ROBERT WILLIAMS BUCHANAN (1841 - 1901)

|

ROBERT WILLIAMS BUCHANAN (1841 - 1901) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

‘The World’s Desire’ by Rudolf Blind

The court reports of Buchanan’s bankruptcy mentioned his ‘purchase’ of a painting, ‘The World’s Desire’ by Rudolf Blind, and since he never took possession, I wondered what had become of it. I thought it would be easy enough to find a reproduction somewhere online and a brief biography of the artist, but no such luck. Rudolf Blind is not listed in any of the usual reference works and the only mention on the Tate Britain site is the following, from the timeline related to a 2001 exhibition, ‘Exposed: The Victorian Nude’: “Rudolf Blind, the Belgian-born painter is put on trial for exhibiting a picture alleged to be ‘obscene’ and ‘wicked’; the judge, taking into consideration ‘artistic expression’, throws the case out of court.” The British Library has two items relating to ‘The World’s Desire’: A handbill, (“391, Strand. Now on view daily ... The world's desire, by Rudolf Blind, is an unusually large ... picture, representing the adoration of the ideal female nude ..”) and a ticket to view the painting (“A Superb Work of Imaginative art.” An ideal and perfect nude. The World’s Desire. By Rudolf Blind. On view daily. Admission 10 to 6, 1/- 6 to 10 6d. 391, Strand. Beauty, comfort, elegance, and rest”). The British Library gives Rudolf Blind’s dates as 1846-1889, which are wrong, but which are then repeated elsewhere (such is the nature of the internet). ___

The New York Times headed its ‘Arts Notes’ section on April 24th, 1892 with the following: An Anglo-German painter named Rudolf Blind has written a plaint to the London papers concerning his treatment anent “The World’s Desire,” a painting in which the nude female form is seen. He says that Lord Campbell’s Act allows and almost invites the violation of an artist’s liberty to paint and exhibit the nude. The National Vigilance Association roams the streets and private informers spy on the studio. The laws now give, “as I find to my cost, any individual the power to constitute himself a Vehmgericht for offenses created solely by his own impure imagination, and this, together with the fact that obscurantists whom it is needless to specify walk to and fro in the bailiwicks seeking what worlds of art they may devour.” Mr. Blind had to attend at Bow Street Police Court to explain why “The World’s Desire” should not be destroyed as an obscene work. He holds that the situation makes scarce worth living the existence of a painter who is earnestly striving to portray with sincerity and purity nature’s loveliest handiwork. “Many an inspiration calculated to give the purest artistic pleasure to untold generations will be strangled at its birth by the fear of a possible prosecution unless those to whom liberty of expression in art is dear now bestir themselves with determined vigor. Even the triple shield of a mind conscious of the right may not be strong enough to withstand the fire of Bow Street artillery directed by possibly an irresponsible citizen.” ___

This report of the court case is taken from The Times of Thursday, April 28, 1892 (p.14): POLICE. At BOW-STREET, yesterday, Mr. RUDOLPH BLIND, the artist, appeared to a summons taken out by Mr. Edward Cox for exhibiting a picture alleged to be of an obscene and indecent nature. Mr. Keith Frith appeared in support of the summons; and Mr. Rose-Innes, instructed by Mr. Hugh Rose-Innes, represented the defendant. The picture, which was produced in court, represented Eros, the God of Love, unveiling Beauty, the World’s Desire, to her devotees. Cherubs hovering about the goddess symbolize mirth, merriment, and gaiety. Figures in the foreground represent various types and stages of mankind—the aged man of wealth, who proffers jewels; the soldier willing to fight and die for beauty’s smile; the poet ready to employ all his genius in her adoration; and the youth bringing a wreath of roses to lay at her feet, but undecided whether to remain with her, or to yield to the advice of the old man and devote his life to the Church. In opening the case, Mr. Keith Frith said the question to be decided was not whether the picture was beautiful, as there could be no question whatever about that; but the question was, Had the defendant painted a picture which was obscene within the meaning of the Act under which the summons had been taken out? This was Lord Campbell’s Act, 20 and 21 Vict., and section 1 of this Act made it a misdemeanour to exhibit a picture which was obscene. He did not attack Mr. Blind on the merits of his picture, which was undoubtedly a work of art; but the question was whether it was not an indecent picture which was being exhibited for the purposes of gain. Mr. Edward Cox, the complainant, said he was a solicitor’s clerk, and had been upwards of 40 years in one employment. At present he was out of a situation. On March 21 he was passing along the Strand when a bill was put into his hand. On reading it he found it related to a picture called “The World’s Desire,” which it described as “naked and not ashamed.” Witness was induced to go and view the picture which was the subject of this prosecution. On April 14 he had an interview with the defendant, Mr. Blind, who said that he was the exhibitor of the picture, and also the occupier of the premises in which it was exhibited. In consequence of what he had seen he thought it right to take these proceedings. Cross-examined by Mr. Rose-Innes, witness admitted that he knew little or nothing of art. He had never been abroad, and had never visited the Royal Academy. On going into the place where the picture was on view witness could not say that there were any boys or girls present. He thought not. Mr. John De Morgan deposed that he was an engineer, and had also been a journalist. He had seen the picture, and was induced to do this by having a bill put into his hand when passing along the Strand. By Mr. Vaughan.—I think it a highly suggestive picture to the young mind. By Mr. Rose-Innes.—I don’t think it would do any harm to an adult mind. Mr. Rose-Innes, for the defence, contended that the statute under which the summons was taken out was not directed against the exhibition of single pictures which were works of art, but against the trading in pictures of an indecent nature. The complainant had failed to prove that his morals were in any way shocked by what he had seen. If he could have proved that, his proper course would have been to have applied for a warrant for the arrest of Mr. Blind. An offence at Common Law might have been committed, but the complainant had taken a course which he had no power to do under the Act. The learned counsel did not, however, wish to have the summons dismissed on a point of law. He would call men of the highest eminence in their profession, who would prove that the picture could in no sense be called obscene. Mr. F. Goodall, R.A., said he was acquainted with works of art in this and in other countries. He was present, however, to say whether in his opinion the picture was an obscene one, and not to speak as to its merits as a work of art. Mr. Rose-Innes—Do you consider the picture obscene? Witness.—I certainly do not. Mr. Vaughan.—This is intended to be a representation of the human figure; would you consider the exhibition of the female figure as obscene? Witness.—This is a picture. You never find in nature a perfect form; you have to go to many to find one. Mr. Vaughan.—I am suggesting to you that this is a representation of the human form. Witness.— The finest works of the old masters are true ideals of the human figure. The exhibition of the human figure itself would, I should say, be obscene. In cross-examination, the witness said that at the Royal Academy this year there were several pictures in the nude. Mr. H. Stacy Marks, R.A., said that he certainly could not describe the picture as obscene. To his mind there was nothing of a suggestive or improper character in it. Mr. Fallew said that in his opinion the picture was painted in accordance with the conditions of the representation of the nude. He did not find sufficient realism in it to make it obscene. He would not for a single moment consider it so. Mr. Christie Murray said he saw a wilderness of dirt in the minds of the people who could say that the picture was obscene or indecent. Mr. John MacWhirter, A.R.A., after examining the picture closely, said that, in his judgment, there was nothing obscene or indecent about it. Miss Wilson, art critic, Mr. John M. Browne, Mr. M. S. Sullivan, Mr. William J. Larkins, and Mr. Williamson all gave similar evidence. Mr. Vaughan said that when he first saw the picture his impression was that it was one which ought not to be exhibited. This was only an individual opinion, and one likely to be overborne by the evidence which had been called before him. This undoubtedly went to show that in the estimation and judgment of men of great eminence in the arts the picture was one which could not be called obscene. He was quite satisfied that no jury, with the evidence before them which had been given for the defence, would ever convict the defendant of having exhibited a picture which was obscene or indecent. There was only one way to deal with the summons, and that was to dismiss it. This decision was received with great applause. ___

Rudolf Blind and ‘The World’s Desire’ made an appearance in Dagonet’s ‘Mustard and Cress’ column in The Referee of 1st May, 1892 (p.7). ‘Dagonet’ was G. R. Sims, and the ‘dearly beloved Bard’, mentioned in the piece, is Robert Buchanan. My Dear Blind,—I have, as you know, the very greatest admiration for your artistic ability. Among my most prized possessions are the works of your pencil and your brush. Not long ago, when the stars were waning overhead, and the lonely roads of Hampstead were gradually whitening in the dawn, you and I left the hospitable roof of our dearly beloved Bard and began an argument concerning “The World’s Desire.” You had just been summoned for exhibiting an indecent picture, and you were naturally indignant. I listened to you for quite half an hour while you held me by the buttonhole at the corner of Fellowes-road, and mistook me for the presiding magistrate, and then I gave you my views on the subject. ___

On Monday, May 16th, 1892 (p.6) the following letter was printed in The Times: THE NUDE IN ART. TO THE EDITOR OF THE TIMES. Sir,—The recent abortive prosecution by a private individual under the provisions of Lord Campbell’s Act of a certain picture at Bow-street is perhaps an opportunity for reviving a discussion on the incidence of that Act, dormant since the death of Mr. H. G. Bohn, who was the chairman of a committee formed with the object of obtaining the revision of 20 and 21 Vic., cap.83, by united action on the part of all those to whom liberty of artistic expression is justly valuable. ___

In September 1893 Rudolf Blind was in court again, this time for bankruptcy: The Times (13 September, 1893 - p.2) A receiving order was recently made against Rudolf Blind, artist, and accounts have now been issued showing unsecured liabilities £2,136 and available assets of small amount. The bankrupt states that his insolvency is attributable to his expenses having exceeded his income owing to ill-health, to interest on borrowed money, and to costs in connexion with proceedings instituted against him in April, 1892, to restrain him from permitting the exhibition of a certain picture. The unsecured liabilities include £450 for borrowed moneys. ___

Presumably this is when Buchanan stepped in to ‘accommodate a friend’ (Blind had provided an illustration for Buchanan’s The Outcast published in 1891) and offered to buy ‘The World’s Desire’ for £450. However, due to Buchanan’s parlous financial state which was just as bad as Blind’s (if not worse), the transaction was never completed. It does appear that no money changed hands and the £450 of ‘borrowed moneys’ mentioned in Blind’s bankruptcy report was transferred to Buchanan - who then failed to pay the bill. (I’m trying desperately hard not to use the phrase, ‘the blind leading the Blind’.) Whether there was any more to Buchanan’s attempted purchase of the painting than a friendly gesture is not known. Perhaps he was showing solidarity with a fellow artist, whom he felt was similarly oppressed by the ignorance of the mob. Or maybe he just liked it. In a letter to The Telegraph, published in The Coming Terror and other essays as “Beneficent ‘Murder’ (2)” he states: “If he likes statues and pictures of the nude (as I do), he contends that he has a right to enjoy them, despite the fact that they create nasty sensations in ‘moral’ people.” Anyway, by 1897 Rudolf Blind was back in business, with a safer subject, according to this advert in The Times (24 March, 1897): |

|

||||||||||||||||||

|

As for ‘The World’s Desire’, the last mention I came across, apart from Blind’s obituary, was the following court case. The Observer (26 November, 1911 - p.12) LAW REPORT.—NOV. 25. King’s Bench Division. MR. JUSTICE DARLING AND “THE WORLD’S DESIRE.” Mr. Justice Darling heard an action by Mr. William Manning, of Brightlands, Wallington, and Mr. P. H. Head, of The Chestnuts, Horley, against Mrs. Annie S. Blind, wife of Mr. Rudolph Blind, artist, of Queen Anne’s Grove, Bedford Park, for the delivery up of a picture painted by the defendant’s husband, entitled “The World’s Desire,” and a declaration that they had a lien upon it. ___

The Times (22 February, 1912 - p.3) “THE WORLD’S DESIRE.” In this case Mr. William Herbert Manning and Mr. Percy Herbert Head sued Mrs. Annie Sarah Blind for delivery up to them of the picture “The World’s Desire” and damages for its detention or damages for trespass and conversion. ___

The Times (23 February, 1912 - p.3) “THE WORLD’S DESIRE.” The hearing of this action, in which Mr. W. H. Manning and Mr. P. H. Head sued Mrs. Annie Sarah Blind for the delivery up of the picture known as “The World’s Desire” and damages for its detention was continued this morning. ___

What happened to ‘The World’s Desire’ after this, I have no idea. Perhaps it still lies rotting in the warehouse of Messrs. Shoolbred, or maybe Mr. Manning and Another managed to sell it. If anyone has any further information about its current whereabouts I hope they’ll drop me a line, I would love to know what all the fuss was about. Searching for other examples of Rudolf Blind’s work I found the following illustrations from magazines: |

||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||

|

Portrait of Miss Kernochan from The Whitehall Review, 1881. |

||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||

|

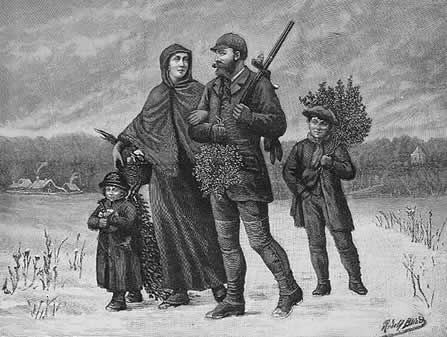

“Gathering Decorations” from The Illustrated London News, December 1888. |

||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||

|

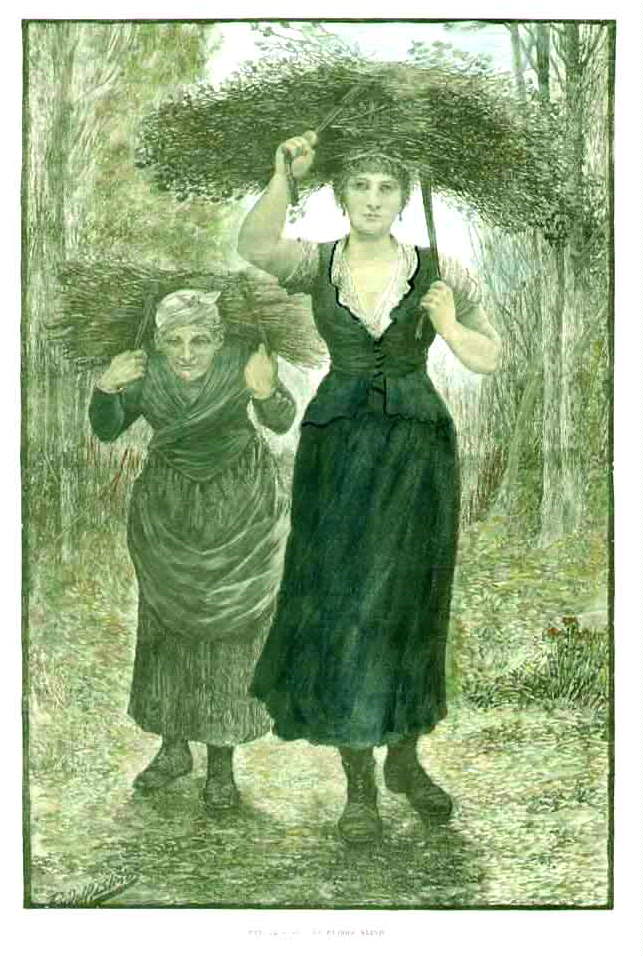

“Winter Fuel” from The Illustrated London News, 1889. |

||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||

|

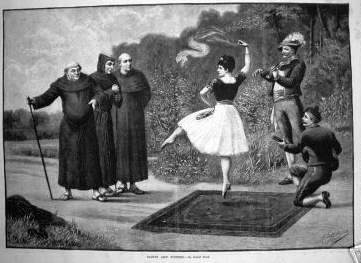

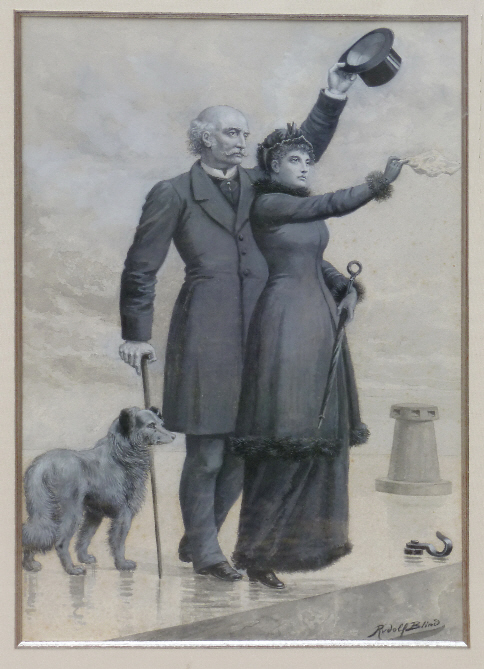

“Saints and Sinners” from The Illustrated Sporting & Dramatic News. As for Blind’s paintings, I only found two examples online. This untitled watercolour which went for £140 on ebay, |

||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||

|

and this 1894 oil painting (32” x 24”), variously entitled Amor og Psyke, Cupid and Psyche and Flora und Zephyr: |

||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||

|

In October, 2011 I received the following photo of a painting by Rudolf Blind from Ashley Miller. The watercolour was commissioned by a brother of Ashley’s great-grandfather Arthur Thistlewood Davenport and was sent to him sometime after he emigrated from England to Virginia in the early 1870’s. I’d like to thank Ashley for sending me this further example of Rudolf Blind’s work. |

||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||

|

[‘The Farewell’ by Rudolf Blind. Click the picture for a larger image.] In February, 2023, I received an email from Rudolf Blind’s great, great, great grandson suggesting a quest to find ‘The World’s Desire’. I felt that way lay madness, but I did have a quick look round the web, just in case I could find anything more than I already had (all of which is here) and I came across a two more paintings and a ithograph. . |

||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||

|

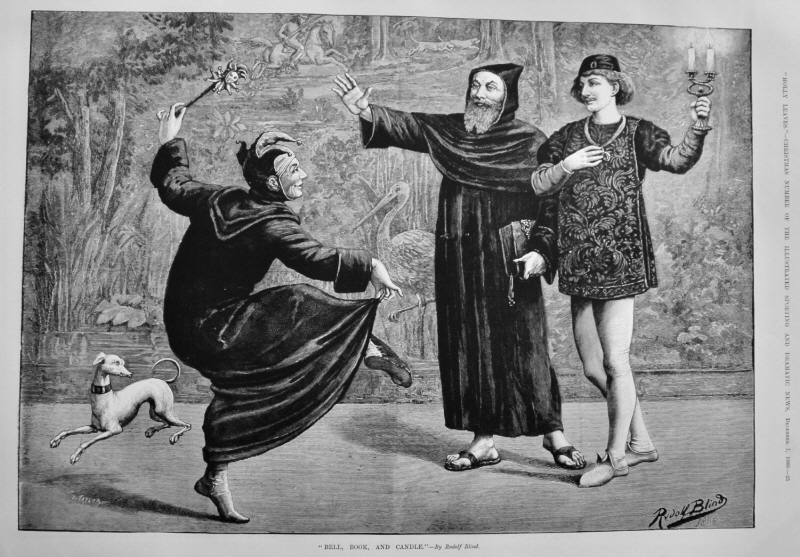

‘Bell, Book, and Candle’ (1889) |

|||

|

|

I also came across a couple of sites about Southdowns Manor, “a delightful and exclusive wedding venue in Trotton, Hampshire”. Here’s a brief history: “Southdowns Manor is an unspoiled historic house, constructed near the end of the 19th century by Hon John Hervis Carnegie, who was the High Sheriff of Sussex in 1862 and the third son of the 7th Earl of Northesk. His initials can still be seen today on a stone boundary post, left of the Southdowns Manor entrance. Quite nice digs considering Rudolf Blind was in the bankruptcy court in 1893. There’s a video of Southdowns Manor and the wedding of Alice and Rob, here. ___

In addition there are several mentions of an English translation of Leo Frobenius’ Und Afrika sprach: wissenschaftlich erweiterte Ausgabe des Berichts über den Verlauf der dritten Reise-Periode der Deutschen Inner-Afrikanischen Forschungs-Expedition in den Jahren 1910 bis 1912, (4 vols, 1912-13) as The Voice of Africa: Being an Account of the Travels of the German Inner African Exploration Expedition in the Years 1910-1912, (2 vols, 1913) by Rudolf Blind. Presumably this is the same Rudolf Blind, although this aspect of his career is not mentioned in his obituary. The Times (4 February, 1916 - p.8) MR. RUDOLF BLIND. The death occurred on Wednesday, at his house at Bedford-park, Chiswick, of Mr. Rudolf Blind, the artist. ___

At which point the story of Rudolf Blind becomes even more intriguing. As the son of Karl Blind, the German revolutionary, Rudolf was the step-brother of both Ferdinand Blind, who attempted to assassinate Bismarck, and Mathilde Blind, the noted feminist poet. The following obituary of Karl Blind is from The Times (1 June, 1907 - p.14).

OBITUARY. MR. KARL BLIND. We have to announce that Mr. Karl Blind, the veteran German revolutionary agitator and writer, died suddenly of heart failure at his house at Hampstead yesterday. He was in his 81st year, and had been long domiciled in England, after a turbulent and eventful youth. ___

Photos of Rudolf Blind’s grave in Maldon Cemetery, Essex from the Find A Grave website, taken by Iain MacFarlaine. |

|||||

|

|||||

|

|||||

|

|

|

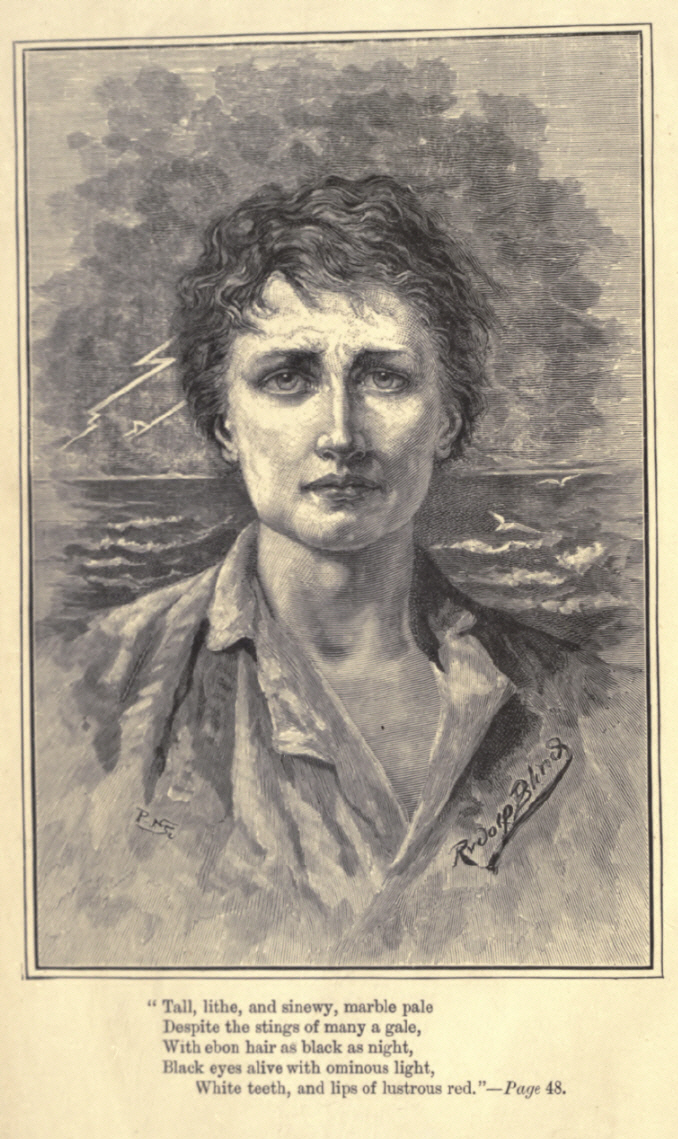

[Frontispiece for Buchanan’s The Outcast by Rudolf Blind.] _____

Back to Buchanan and the Law: Robert Buchanan’s Bankruptcy

|

|

|

|

|

|

|