|

|

|

|

|

ROBERT WILLIAMS BUCHANAN (1841 - 1901)

|

|

|

|

THEATRE REVIEWS

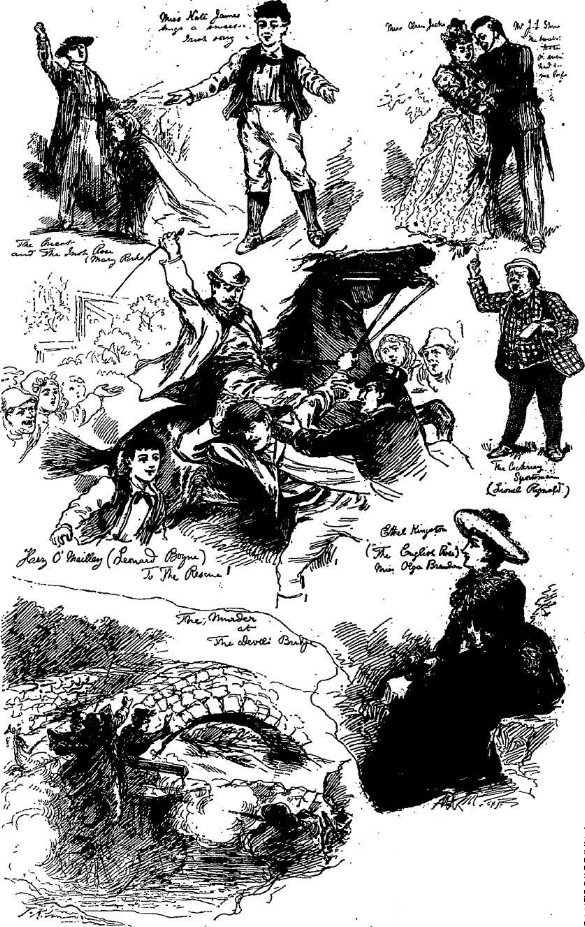

33. The English Rose (1890)

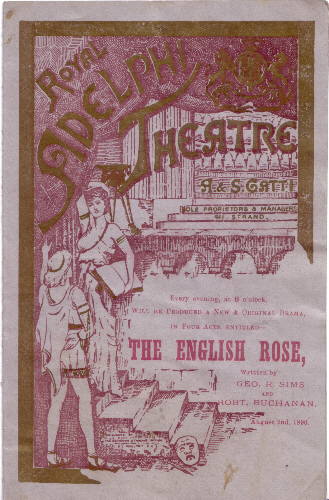

The English Rose

by Robert Buchanan and George R. Sims.

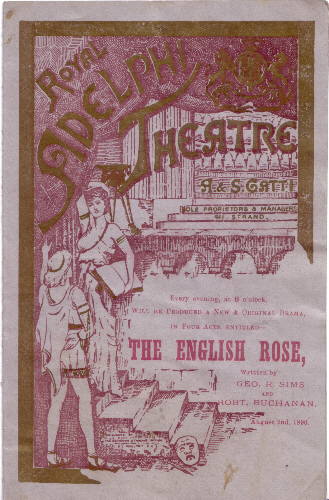

London: Adelphi Theatre. 2 August, 1890 to 2 May, 1891 (238th performance).

Boston: Boston Museum. 1 September, 1890.

Liverpool: Court Theatre. 29 September, 1890. First provincial performance.

New York: Proctor’s Theatre. 9 March, 1892.

Other performances:

London: Elephant and Castle Theatre. 18 July, 1898.

London: The Pavilion Theatre. 24 April, 1899.

A series of letters from John Coleman and Robert Buchanan appeared in The Era in August 1890, concerning the original source of The English Rose.

Film: The English Rose, directed by Fred Paul, 1920 (more information in the Robert Buchanan Filmography section).

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

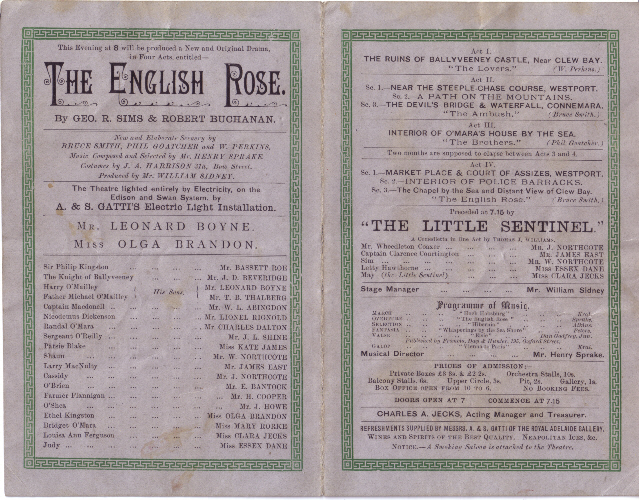

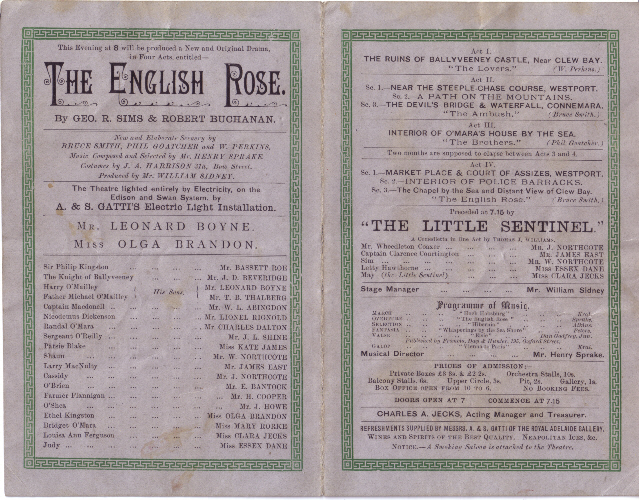

[Programme for The English Rose at the Adelphi Theatre, 2 August, 1890.

Click the pictures for larger image.]

The Era (1 March, 1890 - p.10)

MR G. R. SIMS and MR ROBERT BUCHANAN will be the joint authors of the new drama which is to follow London Day by Day at the Adelphi Theatre.

___

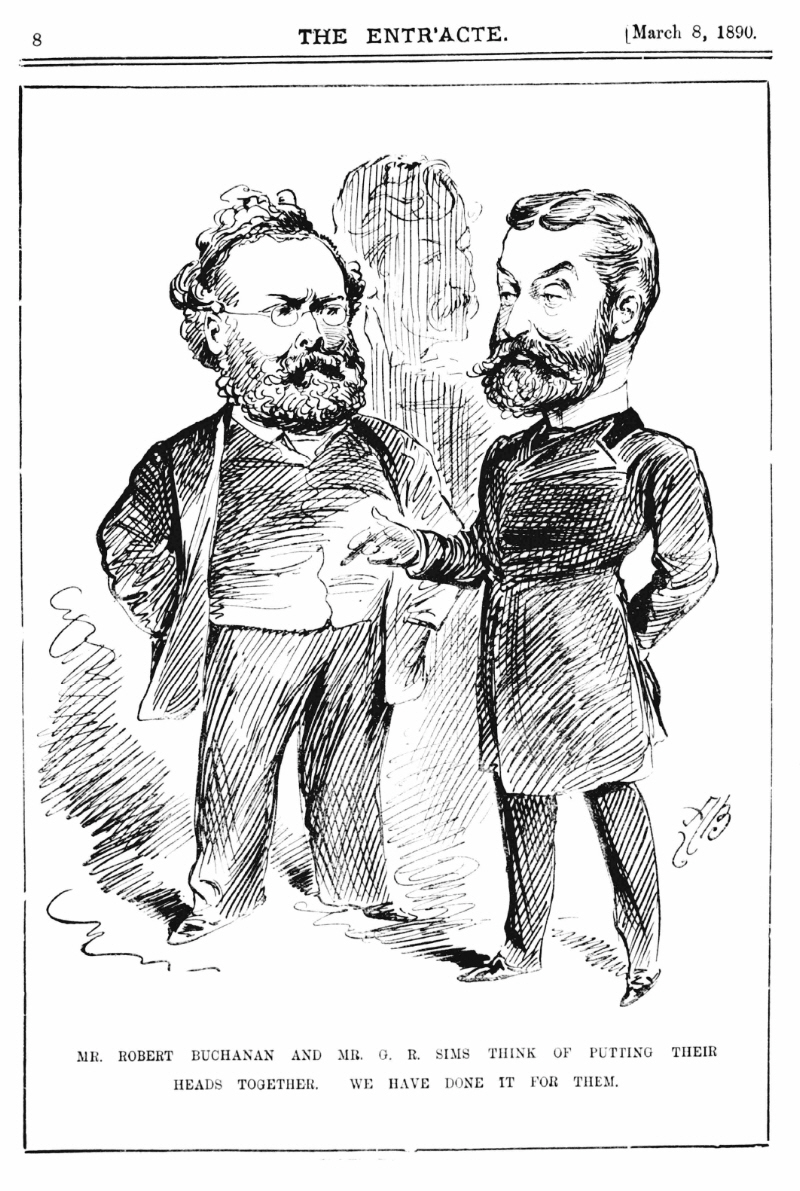

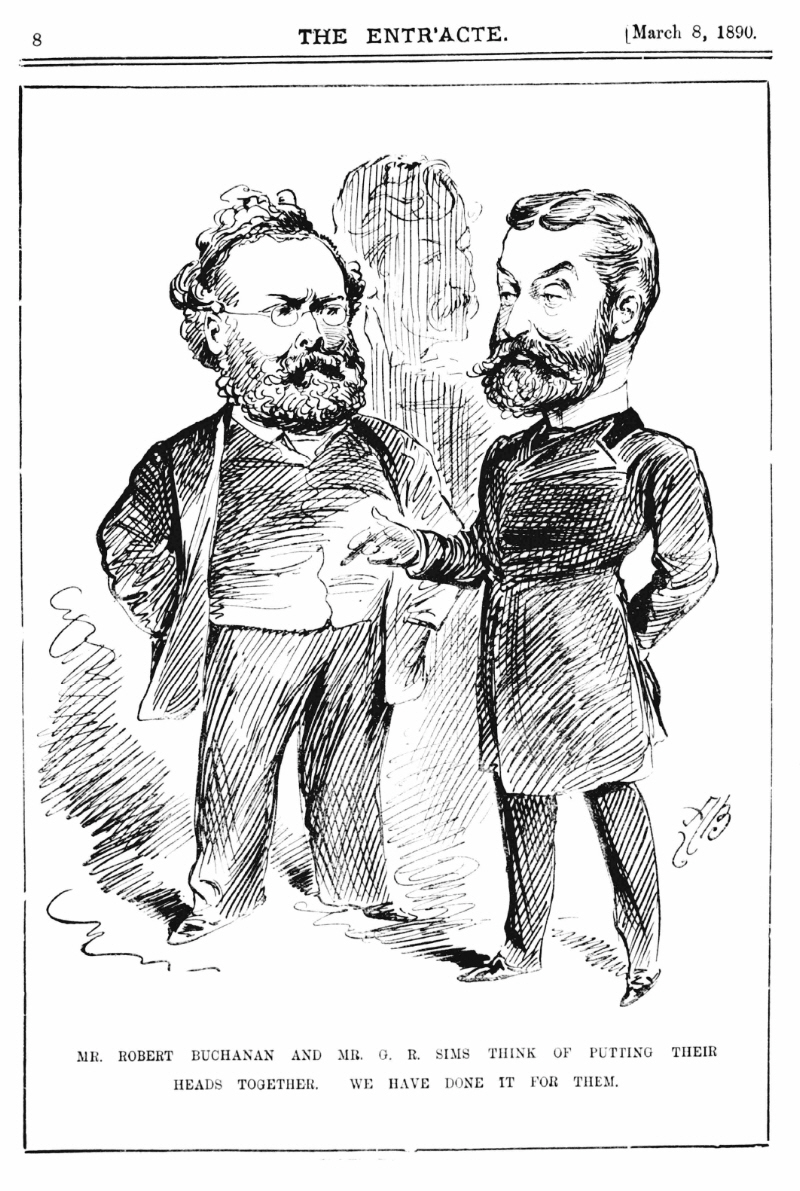

The Entr’acte (8 March, 1890 - p.8)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

The Referee (18 May, 1890 - p.3)

The new melodrama by G. R. Sims and Robert Buchanan at the Adelphi will be in four acts, and will deal with modern Irish life. Mr. Leonard Boyne, Miss Olga Brandon, and Mr. Charles Dalton are the newcomers. The drama will be produced on August 2, the Saturday before Bank Holiday.

___

The Stage (11 July, 1890 - p.9)

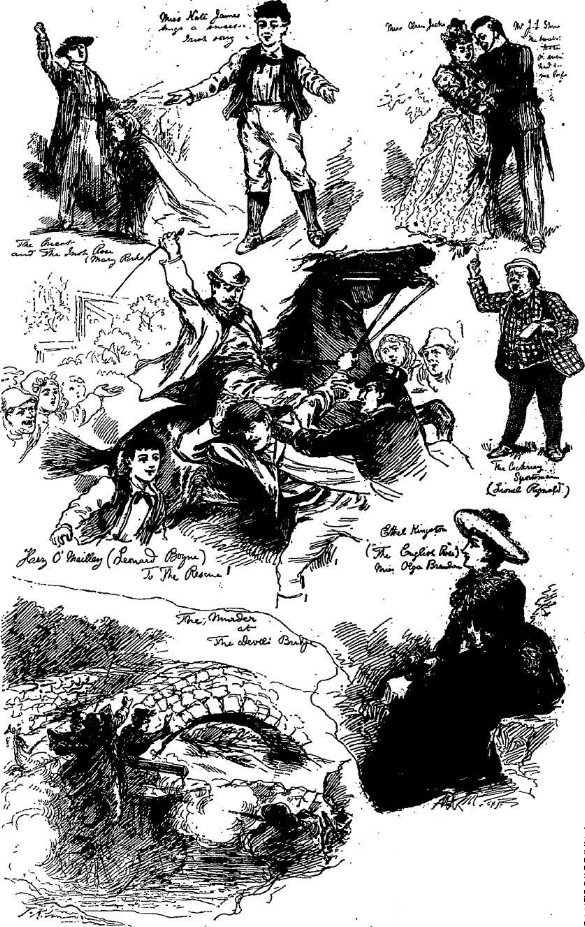

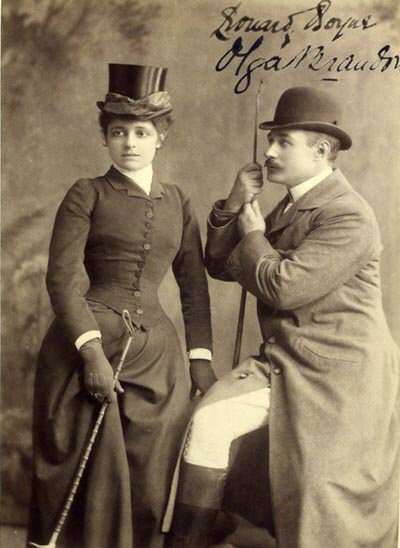

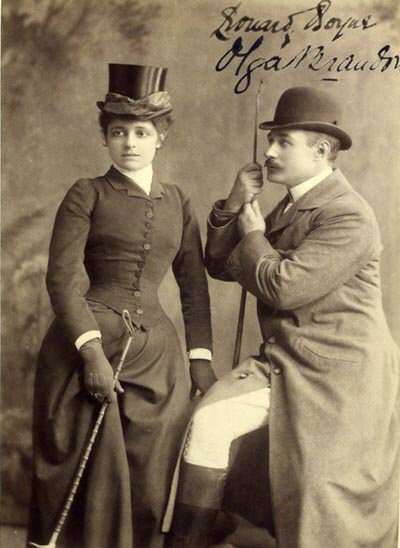

In speaking of Buchanan and Sims’s new Irish drama to be produced at the Adelphi on Saturday, August 2, “R. U. E.” in the Pall Mall Gazette says:—“The hero will be played by Mr. Leonard Boyne, who should be suited to perfection in a breezy Hibernian rôle; while Miss Olga Brandon, who will be compelled to give up her nightly fast at the Shaftesbury, will appear as the English heroine. Among the other artists who will join the Adelphi company for the new piece will be Mr. Bassett Roe, Mr. Charles Dalton, and Mr. Thalberg. Mr. Bassett Roe will be a gentlemanly specimen of the landlord class; Mr. Charles Dalton a rough son of the soil, a character conceived somewhat in the style of Danny Mann in The Colleen Bawn; and Mr. Thalberg—an actor to whom Mr. Buchanan has already entrusted such important parts as Lovelace in Clarissa and Eros in The Bride of Love—an ardent young priest, who has flown to the arms of the Church as a refuge from an unconquerable and hopeless passion. Mr. W. L. Abingdon will appear as the out-and-out villain of the drama, but Mr. J. D. Beveridge for once in a way will enact a fairly exemplary member of society. The lighter moments of the story will be in the hands of those well-tried Adelphi favourites, Messrs. J. L. Shine and Lionel Rignold, the former of whom should make much of the humours of a rollicking Irish policeman. Miss Mary Rorke, Miss Kate James, and Miss Clara Jecks will also have parts in a cast which, by reason of its strength, promises well for the success of the Brothers Gatti’s autumn venture.”

___

The Daily Telegraph (11 July, 1890 - p.3)

DRAMATIC AND MUSICAL.

In the new Irish drama by George R. Sims and Robert Buchanan, now in active rehearsal at the Adelphi—and due, if all be well, on Aug.2—the authors have been particularly careful to avoid all controversial political matter, and their aim is to tell a simple story of human life; but if there is any bias to be found in the new play it will be in generous sympathy for the Irish people. Of what value would be an Adelphi Irish drama without it? An attempt will be made by the authors to show the Irish priest as he really is. In one scene, bearing at the outset a strong resemblance to a passage in the Haymarket “Village Priest,” the earnest young pastor tells of the hopeless passion which made him devote his life to religion; but instead of avowing, with the French abbé, that this passion still possesses him, he describes his victory over it, and his consequent purification. The question thus alluded to is, however, only a side issue in the new drama, the real hero of which is a gay, light-hearted young Irishman, played by Mr. Leonard Boyne, who should understand the Irish character.

___

The Graphic (19 July, 1890)

In the new drama of Messrs. Sims and Buchanan, which is to be brought out at the ADELPHI, there is, it is said, a priest who will relate how a hopeless passion induced him to devote his life to religion. At present the latest example of this familiar stage figure is the Abbé Dubois at the Haymarket. The type seems to be traceable, through a now rather long succession, to Lamartine’s once popular Jocelyn.

___

The Daily Telegraph (25 July, 1890 - p.3)

It was originally proposed to call the new Adelphi play “The English Rose,” and it is not at all certain that this charming title will be discarded for one of a more sporting character. Already there are rumours of “priority of claim” in connection with the plot and incidents of the new Irish drama, but when in the history of the stage did not this occur? According to some disappointed and unplayed authors, “there is nothing new under the sun” except their own plots, but it is not at all likely that either Mr. George R. Sims or Mr. Robert Buchanan would affix their affidavits to the words “new and original” if this were not the case. At any rate, whatever existing work may be dimly suggested by the new drama, we may be quite certain that the treatment is fresh and unconventional. Saturday night, Aug. 2, is fixed for the new Adelphi play, and after that the season will be at an end, and the dramatic critics will be off for their holiday far away from the temptation of first nights or matinées.

___

The Penny Illustrated Paper (2 August, 1890 - p.3)

“The English Rose,” the new melodrama Mr. G. R. Sims and Mr. Robert Buchanan have written for Messrs. Gatti, is the first important novelty of the early autumn in London. It is due at the Adelphi to-night. A little bird has whispered to me that “The English Rose” is as sweet as its fragrant namesake, and that it is likely to bloom for many a night to come in the bright and comfortable and well-ventilated and coolly lit theatre which MM. Gatti manage so successfully, with Mr. Sidney as the able stage-director. This “English Rose” is a winsome English gentlewoman, resident in Ireland, who wins th heart of the Irish hero. Miss Olga Brandon is the “English Rose.” I’m told there’s a splendid character in an Irish priest. Plot is exciting and sympathetic. Trust those Past Masters in the Art of Love (theatrical love, of course), MM. Sims and Buchanan, to supply plenty of love-making of the right sort for Adelphi audiences, bedad! Rely upon plenty of strong acting on the part of Mr. Leonard Boyne (who should try to be as natural as he can), Miss Mary Rorke, and Mr. Beveridge; and depend upon it, Mr. J. L. Shine (half an Irishman by birth), Mr. Lionel Rignold, Miss Clara Jecks, Mr. James East, and Miss Kate James will supply an abundance of humour, and good humour.

___

Reynolds’s Newspaper (3 August, 1890)

ADELPHI THEATRE.

It goes without saying that a piece by two such masters of stage craft as Mr. G. R. Sims and Mr. Robert Buchanan would present a series of bright, animated, and effective pictures. “The English Rose,” produced at the Adelphi Theatre last night, is an Irish play, through, from its title, one would hardly suspect the fact. The authors have adopted the bold experiment of presenting a play of modern Irish life, which is told with a fidelity we miss in the Irish plays of Mr. Boucicault, without losing any of the picturesque characteristics of that author. The curtain opens on a scene representing the ruins of Ballyveeney Castle, near Clew Bay, on the West Coast of Ireland. The Knight of Ballyveeney has been dispossessed of his property, which has come into the hands of Sir Philip Kingston, an Englishman. His niece, Ethel Kingston—the “English Rose,” as she is called—is in love with Harry O’Mailley, a son of the Knight. Sir Philip Kingston’s land agent, one Captain Macdonell, is, of course, the villain of the piece. He grinds the tenants, while pretending to be their friend, falsely laying the blame upon the landlord. This man is also in love with the landlord’s niece. Prompted to make inquiries as to his agent’s accounts, the latter, who has been guilty of falsification and appropriation, incites some discontented tenantry to murder Sir Philip. Harry O’Mailley, hearing of the plot, rides from the racecourse, where he had won a steeplechase against the agent, to save his father’s dispossessor. He comes too late; the murder has just been accomplished. He struggles with one of the assassins, who escapes, leaving his gun in Philip’s hands. Miss Kingston, who was on the car when the murder was committed, returns, and discovers her lover in a situation which leads her to believe that he was guilty of the murder, of which she accuses him in the presence of witnesses, but, in a few moments, withdraws the accusation. In these incidents, as may well be imagined, there is ample scope for the Adelphi management to produce striking stage effects. And they make the most of them. The scenery is all that stage carpentry and painting can effect. The spot chosen for the murder represented an old bridge, beneath which a volume of water poured. The full moon illuminated the scene, and the Connemara mountains rose in the blue haze of the background. The murder itself is an exciting piece of stage business. An Irish jaunting car drives across the stage. Several shots are fired on both sides, and presently in comes thundering the belated rescuer. Harry O’Mailley is, of course, arrested and charged with the murder. The interest is here intensified by the fact that his brother, who is a priest, has received the confession of the real culprit, which the Church forbids him to reveal. We have here a repetition of the incident which has been used with such effect in “The Village Priest.” However, in the end, it all comes right. O’Mailley is found guilty of the murder, but he is rescued by the people. Meanwhile one of the accomplices of Captain Macdonell turns Queen’s evidence, and the real murderer confesses. The lovers are thus restored to one another amid general rejoicing, and the handcuffs are clapped on Macdonell. The last scene, representing a land and coast scene on the West Coast of Ireland, is one of surpassing beauty. Mr. Leonard Boyne, as Harry O’Mailley, acted with great spirit. His bearing was entirely what one would expect from an Irish gentleman of the Celtic strain—full of animal spirits, good humour; hot in taking offence, honourable in reparation. He had a most difficult task, as he was on the stage nearly the whole time, and his physical exertions in managing a high-spirited steed were by no means inconsiderable. Miss Olga Brandon, as the “English Rose,” acted with grace and carefulness, but the part did not allow much scope for the exhibition of her undoubted histrionic abilities. Miss Mary Rorke and Miss Clara Jecks were similarly provided with parts which gave them little opportunity to shine. Nothing better in the way of low comedy acting has been seen recently than Mr. Lionel Rignold’s Nicodemus Dickenson, a London betting man, who has been obliged to seek refuge in Ireland for a forgery. Mr. J. L. Shine’s Sergeant O’Reilly, of the Royal Irish Constabulary, was also an extremely good piece of comic acting. Mr. J. D. Beveridge’s Knight of Ballyveeney gave a picture of dignified, yet hearty and refreshing manhood, much appreciated by the audience. Indeed the front of the house was vociferously appreciative throughout. The actors were called before the curtain at the end of each act, and, when the curtain fell, Messrs. Sims and Buchanan, in response to repeated calls, bowed their acknowledgments from the stage.

___

Lloyd’s Weekly Newspaper (3 August, 1890)

LAST NIGHT’S THEATRICALS.

_____

ADELPHI.

The new piece, The English Rose, possesses all the essentials of an Adelphi drama. Steering clear of debateable matter, Messrs. Sims and Buchanan have succeeded in constructing a story which sufficiently bears the impress of reality as concerns the disturbed state of Ireland a few years ago. and at the same time is thoroughly vigorous in tone. There is abundant variety, too, in the characterisation, and in the romantic nature of the incidents. No wonder, then, that early in the action the audience showed that they were disposed to give a cordial greeting to the Messrs. Gatti’s latest venture. Harry O’Mailley, a son of an impoverished Irish gentleman, the knight of Ballyveeney, is in love with Ethel Kingston, the ward of Sir Philip Kingston, the English owner of the estates formerly owned by the knight. Ethel is also sought by Captain Macdonell, the universally hated agent of Sir Philip. Macdonell, besides acting the part of the “false steward,” is the instigator of threatening letters to Sir Philip, his idea being that he, by playing upon the latter’s fears, may obtain a freer hand to oppress the peasantry. The foundation of the piece is virtually the hatred of Macdonell towards the gallant and honest Harry O’Mailley, as good a sample of the frank, insinuating, young stage Irishman as ever was drawn, even by Boucicault.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

The humour of the piece, which is a highly-successful element of the performance, is also in spirit reminiscent of the typical Irish drama of The Colleen Bawn, Arrah-na-Pogue, and The Shaughraun pattern, which is equivalent to very high praise. The comic characters in the present case are a Cockney horse-dealer (embodied with graphic force by Mr. Lionel Rignold), a serjeant of Irish constabulary (Mr. J. L. Shine), and an English servant girl (represented by Miss Clara Jecks with her wonted brightness and engaging piquancy). Macdonell, ordered to produce his accounts, induces a discontented young farmer to assassinate Sir Philip as he is returning from a race. This race, by the way, is won by Harry, after a vain attempt has been made to hocuss his horse, and being struck by Sir Philip, and subsequently found bending over the latter’s body after the assassins have escaped, the young Irishman is accused of the crime. Harry is found guilty of the murder, but on being taken from the prison is rescued by the mob. Macdonell’s schemes are at length exposed by one of his associates turning Queen’s evidence, and the real murderer also confesses. The intentions of the authors appear to be fully carried out by the performers. The selection of Miss Olga Brandon for the heroine was judicious, inasmuch as Ethel Kingston is a part requiring graceful presence together with considerable feeling. A scene demanding forcible expression is that in which the girl, after accusing her lover of the murder, attempts to withdraw the charge, and here Miss Olga Brandon notably acted with admirable decision. Miss Mary Rorke effectively indicates the secret love of the murderer’s sister for Harry O'Mailley. The hero is played with refreshing vigour and earnestness by Mr. Leonard Boyne; the old knight is sturdily represented by Mr. Beveridge, Miss Kate James acts with sprightliness as an Irish stable-boy; Mr. T. B. Thalberg is dignified as the clerical brother of Harry; Mr. Bassett Roe is Sir Philip; Mr. W. L. Abingdon has a familiar task in delineating the villainy of Macdonell, and Mr. Charles Dalton powerfully depicts the brooding nature of O’Hara. There is a crowd of peasantry who seem to thoroughly enter into the excitement of the leading situations, and a series of picturesque scenes of lake and mountain have been provided. Specially excellent in arrangement is the view of “The Devil’s Bridge,” crossing a torrent of real water, where the murder takes place. When the curtain fell at half-past 11 there were enthusiastic calls for the principals, then for the two authors (who appeared), then for the managers (to which Mr. S. Gatti responded), and then for Mr. Sydney (the stage manager), and Mr. Lionel Rignold. The success of The English Rose was of the most decisive description.

___

The Referee (3 August, 1890 - p.3)

ADELPHI—SATURDAY NIGHT.

When two such distinguished playwrights as Messrs. G. R. Sims and Robert Buchanan agree to collaborate, the result of their joint endeavours should be a forcible exemplification of the motto that union is strength. Expectations have been fully justified in the case of “The English Rose,” for a more decisive Adelphi success has not been chronicled for a long time. When the curtain rises we see the very picturesque ruins of Ballyveeney Castle in Ireland, a portion of which has been roofed in to accommodate their impoverished owner, who, thanks to excessive generosity rather than ordinary improvidence, is now in the power of Sir Philip Kingston, an English baronet, and his rascally agent, Captain Macdonell. The Knight of Ballyveeney has two sons, Michael O’Mailley, who has become a priest, and Harry, who knows more about horses than Masses. Harry has fallen desperately in love with Ethel, Sir Philip’s niece, and she favours him, greatly to the disgust of the proud English baronet and the villainous agent, against whom some ugly testimony is growing, thanks to the enterprise of Sergeant O’Reilly, of the Constabulary. In the second act Macdonell, finding that the toils are closing round him, urges Randal O’Mara, an evicted tenant and an ill-conditioned fellow, to murder Sir Philip as he passes the Devil’s Bridge, Connemara, on his return from a steeplechase. A half-witted youth named Patsie Blake overhears the conspiracy, and tells Harry O’Mailley, who has just piloted the favourite to victory. Remounting the horse, Harry gallops off, after administering condign chastisement to Macdonell. Mr. Leonard Boyne’s clever feat of horsemanship at this point elicited thunders of applause. The next episode will be readily anticipated. The murder is committed. Harry arrives just too late to prevent it, but wrests O’Mara’s weapon from him, and is of course regarded as the culprit, his sweetheart, Ethel, being the first to accuse him. So far the orthodox lines of Adelphi melodrama have been closely followed, but an element of freshness is introduced in the third act. O’Mara, who has been wounded in the fray, thinks he is dying, and confesses his crime to Father Michael. Harry is arrested, and, of course, his brother could save him, but his lips are sealed. At this point occurs a very original episode. The old Knight of Ballyveeney is about to depart to America in order to claim the property of a dead kinsman, and as he has not yet heard of the crime of which his boy is accused, everybody, the Constabulary included, agrees to spare his feelings, and a parting glass is shared all round. To-night there was a general nervousness and hesitancy in this scene, but when all are sure of their parts it ought to create an electrical sensation throughout the house. In the first scene of the last act we are let down rather severely. Harry is tried and condemned, but there is a rescue, and without a blow being struck the soldiers and police permit their prisoner to be carried off in triumph. The final scene, however, makes amends for this bit of conventionality. Harry seeks sanctuary in his brother’s “chapel by the sea,” a beautifully painted set, and the real murderer turns up and makes a dying confession. Macdonell reaps the wages of sin, and at any rate Harry and Ethel are made happy, though other deserving characters learn to suffer and be strong. “The English Rose” is unquestionably an advance on ordinary Adelphi melodrama, and as the best scenes were those which seemed to interest to-night’s auditory most sincerely the ambition of the authors is fairly justified. We have already said that the leading artists were not quite equal to the demands made upon them, and their uncertainty was, perhaps, excusable. But they must pull themselves together, and remember that, at the Adelphi of all theatres, under-acting is a mortal sin. Among those who did not offend were Mr. Leonard Boyne, who showed himself to much advantage, and dropped his mannerism, as the falsely accused Harry O’Mailley; Mr. Beveridge as his father, a real old Irish gentleman; and Mr. Charles Dalton, who impersonated the wretched O’Mara with force and picturesqueness. Miss Mary Rorke was earnest and pathetic as a girl who has been disappointed in love, Miss Kate James was natural as the semi-idiot Patsie Blake, and Mr. W. L. Abingdon did well in the ungrateful part of the villain Captain Macdonell. Mr. Bassett Roe as the English baronet, Mr. T. B. Thalberg as the cruelly tried priest, and Miss Olga Brandon in the titular part, will no doubt let themselves go when they are accustomed to their parts. To-night they were all rather tame. Mr. J. L. Shine and Miss Clara Jecks did admirably in comic parts, which happily were never permitted to become too prominent. The play was received with remarkable favour, and after everybody had been called the audience seemed loth to retire. “The English Rose” will settle down into a lasting success; of that there is no doubt whatever.

___

The Times (4 August, 1890 - p.10)

ADELPHI THEATRE.

The English playgoer has never taken a very matter-of-fact view of Ireland. He has been accustomed to think of it as a land of kneebreeches and brimless hats, sprigs of shillelagh, wakes, jigs, shebeens, and jaunting cars, with a population of black-eyed and short-skirted colleens, “bhoys” who are always “spoiling for a fight,” shovel-hatted priests, familiarly addressed as “your riverince,” and soldiers wearing the uniform of the Georges. If only for their courage in breaking with a worn-out convention, Messrs. G. R. Sims and Robert Buchanan deserve the thanks of the public in connexion with their new Irish play, paradoxically called The English Rose, which was given at the Adelphi on Saturday night. They have brought the Ireland of the stage up to date. They have swept away the comic opera personnel which has hitherto represented the Irish character. Theirs is not the Ireland of Mr. Boucicault or Charles Lever, but that of the daily newspapers or the Parnell Commission—the Ireland of judicial rents, threatening letters, police protection, moonlight outrage, and murder, side by side with a fund of law-abiding sentiment and a fair sprinkling of the heroic virtues. It may be thought that these are dangerous elements to juggle with in a popular entertainment. So they are; but the authors have taken care to hold the scale so evenly between all parties, to be so unbiased in their views, so unpolitical, in a word, that The English Rose can be applauded by Unionists and Home Rulers alike, if indeed under the spell of a strongly dramatic theme all political partisanship is not forgotten.

Messrs. Sims and Buchanan’s story starts with the advent into the wilds of Connemara of an English landlord, Sir Philip Kingston, and his pretty niece, Ethel Kingston, known as “the English rose.” Sir Philip is a just and honourable man, who has bought the land in open market. Unfortunately, he has taken it from the popular Knight of Ballyreeny, and his chivalrous son, Harry O’Mailley, ruined Irish gentry, and this constitutes a sentimental grievance against the newcomer. But the hardship undesignedly inflicted in this way by Sir Philip is more than repaired by his niece, who falls head over ears in love with Master Harry, the young squire. There are, of course, thriftless tenants, who think Sir Philip’s exactions hard, and outrage is darkly hinted at. Again, however, the compensating element is introduced; the tenants, left to themselves, would be honest enough to let their landlord go scatheless, but their evil passions are stirred up by the agent, one Macdonnell, whose books are wrong, and who is anxious that Sir Philip, his employer, should be murdered before the defalcations come to light. Another motive operates with Macdonnell. He is himself in love with “the English rose,” and O’Mailley is therefore his hated because successful rival. Now, O’Mailley has had a personal altercation with Sir Philip, and, in the event of the latter being “removed,” a suspicion of guilt will inevitably fall upon the young squire. So if murder is planned by the tenants against their landlord it is really the work of the wicked agent, who has personal rather than agrarian ends to serve. The spectator is consequently free to sympathize either with the landlord or the tenant party, or both; the Irish difficulty in the hands of Messrs. Sims and Buchanan being reduced to the proportions of a mere misunderstanding.

The piece is a notable achievement. It has quite a special and realistic interest for the Adelphi public, after the romantic nonsense which has hitherto passed as Irish drama, while in purely emotional and sensational elements it exhibits no falling away from the accepted standard. In truth, the authors have not diverged as widely from the beaten track of melodrama as would at first sight appear. The great scene of the second act, upon which the action hinges—namely, the murder of Sir Philip Kingston—is at once a typical Irish outrage and a melodramatic situation of approved effectiveness, with all the customary moral issues depending upon it. The dark deed is done at a spot called the Devil’s Bridge, one of the most picturesque scenes ever presented on the Adelphi stage. Sir Philip is driving home on his car—a genuine importation from Dublin. At the Devil’s Bridge the assassins, instigated by Macdonnell, lie in wait for him. The car with its occupant is being driven across the stage when bang! bang! go the rifles of the masked moonlighters. Sir Philip leaps from the car, fires his revolver at his assailants, and sinks upon the ground mortally wounded. Just then Harry O’Mailly, who has had wind of the conspiracy, and who has galloped after Sir Philip with the view of saving his life, appears upon the scene; he has a short but unavailing scuffle with one of the murderers, from whom he wrests a smoking rifle, and a minute afterwards he is discovered—by Macdonnell—with the accusing weapon in his hand, and denounced as the author of the crime. Nothing could be truer to melodramatic tradition; the situation is one that appeals to every habitué of the Adelphi. There is no need to pursue the story in detail. Harry O’Mailly is arrested in the third act. In the fourth he is tried on the charge of murder and condemned, the spectator obtaining only an exterior view of the court-house; he is rescued, however, from the soldiers and constabulary by a generous-hearted mob, who, despite the verdict, believe in his innocence, and after an exciting chase he is brought to bay in a chapel where he has sought sanctuary. Here, of course, his troubles end, for by this time one or two accomplices in the murder have confessed, and as the curtain falls it is the villanous Macdonnell who is taken prisoner.

More interesting than the solution given to this familiar dramatic problem is the colouring of the story, where, indeed, the art of the authors and of their interpreters is seen at its best. Mr. Leonard Boyne as O’Mailly is a valiant and chivalrous hero, whom it is refreshing to behold; he is just a little too free from guile, perhaps, but the Adelphi public like their virtue, equally with their vice, to be drawn with no uncertain hand. And for this work Mr. Boyne has no superior. His accents, besides being indubitably Irish, have the true ring of passion, and the evil designs which thwart his amorous intent, even temporarily, assume, ipso facto, a double-dyed aspect. Not that Mr. Abingdon, as the representative of Macdonnell, is at all lacking in detestable characteristics. The able-bodied villany of this actor has for one or two seasons past commended itself to Adelphi audiences, and it has seldom had better opportunities of displaying itself than in the present instance, where hero and villain are enabled to play into each other’s hands with the skill of an accomplished whist-party. For the part of “the English rose,” whose alliance with the shamrock, in the person of Mr. Boyne, is probably intended to typify the Union, the management have engaged Miss Olga Brandon, a young actress whose gifts of sympathetic and tender expression are of a very high order. Like Mr. Boyne, Miss Brandon makes her first appearance at this theatre in the present play, which for that reason alone establishes a claim to the gratitude of the Adelphi public. To the character of Miss Kingston an agreeable contrast is presented by the Bridget O’Mara of Miss Mary Rorke. Another new-comer is Mr. Bassett Roe, who is cast for the part of Sir Philip Kingston, and who invests it with a manliness and a dignity of the greatest value to the author’s dramatic scheme. The rest of the cast is extremely satisfactory. Half a dozen picturesque exteriors are traversed by the action, one of the prettiest of which is a little chapel by the sea, where the drama finds it dénouement.

___

The Pall Mall Gazette (4 August, 1890)

The Theatres.

“THE ENGLISH ROSE” AT THE ADELPHI.

PERHAPS at some period of the dim and distant future there will arise a new order of Adelphi playgoers— an audience which will refuse to be contented with the cut-and-dried melodramatic conventionalities loved and honoured by our sires and grandsires. Maybe—though the suggestion may sound somewhat rash—a more exacting generation than ourselves may ask to see upon the boards of the most famous of our Strand theatres a play cast in an original, or, at any rate, a slightly novel mould. All this, and more, the coming ages may bring forth. But the day is not yet. The denizens of the brothers Gatti’s vast gallery and enormous pit still cling, with limpet-like tenacity, to the old ideas and the time-honoured traditions, while the genius of the place seems to hover perpetually among the rafters of the theatre, and forbid as sacrilegious any rash deviation from the well-worn paths. How, then, can we blame Mr. George R. Sims and Mr. Robert Buchanan for having refrained from offering to their patrons any untested theatrical pabulum, and merely treated them to the old bill of fare with an Irish dressing? Doubtless the brains of these two clever dramatists are bubbling over with original notions enough for twenty Adelphi plays; but they have resisted the temptation to tread upon dangerous ground, and have come forward with a melodrama which is, if anything, rather more conventional than usual. Who shall say that they have done wrong? Certainly not the typical audience which thronged the theatre on Saturday night and cheered the new piece and all concerned in its production to the echo. Once more Virtue clasping its beloved to its bosom and Villainy wearing handcuffs on its wrists and a scowl on its face have proved as great “catches” as ever. Never mind if the authors have made their good folk mainly Irish and their evil characters mostly English. The thread of interest and the “one touch of human nature” are the principal essentials after all, and these we get in full measure. One would have wished, perhaps, to see a little more made of the third act in the dramatists’ scheme. They clearly intended to rely for their big effect here upon the terrible dilemma in which they have plunged the priest-brother of their hero. But, although the moral deduced is a better one than that of the Haymarket play, the situation of necessity recalls the confessional episode in “A Village Priest,” and it consequently loses a good deal of its force. Taking “The English Rose” as a whole, however, it is impossible to doubt that it promises great things at the Adelphi, for it is a sound, wholesome, and straightforward work, most admirably acted. If there was any meaning in the enthusiastic applause vouchsafed by Saturday night’s audience, the play should run for months to come.

The course of the plot can be indicated in a very few words. Sir Philip Kingston, an English baronet, has stepped into the estates of the impoverished Knight of Ballyveeney, and has at once made himself unpopular by his oppression of his tenantry. In this impolitic conduct he has been aided and abetted by his unscrupulous agent, one Captain Macdonell, who is particularly anxious to crush the Knight and his son Harry O’Mailley. Not only do these two honest Irishmen suspect Macdonell of financial malpractices, but young Harry has also won the heart of Sir Philip’s niece Ethel, an heiress, whom the agent has determined to wed himself. Driven to his last extremity, Macdonell plans the murder of his employer by a gang of Moonlighters, who finally shoot the baronet dead just at the moment that Harry rides up to the rescue. Hard words have been heard to pass between the murdered man and O’Mailley, and so Ethel’s lover, taken apparently red- handed, is denounced as the assassin in the familiar fashion that we know so well. After sundry vicissitudes, Harry is tried, convicted and rescued from the hands of the constabulary by his friends shortly before the dying confession of the real murderer renders him a free man and re-unites him to his sweetheart.

Altogether admirable is Mr. Leonard Boyne as the young Irish hero of the drama. Never has he played with more truth, sincerity, and, we may add, pluck, for his equestrian exit in the second act is seemingly one of the most daring pieces of “business” seen on the modern stage. Miss Olga Brandon gives promise of doing full justice to the rôle of Ethel Kingston when she has recovered the full use of her voice; while the acting of Miss Mary Rorke, as the disappointed Bridge O’Mara, shows much charm and pathos. Mr. J. D. Beveridge’s portrait of the hale old Knight of Ballyveeney, Mr. W. L. Abingdon’s polished conception of the villainous Captain Macdonell, and Mr. Bassett Roe’s neat rendering of the somewhat thankless part of the English baronet could hardly be improved upon; while Mr. Charles Dalton, an actor from whom we may expect much in the future, plays the very effective rôle of a drink-sodden ne’er-do-weel with striking vigour and firmness. As the young priest, Father Michael O’Mailley, Mr T. B. Thalberg shows more genuine earnestness than he has yet done upon the London stage; his appearance and manner, though, are perhaps needlessly ascetic. The comedy scenes give Mr. J. L. Shine an opportunity of appearing as a most diverting Sergeant of Constabulary, whose sympathies are all with his prisoners; while Mr. Lionel Rignold, who plays a car-driver hailing originally from Whitechapel, causes much laughter by his cockney comments on his own misdeeds. Miss Clara Jecks also does as excellent service as ever, nor should Miss Kate James’s sketch of a ragged but good-hearted little urchin be passed over without a word of hearty praise. The mounting of “The English Rose!” is as effective and elaborate as usual at the Adelphi, the “Ruins of Ballyveeny Castle,” the “Devil’s Bridge and Waterfall,” and the “Chapel by the Sea,” being exceptionally beautiful stage pictures.

___

The Daily News (4 August, 1890)

THE DRAMA.

_____

ADELPHI THEATRE.

The playgoer knows exactly what to expect at the Adelphi, and “The English Rose,” which was produced on Saturday night at this theatre, is another piece of the particular kind which may be defined in two words as Adelphi drama. In the authorship of the new play, Mr. George R. Sims, who has made the Adelphi audience his special study, is associated for a change with Mr. Robert Buchanan, and Mr. Buchanan, who is practised in every branch of dramatic composition, has so well adapted his style to the established forms of Adelphi drama that “The English Rose” will disappoint none but those who looked for something astonishing as the result of the new partnership. It is an Irish piece; that is to say, the scene is laid in Ireland, for although the personages of the play for the most part affect a brogue in speaking, and appeal pretty constantly to the whisky bottle, there is an unmistakable cockney humour pervading the work. The hero is the typical, loveable, wild young Irishman, who is common, if not in Connemara, at least in fiction, and if the part was not made for Mr. Leonard Boyne, Mr. Boyne might have been made for the part. He plays Harry O’Mailley in an airy, romantic style, which is in striking contrast with the more subdued manner of the heroine, as represented by Miss Olga Brandon, who has just stepped out of comedy into melodrama. Allowance must be made for the actress, for she was suffering on Saturday night from a sore throat; still the character of Ethel Kingston, “the English rose,” is obviously one that is better suited to Miss Mary Rorke, who is indifferently cast for the aimless part of a love- lorn peasant girl. It is rather late in the play that the gallant hero’s troubles begin, for everything goes very well with him till the third act, when he is arrested on a charge of murdering Ethel Kingston’s guardian, who is shot, before the very eyes of the audience, as he is driving across the Devil’s Bridge on a car. As a matter of course, O’Mailley is not guilty of the murder of Sir Philip Kingston, which is actually committed by one O’Mara at the instigation of Sir Philip’s own dishonest agent, who thinks to evade the examination of his accounts by the “removal” of his employer. Mr. Abingdon, who is experienced in this sort of villainy, makes a callous scoundrel of the agent. When O’Mailley appears on the stage, mounted on the mettled horse with which he has won the race, he first hears of the plot to murder Sir Philip Kingston, and the scene that was the great success of the evening is reached when he mounts his horse again, and rides off in fine style to overtake the attacking party. He arrives just a second too late, and in a struggle with O’Mara the wretch escapes, and O’Mailley is left there to be arrested with the murderer’s gun in his hand. Upon this evidence, which is insufficient, perhaps, to satisfy the lawyers, O’Mailley is condemned to death, and no questions are asked, not even in the House of Commons. To add to the anguish of the situation his brother, who is a priest, has received the murderer’s confession; but this priest, unlike the “village priest” of the Haymarket Theatre, does not betray his trust. However, it is not a question of ethics, but solely a question of a sensational position, with the authors of “The English Rose”; and, though his brother dare not save him, O’Mailley is rescued by the mob as he is being brought from the Court under guard. This scene went tamely at the first representation, and the soldiery and police should be advised to put a little more animation into the affair if they do not wish to convey the false impression that they are party to the rescue, for there was not a man among them who raised a hand when the mob made a rush for the prisoner. After this, it is but the work of a few moments to establish the innocence of Harry O’Mailley, and to utterly confound the wicked steward, who is handcuffed at the very last moment by a ubiquitous constabulary officer, played by Mr. J. L. Shine. Mr. Shine and Mr. Lionel Rignold have the best of the fun of the piece between them, one as a gay young police officer—with song, as the old playbills put it—and the other as a comic villain from the East-end of London, who turns his direst distresses to mirth. The comedy would be incomplete, however, without a sweetheart for the sergeant, and to this part Miss Clara Jecks has a kind of prescriptive right.

___

The Morning Post (4 August, 1890 - p. 3)

ADELPHI THEATRE.

_____

“The English Rose,” by Messrs. G. R. Sims and Robert Buchanan, produced last Saturday night with complete success, is the best Irish drama seen on the Adelphi stage since Mr. Boucicault’s popular pieces were played there. “The English Rose” has the same humour and pathos, the same contrasts of character, the same brightness of dialogue, combined with equally exciting sensational incidents. The story is an interesting one, and told in an effective and vigorous manner; in fact, Messrs. Sims and Buchanan have produced exactly the kind of drama to please Adelphi audiences, and the hearty cheers at the fall of the curtain, when the authors, the principal performers, Mr. S. Gatti, and the stage manager appeared at the footlights, gave promise of a long and brilliant career for “The English Rose.” The opening scene of the drama is near Clew Bay, where the Knight of Ballyveeney resides in the ruins of his old castle, his lands having passed to a wealthy Englishman, Sir Philip Kingston, whose niece, Ethel, is beloved by the knight’s son, Harry O’Mailley. Sir Philip’s agent, Captain Macdonell, a man who has done much to make the wealthy Englishman unpopular, also admires Ethel, and hates his rival with an intensity increased by the fact that Harry has a horse which is likely to win a steeplechase that is about to take place. Meanwhile, Sir Philip, having discovered his niece’s love for the impoverished Irish hero, sternly forbids their meeting, with the result that a quarrel ensues, and Sir Philip strikes the young man. The agent, who has been called to account by his employer, secretly tempts a vindictive, drunken fellow, Randal O’Mara, an evicted tenant, to murder the Englishman. Harry O’Mailley, just after winning the steeplechase, learns of the danger of Ethel and her uncle, and, mounting his horse, gallops over the mountains to their rescue, but too late. He is accused by the agent of having committed the deed in revenge for the insults he has received from Sir Philip. Meanwhile, Father O’Mailley, Harry’s brother, has learned through the confessional who is the murderer, but as a priest cannot reveal the secret. The consequence is that Harry is found guilty, but is rescued by the mob as he is being conveyed to prison. While he is flying from justice one of the men in the agent’s pay turns Queen’s evidence, and, to make the hero’s innocence still clearer, the murderer confesses his crime. This is but an outline of a story which kept the audience keenly interested during the four acts. The scenes and incidents are illustrated with charming stage landscapes and marine views, and the acting was just what the acting of an Adelphi drama should be—vigorous, pathetic, and humorous. Mr. Leonard Boyne was as good a representative of the gallant young Irishman as could be imagined. In love, sport, or danger, he was always the ideal of an Irish hero, and the scene in which he mounts his horse after the steeplechase, and dashes through the angry crowd was admirably managed, and was rewarded with deafening applause. Mr. J. D. Beveridge as the genial Knight of Ballyveeney, Mr. Bassett Roe as Sir Philip, and Mr. Thalberg as the gentle priest, did ample justice to their respective characters. Mr. Abingdon played the rascally agent effectively, and some highly-spiced cockney drollery by Mr. Lionel Rignold evoked the merriment of the audience. Mr. J. L. Shine as a lively Irish constable was also amusing. Miss Olga Brandon as the heroine gave the fullest importance to her principal scenes, and Miss Mary Rorke was extremely pleasing in a simple, pathetic character. Miss Clara Jecks lent gaiety to the scenes in which she appeared, and Miss Kate James as a wild Irish boy, Patsie Blake, acted with effect. Other characters were well played, and there was not a hitch of any kind. All that could be suggested in the way of improvement is that the earlier acts should be played with greater rapidity. The sensational scenes have never been surpassed, even at this favourite temple of melodrama. “The English Rose” will probably bloom until roses come again, for there was not a dissentient voice in the chorus of approval that accompanied the fall of the curtain.

___

The Scotsman (4 August, 1890 - p. 7)

LONDON THEATRICALS

LONDON, Saturday Night.

THIS has been a busy day for the dramatic critics. This afternoon they were summoned to the Globe Theatre to witness the first performance of a new play by Mr Pierre Leclercq. This evening they have been present at the production of a new melodrama at the Adelphi—”The English Rose”—by Messrs G. R. Sims and Robert Buchanan. The former work proved very dreary, and though not pointedly condemned, was a virtual failure. “The English Rose,” on the other hand, is a great popular success. It may not have quite the staying power of some of its predecessors—even of those by less distinguished “hands.” It lacks speciality of scheme and interest, and the action is rather slight and simple for a four-act drama. The plot and characters are, however, so well adapted to the tastes of Adelphi audiences that a long career for the piece may pretty safely be prophecied. A few playgoers may have expected that when Mr Buchanan joined Mr Sims in the concoction of an Adelphi drama that there would be an attempt to diverge from the main lines hitherto laid down for such productions, and, as a matter of fact, there is a certain measure of novelty in some minor particulars of the play. Mr Charles Dalton, as an Irish tenant who is hired by a rascally land agent into killing his landlord, and Miss Mary Rorke, as the sister of this tenant, nourishing an unrequited passion for the hero, both have rôles somewhat out of the ordinary course; while the “Royal Irish” constable of Mr J. L. Shine, and the Cockney bookmaker of Mr Lionel Rignold, are also more or less strangers in the Irish drama of to-day. Messrs Sims and Buchanan have, however, very wisely not departed widely from the models supplied them by the past. In the main “The English Rose” is a typical Adelphi play. The scene is laid in Ireland, and the hero, Harry O’Mailley, is a young Irishman, eldest son of a decayed squireen. He is in love with Ethel, niece of the English Baronet, Sir Philip Kingston, who has bought the squireen’s estates. That Baronet has a land agent, one Captain MacDonell, who, besides robbing his employer, has designs on Ethel, and a proportionate hatred for Harry. The first step in his plans is to get rid of Sir Philip, and this he does by inciting Randal O’Mara, the aforesaid tenant, to murder the old man. Harry gets wind of the intention, and arrives on the spot just in time to find Sir Philip dead, and to be mistaken for the assassin. MacDonell promptly takes advantage of the latter fact, and has Harry arrested. Meanwhile, Randal, who has been severely wounded by Sir Philip in the struggle for life, goes to the village priest and confesses his crime. The priest is the younger brother of Harry, but, greatly as he would like to divulge what he knows, his lips are closed by the seal of the confessional. Here we have an effective situation—recalling, of course, the recent production at the Haymarket. Harry is tried for the murder and condemned, but is rescued by the peasants, and Randal, now on the point of death, once more confesses—this time to his sister Bridget, who is thus able to proclaim Harry’s innocence. To the personæ already named have to be added a half-witted boy, devoted to the service of the hero, and a young London girl, represented by Miss Clara Jecks, who pairs off with the “Royal Irish” constable. All the characters are handled with skill and effect, and a special sensation is created in the scene where Harry, who has just won a steeplechase, gallops off on the victorious horse to intercept the men who have joined O’Mara in his raid on Sir Philip. There are weaknesses of construction here and there, and the play is altogether too long, but the frequent strokes of humour and sentiment, homely as they are, delighted to-night’s audience, and secured the success of the drama. The comic roles; played with perfect unction by Messrs Shine and Rignold, do not exactly overflow with wit, but they nevertheless have abundant drollery. Miss Olga Brandon, as the heroine, has hardly force enough for the Adelphi stage, for which an ampler method is needed, but she may by-and-by overcome this defect. Mr Thalberg, as the young priest, may also be expected to show eventually less coldness and stiffness. In other respects, the authors are well served by their interpreters. Mr Leonard Boyne, himself an Irishman, is thoroughly well suited to the rôle of Harry, which he renders picturesque and interesting. Mr Beveridge is impressive as the squireen, and Mr Abingdon is properly vindictive as MacDonell. O’Mara is made remarkably convincing by Mr Dalton. Miss Mary Rorke as his sister is tender and sympathetic; Miss Jecks is as pleasantly humorous as ever, and Miss Kate James sings an Irish song very prettily. The scenery is always adequate, and in some instances charming. Altogether it is not surprising that the piece was saluted with enthusiasm, and that everybody concerned in it was called before the curtain at the close.

___

The Daily Telegraph (4 August, 1890 - p.6)

ADELPHI THEATRE.

Whatever wrongs poor old Ireland may have suffered it has certainly not been at the hands of poets or dramatists of any nationality. Here are two more poets, two more dramatists—one pure Saxon, the other Scotch to the backbone—prepared once more to testify to the wit, the loveableness, the passion for country, the delight in sport and horses, the daredevil enterprise, the loyalty of the priesthood, the purity of the women existing in the Emerald Isle of the unbroken and unbreakable Union. Mr. G. R. Sims and Mr. Robert Buchanan come upon the field at an opportune moment with their hearty, discreet, and manly play, and the cheers as well as the enthusiasm of last Saturday night may have a deeper significance than many people imagine. Ireland, we feel sure, will accept “The English Rose” with that graceful courtesy which distinguishes the passionate nation, and allow it to rest side by side, as of old, with the green shamrock and the purple thistle. With no uncertain voice the huge Adelphi audience declared once more in favour of romance as against reality. They seemed to think that the sober truth of life was sad enough out of doors, and were not disinclined in the accustomed seats in the old playhouse to indulge in the pleasures of imagination. An Irish drama is still allowed, in spite of modern philosophy, to be picturesque, and that which pessimists sneer at as impossible was voted to be at least very palateable. Once more the spirit of Samuel Lover and of Dion Boucicault hovered over the time-honoured Adelphi. “You may break, you may shatter the vase if you will, But the scent of the roses will hang round it still.” Tom Moore himself would not have disdained the homely sentiment and pure affection shed from the pretty petals of “The English Rose.” The humour-loving peasant was allowed to adore the young master; the graceful English lady was found honestly in love with the enemy of her proud, cold race; the strictly-conscientious sergeant of constabulary could not restrain his sneaking affection for a plucky young Irishman who loves horseflesh far better than politics; the ruined Knight of Ballyveeney honestly bears misfortune, and, in the true spirit of a fine old Irish gentleman—“one of the olden time”—instead of spouting on the village green, the priest is churchman not rebel; the women have hearts and the men are made of muscle. But perhaps best of all—the most admirable feature in the new play—we find in the peasants, the moonlighters, the lovers of sport, the colleens, and the reckless brandishers of the blackthorn, just that exquisite flavour of humour, just that innate love of poetic justice, just that spice of native wit which proclaim the Irish nature all over the world, and will outlive—as they have outlived—the bitterness of political strife and the animosity of antagonistic races. Mr. Sims and Mr. Buchanan have surely done their work remarkably well. Without pandering to passion or prejudice they have illuminated the Irish character on its best and heartiest side as the poetic dramatists did before them. Where realism might have created discord imagination has promoted peace. It was no easy task at this important hour. Mr. Sims is enthusiast but cynic as well. Mr. Buchanan is a passionate controversialist, who can brandish a shillelagh as well as any Irishman who ever lived. They have elected to deal with the fire of politics, the earnestness of religion, the contradictory prejudices of men who hate and of women who love. Let it at least be granted them that in their honest endeavours to amuse they have not been guilty of a single error of taste. They have not falsified the Irish character, and they have given the Adelphi a good play.

There must be some secret clause in the agreement between the Messrs. Gatti and the authors who work for them with such success that they shall never dare to submit a scenario without the introduction of one time-honoured situation. Whatever happens, the hero must, by the conditions of the Adelphi—which, like the laws of the Medes and Persians, alter not—be found in the presence of a murdered man, be accused of the murder though obviously innocent, be tried and unjustly convicted, be proved innocent, and be supported in his bitter tribulation by the devoted heroine. It does not matter if it is a working-man story in Clerkenwell life, or a sailor story, or a soldier story, or a rustic story, or an Irish story—there the situation must be. Harry Greenlanes the scamp of a poacher, Tom Salt the marine, Bill Belt the recruit, must, by the unalterable Adelphi law, be found near the body of a murdered man who has been assassinated by someone else. Shades of old Jonathan Bradford! it occurs once more in “The English Rose.” Henry Pettitts may come and go, Sidney Grundys may appear and disappear, new collaborators ad combinations of new collaborators may be selected, but up comes the old situation. It is not only the backbone of Adelphi drama, but it is apparently the keynote of the dramatic formula. Still let it not be imagined that the new play wholly depends on the time-honoured situation. It was inevitable that the spirited young Harry O’Mailley, who was born in the saddle, should be accused of murder on a moonlighting raid. His agony at being charged with such a crime in the presence of his old father and his beloved Ethel Kingston—the English Rose—his arrest for a deed of which he is wholly innocent, his trial and the love of the boys for the young Irish master, his rescue from a strong military force with fixed bayonets, and his sanctuary in the Catholic chapel, are almost necessary incidents in this class of play. But, in addition, there are scenes as novel as they are effective. The first that strikes the spectator with a sense of novelty, and is not, by the way, wholly destitute of personal danger, is that in which Mr. Leonard Boyne, who has just won a local steeplechase, hears of an intended moonlight murder at a romantic but lonely spot in lovely Connemara, and gallops off to the rescue after cutting down his opponent as if he were in a cavalry charge. Now a horse on the stage is awkwardly situated at any time, but it was lucky that in Mr. Boyne was found a plucky horseman and a practical cross-country rider. The least hesitation, and the thoroughbred would have leaped into the orchestra. But somehow or other the moment of inspiration seemed to come. The young Irish hero lashed at his opponent, who dragged at his horse’s bridle, and made the beast snort with excitement, as if the open grassland of Connemara was before him, instead of the confined wings of the theatre; but it was all done with such spirit and such vraisemblance that the house rose at the horseman, who in this case happened to be an actor. Whether such experiments are wise is another question. There is nothing succeeds like success, and Mr. Leonard Boyne was the hero of a reception that has not been heard in a theatre since George Belmore won a race at the Holborn on Flying Scud.

The next important scene—in reality the very best dramatic episode—in the play is where the hero has been arrested for the murder, and, thanks to the kindness of a generous constabulary sergeant, is allowed to take leave of his father, who is just about to sail for America, as if nothing had occurred. Deep depression has instantly to be exchanged for forced gaiety, and the poor old father’s honest tears of farewell and his song arrested by emotion contrasting with the false hilarity of the assembly, form a dramatic situation of singular skill. It was not the author’s fault that the scene did not go so well as it ought to have done. The material was there, and actors and actresses have seldom had a better chance of illustrating a genuinely pathetic moment. No one can account for these little temporary failures. The scene may have gone ten times better at rehearsal than it did on Saturday, and, if we mistake not, this in due time will be one of the most effective and genuinely emotional scenes in the new drama. But it requires acting, and the modern theory seems to be that acting comes of itself. It does nothing of the kind. The realists insist hat the best acting is that which is most natural. Quite so, but that very nature is only acquired by the severe practice of the art of acting. Such scenes as these do not come of themselves; they are the result of intense application.

And there is yet another dramatic variety of the play of considerable value. In the archives of the old French drama will be found a play—written and produced long before the French original of “A Village Priest”—of which in all probability neither Mr. Sims nor Mr. Buchanan have ever heard. It is a strange and extraordinary coincidence, but in this old French play, “The Priest’s Oath,” occur incidents almost identical. Two brothers are in love with the same girl. The elder, inspired by a sense of honour, refusing to be his brother’s rival, enters the priesthood. And in this play there is a murder. Terror-stricken at the prospect of death, under the sacred seal of the confessional, the murderer confides his guilty secret to the young priest. At this very instant, through an unfortunate combination of circumstances, the younger brother is accused of the murder. Circumstantial evidence is strongly against him. He is tried, convicted, and sentenced to death, while the unhappy priest, who by one word could save his brother’s life, is compelled to look on in silence while he is condemned to a felon’s death. Here occur two of the most striking scenes in the old French play. In the first the priest beseeches the murderer to avow his guilt. He, however, remains obdurate, resolving to face perdition rather than leave the woman he loves to his rival. The other scene is between the two brothers of the heroine. The younger brother had reason to believe that the priest is cognisant of the real murderer. The scene of agonised appeal, remonstrance, and reproach on the one hand, intensified by the struggle of fraternal love and sacred duty on the other, is only interrupted by the approaching execution. The innocent man is led forth to death. At the supreme moment the murderer dies, avowing, at the instigation of his sister, the innocence of his rival. So far the old French play, the principal scenes of which are laid in Corsica, and deal with a vendetta between two rival families. Now, in the Adelphi play this fraternal, sacerdotal incident—which may have occurred in dozens of stories—is only of subsidiary interest, but we fancy it might have been made more vivid and important by the players if they were not so inclined to under-act. Mr. Dalton, as the repentant murderer, no doubt played with surprising force, and always with picturesque effect; but Mr. Thalberg had modelled his idea of the “pale-faced priest” on a Ritualistic curate, and not on any known form of the Irish ecclesiastic. He had strayed from St. Alban’s, High Holborn, or the silent sanctuary of All Saints’, Margaret-street, and not from Maynooth, and consequently these important scenes lacked vigour and virility. Picturesque the priest was always, whether as to coat, cassock, hat, or biretta, but if we may use such a phrase, he was lackadaisical. It was impossible to believe that the hearty old Knight of Ballyveeney could have been the father of two sons so unlike in temperament as Mr. Leonard Boyne and Mr. Thalberg. For it is a mistake to suppose that taking orders in the Catholic priesthood necessitates an access of namby-pambyism. A priest—particularly an Irish priest—can be as plucky and manly as a soldier. The fact that this priest had nobly relinquished the world for love’s sake would suggest that at that very moment he abandoned mere sentimentality for action—he had crushed sentiment and become a man. The play would gain immensely in interest if Father Michael could be a little less milk-and-watery; in fact, if he would mix a little good Irish whisky with the water and leave out the milk.

But Mr. Thalberg was not the only offender in this respect. Far too much of the acting on Saturday night was a little off colour. It is a mistake. Adelphi drama cannot be played in white kid gloves. Cynical critics may call it unnatural, producing impossible men and women; but it is not made more natural or possible by mumbling and under-acting. The drawing-room style is wholly out of place in this popular theatre, just as the Adelphi style would be wholly absurd at a playhouse where minute effects are so invaluable. At the Adelphi you must paint with a bold brush and put on the colours, not necessarily with vulgar excess, but in a spirited fashion. Mr. Leonard Boyne has seen the sense of this, and has seldom played so well. He keeps the action going, and never lets it down. If he had played Harry O’Mailley in the same style that he played George d’Alroy or Captain Walter Leigh he would have made a fatal mistake. There must be no reserved force at the Adelphi. An Irish hero of this pattern must go in and win. In every scene Mr. Leonard Boyne went in and won. When the play dropped, he picked it up again. There is no other way to act at the Adelphi. If further illustration of this truth were wanted it would be found in the charming picture of the old Irish gentleman by Mr. J. D. Beveridge—a picture in a picture—clear, distinct, true, and pathetic; in the Randal O’Mara of Mr. Charles Dalton, a really remarkable study in melodramatic art; in the two spirited comic sketches instinct with life and humour by Mr. J. L. Shine and Mr. Lionel Rignold, the one Irish the other Cockney to the backbone, comic characters infinitely truer to art than the Adelphi comic sketches of years ago; in the delightful little bit of humour from that clever actress Miss Clara Jecks, and in the Irish waif Patsie Blake, which wants a touch more colour yet from artistic Miss Kate James. Of the performance of the heroine by Miss Olga Brandon is would not be fair ye to speak. This popular actress was almost inaudible from hoarseness, and there is no more dispiriting malady than a severe cold. Miss Olga Brandon was not herself, and seemed to be quite prostrate with overwork. Miss Mary Rorke had very little to do, and seemed to suggest bitterness instead of sorrow. It was difficult to feel much sympathy for the broken-hearted Bridget O’ Mara. Mr. W. L. Abingdon gave an excellent, effective, and unconventional rendering of the conventional villain, and good work was done by Mr. Bassett Roe, Mr. James East—a most energetic fugleman of Irish peasants, who kept the game alive—and by Miss Essex Dane.

Of the success of the new Irish drama there is no question, and, apart from the cleverness of authors and skill of players, it was emphasised by the excellent stage management of Mr. William Sidney and the liberality of the Messrs. Gatti, who have given them stage scenes as beautiful and romantic as ever illustrated “The Colleen Bawn,” “Arrah-na-Pogue,” or “The Shaughraun.” A chorus of cheers brought on authors, actors, stage-manager, every kind of favourite, and the audience were not to be appeased until Mr. Gatti made his bow. Once more it was an Adelphi triumph.

___

The Manchester Courier and Lancashire General Advertiser (4 August, 1890 - p.5)

FROM OUR LONDON CORRESPONDENT

[BY PRIVATE WIRES.]

LONDON, SUNDAY NIGHT.

. . .

The English Rose, by Messrs. Robert Buchanan and George R. Sims produced last night at the Adelphi, is a conventional but, nevertheless, entirely satisfactory production, admirably suited to this theatre, the recognised home of melodrama. Many feared that the result of the Buchanan-Sims collaboration would be an attempt to “elevate” a class of piece which has ever been identified with this house. Adelphi audiences are happy so long as they have a stirring play containing all the familiar features of bygone successes, and, no doubt, the sorrows of the heroine and her true lover, the machinations of the gentlemanly and the comic villains, and the time-honoured comic pair of lovers in The English Rose will attract for many months to come. The success of the piece, indeed, was emphatic, and its admirable interpretation by an exceptionally strong company won high praise, Miss Olga Brandon, Miss Mary Rorke, Miss Clara Jecks, Miss Kate James, Mr. Leonard Boyne, Mr. J. L. Shine, Mr. W. L. Abingdon, and Mr. Charles Dalton conspicuously distinguishing themselves.

___

The Stage (8 August, 1890 - p.8)

What an obliging stream of water that is at the Adelphi. On Saturday, during the progress of The English Rose, it ceased its running in a most polite manner, so that some of the characters might have a hearing. In the same drama a horse, that is supposed to win a steeplechase, is shown in its loose box. On Saturday this horse looked round the house with a sort of “well, I’m blowed” expression, and then endeavoured to seize and eat some stage foliage. Later on that horse nearly “went” for the stalls, and bets were made as to his clearing the orchestra or dropping on the first violin. Thanks to Mr. Leonard Boyne all terror ceased, and the animal—a fine fellow—went through its duties in grand style.

Speaking of The English Rose, is there any great necessity for the introduction of those lines between Louisa Ann Fergusson and Sergeant O’Reilly about a shirt? The expression “You can bet your shirt” is commonly used, I know, but there is surely no reason for authors like Sims and Buchanan to put it in the mouth of a man addressing his sweetheart, so that a laugh may be raised. They are both capable of better things. The joke (?) is, moreover, labouredly driven home by unnecessary additions. Another question: why should Mr. Leonard Boyne and Miss Olga Brandon be starred at the Adelphi? Why should Messrs. Abingdon, Beveridge, Thalberg, Shine, and Misses Mary Rorke and Jecks be compelled to cross the stage in response to a call, and Mr. Boyne and Miss Brandon be permitted to languidly bow their thanks from the prompt side? It’s a strange world, my masters.

___

The Stage (8 August, 1890 - p.9)

LONDON THEATRES.

_____

THE ADELPHI.

On Saturday evening, August 2, 1890, was produced, at this theatre, a new and original four-act drama, written by Geo. R. Sims and Robert Buchanan, entitled:—

The English Rose.

Sir Philip Kingston ... ... Mr. Bassett Roe

The Knight of Ballyveeney ... Mr. J. D. Beveridge

Harry O’Mailley ... ... Mr. Leonard Boyne

Father Michael O’Mailley ... Mr. T. B. Thalberg

Captain Macdonell ... ... Mr. W. L. Abingdon

Nicodemus Dickenson ... Mr. Lionel Rignold

Randal O’Mara ... ... Mr. Charles Dalton

Sergeant O’Reilly ... ... Mr. J. L. Shine

Patsie Blake ... ... Miss Kate James

Shaun ... ... Mr. W. Northcote

O’Brien ... ... Mr. E. Bantock

Farmer Flanagan ... ... Mr. H. Cooper

O’Shea ... ... Mr. J. Howe

Ethel Kingston ... ... Miss Olga Brandon

Bridget O’Mara ... ... Miss Mary Rorke

Louisa Ann Fergusson ... Miss Clara Jecks

Judy ... ... Miss Essex Dane

Biddy ... ... Miss Madge Mildren

Norah ... ... Miss Janette Reeve

Mary ... ... Miss Nellie Carter

In their new play, Messrs. Sims and Buchanan have merely given the theatrical kaleidoscope another turn, and introduced us to old friends freshly-dressed and familiar scenes re-coloured, none the less acceptable because they are well known and quickly recognised. It had been rumoured that The English Rose would bring us face to face with a new phase of priesthood, a pschycological study, that Mr. Grundy’s strange and wrongly-drawn ecclesiastic in A Village Priest would be but as a trifling conundrum compared with the new development which was to raise and sustain discussion. Fortunately, we have been spared all this. The age has not arrived for religious arguments to hold sway upon the stage, and audiences, particularly Adelphi ones, want dramatic action and vigorous treatment rather than sermons, be they religious or moral. The play’s the thing after all, and it is pleasant to be able to state that The English Rose is a well constructed, admirably written, interesting, exciting, and amusing Irish drama, that will surely hold the boards for some months to come. The authors have been successful in exactly catching the true spirit of the Irish play as introduced to us by that pastmaster of Hibernian drama, Boucicault, and they deserve unstinted praise for their clever work.

The main plot of The English Rose is as follows:—Harry O’Mailley and father Michael O’Mailley are sons of the Knight of Ballyveeney—a grand old Irish gentleman, generous-hearted, impulsive, and ready-witted. Times are bad, and the Knight of Ballyveeney has been sent for from America, where a wealthy relative has died, leaving him all his money. Bridget O’Mara, a pretty young lady, a ward and neighbour of the Knight’s, has always been considered in the light of a sister only by the handsome and impetuous Harry; but she, poor girl, has let her heart go out to him, and lives only for his dear sake. An English girl, Ethel Kingston, niece of Sir Philip, a landlord led by the nose by his evil-minded agent, Captain Macdonell, has attracted Harry, and the young couple have fallen over head and ears in love with each other. Harry has arranged to ride his own horse at a steeplechase, and Ethel, known as “The English Rose,” has determined to see him do it—and win. Macdonell, Harry’s rival, has warned Sir Philip of the young girl’s clandestine meetings, with the result that Sir Philip appears upon the scene, and commands his relative to accompany him home. Ethel will not, and she tells her uncle that she loves Harry, and, being her own mistress will do as she pleases, whereupon the old man turns fiercely upon Harry, and calling him a penniless beggar and a schemer, strikes him. Harry’s blood is up, and in unguarded language he unwisely threatens Sir Philip that he will yet repent his work. The race is won by Harry, who, elate with his triumph, is about to depart home, when he is stopped by Patsie Blake, a half-witted lad, who tells him of a plot he has overheard, whereby Sir Philip is to be driven to the “Devil’s Bridge” by one Nicodemus Dickenson, and there attacked. Remounting his horse, Harry is about to follow the car, when he is again stopped, this time by Macdonell, who wishes to detain him, but Harry cuts him across the hand with his whip and gallops off. He arrives at the “Devil’s Bridge” too late to be of any use. Sir Philip and his companions have been shot at by Moonlighters, and the old man is on the ground when Harry finds him. The masked murderer is seized by Harry, but after a brief struggle manages to escape, leaving his gun in the hands of the young Irishman, who, loud in his expression of grief, kneels over the body of the murdered man. At this moment Ethel runs hastily to the scene, and, being falsely impressed with what she sees, accuses her lover with the murder, an accusation that is overheard by Macdonell. Though the murderer escaped in the affray at the “Devil’s Bridge” he was wounded with a shot from Sir Philip’s revolver, and it is only after great exertion that he manages to reach his home, and his home is that of Bridget O’Mara, for he is Randal, her wild, dissipated brother, who, listening to the promptings of Macdonell, and hearing from him that Sir Philip is about to turn him and his out of house and home, determined to rid the country of “the tyrant” and earn the goodwill of his fellows. Now that the deed is done, however, remorse takes the place of bitter hatred, and, fearing he is about to die from his wound, Randal confesses to Father Michael his guilt. The priest urges him to make reparation before he dies, but Randal dare not tell his sister, who, poor soul, thinks the distress of her brother arises from contrition after a heavy drinking bout, and a wound obtained in a brawl. This incident brings about the strong situation of the play, as will be seen hereafter. Randal has hurried the priest up to his (Randal’s) bed-room that his wound may be dressed, and presently Bridget is astonished by the entrance of Harry, who bears in his arms the inanimate body of Ethel, who, overcome with the horror connected with her uncle’s death, has swooned. The girls are left together. After Bridget has undergone the agony of hearing the man she passionately worships pouring frenzied words of love into the ears of the unconscious girl, and after some natural hesitation, she opens her arms, and the two girls embrace, and promise to be to one another as sisters. Here it may be noted that Bridget had confided in Father Michael her unfortunate love for his brother, and the young priest had told her the story of his own life, how that when young he madly loved a beautiful girl, who would not listen to his tale, that he then was prompted by a voice within that told him that as he had suffered so should he endeavour to live that he might comfort others in their affliction, and guide them safely out of all their trials. With this one object in view he had entered the Church and become a priest. Upon hearing this Bridget fell at his feet, and promised him to try and bury the past and be guided by him, who, having deeply suffered, must know what she endures. So it comes that we find Bridget and Ethel, rivals in love, together as sisters. The repose of the scene is soon rudely disturbed, for Macdonell and his crew, unwillingly backed up by Sergeant O’Reilly, a fine-hearted fellow, and his men, now enter and accuse Harry with the murder of Sir Philip. This is a strong scene. Here is the young priest, pale and resolute in the strength of his confessional vow, fully knowing his brother to be innocent, yet powerless to help him. Once more he urges Randal, who reappears, to publicly confess and save his brother, but in vain. Bridget appeals to the priest, tells him he knows Harry is not the murderer, and that in the exercise of his sacred calling he must know who is; but it is hopeless, and Macdonell and his crew depart triumphant, leaving Harry in the hands of Sergeant O’Reilly. The feelings of the audience have at this point been strongly wrought upon, but a stronger scene, more pathetic in its nature, and not so foreign to the ordinary playgoer follows. Jovial, good-hearted old O’Mailley, the Knight of Ballyveeney, who has heard nothing of the murder, is seen coming to the O’Mara’s house to bid his much-loved sons and the pretty Bridget good-bye before he starts on his trip to America. In an instant the word is passed round, and the piteous cry of Harry that his father shall hear nothing, see nothing to make him sorrow before he departs is faithfully regarded. It is here that the forced mirth and tearful gaiety of the scene touches the audience to the quick. Glasses are handed round, and the jolly sergeant and his men explain their presence in a perfectly natural manner, as with toast on lip and hearts full of pity they wish the old man God-speed and safe return; and the old knight, bravely keeping back the sob that nestles in his throat, attempts to sing a song, but failing in his task, carries it off with a forced laugh. It is all very truthful this scene, poetically conceived and well worked out. The deception has been perfect, and, followed by the blessings of his priest-son, the father leaves his family and friends, whose grief is all the more poignant for the following reaction. The months go by, and the trial of Harry for murder is at hand. The lad Patsie has given his evidence, and has been laughed at, the jury return their verdict, and Harry is to be hanged. On this day, of all days, the old father returns from America, rich in pocket with his relation’s gold, rich in heart with the love that has hurried him back to his sons. Harry may be sentenced to death, but that is no reason why he should not escape, and, in the weakest scene in the play, he is rescued, despite the efforts of some dozen soldiers and policemen, by his friends, and, putting out his best foot first, makes a rush for it, embraces his father, clears his pursuers, and, for the time, is lost to them. In the meantime Father Michael has been suffering much. Frequently he has tried to persuade Randal to tell the truth, but in vain. The good priest has just concluded evening service in his pretty little chapel by the sea. All around is peaceful and quiet, when suddenly Harry appears, followed by his would-be captors. In a moment the unfortunate man is taken into the church, and the priest at the porch forbids the crowd to enter the sanctuary. Matters are now quickly brought to a climax, for Randal, weak and in a dying state, arrives to see the priest. What he would say is of little consequence, for he is soon recognised by Patsie Blake, the half-witted, whose half-smothered cry of surprise is taken up by Bridget, who now understands all. She remembers the wound on the night of the murder, her brother’s condition, and his anxiety to drive her from him. In agony the heart-broken girl follows her brother off the scene. She soon returns, and with bowed head tells the expectant crowd the tale of her brother’s sin, and also of his death. Harry and Ethel are united at last, and thanks to the care of O’Reilly and his merry little sweetheart, Louisa, confession has been wrung from Nicodemus Dickenson, who freely reveals the plot instigated by Macdonell, who is then handcuffed, with much glee, by O’Reilly. Bridget, the heart-tossed, loving and forsaken girl, amid the general happiness passes quietly into the church, sufficiently indicating that for her there is no more worldly happiness, and the play ends.