|

Play List: 4. Corinne 7. The Mormons 9. Lucy Brandon 10. Storm-Beaten 11. Lady Clare 13. Bachelors 14. Constance 15. Lottie 16. Agnes 17. Alone in London 18. Sophia 19. Fascination 20. The Blue Bells of Scotland 21. Partners 24. Angelina! 25. The Old Home 26. A Man’s Shadow 27. Theodora 29. Clarissa 30. Miss Tomboy 32. Sweet Nancy 33. The English Rose 36. Marmion 37. The Gifted Lady 38. The Trumpet Call 39. Squire Kate 40. The White Rose 42. The Black Domino 44. The Charlatan 45. Dick Sheridan 47. Lady Gladys 48. The Strange Adventures of Miss Brown 49. The Romance of the Shopwalker 52. Two Little Maids from School ___ |

|

ROBERT WILLIAMS BUCHANAN (1841 - 1901) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

THEATRE REVIEWS 51. The Mariners of England (1897)

The Mariners of England ’Twas In Trafalgar’s Bay or Trafalgar A letter from Harriett Jay to The Era (30 April, 1898) announced that she and Buchanan were disassociating themselves from all future productions of the play on the grounds that “the attempt to celebrate the achievement of a real national Hero has been construed, in some quarters, into sympathy with more ignoble manifestations of the national (or Jingo) spirit”.

The Era (14 November, 1896) “THE MARINERS OF ENGLAND,” the new nautical drama by the authors of Alone in London, is in active preparation for early production in London and the provinces. It is founded on new and as yet unpublished facts connected with Lord Nelson, whose full and definitive biography is announced for publication in March next; and the same materials have been used by Mr Robert Buchanan for a new story, which is now in the press. Nelson is a leading character in the play, the scene of which is laid at the beginning of the present century. The scenery is already in hand, and a copyright performance will take place in a few days. ___

The Pall Mall Gazette (18 November, 1896) As usual, there are few interesting announcements to make this week. We read that Mr. Buchanan has collaborated with Miss Harriett Jay in a nautical “drama,” and we hope it will be rollicking. Also that Mr. Buchanan’s “Sweet Nancy” will be revived in the afternoon at the Criterion by Miss Annie Hughes. ___

The Yorkshire Evening Post (19 December, 1896 - p.3) Messrs. Robert Buchanan’s and Charles Marlowe’s new piece, Ye Mariners of England, is to be tried on the provincial dog by Mr. Herbert Heath, preparatory to a “London production.” The great scene is the death of Nelson on board of the Victory. Lady Hamilton will not be introduced. ___

The Referee (24 January, 1897 - p.3) The aforesaid Mulholland has arranged to produce at his Grand Theatre, Nottingham, on March 1, that other Nelsonian—or somewhat Nelsonian—play which I mentioned last week, namely, “The Mariners of England,” by Robert Buchanan and “Charles Marlowe.” The rights of this play have been secured by Mr. Herbert Sleath, who will tour with it through the spring, previous to bringing the piece to a West-end Theatre. The play is in four acts and ten tableaux, and—N.B., it has no Lady Hamilton. ___

The Daily News (17 February, 1897 - p.7) We have already noted that the Avenue Theatre is not to have any monopoly either of Nelson or the naval drama. It is now definitively announced that Mr. Herbert Sleath, late a member of one of Mr. Weedon Grossmith’s touring companies, will produce “The Mariners of England,” by Robert Buchanan and Charles Marlowe, at the New Olympic Theatre on the 9th of next month, with Mr. W. L. Abingdon and Mr. Charles Glenney in leading parts. We are particularly requested to observe that, although Nelson will be a conspicuous figure in the play, he will be represented “simply as the great naval hero,” and there will be “no Lady Hamilton.” The following list of the scenes painted by Mr. Bruce Smith and Mr. Walter Drury will give some hint of the character of the drama: “Act 1, The old Town of Deal and view of the Downs—‘The Anniversary.’ Act 2, scene 1; The Cliffs between Deal and Dover; scene 2, Fairlight Cove, Moonlight—‘The Escape.’ Act 3, Deck of H.M.S. Victory, Portsmouth Harbour; scene 2, State Cabin of the Victory; scene 3, Deck of the Victory, Trafalgar; scene 4, The Cockpit of the Victory—‘The Death of Nelson.’ Act 4, Interior of Admiral Talbot’s House—‘Father and Son.’” ___

Daily Mail (17 February, 1897 - p.3) The company engaged by Mr. Herbert Sleath for his season at the Olympic with Mr. Robert Buchanan and “Charles Marlowe’s” new nautical drama, “The Mariners of England,” includes Mr. W. L. Abingdon and Mr. Charles Glenney. The synopsis of scenery is as follows:—Act I.—The Old Town of Deal and view of the Downs (Mr. Bruce Smith), “The Anniversary.” Act II.—Scene 1: The Cliffs between Deal and Dover; scene 2: Fairlight Cove, moonlight (Mr. Walter Drury), “The Escape.” Act III.—Scene 1: Deck of H.M.S. Victory, Portsmouth Harbour; scene 2: State cabin of the Victory; scene 3: Deck of the Victory, Trafalgar; scene 4: The cockpit of the Victory (Mr. Bruce Smith), “The Death of Nelson.” Act IV.— Interior of Admiral Talbot’s house (Mr. Bruce Smith), “Father and Son.” The play will be produced on March 9. ___

The Era (20 February, 1897 - p.14) WE are requested by Mr Robert Buchanan to contradict the statement which has been made that he has become the manager of the Olympic Theatre. Although a drama of which he is part author is about to be produced at that establishment he has no connection with the production except an artistic one. The responsible manager of the theatre is Mr Herbert Sleath, who has secured the acting rights of The Mariners of England for both London and the provinces. “THE MARINERS OF ENGLAND,” by Robert Buchanan and Charles Marlowe, is a romantic costume play, in four acts, to be produced at the Olympic Theatre on or about March 8th. Among the company engaged to appear in it are Mr Charles Glenney, Mr Abingdon; Miss Edith Bruce, Miss Florence Tanner, and Miss Keith Wakeman. The new scenery is being painted by Mr Bruce Smith and assistants and the Messrs Drury; and the costumes are being specially made by Messrs Morris Angel and Co. The time is 1805, the year of Trafalgar, and one of the great effects of the play is a scenic reproduction of the great battle and the death of Nelson. ___

The Referee (21 February, 1897 - p.3) The Olympic again closed to-night (Saturday). A good tour has, however, been booked for “A Free Pardon”—and its Record Rain. The theatre passes into the hands of Mr. Sleath, who, as Refereaders have been duly notified, will present there on or about March 8 that other Nelson play “The Mariners of England,” by “Charles Marlowe” and Robert Buchanan, who desires all and sundry to take notice that he is in no wise connected with the management of this house. Inasmuch as this “Nelson” play contains no Lady Hamilton, but is run on strictly heroic lines, it is not likely that anyone will need to ask a Question in the House concerning it. It would not surprise me to hear next week of more litigation concerning the Olympic. Neither, I suppose, would it surprise you overmuch. ___

The Morning Post (22 February, 1897 - p.6) At the Grand Theatre, Nottingham, on Monday next, Mr. Mulholland has arranged for the first production of Robert Buchanan and Charles Marlowe’s new play, “The Mariners of England.” Mr. W. L. Abingdon has been specially engaged to play the part of Nelson, and the company will include Mr. Charles Glenney and Miss Edith Bruce. The scenery will be elaborate, and the climax of the play will be the Battle of Trafalgar as viewed from the Victory. As at present arranged the piece will be brought to the Olympic Theatre the following week, opening Tuesday, March 9. ___

Pall Mall Gazette (24 February, 1897 - p.1) So there is to be another Nelson play. “The Mariners of England,” by Mr. Robert Buchanan and “Charles Marlowe,” is to be produced at the Olympic (where “The Free Pardon” stopped on Saturday) on the 9th of next month. We suppose it will be patriotism undiluted; in fact, we read that Nelson’s unfortunate domestic arrangements will not be alluded to. The whole of the last act will take place on the Victory and end with the death of Nelson. We look forward to the play. Mr. Abingdon seems to be tired of villainy; at least we presume that Nelson, whom he will play, will not be the villain of the piece. Cromwell was made the villain of a play, but his services to England were a little more dubious than Nelson’s. We should rather like to see a set of historical plays with the traditions of character reversed—Richard III. as a good hero, and Bishop Wilberforce, or somebody of that type, as a villain. The woman’s hat question has been somewhat drastically dealt with by the Brussels police, who have published a prohibition against the wearing of such headgear in the stalls and dress circle of any theatre in that capital. The effect of this ukase has, however, not been wholly satisfactory, for the fair sex, taking exception to it, decline to patronize theatrical entertainments, with the not unnatural consequence that the attendance of the sterner sex has also fallen off to a very considerable extent. It is difficult to see how the Brussels managers will be able to grapple with the difficulties of a position that threatens to play havoc with their treasuries. Surely, in these days of arbitration some equitable adjustment of this highly important matter might be arrived at. ___

The Era (6 March, 1897) “THE MARINERS OF ENGLAND.” A New and Original Nautical Drama, Lord Nelson and Bronte ... Mr W. L. ABINGDON (FROM OUR OWN CORRESPONDENT.) Admiral Field’s conclusion that Lord Nelson’s memory had been treated with but scant respect in a recently- produced drama and the same gallant officer’s subsequent fiery question in the House of Commons as to what the Government were going to do about it, followed up by his forcible remark at the North London Rifle Club that “he would before long have the Lord Chamberlain’s department on toast,” will, no doubt, be a splendid advertisement to any play having among its dramatis personæ the hero of Trafalgar, and people will flock to the theatre if only to witness the treatment accorded in the new piece and apart from its merits as a work of dramatic art. The Mariners of England, in the words of one of the authors, “does not touch in any way on the Lady Hamilton intrigue, and, indeed, the great naval commander is rather the deus ex machinâ than the hero of the drama, which may be described as a simple story of original invention with an historical background.” No ideals are shattered by the authors of this piece, Messrs Robert Buchanan and Charles Marlowe; in fact, Nelson is just pictured as most of his admirers have from boyhood upwards fondly regarded him—a brave sailor, a beloved captain, and a man who made it possible for Englishmen to sing “Britannia Rules the Waves,” and who, in the end, gave his life for his country. All that is best worth remembering in the admiral’s life has been focussed into The Mariners of England, and the only regret is that the picture thrown upon the stage is not a larger one. With the exception of the one great incident, “The Death of Nelson,” the authors make no pretence to actual fact, and, truth to tell, the story might just as well have been written round any other naval character. For the greater part of the play Nelson is outside it altogether. ___

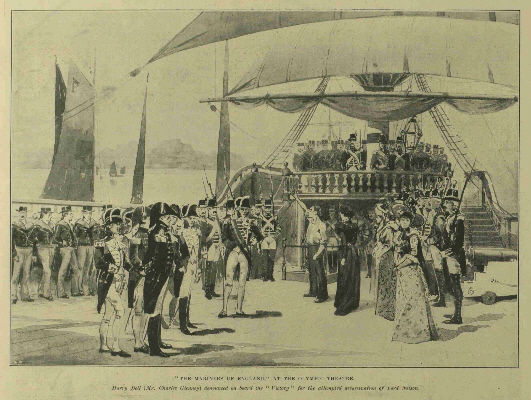

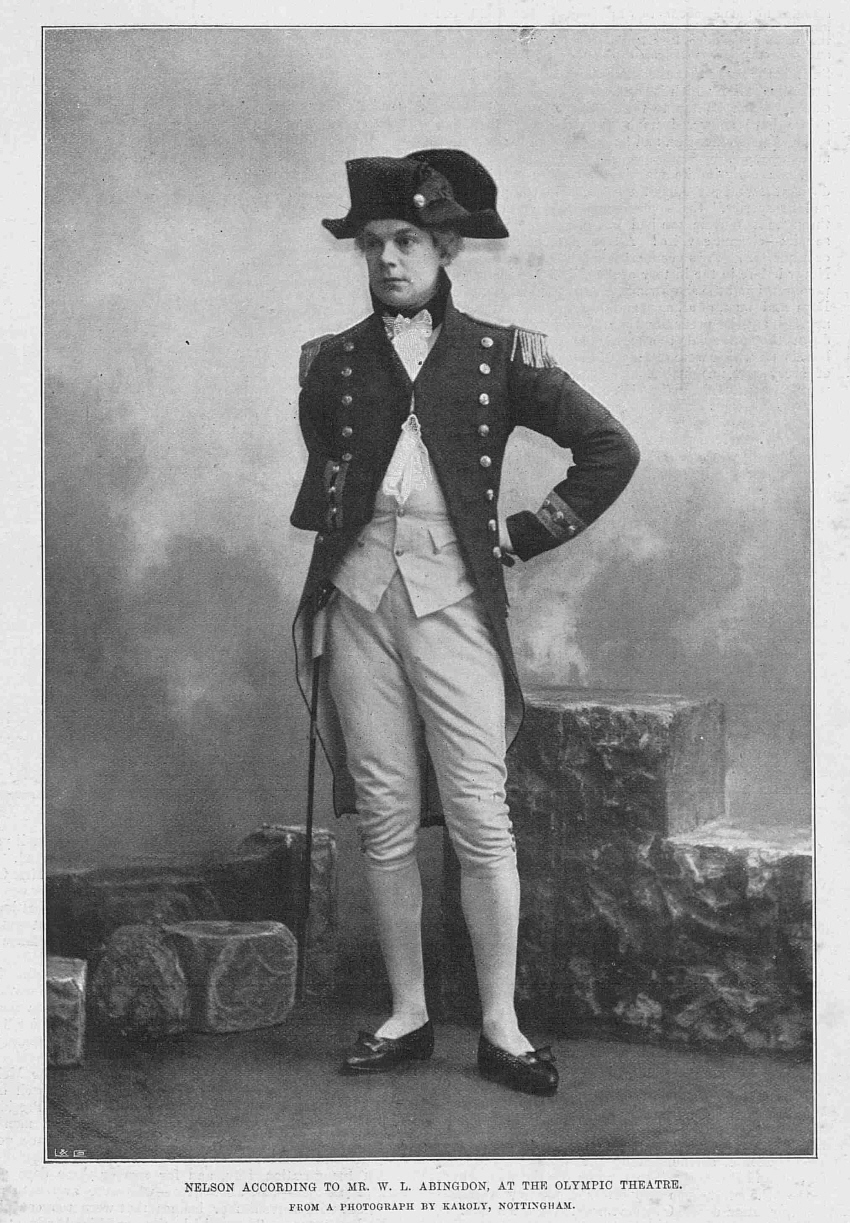

The Morning Post (10 March, 1897 - p.3) OLYMPIC THEATRE. “The Mariners of England,” a new and original romantic drama, written by Messrs. Robert Buchanan and Charles Marlowe, was presented for the first time last night at the Olympic Theatre. It received a favourable reception, which is largely to be accounted for by the subject of the play, in which Nelson figures conspicuously, although he is not the hero of the action, by the excellent stage mounting and brightness and variety of the scenes, and by the plentiful distribution of such sentiments as “Nelson’s left arm is the right arm of England” and “The man who fights for his country in any capacity is a gentleman.” The four acts into which the piece is divided are of very unequal merit. The first, though purely introductory, is bright, well written, and interesting, promising a story above the level of average melodrama. We are made acquainted with the love of Mabel Talbot, Admiral Talbot’s niece, for a typical bluejacket named Harry Dell. He has been picked up from a wreck, and his parentage is unknown, which naturally fills every spectator with a conviction amounting to certainty that he will ultimately be shown to be of birth equal to that of his sweetheart. And this proves to be the fact; in the last scene he is declared to be the Admiral’s son, and, of course, he marries Mabel. This, though not a very original, is no doubt a wise dispensation of the authors, for there unquestionably exists a prejudice against the affection of a lady of gentle birth for a lover of low degree; though, singularly enough, there is no such feeling regarding the love of the nobleman for the peasant maid. The second act, laid on a cliff near Dover, not far from the Admiral’s house, falls into one of the gravest errors of melodrama—the want of probability. There is a diabolical plot, hatched by Captain Lebaudy, the Admiral’s relative, who loves Mabel and has seduced Harry Dell’s sister, to take Nelson’s life. For this there is, we believe, no historical warrant whatever; the authors, however, are perfectly justified in introducing such an event if it suits their purpose. But they should so have arranged the attack on Nelson as to make the scene appear likely. Nothing could be more improbable than that the hero of the Nile should be set upon by a couple of ruffians on a bright moonlight night within a stone’s throw of the house where he was staying, and almost within call of the Coastguard, who a minute before have been parading the stage. Nelson is stunned, but Harry Dell is opportunely close at hand; he rushes in to the rescue, puts “Black Jack,” the villain in Lebaudy’s pay, to flight, and being wounded, is in true melodramatic fashion accused of having done the deed himself. The patrol surrounds him, but he knocks three of them down, and makes his escape, jumps into the sea, and presumably swims over to France. The third act is on board the Victory in Portsmouth Harbour. She is making ready to sail, and Nelson takes command. Before she weighs anchor Harry Dell appears; finding life unendurable in foreign parts, he gives himself up, protesting, however, that he is innocent. He is at once tried by court-martial and found guilty. Nelson, to whom “Black Jack” has meanwhile revealed the entire truth, intervenes, forces Lebaudy to confess his guilt and resign his commission, and then gives fresh evidence to the Naval Court, which enables them to reverse their judgment. Dell is acquitted. Here the play ends, but there are two tableaux vivants and a fourth act before the curtain finally descends. The first tableau represents the deck of the Victory at Trafalgar. It is a triumph of stage scenery. Nelson is struck down, and then we are taken to the cockpit, where he dies. This scene suffers from comparison with the similar infinitely more pathetic spectacle at the Avenue Theatre. The subject is a well-worn one, and there is nothing in its treatment by the authors of “The Mariners of England” or by the actors to lift it out of the region of commonplace. For all that the representation of the national hero’s death will in all circumstances command the applause of Englishmen; and it did not fail to do so on this occasion. The last act, every incident in which had been discounted by the audience, was unnecessary and tedious. Nelson was personated with dignity and some feeling by Mr. Abingdon, Harry Dell by Mr. Charles Glenney, an excellent representative of the traditional nautical hero of melodrama. The acting of the other characters calls for no particular comment. The authors were called for at the end, and bowed their acknowledgments. On the whole “The Mariners of England” is in tone considerably above the average melodrama, and this taken in conjunction with the success of “The Two Little Vagabonds” at the Princess’s, would seem to indicate that the public, at the West-end theatres at all events, is beginning to take pleasure in plays in which the colour is laid on with a more delicate hand than in the days of our fathers. ___

The Standard (10 March, 1897 - p.5) OLYMPIC THEATRE. It is quite impossible to treat seriously the melodrama by Messrs. Robert Buchanan and Charles Marlowe produced at the Olympic Theatre last night under the title of The Mariners of England. Historical names figure in the list of characters; Lord Nelson, Admiral Collingwood, and Captain Hardy are here; but they are preposterously employed, and it is an entire mistake to imagine that a very poor play is improved by introducing perversions of history and caricatures of great men. The authors found their plot on the set basis of commonplace melodrama. The hero is accused of a crime that is in truth instigated, if not actually carried out, by the villain, and, as usual, the representatives of virtue and vice are both in love with the heroine. In Mr. Gilbert’s Pinafore the common sailor loved the captain’s daughter; in The Mariners of England he loves the Admiral’s niece, who throws herself at his head in a manner which is only paralleled by the behaviour of the low comedian’s sweetheart, when in scarcely franker terms she asks him to marry her. The crime of which the sailor is accused is an attempt to murder no less a personage than Lord Nelson himself. While taking a solitary stroll on the cliffs near Dover, he is assailed by a French spy, egged on by an English naval captain; Dell, as the sailor is called, arrives at the critical moment, and the routine of melodrama is scrupulously followed. As is customary in such cases, his position is misunderstood, and he is assumed to be guilty of the crime he has prevented. This leads to a reproduction of the familiar court-martial scene in Black Eyed Susan, except that Dell is allowed more scope in the way of speeches—previously the whole routine of duty on board her Majesty’s ship Victory had been suspended while the sailor addressed his captain and the ship’s company at great length. The Admiral’s daughter continually hangs round his neck during the proceedings. As a matter of fact, Nelson knows the truth about the assault on him, and is perfectly aware of Dell’s innocence; why he allows the court-martial to waste so much time, during which he practically acts as counsel for the prisoner, is incomprehensible. Dell is not only acquitted, but made a Lieutenant on the spot, and in that capacity is found occupying a prominent place in two tableaux, which show Nelson being wounded and his death in the cockpit of the Victory. ___

Pall Mall Gazette (10 March, 1897 - p.3) “THE MARINERS OF ENGLAND,” AT THE OLYMPIC. We have no particular congratulations to offer to the authors of “The Mariners of England,” who are Mr. Robert Buchanan and “Charles Marlowe.” There are (more or less) interpolated into their play two very good tableaux—they are a little more than tableaux, since there is a little action and dialogue before the curtain falls, but the programme’s description is near enough—and these we presumably owe to somebody else, to say nothing of the original painters from whose pictures they are taken. There is an excellent piece of acting on the part of Mr. Abingdon, and in one or two other cases commendable acting. But the play itself is a poor thing. The plot is thin and foolish even for melodrama, and there is a prevailing air of “Black-Ey’d Susan” about it; an honest tar for hero, a captain for villain, and a pathetic court-martial. There is a grave fault of sentiment in the first act. The villain has (1) kept back the true secret of the hero’s birth, and (2) accused him of murder, knowing him to be innocent. These are possibly venial errors; but (3) being an officer in the King’s service he has been in the pay of the French, and (4) in their interest plotted the assassination of Nelson. Now these last two are not venial errors, either from the melodramatic or sociological point of view. Yet, if you please, this (so far) excellent villain is made to repent in Act IV., is allowed to marry the second heroine, and is positively hand-shaken by the hero. We are sincerely sorry that we stayed for that last act, in spite of its containing the hero’s discovery of his long-lost father, who (by the way, and so far as we could gather) had started life as a common sailor, worked his way up to admiral, and been blind all the time. No, the plot was not much, and the comic relief was the poorest we have seen for a long time. ___

The Daily Telegraph (10 March, 1897 - p.5) OLYMPIC THEATRE. If all the admirals of her Majesty’s fleet, bound in honour to protect the good name of Horatio Lord Nelson, had been present at this theatre last evening, not one of them could have had the ghost of an excuse for calling in question the patriotism of the new play. “The Mariners of England” was, as its honest name implies, a drama after the British sailor’s cheerful and optimistic heart. It began with Dibdin in the orchestra and ended with John Bull, who is credited with the composition known as the National Anthem. The salt sea breezes of Dover and Portsmouth got across the footlights, and at odd times the retentive memory wandered back to the days of “Black-Ey’d Susan” and the nautical enterprises of T. P. Cooke. ___

The Guardian (10 March, 1897 - p.7) A personage bearing the name of “Lord Nelson and Bronte” is the central figure of an exceedingly feeble melodrama by Mr. Robert Buchanan and “Charles Marlowe,” produced this evening at the Olympic Theatre, under the title of “The Mariners of England.” The villain, one regrets to observe, is a captain in the Royal Navy, who, being in the pay of France, makes a plot to murder Nelson. The hero, the long-lost son of an admiral, who is in the meantime serving as a foremast hand, rescues Nelson, but is accused of having been his chief assailant. He is court-martialled on board the Victory, and acquitted, of course, through the intervention of Nelson himself. Then we have the obligatory tableaux of the Battle of Trafalgar and the death of Nelson, which Mr. Abingdon and the limelight man succeeded in rendering melodramatic and ridiculous. As a drama the play is devoid of merit, and the figure of Nelson is introduced without either taste or skill. Mr. Charles Glenny played the hero, and Miss Wakeman the heroine, while Mr. E. M. Robson provided the comic relief. The production was favourably received. ___

The Scotsman (10 March, 1897 - p.9) The fashion for nautical plays continues, and after a short trial in the country a new piece by Mr Robert Buchanan and “Charles Marlowe,” called “The Mariners of England,” was given this evening at the Olympic Theatre. What may be deemed the chief feature of the work is the introduction of the character of Lord Nelson. The play in style is melodrama of the simplest and most ordinary character, in which there is little pretence of novelty. Nelson is not really the principal person, for the hero is a sailor named Harry Dell, who rescues Nelson from some scoundrels who, acting in the pay of the French, attack the great Admiral when on shore in England. However, the villain of the play, in customary fashion, accuses the hero of the crime, and his guilt is immediately assumed by most of the characters, and he is forced to hide; but he surrenders himself for trial, and, after an absurd burlesque of a court-martial, is acquitted. Two effective tableaux are given in the piece; one represents the moment when Nelson was shot at Trafalgar, and the other his death in the cockpit. The piece has been very well mounted, and a good company has been engaged. Graceful work is done by Miss Edith Wakeman, and Miss Edith Bruce acts cleverly in a soubrette part. As chief villain Mr Herbert Sleath played with considerable force, and in good if somewhat rough style the parts of Nelson and the hero were represented by Mr. Abington and Mr Glenny in a fashion that seemed to please the house. ___

The Globe (10 March, 1897 - p.6) “THE MARINERS OF ENGLAND.” Should the feelings of any enthusiastic admirer of Nelson be hurt by the new drama of Mr. Robert Buchanan and “Charles Marlowe” produced yesterday at the Olympic Theatre, “’twere pity of one’s life.” Wholly gratuitous and unbidden is the presence of the great naval hero, and though tableaux of Nelson’s death and the Battle of Trafalgar were introduced into the play, they have only the slightest connection with the story. Two traitorous Englishmen, one of them a captain in the Navy, have a plan, in the interest apparently—though this is not quite plain—of the projected invasion of England by Bonaparte, of kidnapping or murdering the admiral of the fleet, and so perplexing the councils of Government. Their plans are well formed, and go near success. Nelson, since it has to be he, is waylaid during a solitary prowl on the cliffs near Deal, and would have been hurled over the heights but for the opportune arrival of the hero, one Harry Dell, A.B., by whom the rascals are put to rout. Through the treachery of Captain Lebaudy, R.N., Dell is arrested as the assailant of Nelson and not his defender. As the admiral was unconscious at the time, his declaration of his belief in the sailor’s innocence prevails no more with the court-martial than do the supplications of Mabel Talbot, the daughter of an admiral who has stooped to love a man before the mast. Things are going badly with the hero, when the real criminal is brought in to “own up.” Captain Lebaudy, through the intercession of Nelson, is simply dismissed the service, while Black Jack, as the other criminal is generally know, is hanged, like the Gorging Jack and Guzzling Jimmy of Thackeray’s famous ballad. Harry Dell is not quite made, like Little Billee, the captain of a seventy-three, but is appointed at one step a full lieutenant, and put in the way of further promotion. ___

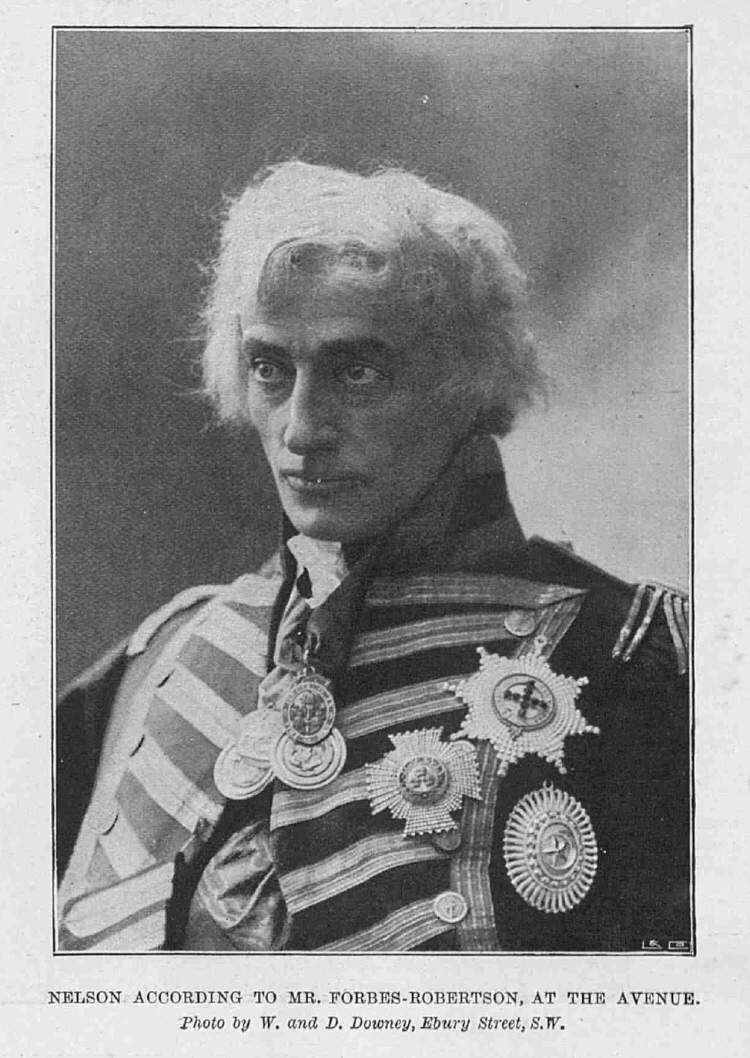

The Times (11 March, 1897 - p.14) OLYMPIC THEATRE. As the hero of Mr. Robert Buchanan and “Charles Marlowe’s” new play, The Mariners of England, it cannot be said that Nelson stands at present in any want of recognition on the stage; for this is his second reincarnation, so to speak, within the few months that have elapsed since the celebration of the Trafalgar anniversary. Nelson No. 2, it may be well to say at once, is as unlike No. 1 as both are probably unlike the original. But as embodied by Mr. Abingdon, No. 2 has this in his favour—that he displays some degree of personal dignity and authority if only in dismissing from the service an unworthy officer who has been conspiring against his admiral’s life. Of the notorious Lady Hamilton who is so much in evidence at the Avenue Theatre there is not a word, save in the historical dying speech which is delivered in the cockpit of the Victory. In fact the new Nelson is rather chary of speech at the best. More than once his entrance upon the scene is the signal for the curtain to come down, and in this respect the authors have done wisely, inasmuch as they leave one’s sense of the hero’s greatness comparatively undisturbed. Perhaps a still better effect would have been produced had the part been designed exclusively as what Mr. Puff would call a “thinking” one, though this would have been hard upon Mr. Abingdon, who really enacts the hero, empty sleeve and all, remarkably well. ___

The Stage (11 March, 1897 - p.12) THE OLYMPIC. On Tuesday evening, March 9, 1897, was produced at this theatre a new and original romantic drama, in four acts and two tableaux, by Robert Buchanan and “Charles Marlowe,” entitled:— The Mariners of England. Lord Nelson and Bronte ... Mr. W. L. Abingdon After a trial trip at Nottingham last week, particulars of which were duly recorded in the last number of THE STAGE by our local correspondent, The Mariners of England, with Horatio, Lord Nelson, as the central figure in the story, has been submitted to a London audience, and successfully so submitted, we make haste to say. No purpose would be served by drawing any comparison between this second of the Nelson plays and that produced a few weeks ago at the Avenue. It will suffice to tell such playgoers as having seen Nelson’s Enchantress, may think that they do not need to see another production on the same theme, that there is no similarity whatever between the two pieces. Even Nelson’s death in the cockpit of the “Victory,” which is the only scene represented in both plays, is differently presented, the death taking place at the Olympic towards the footlights, in full view of the house, whereas, in the Avenue play, it will be remembered, it was represented behind a gauze as in a dream (Lady Hamilton’s). There is a distinct and very welcome salt flavour about The Mariners of England, which will no doubt go far to ensure its success with popular playgoers who enjoy the salt of the sea just as they do the scent of the new-mown hay when it is wafted across the footlights to them. Nor can anybody’s susceptibilities be hurt in this production by the picture drawn by the authors of the greatest of England’s admirals. The good name of Nelson is upheld throughout, for he is presented to us as a man imbued with the idea of his country’s greatness, and, as a consequence, beloved and honoured by his men. Of Lady Hamilton we see nothing; nor, indeed, is any mention made in the course of the drama of the fascination this beautiful woman exercised over England’s naval hero. We hear the name only on the lips of the dying admiral when he says, “Take care of Lady Hamilton.” But, if we have no skeletons unearthed, the play contains, nevertheless, sufficient love interest to satisfy the average playgoer, whose taste, let the advanced psychologists say what they will, still lies in the direction of honest love rather than lawless passion. And the love interest in The Mariners of England is of the kind beloved by the patrons of melodrama, its course temporarily ruffled by the machinations of the villain, who seeks to fasten upon an innocent man a crime of which he knows him to be innocent. There is, perhaps, a little too much of the comic love scenes between Polly Appleyard and Tom Trip, and too little of Lord Nelson himself in Mr. Buchanan’s play. And this will be the more felt by the serious-minded portion of the audience, because the interpretation given of Nelson by Mr. W. L. Abingdon is in every way one of the best conceptions this actor has presented to the stage. Generally associated with villainy, it comes as a relief to see so clever an actor playing in a different vein in the masterly manner he does. The Olympic Nelson is a completely sympathetic character. There is, in turn, gentleness, as well as the tone of command in his voice, besides a happy blend of kindness and dignity, in his manner, according to whether Nelson is engaged in talking to pretty women or merely issuing orders to his men. And this being so, the spectator could well have seen more of Nelson. Mr. Abingdon’s make-up, too, no less than his acting, deserves a word of praise. He has managed to copy the portraits of the great Admiral, the matter even of his armless coat-sleeve being most perfectly arranged. Mr. Charles Glenney is the most manly and loyal of “salts,” besides being a true-hearted lover and staunch supporter of the wronged woman. As the sailor wrongly accused of attempting the life of Lord Nelson—which, as a matter of fact, he is instrumental in saving—Mr. Glenney obtains the full sympathy of the house, and deserves it; whilst execration is as legitimately bestowed upon, and merited by, Mr. Herbert Sleath for his impersonation of the gentlemanly villain, Captain Lebaudy. A villain of a totally different character falls to Mr. Tom Taylor, whose John Marston is an extremely well-thought-out performance. Another cleverly-portrayed character is that of the blind Admiral Talbot, furnished by Mr. Frederick Stanley. Not a very prominent part, perhaps, as the authors wrote it, but it becomes so in the actor’s hands. The Admiral Collingwood of Mr. W. H. Brougham forms also an agreeable adjunct to the picture, the chief characteristic of the impersonation being—and rightly so—dignity; this same quality being likewise contributed by Mr. Geoffrey Weedall and Mr. Adam Alexander, who appear respectively as Admiral White and Captain Hardy. Comic relief is afforded by Mr. E. M. Robson, whose Tom Trip, whether by the seashore, when he talks about Harry Dell, the waif, as his “son,” or in full regimentals on board H.M.S. “Victory,” is a very amusing performance. The smaller parts of Lieutenant Portland, two midshipmen, and others played by Messrs. Ernest Mainwaring, Gilbert Wemys, Cyril Catley, Julius Royston, Charles H. Fenton, George Hareton, and Frank Stribly are all in good hands, the cast generally having been well selected. Despite the number of names on the programme, only three are those of women. But there is none the less a deal of feminine interest in The Mariners of England. Admiral Talbot’s niece, Mabel, and the good-hearted Polly Appleyard furnishing the happy love scenes of the story; whilst disappointment and despair are very befittingly portrayed by Miss Florence Turner, who, as Harry’s foster-sister, Nelly, appeals in turn pleadingly and reproachfully to the villainous Captain Lebaudy to acknowledge her as his wife. The Mabel Talbot of Miss Keith Wakeman is a very pretty picture to gaze upon, for the actress looks quite charming in her high-waisted, clinging dresses. She plays, too, with the requisite grace and abandon, and gives and receives kisses in turn from Lord Nelson and her sweetheart, Harry Dell, in truly delightful fashion. What, however, would make Miss Keith Wakeman’s impersonation more agreeable would be a better control over her voice, the deeper tones of which sometimes prove a little trying to the audience. This slight drawback is partly natural, no doubt, but as we think with care it can be modified, we venture to draw the young actress’s attention to it. The mounting of the play has been very well carried out indeed, the coast scene of the old town of Dover of the first act, no less than the cliffs of the same town in the next act being such as to show the work of the scenic artist at his best. Whilst the exact reproduction of the deck of H.M.S. “Victory” and the place where Nelson fell, will afford huge delight to all who have gone over his historic vessel in Portsmouth Harbour. ___

The Graphic (13 March, 1897) The Theatres BY W. MOY THOMAS IF Nelson’s Enchantress was but a succession of episodes in the private and public life of Nelson, the new Nelson drama with which Mr. Robert Buchanan and his collaborator, “Charles Marlowe,” have furnished the management of the OLYMPIC belongs emphatically to the old school of melodrama which regards a “plot,” as it used to be called, as an indispensable condition. Clearly the authors of The Mariners of England have no faith in the formless play, and look with distrust upon the impressionist method. So, after the good old fashion of Douglas Jerrold, Thomas Dibdin and the late Mr. Pettitt, they have constructed a piece in which virtue and romantic ardour once more contend for four long acts with villainy, subtle daring, and unscrupulous, till in the dramatists’ own good time the wrongdoer is confounded and the hero triumphantly vindicated. They set but little store upon absolute freshness in their materials, as is evident from the fact that their hero, rushing forward to prevent murder, is, through an unhappy combination of circumstances, mistaken for the assassin; for this, it will be remembered, was the cardinal situation in the play called One of the Best, brought out at the ADELPHI a year or two ago; but originality is not looked for in plays of this class. That the authors have set forth a plausible story will hardly be said. It is not easy to conceive a young officer of Nelson’s own ship, and a nephew of a venerable English admiral to boot, conspiring with a scoundrel and spy in the employment of Bonaparte’s Government to stab the hero of the Nile as he is taking a walk by moonlight on the cliffs at Deal, and then cast his body into the sea. Still more difficult to imagine is the notion of making Nelson condone this murderous attack upon himself lest the news of his young officer’s terrible depravity should distress the feelings of the latter’s venerable uncle. Anomalies, however, abound in the OLYMPIC piece, not the least being the free and easy fashion in which the old Admiral’s beautiful niece, Mabel Talbot, gives her heart to Harry Dell, an honest, able-bodied seaman, of the Victory, and spends her time in promenading with him upon the cliffs by moonlight, not to speak of the rustic dances in which the great folk of the neighbourhood and the honest peasantry mingle with a disregard of social distinctions that recalls Mr. Gilbert’s Bab Ballads. Nelson, it will have been perceived, has little to do with all this beyond the fact that he is supposed to be the object of the wicked plot and the murderous attack; but all this furnishes the excuse for an exciting court-martial scene, which has some affinity with the famous episode in Black Ey’d Susan, and prepares the way for the two tableaux of the third act, in one of which Nelson is beheld shot down on the deck of his ship in the moment of his triumph, and in the other is seen dying in the cockpit of the Victory. With all its large admixture of make-believe, however, the new drama appeared to greatly excite and please the first night audience. It is, on the whole, well acted; though Mr. Charles Glenney is hardly sufficiently romantic of aspect for the part of the young man-o’-war’s man, whose high-sounding speeches cast such a spell upon the Admiral’s niece in the comely person of Miss Keith Wakeman. Mr. Abingdon’s Nelson, though hardly so convincing as Mr. Forbes Robertson’s, is a well-studied and highly finished portrait, and other parts are cleverly played by Mr. Herbert Sleath, Mr. E. M. Robson, Miss Florence Tanner, and Miss Edith Bruce. ___

The Athenæum (13 March, 1897 - No. 3620, p.356) DRAMA THE WEEK. COMEDY.—‘The Saucy Sally,’ a Farce in Three Acts. . . . Primitive almost beyond precedent is the melodrama in which Mr. Buchanan and his associate have chosen to enshrine some events, real or fictitious, of the career of Nelson. Every character in the play has been seen before in ‘Black-Eyed Susan’ or other nautical dramas. The piece is intended, however, for a primitive public, and is exactly suited to that at the Olympic. That it would make a strong impression upon a more sophisticated audience is improbable. It is well placed, however, and is in a sense well shaped and well written, and will probably have an enduring success in the country towns for which presumably it is intended. To see Nelson kidnapped or murdered by spies—one of them a naval captain—in the interest of Napoleon, and a plotted invasion, is a bold idea, not, however, very cleverly worked out. The introduction of a mimic battle of Trafalgar, in which Nelson is wounded, and the presentation of the death scene in the cabin of the Victory are concessions to modern taste, and may well help the fortunes of the piece. Abundant absurdities might be pointed out, and the loudly avowed affection of the daughter of an admiral for a common sailor has a distinctly Gilbertian ring. Mr. W. L. Abingdon was well made up as Nelson, and in the less emotional scenes looked the character to the life. In the death scene, where strong facial play was used, the resemblance was lost. Mr. Charles Glenney gave a conventionally powerful rendering of a sailor hero, and Mr. Sleath showed decided talent as the villain. ___

The Era (13 March, 1897) THE OLYMPIC. On Tuesday, March 9th, the Romantic Drama, Lord Nelson and Bronte ... Mr W. L. ABINGDON Mr Robert Buchanan and Miss Harriett Jay in concocting The Mariners of England have done a bold, clever, and ingenious thing. They have simply turned H.M.S. Pinafore back from roguish travestie to sober earnest. In the Olympic piece there is a “common” sailor—“Oh, the irony of the word!”—who loves his admiral’s niece; there is a Dick Deadeye of the most repulsive type; and there is a dénouement similar to that in which the bumboat woman with gipsy blood in her veins confesses that she “mixed the children up, and not a creature knew it.” The expedient adopted by the authors was completely successful, and The Mariners of England was received on Tuesday evening with every symptom of enthusiastic satisfaction. ___

The Illustrated London News (13 March, 1897 - p.4) THE PLAYHOUSES. “THE MARINERS OF ENGLAND,” AT THE OLYMPIC. Admiral Field will be less happy than ever, for while he objected to “Nelson’s Enchantress” as transferring to the stage that emotional background of the great Admiral which is quite historical, “The Mariners of England,” produced at the Olympic on March 9, makes Nelson the victim of a would-be assassin, the patron of a romantic love affair, and the sidelight on a long-lost-heir story, which owe their existence solely to the vivid melodramatic imagination of Mr. Robert Buchanan and “Charles Marlowe” (Miss Harriet Jay). In the town of Dover blind old Admiral Talbot consoled himself for the loss of his son by keeping his niece Mabel (Miss Keith Wakeman) and his nephew Captain Lebaudy (Mr. Herbert Sleath) in his house. He wanted Mabel to marry the Captain, but she preferred a village lad, Harry Dell (Mr. Charles Glenney), who had been rescued from a wreck, and went into the Navy under Nelson. Need it be said that he was Talbot’s son, the fact being suppressed by Lebaudy, who, not content with robbing him of his birthright and his sister—whom he secretly married—wished to destroy his chances of marrying Mabel? Lebaudy, who was in league with France, planned an assassination of Nelson (Mr. W. L. Abingdon), who was staying with old Talbot, on the cliffs at Dover. The Admiral’s life was saved in the nick of time by the appearance of Dell. That hero was arrested as the assassin, and was court-martialled on board the Victory. But the real perpetrator, a man Marston, who had been dismissed from the Navy for espionage, was captured, and Nelson got the whole story out of him, with its crowning implication of Lebaudy, who was cashiered from the service quietly by nelson, eager not to break Talbot’s heart. Here the story proper ends, but no drama about Nelson would be complete without a tableau of his death in the cockpit of the Victory; while no melodrama would go forth without the inevitable act in which the curtain is rung down on explanations, on forgiveness, on vice punished and virtue made happy. So in the fourth act we find Lebaudy dying and confessing, Dell—now raised to the rank of Captain—returning in a white wig and glory, and finding a resting-place in his father’s arms. The play is very workmanlike at many points, even although it is unmistakably a modern melodrama put back into the glorious days of Trafalgar; but it is not dull, and, on the whole, it is very vividly acted. |

|

|

The name of Nelson gives an air of romance to the simple sea-story of Harry Dell, who in the play at the Olympic actually wins the battle of Trafalgar by the indirect process of saving the life of the great Admiral when on shore. Harry, who for many years believed himself to be of humble origin, but was really of good family, had the courage to raise his eyes to the beautiful niece of Admiral Talbot, and the fortune to induce her to lower hers to him favourably. Now, Captain Lebaudy, her cousin, who was anxious to marry her, not only disliked rivalry, but keenly hated the idea of having a common sailor as his rival. Moreover, he was deeply entangled, since, during Harry’s absence at sea, he had wronged Harry’s step-sister under a promise of marriage. |

|

|

From The Theatrical ‘World’ of 1897 by William Archer (London: Walter Scott, Ltd., 1898 - p.81) “THE MARINERS OF ENGLAND.” 17th March. As I can find nothing praiseworthy in the conception, construction, or writing, and nothing noteworthy in the acting, of The Mariners of England, by Mr. Robert Buchanan and “Charles Marlowe,” and as, on the other hand, it is too puerile to call for serious condemnation, I prefer to pass it over in silence. It was cerainly rather painful to see the death of Nelson treated as a limelit scene of vulgar melodrama; but fortunately one had long ago ceased to associate, even in make-believe, the figure on the stage with the name in the playbill. _____

The Mariners of England - continued

|

|

|

|

|

|

|