|

Play List: 4. Corinne 7. The Mormons 9. Lucy Brandon 10. Storm-Beaten 11. Lady Clare 13. Bachelors 14. Constance 15. Lottie 16. Agnes 17. Alone in London 18. Sophia 19. Fascination 20. The Blue Bells of Scotland 21. Partners 24. Angelina! 25. The Old Home 26. A Man’s Shadow 27. Theodora 29. Clarissa 30. Miss Tomboy 32. Sweet Nancy 33. The English Rose 36. Marmion 37. The Gifted Lady 38. The Trumpet Call 39. Squire Kate 40. The White Rose 42. The Black Domino 44. The Charlatan 45. Dick Sheridan 47. Lady Gladys 48. The Strange Adventures of Miss Brown 49. The Romance of the Shopwalker 52. Two Little Maids from School ___ |

|

ROBERT WILLIAMS BUCHANAN (1841 - 1901) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

THEATRE REVIEWS 49. The Romance of the Shopwalker (1896)

The Romance of the Shopwalker David Christie Murray (the elder brother of Henry Murray) accused Buchanan of plagiarising his novel, The Way of the World, and there was some correspondence on the matter in The Era. The original inspiration for both Murray’s novel and Buchanan and Jay’s play was Samuel Warren’s novel, Ten Thousand a-Year.

The Glasgow Herald (6 January, 1896 - p.4) It is not unlikely that a new comedy by Mr Robert Buchanan may soon be produced at the Vaudeville, where the run of “The New Boy” comes to an end next Saturday. Meanwhile the house will be closed for a few weeks until Mrs Weedon Grossmith (Miss May Palfrey) attains convalescence. ___

The Glasgow Herald (10 January, 1896) OUR LONDON CORRESPONDENCE. 65 FLEET STREET, . . . I UNDERSTAND that two pieces, both by Mr Robert Buchanan, are before Mr Weedon Grossmith, and that one of them will be the next production at the Vaudeville. The comedies are respectively entitled “Good Old Times” and “The Shop Walker.” They are said to be the survivors of nearly 800 plays by various stage aspirants which this unfortunate manager has had to peruse. ___

The Era (11 January, 1896) ROBERT BUCHANAN’S PLAYS. TO THE EDITOR OF THE ERA. Sir,—It is an old adage which says that the world knows more of one’s private business than one does oneself, and the truth is illustrated daily by the extraordinary statements of the theatrical gossip-monger. I see it stated in print to-day that Mr Weedon Grossmith will shortly produce one of two plays, the names of which are incorrectly given, “by Mr Buchanan.” May I ask you to state that, up to the time of writing, I have made no arrangement with Mr Grossmith to produce any work whatever, and that, in any case, I am only the part-author of any work which he may have had under consideration. I strongly object to have my business arrangements anticipated by the writers of newspaper paragraphs, and I also strongly object to have my unborn plays christened for me at the font of the Printer’s Devil. ___

The Era (25 January, 1896 - p.12) IT is now, we believe, pretty certain that when the Vaudeville reopens the production will be that of a play in which “Charles Marlowe” has again collaborated with Mr Robert Buchanan. ___

The Era (1 February, 1896 - p.12) THIS announcement effectually disposes of the rumour that The Gay Parisienne would be Mr Weedon Grossmith’s next production at the Vaudeville, where, indeed, our announcement of last week is by way of being verified. Mr Robert Buchanan’s piece has been cast, and is in rehearsal. Miss Palfrey, Miss M. A. Victor, and Miss Annie Hill will be found in the reorganised Vaudeville company. ___

The Derby Daily Telegraph (4 February, 1896 - p.4) The new comedy by Mr. Robert Buchanan and “Charles Marlowe” (the pseudonym, it is believed, of a lady), authors of “The Strange Adventures of Miss Brown,” is preparing at the Vaudeville. It is to be called “The Romance of the Sleep-walker.” The cast will include Mr. Weedon Grossmith, Miss May Palfrey, Miss M. A. Victor, Miss Nina Boucicault, Mrs. Elwood, and Mr. David James, jun. ___

The Stage (6 February, 1896 - p.11) When I announced that either The Shop Walker or Good Old Times, both by Robert Buchanan, would be the next production at the Vaudeville, the dramatist, with Charles Reade-like vigour, laboured me with abuse – in another paper. Now, however, it appears that The Shopwalker, re-christened The Romance of a Shopwalker, is to be produced on or about Thursday, the 20th inst. The piece is described as a three-act comedy-drama, and the Shopwalker with a romance will be played by Mr. Weedon Grossmith. Others in the cast are: Messrs. Sydney Warden, David James, who is entrusted with a Scotch part (in which he should make a hit), Misses Annie Hill, Nina Boucicault, Talbot, M. A. Victor, and Mrs. Weedon Grossmith (Miss May Palfrey), who will make her welcome reappearance as the heroine. _____ The Romance of a Shopwalker has been written by Robert Buchanan and “Charles Marlowe,” the latter nom de guerre standing, I think, for clever Miss Harriett Jay. ___

The Illustrated Sporting and Dramatic News (8 February, 1896 - p.18) The Romance of the Shopwalker is the title of the three act comedy by Mr. Robert Buchanan and Mr. (or is it Miss?) Charles Marlow, promised shortly at the Vaudeville under its present management. The “romance,” as may be imagined, is of a somewhat farcical description, for though there is no reason to suppose that a counter-jumper may not be just as sentimental as any of his customers, it is difficult to get up much emotion over a Tittlebat Titmouse. What a Titmouse, by the way, Mr. Weedon Grossmith would make! Of course he is to be the hero of this new study of various class contrasts, while he will have as associates in the cast Miss May Palfrey and Miss M. A. Victor, both happily recovered from their recent illnesses, Miss Nina Boucicault, Mr. Elwood, and Mr. David James. Long may the little shopwalker go his rounds, and excellent may be his business! ___

The Derby Daily Telegraph (10 February, 1896 - p.3) Mr. Weedon Grossmith will soon re-open the Vaudeville Theatre with a farce to be called “The Romance of the Shop-walker,” and it is believed that Mr. Robert Buchanan and his literary companion, “Charles Marlow,” have provided the droll little actor-manager with a highly-diverting character. ___

Pall Mall Gazette (12 February, 1896 - p.1) THEATRICAL NOTES. Mr. Weedon Grossmith has arranged to produce “The Romance of the Shopwalker,” the new domestic comedy Messrs. Robert Buchanan and Marlowe have written for him, on Thursday, the 27th inst. In this piece Mr. Grossmith will succeed in getting away from the rôle of the meek little man with a commanding wife—a rôle to which he seemed condemned for all eternity. The piece has a strong dramatic interest, as well as humour, and with the strong company engaged will, it is hoped and expected, attain the success every one would like to see associated with the names of Mr. Grossmith and Mr. Buchanan. |

|

|

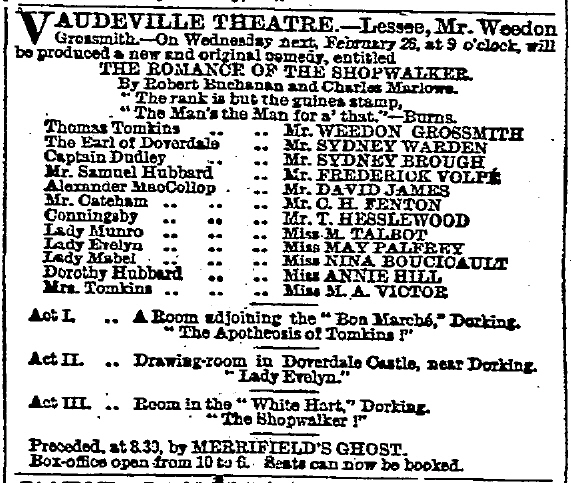

[Advert for The Romance of the Shopwalker from The Times (24 February, 1896).]

The Times (27 February, 1896 - p.10) VAUDEVILLE THEATRE. The story of a sudden accession of wealth has been employed in many forms by novelists and dramatists of many calibres, from the author of Money downwards, and Mr. Robert Buchanan and his collaborator “Charles Marlowe” (who, when these authors were called last night, proved to be Miss Harriett Jay) have not done amiss in returning to it in The Shopwalker. The time has certainly come when the once familiar story may be told again. It is to be regretted that the authors of The Shopwalker should not have told it better; but there is in this piece, nevertheless, a considerable proportion of the elements that appeal to popular taste. The personage selected for the subject of the experiment of a sudden elevation to wealth is a draper’s assistant, one Thomas Tomkins, who provides Mr. Weedon Grossmith with excellent material for a character sketch, somewhat overdrawn of course, but only the more amusing for that. Tomkins inherits £20,000 a year. In his shop he has ventured, un ver de terre amoureux d’une étoile, to fall in love with a young lady of title who occasionally does business with his firm. This is no other than Lady Evelyn, daughter of the Earl of Doverdale—a part played with the necessary distinction by Miss May Palfrey. For the time being Tomkins’s passion is hopeless, but the death of a wealthy uncle, who leaves him all his property, places him theoretically on a level with the highest in the land. Unfortunately, with all his wealth Tomkins remains a cad of the purest (if not the dirtiest) water, and his suit obtains only the most superficial success. The Lady Evelyn’s affections are placed elsewhere. So, for the matter of that, are Tomkins’s; for in the end the little draper wisely renounces his claims to the hand of the aristocrat and returns to a humble sweetheart with whom he had “kept company” in his shopwalking days. But this is not accomplished until he has had the mortification of being defeated as a candidate for the Parliamentary representation of a local borough. The rough humours of the election fill out the third and last act, but they are not of an exhilarating nature, and they rather accentuate the tendency of the story to drag. It is a pity that the character of the enriched shopwalker should not per se be more interesting than it is; for Mr. Weedon Grossmith elaborates it with infinite care. The authors, however, feel the necessity of developing the sympathetic side of Tomkins’s nature; and accordingly, after renouncing Lady Evelyn’s hand, the little draper makes her a present of her ancestral property which has become his under a mortgage. Miss May Palfrey, Mr. Sydney Warde, Mr. Sydney Brough, and Miss Nina Boucicault sustain with spirit and distinction the aristocratic personnel of the piece; and a strikingly correct study of a Scotch character is given by Mr. David James, as the exalted draper’s man of business, Sandy M’Collop. Miss Annie Hill plays the humble sweetheart with becoming naiveté. The reception of the piece was favourable. ___

The Guardian (27 February, 1896 - p.5) Mr. Robert Buchanan and “Charles Marlow”—who now stands revealed in the person of Miss Harriet Jay—have written for Mr. Weedon Grossmith an old-fashioned but pleasant and entertaining comedy, produced at the Vaudeville this evening under the title of “The Romance of the Shop-Walker.” It may be briefly described as Samuel Warren’s “Ten Thousand a Year” with a sympathetic instead of an unsympathetic Tittlebat Titmouse. Mr. Weedon Grossmith plays the millionaire shopwalker with a great deal of humour and, at the close, not without a touch of pathos. Miss May Palfrey is pleasant as the haughty damsel who is on the point of marrying him because his villanous has led her to believe that if she does not he will ruin her impecunious father, and Mr. David James is excellent as the said villanous henchman. Other parts are played by Mr. Sydney Brough, Miss Nina Boucicault, Miss Annie Hill, and Miss M. A. Victor. The play was much applauded, and the call for the authors was unanimous. ___

The Daily News (27 February, 1896) DRAMA. VAUDEVILLE THEATRE. To give only the outline of the plot of “The Romance of a Shopwalker” would be to bring to the mind of the playgoer many familiar scenes. But it is not so much the story as the manner in which it is told that makes the story as the manner in which it is told that makes the fortunes of a piece. In the latest work of Messrs. Robert Buchanan and “Charles Marlowe” we meet many old friends. There is, to begin with, the young man of humble origin, who has come in for a fortune, and means to make an aristocratic marriage. He is received into the house of a nobleman, who has nothing left to boast of but his family pride. Then there is the haughty earl’s daughter, who rejects the suitor of her choice in order to relieve her father of his financial embarrassments by marrying the uncouth young man, who has secured a mortgage upon her father’s estate. It is in the incidental humours of the piece that the authors have imparted a certain freshness to this romantic story, though the intrigue is conducted in the old-fashioned style, scenes of broad farce alternating with passages of sentiment. The central figure of the play is Thomas Tomkins, a young man who appears to have been born before the era of the School Board. Tomkins is a shopwalker, with a soul above drapery, and a mother in whom the spirit of Mrs. Brown—a type of character of a bygone generation—is revived. Tomkins has fallen desperately in love with the Lady Evelyn Munro, and her appearance in his employer’s shop gives Mr. Weedon Grossmith, who has the chief part, the opportunity for the comic expression of his devotion. His servile adoration of the young lady, his amorous glances, his efforts to suppress his emotion, all this is extremely funny; and Mr. Grossmith is better served by the authors than any other member of the company. With the news that the shopwalker has inherited an enormous fortune the first act closes, and in the second Tomkins, who has invested as much of his wealth as possible upon his personal appearance, is a guest in the Earl of Doverdale’s house, where he is the only person who seems to be at ease. Tomkins is now going into Parliament, and has adopted the Conservative opinions of his host. He leaves that business, however, to his agent—“he knows my political opinions,” as Tomkins says, “so much better than I do”—whilst he attends to his love affairs, in which he is also prompted by his rascally agent, who tells him that the Lady Evelyn returns his affection. Upon this hint Tomkins speaks and in a very funny scene he declares his passion, on his knees. The third act passes to the day of the poll, and Tomkins, who is nervous enough in addressing the electors from the window of the White Hart, plucks up courage when personal references to his mother are introduced, and boldly gives them what he would call a piece of his mind. For Tomkins is not such a paltry creature as he seems, and when he discovers that the Lady Evelyn prefers his first cousin to him, he generously brings the lovers together, and presents the young lady with the mortgage deeds as a wedding present. Then the insignificant little man, who has been the object of everybody’s scorn but his demonstrative mother’s, becomes the admiration of them all, and the newly-elected member of Parliament offers her hand to the shopkeeper’s daughter, who has had all along a forlorn hope of becoming his wife. The romantic sentiment of the piece, it will be seen, is somewhat strained, and the fun lies rather in the ludicrous contrasts of the pushing Tomkins with his surroundings than in the wit of the dialogue, which is not particularly brilliant. Next to Mr. Grossmith, Miss Nina Boucicault contributes the best piece of acting, and it is to be regretted that this vivacious actress is no better employed than in playing the auxiliary part of the younger sister of the Lady Evelyn, who is prettily represented by Miss May Palfrey. Mr. Sydney Brough is the over-bearing young lover, whose insolence cannot be so easily forgiven by the audience as it is by the young lady and the too magnanimous shop-walker. Mr. Sydney Warden plays the Earl of Doverdale, who expresses himself in the stilted style which noblemen commonly use only in books and plays, and talks of “retiring to rest,” when an ordinary mortal would say he was going to bed. A very amusing sketch of an election agent is given by Mr. David James, and Miss M. A. Victor has the part of the expansive mother. At the end of the performance the authors were called, and the mystery of the identity of “Charles Marlowe” was revealed by the appearance of Miss Harriett Jay with Mr. Buchanan. ___

Pall Mall Gazette (27 February, 1896 - p.2) “THE SHOPWALKER.” The words “The Romance of” precede the above title on the programmes of the Vaudeville Theatre, where Mr. Weedon Grossmith produced his new and original comedy, in three acts, by Robert Buchanan and Charles Marlowe, last evening. There is not too much “romance” about the “new” play, except of an antediluvian order. The piece is thoroughly “conventional.” The authors have chosen a quotation from Burns as their text, which runs— The rank is but the guinea stamp, As a matter of fact, we opine that perhaps a more appropriate quotation would have been “Tittlebat Titmouse is my name.” Mr. Robert Buchanan is rather fond of seeking and finding inspiration for his “new and original comedies” in old- time novelists’ suggestions. In the present instance the source can be traced, without too deep investigation, to Mr. Samuel Warren’s admirable novel, “Ten Thousand a Year.” Mr. Robert Buchanan and his collaborateuse, Miss Harriet Jay, have doubled the hero’s fortune, and have called him Thomas Tomkins. Therein it seems to us that their claim to novelty and originality cease. ___

The Morning Post (27 February, 1896 - p.6) VAUDEVILLE THEATRE. “The Romance of the Shopwalker,” by Robert Buchanan and Charles Marlowe, is an old story retold; it plays upon the contrast between the parvenu without education or manners, but with a true sterling character, and the old family, whose nobility has by degrees parted with the wealth that once sustained it. A play is none the worse for treating a well-worn theme, and the authors have in this case cleverly avoided making their highborn personages heartless or ignoble by introducing a scheming blackguard to whose intrigues the difficulties are due. Tomkins, the shopwalker, is the rising assistant in a draper’s shop, and has grown dearer than he is aware of to Dorothy Hubbard, the proprietor’s daughter, when he falls in love with a picture and a name—with Evelyn, daughter of the Earl of Doverdale, whose portrait he has seen in a Society paper. His silly fancy is in a fair way to ruin his prospects in life; it makes Dorothy miserable, prevents Tomkins from doing his work, and disposes his master to dismiss him. Lady Evelyn visits the shop by way of meeting in the private room her cousin and lover Captain Dudley, and Tomkins, with his head turned, makes himself ridiculous and objectionable to both. His redeeming feature is his honest love for his old mother, preserved in spite of qualities in that estimable lady that scarcely square with his new aristocratic aspirations. Lady Evelyn has hardly left the shop when MacCollop, Tomkins’s friend, rushes in with the news that an uncle has died in the West Indies, leaving Tomkins an immense fortune. In the second act Tomkins, the new millionaire, is a guest at Doverdale Castle. He is kindly treated, and though he is excessively vulgar he has wit enough to see that the environment does not suit him, and to feel that his suit with Lady Evelyn is hopeless. But MacCollop, now his business man, entangles matters for him. Tomkins has bought the mortgages on the Doverdale estates out of sheer good nature, intending to give them to Evelyn on the wedding day he hopes for. But MacCollop betrays the secret by telling Lady Munro—Evelyn’s aunt and the Earl’s sister—that Tomkins has bought the mortgages, and he adds, what is not true, that Tomkins intends to ruin the family unless Evelyn is to be his. The old lady, of course, tells this to Evelyn and to the Earl. The Earl is indignant, and refuses to sell his daughter, but Evelyn thinks she ought to sacrifice herself for her father, and when Tomkins, urged on by more lies from MacCollop, proposes to her, she accepts him. In the third act Tomkins is standing for the borough. The other Party make the most of the supposed purchase of an Earl’s daughter and of Tomkins’s alleged neglect of his mother, which latter charge drives the candidate into his one election speech, a good one, plain and to the point. Tomkins, however, discovers at this stage that the purchase of the mortgages has been divulged, and finds out that Evelyn has accepted him, not for love, but to avert ruin from her family. He has an explanation with her, she admits the truth; and he then releases her, presents her with the mortgages, and joins her hand to Captain Dudley’s. ___

The Globe (27 February, 1896 - p.6) “THE ROMANCE OF THE SHOPWALKER.” About the middle of the present century, readers of fiction were convulsed with the adventures of Tittlebat Titmouse, a vulgar, red-haired shopkeeper, or something of the kind, who came into the temporary possession of ten thousand a year, aped the country gentleman, sought to marry into the family of a nobleman, stood for Parliament, and ultimately found his practical experience of affluence as illusive and unsubstantial as the dream of Alnaschar, the barber’s fifth brother, over his peripatetic shop of glass and earthenware. These, the main features, if a distant memory serves us well, of Warren’s “Ten Thousand a Year,” serve with some comparatively unimportant modifications for the three-act comedy of Mr. Robert Buchanan and the lady masquerading as Charles Marlowe, produced yesterday evening at the Vaudeville. The character of the hero has been somewhat elevated and sentimentalised. Not quite such a cad as Tittlebat Titmouse is Thomas Tomkins, whose initials, it will be noticed, are the same as those of his predecessor. His origin is, however, equally obscure, he is no less ignorant, vulgar, familiar, and assertive, he has not an “h” in his speech, except in the case of words in which its presence is an impertinence, nor a spark of information or capacity. What he can boast is a vein of sentiment, as misapplied in its direction as it can well be. ___

The Daily Telegraph (27 February, 1896 - p.5) VAUDEVILLE THEATRE. A merry little farce of a wholesome English type, with a dash of pathos thrown in occasionally to relieve the laughter and give the proper dramatic contrast—just the kind of play that delighted London when Robson was at the Olympic and showing his genius in “The Porter’s Knot” and “Daddy Hardacre”—a homely, funny, well-written, and honest little play—such is “The Romance of the Shopwalker,” produced last night. Of course, we have no Robson to play Thomas Tomkins, which is an initial drawback. But the part gives the opportunity which a Robson would have loved to illustrate, for it is a cockney part, a vulgar part, a part that, with all its outrageous excursions into farce, might become almost tragic in its intensity. At any rate “The Romance of the Shopwalker,” such as it is, such as it has been written, such as it turned out as acted, gave, as far as one could see, genuine satisfaction. The first act went with a roar. It is pure farce. The second act, truth to tell, is a little dull, or seemed so, because the majority of the artists were disconcerted. The third act, where farce is turned into pathos, only failed in feebleness of attack. But it did not matter. The house was pleased. There were rapturous calls after every act, and the curtain was twice raised in order to show the beaming countenance of Robert Buchanan, accompanied by “Charles Marlowe,” who to those familiar with her face looked uncommonly like the once favourite actress and authoress, Miss Harriett Jay. ___

The Stage (27 February, 1896 - p.12) LONDON THEATRES. THE VAUDEVILLE. On Wednesday evening, February 26, 1896, was produced a new comedy, in three acts, by Robert Buchanan and Charles Marlowe, entitled:— The Romance of the Shopwalker. Thomas Tomkins ... Mr. Weedon Grossmith. The first act of the new Buchanan-Marlowe piece opens in a room adjoining the Bon Marché, Dorking, where the proprietor, Mr. Hubbard, is grumbling with everything in general and nothing in particular. MacCollop inquires for his friend Tomkins, whom he wants to see on most important business. Finding he is not about MacCollop leaves a message with Dorothy Hubbard, who is in her father’s office, saying he will call in again shortly as it is most imperative he should see Tomkins. Hubbard objects to his daughter taking messages for his shopman, and Tomkins receives a severe reprimanding from his employer, who tells him that he had better look out for some more suitable employment, as his tastes and ideas are far too big for a shopman. Some consternation takes place, as Lady Evelyn, who has been shopping with her aunt (Lady Munro) and sister (Lady Mabel), is brought into the room in a fainting condition. Tomkins, who has the impertinence to be in love with her, is at his wits’ end to know what to do when her cousin, Captain Dudley, who also is in love with her, comes on the scene. her father, the Earl of Doverdale, has forbidden him the house. He is greatly surprised to learn of the return of the Earl and his sister, lady Munro, who immediately takes Lady Evelyn away. On their departure Mrs. Tomkins arrives, and is not given a very hearty reception by her son, who says he was not intended for a shopwalker, and knows he ought to have been a gentleman born. His friend MacCollop here turns up with the news that a rich uncle has died in the West Indies, leaving him (Tomkins) his entire fortune—£20,000 a year. On the strength of it the party take to champagne, and while they are enjoying themselves heartily Hubbard comes in and is amazed at their conduct, but when things are explained to him he seems quite to enjoy the alteration. Act two is laid in the drawing-room in Doverdale Castle, where Tomkins is the guest, owing to his fortune. He is now petted by the ladies, who, in a quiet way, try to make him more refined, but somehow they are unable to succeed. Lady Munro and her niece, lady Mabel, go from the room, leaving Lady Evelyn and Tomkins alone. The latter is about to propose to lady Evelyn when her cousin, Captain Dudley, appears. A lively scene takes place between the men. After a time Dudley leaves the house, and MacCollop has an interview with Lady Munro, and settles with her that if she can get her brother, the Earl of Doverdale, to consent to his daughter’s engagement with Tomkins—who has purchased the mortgages on the estate—Tomkins will hand them over to Lady Evelyn as a wedding present. MacCollop wishes to marry Dorothy Hubbard, who does not care for him; still, he imagines that by getting Tomkins married he will obtain his promised commission, £3,000, and then win the hand of Dorothy. This act terminates with the engagement of Tomkins and Lady Evelyn, who does not love him, but agrees to sacrifice herself for her father’s sake. In act three we are shown a room in the White Hart, Dorking, where everybody is busy electioneering. MacCollop now appears as Tomkins’s antagonist, bent on doing him all the harm he possibly can. Tomkins and Lady Evelyn come in, the latter looking very ill and worried. being pressed by Tomkins as to the cause, she admits that her anxiety is occasioned by the fact that she does not love him as she should do, but for her father’s sake will marry him. Captain Dudley, who is working against Tomkins, who is standing as the candidate, now comes on the scene, and an altercation takes place between the two men, during which Lady Mabel arrives, and also argues points with her intended brother-in-law as to his birth and education. His mother, not unnaturally, takes his part, she having popped in in the nick of time. While this is going on there is a row outside, created by the electors, who are calling out “Shopwalker” and other similar remarks about the candidate. This so enrages him that he addresses them in his own particular style, which is more forcible than polite. He then publicly disclaims any intention of marrying Lady Evelyn, but persists in her accepting her cousin. At the same time he tells her of his intention to make her a wedding present of all the papers relating to her father’s estate, and admits that his real love is for Dorothy Hubbard, who he proposes to and is accepted by. MacCollop now finds that he has not succeeded with his little game and leaves a dejected man, while all the others are made happy by the turn of the events. Of the play and the acting we shall speak more fully next week. Mr. Weedon Grossmith has a congenial character to interpret in Tomkins, and the remaining characters are in the hands of the capable artists enumerated above. ___

The Manchester Courier and Lancashire General Advertiser (27 Februar,y 1896 - p.5) “The Romance of the Shopwalker,” the new piece by Messrs. Robert Buchanan and “Charles Marlowe,” which was produced at the Vaudeville to-night, is a laughable absurdity, but it is not wholly farcical. It has an under-current of sentiment of an acceptable if familiar kind. A vulgar shopwalker comes into a fortune, abandons the shop, and on the strength of his money gets into fashionable society. He falls in love with an earl’s daughter, who consents to sacrifice herself to save her family from financial ruin. Eventually, however, the parvenu discovers that he has been making a fool of himself, and returns to the lowly-born girl who has long silently loved him. The most unsophisticated playgoer is familiar with this story, which has been the theme of dramatists for centuries, and of novelists, too, for “£10,000 a Year” will be instantly called to mind. Nevertheless, the performance is clever and highly entertaining, and the authors—“Charles Marlowe” by the way being Miss Harriett Jay—were rewarded with a triple call before the curtain. Mr. Weedon Grossmith is exceedingly droll as the infatuated shopwalker, and at the end of the piece succeeded in touching a sympathetic shard. Miss May Palfrey and Mr. David James, too, especially distinguished themselves in a generally strong caste. ___

The Sheffield Daily Telegraph (27 February, 1896 - p.5) “THE SHOP WALKER.” The fortune of the new “Romance of the Shopwalker,” produced at the Vaudeville, was never in doubt. From the raising of the curtain to the falling of the same the house was kept in a flutter of merriment. It was not only that Mr. Weedon Grossmith had given us the character of an ideal shopman with ambitious yearnings, but the other characters also were full of life and originality. There was Miss Victor, an extraordinary old lady, whose homeliness was only exceeded by her affection for her son; there was Mr. David James’s McKillop, a Scotch clerk; also the matter-of-fact shopkeeper, the crafty lawyer, and Dorothy Hubbard, the lovable daughter of the proprietor, prettily impersonated by Miss Annie Hill. The story of the play is of the shopwalker’s aspirations, and his killing affection for the lovely daughter of the Earl of Doverdale. This, of course, was the part assigned to Miss May Palfrey, who looked the part to perfection, and wore several costumes faultless in tone and beauty. “Oh, that I were nobly born,” was the frequently-uttered cry of Tompkins, the shopwalker. You may fancy the fervour with which the dapper little man, as Mr. Weedon Grossmith presented him to us, uttered this soulful cry. Nor need one describe the ecstacy with which he received the intimation that an uncle had left him heir to twenty thousand a year and accumulations. Tompkins in the second act, as the man of fortune, was, of course, a very different man to Tompkins the shopwalker. He was, if anything, more amusing, although the act was streaked with seriousness, in that the beauteous Lady Evelyn, to save the impecunious peer, her papa, had consented to become Mr. Tompkins’ own, thereby sacrificing her own happiness with the handsome and also impecunious cousin, capably presented by Mr. Sydney Brough. The third act, with all the humour of an election, witnesses, of course, the fall of Tompkins’s matrimonial castle in the air, and the pairing of the young people in proper order—Dorothy, the shopkeeper’s daughter, to the shopwalker, and Lady Evelyn to the handsome captain. Mr. Robert Buchanan and Mr. Charles Marlowe are to be congratulated on the success of their play, and Mr. Weedon Grossmith also on the acquisition of a part that fits him like a glove. The reception of the play was enthusiastic. ___

The Leeds Mercury (28 February, 1896 - p.5) With Mr. Weedon Grossmith in the chief rôle, supported by a talented company, which includes Miss Annie Hill, Miss May Palfrey, Miss M. A. Victor, Mr. Sydney Warden, and Mr. Sydney Brough, the new three-act comedy at the Vaudeville, entitled “The Romance of the Shopwalker,” is a very amusing piece, and is likely to have a good run. The authors, Mr. Robert Buchanan and “Charles Marlowe” (Miss Harriett Jay), have made a funny character of the shopwalker of the Dorking Bon Marché, who falls in love with a lady of title, comes into a fortune, stands for Parliament, and subsequently marries his master’s daughter. The farce was first produced at Colchester on Monday, and was introduced to London last night with great success. ___

The Essex County Chronicle (28 February, 1896 - p.7) “THE ROMANCE OF THE SHOPWALKER.”—The new comedy, by Robert Buchanan and Chas. Marlowe, was produced for the first time on any stage at Colchester Theatre on Monday evening by Mr. Weedon Grossmith and his entire London company, by whom it was to be played at the Vaudeville Theatre, London, on Wednesday. The caste included Mr. Weedon Grossmith, Mr. Sydney Warden, Mr. Sydney Brough, Mr. Fredk. Volfe, Mr. David James, Miss Talbot, Miss May Polfrey, Miss Nina Boucicault, Miss Annie Hill, and Miss M. A. Victor. ___ The Dundee Courier (28 February, 1896 - p.5) NEW PLAYS IN LONDON. In the new piece, “The Romance of the Shopwalker,” which was brought out with success at the Vaudeville the other night, Mr Robert Buchanan and his lady collaborateur, who assumed the nom de plume of “Charles Marlowe,” seemed to have borrowed a few hints from Warren’s “Ten Thousand a Year.” The hero, Thomas Tompkins, passed through experiences akin to those of Tittlebat Titmouse, and with very similar results. The play is admirably acted by Mr Weedon Grossmith and his company. ___

The Penny Illustrated Paper (29 February, 1896 - p.3) |

|

|

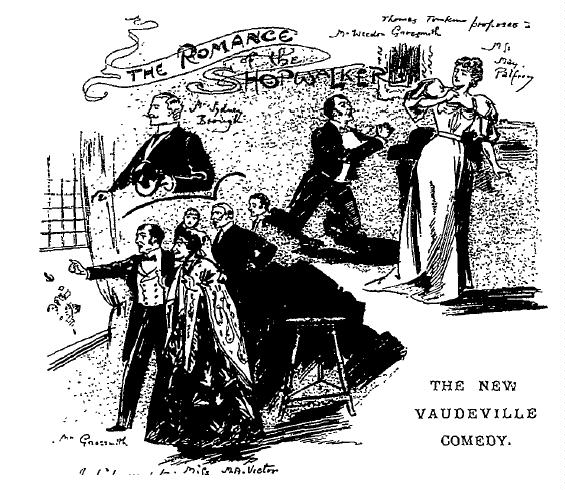

"The Romance of the Shopwalker." In the novel of “Ten Thousand a Year,” fortune suddenly smiles upon one of humble origin. The authors of the new Vaudeville play (MM. Robert Buchanan and Charles Marlowe) have doubled that amount, and it is to the tune of £20,000 a year that Thomas Tomkins, his soul “rising and fermenting” beneath his romantic waistcoat, proudly steps into “high life.” His imagination fired by novelette-reading, he no longer deigns to notice sweet Dorothy, daughter of the owner of the Dorking Bon Marché, but aspires to the hand of Lady Evelyn, who naturally prefers her cousin, Captain Dudley. Very amusingly are the pretentious Tomkins and his plebeian mother held up to ridicule. Much fun is made of the snobbish hero’s standing for Parliament; and a good point secured by his access of generosity to Lady Evelyn, and his ultimate pairing with Dorothy. As mother and son, Miss M. A. Victor and Mr. Weedon Grossmith are fairly in their element. Mr. David James makes a hit as MacCollop, the designing Scot. Needless to add, Miss May Palfrey charms everyone as Lady Evelyn, for this fair young actress is one of the prettiest and most captivating ladies on the stage. With Miss Palfrey may be coupled the fascinating Dorothy of Miss Annie Hill and the Lady Mabel of Miss Nina Boucicault; and Mr. Frederick Volpé and Mr. Sydney Brough make their mark as the proprietor of the Bon Marché and the lucky Captain of this exceedingly droll and diverting comedy. ___

The Era (29 February, 1896 - p.9) THE LONDON THEATRES. THE VAUDEVILLE Thomas Tomkins .......... Mr WEEDON GROSSMITH No special erudition and experience would be needed to point out the resemblance between The Romance of the Shopwalker—which had preliminary production at the Theatre Royal, Colchester, on Monday—and previous plays. It reminds one of The Parvenu in plot, and of Samuel Warren’s novel of “Ten Thousand a-Year” in the character of its hero. After all, what do these reminiscences matter? The important fact in connection with Mr Robert Buchanan and Mr “Charles Marlowe’s” piece is that it gave us a merry two hours and a-half at the vaudeville Theatre on Wednesday, evoked a great deal of laughter, and trembled, at times, on the verge of pathos. Indeed, the chief fault lay with the audience, who were inclined to see only the ridiculous side of Thomas Tomkins’s adventures, and often laughed in the wrong place. But we must take out audiences as we find them, shallowness, prejudices, and all; and we counsel Mr Buchanan and his collaborator to humour their patrons by removing a few of the liens in which Tomkins asserts his good qualities. ___

The Daily Telegraph (29 February, 1896 - p.8) There are some actors so physically suited to well-known characters in fiction that they actually suggest a play before it is even written. Take the characters of Dickens alone. Samuel Emery was a born Peggotty. You could not look upon John Clarke without thinking of Quilp, George Fawcett Rowe could not fail to succeed as Micawber, and Miss Jennie Lee, as Jo, simply walked out of “Bleak House” on to the stage. It was not strange, therefore, that Mr. Weedon Grossmith should have been implored by his best friends, for eight or nine years past, to look at Samuel Warren’s “Ten Thousand a Year,” and see if Tittlebat Titmouse, the little Cockney draper’s assistant who comes into a fortune, goes into society, falls in love with a well-bred woman, and eventually reigns her from a generous motive, would not suit him “down to the ground.” His invariable answer has been, “If someone would write a play on the subject, I should like to have it.” So far it went and no further. Scenarios were suggested, but never written; scenarios were sent in, but in such a sketchy form that they were valueless. The subject was in the air, and the tangible play was never forthcoming until Robert Buchanan and Miss Harriett Jay offered to the management a work in a fit state to be considered. This, of course, was “The Romance of the Shopwalker,” which was read, accepted, rehearsed, and successfully acted. Whereupon the inevitable happened. All who intended to give a Tittlebat Titmouse to the stage and didn’t are angry because someone else forestalled them, not with a scenarios, which could be found by any amateur in the book, but with a play that couldn’t So, for the moment, the air is full of rumours and dark threats, at which the little Tittlebat Titmouse very sensibly laughs, and so do author and authoress, who naturally win because they raced like the hare and did not go to sleep like the tortoise. ___

The Sporting Times (29 February, 1896 - p.6) THINGS THEATRICAL . . . VAUDEVILLE THEATRE.—”THE MR. ROBERT BUCHANAN and Miss Harriet Jay, who is the Charles Marlowe of the collaboration, have gone to Samuel Warren’s admirable novel, “Ten Thousand a Year,” for the basis of their domestic comedy, The Romance of the Shopwalker, produced on Wednesday evening last by Mr. Weedon Grossmith at the Vaudeville Theatre with every sign of success. TITTLEBAT TITMOUSE not unnaturally suggested to the authors a capital prototype for Mr. Weedon Grossmiths’s idiosyncrasies, and Tittlebat Titmouse accordingly he is in the play, with the exception that he has been rechristened Thomas Tomkins. His fortune has been doubled by the authors, and he has to go through the whole gamut of conventionality in the course of his three hours’ existence on the boards. THE collaborators have certainly failed to display much ingenuity in their treatment of such trite themes as an impoverished Earl with two marriageable daughters, the elder of whom, though deeply attached to a penniless cousin, is willing to sacrifice herself on the shrine of matrimony to the vulgar little parvenu, whose heart is as big as his body, and who buys up the dear old familiar mortgage deeds of the impecunious nobleman to save him on account of his daughter, whom the tender-hearted little vulgarian imagines he adores. THE great fault of the author’s work is that all the characters are, if not impossible, extremely unnatural. A man with such an outrageous coating of vulgarity would be quite impossible nowadays in a position of prominence and trust in such an establishment as even the Dorking Bon Marché. The son of a respectable chemist and druggist in these days would have received an education that must have toned down a vast amount of his blatant vulgarity, and the deceased chemist and druggist during his married life would have certainly eliminated much of the commencement de siècle flavour of the partner of his sorrows and joys, as represented by Miss M. A. Victor. THE chief merits which outweigh the faults of the piece are the wholesome tone of the play and the genuine fun that exists in considerable profusion throughout. The comedy element is the strong part of the play; in the more serious portions the authors are not so felicitous, nor is Mr. Weedon Grossmith at home. For this reason it would be well for him to cut down the would-be pathos of the end of the last act as much as possible, for as given on the first night it appeared tediously redundant and tautologic. IT is only in this portion of the character that Mr. Grossmith is not absolutely excellent. It is not his fault that the authors have laid on the vulgarity with a trowel instead of with a brush; but it is due to him that the comic features of the character are emphasised. Miss may Palfrey gives a charming performance of the Earl’s daughter. It is a line in which we have not hitherto seen her, and in which she proves herself as completely proficient as in the lines she has previously so well succeeded. IN my opinion the two best performances in the piece, if it is not invidious to say such a thing where all are good, are those of Miss Nina Boucicault, as the Lady Mabel, and of Mr. David James, as Andrew McKollop. Miss Nina Boucicault’s performance is brimming over with saucy humour, although the part is but a very insignificant one in point of length. Mr. David James’s Scotch agent is an admirable study of character admirably portrayed. MISS VICTOR has far too little to do, but what she has is as good as can be. Mr. Sydney Brough is completely thrown away on the colourless part of Captain Dudley. Mr. Frederick Volpe gives a clever little sketch of Samuel Hubbard, proprietor of the Dorking Bon Marché. Mr. Sydney Warden, as the Earl of Doverdale, succeeds in investing a conventional part with some semblance of character. Miss M. Talbot is well in the picture as the scheming Lady Munro, and Miss Annie Hill is ill-served by the authors, but makes the most possible out of the doleful Dorothy Hubbard, who cherishes a secret affection for the little shop-walker. THE play was received with most cordial demonstrations of genuine approval, actors and authors receiving double calls at the fall of the curtain. Mr. Weedon Grossmith should do well with his new play both in London and in the provinces. ___

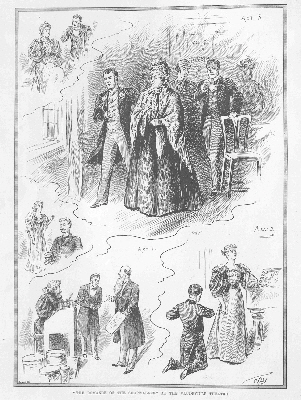

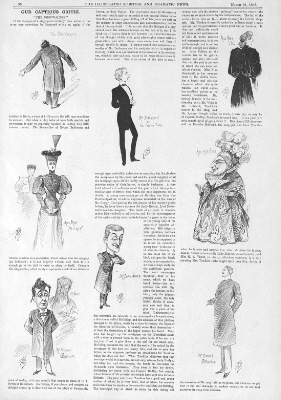

The Illustrated Sporting and Dramatic News (29 February, 1896 - p.7) NEW PLAY AT THE VAUDEVILLE THEATRE. The Romance of the Shopwalker, a new comedy by Messrs. Robert Buchanan and Charles Marlowe, was produced with every sign of success at the Vaudeville on Wednesday night. There is nothing in it that is very new, and very little that is true in the sense of being accurate in its study of the life and character depicted. But, on the other hand, there is plenty that is entertaining in its straightforward and rather old-fashioned way, while there is exactly the hint of homely pathos which people like to find underlying humour of the domestic order. The plot is thin, but just sufficient to afford material for three short acts; and the dialogue, if not brilliant, is fairly equal to the demands of a not too exacting occasion. (p.8) “THE ROMANCE OF THE SHOPWALKER” FROM this new piece, which was to be produced at the Vaudeville Theatre on Wednesday evening last, we print sketches taken at the dress rehearsal. The story is briefly that of a shopwalker who loves a lady of title and has ambitions of society and political distinction. A legacy of £20,000 a year enables him to attain some of his hopes, though he does not eventually marry the object of his adoration. He is good enough to let her off—although she is willing to sacrifice herself for her impecunious father—on her confession that her heart belongs to another. Our artist has represented: from Act I. the humiliation of the hero—he is reprimanded by the proprietor for reading society papers during business hours; from Act II. his proposal to Lady Evelyn after his accession to wealth; and from Act III. the scene in which, having told the mob to go hang, he is elected M.P. by acclamation on the ground of his independence. The smaller sketches show the incident in which the unscrupulous lawyer, McCollop—who is to have a commission on the aristocratic marriage—secures Lady Munroe’s assistance from the fear of ruin; and Captain Dudley, the favoured lover of the heroine, talking over matters with Lady Mabel, the lively sister of the apparently doomed maiden. |

|

|

|

The Illustrated Sporting and Dramatic News (28 March, 1896 - p.20) The Romance of the Shopwalker, the origin of which is still being angrily discussed in some quarters, comes off at the Vaudeville this week. This is not because Messrs. Buchanan and Marlowe’s amusing domestic comedy was in any way failing in attractive power, but because Mr. Weedon Grossmith’s term at Messrs. Gatti’s theatre has come to an end. He proposes very shortly to take a tour round the country. _____

The Romance of the Shopwalker - continued

|

|

|

|

|

|

|