|

|

|

|

|

ROBERT WILLIAMS BUCHANAN (1841 - 1901)

|

|

|

|

THEATRE REVIEWS

34. The Struggle For Life (1890)

The Struggle For Life

by Robert Buchanan and Frederick Horner (an adaptation of the play, La Lutte pour la Vie by Alphonse Daudet).

London: Avenue Theatre. 25 September to 25 October, 1890.

The Referee (2 February, 1890 - p.3)

On Friday Robert Buchanan and Fred Horner entered into an agreement to collaborate in adapting “La Lutte pour la Vie,” the English rights of which are held by Horner, and are to be rented by Alexander for use at the Avenue. The date of production will be April 6, there or thereabouts, and the title will be “The Struggle for Life.”

___

The Era (8 February, 1890 - p.10)

MISS GENEVIEVE WARD and MR GEORGE ALEXANDER, having accepted the adaptation of La Lutte pour la vie, by Mr Robert Buchanan and Mr Fred. Horner, have purchased all rights of the English version from Mr Horner, and will produce it at the Avenue Theatre, themselves appearing in the principal parts.

___

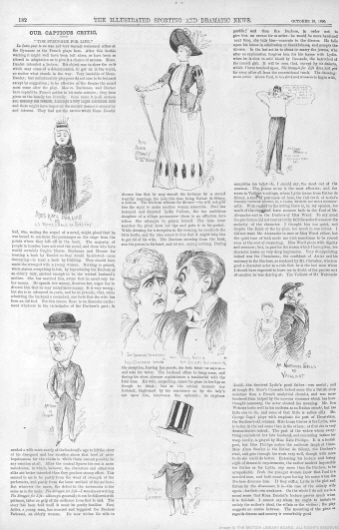

The Illustrated Sporting and Dramatic News (6 September, 1890 - p.9)

IT would seem from the fact that the original names of the dramatis personæ of La Lutte pour la Vie are to be retained at the Avenue, that the Horner-Buchanan adaptation will not attempt to Anglicise the action and the locale of the play. This will be just as well, for the whole tone and pseudo-philosophic motive of M. Daudet’s nineteenth century tragedy is essentially French, or rather essentially Parisian. Mr. George Alexander, who has generally hitherto played more or less lovable characters, will make a bold departure by appearing as the selfish, cold-blooded, egotistic scoundrel, Paul Astier; Miss Genevieve Ward will, of course, play the long-suffering elderly wife, and Mr. Albert Chevalier will have the important part of Chemineau, who has many characteristic things to say, though not very much to do. The cast will also include Miss Laura Graves, as Paul’s younger victim; Miss Kate Phillips, as La Maréchale; and Miss Alma Stanley, as Esther de Sélény. The first night of The Struggle for Life may be expected on or about the 20th inst.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

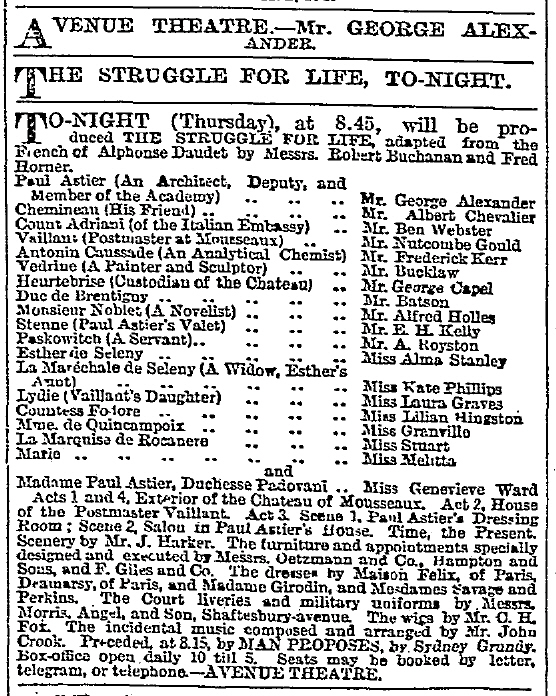

[Advert for The Struggle for Life from The Times (25 September, 1890).]

The Times (26 September, 1890 - p.7)

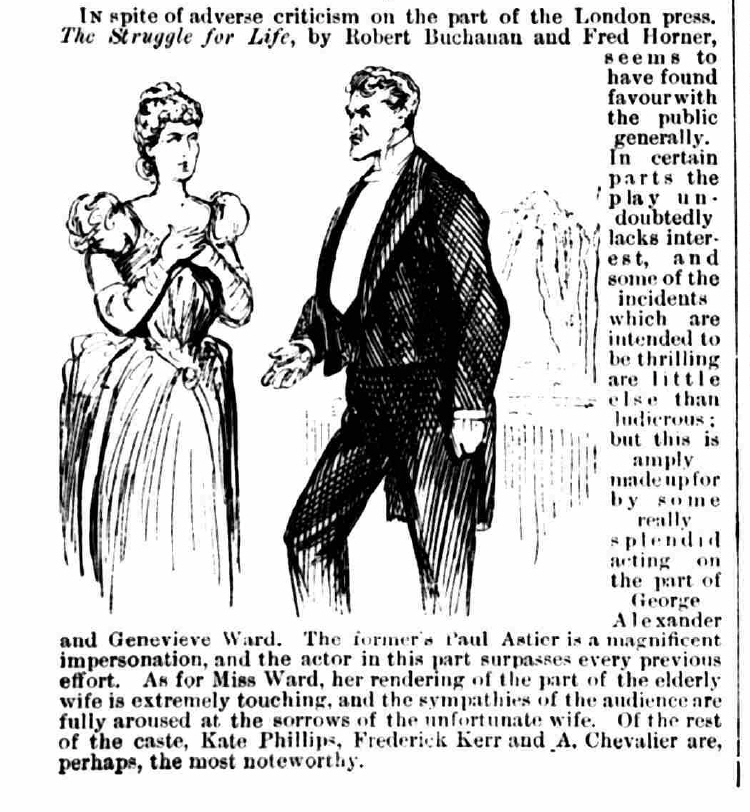

AVENUE THEATRE.

The adapters of M. Alphonse Daudet’s unfortunate play La Lutte pour la Vie have done him the signal service of cutting out his “Darwinism,” root and branch, and presenting his story as what it really is, a somewhat gloomy, but quite unpretentious, tragedy of the drawingroom type. It is still called The Struggle for Life, but this title is merely the trace of a disused faculty which has survived the evolutionary process of adaptation; it is the rudimentary tail, so to speak, which serves to remind us of the morphological changes effected in M. Daudet’s original scheme. Nothing of the Darwinian counterblast remains, and the name of the author of the “origin of Species” is not even mentioned in the dialogue. As before, the ruthless and cold-blooded Paul Astier is shot down in the last scene, but this retributory deed is no longer put forward as an application of la loi darwinienne; it is merely a rather commonplace act of poetic justice, such as the playwright was wont to permit himself long before Darwin was born. Relieved of its sham science, the piece is now at least a perfectly inoffensive production. Messrs. Robert Buchanan and F. Horner retain the French characters, and have borrowed most of M. Daudet’s ideas. They have, however, recast the story, and the action in its more compact form now passes comfortably within the space of two and a half hours. Being quite an hour shorter than the original, it would be rash to say that The Struggle for Life, apart from the Darwinian question, is not a considerable improvement upon M. Daudet. At the same time it is to be regretted that the adapters have not seen their way to brighten the action a little. The story is still, in an exceptionable degree, one of gloom and depression; for, by a curious fatality, even the one character supposed to provide “comic relief” is a young widow who is always ready to burst into tears for her “late lamented.” The really admirable features of this performance are the mounting and the acting. If the constitutional weaknesses of the play are past cure, Mr. George Alexander has spared no pains to give it a brave and attractive aspect. The gardens of the château and the salon, in which a large portion of the action passes, are among the prettiest and most tasteful “sets” to be seen on the stage. Mr. George Alexander’s own rendering of Paul Astier, with his detestable, but quite incontrovertible, doctrine that the weak must give way to the strong, will alone do much for the play; for the easy, cynical, polished, heartless man of the world of which Paul Astier is a sample has never found a better exponent. The part of the elderly wife, who is a mill stone round the neck of her too ambitious husband, was a triumph for Mme. Pasca at the Gymnase; it is now no less so to Miss Genevieve Ward, who unfalteringly sustains her share of the burden of the play. Happily, too, a very sympathetic victim of Paul Astier’s heartlessness has been found in Miss Laura Graves; while her humble sweetheart, with an unprepossessing exterior but a brave and loyal heart, is depicted with rare skill by Mr. Frederick Kerr. As the father of the hapless Lydie, Mr. Nutcombe Gould is hardly seen at his best, but the character is one which in any case is more to the taste of a French than an English audience. This the adapters have perceived. In the French play, by virtue of his paternal character, it is Vaillant who is charged with the duty of exterminating his daughter’s seducer. That duty, in the English version, is more appropriately transferred to the betrayed lover—a change which is to be credited to the authors as a distinct improvement. Mr. Chevalier plays Paul Astier’s fussy friend Chemineau, and Miss Alma Stanley, Mr. Ben Webster, and others form a picturesque group of fashionable “types.”

___

The Daily News (26 September, 1890)

THE DRAMA.

_____

“THE STRUGGLE FOR LIFE” AT THE AVENUE.

The change from the light-hearted gaiety of “Dr. Bill” to the depressing sadness of M. Daudet’s drama “La Lutte pour la Vie” at the Avenue Theatre, is somewhat abrupt and violent; but the objection to Messrs. Buchanan and Horner’s adaptation of this gloomy piece lies somewhat deeper than this. It was not the absurdity of the indictment of Darwinism; neither was it exactly the sombre nature of the story that weighed upon the spirits of the audience during the performance of “The Struggle for Life” last night. It was rather the insincerity of the treatment of the theme. The dramatists have shown some skill and tact in compressing the first two acts into one and transposing somewhat the method of the original; but equal praise cannot be accorded to some other of the liberties taken with the French play. The last act, which is made to pass in the grounds of the Duchess’s chateau where Paul Astier is slain, not by the outraged father of Lydie, but by her milksop lover Caussade, is certainly not an improvement upon the auction scene. The tedious prolongation of this scene, and the manifest incongruities with which it is burdened, fairly broke down the patience of the spectators, and the curtain finally descended amidst manifestations of dissatisfaction which though they mingled with the more courteous demonstrations of a first-night audience, were not to be mistaken. The result was the more to be deplored because Mr. George Alexander’s Paul Astier presented many fine traits, and Miss Genevieve Ward has never acted with more force and effect than she did last night in the character of Madame Astier. The play was preceded by Mr. Sydney Grundy’s sprightly comedietta “Man Proposes,” which was acted with much spirit and cleverness by Mr. Ben Webster, Miss Marie Linden, and Miss Lilian Hingston.

___

The Pall Mall Gazette (26 September, 1890)

The Theatres.

“THE STRUGGLE FOR LIFE” AT THE AVENUE THEATRE.

If Mr. George Alexander was not able to record a complete managerial triumph last night, he may surely be credited with having achieved a remarkable and decided histrionic success. “The Struggle for Life” may not be the most satisfactory path for a comparatively young actor to take in his progress towards perfection in his art; but, for all that, there will be few who will fail to recognize in Mr. Alexander’s Paul Astier a degree of strength, independence, and creative power, which we have rarely seen in his previous work. To Miss Genevieve Ward, too, the occasion offered an opportunity, of which the actress did not fail to avail herself. In fact, she fairly divided the honours of the evening with Mr. Alexander, making her audience wonder from first to last how it is that her appearances on our metropolitan “boards” of late have been so few and far between.

Every one who witnessed Alphonse Daudet’s curious drama, “La Lutte pour la Vie,” must have realized the difficulties that would stand in the way of its transplantation to the English stage. Even Mr. Robert Buchanan and Mr. Fred Horner, who are jointly responsible for the adaptation produced last night at the Avenue Theatre, cannot have helped feeling that they were undertaking no light task when they set themselves to make so risky and repulsive a subject tolerable in the eyes of a London audience. A hero who is the personification of villainy and cowardice, and a heroine who has committed the offences—not easily condoned by the exacting playgoer—of attaining middle age and marrying a man well-nigh young enough to be her son, do not form the safest dramatic foundation in the world. One only wonders that the authors of “The Struggle for Life” have been able to place before us so clear and concise a version of the piece. Messrs. Buchanan and Horner have found it impossible to remove all the fundamental weaknesses of the story; but they have, at any rate, done the next best thing in compressing the action, reducing Daudet’s quasi-philosophical generalities to a minimum, and concentrating as far as possible an interest which the French author was content to make shifting and uncertain in its character. It is hardly necessary at this time to dive very deep into the details of a plot which has been so fully discussed on previous occasions. Suffice it to say that in almost all material respects the main story of the play is unchanged.

The two scenes at the close of the first and third acts stand out with striking vividness, played as they are by Mr. Alexander and Miss Ward. The earlier one, where Astier persuades his wife to forget his infidelities and return with him to Paris, is perhaps more satisfactory and convincing by reason of its greater truth to nature. Still, the tragic intensity of the poison episode was never relaxed by either actor or actress, who, as we have already said, may both claim to have accomplished a tour de force which was all the more striking when the quality of the material at their command was taken into consideration.

The play, it must be confessed, loses a good many of its subordinate effects through the rather unpolished rendering of some of the minor characters. Mr. Albert Chevalier, excellent comedian as he is in congenial rôles, is hardly an ideal Chemineau. Mr. Nutcombe Gould makes the injured postmaster Vaillant a needlessly “doddering” individual; while Mr. George Capel is clearly out of place as the old custodian of the château. Mr. Frederick Kerr has an excessively difficult part to play in Antonin Caussade; and, if he fails to arrive at the full force of the situation at the end of the second act, he deserves credit for the many careful details and evidences of thought in his performance. Miss Alma Stanley and Miss Laura Graves are rather overweighted as Esther and Lydie, though they both have their good moments. Mr. Bucklaw plays a “filling-in” part pleasantly enough, while Mr. Ben Webster and Miss Kate Phillips give two fairly neat character sketches. Mr. Harker’s scenery is most suitable and picturesque.

___

The Morning Post (26 September, 1890 - p.5)

AVENUE THEATRE.

_____

The long-promised adaptation by Messrs. Robert Buchanan and Fred Horner from M. Alphonse Daudet’s play, “La Lutte pour la Vie,” was produced by Mr. George Alexander last night, in the presence of an audience deeply interested in this dramatic experiment. “The Struggle for Life,” when played before a brilliant audience at the Gymnase, Paris, in October last year, was regarded as an illustration of the Darwinian theory under stage treatment. The “survival of the fittest” was, however, in the Parisian piece as rather the survival, or the triumph, of the least scrupulous. But while the wits and savants of the French capital might discover a vein of satire underlying the incidents and shaping the motives of the characters, London playgoers will be influenced rather by the purely dramatic qualities of the piece, and will not be likely to judge it by any philosophic standard. The hero, Paul Astier, is an architect, Deputy, and member of the Academy, unscrupulous in his ambition, and selfish in his nature. Amongst other methods of worldly advancement, he turns his attention to marriage as the readiest plan for rising in the social scale. Good-looking and plausible in his manner, Paul Astier is well aware that it will not be difficult to find favour in the eyes of the fairer sex, especially with those whose youth has passed. he has through his profession as an architect become acquainted with the Duchess Maria Antonia Padovani while superintending the restoration of her chateau at Mousseaux, and the duchess, attracted by his appearance and manners, falls in love with Astier and becomes his wife. But Paul soon tires of the lady, who is many years his senior. He cares only for her splendid fortune, and soon reduces it to such an extent that there is little left of the once princely income his wife possessed. He is a profligate also, and a gentle girl, Lydie Vaillant, falls a victim to his passion. His wife is almost heartbroken by his conduct, but Astier still makes use of her influence to raise his position. Being elected Deputy, he aspires also to be a Minister of State. At this juncture he makes the acquaintance of a young, beautiful, and enormously-wealthy Austrian Jewess, Esther de Sélény, who would become his wife if he could induce the Duchess to consent to a divorce. This she will not do, and repulses with scorn Astier’s emissary. Paul, however, confident in his own persuasive powers and utterly reckless as to the means so that the end is gained, visits the Duchess himself, with the intention of using all the influence he still possesses to bring about the divorce. The Duchess, despising him for his profligacy, still loves him, and when he uses all the arts of cajolery for the sole purpose of eventually carrying out his set purpose, she has the womanly weakness to believe that he has yet some tenderness for her. meanwhile, Paul continues to make advances to Esther de Sélény, who, when the château is thrown open to visitors, pays a visit to Mousseaux for the purpose of seeing the Duchess. The story of poor Lydie, his victim, is continued, and the tragic despair of the unhappy girl only serves to irritate Paul owing to the scandal it may possibly cause. She has attempted to take poison, and it suggests to Astier a diabolical idea—that of getting rid of the Duchess by poison instead of divorce. Repulsive as the suggestion is, it leads to a striking dramatic situation. Visiting the duchess, who complains of not feeling well, the villain pours a few drops of poison into a glass of water; but he has not the hardihood required for deliberate murder, and his confusion betrays him. The Duchess not only suspects him, but overwhelms him with her scorn, reminding him that he owed everything to her—that she had given him position, fortune, and the chances of rising to a prominent place in the world, but this last outrage has reached a climax. She at length consents to the divorce for which he had so long schemed and plotted in vain. In the closing scenes of this strange play Paul appears triumphant for a time, having gained the divorce, the Duchess having retired owing to the sale of the château, which has been purchased by Esther de Sélény. Paul Astier is present, exulting in the success of his plans, but an avenger is there. The lover of Lydie Vaillant, who died soon after her attempt to commit suicide, shoots Astier in the moment of his triumph. Such is the outline of the play as constructed by M. Alphonse Daudet, but beyond these incidents there were a host of others, some mere episodes introduced to give emphasis to the character of the hero, which, as will be seen, is far from being heroic. The essentially French tone of some of the incidents has been modified by Messrs. Buchanan and Horner with manifest advantage in a drama destined for English playgoers, who enter into no philosophical or scientific questions, but simply take “The Struggle for Life” on its dramatic merits. There are many situations and scenes in the drama which move the audience deeply. The “struggle for life” of the Duchess, Paul Astier’s wife, is, for example, one with which the audience can thoroughly sympathise. The regrets of a cultured and high-born woman, who has hoped against hope to gain and secure the affection of a man outwardly attractive and interesting, but inwardly selfish and worthless, is strongly and naturally depicted by the dramatist, and is true to human nature. The ambitious aims of the wealthy Esther, who makes her passion the excuse for her want of feeling, and the tender, simple-minded Lydie, equally deceived by her lover, like the other women who confide in him, are well drawn and effectively contrasted, and it is impossible not to take interest in their actions. The drama is well written, and the condensation of the five acts of the original into four adds to its strength considerably, and enables the adaptors to dispense with some episodes which would have but slight attraction for an English audience. Many will be repelled by the character of the hero, so unscrupulous and inhuman. Some scenes are modified, but nothing can render Paul Astier a personage to admire or even to excuse. We must take him as he is, and look forward to his ultimate fate as an act of justice long delayed but inevitable. It was pleasant to see Mr. George Alexander once more playing a part worthy of his ability. he made it important in every way; and no matter what we might feel as to the motives and actions of Paul Astier, they were so admirably indicated by the actor that the character became a singularly interesting study. Ambition, selfishness, and passion have seldom been depicted with greater force and subtlety by any of our younger actors. Mr. Alexander has unquestionably raised himself a step higher as an artist, and has made an advance in popularity by the skill displayed in this repulsive but striking character. Mr. Albert Chevalier, as Chemineau, the parasite and toady, acted with no little cleverness. The character of this creature is, perhaps, made somewhat too transparent, but in other respects there was much to commend. Mr. Ben Webster played Count Adriani, of the Italian Embassy, with the ease and brightness of style required. Mr. Nutcombe Gould gave no little dignity and pathos to the character of the simple postmaster Vaillant. His acting was direct and forcible and his manner sympathetic. Mr. Frederick Kerr, as the chemist Caussade, had not much to do, but he was artistic and effective. Mr. George Capel, as the custodian of the château, and Mr. Bucklaw, as Védrine, the painter and sculptor, were also efficient; and the smaller parts were represented with due care. The commanding figure and stately air of Miss Alma Stanley well qualified her to be the representative of the passionate and ambitious Esther de Sélény. The part demands strength rather than subtlety, energy rather than delicacy. Miss Stanley evidently comprehended the character, and played it in a well- balanced and effective manner. Miss Kate Phillips always makes a little part attractive by her ability and intelligence, and she was as excellent as usual in representing Esther’s aunt. Miss Laura Graves was tender, graceful, and pathetic as Lydie Vaillant, the postmaster’s daughter, and Miss Lilian Hingston was to be commended as the Countess Fodore. The little part of Madame Quincampoix was played by Miss Granville with skill and intelligence, justifying the belief that the young lady will be an acquisition to the stage; Miss Stuart and Miss Melitta acted satisfactorily. The most striking figure among the feminine characters was Miss Genevieve Ward as Madame Paul Astier (Duchess de Padovani). Miss Genevieve Ward’s ability and experience enabled her to invest this character with remarkable attraction and interest. She awakened the deepest sympathy for the unhappy wife, and her demeanour in the principal scenes had a dignity and quiet power revealing womanly feeling and artistic perception of no ordinary kind. Miss Ward’s tragic abilities were admirably employed in the great scene with Paul Astier, which was given with the full strength the situation demanded, and made a vivid impression. Miss Ward’s acting of this character is unquestionably one of the most striking features of the drama. Mr. Alexander has placed the play upon the stage with lavish expenditure. The surroundings are rich and tasteful, and the dramatic picture is heightened by the splendour of its accessories. The reception of the drama was enthusiastic, the adaptors and principal performers being cordially complimented at the close.

___

The Standard (26 September, 1890 - p.3)

AVENUE THEATRE.

_____

The impression created by M. Daudet’s drama, La Lutte pour la Vie, in Paris ensured its production in London, and, indeed, it would have been seen some months ago had not Dr. Bill achieved a success which was possibly somewhat unexpected. Last night, however, the adaptation of the now famous French work was produced by Mr. Alexander, with results which, on the whole, must be described as distinctly fortunate. The authors, Messrs. Robert Buchanan and F. Horner, have appended a note to the programme to state that The Struggle for Life, as the English version is called, is “in every sense of the word, an adaptation, not a translation,” and that “great changes have been made in both dialogue and plot.” Changes no doubt have been made, but they are not, in reality, of a very important character. The relationship of Esther de Sélény and Paul Astier is somewhat modified, and it is Antonin Caussade, the betrothed of Lydie Vaillant, who kills Astier, not his victim’s father; but these variations do not affect the real structure of the play, and if alterations have been made in some cases, in may others the original is very closely followed—not always actually in dialogue, but in the main lines and incidents of the story. M. Daudet’s work has the valuable quality of retaining interest and exciting curiosity. The plot is not of that obvious nature that, when the first half has been seen, the remaining half can be guessed. It may not please all spectators; but none will deny its originality and force, and, doubtless, it will create much discussion—one of the most serviceable advertisements a play can have. But happily for the audience, a great deal of the argument and philosophy which encumbered the original has been removed bodily—a most judicious proceeding on the part of the adapters, for this was very tedious in the French, and, as it seemed to English taste, out of place on the stage. M. Daudet’s story possesses one of the greatest merits a play can have—it can be related in a very few words. Omitting detail, The Struggle for Life is simply this—Paul Astier, clever and ambitious, has married the Duchess Padovani to obtain wealth and position. He never loved her. She is twenty years older than he, and, having spent her fortune, and won his way in politics and Society, he wants to get rid of her and marry Esther de Sélény, who is young and rich. He has meantime betrayed an innocent girl, Lydie Vaillant, whose betrothed (in the English play) shoots Astier at the moment when his plots and schemes appear to be crowned with success; for the Duchess consents to a divorce after he has made a half-hearted attempt to poison her, and when Esther has forgiven his faithlessness. A plot which can be thus successfully set forth, if it have novelty and freshness, is generally striking and effective, and this is the case with the adaptation, the strength of which is concentrated by the omission of the large amount of dialogue, which had no bearing on the actual plot.

If it was a somewhat bold step on the part of Mr. Alexander to call forth comparison with the original company by which the work was presented, and, in fact, for which it was written, the result goes far to justify the venture. The Struggle for Life is extremely well acted, the manager of the Avenue evidently having the wit to suit himself, and to choose a company with judgment and foresight. For Mr. Alexander the part of Paul Astier is a breaking of new ground. He has scarcely ever been seen in the representation of an unsympathetic character, and Astier is a most cold-blooded and unmitigated villain. It must be played, nevertheless, by an actor who has charm and ease of manner, and distinction of bearing—there must be something to explain Astier’s general ascendancy, and this Mr. Alexander most skilfully exhibits. The part affords striking opportunities, and the actor takes full advantage of them. There is something irresistibly plausible in his reconciliation with the Duchess, and he is most judicious in not overdoing the hypocrisy by asides which would be worse than unnecessary. Miss Genevieve Ward, as the Duchess, admirably fulfils her share of a difficult task. The man has a fascination for her before which her pride and just resentment give way; she struggles against the disposition to yield, but finally succumbs, and all this is indicated with great art. Her simple, earnest cry, “Be honest with me for once,” was certainly in the right key. Miss Alma Stanley, as Esther de Sélény, was somewhat deficient in refinement and finesse, but there was cleverness in her representation of the part, and she did well in the interview with Lydie—played with taste and feeling by Miss Laura Graves—when Esther reveals her secret to her humble friend, confesses that she loves Paul Astier, and refers to his intrigue with “one of those creatures whom men don’t marry,” little dreaming that it is to Paul’s victim she speaks. The scene of the attempted murder is very powerfully played by Mr. Alexander and Miss Ward, though it is open to question whether Paul is not rather too deliberate. he has made up his mind to put the remains of the poison with which Lydie has attempted her life into the glass of water for which his wife asks, and, this being so, he hesitates unduly; but the culmination is thrilling, and Miss Ward’s pathos is deeply touching as the Duchess tears from her heart the lingering affection she still feels, and consents to free him by the divorce he seeks, since she has become an intolerable burden. That Mr. Alexander can pourtray remorseless cruelty with a touch at once so fine and strong will astonish those who have hitherto associated him with such totally different parts. A marked success was made by Miss Kate Phillips as La Maréchale, the widow who so constantly, for a time, laments her late husband. Perhaps M. Daudet is not acquainted with Money, and does not know that his Maréchale is a reproduction of Lady Franklin in that comedy. The sameness of the widow’s plaint might grow monotonous in less able hands than those of Miss Phillips, who is not only humorous, but discriminating, and makes the character fresh and entertaining. The father of Lydie is played with sincerity and discretion by Mr. Nutcombe Gould, and Mr. F. Kerr presents a particularly well- considered study of Lydie’s diffident lover. As already remarked, ti is he who shoots Astier. The auction scene of the original is omitted; Antonin interrupts the reconciliation of the lovers to announce M. Vaillant’s death on his daughter’s grave, and then, drawing a revolver, he quotes Astier’s doctrine of the survival of the strongest, and kills him. Mr. Chevalier is tolerably amusing as Chemineau, Mr. Ben Webster gives a clever sketch of the Count Adriani, and Mr. Bucklaw acquits himself well as Vedrine. The play was very cordially received, all the usual tokens of success attending the fall of the curtain.

___

The Daily Telegraph (26 September, 1890 - p.3)

AVENUE THEATRE.

“The Struggle for Life” was with the unfortunate actors and actresses last evening. Never was there such a record-braking of reputations. From one end of the performance to the other there was a sense of effort; a straining with no result whatever; an heroic resolve to do the impossible. As curtain after curtain fell, and scene succeeded scene, the question forced itself upon even the most lenient and charitable, “Cui Bono?” What was the good of it all? Who on earth wanted Daudet’s “La Lutte pour la Vie,” a bad play and an absurdly overstated case, viewed from the most charitable standpoint. In France we had a clever novel turned into an indifferent play, and only redeemed from failure by the skill of the performers. Here we have a play even worse and more uninteresting than the original, handicapped by performances that, with one or two honourable exceptions, are little less than ludicrous. Let us be candid, for our acting is generally so good nowadays that we can afford to be so. We laugh at Frenchmen for their ridiculous travesties of English life, English habits, and English manners. But, honestly, have not Frenchmen a right to laugh at the caricatures that were represented on the stage last night? With the exception, the praiseworthy and honourable exception, of Miss Genevieve Ward and Mr. George Alexander, no one appeared to have got nearer to Paris than the Charing-cross Railway Station. Even in burlesque there were never seen such cardboard Gauls. We roar at the French actor for representing the Englishman with long Dundreary whiskers and check tourist suit; but with such Frenchmen, such Italians, such old-fashioned Adelphi guests the cultured Frenchman has every right to turn the tables on us and to repay our sarcastic smiles with interest. The curious part of it was that the cleverest of the young school of actors made the most astounding mistakes. Mr. Albert Chevalier is accounted a funny actor; but was ever such a Frenchman as “Chemineau, his friend,” seen out of an illustrated comic periodical? Chemineau is the original play is a type of Parisian “fin de siècle” young man. He is the companion of a dandy, a man who wants to go the pace, but has not the brains to do it. Chemineau, we repeat, is a type well known and understood by all Parisians. But Mr. Albert Chevalier is a type of no Frenchman under heaven. He thinks he becomes a Parisian by wearing ill-cut clothes and a hat that John Leech caricatured so far back as the English Exhibition of 1851. We assure Mr. Albert Chevalier that the Chemineaus of to-day have their clothes made in Sackville-street and wear hats that Bond-street would not be ashamed of. Take again the old servitor Heurtebrise, the custodian of the château, a type of servant as well known in France as an ancestral butler is in England. Mr. George Capel’s custodian has wandered out of some French extravaganza done into English in the Strand district. The whole value, dramatically speaking, of the character is that it is a type. Mr. George Capel makes it English to the backbone. But these things are pardonable. It is expecting too much to hope for such art as will make the minor characters in an adapted French play perfect.

In several pathetic characters, however, it was not expected that anyone could go wrong. The little postmaster’s daughter, who is ruined by the selfish Paul Astier; the simple-minded old postmaster himself, whose heart is broken owing to his daughter’s shame; the stuttering analytical chemist, who loves a girl in spite of her disgrace—all these are simple, easily drawn human characters. There was nothing “fin de siècle” about them. They were as plain sailing as any characters could well be. We saw them played at her Majesty’s Theatre recently indifferently well, but they all made their mark because they were human. Every scrap of nature was taken out of them by Mr. Nutcombe Gould, Mr. F. Kerr, and Miss Laura Graves, although two of these artists, at least, have shown again and again very remarkable talent. Mr. Nutcombe Gould, as the old postmaster, was no character at all. He was neither comic nor pathetic. He touched neither stop. He was wholly out of his element, and never got near the type of man he was intended to represent. Mr. F. Kerr’s chemist was incomprehensible. He tried to do too much, and succeeded in doing nothing. It was more like the village Softy or daft Billy in an old-fashioned melodrama than a modern French analytical chemist, who stuttered but had a good heart. There was nothing particularly weird or Softy-like in Caussade as we saw him in the original. He seemed a very natural and interesting type of young man. But when Mr. F. Kerr stammered over his woes the audience was unconvinced; when he shot the selfish scoundrel like the “idiot witness” of melodrama, the spectators simply laughed. And what shall we say of Count Adriana, of the Italian Embassy, who wears a scarlet uniform—unheard of in Italy—and thinks he becomes Italian by saying “simpatica” and “Gran Dio,” and interlarding choice English with Italian words borrowed from popular songs? Why, he is as much of an Italian as the fashionable Frenchman who talks of a “char-teau.” Mr. Webster has done far better things in his career than this Italian ambassador in a scarlet uniform, who looks if possible less of an Italian in full fig than in mufti. Nor was that clever actress Miss Alma Stanley a bit like the ambitious Esther de Sélény—the proud, handsome Jewess, who brings the selfish Paul Astier to his shame. The actress struggled to be like the Esther of the play, but the struggle was too apparent. She did not get near the woman she hopelessly tried to personate. For an intelligent artist like Miss Kate Phillips as La Maréchale De Sélény doomed to play a female “Graves,” and to lament her lost Field Marshal, there could only be a feeling of profound pity. The joke, such as it was, soon became threadbare. There was very little “nap” on the character when it started, but it was worn out in five minutes. For Miss Kate Phillips not to make her audience laugh would be impossible, but no one knows better than herself that she was no more like a Frenchwoman than was Mr. Chevalier like a Frenchman. They had neither of them ever been even to Boulogne.

So, amidst all this strained, unnatural, and anti-Gallic surrounding, what could Miss Genevieve Ward and Mr. George Alexander do but tower head and shoulders above their fellows, and attempt by good acting to interest their audience in an overstrained and unnatural theme. M. Alphonse Daudet wants us to believe that Madame Paul Astier, Duchess Padovani, who is a woman of the world, and has been twice married, is so infatuated with her second youthful spouse, that she is Christian enough to forgive him when he has deliberately poisoned her cup of cold water. The infidelity, the cruelty, the heartlessness, the unblushing vulgarity of Paul Astier’s amours are forgiven, as a matter of course, by his infatuated Duchess who supplies him with fresh cash for new mistresses. But Madame Astier does not draw the line at strychnine. She is able to throw the poisoned cup into the shrubbery, to moralise, and to forgive. We ventured to think at the outset that M. Daudet had overstated his case. An ill-used woman need not be a fool, and it is the act of a fool to forgive a cowardly murderer because he is clumsy enough not to succeed. “Once bitten, twice shy,” the saying has it, but Madame Paul Astier would forgive her pet scoundrel though his dagger had been plunged into her heart. Miss Genevieve Ward did all that art could do to make Madame Paul Astier convincing, but we feel sure that the majority of the audience remained unconvinced. She spoke her lines admirably; she looked the part to perfection. She, gifted as she is, made no mistakes in pronunciation or characterisation. She was a well-bred woman, and looked like a duchess, but the finest acting in the world would not make Madame Paul Astier an interesting woman. She has nothing to excuse her. She does not profess even to be hypnotised by her scoundrel of a husband. No wonder indeed that men are such dastards when clever women are such fools. The existence of an indomitable passion—which Madame Astier does not confess to—would scarcely justify a wife forgiving her husband who had poisoned her brandy and water. The case of female tolerance as against male selfishness is exaggerated and overstrained. Miss Genevieve Ward does her very utmost to win our sympathies for the injured wife, but she is, after all, too foolish to extract much pity. It is, indeed, “turning the other cheek” with a vengeance when the boy husband with a plentiful supply of mistresses cannot keep his hands out of the medicine chest. Admirably also did Mr. George Alexander try to elevate into dramatic importance this cheap and vulgar scoundrel, Paul Astier. He was easy, suave, fascinating, and occasionally so convincing in his monstrosity as to be positively dangerous. The satire of Paul Astier is so subtle that his villainy may assume the air of heroism. The actor is so delightfully insinuating and persuasive that we seem to forgive his treachery, his falsehoods, his mistresses, and his knowledge of toxicology. This, no doubt, is the last thing that M. Alphonse Daudet wishes. The author will urge that he kills his fascinating hero like a rat before the curtain falls. Vengeance is at hand in the cowardly pistol of the mad analytical chemist. But that pistol shot, be it remarked, comes a little too late. Paul Astier has worked his mischief long before the deus ex machina arrives, and we are not at all sure that there are not sympathetic heart-beats for the handsome blackguard when he cajoles Lydia, hoodwinks the Jewess, and brings his miserable old wife into a state of befooled frenzy. The better Paul Astier is played the more revolting the play becomes, for in proportion to his fascination so is he forgiven by acclamation. Mr. Alexander played this mean wretch with such effect that many seemed quite angry when Paul Astier was shot. Mr. Buchanan and Mr. Horner have, perhaps, necessarily cut and carved the play, but their omissions have not made it more palatable, nor their additions rendered it more intelligible. From the French point of view it had a certain exaggerated interest. From the English point of view it has none whatever. There may be Paul Astiers in London, but certainly no Madame Astiers in any form of English society. Injured wives forgive infidelity, but they do not condone murder. But the moral and ethical question wholly apart, surely Daudet’s “La Lutte pour la Vie” was ab initio a bad play. The English authors and artists have not succeeded in making it a better one. At least, that seemed the impression last night, when a patient and tolerant audience were provoked to signs of disapproval, even after Mr. George Alexander’s clever death scene. The whole thing was unreal, and no acting in the world will make this particular play anything else. The adaptors received, however, a complimentary call; but it would be rash to speculate on a long career for “The Struggle for Life.”

___

The Era (27 September, 1890)

THE AVENUE.

_____

On Thursday, Sept. 25th, a Modern Drama, in Four Acts,

Adapted from Alphonse Daudet’s “La Lutte pour la Vie,”

by Robert Buchanan and Fred. Horner, entitled

“THE STRUGGLE FOR LIFE.”

Paul Astier ... ... ... Mr GEORGE ALEXANDER

Chemineau ... ... ... Mr ALBERT CHEVALIER

Count Adriani ... ... Mr BEN WEBSTER

Vaillant ... ... ... Mr NUTCOMBE GOULD

Antonin Caussade ... ... Mr FREDERICK KERR

Védrine ... ... ... Mr BUCKLAW

Heurtebise ... ... ... Mr GEORGE CAPEL

Duc De Brétigny ... ... Mr BATSON

Monsieur Noblet ... ... Mr ALFRED HOLLES

Stenne ... ... ... Mr E. H. KELLY

Paskowitch ... ... ... Mr A. ROYSTON

Esther De Sélény ... ... Miss ALMA STANLEY

La Maréchale De Sélény ... Miss KATE PHILLIPS

Lydie ... ... ... Miss LAURA GRAVES

Countess Fodore ... ... Miss LILIAN HINGSTON

Madame De Quincampoix ... Miss GRANVILLE

La Marquise De Rocanère ... Miss STUART

Marie ... ... ... Miss MELITTA

Madame Paul Astier ... Miss GENEVIEVE WARD

From the time that the playgoing world was informed than an English version of La Lutte pour la Vie was underlined for production at the Avenue, curiosity has been rife as to what Messrs Buchanan and Horner would make of M. Daudet, and what Mr Alexander’s company would make of a play written for a vastly different school of performers. The answers provided for these two questions by Thursday night’s performance are not identical. The players on the whole have done fairly well; Messrs Buchanan and Horner uncommonly ill. But everything in its turn. Let us deal first with the adaptors. We use the right word, for Messrs Buchanan and Horner are careful to point out that their play is an adaptation, and in no sense a translation of the original. In the many alterations which have been made, it is easy to see what has been their guiding principle. They have had their eye all the time upon what are conventionally supposed to be the hard-and-fast requirements of the British playgoer—conventionally supposed, because we are not all sure that the ideas current in green-rooms and managerial offices about the supposed needs of the playgoer in question are justified by strict and recent observation. Be that as it may, it is for this fearful and wonderful playgoer of the “mind’s eye” that Mr Buchanan and Mr Horner have catered. The British playgoer is supposed, rightly or wrongly, to dislike impropriety on the stage—outside the regions of burlesque. This consideration at once condemns M. Daudet’s first act, which is so naughty as to exhibit to the public gaze a young woman emerging from a bedroom in bare shoulders and dishevelled hair. Nothing, of course, so shocking as this is to be seen at the Avenue. It is true that with the abolition of M. Daudet’s first act the exposition of the story is practically spoiled. We are no longer plunged in media res; no longer see at a glance, five minutes after the rising of the curtain, what a brute Paul Astier is, and how he has determined, by the most scandalous means, to wring a divorce from the duchess, his wife. But the British playgoer’s blushes are spared, so it is no good crying over spilt milk, or vanished first acts.

In serious situations this same British playgoer is supposed to be fond of invocations to the Deity. Hence, Messrs Buchanan and Horner have not been able to keep their fingers off the great scene, the poison scene, at the close of what is their third and M. Daudet’s fourth act. In the original, Paul, after the failure of his attempt to poison his wife, sues for forgiveness, and is told in reply that though his wife may, and does, forgive, Nature never forgives. Upon that the curtain descends. The statement is true enough, and is perhaps one of M. Daudet’s tardy apologies to science—the science he has elsewhere so grievously offended by taking the name of Darwin in vain. Messrs Buchanan and Horner prefer to take the name of the Deity in vain. The Duchess is made to point heavenwards, to allude to Him, &c., and to add in notes of religious fervour, “To your knees! to your knees!” If we timidly object that a man of Paul Astier’s temperament is hardly likely to be forced to his knees by references to a Deity in whom he does not believe, Messrs Buchanan and Horner will doubtless answer that whatever Paul Astier’s theological leanings may be, those of the British playgoer are well known, and it is those only which they have had in view.

The British playgoer, unlike the French, is supposed to have little fancy, on the stage, for excessive developments of parental affection. Lovers may be as mad as you please, but parents must not be allowed to let their feelings get the better of them. For some such reason as this, we suppose, the adaptors have altered M. Daudet’s dénoûment. It is no longer old Vaillant, the betrayed Lydie’s heart-broken father, who shoots his daughter’s betrayer, but Caussade, the young lady’s distracted sweetheart. The change is not for the better. It makes the prominence given to that tedious personage old Vaillant in the earlier acts of the play quite meaningless. The whole of the final business, too, of the last act, has been done away with. We no longer have the sale by auction, in which the auctioneer’s words were made so ingeniously to fit in with the circumstances of Paul Astier’s death. In deference to what supposed prejudice of the British playgoer this detail has been sacrificed, we confess ourselves quite unable to surmise. But enough on the subject of the adaptors’ alterations.

The players, we began by saying, have done fairly well. Some of them unexpectedly well. We doubt, for instance, whether anyone familiar with Mr Alexander’s pleasant, sunny, buoyant stage personality could have foreseen how cleverly he has adapted it to the exigencies of a part which is its very antithesis. True, he does not succeed in realising for us, so completely as M. Marais did, the ruthless, brutal, hateful, yet polished ruffian of M. Daudet’s imagination. Nature will not let him do that. But he goes very near it, playing throughout with a subdued force, an incisiveness, a distinction, for which few playgoers can have been prepared. There are one or two mistakes of detail. He was too slow over the poisoning business; not sufficiently callous in his description of Lydie’s attempted suicide; and in the fourth act he was an unconscionable time a-dying. Paul Astier should spin round like a top, and fall as dead as a doornail. The author’s idea is to give an effect of a villain’s sudden extinction at what seems the very height of his triumph. This effect is weakened by a death too prolonged. The Duchess Padovani is played, of course, by Miss Genevieve Ward. We say of course, because she is the one actress on the English stage for whom the part might expressly have been written. Her impressive presence, her sonorous and distinct utterance, the air of intellectual power which is a very part of her being—these things find ample scope in the character. Now and then, perhaps, where the Duchess should be in the melting mood—and only a melting duchess could have succumbed to the influence of such a ruffian as Paul Astier—Miss Ward is a little hard. It is inevitable that a style which has the polish and the fine edge of a steel blade should have something of its hardness, too. But it is on the whole a fine performance, worthy of the actress, and far too good for the play. Miss Alma Stanley looks the handsome Jewess, Esther de Sélény, to the life, but she fails to impart much significance to the character. M. Daudet’s Esther is far from being an agreeable personage. She is designed as a natural mate for Paul Astier—the feminine type of the “Struggle for Lifeur.” Miss Alma Stanley, assisted by the author, tries to become sympathetic, introduces touches of comedy, all with indifferent success. Fault has been found with Mr Chevalier because his Chemineau is a broader caricature than M. Noblet’s. Mr Chevalier’s hat may possibly be a mistake, and he may also have gone to the wrong tailor; but if he has presented us with the Frenchman of the English comic papers, instead of with a realistic study of the latter day Boulevardier, he may plead that, like Messrs Buchanan and Horner, he knows his public, and provides them with the comic Frenchman which they are accustomed to expect. Miss Laura Graves makes a pretty and sympathetic Lydie, though she ought to know that in France Alsatian bows as an article of headgear are confined to nursemaids. Her big scene with Caussade, in the second act, went as well in English as it did in the original, a result the credit of which is mainly due to the acting of Mr Frederick Kerr. Mr Kerr, perhaps, unduly exaggerated the uncouth ways and awkward appearance of the young chemist, but the force and feeling of the character lost nothing in his hands. Miss Kate Phillips’s picture of the weeping Maréchale de Sélény will not bear comparison with that of the inimitable Desclauzas, but she looked very charming and, mirabile dictu, almost slim, in her widow’s weeds. Of the rest there is little to be said. Mr Nutcombe Gould does his best to mitigate the tediousness of old Vaillant. But Messrs Buchanan and Horner have made the task impossible for him. Mr Ben Webster does not grasp the character of Count Adriani, nor does he wear the correct uniform of a Papal Noble Guard. Mr Bucklaw as Védrine, an insignificant character of the adaptors’ own creation, and Mr George Capel as Heurtebise, the Duchess’s old family servant, are not more than sufficient.

___

The Sporting Times (27 September, 1890 - p.2)

AFTER a very long and successful run, that brilliant and mirth provoking comedy, Dr. Bill, has been supplanted at the Avenue Theatre by A Struggle for Life, an adaptation of Daudet’s La Lutte pour La Vie, by Robert Buchanan and Fred. Horner. The new piece is as gloomy as Dr. Bill was bright, and the production on the first night seemed to have anything but an exhilarating effect upon the audience. The brilliant acting of the leading characters was sufficient to rivet the attention of the spectators during the progress of the play, and at the close a demand was made for the authors.

PAUL ASTIER is not a wholesome character. He has married a foolish lady, whose fortune he has dissipated, and of whom he would be glad to rid himself, so that he can marry a wealthy and handsome young Jewess. He has betrayed a trusting girl, who dies of a broken heart; and in the end he goes to the extent of trying to poison his wife with aconite, his career being brought to a sudden end by a shot from the lover of the girl he has betrayed. As the injured wife, Madame Astier, Miss Genevieve Ward played with all her old force and skill. She has seldom given a more powerful piece of acting than in the scene in which she brings her cowardly husband to his knees when he has passed her the glass of poisoned water, which she raises to her lips under the pretence of drinking it. Mr. George Alexander is a worthy support to this talented lady, and his refined, forcible, and well-studied acting almost makes one forgive the villain for his villainy, and admire his brilliant coolness and impudence. Miss Alma Stanley acquits herself well in the difficult part of Esther de Sélény. Miss Kate Phillips makes the best of a rather tedious character of a widow, who is always sounding the praises of her deceased husband, and Miss Laura Graves plays in a subdued and tender way the role of Lydie, the betrayed victim of Paul Astier. Of the somewhat long list of characters Mr. Nutcombe Gould, as the broken-hearted father of Lydie, Mr. Albert Chevalier as Chemineau, the friend of Paul, are well worth mention. Mr,. Frederick Kerr has rather a trying task as the lover of Lydie, a quiet, stuttering, analytical chemist, who finally brings the villain to grief, and Mr. Ben Webster has little opportunity of distinguishing himself as Count Adriani.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

[Advert for The Struggle for Life from The Times (27 September, 1890).

Reynolds’s Newspaper (28 September, 1890)

AVENUE THEATRE.

“The Struggle for Life,” an adaptation of M. Daudet’s “La Lutte pour la Vie,” by Messrs. Robert Buchanan and Fred Horner, was produced at the Avenue Theatre on Thursday evening. The authors have taken pains to explain that their version of the distinguished Frenchman’s play is in no sense a “translation.” They have made great changes in the dialogue and plot, and the sequence of scenes and incidents has been altered. The fundamental idea, however, is retained. It is, in fact, a drama upon the quasi-Darwinian theory of the “survival of the strongest.” Paul Astier, an architect and member of the Chamber of Deputies, is an incarnation of worldliness. “Self” is the guiding star of his life. He indulges his passion for pleasure, yet he is consumed with ambition. The cross-working of these tendencies occasions his ruin. No aspiring Frenchman is supposed to be completely equipped for his task unless he has in hand some thrilling feminine intrigue. With women Astier is perfectly irresistible. They all believe him sincere, except his wife, the Duchess Padovani, whom, older than himself, he married for her possessions. He is now anxious to get rid of her by fair or by foul means, that he may marry a young, wealthy, and beautiful Jewess, Esther De Sélény, Meanwhile, in a spare moment, he has seduced Lydie Vaillant, the innocent and confiding daughter of the local postmaster. Paul’s wife will not consent to be divorced; so he thinks of poisoning her, but draws back at the last moment. His neglect and cruelties, however, eventually induce the Duchess to consent to a divorce. Astier is just on the verge of attaining all he desired—money and a wife after his own style—when he is shot dead by Antonin Caussade, an analytical chemist, whose sweetheart, Lydie, died of a broken heart through the treachery and desertion by the hero. As interpreted by Messrs, Buchanan and Horner, the play bears evidence of hasty and somewhat crude construction. Its parts are not harmoniously welded together. We are jerked from situation to situation. Considered as an artistic work, a certain grace and harmony are lacking. In the first act, which has for its locale the exterior of Astier’s home, the Château of Mousseaux, there is some tedious trifling with a party of sightseers. The crowded drawing-room scene in the third act is monotonous. The fourth act is oppressed with fragmentary incidents. Throughout the play the dialogue is generally dull, and too frequently commonplace. Much was done to relieve these faults of authorship by the powerful acting of Mr. George Alexander, as Paul Astier, and Miss Genevieve Ward as his wife, the Duchess Padovani. Nothing could be better in its way than Mr. Alexander’s representation of the cold, heartless, hypocritical cynic. The picture of smooth selfishness and tutored self-control was painted with such delicate and subtle touches that the personality of the other characters was minimized or forgotten in anticipating what future the Fates were weaving for the hero. The death scene was most impressive. Astier’s wild, despairing struggle with the inevitable; his agonizing cry as the goblet of life is dashed from his lips; his ineffectual defiance to the doom to which in a moment he succumbs, formed a series of intense and highly dramatic incidents. Miss Genevieve Ward sustained her difficult part with the greatest ability. She was the proud châtelaine, overwhelmed with remorseful self-reproaches for weakly allowing Astier’s fascinations to overcome her resolve to repudiate him. Her bearing was lofty and noble; there could have been no better exponent of the part. In the poison scene she commanded the enthusiasm of the audience. Of the other performers—with the exception of Miss Alma Stanley, who was the Jewess, Esther De Sélény, and Miss Kate Phillips, who went very amusingly through the farcical part of a weeping widow—it must be said that if they had intended to saturate their representations with a Gallic flavour they were not altogether successful. Lydie Vaillant, for instance, played by Miss Laura Graves, was rather a sentimental, puling English schoolgirl, than what we should fancy a French girl to be under the circumstances. Mr. Albert Chevalier had an admirable opportunity as Chemineau, the flippant friend of Paul Astier. Now he did not convey the idea of “friend”; but rather of hired retainer; the note of gentility was missing. His playfulness lacked unobtrusive spontaneity, and there was little of the French style about it. Had the character been English, Mr. Chevalier’s playing would not be open to the same censure. Mr. Frederick Kerr is an actor upon whom we look with pleasure and hope. His art is always marked by intelligence and finish. The interview with Lydie Vaillant, when he has discovered her intrigue with Astier, was in every way admirable. But why is Mr. Kerr’s make-up quite so depressing from the beginning? If Antonin Caussade always looked like that, it is no wonder Lydie turned her eyes elsewhere. Mr. Nutcombe Gould was hardly an ideal French father, although here and there were some effective suggestions of pathos. Mr. Ben Webster’s Count Adriana, attaché of the Italian Embassy, will be improved when the actor is less self- conscious. At the conclusion of the piece the unofficial critics seemed to be about equally divided as to its merits, although at no time had they any doubt of the excellence of the acting of Mr. Alexander, Miss Ward, and Mr. Kerr.

___

The Referee (28 September, 1890 - p.3)

The Avenue, hitherto devoted to more or less merry plays, comic operas, burlesques, and farcical comedies, had a rather novel experience on Thursday evening. Not to put too fine a point upon it, the long-talked-of adaptation of A. Daudet’s purpose-play, “La Lutte pour la Vie,” was then forthcoming. Refereaders will remember that early last June I described the piece, then being played with its original cast and language at Her Majesty’s. They will also recollect that, barring one or two strong scenes, I found little in the play worthy of honourable mention. I had hoped, however, seeing that an English version had been threatened, and seeing that it had taken two full-grown and largely-experienced adapters to adapt it, that “La Lutte pour la Vie” would be found improved, or anyhow strengthened, for the British market. But no; although Daudet’s name is now kindly acknowledged (but in tiny type compared with the big caps given to the adapters, R. Buchanan and F. Horner); and though the bill of the play bears what is somewhat impudently called an “Authors’ Note,” wherein the adapters set forth that they have made considerable changes; and though the play is beautifully staged—yea, even though the dressmakers’ names occupy a large part of the programme, “The Struggle for Life” (as the “authors” call it) is not good—at least, not much. The first two acts are, in some sense, an improvement on the original, and are tolerable and to be endured; but in the other two (with the exception of a little fillip in the poison scene) the piece seems to go down, down, down. When the curtain fell at 11.35 on Thursday the interest had dwindled to vanishing point even more than in the original play, and that’s saying a good deal.

“The Struggle for Life” treats, it will be remembered, of the bold behaviour of a certain so-called “scientist,” who swaggers, swears, and seduces wholesale; and eventually, in order that he, the self-styled Fittest, may survive, endeavours to poison his elderly but loving wife, who bars his way to an heiress. Anon (in the original), he is shot through the heart by the father of one of his victims. The Avenue “authors” have caused the victim’s sweetheart to do the shooting, and so have robbed the only really sympathetic male character of the sympathy that he had been winning in the earlier part of the piece. Moreover, the “authors,” instead of writing in any fresh comedy relief, have relied mainly upon the foolish-feeble japes of the original. What then, to sum up, do we find in these four acts? About two strong “duologues”—little else. Nor can I honestly predict that “The Struggle for Life” will be found of much use in the Struggle for Oof. George Alexander plays the so-called scientist, Paul Astier, in an earnest, firm, and carefully studied manner, but Marais, the original, had more “devil” in him. Geneviève Ward, always intense and dramatic, gives a dignified and pathetic representation of “P’lastier’s” elderly duchess, but she lacks the thrilling power of Pasca. The best and most human bit of acting in the piece is Mr. F. Kerr’s Caussade, the poor, stammering, true-hearted analytical chemist—an awful part to play. The remainder of the cast had not much opportunity.

___

Glasgow Herald (29 September, 1890)

MUSIC AND THE DRAMA.

___

(FROM OUR OWN CORRESPONDENT.)

London, Sunday Night.

Messrs Buchanan and Horner’s “Struggle for Life,” being the English version of Daudet’s satire on the Darwinian theory, entitled “La Lutte pour la Vie,” has duly been produced at the Avenue. The London critics seem divided in opinion concerning the merits of the work; and the wisdom of a change in the denouement—Paul Astier now being shot, not by the vengeful father of the poor girl he has ruined, but by the young chemist who is the girl’s sweetheart—has especially been called in question. The chief defects of the “Struggle for Life” are, however, in the original French play rather than in the English adaptation. The central personage in the piece, although affording Mr Alexander a strong character part, which the young actor plays admirably, is a being for whom audiences can possibly express no other feeling than that of detestation. Himself quite penniless he fascinates and marries a rich woman of middle age, who, believing in him, confides to him almost all her fortune. Paul Astier speedily gives proof that her money alone is an object of interest to him. He agrees with the handsome and wealthy Jewess Esther de Sélény to marry her after he has divorced his wife; and under promise of marriage he has also seduced the young woman Lydie. His wife refuses to divorce him, and for a time they are apparently reconciled. Paul, however, when one day visiting Lydie, discovers that the unhappy girl has taken poison. He calls in a doctor, who administers remedies, and taking the rest of the poison home, he resolves with it to kill his wife. His courage, however, fails him, and his wife (the French plot here again being altered) commands him to fall on his knees for Divine forgiveness. In the last act the scene of the auction has been suppressed, and, as we have already indicated, Paul, by a pistol shot, receives fitting punishment for his crimes. The success which the drama achieved was due chiefly to the magnificent acting of the Avenue company, and especially of Mr Alexander as the Paul Astier, and of Miss Genevieve Ward as his wife, the poison scene being particularly effective.

___

The Manchester Courier and Lancashire General Advertiser (29, September 1890 - p.5)

There were two new plays produced in London during the past week. The most important was the English version of Daudet’s La Lutte Pour la Vie at the Avenue, and it must be confessed that Mr. Robert Buchanan’s adaptation of it is unfortunately another failure for this popular but rather too prolific dramatist. It is true, however, that without entire reconstruction Mr. Buchanan could not possibly have made this play sympathetic or suited to English audiences. The original French version was bad, the motif being unreal in the extreme, and translated into English its faults remain just as glaring, whilst the characters are mostly exaggerated, not to say impossible, types of human nature. To add to the misfortune of the production half the actors had completely misconceived their parts, and it was certainly only due to Miss Genevieve Ward and Mr. George Alexander that the piece was received with any degree of applause. By their powerful acting and artistic treatment of their unreal parts they “lifted” scene after scene, and when they were on the stage the audience was content to tolerate the uninteresting play. A Struggle for Life is not likely to be seen for long on the English stage.

___

The Sheffield Daily Telegraph (2 October, 1890 - p.5)

“THE STRUGGLE FOR LIFE.”

In a note by the authors, Mr. Robert Buchanan and Mr. Horner, on the programme of “The Struggle for Life,” the new play at the Avenue Theatre, we are assured that the present version of Daudet’s “La Lutte pour la Vie” is in every sense of the word an adaptation rather than a translation. In this the authors show their wisdom and appreciation of English taste. The more of adaptation and the less of translation we have in the case of these French plays the better. “The Struggle for Life” is an interesting piece, with plenty of brisk action and stirring scenes. The thread of the plot is briefly as follows. Paul Astier (Mr. George Alexander), a brilliant but utterly unscrupulous adventurer, whose one object is to climb to the top of the ladder of life, and who is an expert above everything in making love, manages to gain the affection of the Duchess Padovani (Miss Genevieve Ward), who is weak enough, knowing his treachery, to marry him, and thus lift him “out of the gutter.” She soon discovers how monstrous her folly has been, and after he has squandered her fortune and illtreated her she leaves him, determined, however, not to grant him the divorce he himself longs for in order to marry another woman. Her resolution cannot be overcome until she discovers that Paul Astier has meditated poison as a last resource. She then grants him his divorce, and leaves the country. His object seems all but attained; and he will be able to marry the rich Jewess, Esther de Sélény, who, too, has been waiting for this divorce. But fate with swift and sure tread waits upon her ambitious lover. He has only a short time since wronged a poor, trustful girl, Lydie, daughter of Voillant, a postmaster. Her death and that of her old father are the results of this villainy, and Lydie’s lover, Antonin Caussade (Mr. Kerr), avenges them by killing Paul Astier in a fearfully deliberate manner.

THE CAST.

I do not remember having seen Miss Genevieve Ward since she acted many years since with the late Mr. John Clayton in “Forget-me-Not.” That was at the Prince of Wales’ Theatre, now no more. She is probably one of the most powerful actresses—if not the most powerful, with the exception of the “Divine Sarah”—which have been seen by the London public for a good many years. In the part of the Duchess Padovani Miss Ward has ample opportunity for showing her strength, and she certainly does not fail to do so, although she has to act the part of a woman whose character is a singular compound of weakness and of strength. Mr. Alexander has a big part—perhaps the biggest he has yet taken—in Paul Astier: as the fickle lover, who wins any and every woman by his burning words about “the soul, the stars, the heavens” he is most admirable. He is the complete humbug, though not perhaps as complete a villain as one would conceive Paul; Astier to be. Miss Graves makes a charming Lydie, and Mr. Kerr is the very man for the part of Caussade, shy and tongue-tied in the presence of strangers, and especially in that of his Lydie; but with a soul that flashes out in “the presence of the great occasion”—a most interesting and finely drawn character. Miss Alma Stanley is well adapted for the part she plays. Mr. Gould puts plenty of colouring into the character of Vaillaux, whilst Miss Phillips and Mr. A. Chevalier in their respective parts very properly lighten what might be otherwise too gloomy a production.

___

The Stage (3 October, 1890 - p.12)

LONDON THEATRES.

THE AVENUE.

On Thursday evening, September 25, 1890, was produced here a four-act drama, adapted from Alphonse Daudet’s La Lutte pour la Vie, by Robert Buchanan and Fred Horner, entitled:—

The Struggle for Life.

Paul Astier ... Mr. George Alexander

Chemineau, his friend ... Mr. Albert Chevalier

Count Adriani ... Mr. Ben Webster

Vaillant ... Mr. Nutcombe Gould

Antonin Caussade ... Mr. Frederick Kerr

Védrine ... Mr. Bucklaw

Heurtebrise ... Mr. George Capel

Duc de Brentigny ... Mr. Batson

Monsieur Noblet ... Mr. Alfred Holles

Stenne ... Mr. E. H. Kelly

Paskowitch ... Mr. A. Royston

Esther de Sélény ... Miss Alma Stanley

La Maréchale de Sélény Miss Kate Phillips

Lydie ... Miss Laura Graves

Countess Fodore ... Miss Lilian Hingston

Madame de Quincampoix Miss Granville

La Marquise de Rocanère Miss Stuart

Marie ... Miss Melitta

Madame Paul Astier,

Duchess Padovani ... Miss Genevieve Ward

There is not much in Messrs. Buchanan and Horner’s work that can be justly praised, and what success it secured on the night of production was entirely due to the actors who appeared in it. The original French version is not at all a satisfactory play, and its weakness and transparency have become more glaring in the process of adaptation. The Struggle for Life is a pretentious piece, wofully sketchy and quite inadequate in its treatment of the cruel but incontestable theory as put forward by its principal character, Paul Astier. The adaptors claim in an authors’ note published on the programme that, as regards the original French, “great changes have been made in both dialogue and plot.” Unfortunately, the changes are such as to make the play more feeble than it was, while the dialogue, when it wanders away from bare translation, is of a very ordinary nature. An unpardonable blot in the present version is the finale of the drama. In the original, Paul Astier is shot at and murdered by the father of Lydie, the girl he has ruined. Now we have the murder committed by the lover of the unfortunate girl, one Antonin Caussade, a stuttering and nervously undecided youth, the consequence being that what should be sharp and decisive action, is delayed by the methodical and laboured speech of the avenger. Surely the adaptors cannot call this an improvement upon Daudet’s plan. It is, however, hardly worth while discussing the merits of a play that will not bear analysis. The story, as told by the adaptors, is as follows:—Paul Astier, a pleasure-seeker at the expense of others, a libertine, a false-hearted, smooth-tongued, polished scoundrel, has, for the purpose of securing her property, married the Duchess Padovani, a widow, old enough to be his mother. He is anxious to secure a divorce from her that he may marry a beautiful Jewess, who loves him passionately, Esther de Sélény. While prosecuting his love affairs with Esther, Astier has also entangled himself with Lydie, the daughter of a postmaster, and humble friend of Esther’s. The girl has given her entire heart to Paul, and he, taking advantage of her devotion, has ruined her, while bestowing benefits upon her unsuspecting father. Lydie has a devoted lover in Antonin Caussade, a young chemist. Antonin suffered a severe shock to his nervous system when a boy, with the result that since that time he has been the victim of partial paralysis of the vocal organ, and when much excited or distressed cannot speak as fluently or rapidly as he may wish. What more natural than that this afflicted youth should, when he learns of Lydie’s disgrace, make up his mind to kill her seducer? In the meantime, Madame Astier, having repeatedly told her husband that she will die his wife, that he shall have no divorce, and that God has joined them and God only shall separate them, is so horrified at finding out that twice her husband has attempted to poison her, that she yields, and grants him the liberty he desires. Both these attempts to poison are made much of in the play, and are evidently considered as quite tragic moments by the adaptors. As a matter of fact, they are not led up to, and appear overstrained and out of place. In the first case, Astier enters his bed-room with a bottle of aconite he has taken from Lydie, whom he has found on the point of destroying herself. He proceeds to dress himself for a reception to take place that evening, and in the act of adorning his person before a looking-glass, again sees the bottle, and taking it up indulges in a soliloquy, in which he contemplates how that a few drops would soon rid him of his wife. The wife enters from the centre, and overhears him, and, of course, Paul sees her reflection in the glass, and moreover, discovers that she is looking at him, and that she fully knows what he is doing. The second attempt at poison takes place in Madame Astier’s saloon. A strangely-assorted set of guests has departed, and husband and wife are alone. Madame is seemingly faint, and asks her husband to being her a glass of iced-water. The guilty-souled one hesitates. He is still thinking of the bottle he has with him, and of the few drops that would bring about freedom from his grey-haired wife. Madame notices his hesitation, and again requests him to obtain what she requires. Paul leaves the room and returns with the water, into which he pours the poison. The wife takes the glass, and makes as if to drink its contents, when Paul, with a cry of horror, stops her. Of course, it is all a trick. Madame is not ill, she merely wishes to try her husband. She, Lady Macbeth like, tells him he is infirm and weak of purpose, but that she is convinced he will not let his conscience trouble him should he make a third attempt. Paul cowers before his strong-minded spouse, and she, wishing to spare him shame, throws the glass out through an open window. It is this last incident that convinces Madame of the wisdom of permitting her husband to have his own way, and accordingly, despite her previous religious outburst with regard to the sanctity of the marriage vow, she and Paul are divorced. Next we find Paul and the beautiful Esther engaged. A rumour reaches Esther, and then the truth about the seduction of Lydie. She accuses her lover, and he, in a flippant manner, excuses himself. The girl came in his way; what could he do? He was alone, and had no loving Esther at his side. It was only a trifling incident, unworthy of serious thought. Paul half convinces Esther, and with his arm round her waist, is pouring soft velvety words of love in her ear, when the avenger, Antonin, appears upon the scene, and in slow and halting language addresses the seducer, to the effect that he (Paul) has long gloried in his own theory that the strong shall conquer in this world, and derive their pleasures from the weak, whom they shall trample under foot, but that sometimes the weak conquer the strong. After saying which, Antonin draws a pistol from his pocket and shoots Paul Astier. The latter gives a long and bitter cry; makes an effort to rise from his fallen position, and then, nestling his head in Esther’s arms, dies.

After all is said and done, what is the moral of the play? A false sympathy is created for this modern Don Juan Astier. What little sympathy may be at first felt for Madame Astier, the dethroned wife is certainly discounted by the thought that she should not at her age have married so young a scapegrace. As regards the minor characters, the only human ones concerning the plot are Lydie, her father, Vaillant, and the stutterer, Antonin. And what is made of them? Nothing; they are mere sketches waiting the filling-in process. Antonin in the French was possible, quite different from Buchanan and Horner’s Antonin—who is but an irritating excrescence. Thanks to the actors, the play was saved from censure on Thursday. Mr. George Alexander has done few things better than Paul Astier. At times he showed a want of Iago-like subtlety in his performance, was perhaps too much the soft and seductive lover, full of sighs and poetical illusions. There can, however, be no doubt as to the cleverness of his portrayal. It was graceful and attractive throughout, and the adaptors may be said to have their only excuse for the play in the truly admirable performance of Mr. Alexander. Next to Mr. Alexander in merit is undoubtedly the Madame Astier of Miss Genevieve Ward—a well thought-out impersonation, lacking, it is true, in tenderness and womanly emotion, but grand in its strength and determination, dignity, and repose. Tragic in its intensity, it throughout commands respect and admiration. Mr. Frederick Kerr, in the most difficult part of the play, Antonin, was exceptionally good. It is not his fault that the character became a bore and wearied the audience. It was to his credit that it escaped ridicule. Miss Laura Graves, a young lady of much promise, played tenderly and sympathetically as the injured Lydie, and in one scene gave evidence of strong emotional power. Mr. Ben Webster did his best with a ridiculous part. Mr. Nutcombe Gould’s performance suffered at times from a want of consistency, but was otherwise good. Mr. Albert Chevalier’s impersonation of Astier’s friend, Chemineau, argued inexperience. He appeared to quite misunderstand the part, and he dressed it in an absurd manner. Mr. Chevalier must know that caricature is not characterization, and that the picture he presents is permissible in comic opera or burlesque only. It has no place in modern drama. As a young artist, Mr. Bucklaw looked well, and spoke his lines with polish and refinement. Mr. George Capel was adequate as an old servant, Mr. Alfred Holles was equal to the rôle of Noblet, and Mr. Batson gave a finished little sketch of the Duc de Brentigny. In the badly-drawn character of Esther—badly drawn because it is impossible to learn if the adaptors intend her to be a scheming adventuress or merely a frivolous woman with a true heart, Miss Alma Stanley looked superb, albeit her acting was a trifle deficient in grace and repose. Miss Kate Phillips was amusing in the absurd part of La Maréchale de Sélény, a weeping widow, who is constantly recalling the memory of her late husband, and generally proving herself a bore. Miss Lilian Hingston was bright and attractive as the Countess Fodore, and smaller parts were carefully filled.

The Struggle for Life, handsomely staged and dressed, by the bye, was listened to with attention from a crowded, good-natured audience, that called for the adaptors at the finish.

___

The Penny Illustrated Paper (4 October, 1890)

The New Play at the Avenue.