|

[From The Southend Strandard (3 April, 1902 - p.1).]

The Stage (10 April, 1902 - p.10)

SOUTHEND—EMPIRE.—The Southend Dramatic Society on Tuesday night gave a performance in aid of the Fund to provide a Permanent Memorial to the late Robert Buchanan, who had resided at Southend for a long period, and now rests in “God’s little acre by the sea,” beneath the sheltering wall of the Church of St. John. The local society decided to give performances on two nights—Tuesday and Wednesday—in aid of the Memorial Fund, and for such an occasion could not have presented a more attractive programme. Indeed, the curtain raiser was produced for the first time by permission of the author’s sister-in-law, Miss Harriett Jay. This was a poetical drama in one act, by Robert Buchanan, entitled:—

The Night Watch.

Heinrich von Auerbach . . . . Mr. Reginald Sewell

Vicomte de Lisle . . . . . . . . Mr. J. K. F. Picken

Hubert . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Mr. G. W. Taylor

Dr. Marton . . . . . . . . . . . . Mr. Reveirs-Hopkins

Irene de Grandfief . . . . . . . Mrs. Reveirs-Hopkins

This drama was admirably acted by a quintet of well-known amateurs; but it was not a cheerful opening for an evening’s entertainment. It was tragedy, as a contrast to the comedy to follow. Mrs. Reveirs-Hopkins cleverly interpreted the character of Irene de Grandfief, and Mr. Reginald Sewell appeared as Heinrich von Auerbach, who is supposed to have witnessed the death of the Vicomte de Lisle, to whom Irene is betrothed, and who, by a freak of fortune, is brought wounded to the chateau of which Irene is mistress. The participation of Heinrich in the events which led to the supposed death of her lover leads Irene to be tempted to allow Heinrich to die by neglect, but her better feelings hold sway, and as the curtain falls her lover returns well, and the scene closes with the usual conquest of meaner feelings with virtue triumphant. Buchanan’s Sweet Nancy was the chief feature of the programme. Mrs. Reveirs-Hopkins decidedly scored a success as an amateur in the part of Nancy; Mrs. Cardy Bluck made a charming Barbara, and the other sister, Teresa, became an admirable juvenile part in the hands of Miss Dora Seal. Mr. William Gray looked the character as Sir Roger Tempest, and acted admirably. Mr. Donald Gray was a very fair Frank Musgrave.

___

The Southend Standard (10 April, 1902 - p.5)

SOUTHEND DRAMATIC SOCIETY.

“SWEET NANCY” AND “THE NIGHT WATCH.”

A FINE PERFORMANCE.

Southend Dramatic Society did honour to the memory of a great playwright and, indeed, honoured itself when on Tuesday evening its members realistically pourtrayed at the Empire Theatre Robert Buchanan’s well-known work “Sweet Nancy,” and had the added privilege of placing before the public for the first time a poetical drama by the same writer, entitled “The Night Watch.”

Buchanan has large claims upon Southend. A resident here for years, he produced some of his most telling and capable literary work whilst living in the town. His wife died here, was buried here, and when the last summons came to the stern word-warrior, Buchanan chose to rest beside his wife, with a simple bit of green sod covering his burying-place and the wind from the sea he loved blowing freshly and strongly o’er it. Several in the Borough on the occasion of his burial favoured the idea that Southend should substantially honour the memory of its greatest resident and as an outcome an appeal for subscriptions was made by the Rev. T. Varney and Mr. Coulson Kernahan. The result was satisfactory in the sense that several subscriptions were obtained, but these came mostly from the literary and dramatic professions and it was with the object of eliciting greater support from the Southend public, as well as to afford financial aid itself, that Southend Dramatic Society gave the performance under review. If burgesses are hard put to it as to what form the Coronation permanent memorial should take, nothing could be more fitting than that the town should adopt the project through its Mayor and carry it to triumphant success, as represented, say, by a beautiful statue in Prittlewell Square, facing the mouth of the Thames.

The Theatre was crowded on Tuesday evening; the audience being both expectant and impatient, for it was twenty minutes past eight before the orchestra started and five minutes before that time had the bell been ringing. Miss Harriett Jay, as was related in our interview in last week’s “Southend Standard,” has been staying for the past few weeks in Southend and has kindly given her advice and assistance at the rehearsals and probably this factor alone had considerable effect, both in the excellent representations and the smoothness, ease, and accuracy with which everything went.

“THE NIGHT WATCH.”

“The Night Watch,” which began to the tune of the “Marseillaise”—a play in one act—was suggested to Buchanan from a poem by François Coppée. The scene is laid at the Chateau of Grandfief, in Normandy and the time is put at the German Invasion of France in 1870. There are five characters: Irene de Grandfief (Mrs. Reveirs Hopkins); Vicomte de Lisle, a volunteer in the French Army (Mr. Picken); Heinrich von Auerbach, a German Officer (Mr. Sewell); Hubert, a servant (Mr. G. Taylor) and Doctor Marton, a surgeon (Mr. Reveirs Hopkins). Shortly described, this new and powerful play opens with an interior view of the Antique Chamber in the Chateau Grandfief, with Hubert, a clownish servant, looking out of the window, joyfully welcoming the fall of snow; which he wishes would fall quickly enough to swallow up the Germans. His soliloquy is broken by the sound of gun shots and Irene (the heroine) enters. She bids the servant discover the cause of the firing. While he is gone the lady’s thoughts dwell on the whereabouts of her soldier lover, the Vicomte, who is serving as a volunteer with the French Army. His expected letter has not arrived and in the passion of her love she kneels before the oratory praying “Spirit of Heaven spare him! Restore him in the blessed light of peace and bring him soon!” Hubert hastily enters and brings the news that a skirmish near by had ended in a victory for the French and the capture of a German Uhlan officer. Dr. Marton dresses the wound and is afforded opportunity of declaring the Vicomte to be “he who yielded rank, wealth, and privilege and seized a sword in France’s hour of danger”—an act which would peculiarly appeal to Buchanan’s instincts. Irene nurses the Uhlan through the night and a phial of medicine is given her in order that she may serve him with ten drops four times an hour, so to keep him alive. The officer rouses from unconsciousness ad tells Irene how “yonder in Germany there is one who waits like her; a little maid with sunny, golden hair.” The climax is reached when he tells her that a month ago at Metz he killed a Frenchman: “We saw one standing as a sentinel. On hands and knees I crept unto him. Then, up-springing, stabbed him. He fell with scarce a groan.” The dying Frenchman implored his assailant to forward to the one he left behind a medallion which he wore. This Auerbach swore to do and he now hands it over to the girl to fulfil the mission. She examines it and finds it to be her lover’s. Then through the long night hours she struggles with her frenzied desire to kill the sick man, but a low voice points her to her “Duty!” and she administers the saving draught. As he recovers, Raoul, the missing lover, pale but eager, enters and clasps the girl in his arms and peace is made ’twixt Gaul and Teuton.

The dramatic situations which rolled in one upon the other as the climax is reached thrilled and interesting the audience, so that during the whole of the half-an-hour’s performance the artistes were not harassed by caustic remarks from the gallery of chilling indifference in the stalls. The part of the heroine is one full of possibilities and Mrs. Reveirs Hopkins realised them to the full, albeit her work was continuous and exhausting. Mr. Reveirs Hopkins had a subordinate part, but his “make-up” was excellent, as indeed, it always is. Mr. Sewell, as the German officer, had also a difficult role and the applause of the audience at the close should satisfy him as to his success, which was well deserved. It is no easy matter to satisfactorily “create” a part when lying prostrate on a bed and supposedly nearly dead with a gunshot wound. Mr. G. Taylor, as the servant, was entertaining and Mr. Picken did his little well.

“SWEET NANCY.”

“Sweet Nancy” runs to a livelier, merrier measure and the audience were at once in good humour with the first scene, wherein are found the sons and daughter of Mr. Gray (Mr. Reveirs-Hopkins) playing in approved tom-boyish fashion in a garden, until disturbed by their father. The sons were: Algernon Gray, Mr. Felis Seel; Bobby Gray, Mr. Fred Whisstock; James Gray, called “The Brat,” Master A. E. Lockington and the daughter, Teresa Gray, called “Tow, Tow,” Miss Dora Seel. Sir Roger Tempest (Mr. William Gray) quells a stormy scene between father and children and Mrs. Gray (Mrs. Read) also appears. “Nancy” (Mrs. Reveirs Hopkins) was greeted with cheers and she was pretty and girlish with her match-making father when he wanted her to lunch with him and Sir Roger “dressed in her best.” The obvious object of the ruse was quickly penetrated when she was chaffed by her brothers and sisters, who, with a keen eye to the main chance, bargained for shooting and hunting as their share of the spoil from the prospective union. The situation was, indeed charmingly amusing when Sir Roger discovered “Sweet Nancy” left stranded on a high wall by her mischievous brothers, but where, however, she progresses extremely well in her determination to marry a man with money and she and Sir Roger go in the fashion of “Darby and Joan” to lunch, preceded by Barbara (Mrs. W. Cardy Bluck) and Frank Musgrave, Sir Roger’s ward, (Mr. Donald Gray). The courtships cause great dismay among the children and Algernon gives his emphatic opinion upon the subject, preluded by the dramatic “Friends, Romans, countrymen—stand to attention!” In due time Sir Roger sues for Nancy’s hand and if the latter is seemingly coy, her secret intention is realised and she gives her promise. With seductive guile she gains the boys over to the alliance by promises of hunters and shooting galore. Scene 1 was most effective and the curtain descended to the hearty cheers of the audience.

Scene II depicts the drawing room of Sir Roger, and therein are introduced for the first time Pemberton, the Butler, Mr. Sidney Lucking, and Mrs. Huntley (Mrs. F. J. Horne), a fashionable invalid with a husband at the front. Nancy, as mistress of the house, is beautifully pourtrayed by Mrs. Reveirs Hopkins and the fun waxes furious when Mr. Gray excitedly declaims against the Railway Company for the loss of a hat box and declares therefore that “England is going to the dogs.” Musgrave, the languid lover of Barbara, but a real lover of Nancy, instils suspicion in the heart of the latter by a reference to Sir Roger’s friend, Mrs. Huntley, as a “grass” widow, and on whom Nancy retaliates by telling Barbara to take him away and bury him, a sally to the vast enjoyment to the audience. Sir Roger has received orders to prepare for active service and his interviews with Mrs. Huntley raise the ire of his bride, who wants a separation, a divorce! The misunderstanding was only cleared up in the farewell scene, which was a triumph and Mrs. Reveirs Hopkins acted superbly.

Scene III. The circumvention of the wiles of Musgrave and the insinuations of the “grass” widow occupy all the capacities of Nancy, but in the end, as usual, all turns out well, husband and wife being reconciled and made happy.

The whole play was ably presented and with such a well-balanced caste it would be unnecessary to single out a single name for mention, but undoubtedly Mrs. Reveirs Hopkins scored a great success. Sir Roger was capably taken by Mr. W. Gray and Algy by Mr. Felix Seel was very good.

___

The New York Times (26 April, 1902)

Memorial to Robert Buchanan.

A notice signed by the Rev. Thomas Varney, St. John’s Parish Church, Southend-on-Sea, and Coulson Kernahan, from the same neighborhood, representing England, and by the Rev. Walter E. Bentley, for America, invites the public to subscribe to the memorial to the late poet and dramatist, Robert Buchanan, who is buried in Southend-on-Sea, England, where for several years he had made his home. The Mayor of the town, Mr. J. Francis, is acting as Treasurer, and contributions from Americans may be sent to the editor of THE NEW YORK TIMES SATURDAY REVIEW OF BOOKS. The relatives of Mr. Buchanan suggest that individual subscriptions be limited to a small sum, so that the poet’s humble admirers, of whom there are many, may not hesitate to contribute the small amounts they can spare. Mr. Bentley has been giving a course of sermons at All Souls’ Church, on “Our Life After Death.” Last October, while he was General Secretary of the Actors’ Church Alliance, he preached on “My Summer’s Tour in behalf of the Actors’ Church Union of England and Its Results.”

___

The Stage (22 May, 1902 - p.13)

Miss Harriett Jay’s life of Robert Buchanan will not be published until after the Coronation. Miss Jay, who has just written a play with Mdme. Sarah Grand, has been staying at Southend while completing the work. Among the contributors to the Buchanan Memorial Fund are many eminent names, notably that of Mr. Herbert Spencer. It is understood that many of the dramatist’s admirers incline towards the erection of a drinking fountain in Southend, opposite Buchanan’s former residence, as the most suitable form for the memorial.

___

The Echo (7 June, 1902)

THE LATE ROBERT BUCHANAN.

We are asked to state that the subscription list of the proposed memorial to the late Mr. Robert Buchanan will shortly be closed. The movement has, we learn, received the support of many distinguished men and women connected with the literary and dramatic professions; and a committee will shortly be appointed to consider what form the memorial shall take.

In the meantime the honorary secretaries will be grateful if intending subscribers, who have not yet contributed, will be so good as to communicate with the Rev. Thomas Varney, St. Mark’s Hostel, Southend-on-Sea, or with Mr. Coulson Kernahan, the Savage Club, Adelphi-terrace, London.

___

The Southend Standard (26 March, 1903 - p.8)

We understand that the main purpose of the lecture on Robert Buchanan, which takes place to-night, is to enable Southend people to gain a more extended knowledge of Buchanan’s works, more especially of his poetry. For a town to be honoured as the burial place of a great man, and its citizens to be in ignorance of his greatness, must be a reproach until removed. Those who attend the lecture may expect a literary treat, as the Rev. Conrad Noel is a very clever critic and is on the staff of the “Daily News.” He inherits great poetical gifts from his father, the Hon. Roden Noel, brother of the late Earl of Gainsborough. The lecturer has consented to give the lecture out of respect of his father’s memory, as the latter was a personal friend of Robert Buchanan, and also from a desire to aid the Memorial Fund. The proceeds of the lecture are to be devoted to that purpose. Nearly £50 more will be required to meet the expenses, we learn from the Treasurer, Mr. Alderman Francis. A sketch of the Memorial appears in the recently published biography of Robert Buchanan. The successful authoress of this work, Miss Harriett Jay, hopes to be present at the lecture.

___

The Oban Times (11 July, 1903 - p.5)

I am asked to state that the subscription list for the memorial to be erected at Southend-on-Sea over the grave of the late distinguished novelist, playwright, and poet, Robert Buchanan, is still open, and a sum of £50 is required to complete the scheme. The memorial to this, one of Scotland’s most distinguished sons, will be unveiled by Mr. T. P. O’Connor, M.P., at the end of July. Subscriptions should be sent to the Rev. Thomas Varney, late of Southend, now vicar of the New Parish at Beckton Road, Canning Town, London, E., who was, I believe, the originator of the movement. Mr Varney, it may be said, is an Englishman, and the memorial has practically been paid for by Englishmen. It would, therefore, be a gracious act if Scotsmen now came forward and showed their appreciation of what has been done.

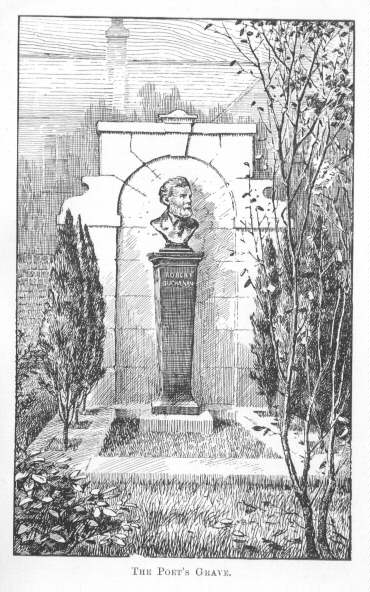

The monument has been designed by Mr Morley Horder, of New Bond Street, and the bust, which forms the central feature of the memorial, is by Mr Egan. All Mr Buchanan’s work is of interest, not only to Scotsmen, but to all who love good verse or good novels, or who admire a life spent largely in protesting against the shallow conventions and the cruel social wrongs that have taken the reality, the sincerity, from our national life, and which threaten to rob it of its splendid possibilities. Of particular interest to Scotsmen, perhaps, is his “Hebrid Isles,” in which he speaks with so much enthusiasm of his Keltic antecedents, and of the sad fate which had driven the Highlander from his home.

Not only Buchanan himself, but his father and mother, were interesting personalities. His father was the editor of the “Glasgow Sentinel,” then partly owned b y William Love, whose office was the gathering place for all sturdy fighters for liberty of thought and speech. He later owned and edited the “Glasgow Penny Post,” and “Glasgow Times,” and had, as his chief assistant, Hugh MacDonald, who was also a disciple of the famous Robert Owen.

___

The Oban Times (18 July, 1903 - p.5)

THE ROBERT BUCHANAN MEMORIAL.

Apropos of the notice in last week’s “Oban Times” regarding the Robert Buchanan Memorial at Southend, a writer in a city contemporary, remarking on the same subject, thinks the £50 required to complete the memorial might well be raised amongst the Highlanders of Glasgow. Doubtless it could, if gone about in the right way, but, and with due reverence be it spoken, Buchanan is not a much-talked-of man amongst the Celts in the city, and to raise £50 amongst them may not be the easiest of things. Our contemporary scribe, however, evidently knows his Buchanan well, and in appealing for the required sum he asks—“What of the city Highlanders, whose wrongs as a race stirred the fiery soul of the poet? Cairns, crosses, pyramids ad other monumental piles Highlanders have erected in plenty to the memory of their own particular bards, and they might now add a stone to Buchanan’s cairn, as it were.” That they could certainly do.

___

The Southend Standard (23 July, 1903 - p.2)

THE BUCHANAN MEMORIAL.

Sir.—Will you kindly make it known that, as the space in St. John’s Churchyard is limited, admission to the unveiling of the Robert Buchanan Memorial on Saturday, 25th inst., will be by ticket only?

Those ladies and gentlemen who intend being present are requested to present their invitation cards not later than 3-45 p.m.

All those who feel an interest in the life work of the late poet are cordially invited to attend the public meeting in the Church Room (St. John’s), at 4-15 p.m.

Yours faithfully,

A. E. REVEIRS-HOPKINS,

Hon. Secretary.

___

The Southend Standard (23 July, 1903 - p.7)

SOUTHEND COLLEGE FOR GIRLS.

PRIZES DISTRIBUTED BY MISS HARRIETT JAY.

In spite of Saturday’s wet weather, Miss O’Meara, the headmistress of Southend College for Girls, held her “At Home” to parents and friends in the grounds of the College on that day. Her guests were received in a large marquee, and were there entertained by the pupils with music, drama, and gymnastics—to say nothing of refreshments, in “circulating” which among the various tables they proved themselves dainty and efficient waitresses. The selections from Shakesperian plays were most successfully presented, the impersonations showing that the pupils include some promising amateur actors and actresses. A French version of “Cinderella” was quite a novelty, and was thoroughly enjoyed even by those not conversant with that tongue, for with such clever little impersonators, who could fail to recognise the charming little “Cinders,” her two ugly sisters, the gallant prince, and other characters in the evergreen nursery tale?

After tea the prizes for study and sports were presented by Miss Harriett Jay. A bouquet having been handed to Miss O’Meara on behalf of the pupils, that lady suitably thanked the donors and then expressed her (and their) welcome to Miss Jay. She was a literary celebrity, and they welcomed her especially because they had literary aspirations themselves. They had a school magazine, of which she was the unfortunate editress. Novelettes, articles, and stories “to be continued in our next” were placed in a box outside her study door. They had not arrived at printing yet, because printing was so dear, but no doubt it would come. They wanted to have had with them their hon. chaplain and dear friend, Mr. Varney, but as he could not come he sent his friend, Miss Jay. They had had a very successful year; taking it altogether the school work had been very good. They had said that the first lady to distribute the prizes should be a B.A. of their own. They had been making a B.A. for years, but she wasn’t made yet and they could not wait any longer.

Miss Jay said she knew she was not the person they wished to have had. They were all very anxious to welcome their old friend, Mr. Varney; no one regretted his absence more than she did. It was only when she found it quite impossible to get him to come that she consented to be the bearer of his apologies and good wishes. It was not always a pleasant duty to be the bearer of apologies and good wishes. Last summer a lady she was staying with arranged to visit a friend that she had not seen for years. When the day arrived she was prostrated with nervous headache. So she asked her to drive over and make her apologies. She assured her her friend was most anxious to see her. She went, but her welcome was not exactly cordial. The expression on that lady’s face when she rushed out, all eagerness to meet a friend, and found a stranger the only occupant of the carriage, could be better imagined than described. They had often laughed over it since, but it was not very funny at the time. She should like to congratulate those girls who had been fortunate enough to win prizes, and also to speak a word of encouragement to those whose names did not appear in the list. She trusted that their non-success would not discourage them, but rather act as an incentive to future work. They were all workers and strugglers for the great prizes of life, and if they failed to win them at their first attempt there was no reason why they should not try again—and succeed.

Miss O’Meara said she would only make two comments—that the nervous headache must have been caused by want of physical drill and lack of exercise in the open air, and that she felt sure Miss Jay did not feel they had given her the cold welcome she received on the occasion of which she spoke.

Councillor Morley Hill moved, Mr. C. H. Hulls seconded, and it was carried with “cheers from the rear,” where the pupils were assembled, that their grateful thanks be accorded to Miss Jay for coming down from London to distribute the prizes.

Miss Jay, in responding, said she was glad to be able to tell Mr. Varney that she had done his work satisfactorily.

The following was the prize list:— . . .

[And there I’ll leave it, although I must note that in the ‘Prizes for Sports’, the ‘Stilt race’ was won by D. Brown, and the ‘Bicycle Tortoise’ by M. Milton.]

___

I also came across the following letter for sale on the David J. Holmes Autographs site:

KERNAHAN, COULSON. ALS, 2pp (grey paper), 8vo, on printed letterhead of “Thrums,” Westcliff-On-Sea, Essex, 16 August, n.y. To an unidentified woman, thanking her for a subscription to the Robert Buchanan Memorial, and writing: “I have sent your letter to the Mayor. . . . Your estimate of Buchanan the man is I think very true. . . . I only wish that in the case of men like Mr. Buchanan others would follow your example & say the appreciative and helpful word while the ears to which it is addressed are open to hear. Why should we wait till the man has passed when he no longer needs human sympathy & appreciation?. . .”

_____

The memorial to Buchanan was unveiled on Saturday, 25th July, 1903.

The Observer (26 July, 1903 - p.7)

MEMORIAL TO ROBERT BUCHANAN.—Yesterday afternoon, in the presence of a large congregation, a memorial to the late Robert Buchanan, which has been erected in St. John’s Churchyard, Southend, was unveiled. Mr. T. P. O’Connor, M.P., and Miss Harriet Jay (the deceased poet’s sister-in-law) approached the monument together, and as Miss Jay removed the covering, Mr. O’Connor declared the bust unveiled, and handed it over to the custody of the vicar and churchwardens. He afterwards gave an address.

___

The Referee (26 July, 1903 - p.4)

MEMORIAL TO ROBERT BUCHANAN.

YESTERDAY afternoon, in the presence of a distinguished gathering, Mr. T. P. O’Connor, M.P., unveiled a memorial to the late Mr. Robert Buchanan in St. John’s Churchyard, Southend. The brightest of summer weather prevailed, and the company included the Mayor and Mayoress of Southend, Colonel Tufnell, M.P., and Mrs. Tufnell, Sir F. C. Rasch, M.P., and Lady Rasch, the Aldermen and Councillors, Mr. George R. Sims, and many well-known authors and journalists. The monument is rigidly simple and dignified in design, and consists of a stone screen fronted by a black marble pedestal on which is a bronze bust of the deceased author. The inscription states that it is erected to the memory of “Robert Buchanan, poet, novelist, and dramatist,” and the following lines from one of his poems, “The City of Dreams,” are added:

In dark and troubled dreams of thee;

Then, with one waft of thy bright wing,

Awaken me!

Mr. O’Connor, in a eulogistic address, spoke of Mr. Buchanan’s life, and pathetically alluded to the tragic side of that author’s experiences. He mentioned that twenty-two years ago Mr. Buchanan laid his young and beautiful wife in St. John’s Churchyard, Southend. More recently Mr. Buchanan’s mother was buried in the same grave.

___

The Times (27 July, 1903 - p.9)

A memorial to Robert Buchanan, the poet and dramatist, consisting of a bust, was unveiled on Saturday by Mr. T. P. O’Connor, M.P., in St. John’s Churchyard, Southend-on-Sea, where Buchanan and his wife and mother were buried. The bust stands on a granite pedestal, and at the back is a stone screen, while yew trees protect the sides. Mr. George R. Sims was present at the unveiling, in addition to the poet’s sister-in-law, Miss Harriet Jay, the Mayor and Mayoress of Southend, Sir F. C. Rusch, M.P., Colonel Tufnell, M.P., and Mrs. Tufnell. After the gift had been formally handed over to the vicar and churchwardens on behalf of the subscribers, Mr. O’Connor gave an address in the schoolroom descriptive of the lives of Buchanan and his wife and mother. He observed that Buchanan had parents who devoted themselves to what they considered to be right opinions and the benefiting of their fellow men and women. They evidently, however, belonged to that great and imperishable race of dreamers who in the pursuit of the welfare of others forgot their own. Like his father, Buchanan never learned the art of compound addition. Whatever money he made disappeared quickly. Mr. O’Connor pointed out in reference to Buchanan’s attitude that there were always a number of false reputations. It required some clear voice to remind the public that the number of copies sold must not always be taken as the eternal verdict of literature on the quality of the writer. A vote of thanks to Mr. O’Connor was passed at the close.

___

The Standard (27 July, 1903 - p.3)

MEMORIAL TO ROBERT BUCHANAN.

Mr. T. P. O’Connor, M.P., on Saturday, unveiled, Southend-on-Sea, a memorial to Robert Buchanan, the poet and dramatist, who was buried in St. John’s Churchyard in the grave containing the remains of his wife and mother. A bust, modelled by Mr. Egan, of London, forms a striking likeness of the poet. It stands on a granite pedestal, and has a back screen of stone, and is inscribed with a verse from Buchanan’s “City of Dreams.” Among those who attended the ceremony were Miss Harriet Jay, the Mayor and Mayoress of Southend, Colonel Edward Tufnell, M.P., and Mrs. Tufnell, Sir F. Rasch, M.P., Mr. George R. Sims, the Rev. Conrad Noel, Mr. P. McDermott, Mr. Alderman J. Francis, Treasurer of the Memorial Fund, Mr. A. E. Reveirs-Hopkins, hon. sec. Mr. O’Connor, on behalf of the subscribers, formally handed over the gift to the Vicar and Churchwardens, and afterwards, in the school-room, delivered an address on the poet and his wife and mother. There seemed to have been a general impression, he said, that because Buchanan had some very hard days in his early youth he was a man who, so to speak, came from the gutter. That was not correct: the parentage of Robert Buchanan was one of which any man might have been proud, and he had the best of all heritages—fine health, a soft and refined character, and love of the noble and the ideal. Buchanan, like his father, never learned the art of compound addition; he was chronically, hopelessly, eternally hard up. Whatever money he made disappeared quickly, and the result was that painful combination of the drudge and the spendthrift. He was too busy and too much of a drudge ever to be at his best, or to achieve that greater and higher fame he ought to have reached. There were authors who sold by hundreds of thousands who were really not fit to write for kitchen maids, and it required some clear voice to remind the public that the number of copies sold must not always be taken as the eternal verdict of literature on the quality of the writer. Sometimes Buchanan was wrong —perhaps usually he was wrong—but very frequently he was right, and in days when literary criticism was so ready to accept the idols of the literary mob, it was well that some such voice as his should be raised in protestation and in protection of true literary value. Mr. O’Connor also dealt with the lives of the poet’s wife and mother, remarking of the former that her character as woman and wife would always stand forth as one of the most beautiful that human life had ever presented.

___

The Yorkshire Evening Post (27 July, 1903 - p.4)

“T. P.” ON CERTAIN POPULAR AUTHORS.

Mr. T. P. O’Connor M.P., on Saturday unveiled, at Southend-on-Sea, a memorial to Robert Buchanan, the poet dramatist. In a speech, he said: Buchanan, like his father, never learned the art of compound addition; he was chronically, hopelessly, eternally hard up. Whatever money he made disappeared quickly, and the result was that painful combination of the drudge and the spendthrift. He was too busy and too much of a drudge ever to be at his best, or to achieve that greater and higher fame he ought to have reached. There were authors who sold by hundreds of thousands who were really not fit to write for kitchenmaids, and it required some clear voice to remind the public that the number of copies sold must not always be taken as the eternal verdict of literature on the quality of the writer.

___

The Aberdeen Weekly Journal (29 July, 1903 - p.7)

ROB BUCHANAN.

It was a happy selection the choosing of Mr T. P. O’Connor to unveil the memorial to the late Mr Robert Buchanan in St John’s Churchyard, Southend, on Saturday. Both men came to London in a penniless condition. Buchanan and his chum David Gray tramped from Glasgow to the Metropolis, and “T. P.” has told the story of how he himself had solved the problem of living in London on sixpence a day. There was this marked difference between the two men: Both made fortunes, but the initial act of O’Connor when he made his first successful hit was to secure himself a competency in the shape of an annuity to provide against any future contingency. Buchanan frittered away his means in speculation and horse-racing, and died as poor as he began.

___

The Southend Standard (30 July, 1903 - p.3)

ROBERT BUCHANAN.

_____

THE MEMORIAL IN ST. JOHN BAPTIST

CHURCHYARD, SOUTHEND.

UNVEILING BY MR. T. P. O’CONNOR.

On Saturday afternoon, in St. John Baptist Churchyard, Southend, Mr. T. P. O’Connor unveiled the bust of the late Robert Buchanan which has been erected as a memorial to the great poet, novelist, and dramatist, at the grave where he lies buried with Margaret Buchanan, his mother, and Mary Buchanan, his wife. With Mr. O’Connor came others whose names figure in the world of literature, including Mr. George R. Sims, with whom Buchanan collaborated in the writing of Adelphi plays, Miss Harriett Jay, Rev. Conrad Noel, Dr. Gorham, of Clapham, Mr. R. E. and Mrs. Francillon, Mr. William Holles and others.

The memorial, which was designed by Mr. P. Morley Horder, consists of a bronze bust upon a black Scotch granite pedestal, backed by a classic stone screen. The bust, which was generally admired, was the work of Mr. Egan. The inscription reads:

ROBERT BUCHANAN.

Poet, novelist, and dramatist.

Born at Caverswall, Lancs., on 18th August, 1841.

Died in London, 10th June, 1901.

May he rise again.

Forget me not, but come, O King,

And find me softly slumbering

In dark and troubled dreams of Thee,

Then in one waft of Thy bright wing,

Awaken me.

“City of Dreams,”

by

Robert Buchanan.

After life’s fitful fever, they sleep well.

_____

MARGARET BUCHANAN,

(his mother)

Who died in London on 5th November, 1894.

Aged 78 years.

_____

MARY BUCHANAN,

(his wife).

Who died at Southend-on-Sea on the 7th

November, 1881, Aged 36 years.

The arrangements for the ceremony had been admirably made by Mr. Reveirs-Hopkins, who had been considerably assisted by the Rev. T. Varney and Mr. Coulson Kernahan, co-secretaries, who unfortunately could not be present. Mr. O’Connor and party arrived at four o’clock and proceeded immediately to the grave, where was gathered a large company, among whom were: The Mayor and Mayoress, Sir F. Carne Rasch, Bart., M.P., Mr[s]. Rasch, Col. Tufnell, M.P., and Mrs. Tufnell, Revs. E. R. Monck-Mason, E. Hamilton, Dr. A. C. Waters, J.P., Alderman Brightwell, J.P., Mr. W. Lloyd Wise, J.P., Mr. T. Whur, J.P., Alderman Francis, Mr. T. J. Sharland, Col. D. C. Lamb, Mr. J. Hitchcock, Mr. A. J. Connabeer, Councillor Hewitt, Mr. G. Scott, and others.

Arrived at the graveside, Mr. Reveirs-Hopkins said: Mr. O’Connor, I have very much pleasure in asking you, on behalf of the subscribers to the fund, to unveil this memorial, and after you have done so to formally give it over to the charge of the Vicar and Churchwarden of this Church for safe keeping.

Mr. O’Connor then reverently removed the purple covering from the bust, and said “I hereby declare this bust unveiled and deliver it into the safe keeping of the Vicar and Churchwardens of this parish.” During the unveiling Miss Jay stood at the side of the memorial.

The company then adjourned to the Parochial Hall.

The Mayor, who took the chair, said he was sure they would all be anxious to hear the gentleman who had come to address them, and he had very much pleasure in calling upon Mr. T. P. O’Connor to give his address.

Mr. O’Connor, who was enthusiastically received, having read the inscription on the memorial, said: I come this afternoon to speak of Robert Buchanan and of the two women with whom his name is associated rather than of the poet and his works. It is impossible, whatever effort may be made, to entirely separate a man from his writings. The world will insist on knowing how far he has lived up to the gospel he himself has taught. And if a man hold a prominent position, as an eminent man of letters always does hold, the world will desire to see if his life can give forth any lessons for the guidance of the lives of others. I make no apology, then, for speaking mainly, if not almost entirely, of Robert Buchanan the man. My sketch of his life must necessarily be brief and hurried. Robert Buchanan, though in many respects he was Scotch of the Scotch, was, as a matter of fact, born in England. His place of birth, as you know from the inscription on his tomb, was Caverswall, in Lancashire, and he was born there in the year 1841. His parentage, to a certain extent, is an indication of and a preparation for his career. It seems to have been a general impression that because he had some very hard days in his early youth, he was a man, so to speak, that came from the gutter. That is not correct. The parentage of Robert Buchanan was one of which any man might have been proud. He had the best of all heritages, a sound and refined character and a love of the noble and the ideal. His father was a remarkable man in his way, and was, indeed, to a certain extent, both the outcome and symbol of the times in which he lived. May I, in a few hurried sentences, recall to you the condition of society and the country generally in the period at which Robert Buchanan was born? These years of the Forties were hard years for the people of this country and especially the poor of this country. Few people at that time had any of the comforts which the masses of the people now fortunately enjoy. Meat was almost unknown in the homes of the poor. Clothing was bad. There was very little education. There was no newspaper and there was very little reading. The government of the country, to a large extent, was in the hands of a very small minority of the people of the country, and the result of it was that the England of the Forties was a very unhappy and a very poverty stricken land. It was a period, accordingly, which was sure to produce that race of ardent and dreamy and sometimes somewhat fanciful reformers which such a period always brings forth. One of the products of that period was Robert Owen. Though practically unknown to this generation, his was a name very widely known in the period to which he belonged. He was one of those ardent reformers who was not satisfied with a slight change in the conditions of humanity. He thought that he had discovered the panacea by which all human ills could be prevented. He was a Socialist, a rebel against the accepted authorities in politics, in Society and in Creed, and he went around the country preaching the gospel according to his lights. This was a gospel which was sure to fascinate young men of ardent imaginations and hopes, and among others it reached a small town in Ayrshire where a man, named Buchanan, was following the trade of a tailor. The Scotch race, as we all know, are a singular combination of ardour and frigidity, of cold business sense and yet of zeal, sometimes fiery zeal, in the pursuit of dreams and ideals. That race is also distinguished from most of the rest of the world by the extraordinary depth to which love of learning, refinement, manners, and ideals descends. This poor tailor in a small country Scotch town was really of the stuff of which great scholars and great martyrs are often made. He read the appeals of Robert Owen, he was dazzled by the visions of a new world, and, giving up his shop, he travelled all the way to England and enrolled himself with Robert Owen. When he got to Staffordshire he very soon made the acquaintance of a woman whose upbringing was very much the same as his own. There was in the town of Stoke a popular character of the time known as Lawyer Williams. He hoped he would not offend any susceptibilities when he said he was distinguished by the not unusual title of an honest solicitor. He was know as a man whose hand and whose advice were open to everybody, especially to the oppressed, the helpless, and the weak, and the result of it was that he was known as the poor man’s lawyer. He also shared the opinions, both social and religious, of Robert Owen, and was one of his ardent disciples. In this way Robert Buchanan’s father and Lawyer Williams were naturally brought into contact with one another. Mr. Williams had a daughter, and that daughter became Buchanan’s wife, and it was of these parents that Robert Buchanan was born. Now, ladies and gentlemen, I venture to call that a very fine title to aristocracy, because both the father and mother of Robert Buchanan were people devoted to the attainment of what they considered right and to the benefit of their fellow men. (Applause.) One must, of course, immediately add that it was a parentage which was very ill calculated to lead to the material and worldly success of their son. Both the father and mother belonged to that great race of dreamers who, in the pursuit of the welfare of others, sometimes forget their own. A reformer of the public purse has never been a very good guardian of the private purse, and many of the mistakes and weaknesses and some of the misfortunes of Robert Buchanan’s life can easily be traced to the father who left his shop to follow Robert Owen and his mother, the daughter of the lawyer who held unpopular and heterodox opinions. Buchanan the elder displayed a quality which was also remarkable in his son—that is, a singular versatility. Few lives have given such a remarkable example of that power of courageously adapting himself to all kinds of circumstances as the life of Robert Buchanan’s father. He was a tailor, as we have seen. He was a labourer, a shorthand reporter, a bookseller, and he wound up by writing what we call in the profession of letters “penny dreadfuls” for popular magazines and weeklies. And in all three different vicissitudes of his life he showed a quality which was also to be found in his son—that is, a spirit of dauntless and unconquerable hopefulness. In 1841 Robert Buchanan was born, and here is one of the remarkable things about it. As you will see, hew as born and brought up in a surrounding that was entirely free from the ordinary and accepted religious belief. I do not know that I should described Buchanan’s father as an atheist, but certainly he was what they would call an unbeliever. And Robert Buchanan’s mother was of the same way of thinking. And yet it is a curious thing that Robert Buchanan, though he followed and maintained some of the opinions of his people, really diverged widely in the course of his life from some of their most accepted doctrines. He always was more of a spiritualist than a materialist, and he always leaned to the doctrine of the imperishableness and immortality of the soul. His early days were days of prosperity. His father returned to his native country and settled down in Glasgow. He there became part proprietor of a prosperous newspaper and apparently his future was assured. Like his son he was hopeful and he established two other papers. Like the son, he never was able to master the very simple problem of compound addition. The family apparently had all the prospects of what is now one of the most valuable of inheritances in this country—a prosperous newspaper, and the result of it was that Robert Buchanan was brought up in somewhat expensive tastes, was sent to a somewhat expensive school, and had the advantage of a university education. These surroundings of his will be found faithfully reflected in his after life. He will be found to have shown some of the speculative, not to say gambling, propensities of his father. A life of luxury was inherent in him—up to 18 years of age his story is a story of almost unbroken prosperity. His mother was one of the best mothers a son was ever blest with, and in the life of Robert Buchanan I know nothing more beautiful than the relations between him and his mother. In Scotland, fortunately, the university is at the door of the poor. (Applause.) It is more so now than ever, since the generosity of Mr. Carnegie has practically made university education free to nearly every child in Scotland. May I, without offending anyone, express the hope that we shall see the age when university education will be at the door of every child in England.

THE THEATRE AND EDUCATION.

There was another agency in the education of Robert Buchanan, and that was the theatre. I know that a large number of very earnest and good people have a great dread sometimes and positive hatred of the theatre. And so far as the theatre merely lends itself to the lower part of human nature that is a feeling that everybody can comprehend. But the theatre is, and must be. one of the great teachers of the people in a country like ours, (Hear, hear and applause.) I am sure that nobody will deny that in listening to one of the plays of a great author one may learn some of the highest and noblest doctrines and teachings of life. (Applause.) certainly Robert Buchanan never denied that to the theatre he owed some of the best part of his education. He was especially moved by “Lear,” that most wonderful of Shakespeare’s plays, and summing up the effect of that play upon him he says “I first gained from it that perception of the piteousness of life which has been the inspiration of all my writings,” and I say that was one of the noblest lessons a man can learn from any teacher or in any place.

At the age of eighteen the clouds which had been gathering over the home of the Buchanans of Glasgow broke, and suddenly Buchanan found himself a penniless boy. In Scotland, bankruptcy does not proceed with quite the same slowness of step as Madame Humbert found it proceeded in the jurisprudence of France—(laughter)—and before many weeks the Buchanans were practically houseless and homeless. It was then that Buchanan formed the resolution which many a young Scotsman before him had formed and many another Scotsman has formed since—he resolved to come to London to seek his fortune. You can understand I find something always pathetic in that rush of the inexperienced provincial to the metropolis of the world in search of fortune. Many fail, a few succeed, and even those who succeed have usually to pass through a period of stress and suffering and sometimes of hunger that poisons for ever the success they may afterwards gain. Of the men who came to London in that period few were less equipped by fortune for the struggle than Robert Buchanan.

EARLY STRUGGLES IN LONDON.

He had only a few shillings in his pocket. He was very glad to take a third class ticket and to travel through all the dreary night. He says himself that in the hours of darkness he wept as he thought of the mother and the home he had left behind and of the dark and uncertain future that lay before him. He had one possession which is somewhat characteristic both of his mother and himself. That is to say, he had a large supply of very good clothes, and among these clothes was a luxurious dressing gown, which I am sure was the pride both of his mother and of himself. It was the most gorgeous piece of apparel that lit up the dinginess of his lodgings. Buchanan wandered through London on that first memorable day, but he found no familiar or friendly face. He lay down in Regent’s Park to sleep. As he lay there he suddenly became conscious of a pair of very keen, bright eyes steadfastly looking at him. It was a companion in misfortune. It was a companion whose exterior certainly was not very attractive, but he was one of those friendless but friendly souls that one meets in all parts of London. In the end he offered to accompany Buchanan to a lodging house in the East End of London. It was in this low lodging house, or as Buchanan calls it, thieves’ kitchen, that the great poet and novelist spent his first night in London. Do not let us pity Robert Buchanan too much as we see him in the Thieves’ Kitchen in the East End of London. When he was at the thieves’ kitchen he was perhaps at the most useful of all universities, for the literary man especially, the university of life and especially the life of the poor and the struggling. It was there that he learnt some of those lessons of tenderness and humanity which he preached consistently throughout his life.

LITERATURE—THEN AND NOW.

Now here may I pause for a moment to say that in one respect the literature of the second half of the nineteenth century is very different from most of the literature that has gone before. I think anyone who reads the literature of the eighteenth century will above all be struck by its narrowness both of range and of sympathy. It deals almost entirely with the lives of the rich, the aristocratic, and the well-to-do, and whenever it does happen to come across any of the poor it sees only the sordid and the cruel and the evil side of their characters and of their lives. Even in the middle of the nineteenth century you will find the same spirit of remoteness and divergence from the lives of the poor. For instance, there is a passage in one of the prefaces of Thackeray—I forget at the moment to which work it is—in which he excuses himself from not dealing more harshly with some of his characters. He had an idea, he said, of making one of his characters do some desperate deed that would bring him to penal servitude, but could not boast any acquaintance with convicts and therefore he did not propose to describe either their character or their lives. I venture to say that was not an observation worthy of that serene and judicial outlook which literature should always choose. For literature, as De Quincey once said, should have an equal and impartial view of all society, of all men and women, and should look and analyse with the same care the minds and the souls and the careers of the guilty as well as of the free. Robert Buchanan was one of the men who symbolised the growth of the human spirit in literature. If he had done nothing more than re-preach the gospel of Dickens in that respect his life and his works would not have been in vain. After some hours of this wandering about London Buchanan settled down in 66, Stamford Street, Blackfriars. I shall not attempt to describe for a Southend audience 66, Stamford Street, Blackfriars. Southend would probably not quite understand what kind of squalor and hopelessness such a street possesses. If a gentleman who is at the end of the room, and who is now the greatest master living in describing the life and character of London—I mean Mr. George R. Sims—were on this platform, he could give a description of Stamford Street, Blackfriars, which would present it to your imaginations in a way I cannot attempt. Suffice it to say that in a top room in this unlovely street and at a rental of 7s. a week, Buchanan started his career in London. One of his fellow lodgers was a drunken compositor, and he told afterwards how one morning the compositor came into his room with an open razor and asked him to cut the button off his shirt that was choking him. Buchanan complied with the request and the compositor committed suicide immediately afterwards in the adjoining room. Here again Buchanan was, unconsciously perhaps, going to school in the great university of life. He was among the depths of human despair end human misery, to which afterwards he gave such noble and such eloquent utterance. His efforts to obtain employment. like those of most young literary provincials who come to London, were attended with many disappointments. He was able to get hack work from the “Athenæum,” and to write in some of the cheaper newspapers and periodicals, and in that way he was able to eke out a small but very uncertain livelihood. Mr. O’Connor went on to speak of Buchanan’s connection with Gibbon and Miss Braddon and said after a while his parents followed him to London. The indomitable father had taken up at this time the writing of those penny dreadfuls for cheap story papers, and between them all they managed to sparsely furnish a little house in Kentish Town and there they all lived together some time.

It was at this period that Buchanan had some experience as a playwright. When he was only fourteen he wrote a pantomime for a Glasgow manager. His fee was not very large, I believe, but the manager managed to make some money. It gave him a taste for the stage and revealed to him some of the latent talents.

HIS MARRIAGE.

In 1861 took place what in many respects was the most momentous event in Buchanan’s life, namely his marriage. I have ventured an attempt at a description of the wife of Robert Buchanan, but I saw her when she was already somewhat of an invalid. I never had an opportunity of seeing her in the first flush of her youth, her health, and her beauty, but even when I saw her she was one of the most beautiful and certainly one of the most winning creatures I have ever beheld. Her character will always stand forth as one of the most beautiful of a woman and a wife that home life has ever presented. At this moment the world is engaged in discussing the conjugal relations of another great Scotchman and his wife. I mean Thomas Carlyle and Jane Welsh Carlyle. It is instructive to make a contrast between Mrs. Carlyle and Mrs. Buchanan. Mrs. Carlyle had many great and noble qualities. She endured much suffering in her life. But not the greatest friend and admirer of Mrs. Carlyle can say she was always very reticent with regard to her sufferings and that she bore the ordinary worry of life with exemplary patience. A quarrel attained to something like a tragedy, with all the grief, fatefulness, and horror combined in it. Mrs. Buchanan was a woman of a very different mood. Her tragedy was in many respects a more real tragedy than that of Mrs. Carlyle. Mrs. Carlyle suffered much from nerves and died at sixty from heart disease. But for many years of her life Mrs. Buchanan was a martyr to ill-health. Towards the end she was attacked by the most appalling of all diseases—cancer, and it was of cancer she finally died. She was a sufferer during most of her life, but she was mainly a silent sufferer and her aim was to hide from those she held dear the real state of her own health and her own sufferings. Next to his relations to his mother, the most beautiful thing in the life of Robert Buchanan is his treatment of his wife. Ladies and gentlemen, I don’t think that any literary man is much entitled to the admiration of mankind whose relations to the wife do not bear the inspection of the tenderest and humanest spirit. (Applause.) After his marriage, Buchanan of course worked harder than ever, and now I come to speak of what, after all, is one of the saddest things about the life of Buchanan. He never learnt the “art” of compound addition. He was

CHRONICALLY, HOPELESSLY, ETERNALLY, HARD UP.

Whatever money he made disappeared suddenly and quickly, and the result of it was he was in that painful position which one often sees in life and especially in the profession to which he belonged—he was at once a drudge and a spendthrift. He worked hard, he got the money, and when the money was got it very soon disappeared and the hard work had to begin again. The result of it is that there is always about the life of Robert Buchanan a sense of failure and ineffectiveness. There is always a feeling that his was a genius which never reached the height and never earned the recognition to which it was entitled. He was too much of a drudge, too worried, to be ever at his very best. He wrote too much to be ever properly considered, and in addition to these disqualifications for the greater and higher fame to which he ought to have reached he had something of the love of a fight which betrayed him into many quarrels and into many expressions and articles which he himself afterwards deplored. The curious thing is that Robert Buchanan was himself never an ill-natured man. On the contrary, he was one of the most kindly and good-natured of men, but somehow or other kindly and good-natured men seem to be stirred up to some degree of violence and vehemence when they get their pens in their hands. I dare say some of you would be very surprised if you could see in the flesh some of the authors of those violent diatribes which anger, shock, and amuse you in the newspapers.

WARLIKE ONLY ON PAPER.

You generally find that a man who is calling for blood and war and all that sort of thing is a chronic invalid—(laughter)—who has to fashion his diet on a toast and water regime. You generally find that a man who calls upon his countrymen to rise up in their wrath trembles before the slight form of a tiny and delicate wife. (Laughter.) In the same way you will find, as in the case of Buchanan, that the man who writes most violent and sometimes most vehement articles is himself of a very kindly nature. You all know some of the quarrels into which Buchanan fell. Some of them are already historical—some of them are, I am glad to say, almost forgotten. The most bitter of these quarrels was the quarrel he had with what he christened, I think he was the first to christen it—the fleshly school—the school represented in poetry by Swinburne and Rossetti. Many of the attacks he made on these most distinguished and illustrious poets were ill-founded, unfair and unnecessarily rancourous. The result of the attack was to bring down on Buchanan a storm of ridicule and abuse under which he might well have reeled and it pursued him for a great many years afterwards. And if you want to find one of the reasons why the recognition of Buchanan has been so slow and so grudging you will find it in the fact that, as in the case of the article on the fleshly school, he was always tilting at other men and tilting without regard to consequences. This is a spirit which one must not always entirely condemn. I am myself rather opposed to vehemence in any literary discussion; at the same time the world is so given up to conventions and shams that it is absolutely necessary that you should have some independent, fearless, and perhaps rancourous and crushing attack to bring it back to truer ideals of literature. In literature there are always a number of false reputations. There are those whose works sell by the hundreds of thousands who really are

NOT FIT TO WRITE FOR KITCHEN-MAIDS.

(Applause.) Sometimes Buchanan was wrong, perhaps usually he was wrong, but very frequently he was right. And in these days when literary criticism is so often conventional and so often ready to accept the ideas of the mob, the literary mob, it is well that some such voice as his should be raised in protest and in protection of true literary value.

From poetry, to which he ought always to have stuck, Buchanan turned to novel writing, and novel after novel came from his fertile and apparently inexhaustible pen. He was past forty years when he became really a professional playwright. When he took to playwriting his fertility and his versatility were the same as when he wrote poetry and when he wrote novels. His first great success was the play of “Sophia,” a play that ran for a considerable number of nights and that brought him in a large sum of money. He had the good luck soon after he started his dramatic career to be associated in collaborations with the gentleman to whom I have already alluded, and whose presence we welcome here to-day, Mr. G. R. Sims. For some years he and Mr. Sims in collaboration produced play after play for the Adelphi Theatre.

BUCHANAN AS THEATRICAL MANAGER.

Again the speculative spirit which he inherited from his father came in to interfere with his advance. No sooner had he made a large sum from the play than he took into his head the mad idea that he was a good business man and a good theatrical manager. He took theatre after theatre and produced play after play. I need scarcely say that these things, while they were all artistic triumphs, always ended in financial disaster. In the end he was not only not one penny piece the better for all his immense earnings, but he was broken in fortune and to a certain extent broken in health and in hope as well. The final blow came when he took the Opera Comique and produced a play there with insufficient capital. He was served with a notice in bankruptcy and he had to go through all the distress of financial embarrassment.

AT SOUTHEND.

And then there were family troubles, among them the ill-health of his wife. As her last hours were approaching she longed for a sight of the sea and she came down to Southend in order to get it. Her history as well as her grief are very intimately associated with this town. I thought to-day as I ascended the somewhat steep steps of Fenchurch Street Station of a pathetic incident which Miss Jay relates in her biography. While her husband went to take the tickets at the railway station, she rushed to the stairs. She tried to run up the stairs rather rapidly in order to prove to him and to herself perhaps, that she was much better than he thought she was. A stranger met her on the stairs and with thoughtfulness and tenderness offered to lead her up and to give her his arm as support. She pettishly and almost angrily resented this offer of assistance and said to her sister “Why did he do that? I am very well able to do it myself.”

The reviving airs of this town enabled her to walk about a little, but soon she became unable to walk and had to be taken out in a bath chair. Having touchingly described the death of Buchanan’s wife and mother, Mr. O’Connor told how the great poet, after a serious illness, took to bicycle riding. This, however, was only a brief flush, and one day after a ride he said to Miss Jay “I should like to have a good run down Regent Street.” They were the last words he spoke, and he died on June 10th, 1901, in his sixtieth year. Mr. O’Connor concluded: Such, ladies and gentlemen, was the life of Robert Buchanan. It is, as you see, a life that was not altogether a life of success. In fact, in many respects it was a life of failure, but it had many things to commend it. I think one may claim to make some distinction between different forms of extravagance. There is the extravagant man who spends his money upon himself and neglects the calls of duty to others. That was not the extravagance of Robert Buchanan. He was a good husband, a good son, and a good friend. His want of money was largely due to the fact that his purse was open to everybody—even the most thriftless, the most idle, the most worthless of his comrades in arms were almost sure to find a friend in him, and he gave not small sums but large sums to those who were in distress. The story I have had to tell you of these three beings who are now silent is closed. It is a sad story, the story of a woman who died of cancer at the age of 36, of an old woman who lay down to rest wearied and tired of the struggle, and of a man who died at what we regard in these days as a premature age. I hope I have done something to make you realise all the sorrow, all the affection and all the tragedy that lies behind these three names.

The Mayor said he was sure they felt it a very great honour to have in their midst and to be able to retain in their midst the memory of a man such as Robert Buchanan, and he was sure they would all in the future respect, honour, and keep sacred that memory.

Alderman Francis, as treasurer of the Memorial Fund, announced that the subscription list was not yet closed. It was now his pleasing duty to propose a very hearty vote of thanks to Mr. O’Connor for coming there, unveiling the memorial, and giving them a sketch of the late poet’s life to which they had listened with so much interest. He saw in the paper that Mr. O’Connor was very anxious to write something which would live after him. He ventured to say that Mr. O’Connor’s work would live after him. He knew that this visit of Mr. O’Connor’s would lead to far greater interest being taken in the works of Buchanan, and he ventured to hope that Mr. O’Connor’s visit would lead him to take a little more interest in Southend and visit them again before long. He understood the seconder would be Mr. John Burrows, the editor of the “Southend Standard.”

Mr. J. W. Burrows said he had very great pleasure in seconding the vote of thanks so ably proposed by Mr. Alderman Francis. If he would apologise, as one so young and inexperienced, for saying anything on that occasion he would say that as a journalist in a very humble sphere he had an honest and ardent admiration of the work which Mr. O’Connor was doing in this country in the way of providing cheap and wholesome newspapers and also during the last few years in the way of social and literary effort. It seemed to him the working people of this country owed a very great debt to Mr. O’Connor for what he had done in this direction. There was another thing which he thought they ought all to recognise now that Mr. O’Connor was with them and that was the work which he had done recently in the House of Commons in forwarding a measure of land reform in Ireland, which they all hoped and believed would encourage and assist that country. He referred to this, because many of them who had read Miss Jay’s work would know that for some years in remote Connaught Mr. and Mrs. Buchanan spent very many happy days and that there, he had no doubt, the imagination which stood Buchanan in such good stead was aided and encouraged by the Celtic fire which they all knew came from Ireland. A witty and distinguished baronet had described their watering place as the national Riviera. Buchanan said that he knew of no lovelier place when Spring became a certainty than Southend. They had got into sweltering July, but he trusted that although Spring had passed Mr. O’Connor would think none the less of their watering place, but more highly of it. Southend had been proud to welcome Mr. O’Connor, and they trusted that Mr. O’Connor was gratified with Southend’s greeting.

Mr. Reveirs-Hopkins, in supporting the vote, said that he spoke for his co-secretaries, Mr. Coulson Kernahan and Mr. Varney, who were both quite unable to be there. He was asked by Miss Jay to express to Mr. O’Connor his personal gratitude for the great honour and kindness he had done to her personally by coming there that day. This was not only a public function, but an honour to a dead friend. Nobody could have done it more sympathetically and beautifully than Mr. O’Connor had. From this day they would not only look upon Mr. O’Connor as a great speaker, a great writer, and a great Member of Parliament, but as something more than that, a most sympathetic, loving friend.

The vote was enthusiastically carried, and in replying

Mr. O’Connor said he was extremely obliged for the kind remarks that had been made. He really felt it was impossible for him to refuse to come down and do honour to a great man of letters, and, as the Secretary had just said, a man who was a personal friend of his. When he saw the face of Buchanan in that wonderfully fine bust, when he saw the figure of Miss Jay close by, the whole meaning and reality of the tragedy of those three lives came back to him and he was deeply touched and moved. He was sorry to say that his visit to Southend was a brief one.

AFTER 33 YEARS.

He had been trying to get to Southend for 33 years, but this was the first time he had succeeded in doing so. It was 33 years since he started from his lodgings by the Strand—not quite so bad as that lodging poor Buchanan had in Stamford Street, but not very much better—to take a trip to Southend. But some malign destiny seemed to hang over him. When he got to Fenchurch Street—when the train service was, he dared say, not so good as now—he found that the train by which he had determined to come had gone. The result of it was he had to postpone his visit for 33 years. (Laughter.) He had not yet seen much of their town, though he had heard much of it. But what he had seen had pleased him very greatly and he hoped at no distant date he would have the opportunity of making a longer stay and a closer acquaintance.

On the proposition of the Vicar a hearty vote of thanks was passed to the Mayor for presiding.

Subsequently the Mayor drove Mr. O’Connor round the town and Mrs. Reveirs-Hopkins provided tea for the guests.

___

The Stage (30 July, 1903 - p.10)

MEMORIAL TO ROBERT BUCHANAN.

On Saturday a memorial to the late Robert Buchanan, which had been erected in St. John’s Churchyard, Southend, was unveiled. Mr. T. P. O’Connor, M.P., and Miss Harriett Jay, the deceased poet’s sister-in-law, approached the monument together, and as Miss Jay removed the covering Mr. O’Connor declared the bust unveiled, and handed it over to the custody of the vicar and churchwardens. The memorial, the cost of which has been defrayed by public subscription, is of plain sunk Bath stone, semi-circular in form, in front of which is a pedestal surmounted by a bronze bust of the late Mr. Buchanan. York stone forms the base, upon which is the inscription, and on either side are planted yew trees. Mr. Buchanan passed his last days at Southend. Mr. Buchanan’s body is interred with those of his wife and mother in the churchyard where the bust was unveiled.

Among those present at the unveiling were Major Sir Carne Rasch, M.P., Col. E. Tufnell, M.P., Mr. George R. Sims, Mr. Val Brown, L.C.C., the Rev. Conrad Noel, the Rev. W. Walsh. Mr. O’Connor’s address at the Parochial Hall was most warming and sympathetic. He said that the hardships of Buchanan’s later years were brought about not so much by his inability to get money as by his generosity to others and his want of business aptitude. The best feature of his life was his wholehearted devotion to his invalid wife and to his mother. The Mayor, Councillor A. Martin, expressed his sense of the honour done to Southend by the visit of Mr. O’Connor, to whom Alderman J. Francis proposed a vote of thanks, seconded by Mr. John Burrows. The monument was designed by Mr. Morley Horder, and executed by Mr. W. Darke of Southend.

___

Essex County Chronicle (31 July, 1903 - p.2)

MEMORIAL TO ROBERT BUCHANAN AT SOUTHEND.

On Saturday, in the presence of a large assembly, a memorial to the late Robert Buchanan, the poet, which had been erected in St. John’s Churchyard, Southend, was unveiled. Mr. T. P. O’Connor, M.P., and Miss Harriet Jay, the deceased poet’s sister-in-law, approached the monument together, and as Miss Jay removed the covering Mr. O’Connor declared the bust unveiled, and handed it over to the custody of the vicar and churchwardens. He afterwards gave an address in the Parochial Hall bearing upon the life of Buchanan. The memorial, the cost of which has been defrayed by public subscription, is of plain sunk Bath stone, semi-circular in form, in front of which is a pedestal surmounted by a bronze bust of the late Mr. Buchanan. York stone forms the base, upon which is the inscription, and on either side are planted yew trees. Mr. Buchanan passed his last days at Southend. His sister-in-law, Miss Harriet Jay, collaborated with him in the production of the plays—“Alone in London,” “Fascination,” “The Strange Adventures of Miss Brown,” and “The Romance of a Shop Walker.” Buchanan was a fertile as well as a most able writer. In 1872 he created an enormous sensation by an attack on what he called the “Fleshly School of Poetry.”

Mr. Buchanan’s body is interred with those of his wife and mother in the churchyard where the bust was unveiled.

Mr. O’Connor arrived at Southend early on Saturday afternoon and lunched with the Mayor and Mayoress, Councillor and Mrs. A. Martin. Among those present at the unveiling were Major Sir Carne Rasch, M.P., Col. E. Tufnell, M.P., and Mrs. Tufnell, Mr. and Mrs. E. H. Draper, Mr. W. Lloyd Wise, Mr. Elliott Fletcher, Mr. Geo. R. Sims, Mr. Wm. Hellas, Mr. Françillon, Mr. Macdermott, Mr. Doherty, Mr. Val Brown, L.C.C., the Rev. Conrad Noel, the Rev. W. Walsh, Mr. E. Turner, Mr. Mcguire and Miss Harriett Jay.

___

The Referee (2 August, 1903 - p.11)

(From the ‘Mustard and Cress’ column by ‘Dagonet’ (George R. Sims):

Last week I went to Southend-on-Sea to assist at the unveiling of

The Memorial to Robert Buchanan.

Mr. T. P. O’Connor, who, with Miss Harriett Jay, performed the ceremony, delivered a sympathetic address which dealt largely with the tragic side of Buchanan’s life story. After the address I slipped away, for I wanted to get back to London under favourable circumstances. I have travelled from Southend to London late on Saturday night twice. That is sufficient for any many who likes to choose his own company and his own musical entertainment.

_____

The only picture I’ve found of the original monument is the drawing from Harriett Jay’s biography of Buchanan, which was published in February, 1903 (several months before the monument was erected). Jay also mentions in Chapter 23, referring to The City of Dream, that “a verse from which is now to be found upon his tomb.”

|