|

|

|

|

|

ROBERT WILLIAMS BUCHANAN (1841 - 1901)

|

|

|

|

THEATRE REVIEWS

29. Clarissa (1890)

Clarissa

by Robert Buchanan (adapted from the novel, Clarissa Harlowe; or the History of a Young Lady by Samuel Richardson).

London: Vaudeville Theatre. 6 February, 1890 (matinée).

London: Vaudeville Theatre. 8 February to 18 April, 1890

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

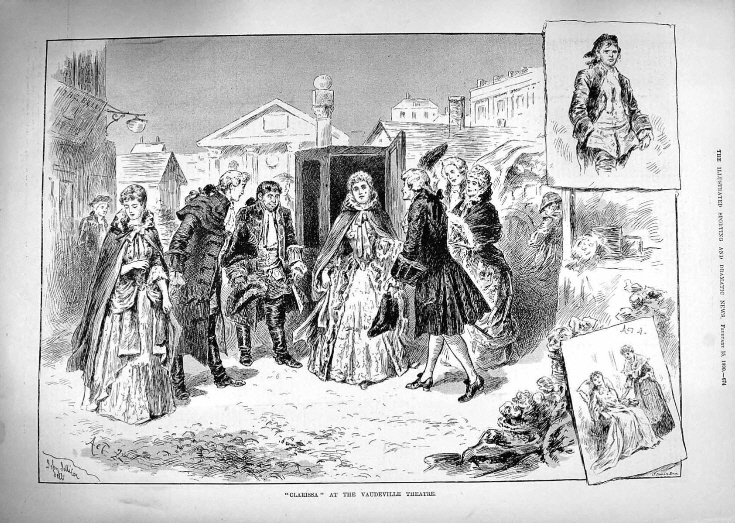

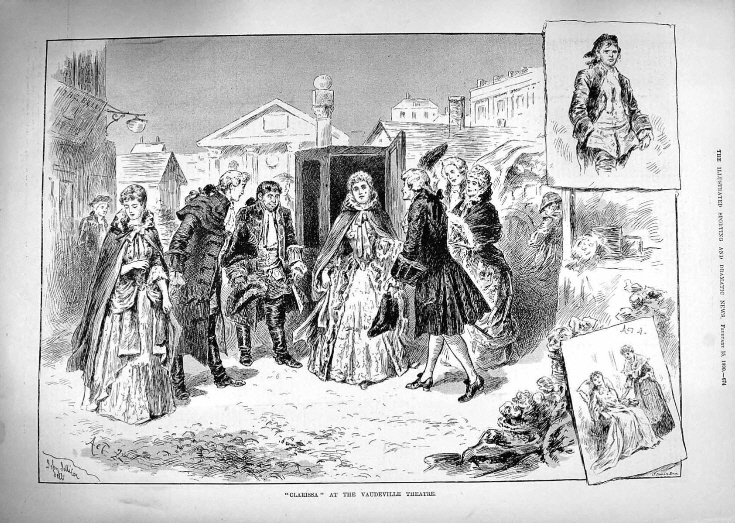

[Winifred Emery as Clarissa Harlowe.]

The Manchester Weekly Times (26 October, 1889 - p.3)

The centenary of Samuel Richardson is not to pass away without an attempt on the part of English dramatists to adapt for the modern stage the story of his masterpiece, “Clarissa Harlowe.” Mr. W. G. Wills has written a play on the subject for Miss Isabel Bateman, and Mr. Robert Buchanan has had for some time in preparation a drama called “Clarissa,” commissioned expressly by Mr. Thomas Thorne. It is now probable that the reproduction of the “Old Home” at the Vaudeville will be postponed, and that the Richardsonian drama will re-open the regular Vaudeville season next month.

In “Clarissa” Mr. Buchanan has departed considerably from the lines of the original story, and has introduced, as in the case of “Joseph’s Sweetheart,” new sets of characters. He has adhered, however, as was inevitable, to the tragic termination.

___

The Academy (2 November, 1889 - No. 913, p.294)

THE announcement is made that we are to have a stage version of Clarissa Harlowe, and that it is that arch-adapter, Mr. Buchanan, who is to furnish the same. Mr. Buchanan’s task will not be a light one, though we are reminded by the Daily News that it is by no means the first time it will have been undertaken. Clarissa has already, it appears, served the purposes of opera. That, however, is not much to the point—in the hands of a soprano we can imagine Clarissa’s woes might be effective. What is more noteworthy is the fact—of which our contemporary likewise reminds us—that in Paris (it was rather more than forty years ago) the story was to some extent drawn upon in a drama at the Gymnase, in which the Lovelace was impersonated by M. Bressant, and the Clarissa by Rose Cheri, the blameless and delightful actress who afterwards married M. Montigny, the manager. As we are upon the subject, it may be worth while to record what is, however, not hidden from anybody who knows France—that Clarissa Harlowe is one of the two English classics which every literary Frenchman knows and takes to his heart. Balzac was never tired of implying his admiration of it. The other classic is, of course, Sterne’s Sentimental Journey.

___

The Morning Post (4 November, 1889 - p.2)

With reference to the projected Vaudeville production of a version of “Clarissa Harlowe,” by Mr. Robert Buchanan, at an early date, Mr. W. G. Wills wishes to have it known that his adaptation, about to be presented by Miss Isabel Bateman in the country, was completed six months ago.

___

The Western Daily Press (30 November, 1889 - p.7)

Mr Robert Buchanan read his new play on the subject of Richardson’s “Clarissa” to the Vaudeville company on Monday last. Mr Thomas Thorne, Mr Fred Thorne, Mr Cyril Maude, Mr Harbury, Mr Gillmore, and Mesdames Winifred Emery, Marian Lea, and Madge Bannister will all be in the cast.

___

The Glasgow Herald (2 December, 1889 - p.4)

The Vaudeville Theatre was re-opened on Thursday night with “Joseph’s Sweetheart.” The present arrangement, however, is only a temporary one, as Mr Robert Buchanan last Monday read to the company the new play he has written on the subject of Richardson’s “Clarissa Harlowe”; and the piece is now in rehearsal. One of the principal scenes is to be a life-like representation of Covent Garden Market 140 years ago. Mr Buchanan has invented a part for Mr Thorne not to be found in the novel. The character of Clarissa Harlowe herself will be entrusted to Miss Winifred Emery.

___

The Stage (6 December, 1889 - p.9)

Robert Buchanan’s adaptation of “Clarissa Harlowe,” is now being carefully rehearsed at the Vaudeville. Mr. Thomas Thorne will very wisely try his new venture first at a matinée, after his wont. In the cast I am pleased to see the name of Miss Lillie Hanbury, a clever little lady, who shows great promise.

___

St. James’s Gazette (20 December, 1889 - p.5)

The management of the Vaudeville Theatre, anxious to be in advance of the Christmas novelties, are doing their utmost to have Mr. Robert Buchanan’s new play, “Clarissa,” ready for production on Tuesday afternoon. Due to this circumstance, Mr. H. B. Conway, unable to reach London in time, will not, as originally intended, play the part of Lovelace, which has now been assigned to Mr. Thalberg, an actor who has been doing good work with Miss Hawthorne in the provinces. Messrs. Thomas and Fred Thorne, Mr. Cyril Maude, and Misses Emery, Banister, Hanbury, and Collette are also in the cast. In connection with this it may be mentioned that Mr. Wills’ version of Richardson’s novel was produced this week at Birmingham with a result which does not appear to have been wholly satisfactory.

___

The Daily News (23 December, 1889 - p.3)

Rumour has it that Mr. Robert Buchanan in writing his forthcoming version of “Clarissa Harlowe,” for the Vaudeville, has derived “much assistance” from the old French piece, of which we lately gave some account. We hope and believe that rumour will prove on this occasion to be mistaken. The French piece, though Bressant as Lovelace and Rose Chéri as the heroine were thought very charming in their day, was a dull and monotonous production. A version in which Webster and Mrs. Honner were playing in London forty-three years ago follows this original pretty closely; but it would certainly be too absurd for modern tastes. It abounds in such passages as—“Clarissa (disengaging herself by a sudden effort, and with high majesty and authority. This is done by pressing her hand to her forehead, and him backward): Kneel, kneel, base renegade to the honour of man. Kneel, and ask forgiveness of her you have thus dared to insult! (Lovelace shrinks back, cowed as if in spite of himself.)” The repentant scoundrel, Macdonald, speaks of a “decent throb of feeling” that “crosses his mind;” and Lovelace is instructed by the stage directions to assume “a reckless and sardonic smile.” In the last scene Clarissa makes her will, and, apostrophising her absent father to the accompaniment of “soft music,” exclaims: “My mortal remains! Oh! father, listen to this earnest prayer—accord me a place in our family tomb!” This, and many other absurdities of the sort, are not, it is true, without Richardsonian suggestion; but such passages would be apt in these days to provoke ill-timed laughter. Mr. Buchanan’s scenes, which include Covent-garden Market in the Hogarthian time, and a quaint dairy farm of the period, take a wider range, and his dialogue is little likely to fall into this artificial vein. Miss Winifred Emery plays Clarissa; Mr. Thorne, Belton, an interpolated character; Mr. Thalberg, late a member of Mr. Benson’s company, Lovelace; Mr. Fred Thorne, Lovelace’s repentant abettor Macshane; and Miss Ella Banister, Hetty Bolton, another character introduced by the dramatist.

___

The Sheffield and Rotherham Independent (23 December, 1889 - p.8)

Mr. Thomas Thorne has decided to produce “Clarissa” at the Vaudeville so early as next Tuesday afternoon. The part of Lovelace will be taken by Mr. Thalberg, a young actor new to London, of whose ability Mr. Buchanan has formed a very high opinion. Miss Winifred Emery will be the heroine, and Mr. Thorne himself will play Lovelace’s scapegrace friend Belton. There are several important characters not in Richardson’s cumbersome work.

___

Pall Mall Gazette (31 December, 1889 - p.1)

This pleasant balmy climate of ours has been doing its deadliest in theatrical circles during the last few days. Mr. Tom Thorne has been the victim of a severe cold and Mr. Robert Buchanan has also been laid up with some bronchial trouble. “Clarissa” is consequently shelved for the moment, though I doubt not that when author and actor are themselves again a very few days will suffice to complete the preparations for the young lady’s appearance.

___

The Daily Telegraph (24 January, 1890 - p.3)

Both Mr. Thorne and Mr. Buchanan having recovered from their recent indisposition, the rehearsals of “Clarissa” are again in progress at the Vaudeville. Mr. Thorne returns from Monte Carlo early next week, and as scenery, dresses, and all accessories are already complete, the play will probably be produced before the end of the month.

We are requested by Mr. Buchanan to state that he can lay no claim to the merit, ascribed to him in several quarters, of having reconstructed and rewritten the third act of “Marjorie.” Although he undertook the task of revising the libretto, and of adding one or two songs, only a small portion of his structural alterations was adopted, and the third act, now perhaps the most popular in the piece, was almost entirely the work of another and thoroughly-competent hand.

___

The Times (7 February, 1890 - p.6)

VAUDEVILLE THEATRE.

The interminable prolixity of the novels of Richardson and the forbidding character of the epistolary style in which they are written have long relegated them to the upper shelf; but readers who search sufficiently will still find in these prototypes of the realistic novel a considerable vein of dramatic ore. More particularly may this be said of “Clarissa Harlowe,” of which a remarkably successful version by MM. Dumanoir, Léon Guillard, and Clairville was produced in Paris in 1846, affording the famous Rose Chéri the occasion for one of her earliest and greatest triumphs. The French Clarisse was readapted more than once to the English stage, but for some reason the story never attained a great degree of success in London, even when played by Mrs. Stirling and Charles Mathews. Nor does a recent American version by M. Dion Boucicault appear to have been more fortunate. Undeterred by the fate of the past English adaptations, however, both Mr. Robert Buchanan and Mr. W. G. Wills have recently dramatized Richardson’s masterpiece afresh; and the former author’s version was yesterday afternoon brought out at the Vaudeville, under circumstances of the most promising character. Indeed, the story as handled by Mr. Robert Buchanan and the Vaudeville company, more particularly by Miss Winifred Emery in the part of the martyred heroine, is not unlikely to attain the vogue of the old Gymnase play, which, of course, the adapter has carefully studied.

It is easy to see what dangers beset the adapter of “Clarissa Harlowe.” The story is a painful one from the beginning, and has to be conducted to an appropriate conclusion, without regard to that dramatic bugbear, an unhappy ending. For a union between Clarissa and Lovelace—whose name, by the way, as a synonym for libertine has passed into French, as it would probably have done into English had it not been supplanted by Byron’s Don Juan—is out of the question and has never, we believe, been attempted even by the school of adapters who, in the last century, allowed Romeo and Juliet to “live happily ever afterwards.” As a pure-souled martyr to the “polluting hand of man,” Clarissa must accordingly be exhibited by author and actress both in a singularly angelic light; the tyranny which drives her forth from the paternal roof must be odious in the extreme, and all the measures resorted to by her abductor in order to compass her ruin must be correspondingly heartless. By such means alone can the public be brought to acquiesce in the apotheosis of a young lady who, prosaically speaking, only meets with the fate of the common and generally unregarded female “outcast” of melodrama. Mr. Buchanan has very skilfully done his work in this respect, and from Miss Winifred Emery he has received invaluable assistance. Upon the representative of the hapless Clarissa the whole sympathetic interest of the story depends; her virginal air and sweetness count for quite as much as the constructive art of the adapter, and, failing such adventitious aids, the play would be in imminent danger of falling to pieces. Miss Emery in this part is a worthy successor to the fascinating and talented Rose Chéri.

The changes now imported into the story relate chiefly to the manner in which the death or expiation of Lovelace is brought about. In the French play the avenger was Clarissa’s uncle; in the novel he is her cousin. Mr. Buchanan, on the other hand, magnifies the character of Lovelace’s disreputable henchman, Philip Belford, and transforms him into the libertine’s executioner on the ground that his sister, like Clarissa, has also been betrayed. By this device a congenial and important part if provided for Mr. Thomas Thorne, who is allowed to figure in Lovelace’s conspiracy, instead of, like his French prototype, l’oncle terrible, merely swooping down at the last as a deus ex machinâ. Lovelace finds in Mr. Thalberg a very spirited and plausible representative. This young actor is, comparatively speaking, a newcomer at the Vaudeville, but his present performance will assuredly win him a high position in the handsome young profligate line of character. Some picturesque types are scattered over a not too numerous cast. Among these may be mentioned the Mr. Solmes of Mr. Cyril Maude, the old and decrepit suitor who is thrust upon Clarissa by her father and the Captain Macshane of Mr. Frederick Thorne. Of the former, as well as of Clarissa’s father, who is forcibly played by Mr. Harbury, we unfortunately get but a glimpse; and, indeed, Mr. Thomas Thorne is not so well served in this piece as in Sophia or Joseph Andrews. But for these drawbacks the winning performance of Miss Emery abundantly compensates. Clarissa is altogether an eminently enjoyable and wholesome play; and it will, of course, forthwith take, and no doubt long hold, a place in the evening bill.

___

The Morning Post (7 February, 1890 - p.3)

VAUDEVILLE THEATRE.

_____

Mr. Robert Buchanan’s long-promised drama, “Clarissa,” was produced yesterday afternoon, and was received with marked favour, the author and the principal performers being called for and greeted with hearty applause at the fall of the curtain. “Clarissa,” as the author frankly admits, departs widely from the novel of Richardson. Many of the scenes belong rather to the modern French school than to the simple prolix narrative style of the author of “Clarissa Harlowe.” Mr. Buchanan has, as he himself tells us, kept to the spirit and not to the letter of the original story. Therefore he has freely borrowed from other sources, and, in one act especially, makes use of the chief incident of the play by MM. Dumanoir, Gillard, et Clairville, produced at the Gymnase, Paris, as far back as 1842. In the earlier scenes there is the persecution of Clarissa by her father and brother, in order to induce her to marry the wealthy Mr. Solmes. Then follows the treacherous plot of Lovelace to entrap the poor girl into a false marriage, when she discovers that scandal is busy with her name. But to give a deeper dramatic motive, Mr. Buchanan makes one of the agents of Lovelace the avenger. Philip Belford, after having assisted the seducer in his scheme, discovers that his own sister has been the victim of Lovelace, and from that moment resolves to defend Clarissa. But when the heroine ascertains that she has been deceived, and Belford threatens Lovelace with punishment, he is tempted to drink some wine that has been drugged, and at the critical moment he loses all power to defend Clarissa, and at the end of the third act she is completely in the power of her betrayer. The fourth act is chiefly occupied with the agony and death of the heroine, who has found a shelter with Belford and his sister. Belford meanwhile sternly resolves if ever he meets Lovelace again to cross swords with him. In a half- repentant mood the seducer comes to the cottage where Clarissa is staying, and implores her to consent to a real marriage to atone for the wrong he has done her; but Clarissa is dying, and declares that she “gives her soul to God, leaving to earth the frame polluted by man.” But Nemesis is at hand. Belford has followed Lovelace, they fight, and the betrayer falls, forgiven in his dying moments by the heroine. There will be much discussion, some of it probably antagonistic, respecting this play, because of its sombre subject, and of the painful situation in which the heroine is seen, defenceless against the arts of triumphant vice. These are the present drawbacks upon a powerful and interesting drama, which secured the fullest attention of a large audience. Perhaps, also, the Scriptural tone of the entire last act might with advantage be modified. Great praise must be given to the acting. Miss Winifred Emery, as the heroine, was graceful and pathetic in the extreme. There were few dry eyes in the theatre during her final pathetic scene. Seldom has this charming actress been seen to such advantage. Miss Ella Banister, as the sister whose seduction leads to the catastrophe, acted with much force. Miss Mary Collette, as a simple country girl, was clever; and Miss Bryer and Miss Wemyss, as the pretended ladies of fashion, acquitted themselves well. Mr. Thomas Thorne, who was received throughout with great warmth, played with admirable skill. Mr. Thomas Thorne as an avenger is something quite novel. But none must suppose that he failed to do such a character justice. By genuine ability and earnestness Mr. Thorne succeeded in making the part of Philip Bedford one of the most interesting in the drama. Mr. Thalberg, who recently made his début in “The School for Scandal,” proved himself a capable young actor as Lovelace, although he has still something to learn. He spoke his lines effectively, and in many of the scenes fully realised the character of Lovelace, his worst fault being an excess of gesticulation. Mr. Fred Thorne was amusing as Captain Macshane, and Mr. Cyril Maude was excellent as the pompous elderly lover. Even if “Clarissa” should not enjoy such favour as some of the author’s previous dramas, owing to the sad theme he has chosen, there will be few playgoers who will not be curious to see how Mr. Buchanan has treated this novel of bygone days, and possibly both author and manager will perceive after this trial performance where some slight alterations may be judiciously made, thus adding to its chances of popularity.

___

The Standard (7 February, 1890 - p.2)

VAUDEVILLE THEATRE.

_____

Mr. Robert Buchanan has made an exceedingly effective play, or, at any rate, three acts of one, out of “Clarissa Harlowe.” The last act, which is unnecessarily diffuse and wide of the purpose, can easily be shortened and amended, and then there can be little doubt that Mr. Thorne will have achieved another decided success. Clarissa, as Mr. Buchanan calls his play, altogether departs in several respects from the novel. There is nothing like the Philip Belford of Clarissa in Richardson, and his sister Hettie is a new personage; and the reader who is familiar with the original will best understand what has been done from a sketch of the Vaudeville play. The action opens at the dairy near Harlowe Place, where Lovelace, disguised in rustic clothes, finds Jenny busy churning, and ready to sympathise with his love for her mistress. Mr. Solmes is persecuting Clarissa with his attentions, which are formidable, as her stern father and cold- hearted brother are bent on the match, and so Lovelace comes at a fortunate time, the more so as he has laid his plot well and has three unscrupulous friends to assist him, notably Captain Macshane, who plays parson at a pinch. Lovelace induces Clarissa to accept his escort to London, where he promises to place her under the protection of ladies of quality, his kinswomen; and the girl trusts herself to his guidance.

The second act takes place at daybreak in Covent-garden Market. Already the business of the day has begun; girls are sorting their flowers, porters pass with their loads. At a coffee-stall a wretched worn-out girl sleeps—Hettie Belford, one of Lovelace’s former victims; and here presently he arrives, escorting Clarissa to the Bell Inn, till his “cousins” are ready to receive her. Belford—who as yet knows nothing of Lovelace’s share in his sister’s dishonour—is to enact the part of General Stephenson, an uncle of Clarissa’s, and to demand from Lovelace that he shall immediately marry the girl he has compromised; and, dressed in regimentals (very hastily procured for the occasion), the tragic farce is played, Clarissa consenting. Macshane is also now in borrowed plumes, as a minister of the Scotch Church; and so the girl is led to her doom, but not without a hope of escape, for she has appealed to Belford, who is deeply touched by her innocence and trust in him, and when he learns from Hettie, to whom Clarissa has spoken with womanly gentleness, that Lovelace was her betrayer, he determines to save the victim if it may yet be done. The third act, a remarkably strong and well- devised one, takes place in Lovelace’s handsomely- appointed house, which however, Clarissa believes to be a lodging procured for her by the “Ladies Bab and May Lawrence,” who are, of course, accomplices in the plot. They and some of Lovelace’s boon companions are drinking and jesting at the table when Lovelace and the false priest bring in the pretended bride, whose suspicions, however, are speedily awakened, to be confirmed when, the others having left the room, a servant prevents her from quitting the house, as in her terror she desires to do. Further confirmation of the evil stratagem reaches her by means of a letter fastened round a stone and flung into the window. The letter assures her that deliverance is at hand; and when Lovelace returns he finds her conscious of his treachery. Her prayer to him is that he will leave her till next day, and he pretends to acquiesce, but in fact sends drugged wine to her room by the faithful Jenny, who, however, suspects, and will not let it be drunk. At this moment Belford appears, bent on vengeance; but Lovelace’s drugs are more effective in his case, for he is persuaded to drink a fierce toast expressive of his hatred for his enemy, and is rendered helpless while endeavouring to snatch Clarissa from her fate. With Belford insensible on the ground, Lovelace is left alone with Clarissa. It is a pity that Mr. Buchanan wanders so much in the last act, the scene of which is a cottage at Hampstead. What he has to show is the death of Clarissa and also of Lovelace, but he begins with a scene for Hettie and an old woman, the purport of which might be more briefly given. Much that Hettie says is quite unnecessary, and Clarissa enters thrice in each case to do and say much the same things. Lovelace, called away to a duel with Belford, returns to die, after a reconciliation with Clarissa; but this act grows somewhat tedious, and author and manager may be advised to reconsider it.

There is much excellent acting in Clarissa. Miss Winifred Emery plays the heroine with simplicity and tenderness. One understands that her innocence might well have had an effect on such a man as Belford, who is not a very hardened sinner from the first. Miss Ella Banister, though lacking somewhat in experience, showed genuine earnestness and sincerity as Hettie, and Miss Collette made a bright little Jenny. Mr. Thorne has rarely been seen to such advantage as in the third act, during the scene with Lovelace. He acted with force and grip of the situation. His comedy as the quasi General Stephenson was also amusing, and the quiet determination of the last episode well fulfilled the idea of the reformed man, purified by contact with a good woman. Mr. Cyril Maude, only seen in the first act, gives a very clever and diverting study of Solmes. Mr. Thalberg, though a little deficient in power, acquitted himself on the whole very well indeed as Lovelace. Mr. F. Thorne gave character to Macshane, and his fellow rascals were well played by Messrs. Grove and Gillmore. The costumes are picturesque, the scenery is well painted. The play was most cordially received, and deserved its reception.

___

The Daily Telegraph (7 February, 1890 - p.3)

VAUDEVILLE THEATRE.

Tears once more have been shed in abundance over the sorrows of Clarissa Harlowe! Not even the beautiful Rose Chéri, when in the heyday of her success and loveliness, could have reddened eyes more effectively or caused such suppressed sobs as Miss Winifred Emery did yesterday afternoon when, “clothed in white samite, mystic, wonderful,” this “pure and stainless soul,” in the poetical phrase of Mr. Robert Buchanan, “triumphed over all possible physical corruption,” and rejecting “her betrayer’s proffered hand, rises above him to the sublimity of martyrdom.” Naturally opinions will differ about the new Clarissa. Men and women who do not care to be told the truth will shrug their shoulders at it; those who have a horror of sentiment will ridicule it; all but the blasé playgoers will applaud it; lovers of refined and imaginative acting will grow enthusiastic over the most beautiful type of pure English womanhood and piteous despair that the modern stage has seen since Miss Ellen Terry gave us Olivia; and as for the majority, whether they go to the theatre to have a good laugh or indulge in a good cry, they will probably be of the opinion of Jules Janin when he came away with red eyes from the first performance of the “Dame aux Camélias” and honestly owned, in answer to sneers about mock sentiment and doubtful morality, “Well, for my part I cried like a calf, and that is quite enough for me.”

Mr. Robert Buchanan’s new stage version of “Clarissa Harlowe” is probably the best that has been seen—more earnest, less artificial, and certainly better written than the hack melodramas that have hitherto dealt with Richardson’s sentimental heroine. Strange it is, but true, that it is to France we owe the structure and the dramatic grip which have made “Clarissa Harlowe” live upon the stage. On Aug. 5, 1846, was produced at the Gymnase “Clarissa Harlowe,” drame en trois actes, mêlé de chant, by Dumanoir, Clairville, and Guillard. Rose Chéri was the Clarissa, Bressant an ideal Lovelace, and Montdidier played Le Colonel Morden, who answers to the character of Philip Belford, entirely re-written in the new version, and acted yesterday with considerable success by Mr. Thomas Thorne. In those days it did not take long to pirate a French drama, and we find at the Princess’s Theatre, on Aug. 28, 1846, “Clarissa Harlowe,” a tragic drama, in three acts, by T. H. Lacy and John Courtney, which is in reality almost a literal translation of the French play, but without so much as a word of acknowledgment of the French authors. The cast is extremely interesting. Charles Mathews, of all men in the world, played Lovelace; Mrs. Stirling was Clarissa, and Mrs. Keeley the maid Lucy. Mr. Compton was in the cast, and so were Mr. Neville (Henry Neville’s father), Mr. Lacy Oxberry, and Miss Sala. Since then many have tried their hands on “Clarissa Harlowe,” notably Mr. Boucicault, who wrote it for Charles Coghlan and his sister, Rose Coghlan—an unfortunate combination which proved very distasteful in America—and very recently Mr. W. G. Wills, who doubtless found Richardson’s heroine as much to his poetic taste and fancy as the erring daughter of the Vicar of Wakefield.

Mr. Robert Buchanan tells his story in four acts. In the first we have the abduction of Clarissa from her country home by Lovelace and his dissolute London friends; in the second the repentance of the drunken Philip Belford, who discovers from his lost sister, Hetty, that he has sold poor Clarissa into the hands of her rakish destroyer; in the third the mock marriage in Lovelace’s town mansion by a Scotch scoundrel disguised as a parson, and the victory of Lovelace over the utterly defenceless girl; and lastly the pathetic death of Clarissa, which, as acted with infinite pathos and exquisite sensibility by Miss Winifred Emery, moved her sympathetic audience to abundant tears. Up to the last act Mr. Buchanan has given us a shapely and persuasive play. All his characters interest us, and are uniformly well written. The third act, the main credit of which Mr. Buchanan generously gives to the French authors, is not only interesting, but dramatic into the bargain. The defending sword of her champion Philip drops from his generous hands when the fumes of a drugged wine-cup render him insensible, and friends having departed and lights turned low, the sensual Lovelace lifts to his arms the fainting and prostrate Clarissa. Now, admirably written and beautifully acted as are the concluding scenes of Mr. Buchanan’s play, it is only here that any material alteration can be in candour suggested. It is immaterial that the last act is too long. We do not quarrel with it on the question of length, for Miss Emery’s death-scene is so finely imagined that the attention is riveted throughout by her plaintive pleading, and the eye delighted with the wondrous far-away expression that her face assumes. What we would ask Mr. Buchanan to consider is this—whether he does not build up a specious argument merely to knock it down again when he reunites Clarissa and Lovelace in their death embrace, and when, having “Christianised” and converted, as it were, the revengeful Philip, he makes him at once the avenger of his sister’s honour, but, at the same time, the murderer of the repentant Lovelace. Up to a certain point Mr. Buchanan’s noble argument in defence of all that is lovely and “half divine” in the character of woman is quite unanswerable. He himself says that the defiled Clarissa, by rejecting her betrayer’s hand inn marriage, “rises above him to the sublimity of martyrdom.” And so she might have done had he permitted her to die without desecrating her lips even in delirium with a kiss from the loathsome lips of Lovelace. She who has had a vision of eternity, whose face looks like one transfigured, whose voice is as of another world, talks convincingly of broken covenants and ruined sacraments, and what should she have to do with death embraces from a man she loathes, unpurified and unrepentant? That death reconciliation, that murmur in the last supreme moment of “wife” and “husband,” seem to traverse all which has gone before, and to destroy the very thing that the author advocates. Surely the French authors prepared for Mr. Buchanan not a bitter lesson but a more dramatic and convincing conclusion. To the piteous cry of Lovelace, “Clarissa! Grace! Grace!” comes the inevitable answer from such a woman half-way to heaven, “Mon Dieu, pardonnez moi! Pardonnez lui.” Clarissa, as Mr. Buchanan has described her to us, could do not more than that. A kiss from Lovelace in her death agony is a defilement. And, again, the duel between Lovelace and Philip seems harsh, repugnant, and unnecessary, anticipating as it does the death of Clarissa, who has in some mystic manner commended her faithful protector to the care of heaven. If Lovelace must die, let it not be at the feet, and almost in the arms, of the sweet woman he has outraged. His presence is hateful at such a moment; we do not desire to see his face at such a death. The French play is much finer and more dramatic. Clarissa is dead, Lovelace is prostrate with grief; and then someone taps him on the shoulder. He arises from his bewildering reverie and sees a man with a drawn sword. “Comte Robert Lovelace! je suis le Colonel Morden!”—and then the curtain falls. All is indefinite, undetermined, unexplained. The last act must be curtailed. Would that Mr. Buchanan could be persuaded to omit the reconciliation and the duel, for they spoil two beautiful characters, those of the loveable Philip Belford and the martyred Clarissa. With such an ending, this most interesting and poetical play can only be likened to “a broken blossom, a ruined rhyme.”

In no part of Miss Winifred Emery’s performance is there one jarring note. In the earlier scenes the actress is wholly in the manner of Richardson—sweet, modest, maidenly, and unobtrusive. In her most dramatic scenes the actress is entirely natural and never stagey. She arouses our interest at the outset, and at the conclusion touches the tenderest fibres of the heart by a method alike artistic and pathetic. Miss Emery realises what the author has described—that the dying Clarissa has had a heavenly vision of another world. Never did actress better realise by art and an intensely sympathetic nature that to Clarissa had been given the grace of an angel’s visiting. She held the house enthralled with a death scene whose very purity deprived it of all pain. It was a poem in action, and at its conclusion, whatever disappointment may have been caused by Clarissa’s death being too long delayed, the actress was greeted with an enthusiastic burst of applause, the sincerity of which was beyond doubt. Horrible, tragic, feverish, agonising death scenes there have been on the modern stage in plenty. Here was one illumined, refined, and spiritual. It will advance considerably the reputation of Miss Winifred Emery as an emotional actress. Never yet has Mr. Thomas Thorne had so strong a character as Philip Belford; never yet has he acted with such sincerity, intensity, and nervous force. He entered into the heart of the man, and understood him in his reckless pessimism, his careless debauchery, his revulsion of horror, his graceful repentance. The scene that ends the third act, when Philip is drugged and unable to draw his sword in defence of Clarissa, would tax the strength and ingenuity of a romantic actor. Mr. Thorne attacked it with surprising force, and was cheered and congratulated again and again. Mr. T. B. Thalberg, new comparatively to London, is both a promising and interesting young actor; but, at present, he has not quite experience or style enough for such a part as Lovelace. Without style a Lovelace is of little avail. We want the man and the manner, and Mr. Thalberg must cure himself of a deplorable habit of emphasising every unimportant word in almost every sentence. Conjunctions and prepositions are marked with force, whilst substantives, adjectives, and verbs are left to shift for themselves. And Miss Ella Bannister, who makes such a pretty and pathetic picture as the ruined Hetty Belford, will do well to look seriously after her elocution. She has genuine feeling, but she does not know how to express it. Half her words are inaudible and most of her sentences muffled. A very small character, that of Clarissa’s wealthy lover, old Mr. Solmes, was admirably played by Mr. Cyril Maude, and the audiences regretted the departure of this clever young actor, and amidst the contributory characters, Mr. Fred Thorne—the hedge parson—Miss Mary Collette, and a new-comer, Miss Florence Wemyss, were all excellent enough. The play, which was received without a dissentient voice, and with special calls for Mr. Buchanan, Miss Winifred Emery, and Mr. Thomas Thorne, is well dressed and effectively mounted. It will be strange if in this overflowing London, where so many are found to laugh over the eccentricity of farcical comedies, there are not many spectators who will enjoy a good play and weep over the sorrows of poor Clarissa Harlowe!

___

The Yorkshire Post (7 February, 1890 - p.4)

Mr. Robert Buchanan has achieved another brilliant success in his exploitation of the old novelists, our London Correspondent writes. His dramatic version of Clarissa Harlowe, which was produced at the Vaudeville yesterday, was received with distinct approval by a very critical audience, and it bids fair to have a not less prosperous career than Joseph’s Sweetheart. The dialogue is clear-cut, crisp, and sparkling, and the interest is not allowed to flag for a moment. There are also some very striking situations, which are the more effective as they are led up to in masterly fashion. But the chief charm of the play is that it preserves intact the spirit of Richardson’s work. The Lovelace of the play is the same dissipated libertine whose memory has been execrated by generations of gentle readers, and the Clarissa is the same virtuous maiden whose persecutions have excited their pity, while the whole surroundings of the piece inevitably suggest the novel. Perhaps in one or two of the scenes Mr. Buchanan will find it expedient to tone down his dialogue a little, or modify a situation, especially in the third act, where a detail here and there appeared to jar on the audience, but these are minor considerations. As a whole the piece is undoubtedly a remarkably strong one, and will prove a very acceptable addition to the theatrical attractions of the period—the more so as it is admirably acted and staged.

___

The Birmingham Daily Post (7 February, 1890 - p.4)

The long-promised version of Richardson’s “Clarissa Harlowe,” which has from time to time been postponed owing to the illness of Mr. Thomas Thorne and Mr. Robert Buchanan, saw the light this afternoon at the Vaudeville Theatre, when a large and very friendly audience gave it an extremely favourable reception. Mr. Buchanan has called his adaptation “Clarissa,” and has compressed the many dramatic incidents in the story into four acts. Great things had been expected of the play, and it may be said at once that anticipation has been very largely borne out. The subject is unusually sombre and mournful for Vaudeville audiences; but the London public have accepted “Man’s Shadow” and “La Tosca,” and there is no reason why a good play with a serious ending should not succeed. Certain it is that “Clarissa” contains some of the best dramatic work Mr. Buchanan has given to the stage, and the whole of the artists concerned in the production may be congratulated on a well-earned success. The first three acts move briskly enough, and are full of interest; but in the last act, which contains a lot of mawkish sentiment, there will have to be a considerable amount of compression. The great bulk of the work fell upon the shoulders of Miss Winifred Emery, who proved herself perfectly equal to the occasion, and who by a thoroughly artistic rendering added greatly to her already high reputation; indeed, her realistic and genuinely pathetic acting in the last act made one almost forget its artificiality. Next to Miss Emery the honours were carried off by Mr. T. B. Thalberg, who confirmed the good opinions formed of him when he appeared a little time back as Charles Surface. As the scoundrelly man of fashion, Lovelace, young Mr. Thalberg got through a very difficult task with complete satisfaction, his gentlemanly bearing and clearness of delivery being alike admirable. Mr. Thomas Thorne gave a very careful and highly-popular rendering of Philip Belford, and smaller characters were creditably filled by Mr. Frederick Thorne and Miss Mary Collette. Miss Ella Banister was hardly equal to the unpleasant part of Hetty Belford, but will probably improve after a few representations. Mr. Cyril Maude’s undoubted talents were completely thrown away on the part of Mr. Solmes. The first three acts were enthusiastically received, and, although the last scene fell a little flat, Mr. Robert Buchanan was warmly cheered at the close. No public announcement was made, but in all probability we shall soon see “Clarissa” finding its way into the evening bill at the Vaudeville.

___

The Daily Telegraph (8 February, 1890 - p.3)

“CLARISSA.”

TO THE EDITOR OF “THE DAILY TELEGRAPH.”

SIR—A dramatist should perhaps be silent when his work is greeted with such a consensus of eulogy as has been given to my new Vaudeville drama; but in your critic’s glowing and generous criticism there are two points of objection which I should like to explain, particularly as they affect the ethical quality of the entire play. Firstly, it is suggested that I traverse and undo my moral purpose when I allow the dying Lovelace to embrace the outraged girl and die at her feet. This would be absurd, after the previous scene of renunciation, but for the fact that Clarissa has, under the excitement of meeting her betrayer, lost her reason. Her mind goes back to her happy girlhood; the outrage is blotted from her memory; and she sees only an honoured lover leading her to the altar. The whole meaning of my last act is that physical violation and desecration cannot touch the stainless Soul; nor can that last kiss defile it, any more than the previous torture. It is important to remember that, in my play, Clarissa has from the first loved the man who wrecks her honour. Secondly, it is suggested that the reformed and “Christianised” Belford should not have been suffered to “kill” his enemy. In this connection due weight should be given to the morality of the period when the action takes place. Belford meets Lovelace in fair fight, as at that period even a just and good man might do. A modern Belford might possibly have renounced the duello on moral grounds, but my Belford lived one hundred years ago.

Thanking your critic for his sympathetic notice of a work on which I have spent no little thought and trouble, I am, your obedient servant,

ROBERT BUCHANAN.

Vaudeville Theatre, Feb. 7.

___

The Era (8 February, 1890)

“CLARISSA.”

_____

Mr Harlowe ... ... Mr HARBURY

Captain Harlowe ... Mr OSWALD YORKE

Mr Solmes ... ... Mr CYRIL MAUDE

Stokes ... ... Mr J. S. BLYTHE

Lovelace ... ... Mr T. B. THALBERG

Capt. Macshane ... Mr FRED THORNE

Sir Harry Tourville ... Mr F. GROVE

Aubrey ... ... Mr FRANK GILLMORE

Watchman ... ... Mr WHEATMAN

Richards ... ... Mr C. RAMSEY

Coffee-stall-keeper ... Mr BRAY

Drawer ... ... Mr AUSTIN

Philip Belford ... ... Mr THOMAS THORNE

Clarissa Harlowe ... Miss WINIFRED EMERY

Hetty Belford ... ... Miss ELLA BANISTER

Jenny ... ... Miss MARY COLLETTE

Mrs. Osborne ... ... Miss C. OWEN

Lady Bab Lawrence ... Miss L. BRYER

Lady May Lawrence ... Miss FLORENCE WEMYSS

Sally ... ... Miss LILY HANBURY

Have you ever read Richardson’s ‘Clarissa’? was a question often asked in the “intervals” on Thursday afternoon at the Vaudeville Theatre, where Mr Robert Buchanan’s dramatic version of the old bookseller’s immortal story was played for the first time. The answer in most cases was, “Yes; but a long time ago.” Mr Buchanan’s audience were thus in exactly the condition of mind to be wished for by the adaptor; not so firmly bound to preconceived ideas as to object to innovations, nor with such elevated and elaborate notions of the characters in Richardson’s “Clarissa” as to demand literal reproductions of them in Mr Buchanan’s. That gentleman has explained the course he has followed in his work in a note attached to the Vaudeville programme of Thursday afternoon. In the play of Clarissa, he says, “the same freedom of treatment has been adopted as in the author’s dramatic transcripts from Fielding, Sophia and Joseph’s Sweetheart. New incidents and new characters have been introduced, and while the spirit of the original has been preserved as far as possible, no attempt has been made to retain its letter. Free use has also been made, especially in act three, of the play on the same subject by MM. Dumanoir, Guillard, and Clairville, produced with extraordinary success at the Gymnase Theatre, Paris, in 1842. The leading episode, on which depends the whole motif of the story, has been in no particular tampered with in the present version.”

In the first act of the play we are in the vicinity of Clarissa Harlowe’s home. Lovelace, disguised as a peasant, is lurking about the place in order to get an interview with her, and is assisted in his schemes by a dairymaid named Jenny. Clarissa’s parents are determined that she shall marry an elderly gentleman named Solmes, whom she detests; and, between her hatred for the match and her instinctive distrust of Lovelace and his protestations, the inexperienced girl is sadly beset. By the assistance of his friends and hangers-on, Captain Macshane, Sir Harry Tourville, and Aubrey, Lovelace works upon Clarissa’s fears, and hurries her off to a carriage, which bears her away to London, where she arrives at an inn in Covent-garden in the early morning.

As Clarissa is still suspicious, Lovelace has to employ stratagem to gain his object; and to precipitate matters, bribes Philip Belford to impersonate an old relative whom Clarissa has never seen, and to insist on marriage taking place between her and her abductor at once. Whilst playing his part, Belford, who has been made a misogynist by the seduction of his sister Hetty by some person unknown to him, is so touched by the evident purity of Clarissa that he conceives a disgust for his dastardly task; and his resolve to save her is confirmed when he meets his sister, who tells him that the man for whom she left her home was Lovelace himself.

A sham marriage takes place at Lovelace’s London residence, where Clarissa discovers that she is being deceived, and, her suspicions being aroused, begs her pretended husband to allow her to leave the house. This he refuses to do, and finally induces her to retire to rest, sending her by Jenny, whom he has summoned to town to wait upon her, a draught craftily qualified with a strong opiate. Jenny discovers this trick, and prevents Clarissa from taking the drugged liquor. Belford comes to kill Lovelace for the seduction of Hetty, and calls up the friends of the libertine—who arrive to serenade him—to be witness of the retribution. Lovelace pours some of the opiate into a glass of wine, which Belford drinks. Clarissa comes down from her room, and endeavours to escape from the house. She almost succeeds in doing so with the assistance of Belford, but faints at the critical moment; and Philip, after a vain attempt to carry her out, falls, overcome by the drug, Clarissa, unconscious, being borne away by Lovelace in unholy triumph.

The last act is devoted to the death of the heroine and the punishment of her seducer, who is now desirous of marrying her, and who comes to the cottage near Hampstead Heath, where she is lying sick, to propose to what is vulgarly termed “make an honest woman of her.” Clarissa, whose loathing of her betrayer is intense, receives the proposal with noble scorn, and Lovelace is made to realise the gulf there is between him and her. Belford leads the repentant libertine away to a duel, in which Lovelace, in despair, allows himself to fall by his opponent’s sword, and comes in to die almost at the same time as Clarissa expires, returning in her delirium to the early days of her love, and fancying Lovelace is her true husband and that they have just been wedded.

The acting was good all round. Mr T. B. Thalberg, if he did not quite realise the arch-libertine of our imagination, proved equal to a very difficult task, and sustained a long and trying part with commendable staunchness to the painful end. Mr Harbury was solid and dignified as Mr Harlowe, and Mr Oswald Yorke enacted the brother of Clarissa with creditable care and energy. Mr Cyril Maude made a marked impression during the brief period of his appearance as the sanctimonious Mr Solmes, and Mr J. S. Blythe gave a respectable representation of Stokes, a farm bailiff. Mr Fred. Thorne’s Captain Macshane was a companion picture to his Welsh parson in Joseph’s Sweetheart, and his Scotch led- captain deserved the same hearty praise which we accorded to his previous effort. Mr F. Grove and Mr Frank Gillmore gave creditable expositions of the small rôles of Sir Harry Tourville and Aubrey, and Mr Wheatman spoke his few lines well as the watchman, other small parts being well played by Messrs C. Ramsay, Bray, and Austin. Mr Thomas Thorne in that of Philip Belford had a very sympathetic and thankful part, and made a decided hit in it. The awakening of repentance in Belford’s breast, and his desperate but unsuccessful effort to rescue Clarissa out of Lovelace’s clutches were watched with keen interest by the audience. Miss Winifred Emery deserves warm and unstinted praise for the manner in which she sustained the part of Clarissa. Her delicacy of physique and style well suited her to the character, and the exquisite refinement with which she endowed her creation, joined with the expressive grace of her acting to banish all ideas of bathos, and to enlist the sympathy of the audience. Her Clarissa Harlowe was an achievement of as much merit as difficulty. Miss Ella Banister’s demonstrative Hetty Belford was a useful contrast to the maidenly reposefulness of Miss Winifred Emery’s heroine; and Miss Mary Collette was appropriately simple and natural as Jenny. Miss C. Owen in the short part of Mrs Osborne was careful and distinct; and Miss L. Bryer and Miss Florence Wemyss suggested without too distinctly affirming the class to which the Ladies Bab and May Lawrence belonged. Miss Lily Hanbury was acceptable as the market girl Sally. With pretty scenery by Messrs Perkins and Hemsley, costumes by Nathan, furniture by Maple, and the charming serenade in the third act expressly composed by Mr Robert H. Lyon, Mr Buchanan’s last “adaptation from the English” had every accessory assistance to the success which it achieved on Thursday afternoon. The piece is by no means too long as it stands for an evening’s entertainment; but it would be a decided improvement if, without unduly curtailing its length, some of the didactic lines in the last act could be removed, and a superfluous line or two taken out here and there in the first and second. The curtain was twice raised on Thursday upon the company assembled on the stage, amidst whom, on a third time of asking, Mr Buchanan appeared, and bowed his acknowledgment of the plaudits of the audience.

___

The Dundee Advertiser (8 February, 1890 - p.5)

Mr Robert Buchanan, if he has not scored such a great success with his “Clarissa” as with “Sophia” and “Joseph’s Sweetheart,” has manufactured out of Richardson’s ponderous novel a very interesting though not a lively play. There is a tone of sadness throughout the piece, which is seldom relieved by humour, and then the humour is of speech, and not of situation. The public is accustomed to witness the triumph of virtue and the punishment of vice on the stage, but at the Vaudeville all this is reversed. Lovelace succeeds in enticing Clarissa from home, he succeeds in putting her under the protection of a couple of painted harridans in London, he succeeds in duping her by a false marriage, and finally drives her to the grave. The villain, it is true, is run through in the last act by the brother of a woman he has ruined, but the stroke of vengeance has nothing to do with the fate of Clarissa. Following Richardson, Mr Buchanan has made Clarissa refuse in her dying moments Lovelace’s offered atonement by marriage, thus keeping up to the end the depressing tone in which the play is started. The merits of the new drama are that it is well written, contains several strong situations, plenty of action, and is free from all ambiguity.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

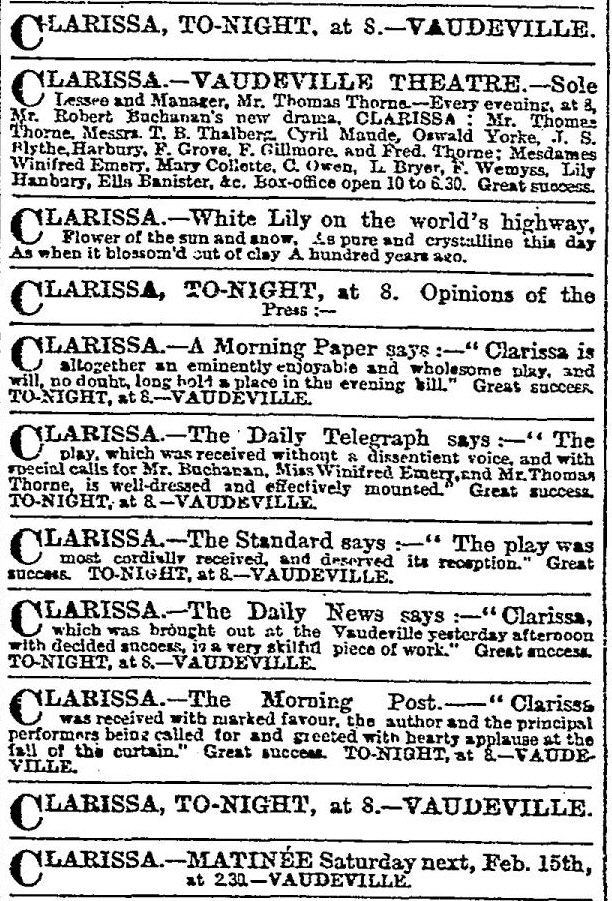

[Advert for Clarissa from The Times (8 February, 1890 - p.8).]

Lloyd’s Weekly London Newspaper (9 February, 1890 - p.5)

PUBLIC AMUSEMENTS.

_____

VAUDEVILLE THEATRE.

Thackeray wrote a novel without a hero, but it has been reserved for Mr. Buchanan to devise a play minus this important individual. Even he will not pretend that in Clarissa we have one male with any heroic qualifications. His chief personage, Lovelace, is a libertine of a very pronounced type, and his nearest approach to a man of honour is a drunken spendthrift, who preaches when he has lured a young girl to her ruin. Not that there are many fine points in the delineation of the latter character, but all the same, a middle-aged gentleman who washes his head in a trough in Covent-garden at sunrise is not a hero. Mr. Buchanan has drawn as much from a French play as from Richardson’s novel. His first three acts are quick and instinct with life, but in the fourth he is so anxious to moralise and seemingly to apologise for some of the free opinions of earlier scenes, that he descends to be dull and even dreary. The story is wholly occupied with the temptation of Clarissa Harlowe. She, poor girl, finding her parent firm in his determination to wed her against her will to a contemptible neighbour, listens to the suggestion of the handsome Richard Lovelace to fly with him and seek refuge with his relations. When first seen Lovelace is shorn of all his splendour, masquerading as a simple yokel in order to approach the woman he loves. He offers himself as the champion of beauty in distress. Clarissa accepts his aid as “a friend,” but once having got the girl to London, Lovelace is full of tricks and devices for her ruin. He foists on his credulous charge two very questionable ladies as relatives of his, and bribes a drunken man-about-town, Philip Belford, to enact the part of an unknown uncle of the girl. The latter’s part is to insist that a marriage with Lovelace is absolutely necessary, while knowing all the time that the marriage projected is only a mock ceremony. The drunkard’s remorse for urging a girl to her ruin, and his resolve to save her come too late. He breaks into the abode of Lovelace at the moment the mock marriage has been completed, but is drugged, and sinks helpless at the feet of the girl he would save. She falls in a dead faint, and the act closes on a scene of Lovelace gloating over the beautiful, senseless girl in the pale moonlight, while a serenade is heard without. In the last act Clarissa is in the retirement of a homely cottage at Hampstead, occupied by Philip Belford and his sister. She is sick of that illness which is of “the head and not the body.” Lovelace forces himself upon her loneliness to plead for forgiveness for the foul wrong he has done and to ask to be allowed to atone by making her his wife. The pure mind refuses his offer and she sinks and slowly dies. Lovelace, challenged to a duel by Belford, is mortally wounded, but struggles to the cottage and dies by the injured Clarissa. The scene is a strange mixture of bathos and pathos. In Philip Belford Mr. Thomas Thorne has fine opportunities for humour and sentiment. On Thursday afternoon we fancied him best in his comic side, though he played with real feeling in the more commanding situations. Mr. Thalberg was an earnest and effective Lovelace, and Miss Winifred Emery a tearful and winsome heroine. Her death scene was a wonderful piece of acting, and alone made the last act tolerable. Mr. Fred Thorne was very entertaining as a rascally Scotchman, a bumptious kind of individual who is everything by turns. A charming sketch of a somewhat naughty country lassie was given by Miss Mary Collette. The drama was warmly received, but this was in great measure due to the merit of the acting, particularly to the graceful and pathetic representation of Clarissa by Miss Emery. Mr. Thorne has placed the new play in his evening bill.

___

Reynolds’s Newspaper (9 February, 1890)

VAUDEVILLE THEATRE.

It may be safely affirmed that there are not many persons in the kingdom who have perused the unabridged edition of Samuel Richardson’s great work, “The History of Miss Clarissa Harlowe.” But an infinite number have read the sorrowful history of that young lady in a form less extensive than that which was acceptable to the belles of the last century, who had fewer distractions and more leisure. To those who have not even read the abridged edition, Mr. Robert Buchanan’s dramatic version of the book presented at this theatre on Thursday afternoon under the title of “Clarissa,” will prove highly attractive. Mr. Buchanan’s transcript is something more than a merely meritorious performance; it just falls short of being an exceptionally fine play. Richardson’s novel has been dramatized several times. It appears to have been first played at Paris in 1842, in a version for which several French playwrights were responsible. Four years afterwards it was produced in England, and recently Mr. W. G. Wills and Mr. Dion Boucicault have dramatized the work. Mr. Buchanan acknowledges his indebtedness to the French authors, especially in those parts of the play where they have departed most from the original. Clarissa Harlowe’s story is easily told. A young, beautiful, and virtuous country lady, in order to avoid marriage with Mr. Solmes, a mean, elderly man whom she loathes, is induced to flee from home by Richard Lovelace, a wealthy libertine, who promises to place her under the protection of some of his distinguished female relatives. Arrived in London, Lovelace goes through a mock marriage ceremony, and overcomes his victim. She, on discovering his fraud, retreats to a cottage at Hampstead, rejecting Lovelace’s repentant offers of marriage. Here she dies, and Lovelace is killed, according to the novel, in a duel with a friend of the family whose honour he has outraged, though here the Vaudeville presentation differs somewhat from the novel. Mr. Buchanan’s play is divided into four acts. The first is a country scene, the home which Clarissa is induced to abandon. In the second, we are taken to the Bell Tavern, Covent Garden, where the plot to inveigle the lady into a false marriage is concocted. The third act passes in Lovelace’s house, in which his infamous stipendiaries, of both sexes, have assembled to make merry over his pretended nuptials. Lastly, we have the cottage on Hampstead Heath, where Clarissa dies. After the first act, which—with the exception of the excellent acting of Mr. Cyril Maude, who made the small part of Mr. Solmes conspicuous—was a trifle tedious, the interest in the play developed remarkably. Clarissa, a very difficult part, was taken by Miss Winifred Emery, who throughout the piece gave unmistakable proof of the care with which she had studied, and at times rose to an expression of exceptional dramatic power. Lovelace was played with skill by Mr. T. B. Thalberg, of whom the only adverse criticism we feel called upon to make is that he should give us a little less effusiveness of posture and gesture, and beware of a provincial tendency to outdo nature in the commonplace matter of walking. One of the most conspicuous figures on the stage was Philip Belford, a reduced gentleman, who first aids in laying the trap into which Clarissa falls, and then befriends her. Mr. Thomas Thorne gave great force and intensity to this character. Captain Macshane, a Scotch hanger-on of Lovelace, was amusingly depicted by Mr. Frederick Thorne. More than a word of praise must be given to Miss Ella Banister for her touchingly natural characterization of Hetty Belford, especially as the outcast in the second scene, where we have a picturesque delineation of old Covent Garden Market, and the night life of the last century. Lovelace has ruined Hetty, and her brother brings about the final catastrophe by killing that audacious freeliver. In the third act, in a powerful scene, while Philip Belford, at the point of the sword, forbids Lovelace to enter the chamber of his assumed wife, a serenade is sung. The situation is trying and momentous. The serenade introduced here is not an inartistic artifice, but the result would be much more realistic if the song were half as short. The events were too exciting to be interrupted by a musical pause, unless very brief. A similar complaint must be made as to the dying scene in the last act. The spectator’s feelings are wrought up to a high tension. At the climax the curtain should drop, instead of which the scene is unduly prolonged, and the sympathy evoked has had time to cool. Had the curtain fallen a few minutes earlier, the close would have been infinitely more effective. Besides, it is quite inconsistent to have Clarissa expiring in the arms of a man whom she had repudiated in the most emphatic manner two or three minutes previously, and for whom all affection had died within her. In this scene Mr. Buchanan departs altogether from the original, and not with advantage. Richardson says of Lovelace’s last moments “He was delirious the two last hours, and several times cried out, as if he had seen some frightful spectre, ‘Take her away, take her away!’” The play was well mounted, and the costumes were superb. There was frequent applause, and both the actors and the author were called upon the stage.

___

The Referee (9 February, 1890 - p.3)

“Clarissa,” the latest adaptation to hand of Samuel Richardson’s once-famous and often-adapted story, “Clarissa Harlow,” appeared at the Vaudeville on Thursday afternoon after much preliminary paragraphing and several postponements. The new version is by Robert Buchanan. It proved to be a well-written and stirring piece—at least for three out of its four acts. The last act is, however, so sentimental and so full of stagy religion that the play, which had gone with a bang up till then, was at this point sorely imperilled. During “Clarissa’s” progress my eyes, like those of Mrs. Chick, were opened to at least two things. Firstly, that, although the free-and-equal-born and Huxley-hating Buchanan based two such powerful plays “Sophia” and “Joseph’s Sweetheart” upon works by Harry Fielding, Esq., blending with H. F.’s rollicking realism just the very touch of romantic love interest that is needed to make a true drama, he (B.) does not mix with the grave and reverend Richardson. Richardson and his latest adapter are both too sentimental, too aphoristic, too much given to what our great-grandmothers used to call “sensibility.” Secondly, it was borne in upon me more than ever that the public, who have so long neglected Richardson’s interminable stories, have very good reason for their neglect. Richardson’s screeds on morality and religion—of the whining sort, mark you—seem to me to be likely to do harm rather than good. All this sort of thing is used to excess in the Vaudeville last act, and moreover there is such a profusion of “My Gods!” “Great Gods!” and “O Gods!” that I suspect Buchanan must have meant to make “Clarissa” a Pantheistic play.

Long ago I enumerated to you several previous versions of “Clarissa Harlowe.” Some of them owed much to a drama prepared by Dumanoir, Clairville, and Guillard, produced at the Gymnase forty odd years ago, and quickly adapted for the Princess’s and the City of London, in Norton Folgate, with Mrs. Stirling and Mrs. R. Honner as the heroine respectively. Mr. Buchanan has not hesitated (as he frankly admits) to avail himself of this version. He, however, for the dissipated and afterwards repentant pander Macdonald (who keeps the same name and characteristics in Mr. Wills’s and other versions) uses Philip Belford, a person whose sister has been betrayed and deserted by Lovelace—though Belford is at first ignorant as to the name of the seducer. Buchanan has made other alterations, many of them improvements, and altogether his play tells the famous story of the abduction and seduction of the perplexed and proudly pure Clarissa by the champion insinuating debauchee Lovelace in a highly interesting and often moving manner. His third act, where Belford, who (like Macdonald) had previously assumed a disguise in order to promote Lovelace’s mock-marriage with Clarissa, and anon comes to rescue Clarissa and to avenge his own sister’s dishonour, is very powerful. Also the situation where, after many struggles, Clarissa and her would-be friend are both drugged, and the poor caged girl lies helpless in the villain’s arms, while Belford drops his sword and falls apparently lifeless, wrought the audience to a high state of enthusiasm. But, alas, alas, the last act! O that act! It came like a wet blanket on all the previous enthusiasm, and unless something is done to lighten it, it will undoubtedly handicap the chances of “Clarissa’s” financial success. Just you fancy the heroine, now heartbroken, and in a long white nightgown, wandering about the stage, giving off sermons, which profess to show an intimate acquaintance with all the arrangements in a future life, and purifying and absolving Belford as though she were a very high priestess. She speedily converts the broken-hearted Belford to Christianity. “I claim your life for God!” says she. Whereupon Belford, being converted, and it being a fine day, immediately goes out to kill a man—Lovelace, to wit—whom he stabs in a duel—not shoots him, as in previous versions. Then Clarissa, who has just disdainfully refused the now remorseful Lovelace’s offer of real marriage, dies in a big armchair, embracing her betrayer, who has just tumbled in to die at her feet.

As Clarissa, Miss Winifred Emery played with more charm and intensity than she has previously shown. At times her pathos was thrilling in the extreme. Thomas Thorne, as the sometime dissipated Belford, was also stronger i’ the pathetic vein than I have ever seen him, especially in the scene where he, then on villainy bent, is moved to tears and aroused to manhood by the trustful pleading of poor Clarissa. Thorne, however, or somebody in the piece, should have more of the comedy element by way of relief. Mr. T. B. Thalberg started by being somewhat ill at ease and jarring as Lovelace, but anon he warmed to his work, and, in spite of occasional crudity, was often strong without rage. There is something in Thalberg’s manner which gives me great hopes of him. F. Thorne was good as the low Scotch cur Macshane. Mr. Harbury, however, was but a penny-plain-and-twopence-coloured kind of Mr. Harlowe. Miss Ella Bannister was sadly over-weighted as the outcast sister—a very Surrey-side character—and Cyril Maude was utterly wasted on the small part of old Solmes, who only appears in one act for a few minutes.

“Clarissa” went into the Vaudeville bill to-night (Saturday). Next Saturday there will be a matinée of the new piece.

___

The Sheffield and Rotherham Independent (10 February, 1890 - p.5)

ABOUT PLAYS AND PLAYERS.

_____

In preparing “Clarissa,” which was successfully produced at the Vaudeville Theatre on Thursday afternoon, and has promptly taken its place in the evening programme, Mr. Robert Buchanan has relied more on a French dramatist’s work than on Richardson’s tedious novel, and more on his own dramatic instinct than upon either. Consequently we have a sound piece of workmanship; very gloomy, a trifle too preachy in parts, and not quite so artistically complete as an illustration of unsullied martyrdom as the author intends and imagines it to be; but an interesting drama of solid merit, nevertheless. I had made a futile attempt to wade through Richardson’s eight volumes in order to brace myself for the ordeal, and it was a welcome relief to find that whereas Miss Winifred Emery is fitted with a part which enables her to delineate the persecuted heroine with a fine, affecting strain of loving and suffering humanity, the author has rejected most of the dross while welding the pure gold into comely shape.

Miss Emery realises the idea of embodied purity—a purity of soul which rises superior to the physical outrage of her libertine lover. Shortly before her protracted death scene she exclaims: “I leave to earth the form by man polluted; my soul I leave to God.” Difficult and delicate as is the task of pourtraying such a character and enforcing such a moral, the author and the actress between them have well earned the merit of strong though subtle achievement. It seems to me that the play should have ended sadly but sweetly, as with the cadence of the dying swan’s last melancholy note. But after Clarissa has taken pathetic leave of the world where she was so cruelly treated, and thrilled us to furtive tears by a dying dream of wondrous tenderness, the picture is marred by the intrusion of the wounded Lovelace, and by the final kiss of conciliation, out of harmony with the spiritual fading away from earth and its grossness.

To intrude the coarse episode of Lovelace’s duel and death not only blurs the picture but suggests that we have had our finer feelings harrowed and been led away into unaccustomed paths of virtuous sentiment, by a set of characters who are but artificial puppets. It sets us thinking that, after all, Lovelace’s folly was as stupendous as his wickedness, and his reckless rascality an almost impossible quality. Why should he profane the sacred name of honour, commit himself to horrid blasphemy, and run risks which ordinary prudence could so easily avoid, merely to unlawfully and forcibly “possess” a beautiful and sweet-minded young heiress, who was willing to marry him, who would have been a treasure worth any man’s winning, and whom he loved as well as it was in his nature to love anything? And why could not Mr. Robert Buchanan let us go home in a melting mood of tenderness, instead of stirring up the instincts of querulous criticism by an ending which strikes us as needlessly materialistic and almost profane?

To show that it is the perverse author and not the captious critic who has blurred the fair portrait with this film of misplaced materialism let me print a couple of the verses which Mr. Buchanan circulated as embodying his conception of “Clarissa:”

Symbol of Pureness, to this hour

So frail and yet so strong—

With Death more sweet than life for dower,

Conquering by gentleness, not power,

A world of lust and wrong.

Bruis’d in the hand of man, which fain

Would crush it or control,

The chastity without a stain

Still dying ever lives again,

Type of the woman soul!

I prefer to postpone criticism of the acting generally until another opportunity, though in justice it should be said that the play is admirably staged, and that the first performance went with a smoothness highly creditable to all concerned. Mr. Thomas Thorne has found a notable opportunity of clenching his reputation as a strong character actor. As Belford, the broken gentleman, who from being a dissolute tool of the hero, becomes the only friend of Clarissa and her avenger, after learning that his own sister owed her moral downfall to the licentious Lovelace, Mr. Thorne faces difficulties only to conquer them, and becomes the most imposing figure in the most striking situations in the play. Dissolute recklessness, repentance, remorse, and a profound pity for the betrayed which leads inexorably up to the destruction of the betrayer—all these are depicted with an intensity which is impressive and sometimes enthralling, without being boisterous. The play had a very sympathetic and encouraging reception; the chief performers were recalled after each of the four acts, and at the finish they appeared with the author, in response to a very hearty call.

___

Local Government Gazette (13 February, 1890)

Mr. Robert Buchanan and Mr. W. G. Wills have recently dramatised the French “Clarissa,” which has been readapted to the English stage more than once, and the former author’s version was on Thursday afternoon brought out at the Vaudeville, under circumstances of the most promising character. Indeed, the story as handled by Mr. Robert Buchanan and the Vaudeville company, more psrticularly by Miss Winifred Emery in the part of the martyred heroine, is not unlikely to attain the vogue of the old Gymnase play, which, of course, the adapter has carefully studied.

* * *

“Clarissa Harlowe” is a painful story from the beginning, and has to be conducted to an appropriate conclusion, without regard to that dramatic bugbear, and unhappy ending. As a pure-souled martyr to the “polluting hand of man,” Clarissa must be exhibited by author and actress both in a singularly angelic light; the tyranny which drives her forth from the paternal roof must be odious in the extreme, and all the measures resorted to by her abductor in order to compass her ruin must be correspondingly heartless. By such means alone can the public be brought to acquiesce in the apotheosis of a young lady who, prosaically speaking, only meets with the fate of the common and generally unregarded female “outcast” of melodrama. Mr. Buchanan has very skilfully done his work in this respect, and from Miss Winifred Emery he has received invaluable assistance. Upon the representative of the hapless Clarissa the whole sympathetic interest of the story depends; her virginal air and sweetness count for quite as much as the constructive art of the adapter, and, failing such adventitious aids, the play would be in imminent danger of falling to pieces. Miss Emery in this part is a worthy successor to the fascinating and talented Rose Chéri.

* * *

The changes now imported into the story relate chiefly to the manner in which the death or expiation of Lovelace is brought about. In the French play the avenger was Clarissa’s uncle; in the novel he is her cousin. Mr. Buchanan, on the other hand, magnifies the character of Lovelace’s disreputable henchman, Philip Belford, and transforms him into the libertine’s executioner on the ground that his sister, like Clarissa, has also been betrayed. By this device a congenial and important part is provided for Mr. Thomas Thorne. Lovelace finds in Mr. Thalberg a very spirited and plausible representative. Some picturesque types are scattered over a not too numerous cast. Among these may be mentioned the Mr. Solmes of Mr. Cyril Maude, the old and decrepit suitor who is thrust upon Clarissa by her father and the Captain Macshane of Mr. Frederick Thorne. Of the former, as well as of Clarissa’s father, who is forcibly played by Mr. Harbury, we unfortunately get but a glimpse. “Clarissa” is altogether an eminently enjoyable and wholesome play.

___

The Stage (14 February, 1890 - p.10)

LONDON THEATRES.

THE VAUDEVILLE.

On Thursday afternoon, February 6, 1890, was produced here a new four-act drama, by Robert Buchanan, founded on Richardson’s novel, entitled:—

Clarissa.

Mr. Harlowe ... ... Mr. Harbury

Captain Harlowe ... Mr. Oswald Yorke

Mr Solmes ... ... Mr. Cyril Maude

Stokes ... ... Mr. J. S. Blythe

Lovelace ... ... Mr. T. B. Thalberg

Capt. Macshane ... Mr. Fred Thorne

Sir Harry Tourville ... Mr. F. Grove

Aubrey ... ... Mr. Frank Gillmore

Watchman ... ... Mr. Wheatman

Richards ... ... Mr. C. Ramsey

Coffee-stall-keeper ... Mr. Bray

Drawer ... ... Mr. Austin

Philip Belford ... ... Mr. Thomas Thorne

Clarissa Harlowe ... Miss Winifred Emery

Hetty Belford ... ... Miss Ella Banister

Jenny ... ... Miss Mary Collette

Mrs. Osborne ... ... Miss C. Owen

Lady Bab Lawrence ... Miss L. Bryer

Lady May Lawrence ... Miss Florence Wemyss

Sally ... ... Miss Lily Hanbury