|

|

|

|

|

ROBERT WILLIAMS BUCHANAN (1841 - 1901)

|

|

|

|

THEATRE REVIEWS

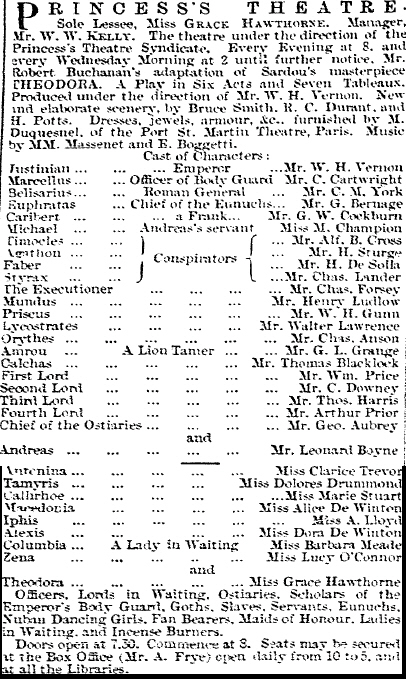

27. Theodora (1889)

Theodora

by Robert Buchanan (adapted from the play, Théodora by Victorien Sardou).

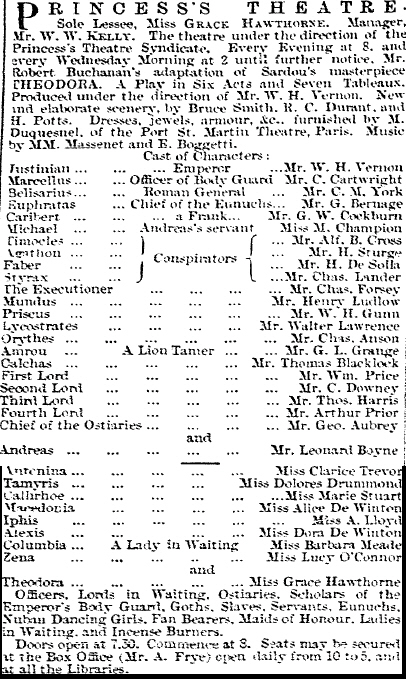

Brighton: Theatre Royal. 18 November, 1889. Followed by provincial tour.

London: Princess’s Theatre. 5 May to 21 June, 1890. Followed by provincial tour.

London: New Olympic Theatre. 1 August to 8 September, 1891.

A letter from Buchanan to The Pall Mall Gazette sheds some light on his method of adapting Sardou’s original.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

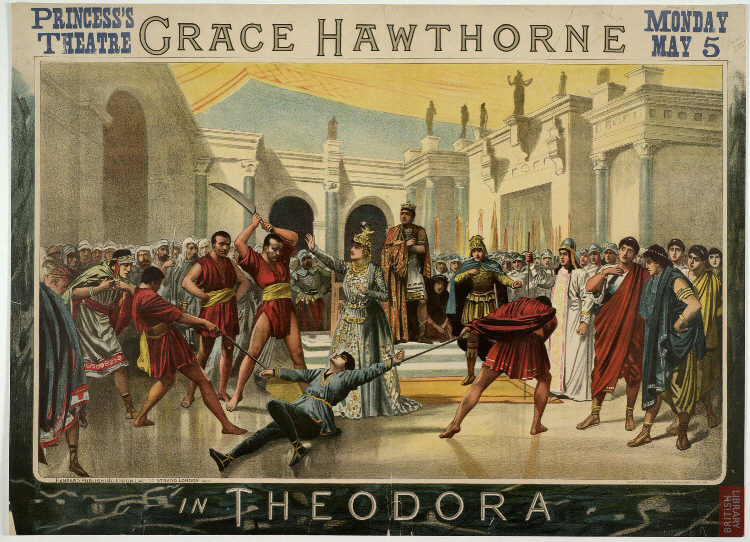

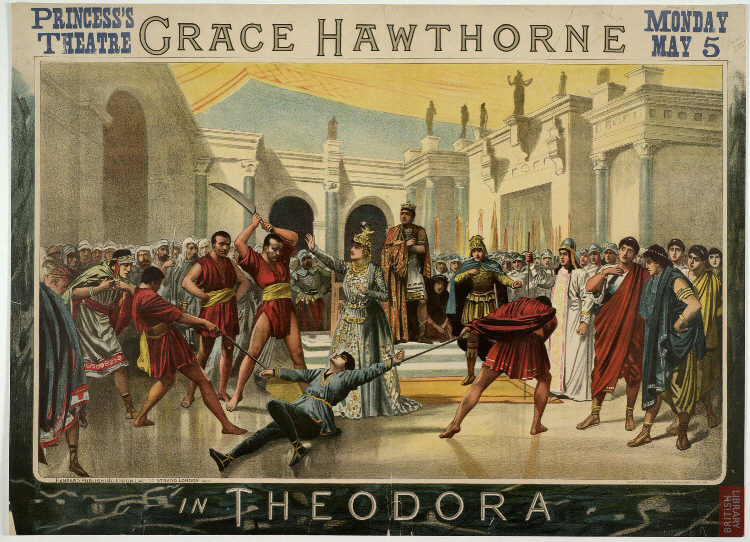

[Poster of Grace Hawthorne in Theodora.]

The Penny Illustrated Paper (29 January, 1887 - p.65)

I congratulate the clever and charming niece of Nathaniel Hawthorne—Miss Grace Hawthorne—upon her pluck and enterprise. This accomplished young American actress (who has proved successful in management where Mrs. Conover failed: at the Olympic) has taken a lease of the Princess’s from Mrs. Gooch on the same terms and conditions as the Wilson Barrett lease, which expires on May 17. “The Noble Vagabond” is running under a sub-lease. Miss Grace Hawthorne’s first production at the Princess’s will be a magnificently mounted English version of Sarah Bernhardt’s great drama of “Théodora,” the rights of which Miss Hawthorne has secured from M. Sardou. I apprehend, however, that after the Summer run of “Théodora,” Mr. Wilson Barrett will on his return from the States resume his lesseeship, inasmuch as he has arranged with Mr. G. R. Sims to provide him with a new drama at the Princess’s in the early autumn.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

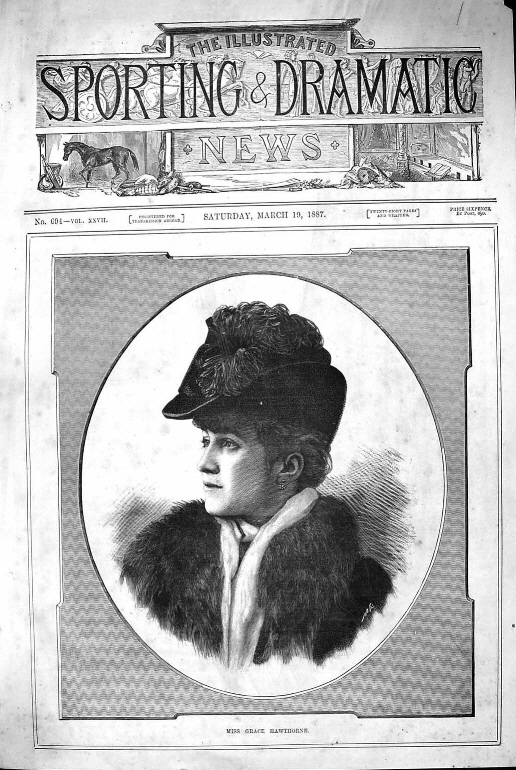

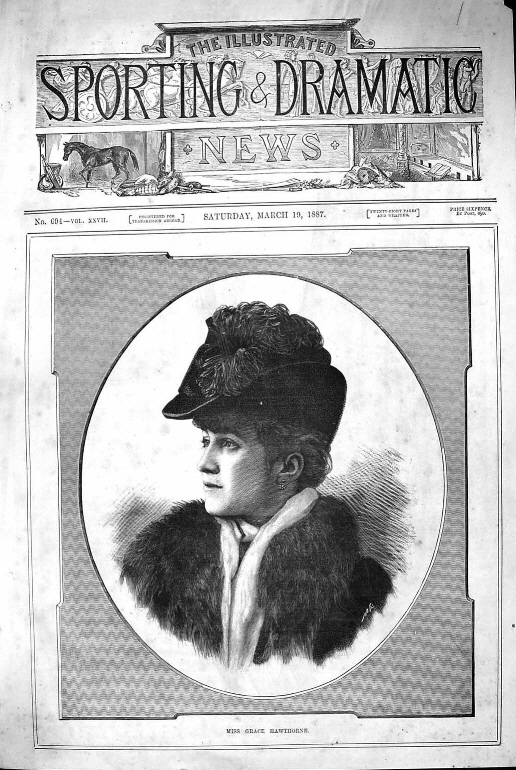

[Grace Hawthorne on the cover of The Illustrated Sporting & Dramatic News (19 March, 1887).

Click the picture for a larger version.]

The Referee (20 March, 1887 - p.3)

A statement made by a contemporary this (Saturday) morning that Mr. Clement Scott is “trying to arrange with Miss Grace Hawthorne to adapt for her a well-known French play, but that a difficulty had arisen in consequence of his terms being unusually high,” has brought me two letters and one visitor to-night. Mr. Clement Scott writes requesting me to say that the statement is “absolutely, unequivocally, and inexcusably false.” Mr. Samuel French, who is Mr. Scott’s business representative, writes that he has had no communication with Miss Hawthorne on the subject; and Miss Hawthorne herself has called at this office to say that there is no foundation whatever for the statement seeing that Mr. Scott has never even mentioned such a matter to her, nor she to him.

___

Boston Evening Transcript (22 April, 1887 - p.6)

GRACE HAWTHORNE.

_____

If the world were really as dark as it looks to us in our darker days, life would indeed be not worth living, and we could only pray to pass through the night in the hope of awaking somewhere to the light of a better morning.

I wonder if to the latest manifestation of American genius, with whom the inhabitants of staid London appear to be captivated, there ever returns the remembrance of a passage through the sombre shades of Ethiopia? In this case, however, that name stands not for a continental division, but for the saloon of a transatlantic steamer.

It was the twenty-second day of August, 1886, the second day out from New York for Glasgow. No long-continued bad weather can be expected at such season, yet the sea may be terrible for a few hours, when a West Indian cyclone is expending its death agony in our Northern latitudes. Born from Caribbean and Mexican parents, cradled in the warm bed of the Gulf Stream, the life of these storms is short and fierce, and the farther north they are encountered the more expanded, and therefore the less, their power.

But I have known bad weather in many seas, and it blew hard that day from two until ten after meridian. Probably the captain was of the same opinion, for the heavy tarpaulins were battened over the skylights, adding to the general gloom. A comfortable-looking Irish woman was saying her prayers on one of the seats, dressed as for a promenade, thinking, doubtless, that we might be called to leave for some indefinite locality without much warning. I addressed a few words of consolation to her, for which I received the customary national benedictions, and then, with rather more hesitation, comforted at my best a younger lady who had scarce moved from one position since she came on board.

She was not seasick then nor during the whole passage, but she was a glad and merry soul, banished from the light of the West into the thunder and darkness of the infernal regions. And none but strangers were near her. The sense of loneliness was more poignant because the express steamship City of Rome was just ahead of us, bearing toward England those near and dear to her heart.

An actress without her baggage is like a ship without her rigging. From successful experiences in the far West, Miss Hawthorne arrived in New York just in time to take a certain steamer, but her baggage train was delayed. So, as it was important that she should be represented in London at a given time, the others had gone without her and she followed alone on the Ethiopia.

How successful that move on the English capital has been no one can realize unless after reading the comments of the metropolitan journals. While a much-heralded lady, patronized by royalty, displaying her aristocratic self before the footlights has scarcely held the boards, this Western girl has won a triumph which is fairly unprecedented in the history of the stage.

She now controls for Great Britain Sardou’s “Theodora,” is exclusive lessee of the Royal Princess’s Theatre (Oxford street) and the Olympic Theatre (Strand), besides having purchased some half-dozen new plays from standard authors. Nor has she neglected those rôles in which her impersonations could be compared with other actresses of her own school.

When the London Times contrasts her with Mme. Bernhardt by saying that her representation of Dumas’s heroine was touching and true, and that her acting in this piece was more winning and sympathetic throughout than that of the great French artist, it is fair to conclude that it means something. To the Daily Chronicle she made the less agreeable elements of this play temporarily forgotten, reminding the critic forcibly of Modjeska. The Saturday Review, Post and Telegraph, as well as the leading dramatic journals of the day, are unanimous in the expression of similar sentiments. To quote their criticisms would simply be to transcribe from some dozen or fifteen newspapers as many favorable criticisms.

Now, whenever there is apparent an unequivocal and marked success, most persons regard it as simple good luck, causeless or from unexplained origin, and there they let the question rest.

With the reservation that there is a Divine and over-ruling power, I do not believe anything ever happens to a person in this world other than as the consequence of their own action. Napoleon III. stepped into an imperial chair, and filled it well for twenty years, but his apprenticeship was six years’ solitary study with that one object before him in the fortress of Ham. I think it was one hundred and eighty-three leading rôles which Grace Hawthorne told me she had studied and learned in less than one year.

But it is not alone study which gives the element of success to one who would touch the popular heart.

Miss Hawthorne knows that heart from experience and keen observation in those parts of our country where Nature allows it to beat unrestrained by art. Through many a Western State, in many a little mining town, she has been a dream of beauty and a vision of the miraculous to audiences for whom she was an idol. And knowledge of the hidden springs which move the soul is acquired, not in vapid New York drawing-rooms or aimless Washington society, but by contact with natures which love and hate, enjoy and suffer, showing those emotions on the surface as they are felt.

Such has been one of Miss Hawthorne’s schools, but it has not been the only one. She is not a stage-struck girl, with powerful friends or skilful managers. No. She is a hard-working actress, who has passed through the ranks of the stock company, playing inferior parts in the Eastern States, always a student, always hard at work. Of these experiences her present position is but the natural result. It is no miracle—it is a consequence. Others might have had a like opportunity and failed for want of a similar training.

In person, Miss Hawthorne is winning, sympathetic and without the least affectation. A slight, rather fragile form, clear complexion, naturally blonde hair, and a blue eye whose twinkle lasts but a moment ere the whole face beams with a merry smile. She was a most delightful addition to any circle, and although she studied her French books persistently all through the voyage, she was voted, without a dissenting voice, a most agreeable member of our company, and I know they all rejoice in her prosperity.

JULIUS A. PALMER, JR.

No. 97 State street, Boston, April 12, 1887.

___

The (Carnarvon and Denbigh) Herald (14 October, 1887 - p.7)

(Reprinted from The Illustrated Sporting & Dramatic News (17 September, 1887 - p.26)

[Note: WARNING. Contains product placement.]

AN AMERICAN GIRL.

HER EMOTIONAL TROUBLES AND HER FINAL TRIUMPHS.

HOW SHE OVERCAME NATURE’S OBSTACLES.

GRACE HAWTHORNE is a woman that would attract attention in any assemblage, not alone by reason of her personal attractiveness, but because of that bright, intelligent look and determined eye with which she is gifted.

Early in the spring the British public were startled by the announcement that Grace Hawthorne had leased the Princess’s Theatre for a long term of years, and that Mr. Wilson Barrett would no longer control the destinies of that most popular of London theatres. At first the announcement was not believed, but when it was supplemented by a statement that Miss Hawthorne was an American girl who had a few years ago adopted the stage as a profession, and who had ample capital to see her through with any engagements she might make, the general public at once accepted all statements, and prepared to watch the managerial career in London of the plucky American girl.

The first move of Miss Hawthorne on assuming the reins was to arrange for a summer season at the Princess’s by the production of a melodrama by L. R. Shewel and Joseph Jefferson (“Rip Van Winkle”). The success of this venture is as great as was that of Mr. Barrett in producing the “Lights of London,” and it will no doubt hold the boards until the regular season begins, when Miss Hawthorne will appear in the title rôle of Sardou’s wonderful emotional spectacular drama, “Theodora,” already made familiar by Bernhardt.

Miss Hawthorne has by her performances become as familiar to the London theatre-goers as she has been for some years past to the patrons of the drama in the States, and with an idea of learning more of her history in the past a reporter called on her at her cosy offices in the Princess’s Theatre the other day. He found the lady actually in tears, reading a letter from “home” congratulating her on her English successes, while the table before which she sat was piled up with business letters that had been cast aside for the one from “home.” As the reporter entered, Miss Hawthorne brushed away her tears, and, with a friendly nod and catching smile, welcomed the visitor with the real Yankee “How’de do. Take a seat.”

A glance at Miss Hawthorne is sufficient to enable a keen observer to see wherein lies her power as an actress. Emotion is written in every lineament and nervous force in every feature. Nature and art have combined to make the lady a true Queen of the Stage, and after her American triumphs her decision to come to England was natural, but was viewed with distrust by her most intimate friends and ardent admirers. Her success has justified the step, and now nothing but congratulations and favours are showered on her.

“Miss Hawthorne,” asked the reporter, “will you give the public some idea of your professional careers.”

“With pleasure. Well, to start, you must know that it is only of my life on the stage that I will speak, and regarding that there is not much of interest to the public. As a girl I felt a strong desire to be an actress, and as soon as circumstances would permit I went on the stage. It soon became evident that whatever power as an actress I possessed was of an emotional kind, and I have made a speciality of such rôles as Heron, Bernhardt, and Clara Morris have played.”

“Is not such acting very trying to your nervous system?”

“Oh, yes. You can hardly imagine how hard it is to constantly be playing what are known as the ‘weeping women’ of the stage. Why, I have played ‘Heartsease’ (Camille) in America for two years, occasionally alternating it with ‘The Lady of Lyons,’ ‘Miss Multon,’ ‘The New Magdalen,’ and other like characters, and my health was almost entirely destroyed, and now I am preparing for the production in the fall at the Princess’s of Sardou’s ‘Theodora,’ which will be the most trying rôle I have ever undertaken, for you know that Bernhardt is not able to stand playing it more than two successive nights, and yet I expect to play it for the entire winter.”

“With your past experience, do you think you will be able to stand such a strain?”

“Certainly. I don’t look strong, but I work my power now. Few people can understand the strain a conscientious actress undergoes in essaying an emotional part. It is necessary to put one’s whole soul into the work in order to rightly portray the character. This necessitates an utter abandonment of one’s personality, and an assumption of the character portrayed. It is necessary to feel the same emotions the part is supposed to feel. In ‘Heartsease’ and similar rôles I actually cry at certain passages. Audiences call it art. It may be, but they are none the less real tears, and the effect is just as wearing on the health.

“You must be aware that by their very natures women are subject to troubles and afflictions unknown to the sterner sex. The name of these troubles is legion, and in whatever form they come they interfere with every hope and ambition of life, and it makes me sad to think of the untold numbers of women that are thus suffering agonies of which their relatives and friends know nothing. I speak from a bitter experience, but I am thankful I know the means of restoration, and how to remain in perfect health, notwithstanding the nervous strain I have to nightly endure while playing.”

“Please explain more fully.”

“Well, I have found a remedy which seems specially adapted for this very purpose. It is pure and palatable, and controls health and life as nothing else will. If all suffering women were made familiar with its merits, many more well women would be met with in a short time.”

“What is this wonderful remedy?”

“Warner’s Safe Cure.”

“And you use it?”

“All the time.”

“And hence believe you will be able to stand the strain of an entire season with ‘Theodora’?”

“I am quite certain of it.”

In reply to other questions Miss Hawthorne stated that she had commenced her career as an actress in a very humble capacity in Chicago, and had been brought up in a fine school of art where merit only told. She had supported some of the leading actors of America appearing in almost the entire range of what are called legitimate rôles. About five years ago she became an emotional star, and under the intelligent and energetic management of Mr. W. W. Kelly, she had met with the most gratifying success and had established herself in America. When she came to England it was only with the intention of making a short stay, but she had been so well received that the stay had been lengthened, her interests had grown so, and having taken a long lease of the Princess’s it looked now as though she would soon become a thorough Englishwoman.—Illustrated Sporting and Dramatic News. Sept. 17th.

___

The Era (9 November, 1889 - p.10)

MISS GRACE HAWTHORNE is at last rehearsing Sardou’s Theodora, with which she opens her provincial tour at Brighton, Nov. 18th. She has been for the past month studying the great rôle in Paris, under the immediate instruction of the author, M. Victorien Sardou. The English adaptation of this play is by Mr Robert Buchanan, and the entire production is to be staged under the personal direction of Mr W. H. Vernon. The dresses, jewels, armour, &c., have been manufactured by M. Duquesnel, the director of the Porte St. Martin Theatre in Paris, and are said to be very elaborate and expensive.

___

The Stage (15 November, 1889 - p.9)

Miss Grace Hawthorne commences a four weeks’ tour with Theodora, adapted by Robert Buchanan, on Monday next at the Royal, Brighton. I am informed by the management that much money and labour have been spent over the piece, Miss Hawthorne’s dresses alone being valued at £1,500. Mr. Fuller Mellish will play the principal male character. Miss Hawthorne tells me she has been in Paris for the past month studying her character under the immediate instruction of the author of the play, Sardou. Mr. W. H. Vernon will be responsible for the stage management. The cast is long, so more about the others in the piece next week.

___

The Stage (22 November, 1889 - p.10)

“THEODORA.”

On Monday, November 18, 1889, at the Royal, Brighton, was produced an adaptation, in five acts, by Robert Buchanan, of Victorien Sardou’s play, entitled:—

Théodora.

Justinian ... ... ... Mr. Arthur Lyle

Belisarius ... ... ... Mr. Cecil Morton Yorke

Euphratas ... ... ... Mr. T. P. Haynes

Marcellus ... ... ... Mr. Thalberg

Caribert ... ... ... Mr. Charles Macdona

Andreas ... ... ... Mr. Fuller Mellish

Michael ... ... ... Miss Rosie Lewis

Timocles ... ... ... Mr. Harcourt Beatty

Agathon ... ... ... Mr. Geo. W. Cockburn

Taber ... ... ... Mr. Thos. Blacklock

Styrax ... ... ... Mr. Henry Gray Dalby

Executioner ... ... ... Mr. Charles Forsey

Mundus ... ... ... Mr. John Drummond

Priscus ... ... ... Mr. Henry Ludlow

Orytties ... ... ... Mr. James Ferguson

Amron ... ... ... Mr. George Luke Grange

Calchas ... ... ... Mr. Valentine Ostlere

1st Lord ... ... ... Mr. Harris Lawrence

2nd Lord ... ... ... Mr. Charles Anson

3rd Lord ... ... ... Mr. Frank Pierson

4th Lord ... ... ... Mr. William Bruce

Chief of the Ostiaries ... Mr. Gerald Harley

Antonina ... ... ... Miss Clarice Trevor

Tamyris ... ... ... Miss Dolores Drummond

Macedonia ... ... ... Miss Annie Lloyd

Callerhoe ... ... ... Miss Katie Rayne

Iphis ... ... ... Miss Marie Stuart

Ixia ... ... ... Miss Dora De Wynton

Columba ... ... ... Miss Alice De Wynton

Zena ... ... ... Miss Walner

Theodora ... ... ... Miss Grace Hawthorne

Mr. Buchanan remarked at the close of the performance on Monday, that he had merely “adapted Sardou’s great play to the English stage.” He need not, however, have been so modest. The adaptation is exceedingly clever indeed; the adaptor of Tom Jones and Joseph’s Sweetheart is to be congratulated on having scored another success out of quite as difficult materials. In its present form Théodora is a drama ingeniously constructed of strong dramatic interest and considerable literary merit. Théodora cannot be said to be an elevating subject for stage treatment, but Mr. Buchanan has divested her of much that would be odious, and has given us instead a woman, if a bad one, tender and passionate in love, bitter in hate, sensual to an extent, and greatly diplomatic. Such is his Théodora. Another strongly-drawn character is the young Greek, Andreas, full of patriotic fire and athirst for vengeance. On the shoulders of these two falls the burden of the play, which in its present form may be briefly described as follows:—The scene opens in a reception room in the palace of Justinian, where his consort Théodora, holds audience. She dismisses her court, converses with Antonina, her friend, who acknowledges to the Empress that she has gained her love by the use of magic philtres, concerning which old Tamyris knows the secret. Théodora, longing to be back in her old haunts, visits Tamyris at the hippodrome, and obtains from her a promise to supply her (Théodora) with the magic philtres which shall revive her husband’s love for her. The house of Andreas is the next scene, where a conspiracy is ripe for dethroning the Emperor. It is here that Andreas tells them of a woman he has saved from death during an earthquake—a woman whom he loves, and who visits him nightly, one Myrta by name. To her he partly discloses the plans of the conspirators. Myrta (or Théodora, for such she is) rushes off. The next scene is the palace. The Empress warns the Emperor of his danger, and all preparations are made for the arrest of the conspirators. Marcellus enters, is immediately seized; he shouts to Andreas to fly. Théodora, hearing Andreas coming, rushes to the door, tells Antonina to shout that Marcellus is dead, and stops anyone from leaving the chamber; thus Andreas escapes. Marcellus is dragged forth, and is about to undergo the torture when Théodora interferes. Marcellus begs her to stab him, which she, fearful lest he should betray her lover, in a fit of frenzy, does. The fourth act shows us their majesties at the hippodrome, where Andreas openly insults Théodora; he is arrested and thrown down at her feet. Again the Empress saves him, only, however, to be reviled by him. She, determined to regain his love, administers the magic philtres to him, not knowing that Tamyris, thinking they were to be given to the Emperor, had poisoned them. Thus Théodora kills her old lover. The Emperor, now fully conscious of his Consort’s guilt, accuses her of her faithlessness, which she acknowledges, and the executioner is about to despatch her when she drains the poisoned philtres and falls dead over Andreas’ body.

The piece is admirably mounted, the scenery being described as that used at the original production at the Porte St. Martin Theatre, whilst the dressing is rich in the extreme. Of the acting, Miss Grace Hawthorne’s Théodora is at all points carefully studied, and generally artistic, although wanting in power and tragic depth. It is undoubtedly her best effort up to the present time. Mr. Fuller Mellish makes a decided hit as the young Greek, Andreas; on Monday he carried several scenes shoulder high to success. Miss Dolores Drummond is a characteristic Tamyris, and Antonina is pleasingly portrayed by Miss Clarice Trevor. Mr. Thalberg will doubtless make more of his Marcellus. Mr. T. P. Haynes as Euphratas evidently has not quite caught the spirit of the part. Mr. Arthur Lyle has a fine stage presence, and when he gets settled down into the rôle of the Emperor he will no doubt make a sound impersonation of it. Belisarius, in Mr. Cecil Morton Yorke’s hands, receives good treatment, whilst a line of praise must be accorded Mr. Harcourt Beatty as Timocles, Mr. G. W. Cockburn as Agathon, and Mr. Charles Macdona as Caribert, for making small parts, stand out well and firmly. The remaining characters are in safe hands. It should be mentioned that the second act was so vigorously played by the conspirators on Monday that it drew forth the most hearty applause of the evening.

___

The Era (23 November, 1889)

“THEODORA” AT BRIGHTON.

_____

Adapted from M. Victorien Sardou’s Masterpiece,

by Mr Robert Buchanan, produced for the First Time in

English at the Brighton Theatre, on Monday, Nov. 18th, 1889.

Justinian ... ... ... Mr ARTHUR STYE

Belisarius ... ... ... Mr CECIL MORTON YORKE

Euphratas ... ... ... Mr T. P. HAYNES

Marcellus ... ... ... Mr THALBERG

Caribert ... ... ... Mr CHARLES MACDONA

Andreas ... ... ... Mr FULLER MELLISH

Michael ... ... ... Miss ROSIE LEWIS

Timocles ... ... ... Mr HARCOURT BEATTY

Agathon ... ... ... Mr GEO. W. COCKBURN

Taber ... ... ... Mr THOS. BLACKLOCK

Styrax ... ... ... Mr HENRY GRAY DOLBY

The Executioner ... Mr CHARLES FORSEY

Mundus ... ... ... Mr JOHN DRUMMOND

Priscus ... ... ... Mr HENRY LUDLOW

Orythes ... ... ... Mr JAMES FERGUSON

Amron ... ... ... Mr GEO. LAKE GRANGE

Calchas ... ... ... Mr VALENTINE OSTLERE

First Lord ... ... ... Mr HARRIS LAWRENCE

Second Lord ... ... Mr CHARLES ANSON

Third Lord ... ... ... Mr FRANK PIERSON

Fourth Lord ... ... Mr WILLIAM BRUCE

Chief of the Ostiaires ... Mr GERALD HARLEY

Antonina ... ... ... Miss CLARICE TREVOR

Tamyris ... ... ... Miss DOLORES DRUMMOND

Macedonia ... ... ... Miss ANNIE LLOYD

Callerhoe ... ... ... Miss KATIE RAYNE

Iphis ... ... ... Miss MARIE STUART

Ixia ... ... ... Miss DORA DE WYNTON

Columba ... ... ... Miss ALICE DE WYNTON

Zena ... ... ... Miss WALNER

Theodora ... ... ... Miss GRACE HAWTHORNE

(FROM OUR OWN CORRESPONDENT.)

A large audience in the Brighton Theatre on Monday evening gave an enthusiastic reception to Mr Robert Buchanan’s version of Théodora, as represented by Miss Grace Hawthorne and her company. The work was splendidly staged; the scenery may justly be termed magnificent; while the costumes have never, in richness and elaborate workmanship, been excelled on the Brighton stage. Mr Robert Buchanan has displayed his best powers in his adaptation. The story, which has been rendered familiar by the inimitable representations in French by Madame Sarah Bernhardt and company, is worked out in five acts, the last and third of which comprise two tableaux. In the opening tableau, the passionate and unscrupulous Théodora, formerly a circus performer, and now wife of the Emperor Justinian, holds a reception in the palace. Here, in the midst of barbaric splendour, and surrounded by all the attributes of power and wealth, it is at once evident that she is an autocrat. In strong and effective contrast comes the second tableau—the Home of the Gladiators—where Théodora, visiting the witch, Tamyris, renews her acquaintance with her former Bohemian friends. The main purpose of her visit is, however, to secure from Tamyris a potion that shall enable her to strengthen the love of Justinian for her. Still greater is the dramatic interest in the second act, where, in the house of Andreas, a young Greek, it is seen that a plot is being concocted for the dethronement of the Emperor and the destruction of his hated consort. Andreas reveals to his co-conspirators his intense love for one Myrta, whom he regards as a young widow, and one—she is no less than Théodora—whom he has saved from the perils of an earthquake. Théodora visits him, and the two lovers plight their troth, only, however, to be disturbed by a ribald song, sung by passing conspirators, having for its theme the execration of the Empress herself. In the third act, at the Emperor’s palace, Andreas and his friend Marcellus, an officer of the bodyguard, enter the royal chamber, hoping to seize the monarch. Théodora had, however, taken measures to surprise the conspirators. Marcellus is overpowered, but Andreas, whose voice is recognised by Théodora, is enabled to escape. Justinian, determined to learn, by torture, the name of Marcellus’s accomplice, is frustrated by Théodora, who, undertaking to privately interview the captured conspirator, stabs him, at his own request, to the heart with the stiletto she wears in her hair. Andreas learns from the stiletto the identity of the Empress with the murderess of his friend; and when Théodora, whom he still regards as Myrta, visits him in the gardens of Styrax, she learns that her lover has determined to avenge Marcellus’s death. The Empress induces him to promise he will not leave his house till she again calls upon him; but, learning from his associates that Myrta and the Empress are one and the same person, he resolves to visit the Hippodrome. There, in the fourth act, the accusations of his co-conspirators are verified, and Andreas proclaims the Empress, who raises her veil before the assembled thousands, as an adulteress. He is seized and is about to be executed when Théodora contrives his escape. In the last act, at the palace, Tamyris gives Théodora the promised potion. The witch, sharing the hatred of the mob for the Emperor, has poisoned the potion. Andreas is immediately afterwards brought wounded into Théodora’s presence. Her old love for the young Greek manifests itself, but Andreas repels her advances. Believing the potion will restore his affection to her, she administers it to him and, while she is horrified to find she has killed him, Justinian arrives. The Emperor, who has discovered the unfaithfulness of his wife, orders her strangulation, when Théodora also partakes of the potion and falls dead upon the body of Andreas. The piece, for a first night’s performance, ran with smoothness, and there was a manifest improvement on the second night.

Miss Grace Hawthorne gave us some fairly good acting as Théodora. Vigorous and impassioned fervour were at times wanting, but, in the lighter portions of her trying impersonations, she achieved a moderate success. In the second tableau of the first act, when visiting Tamyris at the home of the gladiators she showed vivacity fully in harmony with the Bohemian surroundings. She was perhaps seen at her best in the second act, when, in her love passages with Andreas, she unfolded her wealth of affection for the young Greek, and raised doubts in his mind only to quell them by the warmest protestations of undying love. She was also seen to advantage in her hurried interview with the captured Marcellus, and aroused the enthusiasm of the audience by her acting in the closing death scene. Mr Fuller Mellish was highly successful as Andreas. The contrasts of deep love for Myrta and intense hatred for the faithless Empress were admirably given. His impassioned fervour when winning the love of the unknown Myrta, no less than his strong emotional acting when learning the identity of his unscrupulous charmer with the faithless Empress, won enthusiastic applause. Mr Arthur Stye lacked dignity as Justinian the Emperor. Mr Thalberg was effective as Marcellus. Mr Cecil Morton Yorke proved a capable Belisarius. Miss Dolores Drummond was admirable as Tamyris. Miss Clarice Trevor made the most of the part of Antonina. Mr Charles Macdona was a praiseworthy Caribert. On the fall of the curtain Mr Robert Buchanan, in response to calls for the “author,” came before the footlights and briefly said, “I have merely adapted the work to the English stage, but I shall at once acquaint M. Sardou with the generous recognition which you have given his play.”

___

The Brighton Herald (23 November, 1889 - p.3)

THE THEATRE.

AN ENGLISH VERSION OF “THEODORA.”

The Brighton Theatre has been selected this week for the production for the first time in England of a version in English of M. Sardou’s great play, Théodora, in which Madame Bernhardt achieved in Paris one of her many striking successes. The English adaptation is by Mr Robert Buchanan, whose services to the English stage entitle him always to respectful consideration; whilst the Company is led by Miss Grace Hawthorne. The piece has won a succès d’estime,—nothing more. The enterprise doubtless was well-meant, and in many respects is a dramatic achievement creditable to all concerned in it. Mr Buchanan has done his part with signal ability; the scenic accessories and dresses are on a sumptuous scale; the acting is meritorious. These things go a long way towards winning success, but they do not surmount the foremost objection to the play that, as a reflection of human emotions, it is destitute of any redeeming quality. It is not easy to think that such a drama will long remain on the English stage. Those who have witnessed it this week, and have been fascinated by the gorgeous scenery, the sensuous lights of the Bosphorus and the arabesques and prodigality of colour and ornament of the Byzantium of the sixth century, or have been moved by the voluptuous desires of the chief figures, or have been stirred by the exciting scenes of the revolt of the Greeks, have wondered whether this, indeed, was a play worthy of the efforts that have been made to place it on the stage with lavish magnificence and worthy also of the reputation of so distinguished a playwright as M. Sardou. The answer must, we fancy, be in the negative. As a splendid pageant, as a wonderful re-creation of a long past era, Théodora is of great interest. As a play it is remarkable as an audacious effort of realism, but marred by the absence, if we except the patriotic instinct of the conspirators, by any quality of innocence or graciousness. From beginning to end it reeks with licentiousness, frivolity, and turbulence. There is absolutely no relief. It is a sinister picture in which human passions are shown at their worst. Théodora herself, as M. Sardou pictures her, has some moments of a better sense. She delights to imagine herself loved for herself alone, and the seeming purity of her passion for Andreas, the Greek, might be held (though it is a dangerous proposition to lay down) to sanctify it. She talks, indeed, a good deal about “love,” and hints that with other opportunities she might have been a better woman. This form of reasoning is in vogue with French writers just now. It is their application of the doctrine of environment to the human subject, and it is specious enough to make an audience somewhat unmindful of the fact that such language is a little out-of-place in the mouth of a married woman who seeks midnight adventures and gives herself the luxury of being embraced by a man who is not her husband. Under certain circumstances Théodora’s defence of herself might be acceptable. But in her case, even as presented by M. Sardou, it savours of a very pernicious form of cant. The Théodora of history, most infamous of women, even if her least severe critics are to be believed, would never have dreamt of resorting to it. It is needless to say that even a French playwright, with a keen sense of realism in human emotion, shrinks from picturing Théodora exactly as she has been painted. Nevertheless, even in the modified form in which she is brought on the stage, the arguments of a woman who has been “betrayed” sound strangely when coming from the lips of a character who cheerfully relinquishes herself to the fascination of an intrigue of the kind that is found in M. Sardou’s startling and sombre drama. Théodora’s passion, therefore, which might on some theories be a bright and innocent flower in the desert, does not afford any real relief, and we look elsewhere, but in vain, for anything that can be used as a set-off to an odious, if brilliant, reflection of the vice, ferocity, and bloodshed displayed in this portentous drama. This defect, we imagine, will be fatal to its success. Cynical people may tell us that a drama can manage without such a contrast, that the new drama will present life as it is without the restraint of the conventional types of virtue and villainy, that it is enough to paint people as they are or were. That remains to be proved. Dramatic conventionalities of this sort may be put aside when some powerful motives are forthcoming to set the play going. But the bizarre wickedness in Théodora, the guilty passion of the chief figure, the not less guilty passion of the Greek, who sacrifices his mistress, not because she is the wife of Justinian the Emperor, but because she is the wife of Justinian the Tyrant, the scenes of cruelty, the suggestion of wholesale butchery, and the pervading atmosphere of intrigue and debauchery,—in none of this can be found motives sufficient to establish a drama of this kind. The audience may be amazed at its splendour and impressed by its sense of size and magnificence (the former cleverly suggested, the latter real and unmistakeable), but when all is over, when Théodora falls, self-poisoned, on the corpse of her lover, it is not with feelings of compassion or sympathy that the audience sees the end of the drama, but rather with a feeling of relief as if a brilliant nightmare had been dissipated. There are points of likeness between Théodora and Claudian, which justify a comparison or a contrast between the two. These points will suggest themselves readily, but it enough to claim here that the reason why Claudian succeeded was because it contained those very qualities which we contend are absent from this newer play.

Though we can scarcely believe that Théodora will add much to M. Sardou’s reputation, or be specially welcomed on the English stage, it contains some powerful situations. The play opens in a reception room in the Palace of Justinian, where Théodora, the young and beautiful Empress, raised from the arena of the hippodrome to share the throne of the Emperor, gives audience to Caribert, an emissary from the Franks, and assists in hoodwinking the General Belisarius about the misconduct of his wife, one of the Empress’s favourite women. The next scene passes in the home of the gladiators, in the arches beneath the Imperial box at the hippodrome, where in the course of her nightly search for adventures Théodora presents herself to an old circus woman, an Egyptian, Tamyris by name, from whom she asks for a magic potion to win back the love of her husband. These two scenes, “tableaux” they are called in the programme, serve as a prologue. The real action starts in the house of Andreas, the Greek, where a group of conspirators meet to arrange a rising against the Emperor. Before the sterner business of politics is discussed, the conversation turns on the love affair in which the friends of Andreas are amused to find he has become entangled. Making no denial of it, he frankly tells them how one night, when an earthquake rent the city, a woman, young and beautiful, a widow whose name she said was Myrta, clung to him for protection, and how their acquaintance had ripened into love. Before they part, the friends find that the time for revolt is hastening; a faction fight between the Blues and the Greens had ended in the death of one of the partisans, whose corpse is being even then carried round the city amid insulting songs aimed at the dissolute Théodora. It is arranged that the blow shall be struck at once. Marcellus, one of the conspirators, an officer in Justinian’s body-guard, arranges that he and Andreas, disguised as a soldier, shall make their way to the Emperor’s sleeping-room, gag him, and carry him off. Even as the conspirators disperse, Théodora, the Myrta of the earthquake, enters the Greek’s garden. The love-making which follows resembles in some degree a critical passage before the catastrophe in Fédora. Théodora asks Andreas to suppose this and to suppose that, to imagine that she is no widow but a wife,—would he love her still? Like better and worse men before and after him, Andreas at first hesitates and then abandons himself to the pleasure of loving. The descent of Avernus is so easy when the blood is young and women are beautiful. Wife or widow, maid or matron, it is all one to him, and the pair are locked in each other’s arms. Théodora gives herself up to the intoxication of the moment. They will go to Greece, to Athens, and spend their days in idyllic dreams of love. Then comes a murmur from the streets. There is danger in the air. Infected by the fever of the conspiracy, Andreas has already hinted that a desperate enterprise is on foot, but checks himself before saying too much even to the woman he adores. But the noise in the street recalls the stern business that is to be done. He launches into a denunciation of the tyrant Emperor and his adulterous wife. It is a complex picture, for he has the woman in his arms, whilst he curses the Empress with his lips. As for Théodora, she rests on his arm in mute bewilderment. The vision of idyllic days in Athens is dispelled at a blow, and in its place rises the vision of a revolted capital, thirsting for vengeance,. The whispers of love are hushed in the shouts of a ribald chorus, with the mocking desperate refrain of “Théodora-ra-ra,” sounding like a death-knell. And Andreas sits there, all unconscious. It is a powerful situation, very perfectly presented. Later on comes the attack on the Emperor. It fails, of course. Théodora has learned enough to put the Palace on its guard. Marcellus is caught red-handed. The alarm is given, but Théodora saves her lover by bolting the door through which he is to enter. Marcellus is brought in gagged and senseless. He is to be put to the torture in order that his accomplices may be known. The name of “Andreas” has been heard. What does he know of him? The torturers are ready with pins of red-hot steel to be thrust into his neck. Desperate to gain time, Théodora undertakes to make him speak if he is left with her alone. Marcellus is determined to perish with the secret of the plot. Théodora warns him that he cannot possibly endure the agonies of the torture that awaits him. “Then,” says Marcellus, “kill me yourself; if not, I denounce you and your lover.” Théodora protests that she has no weapon, and to seek one would arouse suspicion. Marcellus tells her she has a stiletto in her hair. Yes, that is so; her hand wanders to her head, and then pauses,—it is a moment of terrific irresolution. Marcellus dead, her secret is safe; Marcellus living, her secret will be extorted from him and his own life wrung from him by the fiendish practices of the torture-chamber. Other women might shrink from the desperate alternative, but Théodora is not as other women are. She asks Marcellus where she shall strike, and he guides her hand to his left breast and asks her if she can feel where his heart beats. A flash of metal, and Théodora has stabbed him dead. A hideous incident, probably unparalleled on the stage. The failure to kidnap the Emperor does not end the rising. Next day there is a great festival at the hippodrome. A hundred thousand of the citizens are present. The Emperor and his wife are received in ominous silence; then comes a murmur, and at last a hoarse demand that the Empress shall unveil. Driven to bay, Théodora tears the veil from her, and faces the multitude. There is a yell of execration, the tumult becomes articulate, and loud above the hoarse roar of voices comes the stinging taunt of “Adulteress.” Théodora has heard it before and can endure it again, but now there is something worse than hard words. The populace is bent on mischief. The arena is overrun. Foremost in the outbreak is Andreas. The Imperial Guards are at work, killing and wounding, the arena runs with blood, Andreas is cut down. In a state of panic Justinian orders the gates of the Imperial box to be closed. Then Andreas is brought forth. Théodora in her real colours is at last before him, and he denounces her. Justinian orders the executioner to advance, Andreas is thrown down, and the gigantic axe of the headsman is poised over him. Again Théodora interposes. Andreas had assailed her, let her, she asks, find his punishment; and so the Greek is saved once more. The story hastens to a close. The revolt is crushed out with merciless severity. Andreas is brought to the Palace by Théodora’s orders. She is still madly in love with him, if such a passion as her’s is “love” at all, but he loathes her very presence. There is one resource left. The Egyptian has supplied her with a love potion; she will use it on Andreas. But Tamyris has had her own game to play. Maddened by her son being put to death by Justinian’s orders, she has given Théodora a flask of poison. The “love potion” does its work quickly, and Andreas falls dead on the couch. Desperate at losing her lover, and doubly desperate at her husband ordering her to be strangled, Théodora recognises that the end has come, and, swallowing a dose of poison, falls dead across the body of the ill-fated Andreas.

Such is the story in little, and it will, we think, be admitted that a more gloomy piece of work has rarely been provided for the stage. It affords magnificent but morbid opportunities for the leading character. To say that Miss Grace Hawthorne fully rose to all of these would be incorrect. She played at times with conspicuous sensibility, considerable spirit, and not a little power, but the laborious effort, involving a wide variety of emotional display, was somewhat beyond her range of expression. In the scene in the gladiators’ home she was successful, still more so in the scene with Andreas in the second act, particularly in the inarticulate play of feeling when she hears the revolutionary chorus, and again at the death of Marcellus, in which the hesitation and ultimate decision were adequately expressed. The closing scene was less successful. Taken altogether, Miss Hawthorne showed a fine appreciation of the character, and, if she did not always convey an adequate impression, she deserves no little praise for a gallant attempt to master an ambitious and a most difficult part. She is supported by a very efficient Company. Mr Fuller Mellish impersonates Andreas with spirit and intelligence. If he can, he must learn the art of sitting with more grace, no doubt a little difficult for an Englishman in a Greek dress. The other conspirators were represented by Mr H. Beatty, Mr Geo. W. Cockburn (especially good), and Mr T. Blacklock, those who had most to do doing it best. They worked well together, and their scenes (notably in the second act) have been warmly and deservedly applauded. The Emperor is well played by Mr Arthur Stye; Mr C. M. Yorke gives a vigorous representation of Belisarius; Mr T. P. Haynes supplies a modicum of humour as Euphratas, chief of the Palace eunuchs; and Mr Thalberg is excellent as Marcellus. The other characters of a heavy cast have been adequately filled; indeed, the acting throughout is, with some minor exceptions, spirited and intelligent. We understand that on the first night the play was so cordially received that Mr Buchanan came forward and promised that news of the success of the drama should be sent to M. Sardou.

_____

Another writer says:—Ancient history is now so seldom used for dramatic purposes that a brilliant tragedy such as Théodora should be interesting to all students both of literature and of history. It is only within the present century that the Byzantine Empire has received the attention it deserves, and that its services to civilisation during the descent of the northern nations upon the Roman Empire have been appreciated. The tone of Mr E. A. Freeman’s references to the Byzantine Empire, compared with the part of Gibbon’s History devoted to the same subject, is very much more favourable. This is partly due to the revived appreciation of early mediæval Art, which sprang directly from Constantinople and Ravenna. But even yet, comparatively few know more than the vaguest outlines of that remarkable history, and it is to be feared that the allusions in the drama to the rebuilding of St. Sophia, and to the factions of the Blues and the Greens, were not understood by many. The historical material has been very freely dealt with, and modern sentiments have, of course, been introduced, but on the whole the drama gives an instructive and a correct view of the age of Justinian. The idea of a Gaulish warrior of the period (Caribert) refusing to participate in a massacre was doubtless welcome to the Parisian audiences for whom Sardou wrote Théodora, but it is not in keeping with the character of Gaulish or any other warriors till the last two or three centuries. The quality of mercy, unknown in Europe till the introduction of Christianity, and not very effective for ages subsequently, disappeared whenever a town was stormed or a revolt crushed, whether at Durham or Jerusalem, at Limoges or Rotterdam, at Magdeburg or Drogheda. But it is now almost impossible for an European to realise the idea of a conqueror continuing merciless towards defeated enemies; and this change of feeling renders it almost impossible to use ancient history as dramatic material without the introduction of palpably incongruous sentiments, such as the one we have instanced. Perhaps the modern belief in “the struggle for existence” and “the survival of the fittest” may bring about a return to the old pitiless cruelty, even as it may still be seen in China and Ashantee.

The character of Justinian’s low-born Empress has been painted in the blackest colours by Procopius (we beg Mr Freeman’s pardon, Prokôpius), and her adventures both before and after she attained the throne have brought upon her the foulest accusations ever breathed against a woman. Faction, heightened by sectarian animosity, was always rampant in the early ages of the Byzantine Empire; and the historian of the period was Théodora’s political opponent. She has thus acquired a reputation which she doubtless did not entirely deserve. Some one may feel it his duty to represent her as a grossly maligned, well-meaning person, a fate which has lately happened to many who have hitherto been regarded as monsters, to Nero and Robespierre, and Henry VIII. However, her legendary character, true or untrue, is a grand subject for a really great writer; and a clever, practical dramatist, as M. Sardou is, could hardly miss making a most effective tragedy on this theme. He has naturally neglected every other historical personage for the purpose of concentrating interest on the heroine. The Emperor Justinian is but vaguely and slightly drawn, and still less attention has been devoted to that hero who was known to Mr Boffin as “Bully Sawyers,” but to the world in general as Belisarius. Every opportunity is given for splendour of scenery and decoration, and the piece is lavishly mounted, at a cost, it has been stated, of £5,000. The first performance on Monday night was an unqualified success, most parts of the Theatre being crowded; and, as the piece had been very thoroughly rehearsed, nothing was wanting to ensure a most favourable reception.

Mr. J. L. Toole will appear next week in a round of his favourite characters.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

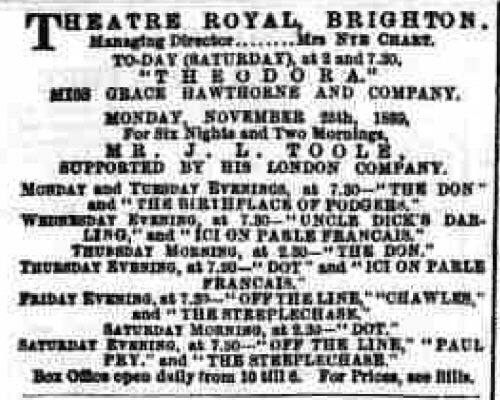

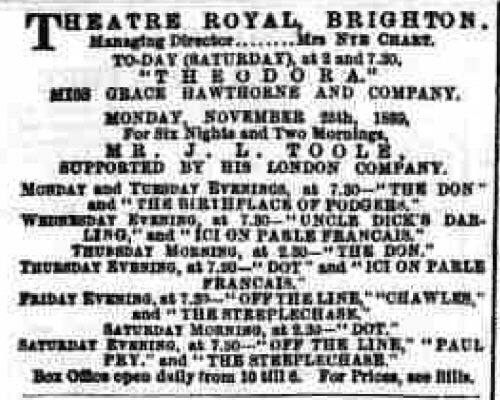

[Advert from The Brighton Herald (23 November, 1889 - p.3).]

The Northampton Mercury (23 November, 1889 - p.9)

LADIES’ COLUMN.

_____

. . .

This week Miss Grace Hawthorne is giving the Brighton public the first representation of Sardou’s “Théodora,” the English translation of which has been written by Mr. Robert Buchanan. Miss Hawthorne studied the part in Paris, under the author while she was having the dresses prepared for her début in England. Of these dresses a whole chapter might be written, for nothing that has yet been produced on the English stage approaches the costumes prepared for “Théodora.” They are two hundred in number, and have cost nearly £5,000. Ladies will be interested to know that many of the bodices are made of silk stockingette, a material hitherto considered outside all considerations for evening bodices. The effect of perfect moulding given by stockingette could scarcely be produced in any other textile. Over the bodices the gauze draperies, heavily covered with embroidery in gold, silver, and pearls, hangs artistically. The stuffs for the dresses were in some instances specially woven for the purpose, but all that are embroidered were carefully thought out and worked to order. Formerly all embroidery was done on heavy, solid stuffs, thick silks, velvet, or plush. Now it is done on the softest, most clinging of gauzy materials, chiefly crêpe. All the brides of recent days had the fronts of their dresses draped with these beautiful embroideries done in silver, white silk, and pearls. Instead of Chinese crêpe Miss Hawthorne’s dresses are worked upon and hung with Japanese, which has greater staying power, and upholds the embroidery without looking heavy or less diaphanous. The dresses worn by the Princess of Wales, which dazzled the eyes of the simple Athenians, were not only embroidered in silver, but draped in these thin crêpes, all sparkling with crystal and silver. The pale blue dress worn at the nuptial ball, and the wonderful diamond tiara, necklet, and bracelets worn with it, will be talked of in Greece for many a day to come when the story of the wedding of the heir to the Throne with the German Princess has passed into history.

___

The Referee (24 November, 1889 - pp.2-3)

Before a full and favourable house Miss Grace Hawthorne and company started the new “Théodora” at Brighton on Monday. Mr. Robert Buchanan, who seems to be a sort of adapter-in-chief for the English stage just now, has prepared a version of what is called on the programme “M. Victorien Sardou’s masterpiece.” This is much better suited for English tastes and sympathies than said masterpiece would be if translated to the letter. "“Théodora” is a tragedy of Byzantium, after the “Lower Empire” period—temp. between 500 and 600 A.D.—and as played at Mrs. Nye Chart’s theatre is not without its memories and suggestions of Sheridan Knowles rather than Shakespeare, of Tobin, Fitzball, and various others who have gone to the periods of antiquity for their inspiration. Singularly enough, now that Watts Phillips’s merits are under discussion, Surreyside theatregoers may remember his play of “Theodora, Actress and Empress,” which, in point of date at all events, was a long way in front of Sardou. At Drury Lane or Her Majesty’s, with every advantage of spectacular effect, and the dazzling illusion peculiar to the richly-dressed and gorgeously-mounted pieces of modern days, the new “Théodora” would have great prospect of success. When produced at the Porte St. Martin all but five years ago, many critics were of opinion that magnificence of mise en scène had at least as much to do with its success as either the brilliance of M. Sardou’s dialogue or the greatness of Mme. Bernhardt’s acting. Great as this latter was, and always is, there were not wanting those who said it was scarcely equal to the demand made by any true portrayal of one of the most terrible creatures history possesses, the soft smooth wanton, the cruel blood-seeking tigress, Théodora, Justinian’s adulterous empress. Whether when the adaptation comes to London in its present comparatively simple and subdued guise it will astonish the Londoners, can be but matter of conjecture. Miss Grace Hawthorne plays the Bernhardt’s great part, and struggles bravely under the difficulties of so colossal an undertaking. Mr. Fuller Mellish is the Andreas of whom Théodora becomes desperately enamoured after having picked him up in one of her nightly rambles in search of the sort of amusement description of which is generally confined to the pages of Procopius and Theophanes, and in our own tongue to such outspoken historians as Mr. Silas Wegg’s great friend, the portly Gibbon. To keep to the classics while one’s hand is in, and snatch a metaphor therefrom, it may be said that Mr. Mellish in so important and heroic a part as that of Andreas resembles nothing so much as Patroclus when clad in the armour of Achilles. There are twenty-nine other name-parts in the play, besides a large number of “officers, lords-in-waiting, ostiaires, eunuchs,” &c., &c., which reminds me that Euphrates, chief of the eunuchs, is played with much unction by our old friend Tippy Haynes, who, I thought, had deserted the theatre to travel the music-halls. The short but powerful part of Tamyris, mother of Amron, the lion tamer (a sort of theatric Sandow-cum-Peter Jackson), is admirably well played by Miss Dolores Drummond. “Théodora” was very cleverly staged under the direction of Mr. W. H. Vernon.

___

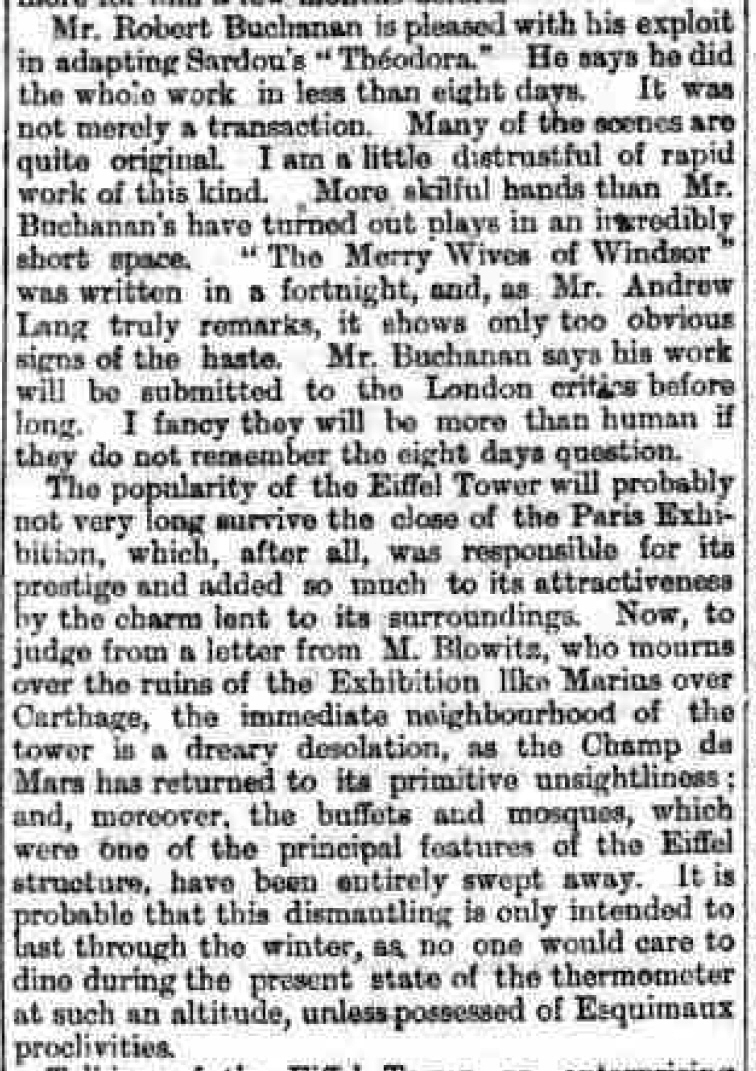

The Pall Mall Gazette (26 November, 1889 - p.1)

I am told that Mr. Robert Buchanan accomplished one of the quickest poetic feats on record when he took “Theodora” in hand the other day. A prose translation of the play was handed to him, and he proceeded to turn it into blank verse in the short space of five days. I shall be curious to see the result of this lightning literary performance.

___

The Stage (29 November, 1889 - p.7)

MANCHESTER

PRINCE’S (Manager, Mr. T. W. Charles; Acting Manager, Mr. Tom Manchester).—A very large and appreciative audience gathered here on Monday to witness the first performance in Manchester of Robert Buchanan’s adaptation, Theodora. The production is on a grand scale. Miss Grace Hawthorne’s impersonation is a meritorious one. In many ways her acting displays grace and power. Miss Clarice Trevor makes as much as may be of Antonina. Miss Dolores Drummond evinces much discretion in her rendering of Tamyris. Callirhoe is very well played by Miss Marie Stuart, Mr. Arthur Lyle is powerful and effective as Justinian. Belisarius is admirably rendered by Mr. Cecil Morton Yorke. Mr. T. P. Haynes gives a capable performance as Euphratas. Mr. Thalberg displays ability as the centurion Marcellus. Caribert is played with success by Mr. Charles Macdona. As the young Greek Andreas Mr. Fuller Mellish distinguished himself in no slight degree. His acting throughout is of high merit, and repeatedly secures the decided approval of the audience. Timocles, Agathon, and Taber are all well played by Messrs. Harcourt Beatty, George W. Cockburn, and Thomas Backlock. Other characters are efficiently represented. The scenery, &c., is also very effective.

___

The Lancashire Evening Post (29 November, 1889 - p.2)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

The Stage (21 March, 1890 - p.5)

LEEDS—GRAND (Sole Lessee, Mr. Wilson Barrett; Manager, Mr. Henry Hastings).—On Monday a full and enthusiastic house witnessed the performance of Robert Buchanan’s adaptation of M. Victorien Sardou’s Theodora, with Miss Grace Hawthorne in the title-rôle. No expense seems to have been spared in staging it, the scenery is beautiful and effective, the dresses are superb and appropriate, and the more prominent artists show ability far above the average. It is scarcely to be expected that Miss Hawthorne can throw into the piece that warmth of feeling or genuine self- abandonment characteristic of Sarah Bernhardt. Yet there were not wanting evidences of a true appreciation of the character of Theodora, and occasional flashes of true art manifested themselves to those who carefully watched Miss Hawthorne’s delineation. The visit to and the interview with the witch Tamyris, the love scene with Andreas, the death- scene of Marcellus, her imperious bearing before the Emperor when the secret of her illicit love was unmistakably proved, and the death of Andreas, and her self, were undoubtedly Miss Hawthorne’s best and most telling efforts, and won for her considerable applause. It is no easy task to delineate a character so pleasing in some aspects, so repulsive in others, as that of Theodora, and Miss Hawthorne may be congratulated on the success which marked her efforts. Mr. Cecil Morton York brings to the representation of his character of Justinian experience and wisdom, and depicted the imperious monarch with consummate taste and judgment. Mr. Alfred Harding’s Belisarius was exceedingly good. Mr. D. G. Longworth’s Euphratus (Chief of the Eunuchs) lost much of its good effect through the actor’s use of a nasal twang, which was most distressing. Mr. Charles Lander’s Marcellus was a marked success. Mr. Alfred B. Cross soon won the confidence and appreciation of the house, which he certainly earned by his delineation of Andreas. Mr. Cross has more than once shown undoubted ability on the stage, but never has he displayed his powers to such advantage as on Monday night. Tamyris was very ably portrayed by Miss Dolores Drummond, and the remaining parts were well filled.

___

The Scotsman (25 March, 1890 - p.4)

THEATRES.

The production of “Theodora” at the Theatre Royal, with Miss Grace Hawthorne as the heroine, drew out a large audience last evening. As adapted by Mr Robert Buchanan, the classic play of M. Sardou is one of absorbing interest, if at times somewhat repulsive in its tone. Miss Hawthorne’s Theodora is a wonderfully powerful delineation of a difficult part. The company supporting Miss Hawthorne is a very clever one. Theodora was very cordially received last night.

___

The Glasgow Herald (25 March, 1890 - p.4)

THE THEATRES.

___

ROYAL - “THEODORA.”

The English version, adapted by Mr Robert Buchanan, of M. Sardou’s “Theodora” was presented at the Royal last night by Miss Grace Hawthorne and a company specially selected to support her. When first produced in England a few months ago the play attracted considerable attention, and the very large audience that assembled in the theatre last night testified to the interest it has awakened on this side of the Border. The name of Madame Sarah Bernhardt is associated with the title rôle, and there was no doubt a widespread desire to witness the portrayal by an English actress of a character which the great French tragedienne has made one of her greatest creations. It is unnecessary to describe the play otherwise than briefly. The interest with which it abounds from the opening to the final scene centres around the career of a girl who, from her lowly origin as the child of a circus performer, has attained to the exalted position of wife of the Emperor Justinian. She wins the highest prize in the game of her infamous life, but even then she is unscrupulous, and in the end brings disaster to her husband, and a violent death to her lover and herself. The part, it is thus evident, is surrounded with difficulty. It is indeed an almost impossible creation, and to give it adequate embodiment in its multifarious lights and shadows—now delicate and sparkling as a summer sunbeam, anon shrouded in the depths of tragic gloom—is well-nigh an impossible task. Miss Hawthorne has set herself to it with a determination to do it at least approximate justice. And she succeeds to a degree which commands unbounded admiration. She has thought out and she presents a wonderfully complex and yet consistent character, and in its representation she impresses the audience not only with her ability to realise her own conception of the vicious and imperious woman, swayed by contending passions and emotions, but with the comprehensiveness of the study she seeks to develop. Her weakest point is her comedy. It was occasionally too flippant, with the result that the incisive sarcasm of the text was reduced to something akin to meaningless burlesque. Otherwise her acting was admirable. In the more intense scenes she excelled, and in the striking finale of the third act, where she strikes a fatal blow to save her lover from capture, and again at the close of the play, where she falls dead upon her lover’s bier, she reached a very high range of tragic power. Miss Hawthorne is ably supported. As Andreas, the lover of the Empress, Mr A. B. Cross takes a heavy share of the work, and performs it excellently well. Mr Lauder as Marcellus, Mr York as Justinian, and Mr Harding as Belisarius, also play their respective parts very creditably. Special mention must also be made of the part of Tamyris, splendidly represented by Miss Dolores Drummond. The piece was elaborately mounted and staged, and the richness of the dresses is also a noteworthy feature in the production. The play, which was received with great enthusiasm, will remain at the Royal for a fortnight.

___

The Times (6 May, 1890 - p.9)

PRINCESS’S THEATRE.

As Theodora was written expressly for Madame Sarah Bernhardt, it is not without a certain temerity that any English actress can attempt an embodiment of M. Sardou’s title character. Mrs. Bernard Beere has of late years acquired a sort of prescriptive right to enter upon such hazardous undertakings, and she has in general acquitted herself of her task remarkably well. It is now the turn of Miss Grace Hawthorne to array herself in the défroque of the great French actress. Last night an English version of Theodora was brought out at the Princess’s Theatre with Miss Hawthorne as the courtesan queen. Rashness was probably the mildest term which the experienced playgoer was prepared to apply to this enterprise, more especially as the play has not been in any sense adapted to the measure of the English actress, but bristles with situations designed to throw the personal characteristics of Madame Sarah Bernhardt into the strongest relief. The result was, however, a pleasant surprise. Miss Hawthorne grappled very successfully with her trying character, and earned the cordial applause of the house. In the more passionate scenes some indebtedness to her predecessor could be traced in her acting, but her impersonation was, on the whole, consistent, well-studied, and impressive. The closing incident has been altered. In the French play, the executioner enters with the bow-string in his hand, and Theodora bends her neck to her fate as the curtain falls. In the English version, the Empress defeats the purpose of her enemies by swallowing a dose of poison after the manner of M. Sardou’s heroines in other plays. A more picturesque, although more conventional, climax is thus provided. It enables Miss Hawthorne to lie down and die pathetically by the side of her dead lover Andreas. With Mr. Vernon as Justinian, and Mr. Leonard Boyne as Andreas, the general representation has ample justice done to it. The mounting is also appropriate. In fine, the performance is interesting and agreeable throughout.

___

The Standard (6 May, 1890 - p.3)

PRINCESS’S THEATRE.

It would certainly not occur to any one who had no very special interest in the work to describe Theodora as “M. Sardou’s masterpiece.” M. Sardou has written most admirable plays, but this is not one of them, it being, indeed, rather a study of character set in picturesque surroundings, than a drama constructed as the exceedingly ingenious French author can construct his works when he pleases. All the power of Madame Sarah Bernhardt could not save this long composition from becoming tedious at times, and it is a most daring venture for an English actress to follow in her steps. Miss Grace Hawthorne, however, last night essayed the character in a version prepared by Mr. Robert Buchanan, a play that has been talked of for a long time past, and was lately given at Brighton and elsewhere as a species of public rehearsal. On the whole, the experiment came out better than there had been any sound reason to anticipate. Miss Hawthorne had previously done nothing to give solid ground for the hope that she could come near to a realisation of the character of the vicious Empress; and though it is impossible conscientiously to advise her to pursue a line of Madame Bernhardt’s parts, at least it may be admitted that many things in last night’s performance were very creditably accomplished. Miss Hawthorne lacks the dignity which it must be assumed that Theodora had acquired at the date of the action of the play. The dramatist evidently intends that her Imperial greatness should be perceptible in the reception scene of the first act (or, to adopt the phraseology of the playbill, in the first tableau), and it is for the sake of contrast that he makes the Empress visit the humble home of the Sorceress, Tamyris, and share her frugal meal; but in truth, the companionship of these old friends suits the actress better than the stateliness of the palace life, and Mr. Buchanan has not hesitated to make his dialogue as colloquial as he supposes the situation requires, for from the blank verse of the former and subsequent scenes he makes Theodora drop to current vulgarism.

Some of the other broadly marked incidents Miss Hawthorne represents not without skill. Her love of Andreas has not, of course, the absorbing intensity that was exhibited by the original Theodora—a remark, perhaps, scarcely worth making; but she is earnest, if not so tragic as she should be, in the very forcible episode where, lest under the influence of the torture Marcellus should betray his friend and accomplice, she yields to his entreaties and stabs him with the pointed ornament worn in her hair. The English actress has not the art to lend sufficient variety to Theodora’s expression of love for Andreas and pleadings to him for pardon, and in the fifth act, the Imperial box at the Hippodrome, she fails to make clear the real nature of her sentiments towards her lover—the spectator unacquainted with the story would be unable to tell whether she was incensed and ready to let him die, or pitiful and eager to save. It is not altogether the fault of Mr. Leonard Boyne that Andreas should appear so half-hearted a lover. He is less occupied with the disguised Empress who visits him than with her plots and rebellions, always seeming in the most unflattering manner to be deeply occupied with something else when she is present. Mr. Boyne is over-vigorous in some of the scenes, notably in the series of shouts to which he gives vent on discovering the identity of the woman he is represented as loving; but altogether he plays with considerable power. Mr. Vernon presents a careful if not a very striking study of Justinian, and Mr. Cockburn is an effective Charibert. Mr. Charles Cartwright, though not well fitted as Marcellus, acts convincingly in his death scene of the third act. The play is very picturesquely mounted, the scenery has artistic merit, and the crowds are well-drilled and appropriately dressed. The audience showed an occasional tendency to accept certain episodes in other than a serious spirit; but, on the whole, the reception was very favourable.

___

The Morning Post (6 May, 1890 p.3)

PRINCESS’S THEATRE.

_____

The “Theodora” of M. Victorien Sardou was a bold venture on the English stage, but Mr. Robert Buchanan is not the dramatic author to be deterred by stage difficulties. He has successfully carried through enterprises in which many would have failed, and he has attacked the complications of M. Sardou’s “Theodora” with unquestionable courage and not without corresponding success. Some of the scenes in this play are calculated to dismay an adapter for the English stage; but Mr. Buchanan has accomplished an arduous task with credit to himself and advantage to the theatre. The conventional forms of stage work are so well worn, that playgoers must be glad to welcome novelty, even if it comes in the somewhat startling shape in which some of the incidents in “Theodora” present themselves. It is understood, of course, that Mr. Buchanan’s chief duty was to provide a striking character for Miss Grace Hawthorne, who, no longer contented with those domestic heroines she has hitherto played, aspired to follow in the footsteps of Madame Sarah Bernhardt herself. The Theodora of that gifted actress is well known, and, however strange and even repulsive the character of the heroine may appear, according to modern ideas, the remarkable ability of the great French tragedienne carried all before her, and made the most daring conception of M. Sardou enthralling, exciting, and even fascinating by the power and variety of effect introduced. The latest representative of the heroine must not be judged by the first. There are things Madame Sarah Bernhardt may say and do which would not be equally acceptable from an English actress, who is necessarily under greater restraint in working out her ideas of a character like this. The French actress thinks only of her part, and the effect she intends to produce in it. The English actress remembers her audience as well. This essential difference is well to be remembered in any estimate we form of the “Theodora” at the Princess’s. The play is given in six acts and seven tableaux, a formidable affair indeed, and made still more so by elaborate and picturesque scenery, processions, and other spectacular effects, dances, &c., a great effort being made to dazzle the spectator by the splendour and magnificence of the stage setting. The real dramatic matter of “Theodora” does not occupy so much of the play as might be imagined, but the incidents have all a picturesque setting, and the chief scenes are worked up into a series of tableaux very captivating to the lover of stage illusions. An outline of the chief situations introduces first of all the reception in the Palace of the Emperor Justinian, whose Empress was formerly a performer in the circus. Theodora has the fierce passions and the unscrupulous desires of one whose physical rather than mental attractions have raised her to the throne, and in the second tableau we have a glimpse of her real nature when, among the gladiators and other performers in the arena, Theodora revives the associations of her past life. Her chief object in thus visiting her old companions is to obtain from Tamyris, a sorceress, a love potion to increase the passion of Justinian. The second act takes place in the house of a Greek, Andreas, where a plot is being prepared to overthrow the Emperor and Theodora, who is hated by the people. Andreas is in love with a supposed widow, Myrta—no other than Theodora herself. He has saved her life during an earthquake. An interview takes place between the lovers, Andreas being still ignorant of Theodora’s real position, and in the third act he joins his friend Marcellus in an attempt to seize Justinian. It is defeated by Theodora, who recognising the voice of Andreas, permits him to escape, but Marcellus is taken captive. The Emperor endeavours to discover the companion of Marcellus, but this is prevented by Theodora, who, in an interview with the prisoner, kills him with the stiletto she carries in her hair. By means of this weapon Andreas discovers who has killed his friend, and he declares to the supposed Myrta his intention to avenge him. Discovering who Myrta really is, Andreas visits the arena and denounces Theodora in presence of the spectators. He is seized, but Theodora connives at his escape. The last act is again in the Palace of the Emperor, and the sorceress Tamyris brings the love potion Theodora had requested. But it is poisoned. An interview takes place between Theodora and Andreas, who treats her with disdain, and in the hope of regaining his love she gives him the potion. At this juncture the Emperor comes, and, discovering the infidelity of Theodora, orders her to be strangled; but the heroine takes the poisoned cup, and falls dead upon the body of her lover. In these passionate and tragic incidents the ability of Miss Grace Hawthorne was turned to good account. If there was not always the physical power to make the most of the strongest situations as a tragic actress of the highest gifts might have done, Miss Hawthorne, by her intelligence and judicious management, succeeded in giving an interesting study of the character; and the less exacting emotional scenes were rendered with much effect. The forced gaiety of the circus performer when among her old companions was natural and consistent, and Miss Hawthorne gave no little tenderness and passion to the scenes with Andreas. In the death scene Miss Hawthorne was seen to greater advantage than in any other character she has played. The actress takes her own view of the scene and situation, and makes it fairly impressive. As Andreas Mr. Leonard Boyne acted with the requisite sentiment and passion. The impulsive nature of the young Greek, the most heroic personage in the play, was well depicted, and few actors of the day would have made so much of the character. Mr. W. H. Vernon represented the Emperor with force and dignity, and he had also done the management good service in personally superintending the production of the play. The counsel of so intelligent and experienced an actor was of great value. Mr. Cartwright played the ill-fated Marcellus with considerable effect, and Mr. Cecil Morton York deserved praise as Belisarius. As Tamyris, the Sorceress, Miss Dolores Drummond acted with the force and energy she has so often displayed in parts of this kind. Miss Clarice Trevor successfully represented Antonina, and the same may be said of Miss Marie Stuart’s Callirhoe; and many of the smaller characters were efficiently sustained. The splendid stage pictures were greeted with enthusiastic applause, and the efforts of the performers were fully acknowledged. At the fall of the curtain Mr. Vernon first addressed the house, not being aware that Mr. Buchanan was present. That gentleman, however, came forward and briefly thanked the audience on behalf, as he explained, of M. Sardou, he being only the adapter.

___

Pall Mall Gazette (6 May, 1890 - p.1)

The most amusing incident at the Princess’s Theatre last night occurred after the curtain had fallen. Vague and indistinct shouts were heard from the pit and gallery, and it was an open question whether “Hawthorne!” or “Author!”—emphasized with an aspirate—was the cry. Matters were eventually compromised by both Mr. Robert Buchanan and “Theodora” taking a well-earned “call.”

___

(p.2)

Music and the Theatres.

“THEODORA” AT THE PRINCESS’S.