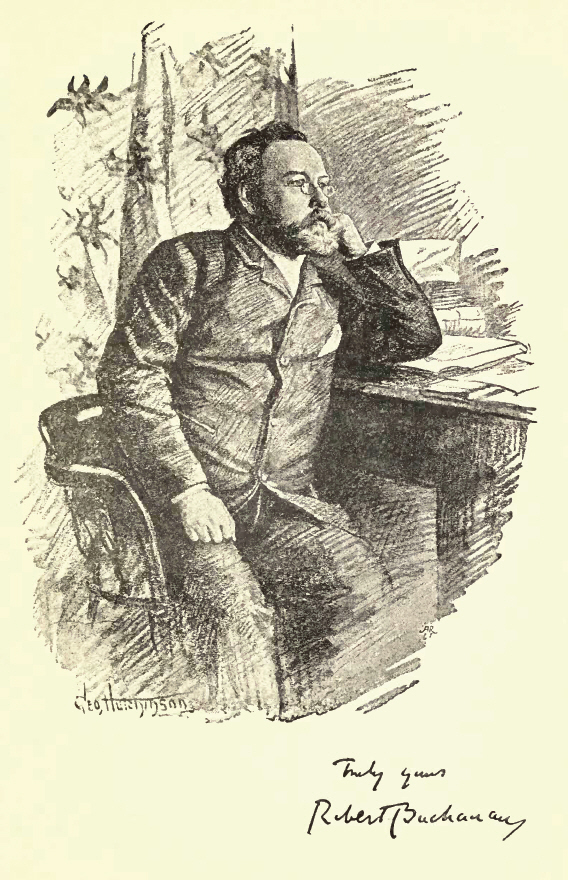

ROBERT WILLIAMS BUCHANAN (1841 - 1901)

|

ROBERT WILLIAMS BUCHANAN (1841 - 1901) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Essays - ‘My First Book’

From The Idler - May 1893. (Reprinted in My First Book (London: Chatto & Windus, 1894).)

My First Book

‘UNDERTONES’ AND ‘IDYLS AND LEGENDS BY ROBERT BUCHANAN

MY first serious effort in literature was what I may call a double-barrelled one; in other words, I was seriously engaged upon two books at the same time, and it was by the merest accident that they did not appear simultaneously. As it was, only a few months divided one from the other, and they are always, in my own mind, inseparable, or Siamese, twins. The book of poems called ‘Undertones’ was the one; the book of poems called ‘Idyls and Legends of Inverburn’ was the other. They were published nearly thirty years ago, when I was still a boy, and as they happened to bring me into connection, more or less intimately, with some of the leading spirits of the age, a few notes concerning them may be of interest. The terrible City whose neglect is Death, and to take it by storm. It seemed so easy! ‘Westminster Abbey,’ wrote my friend to a correspondent ; ‘if I live, I shall be buried there—so help me God!’ ‘I mean, after Tennyson’s death,’ I myself wrote to Philip Hamerton, ‘to be Poet Laureate!’ From these samples of our callow speech, the modesty of our ambition may be inferred. Well, it all happened just as we planned, only otherwise! Through some blunder of arrangement we two started for London on the same day, but from different railway stations, and, until some weeks afterwards, one knew nothing of the other’s exodus. I arrived at King’s Cross Railway Station with the conventional half-crown in my pocket; literally and absolutely half-a-crown; I wandered about the Great City till I was weary, fell in with a Thief and Good Samaritan who sheltered me, starved and struggled with abundant happiness, and finally found myself located at 66 Stamford Street, Waterloo Bridge, in a top room, for which I paid, when I had the money, seven shillings a week. Here I lived royally, with Duke Humphrey, for many a day; and hither, one sad morning, I brought my poor friend Gray, whom I had discovered languishing somewhere in the Borough, and who was already death-struck through ‘sleeping out’ one night in Hyde Park. 1 ‘Westminster Abbey—if I live. I shall be buried there!’ Poor country singing-bird, the great Dismal Cage of the Dead was not for him, thank God! He lies under the open Heaven, close to the little river which he immortalised in song. After a brief sojourn in the ‘dear old ghastly bankrupt garret at No. 66,’ he fluttered home to die. 1 See the writer’s Life of David Gray. |

|

|

To that old garret, in these days, came living men of letters who were of large and important interest to us poor cheepers from the North: Richard Monckton Milnes, Laurence Oliphant, Sydney Dobell, among others, who took a kindly interest in my dying comrade. But afterwards, when I was left to fight the battle alone, the place was solitary. Ever reserved and independent, not to say ‘dour’ and opinionated, I made no friends, and cared for none. I had found a little work on the newspapers and magazines, just enough to keep body and soul alive, and while occupied with this I was busy on the literary twins to which I referred at the opening of this paper. What did my isolation matter, when I had all the gods of Greece for company, to say nothing of the fays and trolls of Scottish Fairyland? Pallas and Aphrodite haunted that old garret; out on Waterloo Bridge, night after night, I saw Selene and all her nymphs; and when my heart sank low, the fairies of Scotland sang me lullabies! It was a happy time. Sometimes, for a fortnight together, I never had a dinner—save, perhaps, on Sunday, when a good-natured Hebe would bring me covertly a slice from the landlord’s joint. My favourite place of refreshment was the Caledonian Coffee House in Covent Garden. Here, for a few coppers, I could feast on coffee and muffins—muffins saturated with butter, and worthy of the gods! Then, issuing forth, full-fed, glowing, oleaginous, I would light my pipe, and wander out into the lighted streets. |

|

|

At this time, I was (save the mark!) terribly in earnest, with a dogged determination to bow down to no graven literary idol, but to judge men of all ranks on their personal merits. I never had much reverence for gods of any sort; if the superior persons could not win me by love, I remained heretical. So it was a long time before I came close to any living souls, and all that time I was working away at my poems. Then, a little later, I used to go o’ Sundays to the open house of Westland Marston, which was then a great haunt of literary Bohemians. Here I first met Dinah Muloch, the author of ‘John Halifax,’ who took a great fancy to me, used to carry me off to her little nest on Hampstead Heath, and lend me all her books. At Hampstead, too, I foregathered with Sydney Dobell, a strangely beautiful soul, with (what seemed to me then) very effeminate manners. Dobell’s mouth was ever full of very pretty Latinity, for the most part Virgilian. He was fond of quoting, as an example of perfect expression, sound conveying absolute sense of the thing described, the doggrel lines— Down the stairs the young missises ran The sibilants in the first line, he thought, admirably suggested the idea of the young ladies slipping along the banisters and peeping into the hall! Poet gentle hearted, Full of my dead friend, I spoke of him to Lewes and George Eliot, telling them the piteous story of his life and death. Both were deeply touched, and Lewes cried, ‘Tell that story to the public’; which I did, immediately afterwards, in the Cornhill Magazine. By this time I had my Twins ready, and had discovered a publisher for one of them, Undertones. The other, Idyls and Legends of Inverburn, was a ruggeder bantling, containing almost the first blank verse poems ever written in Scottish dialect. I selected one of the poems, ‘Willie Baird,’ and showed it to Lewes. He expressed himself delighted, and asked for more. I then showed him the ‘Two Babes.’ ‘Better and better!’ he wrote; ‘publish a volume of such poems and your position is assured.’ More than this, he at once found me a publisher, Mr. George Smith, of Messrs. Smith and Elder, who offered me a good round sum (such it seemed to me then) for the copyright. Eventually, however, after ‘Willie Baird’ had been published in the Cornhill, I withdrew the manuscript from Messrs. Smith and Elder, and transferred it to Mr. Alexander Strahan, who offered me both more liberal terms and more enthusiastic appreciation. 1 I have given a detailed account of Peacock in my Look Round Literature. |

|

|

It was just after the appearance of my story of David Gray in the Cornhill that I first met, at the Priory, North Bank, with Robert Browning. It was an odd and representative gathering of men, only one lady being present, the hostess, George Eliot. I was never much of a hero-worshipper, but I had long been a sympathetic Browningite, and I well remember George Eliot taking me aside after my first tête-à-tête with the poet, and saying, ‘Well, what do you think of him? Does he come up to your ideal?’ He didn’t quite, I must confess, but I afterwards learned to know him well and to understand him better. He was delighted with my statement that one of Gray’s wild ideas was to rush over to Florence and ‘throw himself on the sympathy of Robert Browning.’ 1 O those ‘Tendencies of one’s Time’! O those dismal Phantoms, conjured up by the blatant Book-taster and the indolent Reviewer! How many a poor Soul, that would fain have been honest, have they bewildered into the Slough of Despond and the Bog of Beautiful Ideas!—R. B. |

|

|

For one other thing, also, the Neophyte in Literature had better be prepared. He will never be able to subsist by creative writing unless it so happens that the form of expression he chooses is popular in form (fiction, for example), and even in that case, the work he does, if he is to live by it, must be in harmony with the social and artistic status quo. Revolt of any kind is always disagreeable. Three-fourths of the success of Lord Tennyson (to take an example) was due to the fact that this fine poet regarded Life and all its phenomena from the standpoint of the English public school that he ethically and artistically embodied the sentiments of our excellent middle-class education. His great American contemporary, Whitman, in some respects the most commanding spirit of this generation, gained only a few disciples, and was entirely misunderstood and neglected by contemporary criticism. Another prosperous writer, to whom I have already alluded, George Eliot, enjoyed enormous popularity in her lifetime, while the most strenuous and passionate novelist of her period, Charles Reade, was entirely distanced by her in the immediate race for Fame. In Literature, as in all things, manners and costume are most important; the hall-mark of contemporary success is perfect Respectability. It is not respectable to be too candid on any subject, religious, moral, or political. It is very respectable to say, or imply, that this country is the best of all possible countries, that War is a noble institution, that the Protestant Religion is grandly liberal, and that social evils are only diversified forms of social good. Above all, to be respectable, one must have ‘beautiful ideas.’ ‘Beautiful ideas’ are the very best stock-in-trade a young writer can begin with. They are indispensable to every complete literary outfit. Without them, the short cut to Parnassus will never be discovered, even though one starts from Rugby. ___

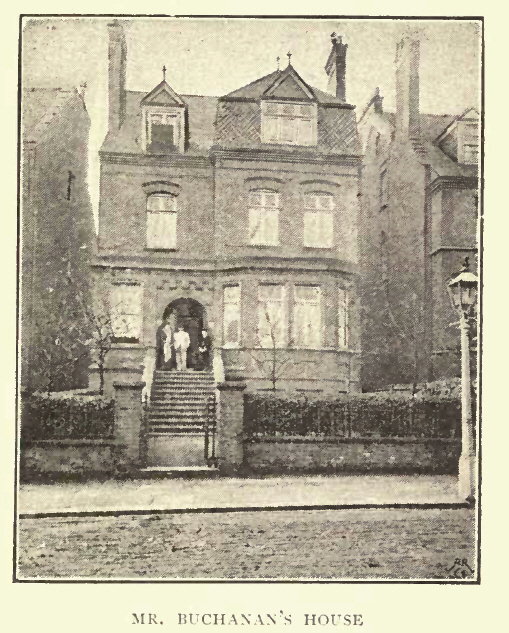

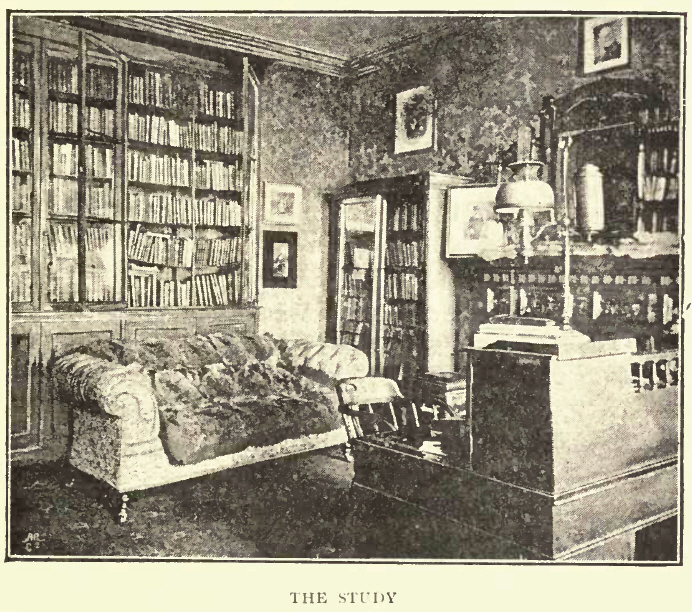

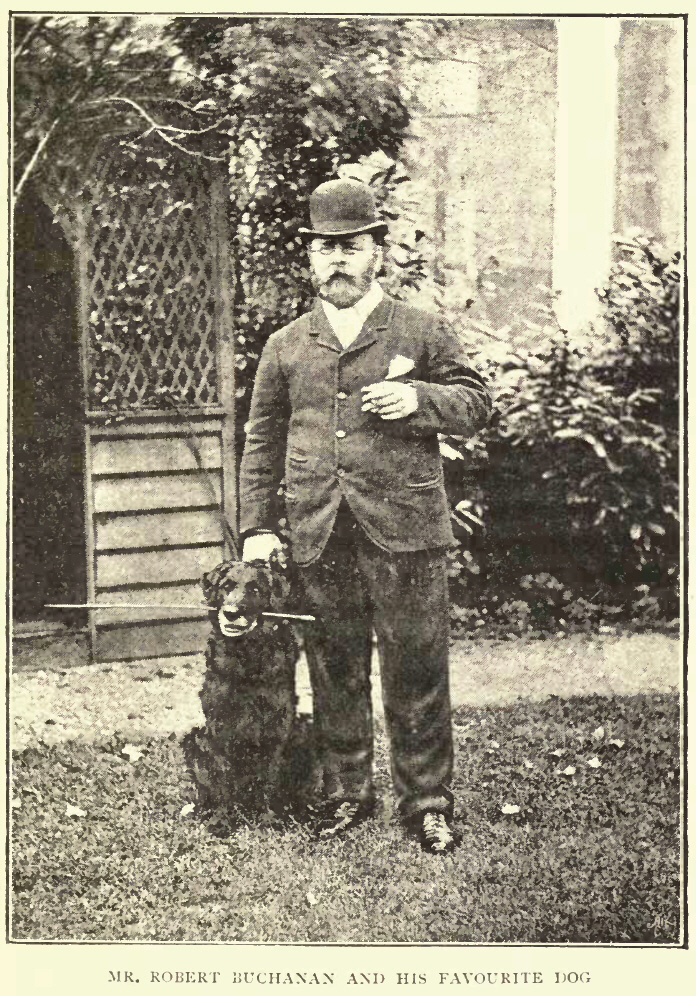

[Note: The transcription above is taken from the collection of articles reprinted by Chatto & Windus under the title: My First Book. In the original version in The Idler there were additional photographs of Buchanan’s current residence, 25 Maresfield Gardens, South Hampstead, London. They are reproduced below: |

|

|

The Entrance Hall. |

|

|

The Dining Room. |

|

|

The Drawing Room. The drawing of Buchanan is by George Hutchinson and the photographs by Messrs. Fradelle and Young. ___

Since I’d never come across a reference to ‘Duke Humphrey’ before, I thought I would add the following explanation, taken from Brewer’s Dictionary of Phrase & Fable: Humphrey. To dine with Duke Humphrey. To have no dinner to go to. Humphrey, Duke of Gloucester, son of Henry IV, the “Good Duke Humphrey” was renowned for his hospitality. At death it was reported that a monument would be erected to him in St. Paul’s but his body was interred at St. Albans. The tomb of Sir John Beauchamp (d. 1358), on the south side of the nave of old St. Paul’s, was popularly supposed to be that of the Duke; and when the promenaders left for dinner, the poor stay-behinds, who had no dinner to go to, or who feared to leave the precincts of the cathedral because, once outside they could be arrested for debt, used to say to the gay sparks who asked if they were going, that they would “dine with Duke Humphrey” that day. Though little coin thy purseless pocket line, HAYMAN: Quodlibet (Epigram on a Loafer), 1628. ___

Buchanan’s contribution to the ‘My First Book’ feature of Jerome K. Jerome’s magazine, The Idler, appeared in the May 1893 edition, which is available at Project Gutenberg . The articles were collected and published by Chatto & Windus in 1894 as My First Book. A second edition appeared in 1897 and this was reprinted in 2003 by the University Press of the Pacific, Honolulu, Hawaii (ISBN: 1-4102-0759-5). The contributors to My First Book are as follows: Grant Allen, R.M. Ballantyne, Walter Besant, M. E. Braddon, Robert Buchanan, Hall Caine, Marie Corelli, A. Conan Doyle, H. Rider Haggard, Bret Harte, Jerome K. Jerome, Rudyard Kipling, David Christie Murray, James Payn, ‘Q’, Morley Roberts, F. W. Robinson, W. Clark Russell, George R. Sims, Robert Louis Stevenson, John Strange Winter and I. Zangwill. My First Book is now available at the Internet Archive where it can be downloaded in a variety of formats, including an audio version thanks to LibriVox.] ___

Reviews: Robert Buchanan and the Magazines _____

Back to Essays

|

|

|

|

|

|

|