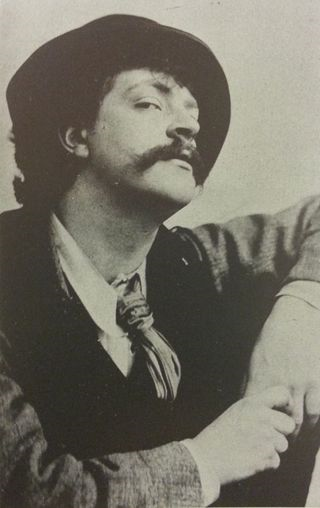

ROBERT WILLIAMS BUCHANAN (1841 - 1901)

|

ROBERT WILLIAMS BUCHANAN (1841 - 1901) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

BUCHANAN’S MUSIC

The Syren. 1870. Composer: Francesco Berger (1834-1933). |

|

|||||||||||||||||||||

|

This is the earliest example I’ve found of Buchanan’s poetry set to music. The Syren (taken from “Undertones”) was published by Lamborn Cock and Co. in 1870 and the following review is from The Musical Times (1 June, 1870): “The Syren. Song. Poetry by Robert Buchanan (from “Undertones”). Music by Francesco Berger. The Syren was reprinted by Messrs. Stanley Lucas, Weber, and Co. in 1886 and The Graphic (24 July, 1886) included this brief mention: “— “The Syren,” a very romantic poem by Robert Buchanan (from “Undertones”), has been set to music of more than ordinary merit by Francesco Berger. It is somewhat difficult to play and sing, but well worth the trouble of studying.” Obituary of Francesco Berger from The Times (27 April, 1933 - p.14): PROFESSOR FRANCESCO BERGER A LINK WITH DICKENS The long life of Francesco Berger, who died on Tuesday at his home at Palmers Green, N., in his ninety-ninth year, was devoted to musical interests, and more particularly to the higher branches of pianoforte teaching, and was illuminated by a close personal friendship with Charles Dickens. During my tenure of office [as conductor] the heat and burden of the day was borne by an honorary secretary (happily still living) of remarkable linguistic accomplishment, much musical experience, and an immense capacity for work—Mr. Francesco Berger. Berger first came into personal touch with Charles Dickens in 1855, having previously, as he expressed it, “worshipped him from afar.” This was just before Dickens purchased Gadshill, and Berger enjoyed 15 years of friendship with him there and elsewhere, being requisitioned to supply music for two plays by Wilkie Collins, which Dickens produced at his famous private theatrical parties, The Lighthouse and The Frozen Deep. In an article of personal recollections of Dickens which Berger contributed to The Times in February, 1928 (the author was then in his ninety-fourth year), he dwelt on Dickens’s power of concentrating his energies on the occupation of the moment, and said:— Whether presiding at a public banquet or reading from one of his books to spell-bound audiences, or acting, or dancing, or brewing punch for his guests at his hospitable table—it was always the entire Dickens (not a portion of him) that was engaged. Berger himself was a man of great energy and power of concentration, but certainly his output of work did not shorten his days, as he suggests may have been the case with Dickens. He was a voluminous and versatile composer of music, though not much of it reached a wide public. His pianoforte music and certain educational works had some importance, notably a pianoforte primer and “Musical Expressions in Four Languages,” as well as certain editions of the classics. Twenty years ago he published “Reminiscences, Impressions, and Anecdotes,” in which he chronicled a life lived among the great figures of the Victorian era and even then well over the average in length. _____

Dreaming. 1874. Composer: Lady Baker (?) Songs by ‘Lady Baker’, including one with words by Robert Buchanan (presumably ‘The Bachelor Dreams’, published in The Argosy (No. 6, May 1866) were reviewed in The Graphic of 23rd May, 1874: ‘MESSRS. KLEIN AND CO.—Ballads or songs may be classified under many heads, and Lady Baker has written for every style. “If” is of the discontented school, as shown by the directions, doloroso and affet (we conclude uoso). Christina Rossetti has supplied the morbid words.—Two songs with vocal and musical meaning are “Missing Thee among the Rye,” the rural words of which are by Sara Leifchild, and “The Old Couple,” for which Lady Baker has written both words and music, as she has done for “Old Memories,” a plaintive ballad which a contralto will do well to take up.—Barry Cornwall has supplied the semi-religious words for “The Mother’s Song,” which will touch many maternal hearts.—“Dreaming,” a well-written song by Robert Buchanan, music by Lady Baker, is a judicious warning to bachelors, who will do well to study it.—“The Mother’s Song Book: Two Part Songs for Little Singers,” has been carefully arranged, and the music composed by Lady Baker under the editorship of G. A. Macfarren. This little work, planned upon the Kindergarten School System, has much to commend it, but the tunes are not catching enough for juvenile singers, very few of whom could be taught to sing the second parts, the harmonies of which are at times difficult enough to puzzle educated elders.’ And also in Lloyds Weekly Newspaper of 7th June, 1874: ‘... Lady Baker is evidently a voluminous composer. We have here six of her songs, exhibiting more or less ability. “Dreaming,” with words by Robert Buchanan, “The Old Couple,” and “Old Memories” are mournful and dirge-like, and might be considered a trifle monotonous. There is much more sprightliness in “If,” a brilliant little song, with words by Christina Rossetti. “Missing Thee among the Rye” is also sparkling and vivacious. “The Mother’s Song” ia an exceedingly pretty setting of some verses by Barry Cornwall.’ I have found no further information about ‘Lady Baker’. There was another composer (noted for her hymns), Amy Susan Baker (1847-1940), who was the daughter of Lieut. Col. George Marryat and became ‘Lady Baker’ on her marriage to Rev. Sir T. H. B. Baker, Bart., of Ranston on 30th December, 1875. However the above reviews predate that, so the other ‘Lady Baker’ remains a mystery. _____

Composer: Theo Marzials (1850-1920). |

|||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||

|

Theo Marzials. composer and poet, provided this song for Buchanan’s 1883 play, Storm-Beaten. It was published by Boosey & Co. in 1883. Two letters from Buchanan to Marzials regarding this commission have survived. According to one of these, Buchanan wanted “simple, telling, music—old English fashion.” The review in The Stage (16 March, 1883) concludes with the following: I have to thank Helen Assaf for providing this information on Marzials and finding the title of his song from Storm-Beaten. _____

Spring Showers. 1884. Composer: Emily Josephine Troup (?-1912). According to her brief entry in wikipedia, Emily Josephine Troup was an English composer of songs and works for piano and violin, and was especially children’s songs. The following item in The Graphic of 19th July, 1884, mentions her setting of a Buchanan poem: “MESSRS. STANLEY LUCAS, WEBER, AND CO.—Half-a-dozen pleasing songs and ballads come from this firm. “Spring Showers,” words by Robert Buchanan, music by Emily J. Troup, is a pretty rustic love ditty for a mezzo- soprano. Of a more ambitious character is “Portuguese Love Song,” music by the above composer, words translated from the Portuguese by José de Vasconcellos, into very creditable English by J. T. Whitehead.” _____

The Wedding of Shon McLean. 1885 (?) Composer: John Liptrot Hatton (1809-1886). |

|||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||

|

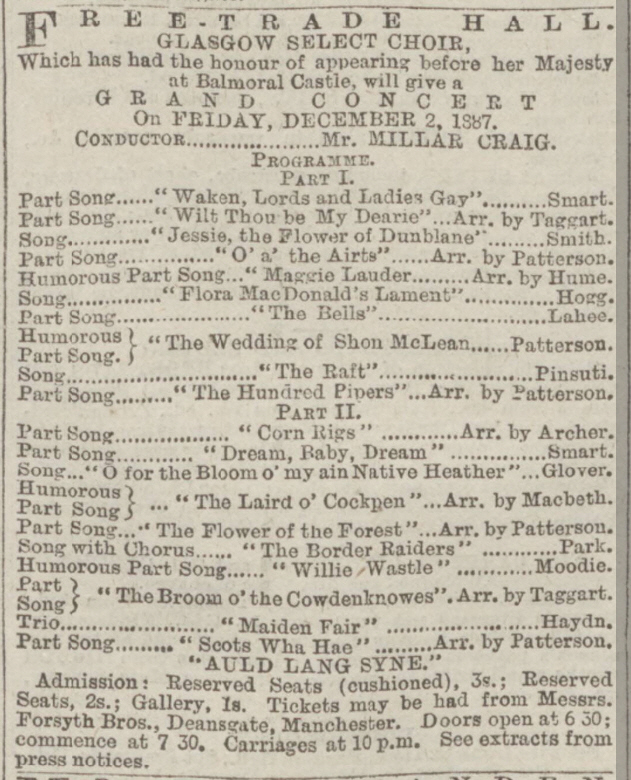

The first of four known musical versions of Buchanan’s ‘The Wedding of Shon McLean’ was written by John Liptrot Hatton. The date of its composition is unknown (the poem was first published in the Gentleman’s Magazine of July, 1874 and was then included in the 1882 collection, Ballads of Life, Love, and Humour) but Hatton’s version is mentioned in a review (from The Exeter and Plymouth Gazette Daily Telegram of 19th January, 1885) of a ‘Scotch Festival’ which took place on 17th January, 1885 at the Victoria Hall, Exeter: ‘... Mr. Gilbert Campbell has a powerful, vigorous and flexible bass voice, the nationality of which enabled him to give “The Hundred Pipers” with distinctive effect, and “Willie brew’d a peck o’ Maut” in a manner which elicited hearty applause; but it was in “The Wedding of Shon McLean” (composed by J. L. Hatton, in his own characteristic style, the words being taken from the poem by Robert Buchanan) that Mr. Campbell found his most successful and popular theme.’ According to a review in The Leeds Mercury of 23rd January, 1885, the song also featured in a concert by the Glasgow Select Choir at Leeds Town Hall, and it continued to be performed for several years. |

|||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||

|

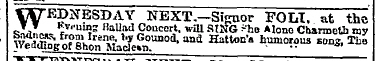

[Advert from The Times (1 December, 1890).] |

|||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||

|

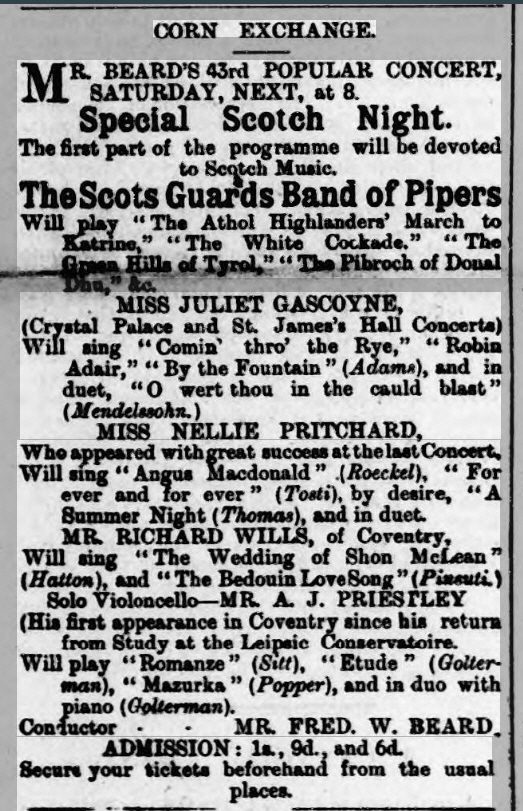

[Advert from The Coventry Herald (30 October, 1891).] _____

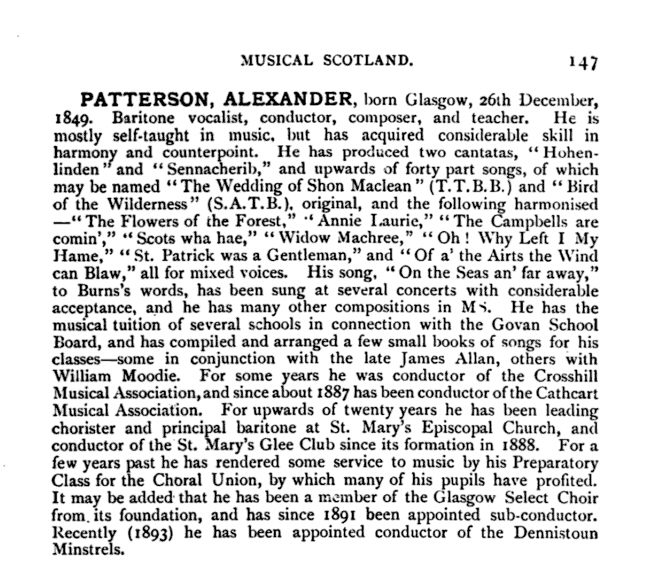

The Wedding of Shon McLean. 1887 (?) Composer: Alexander Patterson (1849-?). The second version of ‘The Wedding of Shon McLean’ was written by Alexander Patterson. The following information is taken from Musical Scotland: Past and Present by David Baptie (Hildesheim, New York: Georg Olms Verlag, 1972): |

|||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||

|

A review of a Scottish Concert by the Glasgow Select Choir in The Leeds Mercury of 29 November, 1887 contains the following: ‘... There is the less need to wonder at the fine quality of the ensemble singing, when the quality of the separate voices is heard displayed in solos or duets, or when it is learned that among the members are to be found musicians of such ability as Mr. Patterson, the arranger of the two part-songs above named—“Annie Laurie” and “The Flowers of the Forest”—and many others sung by the choir. |

|||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||

|

[Advert from The Manchester Courier and Lancashire General Advertiser (26 November, 1887).]

Alex Patterson’s version was also part of the repertoire of the Bristol Æolian Male Choir, according to this review of a concert at the Y.M.C.A. from The Western Daily Press (Bristol) of 11th December, 1902: ‘... The humour displayed in Alex. Patterson’s setting of Robert Buchanan’s quaint ballad, “The Wedding of Shon Maclean,” was well brought out, and an attempt made to have the piece repeated, but without success.’ _____

The New Covenant. 1888. Composer: Sir Alexander Campbell Mackenzie (1847-1935). |

|||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||

|

The following biography of Sir Alexander Campbell Mackenzie is taken from the fifth edition of The Oxford Companion To Music (1944): “ALEXANDER CAMPBELL MACKENZIE. Further information about Sir Alexander Campbell Mackenzie is available on the Musicweb International site and the Hyperion site has details of current recordings of his violin and piano concertos and a selection of his orchestral works. The Who Was Who in the D’Oyly Carte Opera Company site lists Mackenzie’s operas: Columba (1883), The Troubador (1886), His Majesty (1897), The Cricket on the Hearth (1914) and The Eve of St. John (1925). It also says that “Sir Alexander Campbell Mackenzie was widely recognized as the greatest Scottish composer of his day.” He is also one of the composers featured in Charles Willeby’s book Masters of English Music (London: James R. Osgood, McIlvaine & Co., 1896) which is available at the Internet Archive. Mackenzie collaborated with Robert Buchanan on several occasions. In 1888, Buchanan and Mackenzie were commissioned to write an ode for the opening ceremony of the Glasgow International Exhibition. Buchanan’s words, and a description of Mackenzie’s music, are available below: The score of The New Covenant, Op. 38 (for chorus and piano) was published by Novello, Ewer and Co. in 1888. Mackenzie also provided some of the music for Buchanan’s play, The Bride of Love which was performed at the Adelphi and Lyric theatres in London in 1890 and he also wrote the overture and incidental music for Buchanan’s stage adaptation of Sir Walter Scott’s Marmion, which was produced at the Theatre Royal, Glasgow and the Royal Lyceum Theatre, Edinburgh in 1891. The songs from Marmion were published and were reviewed in the Glasgow Herald (15/5/1891): “ Messrs Novello, Ewer & Co., London, send us Dr Mackenzie’s “Marmion” songs, “Where shall the lover rest?” and “Young Lochinvar.” The melodies are distinctive, the first having a certain dramatic significance in its stage setting, of which it is, of course, divested in the drawing-room. They are not easy to sing.” Mackenzie’s memoirs, A Musician’s Narrative, were published by Cassell, London, in 1927. _____

Composer: W. Augustus Barratt (1873-1947) I have not found a copy of this song, but I assume it is a setting of the Buchanan poem of the same name published in The New Rome in 1898. The song was included in the Proms concerts of 1901 and 1902. More information about Barratt’s varied career is available on wikipedia. |

|||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

[Advert from The Daily Telegraph (10 July, 1903 - p.1).] _____

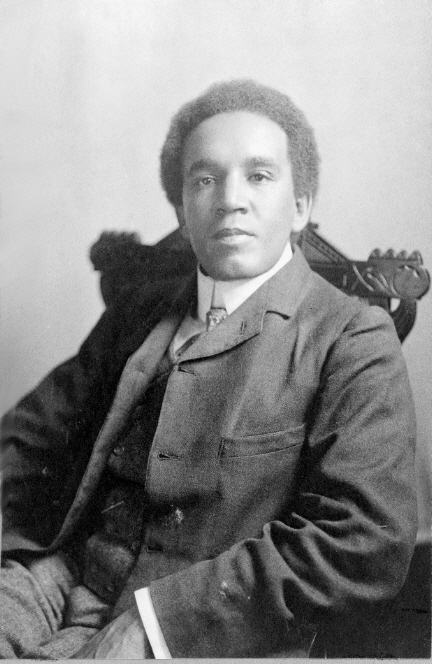

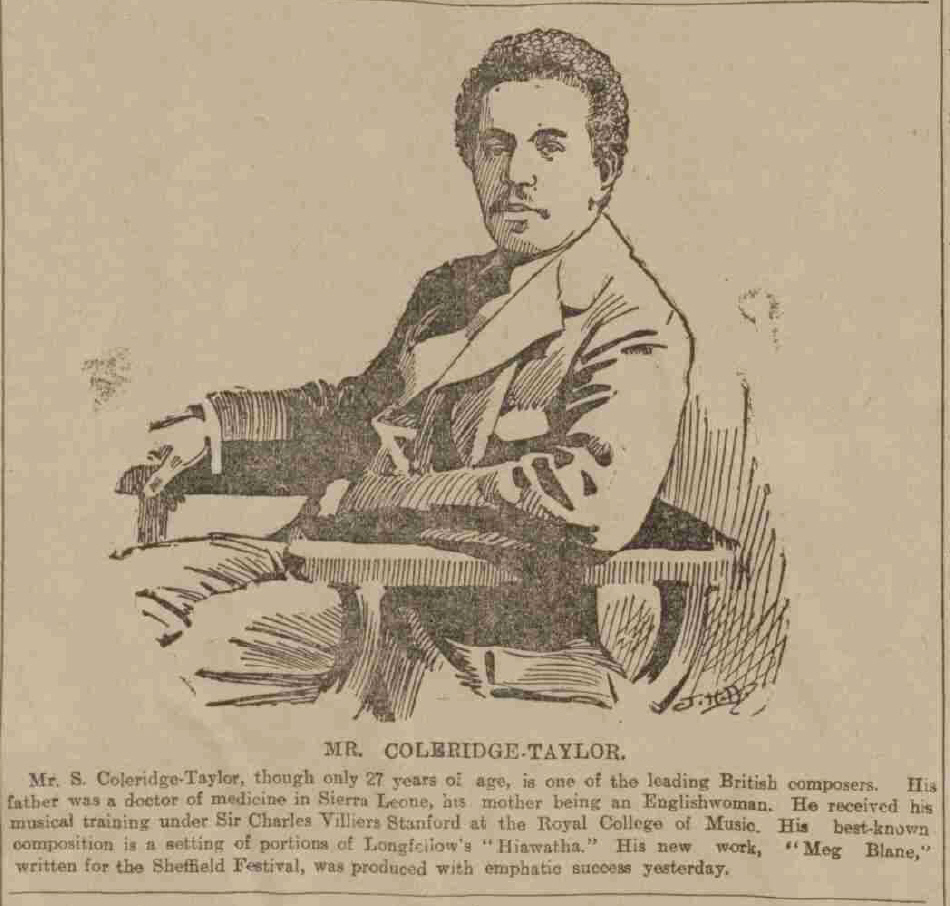

Meg Blane, a rhapsody of the sea. Op. 48. 1902. Composer: Samuel Coleridge-Taylor (1875-1912). |

|||

|

|||

|

There is plenty of information available about Samuel Coleridge-Taylor, from a brief biography on the 100 Great Black Britons website, which hints at the difficulties he must have encountered to achieve his position as Britain's foremost black composer of classical music, a more detailed biography on AfriClassical.com (African Heritage in Classical Music), to the Samuel Coleridge-Taylor Foundation. ‘Meg Blane’, his cantata based on Buchanan’s poem, was premiered in Sheffield on Friday, October 3rd, 1902. The Sheffield Daily Independent previewed the work on 23rd September: ‘SHEFFIELD MUSIC FESTIVAL. The New Works. Mr. Coleridge-Taylor’s “Meg Blane.” The second novelty of next week’s Sheffield Festival is Mr. Samuel Coleridge-Taylor’s hitherto unheard “Meg Blane.” Dr. Coward’s cantata “Gareth and Linet” was noticed in Saturday’s issue. The first performance of ‘Meg Blane’ took place during the morning concert on the third day of the 1902 Sheffield Music Festival at the city’s Albert Hall. The concert opened with Dvorak’s ‘Stabat Mater’, followed by Bach’s ‘Jesu, Priceless Treasure’, then after the interval, ‘Meg Blane’, conducted by Samuel Coleridge-Taylor. The review of the day’s concerts in The Sheffield Daily Independent of 4th October, is available here, but the following extracts relate to ‘Meg Blane’: ‘After the interval came “Meg Blane,” Mr. Coleridge-Taylor’s original production for the Sheffield Festival, and conducted by the swarthy composer himself. This short, vigorous work had a great success. It proved to be simple and comprehensible for all. Mr. Buchanan’s poem, which forms the libretto, might have been written with a view to musical interpretation, so perfectly adapted is it to the requirements of the descriptive composer. “Meg Blane” takes its title from the name of a fearless woman who plays the part of Grace Darling, but with tragic ineffectiveness, and the poem and the music describe the storm at sea, the terror of the situation of the shipwrecked mariners, and the despair at the failure of Meg Blane’s attempt to rescue them. The narrative is shared by a soloist and the chorus, and “Meg Blane” introduced in the former capacity a new Festival principal singer in Madame Kirkby Lunn, a singularly powerful mezzo-soprano. Madame Lunn has been previously heard in Sheffield in grand opera.’ The paper’s music critic dealt with the piece in more detail, reprinting the description from the September preview, with these additions: ‘Coleridge-Taylor’s “Meg Blane.” Mr. Coleridge-Taylor’s rhapsody of the sea, “Meg Blane,” will be remembered as one of the most pleasing and effective compositions submitted at the 1902 Festival. And from the ‘Festival Asides’ section: ‘Mr. Samuel Coleridge-Taylor had to hasten to London immediately after the remarkably fine rendering of his “Meg Blane.” He regarded the whole achievement as excellent, especially the singing of the epilogue. The chorus, he added, had the whole run of the work, and threw into it that emotion which could be expected from a soloist but never anticipated from a choir. He was immensely pleased, and had never been more delighted with the rendering of any of his compositions. “Say what you will in the way of eulogy,” added Mr. Coleridge-Taylor, as he left for the railway station, “and I will endorse it.”’ The Sheffield Daily Telegraph of 4th October was also full of praise for ‘Meg Blane’. The following editorial gave a little more prominence to the part played by Robert Buchanan: ‘Our musical representatives have dealt so fully, and with such evident pleasure in their work, with all that has been produced day by day and night by night, during the Sheffield Musical Festival, that no running comment or summing-up is needed. The Festival had exceptional features, and each music-lover will give pride of place to what stirs him most. There is no need to censure the theology of “The Dream of Gerontius,” any more than to question the counsels of Confucius because we like not the creed of his kind, or sit in solemn judgment over any of the Western world’s outworn dogmas. One can read and be wiser by the reading of Dante, though he has a deal to say about that place which is “never mentioned to ears polite.” Men do not rail at Gustave Dore though they refuse to accept his conception of poor sinners being stuck, head downwards, in separate places of fiery torture. They may not believe in a personal enemy of mankind at all, and yet be able to rejoice in the genius which gives Dore’s art, just as we rejoice in the genius which gives us such music as thrills us in “The Dream of Gerontius.” Music is not narrowed by man or this earth-house he lives in. It will survive both. Hence Carlyle’s definition of it as “a kind of inarticulate unfathomable speech, which leads us to the edge of the infinite, and lets us for moments gaze into that.” O God! it was a sight that made the hair turn white, The main review of the Festival (available here) included this section on ‘Meg Blane’: |

|||

|

|

‘With Mr. Coleridge-Taylor’s orchestral and choral rhapsody, “Meg Blane,” which was the first item after the luncheon interval, the Sheffield Festival made history. If for no other reason than that it was the birthplace of a very clever and beautiful work, the meeting of 1902 will become memorable. The concert was also reviewed on 4th October in The Yorkshire Post: ‘Now Sheffield, in its young enthusiasm, has provided a programme which is most interesting and artistic, but errs, it seems to me, in giving more exacting work to the chorus than flesh and blood can stand. This morning they sang Dvorak’s “Stabat Mater,” and, as if an hour and a half’s music of this kind were not sufficient for the first part of the concert, they added to it a Bach motet taking just half-an-hour in performance. They sang Dvorak to perfection, though once or twice it was just possible to detect traces of fatigue, which became very apparent in the five-part motet, “Jesu, Priceless Treasure.” The voices lost their clear ring, and the organ—luckily an instrument of exceptionally refined and sympathetic quality, had to be used freely to keep them up to the pitch. This was the more tantalising, since it was evident they could, under favourably conditions, sing the music quite perfectly, with the utmost vocal charm and the exactest precision. But it was nothing short of gross cruelty to choralists who had been singing “Israel in Egypt” up to close upon eleven o’clock on the preceding night, and, I am told, had had a special rehearsal only just before the morning concert, to give them this additional task, which made their singing seem obviously laboured. And after the interval they had to return and sing Mr. Coleridge Taylor’s new work, which is chiefly choral! And The Times: ‘At the beginning of the second part of the concert came a new work of some importance. Mr. Coleridge-Taylor has become in a very few years a figure of prominence in the English musical world, and each new work from his pen is the more anxiously expected for the very reason that of late his productions have been remarkably unequal. It is satisfactory to be able to say that his setting of Robert Buchanan’s Meg Blane is one of the best things he has done; if it is not another Hiawatha’s Wedding Feast it is at least a good deal better than the last section of his Longfellow trilogy, and a vast improvement on the work he contributed to the Leeds Festival of last year. The story of an unsuccessful Grace Darling’s exploit is set forth with much conviction and artistic skill, for mezzo soprano solo and chorus. The soloist is identified at certain points with Meg Blane, who attempts to row to the rescue of some shipwrecked men, but the main opportunities for the single voice are in a prologue and epilogue set to the same words. The declamatory opening is very well imagined, and at the repetition great variety is brought about by allowing a choir of eight parts to answer the soloist’s words. A phrase which obviously stands for the idea of intercession is developed and transformed in various ways with very decided skill, and the choral writing, as well as the orchestral, is vigorous and original. The composer, who conducted, was twice recalled and enthusiastically applauded.’ Also, this from The Referee of 5th October: ‘Mr. Coleridge Taylor’s “Rhapsody of the Sea,” with the late Robert Buchanan’s poem, “Meg Blane,” for its text, is the strongest work the Anglo-African composer has given us since his “Song of Hiawatha.” The spirit of the lines has been admirably caught. The inexorable power of the sea, its fury and its swirl, the gleam of the moon on the sinking wreck, the efforts of the gallant rescuers with Meg Blane at the helm, the final catastrophe brought about by the towering, crag-like, crested wave, and, permeating the whole, the constant strain of supplicatory prayer, are allied to strains which intensify the picture drawn by the poet.’ I also came across a mention of a more recent performance on the Chandos Forum: “How I wish there was a recording of Samuel Coleridge-Taylor’s cantata “MEG BLANE” - a “Rhapsody of the Sea” - (written in 1902) for mezzo-soprano, chorus & orchestra. We heard this work performed at Eton College a few years ago, by the Windsor Sinfonia with the Broadheath Singers, conducted by Robert Tucker. A very atmospheric work that definitely needs to be recorded. I think it was about 35 minutes in length.” The Hyperion site has the sleevenotes to their CD of Coleridge-Taylor's Violin Concerto and the following passage caught my eye - it seemed appropriate to quote it here considering Buchanan's opinion of publishers: “A week after the Crystal Palace performance Coleridge-Taylor’s standing was established for all time with English audiences when Stanford conducted the first performance of Hiawatha’s Wedding Feast at the RCM. The press reception was huge, and within two years he had produced two further parts of Hiawatha; one of the early performances of the complete score came at the 1900 Birmingham Festival when he had a standing ovation, in contrast to the mixed reception accorded Elgar’s The Dream of Gerontius which had its imperfect first performance at the same festival. Unfortunately, hard up, he sold the copyright of Hiawatha’s Wedding Feast to his publisher outright, for £15, unaware that he had written what was to be the most popular British choral work of its day. The vocal score sold over 140,000 copies before the First World War, and it was performed repeatedly by every choral society in the country. If only he had taken a royalty he could have lived in comfort. As it was he was scratching around for a living all his life.” The score of ‘Meg Blane, a rhapsody of the sea. Op. 48’ is available at the Internet Archive. Coleridge-Taylor also set the following poems of Buchanan to music: Part-songs, op. 73a, for men’s voices (TTBB), 1909, included ‘O mariners, out of the sunlight’ and ‘O who will worship the great god Pan?’ Published by J. Curwen & Sons in 1910. And Love is Like the Roses (a song for low voice and piano) was published by Arthur P. Schmidt in 1918. In 2008 a biography of Coleridge-Taylor, Black Mahler by Charles Elford, was published by Grosvenor House. There’s a website for the book which includes much more information about this truly fascinating composer. |

|

|

The Wedding of Shon Maclean, a Scottish rhapsody. 1909. Composer: Hubert Bath (1883-1945). |

|

|

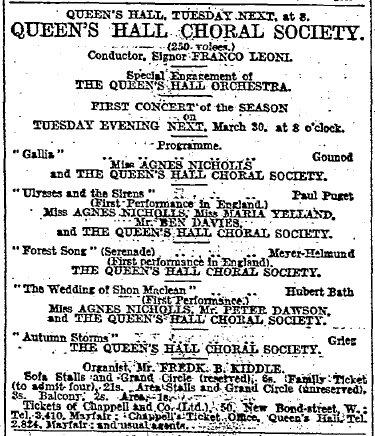

The fifth edition of The Oxford Companion To Music (1944) gives the following brief biography of Hubert Bath: “Born at Barnstaple in 1883. He has written stage and other music, chiefly of the somewhat lighter kind, and has served as musical adviser to the London County Council, directing the organization of its park bands.” A more detailed biography of Hubert Bath is provided by Philip L. Scowcroft in his essay, ‘A First Garland of British Light Music Composers’ on the Musicweb site. Bath’s output included orchestral suites, cantatas, military marches and other works for brass band (including ‘Out of the Blue’ which, for many years was the signature tune of BBC Radio’s Sports Report), but he was also one of the pioneers of film music in Britain. He is perhaps best known for ‘The Cornish Rhapsody’ which he composed for the film Love Story (1944) and which is available on CD compilations of similar film favourites like 'The Warsaw Concerto'. As well as providing some of the music for the first British 'talkie', Hitchcock's Blackmail (1929), he also contributed to the score of Hitchcock’s 1935 version of The 39 Steps. Much of his work was uncredited but a list of the films he worked on is available on imdb. He was working on the score for The Wicked Lady when he died at Harefield, Middlesex on 24 April 1945. The Wedding of Shon McLean ‘A Scottish Rhapsody for Chorus, Soprano and Baritone soloists and Orchestra’ was first performed at the Queen’s Hall, London on Tuesday, 30th March, 1909. |

|

|

[Advert from The Times (24 March, 1909 - p.1).]

The Aberdeen Daily Journal of 31st March, 1909 carried this review from their London correspondent: “Choral societies in London are not so many as to make an addition to their number superfluous. To-night, an entirely new body of singers, formed by Messrs Chappell and called the Queen’s Hall Choral Society, made its first appearance. It is generally said that, owing to the restrictions of their dialect, Londoners cannot sing and have poor voices. That may be, but nevertheless the 250 singers constituting the new choir were able to pour out a fine volume of tone. In choral technique—the points of attack, release, and general blend—the choir has yet something to learn; but the conductor, Signor Franco Leoni, whose methods are not free from a certain Southern impetuousness, seemed more bent on drawing out the tone of his choir than on paying attention to the points which make the real value of choral effort. Two new works were brought forward for the occasion. One was a setting by Mr Hubert Bath of Robert Buchanan’s characteristic ballad “The Wedding of Shon Maclean,” and the other came from France in the form of a dramatic cantata on the subject of “Ulysses and the Sirens,” composed by M. Paul Puget. Mr Bath supplies a specimen of choral writing that is likely to be popular. His conception of what forms Scottish character in music belongs to Cockaigne rather than to Caledonia, and his humour is sometimes obvious and cheap, but this is the best thing he has yet done in the way of extensive composition, and well indicates where his powers lie. ...” And the London correspondent of The Yorkshire Post (31/3/1909), described the piece thus: “The most memorable event of the evening was the first production of a setting by Mr. Herbert Bath of Robert Buchanan’s poem, ‘The Wedding of Shon MacLean,’ which has all the elements of popularity. Mr. Bath is a native of Barnstaple, where he was born in 1883. Although so young he has composed a considerable number of works which testify to freshness of thought, originality of ideas, and musicianly skill. His setting of Buchanan’s poem is masterly in its perception of humour, appropriateness of manner, and scoring. Moreover, the music is instinct with life, and this seemed to be felt by the choristers, who entered into its spirit with the greatest zest. Several times a ripple of laughter ran through Queen’s Hall at the aptness with which the music emphasised the mock gravity of the situation. The refrain is allied to a melody that once heard is hard to forget, and was hummed by many as they left the hall. Over the whole there is pleasantly cast an artistic atmosphere that excites esteem, and there can be little doubt that it will delight a large number of choral societies and their audiences. It contains short solos for soprano and baritone, and these parts were admirably rendered by Madame Agnes Nicholls and Mr. Peter Dawson. The composer conducted, and at the close the applause was enthusiastic.” A performance by the Queen’s Hall Choral Society later in the year elicited this review from The Times (3 November, 1909 - p.12): “Mr. Hubert Bath’s clever and humorous “Wedding of Shon Maclean,” with Miss Teyte and Mr. Bates in the solo parts, was repeated with success, the various “Scotch” effects, such as the “snap” and the orchestral imitation of bagpipes, being greatly appreciated. The Queen’s Hall orchestra played the accompaniments and occasionally looked at the conductor.” The piece was performed at the Leeds Music Festival in October, 1910, and this was also reviewed in The Times (15 October, 1910 - p.10): “The other choral work with which the concert closed is not very well fitted to a large festival like Leeds. Mr. Hubert Bath’s “The Wedding of Shon Maclean” is a great success with a certain class of choral societies, and those who are amused with the cockney representation of Scotsmen on the stage are sure to enjoy its many humours; but with a large chorus and in the conditions which are present at our great festivals the jokes are apt to seem commonplace and thin. The composer conducted,and Miss Perceval Allen and Mr. Kennerley Rumford sang the solo parts as well as they could be sung. The favourable reception of the work was no doubt partly due to the musical cleverness and the adroit weaving together of themes, but also to the excellent performance.” Published by Chappell & Co. in 1909, the score is available to download from IMSLP. ___

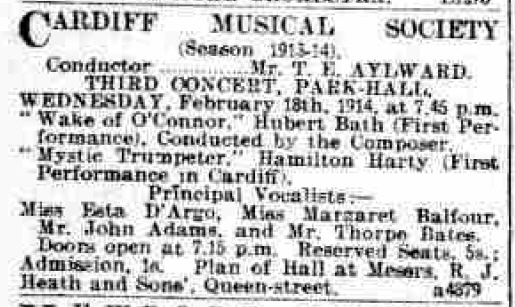

The Wake of O’Connor - ‘An Irish Rhapsody’, was written in 1913 and is a 30 minute piece for soprano, alto, tenor and bass soloists, choir, timpani, percussion, organ and strings. It received its first performance in Cardiff on 18th February, 1914. |

|

|

[Advert from the Western Mail (7 February, 1914 - p.6).]

The concert was reviewed in the Western Mail on 19th February: ‘WAKE OF O’CONNOR MR. HUBERT BATH’S NEW WORK. PRODUCED AT CARDIFF. COMPOSER’S TRIBUTE TO FINE CHORUS. By ORPHEUS. Cardiff Musical Society, which has set an example the rest of Wales might well emulate in the selection of modern compositions, had the honour on Wednesday of producing a new work by Mr. Hubert Bath, a rising young British composer—a work which is destined to become more popular than any of his previous efforts. FRIVOLITY, PATHOS, AND MYSTICISM. In his setting of Robert Buchanan’s poem as an Irish rhapsody for a full quartette of soloists, chorus, and orchestra Mr. Hubert Bath shows a distinct advance in many respects on “The Wedding of Shon Maclean,” (a work previously performed by the society) which gained for him considerable popularity throughout the country, and raised him to the ranks of the rising British composers. It is equally distinctive in modern characterisation, and reflects as well, if not better, the vitality and breezy humour of the composer’s individuality; but Buchanan’s words, with their quaint mixture of frivolity, pathos, and Celtic mysticism, demand more versatile treatment, and it is in the happy manner in which he blends these opposite qualities that Mr. Bath shows the most decided advance. Each of these distinctive moods, intermixed as the poem suggests, is strongly typified. FINE SINGING. Throughout the choral writing is grateful both to singers and listeners, and the chorus fully entered into the spirit of the work. The humorous passages were sung with delightful vigour and crispness, and much delicacy of treatment distinguished the contrasting phases of the poem. Much of the narrative portion is allotted to a quartette of soloists, and there are some passages of striking beauty, to which effective humming accompaniments are supplied by the chorus. TRIBUTE TO CHORUS. In a few well-chosen words of acknowledgment Mr. Bath congratulated Cardiff on having such a fine chorus, and expressed himself as being delighted with the performance. He also paid a high tribute to the thorough and efficient work of Mr. Aylward. Published by Novello & Co. in 1913, the score is available to download from IMSLP. _____

The Wedding of Shon McLean. 1910. Composer: John Duffell (?) A fourth, perhaps final, ‘Shon McLean’. No information (of the piece or the composer) beyond this concert review from The Sheffield Daily Telegraph of 21st March, 1910: ‘Concert in the Wicker. A concert by the members of the newly-formed singing party, conducted by Mr. John Parr, was given in the schoolroom of Holy Trinity Church, Wicker, on Saturday evening, to a moderate but appreciative audience. Some part-songs were well rendered, and the following members contributed solos:—Misses Jessie Stenton, Doris Jackson, Alice Harrison, Grace Cawley, E. Dickman, Ruth Laver, Caroline Lickiss, Beatrice Jones, and Messrs. John Parr and James Croll. Miss Nellie Stenton played a violin solo, and Mr. John Parr a bassoon solo. _____

|

|

|

|

|

|

|