|

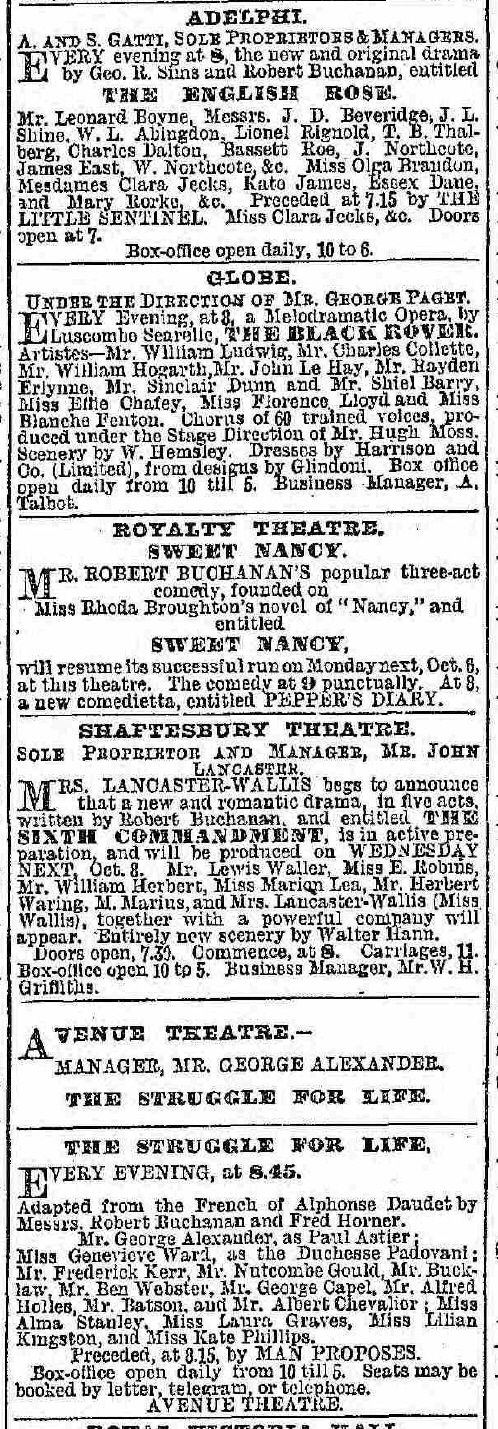

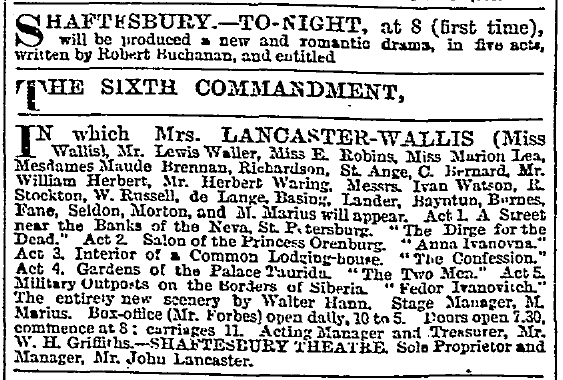

[Advert for The Sixth Commandment from The Times (8 October, 1890).]

The Times (9 October, 1890 - p.9)

SHAFTESBURY THEATRE.

There seems to be a fatality connected with plays of Russian life; they are pervaded by a deadly dulness. Mr. Robert Buchanan’s new play, or rather adaptation, being on a Russian subject, is not exception to the rule. It is in five acts; it lasts from 8 o’clock till close upon midnight; it is peopled by the conventional characters who have so often done duty on the boards in this connexion—the reckless young Socialist, the chief of police, the quasi-official personage in variably addressed as “Excellency,” the travelling Englishman, who is storing his note-book with facts as to “Savage Russia,” and after a succession of gloomy and far-fetched incidents we come to the inevitable scene in the wilds of Siberia, with its trains of prisoners toiling along under the whip of the overseer. All this has been seen many times before, we might say ad nauseam, for the Russian drama has almost become a by-word on the stage. Mr. Robert Buchanan has been attracted to the subject by Doskoievsky’s novel “Crime and Punishment,” and upon this The Sixth Commandment, as the new play is named, is in a great measure founded. But the fact remains that, despite the freshness of his inspiration, he deals with a set of characters and a class of incidents which experience has shown to be dramatically unprofitable. Hence the undisguised discontent of the first night public with the new play. A sense of weariness set in early, steadily increased, and culminated in something like active hostility when, at the fall of the curtain, the author indiscreetly accepted a call. Mr. Robert Buchanan affixes to the playbill his usual “Author’s Note.” Let us rather have in such cases as this an “Author’s Apology.” Whatever the theme or its treatment, no play can be regarded as a source of unmixed pleasure when it drags its weary course over a period of nearly four hours, and condemns those who would see the dénouement to miss their last trains and omnibuses.

The tone of Russian fiction is depressing, and, in this respect, Mr. Robert Buchanan has fully caught the spirit of his author. The Sixth Commandment is a story of crime and expiation. While Fedor Ivanovitch, the young Socialist, sees his sweetheart, with her mother, steeped to the lips in poverty and insulted by the overtures of the wealthy profligate, Prince Zosimoff, a money lender crosses his path with taunting and bitter words on his tongue. In a paroxysm of rage he strangles this miserable creature, a character, by the way, cleverly embodied by Mr. de Lange, and all too soon disposed of. Instantly he is overwhelmed with remorse, and, to add to his distress of mind, he finds himself, by the death of a relative, raised to a position of affluence and social consideration. To his sweetheart he returns with wealth in his hand, only to find that she has meanwhile yielded to the tempter, and his disgust with the world is further increased by the discovery that some wretched, poverty-stricken being, tired of life, has given himself up to the police as the perpetrator of the murder. This being so, it is not surprising to find that Fedor Ivanovitch makes a confession of his crime under circumstances which, if they do not immediately lead to his arrest, place him at all events in the power of his enemy, Prince Zosimoff, and that this heartless, selfish profligate, a fine specimen of what M. Daudet calls the “struggle-for- lifeur,” turns the fact to account by coercing Fedor’s sister into giving him her hand. There is here a considerable amount of dramatic suggestion. Unfortunately, it is not of an interesting, still less of an enlivening, kind, and what, perhaps, is still more fatal, the only possible solution to the dramatic problem so raised is not of a character to stir the public sympathy. Fedor Ivanovitch is sent to Siberia, and with him, on one pretext or another, go all the principal dramatis personæ. Thanks to this circumstance, Prince Zosimoff, still pursuing his evil courses, falls into Fedor Ivanovitch’s power. The young man could kill him like a dog, but he refrains; he feels that he has still to expiate his crime. Not of this opinion, however, are the authorities of St. Petersburg, for an unconditional pardon is sent to him, while by the same turn of fortune’s wheel his arch enemy is laid by the heels. At least a story of this cast ought to point some moral, but The Sixth Commandment has none, unless it be that murder is sometimes to be condoned. It would be difficult to name a more unsatisfactory piece of work than this play from any point of view, whether moral or practical. Mr. Lewis Waller enacts the sombre-minded and somewhat enigmatical hero with much point and vigour, and he has sympathetic associates in Mrs. Lancaster-Wallis as the sister and Miss E. Robins as the sweetheart, both victims of Prince Zosimoff’s unbridled passions. This last-named personage is rendered with the necessary degree of gentlemanly brutality by Mr. Herbert Waring, while M. Marius is the indispensable chief of police. No acting, however, could save the play from its all- pervading air of unreality and melodramatic bombast; and the new management of this theatre will doubtless find it to their advantage to change the bill as soon as may be.

___

The Morning Post (9 October, 1890)

SHAFTESBURY THEATRE.

_____

Mr. Robert Buchanan is a prolific dramatic author, and he is as bold and unconventional as he is industrious. Probably he is the only writer for the stage at the present day who would have chosen “The Sixth Commandment” as the title and the subject of his new play, in five acts, produced for the first time last night by Mrs. Lancaster-Wallis, who, now Mr. Willard’s term has expired, returns to her own theatre to take the management and to appear as a prominent personage in Mr. Buchanan’s drama. It is a story of Russian life, the action taking place in St. Petersburg and Siberia. The author has, in dealing with Russian scenes, not chosen a Nihilist plot as the groundwork, and for that we are grateful. Something too much has been made of Nihilism on the modern stage, and but for the local colour introduced and the names of the characters the plot might have been laid in another country. But there are some features distinctively Russian in the story, and these Mr. Buchanan has used for dramatic purposes with some effect. The play opens in a street on the banks of the Neva. Other scenes of high and low life are introduced in St. Petersburg, and then the action is transferred to Siberia. The story relates to a murder committed by a young nobleman of St. Petersburg, and the incidents resulting therefrom show in what manner the crime is brought to light, while the pathetic portion is that in which the high-born murderer makes what atonement he can for his offence. We find him in the opening scene a student in St. Petersburg. He is in distress and in love, and he learns that the young girl he loves has been lured from her home by a titled libertine, Prince Zosimoff. She has gone to the prince’s palace in the hope of gaining money for her mother, the wife of a drunken drosky-driver. The student, driven to despair, seeks to induce a money-lender to advance a small sum upon his sister’s miniature. In doing so he learns that the wretch is in the pay of the Prince, and in a fit of mad passion he clutches the usurer by the throat with such violence that he is strangled. A moment after his friend brings him news of the death of a wealthy relative, and he flies frantically from the scene a rich and titled man, but a murderer. In the second act Fedor, the student, is seen in the house of Prince Zosimoff, where he learns that a man has been arrested for the murder, and in a conversation with the Chief of Police Fedor tells of a theory he has respecting the crime. The police official laughs at him, but the Prince is more acute. He at once suspects Fedor to be the murderer, and, having formerly loved his sister, he informs her of his views, and promises to save her brother if she will marry him. In the third act there is a double scene, where the Prince, in company with Anna, overhears Fedor confess to his old sweetheart that he was really guilty of the crime. Poor Liza had already told him how she had been betrayed by the Prince. It was a painful but undoubtedly a powerful situation, and it aroused the audience to enthusiasm. The hero exclaims, “There is dust and ashes on your head, and blood on mine,” and the climax of stage despair seemed to have been reached. Anna consents to accept the Prince to save her brother, but he confesses his guilt rather than an innocent man should suffer, and is sent to Siberia. His heroism in rescuing some miners causes him to be pardoned by the Czar, and the lovers are reunited. The story is strong in one or two situations, but the drama, as a whole, is overweighted with misery, horror, and gloom. Before the close it had become repellant to the audience, and the final verdict was unfavourable. Mrs. Lancaster-Wallis played Anna with great earnestness and pathos, especially in the scene where the unhappy girl hears her brother’s confession. Again, in her refusal of the Prince, the actress was dignified and impressive. Miss Marion Lea appeared as Sophia, a pretty, capricious girl, in love with an Englishman. Miss Lea, by her bright and animated action, imparted the few gleams of gaiety that shone upon the sombre drama. Miss Elizabeth Robins displayed much intensity as the betrayed girl Liza, but the recital of the terrible wrong she had suffered was heard with a shudder by the audience, and in such a character the ability of Miss Robins made the story all the more distressing. Mr. Lewis Waller represented the student Fedor Ivanovitch, and upon his shoulders fell the chief burden of the play. In the scene where he told the story of the murder he gave a psychological interest to the incident which was effective. Mr. Herbert Waring played Prince Zosimoff with the finish and coolness requisite in portraying a character absolutely diabolical. Mr. William Herbert as the Englishman, Arthur Merrion, had a part for which he was well fitted, his manly and frank style being agreeably employed. M. Marius, as Arcadius Snaminski, makes of that personage a quaint character as a Chief of Police not wanting in good feeling. When the curtain fell the author appeared on the stage, but the greeting he received was not complimentary, nor is it likely that “The Sixth Commandment” will be added to the list of Mr. Buchanan’s successes.

___

The Echo (9 October, 1890)

SHAFTESBURY THEATRE.

_____

Once more has Mr. Robert Buchanan’s active pen been busy in supplying a new play; this time for the theatre which re-opened last night under the nominal management of Mr. Lancaster, but really of Mrs. Lancaster-Wallis—better known, perhaps, as Miss Wallis. The author has obtained his plot from Fedor Dostoieffsky’s novel “Crime and Punishment,” a work which has already been dramatised by French adaptors, their play, Le Crime et le Châtiment, having been produced at the Odéon, in Paris, some two years ago. The novel, in addition to being a psychological study of the working of conscience, is Zolaesque (save that it is not coarse) in laying bare some of the plague spots of Russian bureaucracy—and its heroine, though driven by Fate to become an outcast, remains pure in soul, and by her influence and teachings works out the redemption of the man she loved. From the materials at his command Mr. Buchanan has evolved a play, which, though possessing some powerful scenes and well-drawn characters and some excellent dialogue, is depressing from its length, and which ends in a manner to which we should scarcely have expected a practised playwright would have committed himself. The plot turns on a murder committed by a poor student Fedor Ivanovitch. In a fit of uncontrolled passion at the discovery that Liza, a low-born girl whom he loved, has been made a victim to the lusts of Prince Zosimoff, through the machinations of his pander Abramoff, an old usurer, Fedor strangles the latter. No sooner has he committed the crime than conscience awakened within him, and he is a prey to remorse. By a sudden turn of the wheel of Fortune, Fedor becomes rich, the change in his circumstances does away with the necessity for the marriage of his sister Anna with the Prince, to which she had only consented on account of the poverty of her family. The Prince, however, admiring her beauty, is determined to gain his ends, and almost forces her into a marriage by the threat that, unless she gives herself to him, he will hand her brother over to justice. Fedor learns from Zosimoff why Anna will sacrifice herself, so partly to save his sister and partly through the influence of Liza’s teachings, who had entreated him to take the first steps towards regaining his peace of mind by confession, he declares himself a criminal. He is sent to the salt mines as a convict. Liza follows him, and they find favour with the Governor Snaminski. Anna and her lover Alexis go to Siberia, to be near Fedor. Zosimoff tracks them, convinced that there he will be able to work his will on Anna—for he is all powerful, and the Government officials will not dare to interfere with anything he may do. Anna naturally repulses all his overtures, and he has just ordered her the knout, when he is himself condemned to a life in Siberia, “by order of the Czar.” Fedor is pardoned in consequence of having saved the Governor’s life, and we are left to suppose that he considers he has worked out the atonement for his crime and undergone his chastisement, and will have in Liza a wife who, sullied in the eyes of the world, yet remained pure, and who was the first to point out to him the enormity of his sin and lead him to repentance. The only approach to anything laughable throughout the play is the dry humour of Snaminski, a councillor and police superintendent, capitally played by Mons. Marius, and the flirting propensities of Sophia Orenberg with Arthur Merrion—a cynical, but amusing, Englishman, her lover—well filled by Miss Marion Lea and Mr. William Herbert. A clever though rather ridiculous, character is that of General Skobeloff, “the hero of Sebastopol,” an amorous and deaf warrior, of whom Mr. Ivan Watson gave a good sketch. Mr. Lewis Waller has not done anything better than his impersonation of Fedor Ivanovitch, a difficult part to play, but one which he has completely mastered. Another excellent performance was that of Miss E. Robins, as Liza; it was so natural, innocent, and modest. Mr. Herbert Waring gave a vivid and powerful representation of the heartless, sensual, and unbelieving Prince Zosimoff. Miss Wallis was tender, pathetic, and heart-stirring as Anna, her depiction of the agony of mind she suffered when swayed between the desire to save her brother and her abhorrence at the proposed marriage displayed much power. Smaller parts were well filled by Mr. Reginald Stockton, Miss Maude Brennan, and Mr. C. Arnold. The scenery is exquisite, the dresses very rich, and Mr. Arthur E. Godfrey has arranged some appropriate music, which sometimes, however, might with advantage have been omitted. M. Marius’s stage management was excellent, save for rather long waits. If acting would assure the success of a play, The Sixth Commandment should have a run, but it requires much curtailment. The final verdict was not altogether favourable.

___

Pall Mall Gazette (9 October, 1890 - p.2)

“THE SIXTH COMMANDMENT” AT THE SHAFTESBURY.

In the “Author’s Note” appended to last night’s programme at the Shaftesbury Theatre Mr. Robert Buchanan took special pains to deprecate any comparison between his new play, “The Sixth Commandment,” and the novel upon which it is admittedly founded. So far he has acted like a prudent man, inasmuch as the most casual consideration of the two works on their respective merits will hardly result in a verdict in favour of the drama. But when we come to examine the question whether or not Mr. Buchanan has done the right thing in discarding so many important details of Dostoievsky’s story, we cannot help feeling that in his desire to be as independent as possible the author of “Sophia” has adopted a somewhat suicidal course. However, Mr. Buchanan wishes his play to be judged as a play, and not as an adaptation of a novel; so let it be assumed, for the nonce, that “The Sixth Commandment” is perfectly new and original, and that its writer is not directly indebted to any particular source of inspiration. Well, taking the case upon these terms, can it be said that the piece is either interesting or amusing? Or, if it be gloomy and sombre in tone, is it, at any rate, morally satisfying and convincing? To each of these queries, we fear, a negative answer must be given. Mrs. Wallis’s latest venture is emphatically dull, and it lacks, moreover, those features which occasionally redeem a dull performance from absolute monotony. It is unmistakably flat, it is frequently stale, and it is wholly unprofitable. We see Mr. Buchanan’s difficulty. He went to the fountainhead bravely enough and dived in gallant style for his materials. But when he had brought them to the surface he was afraid of using them. There was the idea before him—a young man who stains his soul in an hour of despair with the crime of murder, and is haunted by the wraith of his guilty deed for the rest of his life. In Dostoievsky’s “Crime and Punishment”—will Mr. Buchanan pardon us for citing the book this once?—the hero’s victims are a mother and a daughter. Surely there is no lack of firm foundation here on which to build up a remorseful existence! But Mr. Buchanan hesitates to harrow up our feelings to this extent. At all costs he insists upon making his hero sympathetic, and so draws out to gossamer thinness the central motive of his plot. We have no brutal butchery of a couple of women here. On the contrary, it is only an objectionable usurer who is sent to his account during the momentary passion of Fedor Ivanovitch. The vile old scoundrel has refused the wretched Fedor the financial assistance he needs, and has even suggested that the young man’s sweetheart Liza should sell her honour to save her starving relatives. Little wonder that the fiery Russian boy, who is for ever soliloquizing on his sorrows, and who spouts Schopenhauer and socialism at the street corners for his own edification, as if his spirit were overflowing with heretical and revolutionary rage, flies at the throat of the venerable rascal and shakes the life out of him before he knows what he has done. It is surely mere manslaughter, if not something like justifiable homicide. And yet on this slender thread are hung all those absurd and exaggerated goadings of conscience which are intended to interest and excite but only weary and provoke us through five long acts. But does a deep-laid purpose underlie all this? Does Mr. Buchanan believe that Russophobia is languishing in the metropolis, and needs a sharp stimulus? One might almost think so from the highly-coloured picture he draws of the cruel brutality of officialdom under the Tzar. Look at the vicious debauchee, Prince Zosimoff, a man who pounces upon his female victims with equal avidity on the banks of the Neva and in the heart of Siberia; look at the cool venality of his creature Snaminski; and look at the diabolical visages of the police, who appear to heartily enjoy the infliction of physical pain, whether they are pummelling the St. Petersburg beggars or whether they are playfully lashing the shoulders of their cowering prisoners on the way to the mines. Unprepossessing characteristics these, surely! But Russia as she is governed in the nineteenth century is swallowed up in the general gloom of a play which, although received last night with some courtesy by a friendly and lenient audience, cannot be written down as either attractive or enlightening.

What could Mrs. Lancaster-Wallis do as the sister heroine of “The Sixth Commandment” but work pluckily in a failing cause? What could Mr. Lewis Waller do but play Fedor Ivanovitch with all his vocal and muscular resource? If sheer strength and vigour could have gained success for the piece, he would have achieved a real victory. What could that clever actor, Mr. Herbert Waring, do with so artificial and melodramatic a scoundrel as Zosimoff? Every one, doubtless, tried to do his or her best; but there was but little heart and elasticity about the performances of M. Marius, Mr. William Herbert, Mr. Ivan Watson, Mr. Reginald Stockton, or Miss Marion Lea. Miss Elizabeth Robins was perhaps more persistent in her efforts than most of her comrades, for her acting of the part of the unhappy Liza was eminently earnest and truthful. It was very close upon the hour of midnight when the curtain fell upon a last act which had recalled episodes in “Moths,” “Called Back,” and “La Tosca,” with much distinctness. The usual “calls” were given and taken; but there was no trace of enthusiasm in any part of the house.

___

St. James’s Gazette (9 October, 1890 - p.6)

SHAFTESBURY THEATRE.

MR. BUCHANAN’S NEW PLAY.

WITH a frankness bordering upon cynicism, Mr. Robert Buchanan has recently proclaimed himself a convert to the axiom “Je prends mon bien où je le trouve.” His new romantic play, “The Sixth Commandment,” produced last night at the Shaftesbury Theatre, offers ample proof that he is fully possessed of the courage of his opinions. Yet, in view of this candid avowal, one recognizes a certain measure of weakness involved in the admission that before writing his piece he had read Dostoievsky’s novel “Crime and Punishment.” The feeling is, however, quickly dispelled by Mr. Buchanan’s further assurance that he has not endeavoured to dramatize a work which he considers “unequalled and unapproachable.” In one sense the statement is perfectly true. Dostoievsky’s book is practically a psychological study of a youth who believes himself, like Napoleon, endowed with “the right to kill,” to shed blood, to pass par-dessus des cadavres, provided that be necessary for his own purposes. In the hands of the Russian novelist the man is possible; the mental phases through which he moves are acknowledged to be, under the circumstances, not only feasible but natural, while the incidents succeed each other as the inevitable outcome of his acts. But Mr. Buchanan has changed all this; he has torn the episodes from their original setting, placed them in a different atmosphere, and by such means so altered the tone and spirit of the story as to turn it into melodrama of the most commonplace type. The motive, a strong one in the book, becomes meaningless in the play, and the characters consequently lose much of their significance. In brief, Mr. Buchanan has seized upon whatever seemed to him startling and lurid in Dostoievsky’s work, and, forgetful that such elements deprived of their surroundings are apt to become merely grotesque, has fashioned out of them a purely melodramatic piece.

Of the characters, Prince Zosimoff, the villain, was unquestionably the best played last night. Mr. Herbert Waring has, indeed, seldom done anything so good. His performance was admirably natural and spontaneous, while, with every temptation to do so, he never once displayed the slightest tendency towards exaggeration. Mr. Lewis Waller’s Ivanovitch was also a fine piece of acting, only marred by a disposition on the actor’s part to do too much. A little more restraint in the beginning of each scene would vastly add to the effect of the climax. If M. Marius failed to make much of the rôle of Snaminski, chief of police, the blame must be attributed in some measure to the feebleness of the character. Mr. Reginald Stockton gave an excellent rendering of Alexis, the hero’s friend, while Mr. William Herbert and Mr. De Lange were quite equal to all that was demanded of them. The part of Anna, which Miss Wallis has assigned to herself, is not rich in opportunities; but her acting in more than one important scene proved genuinely impressive, and was marked by much dramatic power. Miss E. Robins has already done excellent work on the London stage, and yesterday evening she still further improved her position by her forcible and sympathetic performance as Liza. To Miss Marion Lea, drollest and most irresponsible of ingénues, praise must also be given. Mr. W. Russell, Miss Cowen, Miss Maude Brennan, and Miss St. Ange all played effectively in smaller parts. The piece has been sumptuously mounted, and, it may be hoped, will, despite its somewhat equivocal reception, prove a popular success for the new management.

___

The Globe (9 October, 1890 - p.3)

“THE SIXTH COMMANDMENT.”

In a new play of Russian life by Mr. Robert Buchanan, Mrs. Lancaster-Wallis re-appeared last night in her own theatre, the Shaftesbury, lately tenanted by Mr. Willard. All conceivable pains had been taken to secure a success. A cast of commendable strength had been secured, and the mounting gave the utmost possible amount of illusion. If a triumph was just avoided the reasons are not far to seek. The piece, though strong, is gloomy, didactic, long, and verbose. Of action there is abundance, and some of the situations, though difficult of acceptance, have a certain freshness. When, however, a theatrical effect is reached, it is lost in superfluous dialogue. Mr. Buchanan is now at the point at which he should think of his reputation and strengthen the language, which in this instance, at least, is preachy and diffuse. For his inspiration in writing “The Sixth Commandment” he is avowedly indebted to the “Crime and Punishment” of Doskoievsky, though he claims, while availing himself of suggestions, to have diverged as widely as possible from the plot, characters, and situations of his original. The amount of his indebtedness we cannot gauge. His story has at least the unredeemed gloom which is a frequent attribute of Russian fiction.

The interest centres in the mad passion of Prince Zosimoff for Anna Ivanovna, a young lady so much his inferior in wealth and social station that his selection of her for his consort is not easily explicable. His suit is unprosperous, firstly because his character is objectionable, and next because the lady is already provided with an obscure but favoured lover. In a psychological frenzy, which we fail to grasp, springing partly from the pinch of poverty, and partly from moral indignation at the character of his victim, Fedor Ivanovitch, the brother of the fair Anna, has murdered a disreputable old money-lender, known as Father Abramoff. His responsibility for this crime the youth is indiscreet enough to betray in the course of a heated argument. The significance of his avowals the authorities are far from grasping; the Prince is, however, more astute. By the aid of the police, who are his pensioners, he brings Anna to a spot in which, as he knows by a marvellous exercise of judgment, she will overhear the criminal confess his offence. Armed with the power thus conferred, the Prince imposes on the distracted girl marriage with him as the price of his silence. From the sacrifice she is ready to accept, the heroine is saved by her brother, who, rather than she shall fulfil her compact, avows his guilt, and accepts his punishment, which is banishment to Siberia. Thither, accordingly, he goes, and is followed by all the principal characters, including the Prince, who makes one more desperate endeavour to secure his mistress and indulge what he calls his caprice. Then the tables are turned: a pardon arrives for Fedor from the Czar, and the Prince, for some untold offence, is imprisoned in his stead.

The first act is unmitigated gloom; the second presents a not very impressive picture of fashionable society in St. Petersburg. Act the third has an original scene, not very easy of reception, in which Anna, through a partition between two rooms, overhears the confession of her brother. In the fourth act a strong theatrical situation is missed, since, after the hero has proclaimed his guilt and brought matters to a climax, the heroine persists in scolding her naughty lover. The fifth act is simply a dénoûment. The whole constitutes a conventional melodrama which, with daring use of the knife, and the introduction of light and shade, might possibly interest an Adelphi audience.

Such interest as there is attaches itself, however, chiefly to the villain, who, besides being, in the hands of Mr. Herbert Waring, the best acted character in the piece, is really the most sympathetic. His cynicism and dare-devilry recall the Don Juan of Tirso de Molina and Molière; his bearing is that of a gentleman; and his sentiments, immoral as they are, are more convincing than those of the hero, who puts to shame Eugene Aram and other sentimental criminals, and murders people, it may almost be said, out of love of virtue. Mr. Lewis Waller was very earnest and impassioned as this didactic and distressed young gentleman, whose behaviour on every possible occasion was as unwise as it could possibly be. Mrs. Lancaster-Wallis was also earnest as his sister, and rose in one or two scenes to a display of power. M. Marius had a part which seemed at one time likely to lighten the play, but faded into conventionality. Such little comic relief as existed was assigned to Mr. Herbert as an English attaché and Miss Marion Lea as a Russian young lady. Miss Maude Brennan and Miss E. Robins were fairly good as peasant women. Mr. George Seldon showed melodramatic ability in a thankless part. The acting throughout was excellent, and won a favourable reception from the audience. The author received, however, a mingled greeting of hooting and applause. “The Sixth Commandment” could not well under any conditions have proved a great piece. It would, however, have been more workmanlike and have stood a better chance, had Mr. Buchanan or the management known how “to blot.”

___

The Yorkshire Post (9 October, 1890 - p.4)

Mr. John Lancaster signalised his re-entry into the active management of the Shaftesbury Theatre last night, our London Correspondent says, by the production of a new play from the prolific pen of Mr. Robert Buchanan, entitled The Sixth Commandment. It is styled a “romantic drama,” but is in reality a melodrama of the conventional type, with plenty of rousing situations and stirring, though improbable, incidents. The scene is laid in Russia, and there is, of course, the usual picturesque dramatis personæ of scoundrelly princes, police spies, and downtrodden serfs, with scheming mothers giving their daughters in marriage to servile libertines. As to the plot, it is much too intricate to be explained here, but it may be said that the piece turns mainly on a murder committed by a young aristocrat, and used subsequently by a prince of the worst morals to bring pressure to bear upon the young man’s sister to murder her brother. There is an unpleasant flavour about a good deal of the dialogue, and several of the scenes are decidedly risky; but the reception accorded to the piece was, on the whole, favourable.

___

The Jewish Chronicle (10 October, 1890 - p.7)

“THE SIXTH COMMANDMENT.”

From the Jewish standpoint there is a serious blot on the new romantic play by Mr. Robert Buchanan, which under the above title was produced on Wednesday at the Shaftesbury Theatre. Modern playwrights seem to find it difficult to keep Jewish money lenders out of their dramas. These creations, while generally obnoxious, are obviously such gross caricatures that while they make us angry we can still afford to laugh. It has been reserved for Mr. Buchanan to give us in Abramoff, a St. Petersburg usurer, a creature of so despicable a character that much harm would be done to the Jewish cause in Russia were he to be accepted as a type of the Jews in that country. He is a relentless usurer, a heartless landlord, and to crown all he lures a poor girl to the palace of his patron, Prince Zosimoff. It is fortunate that the exciting incidents of the drama prevent the spectator from giving too much attention to this gross libel on the Jews, and that through his murder Abramoff disappears early from the scene. An incident immediately following on the discovery of the dead body is a glaring incongruity. Abramoff is a Jew, but when a crowd assembles on the alarm being given of his assassination, the duty of praying over the corpse is assigned to some Priests of the Orthodox Church, who happen to be conveniently at hand, and a dirge of the church is sung for the dead. Of more questionable taste is the appearance of Mr. H. de Lange, himself a Jew, in the character of the scoundrel Abramoff. Mr. Buchanan’s serious plays are mostly written with a purpose. We can almost forgive him, therefore, fro creating such a villain as Abramoff, on account of the light—so timely now when Russian affairs are to the fore—he throws on the barbarities practised by Russian officials on the unfortunate wretches who are deported to Siberia and on the licentiousness prevailing in the upper circles of Russian society. Through the mouth of an attaché to the British Embassy, he declares that although the Czar and his Government may silence the people, they cannot prevent the expressions of free thought and horror from other lands penetrating even into Russia.

The principal characters are admirably played by Mrs. Lancaster (Miss Wallis), Mr. Lewis Waller, Mr. Herbert Waring, M. Marius, Mr. William Herbert and Miss Marion Lea, and Miss Cowen renders good service in a minor part. The piece is splendidly mounted, the furniture and appointments are specially made for the production by Mr. James S. Lyon, of Holborn, and the uniforms by Messrs. L. and H. Nathan, of Coventry Street.

___

The Jewish Standard (10 October, 1890 - p.11)

“The Sixth Commandment,” produced last Wednesday night at the Shaftesbury is not, I hope, to be followed by the other items of the Decalogue. For in that case I shall (as a dramatic critic bien entendu) have to trample on them all. “The Sixth Commandment” is a dull, gloomy piece, and in spite of its teaching it is likely to result in the murder of Mr. Robert Buchanan by

MARSHALLIK.

___

The Nottingham Evening Post (10 October, 1890 - p.4)

Mr. Robert Buchanan’s new piece at the Shaftesbury Theatre is heavy melodrama of the deepest die. The author frankly enough acknowledges his indebtedness to the Russian story Dostoiaosky’s “Le Crime et la Châtiment.” But the “Sixth Commandment,” the name which Mr. Buchanan gives to the play, is a very different thing to the crime and punishment of the novel. The story on the stage is that of an old usurer who is a scoundrel in other ways, and who is sent to his account because he will not supply the sinews of war to a family he has ruined unless the young man of the house gives up the honour of his lover to his keeping. There is a good deal of Russian Nihilism mixed up with the plots and also some quips at the Russian methods of government. A moan of horror goes through the whole of the five acts. There is much that is good in it, and plenty of strong dramatic situations which Miss Wallis’s company are fully capable of dealing with, but to make it go it needs compression, and possibly also the introduction of a somewhat lighter character to relieve the monotony of the doleful air which pervades it.

___

The Stage (10 October, 1890 - p.14)

LONDON THEATRES.

THE SHAFTESBURY.

On Wednesday evening, October 8, 1890, was produced a new romantic play in five acts, by Robert Buchanan, called:—

The Sixth Commandment.

Prince Zosimoff ... Mr. Herbert Waring

Arcadius Snaminski ... M. Marius

General Skobeloff ... Mr. Ivan Watson

Fedor Ivanovitch ... Mr. Lewis Waller

Alexis Alexandrovitch ... Mr. Reginald Stockton

General Wolenski ... Mr. W. Russell

Arthur Merrion ... Mr. William Herbert

Moustoff ... Mr. M. Byrnes

Kriloff Kriloffski ... Mr. George Seldon

Petrovitch ... Mr. G. Fane

Father Abramoff ... Mr C. Arnold

Landlord ... Mr. Herbert Basing

Sergeant of Cossacks ... Mr. C. Lander

Sergeant of Police ... Mr. F. H. Morton

Ivan ... Mr. H. Bayntun

The Princess Orenburg Mrs. Richardson

Sophia ... Miss Marion Lea

Pulcheria Ivanovna ... Miss Cowen

Anna ... Mrs. Lancaster-Wallis

Catherine Petroska ... Miss Maude Brennan

Liza ... Miss E. Robins

Katel ... Miss C. Bernand

Marfa ... Miss J. St. Ange

Under the management of Mr. Lancaster, the proprietor of the theatre, the Shaftesbury reopened its doors, after but a short closure, with a play which, though the scene lies in Russia, deals not at all with Nihilism or conspiracy, though sedition and revolt are touched upon, and strong colours are given to abuses in the existing administration of the State. These, however, do not constitute the main interest, but supplement and aid in working out a doctrine of atonement on the part of a man who has broken the divine and human law “Thou shalt not kill.” Fedor Ivanobitch is a young student of good but poor family, who is in that unhappy state when the mind rebels against fate and ceases to believe in providence. His sister, Anna, has, through stress of circumstances, been compelled to promise herself in marriage to prince Zosimoff, an utterly vicious libertine, but one who holds a high position in the State, and is a favourite of the Czar. In the first act, “A Street over the Banks of the Neva, St. Petersburg,” we learn that Fedor is deeply attached to Liza, a poor girl, whose mother and little sister are on the point of starvation. She has attracted the attention of the Prince, who offers her insult. Finding that she repels his advances, he entrusts a letter to Abramoff, an old money lender, to be delivered to her, in which she is told that if she will apply at a certain address, she will find one willing to assist her and her family. The girl goes to the house, it is the Prince’s palace, there she is detained, and when she escapes she is a disgraced woman. Fedor learns from Abramoff that he has pandered to his patron’s vices, that money as he says will buy everything and everybody; and carried away by his rage at the old man’s confession of the hand that he has had in Liza’s fall, he catches him by the throat and strangles him. Liza’s mother goes to beg a morsel of bread at Abramoff’s house; she discovers the old man dead, raises an alarm, the police rush in, and presently the priests arrive and sing “the dirge of the dead.” At the same time Fedor’s fellow-student, Alexio, hands him a letter which informs him that by the death of a relative he is now rich and noble. In the second act, a ball-room scene in the Salon of the Princess Orenburg—Anna and her mother are on a visit to the Princess. Zosimoff urges his suit on Anna, but she now unconditionally refuses him, for she is in love with Alexio. The Prince does not pretend any great affection for the woman he wishes to make his wife, but he is piqued, and is now determined to satisfy his caprice. Fedor arrives, and it is seen that already remorse is preying upon him. He almost betrays himself in propounding in the shape of a theory as to the murder of Abramoff, the real event as it occurred. This deceives Snaminski, the head of the police, but the suspicions of the Prince are aroused, and he gives Anna twenty-four hours to decide as to his suit, hinting that at the end of that time if she refuses him he may bring forward reasons which may induce her to change her determination. The third act takes place in the “Interior of a common lodging-house,” a double set showing two rooms. In one is Anna, she has hidden herself here away as she hopes from Fedor, lest he should learn her shame. The Prince has tracked her down, as he feels sure that her lover will seek her out. He is right, for Fedor soon enters. The Prince, through Snaminski, knows of his coming, and he brings to the next room Anna that she may through the partition overhear all that passes. Fedor has come to offer marriage to Anna. In a beautifully-written scene she tells him of how she has been rendered unworthy to mate with him, good and noble as he is. He then, to put them on an equality, tells her of the crimes of which he has been guilty. Thus the sister learns her brother’s danger, and the power that Zosimoff has over him. The fourth act takes place in the Gardens of the Palace Taurida. The Prince now threatens Anna that unless she will be his wife, Fedor shall be given up to justice. Loathing the man as she does, for she has learnt all his baseness, to serve the brother she loves so dearly, she gives way. But when Alexis arrives with Fedor, her heart goes back to her lover. Zosimoff then thinks to work upon Fedor’s fear of detection, but he has misjudged his nature; for so soon as the young fellow learns the reason of his sister’s sacrifice, he at once confesses his crime before everybody, and is handed over to justice. His life has been a hell on earth to him, and his confession appears to be the first step towards his atonement. The close of the play takes place in Siberia. Fedor is working out his sentence in the salt mines. He is shown some kindness by Snaminski, whom the Prince has got appointed governor over the convicts in order to get rid of one who is dangerous through knowing too many of his secrets. Liza Kay found her way to the convict station with a batch of prisoners, and Anna and Alexis have braved the desperate journey to see Fedor once more. They all meet. Zosimoff, however, has followed them, as he imagines that in Siberia his will his law, and that Anna will be completely in his power. In a very powerful scene he tells her she is now completely at his mercy, and is actually forcing her to his arms when her brother saves her from his violence. The Prince is furious, and has just ordered the soldiers to knout Anna and put Fedor in chains when General Wolenski arrives, with a free pardon for Fedor granted by the Czar at the intercession of Snaminski, in consequence of Fedor having saved his life. Prince Zosimoff is at the same time informed that his malpractices have been discovered, his estates confiscated, and himself condemned to lifelong slavery. He is consistently defiant to the last, and the curtain drops as Fedor falls upon his knees in thankfulness to Heaven that his atonement has been accepted and his sin pardoned.

There is but little to lighten the sombreness of the above beyond the love scenes that take place between Sophia de Emberg, a lively, bright, and rather flirting girl, and Arthur Merrion, an English attaché, who has evidently made up his mind to win her from General Skobeloff, “the hero of Sebastopol,” a decrepit old gentleman, very deaf, who, only hearing half what is said in his presence, occasionally gives some very mal a propos answers. Although Arcadius Snaminski is armed with all the powers of the law, and should be a formidable creature, his natural good nature warring with his official instinct makes the character amusing. There is a well maintained interest in the working out of the plot, which would be stronger even but that it is occasionally delayed by scenes which require considerable compression, and that by the introduction of characters that have but the very remotest bearing on the plot. The final act also stretches probability to its utmost limits. All the principals are brought together in remote Siberia, even to Sophia and Merrion on their honeymoon tour, and Prince Zosimoff, in the persistent pursuit of his “caprice,” as he elects to term his unholy projects, would scarcely tear himself away from his duties and his pleasures in St. Petersburg to follow up a woman who so detests him. Mr. Buchanan admits that he is indebted to Fedor Doskoievsky’s Russian realistic novel “Crime and Punishment” for the main incidents of his play. Having read the work—in a great measure a psychological study—we must compliment the author on the skilful manner in which ha has skimmed over some very dangerous ice, in the alteration of the painful incidents of Liza’s career (the Sonia of the novel), and eliminated much that on the stage would have been too repulsive. Of the acting we must speak next week; we will only now refer to it so far as to say that Miss Wallis has engaged, as will be seen, a most excellent company, and that the fair manageress—for manageress she really is—has mounted the play beautifully.

It should perhaps be mentioned that a French dramatic version of the novel was produced, under the title of Crime et Chatiment, as a five-act drama, by MM. Paul Ginisty and Hugues le Roux, with music by Henri Maréchal, at the Odéon, Paris, September 15, 1888.

___

The Era (11 October, 1890)

THE LONDON THEATRES.

_____

THE SHAFTESBURY.

On Wednesday, Oct. 8th, for the First Time,

a New Romantic Play, in Five Acts, by Robert Buchanan,

called

“THE SIXTH COMMANDMENT.”

Prince Zosimoff ... Mr HERBERT WARING

Arcadius Snaminski ... M. MARIUS

General Skobeloff ... Mr IVAN WATSON

Fedor Ivanovitch ... Mr LEWIS WALLER

Alexis Alexandrovitch ... Mr REGINALD STOCKTON

General Wolenski ... Mr W. RUSSELL

Arthur Merrion ... Mr WILLIAM HERBERT

Moustoff ... Mr M. BYRNES

Kriloff Kriloffski ... Mr GEORGE SELDON

Petrovitch ... Mr G. FANE

Father Abramoff ... Mr DE LANGE

Landlord ... Mr HERBERTE BASING

Sergeant of Cossacks ... Mr C. LANDER

Sergeant of Police ... Mr F. H. MORTON

Ivan ... Mr H. BAYNTUN

The Princess Orenburg ... Mrs RICHARDSON

Sophia ... Miss MARION LEA

Pulcheria Ivanovna ... Miss COWEN

Anna ... Mrs LANCASTER-WALLIS

Catherine Petroska ... Miss MAUDE BRENNAN

Liza ... Miss E. ROBINS

Katel ... Miss C. BERNARD

Marfa ... Miss J. ST. ANGE

Mr Buchanan’s statement, printed on the programmes presented at the Shaftesbury Theatre on Wednesday evening last, that he had, in his new drama, merely “utilised certain suggestions” in Dostoïevsky’s curious novel, “Crime et Châtiment,” was perfectly accurate. There is as little, indeed, in common between Dostoïevsky’s Rodion and Mr Buchanan’s Fedor Ivanovitch as there is kinship between the characters of the seduced, but sympathetic, Liza of the play and that of the little street-walker, Sonia, of the novel. Mr Buchanan has merely taken the Russian tale as a start-point, and has dashed boldly away from it into a career which is fairly exciting in the middle, but which dies away all to nothing at the end. That there is a public at the West end for the more finished and probable sort of melodrama has already been proved, but audiences of a certain degree of enlightenment are more exacting in their demands than an Adelphi pit or an Elephant and Castle gallery, and, like Quentin Durward, do not like “being borne in hand like a child” by an author who presumes too much upon their want of sense and information. The Sixth Commandment falls between two stools. It is too straggling and “talky” to be popular, and too crudely theatrical to be praised. It must be stated, however, that the play is a very uneven one, and that its three first acts are conventionally effective. The first opens in St. Petersburg, where we find Fedor Ivanovitch, a poor student, meditating bitterly over the maxim that “gold buys everything.” He knows that his sister Anna is about to be sacrificed to Mammon in the person of the dissolute Prince Zosimoff; and he also sees Liza, the daughter of a drunken droshky-driver, sorely tempted to accept the disgraceful offers of the Prince for the sake of obtaining food for her starving mother and sister. In his overwrought condition, the callous and cynical remarks of Father Abramoff, an old money-lender, so excite him that he pushes the old man into the passage of his own house and strangles him. An alarm is raised. Fedor is not suspected; but receives, only too late, the news that a relative has died leaving him a fortune.

In the second act, in the Salon of the Princess Orenburg, Fedor, now a Count, is mixing in high society with his mother and sister. The subject of Abramoff’s murder crops up, and Fedor cannot restrain himself from a hysterical tirade which excites the suspicions of Zosimoff. The latter, after ascertaining that Anna intends to break off the engagement made between them, tells her that her brother is the murderer of Abramoff, and that unless she marry him (Zosimoff) he will denounce Fedor to the police. This is the climax of the second act. The third takes place in the interior of a common lodging-house, to which Zosimoff brings Anna to convince her of her brother’s guilt. He takes her into an apartment next to that of Liza Petroska, who has been seduced by Zosimoff, but has fled from his palace at the first opportunity. Fedor visits Liza; and, after she has told him of her shame, he confesses his crime to her in the hearing of his sister, who falls fainting as the curtain descends.

So far the play, despite certain obnoxious matters of detail, is interesting and effective. But the promise of the earlier acts is not fulfilled in those which follow. There is much “see-sawing” and going over the ground again in the fourth, which ends in Fedor, sooner than let his sister be sacrificed, owning to having murdered Abramoff, and being taken off to that region useful to the melodramatist, Siberia. The piece now degenerates into transpontine melodrama. Everyone comes to the military outpost, where soldiers in sheepskin caps chaff their commander, and act as “whippers-in” to a pack of howling, growling convicts. Zosimoff threatens Anna with personal assault, and dares her to fire at him with a revolver which she has got possession of. She shoots at the prince but misses. Fedor dashes in, and casts him to the earth, and all difficulties are overcome by the arrival of two documents from the Czar—a free pardon for Fedor and a sentence of perpetual imprisonment for Prince Zosimoff, an easy, but somewhat arbitrary, method of ending the play happily. Such minor absurdities as a chief of police, who is ordered about like a puppy, and who takes snubs and insults like a lamb, a lunatic who accuses himself of the crime committed by Ivanovitch, and a procession of Greek priests, who, unlike our English police, are on the spot at the middle of the night immediately when wanted, need not, perhaps, be dwelt upon. If Mr Buchanan were to rewrite the two latter acts of The Sixth Commandment so as to make them close and thrilling the piece might then do well in the provinces; but we fear that, in any case, there is little chance of its success at the Shaftesbury.

This is the more to be regretted, as the work put into the production, both in the way of acting and mounting, was remarkably good. We have rarely seen a better interior than the lemon-yellow salon of the Princess Orenburg in the second act, and the Gardens of the Palace Taurida in the third formed an equally effective set. The ladies’ dresses were tasteful, pretty, and appropriate, and the play had evidently been carefully rehearsed, and , thanks to the excellent stage- management of M. Marius, went almost without a hitch. The best performance of the evening was undoubtedly Mr Herbert Waring’s Prince Zosimoff. He managed to hit the happy medium in delineating the accomplished villain, and gave to his impersonation sufficient repulsiveness without neglecting the “society” side of the character. M. Marius in the absurd and uncongenial rôle of the impossible police official already referred to could do no more than raise an occasional laugh, and Mr Ivan Watson made General Skobeloff an officer of opera bouffe. Mr Lewis Waller’s style suited the character of Fedor Ivanovitch well, and he put much power into his rendering of the rôle, acting throughout with a sustained energy which was worthy of warm praise, and occasionally rising to a high histrionic level. Mr Reginald Stockton was acceptable as Alexis Alexandrovitch. Mr William Herbert and Miss Marion Lea as a couple of those comedy lovers so detested by the new school of realism, acted extremely well, and were as amusing as their parts would permit; and Mr de Lange’s villainous exultation as the pander and pawnbroker Abramoff was graphic and effective. Miss Cowen made an agreeable and affectionate Pulcheria Ivanovna, and looked extremely well in the part; and Mrs Richardson was, in manner, speech, and bearing, an excellent representative of the Princess Orenburg. Mrs Lancaster- Wallis had a part which suited her exactly in that of Anna, and sustained it with accomplished skill and cultivated power. In the scenes with Zosimoff in the second act, and in the interview with the Prince in the third, she depicted the varying emotions which swayed the unhappy girl in a manner which deeply thrilled and keenly interested her audience. Miss Maude Brennan took full advantage of her brief opportunity as Catherine Petroska. A charming performance was Miss E. Robins’s Liza, tender in tone, yet at times rising to a high level of emotional and histrionic merit. Entirely unaffected, and replete with sweetness and sympathy, Miss Robins’s performance was decidedly noteworthy. Of the minor rôles, that of a cringing lodging-house keeper was well sustained by Mr Herberte Basing, and Miss J. St. Ange neatly represented the domestic servant, Marfa. Mr Buchanan was called before the curtain at the close of the performance, but the mixed reception which greeted him augured doubtfully for the future success of his work.

___

The Illustrated Sporting and Dramatic News (11 October, 1890 - p.26)

DRAMA.

SHAFTESBURY THEATRE.

To the programmes of the new play by Mr. Buchanan with which Miss Wallis reopened the Shaftesbury on Wednesday night, is prefixed a note deprecating the notion that the playwright in altering the plot of Crime et Châtiment believes himself to have improved upon what he terms a “literary masterpiece.” With this, however, it seems to us that the playgoing public has very little to do. Doskoievsky’s famous novel was not very much of a success when adapted for the stage of the Odéon in Paris; and if Mr. Buchanan saw his way to do better by diverging widely from the original scheme of the tale while utilising much of its material, he was obviously quite within his artistic rights. For ourselves we are inclined to think with him that this fine, albeit gloomy, Russian romance is too erratic in its characterisation and its incident alike to be suitable for the theatre without considerable modification. Its hero, with his momentary blood-hunger, and his life-long repentance for a pair of wholly unjustifiable murders, is too exceptional and morbid a character to “come out” with any real effectiveness behind the footlights. But no very useful or very logical result is attained by supplying something very like a justification for a crime which is reduced to mere homicide, and yet retaining the criminal’s nervous remorse. What is more important is that The Sixth Commandment, as Mr. Buchanan christens his piece, is heavy, dull, and terribly long in its exposition of a rather commonplace story of violence, that none of his dramatis personæ commands much sympathy, and that the force of the action is sadly diminished by its padding of dialogue. There are good situations—if no particularly novel ones—in the play, which has much in common with the melodrama that used to be popular at the Victoria in days gone by. But these situations are illustrated in a manner altogether too diffuse, and they lose half their point in their over-ambitious treatment. The Sixth Commandment began at eight and was not over till twenty minutes to twelve. If a good three-quarters of an hour had been taken out of it, a fair popular success might have been scored; as it was, the audience was too tired to agree upon its verdict, and very doubtful sounds mingled with the applause of those who so liberally encouraged Miss Wallis’s enterprising production.

The hero responsible for breaking the commandment “Thou shalt not kill” is Fedor Ivanovitch, an impecunious student who seems to think his poverty a legitimate excuse for indulging in much high-flown talk against people richer than he is himself. He never seems to think about setting to work to earn money, but contents himself with railing against the fate which leaves his humble sweetheart Liza to starve, and compels his sister Anna to promise her hand to the dissolute Prince Zosimoff, whom she despises and detests. It is while in this gloomy mood that Fedor learns from the lips of old Abramoff, the money-lender, his share in a conspiracy whereby a wealthy nobleman has bought Liza body and soul: and in righteous vengeance he strangles the money-lender and leaves him dead amongst his bags of gold. No sooner has he committed this murder than he learns that he has come into the fortune which might have saved his sweetheart from her shame; but the news comes too late to restore his peace of mind. “What’s done cannot be undone,” and the hysterically-mournful young man cannot even rejoice with his sister in her escape from the need to marry the rich suitor whom she loathes. With incredible lack of self-command Fedor manages by his strange way of discussing the murder to arouse the suspicion of the Prince, who thereupon sees his way to repeat a time-honoured stroke of rascality. He will accuse Fedor of the crime, and make his sister’s reluctant hand the price of silence. Up to this point the action is fairly plausible, but at the scene in which the wicked Prince contrives that Anna shall overhear her brother’s confession of guilt, all probability is thrown to the winds. We have already had reason to wonder at the complete subjection in which this young nobleman holds Arcadius, the Head of the Police: we are now positively awe-struck by the omniscience which enables him to foresee exactly what his victim is going to do, and when he is going to do it. Anna is now in his power, but much time is wasted in showing how, when the girl is prepared to sacrifice herself for her brother’s sake, Fedor’s manliness reasserts itself, and he proclaims himself guilty rather than purchase safety at his sister’s expense. He is sentenced to imprisonment in Siberia, whither, of course, he is followed by most of the other dramatis personæ, including Anna, who is still persecuted by the Prince, and who defends herself against his approaches with a revolver. Her first bullet misses, whereupon the Prince, with a singularly inconsistent chivalry, picks up the weapon—which has fallen from her timid hand—and courteously offers her another shot at his unmanly breast. The offer is declined, and the final punishment of the titled scoundrel comes in an opportune but unexplained decree from the Czar depriving him of his estates, and condemning him to the mines of Siberia. At the same time Fedor obtains a full pardon, and the study of his crime is brought to its rather inconclusive end.

Except as regards one of its characters, The Sixth Commandment is played only moderately well. Mr. Lewis Waller works hard but stagily over the socialist ravings and the remorseful hysteria of Fedor, but he is not able to impart to the strained sketch any real human nature. Miss Wallis is earnest, but she does not touch the note of true pathos in Anna’s anguish, any more than does Miss Robins in the corresponding woes of Liza. The sorrows of these ladies are graceful and womanly enough; but somehow they are not heartrending. The gaiety of Miss Marion Lea in the part of a coquettish ingénue is forced and affected, and Mr. Herbert in the only other comedy part has no chance of rising above empty conventionality. M. Marius is wasted upon the curiously weak ad inconsistent character given to the Head of Police, but he does like an artist what little is asked of him; and a good word may be said for the minor services of Miss Cowen. Mr. Ivan Watson gives a ridiculous caricature of an old Russian general. The one exception to which allusion has been made is the Prince Zosimoff of Mr. Waring, a singularly well considered, smooth, and forcible rendering of polished brutality.

The Sixth Commandment is handsomely mounted, especially in its illustrations of the Banks of the Neva by moonlight, and of a fête in the Palace Taurida. The scenes, however, take much too long to set, and some of their effects of simultaneous sunset and moonlight seem, to say the least, decidedly capricious.

___

Reynolds’s Newspaper (12 October, 1890)

PUBLIC AMUSEMENTS.

_____

SHAFTESBURY THEATRE.

Under the fantastical title of “The Sixth Commandment”—“Thou shalt do no murder”—the prolific Mr. Robert Buchanan, on Wednesday evening, produced a play at the Shaftesbury Theatre, which is distinguished by all the knowledge of stagecraft, and marred by all the dramatic faults peculiar to this author. The idea of the piece is taken from the most Æschylean of modern novels—Th. Doskoievsky’s “Le Crime et Le Châtiment”—Crime and Punishment. An adaptation of the novel in French was produced some time ago at the Odéon Theatre, but it had no considerable success. Indeed, it is doubtful whether that great tragedy could be presented in such a form on the stage as to win approval from any beyond an eclectic circle. The mind of the ordinary playgoer is not familiar with those profound depths of the human character; it resents being called upon to take sides in the philosophy of social phenomena. If any corroboration of this assertion were required, it may be found in the cold reception accorded to Henrik Ibsen’s plays, which deal with the contemporary problems of society. Where Mr. Buchanan departs from the plot of Doskoievsky he has not effected an improvement. In the first place, his hero does not really commit a murder. His victim is not intended to be killed; he is throttled, and dies under the process. This imperfect start gives a false ring to all the subsequent exuberance of repentance indulged in by Fedor Ivanovitch. And, were it not so, Mr. Buchanan makes him an untrue and mawkish fellow, who, reciting pessimistic theories, and quoting Schopenhauer that the world is essentially corrupt, and that the devil is its Prince, goes about maundering of God, and redemption, and atonement, after the involuntary slaying, consummating the absurdity by falling on his knees at the drop of the curtain, weakly and dolorously declaring that, though man might forgive him, he could not expect the forgiveness of the Almighty. This is all false sentiment, false theology, false art. The author might have been warned by the reception of the intensely ridiculous incident of the roué in his “Struggle for Life,” at the Avenue Theatre, who similarly falls on his knees to ask pardon from God. Mr. Buchanan seems to pigeon-hole his bathos, and to expose it at intervals on the stage as a trader does his wares. Those who have read “Le Crime et le Châtiment” will remember that the story turns upon the murder of an old female usurer by an impecunious Russian student. He slays for money, and he does not repent. Mr. Buchanan’s Fedor kills a doddering old male money-lender, because he asserts that everything and everybody can be bought for gold, including Liza Petroska, an humble girl whom Fedor loves, and whom poverty actually does impel to sell herself to Prince Zosimoff, a notorious scoundrel. Doskoievsky’s hero continually argues, “What was the use of the life of that wretched old woman? It was rather a virtue to put an end to an existence so unworthy.” Hear how the Russian novelist makes Fedor talk about his crime. “‘Why should my conduct appear so repulsive?’ he asked himself. ‘Because it is a crime? What signifies the word crime? My conscience is at rest. Without doubt I have committed an illicit act. I have violated the letter of the law and spilt blood. Very well, then; take my head; voilà tout!’” There is a character with dramatic consistency—one who does not rave about Schopenhauer and deny God in the first act, and for most of the remainder of the play snivel about the moral law which he has offended. Instead of naming his play “The Sixth Commandment,” Mr. Buchanan ought to have called it “Crime and Repentance.” The character of Fedor Ivanovitch, of course, overshadows the other personages in his mimic world. These, however, are the sombre, albeit unconscious, weavers of his destiny. He slays Father Abramoff, the money lender, for the sake of Liza; he accuses himself of the crime that his sister Anna Ivanovna may not sacrifice herself in marriage to Prince Zosimoff, who alone knows his guilt; his crime, even , is committed two or three minutes before he learns that from abject poverty he has been raised to affluence by the death of a relative. This part was played by Mr. Lewis Waller with a tragic intensity of passion, for which there can be no word but praise. Mr. Herbert Waring, by the very force of his talent, gave life to the colourless part of Prince Zosimoff. M. Marius made a comic, and altogether impossible Head of Police, for which the author, and not the actor, is to blame. M. De Lange as the money-lender shook himself free from the trammels of the traditional stage Jew, and gave a powerfully realistic rendering of the character. The Liza Petroska of Miss E. Robins was a performance of exceptional merit, far above the hysterical, sentimental, commonplace, odious female to whom we are so often treated in such characters. Mrs. Lancaster-Wallis at times was good as Anna Ivanovna. There is a little stiffness, however, in her performance, doubtless due to nervousness. To arouse our entire sympathy, the part must be more subtily played. Miss Marian Lea, bright, attractive, and winning as she is, does not surely suppose that the manners of the daughter of a Russian princess are not those of a skipping romp? The student, Alexis Alexandrovitch, was weakly played by Mr. Reginald Stockton; and Mr. William Herbert’s Arthur Merrion, an attaché of the British Embassy at St. Petersburg, was rather conventional. The unnamed performers will require a little more drilling to make their stage pictures effective, notably so in the fifth act, where the behaviour of the prisoners and soldiers borders on the ridiculous. The play is too long, and, as usual with Mr. Buchanan, the last act, which ought to summarize with brief and graphic touches, is intolerably spun out. Like a good deal of the author’s recent work, this piece bears marks of haste; but it has in it undeniably the elements of popularity. The events which it depicts would be mostly impossible in the Russia of to-day, where students are not allowed to go about spouting Socialism and Revolution to policemen. In the first act there was an effective picture of St. Petersburgh and the Neva at night, by Mr. Walter Hann. The performers should consider whether it does not mar the illusion to appear before the curtain between the acts in a tragedy.

___

The Referee (12 October, 1890 - p.2)

DRAMATIC & MUSICAL GOSSIP.

FOR the first time perhaps since its promulgation an Author’s Note has been appended to “The Sixth Commandment”—in proof whereof see programme of Mr. Robert Buchanan’s new romantic play in five acts, which was produced at the Shaftesbury on Wednesday evening. There be those who admire Buchanan’s literary ability in various direction, and yet deny to him the possession of a sense of humour; and I am of them. Yet I acquit him of irreverence—intentional, at any rate. The “Notes” which this author appends to his dramatic works have now come to be looked for as matter of course. In fact, if I didn’t see one in the window—I mean on the programme—I should ask for it, and see that I got it. This time the tag of the Note is to the effect that the author deprecates all comparisons between his play and “a literary masterpiece.” R. B. evidently knew something when he wrote this. I have not read Doskoievsky’s novel “Crime and Punishment,” which Buchanan rates so highly, and certain incidents in which he has used for his present purpose. That, however, doesn’t matter, as the play’s the thing that is to be judged. Briefly, then, “The Sixth Commandment” is gloomy, tedious, and overdone with talk—now pessimistic, now preachy. The treatment savours of Old Transpontia rather than the modern West-end, for the villain of the piece seems to have made up his mind not only that he must and will possess every woman for whom he has a “caprice,” but that if possible he will take possession there and then. A worse fault is that the play is ill-constructed—in the sense that more than usual has to be taken for granted. One incident—(of which more anon)—cannot be taken at any price nor with any amount of salt. To set against these defects “The Sixth Commandment” contains at least three very fine dramatic situations. There would be a fourth but that it is turned into an anticlimax by unnecessary cackle. Church and Stage have been so much mixed of late that I expected to find more general knowledge of “the argument”—so far, that is, as it could be inferred from the play’s title. Many were vague on this point. They knew the scene was Russian, but were not solid on the Decalogue as arranged for the Greek Church. Of course all good Refereaders are aware that the Anglican and Greek Churches run their Commandments in the same order. Those who hoped the Roman arrangement was in question were doomed to disappointment, for murder and not “immorality” is the play’s leading motive. At the same time, as I will endeavour to show, nobody who had expected it was about the Roman Catholic sixth commandment need be in the least way disappointed, as there is quite as much of “Thou shalt not” do one thing as there is about “Thou shalt not” do the other thing in “The Sixth Commandment.” The murder is done in the first act, and here is how it comes about.

Fedor is a discontented student who, being very hard up, hates the world in general and the rich Prince Zosimoff in particular, because Z. seeks to marry Anna (Fedor’s sister), who is beloved by Alexis (Fedor’s friend). Zosimoff is a terrible fellow among the women. Incidentally you hear of the body of one of his victims floating down the Neva, and a few minutes later Fedor’s sweetheart, the workgirl Liza, is seen fleeing from Zosimoff’s unwelcome embraces. Of course Fedor occurs fortuitously, which is as well, for it seems part of the duties of the Petersburg police to pimp for Zosimoff. Liza lives with her mother and a sick sister in a hovel, L., the walls of which are so thin that you can see and hear through them. Abramoff, the Jew moneylender, lives up some steps, R. He is their landlord, and if the rent isn’t paid to-morrow morning —— you know the rest. Fedor is stone broke, but he can and will pawn his sister’s portrait. Exit Fedor to fetch portrait. Enter now the indefatigable Zosimoff. He orders the Jew to send Liza up to the palace this evening—just for all the world as though Abramoff were a confectioner and Liza a mere tart. Jew puts screw on with such force, and sick-sister agony is piled so high, that poor Liza rushes off to the palace in despair and with her back-hair down. Fedor, returning to pawn portrait, learns from garrulous Jew details of Lisa incident, drags Abramoff up his own steps, and incontinently chokes him. Remorse (or funk) of Fedor, and hasty exit. Liza’s mother now comes out to make last appeal to cruel landlord, and finding him dead raises neighbourhood with her cries. Petersburg is both well-policed and well-parsoned, for in two minutes not only are the police in possession of the house, but a local “pope” or archimandrite or something, with an acolyte and four sturdy choristers, in black drain-pipe hats, turns up and starts chanting a solemn dirge over the body of the dead Jew. (What price the anti-Semitic agitation in Russia after this?) While Fedor hides round the corner, enter to him Alexis, with a letter. Fedor’s uncle is dead, and Fedor, now a count, has inherited countless (or, rather, the late count’s) millions! “My God! too late! too late!” Curtain.

Of course Zosimoff divines that Fedor killed the Jew, and equally of course he uses his discovery for his own ends. Anna, now rich, repudiates her promise to marry Zosimoff, and declares for Alexis, but on Zosimoff quietly hinting that if she does not fulfil her promise he will denounce her brother, Anna wilts, and the process affords another effective curtain. In the third act a good situation is obtained by illegitimate means. The scene represents two rooms in a common lodging-house. Liza (who is in better fettle since her evening at “the palace”) and her mother and sister occupy one; a laundress lives in the other, but is presently chucked by Zosimoff’s police. Zosimoff knows that Fedor will come to Liza, and that he will confide in her and confess the murder. Nobody told Z., but he knows. Anna hates Z. far worse than ordinary poison; nevertheless she accompanies him to the room which adjoins Liza’s in order to discover what takes place next door. That is to say, Anna, high-born and virtuous, has come with a man she hates, to look upon or listen to what the brother she loves does in private with a young woman of the people. This is indeed singular; but all I can do, and all you can do, is to take the scene as it is presented. Presently enter Fedor. Liza and Fedor rush into each other’s arms. Instantly they break away, in accordance with Queensberry ruling. “Don’t touch me!” says Liza; “I am polluted!” “And I,” says Fedor—“I have the brand of Cain upon my brow—I am a murderer!” Anna, who has listened in agony, faints and falls as the curtain descends, Zosimoff meanwhile gloating fiendishly. It is a fine effect, but it is obtained by impossible means. In the fourth act, Z. the irrepressible having now got the bulge on Anna, makes her (as the price of her brother’s safety) once more promise to be Princess Z. Fedor disdains to be saved on such terms, and the curtain should fall upon his declaration, but Anna on her own account makes a little speech, which proves nothing, and spoils the effect. (It was 11.5 p.m. on Wednesday before this point was reached.) In the last act all concerned turn up at a military outpost “on the borders of Siberia,” with selections from “Moths,” “Called Back,” and other Russian romances. Fedor has been so good and has saved so many lives that he is allowed to come up out of the mine once a week, “to do menial service in the governor’s house” and (I suppose) save an odd life or so if he can. Much agony is piled up with Cossacks and prisoners. Anna and Alexis are not married yet, but they have travelled to Siberia together to have a look at Fedor. Zosimoff is soon on hand, and promptly orders Alexis to be cast into prison, in order that he (Z.) may at once possess Anna. She has a revolver—fires at him, misses, and in her agitation drops the weapon. Z. (ever polite) picks it up, presents it to her, asks her to take another shot, and warns her what will happen if she fails. Anna is really no use with pistols, and I don’t know what would have happened if at that moment Fedor had not rushed in and “downed” the villain. It would have gone hard with Fedor when Zosimoff got up, but at that moment a courier of the Czar arrived with a free pardon for Fedor and Siberia till further orders for Zosimoff. It seems that a good old comic policeman who pervaded every act had written to the Czar and told him all about it. Besides, his Majesty must by this time have been almost as tired of the villain’s goings-on as were the audience. Time, 11.45.

The actors were called and applauded warmly. On the author being called. the curtain rose again, and discovered Buchanan in the midst of the company. Applause and groans now ruled about equal. The play is well mounted and splendidly staged. The best played part in the piece is the villain, Zosimoff, as represented by Herbert Waring—cynical, polished, strong—perfect all the time. Lewis Waller is very earnest as Fedor, and at his best is very good indeed; but the performance is unequal. Miss Wallis was both intense and pathetic as Anna. Miss E. Robins represented the hapless Liza with tender impressiveness and excellent effect. William Herbert as an English attaché, and Miss Marion Lea as a somewhat hoydenish young Russian demoiselle, supplied the light-comedy element, which was none too strong, though for that they were not to blame. “Mons.” Marius was acceptable as he good old comic policeman, and deserves a word besides for his admirable stage management. Miss Maude Brennan, Miss Cowen, and Messrs. R. Stockton and De Lange did well in minor parts.

___

The People (12 October, 1890 - p.6)

SHAFTESBURY.

It cannot be said that Mrs. Lancaster-Wallis has been happy in the play selected by her for production on resuming the management of her own theatre last Wednesday. In “The Sixth Commandment,” the piece in question, founded by the fecund playwright, Mr. Robert Buchanan, on a Russian story, the audience were made to sup full of horrors upon dramatic fare so unpalatable as to cause a strong protest against it when the curtain finally fell. If the action of the piece really is, as it pretends to be, an undistorted reflex of the Russian life and society of to-day, heaven help the wretched subjects of the Czar!—it is no wonder they become Nihilists. A certain Prince Zosimoff, young in years but old in crime, is presented as a fiend incarnate, who outrages women, packs off men to Siberia, forces the lady who loathes him, to become his wife, suborns the chief of police to his murderous designs, and all this is done with the perfect immunity of an irresponsible autocrat until it is necessary to close the nauseous action of the play, when it occurs to one of the polished villain’s victims to appeal to the Czar, who immediately orders the inhuman monster into custody and, at the same time, releases the sufferers from his malignant cruelty and lust. But why this appeal, since it proves so suddenly efficacious, is not resorted to in the first instance, is not explained; only in that case, of course, there would be no play, which, as the event proved, would have been an advantage to all concerned, and particularly to the management. To recite the plot of this grisly melodrama would offend the reader, as it did the audience; besides, it would be a mere waste of time, as well as patience, since it is next to impossible that the piece can retain its place in the bill longer than may be found necessary to prepare a fresh production. It was pitiful to see such capable histrionic exponents of character as Messrs. Herbert Waring, Marius, Lewis Waller, and William Herbert, with the Misses Marian Lea, Maude Brennan, E. Robins, and Mrs. Lancaster herself, wasting their talents upon such fustian, which lasted through four mortal hours. In answer to an ironical call for the author, Mr. Buchanan appeared, not alone, as customary, but surrounded by the dramatic company, whose presence, however, did not save him from the storm of hooting deservedly raised against so thoroughly bad a play.

___

The Sheffield Daily Telegraph (13 October, 1890 - p.4)

LONDON LETTER.