|

HARRIETT JAY - SHORT STORIES AND ARTICLES

1. How Andy Beg Became A Fairy

2. An Irish Idyll

3. “What is the most striking incident in your professional experience?”

4. How Actresses Work

5. My Luggage

How Andy Beg Became A Fairy

The London Magazine (December, 1875 - Volume I, No. II, pp. 81-91).

AN IRISH CHRISTMAS CAROL.

HOW ANDY BEG BECAME A FAIRY:

BY THE AUTHOR OF “THE QUEEN OF CONNAUGHT.”

“DID you ever get sight of it yerself, Cuileagh, when you were passing Rhuna Hanish on a Christmas night like this, on your way to the chapel to hear the midnight Mass?”

“Get sight of it? Troth, then, I never did; and ’tis aisy seeing that same, for sure, then, if I had got sight of it, ’tis not here I’d be sitting now, but I’d be lying in my grave as dead as—as—as—” and finding himself unable to discover a simile, the speaker bent over the fire, squeezed some burning ashes into his pipe- bowl, and began puffing vigorously.

He was a short, thick-set man, with little prepossessing in his appearance. His face was, at first sight, hard and most repelling; and this, his neighbours said, was the true index to his character. Cuileagh Clanmorris was a most unpopular man in Storport. Instead of mixing with his fellows and showing his face at fairs and weddings and wakes, he worked like any beast of burden all the year, and on Sundays and feast-days, and at Christmas tide, when he had a few hours to spare, instead of enjoying his leisure as a mortal should do merely stepped into his neighbour Dunloe’s, and smoked his pipe in the ingle, and told weird stories and fairy legends to that child, which, as the population would have it, was no human child, “but only a bit of a fairy itself.”

And, in sooth, there was something about little Andy, or, as he was called in Irish, Andy Beg, which was extremely fairy-like and weird—a strange, old-fashioned wonder and wisdom, which had convinced the peasantry, and some of the child’s relatives too, that he was no ordinary being. He was an only child. His mother was the Widow Dunloe, who had lived all her life in Storport; and who since that night when Manus Dunloe had lost his life off the Rhuna Hanish, had dwelt in the little cabin on the beach, with only her father and Andy.

Andy was eight years old, yet he had none of a child’s ways, and no desire for childish companionship. The being for whom he cared most was his grandfather, an old man of ninety years, who habitually sat in the ingle, with his grey head bowed, and his bony hands clasped upon his knees, in a state of mental torpor, from which, it seemed at times, an earthquake could not have roused him, but who, at the slightest sound of Andy's voice, stirred and lived, his dull, heavy, lustreless eyes gleaming with a ray of human light. From the very first, these two had been drawn together by a strange fascination. Ever since the day when he first began to walk with some steadiness across the floor, Andy had taken his stand between his grandfather’s knees, had prattled to him in that strange, old-fashioned way of his, had attended to him assiduously in all his wants, until, as time went on, the child’s life seemed to get interwoven, as it were, with that of the old man, and at length, to the wonder of all, it was discovered that he who, during his life, had been singularly hard, callous, and cruel, had got all his affections aroused by this quaint little companion of his old age.

He was very old-fashioned, was Andy Beg; he had a pleading, pinched look in his face, and a strange light in his eyes, and a quiet, unchildlike gentleness in his voice, which aroused the darkest fears in his mother’s breast. He was not meant for this world, she said, but he was a little fairy, with a human voice, and human eyes, and maybe a human soul; he had come to them, and had been a blessing to them, but he was surely not destined to stay.

Andy Beg was not a strong child. Once or twice during his short life he had been stricken down, and had lain at death’s door; and at those times the old man had awakened from his torpor, and had sat beside the bed, with his dull eyes fixed in agony, as if his life hung upon the child’s breath. But Andy had recovered from these attacks, and had taken his place again between his grandfather’s knees, his face a little more pinched and worn, his eyes shining a little more brightly, his voice chiming with a still more pathetic ring.

The child’s face had never looked so old and strange as it did on that Christmas night when, standing between his grandfather’s knees, with his small white fingers resting upon the bony hands of the old man, and his cheek pressed against his sleeve, he had fixed those luminous eyes of his upon the grim countenance of Cuileagh Clanmorris, and asked him to tell him of the fairy maidens who tended their flocks on Christmas night on the Isle na Creag—that spot of green which was supposed to be visible every year an hour before midnight Mass.

Cuileagh Clanmorris puffed hard at his pipe, and between each puff he gazed more fixedly at the child, and, as he did so, the hard expression of his face grew tenderer, and the heavy clouds of smoke more dense. A shade of disappointment stole over Andy’s face as he listened to the grim man’s speech, and the little white hand began beating upon the bony fingers of his grandfather.

“Sure I thought you had seen it, Cuileagh?”

“Not I, in troth, but ’tis often I heard tell of it.”

For a moment the child stood with his eyes fixed meditatively upon the glowing turf sods; then suddenly he turned round, gently opened the old man’s coat, and dived his small hand deep into a pocket in the inside. This pocket was the child’s special property; it was solely appropriated to his use, no hands but his ever slipped into it and brought to light the strange medley of things with which it was filled. Andy knew exactly what was there. He could count on his fingers the number of stones he had, which served him as marbles; he knew the exact length of the string which wound his top—and the top, too, was there—the one which Cuileagh Clanmorris had brought him that time he went to Storport fair. They were safe there, Andy knew: no one but himself would dare to rifle the old man’s coat pockets; and the old man himself, why he was merely a peg on which the coat hung, although, if occasion required, he guarded Andy’s property with jealous ferocity. So on this occasion the child was pretty sure of finding the treasure he sought. His hand dived to the bottom, then it emerged, holding tightly a piece of white loaf bread.

“Sure, I will give you this, if you will tell what you know to me and grandfather.” And he held forth the bread as an inducement.

In the little village of Storport, situated as it was far away in the wilds on the north-west coast of Ireland, white bread was a luxury which the peasantry seldom saw, and seldom or never ate; so, on this occasion, Andy attached to it as much importance as a southern child would do to an apple, a bonbon, or any other delicacy.

The grim features of Cuileagh Clanmorris relaxed into a smile. He drew his pipe from his mouth, knocked out the ashes upon the hearth-stone, leaned his elbows upon his knees, and looked into Andy’s face.

“Ate yer bread, Andy eroo, sure I’ll tell ye what I know without the likes of that!” And Andy drew back softly with a brighter face, and began munching the bread, and rubbed his cheek against the old man’s sleeve and patted his hand, and added, softly, “And you will tell grandfather, too?”—while the old man, who had been aroused by the sound of the child’s voice, murmured quietly, in a mumbling, half-sleepy tone, “Aye, aye,” and dozed off again.

It was a Christmas night. Outside on the hills the snow gleamed and the chilly wind blew, and when the voices were still, the room was filled with a soft low music floating up from the sea, which washed upon the shingle scarce a hundred yards from the cabin door. Here and there on the hills dark figures flitted along, leaving long tracks behind them in the snow as they passed along towards the chapel to hear Father Tom say midnight mass. The wind which blew softly scattered the snow, and ruffled the surface of the sea.

Andy Beg was fortunate so far as he was spared the misery attendant upon wintry weather and cheerless Christmas nights. A bright firelight played upon him and warmed him, and illuminated his pale, pinched little face as he stood between his grandfather’s knees with his eyes fixed upon Cuileagh, waiting for the tale.

“’Tis often I heard tell of it,” said Cuileagh, bending forward as was his wont, and puffing hard at his short clay pipe; “’tis often I heard tell of it, but whether ’tis true or not, none but the Holy Virgin herself can tell. They’re sayin’ it rises up from the say there first before midnight mass. ’Tis a lovely island, they tell, with trees and grass and flowers and streams, and in every one of them flowers there’s a fairy, and in every one o’ them streams there’s a score o’ them, and under the trees there’s a herd of cattle grazing, and a fairy colleen watching them and singing the while. And that herd of cattle,” continued Cuileagh, lowering his voice to an awful whisper, “is a herd of mortal men.”

“Well, well!” said Andy, fixing his eyes in astonishment, “and how did they come there at all?”

“The Lord knows!” returned Cuileagh solemnly; “but ’tis said they were passing along the say-shore on a Christmas night, when they seen the Island itself and the fairies dancing and capering about, and they laughed and clapped their hands, and for this they were made fairies, and on Christmas night they were turned to a herd of cattle as a punishment, and since then no mortal man has ever looked on it, and if he does, ’tis a sure sign that ’tis dead he’ll be before the year is out, and the fairies will take his soul, and tho’ ’tis a grand place, sure ’tis only fit for the likes o’ them, but not for mortal men.” So saying, he puffed more vigorously than before.

For a few moments Andy stood silent, looking into the fire; then he turned his little pale face, with the fire’s red glow upon it, and gazed into Cuileagh’s dark eyes.

“Will I go there, Cuileagh?” he asked; and added softly, “and will grandfather go too?”

“The Lord forbid!” said Cuileagh as he reverently crossed his breast. '”Sure you wouldn’t wish to go to the fairies, Andy Beg, and as to your grandfather there, why the Blessed Virgin herself will take him when ’tis time!”

“Will she?” said Andy, opening his eyes. “Then, maybe, she will take me too. Grandfather wouldn’t go alone, would you, granny?”

He looked wistfully into the old man’s face; he found no gleam of light there, but he saw the grey head shake slowly.

Andy felt ever so little disappointed that night. He would not leave his grandfather, not for worlds; if the old man went to the Virgin, why, of a necessity, Andy must go too;—but as he lay down to rest, he could not help thinking that he would much rather be going to the Fairy Island, to hear the fairies singing, and to watch the shining sea.

II.

ALL the world seemed white; the mountains were white, covered deep in snow, and the streams and tarns were frozen to crystal ice; and before all stretched the sea like a glittering glassy mirror sparkling in the light.

As Andy stood knee-deep in the snow and looked around him, his eyes got dazzled with so much brightness. He did not know how he got there; he did not know why he had come; he did not know where he was even; he only knew that he stood alone in the snow away from his grandfather for the first time in his life.

The little fellow folded his arms to keep himself warm, and looked around again.

Behind him the hills stretched in long perspective; then they got mingled up confusedly, and then they turned into old men’s faces, and gazed at him through hoary hair. Andy felt a little frightened then, and looked at the sea. It still lay placid and mirrored; in its surface were innumerable stars reflected from the heavens above. Not a breath stirred; but as Andy stood looking he suddenly became aware that the air was filled with a soft, low, musical sound, like the humming of a thousand bees. Andy stood gazing and listening enraptured; then suddenly he found that his eyes were not resting upon the water at all, but upon a spot, a lovely green spot, set out yonder in the shining water. He looked again. It was an island, covered with long grass, and tall waving ferns, and bright silvern flowers, the scent of which was diffused into the sea breeze and wafted into his face; and he saw figures, bright little fairy figures, moving about amidst these green glades, and their faces—oh, so quaint and old, just like his own!—were turned towards him, and their eyes looked into his. The whole island was flooded with a bright light, which streamed down upon the grass, and the flowers, and the little fairy figures which moved about them. Then Andy’s eyes wandered on, and he saw a herd of cattle feeding beneath the trees; and he knew this must be the herd of which Cuileagh spoke, for there, quite near them, beneath the trees, sat the figure of a lovely colleen, singing softly, with her eyes downcast.

Then Andy began to think how much he would like to go there, into that cool and lovely place, and even as he thought so, the colleen rose, and turned towards him and beckoned with her white hand.

Andy stretched his hands out too, when suddenly he remembered that he was there alone: so he drew back again, and cried—

“I will come! but I must bring grandfather!”

He turned, and at that moment a great clang struck on his ear—a heavy, sonorous sound, like the ringing of bells—in the air flashes of light darted, and a cry was heard like a human voice. Then Andy felt frightened again, and looked behind him, and he saw the island glittering now like a ball of fire, and the tree tops waved, and the fairies danced; the cattle raised their heads and lowed softly in weary human voices, and as they did so, their heads turned to human heads, and their eyes looked straight into Andy’s, while slowly the island split in two, and sank softly beneath the water.

Andy opened his eyes, and found he was lying in his bed, with the full cold light of a Christmas morning streaming in his face; the chapel bells he heard were ringing for early Mass. He looked around, but he was alone. He never would sleep with his grandfather. The old man looked so hideous and skeletonian in his night gear—his sunken cheeks and hollow eyes were made so ghastly by a hideous night-cap—that, much as Andy loved him he never could trust himself to gaze upon him in this condition. So, instead of running to his grandfather’s bedside, and telling him of his dream, he lay quite still, and tried to dream it all over again.

But when at length he was up, and again standing between his grandfather’s knees, he looked questioningly into his face.

“Grandfather,” he said, “is it to the Fairy Island you would wish to go, or to the Blessed Virgin herself?”

The old man looked at him for a time bewildered, then he said slowly,

“Sure all good Christians go to the Virgin, and why wouldn’t I go entirely?”

“Because,” said Andy softly, and his face grew more old-fashioned as he spoke, “because, grandfather, ’tis to the Fairy Island I am going, and I want you to come too!”

III.

From that day Andy began to change. His face grew more pinched and white, his eyes more luminous, and his manner more old-fashioned and strange. He still stood between his grandfather’s knees as he used to do, and attended to the old man’s wants, but his voice was sometimes a little peevish now, and he would not speak much to those who were about him. He seemed to become so discontented at times, that his mother looked at him, wondering what could be the matter with the child. Andy had always been sickly and white, but he had never been peevish before, he had always taken all that was given to him with a good grace. Now he turned pettishly from his food.

“Mother,” he said one day, “why is it that I must eat stirabout?”

“Sure, you know we have nothing else in the house to give you, Andy, eroo,” his mother replied.

“Sure then I know that same,” said Andy, “but if ’twas on the Fairy Island I was, they would give me white bread!”

His mother crossed herself.

“Never name them, Andy bawn. You know you are a Christian child!”

But Andy replied,

“Maybe I shall be a fairy some day for all that!”

There was something very wrong with the boy, but what that something was none could determine. His mother looked at him again and again with an anxious scrutinizing gaze, but she could discover nothing. Cuileagh Clanmorris came night after night, and smoked his pipe in the ingle, and looked into Andy’s face with those keen penetrating eyes of his, and as he did so his thoughts, almost in spite of himself, travelled back to that Christmas only a few months gone by, when he had told the child the fairy legend, and when Andy himself had slept and seen fairy-land. Cuileagh Clanmorris was superstitious, as were most of the peasantry of Storport, and as he thought over these things he shuddered—for this hard-working, coarse-natured man had come to love the quaint little old-fashioned child. Night after night now he brought with him lumps of white bread and gave them to Andy, and as the child stood between his grandfather’s knees and munched at the bread, Cuileagh tried to tell him other stories to divert his mind. But Andy took no interest in any but one thing, his thoughts constantly reverted to the old theme.

“I wonder,” he said one night as he looked into Cuileagh’s face and munched at Cuileagh’s bread, “I wonder if fairies always eat bread like this same!”

“Maybe,” answered Cuileagh; “they’re dainty people, they’re sayin’, and fond o’ swate things.”

“Then surely,” continued the child, “they would give me bread too?”

“If ye were a fairy!”

“And grandfather?”

“Aye, aye,” murmured the old man, and he nodded his head and looked at the child with a vacant gaze, while Cuileagh murmured to himself, “Maybe ’tis a fairy that he is afther all.”

More and more pathetic grew that little pinched face of Andy’s; yet the paler his cheeks became, the more peevish he seemed to grow. There was something very wrong indeed, for once or twice Andy spoke even to his grandfather in a querulous tone. The old man was dimly conscious of the change, though he was yet too dull to perceive exactly what was amiss. He looked into the child’s face with a pained, questioning glance, whereon Andy grew gentle again as ever, and rubbed his soft cheek against the old man’s sleeve, and patted his bony hand, while the tears slowly gathered in his eyes.

The winter passed thus, and as each month rolled away, and the snow was melted from the ground, and the sun shone upon the hills, Andy’s face grew whiter and whiter; and when summer came he lay in a little cot by the kitchen fire close to his grandfather’s side. He lay there and thought and thought as he looked into the fire, or listened to the monotonous washing of the sea. His peevishness seemed partly gone now, and he grew quiet and gentle and kind as his custom was. Oh yes, he was quite like his old self now, though he looked so pinched and old, and his little white hands were as thin and transparent as his grandfather’s. Lifeless as the old man generally appeared, he now grew dimly conscious of what was happening, and his dull heavy lustreless eyes brightened into something like life as he watched Andy’s face. He seemed to feel that a chilly hand was drawing the child away, and he began to half realize what the loss would be to him. Andy could not understand all this; he was too young. He had been so long with his grandfather that he did not dream of parting; they seemed to breathe together. His grandfather would never leave him, he thought; and as to himself, why, if he became a fairy, grandfather must become a fairy too, and as he lay in his cot day after day, with the summer sunshine streaming full upon him, he thought and wondered over all these things.

“Cuileagh,” he said one day, when Cuileagh had strolled in to sit beside him, “are they all little people that live in the Fairy Island.?”

“Yes, sure,” said Cuileagh gruffly.

“Then must everybody get small before they go?”

“Maybe; but what for do ye ask that, Andy bawn?”

“Because I was wondering how grandfather will get there. He is so big, you know!”

“Sure ’tis not there he will go at all—the Holy Virgin forbid! Never spake of it again, Andy astore.”

And Andy never did speak of it again, but he lay in his cot and grew weaker and weaker, until at last he seemed to fade away, and his spirit broke loose and went to the Fairy Land.

They laid him out in his Sunday’s best, and the neighbours flocked in to look upon the small white face and sunken cheeks. Grandfather sat beside the bed holding in his bony fingers the child’s clay cold hands, and gazing upon him with a stupefied despair. As he sat there—only dully comprehending what had taken place, only faintly feeling his loss as yet—too senile to understand that Andy had gone from him for ever, he saw the people come and go like the waves of a living sea, and as each person came up with a strange face to gaze upon the small, pinched, pleading face of the child, he heard the same words ringing in his ears,

“Sure I always knew he was a fairy, and so he’s gone to the fairies at last!”

IV.

THE house was very dull when Andy was taken away. Though he had ever been a quiet child, his very presence seemed to bring light and life with it. But now the merest foot-fall echoed strangely through the room, and the roaring of the sea was ever heard, and the chilly whistling of the wind. For the summer which had taken Andy away had faded away too, and another Christmas was drawing nigh. They had all missed Andy, and they had all said so—but one—his grandfather.

The old man lived still. He had made no mention of the child. With tearless eyes he had watched them take him away, and then he had resumed his old seat in the ingle. There he sat, day after day, like a heavy lifeless log; he never opened his eyes to speak, he never raised his head to look around, and he never asked for Andy, but his bony hands were clasped upon his knees—and his knees were always apart as if Andy stood between them.

He never smoked now, because there was no Andy to light his pipe; he seldom took food, because the child was not there to give and share it. He never spoke of Andy, and they thought he had forgotten him entirely.

But one day as he sat there apparently lifeless, he suddenly raised his thin bony hand, and put it into the inside pocket of his coat—Andy’s pocket—and drew forth the treasures Andy had left: a small piece of white bread, dried now hard as any stone, some pieces of string, and coloured stones and shells. These he held in his hand and gazed at with a heavy, stupefied gaze; then his fingers closed over them again, and they were put back into Andy’s pocket to wait for Andy’s coming.

The old man often repeated this, but the treasures were sacred from the touch of any other human hand.

Christmas night swept round again, and the peasantry of Storport hurried over the snow-clad hills to hear the midnight mass. In the widow Dunloe’s cabin there was no rejoicing. The sea still washed at the door with that dreary sound which had called Andy away. The widow Dunloe sat silent, thinking of the Christmas night twelve months before, when Andy had stood between his grandfather’s knees, and listened to the fairy tale. Cuileagh Clanmorris was near the fire smoking hard, but saying no word, and grandfather sat in his usual way with bowed head and closed eyes. The old man was not thinking of Andy, he was now almost too senile to think at all; but he had closed his eyes and fallen into a doze.

As he sat thus, something startled him. He opened his eyes, and there he saw standing between his knees, invisible to all eyes save his own, a little bright figure, rubbing its cheek against his sleeve and patting his hand, just like Andy used to do!

As the old man looked, the figure turned, and a little face was raised up to his. It was Andy’s face, grown whiter. The old man looked again. Sure enough it was Andy! There he stood, just as he had stood a year ago, and he looked almost the same. His face was pinched and worn and white, as it had been, but his little cheeks and hands were thinner, and his eyes more luminous.

He stood for a moment between his grandfather’s knees, with his eyes fixed upon the fire.

Then, still without speaking a word, he turned, gently pulled open his grandfather’s coat, and put his hand into the pocket, and drew forth that hard dried piece of white bread, and held it in his hand—then with the other he seized the old man’s coat.

“Come along, grandfather, come along!” he said, in his old pathetic voice.

The old man half rose from his seat, and looked around wildly with dazed, heavy eyes. “Aye, aye,” he murmured; then he sank down in his seat again, his eyes closed, and his head drooped upon his breast.! . . .

When the Christmas bells rang out with a heavy clang for midnight they found grandfather sitting in his chair—quite dead! His head had fallen forward, his bony hands hung beside him, and on the floor at his feet lay the crust of bread which Andy had left. Perhaps his spirit had gone from the earth to join Andy on the Fairy Island in the Sea.

[Note: Jay later included this story in Vol. 3 of My Connaught Cousins, published in 1883.]

_____

An Irish Idyll

Belgravia (April 1879 - pp. 199-206).

An Irish Idyll.

BY THE AUTHOR OF ‘THE QUEEN OF CONNAUGHT.’

WE had been out all night watching the herring-fishers; but as soon as the work was over, and the faint glimmering of dawn appeared in the east, we turned our boat’s bow towards the shore, and pulled swiftly homewards. There lay the group of curraghs, still upon the scene of their labour, loaded with phosphorescent fish and dripping nets, and manned with crews of shivering weary men. The sea, which during the night had been throbbing convulsively, was calm and bright as a polished mirror, while the gaunt grey cliffs were faintly shadowed forth by the lustrous light of the moon.

Wearied with my night’s labour I lay listlessly in the stern of the boat, listening dreamily to the measured splash, splash, of the oars, and drinking in the beauty of the scene around me: the placid sea, the black outline of the hills and cliffs, the silently sleeping village of Storport. Presently, however, my ears detected another sound, which came faintly across the water, and mingled softly with the monotonous splashing of the oars and the weary washing of the sea.

‘Is it a mermaid singing?’ I asked sleepily. ‘The village maidens are all dreaming of their lovers at this hour, but the Midian Maras sing of theirs. Oh, yes, it must be a mermaid, for hark! the sound is issuing from the shore yonder, and surely no human being ever possessed a voice half so beautiful!’

To my question no one vouchsafed a reply, so I lay still half-sleepily and listened to the plaintive wailing of the voice, which every moment grew stronger. It came across the water like the low sweet sound of an Æolian harp touched by the summer breeze; and as the boat glided swiftly on, bringing it ever nearer, the whole scene around seemed suddenly to brighten as if from the touch of a magical hand. Above me sailed the moon, scattering pale vitreous light around her, and touching with her cool white hand the mellow thatched cabins, lying so secluded on the hillside, the long stretch of shimmering sand, the fringe of foam upon the shingle, the peaks of the hills which stood silhouetted against the pale grey sky.

A white owl passing across the boat, and almost brushing my cheek with its wing, aroused me at length from my torpor. The sound of the voice had ceased. Above my head a flock of seagulls screamed, and, as they sailed away, I heard the whistle of the curlew; little puffins were floating thick as bees around us, wild rock-doves flew swiftly from the caverns, and beyond again the cormorants blackened the weed-covered rocks. The splash of our oars had for a moment created a commotion; presently all calmed down again, and again I heard the plaintive wailing of the mermaid’s voice. The voice, more musical than ever, was at length so distinct as to bring with it the words of the song:—

‘My Owen Bawn’s hair is of thread gold spun;

Of gold in the shadow, of light in the sun;

All curled in a coolun the bright tresses are,

They make his head radiant with beams like a star!

My Owen Bawn’s mantle is long and is wide,

To wrap me up safe from the storm by his side;

And I’d rather face snow-drift and winter wind there,

Than be among daisies and sunshine elsewhere.

My Owen Bawn Con is a bold fisherman,

He spears the strong salmon in midst of the Bann,

And, rocked in the tempest on stormy Lough Neagh,

Draws up the red trout through the bursting of spray.’

The voice suddenly ceased, and as it did so, I saw that the singer was a young girl who, with her hands clasped behind her and her face turned to the moonlit sky, walked slowly along the shore. Suddenly she paused, and while the sea kissed her bare feet, and the moon laid tremulous hands upon her head, began to sing again:

‘I have called my love, but he still sleeps on,

And his lips are as cold as clay:

I have kissed them o’er and o’er again—

I have pressed his cheek with my burning brow,

And I’ve watched o’er him all the day;

Is it then true that no more thou’lt smile

On Moina?

Art thou then lost to thy Moina?

I once had a lamb my love gave me,

As the mountain snow ’twas white;

Oh, how I loved it nobody knows!

I decked it each morn with the myrtle rose,

With “forget-me-not” at night.

My lover they slew, and they tore my lamb

From Moina.

They pierced the heart’s core of poor Moina!’

As the last words fell from her tremulous lips, and the echoes of the sweet voice faded far away across the sea, the boat gliding gently on ran her bow into the sand, and I, leaping out, came suddenly face to face with the loveliest vision I had ever beheld.

‘Is it a mermaid?’ I asked myself again, for surely I thought no human being could be half so lovely.

I saw a pale madonna-like face set in a wreath of golden hair, on which the moonlight brightened and darkened like the shadows on a wind-swept sea. Large lustrous eyes which gazed earnestly seaward, then filled with a strange wandering far-off look as they turned to my face. A young girl, clad in a peasant’s dress, with her bare feet washed reverently by the sighing sea; her half-parted lips kissed by the breeze which travelled slowly shoreward; her cheeks and neck were pale as alabaster, so were the little hands which were still clasped half nervously behind her; and as she stood, with her eyes wandering restlessly first to my face, then to the dim line of the horizon, the moon, brightening with sudden splendour, wrapt her from head to foot in a mantle of shimmering snow.

For a moment she stood gazing with a peculiar far-away look into my face; then with a sigh she turned away, and with her face still turned oceanward, her hands still clasped behind her, wandered slowly along the moonlit sands.

As she went, fading like a spirit amid the shadows, I heard again the low sweet sound of the plaintive voice which had come to me across the ocean, but soon it grew fainter and fainter until only the echoes were heard.

I turned to my boatman, who now stood waiting for me to depart.

‘Well, Shawn, is it a mermaid?’ I asked, smiling.

He gravely shook his head.

‘No, yer honour; ’tis only a poor Colleen wid a broken heart!’

I turned and looked questioningly at him, but he was gazing at the spot whence the figure of the girl had disappeared.

‘God Almighty, risht the dead!’ he said, reverently raising his hat, ‘but him that brought such luck to Norah O’Connell deserved His curse, God knows!’

This incident, coupled with the strange manner of my man, interested me, and I began to question him as to the story of the girl whose lovely face was still vividly before me. But for some reason or other he seemed to shun the subject, so for a time I too held my peace. But as soon as I found myself comfortably seated in the cosy parlour of the lodge, with a bright turf fire blazing before me and hot punch steaming on the table at my side, I summoned my henchman to my presence.

‘Now, Shawn,’ I said, holding forth a steaming goblet which made his eyes sparkle like two stars, ‘close the door, draw your chair up to the fire, drink off this, and tell me the story of the lovely Colleen whom we saw to-night.’

‘Would yer honour really like to hear?

‘I would; it will give me something to dream about, and prevent me from thinking too much of her beautiful face.’

Shawn smiled gravely.

‘Yer honour thinks her pretty? Well, then, ye’ll believe me when I tell ye that if ye was to search the counthry at the present moment ye couldn’t find a Colleen to match Norah O’Connell. When she was born the neighbour’s thought she must be a fairy child, she was so pretty and small and white; and when she got older, there wasn’t a boy in Storport but would lay down his life for her. Boys wid fortunes and boys widout fortunes tried to get her; and, begging yer honour’s pardon, I went myself in wid the rest. But it went one way wid us all: Norah just smiled and said she did not want to marry. But one day, two years ago now come this Serapht, that lazy shaugrhaun Miles Doughty (God rest his soul!) came over from Ballygally, and going straight to Norah, widout making up any match at all, asked her to marry him.’

‘Well?’

‘Well, yer honour, this time Norah brightened up, and though she knew well enough that Miles was a dirty blackguard widout a penny in the world—though the old people said no, and there was plenty fortunes in Storport waitin’ on her—she just went against everyone of them and said she must marry Miles. The old people pulled against her at first, but at last Norah, with her smiles and pretty ways, won over Father Tom—who won over the old people, till at last they said that if Miles would go for a while to the black pits of Pennsylvania and earn the money and buy a house and a bit of land, he should marry her.’

He paused, and for a time there was silence. Shawn looked thoughtfully into the fire; I lay back in my easy-chair and carelessly watched the smoke which curled from my cigar, and as I did so I seemed to hear again the wildly plaintive voice of the girl as I had heard it before that night:

I have called my love, but he still sleeps on,

And his lips are as cold as clay:

and as the words of the song passed through my mind, they seemed to tell me the sequel of the story.

‘Another case of disastrous true love,’ I said, turning to Shawn; and when he looked puzzled I added, ‘He died, and she is mourning him?’

‘Yes, yer honour, he died; but if that was all he did, we would forgive him. What broke the poor Colleen’s heart was that he should forget her when he got to the strange land, and marry another Colleen at the time he should have married her; after that, it was but right that he should die.’

‘Did he write and tell her he was married?’

‘Write? devil the bit, nor to tell he was dead neither. Here was the poor Colleen watching and waiting for him, for two whole years, and wondering what could keep him; but a few months ago Owen Macgrath, a boy who had gone away from the village long ago on account of Norah refusing to marry him, came back again and told Norah that Miles was dead, and asked her to marry him. He had made lots of money, and was ready to take a house and a bit of land and to buy up cattle if she would but say the word to him.’

‘Well?’

‘Well, yer honour, Norah first shook her head and said that now Miles was dead ’twas as well for her to die too. At this Owen spoke out and asked where was the use of grieving so, since for many months before his death Miles had been a married man! Well, when Owen said this, Norah never spoke a single word, but her teeth set, and her lips and face went white and cold as clay, and ever since that day she has been so strange in her ways that some think she’s not right at all. On moonlight nights she creeps out of the house and walks by the sea singing them strange old songs, then she looks out as if expecting him to come to her—and right or wrong, she’ll never look at another man!’

As Shawn finished, the hall clock chimed five; the last spark faded from my cigar; the turf fell low in the grate: so I went to bed to think over the story alone.

During the three days which followed this midnight adventure, Storport was visited by a deluge of rain, but on the fourth morning I looked from my window to find the earth basking in summer sunshine. The sky was a vault of throbbing blue, flecked here and there with waves of summer cloud, the stretches of sand grew golden in the sun-rays, while the saturated hills were bright as if from the smiling of the sky. The sight revivified me, and as soon as my breakfast was over, I whistled up my dogs and strolled out into the air.

How bright and beautiful everything looked, after the heavy rain! The ground was spongy to the tread; the dew still lay heavily upon the heather and long grass; but the sun seemed to be sucking up the moisture from the bog. Everybody seemed to be out that day; and most people were busy. Old men drove heavily laden donkeys along the muddy road; young girls carried their creels of turf across the bog; and by the roadside, close to where I stood, the turf-cutters were busy.

I stood for a while and watched them at their work, and when I turned to go, I saw for the first time that I had not been alone. Not many yards from me stood a figure watching the turf-cutters too.

A young man dressed like a grotesque figure for a pantomime: with high boots, felt hat cocked rakishly over one eye, and a vest composed of all the colours of the rainbow. His big brown fingers were profusely bedecked with brass and steel rings, a massive brass chain swung from his waistcoat, and an equally showy pin adorned the scarf at his throat. When the turf-cutters, pausing suddenly in their work, gazed at him with wonder in their eyes, he gave a peculiar smile and asked with a strong Yankee accent if they could tell him where one Norah O’Connell lived: he was a stranger here, and brought her news from the States! In a moment a dozen fingers were outstretched to point him on, and the stranger, again smiling strangely to himself, swaggered away.

I stood for a time and watched him go, then I too sauntered on. I turned off from the road, crossed the bog, and made direct for the sea-shore.

I had been walking there for some quarter of an hour, when suddenly a huge shadow was flung across my path, and looking up again beheld the stranger. His hat was pushed back now, and saw for the first time that his face was handsome. His cheeks were bronzed and weather-beaten, but his features were finely formed, and on his head clustered a mass of curling chestnut hair. He was flushed as if with excitement; he cast me a hurried glance and disappeared.

Five minutes after, as I still stood wondering at the strange behaviour of the man, my ears were greeted with a shriek which pierced to my very heart. Running in the direction whence the sound proceeded, I reached the top of a neighbouring sand-hill, and gazing into the valley below me I again beheld the stranger. This time his head was bare—his arms were outstretched, and he held upon his breast the half-fainting form of the lovely girl whom I had last beheld in the moonlight. While I stood hesitating as to the utility of descending, I saw the girl gently withdraw herself from his arms, then, clasping her hands around his neck, fall sobbing on his breast.

‘Well, Shawn, what’s the news?’ I asked that night when Shawn rushed excitedly into my room. For a time he could tell me nothing, but by dint of a few well-applied questions I soon extracted from him the whole story. It amounted to this: that after working for two years like a galley-slave in the black pits of Pennsylvania, with nothing but the thought of Norah to help him on, Miles Doughty found himself with enough money to warrant his coming home; that he was about to return to Storport, when unfortunately, the day before his intended departure, a shaft in the coal-pit fell upon him and he was left for dead; that for many months he lay ill, but as soon as he was fit to travel he started for home. Arrived in Storport, he was astonished to find that no one knew him, and he was about to pass himself off as a friend of his own, when the news of his reported death and Norah’s sorrow so shocked him that he determined to make himself known at once.

‘And God help the villain that told her he was married,’ concluded Shawn, ‘for he swears he’ll kill him as soon as Norah—God bless her!—comes out o’ the fever that she’s in to-night.’

Just three months after that night, I found myself sitting in the hut where Norah O’Connell dwelt. The cabin was illuminated so brightly that it looked like a spot of fire upon the bog; the rooms in the house were crowded; and without, dark figures gathered as thick as bees in swarming-time. Miles Doughty, clad rather less gaudily than when I first beheld him, moved amidst the throng with bottle and glass, pausing now and again to look affectionately at Norah, who, decorated with her bridal flowers, was dancing with one of the straw men who had come to do honour to her marriage feast. When the dance was ended she came over and stood beside me.

‘Norah,’ I whispered, ‘do you remember that night when I heard you singing songs upon the sands?’

Her face flashed brightly upon me, then it grew grave,—then her eyes filled with tears.

‘My dear,’ I added, ‘I never meant to pain you. I only want you to sing a sequel to those songs to-night!’

She laughed lightly, then she spoke rapidly in Irish, and merrily sang the well-known lines:—

‘Oh, the marriage, the marriage,

With love and mo bouchal for me:

The ladies that ride in a carriage

Might envy my marriage to me.’

Then she was laughingly carried off to join in another dance.

I joined in the fun till midnight; then, though the merriment was still at its height, I quietly left the house and hastened home. As I left the cabin I stumbled across a figure which was hiding behind a turf-stack. By the light of my burning turf I recognised the features of Owen Macgrath. He slunk away when he saw me, and never since that night has he been seen in Storport.

[Note: Jay later adapted this story for the opening chapter of Vol. 2 of My Connaught Cousins, published in 1883.]

_____

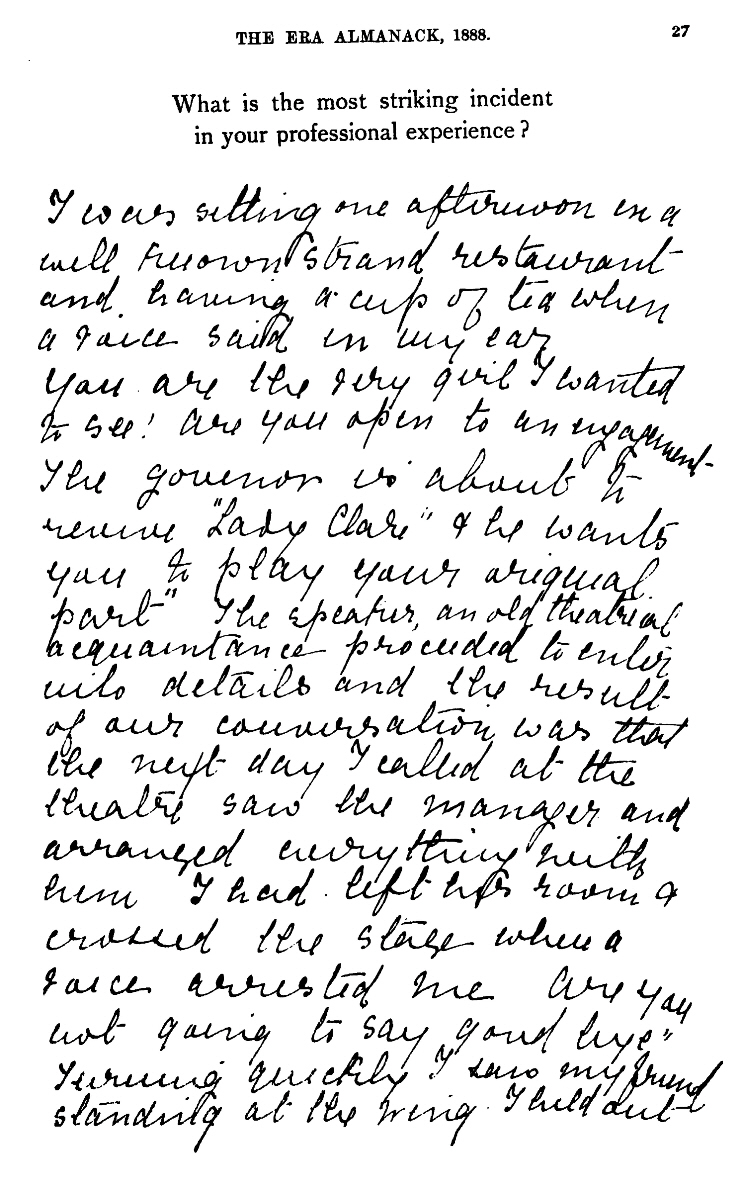

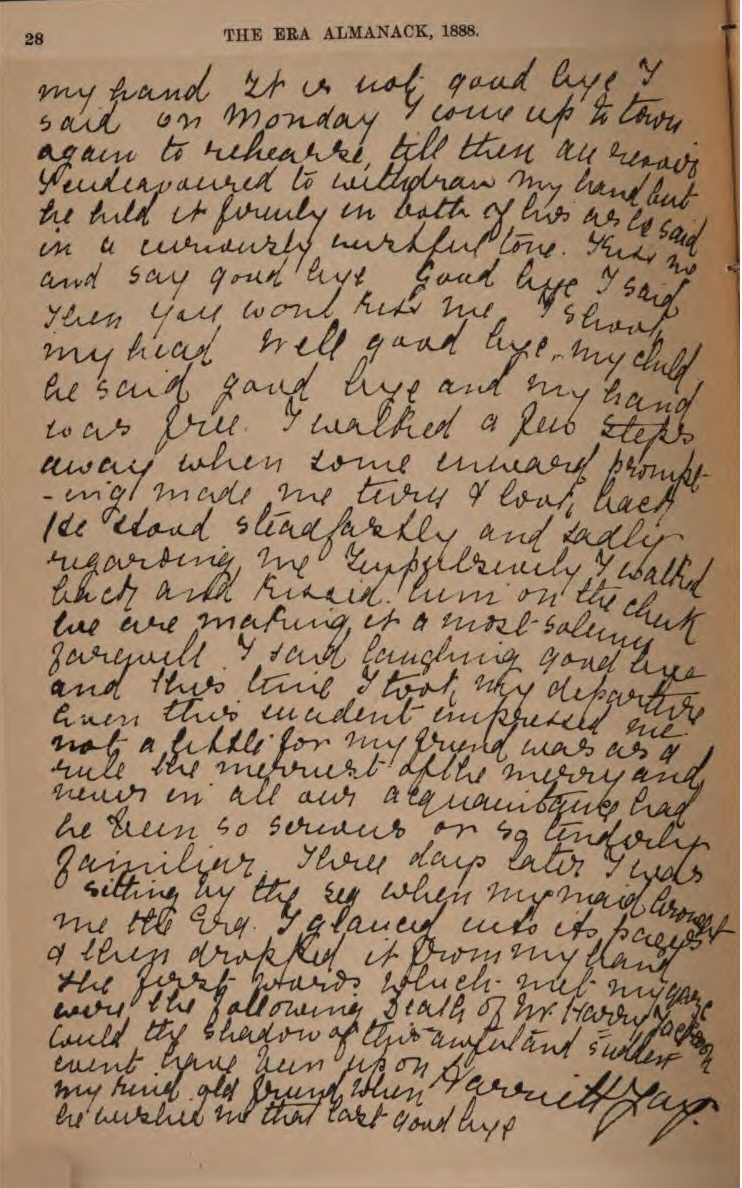

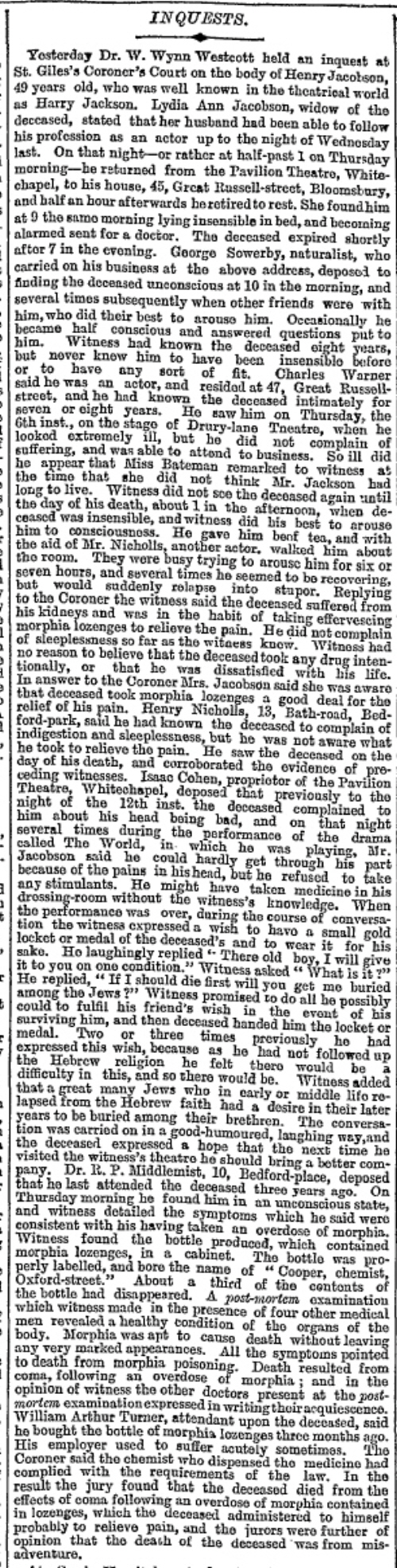

“What is the most striking incident in your professional experience?”

The Era Almanack (1888 - pp. 27-28).

|