|

Play List: 4. Corinne 7. The Mormons 9. Lucy Brandon 10. Storm-Beaten 11. Lady Clare 13. Bachelors 14. Constance 15. Lottie 16. Agnes 17. Alone in London 18. Sophia 19. Fascination 20. The Blue Bells of Scotland 21. Partners 24. Angelina! 25. The Old Home 26. A Man’s Shadow 27. Theodora 29. Clarissa 30. Miss Tomboy 32. Sweet Nancy 33. The English Rose 36. Marmion 37. The Gifted Lady 38. The Trumpet Call 39. Squire Kate 40. The White Rose 42. The Black Domino 44. The Charlatan 45. Dick Sheridan 47. Lady Gladys 48. The Strange Adventures of Miss Brown 49. The Romance of the Shopwalker 52. Two Little Maids from School ___ |

|

ROBERT WILLIAMS BUCHANAN (1841 - 1901) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

ROBERT BUCHANAN’S OTHER PLAYS

“He turned out work at a rate which was appalling. He would produce half a dozen plays in a year, and have another half-dozen ready for production. In the pigeon-holes of his study, at Merkland, he had always a score of unacted plays, ranging from comic operas to historical tragedies.”

1. Unproduced Plays There is enough evidence (news reports, copyright performances etc.) to assume that the following plays were written although none were ever given full productions. 3. The Squireen

Written for Herman Vezin (with whom Buchanan later collaborated on Bachelors), The Flying Dutchman was never produced on stage. Buchanan blamed the production of Henry Irving’s Vanderdecken (by W. G. Wills and Percy Fitzgerald) which opened at the Lyceum on June 8th, 1878 for pre-empting his own version. He later returned to the same subject in the novel, Love Me For Ever (1883) and the poem, The Outcast (1891).

The Yorkshire Post and Leeds Intelligencer (8 February, 1878 - p.5) “THE FLYING DUTCHMAN.”—Mr Hermann Vezin is about to appear in a character admirably suited to his weird, intellectual style. In the “Flying Dutchman”—the title of the new play, said to be written by Mr Robert Buchanan—he is, it is said, likely to surpass all his former creations, and to secure recognition as one of our greatest living actors. ___

The Bristol Mercury and Daily Post (9 February, 1878) —Mr. Herman Vezin will shortly appear in a new character at the Queen’s Theatre, which will surpass all this well- known actor’s previous creations, including “The Man o’ Airlie” and “Dan’l Druce.” The title of the new play is the “Flying Dutchman,” and it is said to be written by Mr. Robert Buchanan. The hero of the piece is specially adapted to Mr. Vezin. ___

The Examiner (22 June, 1878) We believe there is no foundation for Mr. Robert Buchanan’s complaint that Vanderdecken was hurried on the Lyceum stage to anticipate a play on the same subject which he had written for Mr. Herman Vezin. The idea of finding a rôle for Mr. Irving in the Flying Dutchman was suggested to the Lyceum management several years ago, while Mr. Bateman was still alive. ___

The Era (19 September, 1891 - p.10) MR ROBERT BUCHANAN, the indefatigable, has just published a long, and in many respects an admirable, satirical poem on the subject of the Flying Dutchman. It is perhaps the best as well as the most ambitious piece of work that Mr Buchanan has done for many a day. It may not be generally known that before Mr Irving produced the Vanderdecken of Mr W. G. Wills Mr Buchanan had written a blank-verse play upon this same subject—which play was, we believe, to have been produced on the London stage by Miss Sophie Young. This drama no doubt begat in the poet’s mind the satire of to-day; but we understand that there was little, if any, likeness between the two works, except in the conception of the great love-motive of the story. Nor, indeed, does Mr Buchanan often care to give to the theatre work so daring as much of that which he offers to the library in this his later Vanderdecken. ___

The Stage (10 January, 1924 - p.17) The following letter from Mr. Shear is of great interest to me, reviving, as it does, memories of the struggles of the giants of the past. “Venderdecken” was one of the few Irving failures at the Lyceum, when everyone thought it would be one of his great successes. “The Flying Dutchman” of Robert Buchanan might have been the great success for which Herman Vezin waited so long. Who knows? There is tragedy always in the telling of lost chances, and that fine actor, Herman Vezin, seemed to be always losing them. Such is fate. I am always glad to hear from Mr. Shear, who is a chronicler from the pure love of the theatre, and his letters of correction are always welcome on that account; but in this particular instance I was referring to the modernised version of “The Flying Dutchman,” in which Vanderdecken appears part of the time in modern garb, and this was written from the old version to suit Beerbohm Tree. Playgoers’ Club, Dear Pillicoddy, ___

I also came across the following from 1883, which is rather too speculative to serve as evidence that Buchanan’s play was still being considered for production. However, the story in the Illustrated London News was Buchanan’s novel, Love Me For Ever, which was a reworking of the Flying Dutchman legend. The play which eventually followed Charles Reade’s Dora at the Adelphi on March 14th, was Buchanan’s Storm-Beaten, an adaptation of another of his novels, God and the Man.

Liverpool Mercury (25 January, 1883) We understand that Mr. Robert Buchanan’s new play will be produced on the withdrawal of “Dora.” It is said to be founded on the story that formed the Christmas number of the Illustrated London News. Mr. Buchanan’s success as a dramatist has not hitherto been equal to his deserts, but this has been due to accidental circumstances that may be easily avoided in the future. There is little reason why the author of a romance so powerfully dramatic as “God and the Man” should not take a place very high indeed among living dramatists. The principal part in the forthcoming drama is to be played by Miss Harriet Jay, a young lady whose impersonation of Lady Clancarty is said to be among the most exquisite yet seen. Miss Jay is well known as the authoress of stories of Irish life, some of which, like “The Priest’s Blessing” and “The Queen of Connaught,” are, in the opinion of such an excellent judge as Mr. Charles Read, among the most remarkable products of the time in fiction. The lady is also known as an accomplished actress, and in this capacity she recently gave some Wednesday matinées at the Gaiety Theatre, where she appeared as Lady Jane Grey in Mr. Buchanan’s stirring drama. We understand that Miss Jay may before long be expected in Liverpool. She is looked to as one of the notable artistes of the immediate future.

Back to the Bibliography or the Plays _____

2. A Hero in Spite of Himself (1884)

According to Harriett Jay’s biography of Buchanan, this play was never written. In her brief mention of their American adventure, she writes: “In the year 1884 he made his first and only trip to America. He had a contract to supply a play to Messrs. Shook and Collier, then managers of the Union Square Theatre, New York, but he went without having written it. On his arrival he offered for their acceptance a melodrama which was our joint work, and which has since become popular under the title of ‘Alone in London.’” Four years later, Messrs. Shook and Collier took Buchanan to court for the repayment of their $750 advance for the play and, on winning the case, were eventually paid from money owing to Buchanan from the American production of Partners. This prompted Buchanan to present his version of events in a letter to The Era. As far as I know, A Hero in Spite of Himself was never produced either in America or Britain, but in October, 1886, a novel-length story by Buchanan, bearing that title, began serialisation in The York Herald. The book begins with a ‘first act’ in England, then the scene shifts to the east coast of America, and is quite in keeping with the ‘American society drama’ which Buchanan was commissioned to write. However, the action then moves to the wild west and the characters in red shirts and top boots are introduced, which Messrs. Shook and Collier took exception to, before returning to New York for the final scenes. The story was never published in book form, but it is available to read on this site: ___

The New York Times (20 December, 1888) NOT TRUE TO AMERICAN LIFE. In 1884, when Sheridan Shook and James W. Collier were managing the Union-Square Theatre, Robert Buchanan engaged to write them an American society drama, for which he was to receive £1,000. An advance payment of £150 was made, and in due time the new play was brought over. It was called “A Hero in Spite of Himself,” and was built on the English ideas of Western life. The male characters would have been obliged to wear red flannel shirts and tuck their trousers into their boot legs, and the ladies in the cast would have appeared in costumes equally incongruous to real American society. Shook & Collier sued Mr. Buchanan to recover their £150 advance, and yesterday David Gerber of ex-Judge Dittenhoefer’s office presented the case to the jury in the Supreme Court, before Judge Lawrence. Mr. Buchanan was defended by Howe & Hummel. The jury were not satisfied with Mr. Buchanan’s ideas of American society and brought in a verdict against him of $945. ___

The Galveston Daily News (21 December, 1888) Received a Verdict for $945. NEW YORK, December 19.—[Special]—In the supreme court, before Judge Lawrence and a jury to-day, Messrs. Shook & Collier, formerly managers of the Union Square theater, received a verdict of $945 against Robert Buchanan of London. In 1884 Buchanan wrote the plaintiffs asking if they wanted a good “romantic society drama.” They replied in the affirmative, and Buchanan stated that his terms were $5000, $750 of which was to be paid in advance. Shook & Collier paid the advance price, and Buchanan sent over a play entitled A Hero in Spite of Himself. The play was a story of western life and the scene was laid on the prairies. The characters were to be arrayed in red shirts and top boots. The managers decided that the play did not come quite within the society drama limit, returned it and demanded that the advance money be returned to them. This was refused and they brought suit. ___

The Era (2 March, 1889) THE DRAMA IN AMERICA. NEW YORK, MONDAY, FEB. 18.— . . . SOME time since Messrs Shook and Collier recovered $1,135.13 from Mr Robert Buchanan in their suit against him for the advance payment to him on account of the American society play he was to furnish them for the Union-square Theatre, and which they refused to accept on the ground that it was not an American society play. Hitherto, efforts to recover any of the amount have been vain. Recently, however, it was discovered that the production of Partners was under a contract by which Mr Buchanan received five per cent. of the gross receipts, and that $588 was here belonging to him. On Saturday an order was procured from Judge O’Brien requiring Mr Buchanan to show cause why a receiver of his property should not be appointed. In this order the playwright is referred to as an insolvent debtor. ___

The Era (9 March, 1889) THE AMERICAN MANAGER, OLD STYLE. TO THE EDITOR OF THE ERA. Sir,—America is still a long way off, and American ways, especially in the matter of law, are still far beyond the comprehension of purblind Europeans. The paragraph contained in your issue of to-day, and stating that a certain Judge O’Brien has issued an order to attach certain monies of mine at the suit of Messrs Shook and Collier, late of the Union- square Theatre, needs a little explanation.

Back to the Bibliography or the Plays _____

3. The Squireen (1891)

I first came across this title in the catalogue of the New York Public Library: “Promptbook. Typescript in the New York Public Library. 1 vol. ; 28 cm. [“With this is bound: Buchanan, Robert Williams, 1841-1901. “The squireen.” A second copy.”]” And it is also listed in Dramatic Compositions Copyrighted in the United States 1870 to 1916 (Library of Congress Copyright Office): “Squireen (The); an Irish drama in 4 acts, by Robert Buchanan and A. Boucicault. ___

The Glasgow Herald (20 October, 1890 - p.9) Mr Robert Buchanan is, we understand, engaged upon a new Irish drama, written in collaboration with Mr Aubrey Boucicault. ___ The Stage (12 December, 1890 - p.11) The benefit of Mrs. Boucicault at the Fifth Avenue, New York, on Tuesday, November 27, turned out very successfully, £400 being the result. In speaking of it the Spirit of the Times says:— Yesterday afternoon, at the Fifth Avenue Theatre, a testimonial benefit was given to Mrs. Agnes Robertson Boucicault, who deserves the recognition and needs the money. Horace Wall was in charge and reports the receipts, at advanced prices, as over $2,000. Sothern played a scene from The Highest Bidder, with Nina Boucicault. Mrs. Boucicault appeared in a scene from The Long Strike, with Mr. Stoddard. Everybody volunteered to sing or act or recite, and the audience threw flowers enough to redeem the Amphitheatre Show. The benefit was deprived of an attractive feature by the withdrawal of Mr. and Mrs. Kendal, who declined to play under H. C. Miner’s management. The circumstances seem to us to justify this public rebuke; for Miner’s claim that you do not hire the box-office when leasing a theatre is like saying you have no right to handle the money when you take charge of a bank. However, Mr. and Mrs. Kendal made up for their absence by paying $100 for a box and presenting it to Mrs. Boucicault. One is always liable to be misunderstood, but I must say I was surprised to receive from Mr. Aubrey Boucicault the following letter:— In reading over the “Chit Chat” in this week’s STAGE, I find mention of my mother and self. It is stated that on her return from America she will appear in a play by me. This is not so, the play being by Mr. Robert Buchanan and “yours truly.” The former does not require “lifting by a trick,” the latter only hopes that he may have inherited a small portion of the abilities which his father possessed. What does it mean? Well, Mr. Aubrey Boucicault read in THE STAGE last week a paragraph in which I showed how the Nottingham Daily Guardian had been “lifting” some remarks of mine about himself and his mother without any acknowledgment, and had done the trick very neatly by altering a couple of words. Whereupon Mr. Aubrey Boucicault jumped to an extraordinary conclusion—that the “lifting” and the “trick” referred to himself. If Mr. Aubrey Boucicault cannot reason better than this in future, his plays will, I fear, suffer. |

|

|

[Advert for The Squireen from The New York Dramatic Mirror (6 February, 1892 - p.7).]

Cleveland Plain Dealer (7 February, 1892 - p.14) One of the effects of Scanlan’s withdrawal from the field of Irish comedy will be an attempt to establish Aubrey Boucicault as a star. He will be managed by Arthur Rehan, who has taken his sister’s stage name for use theatrically, and the play will be called “The Squireen.” It was written by Robert Buchanan, revised by Aubrey Boucicault and thoroughly worked over again by Mr. Buchanan. ___

The Era (20 February, 1892 - p.10) IT is said that Mr Robert Buchanan has written a new Irish play, in collaboration with the boyish Mr Aubrey Boucicault, who feels that the time has come when he must go a-starring through the States, like his father. “I am convinced that young Boucicault will be one of the best paying stars in the world,” says Mr Arthur Rehan, his acting-manager—as what else should an acting-manager say? The play has the capital title of The Squireen, and it is odd to note that Mr Buchanan’s other new play is called Squire Kate—both names recalling Mr Pinero’s first great success. Squire Kate indeed, as we understand, is like “The Squire” Kate Verity, a lady farmer. ___

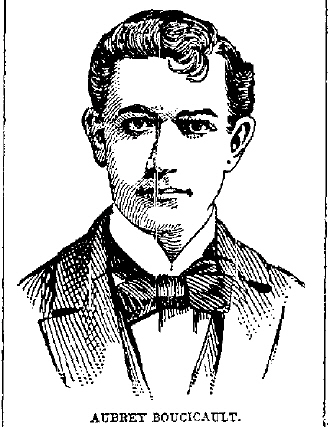

Logansport Pharos (Indiana, USA) (24 April, 1896) AUBREY BOUCICAULT. A Handsome Young: Actor Who Is Rapidly Making His Mark. Persons who are good judges of dramatic ability declare that in Aubrey Boucicault the American stage has a worthy successor to his father, the late Dion Boucicault, who, as every old theater goer will remember, was a few years ago considered inimitable in the delineation of the rollicking Irish hero. Aubrey has not the physique of his distinguished progenitor, but he has a face that would easily serve, with slight alterations, for the model of a Greek god. He is naturally, therefore, a very great favorite with that portion of the public which is supposed to be the mainstay of matinee performances. The young star has made essays in almost every department of theatrical work, and in none of them has he been less than tolerably good, while in many if not most he has really been excellent. It does not seem to be possible for him to make a genuine failure of anything that he attempts. Some of his wellwishers are anxious that he should abandon his present field of Irish comedy and take up a line of high grade society work, for which he is exceptionally fitted by reason of his handsome and refined personality. Should he decide to follow this advice, which he is now said to be considering seriously, he ought to find himself speedily in possession of a large and constantly increasing clientele. |

|

|

Aubrey Boucicault’s mother is Agnes Robertson. He was born in England 26 years ago. His first appearance on the stage as a professional was in St. Louis with Kate Claxton nine years ago, when he played the part of the cripple, Pierre, in “The Two Orphans.” Soon afterward he and his mother appeared in Bartley Campbell’s play, “My Geraldine,” with Duncan B. Harrison. Young Boucicault played the role originally played by W. J. Scanlan. ___

According to the article about Aubrey Boucicault in the Logansport Pharos, the play, which was never produced, was intended as a star vehicle for his mother. This, combined with its Irish setting and the odd circumstances surrounding its publication, have suggested that Buchanan’s novel, Lady Kilpatrick, is an adaptation of The Squireen. The series of letters to Andrew Chatto concerning Lady Kilpatrick do indicate that the original version of the novel, serialised in The English Illustrated Magazine in 1893, was not ‘written’ by Buchanan himself, but was a novelisation of one of his plays, a task which he sometimes assigned to others. This is all speculation of course, however there were two, supposedly unofficial, adaptations of Lady Kilpatrick which appeared in Australia and New Zealand, under the title:

Back to the Bibliography or the Plays _____

The New Don Quixote by Robert Buchanan and Charles Marlowe, was given a copyright performance at the Royalty Theatre on 19th February, 1896, after undergoing some problems with the censors. It was due to be produced at the Royalty Theatre, then under the management of the actor, Arthur Bourchier, but he left the Royalty at the end of July, 1896 and, as far as I know, the play was never given a full production. A couple of years later, items in the press refer to a proposed novelisation of The New Don Quixote but this also failed to appear. ___

The Stage (5 December, 1895 - p.11) The next production Mr. Bourchier will give at the Royalty is from the pen of the perennial author-dramatist-poet, Robert Buchanan. It has been named The New Don Quixote, and is a play with a serious motive, containing, in addition to a leading part for Mr. Bourchier, a very powerful character for his talented wife, Miss Violet Vanbrugh. _____ Apropos of Mr. Buchanan, this gentleman is looming up very large again on the dramatic horizon, for in addition to this play for the Royalty, and Miss Brown at Terry’s, he is in active negotiation with Mr. Weedon Grossmith for a finished play of the ultra-farcical order. ___

The Dundee Courier (16 December, 1895 - p.3) We are in for a pretty little quarrel between Mr Robert Buchanan and the Lord Chamberlain as the licenser of plays. In collaboration with another author, Mr Buchanan has written a four-act play called “The New Don Quixote.” The object of Mr Buchanan and his colleague appears to have been to meet Ibsen, so to speak, on his own ground and beat him. In the novelty and boldness of their treatment they are credited with having succeeded in this questionable object of ambition. It is not surprising, therefore, that the Lord Chamberlain has put his foot down. Mr Buchanan writes that he purposes to join issue with the Lord Chamberlain in the manner best fitted to secure public condemnation of that functionary’s action. This means that the play will be published, and that we shall all have the opportunity of reading it. ___

Edinburgh Evening News (16 December, 1895 - p.3) MR ROBERT BUCHANAN AND THE The Observer publishes from Mr Robert Buchanan an indignant remonstrance against the action of the Lord Chamberlain in refusing to license one of his dramas—“New Don Quixote,” a four-act play. He says: “I have no intention of resting quiescent under the imputations of the Lord Chamberlain, and I shall join issue with that functionary in the manner best fitted to justify me in the eyes of the public. Having been chosen as the scapegoat of my class, I accept the position, not altogether without satisfaction; for the time has come, I believe, when one man’s martyrdom may become the salvation of the English drama.” ___

The Glasgow Herald (16 December, 1895 - p.4) MUSIC AND THE DRAMA. (FROM OUR OWN CORRESPONDENT.) London, Sunday Night. Mr Robert Buchanan has to-day issued a lengthy protest against the new Examiner of Stage Plays. Mr Buchanan states “The New Don Quixote,” a four-act play, “written by myself and another author,” and accepted by Mr Bouchier for production at the Royalty Theatre, has just been returned to the manager with the intimation that it will not be licensed for representation. Mr Buchanan goes on to say that the Lord Chamberlain will take no official knowledge of authors as such, having, of course, to deal solely with theatrical managers, and that the public know his own views on the subject of censorship. He continues:—“The play in question is, I contend, pure and wholesome, though it deals boldly and seriously with some of the great issues of modern life. Its offence, I presume, consists in this, that it is neither trivial nor indecent in the ordinary sense, but that it is fundamentally and not superficially unconventional.” In accordance with custom in such cases, Mr Buchanan, it is understood, proposes to publish his play, when the public will be able to determine for themselves whether the reader of stage-plays or the author is in the right. ___

The Freeman’s Journal (Dublin) (16 December, 1895 - p.5) That stormy petrel of the drama, Mr. Robert Buchanan, has a new grievance against the Lord Chamberlain. He writes an indignant letter to the papers saying—“May I call your attention to the fact that the ‘New Don Quixote’ a four act play written by myself and another author, and accepted by Mr. Bourchier for production at the Royalty Theatre, has just been returned to the manager with the intimation that it will not be licensed for representation. No reason is assigned for this high-handed measure, and the licenser of plays on being appealed to by me to state the nature of the objections refers me to a clause in the Lord Chamberlain’s circular to the effect that the Lord Chamberlain has no official knowledge of ‘authors as such!’ Thus I am not only left under the stigma of having written a play which is unfit to see the light, but I am unable to ascertain in what respect I and my fellow author have offended!” As may be expected, Mr. Robert Buchanan is not going to lie quietly under the slur cast upon him by the Lord Chamberlain. At the same time it is impossible to see what effectual protest he can make, as there is absolutely no appeal from the decision of that functionary. Judging by his letter, the Lord Chamberlain does not merely take exception to any particular passages or scenes in the play, but refuses to license it on general grounds. Mr. Buchanan can, without the licence of the Lord Chamberlain, get the play produced privately at his own expense, but such a proceeding would be costly, and as far as one can see useless. ___

The Leeds Mercury (16 December, 1895 - p.5) Mr. Robert Buchanan is now going to have a tilt at the Lord Chamberlain and the licenser of plays. The “New Don Quixote,” a four-act play, written by him in collaboration with another playwright, and accepted by Mr. Bourchier for production at the Royalty Theatre, has just been returned, with the intimation that it will not be licensed for representation. As this indignity is unaccompanied by any explanation as to what are the objectionable features of the work, Mr. Buchanan is very wroth, and he plunges with characteristic precipitancy into the pains and glories of martyrdom. What he is going to do to the Lord Chamberlain, whom he conceives to have “insulted” him, he does not say, but something vague and terrible is hanging over the head of that distinguished Court official. “Having been chosen as the scapegoat of my profession,” writes Mr. Buchanan, “I shall accept the position, not altogether without satisfaction, for the time has come, I believe, when one man’s martyrdom may become the salvation of the English drama.” There is about that the defiant ring we might expect, but still it is irritatingly vague. Is Mr. Buchanan going to produce the play, and risk pains and penalties, or is he merely going to print it? He declares it to be pure and wholesome, “though it deals boldly and seriously with some of the great issues of modern life.” He assumes that its offence consists in the fact that “it is neither trivial nor indecent in the ordinary sense, but that it is fundamentally, and not superficially unconventional.” ___

The Gloucester Citizen (17 December, 1895 - p.3) The refusal of the Licenser of Plays to assign any reason for declining to license Mr. Robert Buchanan’s new drama, on the plea that he has “no official knowledge of authors,” has caused some indignation in the dramatic world. The Lord Chamberlain or Mr. Redford may be influenced by the celebrated advice that in giving judgment you ought never to give your reasons; but it is at least due both to the dramatist and the theatrical manager to state the objections to a particular play. Mr. Buchanan can publish his piece, and with such an advertisement it ought to secure considerable attention. ___

The Sheffield Evening Telegraph and Star (17 December, 1895 - p.2) A NEW DON QUIXOTE. Mr. Robert Buchanan is a hard hitter, and we may expect some breezy passages in the campaign which the popular novelist-playwright has commenced against the Lord Chamberlain’s department. With the Lord Chamberlain lies the nominal duty of licensing plays, with a right of vetoing those which he may consider likely to be subversive of the public morals. The Lord Chamberlain, an estimable nobleman, who owes his position partly to his attachment to a political Party and partly to the favour in which he is held in Court, finds it difficult to combine the labour of drawing up lists of precedence at Court and adjudicating upon the merits of the productions of our great playwrights, and he deems it prudent to relegate the criticism of the plays to a subordinate. The gentleman who at present hold the important position of Licenser of Plays, Mr. Redford, has the advantage, so far as regards criticism against himself, of being unknown. He was, we believe, previous to his appointment as censor of the English stage, engaged in a bank or mercantile house in London, and the reasons which led to his selection for the post he now occupies have never been disclosed to an inquisitive public. He may, of course, have been an ardent student of the stage, and may have acquired a peculiar capacity for estimating the worth and morality of the productions which playwrights seek to give the public, but he successfully hid his light under a bushel, and, until his appointment of Licenser of Plays was notified, no one outside that small circle which enjoyed the privilege of Mr. Redford’s personal acquaintance had any notion that Mr. Redford was in existence. In the exercise of his jurisdiction, Mr. Redford has placed an embargo upon a play, “A New Don Quixote,” written by Mr. Robert Buchanan, and accepted by Mr. Bourchier, for production at the Royalty Theatre. Mr. Redford has not been gracious enough to assign any reason for his action, so that the author may, should he choose, expunge the features which, in his infinite wisdom, the Licenser of Plays deems objectionable. The play has simply been returned to the author, with the intimation that the necessary license is withheld. Mr. Bourchier’s plans are put out of joint, and Mr. Buchanan is left with the result of several months’ work upon his hands. This is an indignity which it is not unnatural both author and theatrical manager should resent. Mr. Buchanan is one of the most powerful playwrights of to-day, and if he does not always bow the knee to the goddess of conventionality, he is the last man in the world to be suspected of writing a play inherently immoral and calculated to degrade the public taste, while it can hardly be conceived that Mr. Bourchier, a highly successful theatrical manager, would imperil his reputation by the production of a play likely to lower the estimation of the stage. The odd thing is that Mr. Buchanan, while prohibited by Mr. Redford’s fiat from letting the public pronounce judgment upon his work in its original form, is under no restriction from publishing it in another way. There is no censorship of books prior to publication, and if Mr. Buchanan’s play in this form was judged worthy rather than many of the novels which are poured out of the press as a fit subject for prosecution it must be in striking contrast to the author’s previous works. If the play be published, as Mr. Buchanan threatens, and, we hope, intends, and it should be then condemned, Mr. Redford would certainly be justified, but in the event of the publication being unheeded by the authorities there will be established the anomaly that the play which by the Licenser’s dictum is to be strangled stillborn may be read at any fireside in the country. The publication of the play will be awaited in literary circles with consuming interest, and, unless it be found extremely gross, fuel will be added to the agitation for the abolition of the Lord Chamberlain’s veto. Mr. Buchanan is no faint-heart, and he may be trusted to press the matter, even though he knows that he is assuming the role of a “new Don Quixote” in tilting at a windmill in the shape of an established official with a very comfortable berth. ___

Glasgow Evening News (17 December, 1895 - p.4) A PLAYWRIGHT’S PROTEST. So the hour has come, and the man, and the blow is to be struck against a tyrannous, antiquated, and moth-eaten survival of superstitious and Puritanical slavery. Let us take off our hats and huzza. Our enthusiasm should be all the greater because the intrepid individual who is to pluck the beard of tradition and tweak despotism by the nose is a compatriot and an old Glaswegian to boot—none other than Mr Robert Buchanan. Once more is the Scot in the deadly breach, and if the office of Licenser of Plays is henceforth and for ever made effete or nugatory, the credit will be due to the porridge and kale that made possible such pluck as our poet is about to show. Mr Buchanan—to begin at the beginning—has written a play in collaboration with a friend. It is a four-act play; the name of it is “The New Don Quixote,” and it has already been accepted by Mr Bourchier for production in a London theatre. What the motif of the play is we have no definite information upon as yet, but there is every reason to believe that it is what the cultured call erotic and the vulgar call “rorty.” “It deals,” to quote Mr Buchanan’s own words, “boldly and seriously with some of the great issues of modern life,” and “while neither trivial nor indecent in the ordinary sense, it is fundamentally and not superficially unconventional.” From this guarded explanation we are free to assume that “The New Don Quixote” is a Fellow Who Did, a regular Hill-Topper with the Yellow Aster and a bar sinister blazoned for emblems on his shield. Possibly he took Dulcinea with him on his knight-errant adventurings, and left Sancho Panza at home; at all events, that is the sort of thing a modern Cervantes under Bodley-Head influences would be sure to do, and there would be three thrills and one shock to every act. But, alack-a-day! the bloated and tyrannous emissary of a bigoted grandmotherly Government won’t license the masterpiece for the stage. It is hardly necessary to say that Mr Buchanan, the irreconcilable, will not tamely submit to such a ban upon his work. He faces the situation with the stern, bitter smile of the man who says “I knew it,” and intimates that he is satisfied to become the martyr for the salvation of the English drama. We might have preferred a more definite indication of what he means, but no doubt it’s all right. It is perhaps possible that he will the play in spite of the censor. We can imagine him making up a scratch company of earnest theatrical amateurs of the problem play order, and going round Britain with a fit-up, barnstorming in the rural districts, and setting up one-night stands in country towns where the police are not numerous. A crusade like this, at once educative and protestant, could hardly fail to have the support of the stage generally, and the “tommyrotic” school of new writers would gladly join in. It would be too absurd for the Lord Chamberlain to attempt to quell the insurrection by military, and it would probably be found after a while that nobody was any the worse for the performance of “The New Don Quixote,” however little the better they might b e. And when we remember some of the theatrical productions the licenser has licensed of late years, we don’t feel that we would have any poignant regret if the Buchanan revolt brought about his abolition as a State functionary. ___

The Sporting Life (18 December, 1895 - p.6) Mr. Redford, the present “Examiner of Plays,” is on his trial—in the Court of Criticism and (to quote from Mr. William Mackay’s brilliant “popular Idol”) the Court of Common Sense. So far, we only know one side of the question, and Mr. Robert Buchanan puts it as follows:—“May I call your attention to the fact that ‘The New Don Quixote,’ a four-act play written by myself and another author, and accepted by Mr. Bourchier for production at the Royalty Theatre, has just been returned to the manager, with the intimation that it will not be licensed for representation. No reason is assigned for this high-handed measure, and the Licenser of Plays on being appealed to by me to state the nature of his objections, refers me to a clause in the Lord Chamberlain’s circular to the effect that the Lord Chamberlain has no official knowledge of ‘authors as such!’ Thus I am not only under the stigma of having written a play which is unfit to see the light, but I am unable to ascertain in what respect I and my fellow-author have offended! My opinions on the subject of the Censorship are well known, and need not be recapitulated here. I know the tyranny under which the English drama struggles to exist, and I know also how indifferent the English public is to all questions which involve the independence of art and artists; but I really did not know that the Lord Chamberlain possessed the power to suppress a play and insult an author without assigning any definite reason. The play in question is, I contend, pure and wholesome, though it deals boldly and seriously with some of the great issues of modern life. Its offence, I presume, consists in this—that it is neither trivial nor indecent in the ordinary sense; but that it is fundamentally, and not superficially, unconventional. I need hardly say that I have no intention of resting quiescent under the imputations of the Lord Chamberlain, and that I shall join issue with that functionary in the manner best fitted to justify me in the eyes of the public. Having been chosen as the scapegoat of my class, I shall accept the position, not altogether without satisfaction; for the time has come, I believe, when one man’s martyrdom may become the salvation of the English drama.” My own opinion of the function which Mr. Redford fulfils is that it is an impertinent and intolerable nuisance, and ought to be swept away. The best Examiner of Plays is the British public. Mr. Buchanan pursues his present crusade against the accident who holds the office, supported by the sympathy of every friend of healthy free trade in dramatic literature. Most of us know no more of Mr. Redford than we do of the wire worker in a puppet show. So far as his performances have gone he has shown, at any rate, than an experience of banking is calculated to make an Examiner of Plays an excessively indulgent censor. Compared with “The Novel Reader,” which was vetoes years ago, there have been plays performed which reduce that production to the level of “Old Mother Hubbard” and “Mary Had a Little Lamb.” Has Mr. Buchanan in “The New Don Quixote” gone one better—or worse—than the authors of the works which bear the Redford stamp of approval? One is reluctant to think so, and yet to what inference is one reduced by Mr. Redford’s autocratic “No?” But there is another point concerning which everybody is agreed. Who is the Lord Chamberlain, and who is his man Friday, that they should decline to give their reasons for refusing to licence “The New Don Quixote.” They are public servants, and paid out of the public purse for what they do. The gentleman in the gallery at the Victoria Theatre was forgiving on the subject of grammar—he did not expect it—but, said he, with a pardonable conviction that he was at least entitled to that for his money—“You might jine your flats.” The Lord Chamberlain and his literary and dramatic adviser might at least be courteous. ___

The Penny Illustrated Paper (21 December, 1895 - p.394) Robert Buchanan v. Mr. Redford. It was bound to come. Here is Mr. Robert Buchanan breathing fire and slaughter against the Licenser of Plays, while the Press looks on and chuckles. Everyone expected something of the kind when Mr. Redford was appointed, and the only surprise is that it has not come sooner. We had all got used to Mr. Pigott, and though dramatists occasionally grumbled and wrote letters to the Times, his position was an assured one, which the public wee inclined to back. Mr. Redford, however, stands on rather different ground, and it is an eloquent tribute to his courage that he should have chosen of all people in the world Mr. Robert Buchanan as his victim. This gentleman has, it seems, written a play which was accepted by a manager, and all was clear for production. Unfortunately, however, the Examiner did not see his way to give it the cachet of the Lord Chamberlain, assigning no reasons for his action. Mr. Buchanan is a past master in the art of controversial warfare, he has emerged victorious from scores of paper battles, and his fierce dialectics are not to be lightly regarded. I do not suppose Mr. Redford will permit himself to be dragged into the arena but clearly this is not going to prevent Mr. Buchanan smiting him hip and thigh. Certainly it is very hard lines on a man who has spent much time on a play to have its most profitable avenue of publication—the stage—stopped to him. But at the same time, it is obviously in the public interest that British audiences should be protected from the gross prurience of the Paris stage, and that it should be the duty of some public man like Mr. Redford to keep our dramatic food as wholesome as possible in these days of insidious plays on “women with a past.” ___

The Illustrated Sporting and Dramatic News (21 December, 1895 - p.11) MR. ROBERT BUCHANAN is very angry because the Lord Chamberlain has refused him a licence for a new drama of his called The New Don Quixote. Whether he does well to be angry we cannot tell till he prints the offending piece; neither can we yet say whether he is justified in pronouncing himself “the scapegoat” of his profession. But we should certainly be inclined to sympathise with him if he could not find out the reason for which objection is taken to his piece. Of course he made a mistake in addressing the Lord Chamberlain on the subject himself. That functionary naturally replied that he had “no official cognisance of authors as such.” The proper person to apply to in the matter is the manager, who proposes to be responsible for the production—Mr. Arthur Bourchier of the Royalty. If that gentleman puts himself in communication with Mr. Redford, the new examiner of plays, we doubt not that he will obtain full satisfaction. _____ As a matter of fact, there is no appeal against the decisions of the Lord Chamberlain’s department, nor do most managers wish that there should be. If there is to be any censorship of the stage it could not well be less oppressive than it is under the present régime; and if the tribunal were to be transferred to the police-courts, theatrical entrepreneurs know very well that they would only be jumping out of the frying-pan into the fire. ___

The Western Daily Press, Bristol (23 December, 1895 - p.3) The mystery of the refusal of the Lord Chamberlain to license Mr Robert Buchanan’s play “The New Don Quixote” has rather been increased than otherwise by the diplomatic letter which Mr Arthur Bourchier has written explaining that the licenser, Mr Redford, has courteously pointed out the nature of the official objection to the play in question. Mr Bourchier gives no hint of what the objection is, nor does he afford a single loophole for inference as to whether he agrees with it or otherwise, though the fact of his having in the first instance accepted the play for production is strong presumptive evidence that he saw nothing objectionable in it. The issue of the new play from the press is now being looked for with increased curiosity. ___

The Western Daily Press, Bristol (30 December, 1895 - p.3) Playgoers are at once disappointed and gratified by the intimation that “The New Don Quixote” has at last received the licence of the Lord Chamberlain. The dispute between Mr Robert Buchanan and the Licenser of Plays promised some pretty sport, and the present system of licensing is not so popular in some quarters, and the spectacle of a Philistine like Robert Buchanan taking up his club against it would have been relished. The date of the production of the play depends on the length of the run of “The Chill Widow,” which is still drawing good houses at the Royalty. ___

Pall Mall Gazette (31 December, 1895) THE CENSOR AND MR. BUCHANAN. A “PURE LOVE STORY.” MR. ARTHUR BOURCHIER INTERVIEWED. On Saturday the Reader of Plays at last withdrew his opposition to Mr. Robert Buchanan’s play, “A New Don Quixote,” which had been sent to him for licensing by Mr. Arthur Bourchier. Last night a Pall Mall reporter called upon Mr. Bourchier at the Royalty Theatre to endeavour to obtain the history of this incident, Mr. Redford’s first display of the cloven hoof of censorship. Mr. Bourchier was communicative—up to a point. He said: “Mr. Buchanan offered me the play. I liked it immensely, accepted it, and proceeded to arrange for the copyrighting of it, against the day I should want it. With two other plays, I sent this on to Mr. Redford. The other two came back licensed all right; but while they were taken this one was left. I was invited to go and see Mr. Redford, and he told me that Mr. Buchanan’s play could not be licensed in its then form. I could only plead that the situation in it was identical with that in certain other plays which had been licensed, but without avail.” MR. BUCHANAN NEXT WROTE TO MR. REDFORD, and the answer he got, which, I am bound to say, was perfectly justified and in order under the statute, was that the Reader of Plays does not recognize authors as such. The manager is the culprit, and so back again I went. Mr. Redford, Lord Lathom, and all of them were charming, and when I asked whether they would, supposing Mr. Buchanan consented to produce it, read another version of the same story, they readily expressed perfect willingness.” CALCULATED TO TICKLE THE STALLS. Nothing of the sort. It is a serious play. In my humble way I endeavoured to impress upon Mr. Redford that the theme was of the purest, dealing with the subject from a totally different point of view from that adopted in ‘The Second Mrs. Tanqueray,’ and so on.” ___

The Liverpool Mercury (31 December, 1895 - p.5) The licenser of plays has withdrawn his ban from Mr. Robert Buchanan’s drama “A New Don Quixote,” but it is now not likely to be seen at the Royalty till Easter. Whether Mr. Buchanan has modified the play so as to meet the scruples of Mr. Redford is not known, but it is probable that an accommodating spirit has been shown on both sides. Mr. Buchanan gains so much more by the good run of a piece which may not express in its acted form all he desires to delineate than he would gain by a quarrel with the licenser that discretion becomes the better part of valour. As the curiosity of the public will be set on edge by Mr. Redford’s interference, the little episode is certain to turn out to Mr. Buchanan’s pecuniary advantage. ___

The Leeds Mercury (1 January, 1896 - p.5) The reconciliation between Mr. Robert Buchanan and the Licenser of Plays (if one may really be permitted to put the thing in that way) seems to have been brought about, our London Correspondent says, by Mr. Buchanan swallowing some of his wrath and knocking out some of the lines of his play. At first he was exceedingly angry, and threatened all sorts of vague reprisals and mortifications for those who had crossed him, from the ornamental Lord Chamberlain down to the mysterious Mr. Redford; but the soothing influence of a manager may apparently be exerted with success on the most belligerent authors, and Mr. Buchanan has calmed down with a sweet completeness most appropriate to the Christmas season. Having written a problem play, the distinguishing characteristic of which is said to have been its “purity” and “ideality,” he has condescended to modify those misunderstood qualities so as to please the fastidious taste of the censor, who presumably, in the embarrassing multiplicity of problem plays, has got a little mixed in his appreciation of the cardinal virtues. However, all is well that ends well, and Mr. Buchanan and Mr. Redford are perhaps complacently disposed to wish each other a happy new year. The new play—it is not quite clear whether it is now invested with more or less “purity” and “ideality” than before—will be produced by Mr. Arthur Bourchier at the Royalty Theatre. ___

The Western Daily Press, Bristol (1 January, 1896 - p.9) It now transpires that Mr Arthur Bourchier played the part of guide, philosopher, and friend to Mr Robert Buchanan in the difficulty with the Lord Chamberlain over the licensing of “The New Don Quixote.” He actually induced that author to rewrite a scene, and only those who know Mr Buchanan can form even a faint idea of what a triumph in diplomacy that must have been. In the new play the great questions that hinge on the unhappy situation of a woman with a past are to be considered in their philosophical, social, and even their religious aspects. ___

The Globe (2 January, 1896 - p.6) “The New Don Quixote,” the play by Mr. Robert Buchanan which Mr. Arthur Bourchier will by and by produce at the Royalty, would probably have been christened “A Modern Don Quixote,” had that title not been already captured for the musical farce which Mr. Arthur Roberts brought out at the Strand in September, 1893. The notion of modern Quixotes was worked out several times in eighteenth century fiction—notably in “The Spiritual Quixote,” “The Female Quixote,” and “The Amiable Quixote.” We have also had, in drama, “Don Quixote the Second”—the sub-title of Dion Boucicault’s “Fox Hunt”—and likewise a “Don Quixote Junior.” There are infinite possibilities in the idea. ___

Pall Mall Gazette (2 January, 1896 - p.3) “MR. BUCHANAN AND THE CENSOR.” To the EDITOR of the PALL MALL GAZETTE. ___

The People (5 January, 1896 - p.6) Mr. Zangwill, like Miss Burney with her late brother’s comedy, has withdrawn his new piece from production, at any rate, for the present, at the Royalty, whose manager, Mr. Bourchier, has now arranged to bring out an original play, by Mr. Robert Buchanan, called “New Don Quixote,” in succession to “The Chili Widow,” probably at Easter. ___

The Glasgow Herald (6 January, 1896 - p.4) Mr Robert Buchanan is now altering the finale to the second act of “The New Don Quixote.” Certain details concerning this play are now gradually being disclosed. It seems that the heroine is another New Magdalene, or, otherwise, the hero, a clergyman, weds a lady of light reputation, mainly with the Quixotic object of reforming her. His love for her increases, although she after their marriage almost despises the man. The idea is undoubtedly a powerful one, and Mr Bourchier has declared the heroine’s character is not so bad as it is painted. ___

Northern Daily Mail (11 January, 1896 - p.6) Mr Buchanan’s play “A New Don Quixote” has at last been licensed by the Reader of Plays. Mr Redford, after reading the play, asked Mr Bourchier whether there was no way of modifying it, and Mr Bourchier’s answer was that he was the manager, and not the author, and that, therefore, it did not rest with him. Mr Buchanan next wrote to Mr Redford, and the answer he got was that the Reader of Plays does not recognise authors as such, the manager being considered the culprit. Mr Bourchier had an interview with Mr Redford and Lord Lathom, who, when asked whether they would, supposing Mr Buchanan consented to write it, read another version of the same story, readily expressed their willingness to do so. Mr Buchanan set to work and produced a new version—only altering the dialogue, and leaving the main situations untouched—and this was licensed last Saturday. Mr Bourchier has given his assurances that Mr Buchanan’s heroine is a pure woman at the commencement of the play; and we shall see during the action the reasons which drove her from her purity, the man in the case being a noble, high-minded fellow. The theme of the play is an argument about the real and ideal love, argued out between “The New Don Quixote” and his friend. The woman becomes soiled as the play progresses, but there is an art in the treatment of this part of the piece which still leaves it a pure love story—the man being an idealist. All this is somewhat bewildering; but is undoubtedly calculated to stimulate interest and curiosity about “The New Don Quixote.” ___

The World (New York) (12 January, 1896 - p.37) Some trouble was experienced in getting a license for the play, “The New Don Quixote,” which Robert Buchanan has written for Mr. Bourchier at the Royalty theater. This has now been satisfactorily arranged, and the comedy will be produced before Easter. ___

The Dundee Courier (3 February, 1896 - p.3) At several theatres changes in programme are impending. Mr Robert Buchanan’s play, “The New Don Quixote,” has gone into rehearsal at the Royalty, and in view of its early production the author has written an open letter to the licenser of plays criticising the interference which the piece originally met with from that official. “The Professor’s Love Story,” in which Mr Willard has made good his place in the front rank of English actors, has nearly reached the 250th performance, but is expected to run till Easter. ___

The Illustrated Sporting and Dramatic News (8 February, 1896 - p.11) NOT content with having defeated the Censor’s proposed prohibition of The New Don Quixote, its author, who dearly loves a fight, is about publishing an “open” letter on the subject. That letter will probably be the reverse of complimentary to the Examiner of Plays, who, however, will go on drawing his comfortable emoluments just as though the indignant epistle had never been penned. ___

St James’s Gazette (14 February, 1896 - p.12) At the Royalty “The Chili Widow,” although approaching its 200th representation, still shows plenty of vitality, and Mr. Arthur Bourchier consequently has been under no necessity to begin preparations for the production of a successor. In any case, this, it would appear, will not be “The New Don Quixote,” by Mr. Robert Buchanan and “Charles Marlowe,” as has been too hastily assumed. Mr. Bourchier has, in point of fact, several pieces on hand to which preference will be given. There is, for instance, his own adaptation of the German farce, “Der Rabenvater,” now nearly completed. He has, moreover, been fortunate enough to secure a powerful play from Mr. Herman Merivale, whose health, we are glad to say, has so much improved of late as to enable him to resume work. Mr. Bourchier further possesses a four-act drama by Mrs. Ramsey and Mr. de Cordova, whose little one-act play, “Monsieur de Paris,” he will, by the by, probably produce at Easter. ___

The Era (22 February, 1896 - p.12) A COPYRIGHT performance of The New Don Quixote, a play in four acts, by Robert Buchanan and Charles Marlowe, took place at the Royalty Theatre on Wednesday afternoon. The various acts were described as follows:—Act one—In which Don Quixote avows himself knight errant, and goes forth seeking adventures. Act two—In which Don Quixote tilts with windmills and rescues his fair lady from a dragon’s cave. Act three—In which Don Quixote and the fair lady go through an old-fashioned ceremony. Act four—In which Don Quixote breaks his lance, and wins a last victory without it. ___

The Bookman (March, 1896 - p.24-25) PLAY WRITERS AND PLAY CENSORS. . . . Quite recently a play by Robert Buchanan, entitled A New Don Quixote, incurred the displeasure of Lord Lathom, the present Lord Chamberlain. The play was announced for production at the London Royalty Theatre, of which Arthur Bourchier is manager. The theme of the play is an argument about the real and ideal love discussed between the new Don Quixote and his friend. The woman becomes soiled as the play progresses, but the author declares that his treatment of this part of the piece is such that the most prudish person could not object to it. But Mr. Redford, who reads the plays for the Lord Chamberlain, told Mr. Bourchier that the play must be altered; to which Mr. Bourchier answered that he was the manager and not the author, and that, therefore, the matter did not rest with him. Mr. Buchanan then wrote to Mr. Redford, who sent back the surprising reply that the Reader of Plays does not recognise authors as such, the manager being considered the culprit. Mr. Bourchier then had an interview with Mr. Redford and Lord Lathom, who, when asked whether they would, supposing Mr. Buchanan consented to write it, read another version of the same story, condescended to do so. Mr. Buchanan set to work and wrote a new version, only altering the dialogue and leaving the main situation untouched, and this was licensed a few weeks ago. ___

The Globe (30 April, 1896 - p.6) In the same issue of “The Theatre” Mr. Robert Buchanan discusses “The Ethics of Play-Licensing.” He fulminates not so much against the official censor, as against the condition of things of which he considers him the outcome. Mr. Buchanan describes for us the situation in his “New Don Quixote,” which (he says) caused the censor to refuse, in the first place, his approval of the piece. “A man marries a woman, and discovering, when they are alone together on the wedding night, that she does not love him, informs her that they must live apart, and be ‘husband and wife only in name,’ until such time as she cares for him as a wife should care for her husband. He goes to his room, she retires to hers, and the curtain falls.” The likeness which this situation bears to one in the “Maître de Forges” “The Ironmaster”) will be obvious to every playgoer. “The New Don Quixote,” it further appears, will not now be done at the Royalty. Mr. Bourchier wished to delay its production till the late autumn, but Mr. Buchanan and his collaborator preferred to withdraw their piece and accept a “forfeit.” “Mr. Bourchier,” says the former, “acted in the handsomest possible manner,” even to the extent of giving, free of charge, a copyright performance of the play. ___

Brooklyn Daily Eagle (26 July, 1896 - p.22) Arthur Bourchier, who is one of the impending English stars, will have a new play by Robert Buchanan, called “A New Don Quixote.” The heroine seems, from the outline of the plot, to acquire her past as the piece progresses and in full view of the audience. ___

The Standard (1 August, 1896 - p.3) |

|

|

The Omaha Sunday Bee (16 January, 1898 - p.1) LONDON, Jan. 15.—(New York World Cablegram—Special Telgram.)—George Alexander’s promised production, Paul Potter’s “Conquerors,” has provoked a fierce attack from Robert Buchanan, who has himself frequently come into conflict with the English censor, owing to the daring incursions into forbidden ground. Buchanan complains: [Note: ___

The Academy (10 December, 1898 - p.410) Announcement is made of a new novel by Mr. Robert Buchanan, to be called The New Don Quixote. Was this not the title of a play which he wrote and had arranged for Mr. Bourchier to produce, but about which there was some trouble with the Licenser? There is, by the way, a musical farce called “The Modern Don Quixote.” The “modernising” of Quixote has been rather a fad with out playwrights and novelists. Some of us have read The Spiritual Quixote of Richard Graves and The Female Quixote of Mrs. Lennox. Some of us have even perused a story still less familiar— The Amiable Quixote; or, the Enthusiasm of Friendship, which has for its central figure a young gentleman who “found in the slightest acquaintance some virtue or some recommendation.” There is also Mr. Justin McCarthy’s Donna Quixote. ___

The Dundee Advertiser (17 December, 1898 - p.8) A novel by Mr Robert Buchanan, provisionally entitled “The New Don Quixote,” will be published about March by Mr John Long. ___

The New York Times (7 January, 1899) [From William L. Alden’s ‘London Literary Letter’ - 26 December, 1898.] Now that the Christmas publishing season is virtually over there will be the usual lull in book publishing. A new novel from Mr. Robert Buchanan, to be called “A New Don Quixote,” is about the only announcement among new novels which deserves attention. There are rumors of a novel by Mr. Meredith in the Spring, and of course there will be the usual quantity of novels by Crockett, Guy Boothby, and the other unlimited purveyors of fiction. I doubt, however, if novel readers will have much that is both new and readable during the next six months. The advent of cheap magazines, with cheap serials, will have its effect lessening the year’s output of really good novels. ___

[Buchanan gave his account of the problems with The New Don Quixote in ‘The Ethics of Play-Licensing’, published in The Theatre on 1st May, 1896.]

Back to the Bibliography or the Plays _____

Mentions of an adaptation of Sarah Grand’s novel The Heavenly Twins stretch from February 1896 to August 1902 but there is no evidence that it ever reached completion, or the stage.

The Era (22 February, 1896) A PIECE called The Heavenly Twins will shortly be produced at a matinée at a London theatre. Mr John Douglass has been engaged to superintend and stage-manage the production. ___

The New York Times (8 March, 1896) A play called “The Heavenly Twins,” thought to be a dramatization of Sarah Grand’s novel, is soon to be tried at a matinée in London. ___

The Daily Telegraph (8 June, 1899 - p.7) Messrs. Robert Buchanan and “Charles Marlowe” have recently completed a new comedy, shortly to be produced in London and founded by arrangement with the authoress upon Madame Sarah Grand’s popular novel, “The Heavenly Twins.” The work is to a large extent original, alike in plot and characterisation, and has been planed out as a new drama with the entire approval of Madame Grand. ___

The Stage (15 June, 1899 - p.13) The new comedy, written by Robert Buchanan and Charles Marlowe, who have founded it, by permission of Sarah Grand, upon her novel “The Heavenly Twins,” will shortly be produced at a West-end theatre. Though “founded,” the play is, I understand, to a large extent quite original, both in plot and characterisation. ___

The Newcastle Courant (17 June, 1899 - p.5) Of all the sensational works of fiction which have created a momentary stir of late years, “The Heavenly Twins,” by Sarah Grand, would seem to offer the least opportunities for successful dramatic treatment, and yet we are promised a stage version of this preposterous novel in the course of a few weeks. Inasmuch as the adaptors are Robert Buchanan and “Charles Marlowe,” collaborators who are possessed of a wealth of experience in similar work, we may presume that they have been able to evolve a story with some dramatic power, but where they have been able to find it we are at a loss to imagine, and we therefore await the production with much curiosity. These same fellow workers have prepared a version of Dumas’ “Le Collier de la Reine,” in which Mrs Langtry will make her re-appearance on the stage. ___

The Referee (18 June 1899 - p.3) Another adaptation of “The Heavenly Twins” is imminent. This time the adapters are Robert Buchanan and “Charles Marlowe”—otherwise Harriet Jay. ___

Daily Express (8 May, 1900 - p.2) ON AND OFF THE STAGE. RE-ENTER: MISS ELLALINE TERRISS. Playgoers will learn with pleasure that Miss Ellaline Terriss, having concluded her season in New York, returns to London on the 22nd of this month. What will she do? The question, of course, is premature, but everybody will be anxious to know in what she will elect to appear. _____ Meanwhile, I hear of a play by Mr. Robert Buchanan, founded on an incident in Madame Sarah Grand’s “Heavenly Twins,”which would appear to offer the charming young actress an excellent opportunity. The play is of a domestic character, on the lines of “Sweet Lavender,”and introduces the girl and boy parts and the recluse—the organist—of the book. Readers of the book will recall the girl’s friendship for the musician, and her appearances as a boy. Has not Miss Terriss already delighted us in such a rôle in Mr. Pinero’s fresh-aired play at the Court—“The Amazons”? _____ Another play of Mr. Robert Buchanan’s, founded on Dumas’ book, “The Queen’s Necklace,” is to be produced by Mrs. Langtry, on her return. In this Mrs. Langtry will double the parts of the Queen and Gai d’Oliva. The big scene occurs in the ball-room—the last act—where the brilliant courtesan appears in the Queen’s necklace. ___

The New York Times (20 May, 1900) Robert Buchanan has written a play founded on the episode of the Boy and the Organist (and the Fried Eggs) in “The Heavenly Twins.” Presumably it will have a happy ending, the Organist marrying the Boy, who turns out to be a Girl and not to be already married, as in the book. The case of pneumonia, probably, will be omitted. They say in London that Ellaline Terriss will have the principal part in this piece. ___

The Observer (11 May, 1902 - p.6) An example of curious collaboration is to be provided shortly, though not as has been stated, at the Haymarket, in the joint work of Mrs. Craigie and Mr. Murray Carson, whose dramatic styles could not well differ more widely than they do. The play which these authors have written together is called The Bishop’s Move. Two other writers who are about to collaborate are Miss Harriet Jay—the “Charles Marlowe” of one or two promising stage ventures—and Madame Sarah Grand. It would be easy to imagine their achieving a popular success together. The Bishop’s Move is, by a novel arrangement, to be produced by Mr. and Mrs. Bourchier on the last night of their season at the Garrick, where they make way, on June 9, for Madame Sarah Bernhardt. The initial run of the comedy, which must thus be limited to a single performance, will be devoted to Queen Alexandra’s Soldiers’ and Sailors’ Fund. In this play Miss Jessie Bateman will make her first appearance in London since her recent engagement in America. ___

The New York Times (14 June, 1902) Mme. Sarah Grand, author of “Babs the Impossible,” has just completed a play in collaboration with Miss Harriet Jay, who is a sister-in-law of Robert Buchanan, who was a close friend of William Black at the time when the novelist was not so well known. Their friendship terminated on some trifling misunderstanding. In his biography of Black, Sir Wemyss Reid tells of the novelist’s devotion to work in those days, and of the young Scotsman’s refusal to see any of the sights of London before he had finished an article upon which he was at work. He is described as being at that time “a raw youth, dressed in a rather rough tweed suit, with Berlin-wool gloves on his hands and a hard felt hat on his head—a very different figure from that of the conventional city clerk.” ___

The New York Times (26 July, 1902) Madame Sarah Grand, who has done little in story writing since the publication of “Babs the Impossible” a year ago, is contemplating an early journey to the United States. Lately she has been working on a dramatization of “The Heavenly Twins,” which was begun by the late Robert Buchanan and carried forward by George H. Sims. ___

The New York Times (31 August, 1902) The disposition in favor of dramatized novels continues. ___

The Edinburgh Evening News (23 September, 1902 - p.6) ROBERT BUCHANAN’S PLAY, “THE HEAVENLY TWINS.”—The late Robert Buchanan’s play, “The Heavenly Twins,” may, it is understood, be seen at a special series of performances at the Savoy Theatre, London.

Back to the Bibliography or the Plays _____

Robert Buchanan’s Other Plays - continued

|

|

|

|

|

|

|