ROBERT WILLIAMS BUCHANAN (1841 - 1901)

|

ROBERT WILLIAMS BUCHANAN (1841 - 1901) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

ROBERT BUCHANAN AND THE MAGAZINES LIGHT

In April 1878 Buchanan launched his own weekly journal, Light.

The Examiner (23 March, 1878) The new weekly journal which is shortly to appear, under the editorship of Mr. Robert Buchanan, is to be entitled Light. Why not adopt Mr. Matthew Arnold’s famous phrase, and give the journal the appropriate title of Sweetness and Light? |

|

||||||||

|

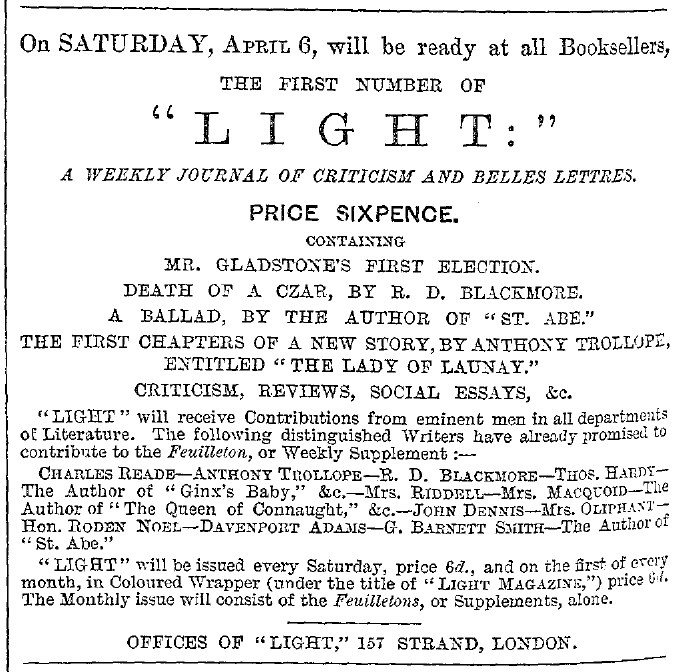

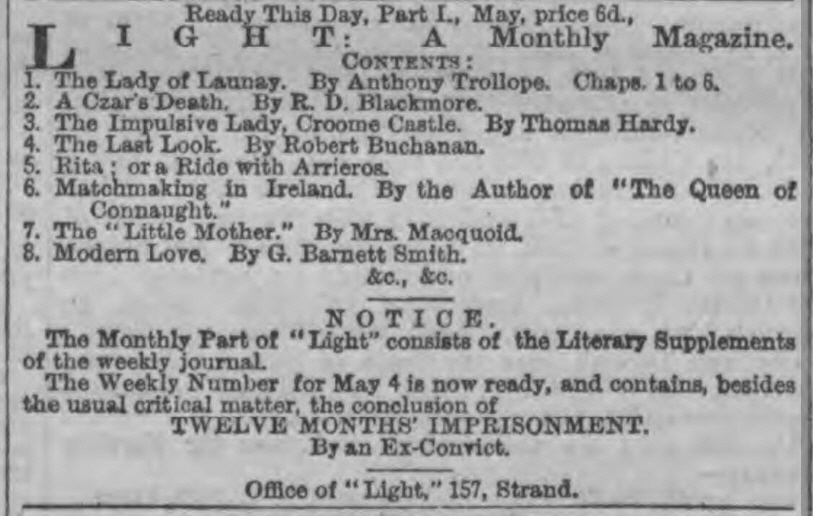

[Advert for the first issue of Light from The Examiner (30 March, 1878).] |

||||||||

|

||||||||

|

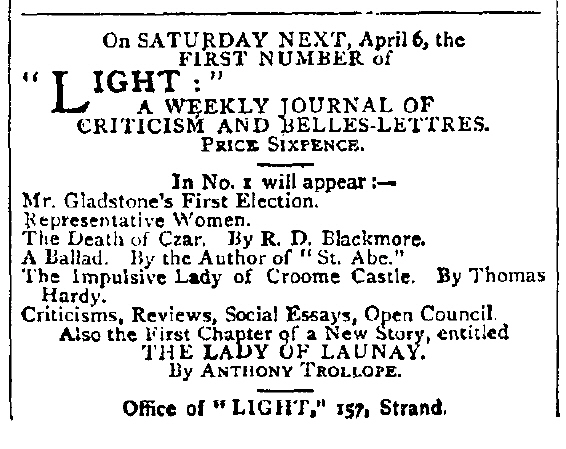

[Advert for the first issue of Light from The Graphic (30 March, 1878).]

The Sheffield Daily Telegraph (1 April, 1878 - p.3) METROPOLITAN NOTES. [FROM OUR OWN CORRESPONDENT.] LONDON, Saturday. Mr. Robert Buchanan advertises his new paper to-day. Following many recent examples it is to be called “Light.” The motto is not stated, but it certainly will not be lucus a non lucendo, although the phrase might be applied to many of the so-called society papers. Everyone will look with interest for the first number. Mr. Buchanan has not yet replied to Mr. Yates, but he is not the man to forget or to forgive, nor is he either at all a disciple of Talleyrand, in believing that language was given to man for the concealment of thought. On the contrary he is always sharp and pointed to a degree, especially in answering criticism. As he has induced Mr. Charles Reade, another inveterate hater of critics, to join him, there will certainly be some very pretty literary tilting presently. |

||||||||

|

||||||||

|

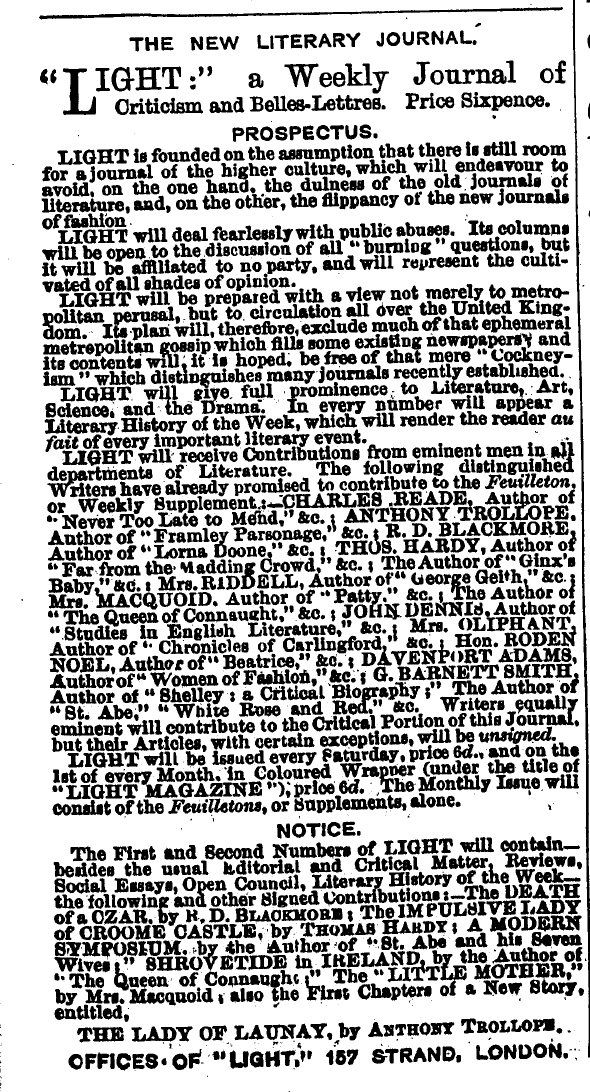

[Advert (with Prospectus) for the first issue of Light from the

The Swindon Advertiser and North Wilts Chronicle (8 April, 1878 - p.3) Light, the new “weekly journal of criticism and belles lettres,” is understood to be a venture of Robert Buchanan’s. Several of the authors announced as intending to contribute are distinctly of the Buchanan set. Notable “The Author of ‘The Queen of Connaught’,” Ginx’s Baby Jenkins, George Barnett Smith, and the author of “St. Abe,” who they do say is “Thomas Maitland” himself. The prospectus is defiant in tone, and is evidently aimed at the World and journals of kindred scope and tone. Will Mr. Buchanan oblige his many friends by taking an early opportunity of replying to Mr. Yates’s “Scrofulous Scotch Poet” attack? ___

The York Herald (8 April, 1878 - p.5) “LIGHT,” with a motto from Goethe, is the title of a new weekly claimant for public favour in the form of “a journal of criticism and belles lettres.” The idea is a good one, and it is well carried out. Criticism includes politics, but not party-politics, as may be gathered from the articles in the opening number, the most interesting one being an account of Mr. Gladstone’s First Election. The notes are brightly and piquantly written, and the literary gossip is novel and readable. There is a supplement, or feuilleton, which contains two chapters of a new story by Mr Anthony Trollope—The Lady of Launay, and part one of a story by Thomas Hardy, with a ringing ballad by Mr. R. D. Blackmore, The Czar’s Death. These weekly supplements are to be issued as a monthly magazine, with a cover. The new journal deserves, and will assuredly receive, abundant patronage. ___

The Evening Telegraph (Angus, Scotland) (10 April, 1878 - p.2) The first number of a new weekly periodical, of which Mr Robert Buchanan is supposed to be the presiding genius, appeared on Saturday. It is not always safe to judge of a paper by its first number—but that of Light, whilst containing many features of interest, is on the whole a trifle heavy. ___ Hampshire Telegraph and Sussex Chronicle (13 April, 1878) We cordially welcome the advent of a new literary and artistic journal, Light, the first number of which has just been issued. Its aim is to hold a distinct position between the comparative tameness of the old journals of literature and the flippancy of the new journals of fashion, a course which will no doubt commend itself to a wide circle. Ample space is devoted to literature, art, science, and the drama, and one of the special features is a literary history of the week. Another is a detached weekly supplement of eight pages, to be devoted exclusively to original contributions in fiction, biography, picturesque travels, descriptive essays, verse, &c. While one member of the household is perusing the more serious portions of the journal, the belles lettres may be in the hands of someone else. The first supplement contains the opening chapters of a new serial tale, “The Lady of Launay,” by the distinguished novelist, Anthony Trollope, and the first part of a tale, “The Impulsive Lady of Croome Castle,” by Mr. Thomas Hardy, who is also recognised as one of the first novelists of the day. Judging from the contents of the present number, Light will be regarded as something more than a mere society or gossip journal, and it should find a cordial welcome in all cultivated homes. |

||||||||

|

|

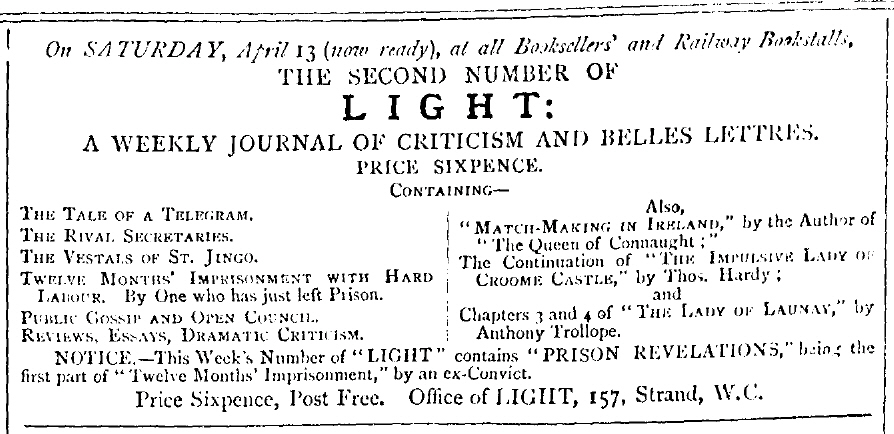

[Advert for the second issue of Light from The Pall Mall Gazette (13 April, 1878).] |

|||||||||

|

|||||||||

|

[Advert for the May issue of Light from The Standard (3 May, 1878 - p.8).]

The Sheffield Daily Telegraph (9 May, 1878 - p.2) “LIGHT, A MONTHLY MAGAZINE (157, Strand, London.)”—To my irresponsible thinking, “Light,” as a monthly magazine of literature, succeeds even better than as a weekly journal. “The Lady of Launay,” by Anthony Trollope, of which eight chapters are given in the first sixpenny number, is in the popular novelist’s best style. Thomas Hardy contributes a strange but melancholy little tale, “The Impulsive Lady of Croome Castle.” Of two papers on Ireland, one at least is made specially timely by the discussions on the murder of Lord Leitrim. “A Czar’s Death,” by R. D. Blackmore; “The Sentinel” (an incident placed in the Shipka Pass); and “The Last Look,” by Robert Buchanan, are above the average of magazine verses. George Barnett Smith and Katherine S. Macquoid are also among the contributors, and I wish the new venture—which is produced in good style—all the success which it merits. ___

The Swindon Advertiser and North Wilts Chronicle (11 May, 1878 - p.3) . . . I hear nothing fresh about Light, but so far as one can tell from the outside, Robert Buchanan’s paper is steadily making its way. On dit that his wife’s sister, the author of “The Queen of Connaught,” takes an active part in the conduct of the journal. ___

The Dundee Courier & Argus and Northern Warder (11 June, 1878) Light: a Monthly Magazine, Nos. 1 and 2.—This new candidate for public favour deserves to succeed, on account of the ability manifested in the contents of its first and second numbers. The leading story is by Anthony Trollope, and is entitled “The Lady of Launay.” It is very interesting and in Mr Trollope’s usual style. “The Impulsive Lady of Croome Castle” is a complete story well told, and “Match Making in Ireland” and “The Patrickstown Papers” are two very readable sketches. Light is well fitted to enliven a spare hour, and we have no doubt it will soon command numerous readers. ___

Birmingham Daily Post (28 June, 1878) LONDON GOSSIP. . . . Ever while you live be careful not to give an opinion (unless it be flattering) of the works of any living author, painter, or actor. It has become a dangerous experience; authors nowadays never accepting criticism, only puffs—and regarding as libel the expression of any adverse opinion on their performances. Mr. Buchanan, in Light, has dared to criticise “Our Boys,” and to express his idea that the play itself is bad, vulgar, and contrary to all rule of good taste. Only Mr. Buchanan does not add the rider which everybody else never fails to do, that the acting is so good, so truly artistic, as far as the men are concerned, that were the play itself ten times more vulgar, it could not fail of success with the public. The consequence of the omission in the déchaînement of a whole army of brave defenders of Mr. Byron’s play, which stands in no need of defence after eleven hundred nights’ performance, but Mr. Buchanan himself has furnished an anecdote, which is “going the rounds,” as it has become the fashion to express publicity. It appears that some little while ago a literary dinner was given at Richmond by the proprietors of the Fortnightly Review Mr. Buchanan being short- sighted, beckoned a figure towards him, calling out at the same time, in a rather sharp and peremptory tone, “Waiter, bring me a ‘Bradshaw.’” Now, the figure deemly seen through Mr. Buchanan’s imperfect vision belonged to no waiter at all, but was that of Mr. Richard Holt Hutton, one of the very clever editors of the Spectator. Of all the literary cutters and slashers in the critical world, those of the Spectator happen to be the most dreaded. Mr. Buchanan thereupon was seized with a panic. He remembered the motto of the old Princess Palatine of Bavaria, “Amour propre, once offended, never forgives,” and felt sure that his book just coming out would be unmercifully treated by the Spectator. But he was wrong. Mr. Hutton is too generous a man and too conscientious a critic to suffer “Old Elizabeth of Orleans” to influence his literary opinion; and as Buchanan’s book was really a first-rate production, he did not hesitate to say so. It is a pity that Mr. Buchanan should have expressed his convictions so crudely as to declare that nine critics out of ten would have remembered the mistake with bitterness, and repaid it with compound interest. He may not have reflected that Mr. Hutton may have a soul above the reach of offence, imparted by his own somewhat precipitate step, and the defective vision of Mr. Buchanan. And so ends squabble the first. Mr. Hutton, however, does not himself escape attack in another direction, for not exactly approving the collection of Mr. Allingham’s poems just published, and refusing to give them the full mead of praise to which, in the author’s opinion, they can claim. Mr. Allingham undertakes to prove, not that his poems are good poems, but that his critics are bad men. He openly accuses the editor of the Spectator of having acted from motives of revenge. Now, it is acknowledged by the whole literary world that, though the judgments of the Spectator are sometimes severe, they are never actuated by any other motive than that of honest criticism. This opinion has been the making of quite as many literary ventures as it has marred. The last number of Fraser contains Mr. Allingham’s own private sentiments on the Spectator. He, too, quotes no doubt in his inmost soul the lines made upon the paper some forty years ago, when, after quoting the attributes of the different journals of the time, the poet winds up with the doggerel lines— “And last, but not least, comes the sour Spectator, This was in the day of Mr. Rintoul, the most bitter enemy that poetasters ever had. So much for squabble the second. Now move we on to higher ground. Leaving the wriggling worms of this dull earth we ascend into the ethereal regions above this world, with Canon Farrar and the author of Eternal Hope; and here, although the fight is carried on in mid air, it is none the less fierce and passionate, like the combat of the gods and warriors in Kaulbach’s picture. Canon Farrar, as we all know, holds for certain that eternal punishment is inconsistent with that Divine mercy we have been taught to consider as the first attribute of the Almighty. His adversary contends, with no despicable logic, that the whole system of the universe being founded on the law of contrast, upon the theory of light and shadow, that eternal reward could have no existence unless contrasted with eternal punishment. This squabble is the most important of all, for it has gone far enough to serve for text of the advertisement of one of the works—that certain expressions in the adversary’s book having been considered libellous, the case has been placed in the hands of a solicitor. Next comes the deadly feud between Mr. Ruskin and Mr. Whistler. The former expresses such entire disapproval of Mr. Whistler’s painting, which, in tone, colour, sentiment, execution, so completely disgusts the fine sense and artistic judgment of Mr. Ruskin, that the latter openly declares that its very existence has become an insult to the common sense of man, and all acknowledged taste in art. This is the rough outline of Mr. Ruskin’s sentiments, and as he is not used to clothe them in purple and fine linen, but to present them in all their nudity to the public, why, Mr. Whistler thinks it of such bad example that he is resolved to try whether he would not be entitled to designate such plain language as libellous. But, how comes it that we are well nigh forgetting the most important quarrel of all? Ouida, the Amazon, fights with Burnand, the slinger, who has presumed to make most glorious sport of the fair enthusiast. But Ouida is no ordinary combatant, and she endeavours to floor her antagonist with apologue bitter and sarcastic. “A frog that dwelt in a ditch spat at a worm that bore a lamp.” “Why do you do that?” said the glowworm. “Why do you shine?” said the frog. If Mr. Burnand be not crushed by this withering irony, his vitality must be as defiant of injury as that of the humble reptile to which she compares him. The last work of Ouida—“Friendship” by name—is the first real literary fiasco which has ever befallen that lady. The heroine is decidedly more wicked than any of her former female characters, and, what is worse, she is dull and unpleasant too. There will be a fine field for the frog to hop in when he comes to frolic amongst the pages of “Friendship,” and the only difficulty this time will be for him to find the glow-worm—its light is so entirely quenched—and nothing remains but its dull grey shiny coat. The moral of all these literary and artistic squabbles is a sad one, indeed. It proves the want of true genius amongst our authors and artists. When Byron was attacked by Jeffrey he did not threaten to go to law, he sat down to pen a repulse far more satirical and incisive. When Bulwer was satirised by Thackeray he did not grow furious and abusive, he simply ignored the offence, and accepted the author’s apology from “the very top of his grandeur,” as the French say. Thackeray would vastly have preferred a lawsuit, no doubt; but times are altering every day, and our feelings are altering with them. |

|||||||||

|

|||||||||

|

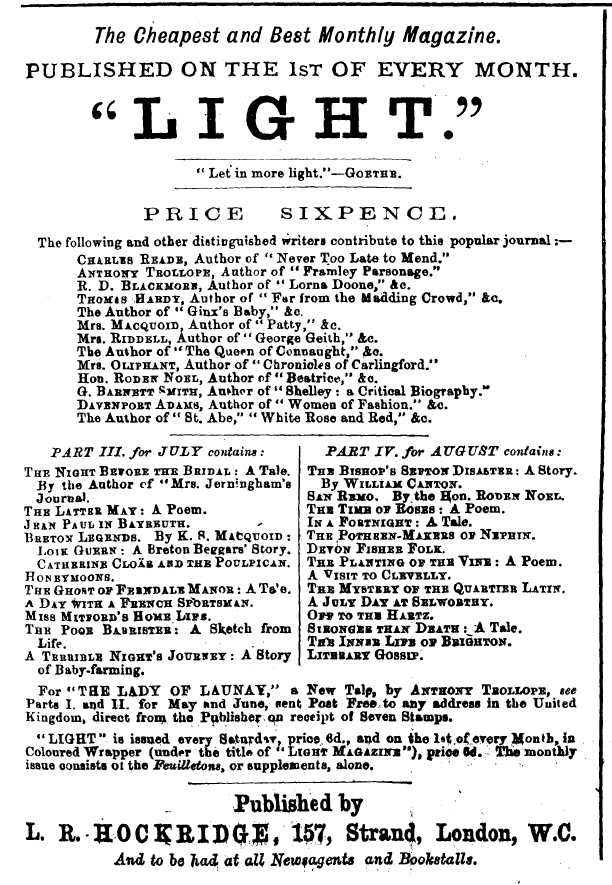

[Advert for the July and August issues of Light from Brief (30 August, 1878).] |

|||||||||

|

|||||||||

|

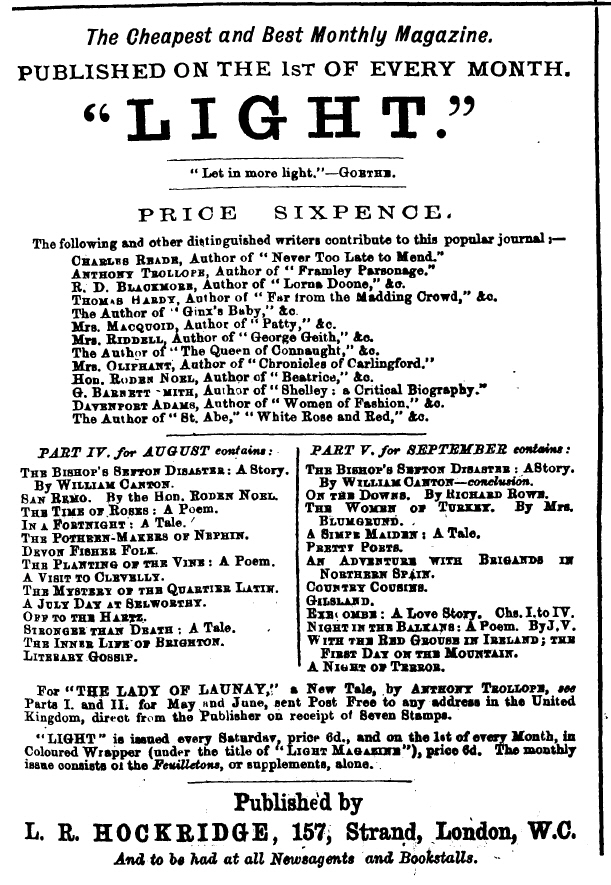

[Advert for the August and September issues of Light from Brief (13 and 27 September, 1878).]

The Exeter and Plymouth Gazette (8 November, 1878 - p.8) Light, the literary and political weekly paper which has been carried on for some time under the editorship of Robert Buchanan, the poet, came to a stop, I believe, last Saturday. It was an interesting, well-written and ably-conducted paper, but there was not room for it, and times are very bad. ___ The Ipswich Journal (12 November, 1878) Mr. Robert Buchanan’s new literary and political weekly paper, Light, went out a week ago. It is another of Mr. Buchanan’s disappointments. He has worked very hard at this publication, and it was far better in quality than many a successful weekly; but there was no opening for it, and these are not times in which to cultivate new fields in the realms of the reading public. ___

The York Herald (13 November, 1878 - p.5) FROM OUR LONDON CORRESPONDENT. LONDON, Tuesday Afternoon. . . . I hear that Mr. Buchanan has lost a lot of money on Light which appeared for the last time as a weekly newspaper on Saturday. It is not surprising that the Examiner has changed hands. Incredible as it may seem, it is a fact that Lord Rosebery was losing £80 per week since midsummer. ___ _____

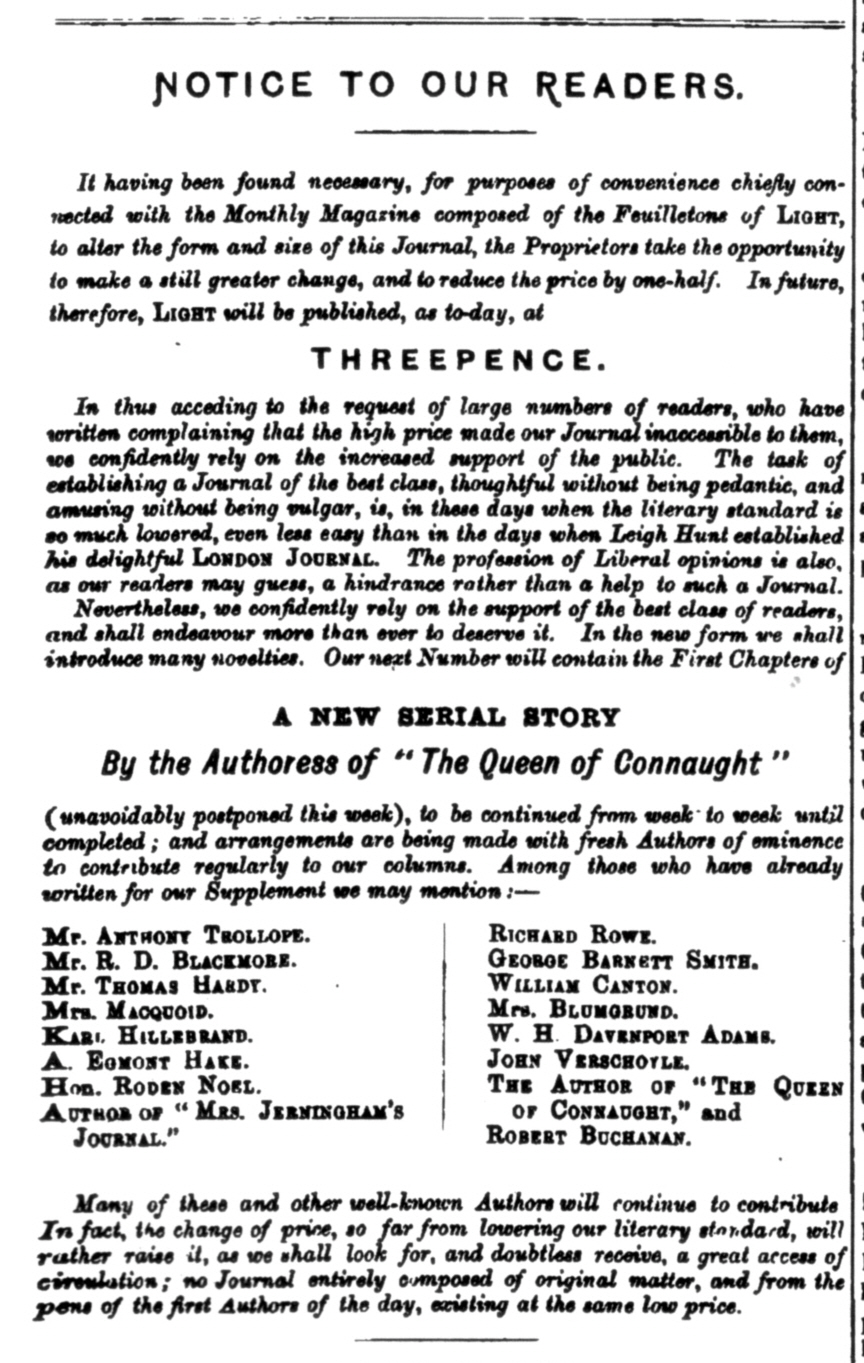

Note the question mark. I’m not sure what this is at all. From time to time I google various Buchanan titles to see if they’ve appeared online somewhere, one of which is ‘Light: A Weekly Journal of Criticism and Belles Lettres’ (no point just googling ‘Light’). In late 2013, the following appeared as a ‘print-on-demand’ item. Now, I have scant regard for the ‘print-on-demand’ branch of the publishing industry, but, google books had one of those annoying ‘snippet views’ which indicated that this was a copy of Buchanan’s Light and the price was reasonable (£7.67). I was still a bit wary, especially since there was no indication of the number of pages, but after enquiring (22 - although it turned out to be 16, the rest were blank), I thought it was, to use the vernacular, ‘worth a punt’. So, here it is: Light: A Journal of Criticism and Belles Lettres... by Anonymous. I’m still not sure what we have here. According to the title page, it is the issue of Saturday, October 5, 1878. The first page of adverts (including one for ‘The Best Cigarette In The World’) bears the same date. However from that page on it is dated October 26, 1878. Also, there is the following notice on the Contents page: |

|||||||||

|

|

Since the price on the title page is ‘Threepence’, this could indicate that the date on the title page is incorrect. According to the newspaper reports Light finally failed on Saturday, 2nd November, 1878. Whether there was a final issue, an announcement, or the next issue simply failed to appear, I don’t know. The only libraries which seem to have a complete run of Light are the British Library and Oxford’s Bodleian Library. According to the latter, there were 30 issues: Vol. 1, No. 1 to 26 (April - September, 1878), Vol. 2, No. 27 to 30 (October, 1878). This would suggest that the issue of October 26th is the final one. So, here it is. The size of the ‘print-on-demand’ version is roughly 19cm by 25 cm, but according to the Bodeian, the original size was 33cm by 39 cm, so I have scanned the pages at a higher resolution. Click the pictures for the readable version: |

|

|

|

|

[Cover] [Adverts] [Page 1] |

|

|

|

|

[Page 2] [Page 3] [Page 4] |

|

|

|

||||||||

|

[Page 5] [Page 6] [Page 7] |

||||||||||

|

|

|

||||||||

|

[Page 8] [Page 9] [Page 10] |

|

|

|

|

[Page 11] [Page 12] [Adverts] |

|

|

[Adverts] “AFGHANISTAN stands where it did. So, too, does our quarrel with the Ameer. For hastiness in picking quarrels the present Government is unrivalled; for vacillation after they have been commenced it would be as difficult to beat it.” ___

Despite the failure of Light, Buchanan did contemplate launching another journal of his own, at least according to the following news items. As far as I know none of these projects ever got beyond the ‘pre-publicity’ phase.

The Academy (14 December, 1889 - No. 919, p.386) THE FORTHCOMING MAGAZINES. WE are informed that the beginning of 1890 will witness the birth of a new monthly review, to be edited by Mr. Robert Buchanan. It will be eclectic in character, but among its objects will be the promotion of the editor’s views on social and religious questions. Unusual prominence will be given to the discussion of current literature. ___

The Derby Daily Telegraph (4 September, 1890 - p.2) OUR LONDON LETTER. LONDON, Thursday Morning. The way Mr. Robert Buchanan’s name crops up is simply marvellous. He is a very slave at his desk, and the work he turns out smacks neither of the hack nor of the midnight oil, but is imbued with a freshness and vigour that show how warmly the blood still flows in his veins. He is very incisive and very original, although Mr. Coleman, it seems, is pursuing both Mr. Buchanan and Mr. Sims with an accusation of plagiarism in connection with their successful Adelphi drama, “The English Rose.” Literary men in London are looking forward with some glee to the early appearance of Mr. Buchanan’s monthly review which, after much agitation, he is now getting ship-shape. It will be original, very original, some say, and a good thing too. Current English criticism is falling more and more into the stereotyped notices that Mr. Andrew Lang impaled the other day on the point of his spear. Probably the cruel detailed analysis of the Earl of Carnarvon’s “Chesterfield Letters” which Dr. Hill published in the Speaker in one of its early issues, is the only real live criticism which English literature has seen this year. Mr. Buchanan’s well-known ideas of what does, and what does not, constitute criticism should make of his review a brilliant success. I heard yesterday that he is revising the last proofs of his new poem “The Outcast: A Rhyme for the Time.” ___

The Nottingham Evening Post (10 September, 1890 - p.4) Truly Mr. Robert Buchanan is a remarkable person. He produces dramas at the rate of something like one a week, and in the intervals would regulate the creeds and morals of the nations by means of earth-shaking letters to the “Daily Telegraph.” With one hand he claims to redeem masterpieces of Fielding and Richardson, while with the other he is belabouring now Ibsen, now Professor Huxley or Mr. Herbert Spencer. And not content with the multiplicity of his present achievements, in order to give himself more elbow-room he is about, it is said, to issue a new monthly review, and will simultaneously publish his new poem, “The Outcast; a Rhyme for the Time.” To think that it is this random and incontinent pen which has ventured to impugn the work of workers like Goethe and Carlyle and George Eliot and Rossetti! ___

The Blackburn Standard and Weekly Express (13 September, 1890 - p.5) IT is a pity that the gentlemen who the other day discussed at Leeds the over-population of the earth did not touch upon the over-population of this country with magazines. A few days ago we heard that Mr. ROBERT BUCHANAN was about to establish a Buchanan Reflector; now somebody is about to start The Paternoster Review. What the new magazine is going to do is not especially clear; but we gather that it is to be the most Christian periodical, and will not insert improper articles—which is, perhaps, meant as “one” for Mr. GRANT ALLEN and the other earnest reformers who have lately been proposing the supersession of one wife in favour of a harem. Also it will “lay before its readers the latest developments of modern thought.” This is rather a dreadful prospect. The difficulty is to get away from the latest developments of thought. People think so much—or think they think so much—and do so little. We had imagined that the abstract was having a remarkably good innings. ___

The Yorkshire Herald (13 October 1890 - p.4) Mr. Robert Buchanan is going to start a review. He will not only edit it, but it will be his own property. In the prospectus he states that “burning topics of the day will be approached with fearlessness and honesty.” Mr. Buchanan’s most relentless critics have never insinuated that he is destitute of courage, and the first number of the Modern Review, which is promised in December, will be awaited with much interest. Mr. Buchanan’s magazine will be a shilling, while that of Mr. Newnes, M.P., which will also be published during December, will be sixpence. The multiplication of monthly periodicals is not a bad thing for authors or publishers, but in view of the fact that several existing magazines are far from being a source of profit to the proprietors, it is rather bold to add to the number. ___

St. James’s Gazette (16 October, 1890 - p.3-4) THE MODERN REVIEW. BY ROBERT BUCHANAN. MR. ROBERT BUCHANAN, who has been in his time poet, dramatist, essayist, novelist, and moralist, is soon to come out as an editor—with a magazine of his own. Mr. Buchanan has kindly sent us the following explanation, in response to our invitation to give the public some account of the scope and purpose of the new Review, in which he is to embody his ideas of what sound criticism and honest journalism really are:— In these days of hasty judgments and reckless journalism, when critics so often decline even to read what they criticise, and when a free and independent writer has little or no hope of being heard through the organs that misrepresent him, only one chance of getting a fair audience remains, which chance I am going to take by starting a Review of my own. It will be called the Modern Review, and the first number (for January, 1891) will be issued early next December, with the motto “Quis custodiet ipsos custodes.” It will (as I announce in my prospectus) “have at least one peculiarity, that of being edited by one of the best-abused men of this generation”—myself. With a fair field and no favour, I hope to give the critics a new sensation, by criticising them—in the same tender spirit with which they criticise others, but, I trust, a little more carefully. ___

The Lancashire Evening Post (18 October, 1890 - p.2) Mr. Robert Buchanan is to have a Review of his own, and he has been telling the St. James’s Gazette all about it. It is to be an ambitious Review, something beyond all Reviews that exist or have existed, and it will be the fortress whence the poet, novelist, and dramatist will launch forth his thunderbolts against such critics as have dared to criticise him in the past decade. Hence, we may expect to be amused, and the dawn of the reign of literary terror will be awaited with much expectation. Mr. Buchanan holds that he is the best-abused man of the century, and does not shrink under the stigma; nay, he is proud of it, for his time has come, and he thinks the new Macduff will “lay on” as the bareheaded friar laid on to Sir Ingoldsby Bray. It will be a battle of the pen which, one may trust, will not develop eventually into a battle in the foyer, or a little “mill” near the Athenæum, as certain quarrels have done so very recently. ___

The Freethinker (26 October, 1890 - p.510) Water cannot rise above its source, but Robert Buchanan can. His father was a Freethinker and a Socialist missionary in the old Robert Owen days, and the son now rails against the “strange anarchy” of this age, and is going to start the Modern Review to put a crooked and perverse generation straight. “We shall speak fearlessly,” says Robert, “on every subject, and on only one reverentially—that of Natural Religion, in which I hold to be the hope and salvation of the human race; and we shall endeavor to secure all voices of public opinion, except those of pot-house politicians and professional blasphemers.” For our part, we very much doubt if these persons would ever honor Robert Buchanan with copy. A pot-house politician or a professional blasphemer is something above a sneak. Robert Buchanan seems to have forgotten Thomas Maitland; other people have longer memories. ___

The Book World (1 November, 1890 - p.3) “The Modern Review” is the title of a new monthly magazine, projected by Robert Buchanan, the popular poet, dramatist, essayist, and novelist. The first number will be issued next month. The main scope and purpose of the new Review will be the criticism of critics, and to mirror, as clearly as possible, the Time in which we live. Each number will also contain a quantity of creative matter from the pens of the best writers of the day. ___

The San Francisco Call (16 November, 1890 - p.11) Robert Buchanan is to start a new publication with the amiable purpose of criticizing critics. It is to be called The Modern Review, and Mr. Buchanan says he hopes to give the critics a new sensation. In his declaration of faith in his own abilities he states that his first effort will be to be honest, his next to be interesting, and—and—“even amusing,” forsooth, and, above all, that he will try to be literary and print good literature. ___

The Lancashire Evening Post (22 December, 1890 - p.2) FROM OUR LONDON CORRESPONDENT. . . . More about the collapse of Mr. Harry Quilter’s Universal Review. “Money and labour were very freely spent to make it a success,” writes a correspondent of mine. “It contained a lot of clever work, and was the handsomest of English magazines as far as externals went, paper, type, and illustrations being all excellent; but somehow it has failed to hit the mark.” Perhaps its high price was partly the cause. The days of the half-crown review are gone. The sixpenny monthly is now the kind of thing that catches on most readily with the public. As Mr. Harry Quilter makes his exit with his review, not without a parting round of applause, there enters a new candidate for public favour in the shape of the Modern Review, edited by Robert Buchanan. Its first number is eagerly expected, for its pugnacious editor promises to devote a good part of his space to reviewing the reviewers. He will teach the world what manner of men their critics are. He will tear off their masks, and show the wires that work the puppets in their shows, and generally prove that they are mostly fools and humbugs. It is anticipated in some quarters that next month several critics will put up their shutters and retire from a discredited business. There may even be some suicides in the worst cases. Meanwhile, regardless of the panic caused by his prospectus, Mr. Robert Buchanan is calmly forging his thunderbolts in that big workroom of his at the top of his Hampstead-villa. It is also rumoured that some of the wretched men over whom this destruction impends are actually preparing to enjoy a more or less merry Christmas. Such is the callousness of the modern critic that he does not seem to mind even the Modern Review. ___

The Book World (2 February, 1891 - p.2) To some extent, Mr. Robert Buchanan’s projected new Modern Review, will be modelled on the American Reviews, for which the editor has great admiration. The Modern Review, it is said, will have no policy; it will deal with political tendencies and theories rather than party questions of the hour. The price will be one shilling. Mr. Buchanan is greatly taken with the title of the Review, which has the great merits of simplicity and strength. It has been used before, however, and what is more, Mr. Buchanan was a contributor to the original Modern Review. ___

Aberdeen Evening Express (11 October, 1894) MR ROBERT BUCHANAN AS JOURNALIST. Mr Robert Buchanan is about to issue a new weekly journal. “It will be strictly non-political,” we are told, “in the sense that it will be run on no party lines, and that it will deal with politicians, when it deals with them at all, from an independent standpoint. There will be two editions, one for London, one for the country, and the former will appear every Sunday morning. The articles, without exception, will be signed, either in full or with the initials of the writers.” ___

Glasgow Herald (23 October, 1894) WINTER season generally brings with it at least one or two new papers or magazines, but during the coming month we are to be favoured with no fewer than three new periodicals. Mr Robert Buchanan is to make the heroic attempt to give us a new weekly, to be published on Sunday morning, that is to be up-to-date, independent in politics, independent in thought, and independent in its literary and dramatic and artistic views. Another forthcoming weekly is the Realm, to be edited by Lady Colin Campbell and Mr W. Earl Hodgson. It is, I hear, to be on the lines of the Saturday, the Spectator, and the World, that is, it is to adopt the most vital lines of these periodicals, “to be as literary as the Speaker or the Academy, and as up-to-date as the World, and better than them all severally and collectively,” as one of the writers already engaged for it phrased it to me. Certainly the Realm—the name seems to me the least satisfactory thing about it—promises to start well. First and foremost there is ample capital to back it up. Then the editors are both experienced journalists and authors. Lady Colin Campbell is not only well known for her two delightful books, the novel “Darrell Blake” and the piscatorial articles collectively called “A Book of the Running Brooks,” but as an able critic of art and the drama. She is one of the ablest of the regular writers on the staff of the World and the Pall Mall Gazette. Mr W. Earl Hodgson also had much experience editorially and as an author, and his conduct of Rod and Gun and assistant editorship of the National Review give warrant of capability for his new joint responsibility. ___

The Dundee Advertiser (25 March, 1896 - p.5) Mr Robert Buchanan proposes to issue from his publishing office in Soho at an early date a new review for which a name has not yet been found. It will be edited by the bard himself, and will be written for “men, women, and critics.” The contributions will be supplied by “known and unknown writers.” Mr Buchanan has also several new works in preparation and a library edition of his poems. _____

Back to Robert Buchanan and the Magazines

|

|

|

|

|

|

|