|

Play List: 4. Corinne 7. The Mormons 9. Lucy Brandon 10. Storm-Beaten 11. Lady Clare 13. Bachelors 14. Constance 15. Lottie 16. Agnes 17. Alone in London 18. Sophia 19. Fascination 20. The Blue Bells of Scotland 21. Partners 24. Angelina! 25. The Old Home 26. A Man’s Shadow 27. Theodora 29. Clarissa 30. Miss Tomboy 32. Sweet Nancy 33. The English Rose 36. Marmion 37. The Gifted Lady 38. The Trumpet Call 39. Squire Kate 40. The White Rose 42. The Black Domino 44. The Charlatan 45. Dick Sheridan 47. Lady Gladys 48. The Strange Adventures of Miss Brown 49. The Romance of the Shopwalker 52. Two Little Maids from School ___ |

|

ROBERT WILLIAMS BUCHANAN (1841 - 1901) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

THEATRE REVIEWS 8. The Shadow of the Sword (1881)

The Shadow of the Sword *There was an exchange of letters between Buchanan and Coleman in The Era following the London premiere at the Olympic Theatre, which indicates that Coleman had a hand in the adaptation of Buchanan’s original draft.

The Stage (13 May, 1881 - p.5) Shadow of the Sword. FIRST PRODUCED AT THEATRE ROYAL, BRIGHTON, MAY 9TH. (FROM OUR OWN CORRESPONDENT.) Cynics who prophesied the decline of the drama were ignorant of the beautiful inspirations that the English stage possesses, and though the airing of Mr. Robert Buchanan’s romantic historical five act play, the Shadow of the Sword, occupied four hours on Monday evening, the audience, which filled every portion of the vast auditorium to excess, testified by their rapt attention and enthusiastic applause their admiration for a work that has more than histrionic claims on our sympathy, as it illustrates the horrors of war in a sensible and strong light and when a few judicious emendations are made Mr. Buchanan’s earliest contribution to the Gentleman’s Magazine will, as a play, add immensely to the popularity of the writer. The principal personages were vociferously called for at the close of each act, and hearty acknowledgements proclaimed the success of the drama when the curtain fell, close upon midnight, all present having remained till the climax. |

|

|

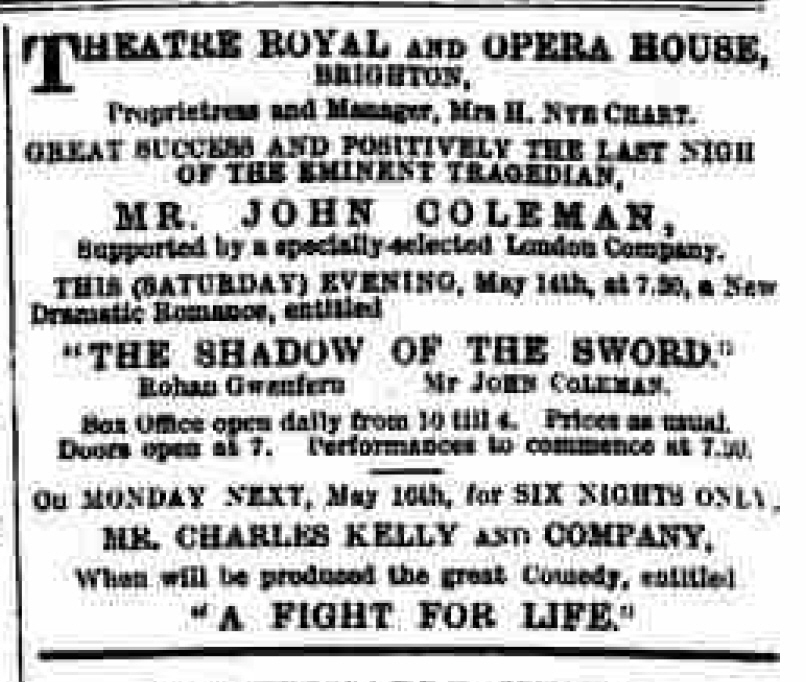

[Advert from The Brighton Herald (14 May, 1881 - p.2).]

The Era (14 May, 1881 - p.14) “THE SHADOW OF THE SWORD.” On Monday was produced, at the Theatre Royal, Brighton, Father Loiland . . . . . . . . . . . Mr F. HOPE MERISCORD The locale is fixed at Kromlax, a village on the coast of Brittany, which, at the rise of the curtain, is presented in a garb of snow, the time being Christmas Day. The principal characters are here introduced in succession. The widow Gwenfern, whose husband has been killed, and whose younger son Philip is still serving in the army, depends for support on her remaining son Rohan, a fisherman, who, for family reasons, is inveterate in his hatred of the “Little Corporal” and his continual warfare; Corporal Derval, a retired veteran, his uncle, being loud in his praise of Napoleon and his policy; Master Arfoll, schoolmaster, and Father Rolland, the village curé, preaching the doctrines of the Peace Society. An additional inducement to Rohan’s following a peaceful calling is his love for Marcelle Derval, and their love-making fills the greater portion of act one. The usual rival is found in Mickell Grallon, a wealthy fisherman, who perseveres in his pursuit throughout the piece. The closing incidents of act one are the return of Philip, wounded whilst deserting, his re- arrest, and the resistance offered by his brother Rohan to his capture. The Emperor and escort appear upon the scene, pardon for Philip is prayed, but refused, and the curtain falls to the sound of the shot that announced the deserter’s death. ___

The New York Times (4 June, 1881) . . . “The Shadow of the Sword” has been produced at Brighton. It was a most complete failure. Mr. Buchanan himself wrote it upon the lines of his novel, which is, in its way, quite a modern classic. ___

The Hull Packet and East Riding Times (2 September, 1881) THEATRE ROYAL. “THE SHADOW OF THE SWORD.” To fairly criticise, from a literary point, this work by Mr Robert Buchanan, would be to say that it is spoilt by its inequality of language. The dialogue, whilst full of poetic gems, is also marred by many disappointments, inasmuch as the auditor is carried along by the opening words of many speeches to expect a grandly effective climax, only to find a sorry commonplace. Looking at the previous writings of the talented poet, the student of dramatic literature will be the more grieved because of the above facts. A height of romance—which is a far different thing from melodrama—has been aimed at, but it must be confessed that in several instances there is a decided descent to the melodramatic. Whether this is due alone to the author’s lines, or to the elocutionary delivery of the chief artists, is a point which may be left in dispute. Mr Coleman is essentially a romantic actor, or was in his younger days, and the old temptation to heighten the effect of the text by tragic attitudes and fierce contortions of countenance is difficult to overcome, even when the most trivial of lines have to be uttered. An actor, above all persons, should have a keen sense of that fine distinction between the sublime and the other extreme. That much study has been bestowed upon the part of Rohan is evident, and there is no doubt that Mr Coleman, with his long experience and real ability, will, when the piece has reached a maturer age, tone down some of the high colouring which at present he gives to certain passages. Serious-minded poets, like Mr Buchanan, can seldom or never be frolicsome with the pen, and consequently the humour introduced into “The Shadow of the Sword,” is of but a hollow character. Mr H. Dalton as Gildas Derval, does justice to his comedy part, which is all the faint praise due. The introduction of a drunken character in a play always imparts an essence of vulgarity, and it is best, if the author decide on the introduction, to do it thoroughly, and make his temulentive creation of the old Eccles type. Mr Albert Lucas who seems scarcely “heavy” enough for the part of Grallon, gives an excellent reading of his lines. Miss Maud Brennan, has won many admirers for her pourtrayal of Marcelle; and Miss Clarissa Ash, with charming naiveté plays the semi-humourous part of Guinevere, the sweetheart of the drunken peasant. The rest of the company call for no special mention. “The Guv’nor” occupies the theatre next week, and those who, on the last visit, missed a hearty laugh, must take advantage of this opportunity. Mr David James and his Vaudeville company follow, to be succeeded by Mr Charles Kelly, from whom something “legitimate” may naturally be expected. In September Madame Modjeska arrives, and to complete the attractions already arranged for may be mentioned “Les Cloches de Corneville,” and a re- production of “The Galley Slave.” This tempting bill of fare will keep theatregoers interested for some time to come. |

||||

|

||||

|

||||

|

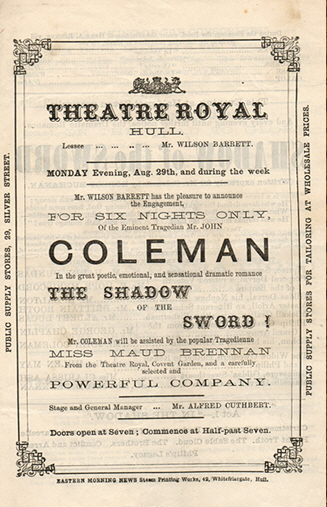

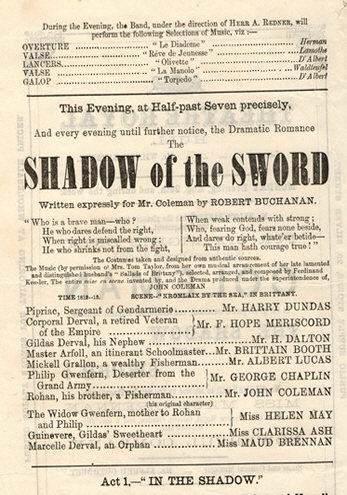

[Pages from the programme of the Hull Theatre Royal production of The Shadow of the Sword.]

Reynolds’s Newspaper (9 April, 1882) YESTERDAY’S THEATRICALS. OLYMPIC THEATRE. When “The Shadow of the Sword” was first produced, last May, at the Theatre Royal, Brighton, it did not win a very favourable verdict. It was too diffuse, and the dialogue was found lacking in poetical idea. Last night’s performance, however, showed that the plot had been compressed within more reasonable limits, although the literary defects of the piece are still wearisomely apparent. The first act opens at a Brittany village on Christmas-day. Here Rohan Gwenfern (Mr. John Coleman) is found supporting his mother. Gwenfern is a fisherman, and in love with Marcelle Derral (Miss Margaret Young), a lowly beauty, boasting another lover in the person of Mickell Grallon (Mr. T. Balfour), who is as sumptuously blessed with this world’s stores as Rohan is ill-provided. Philip Gwenfern, Rohan’s brother, is in the army, deserts, and only comes home to be confronted with “Le Petit Caporal,” who summarily orders him to be shot, a sentence which brings the first act to a weak melodramatic conclusion. In the second act Rohan has the ill-luck to be drawn for a conscript, and in the third act wanders into a seaside cave, apparently for the purpose of enabling the stage- carpenter at the Olympic to unwind a panorama showing the downfall of Napoleon. Before the act closes, unlucky Mickell Grallon gets shot, a catastrophe which clears the way for Rohan’s union with Marcelle. In the fourth act Rohan bravely rescues his sweetheart by means of a raft, the country being flooded; but in the fifth act he is discovered guarded with soldiers, and on the eve of meeting the same fate as his brother. Just at this moment the prediction of the panorama comes true. Napoleon falls, and Rohan is liberated, to make, let us hope, a better husband for Marcelle than the author has succeeded in writing a piece. The cast was creditably filled. Mr. John Coleman, as at Brighton, made an effective Rohan, rather too stilted for an ideal lover, but full of careful acting and showing a good study of the part. Miss Margaret Young was hardly equal to the task of portraying the village beauty to whom Rohan plighted his troth. As the widowed mother, Miss Robertha Erskine played with skill and effect, and her impersonation was decidedly a good one. The rest of the characters hardly call for comment, though a word of praise is due to the horses on which Napoleon (why was not this actor’s name to be found in the bill?) and his staff rode on the stage in the first act, the Corsican being attired in the famous suit he used when he—pictorially—crossed the Alps. The “Shadow of the Sword” was well mounted, and the appointment, except a wobbling moon in the first act, left little to be desired, whatever opinion might be held about the large number of scriptural quotations which embellish the dialogue, or of the fine assortment of curses. The can-can ballet at the end of the second act is vivacious, and as the stage is crowded with people, it leads to regret that so poor an imitation of the Adelphi drama should have had such evident pains spent on staging it. At the end of the third act Mr. Coleman came forward and apologized for the prolonged “waits” between the scenes. This was owing, he alleged, to the freaks of some workmen, whom he had to discharge on Thursday, and to whose defection was due his consequent inability to produce the drama as perfectly as could be wished. Mr. Harris, however, had kindly come to his assistance with a body of men from Drury-lane Theatre, and by working the whole of Friday night everything had been done that was possible under the circumstances. His speech was noisily interrupted both by the pit and the gallery. ___

Lloyd’s Weekly Newspaper (9 April, 1882) OLYMPIC The production last night of Mr. Robert Buchanan’s Shadow of the Sword was not attended with any great enthusiasm on the part of the audience. To begin with, the curtain rose half-an-hour after the appointed time, and the development of the piece revealed a decidedly romantic, but weakly-written melodrama—the period, the First Empire, and the purpose, a protest against war. The “Shadow of the Sword” is the shadow that Napoleon’s ambition cast over France. In its gloom is gathered the family of a widow whose husband first and sons next fall victims to “glory.” The last son, Rohan, is an apostle of peace, but he, too, is torn from his home on conscription, but with lion courage against great odds and the war fever of the time he asserts in his person a protest against the man he regards as the murderer of his kindred. He deserts and becomes a fugitive, and of his perils and escapes the piece is made up. There are some sensation scenes—which last night took so long to set as to entail tedious “waits,” but this was explained by Mr. Coleman, who in a speech said that owing to a difficulty with his carpenters he had been compelled to rely upon the assistance of the employés of a neighbouring house, rendered at the last moment. In the development of the story there was much that is sensational, and applause, not always judicious, greeted the stronger situations, but the promise of the play was poor. Mr. Coleman sustained the part of Rohan with some vigour and energy, and Mr. Henry George was Master Arfrell, the schoolmaster, who inspires Rohan with his anti-war doctrines. Miss Robertha Erskine and Miss Margaret Young sustained the leading female parts. The play which is new to London, was originally brought out at Brighton on the 9th of May last year. ___

The Referee (9 April, 1882 - p.3) OLYMPIC—SATURDAY NIGHT. It cannot be a frequent experience even with the most popular dramatist to have two new plays produced on the same day at metropolitan theatres of recognised position; and as Mr. Robert Buchanan is not, to put it mildly, the most popular of living dramatists, he ought to be congratulated on his exceptional good fortune. Whether the opportunity thus afforded will do him much good is open to question, but at any rate he has had it, and thus has enjoyed an advantage for which many a better man may sigh in vain. Previously to the commencement of to-night’s performance a little farce was played in front of the curtain, comparable to that we have recorded above at the Imperial. There it was the occupants of the stalls who were worried; here the pit and gallery were sorely tired by a delay of thirty-five minutes beyond the advertised time of commencement. “The Shadow of the Sword” was produced at Brighton last May, where it does not seem to have made any marked impression. In one notice we read that the five acts might with advantage be cut down to three; but a glance at the programme this evening showed that Mr. Buchanan had not taken this advice. We were informed in the public prints that some novel and extraordinary scenic effects would be shown in this play. The first of these occurred in the opening scene, on the coast of Brittany, when a moon shone alternately white and black, and occasionally varied this eccentricity by appearing with a bar across its face. In this act we were introduced to the Emperor Napoleon, who made one gesture with his right hand and another with his left, but did not speak a word; also to Rohan Gwenfern, of whom some pretty things were stated in the programme: “His hair of perfect golden hue floats to his shoulders. His head is that of a lion; his figure, agile as it is, is Herculean.” And to Master Arfoll, an itinerant and half crazy schoolmaster, who quoted Scripture by the yard. There is a desertion from the army, an arrest, and an execution. In the second act the deserter’s mother dies, and Rohan is drawn for the conscription. Thereupon he utters an appalling curse upon Napoleon, mingling with it something of the spirit of prophecy. It may be mentioned that these events occurred on his wedding day, which is sufficient to account for his unpleasant mental condition. Now there ensued an interval of more than half an hour, and further ebullitions of discontent from the pit. At last the curtain went up, and a brief front scene was played. Then again it descended for a while, and on its next rising we were treated to some visionary effects supposed to represent “Napoleon and the grand army in their retreat from Leipsic—and the apparition of the destroying angel.” Rohan, having refused to serve, is hunted down, and makes a terrific leap into the sea, amid the shots of his pursuers. This bit of sensationalism did some little good, and confidence was further restored by an address from Mr. Coleman, who stated that the defects in the working of the play were due to the drunkenness of “the bold British workman,” and that had it not been for the kindness of Mr. Augustus Harris, who sent him a posse of assistants from Drury Lane, the performance could not have been given at all. Someone in the pit shouted, “You’re a liar,” but the audience generally accepted the explanation in good part, and waited with exemplary patience during another exhausting interval. Another scene, another descent of the curtain, and the theatre rapidly emptied itself. What occurred afterwards we are not in a position to state, for the spectacle was too painful to be witnessed any longer. The manager, Mr. John Collier, Mr. H. Dalton, Mr. H. George, Mr. R. Erskine, Miss Clarissa Ash, and Miss M. Young did the best they could under the circumstances, and one and all of the performers are entitled to sympathy. It was impossible to withstand the extreme feeling of depression resulting from this performance. Mr. Buchanan remains an unfortunate dramatic author. Mr. John Coleman associated with a disastrous venture at that ill-fated house, the Queen’s, tries another theatre only less unlucky, and makes an unpropitious commencement. Altogether a more unpleasant combination of circumstances could scarcely be imagined. ___

The Times (10 April, 1882 - p.8) OLYMPIC. Mr. Robert Buchanan’s “Shadow of the Sword” was a powerful novel. Its scene was laid on the iron-bound coast of Brittany, among the cromlechs and mouldering memorials of the Druidic age; white-capped girls and hardy fishermen moved through its pages, industrious, tuneful, and cheery, but having always impending over their heads the dread of the conscription, the shadow of the sword of the First Napoleon. We should have said that such a novel would form an excellent basis for a melodrama. In fact, the conscription scene which Mr. Boucicault successfully added at the Adelphi a year and a half ago to The Maid of Croissey forcibly reminded us, as we wrote at the time, of Mr. Buchanan’s Breton novel. But surmises must give way to actual experience; and if the experience of Saturday night at the Olympic Theatre is any guide, it must be confessed that “The Shadow of the Sword” in its dramatic form is a failure. It was produced under disheartening circumstances. Scenic effects were Intended to form an important feature in the representation. The management had a disagreement with the workmen, and new hands from Drury Lane came at the last moment. In the result, although the performance was advertised to begin at the comparatively late hour of 7 45, it was commenced, in a thin house, half an hour later. With depressing intervals between the acts, it went on for four hours, and when, half an hour after midnight, a few enthusiasts who remained in the gallery shouted for the author, Mr. Buchanan was well advised not to make his appearance. The play deals with a popular theme. It is a protest against ambitious war. The hero, a Herculean peasant of Brittany, whose father has been poisoned, as he believes, in hospital by Bonaparte, and whose brother has been shot because he refused to join in fusillading a Vendean seigneur, declines to join the Grand Army, although drawn by the fatal lot of the conscription. Strengthened in his resolve by the exhortations of a wandering pastor to concern himself in no deeds of blood, he lies hid in crevices of the rock, and climbs as a consummate cragsman to otherwise inaccessible recesses among the dripping stalactites and stalagmites of an ocean cave. At night he steals forth, and, lurking among the ruins of Carnac, seems to the astonished wayfarer a being of the elder world re-visiting the emblems of a worship which is extinct. To relieve the grandeur and mystery of this sombre figure a woman’s love is entwined with his fate; her and many others he saves from the great flood which on All Soul’s Eve desolates the Breton coast; and then, having emerged from his hiding-place for this work of humanity, he gives himself up to the guard and is about to be shot. But while still hiding in his lonely cavern underneath St. Michael’s Mount he has seen in a vision the coming fate of the Emperor, who has blasted his happiness and that of his family. He has seen in sleep the skies reddened with the flames of the Kremlin, the Grand Army straggling homewards through the snow, and that resistless uprising of the peoples which Professor Seeley has christened the Anti-Napoleonic Revolution. The prophecy of his dreams is fulfilled. The King returns in time to save the rebel against the Emperor. The materials to which we have now referred would seem ample for a melodrama, if skilfully combined. But that is a large “if.” Supposing even the work of the playwright to have been efficiently performed, that of the stage machinist was so backward at the Olympic that justice could not be done to the larger effort of invention, which needs carpenters as well as actors and painters for its due manifestation. To criticize a production so unfinished is labour in vain; had the first night been postponed, the representation might have been very different and much more satisfactory. The work has been played in the country with, we believe, more success. The company were at a disadvantage between scenes which descended when they should have risen, and a curtain which oscillated for two or three minutes betwixt falling and not falling whenever a point was made. The grouping was well studied, and the pathetic interest of the comparatively well-prepared first act found a response in the tears of one or two, at least, in the audience. Mr. John Coleman played the hero, Rohan; Miss Margaret Young the heroine, Marcelle Derval; Mr. John Collier represented a veteran who has retired from the army with a wooden leg and a store of tedious oaths and anecdotes; Mr. Brittain Booth impersonated an honest sergeant of gendarmerie. Miss Clarissa Ash played a peasant lass with a song; and one or two local chants were skilfully introduced from Mrs. Tom Taylor’s musical arrangement of the ballads of Brittany. ___

The Morning Post (10 April, 1882 - p.2) OLYMPIC THEATRE. Collapse such as attended the first production at the Olympic of Mr. Robert Buchanan’s new drama, “The Shadow of the Sword,” renders superfluous any attempt at criticism. Since the memorable days when “Oonah” at Her Majesty’s Theatre dragged to a conclusion in presence of an audience of about a dozen people its portentous length a failure such as on Saturday was witnessed at the Olympic has not been seen. It seemed as if a strike among the workpeople had communicated itself to the properties, and as if, in the words of Milton, “Dumb things had been moved to sympathise,” and there was a general rivalry of persons and things as to who should do the least, and do that least most badly. When, at nearly eleven o’clock, three out of the six acts of the play were over Mr. Coleman, the manager of the theatre and the representative of the most important character in the piece, came forward and apologised for shortcomings on the plea that the influences of holiday time had proved too much for his staff of carpenters and scene-shifters, whom he had been obliged to discharge for drunkenness and replace with others. This explanation was received with favour by one of the most indulgent audiences ever assembled in a theatre. During the hour and a half which elapsed before the fall of the curtain, except an occasional good-humouredly ironical protest, no sign of discontent was manifested. The audience slowly melted away, and a score or two persons, chilled into a state of indifference, remained to see the termination. Of the merits of “The Shadow of the Sword” it is scarcely possible to speak, very much of the dialogue consisted of what is technically known as “gag,” introduced by the actors for the purpose of affording time for further arrangements of scenery. The situations and effects were manqués, recalcitrant ghosts refused to answer when summoned from the “vasty deep,” and the very curtain of the theatre, sharing in the general rebellion, would neither go up nor come down at the time when a call was made upon it. Mr. Coleman may plead that he is at the mercy of workpeople. A manager, however, of his experience ought to know that to close a house until the requisite preparations are accomplished is better than setting before the public a representation in a state of so compromising dishabille. Mr. Coleman plays the hero, Rohan Gwenfern, a Breton peasant, whose refusal to submit to the conscription and to join that army of the Great Napoleon in which his brothers have perished supply the basis of the plot. Mr. Coleman’s chief duty seems to be to occupy a recumbent position, and to this he was obviously equal. That there is dramatic notion in the story may be conceded. It belongs, however, to the novel on which the play is founded rather than to the play itself. ___

Daily News (10 April, 1882) OLYMPIC THEATRE. On Saturday evening Mr. John Coleman produced at this theatre a play which is announced as “Robert Buchanan’s dramatic romance, The Shadow of the Sword,” Mr. Coleman himself playing the leading part of Rohan Gwenfern. The intended moral of The Shadow of the Sword appears to be one that might be acceptable to the Peace Society, but the idea is so unskilfully worked out as to convey no such moral in action. The hero is a Frenchman whose father died in Napoleon’s wars, whose brother was shot as a deserter, whose mother dies of a broken heart, and who himself, drawn as a conscript for the campaign of 1813, refuses to fight for Napoleon, and takes refuge in a cave and other lonely places, but is betrayed and captured. An inundation happening, he gives his word of honour to surrender himself if he may be allowed to rescue his sweetheart; he saves her, gives himself up, and finally escapes death owing to the fall of Napoleon and the proclamation of the King. Mr. Buchanan, therefore, bespeaks our sympathies for a Frenchman who refused to fight for his country at a moment of supreme peril, and who owed his deliverance from a deserter’s fate to the return of the Bourbons. MM. Erckmann-Chatrian, whose object is also to serve the cause of peace, and to show the wickedness and the horrors of “glory,” have in their “Histoire d’un Conscrit de 1813” somewhat differently presented their case. So much for the leading sentiment of the play. In its literary and dramatic aspects it is equally unsatisfactory. The dialogue is trivial where it is not bombastic, and the true note, whether in naturalness, in passion, or in humour is not struck. What should be impressive is mere rant, as Rohan’s curse of Napoleon, with its jumble of metaphors; and what is meant to be funny is often silly or in bad taste, as Guinevere’s leave-taking of Gildas, her conscript lover, when she gives him liniment and lint for his wounds, telling him he will have need of them; and her meeting with him on his return, wretched and mutilated, when she calls him s scarecrow out of a turnip-field, and a fragment of a man, and says he must have an inventory made of what is left. Unfortunate in his play, Mr. Coleman was also unfortunate in his scenery. The “waits” were so long that at last he came forward to apologise, throwing the blame on the “bold British working man,” with whom he had had such serious differences that on Thursday night he was “obliged to clear out the theatre,” and it was only, he said, by the kindness of Mr. Harris and a body of men from Drury Lane that, after being up all the previous night, he was able to present the piece at all. Under these trying circumstances the scenery could not of course be fully judged, for what may possibly on a happier occasion be telling effects were viewed with good-natured forbearance by the audience. The company struggled along to the close, which was not reached till half-past twelve, by which time only about a score persons were left in the house. Mr. Coleman, as Rohan, had a good deal to do, and he did it in such a way as to raise doubts whether it was taking place on the north side or the south side of the Thames. Miss Robertha Erskine played with some pathos the short part of the widow Gwenfern. Miss Margaret Young was painstaking as Marcelle Derval, Rohan’s fiancée, and Miss Clarissa Ash was a sprightly Guinevere, the sweetheart of Gildas, Mr. H. Dalton. Other characters were Pipriac, a sergeant of gendarmerie, Mr. Brittain Booth; Corporal Derval, Mr. John Collier; Master Argoll, an itinerant scripture-quoting schoolmaster, Mr. Henry George; Mickell Grallon, a conventional villain, Mr. Theo. Balfour; and Philip Gwenfern, a deserter, Mr. Harry Dundas. In the first act Napoleon on horseback appears, pauses, hears appeals to save Philip’s life, waves his arms, says nothing, and rides off; the name of the personator of the “Man of Destiny” does not appear in the bill. The festival of the villagers, with the rustic dance, in the second act, was a pretty scene. ___

The Daily Telegraph (10 April, 1882 - p.2) OLYMPIC THEATRE. Mr. Robert Buchanan’s dramatic romance called “The Shadow of the Sword,” first presented at the Theatre Royal, Brighton, last May, and since that period frequently acted in the provinces, has at length reached the metropolis; Mr. John Coleman, originally identified with the principal character, apparently hoping to secure a marked success on the stage of the Olympic by bestowing some extra expenditure on the scenic accessories. Time will show whether, under more favourable conditions than those attending the performance on Saturday night, any probable chance exists of very sanguine expectations being realised; but it is already sufficiently obvious that the time required for setting forth the details of an exceedingly simple story must be considerably reduced before the London playgoing public can take an interest in an evening’s amusement which enforces upon them the necessity of a morning’s reflection. An audience, even in these days of stage realism, can hardly be delighted with such closely practical illustrations of long periods separating the distinctive portions of a drama, and here alluded to in the programme as successively involving “an interval of sixteen months”; then “an interval of some weeks;” and eventually “an elapse of many months.” Between the acts it is perhaps as well to allow the imagination a rest, and it is certainly unadvisable to tax the already wearied brain by further stimulating fancy to make excessively long pauses represent the flight of years, even when the illusion is attempted to be sustained by the prolonged tunes of the orchestra. From the unusual duration of these intervals on Saturday evening it might have been inferred that Mr. John Coleman, knowing that several other novelties were announced for the same night, wished, with the courtesy of a polite metropolitan manager, to enable his audience to en joy frequent opportunities of looking in at other theatres and seeing how their entertainments were progressing, while enabling them to come back quite time enough to take up the several links of the Olympic drama. As “all things come to those who wait,” the mode by which “Rohan and Marcelle pass out of the Shadow of the Sword” was duly explained to the few who remained until the falling of the curtain, half an hour after midnight; but it is to be feared that by this time many had quite forgotten the more important incidents occurring in the earlier acts. After Mr. John Coleman, at the end of the third scene, had taken his apparently perilous “leap for life” by jumping from crag to crag and then plunging into the sea—one of the most sensational incidents in the piece—he came before the act drop in his capacity of managerial director to explain that he was compelled to seek indulgence for delays that might occur in consequence of certain difficulties encountered with his workpeople, presumably arising from the festive celebration of a holiday period, and only surmounted at the eleventh hour by the prompt assistance he had received from the stage carpenters of an adjacent establishment. It would be manifestly unfair to Mr. Robert Buchanan to pass, under these circumstances, a decided opinion upon a drama, certainly written with the laudable intention of showing the horrors of war contrasted with the blessings of peace; and it will be sufficient to record that the representatives of the various personages introduced earnestly exerted themselves to secure a favourable result, and that a lively characteristic ballet in the second act was so well executed as to be spontaneously encored. It is not at all unlikely that this dance may prolong the existence of the drama. ___

The Scotsman (10 April, 1882 - p.5) “The Shadow of the Sword,” by Mr Buchanan, which has already been taken round the provinces, was produced at the Olympic to-night, but in a somewhat perfunctory fashion, and with but little success. ___

The Standard (12 April, 1882 - p.3) OLYMPIC THEATRE. Mr. Robert Buchanan has had the gratification of producing two of his dramas upon one day—the first being the adaptation of Lord Lytton’s “Paul Clifford,” played at the Imperial under the title of Lucy Brandon, and the second a version of one of his own novels, “The Shadow of the Sword,” now being given at the Olympic under its original title. On the occasion of the first representation of the latter, the manager, Mr. John Coleman, was beset with material difficulties in the lack of proper subordinate assistance, with a result which would have proved disastrous to many a really admirable work of dramatic art; but as matters behind the scenes are now probably working smoothly, the piece may be judged on its merits alone. Although there are some effective scenes and some episodes of considerable interest, it is to be feared that the hand of genius is not apparent in The Shadow of the Sword. From witnessing the play it is easy to conceive that the theme would form an interesting ground-work for a novel; but, unfortunately, the art of writing novels and that of constructing dramas are two widely different things, not always to be met with in the same individual. ___

Brighton Gazette (13 April, 1882 - p.7) HUMBLER mortals need not envy Mr Robert Buchanan in his present frame of mind. Both his new plays on Saturday were damned, that at the Olympic, I fear, irrevocably so. Managers do not now accept a first night’s verdict as a rule, and the recent case of Mr Burnand’s adaptation, the Manager at the Court Theatre, is an instance in their favour, but when the audience are only kept from openly chaffing the author and actor by an appeal on the part of the manager ad miserecordam I take it, the fate of the play is sealed, such was the case with Mr Robert Buchanan’s Shadow of the Sword. The sword which casts its shadow, is, it need hardly be said Napoleon’s, and one of the funniest things of the piece, is a tableau representing a speechless Napoleon and his staff mounted on real chargers. ___

The Era (15 April, 1882) THE OLYMPIC. Pipriac . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Mr BRITTAIN BOOTH Mr Robert Buchanan, more fortunate than most dramatic authors, was represented at two theatres on Saturday last, but the circumstances under which The Shadow of the Sword was presented at the Olympic were not calculated to impress the playgoer favourably. No doubt want of preparation was the principal cause of the lamentable results witnessed at the Olympic on Saturday night, and if it be true that there was only one rehearsal we can understand, in some measure, why the scenic and mechanical effects so often disappointed the audience and caused exclamations of impatience. A weary half-hour passed away after the time announced for the commencement of the piece, and, upon an average, half-an-hour elapsed between each act, so that the audience became smaller and smaller until half-past twelve, when at last the long-suffering playgoers departed from the theatre with, we fear, a very confused notion as to The Shadow of the Sword and the personages who appeared in it; for, with the best intentions, the performers could do but little under such circumstances t make the rambling and long-winded story intelligible. After the sensation scene in the third act Mr Coleman came forward and stated that the cause of the defects was due to the conduct of the workpeople, and had it not been for the kindness of Mr Augustus Harris, who sent him assistance from Drury-lane Theatre, the performance could not have taken place at all. Comments more emphatic than polite followed, but generally the audience accepted the explanation with good humour and appeared disposed to grant every indulgence. We have since visited the theatre, and it is only fair to state that the difficulties respecting the scenic effects are now overcome, and some striking, if not very novel, scenes are represented with smoothness, and in all probability they would if thus given on the first night have secured the entire approval of the audience. The Shadow of the Sword was originally produced at Brighton on the 9th of May last. The locale is fixed at Kromlax, a village on the coast of Brittany, which, at the rise of the curtain, is presented in a garb of snow, the time being Christmas Day. The widow Gwenfern, whose husband has been killed, and whose younger son Philip is still serving in the army, depends for support on her remaining son, Rohan, a fisherman, who, for family reasons, is inveterate in his hatred of the “Little Corporal” and his continual warfare; Corporal Derval, a retired veteran, his uncle, being loud in his praise of Napoleon and his policy; Master Arfoll, schoolmaster, and Father Rolland, the village curé, preaching the doctrines of the Peace Society. An additional inducement to Rohan’s following a peaceful calling is his love for Marcelle Derval, and their love-making fills the greater portion of act one. A rival is found in Mickell Grallon, a wealthy fisherman, who perseveres in his pursuit throughout the piece. The closing incidents of act one are the return of Philip, wounded whilst deserting, his re-arrest, and the resistance offered by his brother Rohan to his capture. The Emperor and escort appear upon the scene, pardon for Philip is prayed, but refused, and the curtain falls to he sound of the shot that announces the deserter’s death. The scene in which Napoleon appears is fairly effective and three real horses are introduced. But the drawback is that the mimic Napoleon has not a word to say for himself. The most frantic appeals of the wretched maiden only win from him a movement of the left hand while with the right he signals for the advance of the troops. The second act opens with a little mild comic business between Guinevere, who is afterwards made love to by Gildas Derval, a yokel who is perpetually drunk, and altogether unsuited to so fair a maid. A rustic dance of Breton peasants in this scene was encored. The Spring Festival, which was also to have brought the nuptial day of Rohan and Marcelle, then commences; but is brought to an abrupt conclusion by the announcement that a new conscription takes place that day. Marcelle, confiding in her good fortune, draws for her lover; but her luck is evidently out, as she draws him No. 1, and he is installed King of the Conscripts. He tramples on the tricoloured badge, and denounces the Emperor in a curse of great length and malignity, his mother meanwhile appearing upon the scene and expiring from the shock of losing her only son. Now, respecting this curse we have something to say. The use of Scriptural sentences upon the stage must under any circumstances be objectionable, but when they are employed to call down the most appalling vengeance upon a human being that can well be imagined we must emphatically protest. The hero, first demanding that the Supreme Being shall awaken to punish the French Emperor, continues his speech still in Bible language until it becomes shockingly repulsive; as, for example, when, after imploring for every curse that can fall upon a man in this life, he craves that the tortures of the damned, “where the worm dieth not and the eternal fires are never extinguished,” shall visit Napoleon hereafter. Admitting all the horrors of war and the crimes of the famous conqueror, we still think that this language is not fitted for the stage. The schoolmaster also, who wanders about for no earthly purpose but to tell bad news and make fearfully long and prosy speeches, is constantly introducing Scriptural passages having not the slightest bearing upon the plot. For instance, when at Christmas time he comes to the village and says “Peace on earth and goodwill towards men,” and the rustics applaud him, his comment is “Ah, my friends, those words were sung by the angels of Heaven eighteen hundred years ago, when our Saviour was born.” If such passages aided the progress of the drama they might be tolerated, but as they do not they simply show the bad taste of the author. To continue the plot, we find in the third act Rohan in a seaside cave, where he has a dream (illustrated by a panorama cleverly painted by M. Gompertz) in which the downfall of Napoleon is foreshadowed. This panoramic effect is reduced to one scene, in which we see Napoleon on the battle field. Then the towers of Moscow, with the Destroying Angel wielding a bloody sword as the Conqueror sinks to his doom. The hero is pursued by soldiers under the guidance of Mickell Grallon, who is accidentally shot in place of Rohan. There is little that is dramatic in the fourth act, as it gives only an opportunity for Rohan to air his woes until the announcement that the floods are rising, placing Marcelle in danger. Then, in spite of being almost dead, he makes a raft and proceeds to her rescue. Act five shows us the Church of Notres Dames des Seccours, with soldiers sleeping. Rohan is about to be executed when the downfall of the Emperor is announced, and all ends happily. Taking the chief situations in this piece, and compressing them into three acts, a drama might have been written possessing certain attractions for lovers of sensational effects. But the stir, the animation, the rapid movement such a piece demands, we nowhere find in The Shadow of the Sword. Even now that there are no hitches in the scenery the play drags, and could hardly do otherwise, overloaded as it is with extracts from Holy Writ. The acting was not wholly wanting in merit. The author has given very curious descriptions of his characters. Of the heroine he says:—“She might be the daughter of some gipsy tribe, but such features as hers are common among the Celtic women of the Breton coast; and her large eyes are not gipsy black, but ethereal grey, that mystic colour which can be soft as heaven with joy and love, but dark as death with jealousy and wrath. The girl is tall and shapely, somewhat slight of figure, small handed, small footed; so that, were her cheek a little less rosy, her hands a little whiter, and her step a little less elastic, she might be a lady born.” The young lady, Miss Margaret Young, who represented the heroine, did her best to realise this picture. In a better drama she would have succeeded better, but she was certainly entitled to praise. Miss Young acted with feeling and frequently with skill. Miss Clarissa Ash was sprightly as Guinevere, and Miss Roberta Erskine gave the requisite force to the dismal scenes of the bereaved mother. Mr John Coleman had our sympathies under trying circumstances, for besides the worries behind the scenes he had a somewhat trying part. That he did not in all respects reach the author’s ideal was not his own fault, as the reader will easily imagine who peruses the author’s descriptions of his hero:—“His hair of perfect golden hue, floats to his shoulders. His head is that of a lion; the throat, the chin, leonine; and the eyes, even when they sparkle as now, have the strange, far away visionary look of the king of animals. His figure, agile as it is, is Herculean, for is he not a Gwenfern? and when since the memory of man, did a Gwenfern ever stand less than six feet in his sabots? Stripped of his raiment and turned to stone, he might stand for Hercules, so large of mould is he, so mighty of limb.” In Dickens’s “Christmas Carol,” the Miser Scrooge entreats the ghost of his old partner Marley, “Don’t be flowery Jacob,” and most earnestly do we suggest to Mr Buchanan “not to be flowery” in his descriptions of heroes and heroines. Where is the actor who could become such a stage hero as this? We must give Mr Coleman the credit he deserves for hard work and intelligence under adverse circumstances, and we hope we shall have a better account yet to give of The Shadow of the Sword. Mr Brittain Booth played with spirit as the Sergeant; and as the wooden-legged old Corporal, who is everlastingly extolling the virtues of Napoleon, Mr John Collier may be cordially praised. Mr H. Dalton has a very stupid part, but he exerted himself greatly to make it effective. Mr Balfour acted earnestly and with creditable results as Mickell; and Mr Dundas spoke the few lines given to Philip with feeling. Mr Henry George has a capital voice, and delivers his lines with clearness and decision, but he is hampered with the effort of representing a personage one always wishes away. Here is the author’s account of this prosy person:—“He was an itinerant schoolmaster, teaching from farm to farm, from field to field. An outcast, his bed the earth, his roof heaven; but the holiness of nature was upon him, and he crept from place to place like a spirit sanctifying and sanctified.” What could any actor make of such rigmarole? The greatest praise we can give the representative of the schoolmaster is that he did not bore the audience so much as might have been expected. It is hardly necessary to dwell at greater length upon the peculiarities of The Shadow of the Sword. Mr Coleman was unquestionably much to be pitied on the opening night, but under any circumstances we fear the drama would not be exhilarating. ___

The Referee (16 April, 1882 - p.2) “And things are not what they seem,” said the recently-departed Longfellow. It needed no poet to tell us that. The fact stares us in the face daily—hourly—every minute. Look at this, now. “The Shadow of the Sword” was produced at the Olympic on Easter Eve. Nothing went right. The piece itself proved of little value. There were intolerable waits between the acts, extending sometimes to half an hour, and sometimes to three-quarters; the scenery wouldn’t work properly; the manager told the audience his workpeople had got topsy-boozy, and was called a liar to his face. The whole affair was wearisome in the extreme, and when the end was reached, about half an hour after midnight, only about a score of people, and these yawning and nearly asleep, were left in the theatre. Notwithstanding all this, and much more that was anything but gratifying, out came on Monday morning the advertisements with Mr. Coleman begging to announce that “The dramatic romance, ‘The Shadow of the Sword,’ having achieved a brilliant success before a crowded house on Saturday evening, will be repeated until further notice.” Truly things are not what they seem. “The Shadow of the Sword” seemed a dismal failure. According to Coleman it was a brilliant success. Those who have been tempted to the Olympic during the week to see “The Shadow of the Sword,” and haven’t liked it, have been shouting, not “Give us back our money,” but “Give us back our orders.” If anybody asks you who is the sufferer, I believe you will be tolerably near the mark if you answer Courteney Thorpe. If anybody will leave me a small fortune, I hereby undertake not to waste any of it on such rubbish as “The Shadow of the Sword.” John Coleman made his appearance at Bow-street on Wednesday, at the request of a revolutionary scene-shifter who wanted money—money earned and money for wrongful dismissal. John explained to the worthy magistrate that he had been badly treated, that the scene-shifter, or carpenter, or whatever he was, had been disobedient, and the summons was dismissed. “Lucy Brandon,” too, which by the impartial at the Imperial was voted very small beer indeed, is now described as “a triumphant success”; and that bungling in the matter of seats, to which reference was made last week, and which caused so much confusion and annoyance, is actually pressed into the service of puffery. One of my contemporaries having complained that “every seat had been booked twice over,” the complain is turned to the purposes of advertisement. Whose impudence is this, I am wondering? ___

The Morning Post (17 April, 1882 - p.2) Mr. Robert Buchanan has written to our theatrical contemporary to say that the lovely curse at the end of the second act of his play called the “Shadow of the Sword” is not of his manufacture. Mr. Buchanan has modestly disowned the “immediate jewel” of the drama. ___

The Illustrated London News (22 April, 1882 - p.7) THE PLAYHOUSES. Mr. Robert Buchanan has publicly announced that he is not wholly responsible for the dramatic version of his novel “The Shadow of the Sword” that has been advertised and announced as his work by the management of the Olympic Theatre. He showed a drama on the subject to Mr. John Coleman, a well-known actor and one of the best stage managers living, who was permitted by the author largely to remodel and rewrite the play. This permission having been given, Mr. Buchanan does not appear to have approved of Mr. Coleman’s work. He objects to a curse in the second act; and he has an apparent horror of the conventional “stage peasant.” What Mr. Buchanan’s play would have been without Mr. Coleman’s alterations it is not for me to say, as I have had no opportunity of comparing the two works; but I submit that the novelist exhibited great good sense in seeking the advice and profiting by the experience of so old a stage manager as Mr. Coleman. Authors are not always the best judges of stage effect, nor do they conscientiously study the spirit of the dramatic times. If they were occasionally less sensitive to correction they would be more successful. Many of the most valuable theatrical properties of modern days have been made so by the experienced advice of the stage manager, who has not hesitated to eliminate beautiful though pointless dialogue, and to remodel ineffective scenes. It has been said that literary actors make the best dramatists; it is certain that they avoid the pitfalls into which the purely literary dramatist occasionally falls. All who are familiar with Mr. Buchanan’s admirable work, who know his bold, nervous songs, and have followed the course of his poetical prose, will quite understand his desire to make out of “The Shadow of the Sword” a purely idyllic drama, after the fashion of “L’Ami Fritz.” But the experiment would have been a very dangerous one. The charming play by MM. Erckmann-Chatrian would never have succeeded in this country, where on the stage, in the present condition of public taste, the purely idyllic is voted wearisome. Gems like “Olivia” and “The Squire” succeeded because they had strong stories superadded to their inherent poetry. When Mr. Hardy dramatised his own most poetical novel, he made it very like a melodrama. The playgoing public differs from the reading public, and so, I hold, Mr. Coleman was perfectly right in introducing the curse of the conscript, which is one of the most striking dramatic moments of the play, and equally right in introducing the stage peasant, who, at any rate, relieves the composition from a monotony of gloom. The cause of the ill-success of this play is, however, quite outside Mr. Buchanan’s work or Mr. Coleman’s alterations. The London public is accustomed to a more harmonious style of art. They patronise and applaud what is very good, but they refuse to scatter a shower of gold over mediocrity. I trust that I have explained all this without temper or offence. Mr. Robert Buchanan appears to be very angry with “London dramatic critics,” and to consider them, one and all, incapable of civility or fair play. He invited them to see his plays of “Lucy Brandon” and the “Shadow of the Sword,” and because they could not conscientiously recommend those works they have incurred the author’s displeasure, as they incur the displeasure of everyone with whose work they disagree. This is inevitable, and is the outcome of a disagreeable duty. Of the two plays, I myself prefer “The Shadow of the Sword,” but I wish that both could have been so successful as to encourage Mr. Buchanan to continue writing for the stage. His is just the temperament for dramatic writing, and just the pen that the stage requires. ___

The Morning Post (1 May, 1882 - p.2) Talking of “The Shadow of the Sword,” Mr. R. Buchanan observes, in a letter to a contemporary— “The play as represented at the Olympic was no more my production than Poole’s burlesque of ‘Hamlet’ was the production of Shakspere.” Parvos si licet, &c. Never surely was modesty carried to such charming perfection as in this comparison. ___

The New York Times (7 May, 1882) . . . Indeed, the United States has become quite a factor in theatrical business. Mr. Coleman’s chief desire was to make such an impression upon the London public with “The Shadow of the Sword” as would justify him in making a tour with it on the other side of the Atlantic. Mr. Buchanan’s dramatic reputation was never of much account, but it has been shaken to rags by his latest failures. He is certainly entitled to commiseration, for, without doubt, there is good material for the playwright in his remarkable novel of “The Shadow of the Sword.” ___

The New York Times (10 June, 1882) . . . The famous Shakespearean season which Ristori is to open will also see Mr. John Coleman as Macbeth. Mr. Coleman has had a long, bitter, personal correspondence with Mr. Buchanan over the failure of “The Shadow of the Sword.” Author and actor have mutually blamed each other in the strongest of “elegant Billingsgate.” Whether “The Shadow of the Sword” was a good play or not, it seems pretty clear that Mr. Coleman had more to do with the authorship of it than Mr. Buchanan. ___

[Since the first performance of The Shadow of the Sword in London coincided with the opening of another Buchanan play, Lucy Brandon, some papers linked the two in their reviews. The reviews of The Shadow of the Sword from The Pall Mall Gazette, The Graphic, The Athenæum and The New York Times are available on the Lucy Brandon page.] _____

Next: Lucy Brandon (1882)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|