|

Play List: 4. Corinne 7. The Mormons 9. Lucy Brandon 10. Storm-Beaten 11. Lady Clare 13. Bachelors 14. Constance 15. Lottie 16. Agnes 17. Alone in London 18. Sophia 19. Fascination 20. The Blue Bells of Scotland 21. Partners 24. Angelina! 25. The Old Home 26. A Man’s Shadow 27. Theodora 29. Clarissa 30. Miss Tomboy 32. Sweet Nancy 33. The English Rose 36. Marmion 37. The Gifted Lady 38. The Trumpet Call 39. Squire Kate 40. The White Rose 42. The Black Domino 44. The Charlatan 45. Dick Sheridan 47. Lady Gladys 48. The Strange Adventures of Miss Brown 49. The Romance of the Shopwalker 52. Two Little Maids from School ___ |

|

ROBERT WILLIAMS BUCHANAN (1841 - 1901) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

THEATRE REVIEWS 23. That Doctor Cupid (1889)

That Doctor Cupid |

|

|

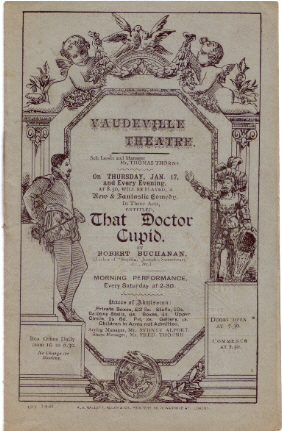

[Programme for That Doctor Cupid at the Vaudeville Theatre, 10 April, 1889.] |

|

|

[Thomas Thorne as Doctor Cupid and Winifred Emery as Kate Constant in That Doctor Cupid.]

The Era (1 December, 1888) MR BUCHANAN has read his new comedy to the Vaudeville company, and it will be put in rehearsal at once to follow Joseph’s Sweetheart. The subject is mainly original; the period chosen is about 1810, and the scene lies in Cambridge University and in Bath. The costumes will reproduce very accurately and amusingly the dresses worn by our grandfathers and grandmothers. Mr Thomas Thorne and the full Vaudeville company will appear, and Miss Winifred Emery will join to play the heroine. ___

The Globe (6 December, 1888 - p.6) Mr. Robert Buchanan’s new comedy, which is to follow “Joseph’s Sweetheart” at the Vaudeville, is to some extent a new departure. The scene is laid at Bath, abut the first decade of the present century, and the costumes will accurately and amusingly realise the follies and fashions of our grandfathers and grandmothers. The plot is original, but a suggestion for it has been found in the famous “Devil on Two Sticks” of Le Sage. It will be gathered from this statement that the interest is to a certain extent supernatural—indeed, it is rumoured that one of the leading characters is the Prince of Darkness himself. The whole Vaudeville company will appear, and in addition Miss Winifred Emery and Miss Fanny Robertson have been specially engaged. ___

The Referee (9 December, 1888 - p.3) “Dr. Cupid” was the title originally intended for the new comedy which Robert Buchanan has written for the Vaudeville; but it has been found that Mr. F. W. Broughton had some claim upon the name, and so it has been abandoned. When this piece (in which Thorne will play a matchmaking tutor) is produced some time in the new year, it will be preceded by a new comedietta, written by Mr. Broughton, and entitled “The Poet.” ___

The Morning Post (7 January, 1889 - p.2) Mr. Robert Buchanan’s new comedy—for which the title “Doctor Cupid” is proposed—will shortly be produced at the Vaudeville at a matinée to test its qualities, as the superseder of “Joseph’s Sweetheart,” whenever that popular piece shows signs of waning favour. Miss Winifred Emery, Miss Dolores Drummond, Mr. Thomas Thorne, Mr. William Rignold, and Mr. Frank Gillmore are in the cast. ___

The Echo (12 January, 1889 - p.1) It is many years since Mr. Robert Buchanan—whose new three-act comedy is to be performed at the Vaudeville next Monday—brought out his first play in London. After his Witchfinder, his three-act comedy A Madcap Prince was acted at the Haymarket in 1874. Other pieces of his are A Nine Days’ Queen, The Queen of Connaught, Paul Clifford, Lady Clare, Alone in London, Sophia—the last-named being acted at the Vaudeville nearly three years ago. ___

The Times (15 January, 1889 - p.7) VAUDEVILLE THEATRE. The Faust legend has employed many pens and has been adapted to the stage in many forms, of which the most successful have been the purely burlesque. Mr. Irving’s Faust was not so much an adaptation as a reproduction of the dramatic elements of Goethe’s poem, with all its diablerie and other supernatural effects; but even that play was more dependent upon stage carpentry than any of its fellows at the Lyceum. Of the difficulties attending a dramatic adaptation, properly so-called, of the Faust legend, a more cogent example was furnished a few years ago by Mr. Herman Merivale’s play, The Cynic, in which a modern Faust and Mephistopheles figured in London society, the Satanic personage being a certain foreign gentleman of Iago-like propensities, named Count Lestrange. Despite its clever writing, The Cynic failed to win popularity, and pointed clearly to the inadvisability of mixing up any suggestion of the supernatural with the ordinary affairs of human life, so far as the stage is concerned. With the results of this and kindred experiments before his eyes, Mr. Robert Buchanan, writing for the Vaudeville Theatre, has not hesitated to revert once more to “Faust” for inspiration, “Faust” being unquestionably the basis of the “new and fantastic comedy in three acts,” entitled That Doctor Cupid, which was tentatively produced by Mr. Thomas Thorne and his company yesterday afternoon. We say the “basis” only, for between “Faust” and That Doctor Cupid there is but little superficial resemblance. The supernatural personage called forth in Mr. Buchanan’s comedy is not Mephistopheles, but Cupid—Cupid no longer the winged little cherub of the ancients, but the god of love grown old and rheumatic, although still provided with his bow and arrow as an ornamental pendant to his watch chain. At the same time this novel character may very fairly be described as a benevolent Mephistopheles; in the functions assigned to him in the play there is certainly a great deal that recalls his Satanic prototype. ___

The Pall Mall Gazette (15 January, 1889) “THAT DR. CUPID” AT THE VAUDEVILLE. DETERMINED once more to outwit the first night “wreckers,” whom he holds in perhaps exaggerated horror, Mr. Thorne produced Mr. Buchanan’s new comedy, “The Dr. Cupid,” at the Vaudeville yesterday afternoon, before an audience consisting mainly, in the reserved parts, of critics and actors, among whom were Mr. Toole, Miss Harriet Jay, Mr. Arthur Dacre, Mr. Arthur Stirling, Mr. John Coleman, Miss Norreys, Mr. Yorke Stephens, Mr. and Mrs. H. A. Jones, and others. Mr. Buchanan acknowledges a slight indebtedness to Foote’s farce “The Devil upon Two Sticks,” from which he has borrowed an incident in the first act; otherwise his play is entirely original. This incident, however, is the starting-point of the play, which is fantastic in style and supernatural in machinery. Heine as well as Foote seems to have been laid under contribution. The magic bottle belongs to the English Aristophanes, but for its contents Mr. Buchanan has surely gone to the “Gods in Exile” of the German Lucian. There is also a strong suggestion of Mr. Gilbert in the love-at- cross-purposes which forms the matter of the second act; but Mr. Buchanan’s humour is quite innocent of the peculiar Gilbertian twist. Harry Racket, a Cambridge undergraduate of eighty years ago, whose name conveniently indicates his habits, has had foisted upon him by an old usurer a collection of worthless “curios.” Among them is a glass jar, labelled “Amor vincit omnia sed scientia captat amorem,” and containing, apparently, an india-rubber doll, and in a fit of despair at the contrariety of the world in general Master Harry seizes the jar and flings it into the fire. Instantly the stage is darkened, and a quaint figure is dimly seen crouching in the fireplace. This is none other than Cupid, now an aged and somewhat rheumatic deity, who has been “bottled” since the reign of Elizabeth, and now, in gratitude to his deliverer, devotes himself to his service. At the end of the first act, the pair take flight to Bath, after the manner of Faust and Mephistopheles in the recent Lyceum spectacle. In the second act, Dr. Cupid, passing as Harry Racket’s tutor, sets the world of Bath by the ears and no whit advances his pupil’s cause. He speeds the shafts of desire so much at random (his cocked hat symbolizing his bow) that every one falls in love with the wrong person, the hero and heroine quarrel desperately, and society is reduced to an amatory chaos. The only sentiment in which all are agreed is a longing for vengeance on the sportive old blunderer who has wrought all the mischief. In the third act, fortunately, a little diplomacy and a few well-directed darts put matters straight again, and the “sweet bells” of matrimony are no longer “jangled out of tune and harsh.” It cannot be said that Mr. Buchanan has altogether avoided the pitfalls of vulgarity which obviously beset such a theme, but he has produced an adroit, lively, and sufficiently novel play, exactly suited to his actors and his audience. It was received with acclamation by the afternoon public, and there is no reason why it should not prove equally attractive “at night.” Mr. Thorne’s Dr. Cupid is a quaint and genial performance; Mr. Frank Gillmore plays Harry Racket with plenty of youthful spirit; Miss Winifred Emery as the heroine gives us no cause to regret too poignantly the absence of Miss Kate Rorke from the cast; Mr. Cyril Maude scores a great success as a stammering lover; Miss F. Robertson and Miss Dolores Drummond are sufficiently amusing as two amorous ladies of a certain age; and Mr. F. Thorne is excellent as a testy and hypochondriac country squire. The dresses, designed by Mr. Karl, are extremely quaint and effective, and it must be added that the performers wear the high-collared Tom and Jerry coats and Directoire skirts of our grandfathers and grandmothers with remarkable ease. ___

The Daily News (15 January, 1889) MR. BUCHANAN’S NEW COMEDY The audience at the Vaudeville Theatre yesterday afternoon found Mr. Robert Buchanan in a new mood. “Sophia” and “Joseph’s Sweetheart” presented us with genuine comedy scenes and delightful pictures of English domestic life in byegone days. “That Doctor Cupid” deals also with the past; but it is conceived in a widely different vein. Its author describes the play as “fantastic,” and the epithet is certainly not misapplied. We gather from the acknowledgment that he has borrowed a hint from Foote’s old farce “The Devil on Two Sticks,” which in its turn was indebted to the “Diable Boiteux”; but the treatment, no less than the conception, is rather in the spirit of Mr. Gilbert’s “Creatures of Impulse,” and here and there it is impossible not to be reminded of the immortal John Wellington Wells. Still there is a boldness and decision amounting in themselves to originality in the way in which Mr. Buchanan—without the aid of music, so potent in taking the reason prisoner—goes about the business of uniting the real with the ideal, the matter of fact with the supernatural and blending with these incongruous elements the boisterous mirth which is apt to render wild imaginings rather absurd than impressive. Rejoice and echo in your exultation the curtain falls. Without unflagging spirit and thorough sincerity in the acting it might fare ill with a piece so wildly extravagant; but Mr. Buchanan has been in this respect singularly fortunate. There is no limit to Mr. Thomas Thorne’s vivacity and agility in the part of the Doctor. The “gay restlessness of limb” which Leigh Hunt discovered in the actor Lewis is certainly not wanting to Mr. Thorne; nor is the abandonment which never suffers the spectator to consider the why and the wherefore of his strange behaviour. Miss Emery’s sweet, good-natured impulsiveness and Miss Lea’s overflowing fun and banter serve equally in good stead; and Mr. Frederick Thorne contributes in the violently self-willed hypochondriac Sir Timothy a study of character which is one of the most effective factors in some of the best comedy scenes in the play. As to Mr. Cyril Maude’s stutter, which compels him in despair to write the declaration of love which he cannot otherwise make thoroughly intelligible, it is quite indescribable in its mirth-provoking qualities. The minor parts assigned to Miss Dolores Drummond, Mr. Wheatman, Mr. Buist, and Mr. Pagden were also without an exception well played. We have already referred to the costumes. Mr. Walter Crane and Miss Greenaway have helped us to perceive that our great-grandmothers’ attire was not so dowdy and hopelessly old-fashioned as it once was thought; but to know what elegance can lurk in the round gowns and furbelows, the high waists and large “ridicules,” the scarves and the sashes of the days when King ruled over the New Assembly Rooms, the curious should see the ladies in Mr. Buchanan’s play. A similar remark, with due abatement for the less graceful sex, applies to the high collared, gilt buttoned, swallow- tailled, green, red, and claret-coloured coats, and the dove and canary breeches and pantaloons of the gentlemen. Mr. Gillmore not only plays but looks the young college exquisite of the period to the life. Whether the fantastic extravagances of Mr. Buchanan’s piece are “for all markets” can only be proved when it is transferred to the evening bill, and submitted to the approval of a more normal tribunal than that which gathers at a first matinée performance; but that they greatly diverted the audience yesterday was abundantly evident in the enthusiastic reception accorded to all parties concerned. ___

The Morning Post (15 January, 1889 - p.5) VAUDEVILLE THEATRE. Mr. Robert Buchanan’s new three-act comedy, entitled “That Doctor Cupid,” was produced at the above theatre yesterday afternoon. The author calls it “fantastic,” a term which implies a departure from the ordinary lines of comedy, and, in fact, the author does entirely get out of the beaten track in the blending of natural and supernatural incidents he has employed. Mr. Buchanan claims to be “new and original” in his plot and characters, with the exception of one scene, suggested by the old farce of “The Devil on Two Sticks,” by Foote, played at the Haymarket as far back as 1768. The comedy opens at Cambridge, and the action is continued and concluded at Bath. At Cambridge University a rattle- brained student, Harry Racket has spent all his money, offended his uncle upon whom he is dependent, and is in the clutches of the money-lenders, while he has engaged himself to Kate Constant, a pretty young heiress who will lose her fortune if she encourages the scapegrace. Harry has borrowed money of a Mr. Plastic, who makes it a condition of the loan that he shall accept a parcel of stuffed birds and curiosities, and these being sent to his rooms just as Harry’s uncle, Sir Timothy, has written to discard him, the young man in a fit of passion begins to smash the article the money-lender has sent. Among them is a singular old-fashioned bottle, in which some object has been preserved, but when the young man flings it in the fire-place the room grows dark, and there emerges a fantastic figure, who yawns and stretches himself, and inquires if Queen Elizabeth is dead. Being assured that Good Queen Bess is no longer on the Throne the strange personage explains that he has been shut up in the bottle by Dr. Dee, but that his mother was Venus Aphrodite, and that he was once the naughty little boy who turned the heads of all the maidens. Delighted with his freedom, he proposes a compact of the Faust and Mephistopheles kind, only that gratitude induces him to ask no recompense for his services. He promises to aid Harry in obtaining the forgiveness of his uncle and also the lady’s hand. With alacrity the hero accepts the offer, and only desires to be taken to Bath, where Kate is staying. The next act takes place at the Bath Assembly Rooms, where Dr. Cupid, arrayed as a dandy of the period, makes havoc with the fair visitors. They are in a flutter of excitement, and never was seen such an epidemic of flirtation amongst that staid assemblage. Beau King, the master of the ceremonies, is horrified, and requests Dr. Cupid to preserve a little decorum, but the gay old boy, who appears as Harry’s tutor, cannot restrain himself, and the consequences are perplexing in the extreme. Every gentleman is paying devoted attention to the wrong lady, and every lady is suddenly smitten with violent fancies for the suitors of their lady friends. To crown all the mischief “That Doctor Cupid” is doing, he has caused another lady to fall desperately in love with Harry, and Kate, in passionate jealousy, has promised her hand to Lord Fungus, whose suit had been already urged by her aunt. The scene of confusion at the fall of the curtain on the second act was wildly farcical but unquestionably funny, and the audience awaited in a merry mood the scheme by which true lovers would be reconciled and false ones put to shame. This is accomplished by Dr. Cupid, who, repenting his volatile conduct, undertakes to work upon the amatory feelings of the personages concerned, with the result that Harry and Kate make up their quarrel, and the gouty and fierce old uncle, who has been the prey of his housekeeper, is made to understand her mercenary motives and forgives his nephew, the comedy ending with a few lines in which Love is eulogised as the chief cause of human happiness. The piece is undeniably “fantastic;” in fact, it would seem that Mr. Buchanan has taken a leaf out of Mr. Gilbert’s book, as it only needs some lyrics added and the music of Sir Arthur Sullivan to make a comic opera of the kind so long popular at the Savoy. This will be a recommendation to many, and for those who can enjoy a little “Topsy- turveydom” of the Gilbertian school “That Doctor Cupid” will find much favour. It was greeted with hearty laughter and applause during its progress, and at the close the author was called for and welcomed cordially. There is a prominent character in the new comedy for Mr. Thomas Thorne, who plays Dr. Cupid with genuine humour. The gaiety and whimsicality of the character recalled the days when Mr. Thorne used to play so gaily in burlesque. But there is a neatness and polish in his acting of Dr. Cupid which raises it far above mere burlesque, and he delivers the fanciful lines with so much point that the author has reason to be grateful to him, while the audience applauded heartily. Mr. Fred. Thorne appears as Sir Timothy Racket, the gouty old uncle, who is cajoled by his housekeeper and is violently offended with his nephew. Mr. Fred. Thorne made the blustering, foolish old fellow amusing and eccentric enough. Much commendation may be given for the easy and natural manner in which Mr. Frank Gillmore represented Harry Racket, the wild young Cambridge student, over head and ears in love and in debt, and full of mischievous pranks as well. As Charles Farlow Mr. Cyril Maude was amusing in making fun of the peculiarities of a stuttering lover, who, though absurd, is still a gentleman; Mr. Wheatman, in the character of Barney O’Shea, a college servant, efficiently sustained his little part; and some refinement of manner was appropriately employed by Mr. Scott Buist as Lord Fungus. The few lines allotted to Mr. Pagden as Plastic, a money-lender, were carefully delivered; and Mr. F. Grove, as Beau King, of Bath, may be credited with doing his best. Excellent aid was given in the performance of the heroine, Kate Constant, by Miss Winifred Emery. The gushing affection, the caprices of temper, the wayward moods and sudden jealousy of the heroine when under the spells of Dr. Cupid were productive of much amusement. Miss Emery was very successful throughout. Miss Marion Lea as Mrs. Bliss, a young widow with a tendency to flirtation, which makes her an easy victim to Dr. Cupid, was excellent; and Miss Dolores Drummond gave a clever rendering of Mrs. Veale, the artful and intriguing housekeeper; and the amusing quaintness of Miss F. Robertson as Miss Bridget Constant, the heroine’s aunt, greatly increased the fun of the comedy. It would be “breaking a butterfly on the wheel” to subject a merry bit of extravagance like “That Doctor Cupid to severe criticism, or to pull to pieces the foundations upon which it is built. Few will be disposed to pick critical holes in a fabric specially constructed to amuse light-hearted playgoers, who will, we have little doubt, appreciate the harmless fun and the capital acting when “That Doctor Cupid” has the chief place in the evening programme. The fantastic comedy was completely successful, and great praise must be awarded for the admirable manner in which it is placed upon the stage. ___

The Standard (15 January, 1889 - p.3) VAUDEVILLE THEATRE. Mr. Thorne yesterday afternoon produced a new play, That Doctor Cupid, by Mr. Robert Buchanan. The play begins in the room of Harry Racket, a young spendthrift, who is amusing himself much, and reading little, at Cambridge in the time of George III. He is over head and ears in debt, which troubles him the more because his uncle, Sir Timothy Racket, is displeased at his behaviour, and that displeasure means the loss of the hope of marrying Kate Constant, a charming girl, to whom he is attached. Racket is living on borrowed money; the last loan has been advanced partly in the shape of curiosities—butterflies, skulls, stuffed birds, and a mysterious bottle, which latter he breaks in a fit of despair, brought on by the news that he is cut off by his uncle, and forced to renounce Kate. But a marvel happens. As the bottle breaks in the fireplace, where he has thrown it, darkness overshadows the room, and a strange figure, in Elizabethian dress, steps from the chimney. It is Dr. Cupid, the veritable God of Love, grown old and very stiff by reason of centuries of confinement in his glass prison. Dr. Cupid is bound to help the man who releases him, and informs Racket that he may command obedience. Kate has gone to Bath, so thither Racket would go also; and, clinging to the Doctor’s coat tails, he jumps from the window. Bath is the scene of the two following acts, and it is soon made evident why Sir Timothy is prejudiced against his nephew. The old man has a designing housekeeper, Mrs. Veale, who has made up her mind to marry her master, and to do this she must keep Racket out of favour. But Dr. Cupid is a potent ally, for with a shaft from his invisible, but not inaudible, bow he can make people fall in love just as he chooses, and he sets to work: the trouble being, however, that, grown old and out of practice, he sadly blunders, and Racket’s position becomes worse than ever, Kate is incensed with him and vows she will marry his rival, Lord Fungus, and other couples are set by the ears. This second act drags somewhat towards the end, when the plot becomes rather involved; however, the complications are effectually cleared up by Dr. Cupid. ___

St. James’s Gazette (15 January, 1889 - p.6) “THAT DOCTOR CUPID.” THE new play by Mr. Robert Buchanan produced at the Vaudeville yesterday afternoon is less after that dramatist’s customary manner than after Mr. W. S. Gilbert’s as displayed in his “Foggerty’s Fairy” or his “creatures of Impulse.” This latter piece, indeed, “That Doctor Cupid” resembles in motive as well as in method, for it deals with the impulsive love affairs of a number of people peculiarly affected by a supernatural influence suddenly introduced in their midst. The proceedings, accordingly, of the dramatis personæ belong half to comedy and half to fantastic extravaganza; and as the scene is laid in that eminently prosaic period the beginning of the present century, the general effect is bizarre and a trifle bewildering in its incongruities. The rooms of a dashing undergraduate at Cambridge somewhere about the year 1810 are about the last place in the world where one would expect to see a sprite uncorked from a bottle and let loose upon society; while formal ladies in the short-waisted dresses of our grandmothers and stiff gentlemen with knee-breeches and high coat-collars seem the unlikeliest of folk to cut eccentric capers at the bidding of the little god of love. These emphasized improbabilities, or we should rather say impossibilities, all belong to the deliberately adopted scheme of Mr. Buchanan’s work, which has at least the merit of striving to get out of the beaten track and to achieve some fresh kind of interest. Upon the ordinary three-act comedy introducing old-English characters—the testy uncle, the spendthrift nephew, and the fashionable dames taking the waters at Bath—“That Doctor Cupid” is certainly a daring innovation. For this reason, and because its dialogue is written with some sense of literary taste, it deserves consideration more favourable than could be commanded by its somewhat obvious humours, its perfunctory development of plot, and its extremely mild sympathetic interest. With its oddity, in fact, ends it chief claim upon public attention; and it is, perhaps, doubtful whether this claim would be allowed by a general audience at night as freely as it was by the special class of playgoers present at its trial trip yesterday afternoon. ___

The Daily Telegraph (15 January, 1889 - p.3) VAUDEVILLE THEATRE. Mr. Buchanan’s new play is by no means free from the inconsistencies and anachronism which a dramatic author may be said to impose upon himself by importing the supernatural element into pieces intended for the stage. Nor is the fundamental idea, the plot, or the action of “That Doctor Cupid” characterised by striking originality. On the contrary, the piece suggests pleasant reminiscences of old-fashioned fictions and modern “topsy-turvy” plays, in which immortals, malignant or benevolent, exert their powers, each after his or her kind, to complicate the problems or unravel the tangles of human destiny. The play, however, is an amusing one—brightly written, cleverly constructed, and, more especially throughout its second and third acts, teeming with high spirits, even to overflowing. Its story may be briefly summarised. ___

The Glasgow Herald (15 January, 1889 - p.5) OUR LONDON CORRESPONDENCE. 65 FLEET STREET, . . . A trial performance was given at the Vaudeville Theatre this afternoon of a new three-act comedy entitled “That Doctor Cupid,” by Mr Robert Buchanan. It is understood that the piece was written with the intention that it should succeed “Joseph’s Sweetheart,” the run of which is now nearing its termination, and happily for the author and the management the verdict of to-day’s audience was wholly favourable. At first it seemed as if smart dialogue would have to atone for a common-place plot. Harry Racket is a dissipated Cambridge undergraduate, who has alienated his rich uncle Sir Timothy, and is a prey to the money-lending fraternity, though he retains the affections of his cousin, Kate Constant, a very lively young person, quite innocent of maidenly coyness and timidity. Harry has to accept a loan, partly in cash and partly in “curios,” and among the latter is a singular bottle, which in a fit of passion he smashes. It contains the spirit of the god Cupid, who, on resuming his bodily form in the person of Mr Thomas Morney, is found to have become a rheumatic old gentleman. He promises every assistance to his deliverer, but at first he only complicates matters by causing every girl to fall in love with his young protégé. In the end, however, he proves more serviceable by pairing off a number of eligible people. This fantastic idea, of course, recalls “Le Diable Boiteux,” and some were present who remembered Mr Geoffrey Hudson’s impersonation at Drury Lane. But the details are new, and there is much that is bright and amusing in Mr Buchanan’s latest effort. The rhymed tag, in which there is a slight aroma of poetry, brought down the curtain very effectively. The author was fortunate in his exponents—Miss Winifred Emery, Miss Marion Lea, Mr T. and Mr F. Thorne, Mr Frank Gillmore, and Mr Cyril Maude being the most prominent members of an excellent cast. ___

The Stage (18 January, 1889 - p.9) THE VAUDEVILLE. On Monday afternoon, January 14, 1889, was produced a new and fantastic comedy, in three acts, written by Robert Buchanan, entitled That Doctor Cupid. Sir Timothy Racket ... ... Mr. Frederick Thorne It is, it must be confessed, a somewhat difficult matter to justly value this latest work from Mr. Buchanan’s versatile pen. It defies analysis: described as a “fantastic comedy,” it opens with a vein of serious dramatic interest, later it develops into the supernatural, treated after the Gilbertian method, and finally it winds up with rattling farcical comedy. The supernatural introduction of the title character is avowedly taken from The Devil on Two Sticks, an old play of ephemeral popularity, in its turn founded upon the celebrated Le Diable Boiteux. The scene of the first act is laid at Cambridge, in the college rooms of one Harry Racket, the spendthrift hero of the play. This young fellow, having by his madcap tricks worn out the patience of his rich and gouty uncle Sir Timothy, finds himself penniless and deeply in love with his pretty cousin, Kate Constant. Kate returns his love, but her aunt favours the suit of a certain wealthy Lord Fungus, so the lovers have only to mingle their tears, swear constancy, and part. This they do, leaving Harry solus: he, in a despairing mood, soliloquises and picks up an old jar, one, it should be explained, of several “curiosities” that have been foisted on him as part exchange for a bill by a rapacious money lender. Addressing the quaint doll-like figure preserved in the jar, he moralises upon the vanity of human wishes, and becoming persuaded of the futility of his life, pitches the jar into the fire. With strange result, for the scene darkens, thunder is heard, the fire burns uncannily, and out of the glow waddles an elfish creature who, stretching and yawning, gradually discovers himself as a full-grown and rheumatic person of more than middle-age, attired in Elizabethan ruff, doublet, &c. To the bewildered youth’s naturally curious questions the strange figure introduces himself as Cupid, and explaining that through the evil machinations of an alchemist he had for three centuries been confined in the bottle, whence young Harry Racket had just released him. In proof of his gratitude for the service, he offers to assist Harry to regain his uncle’s favour and Kate’s hand. His means, however, to Harry’s regret, do not extend to the supply of unlimited cash, though they are potent enough to enable the pair to set out on an aerial journey for Bath, the scene closing in semi-darkness as the companions step from the window-sill. In the second act, “at the ante-room of the Assembly Rooms, Bath,” Cupid appears as Harry’s tutor, adopting for the purpose the title of Doctor. Sir Timothy enters, attended by his housekeeper, Mrs. Veale, a scheming person, who humours the irascible old hypochondriac, with a view of marrying his money, and the remaining characters are introduced, including Charles Farlow, an excitable, stuttering young fellow, in love with a roguish widow, Mrs. Bliss; Lord Fungus, the suitor to Kate Constant; and Beau King, the master of the Assembly Room ceremonies. In his endeavours to serve his master, Dr. Cupid makes blunders sufficient to set everyone by the ears. All the women but Kate fall in love with Harry, with the result that Kate throws him over for Lord Fungus, and Sir Timothy, furious at Mrs. Veale’s desertion, also renounces him, the act closing with a general denunciation of the author of the mischief. The third and concluding act, which passes on St. Valentine’s morning at the Lover’s Well, Bath, serves the unlucky Cupid with an opportunity of undoing the mischief he had unwittingly brought about. Harry and Kate, Farlow and Mrs. Bliss are united, old Sir Timothy relents, and the curtain falls on general happiness as Cupid, released from his debt of gratitude to his liberator, prepares to return to his classic home, there to renew his youth, and, it may be supposed, his mythical duties. In the two last acts there is ample scope for fun in the farcical intermixing that goes on through the ill-managed zeal of Cupid, and on these must the success of the play chiefly depend. There is considerable ingenuity and much boisterous humour in the intrigues developed, and on Monday the two acts proceeded with a running accompaniment of laughter and applause. The play is now put in the bill as the permanent evening attraction, and will doubtless draw for a considerable run, though there is room for doubt whether it will rival in success the two clever comedies from the same pen which it succeeds. That Dr. Cupid is a daring, almost a brilliant piece of work, and one, in its dealing with a difficult subject, of notable interest to experts in play-writing is certain, but there is a want of human interest in its characters that, with the general public, may tell prejudicially, despite its high spirit and unbounded humour. The dialogue is pointed and close; it contains some lines which on Monday lent themselves to risky misconstruction, and might be revised with advantage. The date assigned to the play, the beginning of the present century, gives scope for some bright and effective dressing of the high-waisted Kate Greenaway costumes for the ladies, and the equally quaint and picturesque coats and pants of our great grandparents’ days. Mr. Thomas Thorne made a most diverting Cupid; had the part been in the hands of any but an experienced and popular comedian, the success of the piece must have been endangered;—a difficult part, indeed, to play, but Mr. Thorne made every line and incident tell with his quaint humour. Mr. Frederick Thorne gave a highly-finished character sketch of Sir Timothy. Every peculiarity of the gouty, testy, self-willed old fellow was marked out with rare artistic skill; throughout he was pictured to the life. Young Racket—the name gives an index of the character—was played briskly and capitally by Mr. Frank Gillmore, whose performance gives promise of better things than the part allows him opportunity for. Mr. Cyril Maude as Charles Farlow gave an extraordinarily funny rendering of a stammering dandy lover, whose tongue fails him in the impetuosity of his love and jealousy. The remaining male characters, of minor importance, are efficiently done, Mr. F. Grove in particular being excellent as Beau King. Miss Winifred Emery played Kate Constant with that lackadaisical gush which appears to have been so generally characteristic of ladies of the period, and with no little charm of her own superadded. Miss Marion Lea exactly caught the spirit of her part, as a coaxing, pouting young widow; while the maiden aunt, Miss Bridget Constant, and the scheming Mrs. Veale, were played by Misses Dolores Drummond and Fanny Robertson respectively, in a proper vein of caricature, funny enough, but not over-acted. The dresses, by the way, were from designs by Karl, and executed by Messrs. Nathan and Sons. At the conclusion of the matinée on Monday there was enthusiastic applause, the company were recalled, and finally the author, who bowed his acknowledgements for the unmistakeable favour with which the play was received. ___

The Graphic (19 January, 1889) THEATRES. IN That Doctor Cupid, produced at a matinée at the VAUDEVILLE on Tuesday, Mr. Buchanan confesses to have taken the hint from Foote’s once famous farce founded upon Le Diable Boiteaux of Lesage; and it must be confessed that he has gone about the business of uniting sober reality with supernatural agency in a thoroughly confident and decided fashion. When we say that a little squat figure, preserved in an apothecary’s bottle about two feet in height, is supposed to be Cupid, in the person of Mr. Thomas Thorne, grown old, but, like Anacreon in his decline, still stirred by amatory raptures, we have said perhaps enough to show that the dramatist shrinks from no demand upon the faith of the spectators. This mystic element is introduced as the climax of a purely comedy-scene supposed to pass in the lodgings of young Mr. Racket, an extravagant scapegrace-undergraduate at Cambridge, in or about the prosaic period of 1806. Nothing, it must be confessed, in the colloquy between Harry racket and the extortionate money-lender, who insists on his victim accepting a mass of old curiosities—the wonderful bottle included —as part of the advance on a note of hand at usurious interest, tends to prepare the mind for the startling incident which follows, when Racket dashes the bottle, in his rage, into the empty fire-grate. Still less does the tender scene between him and his faithful sweetheart, Miss Kate Constant, broken-hearted at being commanded by her imperious aunt to renounce the scapegrace who has been discarded by his gouty and furious old uncle, Sir Timothy, give warning of the sudden darkening of the stage as the bottle flies into fragments, or the mystic flashes of light for the sudden appearance of Mr. Thorne as the wayward son of Aphrodite, sadly cramped and bowed by his three centuries of confinement, but ready as ever to play havoc with the hearts of men and women. But Dr. Cupid merely offers to take his deliverer to Bath, show him the fashionable world of that idle resort of health and pleasure-seekers, and there wait for something to turn up. ___

The Era (19 January, 1889) “THAT DOCTOR CUPID.” A New and Fantastic Comedy, in Three Acts, Sir Timothy Racket ... ... Mr FREDERICK THORNE The author of That Doctor Cupid, which is very correctly called a fantastic comedy, acknowledges that he is indebted for a suggestion for his work to Foote’s famous farce The Devil Upon Two Sticks, produced with extraordinary success at the Haymarket Theatre on May 30th, 1768. He reminds us, though, that Foote’s piece was merely a satire on the medical profession, and boldly asserts that, beyond supplying a leading incident of the first act, it had nothing in common with his latest comedy, “which is otherwise entirely original.” Most English comedies, says an eminent critic, are too long. Now, if it cannot be said that Mr. Buchanan’s fantastic comedy is too long in point of time occupied in the representation, it must be asserted that its fun, of which there is ample for two acts, suffers by being spread over three, and that there is some danger that the laughter which is legitimately produced in the full development of the author’s idea may, before the end is reached, give way to weariness born of vain repetition. Mr. Buchanan has set himself the task of illustrating in humorous fashion the fact that Cupid’s the doctor who enters all portals, sly old concoctor of physic for mortals, and particularly to emphasise the undeniable truth that “sometimes he blunders,” making war where peace should be, and creating hatred where love was looked for. There is, as might have been expected, a distinct literary flavour in the dialogue, with a good deal of wit, spoiled only by the introduction of puns, which have been declared on excellent authority to be the lowest kind of wit. The intrigue, doubtless, is ingenious enough, but at the same time is terribly bewildering. Up to the end of the second act the confusion is diverting, because it is easily followed, but when Doctor Cupid in the third goes to work to correct his own blundering, confusion becomes “worse confounded.” Confusion, however, may be found as welcome in “fantastic” as in farcical comedy, and without a doubt if it make them merry the Vaudeville patrons will not be disposed to complain. ___

The Academy (19 January, 1889 - No. 872, p.47-48) THE STAGE. A FANTASTIC COMEDY. MUCH reminiscence of eighteenth-century comedy and a little reminiscence of “Faust”—these, with the contributions of his own prolific fancy, are the materials out of which Mr. Buchanan has wrought his new piece for the Vaudeville. Simultaneously with what is meant to be the presentment of the manners of everyday humanity in the last years of George III., there proceeds such action as may be supposed to be the natural consequence of the sudden liberation of one who is none other than Dan Cupid from a bottle in which he has long been confined. Cupid places himself good-naturedly at the service of the youthful gentleman who has accidentally and unconsciously set him free; and through the remaining acts of the piece he is engaged in compassing that youth’s desires, now with much ingenuity, and now with a clumsiness that comes of a want of recent practice. Surprising are the pranks he plays, and the effects of them upon old and young. The scene is laid first at Cambridge, where Cupid is emancipated, and afterwards at Bath, where he practises. His is, undoubtedly, the leading part. The best scenes are the scenes in which he scores, and the movement of the comedy is chiefly in his hands. His character we will not attempt to describe, for he is one of the oldest, one of the most familiar, and, probably, the most popular of personages upon the world’s stage. FREDERICK WEDMORE. ___

The Illustrated London News (19 January, 1889 - p.6) “THAT DOCTOR CUPID.” Mr. Robert Buchanan, singularly successful in adapting a brace of old English novels to the Vaudeville stage under the titles of “Sophia” and “Joseph’s Sweetheart,” has had the good fortune to furnish Mr. Thomas Thorne with a fresh triumph in the form of a new “fantastic comedy” of an Asmodean character. “That Doctor Cupid,” essayed at a Vaudeville matinée on the Fourteenth of January, occasioned so much merriment by its droll situations and diverting acting, surprisingly finished for a first morning performance, that it was resolved to place the novel play in the evening bill the same week. “That Doctor Cupid” escapes from his bottle, after the fashion of “Le Diâble Boiteux,” in the nick of time to come to the rescue of Harry Rackett, a young Cambridge student, who, over head and ears in debt as well as over head and ears in love, finds himself in danger of losing the lass he loves. How vivacious and irrepressibly rakish Dr. Cupid spirits him away to fashionable Bath, causes every lady to fall in love with Harry, and thereby provokes his own dear Kate, out of pique, to accept the hand of a rich suitor, but eventually reconciles hero and heroine, must be seen to be appreciated. From first to last, “That Doctor Cupid” won the favour of the audience; and at the end of the piece Mr. Buchanan was warmly applauded. As “That Doctor Cupid” Mr. Thomas Thorne was remarkably lively, and won many a laugh by the effectiveness of his archery. Miss W. Emery and Mr. Frank Gillmore were altogether admirable as Kate and Harry Rackett; and Mr. Cyril Maude, in a capital stuttering part, and Miss Marion Lea were similarly good; while Mr. Frederick Thorne, Miss Dolores Drummond, and Miss F. Robertson infused the requisite amount of humour into the character-sketches of Sir Timothy Rackett, Mrs. Veale, and Miss Constant. ___

The Illustrated Sporting and Dramatic News (19 January, 1889 - p.12) DRAMA. VAUDEVILLE THEATRE. MR. ROBERT BUCHANAN’S new comedy That Doctor Cupid, successfully tried at the Vaudeville on Monday afternoon, is a piece which seems eminently likely to provoke considerable differences of opinion. One can imagine different playgoers pronouncing it clever and silly, fresh and familiar, smart and aimless—and all with some reasonable justification. About one thing there can be no doubt: the play is an odd one, and marks what is for this particular theatre a completely new and very bold departure. Though its characters in their short-waisted frocks and straight skirts, their coloured swallow-tails and high collars, belong to much the same period as the dramatis personæ of recent productions here, they are of a wholly different order of creation. Motive and colouring alike are fantastic, and the action is so wholly irresponsible that the staid society of Bath ninety years ago is made to put up with the wild antics appropriate to Gilbertian fairy play or Palais Royal farce. Then again the supernatural element introduced is treated with anything but reverence, and yet is all-important to the plot, whilst the romantic interest of the story has genuine sentimental significance. The dialogue is telling without being witty, and if occasionally deficient in refinement is yet not wanting in literary taste, whilst the characters are drawn with a certain fresh force, though they most of them have their obvious prototypes. In fact, That Doctor Cupid is a strange medley of fairy extravaganza and genuine comedy, more curious than interesting perhaps, but at any rate quite capable of affording a pleasant entertainment for an empty afternoon. It remains, however, to be seen whether now that it is promoted to the post of honour and responsibility in the regular evening programme it will satisfy equally well the demands of the general public; for, as has been often proved, the successful matinée is one affair, and the popular evening run is something quite different. ___

St. Stephen’s Review (19 January, 1889 - p.19) That Doctor Cupid was produced by Mr. Thorne at the Vaudeville on Monday afternoon, when Mr. Buchanan’s new and fantastic comedy met with more than a succés d'estime. Whether it is eventually destined to achieve the popularity of either Sophia or Joseph’s Sweetheart is a question upon which we had as yet rather be silent. With Messrs. F. Gillmore and Cyril Maude, Mesdames W. Emery, F. Robertson, and Dolores Drummond, and the genial lessee in the title rôle, spectators were sure of a capital performance. They were not disappointed, and the dash and spirit of the thing were undeniable. The blending, however, of the supernatural with polite “costume” comedy is a ticklish business, and it may be that Mr. Buchanan would have been better advised had he stuck to his last—but not least fruitful—sources of inspiration. As originally contrived, the piece concluded with the waking of the characters from a dream, though this idea was abandoned on Monday, as we think, very properly. But as “Doctor Cupid” comes out of a bottle, in the first instance, he should certainly vanish or regain his bottle when his usefulness is o’er. This he did not do on Monday. ___

Lloyds Weekly London Newspaper (20 January, 1889 - p.5) PUBLIC AMUSEMENTS. VAUDEVILLE THEATRE. Discarding Fielding, Mr. Robert Buchanan has turned to the supernatural for the subject of his latest three-act comedy, That Doctor Cupid. The piece is designed to occur at the beginning of the century at Cambridge and Bath, but would be far more appropriately fixed at a German university where superstition and Faust legends are ever popular. Harry Racket, the hero of Mr. Buchanan’s fantastic effort, is a handsome young man, with all the vices of drinking, gambling, and borrowing. A moneylender palms on to him. as portion of value for an I O U a number of unconsidered trifles and curios, among which is a curious imp in a bottle. The strange thing seems to glare and mock at the young man, and he dashes the frail glass violently to the ground. Instantly—as sudden as the apparition in Faust—there rises up a supernatural creature, who announces himself as the real original Cupid, son of Venus Aphrodite. He has been confined in the bottle for a period of three centuries, and proposes to aid his deliverer in all matters without the objectionable bond that is such a feature in Goethe’s version of demoniac aid. Doctor Cupid admits at the outset that he cannot command money but he can command love, and the first act closes as the first scene of the Lyceum Faust, with the departure of Racket—by the aid of his new friend’s cloak—for Bath. The supernatural is subordinated to the comic element, so that the demoniac effects are not very strong. Let it be said at once that Mr. Thomas Thorne plays this middle-aged Cupid, and that he romps through the two following acts, shooting imaginary darts and making violent love to every female in the play. He is supposed to reconcile Harry’s uncle, and the young gentleman is left with every prospect of happiness in espousing the lady of his choice, Miss Kate Constant. On Monday afternoon, when the fantastic piece was tried at a matinée, it was received with much favour, but Mr. Buchanan might do well to reconsider some of the lines by which he raises a laugh. Mr. Thomas Thorne played Cupid in a whimsical, exuberant fashion that quite won over the audience; and a very odd character sketch of a stuttering lover who can never manage to propose properly was given by Mr. Cyril Maude. The Harry Racket was Mr. Frank Gilmore, a young man of fine presence, who should become a fashionable stage lover; Miss Winifred Emery was the Kate Constant, looking well in the dress of our granddames; and Frederick Thorne was one of those blustering and quaintly irritable uncles always found in old comedy. ___

The Referee (20 January, 1889 - p.2) DRAMATIC & MUSICAL GOSSIP. “BLESSED be the man who invented matinées.” So say the managers, and so, too, say plenty of their patrons who reside away from theatrical centres, or who don’t care to trouble to dress for evening performances. Two letters in the word blessed have to be altered when the hard-worked critics take that man in hand; but nobody is expected to sympathise with them, for if they don’t like being critics they can go and chop wood. The strongest advocates of the matinée system, however, will not, I presume, be bold enough to say that the verdict of a matinée audience on a new piece is of very much value. A matinée gathering is too much like a family party, and unless piece and performance be abominably bad nothing in the shape of condemnation is to be looked for. The manager who has ventured on the production of a novelty, of course brings up all his friends and relations; the author naturally follows suit; some of those engaged do ditto; well-known actors and actresses pass in “on their faces”; and the paying public is generally and chiefly represented by ladies who have come out for amusement, and are much too polite to kick up a row if they don’t get it. I have said thus much because I want to warn Thomas Thorne, the lessee of the Vaudeville, against placing too much dependence on the verdict of the large audience assembled within the establishment named on Monday afternoon to witness the first representation of Mr. Robert Buchanan’s new three-act “fantastic comedy,” bearing the strange title “That Doctor Cupid,” which has now pushed “Joseph’s Sweetheart” for a time out of the evening bill. Mr. Buchanan admits that he has taken the idea for the leading incident of his first act from Foote’s farce, “The Devil on Two Sticks,” but claims for the rest that it is entirely new and original. A good many among Monday’s audience were not disposed to admit the claim, for it soon became evident that Buchanan was attempting the Gilbertian trick, and that the disciple was not quite so clever at it as the master has proved himself many a time, many a time. Well, Foote was indebted to Le Sage—l don’t mean that very important person of the D. T. who so calls himself—and there is nothing new under the sun. Foote of the wooden leg, you may have read, got his imp out of a bottle in a doctor’s shop in Madrid, played the very devil with him—for he played the Devil himself—and, bringing him to London with a couple of young lovers set to work to poke fun at the medical profession in general, and at Sir William Brown, the head of it, in particular, and it is on record that he of the horns and hoofs was made to assert that most men were beholden to him and his colleagues for their superlative epithets and for the measure both of virtues and vices. For the profane then, like the profane now, were apt to say devilish rich or devilish poor, devilish ugly or devilish handsome, with a bigger D and a stronger but still correlative word when they wanted to speak of the extremes of heat and cold. Foote set the town in a roar with his “bottle imp”; Buchanan will hardly do the same with his. Let me say at once, though, that there is much fun in “That Doctor Cupid.” If you don’t enjoy it thoroughly and completely it will be because you will perceive, as I did, that the author has spun it out in a way that makes it very thin indeed, and because, under the strain of three acts, it is constantly in danger of breaking down. R. B. has not gone in for satire, but has indulged in sundry verbal jests that are very harmless and even puerile. He has called one of his characters Bridget in order to give another a chance to say there is a gulf between them and he can’t bridge it. He takes them all to Bath so that his mischievous Doctor may give off something about making a warm Bath for his protégés enemies. You will probably groan in spirit over this sort of thing. Buchanan is old enough to know better, but you will pardon him because of some really pleasant humour and the pretty conceits that are to be found in many passages of the comedy. Doctor Cupid is a lively old gentleman, who, in place of the wings and nothing else of his childhood, has put on Elizabethan costume, and who discharges his shafts from his mouth instead of from a bow. He is liberated from his bottle—his prison since the time of good Queen Bess—by a Cambridge student, named Harry Racket, who has got into disgrace with a wealthy old uncle because when he should have been improving his mind he has been drinking or gambling or playing practical jokes at the expense of his tutor, whom he has stripped of his garments and left shivering in his shirt in the college corridors. Harry has taken the bottle with a lot of curiosities foisted on him by the usurer who relieves his monetary necessities, and presumably charges him sixty per cent. The Doctor grows with amazing rapidity when he is set free, inquires after Queen Elizabeth, shakes off the cramp and the other pains that have come of sticking so long to the bottle, and then proclaims himself young Racket’s very obedient servant to command. Harry is most anxious that he shall not lose the pretty Kate Constant, who has gone off to Bath, and who seems likely to go off altogether with a mushroom swell called Lord Fungus; so he gets Doctor Cupid to spirit him away to the Somersetshire city, where he presently, with the Doctor passing as his tutor, makes his appearance at the Assembly Rooms; there the fun begins in real earnest. Through the agency of Doctor Cupid an epidemic of flirtation sets in. Cupid, however, being, as he puts it, out of practice, while enjoying himself sets everybody else by the ears, and blunders so terribly that Kate Constant throws over Harry and gives her smiles with her arm to my Lord Fungus. This so enrages Harry Racket that he throws over—literally—his larky companion, jumps on his chest, and endeavours to choke him. Doctor Cupid thereupon repents of his stupidity, and goes to work to undo the mischief he has done, so that in the end Harry gets back Kate’s love, and with it the forgiveness of his hot-headed and gouty old uncle. Mr. Thomas Thorne, as Dr. Cupid, went in to prove that he has not forgotten the lessons he practised in burlesque in the long ago. Mr. Frank Gillmore (who is a son of Emily Thorne) was very serious and very earnest as Harry Racket, and a really fine old English gentleman of the peppery sort was the Sir Timothy Racket of Mr. Fred Thorne. Perhaps the funniest thing in the whole show was the stuttering Charles Farlow—Harry’s friend—of Mr. Cyril Maude, who got the loudest laughter and the loudest applause. Miss Winifred Emery made some exquisite fooling out of the part of Kate Constant; but it is to be hoped she will not waste her abilities on this flimsy sort of work. Miss Dolores Drummond’s skill was capitally exercised in the character of Sir Timothy’s ugly and designing housekeeper, who means to marry him if she can. Miss Marion Lea charmed me as the young widow, Mrs. Bliss, who is the object of Charles Farlow’s affections; and Miss Fanny Robertson in her own clever way made prominent the part of Kate’s elderly and starchy aunt, who, under the influence of Doctor Cupid, skips and frisks like a young lamb. Messrs. F. Grove as Beau King of the Bath Assembly Rooms, Mr. Henry Pagden as the sixty per cent. usurer, Mr. Wheatman as Harry Racket’s Irish servant, and Mr. Scott-Buist as Lord Fungus, did not give room for even a little bit of hostile comment. Buchanan was called at the end of the performance, and, satisfied with the verdict pronounced, Thorne put the piece in the evening bill on Thursday. Now we must wait and see how long it will stop there. ___

The People (20 January, 1889 - p.4) Profound was the surprise felt by the Vaudeville audience on Monday afternoon when Mr. Tom Thorne burst upon their gaze as a middle-aged embodiment of Cupid, and, in the second act of Mr. Buchanan’s comedy, capered about in a style strongly reminiscent of his old burlesque days at the Strand. Mr. David James (in the stalls) must instinctively have allowed his mind to recur to those giddy paced times. Mr. Grossmith (up in a box) must have regarded Mr. Thorne with envy. What, I wonder, did Miss Harriett Jay, the author’s sister-in-law, report to him about the demeanour of the audience? (p.6) THE THEATRES. VAUDEVILLE. With a wise precaution which by frequent repetition has become the usage of his theatre, Mr. Thomas Thorne put the new comedy by Mr. Buchanan, designed to follow “Joseph’s Sweetheart” to preliminary trial at an afternoon performance on Monday last, when the reception of the piece justified its transference on Thursday to the evening bill of the Vaudeville. Whether “That Doctor Cupid”—for so the new production is called—will achieve such popularity as accounts for the phenomenal runs of “Sophia” and “Joseph’s Sweetheart,” by the same author, time alone can tell; the new piece being a distinct departure from the well established paths of comedy-drama across the fantastic dramatic borderland, where the actual merges in the supernatural. Foote’s quaint farce “The Devil on Two Sticks,” borrowed by him from Le Sage’s “Diable Boiteux” is the one acknowledged source of Mr. Buchanan’s inspiration for his latest stage production; but half-a-dozen other well known works might easily have suggested the initial idea, including “Faust,” “The Bottle Imp,” and the released genie of “The Arabian Nights.” This will be best shown by a recital of the plot of “That Doctor Cupid.” Charles Racket a wild young blood such as were found at Cambridge at the outset of the century, played out by debt and dissipation, in sheer wantonness of spirit dashes the contents of his college rooms into the fire. Among these bachelor curiosities is a sealed phial containing, apparently, a deil. But no sooner is the vessel broken by impact with the firegrate than amid the flare of lightning and the rattle of thunder there emerges from the chimney-place a spruce elderly gentleman, who announces himself as the love god, Cupid, grown old in his long enforced confinement. Here, minus the compact, we have a modern Faust and Mephisto, who go after the approved fashion of the older legend, upon their travels. Arrived at Bath the rheumatic elderly Cupid—now dubbed “Doctor,” as his tutor by young Racket, on their introduction at the Assembly Rooms—begin setting all the beaux and belles by the ears through the jealousy caused by the mischievous use of his amatory darts. First of all his companion is put at cross-purposes with his sweetheart Kate, who sentimentally suffers in this way for her avowed “love for a rake.” The further clash of engaged couples effected by this cynical Eros is seen displayed on its comical side in the amatory advances of his old maiden housekeeper to the surly and irascible son, Timothy Racket, and the jealousy of the stammering swain, Charles Farlow, wrought to half articulate frenzy by the flirtation of his fiancée with the young undergraduate, while his sweetheart, Kate, plays croquet with the hitherto detested Mr. Fungus. After scenes, involving such confusion of feeling as is here indicated at the Lovers Well, developing the generous and selfish tendencies of the characters generally, the perverse love god reversing the spell, acts as if he were a boy again by setting matter right in respect of the rightful allocation of both hearts and hands. “That Doctor Cupid,” like so many Criterion farces, is a capital vehicle for vivacious acting, which, fortunately, it received at the hands of the Vaudeville performers. Specially worthy of notice in an excellent all round cast was the Cupid by Mr. Thomas Thorne—quaint and frisky, with a spice of mischief in its sincerity of personal enjoyment; and in Miss Winifred Emery and Miss Marion Lea—a rising young actress—were capitally contrasted the half pathetic sentiment of the serious heroine with the high spirit of fun of her lighter-hearted companion. Mr. Cyril Maude, who on his merits has come rapidly to the front, displayed a fresh and welcome humour as the stuttering swain whose jealousy is intensified by its struggle for utterance at the tip of his tongue. Mr. Fred Thorne, though a trifle boisterous, stood out with characteristic prominence as the angry, cranky old uncle of the scapegrace Racket, whose wild recklessness was well expressed by Mr. Gillmore. Miss Dolores Drummond, as the amorous old maid, and Messrs. Buist, Wheatman, and Pagden in minor parts complete the satisfactory category of characters. As acted, Mr. Buchanan’s fantastic farce was diverting and never dull—the best diploma it can receive, as regards its power of attraction in the evening programme of the Vaudeville. ___

The Echo (23 January, 1889 - p.2) Mr. Robert Buchanan should dramatise his novel, “The Shadow of the Sword”; it is one of the finest works of English fiction of the age. His “Martyrdom of Madeleine” should also make a good modern drama. But perhaps Mr. Yates might object. So far, the Scottish bard’s original efforts—Fascination, The Blue Bells of Scotland, and his closer play, The Drama of Kings, have done as little for his reputation as his essay on the “Fleshly School of Poetry.” Per contra, adapting Smollett, Fielding, and Daudet has spelt success for him. Will That Doctor Cupid’s run establish him as an original dramatist? _____

|

|||

|

|

|

|

|

|