|

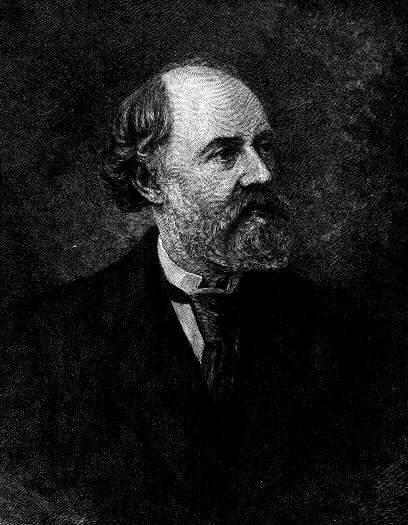

CHARLES READE.

From the painting bequeathed by Mr. Reade to Messrs. Harper and Brothers.

CHARLES READE:

A PERSONAL REMINISCENCE.

19 ALBERT GATE, Knightsbridge, London, is one of a row of old-fashioned houses facing southward across a cab- rank to the opening of Sloane Street, and northward to the ride in Hyde Park. It is rather a gloomy-looking dwelling, with a narrow slip of garden in front, and a longer and broader slip in the rear; but within it has cozy possibilities, and from the garden in the rear one can watch the long procession of fashion coming and going any afternoon during the season. Along the piece of wall beneath the front railing there used to run, painted in huge white letters, the curious inscription:

NABOTH’S VINEYARD,

the name given to the house (when its very existence was threatened by a bill surreptitiously smuggled into Parliament) by its owner, Charles Reade.

Here for many years Charles Reade lived, studied, wrote, and entertained the few friends he loved. Dreary and mean as the place looked from without, it was pleasant enough inside, the pleasantest room of all being the big study, or literary workshop, in the rear, carpeted, and full of great mirrors reaching from floor to ceiling, in front of which were India- rubber trees in pots; adorned with two or three paintings (the most noticeable, at a cursory glance, one of a pierrot rescuing an infant from a fire), scarlet curtains, and pieces of marquetry; and opening through glass doors on the quiet back garden. At a large writing-table close to the fire-place and facing the window sat the famous novelist, with great books of memoranda at his feet, and by his side plated buckets brimming with correspondence. It was here, too, that he generally dined, or held high wassail on festive occasions; and light and cheery it was indeed when the curtains were drawn, and the innumerable wax candles, used in lieu of lamps or gas, were burning on every point of vantage. From this sanctum sanctorum went forth the copious correspondence, the fulminations against injustice, the epistolary diatribes, which made the name of Charles Reade a household word. The stranger, entering it in fear and trembling, and expecting perhaps to find a truculent and savage figure, was soon relieved on perceiving a loosely clad and mild-mannered elderly gentleman, with soft brown ox-like eyes, gray hair, and a placid smile, ever eager to help him if he had a grievance, and ready to advise him, in any case, with old-fashioned kindness and courtly grace. But if the new-comer were a friend, one of the initiated, the brown eyes would become beaming, the smile merry, and the gentle host would show himself as what he was in reality—a man with the great heart and simple tastes of a school-boy, ripe for any sport that was innocent and merry, and content “to fleet the time carelessly, as they did in the golden world.” He would refresh himself, too, like a school-boy, with cakes of all kinds, cocoa-nuts, and sweet confections manufactured by Duclos. “Charles,” his loving housekeeper would cry, “leave those sweets alone—you’ll make yourself ill.” “Quite right, Seymour,” he would reply, munching a bonbon with infinite relish; “take them away.” He had not even arrived at the point of culture, or indigestion, which desiderates dry champagne, but was quite a young lady in his appreciation of saccharine vintages. He abominated tobacco. His idea of an orgy was a feast of sugar-plums. His ideal of feminine perfection was a fresh young English girl. One of his favorites, known to him and others as “The Queen of Connaught,” complained to him on a certain occasion that the sun was spoiling her complexion. “Not at all, my dear,” he answered; “you look like a nice ripe pear.”

As I think of him now, when the grave has just closed over him, and when he has done forever with all the misconceptions of the world, what lingers with me most is the picture of him in these simple and child-like moods. His sweetness of disposition, his kindly frankness, his love of all that is sunny and innocent in human nature, his utter absence of literary arrogance, were qualities peculiar to him, and unique in a generation of shams and pretenses. He had little or no interest in mere literature or merely literary people, but his fascination for all forms of genuine life, from the highest to the lowest, was deep and abiding. What he sought invariably to get out of a man was, not what he fancied or what he dreamed, but what he knew. Supremely veracious and sincere himself, he hated falsehood and insincerity in others, and that soft brown eye of his was lynx-like in detecting a prig or a bore. It was easy enough to tell when he was bored: he bottled himself up, so to speak, and presented a countenance of serene yet dogged vacuity; and I have known him to sit thus, to all intents and purposes dumb as a mole and deaf as a post, for a whole evening together. I am afraid I must add that this demeanor invariably thawed before a pretty face. Under that charm all his ice melted, and he showed himself as he was—delightful, a gray-haired boy.

The occasion of our first meeting was peculiarly interesting to me. A near relation of mine, Miss Harriet Jay, then a very young girl in her teens, had published an anonymous novel, The Queen of Connaught, which had been attributed in many quarters to no less a person than Charles Reade himself. Far from resenting the blunder, and quick to perceive the fruit of genuine and unique experience, Charles Reade had evinced the greatest curiosity concerning the real author; and so it came about that an introduction took place at the rooms of a genial actor and manager, and a life-long friend of Reade’s, Mr. John Coleman. It was a merry meeting, the first of many, and from that time forth the young authoress and the famous author were close friends. A little later, when we proposed to dramatize The Queen of Connaught for the Olympic Theatre, Charles Reade informed us that he had once conceived the idea of doing it himself, and showed us, pasted in one of his enormous Indexes, a long review which he had cut from the Spectator, and indorsed in his own handwriting with these words, “Good for a play.” When our manuscript was ready, and accepted at the theatre, we took it down to “Naboth’s Vineyard” and read it to Naboth; and I well remember how, at a certain situation in the fourth act, he leaped to his feet, clapped his hands, and insisted on “toasting” that situation in a bumper of champagne. Nor was this all. When the rehearsals began he came down to the theatre more than once, and gave us the benefit of his advice and great experience, even to the extent of personally rehearsing a “terrific struggle” between the hero and the villain of the piece. The piece ran over a couple of months, and was succeeded by a drama of his own, The Scuttled Ship.

Something may be said here, not inappropriately, of his connection with the stage. Dramatic writing was his hobby; he loved it with all his heart and soul; and he loved it none the less because he was again and again defeated in his efforts to attain success. It was George Eliot’s ambition to be recognized as a poet; it was Charles Reade’s to triumph as a dramatist. In neither case was the wish completely granted. When the drama of Never too Late to Mend was first produced, it was a comparative failure, and it was only in after-years that it became successful, and repaid its author for the labor and anxiety bestowed upon it. When Reade essayed theatrical management for the purpose of bringing out his own pieces, he invariably lost large sums of money. His one great financial success came late in life, in Drink, a free adaptation of L’Assommoir; and so little was this success anticipated that a couple of days before the production, when I called upon him, he prophesied the dreariest of failures. “Yes, Charles,” echoed Mrs. Seymour, who was sitting by, “I wish to Heaven you had never touched the thing.” When the night of production came, his faithful friend and housekeeper was too unwell to be present. Before the curtain rose I met him in the theatre lobby. He was walking wearily, looking very worn and old, and when I wished his new venture “godspeed” he shook his head sadly. “Seymour is too ill to come. It is the only ‘first night’ of mine at which she has not been present; so I don’t look for good luck, and indeed I don’t much care.” Contrary to all expectations, Drink made an instantaneous popular success; but, alas! it brought little or no joy to its adapter, for the illness of his faithful adviser and companion was only the beginning of the end.

The reader of Harper’s Magazine, though familiar with the name and works of Reade, may require to be reminded that lie lived and died a bachelor, and that the Mrs. Seymour of whom I have more than once spoken was his housekeeper for many years. When he began to write plays she was a popular actress, and thus they were brought together; and presently he went to reside with her, her husband (who was then living), and two other friends and lodgers. Gradually the little circle thinned; its members died off one by one, till Mrs. Seymour, a widow, was left to keep house for only one survivor, Charles Reade. Their relationship, from first to last, was one of pure and sacred friendship, and the world would be better, in my opinion, if such friendships were more common. Bright, intelligent, noble-minded, and generous to a fault, Laura Seymour deserved every word of the passionate eulogy which Charles Reade composed upon her death, and had engraved upon her tombstone. She was a little woman, bright-eyed, vivacious, and altogether charming. In all literary matters she was his first adviser and final court of appeal; but, like himself, she was very impulsive, and occasionally wrong-headed. She had the best and finest of all virtues—charity. Wherever there was poverty and suffering, her purse was as open as her heart. She loved dumb animals, dogs especially. In the pleasant days that are gone I used to drive down to Albert Gate a certain Pickwickian pony of mine, christened Jack. On his first appearance at the gate, nothing would content the good Seymour but that I should take him out of the trap, release him of his harness, and escort him through the house to the back garden. “Poor fellow!” she cried; “do bring him in, and let him graze on the lawn.” This would hardly have done, as Jack was a soft sybarite already, and too plump, moreover, to get through the lobby without accidents. Mrs. Seymour relieved her kind heart by sending him out some cakes and bread, to which he was very partial; and ever after that day, when Jack pulled up at the Vineyard, be sure he had his treat of something nice, given by that kindly and gentle hand.

In his personal habits Reade was exceedingly eccentric. For example, he had a mania for buying all sorts of flotsam and jetsam, with the idea that they might “come in useful.” On one occasion he purchased a stuffed horse’s head, thinking he might utilize it in one of his plays, and placed it in his lumber-room, where it soon became moth-eaten. On another, he invested in a large number of knives and forks, which he secreted away, thinking to produce them afterward triumphantly. “Seymour,” he explained to a confidant, “thinks of giving a party; so I’ve purchased this cutlery in case she may run short.” He was troubled with corns, and wore enormous boots. We found him one morning with a whole waste-paper basket full of new boots, which lie had ordered wholesale, after a pattern that took his fancy. His gingham umbrella would have delighted Mrs. Gamp. Altogether, his whims and oddities were a constant care to Mrs. Seymour, who rallied him mercilessly about them. In his play of Jealousy, produced at the Olympic Theatre, there was a scene where one of the actresses, supposed to be a danseuse, had to hide behind a very high screen. “Do you think, my dear,” he said to the actress rehearsing the part, “you could show the agility of the danseuse by lifting your foot and letting foot and ankle pass in sight of the audience, close to the top of the screen?” but this bit of gymnastics was declined as simply impossible. “Then, my dear, we’ll have a false leg made, and at the proper moment you will work it, gracefully and rapidly, as I shall direct.” It is scarcely necessary to add that this realistic notion was not carried out.

I am disposed to think that Mrs. Seymour’s influence had much to do in sweetening and softening the character of Charles Reade; that it was altogether a benign and beautiful influence, to which the world, however indirectly, owes much. A photograph of Reade, taken when he was about five-and-thirty, shows a sternness of outline and truculence of expression which afterward completely changed; it represents, indeed, a face of extraordinary power, but no gentleness. Another photograph in my possession, taken at Margate in 1878, pictures the same face, softened by the touch of time; the face of a “benevolent imbecile,” he himself playfully calls it in a brief note upon the back. I have no doubt whatever that his benevolence was greatly fostered by his warm-hearted companion; but be that as it may, he was, when I knew him, the gentlest of men—like our friend Boanerges, all fire and thunder in the pulpit, all kindliness and sweetness at his own fireside. The fact is, his style was a thorough-bred, and often ran away with him, or, when he sought to drive it mildly, kicked the subject to pieces. He was the Boythorn of literature, only the big speeches and terrible invectives were not spoken, but set down on paper. Yet he looked on human nature with the eye of a lover. He too had a passion for dumb animals. Not long before his death he filled the garden with tame hares. A noble deed stirred him like a trumpet; great as his hate for wrong-doing, was his compassion for suffering. Over and above all was his natural piety, which bound his days each to each as with a chain of gold.

In these days of problem-guessing, when the simple religion of our fathers is put aside and labelled “anthropomorphic,” when the mathematician is rampant, and the gigman ostentatiously spells God with a little “g,” it was refreshing to meet with a man who found the old-fashioned creed all-sufficing. Perhaps Charles Reade’s intellect was not speculative, perhaps it had exhausted all its speculation in the “Sturm und Drang” period of early youth; but whether or not, his latter mood was one of untroubled faith in an All-Wise and All-Merciful Father. He believed in science, as all sane men do, but he clung to religion, as all wise men must. He was not, until the very last, a church-goer, and he had no regard for dogmas, however domineering; but he was deeply and unobtrusively pious in his heart of hearts. Remembering what he was throughout all his days, I think that last epitaph of his, composed for his grave-stone when he already felt the finger of Death upon him, one of the most touching things that have ever been written by a strong man. It was as follows:

HERE LIE,

BY THE SIDE OF HIS BELOVED FRIEND

THE MORTAL REMAINS OF

CHARLES READE,

DRAMATIST, NOVELIST, AND JOURNALIST.

HIS LAST WORDS TO MANKIND

ARE ON THIS STONE.

I hope for a resurrection, not from any power in nature, but from the will of the Lord God Omnipotent, who made nature and me. He created man out of nothing, which nature could not. He can restore man from the dust, which nature can not.

And I hope for holiness and happiness in a future life, not for anything I have said or done in this body, but from the merits and mediation of Jesus Christ.

He has promised his intercession to all who seek it, and he will not break his word: that intercession, once granted, can not be rejected: for he is God, and his merits infinite: a man’s sins are but human and finite.

“Him that cometh to me, I will in no wise cast out.” “If any man sin, we have an advocate with the Father, Jesus Christ the Righteous; and he is the propitiation for our sins.”

It is doubtful if any other living man could have composed the above, clear and commonplace as it may sound; it has all the wisdom of supreme simplicity, all the science of perfect expression.

Charles Reade’s literary life embraces a period of little more than thirty years. When we first met, in 1876, I was years younger than he had been when he published his first book. “I envy you, Buchanan,” he once said to me; “you might lie by and rest silent for ten long years, and still have a glorious time of work before you.” His conviction was that a literary man, especially a novelist, was scarcely ripe enough for important utterance before he reached the forties. I cited the cases of certain famous poets. “Oh, that is different,” he replied, with his sly smile; “poetry requires neither knowledge nor experience, you know—it is nonsense pure and simple.” Yet the great poets, he continued, were qualified by gray hairs: Homer, Dante, Shakespeare, Milton, had a long foreground of life for their masterpieces. Speaking generally, he shared Carlyle’s prejudice about verse-poetry. Of all the modern singers, Scott was his favorite, “because he could tell a great story.” Of course my friend’s poetical tastes were old-fashioned, and his canons in criticism not far in advance of those of Dr. Johnson, whom, by-the-way, he particularly admired. There is something to be said, however, even for his point of view. Modern verse-writers have alienated the public, because they have imitated the Eastern Spinning Dervish, lost in rapt contemplation of his own navel, or inner consciousness, forgetting life with all its endless humors, its pathos, and its infinite variety of theme.

He was a great reader of novels, blue-books, and the newspapers. Of criticism he had the same opinion as George Henry Lewes, who once wrote: “The good effected by criticism is infinitesimal, the evil incalculable.” It was quite natural, therefore, that such a man should be the target for all sorts of attacks. The general idea of him is that he was morbidly sensitive in such matters. He was nothing of the kind; but he was pugnacious, and when roused, dearly loved to flourish the shillalah. Of course he did not always see the joke when his good name was filched away, his character maligned, and his patient work undervalued, as very often happened. Yet, like all strong fighting men, he was magnanimous. I know of one instance where the widow of a literary opponent—a man who had assaulted him very cruelly—reaped the full measure of his forgiveness, and his charity. He was, as we all know, litigious, less because of any infirmity of temper than because he was a brilliant lawyer and advocate, invariably successful in conducting his own cases. He was proud, and justly proud, of his power as a publicist and journalist, for on more than one occasion his pen had opened the prison door, and his voice appalled the soul of an unjust judge. The good he did in this way lives after him; the world is freer, justice is more alert, innocence feels safer, through the sunlight reflected back on our jurisprudence from the mirror of Charles Reade.

The death of Mrs. Seymour, which took place not long after the production of Drink at the Princess’s Theatre, was a blow from which he never entirely rallied.. I was in Ireland at the time, and when I came to London the funeral was over, and Reade was alone in the desolate house. Never shall I forget his look as he sat, a broken man, at the writing-table, surrounded by likenesses, paintings and colored photographs, of his beloved friend. In all of them, however unfaithful to the original, he found something that suggested her loving face. He could talk of nothing, think of nothing, but her whom he had lost. His grief was pitiful to witness. In his desolation his godson, Mr. Liston, himself a man of scholarship and fine attainments, came to live with and comfort him, doing a thousand gracious things, working with him, reading with him, to help him in his great trouble. But it soon became clear that to reside permanently in the old house was to keep the wound green and open, and as speedily as possible he removed to Shepherd’s Bush, taking a small house next door to the one occupied by his brother. He still continued, however, to visit 19 Albert Gate for a few hours every day, though his most frequent pilgrimage was to the quiet churchyard at Willesden, where Laura Seymour was lying. He eased his overladen heart in constant charities done in her name; found out her pensioners, of whom there were many, and helped them for her sake. Whenever he gave a gift of money it was given “from Laura Seymour and Charles Reade.” She was with him in the spirit still, helping him as of old, and sanctifying his life. As time wore on he recovered a little of his old power of work, but his power of human enjoyment was gone forever. “I have done with this world,” he said. He lived to write another novel and to produce another play (written in collaboration with Mr. Henry Pettitt), but in both cases it was clear that the busy hand had lost its cunning. In the winter of 1883 he went to Cannes, where he finished his last novel, A Perilous Secret. With the hand of Death upon him, he struggled homeward, fluttered as far as Calais, where he rested, moribund, arrived finally at Shepherd’s Bush, wrecked in mind and body, and there, within a few days, painlessly passed away, in the seventieth year of his age.

It was a dark, showery day in April last when they carried him to his last resting-place, beside his life-long companion, in Willesden church-yard. Only a few mourners were gathered round the grave, but those few loved him, and were deeply moved. His only surviving brother, his godson Mr. Liston, his old friend John Coleman, with whom he had had many a dramatic experience, and Davenport Coleman, attached and faithful in death as in life, were among the number; there, too, was George Augustus Sala, who never wrote ungenerously of any man, and whose name is a synonym for good-fellowship and kindliness of heart. As we stood and listened to the beautiful burial service (old- fashioned, in the fashion of the loveliness that is stronger than death), and saw the flower-covered coffin lowered into the grave, the sun shone out in answer to the words of immortal promise, and the light sparkled on the trees, and the world brightened as for resurrection. “O grave, where is thy victory! O death, where is thy sting!” It was the last scene of a noble play, the end of a beautiful and honorable life. When we turned away and left him, we seemed to hear a voice crying, “Well done, thou good and faithful servant,” for truly he had earned his rest.

In one of the most charming of his Roundabout Papers, which opens with a description of a London suburb very early in the morning, Thackeray took occasion to remark that his readers would no doubt wonder that he was awake at so early an hour. “The fact is,” he explained, “I have never been able to sleep since the Saturday Review said I was no gentleman.” This delicious piece of humor was vividly recalled to my mind by some of the obituary comments on the novelist just departed. He, good man, slept soundly enough, never again to be baited by the Bottoms of contemporary criticism, and it would have disturbed his equanimity little to have read, even during his lifetime, that he was neither a “gentleman” nor a “genius.” To us who knew him, who perceived both his gentleness and his genius, who mourned in him the last of a race of literary giants, and who believe that his name is written on the rock, and must endure, it was nevertheless somewhat painful to perceive that the stupidity which pursued him during his lifetime had little or no respect for his memory even while it was yet green;

“For o’er him, ere he scarce be cold,

Begin the scandal and the cry.”

The scandal of a slipshod criticism, the cry of all the purblind talents, which was summed up with painful directness in some verses contributed by Mr. William Archer to the Pall Mall Gazette—verses as remarkable, I am bound to say, for their old-fashioned literary power as for their obliquity of literary vision. In Mr. Archer’s estimate, or epitaph, Charles Reade was a genius manqué—

“A Quixote full of fire misplaced,

A social savior run to waste. . . .

Unskilled to reach the root of things,

He spent his strength on bickerings;

In controversies small and great

Would dogmatize and fulminate,

Till ‘Hold, enough!’ the people cried,

Converted—to the other side!. . . .

For, gauge his merit as you will,

’Tis ‘manner makes the classic’ still,

And he who rests in silence here

Was but a copious pamphleteer.”

Fortunately this sweeping censure trenches on matter of fact, and can so far be met by an appeal to popular experience. Is it true, then, that on all or any of the great topics handled by Charles Reade the public sided against him? or is it true, on the other hand, that he really did convert the public to his own side, and so redress innumerable wrongs? The answer may be given without hesitation. On the question of prison reform, of the lunacy laws, of copyright in plays and books, of criminal procedure, he appealed to the great English people, and invariably triumphed. But the works in which he made his immortal appeals are not pamphlets; they are masterpieces of realistic imagination. It is as true to say of him that he was only a “copious pamphleteer” as it was to say of Thackeray that he was no gentleman, of Dickens that he was only a cockney humorist, of Shelley that he was merely a transcendentalist, of Wordsworth that he had no “form,” and of Shakespeare that he had no “style,” all which weighty assertions have been made within man’s memory by the criticism that is contemporary, or by the perversity which is “not for an age, but for all time.”

To tell the truth, Charles Reade knew little of that art which is called “humoring one’s reputation,” and which in our England has enabled little men to sit in the great places, and mediocre men to reap the honors of ephemeral godhead. A little talent, a great deal of reticence, a spice of coterie glory, plus a large amount of public ignorance, soon constitute a bogus reputation, which resembles the bogus residences run up by speculative builders, where everything is perfectly finished to the eye, in admirable taste and temper, but where nothing, in the long-run, will stand wind and water. The “manners make the classic,” says Mr. Archer, and the manners decidedly make the bogus reputation. From the time of Ben Jonson to that of Pope, from the time of Pope to that of Samuel Johnson, from the time of Johnson to that of Crabbe and Gifford, your bogus reputation has flourished exceedingly for a little season, to slip down ultimately upon sandy foundations.

But when all is said and done, the style is the man, and by it the man lives or dies. Because the style or manners of Charles Reade, projected into books, preserves for us one of the most lovable and love-compelling personalities of this or any time, we who knew the master can smile at the mistakes of the literary critic and the epitaph-writer, and safely leave the verdict to a near or remote posterity. For the rest, it is not my present office to criticise, or even to protest. I have merely set down, to the best of my ability, a few personal sketches of the man in his habit as he lived. I know him to have been good and great. A man of genius, a true servant of the public, a faithful friend, and a humble Christian, he leaves a precious memory, and works which the world will not willingly let die.

_____

Back to Essays

|