|

Play List: 4. Corinne 7. The Mormons 9. Lucy Brandon 10. Storm-Beaten 11. Lady Clare 13. Bachelors 14. Constance 15. Lottie 16. Agnes 17. Alone in London 18. Sophia 19. Fascination 20. The Blue Bells of Scotland 21. Partners 24. Angelina! 25. The Old Home 26. A Man’s Shadow 27. Theodora 29. Clarissa 30. Miss Tomboy 32. Sweet Nancy 33. The English Rose 36. Marmion 37. The Gifted Lady 38. The Trumpet Call 39. Squire Kate 40. The White Rose 42. The Black Domino 44. The Charlatan 45. Dick Sheridan 47. Lady Gladys 48. The Strange Adventures of Miss Brown 49. The Romance of the Shopwalker 52. Two Little Maids from School ___ |

|

ROBERT WILLIAMS BUCHANAN (1841 - 1901) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

THEATRE REVIEWS 37. The Gifted Lady (1891)

The Gifted Lady Buchanan’s involvement with Henry Lee, of the Avenue Theatre, resulted in a court case in December 1891.

The Daily Telegraph (22 May, 1891 - p.3) A new “social drama,” by Mr. Robert Buchanan, is in active rehearsal at the Avenue Theatre. The title is not yet announced, but leading characters will be played by Miss Fanny Brough, Miss Cicely Richards, Mr. Fulton, Mr. Ivan Watson, Mr. Harry Paulton, and Mr. J. L. Shine. Another new play by Mr. Buchanan has been purchased by Mr. Dan Frohman for immediate production at the Lyceum Theatre, New York. ___

The Morning Post (23 May, 1891 - p.5) This, Mr. Henry Lee announces, is the last night of “The Henrietta” at the Avenue Theatre. Mr. Bronson Howard’s comedy is to be taken off to make room for a new play by Robert Buchanan, which is in active rehearsal, and is announced for Saturday night, May 30. The company performing in “The Henrietta” will give a morning performance at Brighton on Thursday next. ___

The Era (23 May, 1891 - p.8) THE weapons in Mr Robert Buchanan’s armoury are inexhaustible. It was said of Dr. Johnson that when his pistol missed fire he knocked you down with the butt end; and if Mr Buchanan should by any chance fail to demolish an adversary in a ponderous article in the Contemporary, he just scarifies him in a lively letter to the Telegraph, or writes a satirical poem about him, or pops him into his last novel as a comic character. Nay, it should seem that he has yet a further device; for, finding that the hated Ibsen has retaliated for certain Telegraphic denunciations by turning his denunciator out of his own familiar Vaudeville—Ibsen did rather score off the poet that time, really—Mr Buchanan sits down one morning and knocks you off a burlesque of the Ibsen drama, for all the world as if he were Mr Burnand himself. Next morning he appeared in another of his capacities—as the author-manager, much desired by Mr Jones—and took a theatre—the Avenue—whereat to produce his own burlesque; and rumour has it that he is even now hard at work practising a ghostly strathspey, which he will dance as the comic hero of the piece—The MacIbsen, played, of course, by our bard himself. MR ROBERT BUCHANAN’S new play, the title of which is not yet settled, is being rehearsed at the Avenue Theatre, by a company including Mr J. L. Shine, Mr Harry Paulton, Mr Ivan Watson, Mr Fulton, Miss Cicely Richards, and Miss Fanny Brough. ___

The Derby Daily Telegraph (25 May, 1891 - p.2) Mr. Robert Buchanan is once again to the front in matters theatrical. It turns out that during his recent quiet spell he has been as prolific as ever. He has his knife in Ibsen and will burlesque the Norwegian’s ideas in a comic skit, entitled “Heredity,” to be played next Saturday at the Avenue. On Saturday he and Mr. G. R. Sims read to the brothers Gatti the joint production they have written for the Adelphi, to be provisionally styled “The Roll of the Drum,” and I hear that Mr. Sothern is about to present in New York a three-act comedy, written by the same pair of dramatists. ___

The Globe (26 May, 1891 - p.4) MR. ROBERT BUCHANAN’S forthcoming social drama “Heredity” is said to be an adaptation “from the Danish of Emile Pluddermund.” Oh, these Scandinavians! If there is anything in a name Pluddermund is the playwright for our money. ___

The Daily Telegraph (29 May, 1891 - p.3) Ibsen is to be burlesqued at last. Mr. Toole produces to-morrow afternoon with what he calls “a new Hedda in one act, called ‘Ibsen’s Ghost, or Toole Up to Date.’” Mr. Robert Buchanan’s satire on the Scandinavian dramatist is, however, a far more serious affair, and will be embodied in a social drama called “Heredity,” at the Avenue, to-morrow night. The cast is rich in comic artists, containing as it does Harry Paulton, Cicely Richards, Lydia Cowell, and Fanny Brough, who is said to make the company laugh so much at rehearsal that it is conducted under difficulties. ___

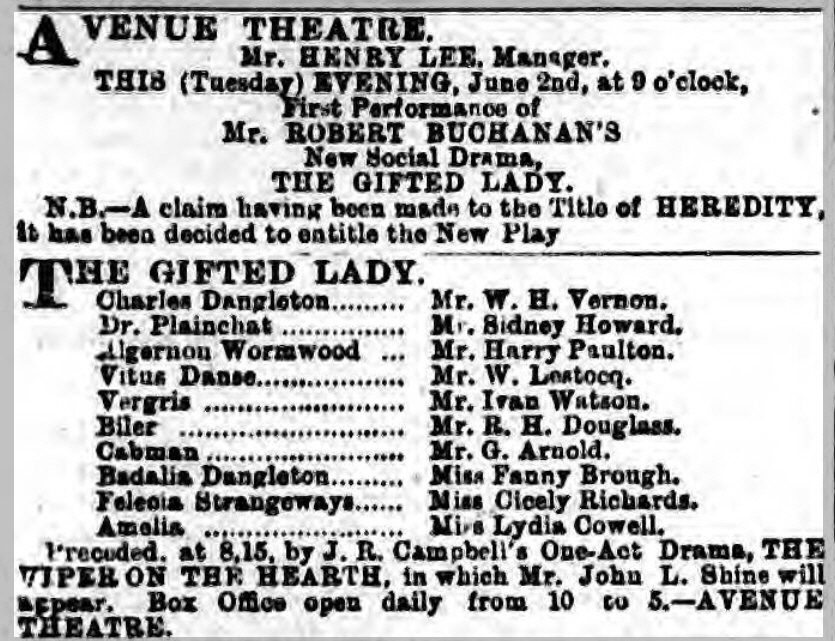

The Era (30 May, 1891) TO-NIGHT the curtain falls for the last time on the woes of Hedda Gabler, as presented by Miss Robins at the Vaudeville, and one cannot help wondering whether the Ibsen chapter of British stage history is closed. The present season has been, in actual results, disastrous for the Norwegian playwright. Four of his drama have been acted for the first time in London, for one night, two afternoons, five afternoons, and a few weeks respectively; and the rumours of future productions, once so loud, are heard no more. If discussion be the best advertisement, then has Ibsen been advertised ad nauseam. But, so far, it is in vain; the great play-going public does not take to him. That it is shocked by his work is very doubtful—for the most part it merely stays away. And yet it is more than likely that the effect of Ibsen on our stage—on writers, actors, public, and even managers—will be altogether out of proportion to the apparent result of these productions. _____ . . . MR BRONSON HOWARD’S comedy, The Henrietta, was played for the last time at the Avenue on Saturday. The theatre has been closed during the week, but will reopen this evening with Mr Robert Buchanan’s new social drama, entitled Heredity, a satire upon the Ibsen dramas. Mr Buchanan doubtless thinks it is right and proper to chaff Ibsen, but wrong and improper to chaff him. The scene is laid in London, at the present day, and the cast is as follows:—Charles Dangleton, Mr J. L. Shine; Dr. Plainjack, Mr Fulton; Algernon Wormwood, Mr Harry Paulton; Vitus Dance, Mr Lestocq; Vergris, Mr Ivan Watson; Biler, Mr Douglas; Felicia Strangeways, Miss Cicely Richards; Amelia, Miss Lydia Cowell; and Badalia Dangleton, Miss Fanny Brough. We were in error in stating that Mr Buchanan has taken the Avenue Theatre for this production. The theatre will continue under the management of Mr Henry Lee. ___

The Graphic (30 May, 1891 - p.19) The AVENUE Theatre, which has been closed since the final representation of The Henrietta on Saturday night, will reopen this evening with Mr. Robert Buchanan’s new social drama entitled Heredity. This piece, which is founded on a Danish farce, is understood to be a satire on Ibsenism. Mr. Harry Paulton will, it is said, represent “the master. |

|

|

[From The Globe (2 June, 1891 - p.4).]

The Pall Mall Gazette (2 June, 1891) “The Roll of the Drum” sounds like a very good title for an Adelphi melodrama, and had not some one else been first in the field with it in former years Messrs. George R. Sims and Robert Buchanan would have bestowed it upon the play which they have recently completed by command of the brothers Gatti. No difficulty, however, is likely to stand in the dramatists’ way when they come to select another title, for there is sure to be ample suggestive material in their piece. July will see the novelty produced. * * * * * Buchanan, the Bard, seems to be unfortunate all round in his titles. It is announced to-day that the new Avenue piece is not to be called “Heredity” after all, as that title has been claimed. The anxiously awaited “social drama” has accordingly been renamed “The Gifted Lady,” and under that style we shall behold it this evening. “Indisposition” was pleaded as the cause of the play’s postponement on Saturday, but I fancy that a change in the cast at the last moment had more to do with it. A managerial dictum this morning said:— “‘Heredity’ having been described in some newspapers as a ‘skit upon Ibsen,’ the manager desires to explain that the play is a ‘social drama’ of general interest, and not a mere burlesque of other existing dramas. It is particularly requested that the audience will be seated at nine o’clock punctually, as the tragic note is struck on the rising of the curtain.” This sounds promising, but it is not a patch upon the “Author’s Note,” in choicest Buchananese, published the other day. “Colossal Suburbanism” was distinctly good. ___

The Pall Mall Gazette (3 June, 1891) The Theatres. “THE GIFTED LADY” AT THE AVENUE. Mr. Robert Buchanan unwittingly told the truth last night when in his comic “Author’s Note” to “The Gifted Lady” he remarked that the power of the work lay in its “colossal suburbanism.” Now, “colossal suburbanism,” if it means anything at all, must surely signify “supreme dulness,” and this is exactly what we find in Mr Buchanan’s “new social drama.” The writer has certainly aimed high in the present case. His object has been to pen a biting satire upon Ibsen and all his works, a satire calculated to bring confusion to the souls of the Norwegian dramatist’s admirers, and to raise a shriek of laughter at their expense. But, unfortunately, an important ingredient has been left out of the composition of “The Gifted Lady.” Mr. Buchanan has forgotten the fun. Of heavily-laboured ridicule there is an abundance; of genuine wit not a scintilla. Imagine “The Colonel” with all the humour knocked out of it; substitute for the æsthetic craze which forms the pivot of that play Ibsen’s dramatic methods, and the personages of his various plots, and you have “The Gifted Lady.” It is not a farce—it is a burlesque; but a burlesque with no music, no dancing, no brightness, no merriment, no gaiety. An audience came to the Avenue Theatre last night ready to roar their ribs out over the witticisms which, according to report, were to flash meteor-like across the comparative dimness of the playhouse throughout the entire evening. But the sparkling jests were never spoken, and those who had made up their minds to laugh merely remained to titter spasmodically and with an effort, to yawn, and finally to doze. ___

The Standard (3 June, 1891 - p.9) AVENUE THEATRE. The fun of Mr. Robert Buchanan’s “new social drama,” The Gifted Lady, was somewhat discounted by the production of the merry little burlesque of Ibsen at Toole’s Theatre on Saturday afternoon. And, indeed, it had previously been, to no inconsiderable extent, anticipated by Mr. Burnand’s comedy The Colonel, and by Mr. W. S. Gilbert’s Patience; for the creatures of Ibsen are often only the æsthetic eccentrics of a few years since, with a difference. The reductio ad absurdum is very soon reached when the personages of the Norwegian dramatist are introduced; they and their phrases are easily and effectively parodied, and, though the plot of The Gifted Lady is neither strong nor really new, the piece answered its purpose in provoking very hearty laughter. The “gifted lady” is Mrs. Badalia Dangleton, wife of a dramatic author, and an author, moreover, of comic plays. She is emancipated—as likewise are her parlourmaid and page—and emancipated friends surround her, to the great annoyance of her husband. Badalia is attracted by what she regards as the genius of the poet, Algernon Wormwood, a fantastic impostor who had been a draper’s assistant before he adopted the new craze; and Wormwood frequents her house with two kindred spirits in Vitus Dance, the critic of the future, and Vergris, a French poet fin de siècle. The ridiculous airs and graces of Mrs. Dangleton, and the solemn impostures of Wormwood and his friends, are so dwelt upon as to fill out three acts; and there is also another emancipated being, Mrs. Felicia Strangeways, who kept a lodging-house at the seaside before her emancipation, and has deserted her seven children, including two recent twins—particularly avoided because twins are so conventional—to follow the footsteps of the ridiculous poet. “I had to do it—there was no other way!” is her excuse, and this characteristic Ibsenism never misses fire. Wormwood is seen at home in the second act. His dramas are rejected. One manager returns his masterpiece—it is explained that they are consecrated into masterpieces by the world’s rejection—with the cruel remark that the theatre does not want ventilation, but when it does he will be willing to treat for a piece so well calculated to take the roof off; and Wormwood at length determines to abandon emancipation, and try the drapery trade, which he does after an ugly encounter with Dangleton. Dangleton has meantime become—or has affected to become—Ibsenistic and uncomfortable, his wife perceives her folly, and finally recovers her senses. ___

The Daily Telegraph (3 June, 1891 - p.8) AVENUE THEATRE. Æstheticism, the worship of the sunflower, the tall lily, and the dado, resulted, as we all know, in a popular and highly-amusing play. No one can have forgotten Mr. Burnand’s “Colonel.” It was played for hundreds of nights in the now deserted Prince of Wales’ Theatre in the Tottenham-court-road, it was welcomed in the provinces, it made the fortune of Mr. Edgar Bruce, and it was acted at Abergeldie, at the command of his Royal Highness the Prince of Wales, before her Majesty the Queen. It naturally struck Mr. Robert Buchanan that the time had come for a new “Colonel.” Another craze has seized upon society with its microbic influence. Whence it came, or how it sprang, who shall say? It may be Schopenhauer, it may be Tolstoi, it may be pessimism, it may be Ibsenism, it may be nothingness, it may be Zolaism, or it may be a happy mixture of all this miscellaneous family. At any rate, there is a jargon. George du Maurier, in Punch, has, strange to say, passed it by; but our ears are dinned with a confused jumble of emancipated women, and the sublimity of selfishness, and the empire of egotism, and gifted ladies, and heredity, and so on to such an extent that a clever dramatist like Robert Buchanan naturally thinks that the time has come to give us another “Colonel,” with a new parade-ground. ___

The Scotsman (3 June, 1891 - p.7) This evening yet another burlesque on Ibsen was presented, for though the piece is aimed generally at “emancipated” men and women, incidentally it caricatures features not only of “The Doll’s House,” but of “Hedda Gabler” and of “Rosmersholm.” The title of the piece is “The Gifted Lady.” It is from the pen of Mr Robert Buchanan, and has seen the light for the first time at the Avenue. It is hardly possible to predict for it a long career. It has many smart, rememberable lines, but there is too much sameness in the satire for the purposes of three acts. Mr Buchanan tells a consecutive story, but it is so preposterous in itself that one cannot readily tolerate it for the two hours and a-half or thereabouts to which it ran to-night. Mr W. H. Vernon here plays the husband of an emancipated female (Miss Fanny Brough), who fancies she is in love with a draper turned poet—Mr Algernon Wormwood (Mr Harry Paulton.) Her husband, by way of turning the tables upon her, pretends to be also swayed by the theory she professes. In illustration of this, he makes violent love to his wife’s friend, and to her maid-servant. At length, exasperated beyond endurance by her husband’s irresponsible conduct, the wife repents of her old behaviour, gives up the “unconventional,” and falls back contentedly, and even happily, upon the commonplace. This, of course, is a mere skeleton of the plot, which is filled out with some ingenious characterisation and many bright incisive sayings aimed at the gospel of Ibsen and other foreign masters. The piece was to have been called “Heredity,” and that would have described it better than “The Gifted Lady,” which is too vague. It essays to do for the “individualistic” craze intensified by the Ibsenite propaganda what “The Colonel” did for the æsthetic craze; but the comparison is hardly favourable to Mr Buchanan, whose work lacks variety and vivacity. ___

St. James’s Gazette (3 June, 1891 - p.4) “THE GIFTED LADY” AT THE AVENUE. Mr. Robert Buchanan has delivered himself into the hands of his enemies. He has attempted to burlesque Ibsen, and in so doing has effectually shown that he can be even duller than the writer he sets forth to ridicule. True, he has got at his finger-ends all the jargon of the “new” school. He can prate of heredity, of individualism, of the evolution of the soul. He can introduce to us the emancipated woman, the critic of the future, the poet fin de siècle. But when he proceeds to deal with his material, to set his puppets in motion, the poverty of his stock-in-trade becomes at once apparent. It is all such vieux jeu; the thing has been done over and over again, and, if the truth must be told, so much better done. Mr. Burnand proved this in “The Colonel” and, not to mention other examples, Mr. Gilbert in “Patience.” In each instance the author gave us wit without vulgarity, fun without coarseness. Mr. Buchanan might have done worse than follow in their footsteps, for he, it is fairly obvious, “jokes wi’ deeficulty,” and certainly with no great sense of discrimination. His humour constantly strikes one as laboured, and if at times he does succeed in tickling “the ears of the groundlings,” it is by means which “cannot but make the judicious grieve.” Should any one doubt the accuracy of the statement, let him repair forthwith to the Avenue Theatre, where last night Mr. Buchanan’s new social drama, “The Gifted Lady,” was produced. In it he will find a mixture of French farce, English pantomime, and Norwegian clumsiness, not too skilfully mingled. Of the true spirit of travesty the piece possesses little or none, while the dialogue is sadly wanting in those essential qualities, brightness and polish. To relate the plot, such as there is, would be merely to recount a twice-told story. In short, Mr. Buchanan has gone forth to the fray armed with a bludgeon in place of a rapier; and his blows fall harmless, for the simple reason that he never gets within arm’s length of his antagonist. Not even the assistance given last night by a loyal band of followers could avail anything in the fight, labour howsoever gallantly they might. Miss Fanny Brough and Miss Cicely Richards did all in their power to arouse interest in Badalia Dangleton and Felicia Strangeways, two “emancipated women,” and it certainly was not their fault if their efforts failed to convince. Nor could Mr. W. H. Vernon, Mr. Harry Paulton, Mr. W. Lestocq, and Miss Lydia Cowell, despite all their cleverness, succeed in permanently vitalizing the “white donkey of Dangleton,” of which so much was heard and so little seen. Ibsen has been made responsible, no doubt deservedly, for much; but his crowning sin is to have inspired Mr. Buchanan to write “The Gifted Lady.” ___

The Globe (3 June, 1891 - p.3) “THE GIFTED LADY.” The end of a burlesque amuse and not to edify. A full recognition of this fact on the part of the author of “Ibsen’s Ghost” led at Toole’s Theatre to a brilliant success. Oblivion of it in the case of Mr. Robert Buchanan leaves “The Gifted Lady,” at the Avenue, poor hope of enduring triumph. Mr. Buchanan, it is true, does not call his piece a burlesque, but a new social drama, in three acts. A burlesque it is, all the same, of “Hedda Gabler,” with what may perhaps be called cross references to other plays of Ibsen. Others beside the author of “A Doll’s House,” are, however, included in Mr. Buchanan’s travesty. Russian novelists, French and English poets, critics of the future, divided skirts, and other eccentricities of modern development, are the subject of satire which fails neither in severity nor personality, and is parsimonious only in respect of fun. Hedda, who blossoms into Badalia, despises her husband because he writes farcical comedies; Felicia leaves her spouse on account of a rooted dislike to marriage tics. The former is cured on homœopathic principles by her husband, who, going beyond her in emancipation, clasps his housemaid to his breast; the latter is dismissed as incurable. Here is matter for one brisk act. When spun out into three it misses its effect and becomes depressing. Loyal service by Mr. Vernon, Miss Fanny Brough, Miss Cicely Richards, and Miss Lydia Cowell averted disaster, and secured a favourable recognition. No element of lasting vitality is, however, to be traced in a piece which is not very happily conceived, and is elaborate rather than clever in workmanship. The change of title is due to the fact of the former name, “Heredity,” having been claimed. ___

The Times (4 June, 1891 - p.13) AVENUE THEATRE. The best of jokes may be spoilt by over-elaboration, and this is a little the case with Mr. Robert Buchanan’s three-act burlesque of Ibsen which was given at the Avenue Theatre on Tuesday night under the title of The Gifted Lady. A terribly elaborate joke is that which takes two hours and a half in the telling. Obviously such a result can only be due to a considerable wandering away from the point at issue on the part of the narrator, and it is the fact that Mr. Buchanan frequently drifts from Ibsenism into ridicule of the æsthetic craze of a few years ago, reminding the spectator of The Colonel, and even of the French piece upon which The Colonel was founded, Le Mari à la Campagne. Heredity is the subject of some agreeable banter, but the string which Mr. Buchanan chiefly harps upon is the predilection of Ibsen’s female characters for individualism, for living their own lives in their own way, regardless of the interests of home or husband. The gifted lady who illustrates this thesis is in some degree a compound of Hedda Gabler and Nora Helmer, but her affinities are mainly with the wife who was satirized some forty years ago in the French piece above quoted. The society she affects is that of a dramatist, a poet, and a critic “of the future,” who are all précieux ridicules of as grotesque a stamp in their several ways as Mr. Burnand’s devotees of the sunflower. It is Miss Fanny Brough who takes the part of the “emancipated woman,” and she has often been seen to better advantage. Messrs. Paulton, Ivan Watson, and Lestocq are the male guys of the piece. Of them equally it may be said that in the long run they are quite as tiresome as they are satirical. We have also an emancipated housemaid in Miss Lydia Cowell, who wears a “divided skirt,” and another female monstrosity—this time of the Ibsen pattern—in Miss Cicely Richards, who makes up after the manner of Miss Marion Lea as Thea. The husband of the gifted lady—Mr. W. H. Vernon—it may be added, cures her of her folly by the time-honoured method of similia similibus curantur. He affects individualism too, and in the end his wife, who has meanwhile been disappointed in her æsthetic poet, finds it possible to live with a “funny man.” For the purposes of this last-mentioned joke, Mr. Buchanan, we hasten to say, is at pains to describe his hero as a writer of comedies and farces. The piece, it will be seen, is altogether too diffuse and too long-drawn-out. Compressed into one act its humour might be effective. But three acts of Mr. Robert Buchanan are not, on the whole, greatly preferable to three acts of Ibsen himself as an entertainment. __________ Somewhat late in the day Miss Norreys has essayed the part of Nora in A Doll’s House at the Criterion. She acted, of course, with intelligence, though accentuating, perhaps unduly, the frivolous and irresponsible side of the character, but there was nothing in the performance to correct the pretty general feeling that for the present we have had enough of Ibsen’s heroines. ___

The Stage (4 June, 1891 - p.9) LONDON THEATRES. THE AVENUE. On Tuesday evening, June 2, 1891, was produced at this theatre a new “social drama,” in three acts, written by Robert Buchanan, entitled:— The Gifted Lady. Charles Dangleton ... ... Mr. W. H. Vernon At the last moment the title of Mr. Buchanan’s piece had to be changed. It was Heredity, and it became The Gifted Lady. Fortunately, titles never matter much, as was shown, to quote one case among many, by that clever satire upon æstheticism, The Colonel, which ran hundreds of nights at the old Prince of Wales’s. On the face of it the programme does not indicate any intention on the author’s part of burlesquing Ibsen; but the action does not proceed very far before we became aware that in the “gifted lady,” who is played by Miss Fanny Brough, we have a compound of Hedda Gabler and Nora Helmer, while her emancipated sister, as embodied by Miss Cicely Richards, is a reflection of the Thea of Miss Marion Lea, jacket, hat, skirt, and general provincialism, all complete. We have mentioned The Colonel, and it is by no means an accident that Burnand’s amusing satire of the æsthetic should occur to the mind in this connection. Mr. Buchanan has been generally credited with the intention of burlesquing Ibsen, but the scope of his new piece is wider than that, embracing all sorts of crazes, from the longing for spiritual affinities to the exploitation of the divided skirt. While the two women specified are clearly of Ibsenian origin, their male counterparts are just as clearly æsthetes and bores of the sort satirised by Mr. Burnand, and of which a still earlier variety were dealt with in the piece upon which The Colonel was founded, namely The Serious Family, otherwise Le Mari à la Campagne, a comedy written by Bayard close upon fifty years ago. As in The Serious Family, too, the reform of the crazy heroine is gradually brought about by her husband, who, although downtrodden for a time, proves to be less of a fool than he looks. This husband in Mr. Buchanan’s piece is Charles Dangleton, described as a writer of comedies and farces, and so described in order to give the gifted lady an opportunity, which she is a little too prone to take advantage of, of saying that she “cannot live with a funny man.” If one more link of connection between this piece and Le Mari à la Campagne were needed, it would be found in the character of Doctor Plainchat, who advises his friend Dangleton to cure his wife of her folly on the homœopathic principle of similia similibus curantur—like cures like. There is such a character in Bayard’s comedy, through whose instrumentality the Colombet household, it will be remembered, is relieved of its incubus of Quakerism. Among the précieux ridicules of The Gifted Lady we note a playwright and a critic of the future, both long-haired, canting, and egotistical, and a French poet fin de siècle, who, like Lovborg in Hedda Gabler, is addicted to getting drunk. ___

The Morning Post (4 June, 1891 - p.5) AVENUE THEATRE. What the author, Mr. Robert Buchanan, calls a “social drama,” but what is really a burlesque, was produced on Tuesday night, under the title of “The Gifted Lady.” The fair heroine in question is the wife of a writer of farcical comedies, who has been attacked with the modern craze of “female emancipation.” She therefore becomes the associate of maudlin poets, French gutter writers, sham scientific men, and others of a similar stamp, the result being that she resolves to quit her “conventional home,” and with a great quantity of luggage flies to the garret of the poet, who has already become entangled with another “gifted lady,” and in reality would be glad to get rid of them both. In the hope of curing his wife the husband pretends to adopt her ideas, but when he too “seeks to be emancipated,” the silly woman sighs for her comfortable home, and begins to comprehend how foolish she has been. A reconciliation is brought about, and all the crack-brained fanatics are sent to Coventry. The fun of the subject is in the many incidents which are parodied from Ibsen’s dramas, but it must be confessed that the drollery of these ideas would have greater point if the play had not been extended to three acts. There was hearty laughter at times, and at the conclusion Mr. Buchanan was called for, and when he appeared received a cordial greeting. The acting of Mr. W. H. Vernon and Miss Fanny Brough had much to do with giving vitality to the author’s ideas, and Mr. Harry Paulton as the absurd poet was funny enough. Miss Cicely Richards and Miss Lydia Cowell were also excellent as one of the “gifted ladies” and as a servant who dons a “divided skirt.” The parody of Ibsen is frequently so close as to make some visitors wish that the author had been a less expert imitator, and when the curtain fell they must have felt that three acts of caricature were somewhat trying. ___

Glasgow Herald (4 June, 1891) MR ROBERT BUCHANAN’S new social drama, originally intended to be called “Hereditary,” has been rechristened “The Gifted Lady.” It is, as was expected, a skit upon Ibsen, although so slight a piece hardly bears spreading out over three acts. The wife of a dramatic author and her servants are all of the “emancipated” order, and so, too, are an ex- counter-jumper, Algernon Wormwood, who now poses as a poet, and has written Ibsenite plays, which are rejected by managers, and a lodging-house keeper, who has deserted her seven children mainly because two of them are twins, and twins are so conventional. Cut down into one or two acts “The Gifted Lady” would be more effective. It is at anyrate capitally played, and every point in which the Ibsen theories and dialogue are so whimsically parodied tells well. ___

The Nottingham Evening Post (4 June, 1891 - p.4) Mr. Robert Buchanan has written many things in his time, in fact he can be described as a prolific writer, especially for the stage, but it may be doubted whether he has ever written anything cleverer in its way than the three act skit on Ibsenism, entitled “The Gifted Lady,” produced last night at the Avenue Theatre. Mr. Buchanan made, however, one grand mistake, namely, to write the piece in three acts. The dialogue was brilliant in the extreme, but a good honest laugh at a new craze cannot be kept up for two hours. The skit should have been in one act, say about 45 minutes, in which case it would probably have become the rage of London. The author literally tears Ibsen to pieces; nothing is too sacred for him to ridicule. His sarcasm is biting, his satire is brilliant, and it is impossible to resist a roar of laughter. The success of last night was in no small measure due to the superb acting of Miss Fanny Brough, Mr. W. H. Vernon, and Mr. Harry Paulton, whom it is impossible to praise too highly. For an afterpiece, “The Gifted Lady,” when condensed, would be perfection. ___

The Dundee Evening Telegraph (4 June, 1891 - p.2) NOTES FROM LONDON. Mr Robert Buchanan’s new drama, “Heredity,” rechristened at the last moment “The Gifted Lady,” which made its first appearance at the Avenue Theatre last evening, is a noisy and desultory, but very amusing, burlesque of the men and women and ideas with which Ibsen’s plays have lately made us familiar. Of the characters two are “emancipated” ladies, one is an “emancipated housemaid,” one a “poet of the future,” another a “critic of the future,” and another a “French poet fin de siecle.” There is a boy in buttons who snorts like a steam-engine, a hereditary taint due to the fact that his father was a stoker on a locomotive. There is a maid servant with promiscuous tendernesses towards the male sex, inherited from her mother. The French poet has hereditary delirium tremens. In fact, with the exception of one or two, the whole of the dramatis personæ are fit subjects for the hospital or madhouse. The women desire to live free lives; they hate to be respectable, and throw off one husband and take on another with the most callous alacrity. The piece is in three acts, and though, dramatically, little can be said for it, it is written with extreme cleverness, and is full of smart and witty dialogue. The house—Ibsenites and all—seemed to take Mr Buchanan’s jokes in good part. It roared and roared again at the vagaries of the emancipated women, at the drunken French poet who wrote gutter verses, at the frantic talk of “the master,” and even at the snorting of the page. Miss Fannie Brough and Miss Cicely Richards gave a clever delineation of the emancipated ladies; while Mr Harry Paulton as the writer of great but always rejected plays, Mr Watson as the French poet, and Mr Lestocq as the critic of the future were admirably fitted. The piece was very well received, though from its evanescent character it can hardly be expected to have a long run. ___

The Era (6 June, 1891) THE LONDON THEATRES. THE AVENUE. Charles Dangleton ... ... Mr W. H. VERNON The audience which assembled at the Avenue Theatre on Tuesday evening last was in an excellent disposition, and thoroughly prepared to enjoy any fun which might be found in Mr Robert Buchanan’s skit upon Ibsen, which had been rechristened The Gifted Lady, the title of Heredity having been already claimed. The anti-Ibsenites were, of course, eager to see the follies of the “master” castigated with laughter; and even the admirers of the hirsute Scandinavian and his works were not disinclined to smile at a little—of course, pointless—ribaldry, provided that the said ribaldry was in itself amusing. But Mr Buchanan managed, long before the fall of the curtain, to bore and weary both parties. The satire proved dull, coarse, and elaborately facetious. The aim and object of a skit is to shoot folly as she flies. Mr Buchanan, instead of employing this method, has stalked his bird by a long and elaborate process, tedious to observe and painful to describe. However, as a matter of record, we must undertake the latter task. Charles Dangleton, author of farcical comedies, has married a wife, Badalia, who has become smitten with the Ibsen craze. He is hen-pecked, his buttons are not sown on, and his breakfast is interrupted by the visit, at an unconscionably early hour in the day, of Mrs Dangleton’s idols—Algernon Wormwood, a “poet of the future,” and Vergris, a French poet, evidently meant for Mr George Moore’s pet prodigy, Verlaine. The trio of visitors is completed by Vitus Dance, a critic, one of Wormwood’s worshippers. The great idea of the clique is not to be “conventional.” These characters may be said to belong to the domain of comedy. To that of bold burlesque we must allot the housemaid, Amelia, who, like the housekeeper in Rosmersholm, is secretly in love with her master, and that of the page, Biler, who has inherited from his father, an engine-driver, a habit of snorting noisily. The equivalent in The Gifted Lady of Mrs Elvsted in Hedda Gabler is Felicia Strangeways, a lady with “towy” hair, who has left her husband and family to devote herself to the worship of Wormwood, and who thus arouses the jealousy of Mrs Dangleton. Wormwood makes philosophic love to both women, and asks Badalia to fly with him. Dr. Plainchat, a friend of Dangleton’s, advises the latter to pretend to have adopted the Ibsen cult, and thus to encounter his wife’s friends upon their own ground. Before he can put this plan into practice Badalia informs him of her intention of leaving him, as she finds that she has been “living with a funny man;” and she goes off in imitation of the well-known scene in The Doll’s House. “THE VIPER ON THE HEARTH.” John Baxendale ... Mr J. L. SHINE The earnest sentiment of this lever de rideau was well brought out by Mr J. J. SHine, excellent as the generous, honest farmer, John Baxendale; by Miss Cicely Richards, really clever as the treacherous Hesketh Price; by Miss Eleanor May, who acted with sweetness and tenderness as Ethel Lydyard; and by Mr W. Lestocq as John Lydyard. Mr Ivan Watson is perhaps seen to better advantage in a character part than as a lover; but he did his work as George Heriot carefully and well. Unless Mr Lee can content himself with the patronage of part of the pit, the bill at the Avenue Theatre will soon have to be changed. ___

The Sheffield and Rotherham Independent (6 June, 1891 - p.5) Our Dramatic Correspondent writes:—The Ibsen craze was sputtering down to pale extinction, and would soon have ended like a malodorous tallow candle, without the aid of burlesque. To attempt to smother it with ridicule was a needless waste of effort. Sane people have not been bitten with the morbid silliness, and Ibsenity or Ibsenility has not excited more than a languid interest, for the most part contemptuous. Mr. Robert Buchanan has perpetrated a three-act extravagance which could not have attracted any popularity, even if it had been less ferocious and more amusing. But the “Gifted Lady” is not only a savage and somewhat clumsy attack upon Ibsenism, it also shoots arrows at many personages and things which Mr. Robert Buchanan dislikes, and has not the wit or sparkle to make such a performance piquant. So the venture at the Avenue Theatre runs no risk of being a financial success, or of stopping the way for any length of time. The Ibsen skit, which now merrily winds up the performance at Toole’s Theatre, on the contrary, is brief, bright, and amusing, without being in the least ill-natured. Though produced anonymously, it is the work of that clever young Scot, Mr. J. M. Barrie, whose “Window in Thrums” has delighted readers of The Speaker, and who promises to achieve front rank as a literary artist with a true vein of original humour. Miss Irene Vanbrugh, favourably known as a pretty and graceful exponent of light comedy, delighted and astonished her audience by her vivid burlesque of Miss Marion Lea and Miss Robins in “Hedda Gabler.” Mr. Shelton also distinguished himself as Tesman (“Fancy that!”) and Mr. Toole’s grotesque make-up as Ibsen was atrociously funny. It was worth while following a dose of the Ibsen bane, in order to be able to enjoy the drollery of the antidote. ___

Lloyd’s Weekly Newspaper (7 June, 1891) AVENUE THEATRE. While Mr. Toole has parodied Ibsen with song, dance, and grotesque make-up, Mr. Robert Buchanan has gone for him seriously in The Gifted Lady. Taking the idea of a flighty young wife, impressed with Ibsen matinées, he demonstrates in heavily-laboured fashion how she may be converted by the husband adopting the tu quoque. Mr. Buchanan very cleverly caricatures the teaching and language of the new creed, but his mistake is that he deals with farcical materials too seriously. The funniest thing though, is that he has demonstrated that one can be more unnatural than Ibsen. Mrs. Dangleton, represented by Miss Fanny Brough, one of our most vivacious actresses, leaves her comfortable home—more trying to her than deserting her husband—to seek the poor lodgings of Algernon Wormwood, described as a poet of the future. There is little of the Bunthorne in Mr. Harry Paulton’s conception of the poet, and the actor hardly seems at home. Associated with him are two other poets, boasting such artificial names as Vitus Dance and Vergris. The latter, who is always drunk, yet manages to entice Mrs. Strangeways (what originality of nomenclature!) from her home and twins. These materials are wielded inoffensively by Mr. Buchanan, for everybody talks and very little is done. The husband of Mrs. Dangleton (Mr. W. H. Vernon) is the busiest man of the play, and his flirtation with the little servant girl in a “divided skirt” (a part capitally played by Miss Lydia Cowell) is one of the funniest situations among the few in the play. At the production of the satire on Tuesday the author received a special call; but, all the same, The Gifted Lady is a very heavy subject for the Avenue. ___

The Referee (7 June, 1891 - pp.2-3) Now the “miracle of miracles,” as they say in “A Doll’s House,” has happened. Upon a subject rich in humorous suggestion, an author of approved talent has written a play which is extremely dull and extremely stupid. Not to put too fine a point upon it, Mr. Robert Buchanan’s new piece, produced at the Avenue on Tuesday evening, is no less unacceptable than the dramas of Dr. Ibsen which “The Gifted Lady” is designed to ridicule. The humour is of the ponderous order which finds expression in frequent jokes about dyed hair and twins, and other things as choice, and the satire upon the crazy themes of the Scandinavian dramatist is of much the same quality. Heredity, which was to have given a name to the play, is made to yield some poor fun, and Mr. Buchanan can get nothing more laughable out of the dramas of Dr. Ibsen than a little ridicule of such cryptic phrases as “living one’s one life,” and some rather pointless jesting about a White Donkey, which is supposed to be a comic perversion of the preposterous apparition in “Rosmersholm.” In sum, Mr. Buchanan has mixed too much water with his wine. He has missed his chance. Not that it matters much, for, in spite of all the chatter about “the Master,” Ibsen’s plays, I maintain, are no more familiar to the generality of playgoers than the comedies of Plautus. “The Gifted Lady” may be described, in the language of the stud book, as by “The Serious Family” out of “Le Mari à la Campagne,” and an own brother to “The Colonel.” Badalia Dangleton’s wife is “emancipated,” and, to cure her of her fancy for the beautifully hideous Algernon Wormwood, “the poet of the future,” her husband “emancipates” himself, and whilst she is, figuratively speaking, eating the husks of swine with the poet and his ragged associates, he keeps company with Badalia’s bosom friend, Felicia Strangeways, and his own pretty housemaid, a sympathetic creature with hereditary tendency to tears. After three acts of more or less perfunctory fooling, Mr. Dangleton’s reprisals bring his wife again to her senses and her husband’s arms. I have nothing to say of the acting, and that is all there is to be said about it, for Mr. Harry Paulton, Mr. Vernon, Miss Fanny Brough, Miss Cicely Richards, Miss Lydia Cowell, and others concerned ought not under the circumstances to be criticised. Yet, with all its faults, the piece was received with unbounded applause. ___

The People (7 June, 1891 - p.6) AVENUE. Playgoers who desire to realise for themselves the essential difference between spontaneous natural humour and its strained artificial counterfeit have only to see the two travesties of Ibsen’s dramatic plots and characters severally on show at Toole’s and at the Avenue. While the former teems with exquisite fun in every line of playfully sarcastic allusion, the latter, given for the first time at the Embankment playhouse on Tuesday night, drags its slow length along through three such acts of dulness and sheer stupidity as have never been exceeded, even by Mr. Robert Buchanan. Such plot as there is in the piece called “The Gifted Lady,” which, though styled in the programme a social drama, is nothing more or less than a buffooning burlesque, presents the hackneyed, stale incident of a husband henpecked by a shrewish wife, whose temper, taking the most extravagant form of Ibsenitish selfishness and unwomanly wantonness, prompts him to turn the tables upon his home wrecker by pretending to be suddenly converted to her social doctrines. Carrying out this marital stratagem, the husband puts these new ethics in all their bald rankness into practice before his wife’s face by hugging and kissing the cook, even as her mistress had previously done the like to her favourite poet; and, by this means, finally succeeds in curing the shrew’s splenetic affectation by exciting her jealousy. First the wife and then the husband seen sprawling on the floor, each hugging, not simply one, but two illegitimate lovers, presented coarse displays of amorous grossness which, as a subject lesson in morals, were certainly too disgusting to deprave. It was pitiful, however, to look upon an actress of the high quality of Miss Fanny Brough suffering eclipse of her wonted humour by the hideous vulgarity of the character she had to impersonate so as to render her presence not only distasteful but disagreeable. In the same way, Mr. Paulton, identified by the playwright’s personalities with an eminent living poet, had no trace left of that quaintness which in other impersonations renders his acting so diverting. Other excellent histrionic ministers to pleasure under fair ordinary conditions, whose ill fate made them exponents of Mr. Buchanan’s wearisome stuff were Messrs. W. H. Vernon, and Lestocq, with Mesdames C. Richards ad L. Cowell. Called for at the fall of the curtain, the author on appearing was greeted with sounds neutralising each other. _____________________________ TOOLE’S. The proverbial soul of good in things evil has at last been discovered in Ibsen’s plays, which must have been designed by their author merely as vehicles for burlesque. For assuredly a funnier and more original skit has never tickled an audience into fits of laughter than the “new Hedda,” entitled “Ibsen’s Ghost; or, Toole Up to Date,” seen on the 30th ult. at the “datist’s” little playhouse. Ignoring, in the best of taste, the repulsive features of Ibsenity, the eccentric inversions of human nature shown in its morbid pessimism are, in all their extravagance, held up to the ridicule at once invited and deserved by them. For example, Miss Eliza Johnstone, as the middle-aged wife of the Gabler dramatist—himself travestied to the life by Mr. Toole—overwhelms her mock husband with bitterly scornful reproaches because he has never once throughout their twenty years of wedlock introduced to his hearth and home a single wicked man; no, nor even a married wicked man; moreover his goodness has so worn her life out with monotonous marital faithfulness that nothing is left her weary soul, if she had a soul, but to free it by suicide from the detestable thrall of love. Another Ibsen craze. The bane of heredity is amusingly exemplified by a younger wife, who wrathfully denounces her grandfather for having transmitted to her the irrepressible desire to kiss every loathed male creature she meets. The old Cabler—Mr. Toole again—deploring this taint of nature seen in his granddaughter, accounts for it by having in early life been cruelly shut up in the dark with a pretty girl. The artistic embodiment of flabby inanity given by Miss Marion Lea and of rabid insanity expressed by Miss Robins in their several impersonations lately in the happily defunct “Hedda Gabler,” were humorously mimicked by Miss Irene Vanbrugh as the ever kissing wife, the part of the foolish husband who so fondly encourages her in this general osculation being taken with comic effect by Mr. George Shelton. Honestly “showing true things by what their mockeries be,” the travestie eliciting a rippling accompaniment of laughter throughout, runs its merry, humorous, and generally critical course through the merriest half-hour enjoyed by playgoers for many years. Mr. Toole, in announcing the skit for repetition nightly, tantalised his friends in front by withholding from them the name of the author. ___

The Yorkshire Herald (8 June, 1891 - p.6) Rumours of burlesques on Ibsen have been rife during the past few weeks, but Mr. J. L. Toole has distanced all competitors by producing, on the 30th ult., a “new Hedda in one act,” entitled “Ibsen’s Ghost; or, Toole Up to Date,” a very amusing travesty, in which the salient points of the “emancipated” drama are cleverly satirised. Heredity is the chief subject of the skit, but it is not an inheritance of vice which distresses the heroine, but a dreadful tendency to kiss everybody, resulting from her grandfather having perpetrated the crime of thus “saluting” a pretty bridesmaid on his wedding day, some 40 years before. There are also a few suggestions of “ghosts” in the parody, which terminates with the “beautiful” suicide by popgun of the whole of the characters. Miss Irene Vanbrugh, as a lady unable to find a husband she can live with for any length of time, mimics the Vaudeville representatives of Thea Tesman and Hedda Gabbler very successfully, and Mr. George Shelton is very happy in his caricature of Mr. Scott Buist’s Tesman, while Mr. Toole, whose “make up” to the familiar portrait of the hirsute Dr. Ibsen is wonderfully good, is extremely diverting as the conscience haunted grandfather, and Miss Eliza Johnstone as his “doll-wife,” who yearns to live her own life, is amusing in a small part. Both in dialogue and details of “business” the piece is exceedingly smart, and it was received with roars of laughter. A call for the author brought Mr. Toole before the curtain at the close, but only to disappoint public curiosity by the announcement that “Mr. Ibsen was not in the house!” The burlesque was preceded by Byron’s well-known comedy, “Chawles; or a Fool and his Money,” in which Mr. Toole, of course, played Chawles. ___

Truth (11 June, 1891 - p.26) ROUND THE THEATRES. Old Ibsen is as dead as a door-nail. He was a “bogey” at the best—a turnip on the top of a long pole, disguised with a sheet, and perhaps now all has been said and done, he may have been some slight service in persuading the dramatists of the future that they must take a little more trouble, that the old tunes they have been playing for scores of years are becoming a little stale, and that there is just this much truth about “educated audiences,” that the drama and the dramatic art are studied more seriously and earnestly than they used to be. But let not the satirists and burlesque writers lay the flattering unction to their soul that it was they who killed this perky old Cock Robin. Who killed Cock Robin? Well, it was not even clever Mr. J. M. Barrie, and I am sure it was not Robert Buchanan, whose elephantine humour has managed to empty the Avenue Theatre even more surely than Ibsen himself would have done. It required all the nervous energy of Miss Fanny Brough, all the well-tried expression of Mr. W. H. Vernon, all the good-will of Miss Cicely Richards, and all the comic sparkle of Miss Lydia Cowell, an actress far too little appreciated but always successful, to pull along the heavy, lumbering, advertising chariot on which Buchanan had plastered his posters. The poor people dragged the van to the end of the journey, and then sank down exhausted. From that exhaustion they have never recovered. The thing placarded beforehand as the wittiest play imaginable, has turned out the dullest one conceivable. The new theatre and the new drama, and the free theatre, and the independent drama may be hovering over us in the near future. There may be wild enthusiasts who believe that M. Antoine will revolutionise and subjugate the countrymen of Molière and Corneille and Dumas. There may be fanatics who conceive that the descendants of Shakespeare and Sheridan will be dictated to and taught to go to Mr. Holland for inspiration by Mr. Grein. There may be cranks who are confident that English taste will veer or turn towards the drama of the hospital ward and the comedy of free love. But one thing will certainly not happen. On this point it is not rash at all to prophesy. The time will never come when the public will accept as plays, satires, or burlesques the brilliant letters of Robert Buchanan destined for the Daily Telegraph, but cut up into acts and scenes for the modern stage. Journalism and play-writing are distinct vocations. Buchanan may be a bruiser, but he is no distinct success as a dramatist. He cannot, for the life of him, let his latest or even his oldest enemy alone. He must drag in Algernon Charles Swinburne, and continue in the category of quarrels till he comes to his last pet aversion in critics—William Archer. All this may be fun to Buchanan, but it is death to the holder of a half-guinea stall. It is not very pleasant after a good dinner to be treated to a scientific explanation by Ibsen of the treatment exercised in a certain excellent institution in the Harrow-road, and to my mind it is far more pleasant to read the views of Mr. J. F. Nisbet on hereditary genius and eccentricity in a comfortable chair in the club than to be bored with the dramatised lectures of a narrow-minded old Scandinavian bore. The new theatre may be this, that, or the other. But it certainly will not be converted by Robert Buchanan when he has cast aside his tomahawk and put on his fool’s-cap. As well demand a comic play from those amiable controversialists, Lord Bramwell, Lord Grimthorpe, and Professor Huxley. ___

The Pall Mall Gazette (16 June, 1891) Painfully brief, but for all that some seven nights too long, was the run of “The Gifted Lady” at the Avenue. I wonder if this last dire fiasco will serve to convince Mr. Robert Buchanan of the utter futility of attempting to foist mere empty trash upon the play-going public under the shelter of a name of some literary repute. I should have thought that this writer was a sufficiently able man to perceive the suicidal tendency of such a course. But it seems not. How long will he continue in his present perverse frame of mind? Let me echo the admonition given so often by pretty Dorothy Bantam to the matrimonially-inclined Phyllis Tuppitt, and say, “Be warned in time.” ___

Ally Sloper’s Half-Holiday (20 June, 1891 - p.6) Ibsen’s Ghost, now being played at Toole’s Theatre, is the title of an exceedingly clever satire upon the ethics of the celebrated Norwegian playwright. Even to those unfamiliar with the works of the “master,” the parody cannot fail to prove a source of infinite merriment, whilst keen indeed will be the enjoyment of those acquainted with the “views of the great realist.” Mr. Toole, as Peter Terence, causes roars of laughter; and Miss Irene Vanbrugh, a lady whose appearance is as charming as her power of mimicry is clever, deserves the highest praise for her spirited acting. . . . THAT Mr. Robert Buchanan is a very clever man we think few people would deny. Unfortunately, like many another, he has enemies, and the production of a play, of which he is the author, is at once the signal for a furious onslaught upon him; for, under the veil of criticism, his foes can say all the nasty things they like of him, and vent their petty spite with impunity. Mr. Buchanan’s latest production, entitled A Gifted Lady, and which was produced recently at the Avenue, is as clever a satire upon the works of Dr. Ibsen as it is possible to write. It is a much more ambitious effort than Mr. Barrie’s little skit now being played at Toole’s, and it consequently takes longer to play, and this is its weak point. There is not sufficient material to spread out over three acts, and this “new social drama,” therefore, is alternately dull and brilliant. With the cause of the dull portions eliminated, A Gifted Lady would go accompanied with one long scream of laughter from beginning to end, and attract good audiences to the Avenue for months to come. ___

The Theatre (1 July, 1891) “THE GIFTED LADY.” A new social drama, in three acts, by ROBERT BUCHANAN. Charles Dangleton ... (Dramatic Author) ... Mr. W. H. Vernon. Time—The present day. Scene—London. AUTHOR’S NOTE.—In venturing to present to English audiences the last great Social Drama of Eric Pluddermund, I have taken two daring liberties, by transferring the scene to London, and by altering the tragic ending. In the original, as every student of the master knows, Badalia and Grönost (the Algernon of my adaptation) hang themselves together in the linen closet, while Felicia and Amelia emigrate to Utah with the hero. For the rest I have followed the spirit of the original as reverently as the Lord Chamberlain would allow me. The power of the work lies in its colossal suburbanism, and in its savage satire of the master’s own theories of feminine emancipation. Pluddermund has the supreme artistic merit of eternally contradicting himself as well as everybody else; hence his soubriquet of “The Chameleon.” If the present serious play meets with approval, I propose to follow it with one of Pluddermund’s humorous pieces; some of his admirers, however see a certain grim humour in Arvegods (Heredity).—ROBERT BUCHANAN. Mr. Robert Buchanan’s intended or supposed skit upon Ibsen may be dismissed in a few words, for it was not a travesty of the Norwegian dramatist’s work, or of any work in particular. It was very dull, and gave one the impression of having been written in order to show up the supposed weaknesses or peculiarities of all those of whom Mr. Buchanan disapproves, or of whom he has a poor opinion. Badalia Dangleton having developed extraordinary ideas on the subject of the emancipation of women, and having constantly expressed her regret at having married “a funny man,” runs after Algernon Wormwood, and proposes to live platonically with him. Her husband, Charles Dangleton, adopts the homœopathic treatment of philandering with his pretty servant Amelia, and with Felicia Strangeways, a married woman, who has also left her husband “for the sake of Wormwood.” It need only be said that everyone in the cast worked so hard and effectually that they saved the piece from utter condemnation. The funniest thing in the whole play was the appearance of the emancipated housemaid in the divided skirt. ___

From Dramatic Notes: A Year Book of The Stage by Cecil Howard (London: Hutchinson and Co., 1892 - pp. 118-119) [June] 2nd. AVENUE.—The Gifted Lady. There was some little difficulty as to using Heredity as the title for his new play, and so Robert Buchanan called his three-act “social drama” The Gifted Lady. Drama it was not, neither was it farce, nor was it burlesque. It was intended, I suppose, to satirise the cult of Ibsen and to ridicule his works, and, if I am right in my conjecture, it was not cleverly done, for the piece was dull, the writing commonplace, and the entire work not in good taste. Mr. Buchanan took the opportunity of letting out at one and all who have “trod on the tail of his coat”; but he hit with a bludgeon, and did not pink with the sharp, incisive touch of a rapier. Under the guise of a story of a good fellow whose home is destroyed through the “emancipated” ideas of his wife, he makes the husband turn the tables on his spouse by pretending to follow her course; and thus he cures her. In one act of thirty minutes the idea could have been made amusing; but, as it was, the subsequent hour and a half only brought weariness of the flesh and vexation of spirit. W. H. Vernon and Fanny Brough, as Charles and Badalia Dangleton, by their inimitable “go,” saved the play from becoming utterly boring; and they had good aid from Harry Paulton as Algernon Wormwood, Cicely Richards (Felicia Strangeways) (excellent in her travesty of Thea and her flaxen locks), Ivan Watson (Vergris), and Lydia Cowell as Amelia (an emancipated housemaid). With reference to The Gifted Lady, the following was printed on the programme:— |

|

|

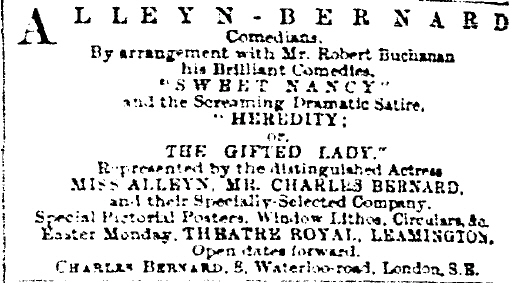

[From The Stage (5 May, 1892 - p. 18).]

From R. D. B.’s Diary 1887-1914 by R. D. Blumenfeld (William Heinemann, 1930) (pp.46-47) It is becoming increasingly difficult to find variety in restaurants at night. There are only three or four to choose from. So a few of us—Thomas Fielders, Captain Montagu Armstrong, Romeo Johnson, of the U.S. Consulate, henry Lee, lessee of the Avenue Theatre, and myself—have taken 34, Grosvenor Road, in Westminster, next to the Millbank Prison, the place from which they used to ship the miscreants on board the Thames to Botany Bay. It is a row of new houses, and you have to pass through a road of slum houses in front of Smith Square and Grosvenor Road, The house, which is beautifully fitted out, belongs to a solicitor named Wilkins, and he has let it to us furnished at seven guineas a week. We have engaged a housekeeper and staff. Turner, my servant, is to be the butler, and we take possession to-morrow, so that we shall have a family group with a dinner party every night. Henry Lee assumes the responsibility for the house, and we pay him six guineas each per week—extra for wines and cigars. Lee has just produced Monte Cristo at the Avenue Theatre, with Charles Warner and Emily Milward in the leading rôles. *A true prophecy. Lee’s management lasted only a few weeks more. ___

‘Critical and Popular Reaction to Ibsen in England; 1872-1906’, a 1984 doctoral thesis by Tracy Cecile Davis from the University of Warwick is available online and includes several mentions of Robert Buchanan and The Gifted Lady (Lord Chamberlain's Plays, Number 53475, lic. 133), including this plot summary: “The play is about two emancipated free-thinkers, Badalia Dangleton (Hedda Gabler) and Felicia Strangeways (Thea Elvsted), who independently form alliances with Algernon Wormwood, a poet of the “modern horrible school.” Wormwood is encouraged by a critic named Vitus Dance (V.D.), who believes that the work of this “poet of the Morgue” will lead to a new sort of writing, “circumscribed to its true function — it will no longer deal with subjects . . . . It will have no more meaning than a chord, no more personality than an influenza.” Badalia’s husband, Charles (Torvald Helmer/George Tesman), is not in sympathy with her advanced views, so she leaves him to enter into a relationship with Wormwood: after all, “a woman’s duty is to herself, and to her dress-maker,” and besides, Charles makes his living as a writer of conventional comedies, and “no man who respected himself would write a play which could run more than five nights, or would condescend on any terms to be amusing!” In the second act, Wormwood is pursued by the “White Donkeys of Dangleton.” After Charles attends a performance of the Independent Theatre Society he is convinced that his own emancipation can only be complete if he murders someone or commits suicide; furthermore, it is rumoured that he would only be satisfied if Wormwood and Badalia drowned themselves in the mill race. To complicate matters, Charles discovers that his great-great grandfather was a polygamist and his uncle married a cook, so Charles offers to trade his own wife for Felicia (who has also abandoned her husband to live with Wormwood), and buys his housemaid a fancy hat and a divided skirt. Between the second and third acts, Wormwood is offered a position at a drapery warehouse in Birmingham, and goes there to marry the draper’s daughter and live a philistine existence. In Act III, Felicia returns to her husband. Badalia, too, goes home, longing for the return of normality and her husband’s affection, but he has only delved further into his emancipation. He spent a delightful evening eating asparagus at his club and exploring the dissecting room of the University Hospital. In the final moment, he whistles a meaningless tune — this magically cures him of his mania and reconciles him with his wife. Vitus Dance, the critic of the future, goes to Gatti's to efface himself.” _____

Next: The Trumpet Call (1891) Back to the Bibliography or the Plays

|

|

|

|

|

|

|