ROBERT WILLIAMS BUCHANAN (1841 - 1901)

|

ROBERT WILLIAMS BUCHANAN (1841 - 1901) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

BOOK REVIEWS - POETRY (10)

North Coast and Other Poems (1867) - continued

The Art-Journal (1 December, 1867 - p.270) |

|

|

[Click the picture for larger image.]

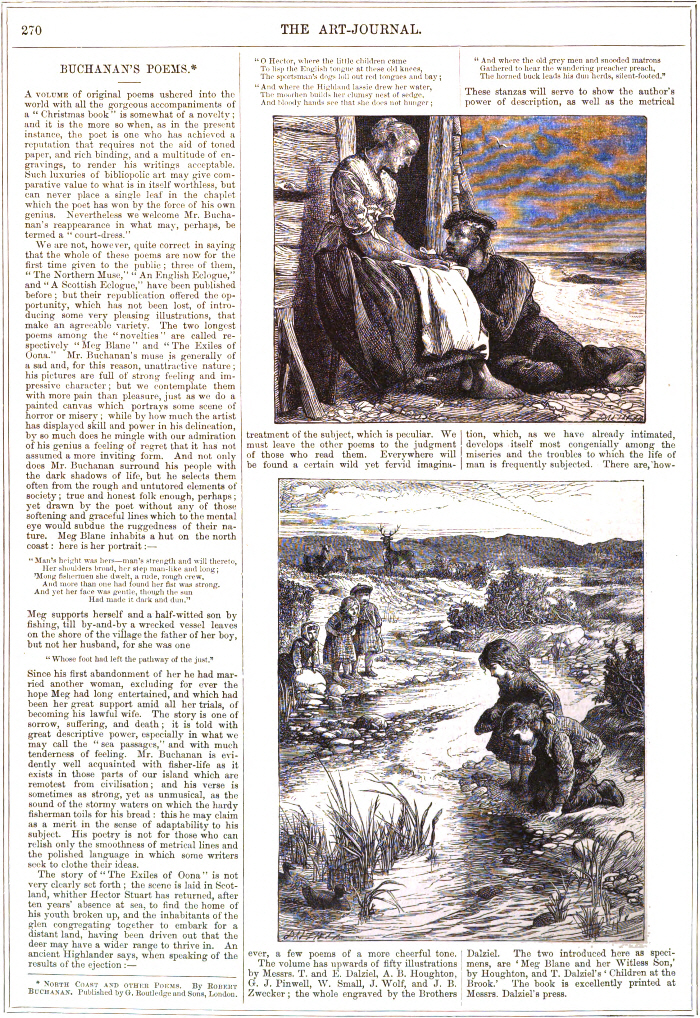

The Argosy (1 December, 1867 - p.80) Writing in view of Christmas, we may, perhaps, shortly mention some Christmas Books. There is, first, “North Coast Poems,” by Robert Buchanan—a beautiful drawing-room volume, on which much care and pains have been spent, and with good result. Here and there we regret to see that the artists have followed and exaggerated a hard and wholly false realism into which Mr. Buchanan has recently fallen headlong, and which the men of the pencil might well have studied to relieve. One specimen of the hard and ungrateful work we may indicate—the illustration to the “Scottish Eclogue,” which, perhaps, faithfully enough reflects the artist’s conception, but which overcomes one with a feeling of disgust. Here the ideal medium, through which alone any form of life can be seen truly, has escaped the poet’s clasp, leaving only the rough garment behind it; and the artist has followed suit, with due result—a repulsive picture. But a few of the poems are fine, and, generally, the illustrations are equal to them—the landscapes and sea-pieces being exceedingly beautiful. ___

Pall Mall Gazette (3 December, 1867 - p.12) BUCHANAN’S NEW POEMS.* THIS volume contains two or three poems well suited to maintain the reputation of the author, among many that are comparatively prolix and uninteresting, and several remarkable only for the most wild and morbid fancies. The illustrations, with the exception of Mr. Wolf’s studies of wild deer and water-fowl, are mostly very dismal things to behold or criticise. They are composed, as a rule, of a few scratchy figures,— Pinnacled dim in an intense inane of nocturnal moors or surges without any fine lights and shades, or any distinct details introduced by way of contrasts. The one accompanying a picturesque couplet (p. 203)— Then sunrise glistening faintly o’er the peaks is more than half composed of a mere patch of ink bounded by five straight lines. The group illustrating the Scottish Eclogue (already some time published) may perhaps be taken to present a humorous coup d’œil, inasmuch as the figure of the minister, who is delivering a tea-table discourse on predestination, is brought into curious relations with the frame of a chair adjacent to his own, and seems to end in a personal appendage characteristic of the Evil One. Some sea-pictures by Mr. T. Dalziel are absolutely preposterous. Altogether the book, in spite of a tolerably handsome binding, contains much that it too good, and much that is too bad, to suit a modest Christmas present; which is what it seems to have been intended for. Lord, with how small a thing The deeply human inspiration of this poem makes it almost appear an incongruous effort to read in the same volume the wild strain entitled “Celtic Mysteries,” where we are called upon to realize how death would affect us if God were to initiate a totally new dispensation, so that the bodies of our friends should suddenly vanish into thin air, and that we might have no relics over which to indulge our griefs. We meet with a yet rasher flight of fancy in the proem, where the Angel of Death, identified with Cain, is supposed to get a long-desired dismissal from his unpleasant duties, the Lord having accosted him with “Thy wanderings, dear Cain, are ended,” &c. The whole vision seems like one that has been produced by the influence of opium. It may certainly suit some minds in which a strong craving has been generated for a novel stimulant; but, at all events, the author’s efforts to connect these lucubrations with a string of serious reasonings and of expostulations with the Deity concerning our human destinies have proved abortive. On the other hand, the “Saint’s Story” is a kind of Ingoldsby Legend, very entertaining, very bold, and very whimsical; but the satire is spiteful and irreverent, and the scenes into which it leads adapted slyly to tickle coarsest appetites. But it is chiefly in the “Poem to David” (an elegy on the author of the “Luggie,” &c.) that Mr. Buchanan has overlaid a fine natural sentiment with an utterly repulsive covering of morbid conceits and fulsome images. It is dismal, he shows us, to think what death seems likely to be when we “lie and rot in cold obstruction,” without power to escape some dim conception of the past and the present, yet even thus we might be content to lie down by the side of a lost friend. No doubt this is a conception which a man of fine feeling might touch upon lightly and tremulously, as where we read in the old ballad— Is there any room at your head, Willy? But all is spoiled in the present poem by an extravagant, even shocking excess of detail, and by the effeminate fondness of such verses as— Were thy lips to mine, beloved, In reading the “Ballad-maker” we are struck, as we have often been heretofore, by the too obvious narrowness of Mr. Buchanan’s notions concerning low life in London. While in Burns’s poems we see beggars or tailors as merry as princes could be, our present author would have us imagine than an exterior of squalor and rudeness is inevitably and incessantly accompanied by an abject and querulous frame of mind. Hence he exaggerates the effects of social position where his countryman has justly reduced their magnitude in our eyes, by showing how the same appetites and affections are constantly at work in all grades of society, since Fortune, as has been said, “gives too much to many, but to none enough.” He is unwilling even to believe that a Londoner can for a moment forget or cease to be sick of the smoke and the strange faces which surround him; by which view he acquires no better a command of his subject than a nautical poet might gain through the phenomena of sea-sickness. His imaginary sufferers, moreover, have a childish and literally lackadaisy longing to meet with the simplest country objects. Then they have never any friends living near them, and no notion, we suppose, of indulging in any convivial intercourse with chance acquaintances. The chief amusement and resource of these heaven-abandoned beings is running to the Old Bailey to see a woman hanged. We could scarcely pick up from any French traveller a queerer notion of metropolitan life than Mr. Buchanan’s books might give if circulated on the Continent, but he has unluckily tried to build elegiac and sentimental poems on a basis only sufficient for the humour of a caricaturist. To such strains, however, we often find a refreshing contrast in his descriptions of natural scenery, which although somewhat too exuberant and circuitous in point of diction are often coloured with peculiar warmth and delicacy. We may instance the description of a marine sunset in the “Exiles of Oona,” and that of the summer’s haunts in “Meg Blane,” to which might be added a number of more rapid sketches. * “North Coast and other Poems.” By Robert Buchanan. With illustrations. (London: Routledge and Sons. 1867.) ___

Illustrated Times (7 December, 1867) Literature. North Coast and other Poems. By ROBERT BUCHANAN. With Illustrations by eminent Artists, engraved by the Brothers Dalziel. London and New York: Routledge and Sons. Anything like an adequate review—not to say a criticism—of this volume would occupy so much of the space which near Christmas time is heavily bespoken, that we shall best serve the interests of author and publisher, as well as most certainly please out own readers, by devoting every inch we can spare, after a word or two of comment, to extracts from the best parts of the book. The artists we regret to be compelled to dismiss in very short space indeed. Where there is so much to praise, it is almost harsh to select a single point for notice; but nobody will miss the extraordinary force with which the countenance of the idiot is rendered on page 51; the beauty of the sea-lights on pages 7 and 186; or the natural charm of the scenes on pages 189 and 213. The last is particularly beautiful. The Scotch elder on page 151 is also capital. We praise these “points” in the artists’ share of the general effect, not because there is not more to praise, but because it is well to be specific here and there, even where one’s space is limited. By-the-by, too, the monk and the lady on page 175 are splendidly done. CELTIC MYSTICS. NO. IX. In the time of my tribulation A short extract from “The Ballad-maker.” This is THE BOY-THIEF’S DREAM. He thought he was in heaven, and it seemed And, lastly, at full length, THE BROOK. Oh, sweet and still around the hill O Brook, he smiled, a happy child, O Brook! in song full sweet and strong And when at last the sleepers cast Our readers know that we consider it of small use to point out faults in work of a certain rank; for the simple reason that the author is sure to know them as well as the keenest critic, to find them out, and to correct them. For the terms in which we have spoken of Mr. Buchanan’s volume no apology is necessary. If in the hierarchy of the agents of human progress the poet ranks highest—for the obvious reason that he has the vision of all that makes life worth while, and the power to put what he sees into “marching music”— no welcome can be too warm for real song; certainly not in a case like that of Mr. Buchanan, where the ordinary functions of a littérateur must hang like panniers on the flanks of the horse of the skies. Our readers will not, we trust, attribute to us any “sentimental” or “maudlin,” views upon this question. But if we reflect upon the long periods of absorption, with nothing to show for them, and the dangerous excitements of sudden accesses of the poetic passion, we shall hardly escape being driven to treat poetry which meets us in this way in a very different spirit from that of those who think they have made a great point by saying (as was recently said so often apropos of this very subject) that Shakspeare muddled and puddled in play-houses and Johnson slaved like a nigger. The answer is obvious—So much the worse for Shakspeare and Shakspeare’s work and Johnson and Johnson’s work. ___

The Times (12 December, 1867 - p.5) Mr. Robert Buchanan has every reason to be well pleased with the manner in which his latest collection of poems has been put before the public. (North Coast and other Poems. Routledge and Sons.) The illustrations are by the Brothers Dalziel, J. Wolf, A. B. Houghton, and other artists, and they are all of great merit. The sea sketches to “Meg Blane” are vivid and powerful, and two drawings, of first-rate excellence, among others, accompany the poems called the “Exiles of Oona”—one on page 211, by Mr. W. Small, and the other on page 213, by Mr. J. Wolf. The poems are fully worthy of the care which has been expended upon them. ___

The Illustrated London News (21 December, 1867 - p.11-12) ILLUSTRATED CHRISTMAS GIFT-BOOKS. North Coast and Other Poems. By Robert Buchanan. With Illustrations by Eminent Artists. Engraved by the Brothers Dalziel. (G. Routledge and Sons.) The strength and sweetness of Mr. Buchanan’s poetical genius, to which we have borne our testimony on former occasions, are yet more effectually manifested in some pieces of this collection. Three of them—namely, “The Northern Muse,” “An English Eclogue,” and “A Scottish Eclogue”—have appeared in print before; the others are quite new. The series entitled “North Coast Poems” are not, as one might have guessed, another batch of those Scandinavian ballads which he brought together for a Christmas book last year, but are narratives, chiefly of humble life—that of peasants and fishermen, with their families or women, on the shores of Scotland. The principal of these, “Meg Blane,” is one of considerable length, in four parts or acts, varying in their forms of versification. The opening canto, and likewise the last, are composed in very melodious irregular stanzas, with a frequent interjection of short lines and with changing intervals or periods of rhyme, probably intended to mark a change in the emotions which are expressed; while the second canto is in blank verse, and the third in regular heroic couplets. This practice of variable verse-structure, which Miss Ingelow and other poets of the day have adopted, is quite an innovation, and is not in general to be commended. It may be pleaded in excuse that the ear is apt to be wearied by the continuance of the same form of stanza or couplet over fifty pages. We certainly prefer the maintenance of one type of outward structure corresponding with the inward epic unity throughout the whole poem. This rule, which is supported by the precedents of Homer, Dante, Milton, and Byron, in their longest as well as greatest works, has been observed till recently by all writers of narrative poetry. But we shall not quarrel with Mr. Buchanan on that account. “Meg Blane” is a true and noble poem, in which the author has had, like Wordsworth, the courage to seek the sources of imaginative interest in the life-sorrows and soul-struggles of a poor lone woman, the mother of an idiot son; a woman deserted and shamed in her youth, now dwelling in a mean cottage on the shore, and labouring with more than a man’s energy and boldness to win their daily food out of the dangerous sea. The man who has left her so many years alone, the father of her dearly-loved but burdensome child, is cast at her feet by a wreck; she saves his life, and she hopes that he will now be her husband; but he cannot, or will not. So her spirit is broken, her strength perishes, and she can no longer buffet the waves. Then only in still weather did she dare Infirmity, poverty, and old age come all at once upon her, in the day of her grief, and she soon feels herself dying:— “O bairn, when I am dead, And so on, till presently she dies; but she is consoled in her last moments by an unspoken divine message, the traces of which are seen in “The fearless sweetness” of her face. The whole story, though as sad as “Enoch Arden,” which it equals in truthfulness of effect, but not in artistic finish, is deeply interesting, and pleases us as much as anything else in this volume. “The Battle of Drumliemoor,” an historical sketch of one of the Covenanters’ most disastrous struggles, is rather deficient in martial fire. “The Exiles of Oona” is a very melancholy poem on the departure of a band of emigrants from a Highland valley, the occasion having a similar interest to that of “The Deserted Village;” but it is comparatively languid and diffuse, and its metrical structure, in triplets of blank lines, seems to lack both freedom and precision. Another of these “North Coast” or Scottish pieces is “The Northern Wooing,” in which an old grandmother tells the children how she went out of the house in the dark night, on Halloween, to see the mystic image of her future lover. This is the subject of the design, by Mr. A. B. Houghton, which we have borrowed. The passage is highly effective:— Dark, dark was all, as, shivering and alone, Could the incident be more plaintly and forcibly described? Mr. Buchanan excels in this power of assembling the attendant circumstances of an action, with a fine sense of their congruity and of their tendency to deepen its impression on the mind. He does not, as even Miss Ingelow and Mrs. browning have sometimes done, bring in particulars which are needless for that purpose, and which may appear trivial or grotesque. In this respect he is guided by an instinct of æsthetic fitness, which seldom fails. The most perfect, we think, of his poems, and one of the most beautiful of its class, is “Sigurd of Saxony,” a kind of allegory of the spiritual state of one waiting and watching at the verge of our mortal life, who has there parted company with the sainted mistress of his heart, and who has devoted the remainder of his days to the sacred task of purifying himself from evil, That with a stainless spirit I may take He is a knight of mediæval chivalry, as devoutly constant as the Sir Galahad of Tennyson in quest of the “Holy Graal;” but all his hope is to be fetched away to rejoin the heavenly object of his affections:— Long have I waited here, alone, alone, In explanation of this, be it understood that he is frozen into a statue, and fixed to the earth as he stands, until the appointed hour for his departure. Twice has the ghostly barge returned, once for an aged man and once for a child, when Sigurd was unable to move. But now he is patient, and he waits, with quiet heart and brain, until the due moment of his reprieve. This is a very striking conception, and wrought out with a masterly hand. Another quasi-mediæval subject, that of “The Saint’s Story,” is, on the contrary, one essentially disgusting. Mr. Buchanan should have let it alone. We would rather say nothing more about it. “The Ballad-maker” is a homely idyll of London life, as plain as a piece of Crabbe’s, but with touches of higher imagination and of deeper poetic feeling. It tells of a poor crippled boy whom the ballad-maker, in his charity, nursed while dying, and cheered with the best songs in his stock, chanting to him of the green fields and the great sea, as he lay in a squalid garret of this city. “The Ballad of the Stork” is a good story, very well told. We have by no means exhausted all the contents of this noble volume. The series of weird elegies and prophecies, called the “Celtic Mystics,” open a separate field of criticism; but Mr. Buchanan is apt to become uncouth and obscure in his mystical vein. The view of an Arctic landscape, with a reindeer, designed by Mr. Zwecker, which illustrates one of these pieces, is worthy of notice. So are many of the drawings by Messrs. T. and E. Dalziel, Mr. Wolf, Mr. Small, and others, which are engraved by the brothers Dalziel in their usual style. The very binding of the volume deserves remark, being adorned with a decorative pattern and lettering of a most graceful artistic design. ___ The Nation (26 December, 1867 - Vol 5, No. 130, pp. 524-25) North Coast, and Other Poems. By Robert Buchanan. With Illustrations. (New York and London: George Routledge & Sons. 1867)— Mr. Buchanan’s strength as a writer seems to lie almost wholly in the fulness and tenderness of his sympathy with the poor, the unfortunate and the criminal, the lowly and the low. He says in the prelude to his miscellaneous poems: “My full heart hungers out unto the stainèd.” So it does. We may add that this hunger is not often expressed with much more of force or beauty than in the verse above quoted. We should not send any one to his poetry for anything more than the pathos of the facts of daily life in “the cottages where poor men lie;” the huts and cells where men and women lie whom poverty has driven into crime or error. And we should beforehand advise the reader not to expect that Mr. Buchanan either greatly heightens the pathos of the facts or beautifies it by the charm of his imagination. He does not, to our apprehension. There is the narrative; he invented it or he discovered it—to do the one is as easy as to do the other—and besides this there is not much. Yet there is something besides this. He is not destitute of humor or of imagination, and his pitying sympathy has given him insight into the motives and feelings of the class of people which he has most studied. There is something more than sympathetic presentation of facts in the “Scottish Eclogue,” in “The Ballad-Maker,” and in parts of “Meg Blane.” Imagination had a finger, if not a hand, in the production of them. We copy a passage from the last-named poem. Meg Blane has been seduced, twenty years since, by a lover who deserted her, promising to return. She, meantime, lives as a fisherwoman, rearing her son, an idiot, to man’s years. “Bearded,” Mr. Buchanan very often calls him, for he has a way of repeating favorite words which would seem to prove his vocabulary limited. He, meantime, forgets her and marries another. He is cast ashore, by shipwreck, near Meg’s hut, and she speedily finds that the hope she has been so long cherishing is a vain one. The dying out of her love for him is thus told: “Over this agony I linger not, This seems true to nature everywhere, among high and low, and it would not be fair to the author to say that he found it in the story. Meg sickens, losing all her courage; her life died with her love, and she pines away. Her witless son waits on her in her illness; and the poet has well imagined the effect on his behavior of his mother’s woes. Or, as one may say—seeing how in other things, when facts cannot help him, his imagination mostly fails him—he has closely studied and sympathetically reproduced all the features of a case which actually fell under his observation. In the other case the sympathetic imagination seems to have been at work, and in this one sympathetic observation. We may as well say here that in the “Battle of Drumliemoor,” “The Saint’s Story,” the very disagreeable “Poem to David,” and certain other pieces where Mr. Buchanan escapes wholly from facts and trusts himself to his unaided powers, he makes a bad failure. This is the description of the idiot son’s imitative sadness: “And now there was a change in his sole friend Giving to the best pieces of the book the praise we have given it, and adding to that the further praise that it has passages of natural reflection well enough expressed, and some not excellent but good descriptions of natural scenery, we will say, on the other hand, that frequently the poet is heard speaking through the personages of his story instead of letting them speak for themselves, and that he too exclusively gives himself up to the harrowing. Both are artistic faults, and both have the same origin. Close adherence to his original, accurate and comprehensive portrayal of the life he tries to paint, would have saved him from the one and the other; then his farmers would never talk Buchanan, nor would all his low life be low life made—to the sacrifice of truth—on the single theory which the poet has chosen as most effective on the reader’s feelings. Of his usual matter and manner the passages we have quoted above afford a specimen rather favorable than otherwise. But we have already sufficiently described the book. Mr. Buchanan is, so far as he is at all valuable, a poetical preacher of love and charity, enforcing his text by moving examples. Thus he does a noble work; and he does it more than tolerably well, but is hardly a poet, or he would not have chosen themes that might better have been treated in prose; at the utmost, would have treated them less prosily. The binding of the volume, a heavy octavo, is elaborately fine, red and green and gilt cloth, with bevelled edges; the paper is tinted and heavy; the type is large ad clear; the illustrations are many——most being ugly—and altogether the book, as regards inside and outside, is good enough to constitute a pretty and valuable holiday gift. ___

The Round Table (28 December, 1867 - No. 153, p.434) North Coast, and Other Poems. By Robert Buchanan. With Illustrations. London and New York: George Routledge & Sons. 1868.—Mr. Buchanan has indulged in the innovation of first putting forth his new poems, some, no doubt, of which he is (justly) proud, in a volume gorgeous with crimson and blue and gilding, so that they will present themselves to many as they do to us now, in the capacity of a gift book and not of poems to be enjoyed for themselves. This is a pity, for Meg Blane, the first of the poems of the North Coast, and others which follow it are very true and touching fulfilments of the poet’s purpose as expressed in his Prelude, printed, oddly enough, in the middle of the book: “I have a word to leave upon my tombstone; In its success as real poetry we are inclined to believe, for reasons that we must reserve until we are better able to give them; as a very beautiful specimen of holiday-bookmaking there can be no doubt about it. Such workmanship as only comes to us from abroad, with over fifty engravings by the Dalziel Brothers from designs by half-a-dozen skilful artists and the splendors of binding to which we have alluded—the whole is a most brilliant table ornament, one of the prime essentials of a gift book. ___

The Morning Post (30 December, 1867 - p.3) LITERATURE. NORTH COAST AND OTHER POEMS.* Similar to his “Wayside Posies” last year, this volume of Mr. Robert Buchanan’s “North Coast and other Poems” takes a high place among the illustrated books of the present season. It may almost be said to outrival its predecessor in the number and beauty of the engravings with which it is embellished by the Brothers Dalziel and other eminent artists. Unlike, however, the collection in his former work, all the poems are from Mr. Buchanan’s own pen, although they are still of varied character. Only three of them have appeared before—“The Northern Muse,” “An English Eclogue,” and “A Scottish Eclogue;” the others are now published for the first time. The first and longest, “Meg Blane,” is of the narrative order, as may be inferred from its title. It is written in changeful metre, and contains some fine passages, especially in describing the effects of deep passion or suffering on the human mind. The intense yearning of Meg Blane through long years to behold once more the faithless lover of her youth, and her feelings when this desire is unexpectedly gratified, give full scope for some striking word-painting. The change which comes over her afterwards is also finely portrayed, and the closing lines of the description may be quoted as giving a true picture of a woman’s hardening heart:— “But ere the man departed from the place, There is the same truthfulness to nature and deeper pathos in the stanza which tells how her witless son unconsciously showed his sympathy with her sorrow; thus— “But, lo! unto the shade of her distress One other extract may be given from the last lines of “The Battle of Drumliemoor,” as affording a vivid, though brief, description of that sad scene, a snow-clad battle-field:— “And while the widow groans, lo! God’s hand around their bones Still the poems are certainly rendered less attractive by many of the ideas they present being clothed in vague, fantastic language and fitful metre, perfectly consonant, no doubt, with the tone of North Coast songs and legends, though little adapted to the prevailing taste of the age. The “Celtic Mystics” indeed, with which the volume concludes, are altogether too mystic and shadowy to be either generally intelligible or appreciable. The imaginative is carried to too high a pitch; and occasional instances are also observable throughout the poems where Mr. Buchanan commits that too prevalent error among modern writers of using expressions which stretch poetic license to the verge of sacrificing sense to sound. The style in which the volume is brought out and the illustrations deserve the highest commendation. Not only are the engravings admirable as presenting vivid pictures of the scenes described in the poems, but worthy to be estimated as rare works of art. They display in an eminent degree, both as regards design and execution, marks of that genius for which the Brothers Dalziel, Pinwell, Small, and the other noted artists who produced them, are so justly celebrated. * North Coast and other Poems. By Robert Buchanan. With Illustrations by eminent artists. Engraved by the Brothers Dalziel. London: George Routledge and Sons. ___

Putnam’s Magazine (January, 1868 - Vol. 1, p.129) IT is somewhat difficult to settle down to a critical estimate of an author’s poems, when the verses come to us in such fine holiday trim as the poems Lucile, by OWEN MEREDITH (Ticknor & Fields), and “North Coast, and Other Poems,” by Robert Buchanan (Routledge & Sons). The eye is first attracted by the brilliant decorations, the thick, glossy paper, the gold-leaf, and the manifold artistic graces of the Brothers Dalziel; and it is not till, as it were, we have divested the beauty of her ball-room finery and extravagance of dress, that we are able to see her in her simple personal attractions. It is Ball and Black with their diamonds, or the laces and silks of Stewart, or the skilful manipulations of Dieden that we are for the time admiring. The lady’s turn comes at last, and we forget them all. We may, however be doing injustice to the brilliance of the attire in which their publishers have invested two of the favorite authors of the day, since, though rich, it is in exceedingly good taste, and the merit of the productions is proof against any application of the old saying of the workmanship surpassing the material. Besides, the realistic character of the illustrations has its subduing effect, bringing the gazer down to a sober appreciation of the text. The reputation of “Lucile,” indeed, is sufficiently established; for, has it not been in “blue and gold,” and consequently in the hands of all fair readers of poetry in America, a familiar companion, since its first publication?—a charming novel, with its society airs and more private sensibilities and heart adventures, tickling the fancy with its seemingly careless but more artistical rhyming. Now, with its portrait of the author, Robert Lytton, as a frontispiece, a countenance marked with the impress of thought and feeling, and the finely-drawn, earnest, and, at times, passionate illustrations of Du Maurier, the work may fairly be said to renew its existence. ___

The Contemporary Review (February, 1868 - Vol. VII, p.303-304) VI.—POETRY, FICTION, AND ESSAY. The North Coast, and other Poems. By ROBERT BUCHANAN. With Illustrations WE own to not being easy in mind about these gorgeous scarabæan books, which are making the temples of the Sosii flare with gold, and green, and crimson in our days. It may be morose and ill-boding to feel as if our lighter literature were passing away in a December sunset; or it might be invidious to compare it to a nymph who, for want of charms certain to tell, is obliged to flaunt in loud colours, and challenge us with, “Look at me!” ___

The Globe (18 June, 1868 - p.1) LITERATURE. THE TWO BUCHANANS.* Odd as it may appear, there are evidently two Robert Buchanans, both of whom set up to be poets. One of them is the irrepressible gentleman who appears in all manner of monthly periodicals, who dedicates to Mr. Hepworth Dixon, and who is occasionally almost poetical. The other was sometime Professor of Logic and Rhetoric in the University of Glasgow. We hardly know which we like least. “O injured Wallace! There are five dramas in professor Buchanan’s two volumes, and they are wonderfully supplied with notes of exclamation. But Mr. Constable has ample founts of type. “O fairest of the village train! “But must that form—and form so rare This is queer enough, but the Professor can do queerer things, as the following quatrain shows:— “Ah, fatal thirst! ah, fond aspire! What’s an “aspire?” And what, oh, what, is a “Dis-Edener?” “First, by the cinders rescued from the flame Saintly talking, doubtless. The story is, as a whole, more disgusting than this extract—but it has some power. * “North Coast” and other poems, by Robert Buchanan. London: Routledge. “Tragic Drama from History,” by Robert Buchanan. Edinburgh: Edmonston and Douglas. Back to Reviews, Bibliography, Poetry or North Coast and Other Poems. _____

Book Reviews - Poetry continued The Book of Orm (1870)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|