ROBERT WILLIAMS BUCHANAN (1841 - 1901)

|

ROBERT WILLIAMS BUCHANAN (1841 - 1901) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

BOOK REVIEWS - POETRY (1)

Poems & Love Lyrics (1857) Mary, and other Poems (1859)

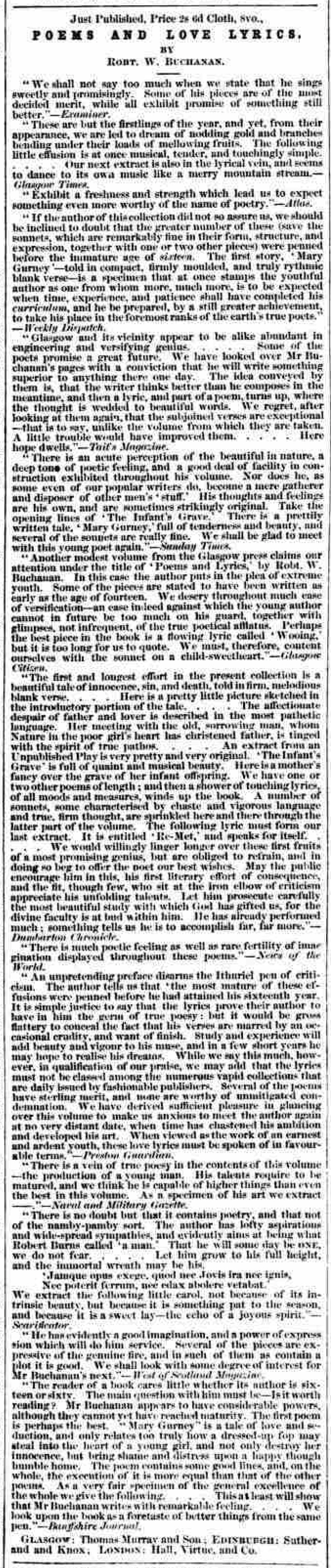

The Spectator (7 November, 1857) Poems and Love Lyrics, By R. W. Buchanan.—The longest poem in this volume is “Mary Gurney,” a tale of village seduction, desertion, and death. The subject is so common as not only to be hacknied but easy. It is, however, attended with a moral dilemma, into which raw verse-writers are apt to fall: the village maiden is far too easily ruined, and not unfrequently with a neglect of morality in her own conduct. The minor poems of the volume are chiefly remarkable for an attempt at force by means of violence. ___

The Glasgow Sentinel (14 November, 1857 - p.1) Reviews. POEMS AND LYRICS. By ROBERT W. BUCHANAN. Glasgow: Thomas Murray and Son. MODERN society, notwithstanding all its searing influences, is pervaded by an ever-active spirit of poetry. That such is the case, is abundantly evident from the complexion of the stream which, as from an inexhaustible fountain, is ever issuing from the press. Another, and another, and another, streameth forth the grand procession of the books. Now it is a stately and sonorous history—now a hard-featured and crabbed-looking treatise on science; again it is a creation of fiction—mirthful or serious—“holding the mirror up to nature;” and anon, it is an utterance of song, haply in all the pomp of the epic, but far more frequently in the less ambitious shape of lays and lyrics swelling forth from souls which love to pipe a simple song to gladden the hearts of their fellow-men. The number of the minstrel tribe in modern days is indeed great. They are of all ranks and degrees of excellence, from Tennyson, upon whose honoured brow is wreathed the laurel of an assured immortality, down to the most lowly and illiterate metre balladmonger who ever counted his fingers in the vain attempt to make his verses clink. Yet ever as the “gude black prent” comes forth, we love to greet the successive aspirants to poetic honours, and to scan their several offerings to fame. In this way we have often met with good grains among the chaff, and beadings of finest gold where we had only looked for gravel or clay. The latest contribution to the literature of the lyre—at least the latest which has come under out notice—is by the author of the little volume the title of which heads the present article. From the preface—a modestly-written prelude to the poetry—we learn that Mr Buchanan is a very young man, and that the greater number of his productions were penned before he had attained his sixteenth year. On this ground he appeals to the kindlier feelings of the critic, and truly reminds him “that the bark of youth is necessarily more abundant in sail than in ballast.” That the generality of the fault-finding brotherhood will make due allowance for the juvenility of the poet we have no doubt, although there may be a testy old buffer here and there who will growl at the appeal. Such a one, we flatter ourselves, we are not. Remembering that Cowley and Pope both lisped in numbers, we have always scanned the pages of the young poet with interest; not in the expectation of meeting with anything like profundity of thought or maturity of style, but, if possible, to discover what of promise lay within his pages. The child has been said to be the father of the man, and in the lineaments of the child there are often indications of the future man. In the poems and lyrics of our youthful author, for instance, we imagine we can discern the luxuriance of a spring which may yet develope itself into an abundant harvest. These are but the firstlings of the year, and yet, from their appearance, we are led to dream of nodding ears of gold and branches bending under their loads of mellowing fruits. HAPPY LOVE. Merry blossom on the hours, Hark! the lay of Love’s soft sea, See! fond smiles envelope heaven, How I listen to thy song, There is lustre up above, Our next extract is also in the lyrical vein, and seems to dance to its own music like a merry mountain stream—like a merry mountain streamlet, also, it dies away in melancholy murmurs— WOOING. O, the wooing, endless wooing, O, the wooing, endless wooing, O, the wooing, endless wooing, O, the wooing, fruitless wooing, O, the wooing, bootless wooing, O, the wooing, bitter wooing, O, the wooing, empty wooing, But we must conclude, and, in doing so, we beg to offer the young bard our best wishes. May his elegantly got up and beautifully printed volume—the first-fruits of his genius—prove a great success, and tempt him at some future and more mature period of his life to scale again the brow of Parnassus, and to glean the flowers and the fruits, the tendrils and the leaves, which he may be privileged to gather on his onward and upward way. ___

The Saturday Review (12 December, 1857) POEMS.* LONDON LYRICS, by Frederick Locker, seem to be the work of a man who has lived in Piccadilly, but kept a country heart—not a disagreeable sort of production, for few things are pleasanter than to see warm and fresh feelings controlled by the sense of a man of the world. The collection looks, and is, one of a very light and slight kind. It is marred by some bad faults of taste. What can be more atrocious than such a play of words as “the widow’s mite”—“the widow’s might,” and who but the writer of a pantomime would be guilty of such a joke as “the trees have cut their ancient sticks?” When humour and sentiment are blended, the humour must keep bounds. However, there are some pretty lines in the book, for example, the following on Old Letters:— Old letters! wipe away the tear, Yes, here are scrawls from Clapham Rise, How strange to commune with the Dead— And here’s the offer that I wrote And here my feud with Major Spike, And here a letter from “the Row,”— And here a heap of notes, at last, A human heart should beat for two, See here a double violet– The two last lines of the last stanza but three, “Though hope though passion may be past,” &c., are the best of it. Wake! wake! my loved muse, thou hast slumbered too long, Once Rusticus rises to something tolerable. It is when he throws down “the minstrel's lyre” for a moment and gives us his genuine thoughts, though only about the points of a departed horse:— Awake! awake, my mournful strain! But we soon slide back again into “He gasped upon the verdant sward,” and “The fate of one I loved so well, chilled every pulse with icy spell”—very withered leaves indeed! Seasons all are full of sorrow, But sometimes it cheers up a little, and is all the better for it:— I love the merry Summer, We think we can imagine—nay, we think we have actually seen—a “gorgeous swell,” but we cannot imagine a “gorgeous swell of flowers.” BENEATH BEN CRUACHAN BY DAWN. Shrill chanticleer salutes the lazy Morn; Fancy Ben Cruachan taking off his misty coat and inexpressibles, to look at himself in Loch Awe! And what is the meaning of “coeval,” in the seventh line? Is Ben Cruachan’s brow Hugging black Night, his drunken paramour, In the poems written before sixteen, are some things which, in point of sentiment, as well as composition, require and may plead the excuse of youth. __________ * London Lyrics. By Frederick Locker. With an illustration by George Cruikshank. London: Chapman and Hall. 1857. ___

Caledonian Mercury (Edinburgh) (25 December, 1857) POEMS AND LOVE LYRICS. By ROBT. W. BUCHANAN. IN the face of an urgent appeal from the author, in the preface, to deal gently with his “many and very obvious demerits,” it would be ungracious to look with other than an indulgent eye on these first-fruits of his fancy. He tells us, moreover, that his present ambitions are humble in the extreme, and that the volume now submitted to us is not to be regarded as a true test of what he is capable of accomplishing. By far the larger portion of the collection, it seems, was composed before he had attained his sixteenth year, and some of the pieces were written when he was barely thirteen. We are expected, therefore, to suspend the usual severity of criticism in our review of these youthful aspirings, and to treat them pretty much as good-humoured people view the performances of juvenile prodigies. Some grumbler may probably ask why thrust productions thus confessedly immature before the public at all? This is a question, however, which we must leave the author himself to settle. With that proneness to imitation of the reigning poet of the day, characteristic of young versifiers, Mr Buchanan, nevertheless, in his “Poems and Love Lyrics,” gives proof of an originality occasionally very startling. We read of white lambkins cooling the air with sound, of love feeding with lilies the propelling wind, and of a maiden’s eyes in love-lorn fondness watering for her lover’s arms. On the other hand, we meet with touches which unmistakeably proclaim Mr Buchanan to be a true poet. How beautiful the following passage from his poem on “Infant Slumber”:— Here, from the tight-frilled cap, a curl escapes In another of his lyric effusions—“Love’s Heaven,” his soul “growing and soaring, and brightening” in the “pure sparkling bliss of holy communion,” is compared to “an April bud opening into its May,” and again to “a poor heath sprig, yet bright in its morning,” for his life’s one bright particular sun has “kissed the dewy-drop” glittering on his stem, and shines “stainless and clear.” We regret that some of the finest pieces in the volume are too long for quotation, and a mere extract would give but an imperfect idea of them. We may, however, refer to “Wooing” and “Waiting,” and to his song “Be Bold! the fields of Summer Green,” as among his better efforts. ___

The Athenæum (26 December, 1857) [Reviewed by Gerald Massey.] Poems and Love-Lyrics. By R. W. Buchanan. (Glasgow, Murray & Son.)—The youthful author of these verses tells us, in the words of Shelley, that while yet a boy he sought for ghosts. This occupation has not been at all good for his mental health. It has led him groping in dark places, which are haunted by Seduction, Insanity, and Suicide,—subjects of which it is to be hoped he knows nothing. We have little doubt but that in some of his ghost huntings he has got a fright, or he would not talk in this wild way:— The wrinkled sea lies foaming at the mouth, Also, it is to be hoped that even Glasgow City does not make a beast of itself in this suicidal way:— The city, like a foul sea-monster, basks, Our author has a fatal fondness for desperate images. He talks of— Huge Winter raving o’er the groaning plains, Surely this is Shakspeare’s “Ethiop bride” seen through a pot-house window! And not only is Smites Earth’s helpless cheek, that pales beneath A batch of pines is painted rather gorily:— The pious pines, whose thousand fingers point We are sorry to find one so young already a follower on the dim path trodden so long by De Quincey, and so fond of opiates. In one piece alone he uses an “opiate green,” an “opiate harp,” and an “opiate hymn,”—the two latter coming in natural sequence to the former. Perhaps it is owing to the opiates that our author speaks of his eyes “clapping glad hands”—the “glutton Past”—“Night’s aqueous reign”—“innocuous morn”—a prayer “scrawled upon his eye,”—all harmless enough, perhaps; but a youth of fourteen, however promising, must be checked in using Tennyson like this:— So high on tiptoe leant I up to God. And Byron in this way:— Oh! Christ, in truth it was a glorious land. He thrusts his hand among the strings of other harps, and makes us shudder at the discords; and dashes wildly into subjects where only the master hands make music, and where the least uncertainty of touch causes a most painful jarring on the ear. In some verses, on an ‘Infant’s Grave,’ towards which we should be drawn delicately by tenderest touch and gentlest music, our author talks of the “shrivelled breast of Death,” “tears—hot gore,” and “Parched as Sahara’s bowels glowed the burning breast of heaven.” He seems wishful of reproducing the old mock pastoral names of the old mock- turtle doves that billed and cooed as Colin, Lubin and Company in the last century. And in the following stanza he has revived a custom more honoured in “the breach than the observance”;— Great Summer paints the conscious skies, The author having placed himself in the above public position may be safely left there. ___

The Westminster and Foreign Quarterly Review (1 January, 1858 - p.294) . . . We must hand over Mr. Buchanan to Mr. Alexander Smith, that he may see his own image in a distorting mirror, to which let this quotation, from “Poems and Love-Lyrics,” 6 bear witness:— “The wrinkled sea lies foaming at the mouth, O Scotia! O Muses! North of Tweed we are surpassed in everything—even in spasmodism! 6 “Poems and Love Lyrics.” By R. W. Buchanan. Glasgow: Murray and Son. London: Hall and Virtue. 1857. ___

The West of Scotland Magazine (January, 1858 - No. XL, p.296) POEMS AND LOVE LYRICS. By Robert W. Buchanan. This little volume of poems is by a young man belonging to this city, and he states in the preface that, with one or two exceptions, the contents were penned before he was sixteen years of age. We think his friends committed an error in allowing him to publish his book at the present time, as it contains too many things which ere long he would of his own free will have obliterated. Among the recent productions of our minor bards generally there is one feature which we have noticed, and which seems to us a very objectionable one. We mean the custom of writing chiefly about women who have “loved not wisely but too well.” This seems to be the staple article of manufacture with our young poets, and we can scarcely light upon any of their books which does not contain some spasmodic pieces of this kind. That a young man under sixteen should make use of such materials so freely seems to us very objectionable and improper. Passing over this, however, and the occasional use of too strong language, we find some very good poetry in Mr. Buchanan’s book, and had he only been judicious enough to wait a few years, we doubt not he would have sifted the good from the bad, and presented us with a very acceptable volume. As it is, the book gives promise of something yet to come which will be highly creditable to the young author. He has evidently a good imagination, and a power of expression which will do him service. Several of the pieces are expressive of the genuine fire, and in such of them as contain a plot, it is good. We shall look with some degree of interest for Mr. Buchanan’s next effort. ___

The Glasgow Sentinel (23 January, 1858 - p.8) |

|

|||||||||

|

The National Magazine (April, 1858) . . . Passing from the grave to the gay, from the ancient to the modern, we are invited to a perusal of London Lyrics, by Frederick Locker, which is adorned with an illustration by George Cruikshank, prettily conceived, of “Cupids building Castles in the Air,” suggested by the theme of the leading poem. Some of the pieces have a moderate modest kind of merit, and a few blossom into a neat pun or two that may stimulate a gentle smile, and no more. ___

The Critic: The London Literary Journal (15 April, 1858 - pp.177-178) POETRY AND THE DRAMA . . . Poems and Love Lyrics. By ROBERT W. BUCHANAN. London: Hall, Virtue, and Co. Mr. Buchanan says, in a preface to his Poems and Love Lyrics, that he aims merely at “the temporary amusement of a few.” This is to insult the character of his muse; this is to demean the exquisite pictures of his fancy. We have been delighted with Mr. Buchanan’s poems. Unobtrusive, soft, and sweet, they make their silent way into the memory of the reader. With simplicity of style the author has mingled metaphorical richness. Here is a fine passage of which the poet laureate would be proud. A mother, out of her deep love, has kept “peculiar in flowers” the grave of a lost babe; and the poet says: That grave is greener in the summer sun, Sometimes, but not often, the poet is metaphorically mean, as when he says: Mary stood by and spilt as from a cup How very great the tears, and very fragile the flowers! The record of such disastrous consequences proves the youth of the poet. To show Mr. Buchanan’s descriptive power we shall quote a passage from “Mary Gurney”—a poem which perhaps more than any other exposes the inequalities of the minstrel. Our extract will show more pictorial beauty than nine-tenths of our youthful poets disclose, and we can only advise Mr. Buchanan to cultivate the talent with which he is gifted: Groping for gems in thy eternal heart, ___

The Daily Tribune (Salt Lake City) (14 July, 1901) The first book of verse sent out by Robert Buchanan was not “Undertones,” but “Poems and Lyrics,” a thin volume published before the author came to London. The book was dedicated to Hugh Macdonald, who forty years ago, was a well-known writer of local sketches in the Glasgow Citizen. In a prefatory note which is humble and apologetic in tone Mr. Buchanan states that the most mature of the poems, with the exception of three sonnets, were penned before he had attained his 16th year. Back to Reviews, Bibliography or Poetry _____

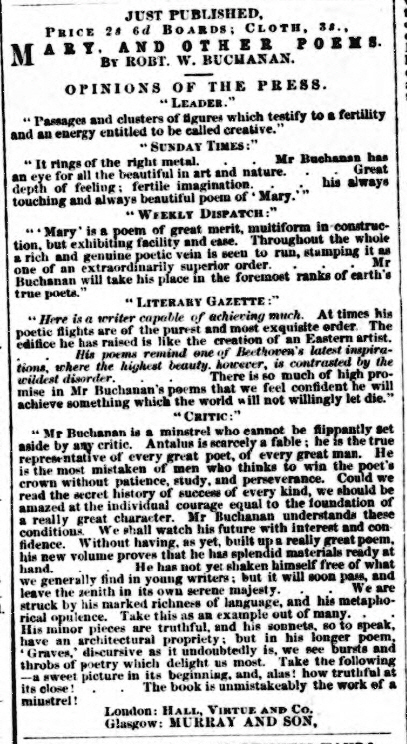

The Glasgow Sentinel (15 January, 1859 - p.1) POETICS. “MARY: AND OTHER POEMS.” BY THE AUTHOR “A SHAPE celestial, tending the dark earth with light and silver service as the moon, is poesy,” exquisitely utters the most tenderly-melodious of all our modern poets, and with such a definition we rest contentedly until philosophy shall have given another as widely-embracing, and inspired by sympathies as touchingly intimated, as in the extract we have had the happiness to quote. With such canon before us, it is with misgivings that we at any time pronounce criticism upon the impalpable art, to create which is the poet’s mission. Deterred by misdoubts of limiting by conventional words the thought intentionally, rather suggested than defined, we ever feel the impossibility of attempting such critical analysis of the poetic form of language as may freely be indulged in with the less ideal language of prose. This difficulty becomes daily more palpable, since every addition to our poetical literature confirms its tendency towards this suggestive character, which is the eminent trait of all art in its highest interpretation. A volume of poems now before us, by the author of “Love Lyrics,” betrays ample evidences of the universality of that hopeful tendency to which we have referred, and which marks the most estimable works of the modern poetical school. This is especially a volume of thoughts, undisturbed by any false endeavour to make these rather subservient to the completion of a narrative than to the expression of all their individual meaning may intrinsically suggest. In freeing himself from the practices and traditions of those preceding schools which aimed at a treatment wholly subversive of the practice of our author, he has shown a worthy sympathy with the highest aspirations of his art, and strengthened in no inconsiderable degree the ambitious claims of the school he is a representative of. In our present notice of this volume we have chosen only to review the poem entitled “The Graves,” leaving its further contents for a future occasion. Through a bold flight of that blank verse which has shipwrecked many a hope, we are borne with the poet into nature’s “Holiest sensibilities, as he has well expressed it, to the scene in which is laid the chief episode of this tale. In this progress we, however, pass many happy thoughts interwoven with the verse by such a simple contiguity as sacrifices nothing of their expression to the story, besides a preconceived unity with its general character. These thoughts, often striking in character, have found, in many instances, a most touching utterance, although spoken of by the poet as “Little rhymes, With such confession of his success, we have of course the less reason to expect such fortunate passages as continually recur in the perusal of the poem we quote from, but we none the less pleasantly fall upon these, feeling, as we do, that in writing them the poet must have felt “Nature smiled Even while, as he says, “I sigh among my melancholy days, We extract from the first page of this volume the following very forcible intimation of that eternal creative fiat which has borne our earth out of the past, and follows it into the future— “The Earth Like another Alastor, a hero of this tale is pictured:— “Within the centre of an ancient wood, Here was his favourite resort—meet bower This gentle poet— “Who grew grey betimes,” and of whom his sympathising brother sings he had “High, sinless thoughts of peace and human weal, And Nature was his solitary bride”— at length is stricken with the tender passion, or as it is picturesquely worded, “Love, the wandering Arab, had pitched his tent and so are the lovers carried away— “Like summer flies upon a silver brook, From some verses following their confession of a mutual passion we quote the subjoined for its rythmical beauty:— “Ah! love that lies in gentle eyes, As a fine instance of that descriptive form of the poetic art which, through its suggestiveness, excites our interest in the poet’s creation, we give the description of Kate Hathorne, as introduced into the narrative of which she is the heroine:— “Her form was fairy-like as atomies With such extracts we must now rest, contenting ourselves with so far having overtaken an agreeable task, while at the same time believing the notice we have given is sufficient to increase an interest in this recently published volume of verse. Having promise of becoming an acceptable addition to our modern poetical literature, it is wit the more regret that we have hastily perused even that portion of this volume we have particularly chosen to refer to. J. D. B. ___

The Spectator (5 February, 1859) The Mary and other Poems of Mr. Buchanan, does not support the promise of that future excellence which friendly critics anticipated from his “Lyrics.” In a preface where humble-mindedness does not predominate, the author refers his readers, not to “Mary,” or a longer poem called “The Graves,” but to his sonnets and minor pieces. These no doubt are better for the reader, inasmuch as they are shorter; but we question whether, length for length, they exhibit more poetry or more finished workmanship. Mr. Buchanan’s mind is not devoid of vigour and power, but he scarcely exhibits that something which we feel to be poetry, though we cannot define it; and he is prone to let himself run to seed. As a first production there would have been promise in his book. As a second designed to fulfil the expectations of a hopeful first, it is rather a failure. ___

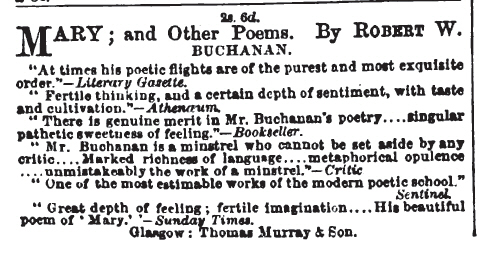

The Literary Gazette (12 February, 1859 - p.217) We scarcely know how to strike a balance between the merits and demerits of Mr. Buchanan’s volume, Mary, and other Poems, by the author of “Lyrics” (Hall, Virtue, and Co.). We have read it with mingled feelings of annoyance and regret. Here is a writer capable of achieving much, who wilfully falls short of the high standard he might attain, in order to indulge a vagrant fancy for extravagant images, far-fetched conceits, and burlesque monstrosities of expression. At times his poetical flights are of the purest and most exquisite order; but he immediately checks the reader’s pleasure by out-heroding the worst extravagances of the Spasmodic school. The edifice he has raised is like the creation of an eastern artist: the magnificent, the fanciful, and the grotesque are thrown together in curious juxtaposition. His poems remind one of Beethoven’s latest inspirations, where the highest beauty is strangely contrasted by the wildest disorder. They are spoilt by a multiplicity of ornament; crushed, like Tarpeia, beneath their weight of gems and gold. There is so much of high promise in Mr. Buchanan’s poetry, however, that we feel confident his maturer taste and riper judgment will discard the metaphorical absurdities in which he now indulges, and that he will achieve something which the world will not willingly let die. As a specimen both of his faults and his excellences we quote the following: I. Many and many a joy, Mary, has come and gone with the years, II. Still, without a thought or a prayer, Mary, that is not memory-born, III. Hope and delight still kneel Mary, tho’ the darkness has fallen at last, IV. Golden-lip’d glances of love, Mary, write song on my heart no more, V. All this is fully as well, Mary, as I could wish it to be, |

|||||||||

|

|||||||||

|

[Advert for Mary; and Other Poems from The Glasgow Sentinel (26 March, 1859 - p.8).]

The Era (10 April, 1859) MARY AND OTHER POEMS. By the Author of “Lyrics.” Mr. Buchanan, the author of this volume, has certainly the germs of poetry in him; and if he will prune and restrain his muse, rather than force her beyond her strength, he may do well. She will be a credit and comfort to him, but she will not put bread on his table, should he unfortunately expect that from her. The preface betrays more humility of expression than of feeling, and the dedication to Mr. Gilfillan is significant, as that gentleman is apt to raise false hopes in his proteges. It is very common for men of poetical temperament not to know how to use the riches of imagination, which they possess. Let Mr. Buchanan remember this, and neither flatter himself nor let others flatter him. He can now write prettily; with time, labour, and care, he may probably write well. If friends will tell him that he can write what Tennyson might be proud of (vide Critic), let him shut his ears to the deluding misjudgment, and rest assured that such competition is altogether out of his reach. ___

The Reasoner (29 May, 1859) Books of the Day. MANY of our readers remember the interest with which, many years ago, the youthful poems of Mr. Robert Buchanan were welcomed. An ardour which bespoke high feeling, and a poetic expression indicative of capacity, characterised those productions. We have now the pleasure of recording that the son has succeeded to more than his father’s honours. We have frequently seen in newspapers and magazine, poems by ‘Robert W. Buchanan.” which we now find, with very great pleasure, were the productions of Mr. Buchanan, jun., the young poet whom we have named. ‘Mary, and other Poems,’ is the title of a second volume which he has lately published. It is dedicated to the Rev. George Gilfillan, and we do not remember to have seen any volume inscribed to that gentleman so well worthy of his acceptance. We cannot enumerate the various poems—we may, however, say there are nearly every variety among them, that they indicate a true poetic faculty, and there is in them also the evident promise of higher things. |

|||||||||

|

|||||||||

|

[Advert for Mary; and Other Poems from The Athenæum (25 June, 1859).]

The Dundee Evening Telegraph (19 March, 1903 - p.4) AN UNKNOWN VOLUME OF ROBERT BUCHANAN. Through the kindness of a friend in Leeds, I have before me an unknown volume by Robert Buchanan (writes “A Man of Kent” in the “British Weekly”). It is not mentioned in the bibliography given by Miss Jay in her life of the poet. The title is, “’Mary, and Other Poems,’ by the Author of ‘Lyrics.’ Glasgow: Thomas Murray & Son. Edinburgh: Paton & Ritchie. London: Arthur Hall, Virtue, & Co. 1859.” The dedication is “To the Rev. George Gilfillan, of Dundee, this volume of verse is with permission respectfully dedicated by his admirer, the Author.” The preface is signed “Robt. W. Buchanan.” In the course of it Buchanan says:—“I know pretty well what a literary life is, and must ever be. I shall have to fight with Madame the World for many and many a long year, but I have set my foot to the mark, with the determination to keep up a stout heart. My rhymes of to-day are but the frail firstlings of the year, but they shall supply me with the germs of stronger flowers to come. Originality and promise identify poetic aptitude; but patience, study, and perseverance form the poet. Thus, encouraged by the success attendant on my first adventure, I come a second time—and I trust not unadvisedly—before the public; this time with more of confidence and courage in my mien.” Back to Reviews, Bibliography or Poetry _____

Book Reviews - Poetry continued Undertones (1863)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|