|

Play List: 4. Corinne 7. The Mormons 9. Lucy Brandon 10. Storm-Beaten 11. Lady Clare 13. Bachelors 14. Constance 15. Lottie 16. Agnes 17. Alone in London 18. Sophia 19. Fascination 20. The Blue Bells of Scotland 21. Partners 24. Angelina! 25. The Old Home 26. A Man’s Shadow 27. Theodora 29. Clarissa 30. Miss Tomboy 32. Sweet Nancy 33. The English Rose 36. Marmion 37. The Gifted Lady 38. The Trumpet Call 39. Squire Kate 40. The White Rose 42. The Black Domino 44. The Charlatan 45. Dick Sheridan 47. Lady Gladys 48. The Strange Adventures of Miss Brown 49. The Romance of the Shopwalker 52. Two Little Maids from School ___ |

|

ROBERT WILLIAMS BUCHANAN (1841 - 1901) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

THEATRE REVIEWS 1. The Rath Boys (1862)

The Rath Boys; or Erin’s Fair Daughter |

|

|||||||

|

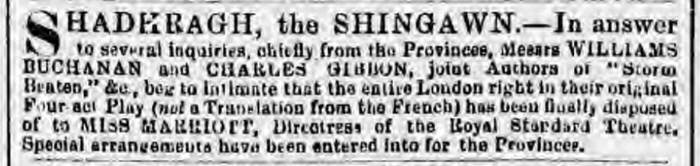

[Notice in The Era (13 April, 1862 - p.8).] |

|||||||

|

|||||||

|

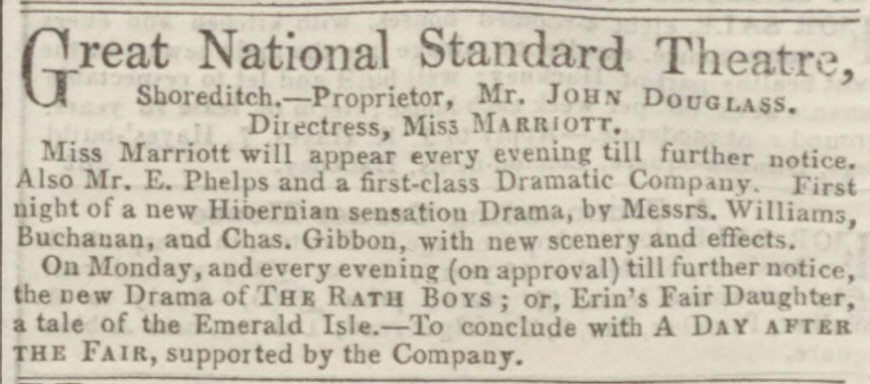

[Advert for The Rath Boys from The Times (17 May, 1862 - p.10).] |

|||||||

|

|

[Advert for The Rath Boys from The Shoreditch Observer (17 May, 1862 - p.3).]

The Athenæum (24 May, 1862 - No. 1804, p.701) STANDARD.—A new Milesian drama, with a sensation-scene, similar and much too like that of the Glen in ‘Peep O’Day,’ was produced on Saturday. It is the joint production of Mr. Williams Buchanan and Mr. Charles Gibbon, and entitled ‘The Rath-Boys; or, Erin’s Fair Daughter, (a tale of the Emerald Isle).’ From the poetical character of one of the authors, we had reason to expect a much better piece. The action of the first act is lively and vigorous, and points the position of the persons with sufficient clearness, but the conduct and interest of the remaining three are not equal. Nor is the dialogue of that quality which indicates careful writing. The hero is one Shadragh the Shingawn, who from the circumstances of his birth and nurture falls under suspicion of Rathboyism and murder, but of which crimes he is innocent. Thus reduced to the condition of an outlaw, he is compelled to live a life of concealment and peril, until opportunity occurs for his self-vindication; and even then, when he has nobly acted the part of deliverer, and saved the life of Ailleen O’Sullivan (Miss Marriott), he falls a victim in the final conflict, and dies as one who yields to an inevitable fate. The part of the hero was entrusted to Mr. Edmund Phelps, who laboured industriously to give to it interest and significance; but the dialogue was too meagre to furnish occasion for elocutionary power, and therefore failed to supply him with materials for dramatic effect. Among the characters is one that, for mere acting purposes, told remarkably well. It was that of an Irish lawyer, one Jeremiah Jordan (Mr. T. B. Bennett), a tall and thin specimen of Hibernian vivacity, dressed point-device, like a dancing-master, who suffers under the contempt of the peasantry whom he would eject from their tenements, and is the victim of many practical jests. The manner in which the idea is embodied is highly creditable to the performer. ___

The Penny Illustrated Paper (24 May, 1862 - p.14) On Saturday, at the STANDARD, a new Hibernian drama, in four acts, was produced, written by Messrs. Williams, Buchanan, and Charles Gibbon. It is entitled “The Rath-Boys; or, Erin’s Fair Daughter” (a tale of the Emerald Isle), and is of the “sensational” class. It is, in fact, a story contrived to lead up to a scene in a wild glen, similar to that at the Lyceum, of which it is, in fact, too close a copy. The first act of the new drama promised well, and was full of action. It showed how Shadragh the Shingawn (Mr. Edmund Phelps) came to be suspected of murderous intentions, though entirely free, while such wicked purposes were really carried out by other parties who, by his agency, are at last brought to justice. The characters were vigorously acted. One stood out from the canvas with remarkable power, that of Jeremiah Jordan (T. B. Bennett). This is a long-legged lawyer, eccentric in his manners, who becomes the butt of the tenants on whom he would serve writs of ejectment, is made drunk, and variously ill-treated; but who, though a coward, partakes in all the perils of the story and shares in its dénouement. Mr. Bennett embodied the idea admirably, and, indeed, acted so well that his part alone ought to procure a moderate run for the new venture. ___

The Era (25 May, 1862 - p.10) Standard.—A new piece of what is now popularly known as the “sensation” school, made its appearance here on Saturday night for the first time—and a very comely appearance too. Its title is The Rath-Boys; or, Erin’s Fair Daughter, and it is announced as from the joint pens of Messrs. Williams Buchanan and Charles Gibbon, who have succeeded in the main in producing a Drama replete with startling incidents, and abounding in effects which render it remarkably attractive. Although, here and there, there may be a point somewhat over-wrought, yet, as a whole, the materials of which the piece is composed are well strung together, and considerable merit is consequently due to its author. Without attempting to enter into the somewhat elaborate plots and under-plots necessary to the carrying out of the stirring business of the Drama, it will be enough to say that it is simply what it professes to be, “a tale of the Emerald Isle,” in which the main incident is the persecution of Ailleen O’Sullivan, an Irish girl, known as the “Rose of Killarney,” at the hands of the Captain of the ruffianly Rath-Boys, one Benjamin Brogden. Nor is this the only “dark deed” with which this man is connected, as will be easily judged by the many who are familiar with the criminalities executed by those who have formed the bands under the well-known titles of “Rath-Boys,” “White-boys,” “Peep- o’-Day-Boys,” &c. However, for our present purpose we have merely to deal with the circumstance as affecting Ailleen, especially towards the close of the piece, where she is saved by Shadragh, a deformed outcast, know as “Shadragh the Shingawn,” but of this anon. This Shingawn, it may be well to explain, is a sort of “elf-man,” who, according to Irish superstition, was a diminutive being, who assumed a distorted likeness of man for the purpose of resisting the “Thighas,” or fairies, in their dealings with men and women; and being found, when an infant, in ditches, fields, or out-of-way places, charitable farmers sometimes adopted him, but placed themselves and their families in great peril in the event of offending him when he reached man’s estate. We meet with one of these singular characters already arrived at mature age, as we have previously stated, and who acts throughout as the protecting watcher of poor Ailleen. The latter is played with pleasing care and truthfulness by Miss Marriott, who throughout the piece sustained the character with marked ability and consequent success; and it is scarcely necessary to add that her acting was richly relished. In one of the Scenes wherein dancing forms, as usual, one of the main elements of an Irish merry-making, Miss Marriott displayed no ordinary powers, and was vehemently applauded in consequence. Altogether, this clever Actress seemed to possess a very happy mode of delineating the Irish character, a task by no means easy of achievement. The singular part of the Shingawn was in the hands of Mr. Edmund Phelps, and it is, perhaps, not too much to say that in such hands nothing short of full justice to it was to be expected. With an exceedingly careful and well-ordered delivery, added to a thorough knowledge of what was required in the illustration of the character, Mr. Phelps rendered a part remarkably interesting, which, by a less able Actor, would have been much less striking. Mr. T. B. Bennett played Jeremiah Jordan, a tithe proctor’s clerk, with admirable humour, and won unlimited approval. Tony Flanigan, a warm-hearted Irish lad, who has a happy bent of being ready to help the distressed and succour the oppressed, mainly through the instrumentality of the clinching argument of the shillelagh, was in excellent hands in those of Mr. Thomas Thorne, who invested it with well- directed spirit, and closed it with the smart quaintness which belongs to what is best known in Irish phraseology as a “broth of a boy.” He sang a song, too, which was much approved. The Benjamin Brogden (of whom we have spoken) of Mr. E. F. Edgar, was not quite so happy, although not altogether lacking ability. Of the other numerous characters, which fell amongst Misses Mary Booth, Clarke, Medway, Calaster, Green, and Mrs. Edward Fisher; and Messrs. R. Norman, Colwell, Perfitt, J. Mordaunt, &c., &c., we have not space to speak further than simply to give them a word of general approval, as having tended materially to the successful development of the piece. The Maurice O’More of Mr. Edward Fletcher, by the way, was a piece of highly creditable acting. And now for the new Scenery, painted by Mr. Gowrie, which was from beginning to end exceedingly inviting, and admirably adapted to the various incidents in the Drama. The crowning Scene, the Glen of Ballybar by Starlight, was one of almost unequalled beauty. It is really not too much to say of it that, however great have been, and are, the merits of the beautiful Scenes which have shone so conspicuously, and have gained such fame at the Theatres which have become celebrated for “Sensation” pieces, the one in question has fair claim to be placed besides any of them, and we venture to say it would not suffer a jot in the comparison. It is in this magnificent Scene, with its accompanying snowstorm, that poor Ailleen finds herself forsaken for a time, and face to face with her persecutor, Brogden. After a fearful struggle, she hides amongst the rocks which overhang the torrent, but the ruffianly Rath-Boy closing up the only place by which she could escape, she makes a fearful leap, and hangs suspended by a branch over the yawning gulf beneath her, whilst her faithful protector lets himself down in the most marvellous manner by a rope, and saves her in his arms. It would truly be difficult to describe this extraordinary Scene according to its deserts. We can but add that it alone is worth a visit to see, to say nothing of the exceeding attractions of the piece itself. It is unmistakably one of the most inviting and exciting Dramas out, and richly deserves the patronage it receives. ___

The Glasgow Sentinel (31 May, 1862 - p.5) A NEW SENSATION DRAMA. ANOTHER sensation drama, written by Mr Williams Buchanan, the son of the former proprietor of this journal, and Mr Charles Gibbon, has been produced in London by Miss Marriott, with extraordinary success. We notice the fact, not because we admire the class of pieces to which this new play belongs, but because it appears to have strengthened the reign of sensation with several striking novelties, and because the authors are well known in this city. It is significant that the two theatrical organs of the metropolis—the Era and the Sunday Times—are unanimous in their praise of the drama. The Sunday Times, in an elaborate notice, remarks:—‘We have to record the production of another Irish drama, crowded with incident, rich in sensational effects, and illustrated by some very picturesque scenery. It is entitled “The Rath Boys.” The “Rath Boys,” like the “White Boys” and the “Peep o’ Day Boys,” are a band of adventurous patriots, not at all over-scrupulous as to the appliances by which they secure a living for themselves. . . . The play is well mounted. The sensation scene is capitally designed and arranged; it is called the glen of Ballybar, by starlight, and represents a waterfall on one side, a yawning gulf on the other, and some broken steps in the middle. . . . The applause, we need hardly say, was tremendous. Miss Marriott played the part of ‘Ailleen’ with life like effect, her acting in the glen scene being energetic and effective. Mr E. Phelps, as the deformed Glungawn, exhibited great care. The drama, which was enthusiastically received, has been written by Messrs Williams Buchanan and Charles Gibbon, and, with judicious curtailment, will enjoy a successful run. The principals were honoured with a call twice in the evening.’ The Era, in a most elaborate critique, says ‘It is announced as from the joint pens of Messrs Williams Buchanan and Charles Gibbon, who have succeeded in the main in producing a drama replete with startling incidents, and abounding in effects which render it remarkably attractive. The crowning scene—the glen of Ballybar by starlight—was one of almost unequalled beauty. It is really not too much to say of it, that however great have been, and are, the merits of the beautiful scenes which have shone so conspicuously, and have gained such fame at the theatres which have become celebrated for “sensation” pieces, the one in question has fair claim to be placed besides any of them, and we venture to say that it would not suffer a jot in the comparison. It is in this magnificent scene, with its accompanying snow-storm, that poor Ailleen finds herself forsaken for a time, and face to face with her persecutor, Brogden. After a fearful struggle, she hides amongst the rocks which overhang the torrent; but the ruffianly Rath Boy, closing up the only place by which she could escape, she makes a fearful leap, and hangs suspended by a branch over the yawning gulf beneath her, whilst her faithful protector (Mr Phelps) lets himself down in the most marvellous manner by a rope, and raises her in his arms. It would truly be difficult to describe this extraordinary scene according to its deserts. We can but add that it alone is worth a visit to see, to say nothing of the exceeding attractions of the piece itself. It is unmistakeably one of the most inviting and exciting dramas out, and richly deserves the patronage it receives.’ ___

The Glasgow Herald (7 June, 1862 - p.4) ANOTHER SENSATION DRAMA.—We observe that another drama of the “sensation” order, has recently been produced in London with striking success. It is entitled the “Rath Boys,” and is from the joint pens of Messrs. Williams, Buchanan, and Charles Gibbon, natives of Glasgow. The theatrical press of the metropolis is unanimous in praise of the drama. The Sunday Times characterises it as “crowded with incident and rich in sensational effects;” and the Era says, “It is unmistakeably one of the most inviting and exciting dramas out, and richly deserves the patronage it receives.” Miss Marriott, the favourite actress, and Mr. Edmund Phelps, sustain the principal parts with considerable ability. |

|||||

|

|||||

|

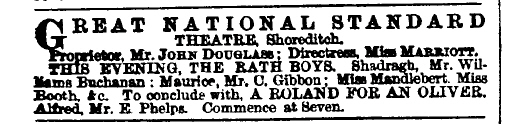

[Advert for a performance of The Rath Boys from The Evening Star (Wednesday, 18 June, 1862 - p.1)

From Chapter VIII of Robert Buchanan by Harriett Jay: The “Rathboys,” as the dramatisation was called, was produced in due course at the Standard Theatre, and ran successfully for some weeks. The leading character was played by Edmund Phelps, the son of the famous tragedian, and the “comic Irishman,” by Thomas Thorne, with whom one of the authors was to have delightful business relations many years later. Before the play was withdrawn from representation the authors appeared in it themselves, Mr. Gibbon taking the part of a young lover, and Mr. Buchanan that of the hero, called Shadrack the Shingawn. As they knew the play by heart they had no rehearsals. The part played by Mr. Buchanan was that of a hunchback falsely accused of murder, and he made the character so hideously disfigured a monster that somebody inquired whether he was representing Shakespeare’s Caliban. However, the audiences out eastward were not critical, and the performance passed off with a certain measure of applause. The crux of the performance came in the penultimate act, when Shadrack had to rescue the heroine from a violent death, descending by a rope from the top of a precipice, seizing the heroine in his arms as she swung over the abyss from the branch of a tree, and ascending with her to the cliffs above. For this effect, which demanded an athlete rather than an actor, there had, as I have said, been no rehearsal, and it is more than probable that the aspiring actor showed some little doubt and trepidation, for the lady whom he was to save was in agonies of terror. However, all went well. Shadrack descended by a rope from the flies, clasped the lady in his arms, and was drawn back amid round after round of deafening applause. |

|||||

|

|

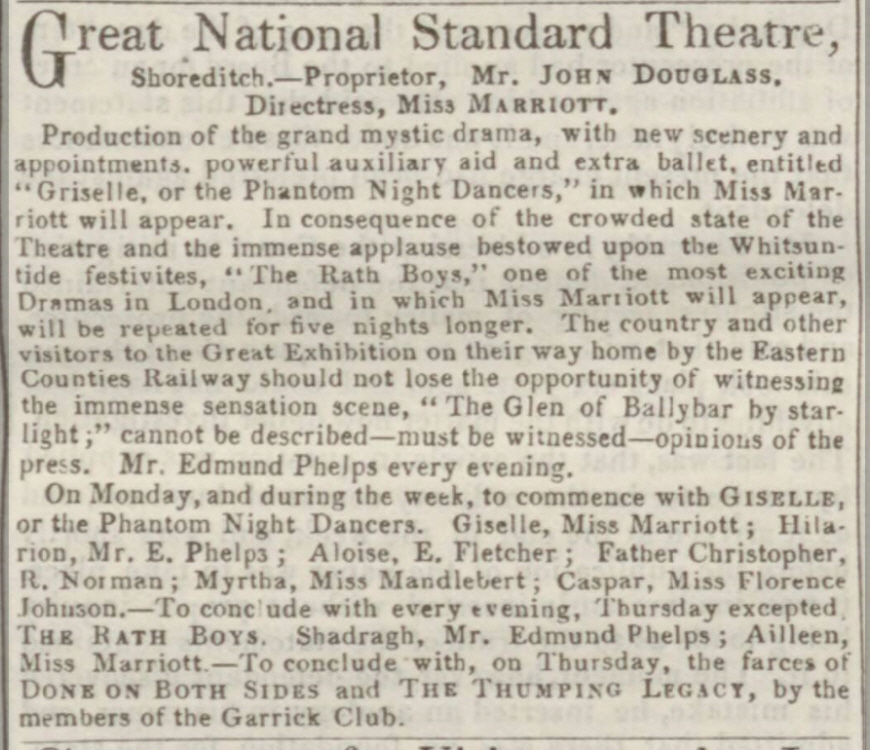

[Advert for The Rath Boys from The Shoreditch Observer (21 June, 1862 - p.4).] |

|

|

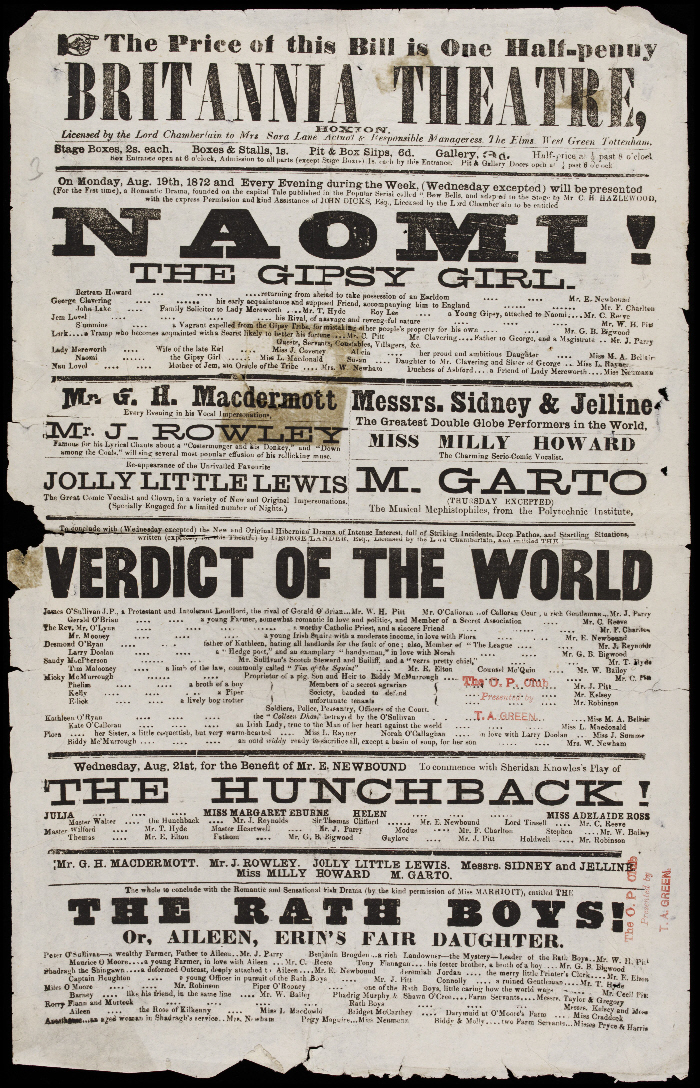

[Poster from the Britannia Theatre, Hoxton for August, 1872. Click the picture for a larger image.] ___

[Note: The list for the following year includes this: Which is confusing. Especially since on July 12, 1862, Reynolds’s Miscellany had published a story with the title: ‘The Shingawn; or, Ailleen, The Rose Of Kilkenny. A Mystical Romance of Ireland in the Eighteenth Century’ by Christopher Marlowe. Whether there is any connection between the three works is unknown ... and likely to remain so.]

Next: The Witchfinder (1864) Back to the Bibliography or the Plays

|

|

|

|

|

|

|