ROBERT WILLIAMS BUCHANAN (1841 - 1901)

|

ROBERT WILLIAMS BUCHANAN (1841 - 1901) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

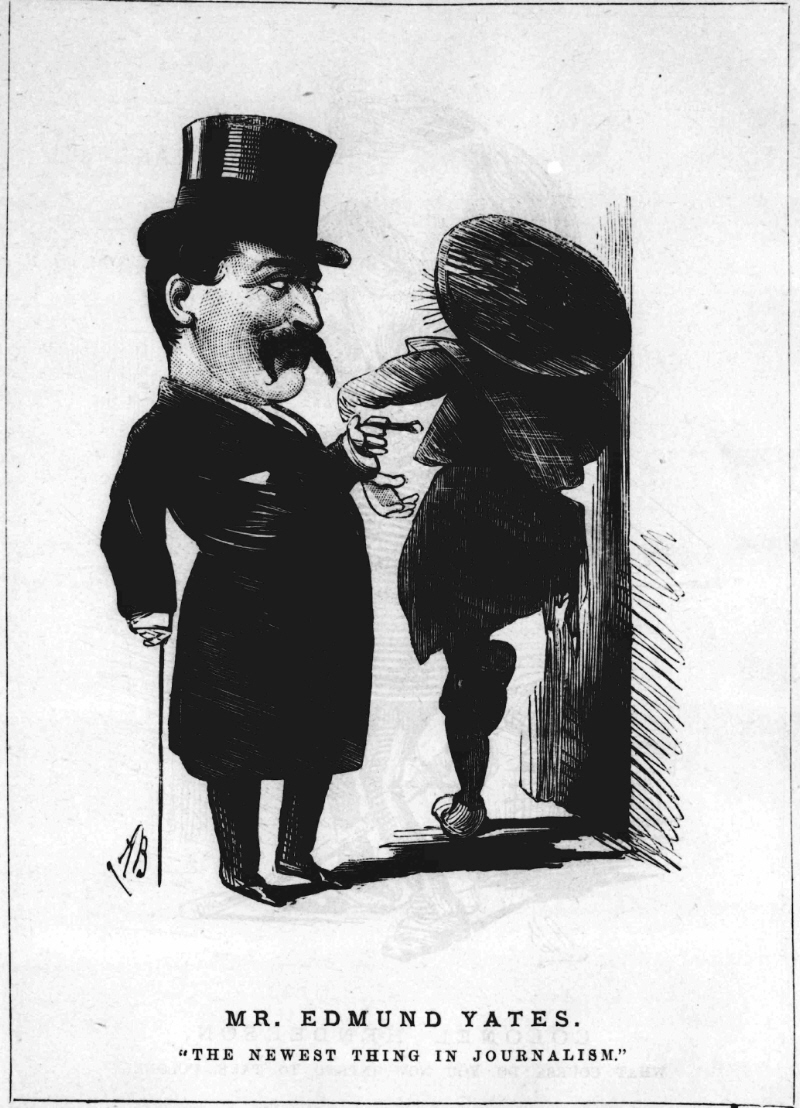

Essays - ‘The Newest Thing In Journalism’ - continued

The Edinburgh Evening News (26 September, 1877 - p.2) ONE of the very prettiest literary quarrels which this century has produced is at present raging in London. Its interest proceeds not from the magnitude of the combatants, but from the virulence of their attacks. This, indeed, makes it all the more amusing. It is painful to see Titans like Bulwer and Tennyson “heaving rocks at each other.” The present struggle, however, between Mr Robert Buchanan and Mr Edmund Yates, if it can be called Homeric in any sense, is rather a “Battle of the Frogs and Mice” than an “Iliad.” In the current number of the Contemporary Review an article appears under the title of “The Newest Thing in Journalism,” in which sundry weekly papers, and especially Vanity Fair, Truth, Mayfair, and The World, are held up to ridicule. Mr Edmund Yates, the editor of the last mentioned journal, comes in for an extra allowance of the critic’s contempt. He is accused, among other things, of snobbishness, vulgarity, and a tendency to small scandal-mongering, the accusations being accompanied by voluminous quotations. A habit of making capital of the prince of Wales, by detailing the smallest minutiæ not only of what he does, but of what he does not do, is one of the leading counts of the indictment. The attack as a whole, whether justified or not, is so pointed and trenchant that Mr Yates naturally feels somewhat sore after it, and in this week’s World he publishes a reply in the form of an article with the elegant heading of “A Scrofulous Scotch Poet,” to which he signs his name. It had been reported, he says, that the writer of the Contemporary paper was Mr Robert Buchanan. He accordingly requested Mr Buchanan to contradict the report, and on Mr Buchanan’s failing to do so he considers himself justified in assuming its correctness. He makes no attempt to defend himself from his opponent’s charges, but accuses him of ingratitude and treachery. In 1861, he says, he was engaged in the part editorship of Temple Bar magazine. “To my private house one evening,” he continues, “bearing a letter of introduction from a common acquaintance, came Mr R. W. Buchanan, then a mere youth of two or three-and-twenty, very shabby, very dirty, very ‘creepy’ altogether. Mr Buchanan is in the frequent habit of quoting Mr Browning’s phrase about a ‘scrofulous French novel;’ but I am of opinion, having tried both, that a scrofulous Scotch poet is a far more unpleasant object in a room.” Mr Buchanan told him of his poverty, “which was positively appalling,” and of the assistance he had received from a well-known nobleman. “He talked glibly,” says Mr Yates, “he showed me scraps of his poems. As I listened to him, I tried to think of Burns and Chatterton; but as I looked at him, I could not help also thinking of the practical benevolence of the Duke of Argyll, and of the vaunted virtues of Keating’s insect powder.” Mr Yates procured him work, lent him money, and claims actually to have saved his life. “And now,” he says,” I, who stepped out of my way to do this man a kindness, and out of my own small means lent him money to buy bread for his stomach and sulphur for his back, am ‘a retailer of gossip, with whom no society of respectable men, not to say gentlemen, would associate for ten minutes;’ while Mr. Robert William Buchanan, who stings the hand that succoured him, and anonymously stabs those who saved his tainted life, is a Contemporary Reviewer, the soi-disant guide, philosopher, and friend of ‘all cleanly people who respect honest literature and live earnest lives.’” Here be the amenities of literary life shown in an admirable light! For pure Billingsgate no one can equal your polished man of letters when he chooses to try his hand at it. The public verdict in this case will probably be the same as it was in a former celebrated quarrel in which Mr Buchanan was mixed up. “Arcades ambo,” the reader will say, and will thank his stars that he is neither a Scotch poet, nor a sensational journalist. ___

Shields Daily Gazette and Shipping Telegraph (27 September, 1877 - p.2-3) It was widely stated this morning that Mr Strahan was about to commence an action against Mr Edmund Yates for libel. In those lowest depths of journalistic Billingsgate, which Mr Yates wallowed in yesterday, occurs a passage which attributed to Mr Strahan the practice of not paying for his contributions. In justice to Mr Strahan, I should say that his brother publishers charge him with paying too much and too readily for his copy, but Mr Yates thought it right to hint otherwise, and another great literary trial was expected by the lovers of scandal. I have, however, the best authority for stating that Mr Strahan intends to take no notice of an attack upon his honesty which has by its violence defeated its own object. He prefers to let so much virulence work its own destruction. Mr Robert Buchanan, however, is considering the matter, and it is not impossible that he will appear in court to claim damages for a libel which represented him as scrofulous and covered with vermin. Heaven help us! What will be the next new sweet thing in journalism? ___

The Exeter and Plymouth Gazette (28 September, 1877 - p.8) LONDON LETTER. . . . I was one of those who always doubted the statement that Mr. Robert Buchanan was the author of the now famous article, “The Newest Things in Journalism,” which caused such a run on the last issue of the Contemporary Review; but I can no longer be in doubt now that I have read this week’s World. Under the heading of “A Scrofulous Scotch Poet,” and over the signature “Edmund Yates,” appears the latest development of this “newest thing.” Mr. Yates assumes Mr. Buchanan to be the writer, because the latter has left unanswered the former’s challenge to deny it, and he proceeds to pour upon the head of the wild Scotchman a tirade of personal abuse, which assuredly has never been equalled, certainly never excelled, in any English journal of late years. Mr Yates states that he became acquainted with Mr Buchanan in the winter of 1861, at the time he was engaged in assisting his old friend, Mr. Geo. Augustus Sala, in bringing out “Temple Bar.” Mr. Buchanan came with a letter of introduction from a common friend. This is how Mr. Yates describes him:—“A mere youth of two or three-and-twenty, very shabby, very dirty, very ‘creepy’ altogether.” As if this was not sufficiently venomous, he continues to speak of him as “an unpleasant object in a room,” and he adds:—“He talked glibly; he showed me scraps of his poems. As I listened to him I tried to think of Burns and Chatterton; but as I looked at him I could not help thinking of the practical benevolence of the Duke of Argyll, and of the vaunted virtues of Keating’s insect powder.” There is a great deal more of this kind of thing in the article, but I will ask leave to quote further the concluding sentences of this diatribe. They are:—“I have had no dispute with Mr. Buchanan; no word of anger has passed between us. When last I saw him I was his friend; when last he addressed me I was his benefactor; but now, without word or deed on my part, all is changed. I, who stepped out of my way to do this man a kindness, and out of my own small means lent him money to buy bread for his stomach and sulphur for his back, am ‘a retailer of gossip, with whom no society of respectable men, not to say gentlemen, would associate for ten minutes’; while Mr. Robert William Buchanan, who stings the hand that succoured him, and anonymously stabs those who saved his tainted life, is a Contemporary Reviewer, the soi disant guide, philosopher, and friend of ‘all cleanly people who respect honest literature and live earnest lives.’” No words in condemnation of such a specimen of loss of temper need be added. The savage ferocity of the article itself is its own condemnation. Mr. Yates is anxious to be regarded as an aspirant for the office of editor of the Times. He has surely lost all chance after this. People may laugh over these violent sentences, and may admire the smart language in which they are dressed, as many are doing to-day, but the conclusion all have come to is, that if our journals “of society” are to descend to such hideous personalities as these we shall be best without them. Mr. Yates had far better have answered the Reviewer’s criticisms than have thrown mud at Mr. Buchanan, and specifically alluded to him as one “who has failed as a poet, a novelist, and a play-wright.” ___

The Newcastle Courant (28 September, 1877) A SCROFULOUS SCOTCH POET.—This is the title under which Mr Edmund Yates slates Mr Buchanan in the World. Here are Mr Yates’s closing sentences:—“I have had no dispute with Mr. Buchanan; no word of anger has passed between us. When last I saw him I was his friend; when last he addressed me I was his benefactor. But now, without word or deed on my part, all is changed. I, who stepped out of my way to do this man a kindness, and out of my own small means lent him money to buy bread for his stomach and sulphur for his back, am ‘a retailer of gossip, with whom no society of respectable men, not to say gentlemen, would associate for ten minutes;’ while Mr. Robert William Buchanan, who stings the hand that succoured him, and anonymously stabs those who saved his tainted life, is a Contemporary Reviewer, the soi-disant guide, philosopher, and friend of ‘all cleanly people who respect honest literature and live earnest lives.’” For roughness we never knew any one who could beat that; not even the man whom we call in to do our swearing when contributors send us bad copy. ___

Printers’ Circular (October, 1877 - Vol. XII, No. 8, p.1) PERSONALITIES IN ENGLISH JOURNALISM. There was a time—and it is within the memory of living men not yet past twoscore—when all Englishmen held up their hands in holy horror at the coarse personalities of American journalism. There was good cause for this, though our elder brethren across the sea refused to take a charitable view of the subject, stubbornly declining to take into account the inevitable lack of culture, refinement, and self-restraint incident to our rapid growth and rough surroundings. American journalism, when in its homespun swaddling clothes, was in England measured by the highest æsthetic standards. With the progress of time offensive personalities disappeared from the columns of the older American journals, more particularly those published in the centres of civilization—the large Eastern cities. ___

The Edinburgh Evening News (2 October, 1877 - p.3) “THE NEWEST THING IN JOURNALISM.” I am able to state, says the London correspondent of the Glasgow News, that Mr Robert Buchanan is not responsible for the series of articles in the Contemporary Review entitled “Signs of the Times,” of which “The Newest Thing in Journalism” was one. These articles are written by a variety of people, and with regard to the particular article which has so stung Mr Edmund Yates, editor of the World, I hear two names mentioned of persons who are said to have had a hand in it. One of these is a certain Northern M.P., prolific in the production of political pamphlets; the other is Mrs Lynn Linton, the well-known novelist and Saturday Reviewer. Mr Yates’s gross and scandalous attack upon your townsman Mr Buchanan is everywhere condemned, and it cannot but do its writer much damage in literary circles. ___

The Manchester Courier and Lancashire General Advertiser (2 October, 1877 - p.5) FROM OUR LONDON I have authority to state that Mr. Robert Buchanan is not responsible for the series of articles appearing in the Contemporary Review, entitled “Signs of the Times.” With regard to the particular article which led to Mr Edmund Yates’ personal attack upon Mr. Buchanan in the World, I hear the names of two persons mentioned as having a hand in it, viz., Mr. Edward Jenkins, the member for Dundee, and Mrs. Lynn Linton, but I do not vouch for this absolutely. I may state that the spirit in which Mr. Yates’ scandalous article is viewed in literary circles in London is entirely in accordance with your excellent leading article of the 27th ult. Even if the statements of Mr. Yates were all true it is universally felt that he was the last man to make it known. But the whole thing is a gross misrepresentation, and an incident unparalleled in literature. ___

Sheffield and Rotherham Independent (6 October, 1877 - p.6) METROPOLITAN NOTES. . . . I suppose the silence of Mr. Robert Buchanan for so many days after the appearance of that awful attack upon him by Mr. Edmund Yates, in the World, may be taken as proof that the Scotch poet was really the writer of the article, “A New Thing in Journalism,” in the Contemporary Review; but Mr. Yates was a bold man to put that letter in type on the strength of the fact that no answer to a letter addressed to Mr. Buchanan had reached him in twelve days. For this Scotch poet is a most difficult man to find through the post. He is usually staying in a wild and remote country in the far west of Ireland, but he is habitually sparing of the revelation of his address, and letters forwarded to his London address, I have reason to know, do not overtake him as a rule. As one who has some knowledge of each of these belligerents, let me say that Mr. Yates’ account of Mr. Buchanan does not convey a very correct impression of the man personally. Unquestionably the poet is personally somewhat unpopular among the men of his craft. He has not taken the pains to please or conciliate his confreres, and a good many of those who have been at one time or other his friends are found afterwards to be not on good terms with him. But apart from disputes and quarrels and personal differences, Buchanan is a good-looking, gentlemanly man, of pleasant manner and address, who would be a very welcome addition to any company so long as the company consisted of those between whom and himself no quarrel or coldness had previously come. And if Robert Buchanan is not a successful poet, so much the worse for the public; for there are certainly not more than half a dozen living men who have done finer work than he in that field of literary labour. It is a not less noteworthy fact that Edmund Yates, who in his rage cuts and slashes in this terrible fashion, is one of the most genial, engaging, and indeed fascinating of men. He has the happy gift of becoming popular wherever he goes, and it is difficult to imagine how anyone can say a word against him who has enjoyed the pleasure of his company. His best friends, however—unless they are among the too numerous men of letters and journalists who have been offended in one way or another by the Scotch poet—condemn him for the intemperateness of his castigation of the author of the article in the Contemporary. That article in the Contemporary, by the way, was, with all its faults, a clever piece of work. ___

The New York Times (9 October, 1877) [Note: The scan of the following article was a little difficult to read at the start, so there is one word missing. The original is available on the site of The New York Times.] JOURNALISM IN ENGLAND. THE NEW ERA AT ITS WORST. FEW PERSONAL ITEMS—THE WAR BETWEEN From our Own Correspondent. At last the old country has eclipsed the new. America may beat England at Creedmoor; the States may run Great Britain hard __ Philadelphia, but Jonathan’s supremacy in personal journalism is at an end. Rowdyism in the press is no longer a trans-Atlantic characteristic. John Bull has got even with Chicago and Cincinnati. There is a row in London just now worthy of the backwoods of journalism. The most extraordinary feature of the story is that the blackguardism is initiated in a high-class publication, and that the offending pen is wielded by a poet. The Contemporary Review is the medium of the sin, the sinner is Buchanan. The author is not unknown in the States. He has written some admirable verse, and he is the writer of a powerful novel called The Shadow of the Sword recently republished in New-York and Canada. He lately sued the Examiner for libel and recovered damages. The case arose out of an attack which Buchanan made on “the fleshly school of poetry.” The Examiner defended Swinburne, the apostle of that so-called school, and proved in court that Buchanan himself had written some certain uncleanly stanzas. Buchanan is an Ishmaelite among littérateurs and journalists. His arrogance borders on madness. He once wrote an anonymous article in praise of himself. He is the author of two dramas which failed—“A Madcap Prince” and “Corinne,” produced two years ago at the Lyceum. In connection with the first piece he was the cause of a clever jeu d’esprit. He was called before the curtain, and he appeared in a very outre costume. A satirical journal, edited by an American in London, called attention to the author’s strange attire. Mr. Buchanan replied, and charged the critic with having on this occasion had “a glass too much.” The editor, in reply, said: “It is true that out critic had a glass too much for Mr. Buchanan—it was an opera-glass.” ___

The Boston Daily Globe (9 October, 1877 - p.4) A QUARREL IN GRUB STREET. Isaac Disraeli has fished in muddy waters, and in relating the dissensions of authors he has stirred up more slime than one would have credited the most stagnant pool of literature with possessing; but there were foul spots from which the old angler drew back; there were miasmas where he refused to believe that any respectable trout would deign to hide itself. Such a one is the quarrel of Edmund Yates, editor of the London World, and Robert Buchanan, poet and essayist. Sing their wrath, O Muse, from its very inception. ___

Shields Daily Gazette and Shipping Telegraph (11 October, 1877 - p.2) Mr Robert Buchanan had better take care that he lives a life free from actions capable of being interpreted. His dear friends, the editors of the gossip papers, are seeking everywhere for some charge to bring against him, and won’t they revel if they get it? At present, they have found nothing save that he was once on a time poor and sick, and that, though now a veteran, he takes £100 a-year from the Queen’s bounty. ___

The Hampshire Advertiser County Newspaper (13 October,1877 - p.6) You know what the World (I won’t say “and his wife”) says of Mr. Robert Buchanan—as contemporary (reviewer) reviewed! Well, I hear—and I tell the tale as it was told to me—that the “Newest Thing in Journalism” after all is not his! The authorship, two days after the Contemporary for September was out, I heard confidently attributed to Mr. Arthur A’Beckett, whilome of the Tomahawk. But now I hear it assigned still more confidently to the authoress of “The Girl of the Period” essay in the Saturday Review, Mrs. Lynn Linton. ___

Trewman’s Exeter Flying Post (17 October, 1877 - p.8) That literary scandal of Edmund Yates and Robert Buchanan is still the talk of the Garrick and the Athenæum, and there is, I believe, but one opinion about Edmund Yates’ letter, that if Buchanan was the author of the skit in the Contemporary Review this was not the answer to make to it, and it is now said that article was not his at all, but Mrs. Lynn Linton’s, and I think this is the likeliest story. Robert Buchanan, it is said, intends to issue a writ against the World, and I hope he will, for this style of criticism is disgraceful to English journalism. You recollect how for a personal allusion to George Augustus Sala’s nose the Author of “The Gentle Life” was mulct in a fine of £500 and costs by a jury in Westminster Hall, and if Mr. Buchanan could only get a Scottish jury into the box to try his case he would get £5,000, for the Scotchmen are ferocious about one of their countrymen requiring sulphur for his back and vermin powder for his clothes. I do not know whether the story is true or not—probably it is, for Buchanan is even now a rough rugg-headed Kern; but this is not the sort of stuff to publish against a man in a public newspaper, and Edmund Yates is the last man in the world to take to throwing stones against his neighbours’ glass-houses. ___

Shields Daily Gazette and Shipping Telegraph (23 October, 1877 - p.2) A new page is about to be added to the history of “The Quarrels of Authors.” Mr Robert Buchanan, it will be remembered, wrote in the Contemporary Review for September a severe article on the London gossip journals, in which the World was especially condemned. I believe that no names were mentioned, but there were certain allusions in it to the career of Mr Edmund Yates which he too well uinderstood, and he replied with an attack upon Mr Buchanan, which, for indecent and outrageous personality, has not been equalled in our day. Mr Buchanan now feels himself free to deal with Mr Yates in person, and has, as I learn from Mayfair, prepared for him a castigation which, I have no doubt, is as severe as it is deserved. ___

The Dundee Courier and Argus (29 October, 1877 - p.3) MR ROBERT BUCHANAN AND EDMUND YATES.—Mr Buchanan’s long silence, in the face of Mr Edmund Yates’ animated rejoinder upon the article in the Contemporary Review, must not be accepted as an indication that he intends to pass it over in contemptuous silence. He has, in fact, been engaged in the incubation of a reply which shall for ever overthrow his adversary. Avoiding the somewhat personal, not to say the chemical character of Mr Yates’ manifesto, Mr Buchanan proposes to heap coals of fire on that gentleman’s head, by attempting to prove, inter alia, that he was not the actual writer of some of the novels which are in circulation under his name. Mr Buchanan’s rejoinder will be published in a few days, I know that he offered it for publication in a high-class daily paper, but the editor peremptorily declined to have his journal mixed up in such a controversy.—Mayfair. ___

The York Herald (31 October,1877 - p.5) The Contemporary Review for November contains a second article under the head of “Signs of the Times,” entitled “Fashionable Farces.” It is sufficiently racy, and will doubtless come in for a good deal of attention. But it is not, as some will suppose, from the pen of Mr. Robert Buchanan. The author is, I am told, one of the most clever dramatic critics of the day. ___

The Sporting Times (10 November, 1877 - p.1) |

|

|

The Argus (Melbourne) (8 December, 1877 - p.4) LONDON TOWN TALK. (FROM OUR OWN CORRESPONDENT.) LONDON, Oct. 26. . . . The clubs are still discussing the case of the World’s “scrofulous Scotch poet.” So personal an article has not appeared in any English journal since Theodore Hook edited the John Bull, nor has such language been used in print since Swift’s day. At the same time Mr. Buchanan’s attack was itself a personal one. He had quite a right to express his opinion about the personality of the papers in question, but not to gibbet any individual in connexion with them. The onslaught also appears to have been quite gratuitous and I am bound to confess if any man made a personal attack on me in any contemporary print, I should reply to him not with the feather end of my pen. Moreover, if Mr. Yates’s account of his relations with Mr. Buchanan is as he has stated them to be, the Scotch poet has no right to complain of his punishment; for he has combined “ingratitude” and “traitor’s arms” in a very inharmonious manner. Still, I hope there will be an end to these amenities of literature, which irresistibly remind me of a certain poem of Swift’s epoch, where two—well, let us say members of the Ramoneur Association—belabour one another with their soot-bags, to the great disgust of the general public. I am glad that the envoy whom the King of Dahomey is about to send hither “to gain an idea of the character of our civilisation” did not arrive this month, so that we may hope that little essay on the Scotch poet will escape his observation. It is certainly as “savage” as anything in Dahomey. _____

From The Contemporary Review - November, 1877 - Vol. 30, pp. 1041-1054.

SIGNS OF THE TIMES. II.—FASHIONABLE FARCES. THERE is, in this much-belauded little island, a relic of barbarism known as the Lord Chamberlain, whose chief business it is to see that only the right sort of ladies are admitted to a levée crush; and attached to the Lord Chamberlain, as a sort of literary appendage, is an individual known as the Licenser of Plays. Why plays should be “licensed” at all is another matter. Why dramatic authors should be subjected to a supervision which poets, novelists, and newspaper editors are generously spared, may well awaken reasonable speculation and wonder. It is well known however, that the Lord Chamberlain is virtuous; so must be the literary expert who tells him what is and what is not to receive a license. The last holder of the licensing office carried his supervision not merely to the extent of preventing the importation of questionable pieces from France, and of forbidding the performance of home-bred political satires;—he went much further, and objected strenuously to such lines as “O all you host of heaven! O earth! what else? This passage, as well as hundreds more which will occur to every Shaksperean reader, would, if it had appeared in the manuscript of any modem dramatist, have either been softened down to nothingness or expunged altogether. Stranger still, the functionary objected with all his might—and his might in this instance really made itself felt—against the repetition on the stage of the word God. “Or that the Everlasting had not fixed would have to be softened into “Or that the Everlasting had not fixed 1042 an alteration which, to say nothing of its poetical flabbiness, is merely throwing unnecessary difficulties in the way of unaspirated tragedians. Indeed, we are not so sure but that “the Everlasting”—being itself an expression savouring of profanity—would have been altered into “Providence,” or some other secular ambiguity. It is necessary, perhaps, to explain a little the present prospects of the English stage. Thanks partly to unwise clerical crusades, and partly to intellectual indolence, English students have been frightened away from the theatre, only visiting it on rare occasions, say once a year to see a pantomime, or once in ten years to witness the phenomenon of a Salvini. Many of them doubtless believe it to be in a bad way, and much of this belief is owing to the fact that it requires a licenser to look after its morals. Now, here as elsewhere, English students are labouring under a grievous mistake. The drama, as it exists, is well worth serious study, and without serious study it is not to be judged or understood. There is to be witnessed in England, nowadays, dramatic work as good, both on the part of author and actor, as may fairly be expected in so busy and so hasty an age as ours—work, at least, which may advantageously compare, in point of total effect, with the work of the age in verse-writing or in prose fiction. Before proceeding to form an estimate of this work, however, the student should disabuse himself at once of two haunting and mistaken impressions—(1) that a dramatic work is to be judged simply as literature, and (2) that dramatic literature, to be really elevated, must be written either in Greek trimeters or English iambics. More prejudice than can well be conceived has been aroused by the hallucination, still to be found in literary circles, that a great play must of necessity be in verse, and divided into five acts, A completely successful and completely interesting dramatic idyl by Mr. Boucicault or Mr. Wills—say “Arrah-na-Pogue” or “The Man o’ Airlie”—affords more hope for the drama than would the production of scores of undramatic tragedies; just as there is a thousand times more hope in the advent of a Jefferson or a Febvre, though neither of these admirable actors belongs to the sock-and-buskin school, than there would be in the resuscitation of a Vincent Crummles, however stately, or a Mr. Wopsle, however gifted. Our best drama takes the complexion of the times, and wears an easy undress, instead of using the cothurnus or the mask. To judge a modern play in its totality, to appreciate all its effects of harmony and art, one must see it from the front of a theatre, well put upon the stage, well acted, and carefully stage-managed. Till it appears in this final shape, it is altogether nondescript, scarcely to be entitled a play at all. Meantime, while English authors and actors have been working their hardest to establish a home-school of drama, their efforts have been more or less neutralized by contagious Continental influences. The late Licenser of Plays, animated by a too blind enthusiasm of morality, thought he was doing a wise thing when he forbade the performance in this country of the principal works of Dumas Fils and Sardou. Now, dramas of this class, though doubtless open to the criticism which has been lavished upon them, and which has caused them to be classed in France under “L’École brutale,” are undoubtedly works of art. They are, moreover, fiery social satires, and true satire is never entirely unwholesome. _____ * It is perhaps needless to say that the order of this performance is imaginary, and that “Madame attend Monsieur” and “Toto chez Tata” were not performed on the same evening. _____ 1048 Soon the narrative is pointed by an imitation of the lorette’s walk. Chaumont hitches up her petticoats, assumes what is known as the “Grecian bend,” walks mincingly as if on high-heeled boots, and shows a dazzling amount of silk stocking. At last, when everybody is rendered desperate by her revelations, her father takes her by the hand, and recommends her in future to travel, not in a lady’s compartment, but in a smoking carnage. So the curtain falls on an enraptured house. Curious to ascertain what the best sort of “adaptation” is like, we made our way recently to the Prince of Wales’ Theatre—an establishment distinguished for its Robertsonian comedy and its Robertsonian acting. The Lord Chamberlain having said it was 1049 all right, that our morals were quite safe, we paid our money without scruple. The play announced was “Peril,” an adaptation of “Nos Intimes,” and its leading feature was a “seduction scene,” in which Miss Robertson was chased and chivied round a stage absolutely buried in upholstery. How the lady managed to move about without damaging many of the lighter articles of furniture, was matter of earnest speculation, in which the motive of the play was quite forgotten. Its chief points seemed to be (1) its splendid real furniture, and (2) its glorious new costumes from Paris. There was a little of what is called “character” acting, notably by Mr. Arthur Cecil; but the general impression, pace the upholstery and dresses, was that conveyed by first-class amateurism. The whole affair seemed to bear the same relation to the real drama as “the newest thing in journalism” does to real literature. The first inspiration was obviously from Paris, but the play was not Sardou’s, and the performance was certainly not Parisian. “Now that the Lord Chamberlain has visited the Criterion Theatre, and has informed both Mr. Albery and Mr. Wyndham that he sees nothing to object to, I suppose we may all go in perfect safety. There are difficulties in the way, however, inasmuch as the virtuous indignation of the British public at the idea of anything immoral being placed upon the British stage is filling the theatre to excess.” This, though sarcastic, is quite true. The “Pink Dominos” was falling very flat indeed when the critic of the Daily Telegraph, in a manly and outspoken article, took strong objection to its plot and dialogue. “Thus bad begins, but worse remains behind.” We have it on the authority of the newspapers of the period that on the conclusion of a recent fashionable wedding the numerous bridesmaids, suitably attired in “pink,” repaired to witness the performance of this latest and lowest Parisian farce, where, in the house of one Sir Percy Wagstaffe, we are introduced to the following characters: Sir Percy himself and his lady, Mr. and Mrs. Greythorne, and Mr. and Mrs. Tubbs. Lady Wagstaffe is a gay woman of the world, Mrs. Greythorne is a simple creature with the most implicit faith in her husband’s goodness, and Mrs. Tubbs is an elderly lady with severe notions of moral propriety. The husbands are, all three, men of dissipation,— Mr. Greythorne, perhaps, being the least immaculate, inasmuch as he deliberately deceives a young and charming wife; and to each of these three gentlemen lying comes so easy that it is by no means difficult to conceal the secret of “vagrant amours.” Things being at this pass, Lady Wagstaffe and Mrs. Greythorne, determined to test the virtue of their respective husbands, send to each of them a letter supposed to be written by an unknown lady, and containing an invitation to supper at Cremorne, where there is to be a masked ball. The real writer of both letters is Rebecca, Lady Wagstaffe’s maid. The gentlemen receive the letters, fall into raptures at the possibility of “une bonne fortune,” and individually invent excuses for not passing the evening at home. At the same time Mr. Tubbs—in the absence of Mrs. Tubbs, who has gone to visit a sick friend—also determines to go to Cremorne. 1053 Act the second begins in the Cremorne Restaurant, showing a coup d’œil of doors opening into tiny supper-rooms for “private parties.” Here the ladies and the lady’s maid, all masked and wearing pink dominos, make their appearance. Now begins, fast and furious, what is called the “fun” of the performance. Lady Wagstaffe is made hot love to by Mr. Greythorne, Mrs. Greythorne is similarly wooed by Sir Percy Wagstaffe, while Rebecca in her turn is pursued by an errant nephew of Mr. Tubbs. Tubbs himself, in a state of intoxication, is discovered offering supper to a “young lady” who has come to Cremorne with her “mamma.” Confusion follows on confusion, in a manner too pantomimic for description. The third act takes us again to the drawing-room of Sir Percy. The mendacious gifts of the husbands now come into full swing. It is explained that they had from the beginning seen through the trick, and had been having a hearty joke at the expense of their wives. All is forgiven, and Rebecca, the skittish maid, is taken into the service of the severe Mrs. Tubbs. The curtain falls on a pretty picture of conjugal bliss. We come back to the point at which we began this article. The very hint of a possible suspicion that a farce might be “suppressed” has, we see, sent crowds to witness the representation. Once label fruit “forbidden,” and it will be plucked at all hazards. “One must see the ‘Pink Dominos,’” says dear Lady Tippins, “because everybody says the Lord Chamberlain ought to have suppressed it, and may suppress it, you know.” Why, in the name of all that is honest, this shifting of the burthen of virtue upon the shoulders of a salaried official? If a play is bad, let the public hiss it off the stage. If it is silly, let silly people go to see it. But to have our morals regulated from above, and to leave the fate of the drama in the hands of a paternal sciolist, is a condition of affairs not to be thought of. The true antidote for bad French “adaptations” is good English plays of home manufacture; and good English plays would be more plentiful if authors of merit had sufficient dignity and self-respect to refuse, at any price, to do the unclean work of “adaptation,” or even “expurgation.” As for the English drama, it will doubtless live on, notwithstanding these foolish and unwholesome importations; but so long 1054 as it feels either the substance or the shadow of any supervision but that of the spectator’s conscience, it will certainly continue unworthy of England and Englishmen. (Note.—To the first article of this series (“The Newest Thing in Journalism”) the editors of the several papers criticized replied in their own columns. Having been hit, it was only natural that they should hit back, and we certainly hare no fault to find with them for this. Indeed, we should have been glad if they had been able to make a better defence. But we are sorry that two of them allowed themselves to ascribe our strictures, which were made solely on public grounds, to an endeavour on our part by “sensational” means to make up for a fall of circulation consequent upon the setting up of a rival publication. The theory is a comfortable one to them in their circumstances, and we feel sorry to rob them of the solace of it; but all the same we have to say that there has been no fall of circulation, and therefore no effort needed to recover what was not lost. And we are still more sorry that one of them—the Editor of The World—made our article an occasion for showing that “The Newest Thing in Journalism” could descend to a lower depth even than we had supposed. In a way for which there is no precedent in literature, he produced a vitriol bottle, and attempted to damage the face of his critic beyond recognition. The critic he assumed to be Mr. Robert Buchanan, and named him accordingly. Mr. Buchanan writes to us as follows:— “SIR,—Mr. Edmund Yates, calling himself the Editor of The World, has recently published in that journal a personal attack upon myself, in which he treats his readers to an account of our acquaintance sixteen years ago; affirms that he ‘saved me from starvation,’ that he lent me money, and that, in gratitude for these services, I ‘dedicated a book’ to him. For full particulars I must refer you to The World itself. At the time of its publication, I was many hundreds of miles from London, and I have not yet determined what course of procedure will best vindicate my own reputation and be of most public benefit. Meantime, I think I may safely leave my case to the moral analyst, who will be able to appraise the production of Mr. Edmund Yates at its true worth. As we print this letter, a copy of The World for October 24th reaches us. From this we gather that the Editor, after his furious attack on Mr. Buchanan, suddenly reflected that he might after all have been attacking the wrong person, and wrote off to a lady in Italy, asking her if she was his critic! This lady, instead of imitating Mr. Buchanan in his silence, replied in haste, asserting her innocence. Had she not done so, we might have had a still more terrible exhibition, in the shape of assault and battery No. 2. _____

The Sheffield Daily Telegraph (1 November, 1877 - p.2) OUR LONDON LETTER. LONDON, WEDNESDAY. . . . Mr. James Gordon Bennett has just been fined £2,000 for a libellous advertisement which appeared in the New York Herald. Mr. Robert Buchanan, in the November number of the “Contemporary Review,” writes that he is considering what steps he shall take with respect to Mr. Yates’ recent article in the World. Mr. Buchanan has another sprightly and severe article in the “Contemporary,” and severely handles our “fashionable farces” adapted from pieces at the Palais Royal Theatre, the basis of which is always a breach of the Seventh Commandment. These nauseating dramas which, like “the newest thing in journalism,” Mr. Buchanan attributes to the corrupting influence of the French Empire, are not only bad in themselves, but are preventing the production of good plays. English theatrical managers are becoming more and more shy of home productions, and give absurd prices for the right to adapt French plays. They not unfrequently burn their fingers, for English actors cannot always exhibit that light sparkle which is the only good characteristic of these plays, and then the piece wont go down. When these plays succeed they owe their success to downright vulgarity. The motif of all of them is the same—that marriage is an absurdity, and that every husband has the right to deceive his wife and every wife her husband. ___

The Falkirk Herald (1 November, 1877 - p.6) —It is reported that Mr Robert Buchanan has prepared an answer to Mr Edmund Yates’s article “A Scrofulous Poet” which appeared in the World. If it is true that “the editor of a leading newspaper to whom Mr Buchanan offered his rejoinder for publication declined to have anything to do with the business” we may reasonably expect it is what our Yankee friends would call “hot.” Both combatants have had experience in journalistic fisticuffing, and know well how “to hit straight from the shoulder.” ___

The Western Mail (3 November, 1877 - p.2) I am curious to see Mr. Robert Buchanan’s reply to the terribly scurrilous attack made on him by Mr. Edmund Yates with regard to his article on the “Latest Thing in Journalism.” Mr. Robert Buchanan can hit hard when he likes, and in the article on which he is engaged he will no doubt be merciless. It is said he is going to deny that Mr. Yates is the author of the novel “Black Sheep,” the best which is published in his name. If he does bring forward this charge it will, of course, be only one head of his indictment, for he is as great an adept at scurrility as Mr. Yates. ___

Berrow’s Worcester Journal (10 November, 1877 - p.6) The Contemporary is, as usual, wonderfully solid, and the question really arises whether one small mind if capable of digesting all this literary food. ... Mr. Alfred Austin, on the poetic interpretation of nature, is uncommonly well worth reading. Those predisposed to the lighter kind of literary food will probably turn to the only unsigned article written, according to Mr. Yates, by Mr. Robert Buchanan, who chose to denounce the newest thing in journalism, and led to a bludgeoning proceeding of which we have by no means heard the last. Mr. Buchanan is said to be executing revenge by means of an article on poetic satire. The article it seems is to tell the public that some of the books passing under the name of Mr. Yates were, in fact, not written by him. Such puerility is only worthy of a past period in literature which cannot be too soon forgotten. What Mr. Buchanan—if the writer be indeed Mr. Buchanan—discourses upon in the Contemporary of this month is fashionable farces, as showing a decline in public morals and taste. Why should arguments be drawn from English adaptations of farces from the Palais Royal? There has unquestionably been an improvement in the dramatic taste of the public, nothing much to boast about, perhaps, but an improvement for all that. We have not got to the sublime pitch yet, but we have recovered greatly since the time when people used to go and see wretched burlesques, destitute of wit and not free from indecency, and not possessing even the merit of giving good music. ___

The Graphic (10 November, 1877 - p.7) In the Contemporary, Mr. F. W. Newman writes on “The War Power,” by which he means the power a Government has of involving in war the nation which they represent. ... —Mr. Donaldson furnishes an amusing article on the “Characters of Plautus,” and then follows a paper also on a theatrical subject, namely, Mr. Robert Buchanan’s attack on some of the popular plays of the day, such as the Pink Dominos, the Great Divorce Case, &c. We have seen most of these pieces, and are unable to discover the immoralities which this modern Histriomastix discovers in them. To us they seem to belong to an unreal world, the characters of which are about as devoid of moral responsibility as the clown and pantaloon in a pantomime. _____

Back to Essays or Robert Buchanan and the Magazines

|

|

|

|

|

|

|