ROBERT WILLIAMS BUCHANAN (1841 - 1901)

|

ROBERT WILLIAMS BUCHANAN (1841 - 1901) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

PUBLISHED LETTERS

Although there is no published ‘Collected Letters of Robert Buchanan’, I occasionally come across letters which have been included in the collections of other writers, or the memoirs of his contemporaries. I have placed these here. (I also must thank Beverley Rilett for the Whitman and Eliot entries.) It should also be noted that another major source of ‘published letters’ is Harriett Jay’s 1903 biography of Robert Buchanan, which includes several complete letters as well as extracts from others, and is available on this site. Two letters from the biography (one to Roden Noel from August 1868 and one to W. E. H. Lecky from May 1888) were also reprinted in Letters of Literary Men (Vol. 2 The Nineteenth Century) edited by Frank Arthur Mumby (London: George Routledge & Sons Ltd. 1906). _____

From Study and Stimulants; or, the Use of Intoxicants and Narcotics in Relation to Intellectual Life, as Illustrated by Personal Communications on the Subject, from Men or Letters and of Science edited by A. Arthur Reade (Philadelphia: J. B. Lippincott and Co., Manchester: Abel Heywood and Son, 1883 - p.26)

MR. ROBERT BUCHANAN. I am myself no authority on the subject concerning which you write. I drink myself, but not during the hours of work; and I smoke—pretty habitually. My own experience and belief is, that both alcohol and tobacco, like most blessings, can be turned into curses by habitual self-indulgence. Physiologically speaking, I believe them both to be invaluable to humankind. The cases of dire disease generated by total abstinence from liquor are even more terrible than those caused by excess. With regard to tobacco, I have a notion that it is only dangerous where the vital organism, and particularly the nervous system, is badly nourished. ROBERT BUCHANAN. _____

From Albert Chevalier, a Record by Himself by Albert Chevalier (Biographical and other Chapters by Brian Daly) (London: John Macqueen, 1895 - pp. 149-150) Chevalier first sang “My Old Dutch” at the Alhambra, in Brighton, and the late David James having heard it, suggested that the song would bear a fourth verse, which was afterwards written. “Jan. 17th, 1893. “DEAR MR. CHEVALIER, “May I congratulate you on your new song, “The Dear Old Dutch,” which I heard you sing on Saturday evening. It is infinitely sweet and beautiful—a breath of pure human tenderness which ennobles the atmosphere of even a Music Hall. The feeling and the expression are alike perfect, and taken with the rest of the work you are doing, a precious boon to the public. I think your songs unique in ballad literature, and your own art in rendering them something to admire and envy. I am glad to see that the public responds so enthusiastically to such admirable work. You are doing more good than perhaps you realise, and you deserve all the success that can possibly come to you. _____

I have no more information about the following letter, mentioned in a news item of 1896, no idea who the recipient was, or whether it still exists - I have found no letter with that date in the list of any archive or collection. But, given the fact that the brief extract reveals Buchanan’s attitude to Monckton Milnes (Lord Houghton) and his Preface to David Gray’s The Luggie, and other poems (published May, 1862), I thought it worth noting here.

The Sheffield Evening Telegraph and Star (20 June, 1896 - p.2) BUCHANAN ON GREY’S DEATH. An autograph letter of Robert Buchanan’s, dated February 6, 1862, is advertised for sale in a catalogue. It contains the following reference to David Grey:—“You have heard of dear Grey’s death. It is a mockery for Milnes, whose silent coldness made the poor boy’s last days miserable, to write a preface to the poems. It is the old story—pæans are too late now.” _____

From Hall Caine, the Man and the Novelist by Charles Frederick Kenyon (London: Greening & Co., Ltd., 1901 - pp. 79-80)

Before I leave Rossetti and turn to the novels of the subject of this monograph, I should like to give a letter of the late Mr Robert Buchanan, addressed by him to Mr Caine after reading the latter’s obituary notice of his friend in the Academy. To all who know anything of the life of Rossetti, it will prove of exceptional interest, for it bears directly upon one of the causes of his premature death, and throws fresh light on one of the most widely-discussed episodes of nineteenth-century literature. “30 BOULEVARD STE BEUVE, “DEAR SIR,—I have read with deep interest your memorial of poor Rossetti, and been particularly moved by your passing allusion to myself. I don’t know if your intention was to heap ‘coals of fire’ on my head, but whether or not you have succeeded. I have often regretted my old criticism on your friend, not so much because it was stupid, but because, after all, I doubt one poet’s right to criticise another. For the rest, I have long been of opinion that Rossetti was a great spirit; and in that belief I inscribed to him my ‘God and the Man.’ ___

In Hall Caine’s autobiography, My Story (London: William Heinemann, 1908), this letter is ‘dramatised’ as Caine’s first meeting with Buchanan. He then writes: “A few days afterwards he wrote a long letter, which was intended to explain the motive which had led him to make his unjust attack: This letter was also included (as a footnote to pp. 71-72) by Hall Caine in his Recollections of Dante Gabriel Rossetti (London: Elliot Stock, 1882). _____

From Among My Autographs by George R. Sims (London: Chatto & Windus, 1904.) [Note: For the context in which these letters, please refer to in the Biography section of the site. The second letter is Buchanan’s first approach regarding collaboration with Sims on an Adelphi drama and so probably dates from 1890. The third letter (sent from the country residence of the Marquess of Ailesbury) was probably written during the period of their collaboration which lasted from 1890 to 1893.]

5 Larkhall Rise, Dear Sir, ___

Dear Mr. Sims, ___

Savernake Forest, Dear George, _____

From With Walt Whitman in Camden Vol. 1 (March 28-July 14, 1888) by Horace Traubel (Boston: Small, Maynard & Company, 1906). [Note: The complete With Walt Whitman in Camden is available at The Walt Whitman Archive. As well as this letter of Buchanan’s, Vol. 1 also includes a copy of a letter from Whitman to Buchanan which I thought worth including here. The second volume of With Walt Whitman in Camden includes two more letters from Whitman to Buchanan. Buchanan’s original letter to the Daily News of 13th March, 1876, drawing attention to the economic plight of Whitman, is available in the Letters to the Press section.]

(pp. 1-3) Wednesday, March 28, 1888. . . . W. handed me a leaf from The Christian Union containing an article by Munger on Personal Purity, in which this is said: “Do not suffer yourself to be caught by the Walt Whitman fallacy that all nature and all processes of nature are sacred and may therefore be talked about. Walt Whitman is not a true poet in this respect, or he would have scanned nature more accurately. Nature is silent and shy where he is loud and bold.” “Now,” W. quietly remarked, “Munger is all right, but he is also all wrong. If Munger had written Leaves of Grass that's what nature would have written through Munger. But nature was writing through Walt Whitman. And that is where nature got herself into trouble.” And after a quiet little laugh he pushed his forefinger among some papers on the table and pulled out a black-ribbed envelope which he reached to me: “Read this. You will see by it how that point staggers my friends as well as my enemies. We have got in the habit of thinking Buchanan is not afraid of anything—is a sort of medieval knight militant going heedlessly about doing good. But Buchanan, who is not afraid of anything, is afraid of Children of Adam.” 16 UP. GLOUCESTER PLACE, DORSET SQUARE, Dear Walt Whitman: Pray forgive my long silence. I have been deep in troubles of my own. All the books have arrived and been safely transmitted. Many thanks. W. watched me as I read the letter and when he saw I was through resumed: “Children of Adam stumps the worst and the best: I have even tried hard to see if it might not as I grow older or experience new moods stump me: I have even almost deliberately tried to retreat. But it would not do. When I tried to take those pieces out of the scheme the whole scheme came down about my ears. I turned Buchanan’s letter up today in a heap of nothings and somethings. I guess Buchanan and Munger would not agree about lots of the subsidiary things but here the preacher and the radical come together: though as for that there is a difference between them even in this thing: for while Munger talks of the ‘fallacy’ as though it was fundamental to Buchanan I am only guilty of a lack of taste. Well—there are the pieces, to sink or swim with the book: and here is Walt Whitman to sink or swim likewise.” ___

Friday, June 22, 1888. . . . Reminded of an old affair by the draft of a letter W. to Robert Buchanan (1876) which we turned up on the table while looking for something else, W. said to me: “There was a great rattling of dry bones over there and here that time about my poverty—whether I was starving to death or wasn’t—whether the Americans deserted me or didn’t desert me: Conway particularly seemed to take it particularly hard that America should be supposed to have neglected me. It was during that period that I wrote Buchanan several letters—this is one of them—in which I tried to calm the waters even while frankly confessing my financial disabilities. But you will see for yourself what I mean: you have other documents relating to the same incident. I think a little blood was spilled but no one was really hurt. If a man sells goods—well, selling them seems all right: but if he sells poems, selling is degrading, wrong. When I confessed to those Englishmen that I had written and written and no one—or almost no one—here wanted what I wrote—said so honestly to the few on the other side who did care a little for me—accepted their help here and there, when I needed it (I often gave help where help was needed) I was regarded as a beggar, charged with misrepresenting America, and so on, and so on. What I said was true, true, every word of it. I didn’t blame America for not wanting me—I only remarked it. Maybe it was America that was right and England that was wrong: I do not know. But you will read the Buchanan letter—now I am tired: let’s say good-night.” He took my hand. “You are sensitive—I know you well, well, so you must believe me when I say that my good-night is not a dismissal—it is only good-night! A good-night and a God bless you!” He kissed me. I did not read the letter until I got home. W. certainly was very clear tonight. Speech very slow, hard, but straight—noway confused. Baker says he is rather mixed up when he first comes out of his sleep in the morning but that he seems afterwards rational enough however physically depressed. “Your two letters including the cheque for £25 reached me, for which accept deepest thanks. I have already written you my approval of your three communications in L. D. News and saying that in my opinion (and now with fullest deliberation reaffirming it) all the points assumed as facts on which your letter of March 13 is grounded are substantially true and most of them are true to the minutest particular as far as could be stated in a one column letter. A marked out passage in the letter was this: “There is doubtless a point of view from which Mr. Conway’s statement of April 4th might hold technically—but essentially, and under the circumstances—” There was no more. ___

From With Walt Whitman in Camden Vol. 2 (July 16, 1888 - October 31, 1888) by Horace Traubel (New York: Mitchell Kennerley, 1915).

(pp. 326-327) Saturday, September 15th, 1888. . . . W. handed me some drafts of letters pinned together: “You may put them away or throw them away just as you think best. They will give you a little biographical data, maybe—and that would be some excuse for keeping them. Before you came around I used to burn most of such stuff up: you are responsible for the idea that there is a reason for preserving it.” The letters were to Freiligrath, Buchanan (two), Carlyle and John Morley. I will put them here in the order in which they were pinned together. On the back of the second Buchanan letter W. wrote: “Sent B the N Y letter of July 4 '78 (to Olean, Scotland).” On the back of the Carlyle letter he had written: “To Carlyle with Dem Vistas & Am Inst. poem.” On the reverse of the Morley letter was this: “letter to Mr. Morley reach'd London probably New Year’s day.” . . . Sept. 4 ’76. R. BUCHANAN.

431 STEVENS ST COR WEST ROBERT BUCHANAN— My dear friend—I merely want to say that I have read your letter in the London Daily News—all your three letters—and that I deeply appreciate them, and do not hesitate to accept and respond to them in the same spirit in which they were surely impelled and written. _____

From Recollections by David Christie Murray (London: John Long, 1908 - pp.306-309) [Note: Although David Christie Murray (elder brother of Buchanan’s friend and collaborator, Henry Murray) does not mention Buchanan in his autobiographical works, he does include two letters from Buchanan in Recollections, preceded by the letter from Joseph Hocking. In March, 1896 there was a heated exchange of letters between Christie Murray and Buchanan in The Era concerning plagiarism charges.]

Copy of Letter to David Christie Murray, 148 Todmorden Road, MY DEAR SIR, — Will you kindly excuse the liberty I take in writing? I have just bought and read your new book My Contemporaries in Fiction, and feel that I must thank you. The task you assumed was, I think, necessary, and your estimate of the various writers just, and on the whole generous. I know my opinion is of little value, but I have long felt that several of our modern novelists were appraised miles beyond their merits, and I have often wished that some man of position, one who could speak candidly without fear of being accused of being envious, would give to the world a fair and fearless criticism of the works of novelists about whom some so-called critics rave. Thousands will be glad that you have done this, and I hope your book will have the success it deserves. ___

Copy of Letter to David Christie Murray, DEAR MURRAY,—I am getting so weary of controversy that I must decline to take part, directly or indirectly, in any more. Possibly, in the heat of annoyance, I may have said harsh things about Mr Scott, but if so, I have forgotten them, and I think all harsh things are better forgotten. I am sorry, therefore, to hear that you are on the war-path, and wish I could persuade you to turn back to the paths of peace. You are too valuable to be wasted in this sort of warfare. I daresay you will smile at such advice from me, of all men, but believe me, I speak from sad experience. ___

Copy of Letter to David Christie Murray, “Merkland,” 25 Maresfield Gardens, DEAR CHRISTIE MURRAY,—I thank you for your kind breath of encouragement, and am very glad that my Outcast contains anything to awaken a response in so fine a nature as your own. It was very good of you to think of writing to me on the subject at all. _____

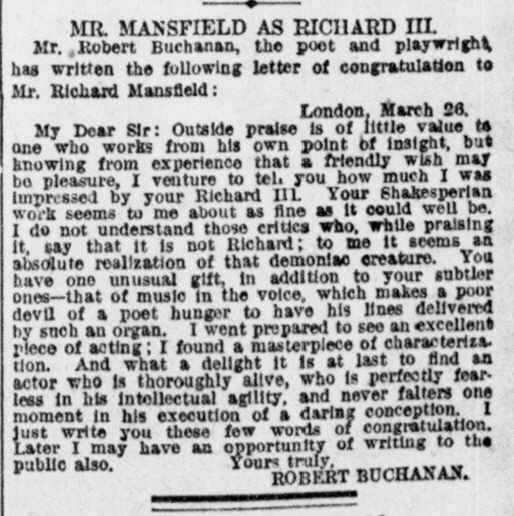

From Life and Art of Richard Mansfield: with selections from his letters, Volume 1 by William Winter (New York: Moffat, Yard and Company, 1910 - pp. 108-110) Among the many personal tributes that Mansfield received, on the occasion of his performance of Richard the Third, two letters from the poet Robert Buchanan gave him much gratification. The author of such poems as “Two Sons,” “The Ballad of Judas Iscariot,” and “The Vision of the Man Accurst” was a person whose praise was worth having. He is dead now, and in his death a fine genius perished. Buchanan’s first letter, a copy of which was sent to me by Mansfield, was first published in “The New York Tribune,” April 9, 1889. London, March 26, 1889.

“Leyland,” Arkwright Road, |

|

|

[From The New-York Daily Tribune (April 9, 1889 - p.6).] [Note: The address of Buchanan’s second letter to Mansfield is interesting. “Leyland,” Arkwright Road, Hampstead was the residence of Mona Caird. According to the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography: “Caird [née Alison], (Alice) Mona (1854–1932), writer, was born on 24 May 1854 at 34 Pier Street, Ryde, Isle of Wight, to John Alison, an inventor from Midlothian, and Matilda Ann Jane, née Hector. As a child she wrote plays and stories. On 19 December 1877 she married James Alexander Caird (d. 1921), son of Sir James Caird, at Christ Church, Paddington, London. The couple resided at Leyland, Arkwright Road, Hampstead, London, for the remainder of their forty-four-year marriage. Their only child, Alison James Caird, was born at Leyland on 22 March 1884.”] _____

From Sixty-Eight Years on the Stage by Mrs. Charles Calvert (London: Mills & Boon, 1911 - pp.131-133) [Note: Buchanan lived at Rossport Lodge between 1873 and 1877.]

During the last three or four years that we lived in Manchester I was engaged by the committee of the Royal British Institution to give readings from the poets, in their lecture room, on Wednesday afternoons during the winter session. As there were three of these readings in the year, and each one embraced some nine or ten items, it follows that they required a considerable amount of research (for I very seldom repeated anything), and I had to scamper through dozens of volumes to obtain the requisite material. Rossport Lodge, DEAR MADAM, A friend writes to tell me that you have been publicly reading some of my poems, and that you have actually read, successfully too, the “Ballad of Judas Iscariot,”—which last piece of news is to me so astonishing that I am tempted to ask particulars at the fountain head. That you should have faced an audience with such a poem, strikes me as singularly original and courageous, but that you should have moved that audience with it, in defiance of popular prejudice, is a proof of extraordinary genius. Do tell me all about it, if I am not rude in asking the favour. I fervently believe that one who could do so much with “Judas Iscariot” could read even “The Vision of the Man Accurst” with overwhelming effect. Do you know the last-named poem? I was compelled to reply that, intensely as I admired the poem, I was afraid to include it in my programme. Many of the lines in the “Vision of the Man Accurst” were supposed to be spoken by the First Person of the Trinity, and, as my audiences usually included schools, it might be regarded by the teachers as savouring of profanity. _____

From My Life: Sixty Years’ Recollections of Bohemian London by George R. Sims (London: Eveleigh Nash Company Ltd., 1917.) [Note: Sims dates this letter as shortly after the annual banquet of the Royal Academy of Arts, at which Mr. W. E. H. Lecky praised Buchanan’s A City of Dream. However, this took place on 5th May, 1888 and their first collaboration for the Adelphi, The English Rose, did not appear till September 1890, which would suggest this letter is later. The passage in which this letter appears is available in the Biography section of the site.]

Dear Sims, _____

From ‘Robert Buchanan, F. J. Furnivall, and the Browning Society: A Letter’ by Jay Jernigan (Studies in Browning and His Circle - Vol. 3, No. 1, Spring, 1975.) [Note: The essay is available in the Fleshly School section of the site.] 38 Queen Anne St Dear Mr. Furnivall, I have to thank you heartily for the Browning circular; and I take the opportunity to send you a copy of my new prose poem, ‘God & the Man.’ I know that you will apprehend its spirit & its purport, & I trust that it may secure for me ‘one more friend.’ Like Browning himself, I have suffered for years from the persecution of a literary Inquisition; and as it is such men as you that scatter light & fight on the side of minorities, I would gladly secure your sympathy in more or less measure. Yours cordially, ___

2 Devereux Terrace Dear Mr. Furnivall, I thought to be in Queen Anne St temporarily this week, but on Monday night my beloved wife died here. While this great darkness is upon me, I cannot respond to your kindness as I could wish; but I look forward to seeing you some day soon. With kind regards Yours faithfully _____

From The George Eliot Letters. Vol. 9. 1871-1881. Ed. Gordon Sherman Haight (Yale University Press. 1978.)

9th December, 1878 Private Dear Mrs. Lewes, I wrote the enclosed in the Examiner, and it fairly expresses my feeling on the subject. I wish I could send you any comfort; I cannot—only my warmest prayers. Most truly yours,

[Note: _____

From Oscar Wilde Revalued: An Essay on New Materials and Methods of Research by Ian Small (ELT Press, 1993) (p.81.)

ALS Robert [Williams] Buchanan to Wilde MS Wilde, O. Recip. Merkland My dear Oscar Wilde, I ought to have thanked you thus for your present of Dorian Gray, but I was hoping to return the compliment by sending you a work of my own: this I shall do in a very few days. You are quite right as to our divergence, which is temperamental. I cannot accept yours as a serious criticism of life. You seem to me like a holiday maker throwing pebbles into the sea, or viewing the great ocean from under the awning of a bathing machine. I quite see, however, that this is only your “fun,” & that your very indolence of gaiety is paradoxical, like your utterances. If I judged you by what you deny in print, I should fear that [you] were somewhat heartless. Having seen & spoken with you, I conceive that you are just as poor & self-tormenting a creature as any of the rest of us, and that you are simply joking at your own expense. With thanks & all kind wishes Oscar Wilde Esq. ___

This letter is described on pages 70-71 as follows: ‘The kind of insights which such snippets provide is better illustrated by another unpublished letter in the HRHRC collection—from Robert Buchanan to Wilde: My dear Oscar Wilde, I ought to have thanked you thus for your present of Dorian Gray, but I was hoping to return the compliment by sending you a work of my own: this I shall do in a very few days. You are quite right as to our divergence, which is temperamental. I cannot accept yours as a serious criticism of life. You seem to me like a holiday maker throwing pebbles into the sea, or viewing the great ocean from under the awning of a bathing machine. I quite see, however, that this is only your “fun,” & that your very indolence of gaiety is paradoxical, like your utterances. Buchanan was a controversial figure who had made a reputation as a virulent critic of most of the values Wilde stood for. To discover Wilde initiating a friendly exchange of books and letters with Buchanan is therefore interesting. Of course, attempts by Wilde to curry favour with potential reviewers by sending them complimentary copies of his work was not unusual. Rather it is the reputation of Buchanan which makes this letter noteworthy.

[Note: The location of the letter is given as ‘HRHRC’, which is the Harry Ransom Humanities Research Center at the University of Texas and I’m assuming this is the letter referred to on the List of Locations of Buchanan’s Letters and Related Material page.]

|

|

|

|

|

|

|