|

|

|

|

|

ROBERT WILLIAMS BUCHANAN (1841 - 1901)

|

|

|

|

THEATRE REVIEWS

5. The Queen of Connaught (1877)

The Queen of Connaught

by Robert Buchanan and Harriett Jay (adapted from Harriett Jay’s novel, The Queen of Connaught.)

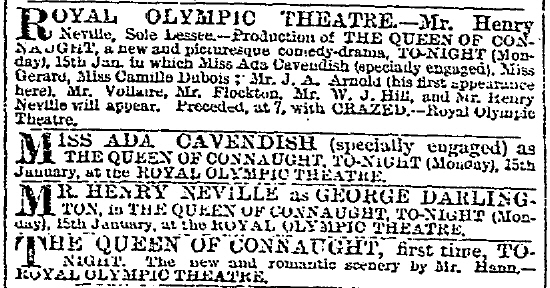

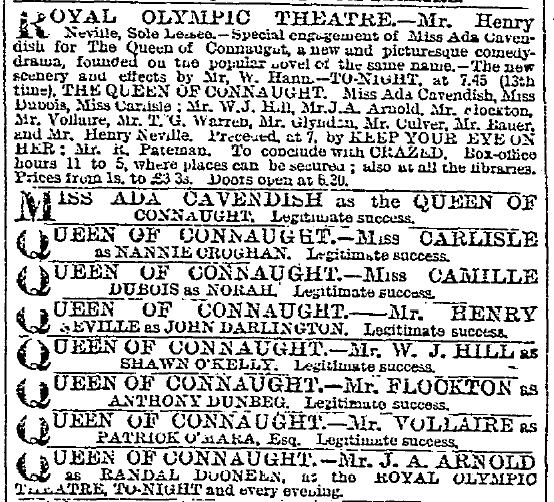

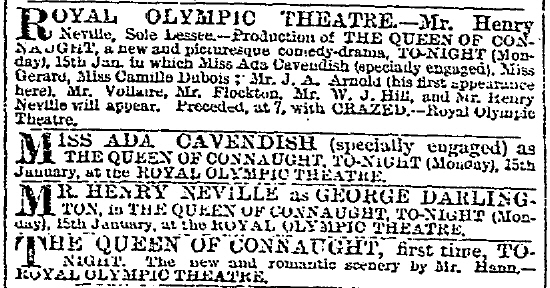

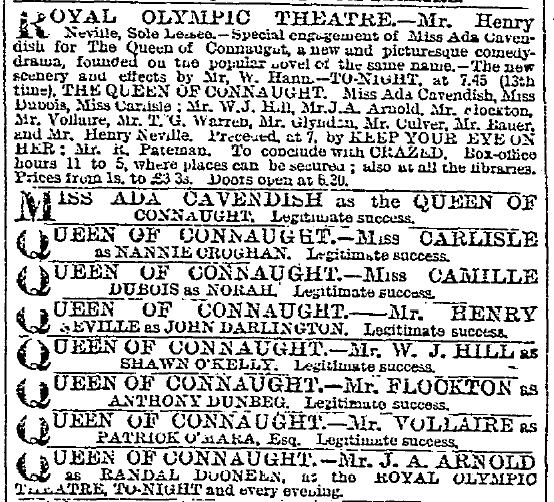

London: Royal Olympic Theatre. 15 January to 17 March, 1877 (53rd performance).

Other London Performances:

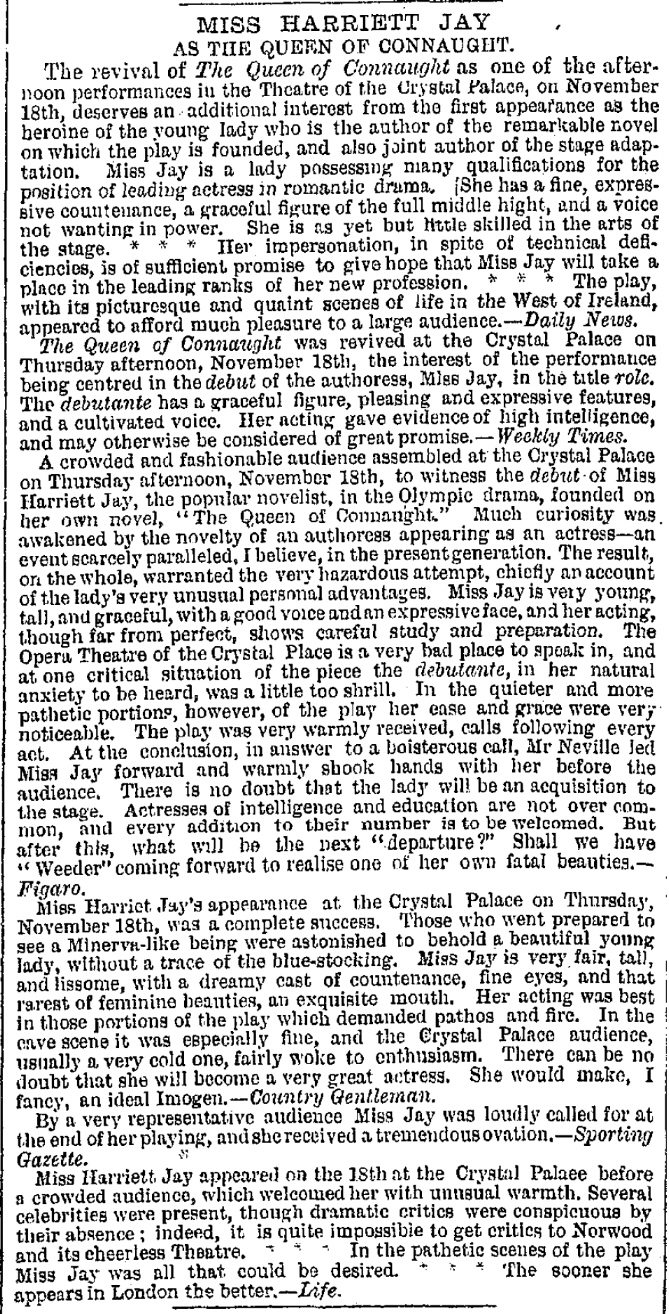

Crystal Palace, 18 November, 1880 (Harriett Jay matinée. Her London début as an actress).

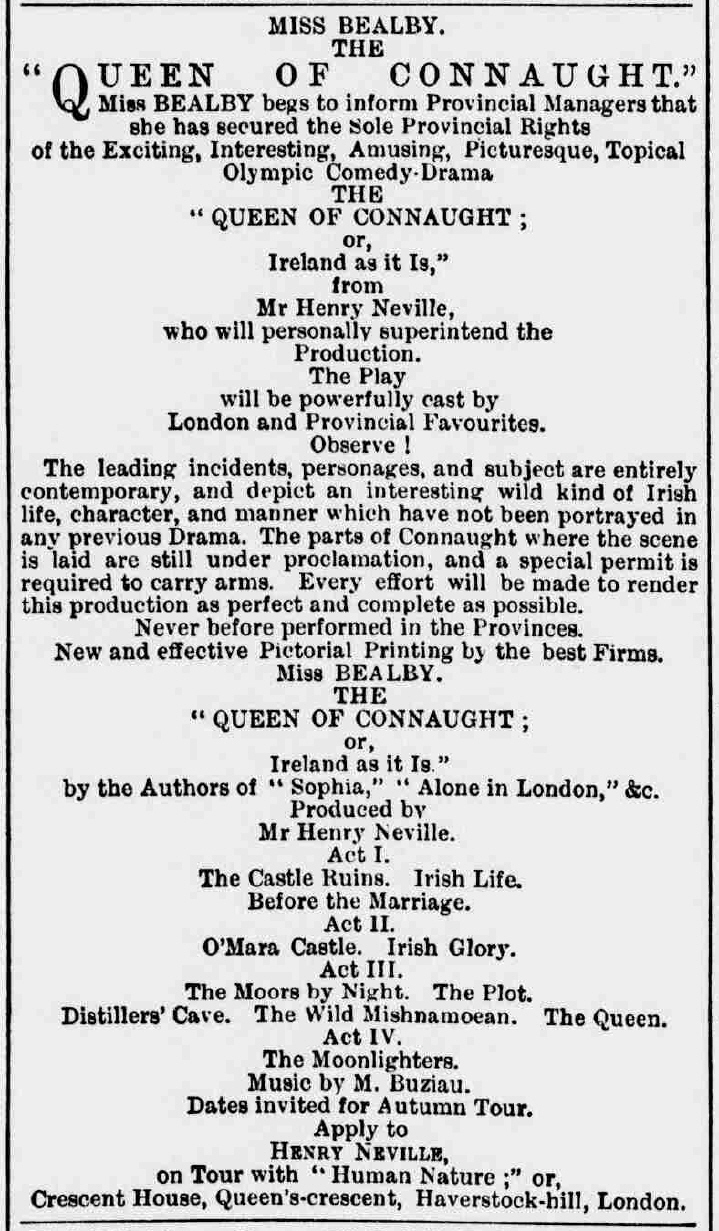

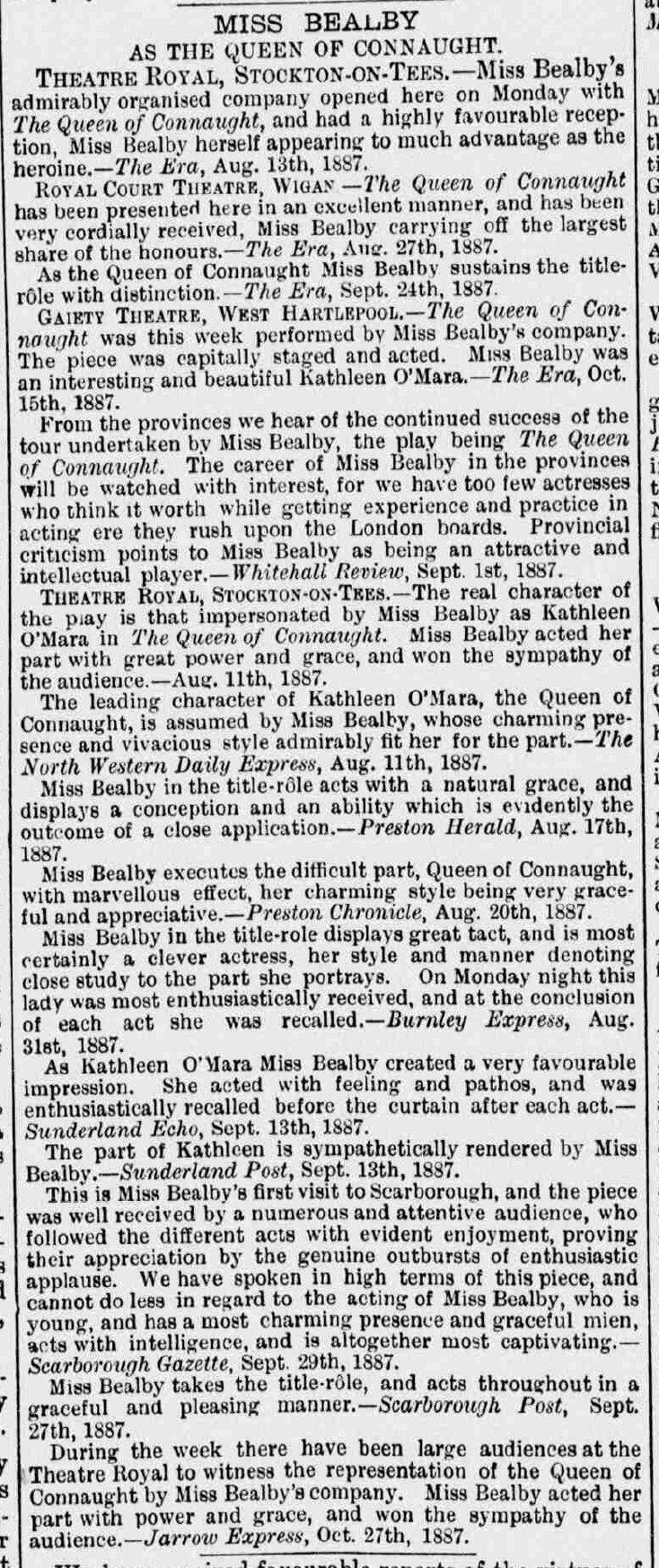

There was also a provincial tour in autumn, 1887, of a revised version of the play, starring Miss Bealby.

(Harriett Jay played the role of Kathleen O’Mara.)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

[Advert for The Queen of Connaught from The Times (Monday, 15 January, 1877 - p.8).]

The Daily Telegraph (17 January, 1877 - p.3)

OLYMPIC THEATRE.

“Time, the present day; scene, the seaboard wilds of Connaught.” If it were not for this emphatic announcement, deliberately adopted by the authors of the dramatised novel, “The Queen of Connaught,” coupled as it is with the assurance that “the subject is entirely contemporary, and depicts a kind of Irish life, character, and manners which have not been portrayed in any previous drama,” it might be well to dismiss any discussion concerning the probability or improbability of the scenes passing before us, the truth or the exaggeration contained in the sketches of character introduced to our notice, and the value or worthlessness of the present critical estimate of Irish temperament. If a dramatic author gives us a good play the greatest toleration will be extended to his method. Provided he interests us and is familiar with the ordinary healthy flow of the stream of human nature, we can afford to put up with his romancing, and are prepared to swallow even bigotry so long as the pill is pleasantly sugared. Let him be in earnest, and we shall be sure to follow him through the fields of his light and romantic imagination. As ill luck will have it, however, our authors, whilst taking credit to themselves for introducing a new form of Irish dramatic romance, so constantly startle their audience with the boldness of their assertions and the recklessness of their theories on Irish life in particular and human nature in general that the duty of protest is unhappily forced upon the critic, unless he is prepared to accept as a standpoint for discussion so distorted and crooked a view of life as this. The analyst of Celtic emotion and Irish enthusiasm, who in these enlightened days of toleration would go over to Connaught and Connemara to discover the brutality of the backwoods or the savagery of the goldfields, who would deny to the peasant of the seaboard wilds of the Emerald Isle one simple feeling inspired by sense of humanity or laws of civilisation, who insists that the Connemara social life of to-day is degraded by coarse and ruffianly outrage, and who elects for a heroine a woman who can find sympathy in no one whose mind is not warped by bigotry and obstinacy—must expect to be called in question when he exceeds the limits of probability and reason, and creates a difficulty in order to crush it. Supposing the Irish life depicted in this drama were true, or even half true, the method deliberately adopted by the authors of “The Queen of Connaught” would still be injudicious. The best and most successful dramas, Irish or English, are not those arranged from the study of one province, one district, one town, or from the mastery of the peculiarities of some deserted region in a civilised land, but from a general outlook over the vast fields of human nature. The “Colleen Bawn” was not successful because it gave us a picture of Killarney, but because it breathed in its story all the poetry, romance and charm of an impulsive and tenderhearted people; and it may fairly be held that it would have been a wiser course to depict for stage purposes not the “kind of Irish life, character, and manners which have not been portrayed in any previous drama,” but the Irish life with which all Ireland is eloquent. Dramatic licence has from time immemorial permitted ruined Irish maidens to be flung over “beetling cliffs” by their lovers, has sanctioned daring rescues under curiously improbable circumstances, and has distinctly authorised the incarceration of the aforesaid forlorn damsel in a ruined hut until she is required to appear at the close of the third act to confront the villain and to end the play. All this is legitimate enough. Our imaginations will follow an impetuous Irish girl over the mountains to rescue single-handed her lover from a den of desperadoes; but it was not necessary for the purpose of discussing the landlord and tenant grievances on the stage to ridicule Irish society and to degrade Irish character.

For who is the “Queen of Connaught” chosen for the heroine of our romance? A high-spirited girl in whose reformation we can alone take interest; a motherless woman who delights in the society of her father’s drunken and quarrelsome associates; a wayward spirit whose creed is to detest everything English; a curious mixture of good and evil who tends the sick and dying, and permits the embraces of her rejected lover when her husband’s back is turned; an anomaly who hardens her heart against the same husband because he is naturally indignant at the brutality of her kinsmen; and who sighs for the sympathy of some one who will permit homicides, roughs, priests, and toadies to swill whisky punch and smoke short pipes in her drawing-room! Before John Darlington, a high-minded, upright, liberal Englishman, has arrived in Connaught to purchase an estate and incur the hatred of his Celtic tenants, Kathleen O’Mara, the Queen of Connaught, has loved and been loved by her cousin, Randal Dooneen—loved him with a blindness incredible to any one who did not understand her bigotry and prejudices, for Randal is obviously a villain of the blackest character. But, though Kathleen has her anti-English prejudices, she is liberal enough in her sentiments towards her own race, since she harbours and swears to protect a wandering scamp called Anthony Dunbeg, who has killed a man in a drunken fight, and is flying from the law. There appears to be no limit to the toleration of Kathleen towards her kinsmen; but she does draw the line when she finds her cousin Randal caressing a peasant girl under her very eyes. Randal, angry at being discovered, pushes the poor girl over a cliff into the water; but Kathleen takes a deeper revenge by marrying John Darlington, the hated Saxon landlord. At this early period of the story it is patent to the meanest intelligence that the girl Nannie is not dead at all, that she has been rescued by Darlington, and that the climax of the whole drama is anticipated; but it is incredible that Darlington should keep such a secret in his breast and allow such a villain as Randal at large. Yet the authors of the play have not recognised these facts. Owing to some unexplained trait of heroism, Darlington saves the girl and says no more about it, dries his clothes, which have not suffered much from a swim after a drowning girl, overlooks the crime of murder, and is satisfied to win Kathleen and to take her hand in an Irish jig. So ends the first act, which is fairly bustling and lively; but, in addition to the grave fault of anticipating the conclusion of the drama, the act suffers from an accumulation of motive. Already the attention is a little confused owing to the three agencies of interest already running on parallel lines—first, the supposed murder of Nannie by Randal; secondly, the chase after Dunbeg, the homicide; thirdly, the love interest inspired by Kathleen. The marriage of the “Queen of Connaught” does not turn out well; but certainly from no fault of the husband. He is the most tolerant of husbands and good-natured of landlords. He restores cottages, drains his estate, gives health and happiness to the peasants, permits Randal, the murderer, to return to his wife’s society, sits calmly down when his father-in-law’s drunken friends are knocked headlong into the room, and only resents the insult of Dunbeg, who proposes to smoke a cutty pipe in his wife’s apartment. The more good-natured the man the more he is detested. The tenants revile him for making them clean, his wife jeers at him because he is English. He accepts his life, however, with the air of a martyr, a condition which well suits him when, to crown all, he is on very insufficient evidence accused of betraying Dunbeg when the latter is unearthed by the officers of the law. Dunbeg’s arrest is the picture concluding the second act. The angry storm gathering round the life of poor Darlington at last breaks. Everyone is against him. His faithful servant sells his life for a bribe. Randal arranges a scheme for his murder in the Distillers’ Cave in the wilds of Innishnamoe. Dunbeg comes back like a hunted tiger to kill him for betraying him to the police, and so he departs on a shooting excursion, which is to end in his death. At last the Queen of Connaught is aroused. Her creed stops short at such a crime as this; so, hurrying off through the darkness of a wild night, she rescues her husband from death, and is the central figure in the oldest and most popular melodramatic situation in the world. A certain picturesqueness of scene, a hurry of interest, and the intense and admirable oratory of Miss Ada Cavendish, saved the drama at this its important point. Unquestionably the climax of the act is unduly prolonged, but the instant the heroine appears in true and heroic colours the play revives. Before this moment she has inspired but languid interest, but at this dramatic moment the somewhat humiliating position of Darlington hiding for protection behind the petticoats of his wife is overlooked in the excitement of the scene. Miss Cavendish caught the true dramatic ring of the scene at the right moment, and the curtain fell upon the best applause of the whole evening. Still the Celtic hunger for Darlington’s life is not satisfied. Another plot is arranged for the murder of the Englishman under his own roof, but it is arrested by the sudden reformation of Dunbeg, who comes to do the deed, and the equally sudden outburst of affection on the part of Mrs. Darlington. It is not very clear why Dunbeg drops the revolver at Darlington’s feet and bursts into a wail of agonised remorse, or why the heart of Kathleen is softened towards her excellent husband; but so it turns out. Justice, therefore, only requires the unmasking of Randal and the return of Nannie, and justice is satisfied accordingly, although the whole thing had been patent to the audience very shortly after the play began. The piece is not destitute of action nor wanting in colour. If it contains little surprise it is charged with occasional bursts of excitement, which are invariably popular. The great defect is an unfortunate want of sympathy between the audience and the heroine, and the tendency of the authors to spoil their case by misrepresenting the character they desire to reform. In a novel it is possible to tone down much of this by description and essay; but in a drama the author is compelled to put his case in the briefest and boldest manner possible. It is a sure sign of a defect of treatment when the audience constantly finds itself arguing with the author and resisting the logic of his conclusions.

The task of impersonating the heroine of this drama is one of no ordinary difficulty. A certain traditional sympathy belongs of right to the good genius of melodrama, and especially has this been the case when the scene of it has been laid in Ireland. The authors of the “Queen of Connaught” having, however, taken an exceptional course, there fell to the artist who represented the character an uphill struggle. But, though most things were against her in the trial of skill, Miss Ada Cavendish never once lost heart. A natural nervousness for a time checked the full flow of impassioned utterance, but directly the artist had got over the excitement caused by an unusually hearty reception she triumphed over every difficulty. Miss Cavendish carefully divided the character, complex and difficult as it was, into four distinct and carefully marked periods. First, the maiden in the full and happy glow of her freedom, proud of her position, proud of her family, and prouder still of the traditions of her race; next, the disappointed wife, impatient of correction and obstinately defiant; thirdly, the true woman, touched at last with a generous impulse and nerved with an heroic daring; lastly, the contrite and repentant wife, as boundless in her love as she had before been pitiless in her reproaches. Such characters as these, with great difficulties to contend against, increase considerably the art-work bestowed upon them. Authors are over and over again helped out of the wood by actors and actresses alike; but seldom has an interest been more directly supplied by an actress than in the case of Miss Ada Cavendish as the Queen of Connaught. Mr. Henry Neville, the hero of the play, with whom all sympathy remains, has seldom of late years acted with such quiet force, such healthy reserve, and such forgetfulness of self. He forgot the buoyant and pleasant manner which makes most characters he undertakes pleasant, but tinges them with the same colour, and he appeared with a dignity and a repose foreign to his style, but particularly welcome. He was not the typical hero of romance, but the thoughtful man of the world, and the play gained strength in all the scenes in which Mr. Neville was interested. The most striking and difficult character in the play was, however, that entrusted to Mr. Flockton, who acted Anthony Dunbeg, the homicide, with picturesque force and very remarkable vigour. The uncertainty and inconsistency of the piece, transparent in all its details, were very marked in connection with Dunbeg, now a wandering beggar, now a tipsy adventurer, now a riotous brawler, now a wild hunted animal craving for revenge, and now a repentant man, paralysed with the recollection of his misdeeds. Mr Flockton, hitherto merely associated with excellently defined polite character, nerved himself for the task, and attacked it with vigour. His intensity and his marked purpose soon made themselves felt; but it was not until Dunbeg’s final scene that Mr. Flockton received the most pronounced appreciation of the audience. By taking his confession in a singularly quiet and impressive key, with voice half-broken by sobs and frame convulsively agitated, the actor at once showed the value of change of tone—as true in acting as in music. The repentant appeal for mercy made by the vagabond outcast so touched the house that Mr. Flockton was rewarded by one of the heartiest recognitions expressed throughout the evening. Always in the picture, always in earnest, and always acting with meaning, Mr. Flockton at once makes a long advance with this sketch of elaborate and difficult character, faintly suggested by the authors, but intensified by the artistic feeling of the actor. Amongst the other pleasant features of the acting may be cited the true and tender hearted Norah Kenmare of Miss Camille Dubois—the most womanly and natural of all the female characters—and the Nannie of Miss Carlisle, who was of great assistance in several difficult and risky scenes. Mr. J. A. Arnold played the villain in a stilted, stereotyped, and mannered style, now, happily, out of fashion; and Mr. W. J. Hill, a clever comedian, is obviously not at home in the character of an Irish servant. It will, no doubt, be generally remarked that the drama throughout was quite deficient in that Irish humour, spirit, and vivacity characteristic of Irish pieces, and giving them an irresistible impulse. Under ordinary circumstances an Irish drama destitute of brogue and what is known as “Irish acting” would be voted a dull affair, but it is less noticeable when the tone of the play is so essentially devoid of Irish feeling. It would be heresy to play “The Colleen Bawn” or “Arrah-na-Pogue” with an English Danny Mann or a Saxon Shaun; but few in the audience could have been sensible of the Irish atmosphere or influence during the representation of the “Queen of Connaught.” If cheers, calls, and requests for the authors make up a success, then the dramatised version of a popular novel will please those who admired the book—and no doubt many more who have never read it.

___

The Times (18 January, 1877 - p.9)

THE THEATRES.

_____

The management of the Olympic has but poorly consulted its own interests in the advertisement with which it has prefaced the programme to its new play, the Queen of Connaught. We are required to believe that this play, of which the subject is “entirely contemporary,” depicts a kind of “Irish life, character, and manner, which has not been portrayed in any previous drama.” We may read a fairy story with very great pleasure as a fairy story, but if we are gravely desired to accept it as a narrative of actual fact, and to believe that jewels really did fall and may again fall from the mouths of good princesses, and toads and reptiles from the mouths of bad princesses, the story ceases to amuse us. Now, as a matter of fact, Irish life as depicted in the Queen of Connaught appears to us to be remarkably like Irish life as depicted in any other Irish melodrama we ever saw, save that, perhaps, it may be a little less like the reality. The whole play is, as it seems to us, but a compound of pretty nearly every Irish piece that has been on the boards within this generation, with a spice of Maxwell’s “Irish Rebellion” for flavour. The good and bad characters are pretty much as usual; there is a most unconscionable villain; a headstrong Irish girl, rather more headstrong perhaps than she has generally appeared to us; a pretty peasant girl, whose affections are “trifled with,” whose life is attempted, but who passes with safety through both ordeals, and appears in the nick of time to confound the machinations of the villain; there is a comic servant, and the usual proportion of “boys,” who are equally ready to die for or to kill “the master,” on the slightest provocation. There is, to be sure, some attempt at originality in the character of the heroine, who gives her name to the piece, but it is a distorted and unnatural character, and for our part we much prefer some good old conventional type, endeared by long and pleasant familiarity, than originality such as this. So much for the claim of novelty. With regard to the piece itself, there is a fair amount of life and action about it; and the third act concludes with a powerful and picturesque scene, though of a very familiar type. The play is, in short, a fairly good melodrama of the school with which Mr. Boucicault has made our stage familiar. In such works no great literary skill is generally to be found, nor perhaps even required, and its absence here cannot be regarded as abnormal. If it had not been for that unfortunate advertisement, the responsibility of which the authors and the management must, in the absence of any definite information, be content to share, though it would have been impossible greatly to praise the Queen of Connaught, it would not have been necessary to linger over its defects. The best acting in the play is unquestionably shown by Mr. Flockton in the character of Anthony Dunbeg. The man, who has taken life in a drunken brawl, is a fugitive from justice, and believing himself to have been betrayed by the hero, the English owner of an Irish estate, is determined, in revenge, to add the crime of murder to that of manslaughter, but fortunately discovers hsi mistake before he has satisfied his vengeance. This character Mr. Flockton represents with much power, and, in general, with a just avoidance of exaggeration. In the last scene, where he discovers and owns his mistake, he is much to be praised for the quiet of his tone and bearing which are yet full of strong force and pathos. The part of the heroine is played by Miss Cavendish with animation and correctness; but it is an unnatural and something of an unpleasant part, and Miss Cavendish, though a skilled and powerful actress, is somewhat lacking in variety of expression, and too generally dependent on her author to be able to conceal these facts. Mr. Neville, as the hero, John Darlington, is pretty much like Mr. Neville in most of his late characters, and Mr. Hill’s vein of humour is not suited to the representation of an Irish servant. Both Miss Carlisle and Miss Dubois do the little they have to do in a satisfactory manner; but the playbill says all that is necessary to say of the other characters.

___

The Illustrated London News (20 January, 1877 - p.19)

THEATRES.

OLYMPIC.

The commencement of the really dramatic season may now with comparative safety be formally announced; and it has been inaugurated at the Wych-street theatre by the return of Miss Ada Cavendish to its boards, with a new play. The title of the drama is “The Queen of Connaught.” It is divided into four acts, stated to be dramatised from “the popular novel of the same name.” The names of the dramatists are not given, though we understand that Mr. Robert Buchanan is one. If so, the present drama is a marked improvement on his “Corinne,” which had the misfortune of a collapse so lately at the Lyceum. The conduct of the action is, on the whole, satisfactory, and the several acts are worked up to a climax. The action itself is of a melodramatic kind, consisting of small incidents capable of being worked up into stage effects, and being produced as such with considerable power and skill. The characters are, on the whole, well and accurately drawn; but the dialogue might have been more carefully written. There is in it little of poetical sentiment, and its eloquence is of a very colloquial kind. The style is rhetorical rather than natural, with but few happy phrases and very little imagery. The interest is of the old-fashioned kind in Irish plays, in which the national character is exhibited as deficient in civilisation, rude in manners, and altogether wanting in morality and obedience to the law. The story might have been attributed to any period of the history of Ireland; but we are gravely told that it is of a contemporary kind, and that there are “parts of Connaught which are still under proclamation, and where a special ‘permit’ is required to carry arms.” The authors confess, however, that “few cases of violence have occurred during the last two or three years.” The subject of the present play is a case of violence, and the incidents are all cases of violence, differing in nothing from those which frequently occurred some half century ago. Do the authors mean to tell us that Connaught has failed to partake of the general improvement in other places? Perhaps. For what says the story? That an Englishman married an Irish lady of the O’Mara family, who, on the score of her ancestry, is entitled to the honour of being called “the Queen” of the locality. Her husband is a man of wealth, and anxious to dispose of it in the improvement of estates in the neighbourhood and the general condition of the people. But the vulgar still adhere to their own ways, and prefer a mud hut to a decent house, the native bog to a deal floor, a hole in the bottom of the mud to a regular grate for containing a fire, and another hole in the top of the ceiling for the smoke to escape by, to a regular chimney. Mr. John Darlington (for that is the name of the hero), is disgusted, and still more so with the rude measure of hospitality required by ancient custom, making his residence a sort of public tavern. All these things are native to Kathleen O’Mara, whom he has married, and the lady is as much disappointed almost as her tenantry at the coldness of his manner and the fastidiousness of his taste. She wonders, indeed, why he cannot leave things as they are, seeing that the people would be contented and happy with them, and resist all attempts at their improvement. Warnings of their dislikes are given in abundance, but Darlington bravely despises their threats and remonstrances. A former lover of “the Queen,” Randal Dooneen, encourages rebellion against his authority, and even plans his assassination, hoping for an ultimate marriage with his “widdy.” This fellow has already sought to drown a peasant girl whom he had promised to wed; but she is saved by Darlington, and in the last act comes forward to denounce the villain and exculpate the husband, who is supposed to have given up a kinsman to the law, seeking refuge in the castle and charged with manslaughter. It is Randal who was guilty of the meanness, not Darlington; and thus, in the end, Kathleen is made to see that her husband is a superior kind of person—one entitled to her obedience as a wife, and likely to reform the people resident on his estates. This notion of utilising the stage, by teaching from it the notions of political economy and giving the Irish a lesson in domestic morals, peradventure, merits encouragement, and is likely to receive it from the hands of an Olympic audience. The piece has been well mounted, and is, probably, as well acted as it can be. Miss Ada Cavendish distinguished herself as a declaimer in many passages of Kathleen, and acted the rôle throughout with evident care and precision. Mr. Neville, as the English husband, was quiet and characteristic, and won on the sympathy of the house. The part of Randal Dooneen was supported by Mr. J. A. Arnold, an American actor, who made in it his first appearance in London. Mr. Flockton made a point with Anthony Dunby, the homicide who sought refuge from “the Queen;” and an Irish servant by Mr. W. J. Hill stood out as a speciality, cool and collected and ready for any atrocity. The drama was received with approbation, and, on the fall of the curtain, the principal performers were called forward and vehemently applauded.

___

The Week’s News (20 January, 1877)

Theatrical and Musical.

_____

A new play, entitled “The Queen of Connaught,” was produced at the Olympic Theatre on Jan. 15. The play is founded on a novel bearing the same name. Mr. John Darlington, a wealthy roving Englishman of reserved manners, but noble disposition, purchases an estate in the neighbourhood of Connemara and marries Kathleen O’Mara, a young lady of ancient but decayed family, who, before bestowing her hand upon him, had made him promise that he would reside altogether in Ireland and devote his time and fortune to the hopeful task of reviving the faded glories of her house. Of this covenant he is honourably observant. All his good offices, however, only result in drawing down upon him the vengeance and ill-will of the very peasantry whom he seeks to befriend, and who denounce him for a proud, cold-hearted Saxon. This is sufficiently mortifying, but what aggravates his disappointment beyond endurance is to find that he is misjudged by his wife, who, full of romantic anguish about the so-called sorrows and sufferings of the Celtic race, continually taunts him with “misunderstanding” the people amongst whom it is his misfortune to dwell. At last a cruel suspicion falls upon him—that of having violated the rights of hospitality by surrendering to justice Anthony Dunbeg, a homicide, who, on the plea of remote consanguinity with the O’Maras, had sought sanctuary in his house. He had done no such thing; the man who had given information to the police being in reality no other than Kathleen’s own cousin and former lover, a certain Randal Dooneen, who himself was in no better case than the scoundrel he had hunted down, having attempted to drown Nannie Crogan, a peasant girl whom he had basely betrayed, but whom Darlington had rescued. Threatening letters reach him by every post, and dastardly plots are laid against his life. His wife, though she had at first mistrusted him, at last learns to love and admire him, and the scene in which the interest of the story is presumed to reach the highest point of excitement is that in which, having tracked him at night to a cave in the wilds of Innishnamoe, whither he had been lured by his would-be assassins, she exercises her traditional authority as Queen of Connaught and rescues him from their murderous hands. The rest of the play is devoted to the exposure of Randal’s villanies, the comfortable bestowal of Mr. Dunbeg, the fugitive homicide, who hardly deserves so much consideration, and the re-establishment of friendly relations among persons who had grievously misunderstood one another. In the representation it derives its chief attraction from the admirable acting of Miss Ada Cavendish as Kathleen O’Mara, and Mr. Neville’s spirited and genial performance of Darlington. Mr. Flockton is also to be commended for his clever impersonation of Dunbeg. The scenery, mainly consisting of mountain landscapes, is excellently painted.

___

Lloyd’s Weekly London Newspaper (21 January, 1877 - p.5)

PUBLIC AMUSEMENTS.

_____

OLYMPIC THEATRE.

In a note appended to the programme announcing The Queen of Connaught at this house, the public were told:—“The subject is entirely contemporary, and depicts a kind of Irish life, character, and manner, which has not been portrayed in any previous drama.” After this, when on Tuesday evening a by no means crowded audience found themselves witnessing a badly constructed play of the old-fashioned type, made familiar by The Colleen Bawn, Peep o’ Day, and a score of other pieces, some not unnatural surprise was excited. The new play is put forth as a “new and picturesque comedy-drama;” but no attempt is made to introduce anything like a comedy element into it. There is the familiar “colleen,” Kathleen O’Mara, with two lovers—a wealthy young Englishman (John Darlington), and an Irish cousin (Randal Dooneen), the latter a villain, who in the first act pushes a peasant girl whom he has betrayed into a deadly stream. An impecunious squire, a priest, a comic servant, a murderer, and a number of “boys” complete the number of well-known stage personages. The great defect of the plot is that it lacks interest, and it is impossible for the audience to sympathise with any of the characters. Kathleen, a romantic girl, known as the “Queen of Connaught,” marries the Englishman, but first insists that he shall conform to Irish tastes and habits. This of course he promises to do, though he afterwards finds it impossible to carry out, and is accordingly the object of suspicion and threatening. The tenants for whom he builds new houses resent his interference, whisky-drinking friends of his wife’s father vote him a milksop, and when finally he is supposed to have rendered up the murderer Dunbeg (a remote relative of the O’Maras) to justice, his own wife turns against him. After being lured into the “Distillers’ Cave, in the Wilds of Innishnamoe,” Darlington is about to be assassinated by the “boys,” when he is rescued by Kathleen. Finally it is made clear that Randal Dooneen is the betrayer, and he is arrested by the police, the poor peasant girl whom he attempted to murder, and who was rescued by the Englishman, appearing against him. There is some really good writing in the piece, but dialogue goes for little in a drama which depends upon thrilling incidents and strong situations. Miss Ada Cavendish made a very earnest and impassioned Kathleen, and was received with abundant applause. The easy manliness and force of Mr. Neville enabled him to give prominence to the character of the Englishman; but the chief acting part fell to Mr. Flockton, who displayed much intensity as Dunbeg. Mr. Arnold was good as the villain, Randal; Miss Carlisle struggled successfully with the very unthankful part of the betrayed peasant girl; and Miss C. Dubois made an exceedingly bright and charming Cousin Norah. Mr. Hill was very comic as the servant, but had little o’ the Irishman about him. The authorship of the play is not acknowledged; but rumour asserts that Mr. Robert Buchanan has had a hand in it.

___

The Examiner (27 January, 1877)

The value of a comma is great, but has perhaps never been so distinctly evidenced as in the review of the ‘Queen of Connaught,’ in Public Opinion, from which we quote the following:—“Who wrote ‘The Queen of Connaught,’ one of the most popular novels of last year? Rumour says, Mr. Robert Buchanan’s sister-in-law. Who has dramatised it? The same saucy jade, says Mr. Buchanan.” What Public Opinion means is not at first by any means clear. It does not, however, intend any rudeness, but there should be no comma after the word “jade.”

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

[Advert for The Queen of Connaught from The Times (29 January, 1877 - p.8).]

The Belfast News-Letter (6 February, 1877 - p.3)

LONDON CORRESPONDENCE.

(FROM OUR CORRESPONDENT.)

LONDON, SATURDAY.

. . .

I am informed that Mr. Hepworth Dixon’s novel entitled, “Diana Lady Lyle,” issued to-day by Messrs. Hurst & Blackett, is to be dramatized for the Olympic Theatre, and that the “Queen of Connaught” is to be withdrawn. So many rumours are in circulation with reference to the authorship of the latter piece that it may be well to give the fact. It is generally attributed to Mr. Robert Buchanan, the Scotch poet, who has lately been residing in Ireland; but the real culprit is a lady—a Miss Jay—a relative of his whose knowledge of your country is neither extensive nor accurate. She it was who wrote the novel of the same name, and the poet is responsible only for the dramatized version. Miss Jay is a very agreeable little lady, and in her delineation of Irish character has perhaps drawn too largely upon the assumption that a pretty woman can do anything.

___

The Spirit of the Times (New York) (10 February, 1877 - p.16)

THE DRAMA IN LONDON.

_____

Another Failure at the Olympic—A Lebellous Irish Drama—The

Peculiarities of W. J. Gilbert—Revival of Pygmalion and Galatea—

Activity in Theatrical Cuircles—New Comic and Burlesque Plays—

Mr. Compton’s Benefit—The Pantomimes Better Patronized.

[FROM OUR OWN CORRESPONDENT.]

LONDON, Jan. 20, 1877.

DEAR SPIRIT: Mr. Henry Neville, the spirited manager of the Olympic Theatre, has once more played high for a success, and has lost. ...

The latest attempt in the way of startling dramatic literature is an Irish drama written by a Scotchman! Mr. Robert Buchanan, the poet, the antagonist of Swinburne, the pamphleteer, the journalist, the everything by turns, and nothing much, has, with the assistance of his sister-in-law, written a novel called “The Queen of Connaught.” The novel was well received, and then the gifted Scotch writer and his kinswoman resolved to dramatize the book, and to tell the world at large that the accepted Irish drama, as beloved by every nation under the sun was contemptible, weak, bad, untrue, and inaccurate. Mr. Robert Buchanan & Co. have accordingly written a drama on a new principle. They have resolved to discard sentiment, and to tell the truth. Having resided for some time on the “sea-board wilds of Connaught,” they resolved to tell the truth about the Irish nation, and to use the stage as a debating ground on which to discuss the landlord and tenant question, and the recently passed Land Act of Mr. Gladstone’s administration. When Buchanan takes up his pen to determine to spiflicate Boucicault, to crush Gerald Griffin, to ostracise Bagle Bernard, to put Mr. Falconer on his back, to correct John Brougham, and to put the Irish drama on a correct and proper footing, Buchanan the hard-headed, unromantic, unideal Scotchman fairly tells us that he is sick of the sentiment of Irish plays, and declares that in “The Queen of Connaught” he will tell the truth. A more impudent libel on a generous country was never put forth in the form of a drama. The heroine is a weak, obstinate, hard-hearted creature, who can tolerate no one who is not saturated with bigoted prejudice. The peasants are liars to a man, and cowards who stab their enemies in the dark. Connemara society is represented by a set of drunken savages, who quarrel over their cups, behave like beasts in a lady’s drawing room, and insult her and her guests by smoking dirty clay pipes over their whisky-toddy. They fight, they scramble, and they tear one another like wild beasts. Their sole bond of union is hatred of anything English, and the sole object of existence on the stage is to show a civilized nation like the English that the Irish are blacker than they ever yet were painted by any novelist or dramatist, alive or dead. Apart from the party question, which is introduced in the worst possible taste, the play is a bad play, uninteresting in subject, and crude in design.

The dramatic critic of the Daily Telegraph took the earliest opportunity of protesting against the Irish libel perpetrated by the authors of “The Queen of Connaught.” He showed that the stage was not a place for polemical discussion, and he declared emphatically that this was no true picture of Irish life. It is unfair and unsound to make general accusations on the strength of particular instances, and the Telegraph critic called the playgoer to witness whether the romantic idealism of Mr. Boucicault’s plays were not truer, and healthier, and more acceptable than these jaundiced theories of prejudiced minds. The critic spoke from a double motive. He disbelieved in the picture of Irish life, and he objected to the dramatic principle on which “The Queen of Connaught” was constructed, and what followed.

The authors of the play answered the criticism in a letter a column long, and in their reply exaggerated the previous libels. They asserted dogmatically that Irish humor was a fiction which ought to be exploded; that Irish sentiment was a myth; that Irish sentiment was a delusion in the brains of Irish dramatists, and that their experience of the County Connaught was fairly recorded in the play. Everyone expected that this attack on Ireland would have raised the spirit of the Irish. Everyone believed that shillalaghs would be out, and that there would be a mighty cracking of heads.

If Boucicault had been in London he would have buckled on his armor. But, I am ashamed to say, that not one champion has been found for Ireland, but the anonymous dramatic critic of the Daily Telegraph. The Emerald Isle has accepted the rebuff of Robert Buchanan, the Scotchman, and not one word of protest has been called forth by his play or his letter. The fight has ended without even so much as one cheer for the champion, and the Queen of Connaught continues to be played with all its original sin thick upon it. I do wish that Mr. Boucicault had been in London to stand up for the country he loves, and to indorse the dramatic faith, of which he has been so eloquent an apostle. It is too dreadful that Scotch poets should be permitted to deny to this charming country its inherent humor, and its traditional romance.

___

The Victoria Magazine (March, 1877)

THE OLYMPIC.—A brief preamble on the programme of the “Queen of Connaught,” lately produced at this theatre, informs us that “The leading incidents and personages of this play are founded on the popular novel of the same name. The subject is entirely contemporary, and depicts a kind of Irish life, character, and manners, which has not been portrayed in any previous drama.” We must confess that the last paragraph of this little preface strikes us in a somewhat droll light; for certainly the play depicts a kind of Irish life that has no existence in reality in our day, though it had fifty or sixty years ago, and so far it is well for the stage that it never has been depicted before. There are a few features in which may be recognised—though even here without a touch of the Irish genus which alone can give truthful vivacity to the picture—elements still, unhappily marring so much that is noble and beautiful in Irish life. But speaking generally the “Queen of Connaught” is a burlesque upon Irish contemporary history. We are asked to recognise in vulgar, dissolute fellows, who dress like peasants, but have not a particle of the politesse of the Irish peasant, who drink whisky and get drunk in a lady’s drawing-room, and put their feet on her velvet chairs, types of the gentry of Connaught; and in the lady who delights in the society of these ale-house tipplers, and sees in them noble specimens of Erin’s sons, a type of a well- born lady of Connaught. The priest joins the unseemly revel, and does not think it necessary to interfere till the “gentlemen” fall out and nearly exchange blows in the lady’s drawing-room, and in her presence, and the “factotum” of the household, a dirty scamp, appears to be hail-fellow-well-met with the kinsmen and acquaintance of his mistress. A clap-trap phrase here and there about “the noblest people in the world” does not mitigate the absurdity of a picture, which if correct, nullifies the clap-trap. It is a slander, but a slander on the face of it so outrageous as to be at once apparent; at any rate only the “gods” could be ignorant enough to believe that even in the wilds of Connemara, Irish gentlemen behaved like English costermongers, and dressed like bog trotters. We say English costermongers, because the play is Irish only in name. If Juliet’s statement is true, and “that which we call a rose, by any other name would smell as sweet,” its converse is true also. An Irish name will not make an Irishman, and so such names as O’Mara, and Croghan, and Norah, cannot make Irish people. Here the fault is partly that of the actors. English people can rarely—if ever—faithfully represent Irish people, and their attempts at the brogue are so unsatisfactory as to make one wish that they would be content to speak English, especially as the “gentlemen” are in this play frequently credited with vulgarisms only found among the peasantry. Turning to the plot of the piece, we cannot find anything to soften the bad effect of the general tone of the drama. We have the worst elements of an Adelphi melo-drama—and one of these perilously like a plagiarism of the “Colleen Bawn”—without any of the cleverness, brightness, and racy fun of Boucicault’s Irish pieces. It is unnecessary to recapitulate the framework of a plot with which all our readers must now be familiar, but we may observe that Kathleen’s belief in her husband’s breach of hospitality with regard to Dunbeg is extremely unnatural; that the throwing of Nannie Croghan over the rock shows the true melo-dramatic disregard of probabilities, seeing that the spot was in the castle-yard and in full sight of the windows, and that the final exit of Randal in the last scene is not only a failure of poetic justice, but shows the lack of knowledge of the Irish people that is displayed throughout the piece—though for this the author of the novel may not be responsible. The peasants have just discovered that Doneen has betrayed and deceived them, that he, their own countryman, and not Darlington, is that loathed and despised being, an “informer,” and they suffer him to depart through their midst with no display of animosity more formidable than a groan and a hiss. We would not in a like case in real Irish life stand surety for Doneen’s life. It is a more pleasing task to speak of the acting, which we consider entirely apart from any portrayal of national characteristics. We have said that the actors are entirely English. Their names, and their names alone, are Irish. Miss Ada Cavendish, wisely foregoing any essay at the brogue, shows herself the true artist she is, working admirably in a character which is wholly unnatural and never enlists our entire sympathies. With much talk of heroism, Miss O’Mara only once—in the finest scene in the whole piece (that in the cave at Innishannamoe)—rises to the heroic. The Queen of Connaught loves to associate with ruffians and drunkards; marries a man whom she despises for his English birth, in order to save the family estates; permits the man with whom she was in love when she married, and whom she dismissed her presence for his liaison with a peasant girl, to enter her husband’s house, and make downright love to her before she checks him; turns her drawing-room into a bar-parlour; quarrels with her husband because he builds decent cottages in place of mud huts, and only awakens to a sense of her duty when she hears that an ambush is laid for John Darlington. Only such powerful, sympathetic, and refined acting as that of Miss Ada Cavendish can make tolerable a character so uninteresting—so, in some things, actually repulsive. Where there is failure it is more the fault of the part—not of the artist. We use this qualified form of expression because it may be doubted whether Miss Cavendish is suited for the rôle of a “wild Irish girl.” Her sparkle is that of cities and courts; her very speech betrays the breeding of a polished life. We are compelled, therefore, to dissociate the artist, to a considerable extent, from the part, and look upon the portrayal rather in the abstract than in the concrete, and from this point of view, Miss Cavendish fully sustains a reputation earned by legitimate means. Her elocution is at all times admirable, and if here and there certain mannerisms of intonation and gesture are apparent, it is hardly possible to find an artist without them. She has done for Kathleen O’Mara more than the author has done for her, and for this he (or she) and the public have good reason to be grateful to her. Mr. Neville’s Darlington is a thorough gentleman—the only one in the piece—and though as a character somewhat sketchy, Mr. Neville contrives by the quiet force and sympathy of his acting to give it prominence, and as Darlington is also the only person (save Norah Kenmare) not deeply tinged with knavery, his noble qualities are the more welcome, and could not be better portrayed by any artist on the stage than by Mr. Neville, who shows in this play, by the way, that the gallant Lagardère, the “devil-may-care” Clancarty, the rough Bob Brierly, can also be the quiet, almost lymphatic, typical Englishman. Of the minor characters not much need be said. Mr. J. W. Hill is an amusing Shaun O’Kelly; Mr. Flockton an unnecessarily vulgar Dunbeg, while Mr. Vollaire as “The O’Mara,” Mr. Arnold as Randal Doneen, and Mr. Baer as the priest, are all fairly successful. Norah Kenmare is attractively rendered by Mlle. Camille Dubois, and Miss Carlisle as Nannie Croghan acted with a force and passion of which her portrayal of Blanche de Nevers gave no promise. The scenery, especially the Distiller’s Cave at night, was highly effective.

___

The Era (23 December, 1877 - p.12)

THE DRAMATIC YEAR

_____

. . .

The original plays cannot, however, be dismissed without an allusion to The Queen of Connaught, supposed to have been written by Robert Buchanan, the poet. The play was not altogether successful, but it was clever, and would have succeeded better had not the author determined to upset all our theories on the subject of Irish character. He is a bold man who flies in the face of “stage tradition,” and pulls down our dramatic idols in order to burn them before our very eyes.

___

The New York Times (6 January, 1878)

An extract from ‘The English Stage: Story of the Year’:

Mr. Robert Buchanan probably finds a new cause for feeling bitterly against all mankind because “The Queen of Connaught” did not make his nor the fortune of Mr. Neville at the Olympic. The drama was not without merit but the action of the play was worked out on the poorest models, and the situations were forced and unnatural. You may possibly have an opportunity for judging for yourself how far London was right in rejecting “The Queen of Connaught” as Miss Ada Cavendish will be with you next year and this drama is in her répertoire.

___

The Daily News (19 November, 1880)

CRYSTAL PALACE.—The revival of The Queen of Connaught, as one of the afternoon performances in the Theatre of the Crystal Palace, derives an additional interest from the first appearance in the part of the heroine of the young lady who is the author of the remarkable novel on which this play is founded, and also joint author of the stage adaptation. Miss Jay is a lady possessing many qualifications for the position of leading actress in romantic drama. She has a fine expressive countenance, a graceful figure of the full middle height, and a voice which is not wanting in power, and is probably capable, under good training, of excellent effect both in light and pathetic utterances. Unfortunately she is as yet but little skilled in the arts of the stage. Her movements are not ungraceful, but they are somewhat timid and constrained; she has no adequate command of those little resources by which the practised actress is able to make her presence felt, even when she is taking no part in the dialogue; and moreover her delivery is rather distressingly formal. This latter defect was apparently exaggerated in some degree from her efforts to reach what actors call the “pitch,” of a theatre by no means favourable for conducting the sound of the voice. It will be fair therefore not to judge her from the performance of yesterday afternoon any further than to say that her impersonation, in spite of its technical deficiencies, is of sufficient promise to give hope that Miss Jay will eventually take a place in the leading ranks of her new profession. Her efforts were well supported by Mr. Henry Neville, Miss Jecks, Mr. Brooke, Mr. Proctor, and the other members of the rather strong company assembled; and the play, with its picturesque and quaint scenes of life in the West of Ireland, appeared to afford much pleasure to a large audience.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

[Press notices of Harriett Jay in The Queen of Connaught from The Era (28 November, 1880).]

___

The Dundee Evening Telegraph (8 September, 1882 - p.2)

THEATRE ROYAL.

To-night at the Theatre Royal Mr Charles Dornton’s company will perform, for the first time in Dundee, the celebrated Olympic drama “The Queen of Connaught.” The play is, we believe, a dramatised version by Mr Robert Buchanan of the stirring Irish tale of the same name by which Miss Harriet Jay, the talented young actress, first attracted attention as a novelist; and as the story abounds in striking situations and forcibly drawn characters, the drama may reasonably be expected to be of more than usual interest and merit. It is to be repeated to-morrow evening, with the principal scenes from “The Drunkard.”

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

[Advert from The Era (23 April, 1887 - p.4).]

The Era (11 June, 1887 - p.8)

We are requested by Mr Robert Buchanan to state that the new and revised version of The Queen of Connaught has been secured for an autumn tour by Miss Bealby, under the direction of Mr Henry Neville. A number of first-class towns, however, have been reserved by the authors. The Queen of Connaught, originally produced at the Olympic Theatre, under Mr Neville’s management, has been entirely rewritten and rearranged in view of recent political events, and in this altered form will shortly be reproduced by Mr Buchanan in the metropolis.

___

Sunderland Daily Echo (13 September, 1887 - p.3)

“THE QUEEN OF CONNAUGHT”

AT THE THEATRE ROYAL.

Last night, a company, at the head of which is Miss Bealby, appeared at the Theatre Royal, Bedford-street, in the drama “The Queen of Connaught.” As the title partly indicates, “The Queen of Connaught” is an Irish drama, and has been adapted to the stage from a novel by Miss Harriet Jay. It is supposed to represent the Irish life of the present day, but it is much exaggerated. The piece may be briefly described. Capt. John Darlington, who has extensive estates in Ireland, marries Kathleen O’Mara, the Queen of Connaught, whose hand had been sought by her cousin, Randell Dooneen. Darlington is hunted down by Dooneen, upon whose life he makes several unsuccessful attempts. However, at last Dooneen is discovered, and the real cause of the discontent of the peasantry against the English landowner is made known. As Kathleen O’Mara, Miss Bealby created a very favourable impression. She acted with feeling and pathos, and was enthusiastically called before the curtain after each act. The part of Captain John Darlington could not have been in better hands than those of Mr Charles Macdona, who gave a very forcible and natural impersonation of the hero. Mr Ed. Falcon was very good as Anthony Dunbeg, a homicide, and Mr. R. C. Leighton, as the villain, earned the appreciative hisses of the audience. The character of Michael Crogan was fittingly represented by Mr. A. C. Percy, and Miss Elsie Chester made a capital Nannie Crogan, whom the villain Dooneen had dishonoured. There was a large attendance, and, judging from the loud applause which followed each act, the drama is likely to draw large audiences during the week.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

[From The Era (5 November, 1887 - p.16).]

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

[Poster advertising Miss Bealby in The Queen of Connaught at the Theatre Royal, Stockton, 1887.]

From Chapter XXIV of Robert Buchanan by Harriett Jay:

But so far from daunting him these failures only acted as an incentive to fresh efforts, and his next bid for theatrical success came in the shape of a dramatic version of my first novel, “The Queen of Connaught.” There are one or two circumstances in connection with this play which it may be interesting to relate. The book, which was issued anonymously, was received most kindly by the critics, and met with great and instantaneous success. “You will observe with amusement” (wrote Mr. Buchanan) “that all the writers think the author is a ‘he.’” This indeed was the case, and in many quarters the book was spoken of as the work of Charles Reade. Fearing the great author’s anger, I wrote him a letter of apology, telling him that I was only a beginner in the art which I had adopted under circumstances so auspicious, and finally assuring him that I had had no hand whatever in the circulation of the reports which connected the book with his name. The reply which I received was courteous and kindly in the extreme. Mr. Reade began by congratulating me on the success which I had obtained so early in my career. He urged me not to lose my head over it, or to be too eager to rush into the market with another book. “Rest on your laurels,” said he, “and be careful to fill up the teapot before you pour out again.” Finally he confessed that the report had not made him angry in the least; it had, in fact, sent him to the book (he was not a great reader of fiction). But having read this particular work, he could only say he would have been proud to acknowledge it as his own.

Some time later, when I was dining with him at his house in Knightsbridge, our talk reverted to the subject which had been the means of making us personally acquainted, and he showed me a note-book in which he had scribbled the following: “‘Queen of Connaught’—good for a play.” I told him that Mr. Buchanan had had the same idea; that, as a matter of fact, he had sketched the play, and had begun the writing of it, but that so far he had been unable to see in it the makings of a theatrical success. At this Mr. Reade became keenly interested, and was so good as to say that in the event of Mr. Buchanan going on with the work he would be only too pleased to help him with his criticism and advice. I related all this to Mr. Buchanan, who, spurned to fresh efforts, reviewed his notes and returned to the writing of the play. As the work proceeded we went, on Mr. Reade’s invitation, from time to time to Albert Gate, to read him certain scenes and talk over others, and many delightful evenings were so spent. One evening, I remember, while Mr. Buchanan was reading a scene in the last act, the great novelist became so excited that he could not keep in his seat. He paced the floor ejaculating “ Good!” “Very powerful!” “Go on, my boy!” and on the conclusion of the reading he rang the bell, announcing, in his most delightful manner, that the act was quite good enough to warrant the opening of a bottle of champagne. The play, on its completion, was accepted by Mr. Henry Neville, and was produced by him at the Olympic Theatre (then under his management), Mr. Neville himself appearing as the hero John Darlington, while the late Ada Cavendish sustained the part of the Queen of Connaught. Though the piece drew fair business, and could not by any stretch of the imagination be called a failure, it never rose into what may be called a great theatrical success.

_____

Next: The Nine Days’ Queen (1880)

Back to the Bibliography or the Plays or Harriett Jay Theatre Reviews

|

|