ROBERT WILLIAMS BUCHANAN (1841 - 1901)

|

ROBERT WILLIAMS BUCHANAN (1841 - 1901) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

PATIENCE

The following three items concern the Gilbert and Sullivan operetta, Patience, and the possible models for the two poets, Reginald Bunthorne and Archibald Grosvenor. Having now suf..., sorry, watched Patience, I have to say I think the evidence that Robert Buchanan was the inspiration for Archibald Grosvenor is sketchy, to say the least. That Bunthorne was based on Swinburne seems quite likely, and perhaps the ‘Fleshly School’ controversy might have provided the initial spark for the idea of a dispute between a pair of poets, but that’s about as far as I’d take it. Of course, I’ve only seen one interpretation of Patience and I suppose you could have a more Buchanan-like Archibald Grosvenor, if the director wanted to go down that path, but from all the various illustrations I’ve seen or the other productions available on youtube I’ve had a quick glance at, the two poets seem to be pretty much the same, and ‘aesthetic poets’ in general seem to be the butt of the joke. ___

1. ‘In Search of Archibald Grosvenor: A New Look at Gilbert’s Patience’ by John B. Jones 2. ‘Swinburne, Robert Buchanan, and W. S. Gilbert: The Pain That Was All but a Pleasure’ by William D. Jenkins 3. Mr. Gilbert and Dr. Bowdler: A Further Note on Patience’ by John Bush Jones ___

‘In Search of Archibald Grosvenor: A New Look at Gilbert’s Patience’ by John B. Jones

In Search of Archibald Grosvenor: JOHN B. JONES

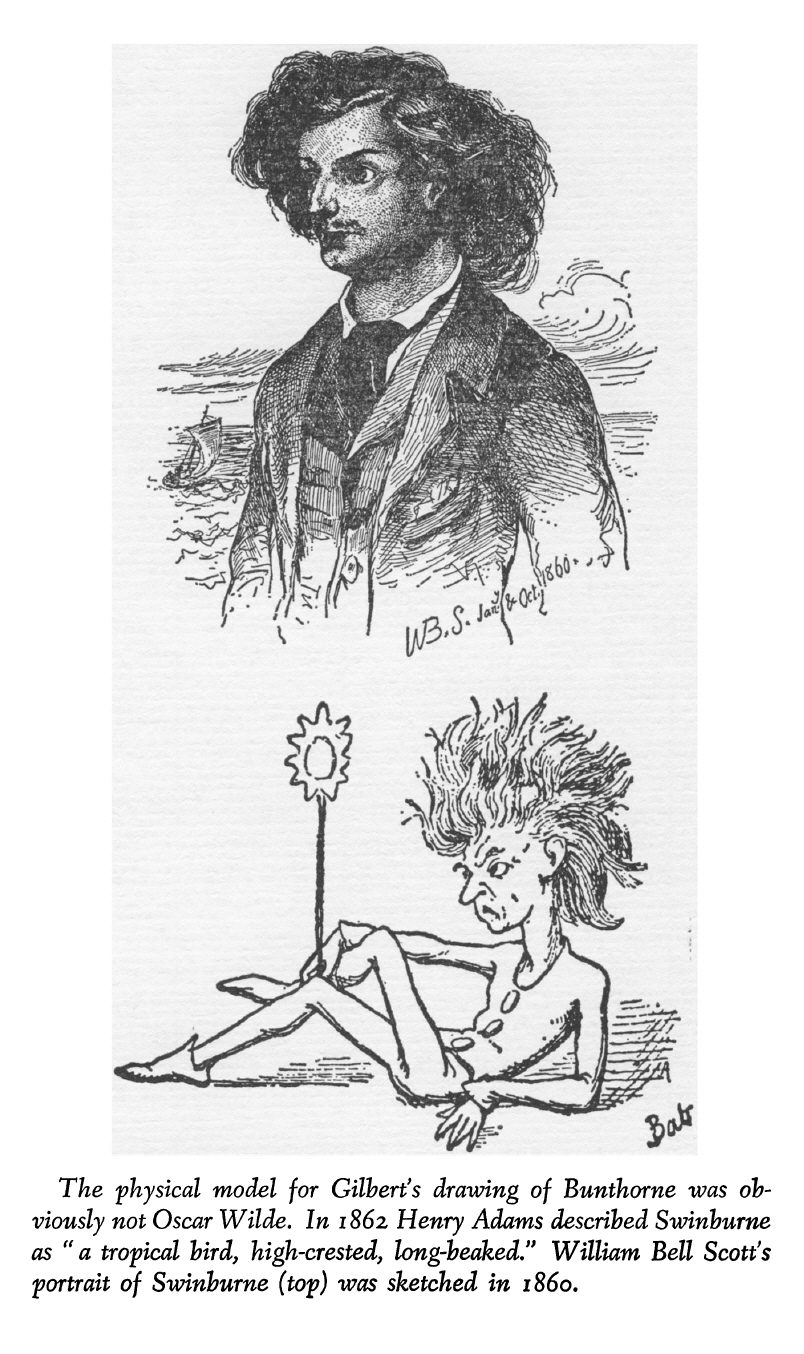

EVER SINCE an anonymous first-night critic attempted to equate Archibald Grosvenor with Algernon Swinburne eighty-four years ago,1 scholars, critics, and assorted devotees of Gilbert and Sullivan have tried their hand at identifying the prototypes of the two rival poets in Patience. Most of the attention has been given to Reginald Bunthorne, and, amidst some rather wild and haphazard guesses, a few sound theories have been put forth. Most of the earlier writers on the subject favored an equation of Grosvenor with Swinburne and Bunthorne with Oscar Wilde.2 It was not until a decade ago that Leslie Baily and Audrey Williamson (independently, it appears) offered more satisfactory suggestions, suggestions which need little additional support in order to establish a fairly positive identification for the prototype of Bunthorne.3 However, neither Mr. Baily nor Miss Williamson hazards a guess at the identity of a model for Grosvenor, the latter finally despairing of the fact that Grosvenor’s poems “can hardly be conceived as the parody of any known writer of the day.”4 It is my present purpose to add a few new bits of evidence in support of Miss Williamson’s identification of Bunthorne and to suggest possible prototypes for Grosvenor which I believe to be not only plausible, but accurate, not only consistent with the satiric intent of Patience, but also instrumental in adding a new dimension to that satire. _____ 1 “An Aesthetic Opera” (anon, rev.) London Times, April 25, 1881, p. 10. _____ 46 component both of Bunthorne’s poems and personality is Algernon Swinburne. While carefully comparing evidence from Patience with the careers of these men, Miss Williamson stops short of examining the poetry itself. She only remarks in passing that “Bunthorne’s literary style, as exemplified in his recited poetry and conversation, is without doubt the parody of a particular literary style, not (like the language of the girls) just a general reflection of the aesthetic jargon.”5 A look at the poetry, I believe, will add even further weight to Swinburne’s dominant position in the character of Bunthorne. Yet though all this be thus, When from the poet’s plinth _____ 5 Ibid. pp. 83-84. _____ 47 How can he hymn her throes It is partly the meter, but, more important, the “verbal tricks” and inverted repetition of ideas in such a poem as Swinburne’s “Satia Te Sanguine” that are echoed in Bunthorne’s “Heart Foam”: I wish you were dead, my dear; Oh, to be wafted away Swinburne’s heavy use of alliteration is mimicked in such lines as, What time the poet hath hymned in a way similar to his own anonymous self-parody of 1880, “Nephelidia”: From the depth of the dreamy decline of These literary parallels concur in every respect with Miss Williamson’s arguments to make Swinburne the most likely candidate for the primary, though not sole, source of the person and poetry of Reginald Bunthorne. _____ 8 William Schwenck Gilbert, Patience, in Selected Operas, First Series (London: MacMillan, 1956), p. 33. This edition of Gilbert’s comic operas, no better or worse than any other readily available edition, does not number the lines. Future references to Patience are incorporated in the text by page reference to this edition. _____ 48 “Fleshly,” it does not immediately suggest a generic identification with a particular school or group of poets. “Idyllic” suggests, rather, a type of poetic composition—more or less simple, romantic narrative verse often depicting peace, happiness, and contentment. Tennyson’s Idylls of the King comes first to mind, but the Poet Laureate may be summarily dismissed as the object of Gilbert’s satire since none of Grosvenor’s characteristics jibe with the popular impression of Tennyson. Besides, in spoofing Tennyson’s The Princess in 1870, Gilbert carefully called his play “A Respectful Perversion”; there is nothing respectful about the treatment of contemporary poets in Grosvenor. I cannot ease the burden of your fears, Grosvenor’s other similarities to Morris begin with his general physical appearance. In contrast to the diminutive George Grossmith’s portrayal of Bunthorne in the original production of Patience (Swinburne was a small, odd-looking individual), the handsome and stocky Rutland Barrington was cast as Grosvenor. William Morris was known generally as a strikingly handsome man “rather below the middle height, deep-chested and powerfully made, with a head of singular beauty.”12 At one point in the second act of Patience, Bunthorne declares that he will make Grosvenor “cut his curly hair” (p. 60). A glance at photographs of Morris in any of the many biographies—not to mention the outlandishly exaggerated hair in contemporary _____ 11 The Earthly Paradise, “An Apology,” II. 2-5. _____ 49 caricatures—reveals wildly curly locks to be a predominant physical feature of Morris. I may say at once. I’m a man of propertee— Though Morris did not found the Socialist League until 1884, he was already treasurer of the National Liberal League and had proclaimed his socialistic views in the lectures mentioned earlier and in the Manifesto to the Working Men of England in 1877. It may be assumed fairly safely that these views were known widely enough to allow for a sly dig in a theatrical performance. I also feel that Morris’ socialism as a referent helps to make clear the rather befuddling contrast between Grosvenor’s apparent wealth and hatred of money. ___ 13 Quoted in Victorian Poets and Poetics, ed. Walter E. Houghton and G. Robert Stange (Boston, 1959), pp. 583-584. _____ 50 on the bliss of domestic and marital love. In the first few editions of the former poem, the several sections were designated “Idyl I,” “Idyl II,” and so forth, although in the later editions they were labelled cantos. That these poems, which Frederic Harrison referred to as “goody-goody dribble,”14 were still familiar enough for public satire in the 1880’s is evidenced by Swinburne’s parody “The Person in the House,” appearing in his anonymous Heptalogia the year before the production of Patience. The popularity of Patmore is further attested to by the fact that between the first edition of 1854 and 1896, the year of the poet’s death, an estimated quarter million copies of The Angel in the House were sold, not counting the popular edition of 1887.15 Patmore’s popularity and peculiar brand of poetry, then, would have made him an easy target for theatrical satire, and his narrative verse and incessant theme of marital joy strongly suggest him as a model for the “idyllic” Grosvenor. _____ 14 Quoted in J. C. Reid, The Mind and Art of Coventry Patmore (London, 1957), p. 3. _____ 51 and almost clerically mild and moral poet as it would have to the clergyman of the original draft. Taken as an aspect of the popular notion of Patmore’s character, then, “canonical” may be viewed as an integral part of the literary satire of Patience rather than as an anomalous leftover from Gilbert’s original plan for the play. There was a lord that hight Maltete, Gentle Jane was good as gold, However, in homely diction and mundane subject matter, Grosvenor’s poems more closely approximate the domestic verse of Patmore: I hope you’re well, I write to say He punched his poor little sisters’ heads, Finally, Patmore’s constant reiteration of the rewards of virtue and the bliss of marriage is echoed in Grosvenor’s _____ 20 “The God of the Poor,” in The Collected Works of William Morris, ed. May Morris (London, 1910), IX, 157. _____ 52 And when she grew up she was given in marriage The Patmore-like morality of these lines about a very good girl Grosvenor declares is not “calculated to bring the blush of shame to the cheek of modesty” (p. 53). An every-day young man: When Grosvenor appears at the end in his business suit and bowler, he is the living picture of the middle-class, un-aesthetic, Philistine taste that his poetry had expressed all along. His aesthetic pretensions are broken down completely, his true “anti-culture” nature is 53 revealed, and—by extension—Gilbert has taken his final swipe at the Philistines with as much vigor as he had earlier bludgeoned the aesthetes. Northwestern University ___

‘Swinburne, Robert Buchanan, and W. S. Gilbert: The Pain That Was All but a Pleasure’ by William D. Jenkins

Swinburne, Robert Buchanan, and W. S. Gilbert: WILLIAM D. JENKINS

THE middle-aged spinster as an object of ridicule in the Gilbert and Sullivan operas has been the subject of much inconclusive controversy. Many commentators have interpreted Gilbert’s frequent use of the “old maid” joke as indicating a streak of cruelty in his character; the word “sadism” has been specifically applied.1 However, at the very worst, Gilbert was only mocking a recognizable type of woman. Apparently no one has charged Gilbert with using a living individual as a model for Ruth, Lady Jane, or Katisha. _____ 1 Leslie Baily, The Gilbert & Sullivan Book (London, I966), p. 2I8, cites various comments. _____ 370 years old, just down from Oxford, and his private life had not yet become a public scandal. So much could not be said for another literary figure of the day. Persistent emphasis, over a period of eight decades, on the harmless mockery of Wilde has minimized recognition of the more subtle witticisms directed at a much greater and more vulnerable man—Algernon Charles Swinburne. Although several commentators on Patience have mentioned Swinburne’s name in passing, it seems that only three, Frances Winwar,2 Audrey Williamson,3 and John B. Jones,4 have emphasized Swinburne as the primary figure in the composite of Victorian aesthetes that constitutes the “Fleshly Poet,” Reginald Bunthorne. _____ 2 Frances Winwar, Oscar Wilde and the Yellow Nineties (New York, 1940), p. 60. _____ |

|

|

372 detailed account of the earliest known extant draft, a fragment of Act I, deposited in the British Museum. Miss Stedman points out that “at this stage the rival poets of the final version are still the competitive clergymen whom Gilbert borrowed from his own Bab Ballad, ‘The Rival Curates.’” 5 However, Miss Stedman also notes that the identity of the leading characters in Patience “seesawed between the Grosvenor Gallery and the Anglican church for some six months. Gilbert’s original intention seems to have been to make aesthetes of Bunthorne and Grosvenor (long before these names had been settled upon).” Like other commentators, Miss Stedman cites part of a letter (November 1, 1880) from Gilbert to Sullivan: “I mistrust the clerical element. I feel hampered by the restrictions . . . and I want to revert to my old idea of a rivalry between two aesthetic fanatics . . . instead of a couple of clergymen.” _____ 5 Jane W. Stedman, “The Genesis of Patience,” Modern Philology, LXVI (1968-9), 48-58. _____ 373 Whatever the “popular impression” may have been, Gilbert, apparently, was not greatly concerned with it when he wrote Lawn Tennison into his early draft. I suggest further, that Gilbert was no more concerned with consistency in creating his rival aesthetic fanatics. Thus Williamson finds a touch of Morris in Bunthorne, Jones finds a touch of Morris in Grosvenor; both are probably correct. Isaac Goldberg finds a touch of Swinburne in Grosvenor;7 the slight evidence for this view does not negate the primary Bunthorne-Swinburne identification. I am so old-fashioned as to believe that the test whether a story is fit to be presented to an audience in which there are many young ladies, is whether the details of that story can be decently told at (say) a dinner party at which a number of ladies and gentlemen are present.10 _____ 7 Isaac Goldberg, The Story of Gilbert and Sullivan (New York, 1928), p. 261. _____ 374 This attitude is decidedly different from that expressed by Swinburne in an 1866 essay, “Notes on Poems and Reviews,” which contributed to the Fleshly Controversy: Who has not heard it asked, in a final and triumphant tone, whether this book or that can be read aloud by her mother to a young girl? whether such and such a picture can properly be exposed to the eyes of young persons? If you reply that this is nothing to the point, you fall at once into the ranks of the immoral.11 Perhaps Gilbert did protest his purity too much. However, his precept was not violated in Patience. The joke about Swinburne’s sexual deviation is not only “too French,” it is told in a language that “the young lady in the dress circle” did not understand; she was not sophisticated enough to be shocked. Perhaps Gilbert could not resist the opportunity of applying his unique topsy-turvy logic. Was it a case of letting “the punishment fit the crime”? Or was it rather, since it is not cruelty to be cruel to a masochist, “a most ingenious paradox”? I hear the soft note of the echoing voice _____ 11 Swinburne Replies, ed. Clyde Kenneth Hyder (Syracuse, 1966), pp. 29-30. _____ 375 And never, oh never, this heart will range Yes, the pain that is all but a pleasure will change The linkage of pleasure and pain in Swinburne’s poetry scarcely needs comment. It is especially notable in “Rococo,” a poem about dead love, which may have been the model for Gilbert’s parody. Here is Swinburne’s third stanza: Time found our tired love sleeping, The concluding two lines of half the stanzas of this ten-stanza poem refer to pleasure and pain. Equally characteristic of Swinburne is the structure of Gilbert’s lines: “The pain that is all but a pleasure . . . the pleasure that’s all but pain.” Such repetition, but inversion, of the key words has been called by Cecil Y. Lang, “the purest Swinburnese—‘simple perfection of perfect simplicity.’13 PA. I only ask that you will leave me and never renew the subject. “Oh, to be wafted away It is a little thing of my own. I call it “Heart Foam.” I shall not publish it. _____ 12 Swinburne, Poems and Ballads, First Series (London, 1866). All the poems herein suggested as models for Gilbert’s parodies are from this collection. _____ 376 Gilbert seems to have crammed several Swinburnean references into the four lines of “Heart Foam,” including the repetition-inversion of “dust” and “earth.” Additionally, there is a close resemblance to “The Garden of Proserpine,” described by Swinburne in “Notes on Poems and Reviews” as expressing “that brief total pause of passion and thought, when the spirit, without fear or hope of good things or evil, hungers and thirsts only after perfect sleep.”14 Stanza ten reads: We are not sure of sorrow, Bunthorne as the rejected poet and lover suggests “A Leave-taking,” wherein Swinburne plays a similar role: “Let us go hence, my songs; she will not hear . . . . Let us go seaward as the great winds go, / Full of blown sand and foam.” The seemingly meaningless title, “Heart Foam,” is perhaps explained by Swinburne’s fondness for the word “foam,” notable even in a poet who loved sea imagery. Thus the bitterly hostile Buchanan commented: “I attempt to describe Mr. Swinburne; . . . men and women wrench, wriggle and foam in an endless alliteration.”15 Whether the point deserves criticism is immaterial; the fact is readily documented. The disappointed lover “foams” frequently in “The Triumph of Time”; in “We have seen thee, O Love”; in “Rococo”; and in “Dolores” no fewer than eight times, e. g., “By the lips inter-twisted and bitten / Till the foam has a savour of blood.” What time the poet hath hymned _____ 14 Swinburne Replies, p. 24. _____ 377 Quivering on amaranthine asphodel, (Hollow) Thou wert fair in the fearless old fashion, Is it, and can it be, For many loves are good to see; The “Hollow” title, and the flowers that “are only uncompounded pills” in Bunthorne’s second stanza, may derive remotely from “The Garden of Proserpine”: “Where summer song rings hollow / And flowers are put to scorn.” Patience’s confusion of the alliterative “Hollow! Hollow! Hollow!” with “a hunting song,” perhaps hints at “a hymn from the hunt that has harried the kennel of kings,” the concluding line of Swinburne’s self-parody, “Nephelidia,” published in The Heptalogia, 1880. In November of that year Gilbert completed the libretto of Patience. Although The Heptalogia was published anonymously, it seems probable that Gilbert knew the identity of the author and admired the wit of a fellow-parodist.16 Bunthorne confesses: “There is more innocent fun within me than a casual spectator would imagine.” Note the names of the humorous weekly, Fun, for which Gilbert had written his Bab Ballads, and the literary journal, the Spectator, which was strongly anti-Swinburne _____ 16 Swinburne and Gilbert had the same book publishers, John Camden Hotten, and his successor, Andrew Chatto, who published The Heptalogia. Gilbert could hardly fail to recognize “Nephelidia” as a parody of Swinburne’s style. Did he also recognize the allusive content of the concluding line? (Atalanta in Calydon: “Amid the king’s hounds and the hunting men,” etc.) _____ 378 on moral grounds and which figured in the Fleshly Controversy.17 Thus with English versifiers now, the idyllic form is alone in fashion. . . . We have idyls good and bad, ugly and pretty, idyls of the farm and the mill; idyls of the dining room and the deanery; idyls of the gutter and gibbet.”18 Buchanan, author of a volume of verse entitled Idyls and Legends of Inverburn, interpreted Swinburne’s anti-idylism as a direct affront. The animosity smouldered until 187I, when it flared into white heat with publication in the Contemporary Review of a critical article, “The Fleshly School of Poetry.” Using the pseudonym “Thomas Maitland,” the mean-spirited Buchanan attacked Swinburne and D. G. Rossetti for the immoral sexuality of their poetry. Buchanan criticized Rossetti’s rhyming technique; “accenting the last syllable in words which in ordinary speech are accented on the penultimate . . . ‘Between the lips of Love-Lilee.’” (Bunthorne: “I shall have to be contented with a tulip or lily!”) Swinburne was chastised as “only a mad little boy letting off squibs . . . . ‘I will be naughty!’ screamed the little boy.”19 Finally, Buchanan noted Swinburne’s “foaming” (“Heart Foam,” above). _____ 17 John A. Cassidy, Algernon C. Swinburne (New York, 1964), pp. 128-44, gives a detailed account of the Fleshly Controversy. _____ 379 the Microscope, 1872, Swinburne recalled his “Notes on Poems and Reviews” of 1866: From a slight passing mention of ‘idyls of the gutter and gibbet’ in a passage referring to the idyllic schools of our day, Mr. Buchanan . . . is led even by so much notice as this to infer that his work must be to the writer an object of special attention. In Patience, Grosvenor recites two examples of his “idyllic” verse, “Teasing Tom . . . a very bad boy,” and “Gentle Jane . . . as good as gold.” Swinburne uses both names, Tom and Jane, in referring to Buchanan. Because Buchanan concealed his identity under the pseudonym, “Thomas Maitland,” Swinburne observes that it was “not the good boy, Robert, for instance, but the rude boy, Thomas,” who was throwing stones and shooting off a popgun. Elsewhere Swinburne asks: “How should one address him? [Buchanan] ‘Matutine pater, seu Jane libentius audis?’ As Janus, rather, one would think, being so in all men’s sight a natural son of the double-faced divinity.”20 Teasing Tom was a very bad boy, How the ribald inner Gilbert must have chuckled when he wrote Grosvenor’s introduction of this priapic young sadist! “I believe I am right in saying that there is not one word in that decalet which is calculated to bring the blush of shame to the cheek of modesty.” To which Angela, echoed by “the young lady in the dress circle,” affirms: _____ 20 Swinburne Replies, pp. 71, 76-7. The Latin is identified by Hyder as a quotation from Horace: “O father of the morning, or Janus, if you would prefer to be so addressed.” _____ 380 “Not one; it is purity itself.” Swinburne never married, “single he did live and die”; but in 1867 he did contract a notorious liaison with a “girl in the corps de bally.” She was the beautiful actress and courtesan, Adah Isaacs Menken. The brief affair was arranged by Swinburne’s friends and was eagerly accepted by the poet; in his case it was good publicity to let it be thought that he indulged in anything so normal as keeping a mistress. The window dressing was so successful that a photograph of Algy and Adah together was sold in London stationery shops.21 Gentle Jane was as good as gold, The style of Grosvenor’s dreadful doggerel is a more-than-fair approximation of some of the highly moral stuff Buchanan contrived to publish. As Swinburne commented: “In effect there were those who found the woes and devotions of Doll Tearsheet or Nell Nameless as set forth in the lyric verse of Mr. Buchanan calculated rather to turn the stomach than to melt the heart.”22 We recall Bunthorne’s scorn of Grosvenor’s “placidity emetical.” However, except for his titles, Grosvenor’s verse is not really a parody of Buchanan. Totally without style, Buchanan, at his worst, defies parody. Perhaps this passage from “Attorney Sneak” represents Buchanan at his worst: “Tommy,” he dared to say, “you’ve done amiss; _____ 21 The Swinburne Letters, I, 295. _____ 381 Sucking the blood of people here in London; One wonders on what grounds the rhymer of “London” with “un-done” could cavil at Rossetti’s “Love-Lilee.” Also compare Grosvenor’s “totally” and “bally.” Here’s another; “The Widow Mysie. An Idyl of Love and Whisky”: O Widow Mysie, smiling soft and sweet The last line recalls the complaint about Swinburne’s “endless alliteration.” It also recalls the song of Patience: “If love is a thorn, they show no wit / Who foolishly hug and foster it.” One more example; Buchanan’s “Kitty Kemble,” a girl from the corps de bally: You pertly spake a dozen lines or so, Unlike Gentle Jane, Kitty did not marry her man of title; the consequence was she was lost totally. A comparison of these moral idyls _____ 23 Buchanan, London Poems (London, 1867), p. 168. “Attorney Sneak” was first published in 1866, two years after W. S. Gilbert became an impecunious young barrister. _____ 382 with those ascribed to Grosvenor reveals Gilbert’s vastly superior technique, which Swinburne specifically noted. In a letter entitled “The Devil’s Due,” signed “Thomas Maitland” (The Examiner, 1875), Swinburne called Buchanan “the multi-faced idyllist of the gutter,” and advised him: . . . to study in future the metre as well as the style and reasoning of the “Bab Ballads.” Intellectually and morally he would seem to have little to learn from them; indeed a careless reader might easily imagine any one of the passages quoted to be a cancelled fragment from the rough copy of a discourse delivered by “Sir Macklin” or the “Reverend Micah Sowls,” but he has certainly nothing of the simple and perfect modulation which gives a last light consummate touch to the grotesque excellence of verse which might wake the dead with “helpless laughter.”26 It can hardly be doubted that Gilbert was amused and gratified at Swinburne’s appreciation, and that the letter intensified his interest in the Fleshly Controversy. Both “Sir Macklin” and the “Reverend Micah Sowls,” from two different Bab Ballads, are long-winded clergymen who deliver boring, moralizing sermons. A certain line in Patience concerning Grosvenor, “Your style is much too sanctified—your cut is too canonical,” has been called by Williamson, “a rather obscure gibe as applied to a poet.”27 Jones agrees that this point _____ 26 The Swinburne Letters, III, 91-2. Swinburne’s delight in Gilbert is evident in several letters. To D. G. Rossetti, 1870: “By the way what a splendid ‘Bab’ that was in the Graphic for Christmas Day about the shipwrecked men and their common friend—I thought it one of the best—and it took me about an hour to read out en famille owing to the incessant explosions and collapses of reader and audience in tears and roars of laughter” (II, 106). To Andrew Chatto, 1886: Ordering two copies of “Gilbert’s comic operas,” published that year by Chatto & Windus; a third copy in 1888 (V, 154, 237). He also wrote three letters to Chatto requesting separate copies of the libretto for Ruddigore (V, 195, 201, 237). Ruddigore, produced in 1887, includes these lines: As a poet I’m tender and quaint— Did Swinburne ever attend a G&S performance? Lang notes that during his Putney retirement, the poet “came to loathe the theater, partly as a result of encroaching deafness” (I, xxxi). _____ 383 “has long troubled critics.”28 I suggest that the obscurity is readily dissipated if the line is read as a paraphrase of the gibe at Buchanan. Swinburne’s use of Buchanan’s alias, “Thomas Maitland,” also gives point to another of Bunthorne’s lines: “I’ll meet this fellow on his own ground and beat him on it.” This threat immediately precedes the “canonical” gibe. . . . in place of the man of God at whose admonition the sinner was wont to tremble . . . perhaps a comic singer, a rhymester of boyish burlesque; there is no saying who may not usurp the pulpit when once the priestly office and the priestly vestures have passed into other than consecrated hands. For instance, we hear, in October, say, a discourse on Byron and Tennyson . . . we stand abashed at the reflection that never till this man came to show us did we perceive the impurity of a poet who can make his heroine “so familiar with male objects of desire” as to allude to such a person as an odalisque “in good society”; we are ashamed to remember that never till now did we duly appreciate . . . the depravity of the Princess Ida and her collegians.”29 _____ 28 In line with his theory that Grosvenor is primarily Coventry Patmore, Jones holds that the line refers to the “popular notion” of Patmore’s prissy character: “For the purpose of public satire, the popular notion of the poet’s personality is a fitter subject than his real character.” I would argue that the “popular notion” is manifestly irrelevant since, in eighty years, Jones is the first man to appreciate the joke. If “public satire” of anybody was intended, this must surely be Gilbert’s most spectacular failure. A clever Monkey—he can squeak, Cf. Princess Ida: A Lady fair of lineage high, _____ 384 The quotation recalls a passage from Tennyson’s The Princess: “Our statues!—not of those that men desire, / Sleek Odalisques, or oracles of mode.” And if we have “the keen penetration of Paddington Pollaky,” perhaps we may find a recollection of Swinburne’s sarcasm among the elements that make up a Heavy Dragoon in Patience. These include “Tupper and Tennyson” (but not very much of him) and the “Grace of an Odalisque on a divan.” It cannot be denied that this effeminate grace stands out in startling incongruity to the other attributes of a Heavy Dragoon. Did Gilbert throw it in merely for want of a better rhyme? With irresistible attack _____ 30 The Swinburne Letters, I, xlviii. _____ 385 The change had really turned his brain; “Gentle Archibald” appeared in Fun, May 19, 1866, and it may not be unreasonable to speculate that Gilbert, realizing the possible association of ideas, withheld it from Hotten because of the publisher’s known pornographic ventures.31 Goldberg, commenting at length on “Gentle Archibald” as one of the “lost” Bab Ballads, has remarked that Gilbert never acknowledged the relationship with “Teasing Tom.”32 Nevertheless, the name “Archibald” was eventually bestowed on Grosvenor. It is certain that Gilbert originally intended to use the name “Algernon” for at least one of his poets. A stage direction from an early draft of the libretto reads at a certain point: “Algernon Bunthorne enters followed by ladies.” Elsewhere in the same draft, Patience, speaking to Grosvenor, says, “Farewell, Algernon!”33 The final choice for Bunthorne’s Christian name is equally significant. It was apparently no secret that Swinburne used “Reginald” as a nom de plume in his lewd correspondence. Clyde Kenneth Hyder notes that as early as 1871 a novel introduced “Reginald Swynfen, obviously a defamatory caricature of the poet.”34 Nevertheless, Swinburne defiantly called himself “Reginald Harewood” in Love’s Cross-Currents, published in 1877 as A Year’s Letters, and later gave the name “Reginald Fane” to a flogged schoolboy in The Whippingham Papers. _____ 31 Steven Marcus, The Other Victorians (New York, 1967), p. 68. _____ 386 the flogging block and bullying of Eton, expressed the desire to join a cavalry regiment, a project firmly vetoed by his father.35) At this point in the libretto Gilbert had written a solo for the Duke which was eliminated before the opening performance. However, it survives in the British Museum in the manuscript which had been submitted to the Lord Chamberlain for approval. The Duke sings, in part: . . . Scandal hides her head abashed, Society forgets her laws, The reference to scandal is intriguing, but the song seems to have no thematic relevance to Patience, whether the context be curates or poets. We can understand its deletion, but why was it written in the first place? Is it possible that Gilbert had heard a garbled version of an anecdote related by Edmund Gosse? Lady Ritchie, Thackeray’s daughter, met Swinburne at Lord Houghton’s home in 1862. The company included her father, her sister, and the Archbishop of York, to whom the poet read his “The Leper” and “Les Noyades.” According to Gosse, the Archbishop did not wink. On the contrary, his Grace was silently horrified, while Thackeray and his daughters were enchanted by poet and poetry alike.37 Manifestly, Swinburne’s rank and money did not protect him from scandal, although he did have a few influential apologists. Lady Ritchie, the highly respectable Edmund Gosse, and others remained Swinburne’s life-long friends. So, of course, did the very model of a Victorian _____ 35 Cassidy, p. 33. _____ 387 factotum general, Theodore Watts-Dunton, described by Lang as “the dingy old nursemaid who, irresistibly, excites the satirist in every man.”38 (Bunthorne, introducing his solicitor: “Heart-broken at my Patience’s barbarity,/ By the advice of my solicitor . . . I’ve put myself up to be raffled for!”) This costume chaste Let me confess! The musical ear of “the young lady in the dress circle” was insufficiently attuned. She did not catch the faint counterpoint of one of Swinburne’s most frequently quoted lyrics: Men touch them, and change in a trice

Wayne, New Jersey _____ 38 The Swinburne Letters. I, xliii. ___

‘Mr. Gilbert and Dr. Bowdler: A Further Note on Patience’ by John Bush Jones

Brief Articles and Notes MR. GILBERT AND DR. BOWDLER: John Bush Jones

A number of years ago I first hypothesized in the pages of this journal a composite prototype for the character of Archibald Grosvenor in Gilbert and Sullivan’s Patience, that composite consisting of traits of the poetry and persons of William Morris and Coventry Patmore.1 I am pleased that since then I have received a number of favorable responses to this suggestion—both in print and informally—and no less pleased to find that my remarks have helped stimulate at least one lively controversy over that character identification. In the course of exposing a possibly covert, private level of satire in Patience, William D. Jenkins suggests that Grosvenor is modeled, at least in part, on Robert Buchanan, author of “The Fleshly School of Poetry” and perhaps Swinburne’s most vituperative detractor.2 Such an identification works well in the context of the opera as a rival and foil to the Bunthorne- Swinburne figure, and though some of Mr. Jenkins’ ingenuity in compiling supporting evidence occasionally may strain the reader’s credulousness, nevertheless, the main thrust of his argument deserves serious consideration. _____ 1 “In Search of Archibald Grosvenor: A New Look at Gilbert’s Patience,” VP, 3 (1965), 45-53. _____ 66 I believe I am right in saying that there is not We no longer recognize the last phrases of this speech as a literary allusion, but it is quite probable that the audiences in Gilbert’s day would and especially the respectable family audiences at the Savoy, “many of whom scarcely attended any other theatre.”4 More even than an allusion, these lines are almost a verbatim borrowing from that eminent expurgator and precursor of Victorian verbal delicacy, Dr. Thomas Bowdler: It certainly is my wish, and it has ever been my study, to exclude from this publication whatever is unfit to be read aloud by a gentleman to a company of ladies. I can hardly imagine a more pleasing occupation for a winter’s evening in the country than for a father to read one of Shakspeare’s plays to his family circle. My object is to enable him to do so without incurring the danger of falling unawares among words and expressions which are of such a nature as to raise a blush on the cheek of modesty [my italics].5 While it is merely coincidental and interesting, perhaps, that Grosvenor is indeed reading to a “company of ladies,” it is a fact that Bowdler’s expurgated Shakespeare remained one of the most popular editions of the dramatist throughout the nineteenth century,6 at the same time that his name became synonymous with editorial priggery. A rather strange case of concurrent popularity and humorous notoriety, and, as such, a perfect subject for satire. Furthermore, Bowdler’s Shakespeare was mostly in the homes of that sort of decent middle-class folk who also attended Gilbert and Sullivan operas, and it is for this reason that it is probable, though not provable, that Gilbert’s echo of the good doctor’s preface did not go unrecognized and unappreciated. _____ 3 Gilbert, Patience, in The Savoy Operas (Oxford Univ. Press, 1962), I, 207. __________

So much for Patience. I’ve had these items for a number of years now but I was holding onto them because I was planning a separate section on fictional representations of Robert Buchanan. However, I’ve now given up - there aren’t any. In 2009 the BBC broadcast a TV series called Desperate Romantics, which gave a fictional account of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, which unfortunately ended with the retrieval of Rossetti’s poems from the grave of his wife. I waited in vain for a second series, but none was forthcoming and Dante Gabriel Rossetti was shortly off to Cornwall and made a bit of a stir by taking off his shirt to mow his lawn. In 1967 Ken Russell had made a 90 minute film for the BBC’s Omnibus programme on the same subject. Dante’s Inferno featured Oliver Reed as Dante Gabriel Rossetti and began with the exhumation of the poems and then went into flashback. When it caught up with itself, that event was taken as the cause of Rossetti’s descent into madness and the suicide attempt. Buchanan does not appear although an anonymous critic of Rossetti’s poems gets the briefest of mentions. When it was first broadcast, this was probably seen as adventurous stuff, whereas now, it just looks a bit naff. It is available on youtube (Part 1, Part 2 and for some reason, a Russian version). |

|

|

2022 ”However, I’ve now given up - there aren’t any.” Seems I spoke too soon. In December 2021, a novel featuring Harriett Jay and with a passing mention of Robert Buchanan, written by Peter Regan, appeared on Amazon, under the title, The Strange Case of Robert Louis Stevenson. Here’s the blurb: ‘Robert Louis Stevenson is hunting a monster. London, the latter half of the 19th Century. A writer, trying to find inspiration, walks home alone for the evening only to find himself in unfamiliar surroundings. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|