|

ROBERT BUCHANAN’S LETTERS TO ALFRED TENNYSON

The Tennyson Research Centre, housed in the dome of Lincoln Central Library, has seven of the letters Robert Buchanan wrote to Alfred Tennyson. I’d like to thank Grace Timmins, Collections Officer of the Tennyson Research Centre for her help with this section and for giving permission to place these transcripts on the site.

_____

Letter 1: 16th November [1864].

Woodlands Cottage

Iver

Uxbridge

Bucks

Nov. 16th

Sir,

You are doubtless familiar with the pathetic story of the young Scotch poet, David Gray, whose remains have endeared him to so many true lovers of our Literature; and you may have heard of the endeavour to collect a fund sufficient to erect some simple Memorial in the Auld Aisle Burying Ground at Merkland. My friendship for Gray, my interest in his family, and my desire to show that the most cultivated in the land are interested in my friend’s memory, must be my apology for troubling you unintroduced.

It has been suggested to me that the best way to complete the Monument Fund would be to compile & edit a small volume containing:

“The Memento by Lord Houghton; the Life, reprinted from the Cornhill Magazine; original contributions of a miscellaneous character from some few men of eminence; and some poetical remains of Gray: The whole to be Illustrated by a portrait of Gray (from a photograph in my possession) & a picture of the Cottage at Merkland.”

This Book, if blest with a moderate sale, would not only return money sufficient to erect a simple monument, but would leave a surplus sufficient to make the poor old father & mother of the poet, now very poor & pinched, more comfortable. Mr Gray sen., uneducated as he is, is a man to be loved & honoured: his heart is one of the gentlest & truest that throbs.

Of course the attraction of the volume in the eyes of general readers would be the original contributions; and my object in writing to you is to ask if you feel tenderly enough interested in the matter to let me have some few lines from your pen—no matter how few. I write by the same post to Mr Dickens & Mr Browning.

I prefer the request with some confidence, because I know how profoundly the writings & the biography of Gray must have touched such a mind as yours.

Believe me Sir

Very respectfully

Robert Buchanan.

Alfred Tennyson Esq. D.C.L.

&c. &c.

[’Granted’ written in pen in another hand opposite the address. (Grace Timmins of the T. R. C. has identified the handwriting as possibly that of Tennyson’s wife, Emily.)

‘1864’ written in pencil in another hand under the date. The year is correct since, as mentioned in the letter, Buchanan wrote to Browning on the same date.]

_____

Letter 2: 7th June, 1871.

Soroba

Oban

N. B.

June 7. 1871

My dear Sir,

I do not know whether you know much more of me than my mere name, but I am aware that you are familiar with that. Whether you feel for me that sympathetic interest which the greatest Poet should feel for the least, is doubtful,—for you may not consider me a poet at all. I only know that this letter is written in the dim hope that we have something in common—a tenderness, a sense of poetic brotherhood—and that can only be where two men, however far removed in amount of genius & position, have a divine gift in common.

It is in this dim hope that I write to you; having never written before in the same way to any one else: to ask you, in your great and nobly earned success, to lend me a helping hand through the shadows. I proceed on the assumption that you are rich—which may very well be a delusion; for I know how great may be the claims upon you. But if you are rich, & if you think me of poetic kindred however remote, will you tide me over a difficulty which threatens to drown me altogether. I need not tell you I have been ill,—the penny-a-liners will have told you that; or that my books do not as yet do much to keep me afloat,—for you know how slowly profit comes from earnest work in verse. I have been sick & ailing for years—with horrible cerebral symptoms—& scarcely able to lift a pen; but last autumn I revived suddenly, & have worked hard all the winter at my “Drama of Kings,” an ambitious Trilogy, which Strahan is just publishing. For month after month I sacrificed all to this work—night after night, week after week—and I do not fear the result; but besides all else, I calculated on getting £300 in cash for the Drama. It seems, however, that my works have not been selling so well lately—there are changes, too, at Ludgate Hill—and my Publishers wont do more than issue the Book at half-profits. Meantime, I am left in a sad plight—worn out with the dreadful winter’s work, my old infernal symptoms beginning in the brain, and no chance of a month’s summer rest when I have earned it so hard—& worried by debt, debt, debt. In this sheer despair, I turn to you, and ask—wonderingly, almost hopelessly—whether you will—or can— lend me £200 for six months—or a year—or such time as I can repay it by my literary work. If I only get a rest now & my brain relieved, I have no fear of the future,—large as are the claims on my income. It is a dreadful thing to be ill & poor too, and yet to feel that the constitution is elastic enough to endure some time if not too sorely prest. If my great brother Poet can help me at this pinch, he will not miss his reward—either here, by seeing me rising in honour and power, or there, by the approval of Him who rewards good deeds.

I should be deceiving you if I said that I expected much profit from the “Drama of Kings.” I do expect some fame & the approval of good judges; but the work is “over the heads” of the general public: who, though they will patiently buy anything from their favorites, will not be troubled with profundity—de profundis.

But I am only iterating what you know well. I need not explain what you will penetrate at a glance. Of one thing I am sure: that you will not be angry with me for proffering such a request as one loving friend might proffer to another, seeing that I do it in the name of Poetry,—and that I turn to you with that instinctive trust which Poets should have in one another. For my own part, I have never grudged time, money, thought, or love for others; and what I ask from you I have done in full measure to my fellows whenever I could.

Yours truly

Robert Buchanan.

Alfred Tennyson Esq.

Of course this letter is private. I should be sorry if Messrs. Strahan & Co heard of it, and you may guess why; but as for Strahan himself, he is a man in a thousand, & would do anything he could for me, as for a brother. Yet if even he heard of it, I should like it to be from my own lips.

R. B.

I made no arrangement for “Napoleon Fallen” before publication, & of course have not recd a penny for that either, as it has not sold sufficiently to leave a profit for the author.

[’amount to’ inserted before ‘genius’.

‘& scarcely able to lift a pen’ inserted after ‘cerebral symptoms’.]

_____

Letter 3: 14th June, 1871.

Soroba Cottage

Oban

Scotland

June 14 1871

Dear Mr Tennyson,

I hardly know what to say in answer to your letter, save that it brings the tears to my eyes. Since I wrote to you I have (as you may guess) been anxious enough, frequently wishing the letter back in my pouch; but what was done was done, & now I am heartily glad. I will say nothing more abt gratitude; I hope to be able to prove my sense of your goodness and sympathy by deeds not words.

You may believe that I should not have written to you unless under very violent pressure indeed; though I shrunk from details, lest they should have, as they always do, a whining appearance. Enough to say that I saw no other resource but my great brother Poet; and his goodness should do me good in more ways than one, for it should strengthen that faith in human kindness which alas! sometimes fails the best of us. In good truth, I have so worn down my strength by this winter’s work—have let so many claims run on in order to work at my beloved verse—that I am as you find me. What I dreaded most was another attack such as I had a year or so ago—the cerebral pressure is soon caused & slow, very slow, to cure;—and unless I could rest a little from work now, I looked forward to the coming winter with horror. With your noble aid, I shall get breathing time, & ward off fresh illness—to say nothing of the annoyance which always ensues from debts & dues.

You may certainly rely on my repaying the money as soon as I can, though, as I said, I hardly expect to do it through my “Drama of Kings.” Yet the work may be more popular than I expect, for I have often found these matters regulated by others quite beyond the author’s knowledge or control.

My permanent address is as above. Believe me with sentiments far too strong to phrase in a letter

Yours faithfully

Robt Buchanan.

Alfred Tennyson Esq.

[‘in some’ crossed out, ‘and’ written above, before ‘sympathy by deeds’.

‘make’ crossed out, ‘do’ written above, before ‘me good in more ways’.

‘dreaded’ crossed out, ‘looked forward to’ written above, before ‘the coming winter’.

The last part of the final sentence of the second paragraph was particularly difficult to decipher. After ‘ensues from’ Buchanan starts to write ‘obligat[ions]’, crosses this out and writes ‘debts’, crosses out ‘and’, writes ‘&’ above, and my best guess for the final word is ‘dues’.]

_____

Letter 4: 20th June, 1871.

Soroba Cottage

Oban

N. B.

June 20. 1871

My dear Mr Tennyson,

I have just recd your cheque for £200—for which generous loan again receive my grateful thanks. I shall only ask one more favor by & by—that some of these days, when we are in the way of each other, I may shake you by the hand.

With kind regards believe me

Yours faithfully

Robert Buchanan.

Alfred Tennyson Esq.

_____

Letter 5: 16th November, 1871.

4 Bernard St

Russell Square

W.

Nov. 16. 1871

My dear Mr Tennyson,

I hope you will like the Drama. It is unfortunately an experiment in literature, and is very likely a failure; but still, I would rather fail originally, than follow mincingly in the footprints of other Poets. I do not press you for your opinion—I know the cruelty of requesting that—but if it should come into your mind to say a word or two to me privately on the subject, I should feel grateful. There are not six men in England for whose opinion I care, & I need hardly say you are one.

I fear this book wont put much into my pockets, as it has few elements of popularity; but I am labouring in other ways, and do not forget my obligations.

Are you ever in Town? and if so, may I pay my respects to you? It would give me unalloyed pleasure to see & speak with you for even so short a time.

Believe me in the meantime

Ever yours truly

Robert Buchanan.

Alfred Tennyson Esq.

[‘requesting’ inserted after ‘cruelty of’.

“the Drama” is Buchanan’s The Drama of Kings which was published in November, 1871.

Buchanan’s reference to “labouring in other ways” presumably refers to St. Abe and His Seven Wives which was published anonymously in December, 1871.]

_____

Letter 6: 28th November, 1871.

4 Bernard St

Russell Square

W.

Nov. 28. 1871

My dear Mr Tennyson,

Are you rich enough & lenient enough to add to the enormous obligations you have already laid me under and lend me another £100? I know the utter daring of such a proposal, but I fancy your almost supernatural goodness has turned my head; I have, moreover, seen you, & felt your personal kindness. It is needless to say that my great extremity presses me to ask you, at the almost certain risk of offending you. The “Drama of Kings” will not give me a penny—it will yield me no cup but critical abuse—but that I should not mind, if I did not need money so much; for even regarding the drama as a failure in every sense, I know well a dozen such failures would not keep me from rising to the summit of modern thought in time.

But, strictly in confidence, let me say that I have other work of a more successful kind slowly making its way, and that what that work has already done for me makes it next to certain that I shall have plenty of money in a month or little more. Indeed, I have every hope of being able in in Janry to pay the debt I owe you; and then visiting you in the Isle of Wight. For I cannot summon up heart to be your guest till I have returned you what you so generously lent me.

You will guess, perhaps from your own reminiscences, that I have no means of getting money apart from work. Moreover, I have no wealthy friends, no connections, no anything.

While profering this request, I am obliged to comment on another matter which will almost certainly awaken your displeasure with me. I had written for the “Contemporary” a paper on Goethe, of which Strahan strong approves; the first half of it was to appear this month; but at the last moment, your friend Mr Knowles has interfered & insisted on my paper’s suppression. Knowles’s letter is so venomous, so severe, & so unjust, that it simply amazes & puzzles me. He accuses me of “an impertinent tone throughout,” of “immodesty,” and of incapacity to judge men “of infinitely greater powers than myself:” the reference, I fancy, being to a passage in which I speak of Carlyle’s criticisms.

The paper—a proof of which I will send to you & must beg you to read—is, so far as it is printed, a strong, a very strong, study of Goethe’s personal character & its effect on what I call the cerebellic autobiographies of “Wilhelm Meister” & “Faust.” It may be poor & weak, but I question if it is impertinent. It is a protest on a style of thought which, I believe, has been the curse of modern literature, & written by me, God knows, from a religious sense of duty, however mistaken my conclusions may be. I have no object but truth & justice, & of true reverence for worth I am not scant.

So far from irreverence, I have but again & again been accused of hero-worship, only my idols are not the world’s. I have had recently, for example, to defend your own poetry recently from certain false inferences made by Miss West in her criticism on Browning, & I have so far succeeded as to make her admit her mistake as to the ethic grandeur of your teaching. I reverence living men,—Emerson, Browning, Darwin, yourself. I do not reverence Lies in any shape, even on the lips of a demigod; and I will protest against such Lies, as I deem them, with my latest breath. And that is all my present fault—to have expressed what many feel but dare not phrase.

You must bear with me, but I really must reject the criticism, or any criticism, from a man who, in my hearing, described Whitman, that noble & almost Christ-like man, as “an unmitigated Prig.”

Mr Knowles has done me more injustice than this. He has broken confidence as to my authorship of the article on Rossetti, & led to the inference that I wilfully took a false name. Strahan can tell you that he (Strahan) coined & affixed the name to the article, without my knowledge, when I was far from the spot. It was a weak & badly written article, I admit, but I flinch from none of its opinions.

It is a poor plea, but this unjust interference with the publication of the article is exactly £70-70/ out my pocket—no small sacrifice at this moment.

Having thus almost certainly indicted all sympathy from you—for I know your friendship for Mr Knowles and your close intimacy—I must express my extreme pain that anything of the kind has occurred to interfere with our relations. How gratefully, how intensely, I believe in you, I need not say: otherwise, should I have bared my feelings so openly? But I risk all misconstruction, knowing that I have nothing to hide, & that my conscience accuses me of no fault; and with my deepest apologies for troubling you again in any way believe me

Most faithfully your friend

Robert Buchanan.

Alfred Tennyson Esq.

I shall publish the paper in the “Westminster Review,”—only unfortunately they cant pay for contributions.

I need scarcely say that I trust Mr Knowles is ignorant of what you have done for me: not that I fancy you would mention it, but it might be involved in the business he transacts for you. Nor do I forbid you to discuss the matter, if you have confidence he wd: not misconstrue my conduct. I have not. There is nothing in any of my short relations with you for which I blush, of which any high-minded man would not feel proud;—for what you have done honours both of us—you in the giving, me in the taking. I am proud of your sympathy & confidence, and I glory in the obligation which ennobles you for ever in my eyes.

R. B.

[‘? I would not ask you’ crossed out after ‘laid me under’.

‘your’ crossed out, ‘the’ written above, before ‘utter daring’.

The repeated ‘in’ before ‘Janry’ is Buchanan’s error.

‘with me’ inserted after ‘displeasure’.

‘the first half of’ inserted before ‘it was to appear’.

‘(Strahan)’ inserted after ‘Strahan can tell you that he’.

‘the’ crossed out before ‘its opinions’.

‘I have not.’ inserted after ‘misconstrue my conduct.’

Buchanan wrote to Browning on 6th December asking him to repeat his loan of £20, so presumably Tennyson refused to lend Buchanan the £100.

The “other work of a more successful kind” is St. Abe and His Seven Wives.

Buchanan’s essay, ‘The Character of Goethe’ was published in The New Quarterly Magazine in October, 1874 and was reprinted in his 1887 collection, A Look Round Literature.

‘Mr. Knowles’ is James Knowles, architect, close friend of Tennyson, and at this time, editor of the Contemporary Review.

“Browning as a Preacher” by Miss E. Dickinson West was published in The Dark Blue in October and November, 1871.

Buchanan’s ‘The Fleshly School of Poetry’ was published in the Contemporary Review in October, 1871 under the pseudonym Thomas Maitland. Buchanan admitted to being the author of the article in a letter to the Athenæum published in the issue of 16th December, 1871 (an earlier letter from Alexander Strahan denying Buchanan’s involvement was also published in the same issue).]

_____

Letter 7: 4th June, 1873.

Chatsworth House

Abbey Road

Grt Malvern

June 4. 1873

My dear Mr Tennyson,

What I wanted you to understand was not abt Mr Knowles but abt the impossibility of my ever having countenanced my wife in writing to you as she did. What I meant was painfully simple, & I wish you had alluded to it.

As to Mr Knowles, neither you nor any one will hear me abuse him again, since you think him worthy. Perhaps my hot blood gets into my eyes & blinds me, & I daresay you are right. Only, you are surely unjust in attributing my hostility to his rejection & censure of my article on Goethe. I referred solely to these facts:

(1) that when I met him in your company he openly sympathised with my Fleshly Article; (2) that directly afterwards, secretly incensed agt me (I dont know why, except that he was jealous of my seeing you) he communicated with Mr Sydney Colvin & others, trying with all his might to shift all the responsibility upon me; (3) that his attitude throughout seemed “cowardly” & “malignant”; & (4)—but there, let that fly stick to the wall. I have been vilely used in this matter, & you can only know half the truth; but for your sake I will only believe “some one has blunder’d,” meaning no harm.

Nothing in the affair pains me but the pain it may cause you. My obligations to you are great, but the affection I feel towards you—since I have seen you—is over & above all such thoughts. I hope therefore that you will understand me —

If you stay long in the Isle of Wight I should like to see you some day. I’m not well enough yet to visit, but I might perhaps see you en passant. My doctor tells me to get sea-air, & I might be in your neighbourhood. Whether we soon meet or not believe me now & always,

Your sincere

Robert Buchanan.

Alfred Tennyson Esq.

[‘was’ crossed out, ‘seemed’ written above, before “cowardly”.

Buchanan spent several months of 1873 in Great Malvern undergoing the hydropathic treatment.

Sidney Colvin was a supporter of Rossetti, whose name was attached to the first indication in print (in the ‘Literary Gossip’ column of the Athenaeum on 2nd December, 1871) that Buchanan was the author of ‘The Fleshly School of Poetry’.]

_____

One letter written by Tennyson to Buchanan during this period survives. Duke University has the original, and it was published on page 19 of The Letters of Alfred Lord Tennyson - Volume III: 1871-1892 edited by Cecil Y. Lang and Edgar F. Shannon, Jr. (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1990):

November 19, 1871

Dear Mr. Buchanan

I shall if all be well, be at my lodgings, 16 Albert Mansions, Victoria St., next Wednesday morning at 11 or thereabouts. I am at the top of the house, second door to the left at the top of the stairs. If you care to call I shall be glad to see you and perhaps I may persuade you to come and spend a day here: I am only an hour and a half from town. Believe me,

Yours very truly

A. Tennyson

I have read part of the beginning of your book, which lacks neither force nor fire.

_____

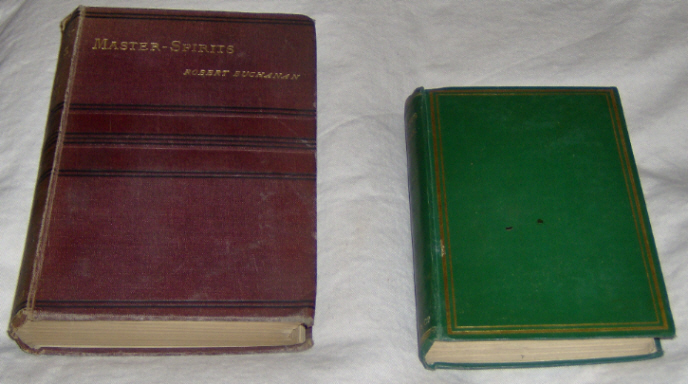

As well as the seven letters, the Tennyson Research Centre also has Tennyson’s copies of two of Buchanan’s books: Undertones and Master-Spirits.

|