|

Essays - ‘The Newest Thing In Journalism’

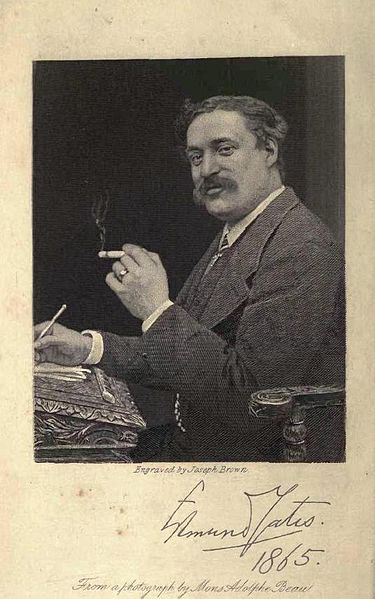

Towards the end of 1877 The Contemporary Review published two anonymous articles under the heading ‘Signs of the Times’. The first of these, ‘The Newest Thing In Journalism’, attacked the new ‘society journals’ such as The World, edited by Edmund Yates. Although the Contemporary article was anonymous, Yates believed that Buchanan was the author and printed a stinging reply in The World on 26th September under the title, ‘A Scrofulous Scotch Poet’. The second article in The Contemporary Review appeared in November and was an attack on the current popularity of French farces. This article concluded with a note which contained a letter from Buchanan responding to Yates’ attack, although there was no clear admission that he had written ‘The Newest Thing In Journalism’. Neither of these anonymous articles were reprinted in Buchanan’s later volumes of essays, but Buchanan did own up to his authorship in a letter to The Era in October, 1883 and in an interview with the New York Daily Tribune in September, 1884.

In his 1882 novel, The Martyrdom of Madeline, Buchanan satirised the ‘society journals’ again: Henry Labouchere of Truth became Hubert Lagardère of the Plain Speaker and Edmund Yates of The World became Edgar Yahoo of the Whirligig.

‘What, don’t you know him? That’s Lagardère of the “Plain Speaker.”’

‘Indeed! A journal, I presume?’

‘The journal of the period, based upon the new principle of extenuating nothing and setting down everything in malice. Lagardère can tell you to a nicety where La Perichole buys her false teeth, how much money Mrs. Harkaway Spangle pays her washerwoman weekly, and when any given leader of society is likely to pawn her diamonds or elope with her cook. You know Tennyson’s lines—

A lie which is all a lie can be met with and fought with outright,

But a lie which is half a truth is a harder matter to fight!

Lagardère has achieved the complete art of so mingling truth and falsehood together that it is impossible even for himself to distinguish the one from the other. What wine will you take?’

(From The Martyrdom of Madeline, p. 116-117.)

‘Edgar Yahoo, the last descendant of the race of the Yahoos, for the history of which see Swift’s “Gulliver”; the only difference being that this Yahoo no longer waits upon the nobler animal, but delights in airing himself upon its back.’

‘Explain!’

‘Yahoo lays claim to be the founder of the new system of journalism. From childhood upward he has aspired to be the social chiffonnier of his age. He rakes for garbage in the filth of the street and in the sewers. Don’t you remember the verses MacAlpine wrote about him?

Who prances on through Rotten Row

Upon his golden-footed bay?

Who prances, ambles, to and fro,

Always gay?

Who canters back along Mayfair,

Spreading foul odours on the air,

While all draw back to cry ‘Beware!

The Scavenger of Society!’

(From The Martyrdom of Madeline, p. 217.)

The Martyrdom of Madeline is available at the Internet Archive, and reviews of the novel (some of which note Buchanan’s veiled attack on Yates and Labouchere) are available here.

In April, 1884, Edmund Yates was sentenced to four months in prison for libel. Buchanan wrote a letter to The Pall Mall Gazette, in support of Yates, which concluded:

“This sending of journalists to prison is at the very best a barbarous business, and unworthy of the civilization under which we live.”

Which might possibly explain Yates amending his account of their first meeting in his memoirs, published that same year:

“... and there were contributions from two acknowledged poets, whose acquaintance I had recently made. One was Mortimer Collins, of whom I had heard frequently . . . The other was by Mr. Robert Buchanan, who came to my house in the Abbey Road, to which I had just removed, one evening in November, with a letter of introduction from W. H. Wills, who had previously spoken to me about him. Mr. Buchanan had recently arrived from Scotland to seek his fortune in London, and had greatly impressed Mr. Wills, not merely by his undoubted talents, but by the earnestness and gravity of his demeanour. He wrote a series of poems in our new magazine, the first one having ‘Temple Bar’ for its subject, and became a constant contributor.”

(From: Edmund Yates: his Recollections and Experiences. Volume II. (London: Richard Bentley and Son, 1884. pp. 59-61.)

And a final note of conciliation, recalled by Henry Murray, in his essay on Buchanan published after his friend’s death.

“It may interest the reader, and may serve as a further illustration of the real kindliness of personal feeling which underlay Buchanan’s occasional virulence of attack, to read the brief address to two of his oldest and most persistent opponents, the late Edmund Yates and the living Henry Labouchere, which was, by a mere accident, left out of its proper place in the first—and at present, only—volume of ‘The Outcast.’

So, Edward, Henry, pax vobiscum,

Arcades ambo, here’s adieu!

All strife, all hate, at last to this come—

The silent grave, the sunless yew.

The scandal-monger, the truth-seeker,

The man of this world or a fairer,

Must drink at last of the same beaker,

Whereof a skeleton is bearer.

A little space a little life,

A little time a little strife,

Then calm, then rest, then slumber deep,

’Mid the black brotherhood of sleep.

As Rome was once, when on the Tree

Bloom’d the blood-rose of Calvary,

So is our England now, and you

Perform your parts like Romans true.

Afoot or horse-back, proud or prone,

Continue beautiful and brave,

And take a smile, and not a stone,

From him who walketh all alone

The common highway to the grave.”

(From Robert Buchanan: A Critical Appreciation And Other Essays by Henry Murray (Philip Wellby, 1901.)

___

In the following sequence, ‘The Newest Thing in Journalism’ is followed by some Press speculation about the authorship of the article, then Edmund Yates’ response, ‘A Scrofulous Scotch Poet’. I have not seen the original copy of this, published in The World on 26th September, 1877, but I did come across an article from a New Zealand paper, which reprinted Yates’ reply in full, so this is the version I’ve used. After this, there are some other items from various papers concerning the dispute, and then the second ‘Signs of the Times’ article from The Contemporary Review, which concludes with the ‘Editor’s’ comments on the first article.

_____

From The Contemporary Review - September, 1877 - Vol. 30, pp. 678-703.

SIGNS OF THE TIMES.

I.—THE NEWEST THING IN JOURNALISM.

“Tho’ these be trifles light as straws,

They show what wind is blowing!” —OLD BALLAD.

IN one of the charming and, in the truest sense, learned novels of Mr. R. D. Blackmore, is to be found a foot-note containing the oracular utterance of a certain Devonshire farmer who, being urged to study the newspapers, sharply retorted, “Whatt be the gude of the papper, whan any vule can read un?”—or in other words, what is the good of learning news with which everybody is acquainted? Humoursome as this conception is, there is something from more than one point of view to be said in its favour. Our public journals—good, bad, and indifferent—are really far too easy reading, and lack that air of novelty and mystery which in former days rendered them more or less oracular. What they contain may be ascertained by anybody, and, being ascertained, is hardly worth knowing. Expressed in a secret hieroglyphic, or couched in a mystical language, incomprehensible to the uninitiated, a newspaper might speak with authority to those who, like the Devonshire farmer, like to sweeten gossip with secrecy, and keep the sugar-plums of scandal to themselves or to their own circle. Things being as they are, it is scarcely worth while to study the “papper,” and he is perhaps a wise man who indulges in that sort of literature as little as possible. The newspapers are too much with us. What was once a delightful luxury is fast becoming an unmitigated bore. To parody the words of Aristophanes, “instead of Jupiter a whirlwind reigns”—instead of the Times, we have oracles innumerable. Scarcely anything is too ignoble not to find its way into print in some shape or other—so that “any vule can read un.” It is not only the big battles, and the great debates, and the buying and selling, and the robbing and murdering, 679 and the dancing and playing, that are dinned into our ears from morning to night at second-hand; the smallest of beer, nay the very washings of the barrel, is solemnly chronicled, diluted in the veriest verbiage of the penny-a-liner. “Enter Rumour, painted full of tongues”—his dress the patchwork of a million journals, from the Daily Telegraph to the Matrimonial News. Fly to what corner of the earth we will, we cannot escape them. Frankenstein-like, we are pursued by the monsters we have created; and even in the solitariest corner of the North Cape, with nothing but grey heaven above us and the solemn Arctic Ocean murmuring at our feet, we are certain to be reached in one form or another by the folly which we do not wish to remember and the news which we do not wish to hear.

Despite this pest of journalism, to which the pest of locusts was a trifle, we can fearlessly aver (though we fear upon incomplete knowledge, for who can profess to have positively numbered and examined every one of these “flyers of the public air?”) that we know not where to put our hand upon more than two or three newspapers such as honest men may read in patience and in some sort of endurance, if not of comfort. If we are to have news at all, if we must perforce be acquainted with what “every vule can read,” we would fain have it in the handiest and most concentrated form procurable—shorn of the graces of Jenkins and his tribe, put forth in naked English, clean and unashamed; and above all, within limits truthful and reliable. Tittle-tattle we desire not—yet three-fourths of most newspapers, nay one-half of the very advertisements, is mere tittle-tattle. Hungry as some of us are for facts, we do not care to be worried with “opinions;” yet, strange to say, the newspapers are nearly all “opinions”—which mankind devour wholesale, and incontinently pay for in coin of the realm; forgetting altogether that they might gather better “opinions” gratis at any street-corner, or in any bar-parlour, or on the top of any omnibus, city or suburban. So the penny-a-liner thrives, and his thrift is to make much of little, that the craving of “vules” may be satisfied and his own stomach be lined. So there spring into existence innumerable varieties of the penny-a-liner pure and simple, as out of the common “rock” are developed the innumerable varieties—or monstrosities—of the pigeon; and out of this development, in lieu of “pouters,” and “tumblers,” and “ fantails,” and “splayfoots,” we get the incontinent editor, the roving correspondent, the leader-writer, facetious or solemn, the unwashed critic, literary and dramatic, with other horrid literary anomalies too numerous to mention.

Things being in this condition, it would certainly have occurred to any reasonable being, taking a quiet survey some years ago of the boundless realms of journalism, that there scarcely remained a 680 nook or cranny where a new-comer, however energetic or however able, might find a place to rest its feet—unless indeed it made the attempt, always desperate but sometimes successful, to elbow some established favourite aside, and after a desperate struggle take its place. It seemed clear enough that all needs were satisfied, that every taste was represented. There were the big dailies, from the Times downwards— weathercocks, most of them, to show how the wind of public opinion blew; and if this were not enough there were class dailies too, more particularly for the commercial and sporting worlds. In every county, in every town, one might almost say in every street, there were newspapers, each settling the affairs of our globe from the point of view of its own particular vestry. In a word, the market was overstocked; of “pappers” there was no end, and the educated world certainly wanted no more of them. It was not that they were good, it was not that they were tolerable, but—there they were! Attempts to supplant them were generally suicidal; and though not a few of them were fogies utterly behind the age, antique and ghostly creatures carrying the dress of Count d’Orsay and the drawl of Beau Brummel into a jeering and a later generation, still they were tolerated for all that they had been to our grandfathers, and they clung to their perches as fiercely—ay, and now and then crew as loudly—as younger birds of a stronger wing and a finer feather.

To the eye of an ordinary being, then, it would have clearly appeared that the market was overstocked, that to undertake the incubation of a new journal would be a waste of capital, and, in so far as brains are concerned in such matters, perhaps of brains. It was no ordinary being, however, but a genius of insight almost superhuman, certainly superordinary, who, darting his eagle glance into the waste of letters, said to himself, “After all there is nothing here but chaos—a world certainly, but shapeless and unorganized; out of this chaos order shall come, and the newest, truest, and sweetest thing in journalism be evolved.” Pursuing his examination further, this gifted being proceeded in dark soliloquy, “Yes, there is little to be seen here but wasted space and wasted opportunities. These newspapers, in their attempts at the infinitely great, have altogether overlooked the infinitely little. They are bought, they are devoured, but their appeal is to the gourmand not to the gourmet,—to the cormorant in news, not to the epicure in scandal. If we divide a man into three portions, two at least of these portions are unutterably and mendaciously mean; in a word, each member of society, however he may attempt to disguise the fact, is a SNOB au fond—a Snob not in the false sense adopted by modern society and applied by it even to Mr. Gladstone, but a Snob in the sense used, with a power of dissection 681 almost microscopic, by the late Mr. Thackeray.* Now, in the chaos before me, the Snob is appealed to on every side indirectly; directly and openly he is not appealed to at all, and he has to search through weary and dreary columns of irrelevant matter, he has to grope darkly and with wailing and gnashing of teeth through labyrinths of editorial circumlocution and ingenuity for the sugar-plum that he loves and which he knows is wrapt up somewhere in the paper. Every paper has this sugar-plum somewhere, to be hunted out diligently by the Snob clerical, or political, or artistic, or commercial, or dramatic; but no paper within my vision makes its direct appeal to the snobbish nature pure and simple. Thus, amid the multitude of journals, there is room for at least one other, and that other I will found.” Then began the inevitable search for a capitalist, who in due course was discovered. The word of a new prophet went forth, and the era of the newest thing in journalism began.

It would need the pen of a new Lucretius to describe how from these dark and remote beginnings the first new sphere of incandescent journalism issued over the divine limits of light. But one morning, there arose before the gaze of wondering humanity a publication with this inscription—

“We buy the Truth.—Pilgrim’s Progress.”

But alas! this publication, although it was christened Vanity Fair, and thus sheltered itself under the shields of two great Englishmen, had as little in it of the humour of Bunyan as of the satire of Thackeray, but was saturated through and through, from title to last page, with the vulgarity of the “Snob” and the tattle of Mrs. Love-the-flesh, Mrs. Inconsiderate, Mrs. Lightmind, and Mrs. Knownothing. Just as in a booth at a fair a coarsely devised picture is paraded to attract the attention of passers-by, so on the face of the new journal was paraded a coloured caricature, villanously unlike anything in nature, of (mirabile dictu) a “leader of society;” and in every subsequent number up to the present date (for the thing actually lives to this hour) has been issued a caricature, more or less hideous, of some individual famous or infamous enough to be parodied in his habit as he lives. A certain amount of cleverness cannot be denied to these pictures, but, considered as a series, they have the same effect, in their utter baseness and repulsiveness, as a visit to the monkey- house of the Zoological Gardens. To works of real humour and caricature they bear the same relation that what is known as a mock-valentine does to a

_____

* “What is Thackeray’s definition of a Snob?” asks a recent contributor to Truth. “One who meanly admires mean things; one who is pretending to be what he is not, one who is a tuft-hunter, a worshipper of rank, fashion, and mammon; one who is a toady, a lick-spittle, and a sufferer from false shame.” With a few necessary additions, which will occur to every reader, this definition may be accepted for our present purpose, and, being epitomized by an adept, may be accepted as in every way authoritative.

_____

682 genuine Hogarth or Cruikshank. Seizing upon some remote monstrosity of the subject, and exaggerating that monstrosity into unnatural and meaningless prominence, they are libels at once on art and nature— almost as degrading to the spectator as to the artist who wasted his gifts on their production. Such being the outside of the show, such being the brilliant lure to attract attention and draw in audiences, what was the performance to be found within?—what, in other words, and again to quote the title-page, were the “political, social, and literary wares” offered in this new Fair of Vanity? A little tenth-rate fiction, a few notes on passing events, one or two flashy articles, and a large sugar-plum of indecent suggestion and pitiable scandal. Without one gleam of wit and fancy, without one fragment of ordinary culture, without literary skill, and without common instruction, this journal for the vulgar-genteel produced the tittle-tattle gathered in the backstairs of great houses, in the clerks’ offices of the City, at the refreshment bar of the House of Commons, in the housekeeper’s room, in the taverns patronized by Jeames. The lure was bright, and the “young man of the name of Guppy” was hooked at the first cast. For a few pence, Mr. Guppy was introduced to the first society; to look on the counterfeit presentments of the “haristocracy” was almost as good as meeting the originals in the flesh; and nothing could excel Mr. Guppy’s delight on being taken, as it were, by the button-hole and regaled with the choicest morsels of social gossip. “And by jingo, sir,” quoth Mr. Guppy, to his friends, “it’s pleasant to think that all these igh chaps have their little weaknesses like one’s self.” Conceive Mr. Guppy, with the handle of his cane thrust into his mouth, and little vulgar eyes twinkling with wickedness and “knowingness,” reading the following about Viscount Cole:—

“Blessed with good looks, even temper, and a determination to make the best of this world,* he became a rifleman at twenty, and, being soon found to be an exquisite dancer, he pursued a successful social and military career of three years’ duration. Having, however, discovered the charms of domestic felicity, he early retired upon his laurels. He made a brilliant marriage and unmade a famous one; and now at two-and-thirty he is still a favourite partner at any ball he may please to honour.”

Or this, about an equally interesting individual, “Viscount Newry and Mowrie:”—

“As the recipient of many confidences, he is generally considered a safe man, and one whose opinion, bluntly given, though kindly meant, is worth having. It is said that a few women have loved, and consequently many men hated him—still he manages to exist pretty comfortably.”

Nor would the young man of the name of Guppy peruse with

_____

* The italics, in nearly all our quotations, are our own.

_____

683 much less delight the following concerning an elderly man of the name of Lawson:—

“As yet without any public reputation, he (Mr. Lionel Lawson) is nevertheless well-known in all joyous resorts, and has a considerable acquaintance among public men and women. A steady frequenter of the theatre and of the later places of amusement, he has conferred many benefits upon many persons, and being open-handed has had many of those private successes which stamp a man as being received by the fair sex for one of face and figure. The date of his birth it is unnecessary to mention, since he still cherishes the fond delusion that he is thirty-five. A life of ease is that which he most prefers.”

It would be superfluous to speculate concerning the influence of such reading on the mind of our hypothetical Mr. Guppy, and to ask whether it might not sooner or later tempt him, in his vaulting and overreaching social ambition, to take liberties with his employer’s petty cash. He, too, like other men of mark, from Mr. “Lionel Lawson” down to Mr. “William Sikes,” undoubtedly prefers a “life of ease;” he too would fain frequent the “later places of amusement” and be “received by the fair sex for one of face and figure;” and though his “private successes” might leave sore hearts in Islington or Dalston rather than in South Kensington or Belgravia, the moral crime would be all the same. Determined, like Viscount Cole, to “make the best of this world,” and seeing how sweet an example his betters set him, he too might try to “unmake a marriage,” carrying desolation into the bosom of some fellow-clerk’s home at Isleworth; and he too would fain, like Lord Newry, be considered a “safe man,” loved by a “few women” and hated by “many men.” In view, doubtless, of such social ambition on the part of Mr. Guppy, the conductors of the new Vanity Fair deemed it expedient to offer a set of valuable suggestions for his guidance in matters of social delicacy. A number of hypothetical “Hard Cases” were put—one at least each week—and readers were invited to contribute their opinions how to act under certain circumstances. If, for example, Mr. Guppy is invited to a country house, and having sat up rather late goes by mistake into the wrong bedroom, where a friend’s wife is lying, and if at that moment the lady wakes and the lady’s husband is heard approaching the door, Mr. Guppy would like to know what to do? Such a very common occurrence would demand presence of mind! “If the lady does not squeal,” elegantly writes one correspondent, “the gentleman should quietly get under the bed and wait till the husband goes to sleep, and then steal quietly away, and try not to look a fool at breakfast.” “The gentleman,” suggests a correspondent of more daring ideas, “should blow out the light and bolt the door!”

The anomalies of English life and law are wonderful indeed! While poor Joe Nameless is dragged to the lock-up for playing a 684 harmless game of pitch-and-toss, while ragged Belphegor the mountebank is forbidden to tempt clodhoppers with a wheel of fortune, parties of police are told off to keep the ring select and quiet at Epsom; and while vulgar “Fruits of Philosophy” and “Priests in Absolution” are seized and confiscated, the genteel journal proceeds week after week on a literary system of indecent exposure. It is difficult indeed to decide what is and what is not amenable to the law on the score of impropriety; but we have no hesitation in saying, in round unvarnished terms, that there is more absolute evil between the leaves of the journal called Vanity Fair than in either of the books which have recently occasioned public scandal, and this the more certainly because the vulgar-genteel journal deals less in plain statement than in secret inference, more in sly, diabolical suggestion than in bold, unvarnished indecency. We can conceive no man of ordinary culture or of common delicacy perusing these so-called “Hard Cases” without abomination and loathing. What Mr. Guppy, what the legion of Guppies who constitute the genus Snob, think of them, is another matter. They comfort the soul of Guppy. They convince him that English society is as mean, as indecent, as ignorant, as foul-minded, as he would fain believe it. They reveal to him, as in a grotesque mirror, his own little physiognomy, his own debased morality, contorted and distorted. He discovers, with a chuckle, that Lord A. and Lady B. have the same nasty ideas as himself. The blood of the Snob tingles through his frame, and he yearns to go and act likewise, for surely the “leaders of society” can do no wrong.

To make our point clear, to show as succinctly as possible the sort of ware which this so-called “literary, political, and social” journal provides for its readers, we are constrained—though not without an apology for such a parade of sheer imbecility—to give one “Hard Case” in full:—

“HARD CASES.

“HARD CASE No. 60.—IN ONE INCIDENT.

“Mr. A M. and Lady D. N. are staying with other guests at a country house in the South of England. During a dance which is given one evening, Mr. A. M., under false pretences, inveigles Lady D. N. (whose husband is absent) under a bunch of mistletoe and embraces her.

“What should Lady D. N. do?

“Answers adjudged correct:—

“a. Considering Mr. A. M.’s great age, Lady D. N. should take no notice of Mr. A. M.’s conduct beyond expressing her opinion on it to him.—X.

“b. Lady D. N. should pass it off as a joke, and smilingly say, ‘Thank you.’ N.B.—The only annoying thing in the affair would be the publicity, coupled with the invidious remarks of envious lookers-on, who would of course ‘conclude that Mr. A. M. would not have 685 ventured on such a prononcé act in public without more than an average amount of encouragement in private.’—B.C. mais T.C., We Three, Poodle.

“c. Rebuke Mr. A. M. (sincerely or otherwise), and say nothing further about the little incident.—Delta.

“d. Supposing Lady D. N. to be just a shade off the square, she may be almost as much to blame as Mr. A. M. for the unfortunate contretemps; but presuming her to have given no provocation, she will wisely avoid a scene, but at the same time exhibit her indignation with withering effect, leaving her husband to put Mr. A. M. through his facings in due course.—La Favorita.

“e. Withdraw from under the mistletoe, and inform Mr. A. M. audibly that in future she shall consider him as only a bowing acquaintance, since he does not conform to the ordinary customs of Society.—Burncoose, Cœlebs.

“f. If unobserved, to content herself with saying, ‘Oh, you naughty man! I’m surprised at you!’ If observed, to scream and make a scene.—Snakes and Snuffers.

“g. Soundly box his ears.—Johnson, Bessie, Shyrad’s Wife, Lancashire Lad.

“h. Lady D. N. should try and pretend she didn’t like it.—The Great Western.

“i. Scream.—Notodaybaker.

“j. Let Lady A. B. force a laugh, and reply, ‘One twig of mistletoe makes the whole world kiss.’—Naughty Boy.

“k. Lady D. N. should say to Mr. A. M., ‘Dare to presume again, I tell my husband, and either you or I leave the house.’—Gardenia.

“Answers received not adjudged correct:—

“l. Lady D. N., in the absence of her husband, should appeal to the master of the house, and demand an apology from Mr. A. M.—Rusticus, Passion Flower, Magenta.

“m. Take the earliest opportunity of returning the embrace (naturally in a more private and delicate manner), to show Mr. A. M. that she will not be indebted to him for so worthless a Christmas-box so publicly bestowed.— Flossy, Loose Fish, Shyrad.

“n. Frown, till finding out that the transaction was not noticed, or, if noticed, approved of, then change the frown into a smile, and become A. M.’s partner for the remainder of the dance. ‘Do you come here next Christmas?’ would be a pleasing question put to A. M. by his partner.—Lothair Heigh O.

“o. Lady D. N. should keep it to herself.—An Elephant.

“p. ‘Where there’s a will there’s a way;

All’s fair, under mistletoe, at Christmas play.’

—W. J. D., Bremeniensis.

“q. Smite him on one cheek, and receive another kiss.—The Baden Cove.

“r. Make her husband horsewhip Mr. A. M.—T’other Baden Cove.

“s. Telegraph for her husband, and watch the duel amongst the ruins.—A Snubbed Caller, Little Tom Tommy.

“t. Lady D. N. should express her disapproval of Mr. A. M.’s deception, and give him as little of her company as possible in future.—Allout, Punch and Judy, A. J. J., A Bow-wow, Stella.

“u. Prosecute A. M. for assault.—Smike.

“v. Write to her husband for advice.—Annah Mariah, Mistletoe, Vavir.

686 “w. Tell Mr. A. M. she considers he has taken a great liberty, and decline dancing with him any more.—Bellona, Card House.

“x. Lady D. N. should exclaim, ‘Well done, Mr. A. M.; do it again!’—One who has already had that privilege.

“y. Lady D. N. has the privilege of asking Mr. A. M. to repeat the attention, this being leap year.—A Rejected Partner.

“z. Give a sweet, salacious smile, and, her husband being absent, return the gift!—Chinese-Joss-Old Podge (Brighton).

“aa. Lady D. N. should offer the other cheek.—A Once-beloved Object, The Saxon.

“bb. Remain seated under the mistletoe. Tell all the other gentlemen to follow suit.—Gobang.

“cc. Make the best she can of it.—Nosrednehtrebreh, Easter Egg.

“‘Bremeniensis,’ who has answered correctly thirteen Hard Cases out of those published in 1875, is the winner of the prize, and is requested to send an address. The second is ‘J. C. S.,’ who has correctly answered seven.”

We should have thought pap of this sort too nauseous even for the infantine taste of Mr. Guppy. He appears, nevertheless, to like it, and it is also in high request among his female acquaintances. Lest, however, this and similar attractions should fail to procure a circulation for the new thing in journalism, the daring mind of its projector—taking with singular and audacious accuracy the mental measure of his readers—determined to offer prizes to the best answers to these “ Hard Cases.” Not content with this, he devoted a large portion of his space to the species of ingenious puzzle called “acrostics,” and to the cleverest guessers of these also offered small rewards in money ! Now, in the first place, it is difficult to conceive that a rational being, who has any serious work to do in the world, or who has any respectable means of occupying his time, would descend for five minutes to the inane abysses of riddle-guessing, and devote his leisure to working out the most imbecile of all conundrums. Yet so subtly had this new literary projector made his calculations, that no small portion of his success was owing to his making a feature of an amusement absolutely idiotic; and so cleverly had he gauged the public, that no journal of the new style, following in his footsteps from that hour to this, has failed to devote a considerable portion of its space to acrostics, for “guessing” which prizes are invariably offered in money. Perhaps this fact may serve as well as any other to show the intellectual calibre to which the new things in journalism appeal. Lord Dundreary asks “widdles,” and doubtless Mr. Guppy and his female acquaintances enjoy acrostics, single or double. Games of chances and sports of folly have been always popular with the Snob, who never reads a thoughtful book, who never admires a noble deed or lovely picture, whose chief concern is with his tailor and with his belly, who knows nothing, does nothing, believes nothing, who has never seen a flower or a tree, 687 and whose only conception of the sea is connected with Margate or Southend; whose life, in fact, is a “double acrostic” in slipshod verse and crawling metre, of which even the most beneficent of the angels would find it difficult to offer a satisfactory solution.

We are reminded, at this point, of a fact which we had not absolutely forgotten, but were lightly and of set purpose passing over—viz., that much of this Vanity Fair rubbish is clearly written and manufactured, not so much for the Snob male as for the Snob female. Women are beginning to read, for the most part foolish women, and surely some of this trash must be for them,—else why so much of the latest fashions in farthingales, of the doings of Lady This and Miss That, of washy tea-drinkings and gaudy “private theatricals,” of loud-mouthed scandal and whispered imputation? Surely no masculine animal, however alien to Sir Oran Haut-ton or the archetypal ape, could take delight in such silly froth as this—a sample of the sort of news which is offered to a forbearing public every week:—

“When two persons, having arrived at years of discretion, agree together flagrantly to violate the laws, not only of the land, but of common decency, they have thenceforth no hope left but to stand together; and that one of the two—especially if it be the stronger one—who deserts the other is guilty of treachery of an especially heartless kind. Yet this is what has happened. Some time ago a lady whose husband was abroad chose openly to take another to his place, and to establish a new home, if such it could be called, at a retired village in the country. The husband returned, did nothing, and after some fierce passages—not between himself and the Despoiler, but between one of his friends and the Despoiler—accepted the situation. The end, which was early predicted, has now arrived. The Despoiler has suddenly left the unfortunate woman whom he had taken away from her home and her fame to her shame and his ‘protection;’ and she is now left desolate, friendless, ruined, and alone. Surely even the most lax must say that this desertion at least is very base; surely those who most readily predicted, and perhaps most hoped for this, must feel that the vengeance even of the most revengeful is now satisfied. I doubt if we have heard the last of it.”

Observe, this has not even the merit of real names or even initials to make it spicy, and, for all we know, may be a pure invention of the person who records what he calls “vanities.” But would even Mr. Guppy, would anybody but a spinster amid the solitudes of Surbiton, or a fast widow in the agonies of moral hydrophobia, read such gossip with patience? We are compelled, though reluctantly, to believe that Vanity Fair circulates to a great extent among women; and yet even most ballet girls, we believe, would use such rubbish only to curl their hair.

It is time that we quitted Mr. Lechery and Mrs. Love-the-flesh and the other denizens of this new Fair of Vanity. It has been no pleasant task to linger in such company. Turning our back upon the chamber of horrors called “Cartoons of Public Men,” 688 and shutting our ears to the gibbering of the penny-a-liner who echoes and re-echoes the tattle of the Fair, let us pass upon our way. From the twilight of the dismal region we have left, we emerge into dubious sunrise, for a new World arises upon our ken.

In its own ignoble way, by dint of caricatures and double acrostics, Vanity Fair succeeded, and it endures. Fired by a success so easily achieved, and perceiving a field at last in which he might develop energies long misdirected in the production of Braddonian fiction, a gentleman of letters conceived the idea of equalling, nay, even eclipsing, the existing luminary. He took into his confidence two kindred spirits—a newspaper correspondent who surveyed mankind from the reporters’ gallery of the House of Commons, and another newspaper correspondent who had distinguished himself, more or less pugilistically, on the Stock Exchange. “We will begin,” said this distinguished provider of public refreshment, “by ‘cheeking’ everybody, but particularly the Prince of Wales. Let us be nothing if not personal and scandalous. We are neither of us artists of the pencil, and we cannot therefore hope to rival those admirable cartoons of our contemporary; but we will endeavour, as artists of the pen, to reproduce the manners and customs of our superiors. Do you, my brother, from your Olympian vantage-point of the House, follow the debates; leave the great questions to speak for themselves, but photograph the speakers; mark well which is physically deformed, what costume each wears—

‘The cut of necktie and the cock of hat;’

at what critical moment Disraeli sneezes, Gladstone spreads his coat-tails, Forster sticks his hands in his pockets, Bright seizes and drinks a glass of water. Miss not a smile, a frown, a scowl, a straddle. Seek out each member’s tailor and bootmaker, and, if possible, penetrate to the light, or darkness, of his under-linen. If any member has a pimple, make a note of it; for of such trifles our life is made, and this may be a proof of habitual intemperance. Above all, be spiteful, be impudent, be mean. As for you, mine other brother (apart from your divine mission of supplying us with a portion of the needful), go forth, if not in safety yet in boldness, upon the Stock Exchange; do there what our friend is doing elsewhere, but do far more: be virtuous, that is, assume a virtue if you have it not, and from time to time make our welkin ring with the alarm of ‘Thieves!’ I myself, who once had a passing if somewhat inglorious connection with the late Mr. Thackeray, am well fitted by long habit and custom to do the general social satire of the paper. If our venture flourishes I will, with the first proceeds, purchase a horse, and move among the society of Rotten Row, where, trust me, I shall become 689 rapidly distinguished. Leave the rest to me. We can lose nothing, and with proper audacity we must succeed.” So one morning, fresh from the chaos of Grub Street, rose the World, playfully called “a Journal for Men and Women.” (The Snob, it may be noted in passing, always talks of himself as a “man,”—“it makes a man’s blood boil;” “this is what no man can stand;” “what on earth is a man to do?” being among his familiar stock-idioms.) Society was startled, and up to the seventh heaven soared the young man of the name of Guppy!

The programme, briefly sketched above, was carried out, not without important additions. One axiom was laid down at the outset—never, if possible, to let a number pass without an allusion to the Prince of Wales. At first these allusions, doubtless for the purpose of attracting attention, were insolent to audacity, but latterly, since the editor has achieved his social ambition and founded his paper, a quite different tone has been adopted, and the allusions have been couched in such a style as to convey the fact, or fiction, that the editor is on terms of easy familiarity with His Royal Highness.

“I hear that the Prince of Wales finds Marlborough House too small, and is about to migrate to South Kensington.”

“The Prince of Wales has declined to be made a member of the Geographical Society for the Exploration of Central Africa, of which the King of the Belgians is President.”

Carefully note the inference.

“It reaches me from two different sources that the Prince of Wales, on his return through Paris the other day, expressed himself as much disquieted at the condition of affairs in Greece.”

“The Prince of Wales entertained a bachelor party at Eastwell last week, including the Duke of Teck, Lord Huntley, Lord Dupplin, Lord Supplin, and Colonel Farquharson.”

In his hungry eagerness to get the Prince of Wales into the number at any price, the editor even makes copy of accidents which have not happened:—

“The Prince of Wales had a narrow escape going down from London to Melton the other day: a luggage train being shunted only just in time for the royal express to pass. Had the train conveying the Prince been a little later, a fearful accident must have occurred.”

Add to accidents which have not occurred visits which have not taken place:—

“The Prince of Wales, it seems, was to have paid a visit to Colonel Owen Williams, in the Isle of Anglesea, on the 15th January. His Royal Highness, however, has now written to the gallant Colonel postponing the visit until next summer.”

The comparison is a sad one, but in these weekly lucubrations of the Editor of the World we are irresistibly reminded of a certain Mr. Dick, the harmless lunatic who in vain tried to keep Charles the 690 First out of his “memorial.” If the Prince of Wales could only be left out of the World for one or two consecutive numbers, we should feel more convinced than we do of the editor’s perfect responsibility.

The same haunting gentility characterizes this gentleman’s familiar gossip on affairs in general. The reader must be made aware, at any price, at all hazards, that the gossiper, whatever his antecedents, is now a heavy swell, who moves, chiefly on horseback, in society. “More gravel, Mr. Gerard Noel, if you please!” he gasps in one number, fresh from his gallop in the Row. Having found his way to the house of a fashionable lady, this is the way he rewards her for his entertainment, while proudly intimating the fact that he himself was there:—

“Lady Waldegrave commenced her series of dinners and drums on Friday last. Those who were present, after remarking a well-known American lady, were struck with wonder, and asked each other to what possible portion of the human frame a diamond brooch would next be attached?”

How Mr. Guppy and his acquaintances would chuckle over this, just as long ago they chuckled over the allusions to Mr. Thackeray’s nose! And great, no doubt, would be their ecstasy to note the pathetic air of familiarity with which the equestrian editor talks of his friends:—

“Poor Josey Little died in Paris of jaundice. A week ago he wrote to a friend that he was much better, and hoped soon to be able to return home. But, in truth, he never recovered the serious illness of some years since, and had not sufficient constitution left to stand against a sharp attack.”

Again:—

“So poor Bill Clayton of the 9th Lancers has gone over to the majority, and that in a pitiably sad and sudden way. There was no better officer, better fellow, and stauncher comrade in all the British army. I should have said he was at his best across a cramped country where the going was heavy, were it not that I remember him as the beau idéal of an aide-de-camp, as quick at catching and communicating an order as he was over the roughest country on the gallant little chestnut with the blaze face and white heels.”

It matters little that we, in our social ignorance, know nothing either of “poor Josey Little,” or “poor Bill Clayton,” and cannot even determine whether they are real persons or figments of the same troubled brain which cannot keep the Prince of Wales out of the memorial—that is, the newspaper. What we do admire and feel is the fact, or fiction, that we are hearing in a delightfully familiar way about real “swells.” That there be no mistake about it—no mistake about the fact that our editorial equestrian knows these people and the world they move in—he now and then, after recording an interesting domestic fact, becomes mysterious and profound:—

“I hear Mr. Alfred de Rothschild gave £60,000 for Mr. C. Sykes’s house.”

“On Tuesday the 13th, before these lines are in the reader’s hands, the 691 members of Boodle’s Club will have assembled in general meeting, to decide whether a person against whom grave charges of conduct of the basest kind have been brought and sustained is to be permitted to continue in the Club. One may suppose that the verdict of society will be indorsed by the members of the Club, and that the person in question will have to retire.”

This is dark and ambiguous. It cannot of course refer to the writer’s self, and “a man” is set wildly speculating—in the intervals of guessing “double acrostics,” for which, of course, there is a prominent place in this oracular journal as well as the other—which of “a man’s” acquaintances is being referred to. Of one thing we are positively certain—that the Club which tolerates in its bosom the chronicler of “what the world says” must be in a very bad way indeed. What society of respectable “men,” not to say “gentlemen,” would associate for ten minutes with the retailer of such talk as the following?—

“What is Madame Patti’s age, and to what country does she belong? There would seem to be considerable doubt on both these subjects. It has been frequently stated, since the recent scandal, that the diva is in her thirty-seventh year; but this does not seem to be correct, as Vapereau and all the biographies agree that she was born in the spring of ’43, though somewhat at variance as to the month. She is generally believed to have been born of Italian parents at Madrid, although there are not a few Americans who are firmly convinced ‘the American nightingale’ first saw the light in the States. The last story I have heard is that the Marquise—we must not say the ex-Marquise yet, I suppose—is really the daughter of a Jew dealer in Houndsditch, and that she was sent to spend some years in America in order to efface the East-end connection, and give her that exotic air English people so much approve of in singers, it being a well-known fact that no Englishwoman can hold a candle to a foreigner on the operatic stage. What countrywoman, then, is Madame Patti—Spanish, or Italian, or American? Her marriage-certificate—she was married at the French Consulate here in London, I believe—would clear up the matter, French law being very much more particular than our own in such matters.”

There are other paragraphs on the same subject, but with these we simply decline to stain our pages; they are too incredibly base for quotation. On one occasion, finding his own imagination barren, the editor quotes scurrilous verses from “our lively neighbour the Gaul;” and all this at the expense of a lady with whose private life we have nothing to do. Even Mr. Guppy would hesitate before flinging filth at a helpless woman.

The allusion to Madame Patti reminds us that the life of the “man” is not all sunshine. We gather from his own mouth that he has his troubles. Although admitted to what he calls “the house and club of Mæcenas,” and recognized (for what we really should not have taken him) an “accomplished littérateur of lowly origin,” it is only because he “amuses as a buffoon or is serviceable as a butt.” This is very hard, though, to be sure, we should never have made the mistake of thinking the “man” “amusing.” This moreover, is the sort of thing which takes place. “A great peer, 692 a bulwark of the Constitution, and the keystone in the arch of Conservative organization, invites an able editor or journalist to dinner. Before the dinner is over, the noble host, Crœsus though he is, asks his guest whether he cannot procure him a box for the Opera. Such is the disinterested friendship of the great!” It is very sad, but really, we should like to know which of our great rulers not only invites the Editor of the World to dinner, but goes the length of asking him for a box at the Opera? By all means let us have his name! Is it Lord Derby or Sir Stafford Northcote? Can it possibly be Lord Beaconsfield? Or must we rush to the conclusion that here again the editor is puzzle-headed, and just as he cannot keep the Prince of Wales out of his memorial, mistakes some clerk in the Foreign Office, with whom he is on dining terms, for a great peer and a “bulwark of the Constitution”?

But let no one rush to the conclusion that the “man” is proud. Far from it. Easy with his superiors, familiar with his equals, jocose with his inferiors, he has a cheerful manner with everybody. While he shrugs a character away, or smiles in his facetious style at virtue, he really affects no superiority. And though he cares little for nature or art, though his literary accomplishments are in his own imagination, and his artistic perceptions sadly to be mistrusted, he absolutely has his opinions and his objects of idolatry. First, of course, in his cosmogony comes the “Prince of Wales,” of whose domestic life he has given, in a recent number, a lively picture. But, we repeat, he is not proud. In the course of a series of visits to “Celebrities at Home,” he not only waits hat in hand upon such first-class personages as the Pope of Rome, the Marquis of Salisbury, the Duke of Beaufort, President Grant, and the Earl of Shaftesbury,—telling us with charming frankness what they eat and drink, what rent they pay, who takes his tea with sugar and who not, &c., &c.,—but he even condescends to visit players like Mr. Irving, and artists like M. Doré. Nor is this all. He still descends, to quote Shelley,

“In the deep!—in the deep!—O below the deep!”

for we find him on one occasion giving us a picture of “Mr. J. L. Toole, in Orme Square,” and on another, an account of the daily life of “Miss M. E. Braddon (Mrs. Maxwell) at Richmond.” Now, it is quite possible that there may exist, in this strangely constituted planet, beings to whom the private life of a low comedian is an object of interest. The interviewer, doubtless, knows his public best, and he writes for them alone. It is in their interest, therefore, that we are informed that Mr. Toole “now owns for a term of years a capital house in a first-rate locality, at an annual ground-rent of about a hundred a-year;” that the collection of pictures in Orme Square includes “two hundred and 693 seventy-three portraits of Mr. Toole in as many different parts” (!); that Mr. Toole is so fond of “sacred music” that he has bought his little boy an “organ” to grind upon “after church on Sundays;” that when Mr. Toole “went to America, Mrs. Toole and his son and daughter, and the latter’s governess” accompanied him. The interviewer goes on to describe the comedian as even “funnier off the stage than on,” adding, that “fun is a feeble word to express the overflowing, energetic, and inexhaustible humour with which our prince of low comedians is endowed.” Unfortunately, samples of this “overflowing, energetic, and inexhaustible humour” are quoted, and make one fear that the “prince of low comedians” is much the same in private life as upon the stage. Possibly the daily contemplation of “two hundred and seventy-three portraits of himself” may have a depressing influence upon him, and induce in him that obtrusive self-glorification which chiefly constitutes his “inexhaustible humour.” We were almost at a loss to conceive why so very ungenteel a person was interviewed at all, when we came upon these words:—

“Filling an honoured place in our host’s sanctum is an autograph letter framed and glazed. It is dated from Marlborough House, is signed ‘Albert Edward,’ and after conferring a favour in gracious phrase, goes on to say of the Steeplechase, which we all saw the other day at the Gaiety, ‘It is a capital farce, and I think Toole acts better in it (if possible) than in any other piece I have seen him in.’”

The Prince of Wales again! His very “autograph”—“framed and glazed”—“conferring a favour in gracious phrase” upon Mr. Toole! Well may the interviewer exclaim, with tears in his eyes—

“Among the valuable relics with which Mr. Toole’s house abounds, there are few upon which he places higher value than upon this flattering expression of opinion in a familiar note from His Royal Highness to a common friend.”

A common friend? Dare we guess who this common friend is, whom the writer in his modesty forbears to name? Yes; it must be the interviewer himself. Really, though, such a friend should rather be called uncommon. Conceive the picture of the noble trio of kindred spirits—the Prince of Wales, Mr. Toole, and the Editor of the World! *

Curious to ascertain the literary predilections of the Editor of

_____

* The spirit of gossip is contagious, and there is an anecdote afloat which seems too good to lose, especially as rumour refers it to Mr. Toole himself. When Artemus Ward was giving his inimitable entertainment in England, and being made much of by distinguished people, an English comedian, known for his devotion to the aristocracy, eagerly congratulated him on his popularity with the fashionable and the great. “Yes,” drily said Artemus, “they won’t leave me alone! When I first came over, they boarded the steamer and offered me a dukedom; but I wasn’t to be bought!”

_____

694 the World, with whose dramatic tastes we are already acquainted, let us follow him as he ambled down to Richmond,

“Witching the world with noble horsemanship,”

and eager to interview one who, in the realm of fiction, has been his own leading inspiration. Hearken to him, as he opens in the approved style of the circulating novel:—

“As a solitary gleam of wintry sunshine lights up the shapely trees and broad green glades of Richmond Park, and the wind whirls the leaves in circling eddies, we discover that we are not alone in our morning canter. Sweeping along at a hand-gallop comes a lady clad in riding-dress of the severest order; the sable habit is relieved only by a tiny patch of colour at the throat, and the orthodox ‘chimney-pot’ completes the costume. The horsewoman is the owner of a name known wherever the English—and for that matter the French—language is spoken; for her work, once sneered at in this country as ‘sensational’ was quickly appreciated by the Gaul, whose keen instinct detected its dramatic power. She sits her white-footed golden bay squarely and well, now and then leaning slightly forward to pat his muscular neck, and call him by pet names; for Kaiser is a favourite animal with his mistress, who, as her writings indicate, possesses a generous sympathy with horses and dogs, cats and birds. Her gallop on Kaiser is at once the exercise and the recreation of one of the most diligent and successful workers of the time; but it is soon over, and we turn our horses’ heads towards Lichfield House, a fine old dwelling of various-coloured brick, with oaken staircase, bay windows, and oddly shaped rooms, looking over long strips of lawn.”

“Circling eddies” is good, and so is “white-footed golden bay.” The interviewer fails in his duty, in so far as he neglects to tell us the price of the horse or the rent of the house—not to speak of whether the fair horsewoman, who is no other than Miss M. E. Braddon, is stout or thin. That she is married, we infer from the name—“Mrs. Maxwell”—printed in brackets at the head of the article; but strange to say, not a single word is said of the individual whose name she shares. This is too bad; and in the name of Guppy, we protest. Surely a lady’s husband is as important a feature as her “golden bay,” or her “riding-dress of the severest order.” We are not appeased by learning such trifles as that “Mrs. Maxwell” has written “thirty three-volume novels;” that she writes them “in a particularly low, uncomfortable chair, huddled up, with a piece of cardboard resting on her lap, and a little ink-bottle held firmly in the left hand;” and that she “writes on the inner edge of the pen, and punctuates most exactly.” These details, though precious in themselves, are trifles compared with what we, as the mouthpieces of Guppy, demand to know. Nor are we appeased by the information that Mrs. Maxwell “reading widely and diligently,” “gave her chief study to Balzac and Bulwer, and even now regards Balzac and Bulwer” (or shall we not say Bulwer and Balzac?) “as the great masters of prose fiction.” This taste, which the interviewer thinks is “curious evidence of the waywardness of human nature,” would perhaps 695 strike ordinary people, who have not had the advantage of seeing the fair authoress “huddled up” in her study, as “curious evidence” of literary colour-blindness.

That there may be no mistake about the tastes of the Editor of the World, he thus expresses his opinion about a novel by Ouida:—

“Ouida’s new story, ‘Ariadnê,’ is not only a great romance—so great that it has been found necessary to divide its publication between two publishing firms—but a great and consummate work of art, remarkable beyond anything which Ouida has yet given us for simplicity, passion, severity, beauty. . . . The philosophy or moral of the book is purely pagan. It is full of bitter, passionate readings against progress, history, civilization so called, and the dethronement of the old gods of Olympus. . . . In an æsthetic age like the present, the artistic element in the book will be generally a recommendation. It is as a work of art that ‘Ariadnê’ must be judged; and as such we may venture to pronounce it without fault or flaw in its beauty.”

Certainly, the Editor of the World has the courage of his opinions. Here is praise which a moderate man would hardly like to apply to a recognized masterpiece, thrown like a huge bouquet at the head of the nondescript author who calls herself “Ouida;”— a very cauliflower of a bouquet—all peonies, instead of roses! Beguiled by this enthusiasm, we have actually read “Ariadnê,” not without sore discomfort and unutterable weariness, and we have found it, if possible, even poorer stuff than the writer’s other unmentionable effusions. We, however, cannot pretend to be initiated, for we have not had the privilege, accorded to our interviewer, of seeing “Ouida at Villa Farinola,” and have not therefore been carried away by visions of the lady’s wardrobe or calculations of the lady’s income. Yet one avowal we may safely make. Those who admire the writers of the World will appreciate Ouida, and those who think Ouida’s last novel “without fault or flaw in its beauty” will certainly find solace and nourishment in the literature of the World.

It is poor work dissecting a butterfly, or, dare we say, a grub? Let us leave the “literature” of the World, and, returning to its history and to its commercial and internal growth, briefly chronicle how, by the simple process of fissiparous division, the reproductive system common to the lowest organisms, it multiplied itself under the public eye. We have alluded above to the three choice spirits who invented, arranged, and started this new thing in journals. It seems that three minds so great could not exist together in peace; and so one day the parliamentary genius seceded from his post, and the next the Stock Exchange hero followed suit. New geniuses had to be found to chronicle the parliamentary “small beer,” and keep a sharp eye on the mendacities of the Stock Exchange; for the first in his vaulting ambition wanted a paper all to himself, and the other in the superabundance of his natural 696 and acquired accomplishments doubtless thought himself cribbed, cabined, and confined in the limits of a monetary article. So the first gentleman started another new thing called Mayfair, and the second gentleman another and even newer thing called, with happy audacity, Truth. Here was an embarrassment of riches, in all conscience! The secession of the two gentlemen seemed to make little difference to the original journal, for the editor was a host in himself. Another genius described Mr. Gladstone’s necktie and Dr. Kenealy’s umbrella; still another genius assumed a virtue though perchance he had it not, and made moral peregrinations through Throgmorton Street and Change Alley. It mattered little. The pretty stories, the gushing “interviews,” the salacious articles on female dress and undress, and, above all, the double acrostics, remained. The World lived—Mayfair and Truth began to fight for life.

Now of the three geniuses alluded to above, perhaps the parliamentary genius was the cleverest. He had written certain sketches of “Men and Manners in Parliament,” which, though undoubtedly subacid and impertinent, showed a keen vision for personal oddities, and he had certainly invented the new style of political reporting. His new journal, Mayfair, had all the merits of his style, and did not err by imitating the worst features of the abandoned journal. We may go further, and frankly aver that its tone was better, robuster, and less obnoxiously characteristic. It dealt less in foul gossip and more in genuine news. For the rest, it had its personal caricature and its double acrostic, and bore the same relation to a real journal as a frisky tom-titmouse does to a respectable and thoughtful owl.

But what shall we say, what must we say, and what is it worth while to say, of the publication called Truth? At first sight, it looked like a railway guide, bound in a blue cover and carefully stitched; but unfortunately it was neither so useful nor so innocent The inspiration of its projector appears to have been as follows. “Truth consists in flatly and positively expressing one’s opinion on every subject, from Shakspere to the musical glasses, in as offensive a way as possible. No preparation, educational, literary, or artistic, is necessary. One man’s opinion is as good as another’s under any possible circumstances; and it is the noblest form of ‘truth’ to give everybody or anybody the lie direct. The one gift for a truth- speaker is impudence. As I am supremely gifted with this quality, I propose, with certain reservations, to write the whole of the journal myself.”

Now, up to a certain point, this individual was right. He saw that honest writers were scarce, that some were afraid to speak their minds, that many had no minds to speak, and that a little plain writing in journalism would be considered refreshing. There 697 was a great deal of cant afloat. Men and women frequently pretended to be better than they should be. The air was full of bubble reputations. Society, art, literature, the drama, needed purifying. And really a little “truth” was wanted. But the individual erred grievously in so far as he assumed that “Truth” was mere negation, and that only boldness was required to equip a truth-teller from head to foot. For example, if a bookbinder’s apprentice were to rush into print saying that he didn’t believe in Shakspere’s literary talent, or if a photographer’s tout were to asseverate with all his lungs that Titian was colour-blind and that Michael Angelo could not draw, such forms of assertion would hardly create any commotion, even in Gath. Preparatory to giving an opinion, it is expedient if not imperative to cultivate the ability of forming one. Here our genius grievously erred, and here we heartily wish his errors had had an end. But no!

We are not going to assume for a moment that “Truthful Tommy” (to quote the playful signature over which our truth- teller often writes) is inferior either in gifts or knowledge to his original partner, the Editor of the World. On the contrary, we infinitely prefer him. There is a sublime and négligé ease about his insolence to which the other cannot for a moment aspire; nor does he affect airs of shabby gentility, or clamour pathetically for “more gravel,” or drag in, incontinently, the names of any of the Royal Family. In his deep and ineradicable conviction of the natural baseness and idiocy of human nature, in his unalterable belief that the greatest and least of mankind see with his eyes, hear with his ears, and think with his brain, in his confirmed and audacious habit of omniscient nescience, he is certainly without a peer.

Let us cull a few pearls of gossip, to show how our truth-teller began:—

“There is no truth in the report that a noble earl who recently ran away with a noble baroness have separated (sic!). The guilty love-birds are in Paris, awaiting until the ‘nisi’ in the decree has run its course.”

“So Lady Salisbury has become an advocate of polygamy. I am glad, however, to hear that Lord Salisbury declines to take advantage of her ladyship’s conversion, and that there is no fear of half-a-dozen Circassian brides doing the honours of Hatfield House.”

“Nicolini, or Nicholas, the now famous tenor, is the son of a pork-butcher at Dieppe. His sister was formerly lady’s-maid of the Duchess of Wellington.”

“The Marquis de Caux paid a flying visit to London last week. As the French law does not permit divorce, the Marquis and the Marquise will still remain man and wife. It will depend upon the Marquise whether an amicable or a judicial separation be come to. If she be wisely advised she will consent to the former. The husband has no wish to make public the evidence which he has against the lady, who, perforce, must continue to bear his name, but he, very properly, is determined not to pass for un mari complaisant.”

698 “Nicolas, or Nicolini, the singer who is the bone of contention between the Marquis and the Marquise de Caux, is the son of a cook, and this, a correspondent suggests, is why he is so fond of a Patti.”

“So Lord George Loftus is dead. He was no one’s enemy except his own—a weak, easy-going, good-natured man. A year or two ago he resided at Boulogne, and his mind fed upon the idea of marrying a wealthy widow. He used to go down to the quay to await the arrival of the Folkestone steamer; if he perceived an acquaintance amongst the passengers, he would accompany him to the railway station, and urge him to look out for a widow anxious to acquire a title by entering into the holy bonds of matrimony. ‘She’ll be, you know, my Lady at once. I’m strong and hearty, and perhaps I shall outlive my nephew, so explain to her that she will have the off-chance of being a Marchioness,’ was the burthen of his lay; and then he used to suggest that the surest covert for wealthy widows was in the neighbourhood of Manchester. Poor fellow, the last time I saw him he offered me 20 per cent. on the fortune of any wealthy widow whom I could unearth for him. Not being myself in the ‘matrimonial bureau’ business, I recommended him to advertise in the Matrimonial News. I do not know whether he followed my advice.”

“Once a rich girl was showing all her toys to a poor girl. The latter viewed them with an apparently indifferent glance, for she did not wish to show how she longed for them. ‘Do you envy me?’ said the rich girl. ‘No,’ replied the poor girl, ‘for I have got one thing that you have not got.’ ‘What is it?’ said the rich girl. ‘The itch,’ answered the poor girl.”

“Thirty years ago I used to know the daughter of an English consul in America. She was periodically getting divorced, and she had to write on a large map of the United States the name of her husband in each State, in order to prevent confusion.”

“The other day there was a party at the castle of a noble duke. A lady undertook to go out of the room, and, on her return, to do something to remind every one of a person who was known to all of them. She came slowly into the room, looked at her hands, and said, ‘Dear me, I have forgotten to wash them this morning.’ Then, seeing a bonnet upon a chair, she sat down upon it, and crushed the bonnet. With one accord all assembled shouted the name of the wife of one of our most eminent political leaders.”

“What a lucky fellow the Rev. Barrington Gore Browne, incumbent of All Saints’, Alton, must be! He is fortunate in being a son of the Bishop of Winchester, but he is still more fortunate in having led Helen Mackenzie Jackson, eighth daughter of the Bishop of London, to the altar last week. Both prelates officiated at the ceremony, and, having regard to the good things which usually fall to the clerical sons-in-law of Dr. Jackson, the Rev. Barrington Gore Browne may esteem himself twice, if not thrice, blessed in his matrimonial speculation.”

It will be seen from the above specimens that “TruthfuI Tommie” is not particular as to the nature of the gossip he retails for his readers. The cleanliness of his allusions is as noticeable as the delicacy of his insinuations and the elegance of his grammar. He is, moreover, far above anything like reverence or hero-worship. Take the following anecdote as a sample of his correct taste and touching frankness:—

“Nearly twenty years ago I used to know Count and Countess Bismarck in Frankfort. The Count was regarded as an able man, but in appearance dull and heavy. Since he has become a great man, ‘his genius is reflected in his expressive countenance,’ according to newspaper correspondents. 699 Twenty years ago he often passed the entire night drinking beer in a garden looking over the Main. In the morning, after a night passed in beer-drinking, he would write his dispatches, then issue forth on a white horse for a ride, and on his return attend the Diet, of which he was a member. Some few years later I was dining at the table d’hôte at Wiesbaden. Opposite me sat a thin emaciated man, who looked as if he had only a few weeks to live. The thin man said, ‘How do you do?’ to me, but for a moment I did not recognize him. Then I remembered that he was Bismarck, and my recognition of him was owing to his hands. I never yet saw a man in respectable society with hands habitually so filthy. He had been ill, he said, and he hardly knew whether he would recover. Had he not, the world’s history would have been altered.”

This is delicious. The picture it gives of the intimacy between two great men has few parallels in modem history. How valuable the social reminiscence, if true! how delicate the allusion to “nights passed in beer-drinking,” and to the “hands habitually so filthy!” Yet truthful as “Tommie” is, we should require stronger evidence than his own unsupported oath that he ever had a more intimate acquaintance with Bismarck than a passing stare at him across the cloth at a table d’hôte. The lion does not lie down with the lamb, or lap-dog, in that fashion.

It is no part of our purpose to waste space in further citations of the gossip from the new thing in journalism called Truth. Our readers have had quotations ad nauseam. If they will turn to the publication for themselves, they will ascertain that it is exclusively devoted to articles in which vulgar women would delight, and that, in lieu of the invariable “acrostic,” there are “mesostichs and spelling sentences,” to the best guessers of which prizes are duly offered. The new journalist makes no pretence of passing beyond his proper spheres—the drawing-room, the club, the theatre, and the music hall. Here he is omniscient, indeed infallible; yet the weight of wisdom is not upon him, and his experience, such as it is, has been bought only in the slums of the World and the purlieus of Vanity Fair. His merit is the downrightness of his impudence, the perfection of his self-confidence. His opinion on any possible subject, he holds, is as good as any man’s —in fact, a good deal better, for he is evidently convinced that he is not a humbug. Yet alas! the very sublimity of humbug is this posing as an anti-humbug. Once or twice, though not often, he is spiteful, as where he discusses the works of Mr. W. S. Gilbert, and seeks, in a quite unworthy way and we fear under degraded influences, to undervalue these works commercially. But as a rule he is far too indifferent to be spiteful. He simply does not and cannot believe in the superiority to himself of any human being. His life is one of “first nights,” of dinners at Richmond, of little trips to Paris, of the last new scandal and the last new novel. He appears to despise, and does perhaps despise, that life; but after all he thinks it is the life that all men live, and for the 700 sake of those others who are as he, he prints his little journal, and lays down, with little learning, his little social law. Let him go his ways. He has human impulses, for the sake of which we could forgive him much.

We have spoken at some length of four specimens of the new style of journal —Vanity Fair (which we are fain to consider the archetype of all the rest), the World, Mayfair, and Truth. But the list is far from ended. Of the same way of thinking, of the same way of scribbling, are the Whitehall Review and London. The Whitehall Review is vapid and silly as its title, and is chiefly distinguished for a series of highly ornate and flattering portraits of lady “leaders of society.” The journal called London has some sparkle, but resembles the others in its habitual flippancy and predominant spitefulness. Of all the journals we have named, all of which bear a strong family likeness, Mayfair is the most to the purpose, London is the most “literary,” Truth is the most straightforward, and the World is the most ridiculous. Up to the present moment of writing, they all exist, and spread their gay wings in the autumn sunshine. Yet we hope, and indeed believe, that the longest-lived of them all will be ephemeral, and that, with the novelty of their moral impudence and social irreverence, their circulations will die away. If this were not to be hoped and believed, the prospects of journalism would be dark indeed.

We have dealt with these new pests of journalism in a spirit as little serious as possible, for truly, to a spectator with some sense of incongruity and the foolishness of human nature, they are not without their amusing side. But before concluding, let us ask without levity—“What does this phenomenon portend? to what rottenness in our social life does it point?” Some few years ago, a journal which devoted its columns exclusively to the latest scandal, indecent suggestion, articles on feminine underclothing, foolish fiction, and “double acrostics,” would have had either to go without a circulation at all or have had to find it in the scullery or the butler’s pantry. Our established journals were perhaps not wise, nor particularly brilliant, but they were at least written for rational beings. Yet now, at this hour, the air of England, or at least of the metropolis, is alive with these silly and indecent newspapers, without literary talent and without journalistic grace. Who buys them? Who reads them? Bought they are, and read. It would be an insult to any man of fair culture, or to any woman of ordinary delicacy, to ask if they spend their time reading twaddle about “society,” and guessing double acrostics and mesostichs. So we are driven to the sad conclusion that men without culture and women without delicacy are hourly on the increase; that a new literature is being created for a new order of the vulgar-genteel, who are too ignorant to care for even the literature of the 701 circulating library. That women are largely appealed to in these wretched publications, is apparent at a glance; that foolish and meretricious women delight in them, we can well believe; but that women of refinement could possibly purchase them and read them, we most unequivocally deny. It follows that the ladies we see smiling over Truth, or simpering over Vanity Fair, are meretricious women, and without refinement. For their sakes are culled these choice scandals about the private life of opera-singers; these strongly-scented anecdotes of the coulisses, this flotsam and jetsam of a world that is nothing if not salacious. What delights the young man of the name of Guppy delights them too; and they share their enjoyment with him and with his kind. To them, as to the reviewer of the World, the productions of Ouida are literature; to them, as to the readers of Vanity Fair, mock- valentines are humorous art. Their culture is the culture of the scribbler in London, who assumes airs of instruction and even pedantry because he can spell through Gautier’s “Histoire du Romantisme,” and is familiar with Zola’s last

“scrofulous French novel

On rough paper with blunt type.”

They read Mayfair, because they like to hear about Mr. Gladstone’s boots and Mr. Jenkins’s waistcoat. They cultivate Truth, because it is so much stranger and more highly spiced than fiction. For the guidance of these ladies of the period, the World has published its “Modern Child’s Catechism,” which we give as our last quotation:—

“THE MODERN CHILD’S CATECHISM.

“Question. Pretty little girl, what is your name?

“Answer. Tottles.

“Q. Who gave you this name?

“A. Mamma’s chums and my pals at Prince’s.

“Q. What did your proposer and seconder promise for you?

“A. That I would be presented at Court at seventeen, would always if possible observe the ordinances of society, and would always keep my men to myself.

“Q. Do you propose to fulfil their promises?

“A. Yes, if I cannot improve upon them; and I am duly thankful that I came into the world when it had become sufficiently enlightened to know that girls were only born to amuse themselves, and supremely pity those hapless infants who are dressed in brown holland, made to sit in the schoolroom learning lessons, and do not know how to flirt.

“Q. Perhaps you will tell me your Social Creed?

“A. I believe that the first person in the world to be considered is myself; secondarily, any man I fancy at the moment; thirdly, my parents when they are not in the way. I believe that beauty is the trump-card for a woman, and that if she has not got it she must be chic, say hasardé things, and dress extravagantly. I believe that money is the one thing in the whole world worth caring for.

702 “Q. What do you mean by the ordinances of society that you promised to keep if possible?

“A. 1. To muzzle Mrs. Grundy, if it is not too much trouble. 2. To remember that it is always a case of self first, and the rest nowhere. 3. To remember that strong expressions sound best in foreign tongues. 4. To go to the church where there is the best music and the smartest bonnets in the morning, when I am up in time on a Sunday, to be at home only to men, or to go to All Saints’ in the afternoon, and to dine out or have a dinner at home. 5. As a child, to watch how my mother manages her admirers, and to snub my father, unless I think he will whip me; when I grow up, to draw my mother’s favourite from her, and to coax my father that he may increase my allowance. 6. Wishing a rival to break her leg at the rink is not murder. 7. Elective affinities are not yet thoroughly understood. 8. It is not stealing to take anything that belongs to a man, or to neglect to pay gambling debts, if one is a woman. 9. To tell every ill-natured story I can, which I ‘know for a fact,’ because somebody told me. 10. To wish for everything nice I see, and to get it if I can.

“Q. And these ordinances contain——?

“A. My duty towards society and myself.

“Q. Towards society?

“A. To respect it, because it is all I live for; to dissimulate anything I may do contrary to its laws, lest it should turn against me; to be rich, well-dressed, chic, to entertain largely, and to have no absurd sentimentalities about domestic happiness.

“Q. And towards yourself?