ROBERT WILLIAMS BUCHANAN (1841 - 1901)

|

ROBERT WILLIAMS BUCHANAN (1841 - 1901) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

BUCHANAN ARTICLES

The Yorkshire Post (16 June, 1884 - p.6) Mr W. Hodgson, editor of the Fifeshire Journal, has begun, in the columns of that paper, to publish a series of papers dealing with his personal recollections of memorable men and things. Chapter I., which is entitled “Some Old Acquaintances,” deals with Charles Gibbon, Robert Buchanan, and Henry Irving. . . . MR ROBERT BUCHANAN.—The editor of the Fifeshire Journal, in some “Sketches, Personal and Pensive,” which he is publishing in that paper, gives the following interesting epitome of Mr Robert Buchanan’s literary growth:— [Note: _____

|

|

|

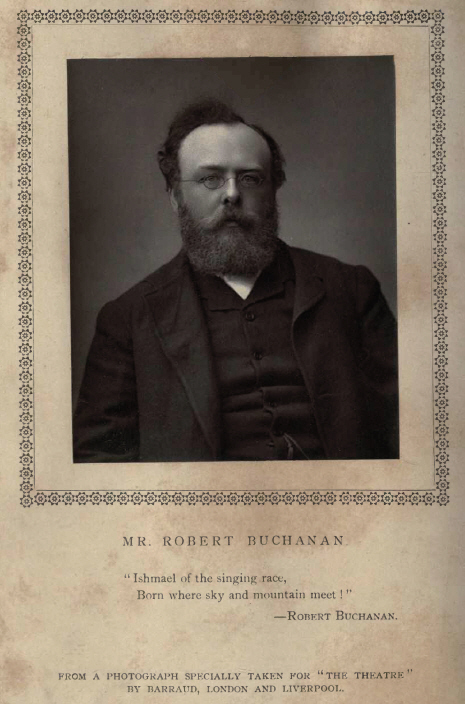

Mr. Robert Buchanan, the subject of our portrait, was born at Caverswall, Staffordshire, in 1843. His father was a well-known disciple of Robert Owen. At ten years of age he was taken to Glasgow, and there studied at the High School and University. More fortunate than his friend David Gray, he, after years of trial, unaided and without patronage, struggled and conquered, and published his first volume of poems, “Undertones,” which was hailed by the “Athenæum” as the advent of a new poet. He contributed to various magazines, collaborated with John Morley in the “Literary Gazette,” and edited for a short time the “Welcome Guest.” His first play, “The Witch Finder,” was produced at Sadler’s Wells in 1861. “Idylls and Legends of Inverburn,” “London Poems,” “North Coast Poems,” and “Ballads from the Scandinavian” followed each other in rapid succession and were received with great favour. The latter were founded on his experiences as a newspaper correspondent in Schleswig-Holstein during the Danish War. From Oban, where he was living for some time in ill-health, he contributed to the “Spectator” his “Hebrid Isles.” His most famous novels are “The Shadow of the Sword,” and “God and the Man.” The latter he dramatized for the Adelphi Theatre as “Stormbeaten.” Mr. Buchanan is the author of “A Madcap Prince,” and of “The Nine Day’s Queen,” but his work as a dramatist, up to the present time, will be best appreciated in “Sophia,” which ran at the Vaudeville for 500 nights; in “Joseph’s Sweetheart,” another great success at the same theatre; and in “A Man’s Shadow,” the greatest pecuniary result at the Haymarket Theatre. He is also the author of “Doctor Cupid,” and “Alone in London.” His work, “The City of Dream,” has evoked the highest comment. Mr. Buchanan’s forthcoming reprint of his plays and accompanying essay on “The Drama as Literature” will be anxiously looked for. His latest adaptation, “Theodora,” lately produced at Brighton, is very highly spoken of by provincial papers, Miss Grace Hawthorne in the title rôle and Mr. Fuller Mellish as Andreas, having gained unstinted praise; and we are shortly to sit in verdict on a new play of his, entitled “Man and the Woman,” at a matinée in which Miss Myra Kemble, an actress of Australian reputation, will appear. Mr. Robert Buchanan has, as is well known, the courage of his opinions, and writes fearlessly on many subjects; but he is always chivalrous, and bears the numerous encounters he invites with equanimity and good nature. _____

The Echo (20 October, 1890 - p.1) “ECHO” PORTRAIT GALLERY MR. ROBERT BUCHANAN. Amidst the post-curtain tumult of a first night there is no figure with which the play-going public are just now better acquainted than that of a portly, sturdy gentleman, grasping a formidable staff in one hand, and in the other no patent Gibus, but a light-coloured deerstalker hat, though so far conforming to les convenances as to wear the orthodox claw- hammer and white neck-band, who looks out with a mild expression of wonderment from behind benevolent gold spectacles, bows obesely, and disappears, not a hair of his ample light beard having been stirred by the eulogies or execrations of the fevered audience, these being twin delicacies on which he has too often before both supped and dined to repletion. This substantial apparition is that of Mr. Robert William Buchanan, Scottish bard and reviewer, and very much else—one of the most interesting entities in the literary world of England of to-day. ___

The Echo (22 October, 1890 - p.1) “MR. ROBERT BUCHANAN.” TO THE EDITOR OF THE ECHO. SIR,—I have only one fault to find with the very good-natured picture of myself in your Portrait Gallery (Monday last, Oct. 20), and the fault is that your contributor makes me far too virtuous. Unconsciously, and I am sure unwillingly, he echoes the clamour of a clique heard loudly ever since I criticised adversely the English followers of Gautier and Baudelaire, and branding me as a severe moralist (save the mark!) he leaves me in the society of Mr. Collette and the Vigilance Committee. I know how useless it is to protest—to point out that, so far from placing French writers “in the pillory of my detestation,” I have been among the first to welcome the strong men among them; that I have defended Zola against the diatribes of Mr. Howells and the damning apologies of Mr. Stevenson; that I have expressed my sympathy for all full-blooded writers from Chaucer to Byron, from Rabelais down to Paul de Koch; that I have upheld and defended both the “Kreutzer Sonata” on the bookstalls and the posters of Zæo on the hoardings; that I have, in a word, always disapproved of the public or private censorship of literature and literary morals. All is in vain. To have expressed my objection to certain emasculated forms of Art and Poetry is to be a Puritan, and unless I do something very desperate, I shall be classed as a Puritan all my life! ___

The Echo (27 October, 1890 - p.2) ROBERT BUCHANAN AND WALT WHITMAN. Mr. Robert Buchanan can be charming on occasion, and adds to his heavy “slogging” powers a playful wit rare among his compatriots—witness his recent sparkling comment on our portrait of himself. He inverts Polonius’s advice, and denies a virtue though he has it. But we think he somewhat abuses the word Puritan. It certainly conveys no reproach, but is rather a title in which to rejoice; and not even akin to prude and prurient with which he surely confounds it. He pleads not guilty to having “reproved” Walt Whitman for “unchastity of expression.” His essay on the “clear forerunner of the great American poets, long yearned for,” is certainly nobly sympathetic; but in it he permits himself to talk of Whitman’s “needless bestialities,” and speak of some of the trans-Atlantic bard’s passages as “very coarse and silly,” “unfit for Art,” and “rank nonsense.” Surely such expressions cover ours. As Mr. Dick allowed King Charles’s head to greatly impede the progress of his memorial, so Mr. Buchanan permits the fancied influence of those who are cheaply grouped as the “Modern French Sapphic poets” to frequently thwart his critical judgment. There are people who think the robust Mr. Buchanan—and it may be greatly to his credit—to be so utterly out of sympathy with this school, from Alfred de Musset down to Catulle Mendes, as to be incapable of rightly understanding them. It is unwise to prophesy at any time, particularly with regard to a libel action not yet even sub judice. If Mr. Buchanan never gets a “light” as to our riddle, it may, perhaps, be well for him—or for others. _____

The Echo (11 December, 1893 - p.1) NOVELS AND NOVELISTS. XII.—MR. ROBERT BUCHANAN. There is no more interesting personality in modern literature than that of Mr. Robert Buchanan. Clever journalists have thought to solve the problem which its strange contradictions present by ascribing to him a double nature — the one dreamy, idealistic, and romantic, seen in the grand thoughts and beautiful expressions of his poems and novels, the other ferocious and cantankerous, displayed in his controversial writings. The suggestion is an apt one. Mr. Buchanan is unfortunately, too like the prickly pear, which always exposes its worst side, as though that were the only one. Browning’s assertion, “I was a fighter ever,” might well be our subject’s motto in a more material sense. There are, indeed, few prominent men of letters whom at one time or another he has not assailed. He partly rose to fame by an attack upon Rossetti. For his harshness there he amply and honourably atoned, but he has been in the wars ever since. The “young men” of literature have felt his scathing sarcasm when under that cognomen be joined together such strange bedfellows as Mr. R. L. Stevenson, Mr. Henry James, Mr. William Archer, Mr. Andrew Lang, and Mr. George Moore. In his hatred of realism he has given even to Mr. Meredith as well as to Mr. Hardy the gibing epithet of “Literary Undertaker.” Our dramatists have not been spared—Mr. Pinero, Mr. Jones, and Mr. Oscar Wilde have all come under the lash. Finally, he has provoked the animosity of the members of our literary ant-hill by insisting upon the demoralising influence of the profession of literature. Unfortunately, none of Mr. Buchanan’s opponents understand that they are merely offensive for the moment as the representatives of a principle. His wrath is expended as soon as expressed, while he often earns lifelong foes with every stroke of his pen. _____ Mr. Buchanan has told the world in occasional bursts of confidence the story of his long battle for fame and success, and of the terrible sufferings it entailed. He began life as a poet, and it was only when he found that verse would not bring him bread and cheese that he took to other walks of literature. But he hit upon his true vocation when he applied himself first to poetry. Although he has a couple or more of grand novels, and is one of our cleverest essayists and letter-writers, he is before all things a poet. His splendid command of language, and his brilliant imagination, allied with a natural ear for rhyme and rhythm, have enabled him to produce some of the finest verse of this generation—witness the startling originality of “The Ballad of Judas Iscariot,” or the fine thought of “The Wandering Jew,” or “The City of Dreams”; while it is the glowing descriptions and poetic diction that help to give to his two best novels their epic grandeur. In both he has selected magnificent themes. One describes the horrors of war and the terrible fate of a French peasant who, for conscience sake, refused the conscription. The lovely coast of Normandy, with its steep cliffs and cathedral-like caves, is the scene of the story, and the Napoleonic campaigns form the background. The scheme of the other tale, “God and the Man,” is somewhat akin to that of Mr. Hall Caine’s “Bondsman.” It deals with two men, who after long years of mutual hatred are thrown together in the Arctic regions, and by mere companionship are driven to forget and forgive one another. There are beautiful Nature pictures in both, drawn rather from a poetic imagination than from Nature’s landscapes, while “The Shadow of the Sword” contains one of the most perfect of love-idylls told in emotional prose, which is certainly as much verse as the best poems of Walt Whitman. _____ We have called Mr. Buchanan a poet even in his novels. He is also too often a melodramatist. His books depend for their merit upon the nature of his subject. Should he, for instance, select a threadbare plot, then all the distinction of style and beauty of metaphor cannot hide the poverty of his material. Mr. Buchanan, indeed, is not a keen student of the realities of modern life, and he prefers to roam in the world of romance, where there is more of event and less of character. Perhaps that explains the comparative non-success which has generally attended his endeavours to write a modern novel. The most interesting of his experiments in that direction, alike from its main topic and the stir it created, is “Foxglove Manor,” a study of a super-sensuous temperament—in this case a clergyman. Its aim was to prove the close connection that often subsists between intense religious fervour and sensuality. Yet though the central figure is a cleric who disgraces his cloth by impurity, and the scene is laid in an English village with a squire, his lovely wife, and a pretty girl organist, there is a touch of unreality about the whole. Quite apart from the incredible scenes which lead up to the dénouement, imagination seems to have been much harder at work in the story than observation. The characters are not invested with sufficient individuality to be anything more than mere types. Santley is too arrant a self-deceiver for a clergyman, and Haldane is the agnostic of melodrama, while of the two women one is an impossible combination of purity and weakness, and the other is an example of passionate womanhood, which, nevertheless, hardly descends from the abstract regions of the ideal. And this weakness comes out all the more strongly when we take a character like “Daddy” and contrast it with the genuine country clowns of Mr. Hardy. It exactly represents the conventional notions about a rustic, and is as much a creature of the imagination as the yokels of Mr. Meredith’s fancy. _____ The mention of Mr. Hardy’s name calls to mind the book in which Mr. Buchanan consciously imitated the novelist of Wessex, and which he gracefully dedicated to him. “Come Live With Me and Be My Love,” is a very charming piece of work, and contains a good root-idea powerfully worked out; but it only illustrates the point already insisted on. It is a sensational romance, and it is a mere accident that its scenes are laid among the picturesque folk of Dorsetshire. There is a lack of that intimate knowledge of the people and that oneness with the spirit of the country that suggests Mr. Hardy’s lovely mezzotints. Gaffer Kingsley, indeed, is one of the most unmitigated villains ever conceived—as melodramatic a sketch as the husband in Mr. Buchanan’s latest novel “Woman and the Man.” It is curious, and at the same time significant, that both these books should be elaborations of earlier-written plays. They bear evident traces of their transformation. For they consist of a series of sensational incidents strung together by means of clever writing, while the plot of the last, which turns upon the return of a supposed dead husband, is as old as the hills. All Mr. Buchanan’s work has evidence of this passion for the startling and the eventful; and in two instances, thanks to grand themes, he has risen to tragic heights. His other novels—“Matt,” “Annan Water,” and the rest—fall below the sublime, and stand upon the plane of literary melodrama. Perhaps a sure sign of the quality of these last is to be found in the weakness of his dramas save when his poetic gifts can be called into requisition, as in that charming phantasy, “The Bride of Love.” _____ It is not a pleasure to hunt for blemishes in the work of one who will be recognised hereafter as one of the chief figures in nineteenth century literature, but it has been necessary in order to account for the remarkable unevenness of Mr. Buchanan’s muse. We return with delight to the contemplation of his strange personality, evidenced as plainly in his novels as in his poems and essays. Confessedly a Neo-Pagan, he towers far above professing Christians in the loftiness of his moral stature and in the frankness with which he expresses his convictions. He is no Christian, yet he hates war and has a genuine horror of its iniquities. His eloquent pleading for the Magdalen may have provoked the scorn of the inept, but its noble manliness puts to shame the worldly indifference and blatant Cockneyism of our younger writers. In his furious attacks upon sacerdotal tyranny and the ceremonial shams of a sensuous religion he has done Christianity itself a service. Many may not be able to approve the vehemence with which he has assailed the pessimistic realism of the time, but we can only respect his intolerance of the studies of lust so frequent among latter-day Décadents. We must admire also his gallant endeavours to free the world from that literary parasite—the log-rolling critic—and to rid literature of the professionalism which too often animates its devotees. Mr. Buchanan is hardly loved; but then, that is the fate of prophets, and a prophet Mr. Buchanan undoubtedly is—almost as much so as Carlyle or Ruskin. Did he but forswear the degrading influence of the drama, he might win as high a position as a novelist as he has already attained among contemporary poets by his magnificent verse. _____

The Era (20 January, 1894 - p.11) PLAYERS OF THE PERIOD. MR. ROBERT BUCHANAN. Mr Robert Buchanan, the author of The Charlatan, produced at the Haymarket Theatre on Thursday night, has been before the public in the capacity of a dramatist some fifteen years. For Mrs Kendal he wrote a literary trifle entitled A Madcap Prince; and for Miss Neilson he wrote A Nine Days Queen, which it was reserved for Miss Harriet Jay to produce at a Gaiety matinée on Jan. 22d, 1880. To this period belongs St. Abe and His Seven Wives, a Mormon melodrama. At Brighton, on May 9th, 1881, The Shadow of the Sword, a romantic drama, in five acts, was produced, and eventually found its way to the Olympic on April 8th, 1882. Also on April 8th Lucy Brandon, a drama, in four acts, was tried at a morning performance at the Imperial Theatre. On Jan. 14th, 1883, Stormbeaten was produced at the Adelphi. On April 11th Miss Ada Cavendish produced Lady Clare, founded on “Le Maitre des Forges,” at a morning performance at the Globe, subsequently taking the piece on tour. With Sir Augustus Harris Mr Buchanan collaborated in writing A Sailor and His Lass, a melodrama, produced at Drury-lane on Oct. 1st, 1883. On Nov. 2d, 1885, Alone in London was produced at the Olympic. Mr Buchanan took a new departure with the production of Sophia, “founded on incidents in Fielding’s novel ‘Tom Jones,’” and produced at the Vaudeville on April 12th, 1886. On April 9th, 1887, A Dark Night’s Bridal, a poetical comedy, founded on a prose sketch by Mr R. L. Stevenson, was produced at the Vaudeville. The Blue Bells of Scotland, a melodrama, was produced at the Novelty on Sept. 12th, and on the afternoon of Oct. 6th Fascination, an “impossible comedy,” was played, tentatively. Daudet’s novel “Fromont jeune et Risler ainé” furnished Mr Buchanan with the material for Partners, produced at the Haymarket on Jan. 5th, 1888. On Jan. 19th Fascination was put in the evening bill at the Vaudeville. Again Mr Buchanan went to Fielding for Joseph’s Sweetheart, produced at the Vaudeville on March 8th. Foote’s “Devil on Two Sticks” furnished him with the suggestion of That Dr. Cupid, produced at the Vaudeville on the afternoon of Jan. 14th, 1889, and put into the evening bill a few days later. The Old Home, a comedy-drama, was produced at the Vaudeville on June 19th, at a morning performance, and transferred to the evening bill two days later. A Man’s Shadow, founded on Roger La Honte, was produced at the Haymarket on Sept. 12th, having been previously performed, for copyright purposes, at the Elephant and Castle. On Dec. 19th Man and the Woman was played at the Criterion, at a matinée. In 1890 no fewer than eight plays bearing Mr Buchanan’s name were produced. Clarissa, founded on Richardson’s novel, was tried at a morning performance at the Vaudeville, and immediately afterwards became the evening attraction. On March 20th Miss Tomboy, a revised version of Vanbrugh’s Relapse, was tried at a matinée at the Vaudeville, but it was some time before the piece was played in the evening. On May 5th Mr Buchanan’s adaptation of Theodora was produced at the Princess’s. On May 21st, at a morning performance at the Adelphi, The Bride of Love, a poetic drama, was tentatively produced, and subsequently had a brief run at the Lyric Theatre, where, on July 12th, Sweet Nancy was produced. For the Adelphi Mr Buchanan helped Mr Sims to write The English Rose, produced on Aug. 2d; and for the Avenue Theatre he adapted The Struggle for Life, produced on Sept. 25th. The Sixth Commandment was played at the Shaftesbury on the afternoon of Oct. 8th, 1890. On April 8th, 1891, Marmion, a poetic drama founded on Scott’s poem, was produced at the Theatre Royal, Glasgow. The Gifted Lady, a skit on Ibsen, began a brief career at the Avenue on June 2d. Aug. 1st found Mr Buchanan and Mr Sims again in possession of the Adelphi with The Trumpet Call. On April 23d, 1892, The White Rose, by Mr Buchanan and Mr Sims, was produced at the Adelphi, and on the following July 30th the same authors’ Lights of Home replaced it. Mr Sims and Mr Buchanan once more collaborated in The Black Domino, produced at the Adelphi on April 1st, 1893. _____

The Dundee Advertiser (24 February, 1896 - p.7) ROBERT BUCHANAN. When a man has the misfortune to be born with the fighting instinct, whether he be a Chippewa Indian or a cultured Briton, whether his weapon be the pen or the sword, he must make up his mind to endure hard knocks as well as to give deadly blows. No amount of civilisation or School Board cramming will drive this fatal quality out of him. The combative propensity has been the main characteristic of Robert Buchanan, and has exercised a potent influence, now beneficent and anon maleficent, upon the whole of his career. He began his struggle first with poverty, and when he had vanquished that foe he dashed into fierce contests with literary rivals, and, though sometimes defeated, he has been often victorious. HIS FIRST VOLUME —“Undertones,” a miscellaneous collection of poems, prefaced by memorial verses addressed to Gray, and entitled “To David in Heaven.” This maiden effort saw the light towards the close of 1860, and had a fair measure of success; but in those days “the grass of Parnassus” afforded little sustenance to the aspiring poet, and butcher’s bills cannot be settled by poetic fame. Nevertheless, Buchanan’s reputation as a “slinger of verses” gained for him an entrance to some of the magazines, and he managed to eke out an existence by manufacturing attractive “pot-boilers.” In 1865 he published his “Idylls and Legends of Inverburn,” a series of poems and ballads so strikingly original that they attracted much attention. But in those days the interest in literature with a Scottish flavour was not so great as it now is; nor was the voice of the log-roller heard in the land. Buchanan speedily learned that to gain the Cockney ear he must write of affairs that happened within the sound of “the great bell of Bow,” and accordingly, with a commercial instinct seldom found in the mere moon-struck poet, he set himself to produce his “London Poems,” a series sufficiently parochial to charm the metropolitan mind. The poet’s anticipations were fully realised. He might have piped divinely about Scotland without touching the heart of the Londoners; but when he sang of slum-life in the purlieus of the metropolis he was at once hailed as a marvel. A critic of the period has said “The humble life of the great city has rarely been so vividly, so humorously, and so pathetically delineated as in these poems.” They were the legitimate ancestors of John Davidson’s “Fleet Street Eclogues,” though the present generation has almost forgotten them. His fertility at this time became immense. Volume after volume came from his pen—“Danish Ballads” and “Wayside Poems” prepared the way for his lyrical drama entitled “Napoleon Fallen,” which was published in 1871. His contributions to periodical literature were voluminous and varied, and a selection of prose essays was published about this time under the title of “The Land of Lorne.” For a brief period he attained notoriety by his article upon D. G. Rossetti in the Contemporary Review entitled “THE FLESHLY SCHOOL OF POETRY.” in which he denounced the mawkish, erotic sentimentality which had been made fashionable by a few dyspeptic poets. A fierce controversy arose, and the combativeness of Robert Buchanan had full play. Taking advantage of the publicity he had gained, he started a new monthly magazine called “Light,” but it was speedily extinguished, and the world was left in what Pope calls its “native night.” Changing the form of his literature, Buchanan now became a novelist. In 1880 he published in the People’s Friend a novel entitled “The Tryst of Arranmore,” and followed it next year with “The Martyrdom of Madeline,” issued as a serial in the same periodical. His other principal novels have been “The Shadow of the Sword,” “God and the Man,” “The New Abelard,” and “Foxglove Manor.” In some of these he trod very closely upon the heels of the “fleshly” poets, whom he had so bitterly decried. He next sought fame as a dramatist, and several of his plays have been decided successes. Amongst these are “A Nine Days’ Queen,” “Lady Clare,” “Storm-Beaten,” “Sophia,” and “Joseph’s Sweetheart,” besides several very popular dramas brought out in collaboration with George R. Sims. His dramas were so skilfully written and contrived that they were as suitable for the study as for the stage. The footlights, however, were not wholly to fascinate him, for he still clung to verse, and in 1888 published his remarkable poem, “The City of Dream,” one of the most weird and enthralling works of recent times. A strange occult romance was published in the following year called “The Moment After,” detailing the experiences of Maurizio Modena after life had become extinct. In 1891 Mr Heinemann published a volume of essays by Buchanan called “The Coming Terror,” in which the author mercilessly lashed the follies of the age with the whip of a Triboulet and the stinging satire of a Swift. By this time he had become THOROUGHLY PESSIMISTIC, and he scourged the frivolities and vices of our time with an unsparing hand. His language is often indiscreet, but always vigorous, and the public, like the Flagellants of old, rather enjoys a good thrashing; for every member may suppose that the blows are meant for some other party. Buchanan’s latest eccentricity has been to write a play in defiance of the severe morality of the Lord Chamberlain, or whatever other Lord it may be that looks after the literary decency of the stage. Such has been the romantic career of Robert Buchanan. He began his public life as a runaway. He served his apprenticeship as a literary skirmisher. He sang now of Scotland, with empty pockets, and anon of London, with overflowing coffers. He has done much good work, some mediocre stuff, and a little that ought to be blotted from remembrance; yet there are many less creditable foster-children of the old College in St Mungo’s city than Robert Buchanan. _____

The Echo (27 April, 1901 - p.1) ’TWEEN COVERS. (By Our Own Bookworm.) Robert Buchanan! “Bonny fighter,” novelist, publicist, dramatist, and poet. What a congeries of qualities the name conjures up. Truly a knight of the pen if ever there was one. Ever ready for the joust and the tournament, he smoked for the affray, for the lists where sarcasm, satire, and wit were the weapons of offence and defence. His career (for alas! it must be spoken of in the past tense) has been so comet-like, so brilliant and changeful, so errant and evanescent that it has never had time to impress itself as anything uncommon or extraordinary on our somewhat obtuse and impervious intelligences. But here was a fine and a rare genius, clouded indeed to our view by aberrations perverting to our vision, although comforting to our baser metal that genius is after all like unto other men except in its genius. It is, however, less humiliating to him than to us that his imperfections have partially blinded us to the unalloyed excellence of his work. _____ If greatness is to be measured by the hostility of other men, then assuredly Robert Buchanan is one of our most heroic figures. Even in his novels and dramas he has not been able to lay aside his love of fire-eating. In his political, social, and religious essays he has thrust us in our most cherished beliefs, and over-toppled the idols we have most idolised. But it is in his poetry that we find his true self, the revelation of the spirit of “the poet of modern revolt.” It is in this light that Mr. Buchanan’s poetry has to be considered if we are to find his true significance, and we are therefore grateful to Mr. Stodart-Walker for the fine judicious discrimination and judgment he displays in his estimate (Grant Richards) of the poetical attainments of one who must undoubtedly be placed in the front rank of modern poets. Mr. Walker wisely believes that in viewing Mr. Buchanan as a poet he is concerning himself with the Buchanan that is of importance in contemporary literary aspirations. _____ What was Robert Buchanan’s mental attitude? An attitude of revolt against accepted traditions, of opposition to conventional formula. He could never bring himself to believe that the opinion of the majority was necessarily right. It was thus he set himself against the national idols, the Church, our political and ethical nostrums. The impostor who had foisted himself into high position was his especial object of attack. In his own picturesque and forcible language he said, “I’ve popt at vultures circling skyward, I’ve made the carrion hawks a byeword, but never caused a sigh or sob in the breast of a mavis or cock robin.” In another place he says, “My errors have arisen from excess of human sympathy, from ardour of human activity.” Indeed, it was this excess of human sympathy for the downtrodden and the helpless that raised in him the spirit of revolt. _____ His song is always for the poor and the distressed, of “The Little Milliner” and her lover, the poor clerk, of Liz, whose “all I want is sleep, under the flags and stones,” and the dreamy labourer, Who toiled away, and did his best It was said of him by a supercilious critic, who meant it unkindly, that his idylls were of the gallows and the gutter, of costermongers and their trulls. Such an impeachment would be rather out of date if brought forward now. But Mr. Buchanan could write of other things when he chose. Some of his poems, as, for instance, “To Galatea,” have an almost Ovidian lusciousness and voluptuousness. Others again have a Byronic gloominess and mysticism. For poetic idealism and for a sympathetic and reverential treatment of a subject for which he was not commonly reputed to have much reverence, his ballad of “Mary the Mother” stands alone and unrivalled. While the hostility and enmity aroused by his strenuously expressed opinions continue to exist we can hardly hope that his work will receive the consideration it deserves. But with the rise of a new generation it may be confidently hoped that he will be assigned his proper place. D. M. S. ____________

Back to Buchanan and the Press

|

|

|

|

|

|

|