|

Play List: 4. Corinne 7. The Mormons 9. Lucy Brandon 10. Storm-Beaten 11. Lady Clare 13. Bachelors 14. Constance 15. Lottie 16. Agnes 17. Alone in London 18. Sophia 19. Fascination 20. The Blue Bells of Scotland 21. Partners 24. Angelina! 25. The Old Home 26. A Man’s Shadow 27. Theodora 29. Clarissa 30. Miss Tomboy 32. Sweet Nancy 33. The English Rose 36. Marmion 37. The Gifted Lady 38. The Trumpet Call 39. Squire Kate 40. The White Rose 42. The Black Domino 44. The Charlatan 45. Dick Sheridan 47. Lady Gladys 48. The Strange Adventures of Miss Brown 49. The Romance of the Shopwalker 52. Two Little Maids from School ___ |

|

ROBERT WILLIAMS BUCHANAN (1841 - 1901) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

THEATRE REVIEWS 46. A Society Butterfly (1894)

A Society Butterfly The failure of A Society Butterfly led directly to Buchanan’s bankruptcy, the newspaper accounts of which are available in the Buchanan and the Law section. An account of the origins of the play and the reasons for its failure is included in Henry Murray’s memoir, A Stepson of Fortune. |

|

|

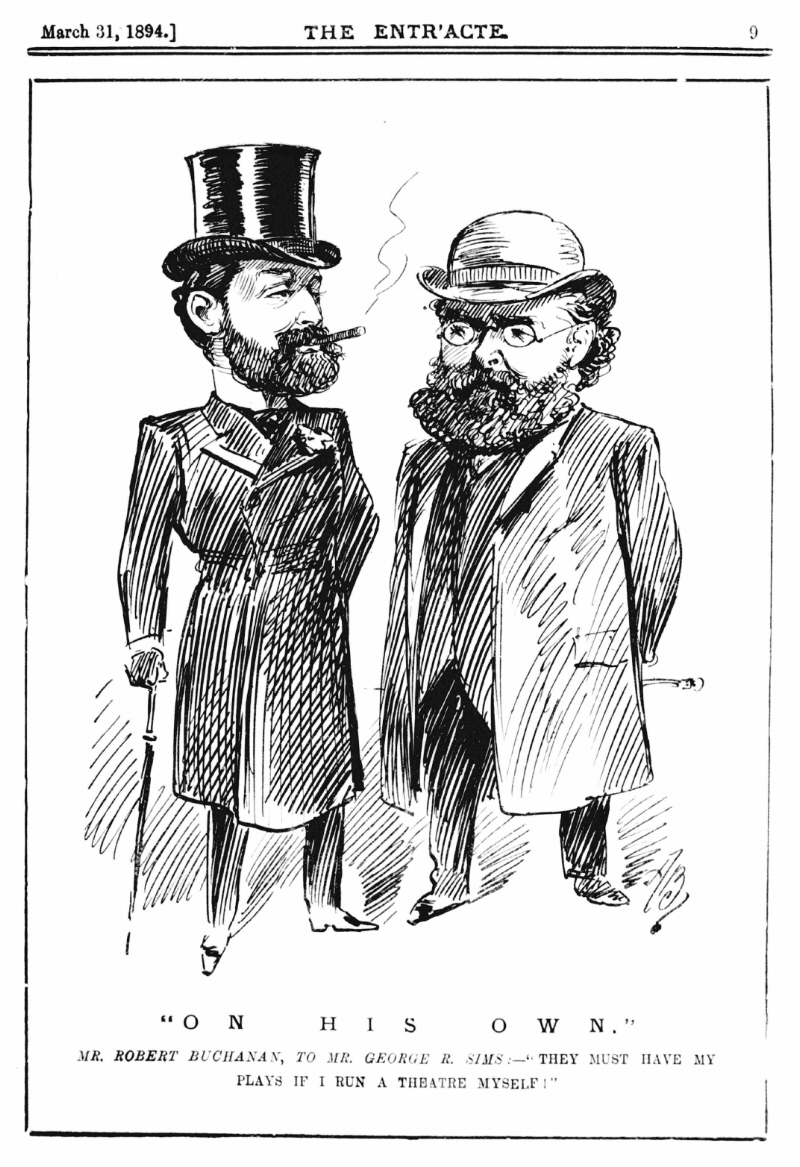

The Penny Illustrated Paper (31 March, 1894) |

|

|

Mrs. Langtry, who is about to re-appear in a play by Mr. Robert Buchanan at the Opéra Comique in London, though she has passed that trying age of forty, is still a beautiful woman. Her father, the Rev. W. C. Le Breton, was the Dean of Jersey, and hence her nickname in later years, “the Jersey Lily.” She was born in 1853, and married in 1875, Mr. Langtry, a member of the diplomatic service, who is now a quiet country gentleman in the Midlands. Soon after her marriage, Mrs. Langtry became a prominent society woman. She was the first of “the professional beauties,” and all London swarmed with her photographs. In 1881 she decided to go on the stage, obtaining much advice and assistance from Mrs. Henry Labouchere, who, as Miss Henrietta Hodson, has been an actress of mark. Mrs. Langtry first appeared as Kate Hardcastle in “She Stoops to Conquer” at the Haymarket. She toured in America, and accumulated, it is said, a large fortune, partly invested in an American cattle ranche. Mrs. Langtry has been yachting in the Mediterranean, and been seen at the last Covent Garden Fancy Dress Ball. ___

The Glasgow Herald (2 April, 1894 - p.9) Mr Robert Buchanan has now signed the lease of the Opera Comique, where, as soon as possible after next Saturday, when his tenancy begins, he will produce a play of his own, which in due course will be followed by one from the pen of Mr Christie Murray. In Mr Buchanan’s piece Mrs Langtry will take the principal part. It is said that she will be paid the very high salary of £100 a week, £800 being deposited in advance. ___

The Coventry Herald and Free Press (6 April, 1894 - p.3) LONDON CORRESPONDENCE. It is pretty well known that Mr. Robert Buchanan has been for some time looking out for a theatre in which to produce his own and other plays. He has at last closed with the proprietors of the Opera Comique, and the rent for the first month (£260) has been paid. It is reported that Mrs. Langtry has been secured by the Bard for leading lady, and it is even said, though this must be accepted with a liberal allowance of salt, that the Jersey Lily will receive a salary of £100 per week. ___

Manitoba Morning Free Press (7 April, 1894 - p.5) Mrs. Langtry is likely soon to reappear on the London stage. Robert Buchanan has engaged her for a new venture he has in hand. Desirous of becoming a manager on his own account, he has taken the Opera Comique theatre with the intention of producing an adaption of one of his own novels and also a new work by David Christie Murray, the novelist. Mrs. Langtry will play in these pieces. ___

Northern Daily Mail (7 April, 1894 - p.6) MY DRAMATIC TRAWL-NET. . . . The new play with which Mr Robert Buchanan will start business shortly at the Opéra Comique is by R. B. and Mr Henry Murray. It is in four acts, and deals entirely with English fashionable life. In this Mrs Langtry will make her reappearance on the London stage. ___

The Birmingham Daily Post (7 April, 1894 - p.7) There is no foundation for the report that Mrs. Langtry will appear at the Opera Comique in the new play by Mr. Robert Buchanan, which the dramatist will produce at that theatre under his own management. She will make her rentree at the Royalty Theatre, which will reopen shortly under the management of Mr. Charles Hawtrey. ___

The Dundee Evening Telegraph (9 April, 1894 - p.2) Rumour says that Mrs Langtry’s agreement to appear as leading lady during Mr Robert Buchanan’s season at the Opera Comique provided for a weekly payment of £80. Does any other actress draw so large a salary? ___

Advertiser for Somerset (12 April, 1894 - p.7) MRS. LANGTRY’S SALARY.—Mrs. Langtry, Figaro states, will be paid the tolerably handsome salary of £100 a week (eight weeks being guaranteed and paid in advance) as leading actress in Mr. Robert Buchanan’s new enterprise at the Opera Comique. Out of this sum, however, the Jersey Lily provides her own dresses, which, on the signing of the contract last Thursday, she forthwith ordered from Worth, of Paris. On the other hand, the Evening News and Post says Mrs. Langtry does not join Mr. Robert Buchanan at the Opera Comique. She has, according to this authority, arranged to appear in about a fortnight at the Royalty with Mr. Charles Hawtrey. ___

The Nottingham Evening Post (16 April, 1894 - p.2) MRS. LANGTRY’S NEW PLAY. The title of the new play, in which Mrs. Langtry is to exhibit her talent, her personal attractions, and her new gowns at the Opera Comique is, we understand, not yet definitely settled. Titles rarely are till the question of whether there are prior claims has been settled. At present Mr. Robert Buchanan and his collaborator, Mr. Henry Murray, incline to entomological labellings for their four acts, which are to be distinguished respectively as “The Chrysalis,” “Wings Expanding,” “The Butterfly,” “Folded Wings.” ___

The Taunton Courier (18 April, 1894 - p.2) MRS. LANGTRY, long absent from this country, will appear as leading lady during Mr. Robert Buchanan’s season at the Opera Comique for a weekly payment of £80. Does any actress draw so large a salary? There are several actors in receipt of more. In one case an actor receives £120 a week (Arthur Roberts to wit), and there are several who receive £100. It is curious that a successful actor should command a larger salary than a successful actress, but such is the case. ___

The Stage (19 April, 1894 - p.11) It has not been definitely settled what the title of the new play by Robert Buchanan and H. Murray, to be produced at the Opera Comique, shall be. There is at present some idea of calling it A Society Butterfly, a title which should fairly well meet the requirements of the plot, as far as I know it. However, the theatre will be opened with this piece on or about Thursday, May 3, and in the cast you will find Mrs. Langtry, Miss Rose Leclercq, Miss Eva Williams, Mr. Fred Kerr, Mr. C. P. Little, Mr. Charles Stuart, Mr. C. Mowbray (stage-manager), and, possibly, Mr. W. Herbert. The piece is in five acts, and is an up-to-date comedy. Miss Leclercq will appear as a sporting Duchess, and Mrs. Langtry will be the Butterfly. In one act the Jersey Lily will be found clad as a Grecian goddess, taking part in private theatricals. Rehearsals have been started, and all appears to be shaping well. ___

The Westminster Budget (20 April, 1894 - p.26) There is no foundation for the report that Mrs. Langtry will appear at the Opera Comique in the new play by Mr. Robert Buchanan, which the dramatist will produce at that theatre under his own management. She will make her rentrée at the Royalty Theatre, which will reopen shortly under the management of Mr. Charles Hawtrey. Mrs. Langtry, who has not been seen on the stage for some time, has lately, we understand, refused a handsome offer from the management of the Empire Theatre, who wished to secure her services for their tableaux-vivants. Her next appearance will be in light comedy. ___

The Echo (20 April, 1894 - p.1) THEATRICAL GOSSIP. The Opera Comique is to open on or about the 3rd prox. with a new play by Messrs. Robert Buchanan and Henry Murray, entitled, it is most likely, The Society Butterfly, in which Mrs. Langtry will take the lead. The lintels of the theatre are already billed with announcements of Mrs. Langtry’s re-appearance. ___

The Glasgow Herald (23 April, 1894 - p.9) The new piece by Mr H. Murray and himself, with which Mr Robert Buchanan will reopen the Opera Comique on May 5, has now been christened “The Society Butterfly,” and, despite conflicting reports, the part of the “Butterfly” will be created by Mrs Langtry, who in the second act will appear as Venus in some society tableaux-vivants supposed to be given in the drawing-room of a lady of title. Another character is that of a horse-racing duchess, a part which will suit Miss Rose Leclercq admirably. ___

The Echo (24 April, 1894 - p.1) Despite sundry rumours about a migration to the Princess’s, Mr. Robert Buchanan will abide by his original choice of a theatre and will open the Opera Comique in about three weeks’ time with the new Society comedy which he has written in collaboration with Mr. Henry Murray, brother of the better-known novelist, Mr. David Christie Murray. The title, though hardly finally fixed upon, will probably be A Society Butterfly. Experienced playgoers will probably be able to gather some notion of the drift of the story from the subtitles with which the authors have supplied each of the acts. They are “The Chrysalis,” “Wings Expanding,” “The Butterfly,” and “Folding Wings.” Mrs. Langtry will, of course, appear as the heroine, and the cast will also include Miss Rose Leclerq and Mr. William Herbert. ___

The Stage (3 May, 1894 - p.11) Next Thursday evening the Opera Comique will be opened with the production of Robert Buchanan and Henry Murray’s new four-act comedy of modern life, called A Society Butterfly. The cast will be as follows:—Mr. Charles Dudley, Mr. William Herbert; Dr. Coppee, Mr. Allan Beaumont; Captain Belton, Mr. F. Kerr; Lord Augustus Leith, Mr. Edward Rose; Major Craigeldie, Mr. Henry J. Carvill; Lord Ventnor, Mr. S. Jerram; Herr Max, Mr. Templeton; Bangle, Mr. Chas. R. Stuart; the Duchess of Newhaven, Miss Rose Leclercq; Lady Milwood, Miss Walsingham; Hon. Mrs. Stanley, Miss Lyddie Morand; Mrs. Courtlandt Parke, Miss E. B. Sheridan; Miss Staten, Miss Ethel Norton; Rose, Miss Eva Williams; Marsh, Miss Eva Vernon; Mrs. Dudley, Mrs. Langtry. At one portion of the play, as I have already told you, private theatricals will be indulged in. This scene the authors have termed an “Intermezzo.” The cast of characters in this will be:—Queen of Heaven, Miss Walsingham; Pallas (Goddess of Wisdom), Miss Lyddie Morand; Œnone, Miss Gladys Evisson; Paris, Mr. F. Kerr; Aphrodite (Goddess of Love), Mrs. Langtry. The first act of A Society Butterfly is supposed to take place in Mrs. Courtlandt Parke’s bungalow on the banks for the Thames, and is called “The Chysalis”; the second at Dudley’s House, Belgravia, is termed “Wings Expanding”; the third, in the Duchess of Newhaven’s drawing-room, bears the title “The Butterfly”; and the fourth, at Dudley’s House again, is known as “Folded Wings.” All these headings to the different acts will sufficiently indicate the progress and state of the principal lady character in the piece. Mr. William Sidney is looking after the stage management. Mr. John Phipps has been appointed secretary of the theatre, and the business-management is in the hands of Mr. Frederick Stanley. ___

The Sheffield Daily Telegraph (4 May, 1894 - p.4) MATTERS THEATRICAL. The last performances of that admirably-mounted but motiveless play, “Mrs. Lessingham,” are now announced at the Garrick. It will be substituted on the 19th by the revival of the celebrated Haymarket comedy, “Money.” In this Mrs. Bancroft will make a welcome reappearance on the stage. Her entrance now into the stalls of any theatre is most boisterously applauded by the audiences. On Monday next we shall see Mrs. Langtry at the Opera Comique in Mr. Robert Buchanan’s and Mr. Henry Murray’s new comedy, “A Society Butterfly.” Unfortunately this day clashes with the commencement of Eleanora Duse’s season at Daly’s. The great Italian actress is sure to draw a fashionable crowd. I am informed that the company she is bringing over is vastly superior to the one which accompanied her last year. A verbatim report of all plays performed will also be on sale in the theatre to assist the audience in following the dialogue. ___

Reynolds’s Newspaper (6 May, 1894 - p.6) Owing to Signora Duse’s reappearance in London having been fixed for Monday next, the production of Messrs. Robert Buchanan and Henry Murray’s comedy, “A Society Butterfly,” has been postponed until Thursday, May 10. ___

The Times (11 May, 1894 - p.5) OPERA COMIQUE THEATRE. Mrs. Langtry made one of her occasional appearances as an actress, last night, at the Opera Comique in a play entitled A Society Butterfly, which appears to have been expressly written for her by Messrs. Robert Buchanan and Henry Murray. The motive of the play is simplicity itself. A young wife, who has been reading Dumas’ “Francillon,” is advised to pay out her husband for his attentions to another woman. Accordingly, she “goes the pace” in “smart society” under the protection of a horsey duchess, who at heart is anxious for her welfare. She is to be seen everywhere, takes part in private theatricals and tableaux vivants, and has her name compromisingly coupled with that of a raffish army officer, technically known as a “wrong ‘un.” Upon the husband, who for his part has been compromising himself with an American widow, these tactics have the desired effect, and the curtain is brought down upon a scene of conjugal reconciliation. the play went to pieces in the third act, where a variety entertainment is given in the form of a scene within a scene for the purpose of enabling Mrs. Langtry to appear in a pose plastique. Ominous murmurs of dissatisfaction were heard from the popular parts of the house, and as the fourth act was necessarily of a merely explanatory character, the same discontent was manifested at the fall of the curtain. Mrs. Langtry’s somewhat intermittent attention to the stage has not tended to her improvement as an actress; but en revanche her gowns and her diamonds are magnificent. The best acting in the piece is that of Miss Rose Leclercq as the Newmarket duchess with a copious vocabulary of racing slang: but Mr. F. Kerr, Mr. Edward Rose, and Mr. William Herbert furnish agreeable though conventional “Society” types, and there is, generally, an ample and well-attired personnel operating on a well-appointed stage. __________ Mlle. Jane May, who has won some reputation in London as an exponent of wordless play, presented a new pantomime last night at the Tivoli. The title of this, Mr. Galatea, is sufficiently explanatory. A statue comes to life, falls in love with a fellow-statue, and breaks it in his embrace, and is then condemned to remount his pedestal and be changed into stone again. The little story is prettily told in dumb show. Mlle. Jane May concludes her performance by giving realistic imitations of Mme. Sarah Bernhardt. ___

The Echo (11 May, 1894 - p.2) OPERA COMIQUE. Mr. Robert Buchanan and Mr. Henry Murray are both clever men, but they cannot be congratulated on the success of their joint attempt last night to write up to Mrs. Langtry’s new frocks. They would probably have done better to have fitted their client with a more biographical narrative. A Society Butterfly, their new play, is not novel in theme. Mrs. Dudley, a young wife, is the best of her sex, and loves her husband dearly, but she finds him flirting with another woman, and is unhappy. The Duchess comes and advises her to treat her husband as he treats her; to seek her own pleasure and leave him to his own devices. She acts on this old recipe for rekindling love by awakening jealousy, and throwing over the joys of domesticity plunges into the vortex of social follies, and becomes the reigning Society beauty of the season, flirting the while with an early flame, Captain Belton. In the course of her social frivolities she appears in a set of tableaux vivants, given at the Duchess’s house. About these living pictures expectation ran high. People came with their nerves steeled against being shocked; but their heroic resolution was not put to the test. “The Judgment of Paris,” “Lady Godiva,” and As You Like It, sound risky, but in the deed they were as decorous as a provincial bazaar side-show, and not much more interesting. Mrs. Dudley having decided to leave her husband, informs Captain Belton of the fact. The Captain is embarrassed. he is very fond of the lady, and quite willing to indulge in what the French call le partage, but throwing up his pleasant life in London and his commission in the Army, and bolting to an unknown land practically without money, are quite different matters. Mildly disgusted at discovering the pusillanimous nature of the man with whom she has been so intimately associated, poor Beauty decides to make it up with her husband; and a very tame scene of mutual forgiveness brings a play which is tedious to a degree to a welcome close. Mrs. Langtry wore four distinct dresses, to say nothing of tableaux vivants costumes, and three of them were of great splendour, the last, a gown of plain satin of the faintest imaginable yellow, being of such beauty as to partly compensate for the dreariness of what had gone before. Beauty, however, cannot garb itself in splendour in a hurry, and the waits between the four frocks which constituted the better part of the entertainment were trying to the patience of the gallery boy. It is not difficult to conjecture on what well-known lady of Society the part of the stable-talking Duchess played by Miss Rose Leclercq is based; but, listening to the Turfy phrases, not always correct, which characterise every utterance from her mouth, we could not help remembering how, with half the material and ten times the success, Mr. Pinero had painted her forerunner George Tid of Dandy Dick. There is little need to enter into detailed criticism of the acting, except to say that Mr. Edward Rose was humorous as a literary and aristocratic young booby with a taste for classic play-writing. The house was packed to its extreme limits with exceedingly smart men and women, but many a stall was vacant before the end came, and the authors, who resolved to appear to a call of their names, had [...] reason to rejoice in their temerity. ___

The Daily News (11 May, 1894) THE DRAMA. A SOCIETY BUTTERFLY. The new comedy of modern life, by Mr. Robert Buchanan and Mr. Henry Murray, in which Mrs. Langtry made her appearance for the first time this season at the Opera Comique last night, might fairly have been expected to enjoy more favour than it secured at the hands of a rather turbulent section of the audience; for it presented few ideas, and even very few incidents, which have not already proved their power—some, indeed, many times over—to entertain the public. There were reminiscences of “Frou-Frou,” of “Francillon,” of “Un Mari dans du Colon,” and at least half-a-dozen other popular pieces, not to speak of a “variety entertainment” supposed to be given at the house of a sporting duchess, or of that latest of revived fashions—an exhibition of living tableaux. With all these advantages, however, “A Society Butterfly” manifestly wearied the spectators, and as the curtain fell some rather determined expressions of dissatisfaction, mingling with less determined applause, gave rise to a somewhat unusual scene. There were, as is usual on such occasions, calls for the authors, which were obviously not of an entirely friendly kind. Nevertheless, Mr. Buchanan and his coadjutor made their appearance before the curtain, and the former, irritated apparently by the yells and booings which their presence provoked, deliberately put on his spectacles to survey the disturbers. Then, placing his fingers to his lips, and looking upward in the direction of the gallery, Mr. Buchanan went through the gesture which is known as “wafting a kiss,” whereupon he and his companion retired. The story of the new play, though it is extended over four acts, occupying three hours, sets forth nothing less simple than a matrimonial tiff, which ends in a renewal of love. Mrs. Dudley, a vicar’s decorous and pretty daughter, has discovered that her husband flirts with Mrs. Courtlandt Parke, a fascinating American widow, who has a villa on the banks of the Thames, and she has overheard him complain of her humdrum ways. Therefore Mrs. Dudley claims an equal right to go what is known as “the pace,” and forthwith the quiet lady of the first act blossoms into the society beauty, wears magnificent dresses, decorates herself with costly jewels, frequents the houses of noble dames of gay and easy manners, and flirts so desperately with a military officer that her husband’s worst suspicions are aroused. The scheme of the play, however, is too simple and obvious for the elaborate treatment. Mrs. Langtry’s dresses and diamonds were greatly admired, but her long speech on the thesis of equal liberty for the two sexes awakened little interest, and the pathos of her wounded pride and unrequited affection failed to touch a chord in the heart of the spectator. Mr. William Herbert was even less successful as the husband, though it must be confessed that it is not easy to see how more could be done with the part of this weak and hesitating person, whose frequent commands and warnings to his wilful wife are so ludicrously ineffective. Miss Leclercq, on the other hand, in the character of the Duchess, whose sporting metaphors are as profuse as Commodore Trunnion’s sea phrases, aroused hearty laughter. The new piece is brilliantly mounted, and the company, which includes Mr. F. Kerr, Mr. Allan Beaumont, Mr. Edward Rose, and other capable performers, is worthy of better employment for its talents than it found last night. ___

The Standard (11 May, 1894 - p.3) OPERA COMIQUE THEATRE. A Society Butterfly, by Messrs. Robert Buchanan and Henry Murray, announced as “a new and original comedy of modern life,” proves on inspection to be an old and sadly-worn comedy dealing essentially with the life of the stage, crudely constructed, feebly written, and ill-acted. The story is neither true to life nor effective for the boards. A sort of far-away attempt is made to argue the ethical contention that man and woman are subject to equal laws, that what is wrong in the one is wrong in the other; but, as no one has ever seriously denied this—off the stage—no good purposes is served by the argument, particularly as it is set forth in such very unconvincing fashion. The “society butterfly” is Mrs. Dudley. She had been the most devoted of wives until she found that her husband was bored with the oppressive atmosphere of domesticity with which she pervaded him, and that he was seeking relief and contrast by making violent love to Mrs. Courtlandt Parke, a rather vulgar woman, who lives on the banks of the Thames, and fitfully cultivates an American accent. The hitherto model Mrs. Dudley calls on this lady to expostulate, but she meets at the house an absolutely impossible Duchess, who advises her to retaliate on her husband by setting up love affairs of her own. All this, of course, is as old as fiction; and though age is no detriment to a powerful story, if treated with strength and some approach to originality of detail—for human nature remains what it always was, and certain complications which continually recur must always have their point and significance—A Society Butterfly is very far indeed from fulfilling any of the requirements of a modern drama. The most novel scenes in it, indeed, are those which are borrowed from Frou Frou. Incidentally, it may be remarked that the sporting metaphors and similes with which the Duchess of Newhaven so copiously interlards her conversation are such as could never, by any possibility, have been used by a woman who had—as the Duchess is understood to have—some acquaintance with racing affairs. Her expressions are, apparently, borrowed from the works of female novelists who have no knowledge of the subject they discuss; and it is not a little sad to find so capable an actress as Miss Rose Leclercq doomed to fill such a part as that here provided for her. If Dudley cared for his wife, he would not have paid such exceedingly compromising visits to Mrs. Courtlandt Parke; but, in truth, the theme as presented is so little worth argument that controversial comment would be unprofitable. To describe the attitude of an audience is not to criticise a play; but there are plays which do not call for criticism, which are merely direct appeals to audiences for thoughtless applause, and with regard to which, therefore, the reception is everything; and it must consequently be observed that as A Society Butterfly was evolved a tendency to derision was manifested. The earnestness and manly bearing of Mr. William Herbert as Dudley failed to make the character convincing. Mr. Kerr gave a very shadowy performance of a Captain in the Guards who endeavours to beguile Mrs. Dudley from the path of duty. Mrs. Langtry was the heroine. ___

Glasgow Herald (11 May, 1894) A CLUMSILY driven van yesterday very nearly caused a postponement of Mr Robt. Buchanan’s new play this evening. Mrs Langtry was being driven down St Martin’s Lane to the final rehearsal when the van “poled” her carriage. Mrs Langtry was thrown forward, and thus just escaped being struck by the pole. The actress was a little frightened, but otherwise escaped unhurt. The audience attracted this evening to the first performance of Messrs Buchanan and Murray’s long-expected new play, “The Society Butterfly,” must have been an agreeable experience to the Opera- Comique, and it, indeed, almost recalled a Lyceum first night. Society, in fact, was very strongly represented, as well as ordinary first-night goers, for Mrs. Langtry was now to play the chief part in a new society piece, so that the stalls were quite insufficient for the demand for places, and some of the best people were to be found in the dress circle. The story of “A Society Butterfly” is very English, and practically all the characters, some exaggeration apart, might almost have been drawn from the thoughtless “society” men and women of the period. Charles Dudley, the husband of the piece, is a very thoughtless personage, and his flirtations with Mrs Courtlandt Parke have became so very pronounced that the Duchess of Newhaven advised his wife to give him a Roland for an Oliver. She does so with a vengeance, and becomes a society butterfly. She flirts so outrageously with all the men that her husband resolves on a separation. This sort of thing will, however, by no means suit Mrs Dudley, and rather than be left in London she entreats a young exquisite, Captain Belton, to elope with her. This cool suggestion is refused, for the Captain is threatened by his aunt with a stoppage of the money for his tailor’s bills if there is any esclandre, so that eventually the good-natured duchess is enabled to bring about a reconciliation between husband and wife. One of the principal scenes of the piece is an evening party in the duchess’s drawing-room, where Mrs. Langtry first acts the part of Aphrodite in some private theatricals, and afterwards takes part in some society tableaux vivants, the stage being darkened, and Mrs. Langtry appearing as Lady Godiva, recalling the well-known picture. This scene was, however, not very well received by the audience. The play, nevertheless, was on the whole well acted, and it was magnificently mounted. Indeed the ladies’ costumes are likely to become a genuine nine days’ wonder. ___

St. James’s Gazette (11 May, 1894 - p.12) THE THEATRES. “A SOCIETY BUTTERFLY” AT THE OPERA COMIQUE. MR. ROBERT BUCHANAN and Mr. Henry Murray are gentlemen deserving of the deepest sympathy. They have been inspired by a great idea—a noble purpose; but, like so many pioneers in the field of thought, they find the world, or so much of it as could be conveniently lodged in the Opéra Comique Theatre last night, not yet ripe to appreciate their efforts. Shrewd observers of their own time, they have watched the music-halls gradually, but surely, invade the domain of the theatre, and suddenly it has occurred to them, Why not endeavour to turn the tables? Why not write a play—a serious play—which shall be as instructive as “The Second Mrs. Tanqueray” and yet contain all the attractions of an entertainment at the Empire or the Palace? If the public is prepared to accept forty-minute sketches and compressed melodramas at the “Halls,” would it not with equal readiness welcome “living pictures” and imitations of popular actors in a piece of serious interest at the theatre? ___

The Daily Telegraph (11 May, 1894 - p.6) An English audience borrowed last night from America what is in certain given circumstances a very courteous and desirable custom. The play presented to their notice was called “A Society Butterfly,” and it was announced as written by Mr. Henry Murray, but chiefly by Mr. Robert Buchanan, a man of letters, who has in his time given the stage some excellent literary and dramatic work. The company contained the names of Mrs. Langtry and of many artists who are deservedly held in respect. But the play proved to be wholly without interest, and the players could not, with all their superhuman efforts, lift it from the dangerous edge of a precipice called ridicule. So this very courteous and considerate audience did not hiss the play or linger too long on its unfortunate social solecisms, or treat with scorn incidents and interludes that failed purely from want of judgment and experienced knowledge of the stage. Not desiring to be harsh to Mr. Robert Buchanan or rude to Mrs. Langtry and her brothers and sisters in affliction, the wearied playgoers simply went out. They folded their seats in depression and silently stole away. There was no fuss, no fury, no gibes, no catcalls; the audience merely melted and disappeared. And it is to be gravely feared that, in spite of the dresses—so well advertised—and the music-hall programme—so badly imitated—that the play—the poor play—will follow the lead of the audience. It will not fizzle or splutter, or grow hot or cold, or die down in a fiery glow, or create discord or discussion. Its destiny is sealed. It will simply go out. ___

The Sheffield Evening Telegraph and Star (11 May, 1894 - p.3) WHAT’S IN A NAME? Messrs. Robert Buchanan and Henry Murray cannot be congratulated upon their comedy of modern life, “A Social Butterfly,” which was produced last night at the Opera Comique with Mrs. Langtry in the principal part. The work is dull and amateurish. The main object seemed to have been to introduce some “tableaux vivants” for Mrs. Langtry to appear in. The lady undoubtedly looks very handsome in pale pink classic robes as Aphrodite, but this does not suffice for an evening’s entertainment, and the play itself is wearying. It was well played, Mrs. Langtry showing some power as the lady who becomes a society butterfly in order to punish her husband for his partiality for another woman. ___

The Edinburgh Evening News (11 May, 1894 - p.4) MRS LANGTRY IN “THE SOCIETY BUTTERFLY.”—There was a large attendance of society people at the Opera Comique, London, last evening, to witness the rentree of Mrs Langtry into theatrical life under the management of Mr Robert Buchanan. There was a new play for the occasion, “The Society Butterfly,” written by Messrs Buchanan and Murray. In a scene representing private theatricals, Mrs Langtry posed as Aphrodite and Lady Godiva. Previous to the performance, while Mrs Langtry’s carriage was going to the theatre, a van collided with the carriage, one of the van shafts going through it. Mrs Langtry, however, escaped injury. ___

The New York Times (11 May, 1894) Mrs. Langtry Has Aged. LONDON, May 10.—Mrs. Langtry reappeared on the stage this evening in Buchanan and Murray’s “A Society Butterfly,” at the Opera Comique. She had the leading part, and did satisfactory work, although the organized gallery claque treated her badly. She has aged rapidly since her last public appearance. She was fairly supported. ___

The Era (12 May, 1894) THE OPERA COMIQUE. Mr Charles Dudley ... ... Mr WILLIAM HERBERT CHARACTERS IN THE INTERMEZZO. Hera ... ... Miss WALSINGHAM “When the husband steadily goes wrong, what line shall the wife take?” Allow him to very nearly be assassinated, and then relent and save his life: that will cure him, says M. Dumas the Younger, in La Princesse Georges. Institute a domestic divorce de thoro—and keep it up, says M. Emile Augier, in Le Gendre de M. Poirier. The authors of A Society Butterfly, prescribe a rush into the giddy whirl of modern society. Stay out late at night, be interviewed in the ladies’ papers, and put your spouse in the position of “Mrs Somebody’s husband.” By taking a lover and putting him severely to the test you—the wife—will soon discover that, if one man is faithless, all are ignoble; and, as a pis aller, you will return to your lawful spouse. He, by that time, will have got tired of his Siren, and will long for his night’s rest; and your social success will also have titillated his vanity of proprietorship. Having each of you had your lesson, you will settle down cheerfully to a Darby and Joan existence. ___

The Era (12 May, 1894) THEATRICAL GOSSIP. . . . THERE were many rumours to the effect that Mrs Langtry was to typify in a series of tableaux the career of a butterfly—the cocoon, the chrysalis, and the radiant insect full blown—as the climax of the third act of Messrs Buchanan and Murray’s play; and it would, we understand, be unfair to put these rumours to the credit of the inventive scribes of the daily press. Almost at the last moment, it is said, the dramatists came to the conclusion that a more dramatic effect could be obtained by “living pictures” of the story of Godiva, and on the instant dispatches were sent to Paris for what one cannot strictly call the “necessary” costumes. But why was Mrs Langtry, after all, wrapped up in a blue blanket? ___

Birmingham Daily Post (12 May, 1894) LONDON CORRESPONDENCE. LONDON, Friday Night. . . . The new venture at the Opera Comique, in which Mrs. Langtry appeared for the first time last night as the heroine of “A Society Butterfly,” a comedy by Mr. Buchanan and Mr. Henry Murray, does not promise prolonged success. The piece is reminiscent of various others with which the playgoer is familiar, “Frou Frou,” “Dandy Dick,” and even “After Dark” being suggested, while pointed mention is made in it of Dumas’s “Françillon” as in some degree furnishing a motive for the action of certain of the characters. The story is that of a young and beautiful wife who, feeling wronged by her husband, acts upon the principle that two blacks may assist to make a white, and goes as near to wrongdoing—in the endeavour to make her husband jealous and thus win back his love!—as it is discreetly possible to do, and in this curious and dangerous attempt she succeeds. The audience did not appear to consider the plot either probable or well worked out, though it showed much appreciation of the dialogue; but its patience was especially taxed by some singularly ineffective tableaux vivants which had been much talked of in advance, but which led to nothing. The best piece of acting was that of Miss Rose Leclercq as an impossible duchess, whose sporting slang would have been insufferably tedious if it had not been so artistically presented; while Mr. F. Kerr as a Guardsman of dishonourable tendencies played with his accustomed ease and effect. ___

The Daily News (12 May, 1894) “A SOCIETY BUTTERFLY.” MR. ROBERT BUCHANAN’S PROTEST. The Press Association says: After the performance of Mr. Robert Buchanan and Mr. Henry Murray’s new play at the Opera Comique last night, the manager asked the audience not to leave their seats, as Mr. Buchanan wished to say a few words. Mr. Buchanan then came on the stage, and advancing to the footlights, said: ___

The Yorkshire Evening Post (12 May, 1894 - p.3) “Trid on the tail av me coat,” said Mr. Robert Buchanan, scornfully, as he trailed his critical garment in the Opera Comique last night. There was an intellectual Donnybrook in progress. Mr. Clement Scott had condemned A Society Butterfly, which is from the gifted pen of Mr. Buchanan; and that gentleman took to the stage to make his tu quoque more effective. And sich langwidge! “The writer of foolish verses for the music-halls, and of crude adaptations which he offers to leading actresses”—this is the unkind way in which Mr. Buchanan described the great Scott—“has again and again gone out of his way to abuse my work. I wish from this stage to state publicly that he is an egotistical and spiteful writer.” When two men quarrel about their bread-and-butter in this style, the libel laws afford a very unsatisfactory remedy for both. _____ . . . Mr. Robert Buchanan is such a clever fellow that one always feels angry at him for just missing success. The other day he had three plays running at the same time; where are does barties now? And his new play, A Society Butterfly, seems foredoomed to failure. Not even the fact that Mrs. Langtry wears the novelist dresses—one “a gown of plain satin of the faintest imaginable yellow”—can pull it through. The Jersey Lily also appeared in tableaux vivants as Lady Godiva and as Helen in The Judgment of Paris, which sounds risky. But, as one disappointed critic remarks, “in the deed they were as decorous as a provincial bazaar side-show.” ___

Reynolds’s Newspaper (13 May, 1894) DRAMA, MUSIC, AND ART. “A SOCIETY BUTTERFLY” AT THE Messrs. Buchanan and Murray’s new play deserved a better reception than it received at the Opera Comique on Thursday night. It was well staged, well acted, and most of the dialogue was crisp and up-to-date. Some modern doctrines as to women’s position were incidentally inculcated, but the finale was vice reproved and domestic happiness triumphant. Accordingly, the moral English audience should have been satisfied. Yet the disapproval given expression to by some was not altogether unjustifiable. Acts I. and II. were of the right length and to the point. Act III., while it contained the finest situation and best writing of the whole play, was entirely too long, and filled up with a lot of irrelevant matter. The second part of the amateur theatricals should be cut out altogether. When this is done, together with some other judicious pruning and polishing, the play will be tolerably good. Idalian Aphrodite beautiful while Captain Belton takes the role of Paris. Dudley, who deeply loves his wife, and who is driven to desperation by what he conceives to be her folly and heartlessness, is on the point of separating from her for ever, when a reconciliation is brought about by the Duchess and Dr. Coppée, an old friend of the Dudleys. ___

The Referee (13 May, 1894 - p.3) Application and hard work are necessary to success on the stage as in any other profession, and it is therefore not surprising that Mrs. Langtry, on taking up acting again after a long time, should not have improved with want of practice. Not only has she not advanced, she has gone back; and her flaccid performance of Mrs. Dudley in “A Society Butterfly,” the new play by Messrs. Robert Buchanan and Henry Murray, produced on Thursday night at the Opéra Comique, relegated her to the ranks of the amateur who has pretty well everything to learn. The excellence of her intentions may be allowed, but the power of expression was utterly incommensurate. There was little feeling in her voice, her gestures were ineffective, and she failed to command, not only the admiration, but even the respect of the audience, who treated her with slight civility. It is as well to speak plainly, for although Mrs. Langtry appears at the head of the company, it is pretty clear that she does not hold that position by right of talent, which is the only right the public acknowledges. To be sure, the piece is not one that demands overmuch of an actress. It would almost seem that the authors had taxed their ingenuity expressly to provide Mrs. Langtry with a showy part. The difficulties with which the “butterfly” is confronted resolve themselves actually into nothing more than a domestic difference of no desperate gravity. Mrs. Dudley, to revenge herself upon the husband who has slighted her, plunges into what lady novelists call the vortex of Society. Whilst her husband is paying court to an American widow, who Is not so wicked as she seems, Mrs. Dudley encourages the addresses of a young gentleman—played by Mr. F. Kerr in his only way—who does not seem so wicked as he is. But it is a great case of much ado about nothing, for nobody is very seriously compromised in the end, when the husband and wife are reconciled. Miss Rose Leclercq acts with dash as a sporting duchess, speaking only in the language of the turf, whose house is the scene of the tableaux vivants which excite great expectations that are not realised. We hear of a costume for the “butterfly” that has been brought home “in a glove-box,” but there is (only idiomatically speaking) nothing in it. The tableaux vivants, indeed, might be cut out altogether without impairing “A Society Butterfly’s” chance of success. At the end of the performance the authors were called before the curtain, and Mr. Robert Buchanan, not to be exceeded by the gallery in the expression of derision, retorted with the action that is known as blowing a kiss. Or perhaps it was only his way of returning good for evil. On Friday Mr. Buchanan was not in nearly so playful a humour. Before the curtain rose on the last act the manager came forward and stated that Mr. Buchanan wished to address the audience, which he did in due course, and in extremely injudicious terms, holding in his hands a copy the Daily Telegraph, whose criticism he resented. There was no extra charge for this part of the entertainment. Something, though, may come of it. I hope it may not be human gore. There is one man, at any rate, who agrees with the furious Mr. Buchanan, and that is Mr. Henry Murray, joint author of the play, who contented himself with saying “ditto” to Mr. B. There was to-night at the Adelphi some indication as to which side the public—the public who are theatre-goers—will take in the curious bit of warfare that has sprung up between the author of “A Society Butterfly” and the dramatic critic of the Daily Telegraph. Directly Mr. Clement Scott was espied entering a private box cheering arose in all parts of the house. There was no getting away from the demonstration, and Mr. Scott, at the front of the box, with smiles and repeated bows acknowledged it. ___

The People (13 May, 1894 - p.6) OPERA COMIQUE Judged by the forbidding reception accorded on Thursday night on the re-opening of the Opera Comique to the so-called comedy of modern life, “A Society Butterfly,” the life of the piece is likely to prove as ephemeral as its title suggests; nor can it be said that the audience were less than justified in their condemnation by the poor quality of the play itself. Its authors, Messrs. R. Buchanan and H. Murray, having borrowed from a succession of dramatic sources, ranging from the ancient comedy of “The Way to Keep Him,” to the modern drama of “Francillon,” the stratagem of a neglected wife winning back an errant husband’s love by arousing his jealousy against a presumed rival, through affecting to play against him his own game of marital infidelity, proceed to supplement this too familiar device by linking it with the latest “turns” of a music hall entertainment presenting tableaux vivants, followed, without rhyme or reason, by imitations of popular actors having not the slightest reference to the play or even to each other. Nor was the weakness of their commonplace play masked or in any way compensated for by any strength on the part of Mrs. Langtry, who, after a long withdrawal from the stage, revisited the glimpses of the footlights to play the wife, her impersonation being so amateurish, through lack of both artistic accomplishment and emotional expression, as to give an impression of insincerity. This evidence of unreality became the more apparent by contrast with the finished comedy displayed by that perfect histrion, Miss Rose Leclercq, in delineating the peculiarities of a highly sporting duchess, whose conversation is interlarded to excess with the slang of the hunting field and racing stable. Nothing but the naturally refined humour of the actress could have served so to mask the extravagant vulgarity of this character as to render it tolerable, as the audience acknowledged by applauding the player while decrying the play. Mr. William Herbert acted the peccant husband with discretion; and Mr. Allan Beaumont brought his sound histrionic style to bear with justly telling effect in the part of a shrewd French medico. As the would-be tempter of the wife, Mr. F. Kerr gave such a truthful portrayal as he has used playgoers to expect from him of an easy aristocratic libertine, the repulsiveness of whose utter selfishness is half masked by unconscious humour. Other parts, in a very full cast too numerous to mention, were sufficiently well played, but it is to be feared to no purpose in saving the play itself from its initial failure taken purely upon its merits—or want of them. It was, no doubt, cruel to summon the authors before the curtain only to deride them; but latter day audiences who have paid their money are rather given to bait dramatists who fail to give them a pennyworth for their penny. ___

The Scotsman (14 May, 1894 - p.7) “A SOCIETY BUTTERFLY.”—After the performance of Mr Robert Buchanan and Mr Henry Murray’s new play at the Opera Comique on Friday night, the manager asked the audience not to leave their seats, as Mr Buchanan wished to say a few words. Mr BUCHANAN then came on the stage, and advancing to the footlights, made a speech violently attacking Mr Clement Scott for a criticism of “A Society Butterfly,” adding—“A cabal was there to insult and terrify a helpless woman. Throughout the play an attempt was made to twist every inherent reference into a personal imputation, and when the third act terminated weakly and feebly through a mishap, the cabal howled and hooted at the leading actress, who was in no way responsible for what had occurred.” After some further remarks, Mr Buchanan said, “You have now seen the play for yourselves, and we leave it for your good or your bad opinion.” Mr Buchanan quitted the stage amidst loud and sustained cheers. Mr HENRY MURRAY remained behind, and said—”Ladies and gentlemen, I have no word to say except that I cordially endorse every word Mr Buchanan has spoken.” Following on Mr Murray’s withdrawal from the stage there were loud calls for Mrs Langtry, who was received with much enthusiasm. Mr Clement Scott on Saturday, in an interview with a representative of the Westminster Gazette on the subject, said:—“Mr Buchanan has done it before, and I have no doubt he will do it again; but we have managed to remain good friends in spite of it all, and I daresay we shall continue to remain so. It pleases him and doesn’t hurt me. No, I don’t suppose I shall take any further notice of it unless my solicitors advise me otherwise, which is not very likely. Of course,” continued Mr Scott with a smile, “what Mr Buchanan says is preposterously untrue, but that is really one reason why it is not necessary to take serious notice of it. Talk of that sort carries with it its own refutation.” ___

Freeman’s Journal and Daily Commercial Advertiser (Dublin) (14 May, 1894) Mr. Clement Scott has adopted a suaviter in modo attitude with reference to Mr. Buchanan’s attack on him from the stage of the Opera Comique on Friday night. Mr. Buchanan, in collaboration with Mr. Henry Murray, wrote “A Society Butterfly,” which Mrs. Langtry produced on Thursday last. The piece was far from being the best written by Mr. Buchanan, and was for personal and other reasons especially unsuitable for Mrs. Langtry. In common with other critics, Mr. Scott criticised it adversely, but evidently in a manner which the authors considered biassed and unfair. Accordingly, after the curtain fell at the Opera Comique on Friday night Mr. Buchanan came to the footlights, and, referring to Mr. Scott’s criticism, charged him with personal malice, and characterised him as “an egotistical and spiteful writer.” Interviewed on the incident subsequently, Mr. Scott did not appear much perturbed at the onslaught levelled at him. It pleased Mr. Buchanan, he said, and did not hurt him, and accordingly he probably would not take any further notice of it. He, however, controverted all Mr. Buchanan’s references and innuendoes, though he persisted in describing the play as an utterly unworthy production. At the conclusion of the interview he characteristically remarked, “Don’t be hard on him. Whatever you make me say, put it as nicely as you can.” Mr. Scott’s criticism may or may not have exceeded legitimate bounds, but even if it had, Mr. Buchanan might have selected another arena for his attack, and might also have restricted it to more moderate terms. The public would appear to favour Mr. Scott’s action, as on appearing at the Adelphi Theatre on Saturday he was loudly cheered from all parts of the house. Nevertheless, it is well known that before Mr. Buchanan reached his present position as a dramatist, he was the object of bitter and even occasionally malignant attacks from a certain coterie mainly composed of dramatic critics. ___

Pall Mall Gazette (14 May, 1894 - p.2) A really pretty quarrel is one of those things which the world will not willingly let die; and the quarrel between Messrs. Robert Buchanan and Henry Murray of the one part and Mr. Clement Scott of the other has added immeasurably to the gaiety of nations; for it is an exceedingly pretty one, a most delightful illustration of the amenities of theatrical intercourse. Mr. Murray and Mr. Buchanan have each sent us a strongly-worded letter, which it would have been our joy to print in the interest of free controversy. But Mr. Scott has informed a contemporary that he will probably bring an action for criminal libel against one or both of his adversaries, in addition to civil actions against other parties; and we break no confidence in saying that Mr. Buchanan has expressed his eagerness to meet him before a judge. Therefore it would be unbecoming if we were to interfere in the matter: which must be left in the hope that each side may find plenty of power to its elbow. ___

The Derby Daily Telegraph (14 May, 1894 - p.2) The theatrical sensation of the week—Mr. Robert Buchanan’s denunciation of Mr. Clement Scott from the stage of the Opéra Comique on Friday night—received a new fillip at the production of “The Two Orphans” at the Adelphi on Saturday night. The critic of the Daily Telegraph suggested to an interviewer on Saturday that his life would be none the happier if he could not sit in his stall without pit and gallery splitting up into opposite camps for and against him, and hailing him with cheers and hisses. On Saturday night he sought the seclusion of a box at the Adelphi. One of the audience, however, caught sight of his easily recognisable face. There was a shout of “Scott,” which was taken up rapturously all over the house, and the critic was forced to bow his acknowledgements. That, I suppose, will be Mr. Scott’s answer to Dramatist Buchanan. ___

The Nottingham Evening Post (14 May, 1894 - p.2) MR. SCOTT AND MR. BUCHANAN. The appearance of Mr. Clement Scott in a private box at the Adelphi just before the rising of the curtain upon “The Two Orphans” on Saturday evening was the signal for a prolonged and friendly demonstration from various parts of the crowded house, which apparently had reference to the speech of Mr. Robert Buchanan at the Opera Comique, published, with the suppression, however, of some angry passages, in the papers of that day. This does not look as if Mr. Scott’s reputation had suffered much injury from Mr. Buchanan’s excited and intemperate language—which indeed was rather of the nature of that mere “abuse” which our courts of law are wont to distinguish from actionable or indictable slander. ___

The Sheffield Evening Telegraph and Star (14 May, 1894 - p.2) PLAYWRIGHT AND CRITIC. A NEW phase of the relations of playwright and critic was displayed on Friday evening at the Opera Comique. Mr. Robert Buchanan, one of the best known authors and playwrights of the day, in conjunction with a lesser light of the literary firmament, wrote a play entitled “The Society Butterfly,” in which Mrs. Langtry made her re-appearance after a lengthy absence from the stage. From the criticisms which appeared in the Press on the production of the play it did not appear that “A Society Butterfly” had any strong recommendations to public favour, nor that it was received with more than bare indulgence by the first night audience. The notices were not such as to persuade the public at large to flock to the theatre, and those persons who seek such advice in the matter of their amusements would probably be incited to stay away. Such notices are apt to be the lot of every theatrical manager and of every author. In the theatrical world the best laid plans oft gang agley. To deserve success is by no means to ensure it. Pieces on which thousands of pounds have been lavished have been played to empty houses for a fortnight, and then disappeared into that oblivion which overtakes the unfortunate. Plays into which authors have striven to put their best, and which have represented months of anxious and diligent labour, have been condemned by unsympathetic audiences and stern critics. It is the fortune of war. Mr. Buchanan, who ought by now to be perfectly pachydermatous, for no man living has had more bricks thrown at him, resents one of the critiques on “The Society Butterfly”—the critique written by a man as well known as himself—Mr. Clement Scott. Mr. Buchanan took the unusual step of coming before the curtain on Friday night to draw the attention of the audience to this notice and to denounce it in no measured terms. It was, Mr. Buchanan insinuated, unfair and malignant; he accused Mr. Scott, to whom he sarcastically alluded as “the writer of crude verses for the music halls,” of having again and again gone out of his way to abuse his work; and he finished up his speech with the announcement of his desire to publicly express his opinion that Mr. Scott is “an egotistical and spiteful writer.” There can be no question that Mr. Buchanan had lost his temper, and with his temper his discretion. Mr. Clement Scott is probably the most able theatrical critic of the day, and it is absurd to suppose that he would imperil his character for impartiality by prejudiced and groundless attacks on any playwright. Mr. Buchanan’s procedure is better than the personal violence to which playwrights and actors who have fancied themselves aggrieved have been known to resort, but it cannot be characterised as wise. Mr. Clement Scott can afford to disregard the attack made on his integrity; and Mr. Buchanan has merely made a public display of a little temper. _____ (p.3) LONDON LETTER. . . . THE HISSING OF MRS. LANGTRY. Mr. Robert Buchanan, in his eagerness to single out Mr. Clement Scott from the army of dramatic critics who have spoken slightingly of “A Society Butterfly,” has begun badly, for he has so shaped his challenge to mortal combat as not only to make people smile when he expected them to be awed and serious, but he has turned the laugh against himself. For, in order to refute Mr. Clement Scott’s kindly attempt to draw a veil over the hostile reception accorded to the play on the first night, Mr. Buchanan sets himself to prove that, instead of quietly withdrawing from a performance that bored them, the audience remained to make “the most unseemly demonstration that ever took place even in a theatre.” He is amusingly furious at Mr. Scott for saying “there was no fuss, no fury, no gibes, no cat-calls.” He insists that, on the contrary, the leading actress was “howled and hooted.” Of course, Mr. Buchanan attributes this, not to the whole house but to “a cabal,” not to any shortcomings on the part of actress or authors, but to spite. The performance has given such universal dissatisfaction as to make Mr. Buchanan’s indignation a striking illustration of the unwisdom of displaying “perfect indifference to criticism” by running amuck at the critics. In such cases it is the head of the Malay that suffers most. DRAMATIC CRITICISM IN LONDON. A well-known writer says:—Mr. Buchanan’s action has been greatly wanting in dignity. At the same time dramatic criticism in London has got into a very unhealthy condition. For some time it has been undermined by theorists and what, I presume, amy be called schools of dramatic thought; and Mr. William Archer’s appeal to the critics this month to show a little more mercy to dramas of fair average merit, lest they should unwittingly kill some plays of real power, is not without justification. MR. SCOTT CHEERED. Another correspondent writes:—The astounding attack made before the curtain at the Opera Comique on Friday night, after the second performance of “A Society Butterfly,”| by Mr. Buchanan upon Mr. Clement Scott, the leading dramatic critic of the “Daily Telegraph,” has aroused much feeling among play-lovers here. Mr. Scott, genially enough, is prepared to laugh at the ebullition of temper; but those theatregoers who appreciate his worth are evidently unwilling to take matters so quietly, and, upon his entering a box at the Adelphi on Saturday night, cheering was to be heard from all parts of the house. The public, in fact, recognise that honest and effective dramatic criticism would become impossible if every author of an unsuccessful play were to attack the critic by name, and load him with opprobrious and insulting expressions at a time and in a place which prevented reply. ___

The Dundee Courier (14 May, 1894 - p.5) OUR LONDON LETTER. A DRAMATIC QUARREL. 57 FLEET STREET, E.C., The quarrel between Mr Robert Buchanan and Mr Clement Scott over the criticism by the latter of the former’s drama, “A Society Butterfly,” is to be referred for adjustment to a council of friends. Dramatic quarrels are becoming, in fact have become, a little tiresome. Sometimes the disturbance rages among the critics themselves, but there is always a storm of some kind, either active or brewing. The public usually judge of the play for themselves, and generally judge rightly, but nevertheless, and notwithstanding the vote of “no confidence” implied in this rebuke of the critics, the latter in some notable individual instances bear themselves with the demeanour of Cabinet Ministers. In fact, we may be said to have a Cabinet and an Opposition in dramatic criticism and dramatic construction. The world could get on very well without this Parliament of mutual vilipendists. ___

The Western Morning News (14 May, 1894 - p.5) I strongly commend to theatrical managers anxious to secure a second night audience the example set to them by Mr. Robert Buchanan. A criticism from the stage of the notices which appeared in the morning papers of the first performance of the previous night would be a notable departure in theatrical enterprise, and should not fail to ensure the attendance of many persons to whom this novelty and not the play would be the principal attraction. Of course Mr. Buchanan began his harangue on Friday night with the inevitable remark that he and his co-author are “perfectly indifferent to criticism,” that is to say, “when criticism is fair.” The great question is who is to be the judge of its “fairness.” Mr. Buchanan seems to think that the author himself is the best authority on this point, and so perhaps do many of his colleagues, but it will be difficult to convert the public to the same opinion. Anyway, playwrights can scarcely expect us to believe in their indifference to criticism when they avail themselves of the opportunity to rail over the footlights as Mr. Buchanan did on Friday. ___

The Bristol Mercury (15 May, 1894 - p.3) A SOCIETY BUTTERFLY. The new play written by Mr Robert Buchanan and Mr Henry Murray for Mrs Langtry was produced on Thursday at the Opera Comique, and on the following evening Mr Buchanan came in front of the curtain and made a savage onslaught on Mr Clement Scott because of a notice which had appeared in the “Daily Telegraph.” If the distinguished critic were as tyrannical and unjust as those who disagree with his judgments upon their efforts think, they could not devise a better method of adding to his power than this sort of demonstration. It so happens that a member of the BRISTOL MERCURY staff, ever on the lookout for a new experience, joined the crowd at the doors of the Opera Comique and found a place in the front row of the pit circle, next to a box in which Mrs Bernard Beere was seated. The following is his description of the performance:—The curtain rose on a very pretty scene, the gardens of Mrs Courtlandt Parke’s bungalow on the banks of the Thames. This lady (Miss E. R. Sheridan) is a somewhat dubious American widow and is carrying on a flirtation with Charles Dudley (Mr W. Herbert), a stockbroker, whom she knows to be married. Mrs Dudley (Mrs Langtry) has discovered her husband’s defection, and overhears him telling his new flame that he is weary of the unalloyed domesticity of his married life. In the second act we find her in her own drawing-room, a full- fledged society beauty, with her photograph everywhere, and about to play Aphrodite, in a costume which it is said has come home in a glove box, for a play on the Judgment of Paris. Her husband is furious with jealousy, although she quotes “Francillon” freely enough for him to see her motive. The third act passes in the Duchess of Newhaven’s drawing-room, where a stage has been set, and where the classic drama before mentioned is performed. This is followed by a music hall entertainment, at which little tables are placed between the seats and the guests pay for their own refreshments, while two gorgeous flunkeys put up the numbers each side of the proscenium as in a real hall. The Adelphi guests, after some crude satire upon Ibsenism, discuss some surprise that Mrs Dudley has in store, and at last the curtain is drawn up, revealing Mrs Langtry as Godiva on her way to take her famous ride through Coventry, and just carrying in front of her a blue saddle cloth, apparently for her horse. This was vigorously hissed by the audience, and in my judgment very properly so. The last act is again in Mrs Dudley’s house, the evening after this party. She has not returned, and he puts the worst construction on the fact, although she has only remained with the Duchess. He announces his intention of leaving her and going abroad, whereupon she says she will quit the house when he does and will accept no allowance, her contention being throughout the piece that the woman is entitled to the same liberty as the man. She appeals to Captain Belton (Mr F. Kerr), an odd creature who would attract no woman’s heart, to prove his protestations of love and fly with her to the isles of the Pacific. He, of course, is afraid of what people would say, and will have nothing to do with it. We have seen from the first act that husband and wife would kiss and make it up, but it is surely conventional and antiquated, as well as unjust, for the wife to be made to ask forgiveness. ___

The Western Times (15 May, 1894 - p.8) LONDON CORRESPONDENCE. LONDON, Monday Night. . . . Another illustration of the present day mania for rushing into the Law Courts with screams that legitimate criticism is libel, is to be found in Mr. Clement Scott’s intimation that he is seriously considering the desirability of bringing an action against Mr. Robert Buchanan for his retort on the critic of “A Society Butterfly.” ___

Western Mail (15 May, 1894 - p.4) LONDON LETTER. LONDON, MONDAY. . . . AUTHOR AND CRITIC. Mr. Robert Buchanan and Mr. Clement Scott are at daggers drawn. The people’s critic thought himself justified last week in throwing cold water on Mrs. Langtry and “The Society Butterfly,” whereupon Mr. Buchanan, part-author of the drama, read from the stage the next night a manifesto, in which he accused the critic of being a spiteful writer, who had distorted facts, and also who had made an attack upon a defenceless woman. Indiscreet, undoubtedly, this action was. Mr. Scott now seeks legal redress, and unless a settlement is arrived at we shall have an interesting case heard in the law courts. The principal sentence in the critique to which Mr. Buchanan takes exception states that “a very courteous and considerate audience did not hiss the play or linger too long on its unfortunate social solecisms, or treat with scorn incidents and interludes that failed purely from want of judgment and experienced knowledge of the stage. . . . . Wearied playgoers simply went out. They folded their seats in depression and silently stole away. There was no fuss, no fury, no gibes, no cat-calls; the audience merely melted and disappeared.” This statement Mr. Buchanan meets with a flat contradiction, and in addition in calling the writer egotistical and spiteful, makes the assertion that he is fond of attacking defenceless women. Mr. Scott replies that he can actually name a good many who left; that he did not “slate” the play as he might have done, and as to his attacking a defenceless woman, that to him seems a piece of clap-trap. Mr. George Lewis, who is at present out of town, will have his say next. THE AMERICAN CUSTOM. Mr. Scott, in his notice, speaks of the audience following an American custom in silently leaving the theatre. This may be the modern custom, but not long ago the American male disgusted with the performance would throw himself back in his seat and put his legs high on the opposite seat. When the performers gazed into the auditorium and saw rows of boots on view they prepared for the worst, and came down next morning to rehearse a new piece. ___

The Sheffield Evening Telegraph and Star (16 May, 1894 - p.3) THE BUCHANAN-SCOTT SQUABBLE. Mr. Robert Buchanan is endeavouring to force Mr. Clement Scott to “show his hand,” by taking an action for libel against his dramatic assailant. Buchanan has addressed a violent letter to one of the evening newspapers. His tone is as uncompromising as its object is patent. “Shuffler,” “coward,” with open imputations upon Mr. Scott’s “honour” and “veracity,” are among Mr. Buchanan’s choicer temptations to an action for slander. It will be difficult for Mr. Scott to avoid accepting the challenge. . . . BREAKING A BUTTERFLY. Mr. Scott, Mr. Buchanan. Gentlemen? Remember that between you you are breaking a butterfly.—“Man of the World.” ___

From The Theatrical ‘World’ of 1894 by William Archer (London: Walter Scott, Ltd., 1895 - p. 147-150) “A SOCIETY BUTTERFLY.” 16 May. There is a charming eclecticism about A Society Butterfly* the “New and Original Comedy of Modern Life,” by Messrs Robert Buchanan and Henry Murray, produced last week at the Opera Comique. It somehow suggested a revue in which all the plays, not only of the season, but of the age, were stirred up together in a monster medley. The authors avowed, in a certain sense, their obligations to Francillon, while broadly hinting that they meant to write the play Dumas ought to have written. They did not mention their annexation of the rehearsal scene from Frou-frou, holding, no doubt, that the thing was too obvious to call for remark. So it was, of course. When one quotes “The quality of mercy is not strained,” or “The curfew tolls the knell of parting day,” one does not feel bound to add (Shakespeare) or (Gray) on pain of an accusation of plagiarism. The only wonder was that the characters concerned—Captain Belton and Mrs Dudley—did not seem to remember that they had seen all this before, at the theatre. Mrs Dudley’s tirade on marriage occurs in substance in Francillon, but in form it rather suggested Cyprienne’s great outburst in Divorçons. The sporting Duchess is evidently introduced out of compliment to Mr Pinero; but the authors do not seem quite to have realised that the humour of “George Tidd” in Dandy Dick lies in the contrast between her stable slang and the severely ecclesiastical atmosphere of the Deanery. Here there is no such contrast, and to make up for its absence the authors have mixed their slang into a much thicker and coarser “mash,” as her Grace would say. Except, perhaps, “Yes” and “No,” she utters not a word that does not reek of the loose-box. She is really more akin to the “Shiver-my-timbers” Jack Tars of forgotten nautical melodramas than to any character of rational farce. Her “Home for Decayed Jockeys,” by the way, was anticipated by Mr Spencer-Jermyn in The Hobby Horse. The play, then, is practically Francillon writ tedious, eked out with reminiscences from a host of other plays, and spiced with an abundance of satirical allusions in Mr Buchanan’s well- known style. As it is one of my most cherished principles that the true artist should, or rather must, write primarily to please himself, I am bound to approve Mr Buchanan’s satire, which evidently delights him—and him alone. When an author crams his works with satirical “hits” which very few understand and no one cares about, it is impossible not to admire his devotion to his ideal. For example, how many persons understood what Mr Buchanan was driving at in the chatter about Mrs Harkaway’s Last Divorce? And how many of those who recognised the sneer at The Second Mrs Tanqueray were in the smallest degree entertained or gratified by it? There was a good deal of weird talk, too, about an alcoholic German masterpiece, from which I conjecture that Mr Buchanan has been reading Gerhart Hauptmann’s Vor Sonnenaufgang. I too happened to have read the play; but it is a hundred to one that not another soul in the audience had the slightest idea what “Herr Max” was talking about. Mr Buchanan and I, then, had the joke all to ourselves, and of course we relished it hugely; but the rest of the audience must have wondered what we were chuckling at, and felt rather “out of it.” And perhaps, after all, it was not Vor Sonnenaufgang that Mr Buchanan was aiming at; in which case he succeeded in keeping the drift of his satire entirely to himself, and realised to the full the great principle of “Art for the Artist.” The audience, irritated by long waits, was inclined to resent these cryptic allusions, and the gallery audibly expressed its disappointment in a play in which everything is “taken off”—except Lady Godiva’s mantle. Simply as an emotional comedy, and apart from its satiric pretensions, the play is neither better nor worse than a good many that one sees, and might have passed muster fairly enough. Mrs Langtry wore several gorgeous and one or two really beautiful dresses, but her powers of dramatic expression seemed to have grown a little rusty in retirement. Miss Rose Leclercq was exceedingly good as the Duchess of Tattersall’s; Mr F. Kerr played a difficult part with discreet humour; and Mr W. Herbert, Mr Allan Beaumont, and Mr Edward Rose all made the most of their opportunities. * May 10—June 22. On the second night, Mr Robert Buchanan, seconded by his collaborator, read from the stage Mr Clement Scott’s Daily Telegraph notice of the play, and made a vehement retort.

A Society Butterfly - continued

|

|

|

|

|

|

|