|

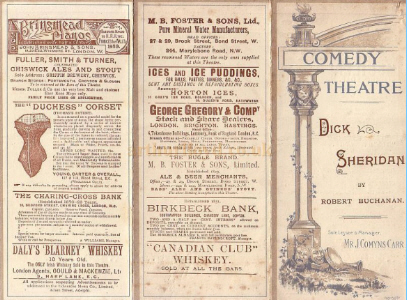

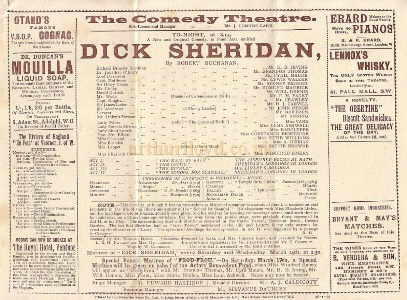

[Programme for Dick Sheridan at the Comedy Theatre. Click the pictures for readable versions.]

The Morning Post (5 June, 1893 -p.4)

Mr. E. H. Sothern, whose success on the American stage is maintaining the hereditary celebrity of his name, is to impersonate the principal character in the new play which Mr. Robert Buchanan has written in illustration of the life and times of Richard Brinsley Sheridan. The piece will be produced in the first instance on the New York stage, but will doubtless find its way to London in due course.

___

The Derby Daily Telegraph (21 July, 1893 - p.2)

The advent of Mr. Comyns Carr to the ranks of theatrical managers was hailed with pleasure by most people, who anticipated excellent things from his experience and fertility of resource. This pleasure will be rather transferred if, as is believed, the first production during Mr. Carr’s first season at the Comedy is a play by Robert Buchanan, based on the life of Sheridan. Has even Mr. Comyns Carr despaired of fishing up attractive novelties from the theatrical sea? or is he taking a leaf out of other managers’ books, and testing his public with a well-practised hand?

___

The Echo (14 August, 1893 - p.1)

There has been a storm in a tea-cup over Sheridan lately in the literary world. Advance paragraphs had gone the round of the newspapers informing us that Mr. Oscar Wilde’s new play for the Garrick would be based on the story of Miss Linley’s elopement from Bath with her future husband, Richard Brinsley Sheridan, and the title, we were assured, was “Sheridan; or, The Maid of Bath.” Now, it happened that Mr. Robert Buchanan had a play ready for Mr. Comyns Carr’s new venture at the Comedy based on this very subject, and previously shown to Mr. Hare, only to be voted unsuitable for the Garrick caste. Here was splendid material for a charge of plagiarism—at any rate, it seemed a remarkable coincidence. But, unfortunately, the fun is spoiled by latest advices, for we learn that the new Wilde play is, to quote the grandiloquent language of official assurances: A comedy of modern manners.

___

The Illustrated Sporting and Dramatic News (19 August, 1893 - p.20)

MR. ROBERT BUCHANAN is troubled by the fact that a new play by Mr. Oscar Wilde, dealing with the early life of Sheridan, is to be produced at the Garrick Theatre, Mr. Buchanan having written on the same subject, and a “Yankee Pirate” having made use of his ideas. He makes other remarks, which will probably lead to a statement from Mr. John Hare, and possibly Mr. Wilde will also have something to say on the subject.

___

The Globe (23 August, 1893 - p.3)

SHERIDAN’S LOVE-STORY.

There has been much to-do, of late, about plays said to have been written by more than one distinguished man of letters on the subject of “Sheridan, or The Maid of Bath.” A theatrical gossipper announced, in error, that Mr. Oscar Wilde had produced such a play for Mr. Hare. The fact is that the author of the work is Me. Robert Buchanan, who has arranged, apparently, for its production by Mr. Comyns Carr at the Comedy. The matter has been further complicated by the statement that an American theatrical manager had discarded Mr. Buchanan’s drama in favour of one on the same topic by an American writer. So it seems likely that, before very long, there will be an English and a Yankee “Sheridan” in the theatrical field.

It is taken for granted, from the title of Mr. Buchanan’s play, that it deals with the circumstances under which the beautiful and gifted Miss Linley, long known as “The Maid of Bath,” became the wife of the author of “The School for Scandal.” Sheridan did not confine himself to writing drama—he lived it; and at one period it was drama of a romantic, not to say stirring, kind. The facts are extant in the biographies of Sheridan, but they are not familiarly known. Nor is this surprising, for the world is not too well acquainted even with Sheridan the orator and statesman: it thinks of him almost wholly as the theatrical manager, the playwright, and the wit.

But before Sheridan had produced “The School for Scandal,” nay, before he had produced “The Rivals,” he had had much personal knowledge both of competition in love and of public slander. It came about in this way/ When he was about nineteen, that is to say, in 1770, the Sheridan family, including Thomas Sheridan and his two sons, Charles and Richard, went to reside in Bath. There they, naturally enough, made the acquaintance of another family connected with the profession of art, the Linleys, of whom the father was well known as a composer and music-teacher, while the daughter, Elizabeth, was, though still very young (about seventeen), already quite famous as a concert-singer. She had, as we have said, personal as well as intellectual charms, and had had many admirers. Among these, notably, was a Mr. Long, an old man possessed of considerable property, who had laid himself and his wealth at her feet. At this point we may quote from the story as told in the issue of the London Magazine for September 1772, to which an esteemed correspondent has courteously recalled our attention:—

“The daughter confessed that the offer was good, but then the age—the age of the lover she could never reconcile to her inclinations: the father confessed all this very true, but then the money—the money ought to reconcile everything.”

In the end, “the father insisted on the thing, and the daughter promised to comply”; but, when the time came to fulfil the promise, her fortitude broke down, and she begged her venerable lover to release her. This, we are told, he did, responding willingly to the demand of the father that he should pay a large pecuniary fine for not having carried out his portion of the contract. Such, at least, is one version of the tale. According to another, Mr. Long backed out of his engagement, and was compelled to tender a substantial solatium. This is the version accepted by Mr. Percy Fitzgerald, and the one on which Foote based his comedy of “The Maid of Bath,” in which Mr. Long figured as Mr. Flint, a miser, and Miss Linley as Miss Linnett.

The Long incident, however, was as nothing to that which was destined to follow it, and which may be described as the Matthews tragi-comedy. Among the visitors at the Linleys’ house was a Captain Matthews, who, though married and much older than Elizabeth, nevertheless persecuted her with his addresses. He appears to have laid siege to her with all the arts of a libertine, supported by his position as friend of the family. At last Elizabeth became alarmed, and looked about her for advice. The Linleys and Sheridans were now intimate. Both the sons had fallen in love with the girl, who, though she had not admitted that she cared for the future dramatist and politician, had at least confessed that she preferred him to Charles. She now showed her preference, rather markedly, by confiding to Richard—he was now just twenty, and full of the reckless gallantry of his age and race—the particulars of Matthews’s persecution. She seems to have doubted her father’s capacity to protect her; and Sheridan, on his side, seems to have known Matthews sufficiently well to think that she ought to be removed far from the sphere of his influence. Accordingly he proposed to her that she should fly to France and take temporary refuge in a convent. He himself was to be the partner of her flight, “the wife of one of his servants” going with them to play propriety. Elizabeth accepted the proposal, and the elopement took place. At Calais, or Before, Sheridan represented to his fair companion that, by way of stopping, if necessary, the voice of scandal, it would be better if they were privately married. Miss Linley, one gathers, was nothing loth, and the ceremony appears to have been gone through. Then, no sooner was the girl safely transferred from her convent to the house of an English doctor at Lisle, than the father swooped down upon her from England, and carried her back to Bath.

Here we may quote again from the above-named contemporary narrative:—

“Soon after the elopement had taken place, it was buzzed about in Bath that Mr. M——ws had been privy to it, which he constantly persisted in denying, and at the same time unluckily took some indecent liberties with Mr. Sheridan’s name. Officious persons are never wanting, and on young Sheridan’s arrival he was informed that Mr. M——ws had used his name disrespectfully. By the laws of honour he called him to account for this, and a duel was the consequence. . . . This duel was fought in a tavern, in the neighbourhood of Covent Garden, in London, and Mr. M——ws, being disarmed, was obliged to beg his life. But this circumstance being, it seems, by the laws of honour deemed ungentlemanlike, Mr. M——ws was actually obliged to leave Bath and fly to the mountains of Wales to forget his infamy among strangers. But scandal travels with surprising speed, and the news of the duel reached Wales almost as soon as he did himself. . . . He found that there was but one method of regaining his reputation and his peace, and that was by challenging Sheridan to a second combat. With this resolution he left Wales, and soon appeared in Bath.”

We need not linger on the details of the combat, which was, apparently, somewhat sanguinary. Suffice it that “Sheridan, having received some dangerous wounds, was left on the field with few signs of life.” Happily, these indications were falsified, and in due time he was convalescent. “Miss Linley,” says the London Magazine, “had been denied the favour of seeing him, even though she begged it by the tender appellation of husband. Whether they are married or not, their respective parents have since that time been very industrious in keeping them separate.”

This was published in September, 1772. It was, however, found impossible to keep the lovers permanently apart, and so Linley père and Sheridan père had eventually to surrender, Sheridan and the “Maid of Bath” being duly married in April, 1773. Whatever, therefore, may be the nature of Mr. Buchanan’s play, it ought, if it claims to be historical, to end (so far) happily. Beyond that, much may be permitted to the playwrights’ fancy, for the story which we have condensed above has, in minor points, many variants, and is susceptible, consequently, of artistic manipulation.

___

The Illustrated Sporting and Dramatic News (2 September, 1893 - p.13)

MR. ROBERT BUCHANAN’S new play, Sheridan, respecting which there has been such an acrimonious correspondence on both sides of the Atlantic, will be produced shortly at the Comedy Theatre, under the management of Mr. Comyns Carr. Mr. Buchanan declares it to be “entirely original,” but of course it will follow on the lines of the real incident in the life of the author of The School for Scandal. Mr. Buchanan has ample materials in the wooing of the beautiful Miss Linley, of Bath, who in Lent, 1773, made a great sensation in London by her charming oratorio singing. Sheridan adopted extraordinary disguises to meet his fair one. For several nights masquerading as a hackney coachman, he drove Miss Linley home after the concert. They had already been secretly married at Calais, but the opposition of parents and guardians had prevented their making the marriage known. However, about a year after the clandestine match, the young couple overcame parental objections, and were established in a home of their own. The young wife retired from the musical profession to the regret of thousands, for she possessed one of the sweetest and most sympathetic voices ever heard. But Miss Linley, although so universally admired, disliked a professional career, and resigned public life without regret. She was a faithful and devoted wife, and many of her contemporaries spoke of Sheridan’s charming partner with the greatest enthusiasm. Not a little curiosity will be felt by playgoers in the new piece Mr. Buchanan has founded on this interesting romance of real life, in which the brilliant author of our greatest comedy was the hero.

___

New-York Daily Tribune (6 September, 1893 - p.6)

E. H. SOTHERN AS SHERIDAN.

At the Lyceum Theatre last night E. H. Sothern presented a new play before the best audience that has yet assembled in New-York this season. It was called “Sheridan, or the Maid of Bath,” and was written by Paul M. Potter. Mr. Sothern is an actor of great and deserved popularity. He continues, as each year passes and as he shows himself in each new part, to exhibit versatility, care, study, feeling and charm. His impersonations are always looked forward to with interest, and have thus far been received with favor. He presents Richard Brinsley Sheridan as an energetic and ambitious young man, fired by a youthful love, impulsive, hot-headed and quick-tempered, but also generous, tender and self- sacrificing. Such a personality is bound to be agreeable to an audience, whether the name given to it be Sheridan or John Doe. Investing a character of this quality with circumstances calling its attributes into vigorous play, Mr. Sothern makes it picturesque and fascinating. The faults as well as the virtues of his Sheridan are lovable, and so he adds another to his list of enjoyable dramatic creations.

The lesser personages of the play are for the most part historical people whose lives in reality came in contact more or less with that of Sheridan, but by no means, in many cases, in the ways in which they are here represented. The most interesting one, of course, is Miss Betty Linley, a part agreeably played by Miss Grace Kimball. The costume of the time is becoming to her, and her gown and her powdered hair made her a most attractive picture, to which a worthy and engaging companion was furnished by Miss Marion Giroux as Miss Dorothy Neville. Charles Harbury was rather ponderously violent and sportive as David Garrick, and R. Buckstone was elastic and unrestful as Michael Kelly. A most finished and agreeable impersonation of Dr. Thomas Linley was given by C. P. Flockton. He was composed, correct and dignified. Morton Selten, as Captain Matthews, the villain of the play, exhibited his usual grace of bearing and propriety of action. Mrs. Kate Pattison-Selten appeared as Lady Erskine, and a small part was prettily played by Miss Rebecca Warren.

The play is worked to satisfactory climaxes at the ends of the acts, but for the rest it has something too much of talk and preparation, rather noisy at time, and a lack of action in the best sense and development of character. The attempt is made to introduce the originals of some of the characters which Sheridan used in his plays. The plan sounds promising, b ut one of the results of it, which should not have been hard to foresee, is that persons whom the public has been used to observe saying and doing brilliant and incomparable things, are here found saying and doing comparatively commonplace ones. David Garrick is shown implicated in a love affair, sadly inconsistent with another drama which has for some time enjoyed a degree of popularity. A note in the programme admits that his connection with the plot is not historical, but even with this apology, the spectacle is unpleasant.

The setting of the stage is sumptuous and in faultless taste. The picture of Dr. Linley’s library is a most excellent stage arrangement, and that of the manager’s room at the Covent Garden Theatre deserves scarcely less commendation. The costumes are rich and beautiful, and every detail of stage management is attended to with the thoroughness which invariably marks productions at this theatre.

___

The Graphic (23 September, 1893)

The American dramatist who determined to make the author of The Rivals and The School for Scandal the hero of a play has stolen a march upon Mr. Robert Buchanan, who is known to have done the same. The American piece has already been brought out by Mr. Sothern at the Lyceum Theatre, New York. It is a comedy in four acts, entitled Sheridan, or The Maid of Bath. The Maid of Bath is, of course, Miss Linley, afterwards Mrs. Sheridan. The piece depicts the courtship of these twain at Bath, and has a scene in the famous Pump-Room. It also introduces us to Covent Garden Theatre on the momentous night of the production of The Rivals. Mr. Sothern plays Sheridan, Miss Grace Kemball, Miss Linley. The piece seems to have been received with favour.

___

The Era (30 September, 1893 - p.7)

THE DRAMA IN AMERICA.

_____

“SHERIDAN; OR, THE MAID OF BATH.”

A Play in Four Acts, by Paul M. Potter.

Produced at the Lyceum Theatre, New York, Sept. 11th, 1893.

Richard Brinsley Sheridan ... Mr E, H. SOTHERN

David Garrick ... Mr CHARLES HARBURY

Michael Kelly ... Mr R. BUCKSTONE

Dr. Thomas Linley ... Mr C. P. FLOCKTON

Captain Matthews ... Mr MORTON SELTEN

Captain Paumier ... Mr SAMUEL SOTHERN

Mr Harris ... Mr JOHN FINDLAY

Mr Barnett ... Mr TULLY MARSHALL

Anatole ... Mr HOWARD MORGAN

Footman ... Mr ERNEST TARLTON

Elizabeth Linley ... Miss GRACE KIMBALL

Dorothy Neville ... Miss MARION GIROUX

Lady Erskine ... Mrs PATTISON SELTEN

Lady Shuttleworth ... Mrs ADDISON-PITT

Mrs Matthews ... Miss REBECCA WARREN

(FROM OUR OWN CORRESPONDENT.)

NEW YORK, SEPT. 19, 1893.—This play has a history. In April, 1891, Mr Richard Mansfield, being in want of a new piece, commissioned Mr Paul M. Potter to write a play. Mr Potter sketched an elaborate scenario founded on Sheridan’s well-known love affair. Mr Mansfield was not pleased with it, and the matter dropped.

About twelve months later Mr Daniel Frohman, in casting about for a new play for Mr E. H. Sothern, regarded with some favour Mr Robert Buchanan’s project of fitting that popular young actor into the romance of Richard Brinsley Sheridan. In due time the MS. was finished and placed in Mr Frohman’s hands. That manager, who has considerable literary ability and an accurate knowledge, not only of the capacities of his players, but of the dramatic fare suited to the taste of American audiences, wished to make certain alterations in the play. Mr Buchanan refused to consent to this proposition. He had acknowledged in handsome terms the wisdom displayed in Mr Frohman’s revision of Squire Kate for the American stage, but on this occasion he insisted that no hand save his own should amend a line of the Sheridan play. As the author and his work were separated by three thousand miles of ocean, Mr Frohman, who wished to put the piece into rehearsal, finally decided that, as he could neither alter the play himself nor secure the dramatist’s present skill in revision, the manuscript should be returned to its writer. The manager, however, paid Mr Buchanan $1,000 for his trouble in the matter, and at this point it was believed that the affair was amicably settled.

But Mr Sothern, who had set his mind on appearing in a costume play, was still unsatisfied. A proposition was under serious consideration for a time to order a drama on the theme of David Garrick. Sothern, however, believed that any new work on this subject must be judged unfavourably in contrast with the David Garrick in which his father had earned renown. In this predicament Daniel Frohman remembered that Mr Potter had written a Sheridan play for Mr Mansfield. Mr Potter was sent for, his scenario was examined, and he was requested to complete the piece for Mr Sothern. One of his scenes was not considered so interesting as that of Mr Buchanan, and Mr Frohman offered the Scotch dramatist 2 per cent royalties for the use of his act to be added to the Potter play. The offer was declined, and Mr Sothern was obliged to be content with the American version. Mr Potter assures me that he not only never saw the Buchanan MS., but that in several instances Daniel Frohman cut out certain lines in his piece because they read like Mr Buchanan’s, a resemblance easily accounted for by the fact that both dramatists adhered closely to the historical witticisms and adventures of their hero. The American play was produced last week at the Lyceum. It was received with high favour, and Mr Sothern’s seventh season under the management of Daniel Frohman promises to be quite as successful as his earlier engagements.

Sheridan is a comedy with strongly dramatic elements. Its first scene takes place in the Pump Room, Bath, in July, 1774. Captain Matthews, a handsome but scampish young officer in the Fusiliers, has married and deserted a pretty country girl, and is now preparing to take as second wife the beautiful and talented young actress, Miss Elizabeth Linley. The lady knows nothing of this project, and her father, who has a fancy for the famous David Garrick as his son-in-law, is equally ignorant of the designs formed by the audacious Captain. But the young officer lays his plans with an ingenuity that deserves success. Impressing his friend, the impecunious wit, Richard Brinsley Sheridan, into his service, he secures a position for the young writer as tutor to the Ladies of the Linley household. Dr. Linley at first hesitates to receive so renowned a profligate as Sheridan into his family; but, being quite easily persuaded by Captain Matthews that the young man is not so wild as he is said to be, and is, moreover, the certain heir of a rich uncle in India, the old gentleman finally dismisses his doubts, and welcomes the new tutor with enthusiasm. Sheridan’s fortunes have been for some time at a low ebb, and the salary attached to his office will relieve his immediate necessities. There is a romantic interest in his engagement, arising from the fact that Betty Linley and he were sweethearts in childhood. But his hopes of marrying the young lady are dispelled by the Captain, who asserts that he himself is secretly married to Betty. Being now off to the wars he places his young wife under the guardianship of Sheridan, and entreats that gentleman to exert a brother’s solicitude for her welfare. Although dismayed by his friend’s confession, Sheridan has no reason to doubt its truth. He accepts the trust imposed on him; and, after the departure of the soldier to foreign campaigns, will neither make love to Betty himself nor allow any rival suitor to be attentive to his friend’s wife.

being bound to absolute secrecy in this matter, Sheridan gives Betty Linley no clue to his coldness to her advances. The handsome heiress is, however, deeply enamoured of her young tutor, and smiles on him as openly as modesty will permit. This one-sided wooing is continued until an unfortunate accident occurs which removes Sheridan from his position in the Linley household, and earns for him the contempt of all its members, save Betty. His comedy, The Rivals, has been accepted for production at Covent-garden Theatre, and Mr Harris, the famous manager of that playhouse, has paid £200 down as advance royalties on the piece. While Sheridan is joyfully meditating, his apartment is entered by a very good-looking young woman, who presently discloses the fact that she is Captain Matthews’s wife. Hearing that Sheridan is the deceitful young officer’s intimate companion, she has visited him to ascertain the whereabouts of her husband. She has a woful story to tell. The captain has deserted her, she has no food for her child, and the landlord has turned her out of doors. Sheridan, though generously refusing to believe his friend’s perfidy, is not less instant and sincere in his wish to relieve the necessities of the unfortunate, and he impulsively thrusts the £200 paid for The Rivals into her hand. The young woman goes away, unaccountably leaving the money and a bundle of her husband’s letters on the table. The family reassembles a few minutes later, and Mrs Matthews, on returning for her reticule, is discovered. Lady Erskine, a former flame of Sheridan’s, jealously insinuates that the wit must maintain unmentionable relations with a young woman who visits him so late at night. Alarmed at the possibility of Betty discovering the odious character of the man whom Sheridan believes her to have married, the dramatist heroically sacrifices himself. He acknowledges that he is the haggard-looking woman’s lover. There is but one course open after this appalling disclosure, and Dr. Linley immediately takes it by ordering the young tutor out of the house. While making preparations to obey this command, Sheridan has a chance to say farewell to Betty. Miss Linley’s faith in his honour, although shaken, is not shattered. She hastens to hint that even in his disgrace Sheridan may find a way out of his difficulties by marrying the girl of his choice. But the young dramatist, although sorely tempted to betray his trust, remains true to the promise extorted by Captain Matthews, and leaves the house with his secret untold and his misery on his head.

The third act takes place in the manager’s room, Covent-garden Theatre, Jan. 17th, 1775. It is the first night of The Rivals, and Richard Brinsley Sheridan is seated alone nervously awaiting the verdict of his audience. Lady Erskine comes in with a final appeal for the renewal of his affections. The dramatist has neither time nor patience to answer her entreaty diplomatically. Enraged at his indifference, Lady Erskine declares that she has hired a gang of men to sit in the pit to applaud or damn the play at her signal. At this alarming intelligence Sheridan tries to temporise. But the lady will have all or nothing, and, furious at her former lover’s preference for Betty Linley, departs to her box in high dudgeon to give the sign of condemnation to her mercenaries. Thereupon a storm of hisses, hoots, and catcalls breaks forth in the pit. Sheridan’s comedy is ruined. In vain the actors put forth their best efforts; in vain David Garrick, who has come over from Drury-lane to witness the trial of his young friend’s play, goes out before the curtain to quell the disturbance. The comedy is unmistakably damned, and for the first time in his life David Garrick is hissed off the stage. Through their interest in its author, Miss Linley and her cousin, Dorothy Neville, had attended the play. The former lady now comes in search of Sheridan to express her sympathy. Deeply moved, Sheridan makes a clean breast of the affair that brought him under suspicion at Bath. He discovers that Captain Matthews was as false to his friend as he had been to his wife. Betty Linley scornfully denies that she is married to or cares for the perfidious soldier; and a moment later Sheridan has her in his rapturous embrace. At this juncture, Dr. Linley arrives and carries off his daughter indignantly. But Sheridan is lonely only for a moment. Captain Matthews has arrived home from the wars, and after witnessing the disaster of his friend’s play, comes behind the scenes. The angry dramatist is in no mood for such sympathy. He denounces the soldier’s conduct, and openly insults him before a roomful of company. A duel is immediately arranged, and the act-drop descends.

In consequence of the surveillance of the police, the duel between Matthews and Sheridan is fought in the author’s rooms. The weapons are swords, whose clashing steel alarms the young ladies in an adjoining chamber. The victory finally rests with Sheridan, who generously spares the life of his adversary. Unmoved by this clemency, Matthews seeks to prejudice the mind of Betty Linley against her lover by declaring that the dramatist has a “pretty French milliner” concealed behind a screen in his bedroom. To prove his assertion he throws down the screen and discovers his own wife, who had once more come to the good-natured dramatist for succour. To add to his discomfiture, his rival is crowned with new honours by the arrival at this moment of David Garrick, who announces that he has accepted Mr Sheridan’s new play The School for Scandal for early production at Drury-lane. The play ends in general happiness.

From this synopsis it may be seen that Mr Potter has used the main incidents, not only of Sheridan’s life, but of his two famous comedies in the construction of this piece. There are faults in the building up of the play, but the dialogue is witty, the characters well drawn, and the interest fairly continuous. The principal part affords many opportunities for romantic sentiment and light comedy to Mr Sothern, who has admirably sustained his reputation in the character of Sheridan. Mr Buckstone as the eccentric Irish musician, Mr Harbury as David Garrick, and Mr Flockton as the father of the heroine are excellent. The female parts are fairly well acted. The play is handsomely staged and costumed, and has quite hit the fancy of “the town.” Sheridan fills the Lyceum Theatre to the doors nightly.

___

(p.10)

“SHERIDAN: OR, THE MAID OF BATH,” is still the subject of a bitter controversy. Mr Robert Buchanan recently attacked Mr Daniel Frohman, alleging unfair dealings with his play. Mr Frohman and Mr Paul M. Potter, the author of the American version recently produced in New York by Mr Sothern, have replied. Our own correspondent has thrown some fresh light on the whole business, and now we are in receipt of another letter from Mr Buchanan, who deals out libellous accusations so liberally that we are compelled to refuse him publication. Mr Buchanan was very angry, because from his first letter we expunged matter that was libellous; he will be angrier perhaps when he finds that we have thought it necessary to suppress his second altogether.

___

The Illustrated Sporting and Dramatic News (30 September, 1893 - p.28)

OF the two new plays dealing with the life of Sheridan which have recently been written, the New York one has come out first. It is by Mr. Paul M. Potter, who solemnly warns Mr. Robert Buchanan that he will prosecute him if he attempts to reproduce the scenes, heroines, or dialogue invented by him, Mr. Potter, for Mr. Trohmann’s Lyceum production. The warning is, we should think, wholly unnecessary; and when in due course Mr. Comyns Carr presents Mr. Buchanan’s Sheridan with Mr. H. B. Irving as its hero we shall not expect to find it in the least like Mr. Potter’s Sheridan; or, The Maid of Bath. This piece of course deals with the stormy love affairs of Sheridan and Elizabeth Linley, and its chief scenes are laid in the pump-room at Bath and the manager’s room at Drury Lane during the production of The Rivals. In it Mr. Sothern appears as Sheridan, Mr. Harbury as Garrick, and Miss Kimball as Miss Linley.

___

The Dundee Courier (2 October, 1893 - p.3)

Mr Robert Buchanan has at length determined to defend himself in the law courts against the oft-repeated attacks which have been made upon him in respect to some of his theatrical writing, more especially with regard to his play “Sheridan,” as to which some very bitter, and as Mr Buchanan says, maliciously libellous statements have been made. Instructions to proceed have been given by Mr Buchanan to his solicitors. There is reason to believe that if the case comes into the Courts it will have a few lively features.

___

The Nottingham Evening Post (3 October, 1893 - p.2)

MR. H. B. IRVING AGAIN ON THE STAGE.

According to a statement in the “Daily News,” Mr. Henry Irving’s eldest son, Mr. H. B. Irving, whose determination to relinquish the dramatic profession, in order to devote himself to the graver study of the law, was some time since announced, has so far changed his mind that he has consented to play the part of Richard Brinsley Sheridan, in Mr. Robert Buchanan’s drama, which stands next after Mr. Grundy’s “Sowing the Wind,” for production by Mr. Comyns Carr at the Comedy Theatre. Mr. Irving’s latest performances—and notably that of the slowly-poisoned husband in “A Fool’s Paradise,” at the Garrick, early last year—have shown a great advance upon his earlier efforts, and marked him out as an actor of high promise in serious parts.

___

The Bristol Mercury (3 October, 1893 - p.3)

It is stated that Mr A. W. Pinero has abandoned his intention to sue Mr Clement Scott for libel because the latter said that “The Second Mrs Tanqueray” was suggested by a German piece. Although the critic hit below the belt, it was not a matter to go to law about, and it is far better to refer the matter to the arbitration of Sir George Lewis. Mr Robert Buchanan, however, takes up the running, and is going to carry a quarrel with the “Era” into the courts. There are two plays in existence on the life of Sheridan, one by the Scotch poet, who considers he has been plagiarised from.

___

The Illustrated Sporting and Dramatic News (7 October, 1893 - p.13)

IT is reported, and we are anxious to believe the report, that Mr. Pinero has dropped the action for libel which he proposed to bring against Mr. Clement Scott. Such an action would have been as great a blunder as that involved in suggesting even by way of a joke that The Second Mrs. Tanqueray was a plagiary from the German. As against this peaceful news we have, alas! to set the announcement by Mr. Robert Buchanan that he intends to take action against a theatrical contemporary for the statements about his Sheridan play, which have been made in the American correspondence of the paper in question. Here, again, we may suggest in the interests of peace that the angry dramatist would do far better to publish a temperate denial of any mis-statements of which he may have to complain. A libel action makes, at best, an inauspicious kind of advertisement for a new play.

___

Pall Mall Gazette (10 October, 1893 - p.4)

The controversy—if controversy it can be called—over “The Second Mrs. Tanqueray” has come peacefully to an end. But London is never at a loss for a theatrical battle of some kind or other, and the battle over the English and American Sheridans is briskly belligerent. Mr. Robert Buchanan is not at all inclined to suffer quietly encroachments upon his rights, and he has stated his case publicly with a directness and a frankness which recall the disputes of the Humanists. Mr. Buchanan goes for his adversary with uncompromising accusations of a kind which are calculated to startle the readers of his letter. Mr. Buchanan’s charges are direct, and are supported by dates. They are very unpleasant charges. With them we have nothing to do. But it would seem on the face of the case that Mr. Buchanan has been badly treated. His “Sheridan” is said to be the next play on the list for representation at the Comedy Theatre.

___

The Illustrated Sporting and Dramatic News (14 October, 1893 - p.25)

THINGS promise to become lively over the rival Sheridans of the English and American stages. Mr. Robert Buchanan has always been among the most vigorous of controversialists, and it is not likely that he will modify his vigour much when the subject under discussion is one which concerns him so nearly as the authorship of his own play. This play, by the way, when we see it at the Comedy, will introduce Mr. Henry Irving the younger in a part which will allow him to show the stuff of which he is made, and will very likely enable him to impress the playgoing public as favourably as his King John impressed those who saw it at Oxford in his amateur days.

___

The Illustrated Sporting and Dramatic News (6 January, 1894 - p.19)

MR. ROBERT BUCHANAN’S new “Sheridan” play at the Comedy, which will, we believe, prove to be a dramatic work somewhat of the “Sophia” pattern, was to be read at the Comedy theatre on Monday last and placed in rehearsal at once. This, it will be remembered, is the piece in the central character of which Mr. H. B. Irving will recommence his career upon the stage.

___

The Derby Daily Telegraph (13 January, 1894 - p.2)

Mr. Robert Buchanan has the knack of keeping his personality well before the public, and if he does not happen to be running a novel or a drama at the moment a rousing letter on a rousing subject in a daily paper serves his purpose. Before the month is out he will be represented on the play bills of two London theatres, by “The Charlatan” at the Haymarket and “Dick Sheridan” at the Comedy, the last being now in active rehearsal. It deals with the dramatist’s love passages with Eliza Linley—so an inspired friend tells me. It is parlous trying to present so brilliant a personality on the stage. Witness the paltry sucus d’esteme of Mr. Barrie’s “Richard Savage.” Young Mr. Henry Irving, who appears to have abandoned law again for the stage, is to be Dick Sheridan. But why this selection? When he was at the Garrick, playing in Mr. Hare’s company, he seemed a sorry counterpart of his father, wanting élan and self-abandonment in his part.

___

The Stage (18 January, 1894 - p.11)

Dick Sheridan or Sheridan, the new piece by Robert Buchanan, is now being rehearsed at the Comedy, where it will, when wanted, follow Sowing the Wind. Last week I mentioned Mr. H. B. Irving and Miss Winifred Emery as having the two parts Sheridan and Miss Linley respectively. Now I learn that Mr. Brandon Thomas, Mr. Cyril Maude, Mr. Lewis Waller, Mr. Sydney Brough, Mr. Edmund Maurice, Miss Lena Ashwell, and Miss Pattie Browne will also appear in the cast. In the meantime the present programme at the Comedy is attracting good business, and an extra spurt has been given to the matinées in consequence of the interest displayed in the performances by the Baroness Burdett- Coutts, who has secured a private box and a number of seats in the dress circle for every afternoon during the season, so that she may give her youthful friends an opportunity of witnessing The Piper of Hamelin and Sandford and Merton.

___

The Dundee Advertiser (20 January, 1894 - p.4)

Some months ago a violent controversy raged between Mr Robert Buchanan and Mr Frohman, a New York theatrical manager, who had accepted one of the bard’s plays, then sent it back to him, and finally, according to Mr Buchanan, adapted portions of it to his stage, and even kept the name of the Scotsman’s play on the placard. Mr Buchanan, besides applying to Mr Frohman the most libellous epithets, threatened to move the Law Courts against him. Up till now this has not been done. Frohman, on the other hand, warned Mr Buchanan to be careful, for if he attempted to bring the play out in London he should be prosecuted for pirating the American play. Well, Mr Buchanan’s play will soon see the light. It is now in rehearsal at the Comedy Theatre. It will probably be called “Sheridan” or “Dick Sheridan.” It is formed upon incidents in the career of the famous dramatist, and deals especially with his romantic marriage.

___

The Western Daily Press, Bristol (23 January, 1894 - p.8)

LONDON LETTER.

. . .

I have just had a lengthy interview with Mr Brandon Thomas, whose play, “Charley’s Aunt,” is so successful a work. Since his marriage he has resided in Cadogan Terrace, in a splendid suite of rooms, where he may be said to have a domestic environment which any true artist would rejoice in. Mr Thomas is now much occupied with the part which he is to play in Robert Buchanan’s new piece, “Dick Sheridan.” He is hopeful that he will make as great a success in this as in “Sowing the Wind,” in which he has so long been sustaining the leading rôle. Mr Thomas has felt all along that his real strength lay in the more pathetic comedy characters, but not till he got the part of Brabazon in Sydney Grundy’s comedy has he a conspicuous chance of showing his capabilities in this respect. He has been offered £60 a week to return to America to play Charles Wyndham’s parts, David Garrick more particularly; but he has refused the offer. As I was talking to Mr Thomas, sitting near the desk on which “Charley’s Aunt” was written, my eye lighted on a rather old and faded carte de visite which lay near the ink-bottle. “It was while looking at that photograph,” said Mr Thomas, “that I got my first suggestion for ‘Charley’s Aunt.’” It was a photograph of Mr Thomas’s mother, who died about ten years ago. The highly intelligent features looked out from an old-fashioned poke-bonnet. Mr Thomas regards this photo with peculiar pride, and, indeed, some gush of sentiment may be excused in one who thus believes that his maternal parent was the unconscious originator of his greatest artistic achievement.

___

Black and White (3 February, 1894)

RICHARD BRINSLEY SHERIDAN.

THE romantic elements in the life of the brilliant author of The Rivals and The School for Scandal, have doubtless furnished Mr. Robert Buchanan with more than sufficient material for his new play, which is produced on Saturday next at the Comedy. Indeed, his difficulty was probably that of selecting from the abundance offered by the life and the period with which he was concerned.. Much is strange, much fascinating in Sheridan’s career, and there seems reason to believe that Mr. Buchanan has chosen not the least interesting portion of his hero’s history, viz., the year 1777, when Sheridan was six-and-twenty, and his School for Scandal first saw the footlights. We sincerely hope that Mr. Buchanan will add another leaf to his laurels.

___

Reynolds’s Newspaper (4 February, 1894)

LAST NIGHT’S THEATRICALS.

COMEDY THEATRE.

Last night Mr. J. Comyns Carr produced the much-looked-for comedy by Mr. Robert Buchanan, founded on the love episode of the popular author of the “School for Scandal” and the beautiful singer, Miss Linley. “Dick Sheridan,” as the comedy is entitled, is written in four acts, and the author disclaims any historical accuracy in matters of detail, though he relates with praiseworthy fidelity the elopement of the dramatist with Miss Linley to France, his subsequent marriage, and the motives which prompt the keeping of the marriage secret until he could offer her a fitting home and withdraw her from the public stage. The first act takes place at the Assembly Rooms, Bath, where we find the famous singer beset by the amorous attentions of a senile old beau and the nefarious designs of Captain Matthews, whilst she entertains only a regard for the poor author. Mr. Linley favours the suit of the amorous Lord Dazzleton, and to escape his clutches she accepts the offer of Captain Matthews’ escort to France, but, learning his true character, she decides to allow Dick Sheridan to conduct her to her cousin. The second act, at Sheridan’s lodgings, shows the aspiring dramatist suffering the pangs of poverty, but with his foot on the first rung of the ladder of fame. Here he is persecuted by Matthews, whose creditor he is, who holds over him the punishment of the debtors’ prison if he does not relinquish all pretensions to the hand of Miss Linley. And the subsequent ones are taken up with the clearing of the difficulties which beset the young loving couple. The comedy is, however, not entirely satisfactory. Mr. Buchanan is too much of a master of stagecraft to write a bad play, but in “Dick Sheridan” he is unnecessarily prolix, and some of the scenes could easily be dispensed with. When the excisive process, however, has taken place, there is no reason to doubt the ultimate success of the comedy, which last night was received with enthusiasm. The comedy is brilliantly staged and the dresses are of wonderful beauty, whilst the company could hardly have been better chosen. Mr. H. B. Irving, in the name part, although a trifle nervous, gave an admirable embodiment of the dramatist and politician; and Miss Winifred Emery, as Betty Linley, adds another strong character to her long list of successes. Mr. Brandon Thomas, as the faithful servitor of Sheridan, gives an excellent character sketch, and Mr. Sydney Brough as Sir Harry Chase, Mr. Lewis Waller as Matthews, and Mr. Cyril Maude as the foppish Lord Dazzleton, all give perfect pourtrayals of their respective parts. All the principals were called at the termination of each act, and when the comedy has been dovetailed “Dick Sheridan” will satisfy the expectations of those most interested.

___

The Referee (4 February 1894 - p.3)

COMEDY—SATURDAY NIGHT.

It is not to the biographers of Richard Brinsley Sheridan so much as to the common resources of the dramatist that Mr. Buchanan is indebted for his new play, “Dick Sheridan.” He has taken the story of the romantic courtship and marriage of Elizabeth Linley and Richard Sheridan, and has made of it a play that can only be compared with Mr. Buchanan’s own earlier works of the same kind. This is no occasion to discuss the question to what extent a dramatist is justified in making history to suit his own purpose. Mr. Buchanan specifically states that the play “has no pretensions to historical accuracy,” nor, indeed, are its pretensions to literary distinction more considerable. He might as well have called his hero by any other name. Better so; for imagine a play of which Richard Sheridan is the principal character in which there is not a flash of wit worth remembering! Yet we must admit that Mr. Buchanan jogs gaily along the old ruts, and it is our duty to say that the piece seemed to afford not a little satisfaction to the audience. To what extent this was due to the acting and the costumes, and to what extent to the conduct of the story, we do not pretend to say. It may be that Mr. Buchanan is wise in his generation—that he does not underrate the appreciation of the public. It is no part of the critic’s business, however, to discuss a point which is best left to time to decide. The play opens at Bath, whence Sheridan carries off Miss Linley in the face of his rivals, old and young. The young lady has refused to accept the husband of her father’s choice, and is almost tricked into doubting her true lover’s faith. But when the rascally Captain Matthews, whose escort Miss Linley has agreed to accept, has made his preparations for their departure, he finds the young lady has changed her mind, and she accepts Mr. Sheridan’s hand, whilst the captain is arrested for debt by a doctor of divinity, who has been reduced by circumstances to the office of process-server. That Richard Sheridan had an Irish tutor, Mr. Buchanan acknowledges is his “only warrant for creating the character of O’Leary,” and from this slight fact the author has elaborated the part of Sheridan’s faithful servant and inseparable companion. In the second act we find Sheridan and O’Leary together in humble lodgings in London, and there Dick is visited, one after another, by the gentlemen in whose company he was first seen at the Assembly Rooms at Bath. The humours of this scene are no compensation for the prolixity of the act, which ends with the welcome appearance on the scene of the wife to whom he is secretly married, and who brings him news of the acceptance of his play. Sheridan is only waiting for the success of his play to claim his wife, and the third act brings us to Miss Linley’s boudoir on the evening of the production of “The Rivals” at Covent Garden. Miss Linley is left alone at sunset, when “heaven and earth seem eager for his happiness,” and presently she is joined by Dick, who comes to tell her of the failure of his play, and when the young couple are found together, she reveals the secret of their marriage in an outburst of passion. Upon this the curtain falls again to rise on the last act, in which everything is set straight in the usual formal fashion, ending with a duel in Dick’s room, in which his rival, Matthews, is ultimately and finally humiliated. We are extremely loth to speak harshly, but we cannot find it in our heart to speak in praise of Mr. H. B. Irving, who plays Sheridan. The best that can be said is that it was a mistake to have cast so young and so inexperienced an actor for so important a part. Mr. Irving has neither the practice in acting nor even so much as the grace of deportment to justify the choice. Mr. Irving, to be sure, is at a particular disadvantage in that he appears in a company of far more than ordinarily accomplished actors and actresses. The beautiful Miss Linley is represented by Miss Winifred Emery, who realises in her sympathetic appearance, as well as in her expressive acting, the compliment of the impressionable bishop who is said, according to Tom Moore, to have declared that Miss Linley was “the connecting link between woman and angel.” As the author has dealt more with incident than with character, there is no call for subtlety in the acting. Mr. Cyril Maude, as Lord Dazzleton, who is one of Miss Linley’s most devoted admirers, gives us another performance of an obsolete beau; the dashing, unscrupulous Captain Matthews, another suitor, being represented with ardour by Mr. Lewis Waller. Mr. Brandon Thomas plays the part of Dr. O’Leary for all it is worth, and we can pay the actor no greater compliment than to say that he keeps the audience in a good humour when the author rather tries their patience. As Lady Pamela Stirrup, Miss Lena Ashwell makes yet a further advance in public favour by the refinement and elegance of her performance, in which there is the exact touch of polite comedy. Miss Vane represents a fine lady, jealous of Dick’s admiration for Miss Linley; and auxiliary parts are played by Mr. Sydney Brough, Mr. Edmund Maurice, and Miss Pattie Browne. The author was called before the curtain at the end of the piece.

___

The Times (5 February, 1894 - p.7)

COMEDY THEATRE.

The fundamental incidents of Mr. Robert Buchanan’s new play are simple enough. In the polished and cynical society of Bath in the last century a young singer, familiarly known as “Betty,” wins all hearts. Among her more active admirers are Lord Dazzleton, a battered old beau; Captain Matthews, an army man of shady antecedents; and Dick, a penniless youth who dreams of winning fame and fortune by dramatic authorship. It is Dick whom the fair Betty prefers, and to escape the tyranny of a harsh father, who favours Lord Dazzleton’s suit, she elopes with her lover to France. By-and-by the runaways return husband and wife, but, pending the advent of the fame and fortune dreamt of, Dick settles down alone to work in his garret in London, leaving his young wife free to pursue her musical career. Eventually a play of Dick’s is accepted at Covent Garden. The great David Garrick reads the manuscript and thinks well of it; so does Lord Dazzleton; and both come to congratulate the unknown author in his attic. For the moment the old fop changes his mind on finding in the new dramatist who is said to combine the genius of Congreve and Farquhar a successful rival of his own, but he yields subsequently to Betty’s entreaty and becomes the young man’s most influential patron. Less generous is Captain Matthews, Dick’s other rival. He organizes a cabal against the new play without the knowledge of the author or his friends, who are eagerly counting upon a success. Thanks to these dark machinations the fond hopes of Dick and his beloved Betty, who visits him in secret, are temporarily dashed to the ground. Captain Matthews’s scheme proves only too successful. The news is brought that the play has failed on its first performance. In his dejection Dick renounces authorship altogether, and fights a duel in his garret with Matthews, who has come to taunt him with his misfortune, and who is disarmed and humiliated for his pains. The young man’s success with his rapier is only a preliminary to that gained by his pen. On the second night, we learn, the new comedy goes like wildfire, and the curtain falls upon the happy reunion of Dick and his bride. Considering how commonplace is this story as a story, how much inferior in dramatic grip to the avowed efforts of imagination of which Mr. Robert Buchanan has shown himself capable, it seems scarcely worth while to label its chief characters Miss Linley and Richard Brinsley Sheridan and to put it forward as an account of the first production of The Rivals. This, however, Mr. Robert Buchanan has done in Dick Sheridan. Not that he professes to be biographical! He expressly declares that his “new and original comedy” has “no pretensions to historical accuracy in matters of detail,” and, in truth, the production of the first work of any dramatist, say, of Mr. Buchanan himself, might be trusted to furnish incidents as moving as those here set forth. Nevertheless, biographical or not, he has tied himself down to a certain prosaic order of events which cannot be regarded as altogether effective from the stage point of view.

In every well-made play there is a question of some kind placed before the house—an issue upon which the interest of the spectator hangs. What is the issue in the present case? The union of the oppressed lovers? Hardly so, for they are secretly married before the curtain rises on the second act. The event in which the spectator is expected to interest himself is mainly the fate of a piece called The Rivals, written by a young man named Sheridan. No doubt the issue of a story may be immaterial, provided the author gives a life-like representation of character, couched in more or less brilliant dialogue. But in this case Mr. Buchanan has the air of having sacrificed everything to his story, after the manner of the writer of melodrama. At faithful characterization certainly little or no attempt is made. With ordinary names substituted for those of Sheridan and Miss Linley, the play would proceed exactly as before; while in the matter of dialogue there is an almost studied avoidance of literary sparkle. Mr. Buchanan, in fact, has a strange fondness for juggling with names which have nothing behind them. Mr. H. B. Irving, who, it was announced some time ago, had given up the stage for law, but who would seem to have since changed his mind, is possessed of physical qualities which fairly well consort with one’s notions of Sheridan as a young man; but the title part, for which he has been cast, affords him no opportunity of depicting the character from the intellectual side. It is true Dick is discovered writing a scene of The School for Scandal, which he afterwards throws into the fire, whence it is rescued by a faithful Irish man-servant; true also that he is hailed by his intimates as the great wit of the age. But assuredly he furnishes in his own person no indication of surpassing genius. The author has not even created him in his own image, since wittier, if not wiser, things than are set down for this literary prodigy have constantly proceeded from Mr. Buchanan’s pen. Another example of Mr. Buchanan’s use of an illustrious name as a mere husk, so to speak, is the introduction of “David Garrick” in a scene where any ordinary walking gentleman would do sufficiently well, and where, indeed, an actor named Mr. Will Dennis acquits himself very creditably, the great man having only a few commonplaces to say, though, to do him justice, he looks greatness unutterable.

To what extent this trafficking in names may help the author’s dramatic scheme it is difficult to judge. Some influence it may indeed exercise in his favour, since there will probably be little disposition on the part of the public to condemn the undramatic turn of a story which is understood to be trammelled by historical fact. The one obvious remark invited by the play is that, as an exposition of Sheridan the wit, the dramatist, the man of the world, it is valueless. It is really a love story of no particular merit, placed in a period which Mr. Buchanan’s literary instinct enables him to handle somewhat more deftly than the journeyman dramatist. The opening scene of the play, the Assembly-rooms at Bath, with its coming and going of fops and coquettes, is perhaps the happiest in a literary sense, as it is certainly the most picturesque. Here we make acquaintance, not only with Sheridan and Miss Linley, but with characteristic types of the period—a heartless, backbiting, slanderous, polished, overdressed set, of whom Mr. Cyril Maude as a grotesque old beau, Mr. Lewis Waller as the sinister captain, Mr. Sydney Brough as a man about town, Miss Vane and Miss Lena Ashwell as ladies of quality, are the more conspicuous members. The faithful Irish servant O’Leary, a “scholar and a jintleman,” is played with rare tact and feeling by Mr. Brandon Thomas. In Miss Winifred Emery Miss Linley finds a graceful and sympathetic representative. To Mr. H. B. Irving’s Sheridan reference has already been made. It is a performance which is pleasing at least to the eye, though necessarily marred by occasional crudities of style due to the actor’s inexperience. There only remains to add that the piece was rapturously—perhaps a little too rapturously—applauded by a large section of the house.

___

The Pall Mall Gazette (5 February, 1894)

THE THEATRE.

_____

“DICK SHERIDAN” AT THE COMEDY THEATRE.

In choosing the life of Sheridan, or rather a portion of the life of Sheridan, for the subject of a play, Mr. Buchanan had one great advantage to aid and one great disadvantage to impede him. It is always something of an advantage for a dramatist to choose a famous hero—a man, the mere echo of whose name awakens echoes in the mind and paints pictures on the imagination of everybody. Who so poor in knowledge as not to have heard of Sheridan, as not to associate his name with wit and genius, and fame and love and folly, as not be prompt to welcome his presence in the playhouse as the presence of a familiar friend? Here is the dramatist’s advantage. He is at once, before the curtain rises, in so much sympathy with all his audience. A portion of their affection is already enlisted in his favour. The spell of association is at work upon them, and their interest is half secured, their approval half won before a word has been spoken or a thing done to deserve either. But the advantage brings with it a more than proportionate disadvantage. The better the hero is known, the more directly he appeals to the hearts and brains of the spectators, the more difficult is it for the dramatist to realize the image of the man as he quickens in the fancy of the public, as he bulks in the records of his country’s history.

It might have been better for Mr. Buchanan’s play if he had foregone the advantage of trying to make Sheridan live again. Mr. Buchanan has no very great esteem for the making of stage plays. He regards it as a business to be learned like any other business, and he asserts, with truth, that he has learnt much of the business, and is not without skill in it. But on Saturday night his skill seemed to be rather hampered than helped by his subject. He did not appear to have made up his mind as to what it was exactly that he wanted to do. On the one hand he seems to have desired to make the early life of Sheridan the subject of a piece that should reflect, with some degree of fidelity, the manners, the customs, and the men and women of the epoch of Sheridan’s youth. On the other hand, he seems to have been moved by the wish to write a modish comedy in the manner of the predecessors of Sheridan, and to imitate the fantasies of Congreve and of Farquhar, of Wycherley and of Vanbrugh, by introducing whimsically-named figures, unreal in themselves as the creatures of an Arabian tale, but typical, or intended to be typical, according to the artificial method, of a class. And the play suffered from this conflict of the historical and the fictitious, of the real and the artificial.

It is possible that Mr. Buchanan was not really influenced by either of the two conflicting purposes that seem to dismember his comedy. His purpose may have been neither more nor less than to write as interesting a play as he could, and to make use of any method, of any artifice, that would serve his turn. But the play would have gained in interest either way, if Mr. Buchanan had chosen to follow either of the two distinct courses which, apparently, he endeavoured to combine. A series of episodes from the life of Sheridan, handled with fidelity, might very well have had enough charm in themselves to please, with the addition of very little extraneous matter. On the other hand, a carefully constructed, melodramatic, gallantly imaginative piece of play-making, using the name of Sheridan merely as watch-word, might have done well. But the impression produced by “Dick Sheridan” is that the author tried both methods independently and then sought to weld the two into one, with a result less satisfactory than might have been attained by adhering to either purpose by itself. Mr. Buchanan’s Sheridan is neither an historical portrait, nor is he a hero of romance. He is the least attractive, the least realized of all the figures in the comedy. He is a languorous, spiritless, unenterprising fellow. Even his elopement is only a tame acceptance of the suggestion of Matthews—who is far more boldly and ably drawn—and his successful exit at the end of the first act—an effective and ingenious situation—is due not to him but to the readiness of his henchman. It is hard to believe in so limp a creature producing “The Rivals,” and drafting “The School for Scandal” in its first form, or even having the animal spirits to rally a Jew money lender who has staggered into the play from the pages of Congreve, not to its advantage. It is only in the last act, when he fights the famous duel—or rather, one of the famous duels—that he at all rises to the dignity of the situation and the honour of his name. And even as he does, one is reminded of Miss Stewart’s remark about Raoul de Bragelonne, “Enfin il a fait quelquechose; c’est, ma foi! bien heureux.”

It is still no doubt in Mr. Buchanan’s power to amend his play, and it is quite worth taking some pains to amend. It is, on the whole, admirably acted. Inevitable curiosity, and the prominence of his part, make the acting of Mr. H. B. Irving stand first in order of consideration. Mr. Irving’s stage career has been, so far, a short one, but neither unsuccessful nor undeserving of success. His performance in “School” counted for little or nothing; his performance in “A Fool’s Paradise” counted for a good deal. His performance on Saturday night may be commended, and even, under qualification, warmly commended. The young actor was obviously and naturally nervous. He fought against his nervousness with great courage, and in the end conquered it, or seemed to conquer it, completely. While making every allowance for this nervousness it needs no generosity to discern that he has many gifts which if wisely used and discreetly governed may carry him far. No more than this, but certainly no less than this, was to be learned from his creation of Richard Sheridan. It was a pity that Mr. Comyns Carr made a well-meant error in saying what he did say before the curtain about the young actor. It is not, or at least it should not be, any part of a manager’s business to praise his own players to his public. And young Mr. Irving had done quite well enough to need no such adventitious assistance. Miss Winifred Emery presented a whole gallery of exquisitely lovely pictures of Elizabeth Linley. Mr. Lewis Waller gave a grim and powerful character study of Captain Matthews, and his fury, despair and shame in the last act were represented with a tragic force and passion. Mr. Brandon Thomas played the grotesque Irish tutor, the new Partridge with which Mr. Buchanan has endowed his Sheridan, with a restrained humour that was exceedingly effective. Mr. Sydney Brough had only to look and act like a last century gentleman, but that is not always easy to do, and he did it admirably. The artistic triumph of the evening, however, was the Lord Dazzleton of Mr. Cyril Maude. Mr. Maude has the rare secret of giving individualism and distinction to his studies in old age, and his foppish, wizened, apish, not unkindly Mæcenas proved in the end a masterpiece. In the beginning there was a tendency to exaggeration, which Mr. Maude might combat with advantage. Lord Dazzleton was a droll, but he was also a gentleman, and would have scarcely indulged in so much skipsomeness in the Assembly Rooms at Bath.

___

The Echo (5 February, 1894 - p.2)

COMEDY THEATRE.

_____

EPISODES FROM THE LIFE OF SHERIDAN.

Twice within the month has Mr. Robert Buchanan heard the pleasant music of a usually smart West-end audience calling him before the curtain to bow for a first-night success. Wise in his generation he allowed his four acts of dramatised selections from the biographic records of the author of The School for Scandal, which he has called Dick Sheridan, to speak for themselves. He merely beamed at our enthusiastic reception, and was silent. Less discreet was the manager, Mr. Comyns-Carr, who, though famed in theatrical circles for his tactfulness, was nevertheless betrayed by the excitement of the moment into singularly undiplomatic remarks about the youngest member of his company, Mr. H. B. Irving, who, though showing traces of inheriting the gifts of his illustrious father has much to learn before his merits claim effusive recognition from his managers. But, may be, Mr. Carr did the drama better service than he wots of. Those who cry “Speech, speech,” on such occasions most selfishly place actors and managers in a dilemma from which there is no artistic escape, and Mr. Carr’s experience will strengthen the hands of the latter gentlemen in refusal. In every line of Dick Sheridan we are made to feel the skill and address of its compiler’s hand. It teems with effectively-planned situations, with cheer-provoking sentiments, and with opportunities for histrionic display. On the other hand, it seems to lack purpose, conviction, and a sense of dramatic unity, whilst very little attempt is made at the development of character. Mr. Buchanan appears to have said to himself “Let us study the life of Richard Brinsley Sheridan; let us see what scenes of it can be adapted to the stage,” rather than to have been inspired with a dramatic idea and have selected the peerless comedy-writer as the means of giving it expression. The result has proved most interesting. We have a most picturesque and matchlessly staged and dressed sequence of pictures of the life and society of Bath and London in the closing years of the eighteenth century, which fill the eye and occupy the mind. To the great fault of the society he has selected for illustration the author has been faithful. It displayed a good deal more sentiment than feeling, and muffled its thoughts in pompous phrase. Unfortunately, these weaknesses are not dramatic. Mr. Buchanan’s historic fidelity has operated greatly against his gaining a grip on his audience and his dramatic directness. The episodes utilised are

THE WOOING AND WINNING

by Sheridan of the beautiful Miss “Betty” Linley, a sweet singer and the daughter of the concert-master of modish Bath; her flight into France and secret marriage; the first unfortunate production of The Rivals; the play’s subsequent triumph, and the victory of Sheridan the dramatist over all traducers, slanderers, and conspirators, which placed him in a position to openly claim and support his lovely wife. The first act shows us Sheridan at Bath, outwitting rival suitors, an elderly macarroni lord and art patron, one Lord Dazzleton, and a rascally libertine, one Captain Matthews, and carrying off Betty by means of the very machinery his foes invented for their own ends. The second act turns the light on Sheridan in his garret, attended, it would seem, by an own brother to Tom Jones, poor Partridge in Sophia, waiting for the commission which does not come, and eating his heart out till he should be enabled to acknowledge his bride. It is rendered unduly lengthy by an elaborately led-up-to practical joke perpetrated at the expense of a Jew money-lender, an incident the author tells us he borrowed from a comedy of Congreve, and might certainly instantly return with profit to his own. Garrick, in suâ propriâ personâ, in this scene appears on the boards. His appearance is dramatically superfluous, but it certainly gives point to the picture of the hour. The third act show us young Mrs. Sheridan at home in the house of her father, her secret unsuspected, persecuted by the attentions of her swains, and messengers from Covent-garden apprize us how The Rivals is being murdered. The last act is quickened by a very ably designed duel between the villain of the comedy, Captain Matthews, and Sheridan. But all ends exactly in the manner Dr. Pangloss would have prophesied.

The play was very powerfully cast. Such sound comedians as Mr. Brandon Thomas, Mr. Edmund Maurice, Miss Vane, and Mr. Sydney Brough in comparatively minor parts were sure to make themselves felt. A young actress, Miss Lena Ashwell, dashed in a sketch of a horsey young lady of 1772 with great spirit; and Mr. Will Dennis’s “exit” as the great Garrick was high comedy. The finest passage of the whole evening was the impassioned acting of Mr. Lewis Waller in the duel scene, when, maddened by taunts, he whips out his rapier and attacks his rival, though under conditions very distinctly unfair to him. The audience held its breath, spell-bound for the moment by this vivid flash of realistic intensity. Miss Pattie Brown’s little waiting-maid was winning as she was coquetish; and Mr. Cyril Maude as the affected and mannered old beau of the period, was perfectly at home. That so inexperienced an actor as Mr. Irving could do what he did with so important a part as that of Dick Sheridan speaks volumes for his future, He was frank, very pleasant to look upon and to listen to, and manly; nor was he deficient in touches of romance and emotion, but his want of practice was outpaced by the art and knowledge of his supporters. Miss Winifred Emery, in her beautiful robes of turquoise silk, was a picture of which to go home and dream, and not to vulgarise by attempted descriptions; and her Betty was distinguished by all that womanly grace and tenderness and emotional power when occasion demanded which has won her her high place amongst the queens of our stage. But just the hint of a suggestion to her—is she not in danger of allowing her trick of conveying passion by stamping one foot—most artistic at times—to develop into something colourably like a mannerism?

___

St. James’s Gazette (5 February, 1894 - p.12)

COMEDY THEATRE.

“DICK SHERIDAN.”

BY his second production at the Comedy Theatre Mr. Comyns Carr fully establishes his position as one of the most artistic and liberal of our London managers. Spectacularly “Dick Sheridan” leaves nothing to be desired. On every side the proofs of a lavish hand and a keen eye for pictorial effect are to be discerned. A sumptuous taste pervades the entire piece, and stamps it with a consistent air of elegance and refinement. Fortunately the period of the play lends itself admirably to such treatment. An age of gallantry has been dealt with in a gallant fashion. It is true the costumes, in their richness, their brilliant colouring, and their mode, recall the epoch of the Third rather than of the Fourth George; but this is a slight matter compared with the gain secured in the beauty and the splendour of the mounting. The first act of “Dick Sheridan” passes in the Assembly Rooms at Bath, and affords occasion for an exquisite display. There is the picturesque figure of Sheridan himself, the quaint personality of the elderly beau Lord Dazzleton, the radiant loveliness of Elizabeth Linley, and the lively grace of dainty Lady Pamela Stirrup. To these a fitting contrast is furnished by the threatening visage of Captain Matthews and the sombre habit of Dr. Jonathan O’Leary. Historical characters flit across the scene—Lady Miller, known as the Queen of Bath, whose hand, as Horace Walpole relates, it was the privilege of the winner at the Olympic Games to kiss; Captain Wade, the Master of the Ceremonies; and Mr. Linley, the well-known composer and father of the heroine. Appropriately enough, in such a scene of beauty, opportunity is found for the introduction of a stately dance, executed by the full strength of the company and forming one of the most striking and attractive features of the piece. Distinguished by equal taste are the subsequent “sets” showing Dick’s lodgings in London and the interior of Miss Linley’s boudoir. But, in truth, so harmonious and pleasing are all the details that one is tempted to linger over them somewhat to the prejudice of other considerations. Still an expression of gratitude is distinctly due to Mr. Carr for the exquisite series of pictures he has provided, to Mr. Walter Hann for his admirable scenery, and to “Karl” and Mrs. Comyns Carr for the skill they have displayed in the designing of the costumes.

THE AUTHOR OF “THE SCHOOL FOR SCANDAL.”

“I had my own idea of Sheridan—a black-visaged, saturnine creature, a W. S. Gilbert of his day, if you like. And I returned to my own idea of Sheridan, abandoning the attempt to paint him as the prototype of H. J. Byron, who was witty, and spontaneously witty. I have taken the Sheridan love-story and adapted it to my needs. But no ‘Sheridan’s Bon Mots.’” Thus Mr. Robert Buchanan in a recent interview. Saturday night’s performance abundantly proves that Mr. Buchanan is a man of his word. Conscientiously and laboriously he has resisted the temptation to introduce into his new play even the suggestion of the least of “Sheridan’s Bon Mots.” One can realize what the effort must have cost him—how again and again, while sitting over his desk, he has, with the courage of a Roman father, stifled the scintillating jest or the brilliant sally born of his vivid imagination. Mr. Buchanan evidently is too much of an artist to permit any inclination to split the ears of the groundlings to interfere with his conception of a character. In his opinion the author of “The Rivals” and of “The School for Scandal” was indubitably a dull dog; and a portentously dull dog he has made of him in his new play, which, with subtle humour, he dubs a comedy. Frankly, we cannot but admire Mr. Buchanan’s courage. It would have been so easy to convert his hero into a wit—to have sprinkled the part with false epigrams and showy paradoxes of a pattern similar to those which have earned for Sheridan, undeservedly it appears, the admiration and the praise of four successive generations. But no, says Mr. Buchanan. “I purchased a book called ‘Sheridan’s Bon Mots.’ It gave me the worst quarter of an hour I ever had in my life.” Here, it is just possible, there may be some confusion of cause with effect; for has not another writer of plays declared that “a jest’s prosperity lies in the ear of him that hears it, never in the tongue of him that makes it”?

THE PIECE.

Sheridan, however, according to his latest biographer, was not only not a wit, but a rank sentimentalist. It is as such that he moves through the new piece, the action of which follows sufficiently closely the early career of the ambitious young author. His passion for the beautiful Miss Linley, her love for him; the intrigues set on foot by Captain Matthews to separate the two; their flight to France and subsequent marriage; the failure of “The Rivals” on its first performance, and the immediate reversal of the original verdict on the second representation of the play; the duel between Matthews and Sheridan, regarding which such different testimony exists; and the final reunion of the youthful husband and wife, furnish ample material for a thrilling piece. Mr. Buchanan’s recent experience at the Adelphi would appear to have prompted him to regard things from a somewhat melodramatic standpoint, and it is in this spirit he has approached “Dick Sheridan.” In it the building up of effective situations is considered of greater importance than development of character; the broad brush of the scene-painter replaces that of the more delicate artist. Yet withal there is matter in “Dick Sheridan” to hold the attention and to stir the pulse to a quicker throb. Practically, however, the real interest of the story does not begin until the third act, and, accordingly, the more closely the first two can be compressed the greater will be the chances of success. Let it be further said, that on Saturday night a crowded house received the comedy with manifest favour, although occasionally a slight feeling of opposition was aroused by certain of the incidents—notably that at the commencement of the second act, in which the Jew Abednego figures. If also a little more lightness and brilliancy could, even at the expense of truth, be introduced into the dialogue, it is probable the audience would consent to regard the circumstance in a conciliatory spirit, and agree to overlook the impropriety of an innovation calculated to increase the sum of its hilarity.

THE PERFORMANCE.

Upon the part of Elizabeth Linley Miss Winifred Emery brought all her well-known charm and nervous force to bear. The rôle, perhaps, offers her no opportunity of equal greatness with that furnished in the third act of “Sowing the Wind;” but it is rich in pathos, tenderness, and grace. With all these qualities Miss Emery is liberally endowed, and at no moment did she fail to strike the right note. Of the ladies, next in importance comes Miss Lena Ashwell, whose delightfully fresh and natural performance as Lady Pamela marks another forward step in the career of this rising young actress. Mrs. Lappet. Miss Linley’s maid, found an arch and roguish representative in Miss Pattie Browne; while Miss Vane gave an adequate portrait of “The Queen of Bath.” Among the male performers the chief honours, having regard to the quality of the part, must be assigned to Mr. Lewis Waller, who by his firmness, decision, and quiet strength, as Captain Matthews, proved of invaluable service to the success of the play. Mr. Cyril Maude’s assumption of Lord Dazzleton again revealed the same careful study and polished style characteristic of all this actor’s work; and Mr. Brandon Thomas at once ingratiated himself with the audience as the warm-hearted Irish servitor, Jonathan O’Leary. In smaller parts, Mr. Sydney Brough, Mr. E. Maurice, and Mr. Will Dennis, the last especially good, rendered excellent service. Mr. H. B. Irving appeared in the title-rôle. Of his performance it is unfortunately impossible to speak in terms of unqualified praise. Mr. Irving has had the ill luck to be placed in a position for which neither his experience nor his ability qualifies him as yet. The part of Sheridan is a long and arduous one, which would tax all the resources of a skilled and tried performer. To say that in its representation Mr. Irving showed more than promise would be an act of mistaken kindness. Mr. Irving has still to win his spurs. He has plenty of time before him, however, and with perseverance and courage there is no reason why he should not yet achieve fame and distinction in the profession he has selected.

___

The Daily Telegraph (5 February, 1894 - p.3)

“DICK SHERIDAN” AT THE COMEDY THEATRE.