|

Play List: 4. Corinne 7. The Mormons 9. Lucy Brandon 10. Storm-Beaten 11. Lady Clare 13. Bachelors 14. Constance 15. Lottie 16. Agnes 17. Alone in London 18. Sophia 19. Fascination 20. The Blue Bells of Scotland 21. Partners 24. Angelina! 25. The Old Home 26. A Man’s Shadow 27. Theodora 29. Clarissa 30. Miss Tomboy 32. Sweet Nancy 33. The English Rose 36. Marmion 37. The Gifted Lady 38. The Trumpet Call 39. Squire Kate 40. The White Rose 42. The Black Domino 44. The Charlatan 45. Dick Sheridan 47. Lady Gladys 48. The Strange Adventures of Miss Brown 49. The Romance of the Shopwalker 52. Two Little Maids from School ___ |

|

ROBERT WILLIAMS BUCHANAN (1841 - 1901) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

BUCHANAN’S THEATRICAL VENTURES IN AMERICA 1884-1885

In 1884 Robert Buchanan and Harriett Jay went to America. In Chapter XXIII of her biography of Buchanan, Miss Jay deals with the trip in two paragraphs: “In the year 1884 he made his first and only trip to America. He had a contract to supply a play to Messrs. Shook and Collier, then managers of the Union Square Theatre, New York, but he went without having written it. On his arrival he offered for their acceptance a melodrama which was our joint work, and which has since become popular under the title of “Alone in London.” This, however, they refused, and it was produced by Mr. Buchanan himself at the Chestnut Street Theatre, Philadelphia, where it drew crowded houses. At the conclusion of its first run it was taken up by Colonel Sinn, of Brooklyn, who, besides giving very fine terms, bought all the scenery which had been specially painted for it. _____

Stormbeaten and Lady Clare

The earliest mention of a possible trip to America is contained in a letter to the theatrical producer Augustin Daly, in which Buchanan tried to interest him in a production of The Nine Days Queen starring Harriett Jay. Although the date on the letter does not mention the year, I speculate that this was written shortly after the play closed in London at the end of March, 1881. There are two earlier letters, written in 1875, from Buchanan to Daly trying to interest him in productions of his plays, A Madcap Prince and Corinne, but this is the first to suggest that he “would bring over play & leading actress, & myself superintend production in New York.” However there was not much interest in Buchanan as a dramatist until he had a twin success in 1883 with Storm-Beaten and Lady Clare. And Harriett Jay’s reviews as an actress were fairly lukewarm until her first performance in a male role, as Cecil Brookfield in Lady Clare. Both plays were acquired for American productions, the first by Messrs. Shook and Collier, the second by Lester Wallack, but the general attitude of the American press to Buchanan was not encouraging.

New-York Daily Tribune (8 July, 1883) MISS DOLARO’S NEW PLAY.—Selina Dolaro has sold her comedy to Shook & Collier of the Union Square, and they are quite enthusiastic about it. Miss Dolar is more modest, however, and does not want anything said about it yet awhile, “as it is not to be done until after the run of ‘Storm Beaten.’” That will in all probability be a very short one, for “Storm Beaten” appears to be a stupid sort of heavy drama which Collier bought at the round price of $10,000 much as he might have bought “a pig in a poke” or accepted a gift horse, without looking at it. It is to be hoped that Mr Collier has not made as big a mistake in this selection of “Storm Beaten” as in his judgment of “Coney Island,” for laughing at which farce he still blames his friends. Miss Dolaro is to perform in her comedy, but what sort of a part, the fair opera bouffe artist refuses to tell—“just yet.” ___

The New York Times (6 January, 1884) NEWS FROM THE THEATRES THE MARKET PRICE OF PLAYS FROM EUROPE. Mrs. William Henderson, the wife of the late Standard Theatre manager, is disturbed over the tendency of theatrical speculators to buy foreign pieces at the expense of native authors. Mrs. Henderson has haerself written several plays, and at least one of them has gained a much more than common success. Her “Almost a Life” has been played both in this country and in England with good results, and Mrs. Henderson, having established the fact that she can write a drawing play, is entitled to some consideration at the hands of managers in general. By her own account, as delivered to THE TIMES’S writer yeaterday, she does not get it. ___

In May 1884, both versions of Lady Clare were on display in Brooklyn.

Brooklyn Eagle (4 May, 1884 - p.7) HAVERLY’S THEATER. “Claire and the Forge Master,” an English dramatization of Ohnet’s famous French novel “Le Maitre des Forges,” by Mrs. Ettie Henderson, is to have its first representation in this city at Haverly’s Theater to-morrow night. The presentation of the piece derives interest at this time from the circumstance that it will reintroduce to this public Miss Maude Granger and also that it challenges comparison with a version of the same story offered at another house. The cast of characters is enumerated in the following list: Claire De Monbrison ... Miss Maude Granger “Claire” matinees are appointed for Wednesday and Saturday afternoon. The briskness of the demand for places indicates crowded houses at every performance. _____ PARK THEATER. The “Lady Clare” of Robert Buchanan is to be set forward at the Park Theater, to-morrow night, on which occasion the play will be first seen here as given originally at Wallack’s Theater—cast, scenery and stage appointments being identical with the production of the drama at that house. The distribution of parts in the piece is as follows: John Middleton ... Osmond Tearle It is claimed for Mr. Buchanan’s drama, that while its leading motive is drawn from “Le Maitre des Forges,” it is not a literal adaptation of that work. Upon this point Brooklyn playgoers will be afforded an opportunity for judging for themselves during the present week, at the several evening performances and the Wednesday and Saturday matinee representations of “Lady Clare” at the Park. ___

The New York Times (18 May, 1884) Mr. Robert Buchanan, the adapter of “Lady Clare,” has written a new comedy which he is trying to get produced in London. Mr. Buchanan is led to this reckless course through the success of “Lady Clare” and the large royalties which have poured into his pocket from this country ever since the production of this piece. In London Mr. Buchanan is not regarded with enthusiasm by theatrical managers. In the first place he has written a large number of pieces, none of which, barring “Lady Clare,” has been successfully performed in the English metropolis. In the second he has a sister-in- law named Harriet Jay, who is the cause of travail and sorrow in managerial circles. Whenever Mr. Buchanan writes a play he insists, as far as he can, upon having Miss Jay perform the principal character. The lady is an amiable and interesting person when she does not try to act. But the quickest preparation for a London exodus lies through the appearance of Miss Jay in public. It is because Mr. Buchanan, metaphorically speaking, goes around with a bundle of manuscript under one arm and his sister-in-law under the other that he is not enthusiastically regarded by English managers. ___

More items in the press indicate that Buchanan was still contemplating an American trip:

Davenport Weekly Gazette (Iowa) (22 August, 1883 - p.12) Robert Buchanan intends to come to America next Winter to supervise the performance of a play made out of his “God and Man.” ___

Brooklyn Eagle (13 April, 1884 - p.1) Harriet Jay, the novelist and actress, is going to the United States under the management of Colonel Sinn, of Brooklyn. She will appear in Mr. Robert Buchanan’s historical dramas. ___

Spirit of the Times (New York) (26 April, 1884) THE ENGLISH STAGE. [FROM OUR SPECIAL COMMISSIONER.] . . . LONDON, April 4.— . . . Miss Harriet Jay—whose romance, “The Queen of Connaught,” was widely read when it first appeared, and whose more recent novel, “Through the Stage Door,” is just now to the fore—is not only a brilliant writer, but an accomplished actress, and I hear she has offered to proceed to the United States, in the autumn, with a view to bringing out Robert Buchanan’s powerful drama, The Nine Days’ Queen, in which she sustains the role of Lady Jane Gray. Properly managed, Miss Jay ought to be attractive on your side of the Atlantic. ___

The National Police Gazette (New York) (17 May, 1884 - p.3) JAY.—Harriet Jay is not coming to the United States under the management of Col. Wm. E. Sinn, of Brooklyn. A thousand thanks, Harriet. We have got enough jays of our own without importing any. ___

And another London letter from Howard Paul (this time in the American Register) alerted America to one aspect of Harriet Jay which would later be the cause of some controversy: It was reprinted in various American papers as well as this English one (and there is also a curious similarity to a later piece published in the The Omaha Daily Bee on 25th November).

Manchester Courier and Lancashire General Advertiser (7 June, 1884 - p.16) A LADY NOVELIST’S METHOD OF WORK. Mr. Howard Paul contributes the following to the American Register:—“I believe it is a well-known fact that the famous George Sand used to perambulate the Quartier Latin in masculine garb, and I once saw Mrs. Fanny Kemble many years ago bestride a nag in a country lane in an Eastern State dressed in bifurcated integuments. In a general way ladies do not don the breeches, but genius is eccentric, and does as it pleases. I was calling on Miss Harriet Jay, the authoress, the other day, and found her costumed in an elegant suit of black velvet, a natty short jacket and well-fitting knickerbockers. She was sitting at her desk working away at a story which is shortly to appear as a serial. Before she turned to greet me I thought it was a lad, possibly her secretary, who was bending his brow over the éscritoire. A glance at the beautiful face quickly placed me courant with the situation, and Miss Jay laughingly informed me that she usually performs her literary work dressed as a boy, and exceedingly quaint and picturesque she looked.” ___

However, it was not until after the popular success of the American productions of both Storm-Beaten and Lady Clare, that Buchanan made the trip across the Atlantic, with Harriett Jay in tow. Two reports in the Liverpool Mercury (the first following a review of Harriett Jay’s performance as Lemuel, the gipsy boy, in a scene from The Flowers of the Forest at a benefit for Mr. Charles Kelly at the Prince’s Theatre, London on 16th July) suggest Buchanan and Jay embarked sometime in August:

Liverpool Mercury (19 July, 1884) Mr. Robert Buchanan is writing a play for the Union-square Theatre, New York. His “Lady Clare” was the great success of Wallack’s last season. We understand that Mr. Buchanan intends to go over to America in order to superintend the production of his new piece. This will be, we think, his first visit to the West, though “Saint Abe” and “The White Rose and Red” led readers to suppose that Mr. Buchanan must be as familiar with America as with the islands of Scotland. For some years Mr. Buchanan has had a considerable following in America both as poet and novelist, and it is probable that the forthcoming visit may excite a good deal of interest. ___

Liverpool Mercury (21 August, 1884) We announced Mr. Robert Buchanan’s intention to visit America, and have to add that he is now on his way to New York. He goes out to arranged the details of his play, which will be produced at the Union-square Theatre in about two months. Immediately on his departure, Mr. Buchanan assured us that one of his first visits would be to Walt Whitman. It will not be forgotten that Mr. Buchanan vindicated Whitman against unjust aspersions, in an eloquent and powerful letter, which was printed in the Daily News some years ago, and created a profound impression in England, and a good deal of lively comment in America. The letter contained one piece of description which readers of it are not likely to forget. It described a scene among the Highlands of Scotland, where a cloud of ravens pursued a single eagle, old, worn, and enfeebled, the croaking birds falling back when the king of the air turned his great head about to them. This figure as applied to Whitman and the American publishers was hardly likely to please the persons who personated the ravens, and a newspaper war was the consequence. But the American public has opened its arms to more recent productions of the same pen. It is to be hoped Mr. Buchanan’s determination to visit Whitman at the outset will not open afresh the bitter part of the memory of a forgotten episode. ___

Robert Buchanan did not get to meet Walt Whitman (the Daily News letter mentioned above is available here) until March, 1885, when he was arranging the first performance of “Alone in London” in Philadelphia. By 25th August, 1884 Buchanan and Jay were in America, but the details of how they got there are rather sketchy. _____

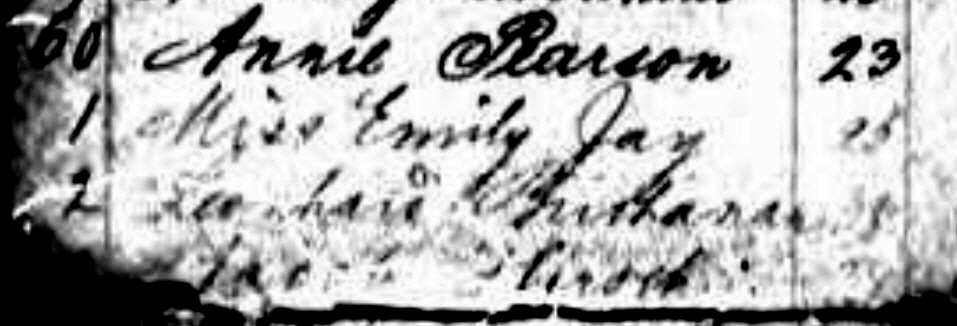

Miss Emily Jay and Leonhard Buchanan, merchant

I believe Buchanan and Jay embarked on the steamship Eider at Southampton on 7th August, 1884. I’ve found no mention in newspapers of their departure from England, or arrival in America, but checking the New York Passenger Lists I came across what is either an astounding coincidence, a feeble attempt by Buchanan and Jay to conceal their identities, or a simple case of clerical error on the part of the Eider’s crew. I have checked the microfilm copies of the Lists (via the Internet Archive) and they are in a very sad state. I also tried a genealogy site, where no Buchanan appeared for July or August 1884, but which did throw up a Miss Emily Jay, 25 years of age, no occupation, and her nationality and destination both given as ‘U. S. of A.’ Obviously nothing to do with our ’Arriett, except beneath her name was what the transcription gave as Leonhard Buthanan, 38, merchant, and both joined the Eider at Southampton. |

|

|

Personally, I think it’s Richard, rather than Leonhard, but it’s definitely not Robert. The picture below gives the rest of the information about the couple, and the full page is available here |

|

|

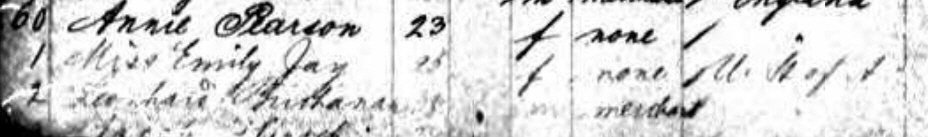

The handwriting on the list does look fairly consistent, so I would presume it was compiled by a member of crew. So the mistakes could have arisen then, although personally I like the possibility that Harriett Jay was trying out an American accent, while Buchanan was playing the part of a merchant. The Eider was a German steamship bound from Bremen to New York, which docked in Southampton to take on cargo and passengers and left on the evening of Thursday, 7th August, 1884. It arrived in New York on 16th August. Given the dates and the lack of any other evidence to the contrary, I would be very surprised to find that Robert Buchanan and Harriett Jay did not travel on the Eider to America. |

|||

|

|||

|

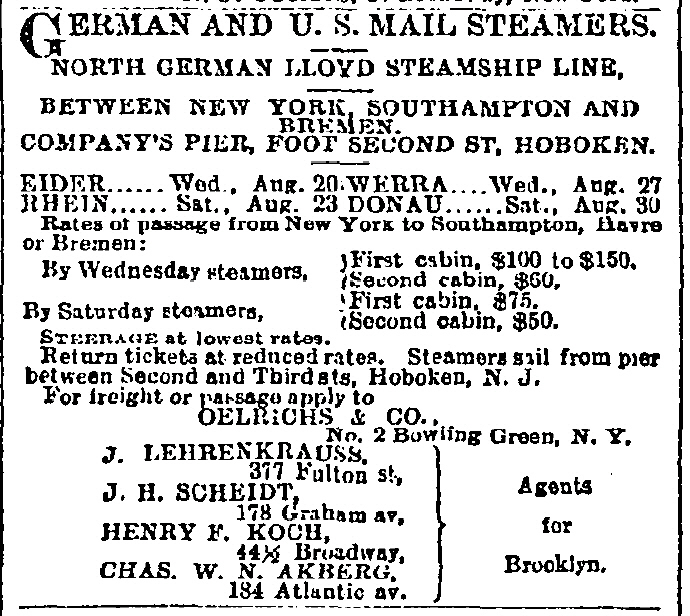

[The Eider of the North German Lloyd Steamship Line.] According to an article in The New York Times (12 April, 1891) on ‘Fast Atlantic Passages’: “On her second trip, in April, 1884, the Eider reduced the westward passage to 7 days 18 hours 10 minutes, and in June she came back in 7 days 19 hours. In the July of the following year (1885) the Eider made a westward passage of 7 days 17 hours.” And for an indication of what it cost Buchanan to cross the Atlantic, the Eider’s rates are given in this advert from The Standard (4 August, 1884): |

|||

|

|

And, for the return trip - from The Brooklyn Daily Eagle (15 August, 1884): |

|

|

Although Buchanan’s arrival on the Eider was not mentioned, this final item reveals what else the ship was carrying - rather ironic considering Buchanan’s constant struggle with money.

The New York Times (17 August, 1884) The steamship Eider, which arrived from Europe yesterday, brought $500,000 in gold bars for the Bank of British North America and $125,000 in gold coin for Plock & Co. This makes $2,375,000 in American gold that has been returned from abroad since Aug. 1. Bankers of this city say that there are gold buying orders now in London from New-York houses amounting to fully $5,000,000. _____

Buchanan and Jay in America

The first mention of a sighting of Buchanan in America is at the production of Storm-Beaten at the Grand Opera House on 25 August, 1884.

The New York Times (26 August, 1884) GRAND OPERA HOUSE. Jay Gould’s box in the Grand Opera House was fringed with red, white, and blue a yard wide last night. Within this gorgeous setting were Commander Schley and his family and a party of friends. Chief Engineers Melville, Nauman, and Lowe, Lieuts. Semly and Sebur, and Dr. Greene were in the box above, while directly opposite were Commander Coffin and his family. Robert Buchanan, the novelist and author of the play of the evening, “Storm Beaten,” fresh from London, looked down upon his work from another box, with friends on every side, while sitting in a row, bolt upright, in the best seats in the house were 20 or more of the sailors of the Greely relief expedition. If an appreciative audience gives pleasure to a writer Mr. Buchanan must have been in ecstasies last night. Ninety-five out of every hundred of the seats in the house were filled with auditors who applauded the hero and execrated the villain in the most approved manner. The play was given by Shook & Collier’s combination, and the cast, taken as a whole, was a good one. The principal male part fell to Mr. Edmund Collier, whose vigorous acting won him much applause. Miss Belle Jackson, formerly of the Madison-Square Theatre, was cast as Priscilla Sefton, and she played the part naturally and with good taste. Mr. Augustus J. Bruno, who became a favorite in New York in plays of “The Brook” type, succeeded in creating much laughter as the shepherd. The scenery was excellent, and the effects were very realistic. ___

The New York Mirror (30 August, 1884 - p.2) The Grand Opera House was comfortably filled Monday night when Shook and Collier’s combination appeared in Storm-Beaten. The author, Robert Buchanan, saw his piece on this occasion for the first time in America. Members of the Greely relief party occupied a private box, which was liberally draped in bunting. The performance was well received and the observers became quite enthusiastic over the genuine Arctic survivors who figured in the ice scene. Edmund Collier gave his vigorous, manly personation of the inflexible Christian, and John T. Burke fully developed the forbidding characteristics of Richard Orchardson. A. J. Bruno as Jabez and L. F. Rand as Parson Sefton were acceptable. Belle Jackson acted Priscilla sweetly, and Lizzie C. Hudson created a favorable impression as Kate. The minor parts were generally well played. The staging was even better than that of the original production at the Union Square Theatre. The attraction at this house next week will be Mr. Campbell’s Separation. _____

A Hero In Spite Of Himself |

|

|

|||||

|

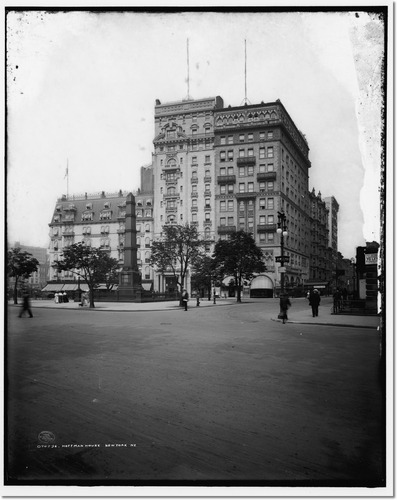

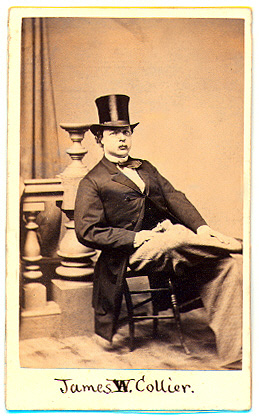

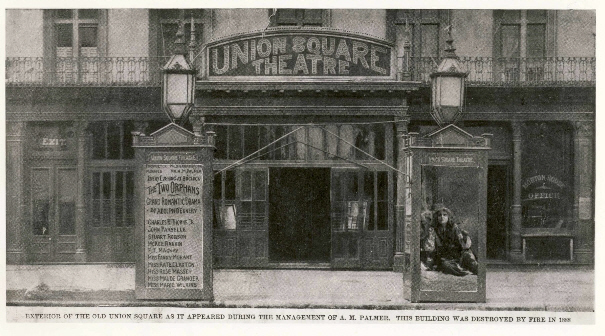

Messrs. Shook and Collier and their Union Square Theatre below (click image for larger version). |

||||||

|

||||||

|

The play which Buchanan had been contracted to write for Messrs. Shook and Collier of the Union Square Theatre, New York (and which Harriett Jay claims he never wrote) was entitled A Hero in Spite of Himself. The play was rejected and was never performed, either in America or Britain. The reason for the rejection was apparently revealed in a court case of December, 1888, when Messrs. Shook and Collier attempted, successfully, to regain the £150 advance which they had paid to Buchanan for his ‘American society drama’.

The New York Times (20 December, 1888) NOT TRUE TO AMERICAN LIFE. In 1884, when Sheridan Shook and James W. Collier were managing the Union-Square Theatre, Robert Buchanan engaged to write them an American society drama, for which he was to receive £1,000. An advance payment of £150 was made, and in due time the new play was brought over. It was called “A Hero in Spite of Himself,” and was built on the English ideas of Western life. The male characters would have been obliged to wear red flannel shirts and tuck their trousers into their boot legs, and the ladies in the cast would have appeared in costumes equally incongruous to real American society. Shook & Collier sued Mr. Buchanan to recover their £150 advance, and yesterday David Gerber of ex-Judge Dittenhoefer’s office presented the case to the jury in the Supreme Court, before Judge Lawrence. Mr. Buchanan was defended by Howe & Hummel. The jury were not satisfied with Mr. Buchanan’s ideas of American society and brought in a verdict against him of $945. ___

Buchanan gave his side of the story in the following letter.

The Era (9 March, 1889) THE AMERICAN MANAGER, OLD STYLE. TO THE EDITOR OF THE ERA. Sir,—America is still a long way off, and American ways, especially in the matter of law, are still far beyond the comprehension of purblind Europeans. The paragraph contained in your issue of to-day, and stating that a certain Judge O’Brien has issued an order to attach certain monies of mine at the suit of Messrs Shook and Collier, late of the Union- square Theatre, needs a little explanation. ___

Although A Hero In Spite Of Himself was never performed, a novel-length story by Buchanan, bearing that title, began serialisation in The York Herald in October, 1886 (available on this site). The theatrical origin of the story is quite obvious, with a first act, or prologue, set in England, then a couple of acts in a fashionable resort on the east coast of America, all within the remit of a ‘society drama’, which are then followed by a trip out west for a couple of dramatic shoot-outs, before returning to New York for the final act. In Shook and Collier’s defence, these scenes of western life did shift the play from ‘society’ to ‘sensational’ drama and if they were expecting another Lady Clare they might have been disappointed to get another Storm-Beaten. They might also have been aware of the failure of an earlier play of Buchanan’s, The Mormons: or St. Abe and his Seven Wives, which had only lasted for a month on the London stage in 1881, and which had similar scenes set in the ‘wild west’. I also came across the following item.

The Daily Graphic (New York) (Tuesday, 7 October, 1884) At the Union Square Theatre last night Robert Buchanan and his sister-in-law, Harriet Jay, occupied the right-hand private box, and Elliott Barnes the box at the left; and Mr. Winter of the Tribune occupied with extreme success a white vest and a red necktie. ___

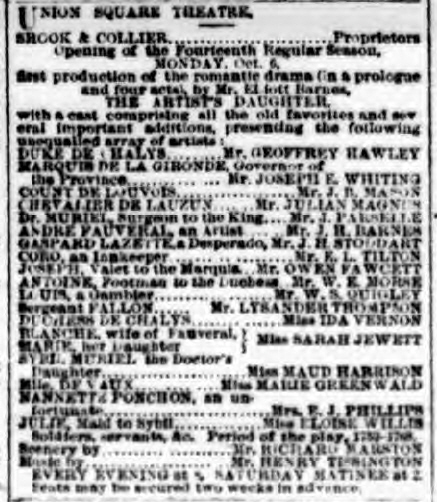

The play they had gone to see was The Artist’s Daughter by Elliott Barnes, presumably Shook & Collier’s replacement for A Hero In Spite Of Himself. |

|

|

[Advert for the first night of The Artist’s Daughter from The World (New York) (6 October, 1884 - p.5).]

Following the rejection of the play which Buchanan had come to America to help produce, he was obliged to try other avenues. An interview published in the New York Daily Tribune (6 September, 1884) gives an indication of his mood before his meeting with Shook and Collier. “Mr. Robert Buchanan, the well-known English author, who is now visiting in this country was visited Thursday, by a member of THE TRIBUNE staff, and in the course of a conversation, imparted some interesting news concerning his present trip to America. Mr. Buchanan is a typical Englishman in appearance and manner. He is of medium height and of stout build, and wears a handsome beard carefully trimmed after the manner of the Briton. Since his arrival in this country, about three weeks ago, he has been spending his time alternately at the Hoffman House, in this city, and the Pavilion Hotel, New Brighton, Staten Island. . . . On being asked what was his chief object in visiting America, Mr. Buchanan replied: ‘Purely practical. I have been, as you are perhaps aware, connected with practical management as well as playwriting, and I wish to complete an artistic and financial scheme, for which I have already secured valuable support in London; but I want to increase my capital by co-operation with a man of dollars in America. Then, I had to see Messrs. Shook & Collier about my new play, which they are anxious to secure, and to arrange for the production here of a new comedy, which will be produced in London late this fall, with one of our brightest actresses, Miss Kate Vaughan, in the leading part.’ . . . ‘Is your new play a melodrama?’ ‘No, a drama of society, with plenty of humor; I am convinced the public taste lies in that direction. It also deals much with American life and scenery.’” |

|

|

|

The comedy starring Kate Vaughan never materialised but Buchanan was also considering another play for his, and Harriet Jay’s, American début, The Nine Days’ Queen, which he also mentioned in another interview, in The Buffalo Express (21 September, 1884): “My best play, however, has yet to be seen in America. I have been assured that it is one of the few poetical plays of modern times that will live. It is founded on the life and death of Lady Jane Grey, and my sister-in-law, Miss Harriett Jay, one of the most beautiful women in England—by birth, education, and loveliness, the ideal Lady Jane Grey—will act the heroine.” Buchanan also gives a few first impressions of America: ‘“ . . . But your cigarettes are abominable. Your women—”

And then there was the food:

The Critic (13 September, 1884) The Lounger. MR. ROBERT BUCHANAN is over here, spending his time between New York and Staten Island. He has honored us with his presence for the purpose of bringing out a spectacular drama in this city, in which his sister-in-law, Miss Harriet Jay, is to play a leading part. To our mortification be it said, Mr. Buchanan is not favorably impressed with America. He is one of the unfortunate Englishmen who are unable to find anything fit to eat in New York. But we will not complain— so long as our cooking pleases the French palate. We have a higher idea of French taste in the manner of cooking than of English, and would rather have our dinners praised by a Parisian than a Londoner. Poets as a rule are not epicures, but Mr. Buchanan may be an exception. He looks, however, as though he would prefer a stalled ox to lotos and wild honey. ___

Buchanan’s opinions were repeated in newspapers across the States but his theatrical intentions at this point become a little obscure. He also seems to have moved from the Hoffman House.

The New York Mirror (27 September, 1884 - p.6) BUCHANAN.—Robert Buchanan will remain in America all Winter. He has taken rooms on Madison Square, where he is at work on his plays. He hopes to produce The Nine Days’ Queen here, with Harriet Jay in the title rôle. He is writing a play for Adelaide Detchon. ___

The play for the American actress, Adelaide Detchon, turned out to be a two-act adaptation of Molière’s L’École des Femmes which was produced at London’s Comedy Theatre on 21st March 1885. ___

The New York Times (1 October, 1884) Mr. Robert Buchanan, who is now staying in this city, announces that Miss Harriett Jay, the young English actress and novelist, fresh from Drury-Lane, where she was leading lady last season, will shortly make her American début at the Madison-Square Theatre. Her first appearance will be in a series of special matinées, under the personal direction of Mr. Buchanan. Afterward she will create the title rôle in a new play, written by Mr. Buchanan specially for her, and accepted by Mr. Mallory for production after the run of the “Private Secretary.” ___

On 2nd October, Buchanan wrote to Augustin Daly (from his new address at 42 East 23rd Street, Madison Square) offering him two plays, a comedy which “is still without a home over here, and has as yet been submitted to no one” and A Madcap Prince, of which he says “I am going to make an effort, at any rate, to get that play done in New York while I am on the spot.” ___

The Salt Lake Daily Tribune (12 October, 1884) Robert Buchanan, dramatic author, expects to produce his new play entitled “Nine Days A Queen,” at the Madison Square shortly, with Robert Mantell in the leading part. ___

So, at the beginning of October, 1884, Buchanan appears to be considering productions of two of his old plays, which hadn’t been seen in America, A Madcap Prince and The Nine Days’ Queen, as well as two new comedies, one with Harriett Jay in the “title rôle”. However, none of these materialised during Buchanan’s stay in America. Of the comedies, the one offered to Daly could have been A Hero In Spite Of Himself (if one stretches the definition of ‘comedy’ and ignores Buchanan’s statement that it had “been submitted to no one”), but it may have been an early version of Fascination. The comedy which Mr. Mallory (of the Madison Square Theatre) had accepted might have been Lottie, which was an adaptation of Harriett Jay’s novel, Through The Stage Door, and which was produced at the Novelty Theatre in London on 20th November, and lasted a week. However, all of this is mere speculation. By November all had been settled - Harriett Jay would make her American début in a play, not written by her brother-in-law, but in which she had toured the provinces in 1881, and Buchanan’s new play would be produced by Lester Wallack. _____

Constance |

|

|

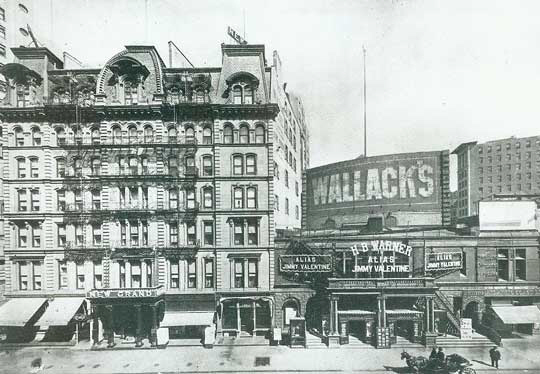

[Lester Wallack and below, Wallack’s Theatre, New York.] |

|

|

Following the rejection of A Hero in Spite of Himself by the producers of his first American success, Storm-Beaten, it is not surprising that Buchanan should approach Lester Wallack, the producer of his other American success, Lady Clare. There is some confusion about the genesis of Constance, which became Buchanan’s first theatrical venture during his American sojourn. In a letter to the New-York Daily Tribune (22/11/84) Buchanan admits taking “the central situation employed by Leon Gozlau, by Sardou and finally by myself”. However, a letter from Kate Munroe in The Era (6/12/84) draws a parallel with the Harriett Jay novel, A Marriage of Convenience which was serialised in the weekly magazine, The Lady’s Pictorial: A Newspaper for the Home from 12 July to 29 November, 1884. And an article from The Omaha Daily Bee (25/11/84) actually refers to Harriett Jay writing the final chapters of the novel for the magazine around the time that the play was being performed at Wallack’s Theatre.

The New York Times (19 October, 1884) THE ACTOR AND THE PLAY THE PLOT OF MR. ROBERT BUCHANAN’S NEW WORK. It is not yet decided what to call the new play which Mr. Wallack has purchased from Mr. Robert Buchanan, although it has been determined, as already foreshadowed in THE TIMES, to bring the piece out as the next production at Mr. Wallack’s theatre. The play itself appears to contain the elements of quite unusual strength. There is nothing conspicuously new in the story, but the plot seems to be very well constructed, and the indications are that the play is the best piece of dramatic work which has yet come from Mr. Buchanan’s pen. The story as told yesterday by Mr. Arthur Wallack is closely woven and interesting. The villain, who is one of the chief characters in the play, is a Spanish nobleman. Before the action of the piece begins he has eloped with the wife of another man, and having tired of her in due course has cast her aside and come to live in England. Here he has an opportunity to contract an advantageous marriage with a young girl whose grandmother is ambitious for an alliance with a family of noble lineage. The girl herself loves a young army surgeon, who loves her in return, and this affection is the only bar to the proposed marriage between herself and the Duke. The grandmother, who is not conspicuously soft-hearted where her own wishes are concerned, tells the girl that the father of the young man with whom she is in love was the direct cause of her mother’s death, and that to marry into that particular family would consequently be a crime against the memory she holds dear. Meanwhile the old woman has exercised her influence to the extent of getting the young surgeon ordered away to the Cape, where his regiment is stationed, and the coast is thus left clear for the Duke to prosecute his suit. Always near the Duke in some capacity or other, but at this time as his valet, is the husband of the woman he has ruined. This man is waiting in patience for a complete revenge, and he is satisfied to put up with any hardship and to endure any sacrifice that will aid him in ruining and bringing to his death the object of his hatred. The Duke succeeds in securing the hand of the young girl, who is moved through grief at what her aged relative has told her to accede to that person’s wishes in regard to an exalted marriage. In a short time the Spaniard grows weary of his young wife and begins to seek some method of so compromising her that he may have some reasonable, or at least plausible, excuse for putting her aside. The avenging valet, who divines his purpose, is moved partly by hatred for his supposititious master and partly by kindliness to the wife, who is a sweet and lovable woman, to thwart this design. The Duke undertakes a scheme to get his wife into questionable surroundings by offering to take her to a certain ball, then being ostensibly called away, and sending her a message to go without him. She sends to the Spanish Embassy to secure the escort of her husband’s friend, and while the bearer of her message is gone upon this errand her former lover enters her apartment. He has been wounded in an African engagement and sent home for purposes of recuperation. Not knowing the heroine has been married in his absence, he finds his way to her boudoir and in an impassioned scene pours out his love for her. She finally has the strength to check him, although she discovers the deception that has been practiced upon her. When she tells him that she has become the wife of another the shock is so great that his wound breaks out afresh, and he falls fainting to the floor as the valet rushes upon the scene to foretell the unexpected coming of the Duke. Anxious to save the innocent wife, he induces her to retire, and she leaves the stage as the Duke comes in. He finds what he supposes is the dead body of a man in his wife’s boudoir, and he orders his valet to fling it into the street as the curtain descends. It goes up again almost immediately, showing what appears to be the lover’s body lying on the sofa covered over with a rug. The Duchess is called in and accused of infidelity by her husband. There is a bitter scene between them, filled with denunciation on his part and denial upon hers, and upon their parting the act ends. The valet, in place of obeying the orders imposed upon him, has taken the unconscious lover to the house of a physician who figures in the play, and he is there restored to life and prospective strength. In the last act, the wife has proceeded to a convent in Brittany for the purpose of entering its doors for the rest of her life. The husband is there in pursuit of her, and the avenging valet is also on the ground. If the Duke does not recover his wife he is ruined, and in this complication the wronged husband of the woman he seduced years ago determines at last to strike. After a number of scenes between the various characters, working up to the final climax, the whilom valet declares his rightful identity and demands the satisfaction of mortal combat. He has brought the Duke’s dueling pistols with him, and proposes an immediate settlement of their account. The Duke at first refuses, but finally, stung with the taunts and insults of his adversary, he agrees to fight, and is shot dead. His wife, the young lover, and the other characters are on the stage. The Duchess, standing beneath the convent cross, sends a prayer to heaven for the forgiveness of the man who has so wronged her, and upon this picture the piece comes to an end, leaving an intimation that the principal personages will come together in the future. The underplot lies between the physician who restores the hero to health and a young girl who is full of life and animal spirits, and who has been designed by her friends for a convent career, which is precisely opposite to her inclinations. The physician is a general philanthropist who unwinds the tangled skein of the various characters and ultimately weds the spirited young lady. These two personages furnish the lighter portions of the piece, and form an entertaining contrast to the sombre incidents I have related. This play will be placed in rehearsal on Wednesday, and will be carefully prepared for production three weeks hence. Mr. Tearle, Miss Coghlan, and Mme. Ponisi, together with two other important players not yet decided upon, will be seen in this production. Mr. Goatcher is painting the scenery, of which there are two very pretty exterior sets, the sketches now being complete. ___

The New York Mirror (1 November, 1884 - p.7) Mr. Buchanan’s “Originality.” There is an air of freshness pervading the ordinary New York manager which must be particularly delightful to a gentleman like Mr. Robert Buchanan, who comes over here with a grip-sack stuffed with notoriety and old plays. In blissful innocence the manager accepts the one as reputation and the other as original productions, and part with his dollars as freely as though they were worth only fifty instead of eighty cents. Mr. Buchanan can seize an occasion and float to glory on it about as readily as any one in this city, but when he accepts the too prevalent impression among his fellow-countrymen that all the residents of New York are fools, he makes a slight mistake, and runs a serious risk of being “left.” Mr. Buchanan may be able to write an original play or two a week, merely as a matter of amusement, but if he has been in the habit of doing so he must keep them in the Safe Deposit vaults or in some equally secure spot, as up to present writing no one has ever seen them. He has been honoring the managers with calls, and taking orders for plays with a freedom that struck terror to the heart of the ordinary, every-day American dramatist; but his occupation in this fertile field is about gone and the spirit is exorcised. ___

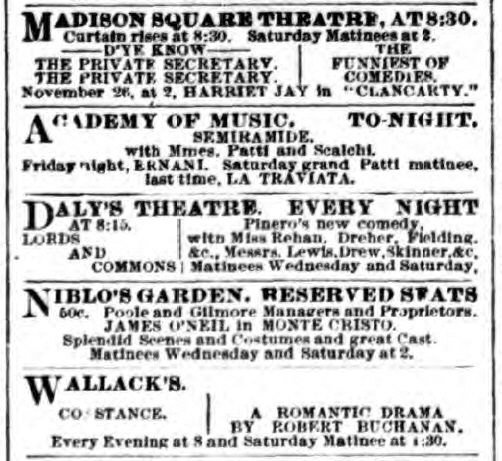

Brooklyn Eagle (16 November, 1884 - p.2) MR. LESTER WALLACK opened the regular season at his theater with a “new” play, by Robert Buchanan, called “Constance.” The central situation of the play is taken from that master playwriter of France, Sardou. The plot is from one of the plays of the late Leon Gozlan, and various other parts are familiar to old theater goers who have seen Augustine Daly’s adaptation of “Maison Neuve” and a play which had quite a run here some years ago under the name of “The White Cockade.” Most of the dialogue is so old that it might have been taken for any of the trite standard English melodramas and the characters are all conventional. With these trifling exceptions “Constance” is original with Mr. Buchanan. At any rate its performance served to bring out the most distinguished first night audience of the season, and, as the play was put on in the most sumptuous and lavish style, it is pictorially quite a go. The best applause of the evening was for the scene painter, who kindly came out and bowed several times during the first three acts. The action of the play was stopped, and the actors stood about like mummies while this robust, bald and rather pushing person strode forth to received the plaudits of the multitude. I am sorry to say that the multitude consisted of a claque stowed away judiciously in the rear of the house. In fact, it became so noisy at last that it was roundly hissed by the audience, and from that time on the scene painter was invisible. A new member of Mr. Wallack’s company—his name is Henly—did the only praiseworthy work among the men. He is not a great actor, but is a very conscientious one, and played the part of a Spanish duke very intelligently. This man, by the way, came over with the troop of British blondes who made such a disastrous failure at the Park Theater a month or so ago. From a British blonde at the Park to a Spanish duke at Wallack’s is quite a jump. Mr. Osmond Tearle, who is a red faced, mild eyed and far from romantic looking Englishman off the stage, stepped from behind the scenes made up as a Brazilian adventurer. The effect was startling. Mr. Tearle wore an extraordinary black mustache, his customary light eyebrows and a wild black wig. Above his forehead Mr. Tearle looked very much disordered, very unpoetical and very unhappy. That section of his face between his wig and his upper lip was mild, beneficent and sunny as an English May day. The lower section of his face, which was decorated by the black mustache, looked villainous and deep. The ensemble was rather curious. Mr. Tearle’s duties at Wallack’s Theater seem to be to kill Miss Coghlan’s cruel husbands. He did it this time with his usual finish and dispatch. Of the women in the cast, Miss Rose Coghlan is the only one who was at all successful. In the third act of the play, the scene which is taken from Sardou, there is a chance for a bit of strong and heroic acting; it brought out all of the powers of Mr. Wallack’s leading lady. When there is a chance for acting of this sort Miss Coghlan shows the metal of which she is made. She has grown considerably slighter since her trip to Europe and now has the figure of a girl. Her costumes were simply gorgeous. It is a pity that she has so few opportunities for heroic acting in the namby pamby plays produced at Wallack’s. What struck the audience most forcibly at the performance of this play was the entire artificiality of the actors. There was a garden scene in the first act, and the actors walked in one after the other, doffed their hats in response to the applause of the audience, doffed them when they addressed their sweethearts, doffed them when spoken to, and then took them off with an angular motion when mentioning the name of the Divinity. To see Mr. Kelcey make an appeal to his Creator, with one arm raised on high while he tipped his hat with the other hand as though acknowledging the salute of some girl on the other side of the stage, was not a solemn spectacle. The men all wore very new clothes, spoke with extraordinary deliberation, and proved that they were a lot of very common place actors in an extremely bad play. Mr. Buchanan, the “author” of the play, sat in a proscenium box ready to receive the calls for the author. He was not called. His sister in law, Harriet Jay, sat with him. She is very tall, blonde, and has rather sharp features. For some extraordinary reason the audience thought she was Ellen Terry, and the play was forgotten during the half hour following her arrival, while they gazed at her. She shielded her face with a huge white fan, so that people were a long while finding out that it was not Miss Terry. ___

Constance was not a success, running for just a fortnight from 11th to 25th November, 1884, and, as far as I know, the play was never produced in Britain or elsewhere |

|

|

[Adverts for Constance and Clancarty from The Daily Graphic (New York) (19 November, 1884).]

Buchanan’s Theatrical Ventures In America - continued

|

|

|

|

|

|

|