinging her aside he flees, leaving Kate in a swoon, in which state she is found by Christian, who learns for the first time that his sister’s betrayer is his old, hated rival. At this point the play is intensely dramatic and effective. With hand uplifted to heaven, Christian calls upon God to deliver into his hands the villain who wrought so much sorrow and calamity in his family. This curse delivered with desperate earnestness, mingled with the hysterical shrieks of Kate, who apprehends the possible dreadful fate of the man she loves, is a most powerful situation in the piece and brings down the curtain on the second act amid loud and ringing cheers. THE THIRD ACT. The third act introduces Priscilla on the deck of the Miles Standish, Richard earnestly pressing his suit and blackening his rival’s character. A sailor, who has closely observed the whole scene, suddenly throws off his disguise and reveals Christian. He instantly flies at the throat of his enemy, but is put in irons for insubordination. Priscilla now knows the infamy of the man who followed her, and declares before him her love for Christian. Richard determines to take the life of his rival by burning the part of the ship in which he is confined. A fine scenic effect is now brought to the support of the play representing the ship on fire. Christian is rescued from the hold just as the vessel strikes an iceberg which enfolds her in huge masses of ice and crushes her. Amid the crash of falling masts and splitting timbers the two enemies are seen on an ice-floe locked in a deadly embrace, each endeavouring to force the other under the water. Richard is struggling in the midst of the broken ice as the curtain falls. THE FOURTH ACT. The weakest portion of the play commences in the fourth act. The incidents are undramatic, tedious and painful. Two hungry and gaunt men are seen to meet each other on a desolate, sterile island. These are Richard and Christian, who have miraculously escaped death from drowning. Christian, seeing the man he hates doomed to die of starvation, cannot deny himself the pleasure of gloating over the sufferings of his enemy. This desire is reversed when Richard is at the point of death. Then Christian implores heaven to save his life on the ground of loneliness. Scarcely has the prayer been uttered when the sound of cannon is heard, and a boat appears. No one knows whether it rescues both or not. THE FIFTH ACT. The curtain rises on the last act to the sound of the church bells ringing an Easter peal. The villagers, with the old squire bringing up the rear, enter the church to celebrate Easterday. Two ladies dressed in deep mourning are seen standing at the door of a cottage opposite. A stranger, roughly clad, appears, evincing considerable emotion when he hears the singing of the Easter hymn. He is addressed by one of the ladies and immediately recognizes Kate. He then discloses himself as her brother. “Where is Richard?” tearfully asks Kate, at the same time recoiling from the embrace of the man she fears is her lover’s murderer. The answer to her question is the immediate entrance of Richard, sound and hearty. He tells her how her brother saved his life and promises to amend the past by redeeming his promise of marrying her. Christian then folds Priscilla in his arms and love is established on all sides, while guilt is, to the detriment of the piece, too easily condoned. So the curtain finally falls on a most unnatural and improbable termination of the story. Such a quarrel should only end—as it does in the novel—in the death of one, instead of both returning as boon companions to the home of their childhood, apparently without the shadow of the memory of the wretched past. ___

The Stage (16 March, 1883 - p.7) ADELPHI. On Wednesday, March 14, 1883, was produced here a new and original drama in a prologue in five acts written by Robert Buchanan, entitled Storm-Beaten. Squire Orchardson ... ... ... Mr. E. F. Edgar Storm-Beaten is designed to depict the folly of individual hate. It is a rugged, picturesque story, and the drama has served the author for the foundation of his novel called “God and the Man,” which was published at the close of the year 1881. The story set forth is briefly this:—From time out of mind a feud has existed between the Christiansons and the Orchardsons. The two families hate each other with an undisguised and uncontrollable passion. The Christiansons are strong of limb but of poor means, whilst the Orchardsons are of a gentler race, and are rich in worldly goods. So that when Christian Christianson and Richard Orchardson both fall in love with Priscilla Sefton, the sweet daughter of a worthy preacher, the family hatred is increased a hundredfold. But the peace and quietude of the village home of the Christiansons is further disturbed by Squire Orchardson’s heir, Richard, who has betrayed Kate Christianson. Dame Christianson dies of grief at her daughter’s shame, and Christian resolves to have the life of the seducer, Richard. Priscilla and her father leave England on board ship, and are followed by Richard, who takes a passage in the same vessel. But Christian also sails in the same boat, as a seaman, and his identity being discovered by a violent attack upon Richard, he is cast into irons. The vessel becomes ice-bound, and Christianson is obliged to give assistance to his fellows. Taking advantage of a blinding snowstorm, he seizes Richard and carries him away from the vessel with the intention of killing him. Christian is the cause, as he thinks, of Richard’s death, but he has had his revenge, and returns to join the ship. But the vessel is out of sight, and he is left alone on an island! Yet not alone, for Richard has miraculously escaped from death. Then ensues the most powerful scene in the play. The two are alone, face to face. Sick almost to death, Richard implores Christian to kill him and end his misery. But Christian spares his life. He is eventually rescued, and returning to England, he finds his sister well and hearty, and Priscilla, who has loved him from the first, is ready to become his wife. ___

The Times (17 March, 1883 - p.5) ADELPHI THEATRE. Mr. Robert Buchanan desires his novel “God and the Man” to be regarded as a “monument of the folly and vanity of human hate,” and with characteristic indulgence for human weakness, he has dedicated it to “an enemy” of his own. As produced at the Adelphi Theatre, under the fantastic title of Storm Beaten, it may equally well serve as a monument of the self-abnegation which a professional moralist may see fit to exercise when he has to subject his doctrines to certain fancied necessities of the stage. The moral of the novel disappears altogether in the play, and in its stead we find the lesson very strongly inculcated that villainy of the deepest dye may, in certain circumstances, become a passport to the highest esteem and consideration. It seems scarcely worth while for an author to preach morality so ostentatiously on one platform only to subvert it so completely on another. The condition of things known in nursery literature as “living happily ever afterwards” is no doubt acceptable as a rule to lovers of the sensational drama, and desirable in itself. But the sacrifice of art and of common sense is a heavy price to pay for it on the stage, and Mr. Robert Buchanan seriously compromises both in the dramatic sequel he has given to the family feud of the Christiansons and Orchardsons. No villany could well surpass that of Richard Orchardson as practised upon Christian Christianson. Besides being instrumental in having him and his turned out of their home, Orchardson shoots Christianson’s favourite dog, seduces his sister, seeks to rob him of his sweetheart, and, on board the “Miles Standish.” not only causes him to be put in irons, but endeavours to suffocate him under hatches. It is not surprising that Christianson, in such circumstances, should owe Orchardson a grudge. The story of their mutual hatred is a powerful one, though set forth at somewhat too great length, and, conducted to the dénouement provided in the novel, it may be regarded as pointing the moral that the author there insists upon. A shipwreck in the Arctic Seas throws both men together upon an ice-floe, where their common suffering, as the only human beings in that dreary waste, thaws the winter in their hearts. Christianson tends Orchardson in an illness, and when his enemy dies he closes his eyes and buries him in the snow with Christian-like charity. Thenceforward Christianson is an altered man. The vanity of human hate, which has had so pathetic and tragic an ending, forces itself upon the imagination; and Christianson’s return to the scenes of his boyhood marks, we can well believe, the close of the family feud. Very different is the turn given to this story in the play. Mr. Robert Buchanan has thought fit to sacrifice his ethical theories for the sake of providing the deserted heroine with a husband, who cannot by any stretch of charity be deemed to be worth having. After some trying experiences on the ice the two men return home as bosom friends, and the only conclusion to be drawn is that Orchardson, by means of his unmitigated wrong-doing, has secured a place in the affections of his friend which he would never have gained as a peaceable and Christianlike neighbour. The public, it must be said to their credit, did not quite relish this sudden conversion of an utterly unworthy scoundrel into an Arctic hero. Orchardson’s return to the arms of the girl he had so basely deserted, and his cheerful resigning of Priscilla Sefton in favour of his friend, called forth on Wednesday night something like a murmur of disapproval; so that the author’s unhesitating renunciation of his own especial doctrines for the sake of a trivial and inartistic stage effect can hardly be said to have had the success he reckoned upon. ___

The Era (17 March, 1883) THE LONDON THEATRES. Formerly little activity in the theatrical world was apparent on the eve of Easter, but, possibly in view of the presence of many visitors to the metropolis attracted by the University Boat Race, several managers have varied their programmes, while morning performances have been unusually numerous during the week. Mr Buchanan’s new elaborate drama called Storm Beaten was produced at the ADELPHI on Wednesday night, the house being closed on Monday and Tuesday evenings for night rehearsals. At the PRINCESS’S the very successful drama of The Silver King passed on Thursday night its hundredth representation. The GAIETY achieved a triumph on Monday evening, when Mr Burnand’s merry burlesque- drama of Blue Beard commenced what promises to be a lengthy career. The LYCEUM, the COURT, and TOOLE’S THEATRE will be closed during next week, to reopen on Easter Monday. The last nights of Mr John S. Clarke and The Comedy of Errors are announced at the STRAND. The Rivals at the VAUDEVILLE continues to draw, though the revived old comedy has been played consecutively one hundred and seven times. Olivette closes its career at the AVENUE THEATRE this week. At the BRITANNIA The Shaughraun has been repeated, followed by Scarlet Dick. SADLER’S WELLS has been furnished with a new drama called The Weaver’s Daughter. The PAVILION has remained in possession of the Royal English opera company. At the MARYLEBONE has been produced the emotional drama of Faith, Hope, and Charity, followed by The Two Prisoners of Lyons. THE ADELPHI. Squire Orchardson ... ... ... Mr E. F. EDGAR Mr Robert Buchanan has had to suffer not a few dramatic defeats. We think the time has now come when he may be complimented and congratulated on a genuine triumph. He has furnished the stage with a powerful drama, christened as above, and he has given novel readers a powerful story called “God and the Man,” the latter being avowedly based upon the former. Those who read the one and see the other will doubtless be disposed to admit that the merits of the story are considerably in advance of those of the play, but at the same time will be compelled to acknowledge that dramatic literature has a decided gain in the contribution of so thoroughly interesting and so vigorously written a piece as Storm-Beaten undoubtedly is. The play begins with such vigorous and exciting work that a suspicion at once enters the mind of the habitual theatre-goer that it cannot be kept up; but astonishment, not unmixed with delight, follows when it is discovered that in at least two succeeding divisions of the piece there is no falling off, but rather a heightening of the fever of interest which has set in with the rising of the curtain. It may be objected that when the story is half told the author calls in the assistance of the stage carpenter, and begins to depend on realism and sensational “effects,” but The drama’s laws the drama’s patrons give, and the author who failed to supply something sensational would also fail to please Adelphi patrons. It may be objected with more force and with more reason that Mr Buchanan despises the laws of dramatic justice, and makes the villainous at the end equally happy with the virtuous; but we shall repeat that the merits of the play are far in excess of the defects, and shall not hesitate to assert that, if Storm-Beaten fail to secure a large share of public patronage, it will be the author’s misfortune rather than his fault. The scene of the prologue is the Fen Farm, the home of Dame Christianson, her son Christian, and her daughter Kate. There is trouble in the house, for the dwellers therein are deeply indebted to Squire Orchardson, who threatens to seize their goods and lands, and from him they expect no mercy, for there has long been a feud between the families—a feud so bitter that the dame’s son affirms it can only be wiped out with blood. The daughter is secretly in love with the Squire’s son Richard, hoping that their love and their future union may end the feud. But it is not to be. The Squire comes to demand his money; in the meantime the two young men meet; Richard Orchardson shoots Christian Christianson’s handsome dog, and fierce and furious they struggle through the door of the farmhouse. Bitter are the words and angry that pass. The Squire, in his rage that a hand should have been raised against his son by one who is dependent on his leniency, turns upon the farm people, threatens to grind them down until they have to beg not only for mercy but for bread. The scene gives so great a shock to the dame that her life is despaired of, but, taking the holy book, she causes her son to swear to have no intercourse with the Squire or his family—her daughter out of her great love for Richard shrinking from the task. Minor incidents in the prologue, which was productive of great enthusiasm, are the interview between Christian and Priscilla, the daughter of a wandering preacher, hunted down by a bigoted and ignorant mob, and that preacher’s rescue at his hands. The drama proper opens with a May-day festival. Kate Christianson has been chosen May queen; but she is nevertheless wretched, as we learn, when she encounters her lover, who has excited her suspicions as to his fidelity, for she has marked his attentions to Priscilla, the wandering preacher’s daughter. Kate’s relations with him have been of a too intimate nature, and she now pleads to him to save her from the shame that threatens. He meets her entreaties with a denial of his promise to marry her, and with the taunt that their social positions are not equal. It is not, however, his intention that they shall be seen together by the villagers, and he drags her from the scene, making way for Christian and Priscilla, the former showing plainly that his heart has been won and that he is over head and ears in love. His ardour is somewhat damped when he learns that her father and the Squire are old friends. The merrymakers now assemble again to wish the May queen a long reign and a true lover; but she has tears in her eyes, and is compelled to explain that there are tears of joy as well as sorrow. There she sits, sad and heavy at heart, under her bower of roses and garlands, while her companions, little dreaming of her trouble, sing blithely and dance gaily around her. “Is she not a sister to be proud of?” says Christian to Priscilla when the dancers are gone; but Richard Orchardson interrupts, and the brother, noting the agitation of the sister, demands of her explanation that she cannot give, and with eager and suspicious eyes he watches her go away with a heart nigh to breaking. Priscilla now resents the attentions of Richard, and defends the good name of Christian. His hatred is hereby made the more bitter, and Priscilla begins to question with herself whether it can be true that Christian loves her. To her comes Kate, stripped of her gay garments, to confess her shame, to seek sympathy, and to avow her intention to fly the neighbourhood. The name of her betrayer she will not divulge, for “Christian will kill him” is her cry. Again comes the brother to urge his love, and overwhelmed is he when he learns what has happened. Gently Priscilla breaks the news; but the whole truth must out. “The man,” he cried, “tell me the name of the man!” “Alas! I know it not,” is Priscilla’s answer; and then, even while the voices of the villagers ring merrily out again, Richard Orchardson stands before him, and, as the curtain falls, his uplifted arm and horror-stricken face reveal the thought that in this Richard Orchardson he may, perhaps, find his sister’s betrayer. Up to this point the play has proved very powerful; the interest of the audience has gradually increased, and everybody is hopeful and confident of a signal success. The second act opens on the exterior of the Squire’s house, where there is going on some amusing rivalry between Jabez Greene, a shepherd, and Johnnie Downs, a sailor, for the love of Sally Marvel, a dairymaid. The Squire has discovered that Priscilla, who, with her father, is about to travel, will, on that father’s death, be a great heiress, and he urges his son to overcome all obstacles to secure her hand. Christian has been following his sister, has learnt that she has become a mother, but has not been able to discover her and to assure her of his pardon and protection from further harm. Again he urges his love to Priscilla, whose answer is “It is impossible.” She fears the extremity to which his hate may lead him, but she comforts him with the assurance that, when far away, she will think of him and will hope for the day when they may meet again. Richard Orchardson, who is to accompany the travellers, thinking how much better will be his chances of success when Priscilla is away from the influence of Christian, is confronted by Kate. Her child is dead, but once more she pleads to him, and is repulsed. She sees his scheme: she would stay his progress, and he throws her swooning to the ground, where she is found by her brother, who, from her lips gets confirmation, strong as holy writ, of his suspicions. And then Christian Christianson utters a fearful curse, and calls on God to keep his enemy’s life for his vengeance. The third act takes us on board the “Miles Standish.” Richard has taken passage with Priscilla and her father, and Christian, too, is on board, disguised, and serving as a common sailor. He listens to Richard slandering his mother and sister; he throws off his disguise and seizes his enemy by the throat. He vows before captain and crew to kill him, and is put in irons. Priscilla, left alone with him, asks him to abandon his scheme of vengeance. Upon her he heaps reproaches, and then for the first time she confesses her love for him, and brings him to his knees. He is, however, presently placed below, and Richard, scorned, comes to the conclusion that there is no hope for him while Christian lives. He, too, goes below to seek his manacled rival, and presumably to kill him. We find, however, that he has fired the ship. He is denounced by Christian, who is rescued, and the flames are extinguished. The vessel escapes the fire, only, however, to be wrecked by icebergs, and in a few moments we see her frozen in and crew and passengers making themselves as comfortable as possible in their icy home. But suddenly the ice begins to move; the ship is free from its bondage; Priscilla is carried on board; the vessel sails away; Richard Orchardson and Christian Christianson are left face to face; there is a fight for life; Richard is thrust beneath the billows; and as the act-drop comes down we see his rival and his enemy clinging for dear life to a floe of ice. Over this very stirring and realistic scene the audience became wonderfully enthusiastic, and Mr Beverley, the artist, had a tremendous call to the footlights. Act four is labelled by the author “Christmastide. Alone with God.” Christian and Richard are together on a rocky island. The former has saved some ship’s stores. The latter is starving. “Remember my sister” is Christian’s only answer to Richard’s prayer for food. His desire for vengeance has not abated. He will watch his enemy waste, and waste, and waste until the hour of his death shall come. The scene for a time is shut off from view, and we next see the wretched foes sleeping, the dreams of Christian being illustrated by a tableau showing the old home, and Priscilla and Kate standing lovingly side by side. Richard Orchardson dying pleads fervently that there may be peace between them, and then falls back apparently lifeless. Christian’s tone now changes. He realises his awful loneliness; he repents him of his oath. The voice of Richard sends joy to his heart; so, too, does the sound of a gun and the sight of a boat well manned and giving promise of rescue. The long, long feud is ended, and all that remains is for Christian to hurry home to take Prisceilla to his arms, and for Richard Orchardson, repentant, to accompany him, and to do all in his power to compensate poor Kate, the victim of his wickedness, for the wrong he has done her. The acting throughout was almost beyond reproach; and while fully admitting the merits of the play, we think Mr Buchanan greatly indebted to the artists entrusted with the interpretation for a large share of the success achieved. Mr Charles Warner, putting his heart into his work, gave us a very powerful portraiture of Christian Christianson. He had to begin at fever heat, and to keep this up almost throughout the entire play must have severely taxed his physical resources. He was, however, equal to all the demands made upon him, and he had the house with him from beginning to end. His grandest effort came with the scene where Christian for the first time learns that Richard Orchardson is his sister’s betrayer. The delivery of the curse and of the prayer for vengeance made a great impression on the house, which was awed into silence, to be followed at the end by a storm of applause. In pleasant contrast with the more impassioned scenes was the gentle wooing of Priscilla; and, taking it as a whole, we are disposed to say that Mr Warner has given us nothing better than his impersonation of Mr Buchanan’s hero. Mr J. H. Barnes had in Richard Orchardson a very uphill task, but he faced it boldly; never flinched from it, and his success was made manifest in the execrations of the more demonstrative among the audience. We do not wish it to be supposed that we see too much of Mr Barnes, but we are sure that the play would be improved if the author could alter his scheme a little, and do dramatic justice by getting rid of Richard Orchardson in the fourth act. Mr Edgar was duly hard, stern, and unrelenting up to the last act as the Squire, and Mr Beerbohm Tree and Mr H. Proctor, dividing the comedy element between them, the one as a semi-daft shepherd, and the other as a sailor of the conventional type, thoroughly succeeded in relieving the more sombre interest of the play. Mrs Billington, who was warmly welcomed on her return to the scene of former triumphs, was very impressive as the dame of the prologue, with which her responsibilities ended. Miss Amy Roselle bringing her generally recognised emotional power to bear upon the part of Kate Christianson, reached all hearts, and wrung from them the warmest sympathy. Who, indeed, could withhold sympathy from poor Kate, decked with May-day garlands, yet sick and sad at heart and bowed down with the thought of the shame that threatens her? Very charming, because very natural and delightful in its gentleness and simplicity, was the Priscilla of Miss E. Lawrence. The good opinion we expressed recently concerning this young lady on the occasion of her début was fully confirmed by this embodiment, and with Miss Roselle she shared some very handsome floral compliments. Miss Clara Jecks must not go without a word of praise for her bright and amusing portrait of Sally Marvel. Mr Beverley’s scenery is magnificent, and shows that the hand of the master has not lost its cunning. Mr Henry Sprake’s music, Mr Dewinne’s pastoral ballet, and the dresses designed by Mr E. W. Godwin all won commendation, and all assisted in the success of which Mr Buchanan was assured by a call to the footlights at the end, and an enthusiastic shout of congratulation. ___

The Illustrated Sporting and Dramatic News (17 March, 1883 - p.7)

ADELPHI THEATRE. THE Messrs. Gatti have signalised their resumption of the reins of management at the Adelphi by the production, on a very elaborate scale, of an original drama by Mr. Robert Buchanan, called Storm Beaten. This play is an adaptation of “God and the Man,” a fine novel by the same author, which may be said to have for its text the words, “Vengeance is mine, saith the Lord.” They keynote of the story, which though didactic is by no means undramatic, is struck in the lines printed at the commencement of the first volume, and indicative of its hero’s heathen frame of mind throughout the early part of the tale:— All men, each one, beneath the sun, If God stood there revealed full bare, And the prayer would be, “Yield up to me The scheme of the story, which is of the simplest, so far as its plot is concerned, is designed to furnish the hero, Christian Christianson, a motive for his all-consuming and almost righteous hate towards Richard Orchardson. To this end the two men are made the representatives of two neighbouring families, which have been at feud for generations. By the foreclosure of a mortgage the Orchardsons become possessed of nearly all the fruitful land belonging to the Christiansons; and Christianson the elder dies just before the crash comes. The smouldering hatred of young Christian is fanned in various ways during his early days, until as a lad he finds himself the rugged rival of the polished Richard Orchardson for the hand of a wandering preacher’s daughter named Priscilla Sefton. But the spark which finally sets light to his fury is the discovery that his sister Kate has been betrayed by Richard. Frantic with the shame which actually kills his mother, the young man vows the death of his hereditary foe; and not all the gentle influence of Priscilla can turn him from his purpose. Warned by his father, Richard Orchardson leaves the country for awhile, accompanying Priscilla and her father to America, whither they are bound on a semi-religious errand—for the period is that of the great Dissenting revival under John Wesley. On the same vessel Christianson ships as a common seaman before the mast, and then commence the most original and daring scenes alike of “God and the Man” and of Storm Beaten. Enraged at hearing the lies poured into Priscilla’s ear by Richard, he madly assaults his old enemy, and is promptly put in irons by the captain. While in confinement below he is visited by the pitying Priscilla, tells her his wrongs once more, and wins her love. Then in the least probable passage of the story Richard is driven by insane jealousy to fire the ship, and when all escape in boats is denounced by Christian for his crime. But the climax of the adventures is reached when this second ship is for awhile locked in the ice, and when the two men, accidentally left behind, find themselves face to face alone on the floe. How when his opportunity comes to him Christianson delays accepting it; how he feels himself driven against his will to feed his starving foe; how he risks his own life in defending his enemy’s, and how finally he forgives him—all this will readily be remembered by all who recollect the last volume of Mr. Buchanan’s nobly-conceived romance. ___

Bell’s Life in London (17 March, 1883 - p.5) “Storm Beaten,” by Mr Robert Buchanan, produced at the Adelphi on Wednesday, supplies an important chapter in the history of modern drama. Being the work of the author of London Poems, The Book of Orm, St Abe and his Seven Wives, Phil Blood’s Leap, etc, I need scarcely say that it is all round the best written piece we have seen on the stage for many years. It is founded on the author’s noble romance, God and the Man. Hitherto, owing to a variety of causes, Mr Buchanan’s success as a writer for the stage has not equalled his good fortune as a poet and novelist. He very nearly achieved a triumph at the Lyceum a few years ago by means of a strong piece (the title of which escapes my memory), founded on a page in the history of the French Revolution; but it has remained for “Storm Beaten” to place him on a level with the most skilful of our dramatists. I mean dramatists pure and simple. The form and construction of “Storm Beaten” leave little or nothing to be desired. Fortunate as the piece is in its exhibition of quaintly-conceived and delicately-touched studies of character, it could scarcely have escaped a certain kind of success if these had been put in after the manner which finds favour with admirers of the small but prolific Boucicaults of the East End. It is chiefly because a poet of the greater passions has spoken with force and pathos, and with a subtle feeling for dramatic contrasts, that the thrilling story of “Storm Beaten” has such a grip of the spectators. No mere mechanical dramatist has been at work. __________ We are introduced in the prologue to the home of Dame Christianson (Mrs Billington), the Fen Farm, and learn from her and her son Christian (Mr Charles Warner), and in a reflected way from her daughter Kate (Miss Amy Roselle) that, owing to the scoundrelly conduct of their landlord, Squire Orchardson (Mr E. F. Edgar), which hurried the Dame’s late husband to his grave, they are to-day in danger of being turned out of doors. There is a bitter feud between the two families, which the widow keeps alive. neither she nor Christian, however, knows that Richard Orchardson (Mr J. H. Barnes), who is “a shocking bad lot,” and Kate love each other. There also figure in the prologue, besides the characters I have mentioned, Mr Sefton (Mr J. G. Shore), a wandering preacher, who is afflicted with blindness, and Priscilla (Miss Eweretta Lawrence), his daughter. By means at once strong and skilful the lines of the plot are laid down in this exciting prologue, which closes with the son’s swearing on the Bible, at the bidding of his mother, to hold no communion with the Orchardsons, but to hate them with the hate of hate to the end of his days. The daughter, driven to the ordeal by the iron will of her mother, faints at the last moment, and swoons. We were prepared in the prologue for the infidelity that Richard exhibited in the first act. He would be off with the old love and on with the new. Kate appeals to him, and implores him to marry her. There is a reason why. He spurns her, and she, aghast at the thoughts of her disgrace, goes “out into the night.” In the second act Christian learns the worst. He also ascertains that his enemy and rival has taken ship with the girl whom he loves. Her father has a mission in a distant land, and her place is by his side. The seducer of Christian’s sister means to marry Priscilla, having discovered that she is a fortune. Christian joins the ship disguised as a sailor. He has sworn he will follow him to the end of the earth and kill him. They meet on the deck of The Miles Standish, and, hearing Richard asperse his sister to Priscilla, Christian throws off his disguise and seizes the scoundrel by the throat. The pair are separated and the assailant put in irons and confined in the hold. Priscilla pleads with the captain for an interview with the prisoner, which is granted. He goes to his confinement happy in the knowledge that Priscilla loves him. Richard, who has witnessed part of the interview, thereupon resolves to make an end of his rival. He sets the hold on fire. The man in irons is rescued, and the ship runs into an ice floe. In the fourth act wronger and wronged are alone upon an island in the arctic regions, at Christmas-tide, “alone with God.” At the last, when vengeance is his, and his enemy is at the last gasp, he relents, and prays to be forgiven. The twain are rescued, and, in the final act, restored to home, penitent and chastened, and resolved to hate no more. The feud is healed. __________ Mr Charles Warner’s impersonation ranks with the best of his performances in this exacting line of histrionic art. He is afforded a number of great opportunities of displaying the intensity of his method, and of these he avails himself without once striking a false note. One’s sympathies are with him throughout—one never loses touch, let the revelation be what it may. Ergo, for all its torrents of passion the character of Christian Christianson is near and natural. For such a tremendous scoundrel as Richard Orchardson is, through four acts, to awake one’s pity in the fifth, was to betray power of no common order. Mr Barnes accomplished this. Miss Roselle’s Kate was a genuinely pathetic performance, and Miss Lawrence more than fulfilled the promise she had shown at a recent matinée by her fresh and charming impersonation of Priscilla. Although Mrs Billington has but one scene she makes an impression therein which remains. There is nothing finer in the drama than the last few minutes of the prologue. Jabez Green, “a natural” (Mr Beerbohm Tree); Jacob Marvel (Mr A. Redwood), a cobbler; Johnnie Downs (Mr Harry Proctor), a sailor; Sally Marvel (Miss Clara Jecks), and Captain E. S. Higginbotham (Mr E. R. Fitz Davis) of the brig “Miles Standish,” complete the cast of this wonderfully fine drama. They are characters every one, and are admirably-filled, especially by Mr Tree. The “natural” he represents might have walked out of one of Thomas Hardy’s novels. I am warned that I must keep my remarks about the scenery for another occasion. For the present I content myself with saying that it is entirely worthy of Mr Beverley’s magic pencil and supreme knowledge of stage-effect. ___

The London Magpie (17 March, 1883 - p.11) FOOTLIGHT CHATTER. The principal dramatic event of the week has been the production at the Adelphi of Mr. Robert Buchanan’s new drama, Storm Beaten. We have already given a précis of the plot, and the incidents include a fire at sea, and a fight on the ice. The leading parts were played by Mr. Charles Warner as the hero, Christian Christianson, Mr. J. H. Barnes as the villain, Mr. Beerbohm Tree as the blind clergyman, Mrs. Billington as the mother, Miss Eweretta Lawrence as the hero’s betrayed sister, and Miss Roselle as the meek heroine Priscilla. The Lord Chamberlain objected to the title of the novel God and the Man, hence the new cognomen. ___

Reynolds’s Newspaper (18 March, 1883) PUBLIC AMUSEMENTS. ADELPHI THEATRE. Although Mr. R. Buchanan, in his play of “Storm Beaten,” produced on Thursday evening, still proves himself immeasurably superior as a novelist than as a playwright, he may nevertheless at last be congratulated on having achieved a dramatic success. This piece, which is written in a prologue and five acts, is founded upon the very clever romance of “God and the Man,” a title which we believe would have been given to the drama but for objections raised by the licenser of plays. If this is so, the author takes his revenge by scattering the name of the Deity—in no profane sense, however, be it recorded—pretty profusely through the dialogue. The plot, which is full of moving incidents by land and water, turns upon a feud existing between the families of the Orchardsons and Christiansons. Squire Orchardson holds a mortgage upon Dame Christianson’s farm. If she will ask him humbly, he is not averse to granting time for payment of the overdue money. Any such friendly arrangement is, however, put a stop to by Orchardson, junior, shooting the dog of Christian, the Widow Christianson’s son. As the animal, who is a splendid canine specimen, appears upon the stage, Christian at once grips the sympathy, and young Richard Orchardson wins the animosity, of the audience. The dame, who suffers from heart disease, dies suddenly, her end hastened, it would appear, by her daughter Kate’s refusal to swear upon the Bible an oath of hatred against the Orchardsons—an oath which her son has not hesitated to take. The fact is, Kate loves young Richard Orchardson. She is seduced by him, and the discovery of this fact by her brother, and the knowledge that he has a rival in Richard for the hand of Priscilla Sefton, the daughter of a blind and wealthy itinerant preacher, yet further heightens his hatred. Old Sefton is ordered a sea voyage for his health; Priscilla accompanies him; Richard secures a place in order to obtain Priscilla’s hand; and Christian, from motives of revenge, also embarks on board the brig Miles Standish. Christian threatens Richard’s life, and gets put into chains; Richard fires the hold in which he is confined, and the ship narrowly escapes being burnt. The vessel then gets caught in the ice, and by the action of Christian, when she is released by its breaking up, he and his enemy are left alone upon the ice floe. Christian manages to get possession of food and firing, which he cannot bring himself to deny sharing with his enemy; but when a boat comes to their rescue, Richard is apparently dead from the fearful sufferings he has undergone, and Christian reproaches himself with being the cause of his death. In the last act both have returned home, little the worse in body, and very much the better in mind, for their perilous outing. Priscilla has got home before them, and when the curtain falls on the villagers assembled in an adjoining church, and singing the Easter hymn, it is evident that Christian will wed Priscilla, and Richard make an honest woman of Kate. The prologue and first three acts of the play are—if we except a curse which terminates the second act, and is so terrible that the listener’s mind involuntarily reverts to that pronounced upon the Jackdaw of Rheims—simply admirable. The fourth act wants considerable cutting down. Mr. Warner, as Christian, and Mr. Barnes as Orchardson, have the stage all to themselves, and the little acting the latter has to do, and the great deal of talking the former does, scarcely compensates for the long drawn-out misery it portrays. On the other hand, the scene, with its snow-covered ice-peaks and caverns, with its prismatic rayed aurora borealis, is superb. The last act is pretty, weak, and evidently written with a view to making things end happily all round, a very different termination to the dramatic one of the novel. From first to last the scenery is deserving of the greatest praise, and shows Mr. Beverley to be an artist as well as a clever scene painter. The stage management is not so satisfactory, exhibiting mistakes apparent to the merest novice in matters theatrical; these, however, will doubtless be rectified. Mr. E. F. Edgar played carefully as the elder Orchardson; Mr. J. H. Barnes was the vicious Richard, a part in which he commendably restrained himself from over-acting—praise which cannot be extended to his fellow actor, Mr. Charles Warner, who, as Christian Christianson, tore his various rages to tatters with an energy that was more loud than artistic, and who mistook preaching for pathos. Very powerful, and withal natural, was the Kate Christianson of Miss Amy Roselle; and, on the whole, satisfactory, if somewhat weak, the Priscilla of Miss Eweretta Lawrence. The small part of Sally Marvel, a dairymaid, was allotted to Miss Clara Jecks, whose delightfully bright and girlish acting served to relieve the more sombre portions of the play. Mr. A. Redwood, also in a small part, that of Sally’s tyrannical father, was of great service to the piece; and Mrs. Billington, who appears only in the prologue, acted with great power as Dame Christianson. Messrs. J. G. Shore, Beerbohm-Tree, Harry Proctor, and E. R. Fitzdavis are also in the cast. Very cordial acclamations awaited the author at the fall of the curtain; but he must have exclaimed “Save me from my friends!” when he heard himself called for so early in the play as the end of the prologue. ___

The Referee (18 March, 1883 - p.3) “Storm-Beaten,” by Robert Buchanan, was produced at the Adelphi on Wednesday. It is in a prologue and five acts. Don’t shudder—all of them are pretty short, and there is plenty of action to keep awake your interest. There is, too, a good deal that is vastly improbable to make you wonder, and a few things that are very ridiculous to make you laugh. “Storm-Beaten,” which has been given to the public in novel form under the title of “God and the Man,” is, I should say, the very best thing the author has done in the dramatic way. I shall not be far wrong if I hazard the opinion that in the putting together of the Adelphi piece he has had valuable assistance at the hands of Mr. Charles Warner. I should be very much in error, though, if, at the same time, I predicted that Buchanan will give Warner half the profits. The “situations” and the business are exactly of the kind that an actor would desire and suggest, and that a novelist turned playwright—that is, one like R. B., judging from former essays—would not. There is some very vigorous writing in the new play; there is much high-flown talk; there is a curse that has, I fancy, done duty before in one of Buchanan’s pieces; and there are many appeals to the Deity—too many. The author got along very well throughout the prologue and two acts. Then he called in the stage carpenter, the scene-painter, the property-maker, and the machinist to contrive something sensational and realistic, and he stuck to them nearly to the end. Prologue.—Scene, a Farm House. Mrs. Billington, Charles Warner, her son, and Amy Roselle, her daughter, live here. Squire Edgar wants to turn them out, and to get possession. Awful feud between the two houses, but Barnes accepted lover of Amy. Warner in possession of beautiful canine pet. Now arises the important question mooted years ago in the Volunteer ranks, “Who shot the dog?” The answer is “Barnes!” who is taken by the throat by the dog’s master. Squire, furious over this, curses and swears in the doorway, and threatens all sorts of horrible things. Mrs. Billington upset. Going to die. Calls for family Bible; makes Warner take oath to hold no communion of a friendly nature with the other fellows. Any Roselle asked to swear too. Swearing is unladylike, and Amy declines. Act I.—May Day. Amy Roselle crowned Queen of May. Would have sung, “Call me early, mother, dear,” but mother is dead. Any very wretched. Has been seduced by “Handsome Jack,” who is tired of her, and is paying court to pretty Eweretta Lawrence, daughter of J. G. Shore, a blind travelling preacher of the Gospel. Warner in love with this young and lovely party. More cause for hatred. Amy confesses her shame to Eweretta, and runs away from home. Eweretta tells Warner, and Warner roars furiously, “Show me the man!” looking very angrily and very suspiciously at Barnes, who at that moment comes along. Act II.—Warner been searching for Amy, who has had a baby and lost it. Eweretta some day going to be rich—all the more reason why Barnes should stick up to her. Will accompany her on voyage, in search presumably of North Pole. Just going off on expedition when Amy comes back to ask him to make her “an honest woman.” Spurned by the wicked one, Amy faints. Is found by Warner. lets out name of betrayer. Warner curses and swears to kill him, calling on God to assist him in his murderous intention. Act III.—On board ship. Warner in guise of man before the mast. Barnes making love to Eweretta. Warner discovers himself. Row follows. Warner put in fetters, and stowed away in hold. Captain and crew go to bed, and leave ship to take care of itself. Barnes reflects, can’t have Eweretta while Warner lives. Goes down hold, and fires the vessel. That’s quite more Hibernico, you see. Fancy a fellow setting fire to a ship on which he is a passenger, in order to save his life! Warner saved; fire put out. Ship among the icebergs. rattle, row, clatter, crash. Captain, crew, and passengers on ice. A general thaw. A rush for the ship. All on board when she sails away except Warner and Barnes. Fearful struggle. Barnes shoved under water. Warner floats away on an icicle or a seal’s back. Can’t say which. Act IV.—Warner and Barnes on rocky island. Got it all to themselves. Warner well off for food, and clean. Has washed himself ashore. Barnes starving and dirty. Hasn’t washed himself for days. Awfully cold among the ice, but both bare their throats and breasts to the Arctic blast, and rather seem to like it. Beards grown in five minutes by new process. “Give me something to eat!” cries Barnes. “Sha’n’t!” answers greedy Warner. “Kill me, then,” pleads Jack. “I won’t,” replies Charles. “You shall starve. You caused my sister to go wrong. You tried to run away with my girl. You’re a regular waster, and now I’ll see you waste and waste, and die!” There’s a nice respectable hero for you. What do you think of him? Barnes doesn’t die, but he does nearly. He reminded me, though, of Charles II.—he was such an unconscionable long time over the operation. When Warner thinks his enemy has given up the ghost he wishes he hadn’t, for he begins to feel lonely. He is a murderer, you see, in intention if not in deed. Presently Barnes wakes up. Then is Warner glad. He forgives his foe, and the feud is ended. What’s that? A gun, by Jove! It is Christmas Day, and some fine young fellows have come out to the North Pole for a little hunting. “We are saved! We are saved!” Tableau and general joy. Act V.—Home again. Warner to marry Eweretta, who has somehow got back. Barnes to marry Amy, and to make her “an honest woman.” Warner went about his work with mighty vigour, and cursed and swore, and made appeals to heaven, and threatened in a way that put him out of breath. He seemed quite excited over his share of the piece, and I must compliment him on his enthusiasm. On the icy island it was quite refreshing to note the effect of old associations. He was but thinly clad, and must have been awfully cold. He nevertheless pulled off his coat and rolled up his sleeves and went for his enemy quite secundum artem, as though engaged in a street row in the dog days over here. Barnes, as the handsome seducer, was also very vigorous, and gave so striking a picture of stage villainy that the virtuous gods howled at him. For that fourth act, though, he might persuade the Messrs. Gatti to provide him with a piece of soap and allow them to deduct the expense from his salary. Warner and Barnes have simultaneously to do a little cuddling in the last act, and they do it very nicely. If you don’t believe me, ask Amy and Eweretta. These young ladies won general favour, Amy showing some fine pathetic power as the May Queen who has gone wrong, and Eweretta quietly but charmingly getting through her work as the beloved of Warner. Mrs. Billington was, of course, up to the mark as the grand old dame of the prologue, but it is to be hoped she will in time learn to make better use of the family Bible. Clara Jecks was very smart and amusing as a dairymaid who doesn’t care much for her waxy old father, who is a cobbler and wants to give her whacks for wearing ribbons. Beerbohm Tree, as a shepherd, has to appear “in beer” and in love. It is a silly part, and nothing was to be made of it. H. Proctor sings very well “The Man at the Nore,” but singing “The Man at the Nore” only wastes time. Some of the scenery by Beverly is very fine, and I pray you to note the Aurora Borealistic effects in the fourth act. It was in this act occurred the only hitch in the representation. Something went wrong with the vision of Amy and Eweretta presented to Warner, and the curtain had to be lowered for a few seconds. ___

The Pall Mall Gazette (19 March, 1883) THE THEATRE. IN his new drama of “Storm-Beaten,” Mr. Buchanan develops an idea of more novelty and originality than can often be excogitated in days in which combinations of human motive have undergone an analysis as prolonged and almost as exhaustive as has been bestowed upon the openings at chess. Granted the existence of a quarrel between two families, so stern and relentless it resembles that rather a feud such as was once common throughout Italy, and still lingers in Corsica, than any possible product of Northern habits, the problem Mr. Buchanan sets himself is how this may be quenched without such interference of Love as is exhibited in the “Castelvines y Monteses” of Lope de Vega, Shakspeare’s “Romeo and Juliet,” and a score of subsequent dramas. By adding to the passionate hate of a young and fiery representative of one of the factions such sense of private and hideous wrong as is begotten of the shameful surrender of her honour by his sister to his enemy, and by presenting the seducer and the brother of his victim as rivals in love, Mr. Buchanan has supplied a combination of motives as strong as has often goaded men to the commission of deeds of violence. With but one purpose in his heart, that of murder, Christian Christianson follows in the track of Richard Orchardson. Once and again, under sufficiently dramatic circumstances, the men meet and the death struggle commences. As often it is interrupted, and the execution of the resolute purpose of Christian is postponed. At length the slaughter by the stronger of the weaker and the more base is apparently accomplished under such conditions that the avenger, for the purpose of carrying out his scheme, seemingly forfeits his life. The murder is executed on an ice floe in the Northern seas, and while it is being committed, the vessel that has borne both to the scene of conflict sails away and leaves them. Once more the supposed victim escapes, and the two men meet again upon the iron coast of an Arctic island. No need is there now for the pursuer to strike his enemy. Possessor himself of provisions that have been deposited on the island in view of the possible destruction of the ship, he can sit in comparative security and watch the wretched man expire of starvation and cold. This, however, keen as is his hate and murderous as are still his intentions, he cannot do. To a robust and virile nature passive acquiescence in murder is as impossible as to a meaner nature is the substitution of violence for trickery. Contemptuously accordingly, and with flagrant insult some scraps of food and clothing are thrown to the starving man. Influenced partly by that mysterious instinct in our nature which makes us with indolent purpose water the tree we have carelessly planted, and partly by fear of being left alone in the appalling solitude, Christian learns first to tolerate the presence of his enemy, then to accustom himself to it. In the end, with kindliest ministrations he watches him through the throes of a fearful illness, and with fervour equal to that of his previous imprecations prays that the life he has so long sought may now be spared to him. “Storm-Beaten” is a powerful, a stirring, and, in some respects, a good play. It has interest and pathos both genuine, it is animated by a strong current of passion, and it contains some eminently dramatic situations. One or two excisions are strongly to be recommended. That the whole will be a permanent success is scarcely to be doubted. No attention has been spared in mounting and casting the novelty. Dresses and scenery are excellent, and the interpretation is strong. Mr. Warner as Christian carries off the honours of the representation. Looking the character to the life, Mr. Warner acts it with earnestness that at one point, at least, rises into intensity. Mr. Barnes struggles arduously with the repellent character of Orchardson. Miss Eweretta Lawrence acts with prettiness and grace as Priscilla Sefton, the heroine, and Miss Amy Roselle with power as Kate Christianson, the victim of the enemy of her house. Mr. Beerbohm Tree supplies a capital picture of country manners; and Mrs. Billington, Mr. Edgar, Miss Jecks, and other actors support adequately the remaining characters. ___

Birmingham Daily Post (19 March, 1883) Mr. Buchanan should at last be happy, for “Storm Beaten,” produced at the Adelphi this week, has had a far more gratifying reception than previous dramatic efforts from the same pen. As a poet and as a novelist Mr. Buchanan had succeeded in no small degree, and succeeded; but when he had touched the stage his cunning of hand seemed to have deserted him, and the result was failure. “Storm Beaten” has proved a worthy exception, and, although there are defects, notably in the inartistic but traditional “happy ending,” Mr. Buchanan is to be congratulated upon the impression his play has made. The taste for strong and full-flavoured melodrama is evidently reviving, but nowadays, in addition to the sentiment, which was the only essential forty years since, and to the real pumps, which was the added necessity a couple of decades ago, audiences demand a decided admixture of literary form. This, which partly accounts for the success of “Storm Beaten,” is also a potent factor in the popularity of “The Silver King,” at the Princess’s. Mr. Wilson Barrett, in his speech at the close of the hundredth performance of the play, recognised this to the full; and if he can continue to supply the Princess’s with pieces of the same stamp there is little doubt of melodrama continuing to flourish. ___

The Sheffield Daily Telegraph (19 March, 1883 - p.2) Mr. Robert Buchanan has made a fresh bid for success as a dramatist, a line in which he has hitherto proved as signally unlucky as the Poet Laureate himself has done. Hitherto he has not even enjoyed the advantage of having an indifferent poem expounded by an actor of the position of Mr. Henry Irving, or yet of seeing a really bad play vamped to a spasm of notoriety by the hysterical piety of a pugilistic Marquis. It seems, however, that at last the Scotch poet has scored an advantage which has really been denied to the English bard, for his latest production is something like a success. Having regard to the number of Mr. Buchanan’s dramatic failures one is compelled to credit him with some of the perseverance ascribed to the Bruce after contemplating the legendary struggles of the spider. “Storm Beaten” is filling the Adelphi Theatre, and the audience confesses itself satisfied with the story as much as with its exponents. ___