|

Play List: 4. Corinne 7. The Mormons 9. Lucy Brandon 10. Storm-Beaten 11. Lady Clare 13. Bachelors 14. Constance 15. Lottie 16. Agnes 17. Alone in London 18. Sophia 19. Fascination 20. The Blue Bells of Scotland 21. Partners 24. Angelina! 25. The Old Home 26. A Man’s Shadow 27. Theodora 29. Clarissa 30. Miss Tomboy 32. Sweet Nancy 33. The English Rose 36. Marmion 37. The Gifted Lady 38. The Trumpet Call 39. Squire Kate 40. The White Rose 42. The Black Domino 44. The Charlatan 45. Dick Sheridan 47. Lady Gladys 48. The Strange Adventures of Miss Brown 49. The Romance of the Shopwalker 52. Two Little Maids from School ___ |

|

ROBERT WILLIAMS BUCHANAN (1841 - 1901) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

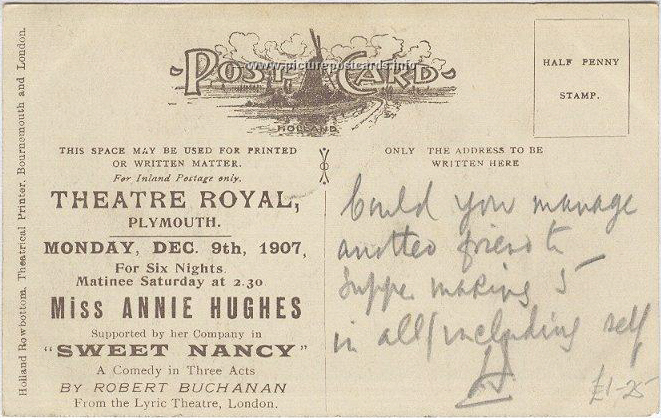

THEATRE REVIEWS 32. Sweet Nancy (1890) - continued

The Referee (12 October, 1890 - p.3) Since “Sweet Nancy” was produced at the Lyric, Mr. Robert Buchanan, who does a good deal in tinkering, one way and another, has found time to effect some changes in the play, but my verdict still remains what it was at the first trial. The changes that are specially remarkable in the representation at the Royalty are changes in the company. The part of the adventuress is now played by Jenny McNulty, whose plenteous charms are set off to the best possible advantage in a series of pretty frocks, and that’s all I have to say about her performance; whilst Mr. Yorke Stephens, vice Henry Neville, sighs like half-a-dozen furnaces in the character of the amorous General, and plays the very Neville with the part. Miss Annie Hughes, who is getting quite fat in the face, is still an incomparable Nancy. |

|

|||

|

[Advert for Sweet Nancy from The Scotsman (14 October, 1890 - p.1).]

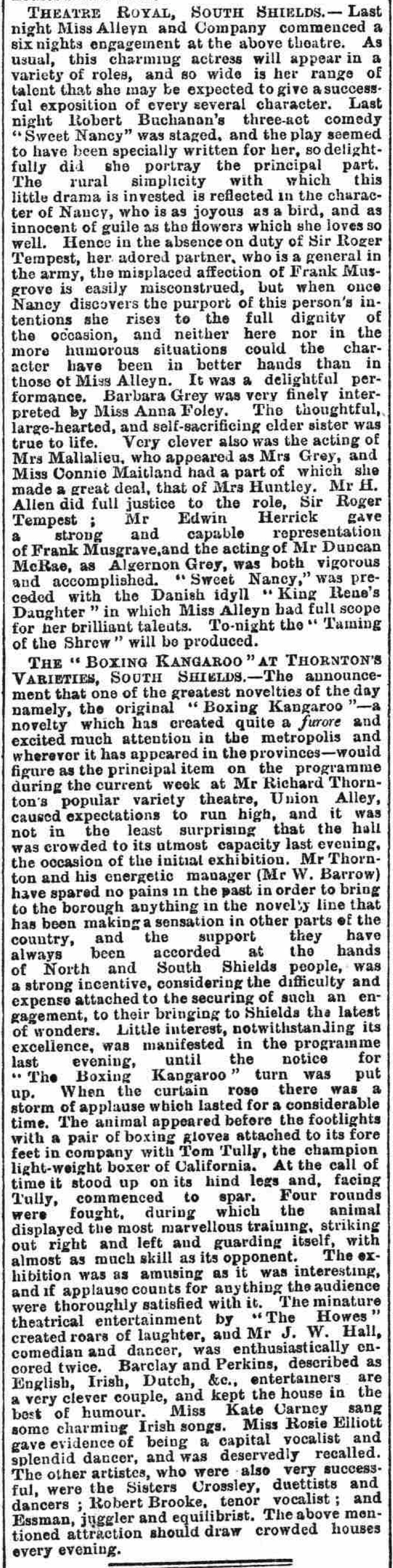

The Shields Daily Gazette and Shipping Telegraph (7 March, 1893 - p.3) |

|||

|

|

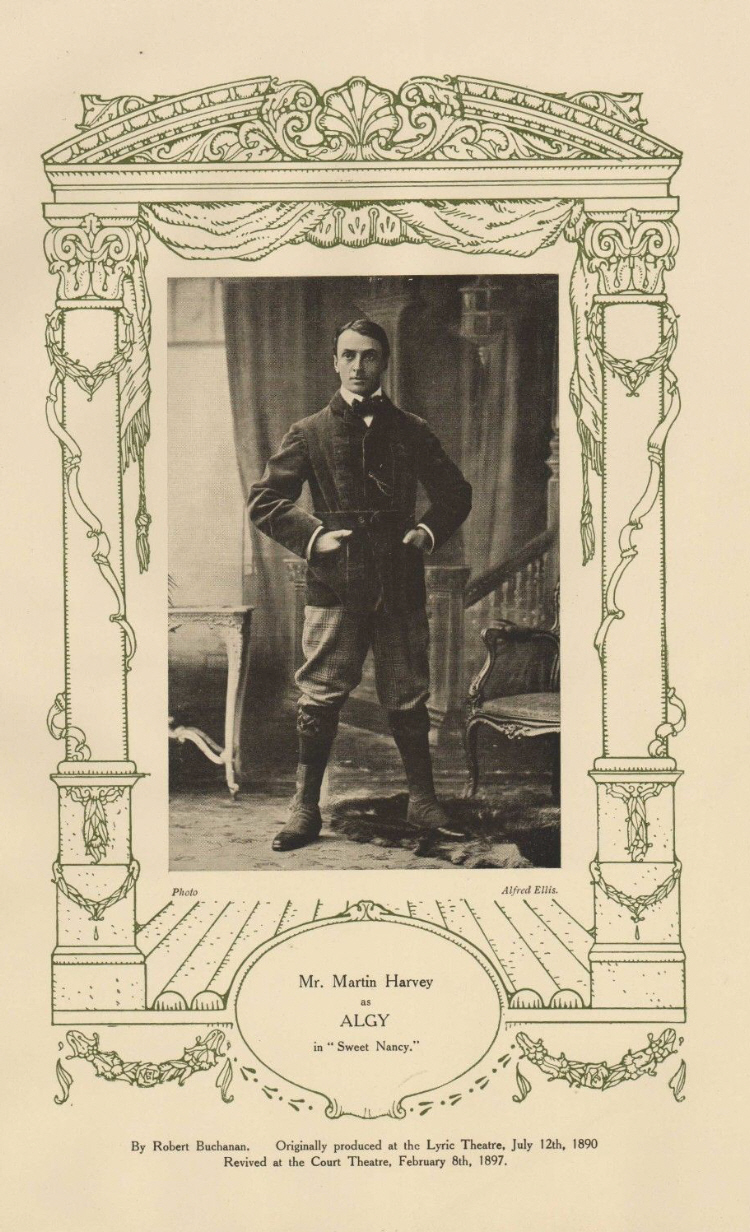

The Echo (11 December, 1896 - p.2) CRITERION THEATRE. MISS ANNIE HUGHES’ REVIVAL OF It was a very happy notion of Miss Annie Hughes to set Sweet Nancy once more before us, a very timely reminder to playgoers in general, and critics in particular, that in this charming and vivacious young lady we have not only an expert and, in her own line, unrivalled comedienne, but also an actress who can call forth sympathy and our tears. Mr. Buchanan’s very successful adaptation of Miss Rhoda Broughton’s novel has lost none of its freshness or fragrance since it was seen at the Lyric and the Royalty about six years ago, and, though Mr. Henry Neville and Mr. Yorke Stephens have made way for Mr. Edmund Maurice in the part of General Sir Roger Tempest, and pretty Miss Lena Ashwell follows Miss Harriet Jay as Barbara Grey, happily Miss Hughes still remains to give us her vivid and bewitching sketch of “Sweet Nancy”—Lady Tempest. The scene of separation that concludes the second act was never better played by the actress. Nancy’s frantic entreaties to her husband not to go to the war had all the poignancy and girlish pathos that attaches to genuine cris de cœur. Needless to say that Miss Hughes rendered the tomboy aspects of captivating gaucherie and naiveté of Miss Broughton’s heroine with wonderful delicacy and aplomb. Mr. Maurice was rather gruffer than Mr. Neville, and perhaps scarcely suave and dignified enough, but on the whole he has never acted better. He gave a perfectly sincere and virile performance. Mr. C. M. Hallard, who used to play Bobbie Grey, makes the lover much more plausible than Mr. Garthorne. Miss Lena Ashwell strikes the right key as Barbara Grey, and Miss Helen Ferrers sustained a very promising reputation as Mrs. Huntley. Mr. Martin Harvey following Mr. Henry Esmond is delightfully boyish and calf-like as Algernon Grey, and Mr. Charles Rork gives a clever character sketch of Mr. Grey. A very pleasant afternoon. By the way in the Royalty programme Grey (now described as a country gentleman) has his name spelt with an “e,” in the Criterion bill it is printed with an “a.” We notice this discrepancy and ask for an explanation, inasmuch as we have never read Miss Broughton’s novel of Nancy. ___

The Morning Post (11 December, 1896 - p.3) CRITERION THEATRE. Miss Annie Hughes yesterday gave a special afternoon performance at the Criterion Theatre. The first piece was a one-act play entitled “An Old Song,” by the Rev. Freeman Wills and A. Fitzmaurice King. It has not been played before in London, and was very favourably received, being a touching idyllic story of Rouget de l’Isle, who is represented as starving in a garret until his old friend, Signora Rosetti, takes up his song, “The Marseillaise,” and sings it at the Opera House, where it at once becomes popular, so that it is repeated in the street outside. But the success comes too late; the poet dies before he has enjoyed his fame. Mr. Martin Hervey played the poet and Miss May Whitty the singer. “Sweet Nancy,” adapted by Mr. Robert Buchanan from Miss Rhoda Broughton’s novel, was the principal piece. Though not new it has not been lately given, and was followed with great interest. The first act relates the courtship of General tempest and Nancy Gray, a young lady whose disposition is that of a schoolgirl. She accepts him without the slightest serious notion of the responsibilities she is undertaking. In the second act Nancy, as the young wife, shocks the conventional people about her by her girlish naiveté; the General goes off to a war and leaves her alone, and his young friend Musgrave decides to take advantage of his absence to seek for himself the affections of Nancy. Nancy supposes that Musgrave’s visits are meant for her sister Barbara, and so she encourages them. In the third act, a year after the second, the General comes home. Musgrave takes the opportunity to declare his passion to Nancy, who resents it, in the hearing of Barbara. The scoundrel is sent packing, and the General finds his wife the same naïve, good girl that she was at the beginning. Miss Annie Hughes played Nancy with great skill, rendering the light and serious shades of the character with force and truth. Miss Lena Ashwell gave her excellent support as Barbara; and Mr. Edmund Maurice made a good General. The other parts are unimportant, but were very fairly represented. There was a good house, which was most appreciative of the merits of the play and of the acting. ___

The Daily Telegraph (11 December, 1896 - p.13) CRITERION THEATRE. “Sweet Nancy,” adapted by Robert Buchanan from Rhoda Broughton’s once very popular novel, is a charming play, and, as acted now, if put into an evening bill, would attract the thousands of playgoers who delight in a happy combination of humour, nature, and tenderness. When produced six years ago at the Lyric, there was something wrong with Nancy. It was rather a promising than a wholly successful work. We suspect that it was not very well acted, and we have it on record that it was not well rehearsed. Consequently, the poor author suffered, as authors invariably do, from some mistake in casting, or from just that want of pulling together which often makes all the difference between a hesitating and a unanimous verdict. We cannot speak from authority, but from reading what we wrote about “Sweet Nancy” in 1890; and seeing the play again in 1896, it seems to us that it must have been altered, and altered for the better; that the pulling together has been accomplished, and that the part of Barbara Gray, the Martha sister, as opposed to the Mary sister, has been marvellously improved, for the good alike of the actress and the play. Of one thing we are certain, and that is, from first to last “Sweet Nancy” could scarcely be better acted than it was yesterday afternoon. We have, too, what such delicate and poetic work requires—harmony and atmosphere. We seem to know the family of the Grays by heart, the testy, techy, dictatorial father, the sweet, consoling mother, who lives in her children’s love, the bumptious Sandhurst cadet, the hobbledehoy, with sporting tendencies, the red-haired tomboy sister, the brat, all of them. They are photographs of many an English home. They are recognised at a glance. Miss Rhoda Broughton has suggested them; Robert Buchanan has made them realities on the stage. And we all know, love, and appreciate Nancy, the innocent, natural, and adorable Nancy, who, in the bright and brilliant person of Miss Annie Hughes, carries us straight away to the comedy days of Mrs. Bancroft when she created Polly Eccles and Naomi Tighe. Six years have worked wonders in ripening the style and adding in the experience of this delightful actress. Possibly she was as good in 1890 as now in the first act of pure comedy, fresh, bright, and exhilarating, but she displays now finer gradations of art in showing how the child-wife gradually becomes the woman. A child-wife she always is, and ever must be, but years of added experience have given to Miss Annie Hughes the power of showing how the responsibilities of marriage sober the most playful of women. The change from child to woman was very subtle and artistically defined. We find now what we failed to find in the “Sweet Nancy” of 1890—real grief, real emotion, real tears. The Nancy of Miss Annie Hughes deserves to be wider known than it is at present; it proves that we have in this genuine artist, with her combined sense of humour and adherence to nature, a comedy actress of the first class. Barbara Gray, the Martha sister—the self-sacrificing, patient, unselfish, lovable woman—is a beautiful conception. It would be difficult to find a part so sweet and sympathetic played with greater charm, decision, and tenderness than by Miss Lena Ashwell, who has forgotten her accentuated manner, and acted yesterday as she has seldom acted before. The scene in which, with an agony of pain in her firm countenance, the suggestion of tears suppressed in her soft eyes, and not one vestige of excess or violence— her voice as soft as music and as clear as a bell—she dismisses her sister’s empty-headed lover, on whom she also had bestowed her heart, was as admirable in effect as it was beautiful in idea. Equally good was the scene with her sister’s husband, when Barbara explains the tangled situation, stands up for her little sister’s honour, and, with a gentle, martyr-like resignation, claims some pity on account of her poor broken but patient heart. Two such performances as these by Miss Annie Hughes and Miss Lena Ashwell are seldom seen in modern plays. The character of the middle-aged lover properly falls to Mr. Edmund Maurice, and he makes of him a fine, manly, soldierly fellow, who is not ashamed of his gentle, loving nature and his tender heart. M. C. M. Hallard, a very promising young actor, with a delightful voice; Mr. Charles Rock, a little bit too fussy, perhaps; Mr. Martin Harvey, earnest, dogged, and, boylike, quick to take offence; Mr. Kenneth Douglas, the boy as of old; and Miss Henrietta Cowen, the gentle mother—all helped the play to the success it unquestionably made. ___

The Standard (11 December, 1896 - p.3) CRITERION THEATRE. A special matinée was given yesterday at the Criterion by Miss Annie Hughes, apparently for the purpose of re-introducing Mr. Robert Buchanan’s adaptation of Miss Rhoda Broughton’s “Nancy.” Though in some respects very clumsily done—as, for instance, when, in the first act, Nancy comes forward and betrays the incapacity of the adaptor by delivering a long soliloquy explaining all that has happened and how Sir Roger Tempest has proposed to her—a fair idea of the book is given in the play; and Miss Annie Hughes interprets the character of Nancy in a singularly natural and girlish fashion, with a quiet sense of humour and some very effective little touches of pathos. ___

The Era (12 December, 1896) MISS ANNIE HUGHES’S MATINEE. At the Criterion Theatre, on Thursday Afternoon, Dec. 10th, General Sir Roger Tempest ... Mr EDMUND MAURICE Mr Robert Buchanan’s adaptation of Miss Rhoda Broughton’s novel “Nancy” was first seen at the Lyric Theatre on July 12th, 1890, with Mr Henry Neville as Sir Roger Tempest, Mr Buckland as Frank Musgrave, Me Ernest Hendrie as Mr Gray, Miss Ethel Hope as Mrs Gray, Miss Harriet Jay as Barbara, Mr Henry V. Esmond as Algernon Gray, and Miss Frances Ivor as Mrs Huntley. The version was subsequently transferred to the Royalty Theatre on Oct. 6th of the same year, Mr Yorke Stephens being the Sir Roger, Mr C. W. Garthorne the Frank Musgrave, and Miss Jennie McNulty representing the designing widow. Mr Buchanan’s adaptation formed the chief attraction at Miss Annie Hughes’s matinée at the Criterion Theatre on Thursday last. We have already twice dealt with the merits and demerits of the work, and need now only record that Mr Edmund Maurice made an easy, natural, and quite gentlemanlike Sir Roger Tempest; that Mr C. M. Hallard was thoroughly effective as Frank Musgrave; that Mr Charles Rock, though emphatic and domineering enough, made Mr Gray rather too common and vulgar; that the “boys” were well played by Mr Martin Harvey, Mr Kenneth Douglas, and Master Grose; that Miss Henrietta Cowen duly depicted the meek supineness of Mrs Gray; that Miss Lena Ashwell was sweet and gentle as Barbara; that Miss Annie Hughes was as charmingly simple and ingenuous as ever as Nancy; that Miss Marion Bishop made a pretty Theresa, and hat Miss Helen Ferrers acted with skill and tact as Mrs Huntley. ___

From The Theatrical ‘World’ of 1896 by William Archer (London: Walter Scott, Ltd., 1897 - p.341-342): “SWEET NANCY.” 16th December. On Thursday last Miss Annie Hughes revived at the Criterion, for a single afternoon, Mr. Robert Buchanan’s dramatisation of Miss Rhoda Broughton’s Nancy. When first produced at the Royalty, this clever and really human little play was less successful, I fancy, than it deserved to be. It certainly delighted the audience at the Criterion, where it was acted with excellent spirit. Miss Hughes seems born for the title-part, in which she displays admirable humour, vivacity, and tenderness. Her performance is a genuine and most sympathetic character-creation. Mr. Edmund Maurice was good as Sir Roger Tempest, and the Gray children were capitally played by Mr. Martin Harvey, Mr. Kenneth Douglas, and Miss Beatrice Ferrars. |

|

|

The Stage (11 February, 1897 - p.13) THE COURT So much favour was given to Sweet Nancy on its revival at Miss Annie Hughes’s matinée at the Criterion, on December 10, that its reappearance in an evening bill, with Miss Hughes again in the title character, will be welcome to very many playgoers, more especially when it is preceded by a new play from the pen of Mrs. Oscar Beringer, a writer whose work always deserves careful criticism. Thus the double bill with which Mr. Arthur Chudleigh reopened the Sloane Square house on Monday, February 8, ought certainly to prove attractive, until Easter, at all events. The cast of Robert Buchanan’s adaptation of Rhoda Broughton’s novel is in most respects identical with that of the Criterion matinée, and the interpretation given of this delightful comedy on Monday was such as fully to justify the genuine applause of an emphatically well-pleased audience. We have nothing further to say about Miss Annie Hughes’s charming embodiment of the girlish heroine, her Sweet Nancy being now indeed an impersonation flawless in the blending of childlike candour and sisterly devotion with the keen love and passionate jealousy of a rapidly growing woman. Mr. Edmund Maurice gave again a bluff and manly performance of Sir Roger Tempest; Mr. Martin Harvey as Algernon, Mr. C. M. Hallard as the would-be seducer, Frank Musgrave, and Miss Henrietta Cowen as the downtrodden and submissive Mrs. Gray repeating their excellent portrayals. Miss Beatrice Ferrar appeared on Monday as that lively tomboy, “Tow-Tow,” instead of her sister, Miss Marion Bishop. The character of the mean, intriguing domestic tyrant, Mr. Gray, was assigned to Mr. George Canninge (vice Mr. Charles Rock), who by his make-up imparted a certain oddity to the rôle. Miss Helen Ferrers made the grass widow, Mrs. Huntley, as worldly and superficially fascinating as necessary, other parts being filled by Mr. Hubert H. Short and Mr. Trebel as the younger Gray lads, Mr. Williams as the butler, and Mrs. Campbell Bradley as the housekeeper. Miss Lena Ashwell was succeeded as Barbara by Miss Beryl Faber, a young actress of much culture and high intelligence, whose dignified and sympathetic playing of her important scenes in the last act counted for much in the success of this Court revival. ___

The Saturday Review (20 February, 1897 - pp.193-195) FOR ENGLAND, HOME, AND BEAUTY. “Nelson’s Enchantress.” A new Play in fiour acts, by Risden Home. Avenue Theatre, 11 February, 1897. I AM beginning seriously to believe that Woman is going to regenerate the world after all. ... I wish, for Miss Hughes’s sake, I could confidently predict a long run for “Sweet Nancy” at the Court. When “Nancy” was published I was one of Miss Rhoda Broughton’s admirers; for she was the first novelist who went straight to life for her pictures, taken from the children’s point of view, of the household life of the genteel, impecunious, modern middle-class family, held together only by economic pressure, the family habit, and the common struggle to keep up appearances and conform to conventions. Such children (I was one myself) knew the nobler human relations and wider social duties by name only as appetizing subjects of derision. Miss Broughton distilled the irreverent fun of this into fiction with great humour; but when she wanted to be serious, she had no idea of the tragic scope of her theme, and had to fall back on romance and idealism, with its lumps in the throat, self-pity, separations, misunderstandings, griefs, deaths, and so on. At least it was so in the “Nancy” days: since then I have read no novels of Miss Broughton’s, and hardly half a dozen of any one else’s. [Note: ___

Pick-Me-Up (27 February, 1897 - Vol. XVII, No. 439, pp.342-343) |

|||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||

|

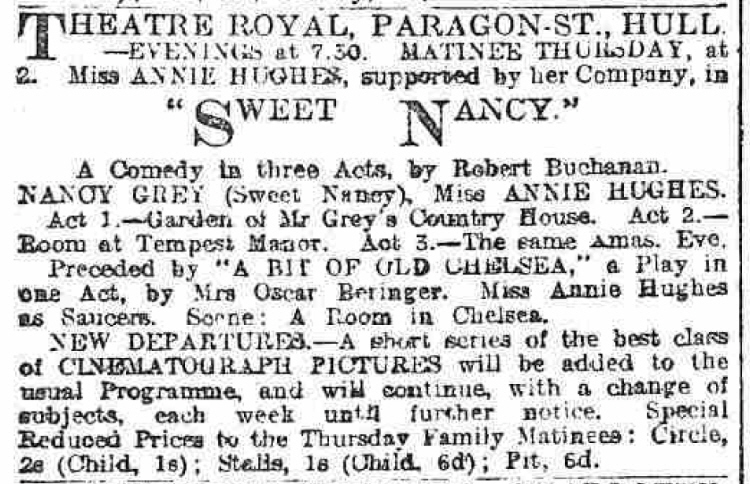

The Morning Post (27 December, 1897 - p.2) Miss Marion Thornhill begins her season at the Avenue on January 6 with Robert Buchanan’s “Sweet Nancy,” which had a successful run at the Court Theatre. In the cast will be found Miss Lena Ashwell, Miss Thornhill, Miss Kate Osborne, Miss May Protheroe, and Miss Annie Hughes; Messrs. Martin Harvey, Havard Arnold, Jarvis Widdicombe, Herbert H. Short, and Mr. Edmund Maurice. Mrs. Beringer’s one-act play, “A Bit of Old Chelsea,” in which Miss Annie Hughes will resume her original part, is to precede the comedy. ___

The Globe (7 January, 1898 - p.6) RE-OPENING OF THE AVENUE. “Sweet Nancy” and “A Bit of Old Chelsea,” with which the Avenue Theatre re-opened, are now accustomed to run tandem, Mrs. Beringer’s clever ;piece being a well-tried leader. In spite of the slightly uncomfortable taste it leaves in the mouth, concerning which, perhaps, too much has been said, it is always welcome, no other piece showing equally well the gifts of Miss Annie Hughes in realistic comedy. The part of “Saucers” in this quaint idyll of the gutter is once more taken by this clever lady, Mr. Edmund Maurice repeating his excellent performance of Jack Hillier. “Sweet Nancy,” to resume our previous illustration, is “between the shafts,” and on her falls the whole of the “collar work.” It may be doubted whether any comedy of modern days has been so frequently revived as this adaptation by Mr. Robert Buchanan of Miss Rhoda Broughton’s pleasing story. Scarcely a season seems to have passed since its production some seven or eight years ago at the Lyric, in which at some house or another it has not faced the footlights. Quite worthy is it of its popularity, and now even it proves to have lost nothing of its power to entertain and delight. It is, in short, a brightly written and thoroughly sympathetic play, which would be the better, perhaps, if its interest at one point were a little less gloomy, but which in most of its scenes is as sunny and inspiriting as it can well be. As Nancy Grey, Miss Annie Hughes first showed us with how much genuine comedy she can lighten the pathos with the possession of which she has long been credited. Her performance retains all its old charm, and was received with much delight. No long time after Mr. Henry Neville “created” the rôle of Sir Roger Tempest Mr. Edmund Maurice succeeded to it. He still gives it a masculine breadth quite suited to the part, and is just the sort of middle-aged man to captivate a young girl’s fancy. The children, the most delightful that in recent days have been put on the stage, are now played by entirely different exponents, among whom Miss Joan Burnett and Mr. Martin Harvey were conspicuous. Miss Lena Ashwell exhibited much grace and a spirit of genuine comedy as Barbara, and Miss Marion Thornhill, the new manager, a lady endowed with great physical advantages, played with much sincerity and power the not too remunerative part of Mrs. Huntly. The revival was received with marked favour, and may be seen with the certainty of delight. The whole, to the lovers of simple and healthy fare, will well repay a visit. ___

The Referee (9 January, 1898 - p.3) Once more the address of “Sweet Nancy” has been changed, and Mr. Robert Buchanan’s very bright and amusing comedy (founded on Miss Rhoda Broughton’s novel), which was summarily withdrawn from the Court last year, was revived on Thursday night at the Avenue. There have been changes also in the company, and Miss Marion Thornehill, to whose enterprise the revival at the Avenue is due, does not sufficiently consider her own interests perhaps in taking a prominent part in the performance. Miss Annie Hughes, the incomparable Nancy of the play since first it was produced at the Royalty, appears again in the leading part of the impulsive, winsome hoyden, married to the old soldier, Sir Roger Tempest, who is played by Mr. Edmund Maurice with a manliness and a sincerity which justify Nancy’s affection for her devoted husband and give the touch of nature to Sir Roger’s fondness for his child-wife. As “Sweet Nancy’s” sweet sister, Miss Lena Ashwell is not less charming, only in a quieter way, than Nancy herself; and the sympathy of the audience is as readily given to the elder sister, who is so very sorely tried. The humours of the young people, in whom the manners of children are illustrated with such fidelity to life, are exceedingly entertaining. There is neither too much nor too little of them. The Bobby of Mr. Hubert Short is a fine specimen of the little pickle; Tow-Tow, too, is a delight, though Miss Joan Bennett, in her glee, is more than a trifle too shrill; and Mr. Martin Harvey, as the youngster, who is neither man nor boy, is the exact cut of a young gentleman in that intermediate stage of life when the tadpole assumes a tail-coat. “Sweet Nancy,” which has never yet had the run it deserves, was received with the welcome ordinarily reserved for a new play. Mrs. Oscar Beringer’s most ingenious, unconventional little piece, “A Bit of Old Chelsea,” is also in the programme, with Miss Annie Hughes again in the part of the poor flower-girl. A touch of extravagance here and there in the acting brings the character at moments perilously near caricature. ___

[Note: |

|||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||

|

[Advert for Sweet Nancy from The Times (28 January,1898 - p.6).]

The Penny Illustrated Paper (29 January, 1898 - p.68) |

|||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||

|

The Guardian (26 September, 1899 - p.8) THEATRE ROYAL. SWEET NANCY. Manchester playgoers already know Miss Hughes’s performance in “Sweet Nancy.” Mr. Robert Buchanan did not make a highly skilful adaptation of Miss Rhoda Broughton’s novel “Nancy.” The play is rather episodic, and unity of purpose is necessarily wanting, particularly after the first act. The points that draw us are those of the story-teller rather than of the dramatist; we see in them the worldly knowledge and sagacity of Miss Broughton, the bias of cynicism that leads her to choose situations always on the verge of the unpleasant, even though they are true and natural and common; and, lastly, we see the unconventionality. Last night we felt that we owed everything to these traits of the novelist that visibly lie behind the work of the adapter, and to Miss Hughes. Nothing else and nobody else mattered. Miss Hughes has many qualities that fit her to present the captivating mixture of Nancy’s character. Nancy is a hoyden and an altruist, a vixen and a devotee, “a pleasant little devil” (in her own phrase) and a sister of mercy. She is a mere child, and the old man who marries her is a natural and obvious foil to her gusty but affectionate caprices. Where Miss Hughes fails is that her purpose is not perfectly consistent. Occasionally a sentence drops that seems detached in tone from the rest, that strikes the ear as a little incongruous piece of insincerity—a burlesque almost of her own manner and the play. Again, a few passages seemed to us to speak rather of a loud young woman than of what Nancy was at her wildest moments—a madcap. But Miss Hughes’s performance was still very pleasant, and never more attractive than when she was being followed about by that unconventional retinue of inquisitive and inconvenient young brothers and sisters. The playing of the rest of the company wanted finish and in most cases experience. ___

The Morning Post (12 December, 1900 - p.3) THE IRVING DRAMATIC CLUB. “Sweet Nancy” is well adapted to representation by amateurs. It portrays characters familiar and dear to us in every- day life, and the succession of light and humorous scenes makes no great demands on dramatic power or acting of serious pretension. In the hands of the Irving Amateur Society Mr. Robert Buchanan’s charming play delighted the audience that filled St. George’s Hall last night, and the success of the company was indeed well deserved. There was a care and finish in the performance unusual in the efforts of amateurs, and a regard to clear pronunciation that made it a pleasure instead of a task, as is so often the case, to listen to the words of the actors. Mrs. Archie Keen played Nancy. She wisely followed in the footsteps of the Nancy with whose memory the comedy will ever be associated—Miss Annie Hughes—but there was no servility in Mrs. Keen’s methods, and though she bears, singularly enough, some facial resemblance to one of our most genuinely comic actresses, her rendering had an individuality and a spirit of its own. The bevy of brothers and sisters who contributed so largely to our enjoyment was a marked feature of excellence, and Miss Nora Wallis Lancaster as Tow-Tow, Mr. Cyril Shepard as Algernon, Mr. Cuthbert Denton as Bobby, and Master Kimbell as “The Brat” were all quite up to the mark. Mr. Leonard Graves, to whom the company owe the first-rate stage management, was the gentle old general, and he presented the character with dignity and pathos. Mr. Percy Varley played the ridiculous father, a part easily exaggerated, and the lovers and minor personages were intelligently represented. Between the acts the orchestra, under Mr. Henry Baker’s baton, performed an unusually pleasant selection of pieces. ___

The Illustrated Sporting and Dramatic News (15 December, 1900 - p.36) DURING its twenty-one years of existence the Irving Amateur Dramatic Club has achieved such a covetable record for good and extensive work that one was not surprised to find the performance of Robert Buchanan’s prettily sentimental comedy Sweet Nancy, given by the club at St. George’s Hall the other evening, in many was quite admirable, and round after round of hearty and spontaneous applause testified the approval of the numerous and fashionable audience which attended. As Nancy, Mrs. Archie Keen played with decision, simplicity, and a vivid appreciation of the pretty wilfulness and wealth of tenderness underlying the character, that were eminently interesting and attractive. She was well supported by Miss Florence Lancaster as Barbara, one of the best moments of the evening being the scene between the two sisters, in act III. after Frank Musgrave’s declaration of love for Nancy. Mr. Athol Stewart as Frank had struck the right key; but his playing would have been the better for a little more assurance. Mr. Cyril Shepard is highly to be commended for an excellent performance as Algy; and as “Tow-Tow” and Bobby respectively Miss Nora Wallis Lancaster and Mr. G. Cuthbert Denton were both admirable. The fascinating, but quietly “cattish” grass widow, Mrs. Huntley, was cleverly played by Mrs. W. R. McConnell; and Mr. Leonard Graves, who bore also a stage manager’s burden, was good as Sir Roger Tempest. Mr. Percy Varley, Mrs. St. Hill, and Miss Helena M. Conrad each contributed very able work as Mr. and Mrs. Gray and Mrs. Pemberton respectively. Altogether the players are to be congratulated on a distinctly satisfactory performance. |

|||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||

|

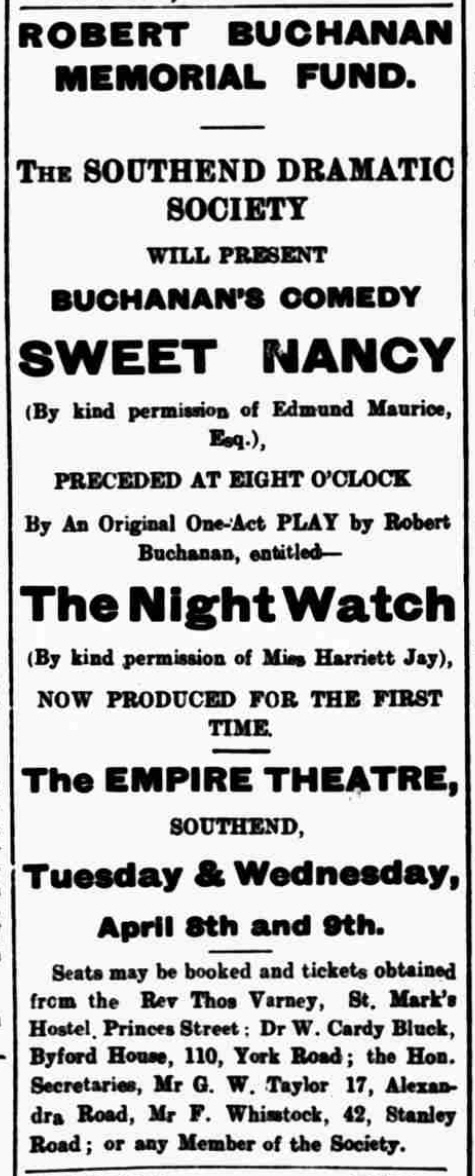

[From The Southend Strandard (3 April, 1902 - p.1).]

The Southend Standard (10 April, 1902 - p.5) SOUTHEND DRAMATIC SOCIETY. “SWEET NANCY” AND “THE NIGHT WATCH.” A FINE PERFORMANCE. Southend Dramatic Society did honour to the memory of a great playwright and, indeed, honoured itself when on Tuesday evening its members realistically pourtrayed at the Empire Theatre Robert Buchanan’s well-known work “Sweet Nancy,” and had the added privilege of placing before the public for the first time a poetical drama by the same writer, entitled “The Night Watch.” “THE NIGHT WATCH.” “The Night Watch,” which began to the tune of the “Marseillaise”—a play in one act—was suggested to Buchanan from a poem by François Coppée. The scene is laid at the Chateau of Grandfief, in Normandy and the time is put at the German Invasion of France in 1870. There are five characters: Irene de Grandfief (Mrs. Reveirs Hopkins); Vicomte de Lisle, a volunteer in the French Army (Mr. Picken); Heinrich von Auerbach, a German Officer (Mr. Sewell); Hubert, a servant (Mr. G. Taylor) and Doctor Marton, a surgeon (Mr. Reveirs Hopkins). Shortly described, this new and powerful play opens with an interior view of the Antique Chamber in the Chateau Grandfief, with Hubert, a clownish servant, looking out of the window, joyfully welcoming the fall of snow; which he wishes would fall quickly enough to swallow up the Germans. His soliloquy is broken by the sound of gun shots and Irene (the heroine) enters. She bids the servant discover the cause of the firing. While he is gone the lady’s thoughts dwell on the whereabouts of her soldier lover, the Vicomte, who is serving as a volunteer with the French Army. His expected letter has not arrived and in the passion of her love she kneels before the oratory praying “Spirit of Heaven spare him! Restore him in the blessed light of peace and bring him soon!” Hubert hastily enters and brings the news that a skirmish near by had ended in a victory for the French and the capture of a German Uhlan officer. Dr. Marton dresses the wound and is afforded opportunity of declaring the Vicomte to be “he who yielded rank, wealth, and privilege and seized a sword in France’s hour of danger”—an act which would peculiarly appeal to Buchanan’s instincts. Irene nurses the Uhlan through the night and a phial of medicine is given her in order that she may serve him with ten drops four times an hour, so to keep him alive. The officer rouses from unconsciousness ad tells Irene how “yonder in Germany there is one who waits like her; a little maid with sunny, golden hair.” The climax is reached when he tells her that a month ago at Metz he killed a Frenchman: “We saw one standing as a sentinel. On hands and knees I crept unto him. Then, up-springing, stabbed him. He fell with scarce a groan.” The dying Frenchman implored his assailant to forward to the one he left behind a medallion which he wore. This Auerbach swore to do and he now hands it over to the girl to fulfil the mission. She examines it and finds it to be her lover’s. Then through the long night hours she struggles with her frenzied desire to kill the sick man, but a low voice points her to her “Duty!” and she administers the saving draught. As he recovers, Raoul, the missing lover, pale but eager, enters and clasps the girl in his arms and peace is made ’twixt Gaul and Teuton. “SWEET NANCY.” “Sweet Nancy” runs to a livelier, merrier measure and the audience were at once in good humour with the first scene, wherein are found the sons and daughter of Mr. Gray (Mr. Reveirs-Hopkins) playing in approved tom-boyish fashion in a garden, until disturbed by their father. The sons were: Algernon Gray, Mr. Felis Seel; Bobby Gray, Mr. Fred Whisstock; James Gray, called “The Brat,” Master A. E. Lockington and the daughter, Teresa Gray, called “Tow, Tow,” Miss Dora Seel. Sir Roger Tempest (Mr. William Gray) quells a stormy scene between father and children and Mrs. Gray (Mrs. Read) also appears. “Nancy” (Mrs. Reveirs Hopkins) was greeted with cheers and she was pretty and girlish with her match-making father when he wanted her to lunch with him and Sir Roger “dressed in her best.” The obvious object of the ruse was quickly penetrated when she was chaffed by her brothers and sisters, who, with a keen eye to the main chance, bargained for shooting and hunting as their share of the spoil from the prospective union. The situation was, indeed charmingly amusing when Sir Roger discovered “Sweet Nancy” left stranded on a high wall by her mischievous brothers, but where, however, she progresses extremely well in her determination to marry a man with money and she and Sir Roger go in the fashion of “Darby and Joan” to lunch, preceded by Barbara (Mrs. W. Cardy Bluck) and Frank Musgrave, Sir Roger’s ward, (Mr. Donald Gray). The courtships cause great dismay among the children and Algernon gives his emphatic opinion upon the subject, preluded by the dramatic “Friends, Romans, countrymen—stand to attention!” In due time Sir Roger sues for Nancy’s hand and if the latter is seemingly coy, her secret intention is realised and she gives her promise. With seductive guile she gains the boys over to the alliance by promises of hunters and shooting galore. Scene 1 was most effective and the curtain descended to the hearty cheers of the audience. ___

The Cheltenham Looker-On (19 October, 1907 - p.15) Sayings and Doings of Cheltenham. THE HOYDENISH part of “Sweet Nancy” in Robert Buchanan’s charming comedy of that name is well within the compass of Miss Annie Hughes’ particular style of acting—gay, lively, and anon serious enough, and that lady is much in evidence during the progress of the play which is being presented at the Opera House this week. The story is by no means novel, neither is the plot a strong one; yet it is brightly, and in some parts brilliantly, told. Miss Hughes has played in the piece over a thousand times, and she invests the title role with a charm and vivacity which delights all who see her. The part of “Nancy’s” middle-aged soldier husband, “Sir Roger Tempest”—during whose absence in South Africa occurs the unpleasantness of which “Nancy” is the innocent victim—is well taken by Mr. Rupert Lister; and, indeed, all the characters (especially those of “Teresa Grey,” and the irrepressible “Brat,” by Miss Dundas Slater and Miss Norah Vernon) are in capable hands. The comedy, which is preceded by a one-act play, “After Many Years,” written by Miss Hughes, is well produced and mounted. Last evening “Miss Tommy,” with Miss Hughes in the name-part, was successfully produced. There will be a matinée of “Sweet Nancy” this afternoon. |

|||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||

|

|

[Advert from The Hull Daily Mail (17 February, 1908 - p.4).] |

|

|

Next: The English Rose (1890) Back to the Bibliography or the Plays or Harriett Jay Theatre Reviews

|

|

|

|

|

|

|