ROBERT WILLIAMS BUCHANAN (1841 - 1901)

|

ROBERT WILLIAMS BUCHANAN (1841 - 1901) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

RANDOM CUTTINGS

The Cornhill Magazine (August, 1868 Vol. 18, pp.244-248) From ‘Anarchy and Authority’ by Matthew Arnold. But if we still at all doubt whether the indefinite multiplication of manufactories and small houses can be such an absolute good in itself as to counterbalance the indefinite multiplication of poor people, we shall learn that this multiplication of poor people, too, is an absolute good in itself, and the result of divine and beautiful laws. This is indeed a favourite thesis with our Philistine friends, and I have already noticed the pride and gratitude with which they receive certain articles in The Times, dilating in thankful and solemn language on the majestic growth of our population. But I prefer to quote now, on this topic, the words of an ingenious young Scotch writer, Mr. Robert Buchanan, because he invests with so much imagination and poetry this current idea of the blessed and even divine character which the multiplying of population is supposed in itself to have. “We move to multiplicity,” says Mr. Robert Buchanan. “If there is one quality which seems God’s, and His exclusively, it seems that divine philoprogenitiveness, that passionate love of distribution and expansion into living forms. Every animal added seems a new ecstasy to the Maker; every life added, a new embodiment of His love. He would swarm the earth with beings. There are never enough. Life, life, life,—faces gleaming, hearts beating, must fill every cranny. Not a corner is suffered to remain empty. The whole earth breeds, and God glories.” ’Tis the old story of the fig-leaf time— this fine line, too, naturally connects itself, when one is in the East of London, with the idea of God’s desire to swarm the earth with beings; because the swarming of the earth with beings does indeed, in the East of London, so seem to revive— . . . the old story of the fig-leaf time— such a number of the people one meets there having hardly a rag to cover them; and the more the swarming goes on, the more it promises to revive this old story. And when the story is perfectly revived, the swarming quite completed, and every cranny choke-full, then, too, no doubt, the faces in the East of London will be gleaming faces, which Mr. Robert Buchanan says it is God’s desire they should be, and which every one must perceive they are not at present, but, on the contrary, very miserable. [Note: ___

The Edinburgh Evening Courant (22 November, 1869 - p.5) MR ROBERT BUCHANAN, the poet, according to the Sunday Times, is completely incapacitated for his literary avocations by a brain affection, entirely the result of over-exertion.—[It will be observed that a contradictory account of Mr Buchanan’s health is given by the Daily Mail.] ___

The Edinburgh Evening Courant (23 November, 1869 - p.2) THE Mail denies that Robert Buchanan, the poet, is so ill as has been represented. Mr Buchanan is never idle in his professional work, “which” says our contemporary, “he varies by shooting daily over his moors.” _____

The Aberdeen Journal (14 February, 1872 - p.6) |

|

|||||

|

The Standard (29 December, 1873 - p.5) THE LITERATURE OF THE YEAR. . . . ... The Laureate has been silent during the year, if we except a graceful appendage to the “Idylls of the King,” in the shape of an address to her Majesty; but his precise merits have been more than ever a subject of contention among the critics. A tendency has been manifested excessively to decry a poet who was at one time perhaps excessively extolled; but calm judges will not allow themselves to be swayed, by a not altogether unnatural reaction, into denying or doubting Mr. Tennyson’s rare gifts and graces, or the valuable and permanent addition his works are to English poetry. We think, too, that along with the reaction alluded to, a taste is springing up again for verse of a more objective sort than that which has been exclusively in favour for the last thirty or forty years. It may be that emotional analysis is exhausted, or that the human heart is getting weary of being dissected so perseveringly; but a growing disposition to hail poetry which is narrative rather than reflective is apparent. Mr. Robert Buchanan’s “Red Rose and White” has met with a warm reception, whilst the public has turned coldly from Mr. Browning’s “Red-Cotton-Night-Cap-Country,” of which his keenest admirers could say little by way of praise. ... ___

The Leicester Chronicle and Leicestershire Mercury (7 March, 1874 - p.5) |

|||||

|

|||||

|

The York Herald (8 April, 1874 - p.3) |

|||||

|

|

The York Herald (11 June, 1874 - p.7) |

|

|

The Hastings and St. Leonards Observer (8 August, 1874 - p.7) The Gentleman’s Magazine contains in a poem, entitled “Love in Winter,” as exquisite a piece of poetry as its gifted author, Mr. Robert Buchanan, ever wrote, and we shall be greatly mistaken if this be not the opinion of the critics generally. ___

The Era (23 August, 1874 - p.3) THE GENTLEMAN’S MAGAZINE FOR AUGUST falls a little below the usual mark; but there are, nevertheless, several good papers. ... Mr. Robert Buchanan used to be a decent poet, but his flirtation with the Muses this month leads but to indifferent results. ___

The Oban Times (10 November, 1877 - p.4) ROBERT BUCHANAN THE POET.—A number of the students of St Andrews University have (says the correspondent of the Manchester Courier) resolved to nominate Mr Robert Buchanan, the poet, to the Lord Rectorship. Mr Buchanan is well known personally in the West Highlands. Oban was his headquarters for a year or two, and from it he made several excursions to the islands by sailing yacht and steamer. ___

The Greenock Advertiser (29 July, 1878 - p.3) MAN OF THE WORLD NOTES. A distant contemporary of ours remarks pathetically:—“With the exception of delinquent subscribers everything is about a fortnight earlier than usual this year.” The three tailors of Tooley Street have left some sturdy and remarkable successors behind them. The petition ever praying for the arrest of Lord Beaconsfield emanates from an inspired coterie in a village called Keighley. The insect-destroying advertisers now invite attention to their wares by publishing four lines of poetry descriptive of the virtues of their mixture. The poetry is said to be the work of that estimable Scotch bard, Mr Robert Williams Buchanan. ___

The Referee (13 January, 1884 - p.3) Mr. Robert Buchanan is ill, and somebody says he is quite delirious. I am by no means surprised to hear it. ___

Truth (26 August, 1886 - p.11) The law respecting indecent publications seems to be in about as unsatisfactory a condition as could well be imagined. The other day Mr. Curtis Bennett said that he was quite incapable of judging whether a certain leaflet was unfit for publication or not, as the majority of three-volume novels, which appeared with impunity, were, in his opinion, infinitely worse. Again, at the Mansion House last week, Alderman Lusk fined a boy 10s. for selling an indecent print, whereas for precisely the same offence another lad was fined forty shillings by Alderman Cowan at the Guildhall. And in neither of these two cases were any proceedings whatever taken against the real offenders—namely, the authors and publishers of the leaflet in question. If the police are so zealous in the cause of morality, why do they not institute a prosecution against Mr. Robert Buchanan and Mr. George Moore, instead of wasting all their energies upon the ragamuffins who vend nastiness in the gutter? ___

Edinburgh Evening News (20 January, 1887 - p.3) ACTORS’ HOBBIES. Most actors have hobbies. Mr Irving’s is to preserve all the dresses he has appeared in, Mr Wilson Barrett’s is to be photographed continually “life-size,” Mrs Langtry’s is fencing, Sarah Bernhardt’s is to sleep in a coffin (provided there are people to look on), Miss Harriet Jay, the novelist-actress’s, is to wear boys’ clothes at home, Miss Minnie Palmer’s is to collect stockings, of which she carries about with her several hundred pairs; Miss Maude Branscombe’s is to run races. Once Miss Branscombe was out walking in the country, when she heard shouting behind, and turning round saw a number of schoolgirls racing down the road. They were part of a Sunday school picnic engaged in a race, and it was more than Miss Branscombe could do not to join in. She came in first, and was presented with the prize, a gold-headed pencil case, before it was discovered that she was an interloper. Mr Penley’s hobby is to kill insects. He has prepared for this on the most extensive scale by building a greenhouse, in which he has placed a number of fine plants, on the supposition that where there are plants insects are sure to gather. Then Mr Penley sits in his greenhouse in an armchair smoking, on the supposition, again, that tobacco smoke kills insects. ___

Buxton Herald and Gazette of Fashion (9 February, 1887 - p.2) LONDON LETTER. |

|||||||||||

|

|||||||||||

|

Aberdeen Evening Express (17 May, 1887 - p.2) ROBERT BUCHANAN AS A CRITIC. A sharp American critic in the latest number of “Book Chat,” describes Robert Buchanan, in his critical writing, as “a man who cries aloud for freedom of thought, and then attacks everyone who thinks differently from himself.” The same writer adds:—“He is the sort of man who would walk down the halls of the ages, stand before Shakespeare, bend down to him as would be necessitated by his own superior height, pat him in a friendly way on the head, and say, ‘Fear not, William; I will take care of you.’” ___ Aberdeen Evening Express (16 October, 1888 - p.2) Mr Robert Buchanan, poet, novelist, essayist and dramatist, contributed recently to the “Academy” a glowing panegyric on Lester Wallack. At one period of his career Buchanan sought protection from a clique of hostile critics by publishing his productions anonymously in America and elsewhere, a course which provided the following amusing story:— ___

St. James’s Gazette (17 April, 1889 - p.5) |

|||||||||||

|

|||||||||||

|

Aberdeen Evening Express (11 September, 1890 - p.2) ROBERT BUCHANAN’S NAMES. Mr Robert Buchanan keeps a record of the ill-names that have been given to him. He says that he has been called a pretentious poetaster, a costermonger, an idyllist of the gutter and the gallows, a viper, a village donkey, a scrofulous Scotch poet, an enemy to decency, a Chadband, a moral person, an immoral person, a fraud, a dirty Jacobin, a defender of vicious literature, a Bowdleriser, a worm, a thing that eats dust, a green-eyed monster, a failure, a successful imposture, a slave of convention, an enemy of society, a prig, a learned pig, a critic with a wooden head, a thief, a plagiarist, a reptile, an ignoramus, a crawling cur, a liar, a botcher and a tinker, and so on ad infinitum.” ___

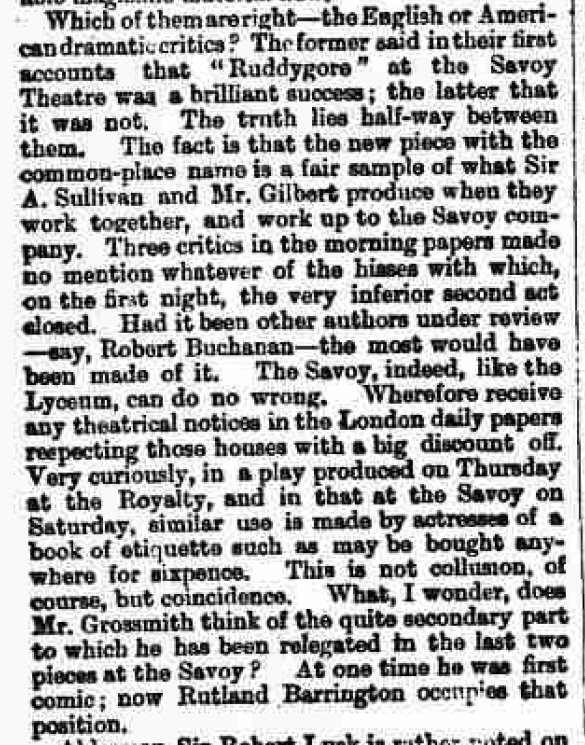

The Era (13 September, 1890) |

|||||||||||

|

|||||||||||

|

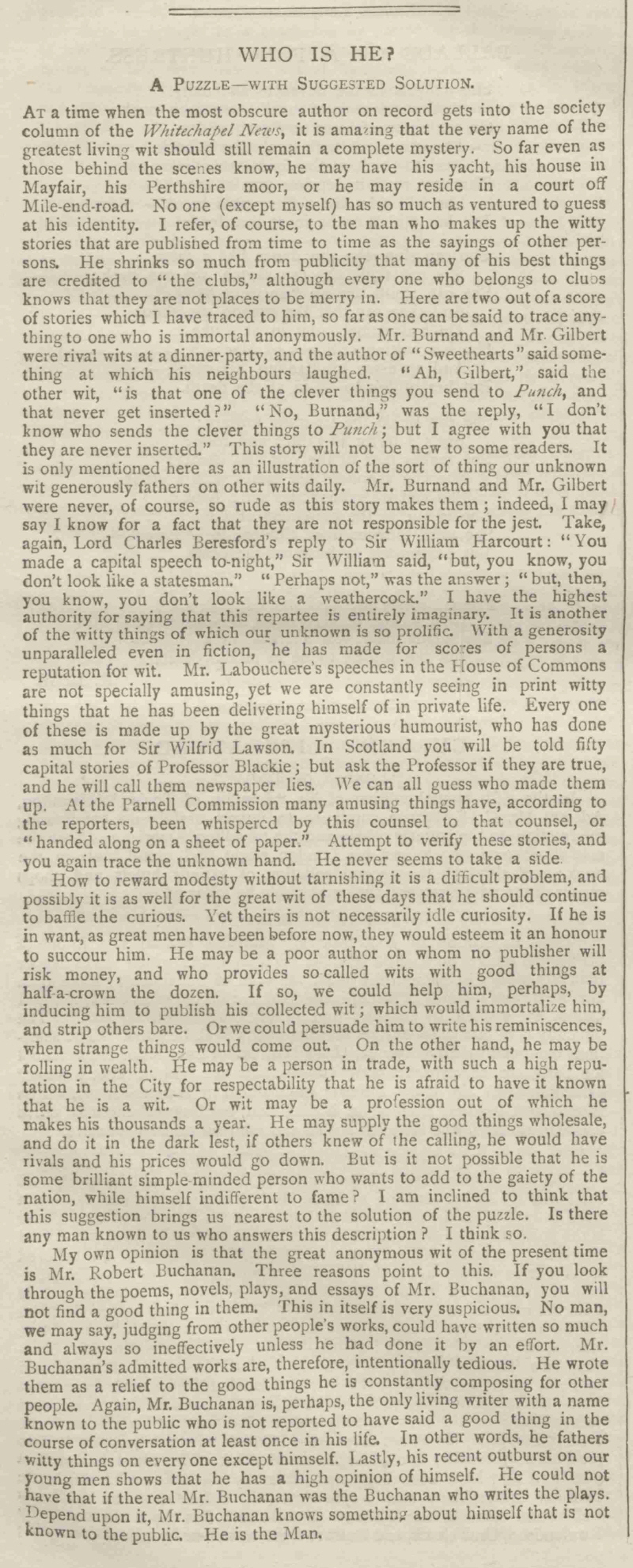

The Referee (28 September, 1890 - p.3) |

|||||||||||

|

|||||||||||

|

[Note: ___

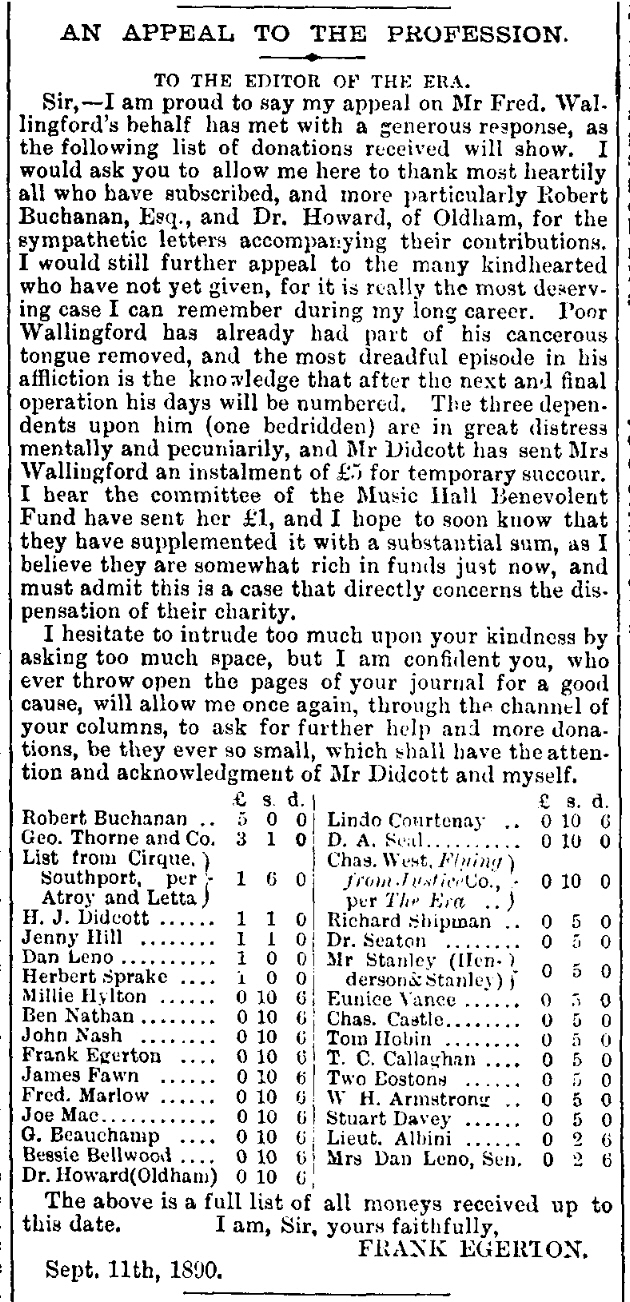

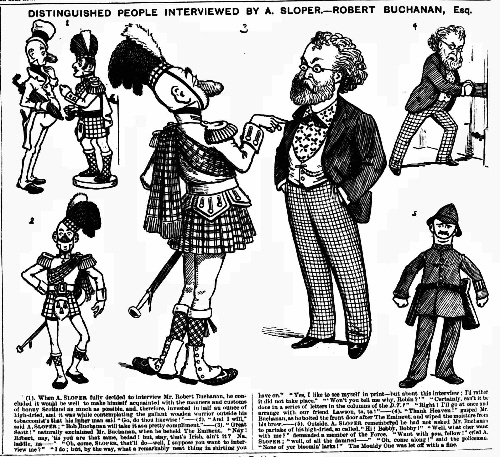

Ally Sloper’s Half Holiday (25 October, 1890 - p. 4) |

|||||||||||

|

|||||||||||

|

Blackburn Standard (1 November, 1890 - p.2) LADY SMOKERS. Another masculine advancement on the part of ladies is smoking; and not only amongst those who are, or wish to be thought, fast—but with a number of Royal, and highly born ladies. We remember our ideas of women-smokers as a child being that they consisted only of terribly coarse old Irish women with a clay pipe—being familiar with a spectacle of an old dame of this description who used to solicit alms at one of the West-end crossings, the pipe being enjoyed when she thought herself unobserved, and concealed under her plaid shawl, from which a mysterious (to the uninitiated) wreath of smoke curled; when any likely bestower of charity appeared approaching—but this primitive idea has long evaporated like the smoke itself. “The Cigar and Tobacco World” states that the several Queens of Portugal, Greece, Belgium, Italy, Spain, and Wurtumberg, all smoke cigarette and mild cigars, and nearer home the Marchioness of Lorne, and the Princess of Wales and her daughters also indulge in cigarette in the seclusion of their morning rooms, though the Queen hates smoking in any form. Many literary ladies smoke, Miss Harriet Jay and Miss Emily Faithful to wit. Perhaps for brain work the soothing weed may be excused to some extent; but though, without any logic, possibly, it seems right enough for a man, and we always feel there is something dubious somehow about a man who does not smoke, or drink in moderation—we cannot quite reconcile the idea of a cigar or cigarette between the lips of our English girls and women without feeling that the poetry and refinement associated with our ideal of womanhood, is getting unpleasantly jostled. ___

The Manchester Weekly Times (19 December, 1890 - p.6) AFTERNOON CHAT. (BY OUR LADY CONTRIBUTORS.] . . . The most charitable and good natured amongst women are certainly actresses: perhaps their methods of giving are not always wise, or such as would receive the approbation of the Charity Organisation Society, or our Puritan forefathers; still, the spirit of true generosity is there. Thus Letty Lind, Harriett Jay, and little Minnie Terry have been lending their services this week at a private bazaar, in aid of the Middlesex Hospital. No one could say it was a dull bazaar, and it must have been successful, for the money was simply charmed out of your pockets in the most irresistible way. All the stallholders were got up in pretty fancy costumes, and there was no shyness about them or lack of “go.” If there came a pause they would start a sweepstake for a recitation, and then the refreshment room was thoroughly well furnished, and smoking was permitted. To contrast this bazaar with one opened at Richmond last week by the Duchess of Teck is to prove conclusively that no one ought to be allowed to hold a stall, or to try to sell, at these functions unless she is self-possessed, and has a little verve and fun in her composition. It is not the prettiest woman who becomes a society beauty; it is the pretty woman with a talent for chatter and a certain savoir faire. So it is no use to put a beautiful but stupid girl in charge of a stall at a bazaar: in these cases wits count for more than they are usually considered worth. ___

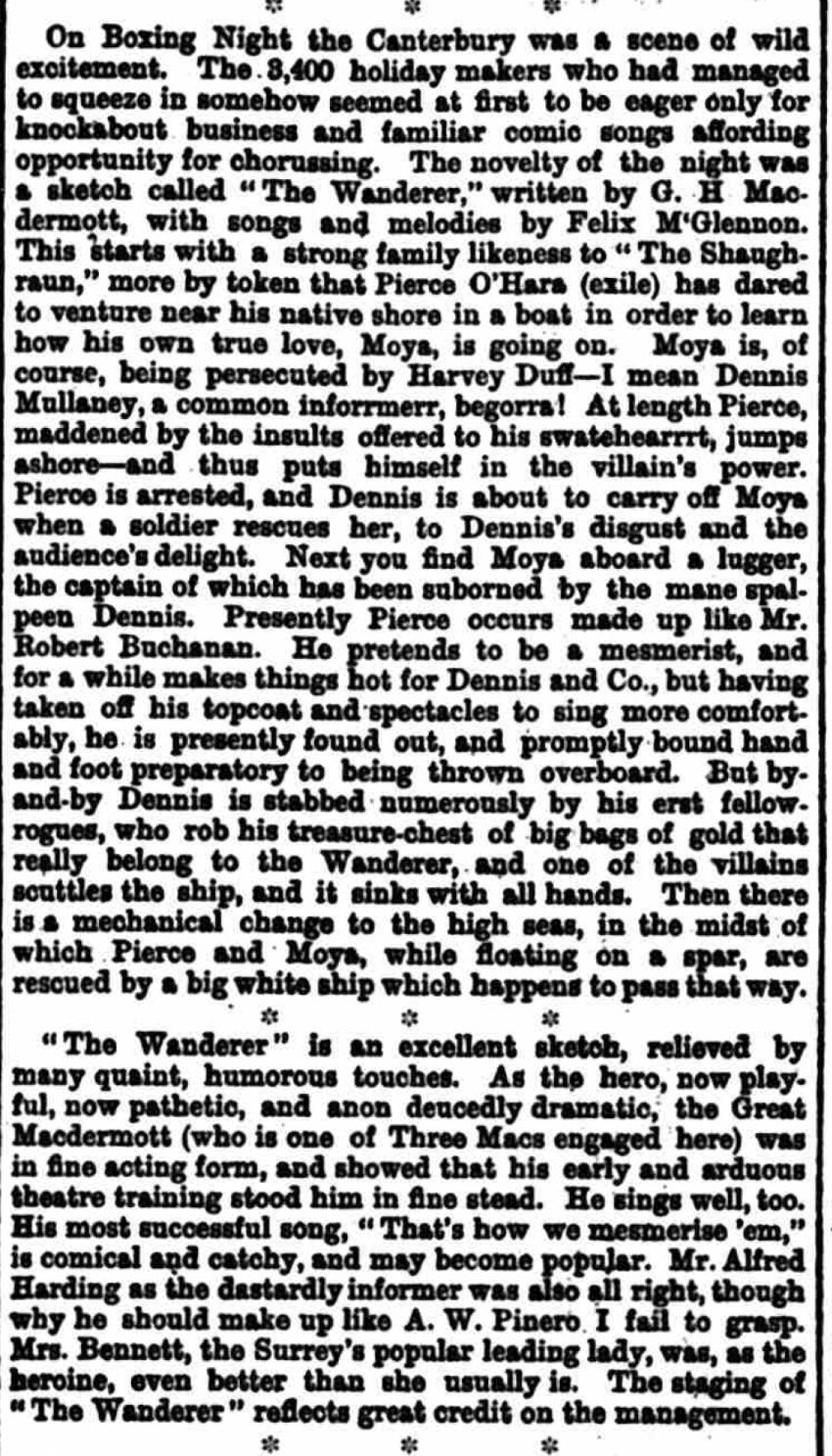

The Referee (28 December, 1890 - p.2) |

|||||||||||

|

|

[Note: No mention of Buchanan, but Zæo’s in there.] |

|||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||

|

The Sporting Life (27 January, 1891 - p.1) “ALL THE COMFORTS OF HOME” AT The large audience which favoured Mr. Norman Forbes on Saturday night by attending the inauguration of his management of the Globe Theatre audibly expressed their pleasure at the important changes which had been wrought during the recess. ... ___

Aberdeen Evening Express (8 August, 1891 - p.2) [An item on a proposed Victorian Exhibition with Robert Buchanan mentioned among the “conflicting mediocrities”.] |

|||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||

|

Pick-Me-Up (10 October, 1891 - Vol. VII, No. 158, p.18) The two best advertised things in the country appear to be Pears’ Soap and Mr. Robert Buchanan. While the soap is justly celebrated for imparting a good complexion to the general countenance, Mr. Buchanan is best known by his perennial and heroic efforts to whitewash his own works and to tar and feather—in a nauseous tissue of Buchananese abuse—all those who may not have happened to like the looks of ’em. The aspiration of the hypertrophied infant for the familiar 3½d. tablet is as nothing to the strength and speed of Mr. Buchanan’s desire for notoriety. He rose to a certain flashy fame by the method (better known in science than in literature) of attacking bigger men than himself; that is to say, men of at least average mental stature. The position thus gained was only a spring-board, a point de départ, for further wild leaps into the hysterical inane, for further instances of the audacity which is not a virtue. But as Mr. Buchanan’s egotism has become more pronounced, he naturally finds his stock of “bigger men” fail him. And so he can devote more attention to the lapses of little men, of critics, for instance, who have read his books without being overwhelmed by the resemblance in them to Goethe, Dante, Virgil, Molière, Swedenborg, Plato, Shakespeare, and the Holy Scriptures. The resemblance—he is always ready to assure them—is there; and were they not purblind creatures at best, they would see it and worship accordingly. All which is very strange and wonderful; almost as strange and wonderful as it is to find a respectable paper like the Echo lending itself to the advertising purposes of such a well-known practitioner as Mr. Buchanan. ___

Ally Sloper’s Half Holiday (17 October, 1891 - p. 6) THE Mildewed and Moth Eaten Edifice has been pleased to confer the “Sloper Award of Merit” upon MR. ROBERT BUCHANAN, because he’s done so much to elevate the British Drama. “In my humble opinion, feyther,” commenced the Blue Eyed Pigeon, “Robert is a Big Chief, and I’m positively amazed that you have not spotted him for an F.O.S. long ere this. It only shows how thoroughly hignorant——” But at this point the peroration was cut short and the rolling-pin séance commenced. ___

Truth (17 December, 1891 - p.35) I doubt, though, if even from the steps of the Burlington Arcade Mr. Walter Sickert’s so-called portrait of Mr. George Moore would look like anything but a grotesque and ill-natured caricature. It is a picture which Mr. Robert Buchanan may very possibly have gloated over; but which the average visitor to the Dudley Gallery will be apt to resent as an outrage, which even an Impressionist should have been slow to perpetrate. ___

The People (25 September, 1892 - p.4) THE ACTOR. If there is anything more tiresome than reading novelists’ reasons for not writing plays, it is reading playwrights; descriptions of the mode in which they produce their works. The reason why certain novelists don’t write plays, is because they can’t or don’t want to; as for the making of plays, every playwright has his method, and, such as it is, he is not likely to reveal it wholly. ___

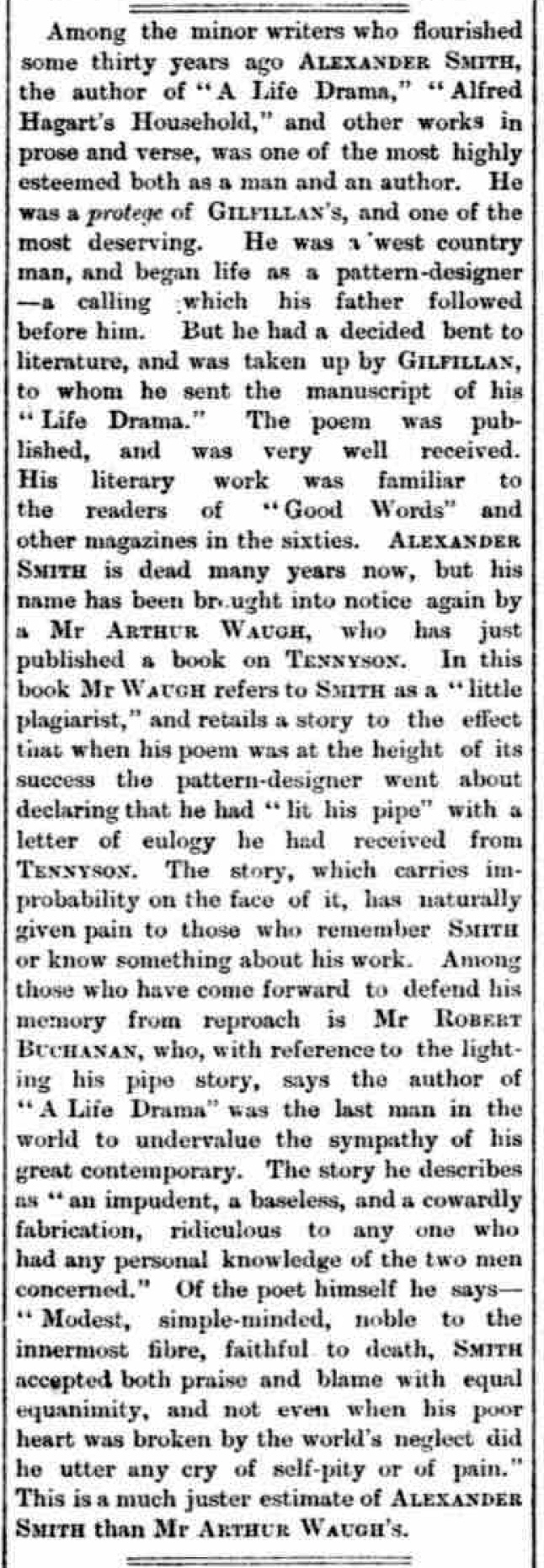

The Dundee Evening Telegraph (11 November, 1892 - p.2) [Extracts from a letter of Buchanan’s on the subject of Alexander Smith, from an unnamed paper.] |

|||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||

|

The Glasgow Herald (11 November, 1892 - p.11) [A letter from William Hodgson on the same subject, which mentions Robert Buchanan Snr. and Jun.] |

|||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||

|

The Glasgow Herald (16 December, 1892 - p.7) |

|||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||

|

The Dover Express (28 April, 1893 - p.6) |

|||||||||||||||

|

|

So far, no more information about Kate Lloyd-Jones, although I did come across this in The Co-operative News of 4th February, 1888 and I should imagine that this Lloyd Jones is the old newspaper business partner of Robert Buchanan Snr. |

|

|

The Boston Daily Globe (24 June, 1893 - p.4) Robert Buchanan, the Scotch poet and playwriter, prints this remark: “I have known only two really sane men in my life, Walt Whitman and Herbert Spencer.” All the other people of his acquaintance are flighty. We must hope that Buchanan himself isn’t rattled, hasn’t gone crazy, hasn’t lost his senses, isn’t moonstruck, hasn’t a screw loose In his head, never talks giddily, and is really sane, without even a touch of corybancy.—[Editor Dana.] ___

The Bazaar, Exchange and Mart, And Journal of the Household (30 August, 1893 - Vol. XLIX, p.550) THE LITERARY WORLD. . . . The next volume of Mr. Walter Scott’s excellent “Canterbury Poets” is devoted to a collection of contemporary Scottish verse by Professor Blackie, Andrew Lang, R. L. Stevenson, and “others,” as the stereotyped newspaper announcement has it. We do not know whether Robert Buchanan, who is Scotch enough in all conscience, is included in the “others,” but his name is not specifically mentioned. Not only in our opinion, but in that of many—not to say most—present-day critics, Mr. Buchanan is the best living poet of Scottish nationality, and head and shoulders above the three persons mentioned. They have their merits in their particular line of literature no doubt, but as poets they do not shine with any great lustre. Mr. Lang can write pretty dedicatory verses—sometimes; Professor Blackie is a Greek scholar and author of philosophical works first and a poet afterwards; and R. L. Stevenson is a novelist than whom there is none better living—his “Child’s Garden of Verses” and other poems are superior, but not works of genius by a long way. ___

The Glasgow Herald (28 September, 1893 - p.7) |

|

|

The Edinburgh Evening News (21 November, 1893 - p.3) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|