|

Play List: 4. Corinne 7. The Mormons 9. Lucy Brandon 10. Storm-Beaten 11. Lady Clare 13. Bachelors 14. Constance 15. Lottie 16. Agnes 17. Alone in London 18. Sophia 19. Fascination 20. The Blue Bells of Scotland 21. Partners 24. Angelina! 25. The Old Home 26. A Man’s Shadow 27. Theodora 29. Clarissa 30. Miss Tomboy 32. Sweet Nancy 33. The English Rose 36. Marmion 37. The Gifted Lady 38. The Trumpet Call 39. Squire Kate 40. The White Rose 42. The Black Domino 44. The Charlatan 45. Dick Sheridan 47. Lady Gladys 48. The Strange Adventures of Miss Brown 49. The Romance of the Shopwalker 52. Two Little Maids from School ___ |

|

ROBERT WILLIAMS BUCHANAN (1841 - 1901) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

THEATRE REVIEWS 22. Joseph’s Sweetheart (1888)

Joseph’s Sweetheart |

|

||||||||||

|

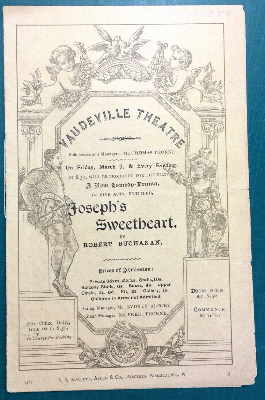

[Programme for Joseph’s Sweetheart at the Vaudeville Theatre.]

The Stage (2 March, 1888 - p.13) Titles of new plays are so frequently altered at the last moment that it is with a feeling of doubt that I mention that Robert Buchanan’s new play for the Vaudeville is called Joseph’s Sweetheart. By-the-bye, will not this name suggest to many who do not know the source of Buchanan’s plot the incident in the lives of Joseph and of Potiphar’s wife? ___

The Graphic (3 March, 1888) Joseph’s Sweetheart—such is the title which Mr. Robert Buchanan has given to his new comedy based on Fielding’s “Adventures of Joseph Andrews”—is in active preparation at the VAUDEVILLE. Its successive scenes, spread over five acts, will, it is expected, present many striking pictures of life and manners in the Hogathian days of King George II. Joseph’s “sweetheart” is, of course, Fanny. She will be played by the fascinating Miss Kate Rorke, who, by the way, is to marry, next summer, Mr. Gardiner, the popular actor who played the hero in Pleasure at Drury Lane. This is as it should be—that is to say, clever actresses should marry actors, and not peers of the realm and such haughty folk, who generally require them to forswear the stage. Here let us note that Mr. Thomas Thorne plays Parson Adams, Mr. Conway Joseph, Miss Eliza Johnstone Mrs. Slipslop, and Mr. F. Thorne Llewellyn—a character for whose introduction into the story Mr. Buchanan’s invention alone is responsible. ___

The Times (9 March, 1888 - p.10) THE THEATRES. VAUDEVILLE. Mr. Robert Buchanan’s second adaptation of Fielding, Joseph’s Sweetheart, was brought out at the Vaudeville yesterday afternoon and proved to be a worthy pendant to Sophia, whose success, in all probability, it will rival. As Sophia was a version of “Tom Jones,” so the present play tells the story of “Joseph Andrews,” with improvements suggested by the conditions of dramatic effect and also, we may add, by the improved tone of polite conversation. To quote an “author’s note” on the playbill, Joseph’s Sweetheart is “rather a play utilizing some of Fielding’s characters than a dramatization of Fielding’s story.” It is Mr. Robert Buchanan’s good fortune to have perceived great dramatic potentialities in a novel hitherto disdained by the adapter; and a more wholesome, more vigorous, more interesting, more enjoyable play than he has fashioned out of it the public could not wish to see. The success of yesterday’s performance was unequivocal. That fielding is no longer read by the masses is not a matter likely to affect the popularity of Joseph’s Sweetheart in the smallest degree. The spectator is not called upon to brush up his knowledge of the original in order to understand either the adapter’s characters or his situations. Clear and straightforward in construction, the play tells its own story, and its pulse, so to speak, beats throughout with a steady, healthy throb. As his mainspring of action Mr. Buchanan has given prominence to the jealous vindictiveness of Lady Booby toward Joseph Andrews and his rustic sweetheart, Fanny Goodwill, whose abduction by the scented dandy and libertine, Lord Fellamar, is planned and carried out at her instigation. “Hell hath no fury like a woman scorned.” Lady Booby gives a pointed illustration of the axiom. Her passion for her erstwhile lackey, who is subsequently found to be of aristocratic birth and who has spurned her advances, turns into a hate that knows no bounds. Her project of revenge being foiled, for the innocent Fanny is rescued from her ravisher’s clutches at a night fête in Ranelagh-gardens, she declines to accept the inevitable, and at the close of the fifth act, when the happiness of the lovers is assured, she leaves the stage cursing them. It is a terrible picture which is thus drawn of a jealous woman’s fury and implacability, and Miss Vane, who plays Lady Booby, does the fullest justice to it, aided as she is by a handsome and imposing presence. Lest invidious comparisons should be drawn, let us hasten to say that the play has been no less fortunate in obtaining the support of Mr. H. B. Conway as Joseph and Miss Kate Rorke as the persecuted Fanny. They make a noble pair of lovers, whose varying fortunes are followed with the most sympathetic interest. How little the theatrical public care, after all, for that alloy of the goodness of human nature so much affected by naturaliste writers! Joseph Andrews is all that is upright, brave, and loyal, Fanny Goodwill all that is faithful and devoted, and the spectacle of so much virtue sends the house into raptures. ___

The Morning Post (9 March, 1888 - p.5) VAUDEVILLE THEATRE. Mr. Robert Buchanan disclaims having attempted the dramatising of Fielding’s novel, “Joseph Andrews,” in the play which he submitted to the verdict of public favour yesterday afternoon. He acknowledges his indebtedness for the leading motives of his comedy, but he has not aspired to present in “Joseph’s Sweetheart” a close or thorough dramatic version of the original story, any more than in “Sophia”—brightest and best of his plays—did he pretend to give more than a broad treatment of certain incidents in “Tom Jones”. The play’s the thing, and as such it must be judged, and not upon its resemblance to Fielding’s fanciful tale. “Joseph’s Sweetheart” fulfils one of the chief, if not the highest, of a dramatist’s legitimate aspirations. If not a work of much merit in construction and literary skill, it succeeded yesterday in thoroughly pleasing the audience, and a great success was the result. Joseph is in the service of Lady Booby, whom he has unwittingly captivated by his personal grace and accomplishments. Being faithful to his sweetheart, Fanny Goodwill, the companion of his childhood under honest Parson Adams’s roof, he declines the advances of the woman of fashion whose lacquey fate has made him. In revenge for her repulse at the hands of the supposed menial, Lady Booby prompts her licentious friend, Lord Fellamar, to carry off Fanny to his town residence. The abduction is managed through the agency of a drunken chaplain, Llewellyn ap Griffith, who gains access to the rustic home of Parson Adams in the character of a publisher anxious to purchase that worthy’s sermons. The rascal, however, plays his master false, and, to settle scores over a richly-merited thrashing which Fellamar administered to him, he contrives Fanny’s escape by persuading her to accompany her persecutor to a fête at Ranelagh-gardens, where she is rescued an restored to her friends. Meanwhile Joseph has found a position in society, and a father in Sir George Wilson. A duel is fought, in which Lord Fellamar is worsted, and in some reparation of his conduct he clears Fanny’s character, and Lady Booby is finally defeated. The acting was throughout excellent. Mr. H. B. Conway was earnest and dignified as Joseph Andrews, and infused life and feeling into the part; and surely no more winning and graceful Fanny Goodwill could have been found than Miss Kate Rorke. Mr. Thomas Thorne gave a delightful picture of clerical simplicity and good heartedness in his genial old Parson Adams, with his humble surroundings, scholarly attainments, and self-denying generosity. Miss Eliza Johnstone was richly humorous as Mrs. Slipslop, the original type of Sheridan’s Mrs. Malaprop, and Mr. Frederick Thorne, Mr. Scott Buist, Mr. William Rignold, Mr. J. S. Blythe rendered valuable service as Llewellyn ap Griffith, Squire Booby, Sir George Wilson, and Gipsy Jim. Miss Vane is to be congratulated upon the conspicuous ability and judgment displayed in the very difficult and thankless part of Lady Booby, and Miss Gladys Homfreys made a kindly and comely matron as Mrs. Adams. A word must be said for the very beautiful scenery and rich dresses with which the play has been provided. Mr. Buchanan’s new comedy, with its pathetic story, its moving incidents, and its wealth of old-world luxury, portrayed in the silks and brocades, the powder and patches, the swords and ruffles of an age when dress was picturesque as society was vicious, is sure to attain popularity, and a long run is in store for “Joseph’s Sweetheart.” The pleasant old custom of speaking a prologue was revived last night by Miss Vane, in the character of Lady Booby. |

||||||||||

|

||||||||||

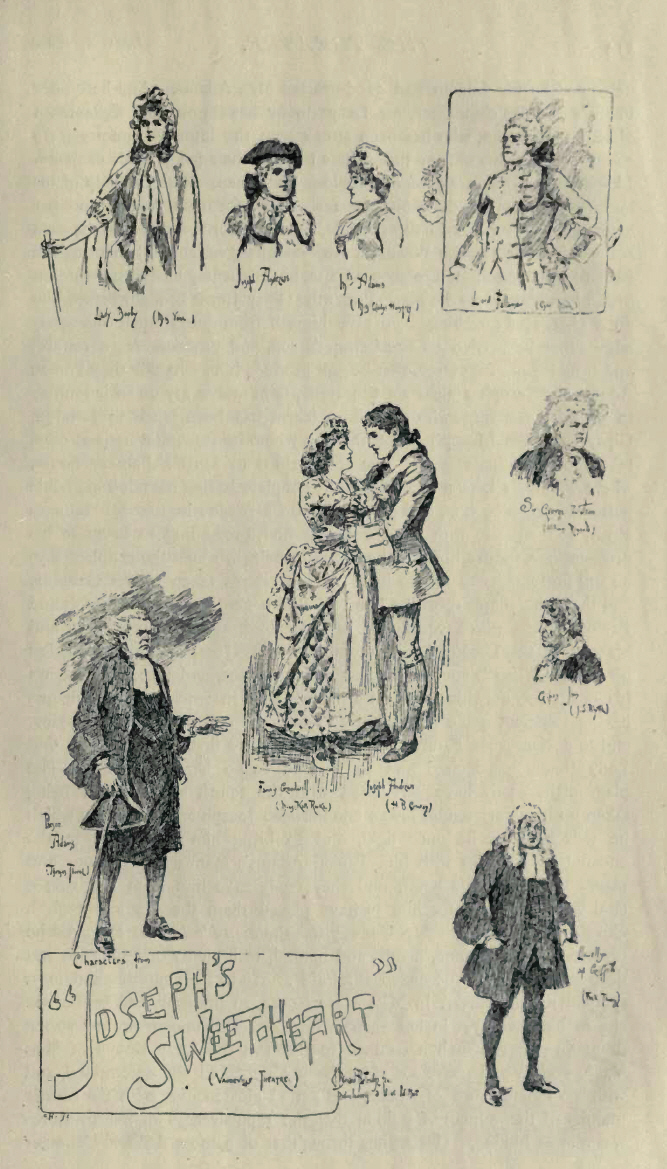

|

[Cyril Maude as Lord Fellamar, Nellie Vane as Lady Booby, H.B. Conway as Joseph Andrews, Kate Rorke as Fanny Goodwill, William Rignold as Sir George Wilson, Thomas Thorne as Parson Adams, Gladys Homfrey as Mrs Adams, Frederick Thorne as Llewellyn ap Griffith and Eliza Johnstone as Mrs Slipslop in Joseph’s Sweetheart at the Vaudeville Theatre.] |

||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||

|

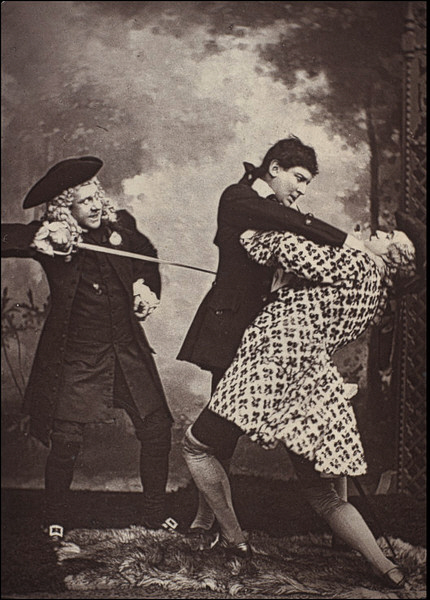

[H B Conway and Kate Rorke as Joseph Andrews and Fanny Goodwill.] [H.B. Conway, Kate Rorke and Thomas Thorne.] |

|

|

|

[Fred Thorne as Llewellyn ap Griffith, H.B. Conway and Cyril Maude as Lord Fellamar.] [Thomas Thorne and Kate Rorke.] |

|

|||||

|

|

||||

|

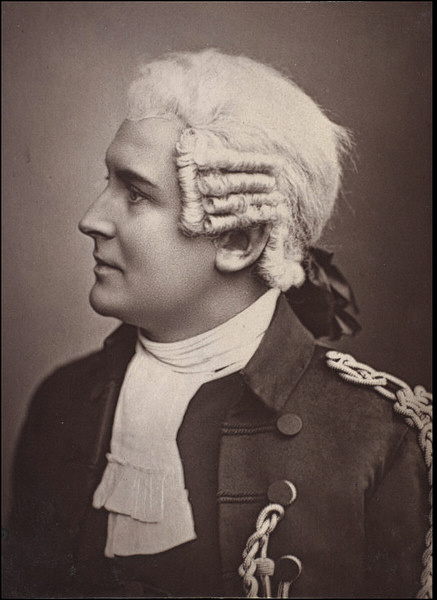

[Kate Rorke as Fanny Goodwill.] [H B Conway as Joseph Andrews.] |

|

|

|

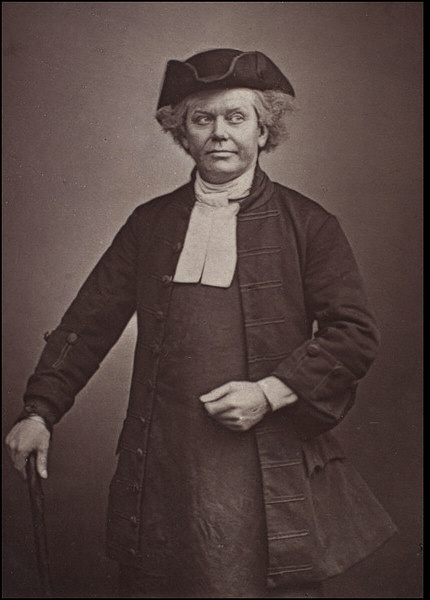

[Thomas Thorne as Parson Adams.] [Gladys Homfrey as Mrs Adams.] |

|

|

|

[William Rignold as Sir George Wilson.] [Kate Rorke as Fanny Goodwill.] |

|

|

[Kate Rorke as Fanny Goodwill.]

The Daily Telegraph (9 March, 1888 - p.3) VAUDEVILLE. A very few words must suffice on the present occasion to record the complete and deserved success yesterday afternoon of Mr. Robert Buchanan’s five-act play, “Joseph’s Sweetheart.” Following the principle he adopted in the case of “Tom Jones,” and with even greater success, the thoughtful dramatist has discarded everything from Fielding’s “Joseph Andrews” that belonged to a more outspoken and coarser age than our own, but has preserved all that is generous and human which illumine the pages of this work of genius. Once more Mr. Buchanan has made Fielding live, and presented his hearty English nature, the scenes amongst which he moved, the beaux, the blades, the homely country folk, in a manner that will be appreciated by students of the stage, as well as by those who desire to gaze upon the manners and customs of their ancestors. The genial, loveable Parson Adams; the manly, chivalrous Joseph, ever a man and never a virtuous prig; the charming Fanny Goodwill, as fresh and sweet as the violets in the English lanes she roams in; the passionate, vindictive, and unscrupulous Lady Booby; the burly Sir George Wilson, living in solitude with his silent grief; the scented, exquisite Lord Fellamar, the chatterbox Slipslop forerunner of Sheridan’s Mrs. Malaprop, and all the sparks and frail beauties of Ranelagh, pass in review before us, and as they change and counterchange we experience three distinct pleasures—the warm glow of humanity, a picture of old times, and, last but not least, a thoroughly good play. We have to congratulate Mr. Thorne not only on the good taste he has bestowed on this memorable ;production, but on his personation of dear old Parson Adams, which will considerably exalt him as an actor of tenderness and humour in the eyes of the public he has served so well, and we shall return with sincere pleasure to the greater detail and analysis of a work which may claim a place in stage literature as one of the best plays of the kind produced since “Olivia” and “Sophia.” Mr. Robert Buchanan was, of course, called when the curtain fell, and bowed his thanks in the centre of the company that one and all had done him such excellent service. Mr. H. B. Conway, Miss Vane, Miss Kate Rorke, Miss Eliza Johnstone, Mr. Frederick Thorne, Mr. Cyril Maude, Mr. William Rignold, and a new and clever actor, Mr. J. S. Blythe, all shared in the general congratulations. The playgoer of to-day, satiated with so much that is foolish in taste and false in art, is under a debt of gratitude to Robert Buchanan for bringing honest hearty Henry Fielding on to the scene. ___

The Globe (9 March, 1888 - p.2) MR. ROBERT BUCHANAN and a few writers for the Press appear to have jumped a little too readily to the conclusion that Sheridan adapted his Mrs. Malaprop from Fielding’s Mrs. Slipslop. He may have done so, but it is impossible to be sure that he did. There was one Dogberry, the invention of one Shakespeare, whose “nice derangement of epitaphs” may well have suggested a female Dogberry both to Fielding and to Sheridan, whose Mrs. Malaprop, by the way, is an infinitely more humorous creature than the rather thin creation of Fielding. _____ A CORRESPONDENT writes:—“Unless mine ears deceived me, Parson Adams, at the Vaudeville yesterday, was guilty of a couple of anachronisms in his speech. He spoke of Barabbas as having been a publisher—which joke was made originally by Lord Byron; and he also had a reference to the fact that the pen is mightier than the sword—which remark is made by Richelieu in Lord Lytton’s play. And yet Parson Adams lived before either Lord Byron or Lord Lytton.” ___

The Era (10 March, 1888) “JOSEPH’S SWEETHEART.” A New Comedy-Drama, in Five Acts, by Robert Buchanan, Joseph Andrews ... ... ... Mr H. B. CONWAY In attempting to find materials for a play in “Joseph Andrews,” in the same way as he successfully dealt with Sophia, Mr Buchanan set himself a second task much harder than his first. Having said so much with reference to the foundation of Joseph’s Sweetheart, we need not enter into any elaborate essays upon the origin of Mr Buchanan’s play. The question is, after all, not how much or how little the dramatist is indebted to Fielding, but at how much advantage he has invested his borrowings, and how he has arranged his own narrative. There is no suspicion of caricature about Mr Buchanan’s Joseph. He is a first-rate hero, muscular and admirable entirely, and his livery suits him excessively well. We find him in the first act in Lady Booby’s boudoir, and here he is wooed by that amorous dame, and his sweetheart Fanny is favourably “remarked” by that very fine gentleman Lord Fellamar. Lady Booby’s declaration is followed by Joseph’s rejection of her proposal of marriage, and an accusation by her against Joseph of his having grossly insulted her leads to his dismissal from her service. We find him, however, hale and hearty, in the second act, at Parson Adams’s cottage. Here Lord Fellamar’s Welsh chaplain and “creature,” Llewellyn ap Griffith, comes and, pretending to be a publisher anxious to buy Adams’s sermons, gets him out of the way, and assists Lord Fellamar to carry off Fanny. Joseph enters, and with the Parson’s assistance is beating down the ravishers when Griffith, to save his patron, stabs Andrews, who falls wounded, whilst Fanny is borne away. In the next act we find the wealthy Sir George Wilson in his lonely manor-house lamenting the loss of his only son, who was stolen away by gipsies when a mere child. A certain Gipsy Jim is brought up by the constables, and makes the restoration of Sir George’s lost offspring the price of his (Jim’s) release. Parson Adams arrives to seek shelter at the manor house, having been turned out of his living by its patron the revengeful Lady Booby; and after Joseph has been introduced and has vowed vengeance on Lord Fellamar, the gipsy returns and discloses the fact that Andrews is Sir George’s son. We are next taken to Lord Fellamar’s house, where Fanny is a prisoner. Fellamar, in a fit of irritation, chastises Griffith, who, in retaliation, goes over to the enemy, and advises Fanny to ask Fellamar to take her to see Ranelagh, where he (Griffith) will arrange for her rescue. Thinking that she is yielding to his proposals, the peer consents; and in the last scene of the act we get to Ranelagh Gardens, where most of the principal characters arrive. Fellamar pursues Fanny into a kiosk, and locks the door. Joseph in the full pride of his gentlemanhood, enters, bursts down the door, and releases her. Fellamar’s friends gather round him with drawn swords; but they are confronted by Adams and Griffiths with his friends. Andrews strikes Fellamar, and dares him to a deadly combat, which takes place in the last act, but not coram populo, and Fellamar is wounded, Joseph being saved by the MSS. of Adams’s sermons being used to serve as a shield for his vitals. Fellamar acknowledges Fanny’s innocence, Lady Booby departs chagrined and defeated, the lovers are united, and Adams is presented by Sir George Wilson with a living of a hundred a year. Ladies and Gentlemen,—Behold in me Well, ’mid the masquerade, the pinchbeck show, And now our task is, in a merry play, ___

The Referee (11 March, 1888 - p.3) Robert Buchanan's second adaptation from Fielding—“Joseph’s Sweetheart” (based upon “Joseph Andrews”)—was tried at the Vaudeville on Thursday afternoon, and met with deserved success. I say deserved advisedly, for all readers of “Joseph Andrews” will admit that it is difficult to adapt that story for the stage—more difficult even than “Tom Jones.” “Joseph Andrews” was intended as a travestie of Richardson’s goody-goody nauseous novel, “Pamela; or, Virtue Rewarded,” and also as a means to the end of girding at Actor-manager Colley Cibber, whom Fielding regarded as “pison.” Buchanan, pointing out in a singularly modest preface that all that is bad in “Joseph’s Sweetheart” is his own, has attacked his subject boldly. Some may say too boldly, and may give off remarks about mutilating the works of great men, and so forth. No one reverences great men more than yours truly, but I hold that in adapting a story for the stage your first aim should be to make an actable and interesting play, and to that end you should only take from your novelist as much material as will serve your purpose. This is what Buchanan has done, and the result is a play which, up to the end of the third act, is as strong as need be. The fourth will be all the bettor for considerable cutting; while the fifth might with advantage be omitted altogether. In the other parts of the piece Buchanan’s alterations are mostly sage and discreet. In this they are the reverse. Nevertheless, with judicious revision, “Joseph’s Sweetheart” (which was put into the evening bill on Friday) should attract for some to come. After Lady Booby has stepped forward and delivered an appropriate prologue, in which Buchanan’s bardic skill is manifest, you discover Lady B.’s boudoir, and after some topical tittle-tattle, chiefly led by a wild Welsh chaplain (introduced), the virtues of Lady B.’s footman, J. Andrews—a fine, manly young fellow—are sung by all and sundry. Ere long the well-known scene in which Joseph’s virtue is attempted by Lady Booby is realistically re-enacted, minus a few of Fielding’s details, which could hardly be expected to pass the eagle eye of Play Licenser Pigott. Joseph, as of yore, remains firm in spite of all temptations, for his heart is true to Fanny—née Goodwill, who presently calls in to see him, accompanied by the Rev. Abraham Adams—one of the finest characters the great novel-writing Bow-street magistrate ever drew. The parson proceeds to give off considerable amusing dialogue on divinity, the classics, and domestic matters, and Fanny chronicles small beer. Anon Lady B. returns, and, making a general clearance, again lays violent siege to Joseph in a very pronounced manner. On J. repulsing her in righteous horror, she borrows still more from the Potiphar cause célèbre than even Fielding did, and, in a strong scene, charges Joseph with indecent assault. Then is Joseph chucked, while Lady B., consumed by rage, plots aside with a wicked peer, Lord Fellamar (introduced), who has been ogling Fanny, to get the girl into his power. All this, and the Rev. Adams’s fiery denunciation of the aristocrats, form a powerful curtain to Act. I. Anon Adams, Joseph, and Fanny (who is Adams’s foster-daughter) return chez Adams, and all seems at peace. But, after some capital comedy business, and a strong melodramatic scene, in which the Parson protects a picturesque gipsy named Jim (introduced) from an infuriated mob, and gets in return promises of reformation, we find that the licentious Lady B., Lord Fellamar, and his creature, the Wild Welsh Chaplain, are lurking around. Watching his opportunity, the wicked Welshman, look you, sends Adams on a wild-goose chase about getting his sermons published, and attempts to carry off Fanny to Fellamar. A fearful struggle ensues, Gipsy Jim returning to give the parson the tip and to assist at rescue. Adams and Andrews also return and assail the abductor, when Fellamar and his creatures overpower them, and, stabbing Joseph in the back, carry off the shrieking Fanny, to appropriate music and London. In the third act you find Sir George Wilson (altered from Fielding’s Merchant Wilson, and made stronger and more pathetic) lamenting the stealing of his son three-and-twenty years ago. Anon, Adams and Andrews, in full pursuit of the abductors, but travel-worn and hunger-stricken, call in for succour, and after a good deal of anguish, well worked up, Gipsy Jim, who has just been brought before Wilson for poaching, points out that the wounded and starving Joseph is the boy he (Jim) stole from Wilson three-and-twenty years ago, and again the act-drop falls amid much excitement. The next act is taken up with showing Fanny in the lordly libertine’s toils, her struggles to preserve her honour, and her being set in a way to escape by the Wild Welshman, who now seeks revenge for a beating Fellamar has given him. Next, after a tedious front-scene, you see Ranelagh, whither Fanny is brought by Fellamar. Here she makes a heartrending but ineffectual appeal to the harlots and libertines standing around, and finally, after Fellamar has caged her in a kiosk O. P., she is rescued by the now lordly Joseph and Adams &c., &c., Joseph bashing Fellamar, and denouncing him as a coward. Act V. is merely taken up by the inevitable duel, by sundry explanations, and a clever rhymed tag. There is some fine acting in “Joseph’s Sweetheart.” First, I must place Kate Rorke, whose Fanny is sweet and pathetic throughout. I warrant me Fanny will draw tears from your eyes, when she is surrounded by satyrs, panders, and what not, and you will not wonder at J. Andrews’s constancy. Miss Vane, a fine figure of a woman, plays splendidly as Lady Booby, but the character is far too long. A good deal of her gloating over her pure little rival might easily be left out. She isn’t wanted at all either in the front scene in the fourth act, or in any part of the fifth. Miss Eliza Johnstone is a right merry Mrs. Slipslop (retaining all Fielding’s wheezes, barring the coarseness). Miss Gladys Homfreys is a statuesque and genial Mrs. Adams. Thomas Thorne’s Parson Adams is at once humorous and powerful, stronger and more finished than his Partridge. But this part also sadly needs cutting down by at least a third. As the Wild Welshman, Fred Thorne did not score so much as is his wont, but it is a stupid part and hardly wanted at all, even in his one big scene, where he represents a sort of eighteenth-century Hawkshaw pretending to be asleep on a table. H. B. Conway is seen to great advantage as Joseph, acting in a fine, manly fashion throughout, and William Rignold is highly impressive as Joseph’s long-sorrowing father. Sound successes were made by Mr. Cyril Maude as the licentious Lord Fellamar, Mr. Scott-Buist as Squire Booby, and by Mr. J. S. Blythe (whom some seem to regard as a new actor) as the intense Gipsy Jim. The play is splendidly mounted. ___

The Stage (16 March, 1888 - p.14) VAUDEVILLE. On Thursday afternoon, March 8, 1888, was produced a new five-act comedy drama founded by Robert Buchanan upon Fielding’s novel “Joseph Andrews,” and entitled:— Joseph’s Sweetheart. Joseph Andrews ... ... ... Mr. H. B. Conway In Joseph’s Sweetheart Mr. Buchanan has boldly and successfully dramatised a very ticklish story. Fielding’s novel is perhaps well known to our readers, and so we will merely skim over the incidents Mr. Buchanan has brought together for his play. Joseph Andrews is in the service of Lady Booby, who is so enamoured of her servant as to openly declare to him her unconquerable passion. On the other hand Joseph’s sweetheart, Fanny, has aroused the unlawful desires of Lord Fellamar, whose attentions to the poor girl are encouraged by Lady Booby for her own vile ends. Joseph spurns his mistress’s advances and so inflames her anger that she accuses him of making overtures to her. So poor Joseph is dismissed from her house. In Act 2 Joseph and his beloved Fanny are found in company with Parson Adams, to them enters Llewellyn ap Griffiths, Lord Fellamar’s chaplain. The latter, pretending that he is a publisher, offers the parson a large sum of money for his unpublished sermons, contrives to get him out of the way, and then, with the assistance of Lord Fellamar and his servants, carries off Fanny, but not before Joseph and the parson—who has re-entered—have given the scoundrels a sound thrashing. In the affray Joseph is wounded by Griffiths, and sinks to the ground as his beloved is borne off by her captors. In Act 3 we find Sir George Wilson in his manor house brooding over the past, and recalling sad memories of his dead wife and his lost son, who when a child has been stolen by gipsies. Gipsy Jim—who had formerly promised to stick to Joseph through thick and thin in return for some kindness shown him—now enters, brought in by constables. On condition that he is permitted to escape free he promises Sir George that his lost son shall be found. Act 4 shows us a room in the house of Lord Fellamar in which the Welsh chaplain Griffiths is recovered from a drunken stupor. Griffiths is assaulted by Fellamar, and in revenge swears to protect Fanny, who is a prisoner in Fellamar’s house. True to his word Griffiths manages Fanny’s escape by planning a ruse. Fanny is to accede to Fellamar’s desire to accompany him to Ranelagh Gardens without demur. Griffiths is to be on the spot, and with a few faithful followers is to secure her freedom from her would-be ravisher. This plan succeeds. Fellamar and Fanny visit Ranelagh Gardens. Here nearly all the characters are cleverly brought together by the dramatist. Fanny, heartbroken and despairing of relief, rushes madly from a gay throng of painted and shameless women into a wooden house, pursued by Fellamar. Griffiths calls together his band and is about to commence a rescue when Joseph appears. A scene between Fellamar and Joseph ends in the latter striking Fanny’s abductor and challenging him to a duel. In Act 5, a tavern near Lincoln’s Inn Fields, Fellamar’s second appears and questions the right of Joseph to fight with a gentleman. Sir George enters and declares Joseph to be a man of birth—his own son. Joseph goes off to fight Fellamar. The latter shortly after returns badly wounded, and asks forgiveness for the pain he has caused all. Joseph forgives him, and at the same time gives some well-timed advice to Lady Booby, who has come to gloat over what she thinks the ruin of Fanny and the defeat of the man she has so passionately admired. Thus Fanny and Joseph are once more united, and Parson Adams finds in Sir George a firm friend and patron. Despite a want of cohesiveness, Joseph’s Sweetheart is a cleverly contrived play—one that should bring in a rich harvest to the Vaudeville management, who on Friday placed it in their night bill. The piece is prettily staged, perhaps the most natural set ever seen upon the boards is the thatched cottage of Parson Adams—a delightfully rural looking structure, without the slightest sign of the stage carpenters’ or painters’ hands. The interiors, too, are all well designed and painted sets, reflecting the greatest credit on all concerned. Mr. Conway is to be congratulated upon his success as Joseph. He not only looks the part perfectly, but also plays it with much freshness and vigour, giving a picture that is almost inseparable from the play. Mr. Rignold is well suited as Sir George, of which part he gives a dignified and characteristic portrayal. Mr. Fred Thorne as the little backcrawler, the Welsh parson, looks and acts admirably, his fire-eating speeches being received with great laughter. A hit is made by Mr. Blythe as the outcast, Gipsy Jim. His make-up and performance are equally good. Mr. Maude shows much skill and refinement as Lord Fellamar, and Mr. Buist as Squire Booby gives a most acceptable impersonation. Parson Adams, a dear old fellow, after the style of the Vicar of Wakefield, full of contentment and thankfulness for his present welfare, yet having enough of the old Adam in him to resent a blow with a blow, is capitally played by Mr. Thos. Thorne, who gives equal attention both to the serious and the comic side of the character. The most difficult character of Lady Booby is admirably enacted by clever Miss Vane. How many actresses could successfully portray this part without giving offence, we wonder. Miss Vane, like a true artiste, sinks all personal feeling, and depicts to the life the lustful and revengeful woman, who, unable to carry out her designs upon Joseph, seeks to destroy his happiness by blasting the fair fame of his loved one. A hateful character grandly played. Miss Johnstone as Mrs. Slipslop—another Mrs. Malaprop—appears to revel in the part. She gives her lines with a seeming unconsciousness that is most enjoyable. Another clever performance comes from Miss Homfrey as Mrs. Adams. A perfect picture of the old parson’s loving spouse is given by this actress, whose appearance is well suited to the character. Pretty Miss Rorke as Fanny looks charmingly and acts with much modesty and freshness of style, contributing a sketch of a dear little country maiden, such as we should imagine Fanny to be—gentle and affectionate. [as above] ___

The Athenæum (17 March, 1888) DRAMA THE WEEK. VAUDEVILLE.—‘Joseph’s Sweetheart,’ a Drama in Five IF the ghost of the author of ‘The Temple Beau,’ ‘The Tragedy of Tragedies,’ and ‘The Intriguing Chambermaid’ is permitted to revisit “the glimpses of the moon,” and take an interest in mundane affairs, it must be a little disconcerted to see what a mine of wealth lay unexplored in the novels which it has been reserved for the present day to dramatize. With his power of characterization and his many other eminent gifts, Fielding might easily have given us the best dramas of his epoch. His plays were, however, as a rule, written in haste to serve a temporary purpose, and though they swell Fielding’s literary baggage do not rank beside his novels. The idea, meanwhile, that the ramblings of Partridge or the advances of Lady Booby could be fitted to the stage does not seem to have struck Fielding or any of his contemporaries or successors. To Mr. Buchanan belongs the credit of first seeing how much that is dramatic was buried in Fielding’s two masterpieces, and of turning it to profitable account. ‘Joseph’s Sweetheart,’ as Mr. Buchanan calls his adaptation of ‘Joseph Andrews,’ is a brisker and more stimulating drama than ‘Sophia.’ It is a strong, rather roughly constructed work, which appeals directly and forcibly to the sympathies. That it is representative of the great work out of which it is dug Mr. Buchanan will not claim. The judgment of the adapter is, indeed, best seen in the manner in which he has selected from the huge amount of matter at his disposal. Presenting us with a fresh and tender interest in the shape of the loves of Joseph Andrews and Fanny Goodwill, he has in the approved fashion placed it in the midst of a world of cynicism which serves it as an effective background. Lady Booby, to whom the troubles of the lovers are mainly due, is rather too fiendish to win acceptance. The other characters are, however, fresh and natural. Mr. Thorne’s company has had meanwhile a training in Fielding, and its success in dealing with the creations of the great novelist is creditable and even surprising. The pleasing qualities and eccentricities of Parson Adams are presented by Mr. Thomas Thorne with a moderation that is thoroughly artistic, and that never subsides into tameness. Mr. H. B. Conway is an admirable exponent of Joseph Andrews. Miss Kate Rorke is a winsome Fanny, and Mr. F. Thorne is a singularly fiery and entertaining Llewellyn ap Griffith. Exercising a conscientiousness eminently artistic and creditable, Miss Vane exhibits all the worst features of Lady Booby, one of the most thankless parts a woman has often been called upon to play. Not less well represented are the remaining characters, and the Lord Fellamar of Mr. Cyril Maude, the Squire Booby of Mr. Scott Buist, Mr. William Rignold’s Sir George Wilson, and Miss Eliza Johnstone’s Mrs. Slipslop prove satisfactory. Much care had been taken with the rehearsals, and the whole went with much spirit. Out of a microcosm such as is Parson Adams to extract a work so shapely and so effective as ‘Joseph’s Sweetheart’ is creditable to Mr. Buchanan, and to assign Fielding’s characters so much recognizable individuality is honourable to the manager. The piece will probably run for hundreds of nights. It is only to be hoped that familiarity with the parts will not lead the actors to degenerate into the farcical extravagance from which their present performance is free. ___

The Illustrated London News (17 March, 1888 - p.7) THE PLAYHOUSES. A few months ago there was a discussion about the condition of Henry Fielding’s grave in the Protestant cemetery at Lisbon. Some officious person wrote to the papers that it was shamefully neglected; but it all turned out to be ridiculously untrue, for the grave is of solid stone—ære perennius—and it is surrounded by flowering shrubs and mournful cypresses, and the English ladies who visit Lisbon never fail to scatter roses on the solid sarcophagus containing all that is left of the author of “Tom Jones” and “Joseph Andrews.” Mr. Robert Buchanan has just added one more flower of graceful literature to the author’s memory, for he has given us even a better play than “Sophia.” The Vaudeville ought to be crowded every night until the end of the season with audiences anxious to see and enjoy “Joseph’s Sweetheart.” Little did Fielding dream what a good play would be made out of his first story. As everyone knows, Fielding was a dramatist of considerable renown long before he dreamed of writing a novel, and his first venture was launched in order to vex Richardson and cast ridicule on his “Pamela; or, Virtue Rewarded.’ Richardson was in the odour of sanctity, Fielding was a Bohemian; Richardson was among the elect of society, Fielding was out in the cold. But the righteous soul of Henry Fielding rebelled against all this sugary sentimentality and fatuous Phariseeism, so he resolved to imitate Cervantes, to give us a new Don Quixote, to immortalise his old friend and scholar the Rev. William Young, and to sketch a lusty handsome footman who should resist temptation, whether it came from mistress or maid, and who should have as much real virtue as a dozen Pamelas. The bare idea of dramatising “Joseph Andrews” seemed to the uninitiated even more daring that that of giving us a stage version of “Tom Jones.” But there is nothing succeeds like success, and encouragement has given heart to Mr. Buchanan’s work. We get the outlines of the story very fairly presented, and the chief characters very adequately sketched. It is distinctly unfair to say that Fielding has suffered at the hands of the dramatist. We cannot get his incomparable language, or the whole fruit of his satire; but we certainly do get his humanity, his fresh breezy nature, his virility, and his English spirit, which, after all these years, puts to shame the mawkish stuff of the female satirists of to-day—women who occupy the stage with so-called society dramas, and who, when they do not poison, add to the discontent and indifferentism that check the healthier aspirations of the young. If we do not get Fielding pure and simple, we get a breath of him. We are no longer taken to stuffy divorce courts, or to unwholesome boudoirs, or to the orgies of the drunken and the dissolute; but away we go to the sunny cottage of Parson Adams, that affords so pleasant a contrast to the Hogarthian home of Lady Booby. The temptation of the immaculate Joseph by his indolent, scheming mistress; the proud boy’s banishment to his country home; the scheme of the defeated woman to ruin Fanny Goodwill in order to revenge herself on her honourable lover; the abduction of Fanny; the discovery of the wealthy father of Joseph, now no longer a servant; the rescue of Joseph’s sweetheart from the snares of a libertine; the duel between Andrews and Lord Fellamar, and the subsequent reconciliation—all these incidents are dovetailed into the scheme of the drama with remarkable skill, and make up a play of singular interest. And who shall say that we do not get a speaking likeness of our old friends in the Parson Adams of Mr. Thorne, the Lady Booby of Miss Vane, the Joseph of Mr. H. B. Conway, the Fanny of Miss Kate Rorke—all of them performances of conspicuous merit. There is no better comedy-acting to be found than in this cast. Parson Adams, with his gentle heart and veiled pugnacity, his keen sense of honour and love of Æschylus, his beneficent charity and comical absence of mind, is made a lifelike creation by Mr. Thomas Thorne, whose recent advance as an actor is very remarkable. In the long gallery of his successful personations—Caleb Deecie, Tom Pinch, old Partridge, and the rest—the new Parson Adams will take a very prominent position, for it is firmly drawn and painted in brilliant and lasting colours. Miss Vane is also to be congratulated on her nice artistic sense and bold handling of Lady Booby—a most difficult character to play, and one that requires immense tact to steer to success. Mr. Conway and Miss Rorke make a delightful pair of lovers, free wholly from mawkish sentimentality and both as bright and breezy as the downs from which they come, in the characters of Joseph and his sweetheart. A strong bit of sound dramatic character-acting comes from Mr. J. S. Blythe, who plays Gipsy Jim, a scamp who eventually proves the correct birth and parentage of Joseph. Mr. Blythe has the voice and manner of Mr. Fernandez, and some of his electric force as well. Other excellent assistance comes from Mr. F. Thorne, Mr. Scott Buist, and Mr. Cyril Maude, who gives a very clever sketch of a man of fashion under the Georges. How Thackeray would have liked to see this wholesome play, which is enjoyable in itself, and a wholesome antidote to much that is false and foolish elsewhere! ___

The Academy (24 March, 1888 - p.212) THE STAGE. THE COMEDY AT THE VAUDEVILLE AND IN presenting an adaptation of Joseph Andrews at the Vaudeville, Mr. Buchanan takes occasion to refer to the success of his version of Tom Jones, and to say that that proved how unnecessary it is, in dramatising the great masters, “to preserve the coarseness of their period as well as the humanity of their genius.” The sentence is neatly turned, and it expresses one side of the truth. Mr. Buchanan, when he deals with Fielding, does preserve, I think, “the humanity of his genius.” That inspires Mr. Buchanan to write acceptable and genial, if sometimes ill-constructed, plays; but Mr. Buchanan does not in the strict sense “dramatise” Fielding at all. Nor could Fielding, in the strict sense, be dramatised without the retention of a great deal of what Mr. Buchanan condemns as coarseness. The fact is, Fielding was a very penetrating student of human nature. Fielding actually wrote what Thackeray declared no modern novelist would dare to write—the history of the average young man. Hence a certain element of coarseness, a certain plainness of speech, which, in the treatment of the novelist by Mr. Buchanan, must be at once got rid of. If Mr. Buchanan’s pieces pose as substantially accurate stage versions of rollicking and powerful eighteenth-century fiction, I hold them to pose unwarrantably. But if they assert themselves only as engaging “variations” on a theme which a great master has supplied—and especially as variations suitable to the day, and suitable to the requirements of Mr. Thorne and an always competent company—I accept them cheerfully, as such. Nay, notwithstanding here and there a common repartee and inappropriate retort, I think them, on the whole, very dexterous and agreeable playwright’s work, inasmuch as they do bring upon the stage effectively nearly all of Fielding’s characters that can properly be brought there. The last of them affords opportunity for a thorough stage realisation, not of the book indeed, but of Parson Adams, of his wife, and of the young woman in whom he shows so legitimate an interest. Joseph Andrews himself is not quite so adequately presented by the dramatist, because he is deprived of at least one important motive for action. He is not tempted as his sister Pamela was. And Lady Booby, as Mr. Buchanan conceives her, is unnatural and inconsequent. Had it occurred to her to propose marriage to Joseph, it would not have occurred to her, on his refusal, to charge him with violence. That could only have been the act of the Lady Booby whom Fielding, and not Mr. Buchanan, imagined—a Lady Booby gross and ungoverned: a Potiphar’s wife. ___

The Illustrated Sporting and Dramatic News (31 March, 1888 - p.19) OUR CAPTIOUS CRITIC. |

|

|

Lloyd’s Weekly London Newspaper (1 April, 1888 - p.5) PUBLIC AMUSEMENTS. VAUDEVILLE THEATRE. Mr. Robert Buchanan has contrived in Joseph’s Sweetheart an interesting love story, which is unfolded in an exciting way. The likeness of the play to Fielding’s romance is very faint, though the same period has been chosen. Joseph Andrews is a handsome young retainer of a fashionable lady, who, captivated by his personal graces, makes him a flattering proposal of marriage in unmistakeable terms. Pretty Fanny Goodwill, Joseph’s sweetheart, is in the house at the moment, and little wonder if the young gentleman proves true to his plighted troth, and declines the proferred honour. He is driven from the house on a false charge by his infuriated mistress, but seeks the kindly shelter of the roof of Parson Adams. The worthy clergyman’s cottage gives Mr. Perkis opportunity for one of the most fascinating country scenes imaginable. Amid roses and sunshine Fanny and Joseph vow to be ever true, despite all Lady Booby’s scheming. The licentious Lord Fellamar, however, intervenes, and readily complies with Lady Booby’s suggestion to carry off Fanny to London. A quaint little Welsh chaplain, a creature of the nobleman’s, is set to lure Parson Adams away, and chiefly through his action the abduction of Fanny is effected, Joseph being struck down by a cowardly sword-thrust. Poor and weak, Joseph and the faithful clergyman start on an almost hopeless journey in pursuit. On the way they meet kind friends, and fate ordains that the true story of Joseph’s birth shall be made known, a gipsy discovering the secret that he is son to the wealthy Sir George Wilson. Thus, with money and powerful influence, Joseph arrives in the metropolis at the moment that Fanny is saved by the timely repentance or rage of the Welsh chaplain, who turns a traitor to his patron in consequence of having received a sound and not unmerited thrashing. In a capitally contrived scene of Ranelagh gardens, Fanny is rescued at the sword’s point, and with a duel in which love proves victorious the play ceases. Miss Kate Rorke is the most winsome of heroines; she is graceful and girlish, and yet in the trying tearful scenes of the play singularly impressive and powerful. Mr. H. B. Conway has been the lover, but on Monday we found Mr. Frank Gilmore, a handsome young gentleman of some promise, playing the part. A droll picture of the somewhat bellicose Parson Adams is given by Mr. Thomas Thorne, and his whimsicalities, and particularly his learning keep the audience in a continual roar of laughter. Mr. Frederick Thorne hits off the peculiarities of a Welshman with much success, and Mr. Cyril Maude is the lord, and Miss Vane the vengeful Lady Booby. Much care has been bestowed upon the mounting, and Joseph’s Sweetheart is no doubt destined to rival Sophia in popularity. |

|

|

[Illustration from The Theatre (2 April, 1888).]

The Theatre (2 April, 1888) “JOSEPH’S SWEETHEART.” New Comedy Drama, in five acts, by ROBERT BUCHANAN, founded on FIELDING’S novel, “Joseph Andrews.” |

|

|

|

Mr. Buchanan has taken his idea from Fielding’s novel, but without sacrificing for a moment the spirit of the work, he has written a play which may to all intents be called original, and one that, from its hearty nature, admirable construction, and its polished dialogue, may be considered as one of the best that has been produced for some years. The author has been careful to make the hero a manly fellow, protected against the wiles of other women by the honest love he bears for a young country girl, not a sanctimonious milksop. The enamoured lady of fashion, too, may almost be forgiven her passion in consequence of its object being of such a noble nature; and in the country parson we have a being who is all charity and kindliness, showing some of the weaknesses of the old Adam in his not hesitating to call to his aid his good blackthorn stick when requisite, with a spice of dry humour, and a natural human weakness for believing that his sermons have only to be seen by a publisher to be at once purchased and printed; and in the telling of his story Mr. Buchanan has faithfully reproduced the characters and scenes of a hundred years ago. The play opens in Lady Booby’s tiring room, where we find her surrounded by exquisites and ladies of fashion. Joseph, her handsome man-servant, has inspired her with love, as he has also her maid, Mrs. Slipslop, but he will have none of either. The great lady, finding her advances repulsed, at once summons her servants and accuses Joseph of insulting and trying to kiss her, and his immediate dismissal is the more disgraceful from the fact of the accusation having been made in the presence of his sweetheart, Fanny Goodwill, who has been brought up to town by Parson Adams. These two, however, will not believe that he can be capable ot such conduct, although the nobility of his mind prevents him from casting the blame on his late mistress, and so these three journey back to the country parsonage, where they are welcomed by the buxom and good-hearted Mrs. Adams. And here poor Fanny’s troubles commence, for Lady Booby has set on Lord Fellamar, a dissolute nobleman, who has been struck with the innocent country girl’s charms, to carry her off, and this is done through the agency of his chaplain, Llewellyn ap Griffith, a choleric, bibulous Welshman. With the help of his lordship’s servants, and despite the resistance of Parson Adams and her lover, who is wounded in the struggle, Fanny is borne away. In the next act we find Sir George Wilson, a rich country gentleman, lamenting the fact of his having no one to succeed him, his infant boy having been stolen from him many years before. Presently Gipsy Jim is brought before him on a charge of poaching. To save himself from punishment the gipsy admits that he carried off the baronet’s son, and promises for a reward, and if he is let off scot-free, that he will produce him. At this time Parson Adams and Joseph appear on the scene, faint and weary on their journey in pursuit of Fanny, who they have learnt has been taken to London. Gipsy Jim reveals Joseph to be the boy whom he stole, and he is at once taken to his father’s arms. The scene shifts to Lord Fellamar’s house, where Fanny is kept a prisoner. The chaplain having offended his noble patron is struck by him, and determines on revenge; he therefore induces Fanny to temporise with Lord Fellamar, and, pretending to listen to his protestations, induce him to take her to Ranelagh, where the chaplain says he will find means to rescue her. And so she is taken to the Gardens, and there the chaplain, with a band of Welsh gentlemen, aids Joseph and Parson Adams, who have tracked her here, to beat off her persecutor and his companions, Lord Fellamar consenting to meet Joseph, now recognised as Sir Joseph Wilson’s son. The meeting takes place, and Joseph overcomes his antagonist, notwithstanding the latter’s skill in fencing, the nobleman having sufficient grace left in him to regret the part he has been playing, and to declare that Fanny is as pure as when he first saw her, and that Lady Booby has incited him to try and make her his victim. The play might easily have concluded with the fourth act, the fifth being taken up by a very tender love scene between Joseph and Fanny, in which he tells her that he must fight, and to bring him good luck in the encounter he carries with him Parson Adams’s manuscript sermons and places them next his heart, and they really save him from receiving a fatal wound, though for him to have placed them there was scarcely a.chivalrous proceeding. Mr. Conway was the beau ideal of the character he represented—handsome, manly, and natural, with plenty of animation and deep tenderness, he succeeded admirably. He had a charming and most sympathetic sweetheart in Miss Kate Rorke, so innocent and gentle was she in her love; yet in her scene with Lord Fellamar rising to strong dramatic power. Such a contrast to her was the Lady Booby of Miss Vane, worldly and conscious of her beauty, depraved and determined, and with no innate sense of shame, and yet so glossed over with the courtly manner of the woman of fashion that the repulsiveness of her overtures was almost hidden. Her acting throughout of a most difficult character was worthy of the very highest praise. Though Parson Adams resembles Partridge in some of his characteristics, Mr. Thomas Thorne has made of the kind-hearted country clergyman a different study. He has instilled into it more firmness and decision, and there is a change in the humour, but the charity and simplicity of his disposition are ever apparent. I think the representation might have been a little strengthened had the Parson not been quite so ready to cudgel evil-doers. Mr. William Rignold was a dignified Sir George Wilson, and his sorrow for the loss of his son was expressed in manly fashion. Mr. Frederick Thorne was excellent as the choleric Welshman. Mr. J. S. Blythe was picturesque and vigorous as the poacher, Gipsy Jim. Mr. Cyril Maude as the foppish roué, Lord Fellamar, gave another proof of how rapidly he is rising in his profession. Miss Eliza Johnstone as Mrs. Slipslop delivered her Malaprop-Iike perversions of speech with delightful unconsciousness, and Miss Gladys Homfrey and Mr. Scott Buist, Mr. Frank Gilmore and Miss Grace Arnold rendered valuable assistance. The scenery throughout was good; the exterior of Adams’s cottage, a solidly-built set, being one of the best that has been seen. Lady Booby’s boudoir is a capital reproduction of one of Hogarth’s pictures. “Joseph’s Sweetheart” was a decided success, and was put in the evening bill on Friday, March 9. [as above] CECIL HOWARD. ___

The Morning Post (3 April, 1888 - p.3) VAUDEVILLE. Mr. Robert Buchanan’s charming play, “Joseph’s Sweetheart,” has firmly established itself in popular favour. His free, but skilful, treatment of Fielding’s novel has produced a comedy that may well rank in point of merit with “Sophia;” and so prosperous is the career of the new piece that no further attraction was required to fill the theatre twice yesterday to its utmost capacity. Quite to the taste of the spectators was the manly, sympathetic acting of Mr. H. B. Conway, who resumed his part of Joseph after a recent indisposition. Miss Kate Rorke showed great tenderness and grace as his faithful “sweetheart,” and Mr. Thomas Thorne worked with hearty good-will as the simple self-denying Parson Adams. The beauty of the scenery and the richness of the dresses were much admired, especially in the fête at Ranelagh. _____

Joseph’s Sweetheart - continued

|

|

|

|

|

|

|