|

Play List: 4. Corinne 7. The Mormons 9. Lucy Brandon 10. Storm-Beaten 11. Lady Clare 13. Bachelors 14. Constance 15. Lottie 16. Agnes 17. Alone in London 18. Sophia 19. Fascination 20. The Blue Bells of Scotland 21. Partners 24. Angelina! 25. The Old Home 26. A Man’s Shadow 27. Theodora 29. Clarissa 30. Miss Tomboy 32. Sweet Nancy 33. The English Rose 36. Marmion 37. The Gifted Lady 38. The Trumpet Call 39. Squire Kate 40. The White Rose 42. The Black Domino 44. The Charlatan 45. Dick Sheridan 47. Lady Gladys 48. The Strange Adventures of Miss Brown 49. The Romance of the Shopwalker 52. Two Little Maids from School ___ |

|

ROBERT WILLIAMS BUCHANAN (1841 - 1901) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

THEATRE REVIEWS 41. The Lights of Home (1892)

The Lights of Home Film: The Lights of Home, directed by Fred Paul, 1920 (more information in the Robert Buchanan Filmography section).

The Referee (24 July, 1892 - p.3) “The Lights of Home” is the title which has been finally selected for the new drama, by George R. Sims and Robert Buchanan, which will be produced at the Adelphi next Saturday evening. There is a sympathetic sound about this title which likes me well—and I fancy it will find favour in the sight of playgoers. I daresay it was suggested to the collaborators by a recent perusal of that popular poem “The Stowaway,” in which the following lines occur:— All was over now, and hopeless! There are five acts in “The Lights of Home.” Of these four take place on the English sea-coast, and the scene of the other is laid in Baltimore, Maryland. The steamship Northern Star will cut rather a prominent figure in the play, and on board this vessel Mr. Kyrle Bellew will occupy exactly the same position that he occupied in real life on board another vessel some years ago. Therefore he may be expected to know his “business.” ___

The Era (30 July, 1892 - p.8) MESSRS GEO. R. SIMS AND ROBERT BUCHANAN’S drama The Lights of Home will be produced at the Adelphi Theatre to-night, with a cast which will include Mr Kyrle Bellew, Mr Lionel Rignold, Mr Charles Dalton, Mr W. A. Elliot, Mr G. W. Cockburn, Mr Howard Russell, Mr Thomas Kingston, and Mr Willie Drew; Miss Evelyn Millard, Mrs Patrick Campbell, Mrs H. Leigh, Miss Ethel Hope, and Miss Clara Jecks. The authors have founded their play upon the pathetic poem “The Stowaway.” The action takes place, for the most part, on the English sea coast; but the scene changes in the last act to Baltimore, Maryland. ___

The Times (1 August, 1892 - p.6) THE THEATRES. ADELPHI. The era of historical drama at the Adelphi has been shorter than some would have desired to see. In The Lights of Home, which, like the recent Cromwellian play, is the work of Messrs. Sims and Buchanan, an undisguised return is made to the kind of play with which these authors are principally associated, and, considering the frantic applause bestowed upon their efforts on Saturday night, and chiefly upon a great mechanical sensation in the shape of a shipwreck, Adelphi melodrama of the familiar type may be said to have taken a new lease of life. To be sure, The Lights of Home is an excellent sample of this class of entertainment. The story of the distressed lovers, which it seems so hard to break away from, is here told anew with considerable freshness of incident and with scenic effects which no one will deny to be startling and, in their way, impressive. Like an ever-popular dish, the story is served sometimes with one sauce, sometimes with another. Messrs. Sims and Buchanan have elected in the present instance to give it a nautical flavouring, choosing as the hero an officer in the merchant service, whence an opportunity for representing one of the most formidable catastrophes with which the stage can deal, to say nothing of a lifeboat rescue and such incidental attractions as views of the sea in calm and storm, of towering cliffs, and flashing lighthouses, together with a picturesque personnel of fisher-folk and coastguardsmen. Although the nautical drama is less seen now than in the days of T. P. Cooke, there is no evidence that it has lost its hold upon the popular imagination. The stage sailor no longer dances a hornpipe or “shivers his timbers,” but he is still good for a song with a stirring chorus, and for unsurpassed feats of gallantry in love and war. As a hero of melodrama accordingly he comes only to conquer. This was the lesson of Harbour Lights, probably the most successful nautical play produced since Black-Eye’d Susan, and, judging by it reception on Saturday evening, The Lights of Home will, in the course of the next few months, tell a similar tale. After all, who shall say that novelty of plot is more indispensable to melodrama than it is to pantomime? Having a favourite set of characters, what more natural than that the public should have their favourite set of sentiments and situations? ___

The Morning Post (1 August, 1892 - p.2) ADELPHI THEATRE. Messrs. G. R. Sims and Robert Buchanan in their late play at the Adelphi dipped into the pages of Sir Walter Scott, and introduced Cavaliers and Roundheads to their patrons. The experiment was fairly successful, but as a rule melodrama in its simple and conventional forms pleases better than the poetic or historical drama. Scenes of everyday life set forth in homely incidents and characters “up to date” are more to the liking of Adelphi audiences. Therefore, in the new play, “The Lights of Home,” the auditor is not surprised to have the catch-word heard at the street corners before entering the theatre. The characters belong to the present time, and some of them echo the most recent jokes and allusions of Modern Babylon. In constructing the drama the authors have had in view such rural scenes as Messrs. Gatti would present with all possible effect, and lovely coast scenery with a storm at sea and other sensational effects bring into prominence all the mechanical resources of the theatre. The story is a simple but sympathetic one, the humour direct and effective, and the pathos and sentiment are such as commend themselves to the audience. The incidents are sufficiently exciting to give the “real old Adelphi thrill,” which hushes pit and gallery for a moment, only to break forth into vehement applause when the breathless suspense of the situation is over. In regard to the title, “The Lights of Home,” dramatists who have once made a great hit are fond of repeating their successes, and in this play there is the echo of “The Lights of London,” which made Mr. Sims famous, also of “The Harbour Lights.” There is no particular reason why the new Adelphi drama should be called “The Lights of Home,” but it answers its purpose, and the “play’s the thing” after all. It opens in a fishing village where Philip Carrington, first mate of the steamer Northern Star, has returned home after a voyage which had been taken owing to unrequited love. During his absence another has taken his place and has paid attentions to the heroine, Sybil, daughter of a wealthy landowner. The rival, Tredgold, is not a worthy suitor, for her has betrayed the daughter of a fisherman, Dave Purvis, but this fact has yet to be revealed, as we may be sure that so innocent and pure-minded a maiden as the heroine would not tolerate such a lover if she knew of his misdeeds. Sybil also has been led to believe that Carrington is dead. She is therefore greatly astonished to meet her old lover in the village. Like young Lochinvar in Sir Walter Scott’s ballad, Philip does not intend to have his sweetheart taken from him by a wealthier man. He appears at a party given at the young lady’s house, Cliff Hall, and without stopping for travelling costume carries the heroine off in her ball dress to the ship. Dave Purvis, the fisherman, in revenge for the betrayal of his daughter, tosses the rival Tredgold over the cliff. The story now pushes along briskly, for in the third act we find Philip and Sybil are married, “and living happily ever after” at Baltimore, U.S.A. But in the midst of their felicity the young husband learns from an English journal that he is suspected of the murder of his rival, Tredgold. Brave and fearless, the hero determines to face the charge, and disprove it. In the fourth act there is a storm at sea, threatening with shipwreck the steamer in which the hero has returned to England. There is all the rush and roar, the fury and excitement which on the Adelphi stage never fails to evoke the enthusiastic plaudits of a well-pleased audience. Nobody inquires particularly why Philip is left alone on the storm-beaten vessel, or why Tress Purvis, the fisherman’s daughter, pulls out to sea in an open boat, like another Grace Darling, to save him. It is enough for all practical purposes that he is saved, and that when the coastguard men take charge of the hero in anticipation of the inquiry about the murder, Dave Purvis, the fisherman, confesses to having thrown the rival lover over the cliff, and promises to appear when Justice requires him. Philip embraces his wife, and, making pleasant references to “The Lights of Home,” the drama ends to the satisfaction of everybody. The acting was excellent all round. Mr. Kyrle Bellew played the young nautical hero, and if he lacks the physical force of Mr. Terriss, he is quite as impassioned and earnest, and made the hero very attractive. Miss Evelyn Millard represented the heroine gracefully, and Mrs. Patrick Campbell had a part that suited her extremely well—that of the fisherman’s daughter. It is a conventional character, but Mrs. Campbell played it with much fervour and intensity. Mrs. H. Leigh was excellent as the fisherman’s wife, and Miss Clara Jecks in the little part of Martha Widgeon employed her genuine humour to good purpose. A drama of this kind must of course have a comic cockney to relieve the sentiment. The authors have in Jim Chowne a “private inquiry agent,” fitted Mr. Lionel Rignold with a part “of the street streety,” and he revels in it, keeping pit and gallery in a perpetual state of hilarity. The private inquiry agent has always got “a lidey in the case,” and he tells us that “when a lidey’s in the case” profit is the certain result. Mr. Lionel Rignold’s delivery of Mr. Sims’s Cockneyisms was quite droll enough to justify the incessant laughter of the audience. Mr. Charles Dalton and Mr. G. W. Cockburn played well, as did Mr. Willie Drew, Mr. Howard Russell, and others. The sentiment of “The Lights of Home,” with its alternately pathetic and humorous dialogue, its effective and exciting scenes and excellent acting, proved so entirely to the taste of the audience that it may be pronounced a most successful drama. Authors, actors, and managers have again shown their competence to cater for an Adelphi audience, and to deserve the enthusiastic applause that was heard when the curtain fell. ___

The Pall Mall Gazette (1 August, 1892 - p.1) “THE LIGHTS OF HOME.” THE NEW MELODRAMA AT THE ADELPHI. IT seems safe to prophesy that Mrs. Patrick Campbell will some day take a very prominent place on the English stage. Since her appearance as Rosalind at the Shaftesbury in 1890, she has made wonderful progress, and her performance on Saturday night was as good as we could wish it to be; with a delightful person, a splendid voice, and a true artistic idea of acting, she seems qualified for highest work, and her acting on Saturday lifted the orthodox melodrama to a surprising level. To be just, we must add that she was greatly aided by the authors. Messrs. Sims and Buchanan have caught her character and that of her father and mother, and presented them with a force and truth that to the critical is injurious to the rest of the play. For the rest, after all, is des restes of their other plays. Indeed, it justified a critical witticism uttered in the stalls, “I always was fond of this play.” This is not surprising. Until the recipe is changed one cannot arrive at much novelty. Given as a theme that the hero is to be suspected and accused of a murder which he did not commit, and has to be made unhappy till the last five minutes of the play, and no author can be expected to produce anything very new. However, the audience does not mind the lack of novelty a bit. In truth, our public likes old plots just as it likes old whisky, old jests, and old politicians—almost anything old, in fact, except old clothes. The tale has a Romeo and Juliet flavour. We have the Montague-Garfields and Capulet-Carringtons living at an English fishing village and hating one another as a mediæval saint hated soap. Why, goodness knows, for the authors may not have invented the cause yet, certainly they have not told it. So Philip Carrington loves Sybil Garfield and consequently roves about the sea, whilst she very imprudently almost marries her cousin, Arthur Tredgold. In the nick of time Philip returns, and Sybil and he get re-engaged, despite the threats of her gloomy brother Edgar. However, Philip does nothing in particular but utter fine sentences and roll his eyes at the gallery, and the cousin pursues his unwelcome suit. Are there many people in real life who desire to make themselves thoroughly miserable by marrying a girl who despises and dislikes them? The conduct of a Scarpia who wants to possess her once is intelligible, but hardly that of a man who wishes to live with her, a fisher girl. Tress Purvis it is who cuts the question. Arthur Tredgold once swore to marry her, and, relying on his oath, she determined to prevent his marriage. Tress tells her wretched tale to Philip, who has been brought up almost as her brother. Like a true hero—in melodrama—he generously resolves to use the knowledge as a means of inducing Sybil to elope; what is to become of Tress of course is none of his business. So Philip and Sybil elope, and as they meet Arthur on the cliffs there is a struggle between them which ends in the hero’s triumph. Arthur determines to go for help, but unexpectedly meets Dave Purvis, the father of Tress. Dave has no one to elope with, so he has resolved to reckon with Arthur, the tale of whose infamous conduct he overheard when Tress told it to Philip. Mr. Tredgold is scornful about the idea of “righting” Tress; perhaps he has read some of the new morality and knows that to marry a girl whom you have dishonoured is to do a double wrong. But Dave has read none of these ideas, so he heaves Arthur Tredgold “over the cliffs by the sea,” as Mortimer Collins would have called it. You can guess the rest of the play; if not it is in thirty-three words: Philip is accused by Edgar of the murder, so he returns to England to stand his trial, and Dave, after conscience tortures, comes forward to say, Thou canst not say he did it. ___

The Standard (1 August, 1892 - p.2) ADELPHI THEATRE. After a brief excursion into the regions of the historical play, with results which do not seem to encourage a repetition of the attempt, the Adelphi has reverted to melodrama of the kind with which it is chiefly associated. Messrs. Sims and Buchanan have been called on to provide the piece, and under the title of The Lights of Home it was given at Messrs. Gatti’s theatre on Saturday evening. It would be futile to complain that the authors have not struck out a new path. They have, however, trodden the familiar way with considerable skill; their materials, if not very novel, are effectively utilised, and the result is a piece eminently calculated to delight the admirers of this style of work; while, moreover, the more critical and less impressionable spectator will pronounce it to be in all respects decidedly well done. Playgoers have reason to be grateful to the authors for avoiding the miseries of the London slums, which were at one time a staple of melodrama. Here the scenes are laid on the rocky coast of South England, and on board a steam-ship, with a brief excursion to Baltimore, though when the picture of the American city is displayed it is found to be taken with the sea and harbour prominent in the background, so that the nautical savour is preserved. The personages who chiefly people these scenes are the Garfields, brother and sister; their cousin, Arthur Tredgold, betrothed to Sybil Garfield; Tress Purvis, a fisherman’s daughter, and a victim to Tredgold’s deceptive wiles—for Tredgold is the villain of the play; and the hero, Philip Carrington, first mate ss. Northern Star. Between the Garfields and Carringtons a species of Montague and Capulet feud has long waged; Sybil is the Juliet, and Philip the Romeo of the story, with Tredgold as an iniquitous Paris. In spite of her brother, Sybil meets her sailor lover one night on the high cliffs outside her house; she yields to his prayer, and consents to elope with him, but Tredgold appears at the moment, and a violent quarrel naturally ensues, in the course of which he is violently thrust aside by Philip. Before he can give an alarm a fresh danger confronts him—old Purvis, Tress’s father, has overheard his daughter’s confession, and comes to have a reckoning with her betrayer. The end of a furious scene is that Tredgold is pushed by Purvis over the cliff, the foot of which, with the villain lying dead, is presently shown by a well-constructed mechanical change. It must be confessed that here the interest is not well sustained in the plot, since it is obvious that Philip can be in no serious danger. He supposes that his thrust has sent his enemy over the cliff, and that he is consequently responsible for his death; but, even so, it was an accident, and no evidence could be forthcoming to convict him of murder. ___

Daily News (1 August, 1892 - p.3) THE THEATRES. “THE LIGHTS OF HOME,” AT THE ADELPHI. Recent experience has taught Messrs. Sims and Buchanan that it is perilous to depart from the old ways of Adelphi drama, and they have profited by the lesson. “The Lights of Home,” brought out with a success that is beyond all possibility of dispute at the reopening of the Adelphi on Saturday evening, is a five-act play which pays a prudent respect to the traditions of the Adelphi stage, even to the extent of involving its hero in a cunningly woven web of circumstantial evidence tending to convict him, though innocent, of the crime of murder. This feature alone might suffice to defend the authors if any descendant of Terence’s “old poet” should accuse them of taking liberties with established models; but their reawakened conservatism extends a great deal further. We have here, for example, a secondary heroine carrying on an intrigue with the gentlemanly scoundrel of the play; and this position of affairs ends once more in a murder or rather manslaughter which, while it removes a pertinacious and designing rival in love, brings upon the hero the strongest suspicion of guilt. So far there is certainly little novelty; but then novelty is not what the patrons of romantic drama demand, it is rather what they are given to resent. ___

Glasgow Herald (1 August, 1892) The experiment of producing historical drama at the Adelphi not having proved the success which was anticipated, Messrs Sims and Buchanan, in their new piece entitled “The Lights of Home,” produced for the opening of the summer season last night, have reverted to the good old strongly-flavoured and conventional style of melodrama which Adelphi audiences have always appreciated. The characters in “The Lights of Home” are all more or less familiar; but for this the habitués of the Adelphi care nothing. The hero, Philip Carrington, a young man of good birth, has, like many other youths of his rank, run through his money, and is obliged temporarily to enter the merchant service as a sailor. He returns from a voyage only to find that his sweetheart, Sybil Garfield, believing him after so long an absence to have forgotten her, has yielded to the entreaties of her brother, and has become affianced to Arthur Tredgold. The return of the young sailor, however, revives Sybil’s old love for him, and she eventually consents to a nautical elopement. Philip is the more desirous to take her away as he learns from his foster sister, a fisher girl, Tress Purvis, that Tredgold has, under promise of marriage, seduced her. Tress’s confession is overheard by her father, who resolves to avenge himself upon the seducer. This leads to one of the most powerful scenes in the piece. On the lawn before the house Sybil meets her young sailor boy, and (the lady being in full ball costume) they escape in a boat, which is seen being rowed out to a vessel in the distance, while Tress’s father confronts the villain, who, after a desperate struggle, is hurled against the wooden paling which protects the lawn from the steep cliff, and is thrown headlong downwards. Here he is discovered dead by the girl he has injured. It need hardly be said that after the manner of Adelphi melodrama, the hero is wrongly accused of the murder. He is, indeed, followed to Baltimore, where he lives married to Sybil, but, conscious of his innocence, he readily consents to return to England, and face his accusers. This leads to another sensational scene, for on the voyage, the hero is shipwrecked, and is left on board apparently to die. From this unpleasant situation he is, however, rescued by none other than Tress Purvis, who, like another Grace Darling, rows out from the shore and affords him the means of escape, his innocence being afterwards established by the confession of the real murderer. Mr Kyrle Bellew is hardly strong enough for the rôle of the hero, but Miss E. Millard is excellent as the heroine, and a still greater success was gained by Mrs Patrick Campbell, who gave a very powerful delineation of the character of the abandoned fisher girl Tress Purvis. Among the comic characters is Mr Lionel Rignold, as a rascally inquiry agent with a lame leg, while Miss Clara Jecks was vivacious enough in the rôle of a widow. ___

The Daily Telegraph (1 August, 1892 - p.2) ADELPHI THEATRE. Clever and experienced dramatic doctors, indeed, are the well-known partners, George R. Sims and Robert Buchanan. The Brothers Gatti, who can testify so strongly to their patience and ability, showed their wisdom in once more calling in such eminent practitioners to diagnose the case of the Adelphi patient. Hitherto so robust and healthy, with a constitution of iron, accustomed to go out in every kind of weather by sea or land, it was suddenly discovered that there was a screw loose somewhere with our old friend. The regimen of history romanticised did not altogether agree with him. He turned against his food. He could not digest Oliver Cromwell or the Puritans either. Royalists and the Civil Wars were not for him. He pined for the rose-covered cottage of domestic melodrama, the tears of the heroine in white muslin, the ragged shirt of the shipwrecked hero, and the glimpses of the dear old Adelphi moon. The doctors shook their heads, but were scarcely a minute in doubt. They threw physic to the dogs. It was as clear as possible that the old and hardened Adelphi knew its own constitution far better than its advisers. So the safest course in the world was adopted. They tried back. There was only one safe card to play—the trump card, in fact—and it took the trick on Saturday night, when honours were fairly divided all round. The authors did well; the managers did even better, for, truth to tell, a more beautifully-mounted play has never been seen at London’s most popular theatre even under its present distinguished and artistic management; and, saving a little weariness and depression from over-fatigue and anxious rehearsals, the acting was fairly up to the mark. Analyse the dominant chords of human emotion either from knowledge of the world, a study of history, or familiarity with the drama, and you will find none stronger or more poignant in effect than the heart-broken daughter hiding her shame from the parents who idolise her, and creeping like a shadow among the familiar objects of a ruined home. It appeals to all, to rich as well as poor. It calls forth every accent of pity and Christian charity. The greatest masters of fiction have used it. We need only cite one instance—the one that we all know by heart. “My mother dear, my native fields I never more shall see; More demoniacal billows were never seen on any stage, modern or ancient. The lights are turned down to Cimmerian gloom, and then the audience is dimly conscious of a huge black sea-serpent tossing on what are supposed to be the waves of Erebus. By fitful flashes of the very best lightning ever manufactured we see a captain on the bridge and hear him attempting to give orders in the midst of the most fiendish babel ever uttered in the infernal regions. Apparently the captain is struck down with the new magnesium lightning, which blinds the audience as much as the crew. Anyhow Mr. Kyrle Bellew takes command, and heroically elects to remain on “the demon ship” when the boats have gone off with every one. The ship breaks up, and it is then that the “[?] mariner,” deserted by his “sooty crew,” is left in charge of the phantom-haunted waves. All the buried bodies of departed mariners appear to be rising up in judgment. Some of the waves are urged on their wild career by giants, others tumble about as dwarfs. The waves are of all sorts and sizes, ranging from six feet high to one. The inky billows are apparently endowed with sub-aqueous life. We expect to see them run away, or possibly talk. They are suspiciously confidential to Mr. Kyrle Bellew and Mrs. Patrick Campbell. “A dozen pair of grimy cheeks were crumpled on the nonce, Certain it is that, though they discreetly forbore to swear, the “demons of the pit” enjoyed the comic shipwreck passing well. Nothing like it was ever seen on the earth above or the waters under the earth. It must be confessed with shame that the ocean is the one thing that has baffled the efforts of the realistic scene-painter. Each sea is more comical than the last, and we can never resist the conclusion that the furious billows conceal an army of acrobatic stage supers or carpenters. We fear the Adelphi audience thought the same. They are not to be hoodwinked by any demon ship! ___

The Referee (1 August, 1892 - p.3) ADELPHI—SATURDAY NIGHT.

When two dramatists, masters of their craft, like Messrs. George R. Sims and Robert Buchanan, put their heads together, expectation runs high. But the production of “The Lights of Home” has excited more than usual interest, for it was generally recognised that romantic drama had reached another turning point with “The White Rose,” and everybody was curious to see what Messrs. Sims and Buchanan would do next. With writers so thoroughly in touch with modern life, there is no going back. “The Lights of Home” is a move in the right direction. It is a fine, rousing drama, modern in form, though the sentiment be as old as human nature, which does not change. They have written a story that goes to the heart of an audience which is not ashamed of its emotions, and they have written it in a direct, straightforward manner in which there is more quality than there is in a good deal of pretentious stuff that calls itself literature. There are passages of the highest order in “The Lights of Home,” and it would be difficult to excel in pathos, in delicacy, or in truth the scene in which Tress Purvis reveals her shame to Philip Carrington, bidding him turn his head away the while she speaks. She is a fisherman’s daughter, who has been seduced by Arthur Tredgold, who had promised to make her his wife. But he has other plans for his future, and seeks to discharge his obligations to her by a present of money sent through the hands of his agent. But Tredgold has reckoned without the hapless girl’s father, or the former lover of Sybil Garfield, to whom he has transferred his vagrant affections. Philip Carrington went for a sailor when he found his suit rejected by Sybil’s family, though not by the young lady herself, and when he comes back first mate of the s.s. Northern Star he learns that Sybil is on the point of marrying her cousin Tredgold, whom she has accepted upon the representation that her old lover was dead. The old relations between Philip and Sybil are revived, and with them the old animosity on the part of her family, and from this starting-point the authors have developed their story without any strain whatever, for the structure of the piece is admirable, scene following scene in a natural, easy sequence. If we have a fault to find, it is to suggest that the conversations which open the scenes should be reduced, even at the sacrifice of some pleasing touches of comedy. But we fear this could only be done, owing to the exigencies of the scenery, by accepting the less agreeable alternative of protracting the intervals between the acts. ___

The Leeds Mercury (1 August, 1892 - pp.4-5) While the last performance of the season was going on at the Lyceum, a crowded audience at the Adelphi was finding pleasurable excitement in a dramatic event of quite an opposite kind—none other than the first production of a new melodrama by Messrs. G. R. Sims and Robert Buchanan. In their last collaboration these two excellent dramatists produced something out of the ordinary line, testing the taste of Adelphi patrons with a little of Old World romance and picturesque historical colouring; but on this occasion they have reverted to original methods, and “The Lights of Home” is as strong a piece of melodrama as Mr. Sims has ever put his hand to, as the Adelphi—famed for the wonders which it has displayed in the way of lurid and exciting stage effects—has ever delighted a Bank Holiday audience with. Necessarily the new play works on familiar lines, and it is perfectly well known that the sailor hero, who involves himself in a coil of conventional trouble at the outset, will by the last act have scattered his enemies and made his future peace secure. But the story is evolved in dramatic fashion, and as there is a realistic shipwreck, a realistic murder, and several other things realistic, it is unnecessary to say that the Adelphi audience exhibited signs of high pleasure and approval, and that “The Lights of Home” seems marked out for a successful run both in London and the provinces. The new melodrama is full of action, the base and the heroic being blended to the approved strength; and some of the stage effects are exceedingly striking and novel. ___

The Morning Post (2 August, 1892) BANK HOLIDAY AMUSEMENTS. ADELPHI THEATRE. At the Adelphi Theatre the good old school of melodrama flourishes in Messrs. G. R. Sims and Robert Buchanan’s genial play, “The Lights of Home,” which was produced last Saturday night with every promise of lasting success. Last night the Adelphi piece attracted a host of playgoers to applaud the brilliant effects and to follow the fortunes of the sympathetic hero and heroine, so well played by Mr. Kyrle Bellew and Miss Evelyn Millard, while the Cockney drollery of Mr. Lionel Rignold, the earnestness of Mr. Dalton, Mr. Cockburn, and Mr. Howard Russell, the pathos of Mrs. Patrick Campbell, and the cheerful humour of Miss Clara Jecks and Mrs. H. Leigh gained the fullest appreciation of a crowded house. Messrs. Sims and Buchanan have produced a play that will prove very attractive, and Messrs. Gatti have placed it upon the stage with even more than ordinary brilliancy. All the best traditions of a real Adelphi drama are embodied in “The Lights of Home.” ___

The Graphic (6 August, 1892) “The Lights of Home,” at the Adelphi BY W. MOY THOMAS A NAUTICAL drama is a widely different thing in these times from what it was in the glorious days of Mr. T. P. Cooke. That renowned impersonator of the British sailor had served his King and country afloat in the early years of the present century, when the songs of Dibdin, with their numberless references to “winds that blow” and “wooden walls,” went home to the national heart. Accordingly, in the T. P. Cookeian drama the hero was almost always a man-o’-war’s man of the grog-drinking, tobacco-chewing, wide-trousered, hornpipe-dancing type; and its principal scenes were certain to take place aboard a British man-of-war. What the nautical drama has now become may be seen in the new romantic play, in five acts, by Messrs. G. R. Sims and Robert Buchanan with which the management of the Adelphi have just commenced an unusually early, yet very promising, autumn season. Originality in the elements of the story the authors have not sought for, as will be seen in the fact that the whole plot turns upon a charge of murder brought against the noble, high-spirited Philip Carrington, first mate of the steamship Northern Star, who, though he is unlucky enough to be the victim of circumstantial evidence apparently pointing to his guilt, is, it need hardly be said, wholly innocent of the charge of slaying his rival in love, the detestable Arthur Tredgold. The untoward business is in this wise. Philip doats upon Miss Sybil Garfield, of the Cliff Hall, and Miss Sybil Garfield much prefers him to the sinister suitor whom her saturnine brother Edgar, prompted by personal feelings and the family feud between the Carringtons and the Garfields, insists upon her marrying. When one day the long-absent Philip comes ashore from his ship in the bay and discovers that Sybil loves him still, he persuades her to slip away one summer evening from a dinner-party at the Hall and trust her destiny to him. But as the lovers are hastening along the cliff they are met by the detestable Tredgold, and there is a struggle in which the latter is sent staggering into the arms of Dave Purvis, a fisherman who has come to demand at the hands of this scoundrel reparation for his cruel betrayal and desertion of the fisherman’s beloved daughter, Tress Purvis. Hence a second struggle, in the course of which Tredgold is hurled over the cliff. Of this tragic sequel, however, the lovers, who have now descended to the shore and embarked in a skiff for the steamship Northern Star, know nothing; till, while spending their honeymoon blissfully in a charming cottage and garden near Baltimore, U.S.A., their dream is disturbed, first, by a paragraph in an English paper, announcing that Philip Carrington is wanted on a charge of murder, and next by the arrival of the stern, avenging brother. That the manly Philip at once determines to return and meet the charge, and is finally cleared by the old fisherman’s confession, who that has any experience of the ways of Adelphi drama will need to be told. ___

The Era (6 August, 1892) THE LONDON THEATRES. ADELPHI. Philip Carrington ... Mr KYRLE BELLEW From a practical playwright’s point of view, Messrs Geo. R. Sims and Robert Buchanan’s drama The Lights of Home, which was produced at the Adelphi Theatre on Saturday last with every symptom of success, is not as workmanlike and ingenious as some of Mr Sims’s previous achievements. As the murder of which the hero is accused has really been committed by a good and conscientious man in a moment of intense aggravation, it is obvious that the innocent will not be allowed to suffer for the guilty. On the other hand, there are freshness and novelty in the treatment, we have fewer of the well-worn melodramatic types, and the story is told in a series of interesting tableaux, each of which gives excuse for a very effective “set.” Authors, actors, and scenic artists equally share in the success which we confidently expect for The Lights of Home. ___

Black and White (6 August, 1892) In the new Adelphi piece, The Lights of Home, Mr. Buchanan and Mr. Sims have done again what they have often done before, and gauged to a nicety the taste for melodrama of an Adelphi audience. There is a place in the world of dramatic creation for good melodrama, and Mr. Buchanan and Mr. Sims between them can turn out very good melodrama of the kind the Strand haunter loves to see. Given certain conditions, given the inevitable hero accused of the inevitable murder, and the inevitable girl who has been seduced by the inevitable villain, The Lights of Home is as good a play as heart of melodrama-loving man could desire. If the would-be visitor to an Adelphi melodrama were to jot down beforehand what he expected to find in his evening’s entertainment, it is probable that in nine cases out of ten he would predict pretty accurately what he was going to see. A wrongly accused hero is an essential, so is an injured young woman, so is comic relief. The heroes are always the same, the heroines are the same, the injured young women are the same, the comic relief is the same. Mr. Buchanan and Mr. Sims do the work probably as well as it can be done. But it would be interesting to know what the author of “London Idylls,” what the translator of the “Contes Drolatiques” really think of performances which give to the Adelphi audiences so much honest and so much wholesome pleasure. ___

The Sheffield and Rotherham Independent (6 August, 1892 - p.5) . . . “The Lights of Home,” at the Adelphi, has much improved since the first night. It is a good drama of the conventional kind, abounding with human touches that go straight to the heart of pit and gallery, and fitted with gorgeous scenery and realistic stage mechanism, that excite admiration in the old and new sense of the word. Now that wind and waves, and the inconstant moon are under better control, one can better enjoy the excitement of seeing the steamer wrecked within sight of “The Lights of Home,” after crew and passengers have been rescued—all but the hero, who is saved by an up-to-date Grace Darling, in time to vindicate himself from a false charge of murder, confound his foes, and embrace his very handsome wife, to the sound of sweet music as the curtain falls on the fifth act. There will be no “dead season” at the Adelphi, thanks to Mr. Robert Buchanan, the Poet, and Mr. George R. Sims, the verse-maker. ___

The Shields Daily Gazette and Shipping Telegraph (8 August, 1892 - p.4) The sensational scene of the new drama by Messrs G. R. Sims and Robert Buchanan, produced at the Adelphi Theatre on Saturday night, is the biggest thing in shipwrecks ever produced on the stage. A steamship under full sail goes to pieces, and the rescue of passengers by the lifeboat is presented in all its details. ___

The Theatre (1 September, 1892) “THE LIGHTS OF HOME.” A drama, in five acts, by ROBERT BUCHANAN and GEORGE R. SIMS. |

|

|

|

From one point of view, a remarkable drama; a very remarkable achievement! Neither to Mr. Sims nor to Mr. Buchanan is it given to present a personal resemblance to the late Mr. Benjamin Disraeli, but their joint career in melodramatics surely has been foreshadowed by his in politics. In the startling appearance of the young Commoner of 1837 there is nothing to suggest Mr. “Dagonet” and his brother “Bard”—if photography lie not. The bottle-green frock coat, the Dick Swiveller waistcoat, the network of glittering chains, the large-fancy-pattern pantaloons, the black “muffler” tie—“above which no shirt collar was visible”—these impressive details of thef amous picture find no counterpart in the portraits of the twin dramatists to-day. Nor can either of them boast of “a countenance lividly pale, set out by a pair of intensely black eyes, and a broad forehead overhung by clustering ringlets of coal-black hair, combed away from the right temple and falling in bunches of well-oiled ringlets over his left cheek.” In Disraeli’s reception by the Commons—his New Critics—and in the dramatists’ by theirs—the Intellectual Intolerants—is distinguishable, however, the same note of baffling derision, and one may readily conceive their echoing the prediction of the dandy-politician:— “The time will come when you will hear me.” Now that time has come. From the least sympathetic of quarters their drama has wrung a grudging and halting praise, and for this reason does it claim recognition as a remarkable piece of work. In outline it is a lusty, shapely member of what Mr. Pinero has called “the family of Falsely Accused,” but several striking features betray its near relationship with some of Dickens’ beautiful creations. This fact it is, perhaps, which accounts for the rout of the Intolerants. One touch of nature makes the whole world kin—and reconciles even the Old Critics and the New. And a touch of nature undoubtedly there is in the new version of Steerforth’s seduction of Little Em’ly, and Dan Peggotty’s shame and vengeance. The betrayal of Tress Purvis by Arthur Tredgold and his accidental death at her father’s hands, form the secondary plot. They are the broom, so to speak, which clears the way for Carrington’s elopement with Sybil, and the inevitable accusation of murder, without which no hero’s honeymoon can be complete. In the eyes of the audience, however, this Little Em’ly episode is the drama, and but for the general opinion that the nominal heroes and heroines must now-a-days be of gentle birth, the whole play might well have dealt with it and it alone. The characters of Tress and Dave are drawn with a firm yet tender hand, and the confession of her fall to her old playmate, Carrington—with the ensuing scene of her father’s horror, grief, and forgiveness—is in language and in treatment worthy of comparison with the famous scene in “Olivia.” Mrs. Patrick Campbell and Mr. W. A. Elliott create a fine effect in these parts. Mrs. Campbell’s nervous frame vibrates with emotion. Her artistic instinct serves her truly. In her picture of Tress she is never at fault. Of singular pathos, of unutterable mournfulness, exquisite in womanly feeling is her playing in the great scene; and for Mr. Elliott’s strong, sturdy, earnest work almost equal praise is due. Only a great actor could do more with Dave than he does, and Dave, it may be said, is a part not unworthy of a Willard or a Tree. Mr. Bellew lavishes upon the Adelphines refinements and natural touches to which they have been unaccustomed since Mr. Alexander left the house. His share is an admirable contribution of art, and in partnership with Miss Millard—the prettiest heroine we have, and one, moreover, with a throbbing heart in her bosom—he so dignified the episode of Carrington’s return from a supposed watery grave, that a note of genuine pathos was clearly struck. Quaint Mrs. Leigh, sprightly Miss Jecks, and the inimitable Mr. Rignold raise mountains of laughter from molehills of humour, and Mr. Bruce Smith and Mr. Emden must be credited with some of the success, their exceptionally beautiful pictures of coast scenery, and a marvellously realistic wreck scene, furnishing an excuse for any Intellectual Intolerant to pay a second and a third visit to a moving play that is by far the most interesting melodrama since “The Silver King.” ___

The Wrexham Advertiser (15 October, 1892 - p.2) OUR LADIES’ COLUMN. . . . A sensational melodrama at the Adelphi Theatre is always a pleasure to me; and many a year, just at this time, before the other theatres open with their new pieces for the winter, and London is dull and empty, have I spent a charming evening in this well-ventilated and hygenically-appointed little playhouse, and have often discovered unexpected friends by my side doing the same thing, with whom I have rejoiced that we were still sufficiently unspoiled and unconventional to be able thoroughly to enjoy such a stirring drama, as one is always sure of at the Adelphi. “The Lights of Home,” written by George Sims and Robert Buchanan, is by the very names of its authors guaranteed to be something good, and the acting is worthy of the piece, which is delightful to see on the familiar stage. Nautical in its setting it is of course, for I think there is for the multitude, more romance attached to a sailor’s life than to any other, and I am not ashamed to confess that my sympathies go with the brave, true and handsome fellow who unflinchingly meets the miseries and perils of the ocean, and the dangers of unknown and foreign shores, especially if, in spite of all, I am assured that “his heart is true to Poll.” There are some capital characters in this play, well conceived and well acted, and the scenery tells its own tale. The fishing village with the good “Lobster Smack” Inn, the rendezvous for all the good salts, and the bad ones too for the matter of that, in its neighbourhood; but I am bound to say the bad ones are not salts at all, but miserable landlubbers. The landlady of this village inn, Mrs. Widgeon, is delightful as personated by Miss Clara Jecks. Her piquancy, her jollity, and her cleverness, are exactly what a typical landlady in her special way of life should possess. She is a match for everybody, but always kind-hearted and good, excepting to the loathsome “Private Enquiry Agent” who comes poking about the village for his own ends, which are happily defeated. Mr. Eardley Turner makes himself thoroughly and properly unpleasant whilst limping about where he is not wanted, in this disguise, and of course he excites the ire of the upright and downright landlady. Then the hero of the piece, Philip Carrington, first mate of the “Northern Star,” and Petherick, the Captain of that ill-fated vessel; Dave Purvis, a fisherman, and his wife, are acted to the life, and I am not ashamed to say that when sorrow and trouble come upon this good couple through their cherished and dearly loved only child, “Tess,” and a suspicion of having killed her betrayer rests upon the dear old fisherman, I was fairly overcome, and knew not whether to cry, or, laugh at myself for being inclined to do so. But I must not forestall the pleasure I promise all my readers who go to see the play for themselves by telling them the tale. I am sure, too, that they will remark as I did; the enthusiasm with which every good and noble sentiment spoken on the stage is received by the gallery and pit—one would think to hear the applause that every man in the audience was an exemplary husband and father, and every woman a devoted wife, so vociferously do they all receive every evidence of unselfishness and excellence in the characters before them. ___

The Era (11 February, 1893 - p.9) THE MARYLEBONE. Tress Purvis ... Mrs HENRY GASCOIGNE Mr Henry Gascoigne, who is now in the last four weeks of his stay at the Marylebone Theatre, is determined, like Bacon, not to “go out in snuff.” On Saturday last and this week excellent performances of Messrs G. R. Sims and R. Buchanan’s drama The Lights of Home have been given by a company strongly reinforced with new comers of ability. Though Mr Gascoigne’s name did not appear in the cast, the patrons of the Marylebone were not balked in their expectation of seeing and applauding their favourite, Mrs Gascoigne. She appeared as Tress Purvis, and gave a rendering of the part which had the true ring in every speech and in every gesture. Very fine in its intensity was much of Mrs Gascoigne’s acting as the betrayed girl, and her occasional vehemence was in effective contrast with the note of tenderness which was most often struck by this able and experienced actress. A fine manly performance was Mr Joseph E. Pearce’s Philip Carrington. It was full of vigour, and had a chivalrous flavour which was quite appropriate to the character. Mr Ernest Montefiore gave a sharply drawn representation of Edgar Garfield, and Mr Ernest E. Norris was very cool and caustic as Arthur Tredgold. Mr Edgar Leyton did useful work as Jack Stebbing. A strong and dignified impersonation of the old fisherman, Dave Purvis, was given by Mr William James, whose acting in the more serious passages was grandly elevated, and who looked the old salt excellently well. Mr Fred. Selby created roars of laughter by his droll reading of the rôle of Jim Chawne; and, encouraged by his audience with roars of merriment, judiciously developed the comic business at the tea-table in the fisherman’s cottage in the second act. Miss Mabel Pate was graceful and tenderly affectionate as Sybil Garfield; and Miss Margaret Thorne was quaintly domestic as Mrs Purvis. Miss Eugenie Forbes made a smart and spirited landlady, and Miss Fanny Watson was efficient as Mrs Petherick. The minor parts were all capably enacted, and, indeed, we have seldom seen a better all-round performance even under Mr Gascoigne’s management. Mr Barry Parker must be warmly praised for his scenery. It is remarkable what an excellent effect he has contrived to produce. The scenes representing the top and bottom of the cliff in the second act, and the wreck of the steamship in the fourth, are, indeed, calculated to test the resources of a minor theatre to the utmost. But, assisted by Mr Gascoigne’s liberal enterprise, and stimulated by the manager’s energetic desire to mount the piece effectively, Mr Parker has done wonders, and has produced results that are worthy of warm praise. Mr Storer, who has been absent on a brief holiday, has returned to see to the front of the house during the remainder of Mr Gascoigne’s stay at the Marylebone Theatre, which he and his popular and clever wife will leave with the best wishes and the bitterest regrets of all their patrons and friends in Church-street and its vicinity. A Kiss in the Dark, with Mr Fred. Selby as Pettibone, is the lever de rideau. ___

The Stage (23 February, 1893 - p.6) PLYMOUTH—ROYAL (Lessee, Mr. C. F. Williams; Acting Manager, Mr. Harry E. Blakeley).—On Monday there was another large audience for the first provincial production of The Lights of Home, by Mr. Auguste Van Biene’s Co. Barring a few hitches here and there, the piece went splendidly, and any amount of applause was given for this latest Adelphi drama of G. R. Sims and Robert Buchanan. The striking scenic effects were almost as well realised as in London, and Mr. E. B. Norman, stage manager of the Adelphi, who came down to direct the performance, is to be highly commended on its success. Mr. Conway Wingfield makes a very good Philip Carrington, and Sybil Garfield is very prettily portrayed by Miss Essex Dane. Garfield and Arthur Tredgold fall to Mr. C. Tufnell Douglas and Mr. Leslie Murray, who are quite satisfactory. Miss Mary Raby once more wins the sympathy of Plymouth audiences for her pathetic acting as Tress Purvis. Mr. Harry Yardley gave a fine character study of the old fisherman Dave Purvis. Others deserving of notice include Messrs. George Miller as Jim Chowne (a really good part, well played), C. T. Douglas, F. D. Wood, Master Alexander, R. Roberts, W. Jordon, A. Alexander, A. Henderson, and Misses J. Blake (Mrs. Purvis), E. Victor, G. Deroy, A. Keene, and Miss L. Ferris. Miss Lena Burleigh was very funny as the landlady of the Lobster Smack. The Shipwreck Scene was received with tremendous applause. ___

The Hastings and St Leonards Observer (10 March, 1894 - p.6) HASTINGS THEATRE. George R. Sims and Robert Buchanan have enriched dramatic literature with some good plays, but it can scarcely be charged against The Lights of Home that that piece comes within this category. The plot is weak, and the dialogue only commonplace; indeed, it is difficult to realise at times that the work is the outcome of the collaboration of two such highly reputed playwrights as Messrs. Sims and Buchanan. It is a sensational drama, one of that class that usually send the “gods” frantic with delight, and inspire them with the desire to kill the villain, fall down on their knees and worship the hero, and marry the more-sinned-against-than-sinning heroine. We will not say, however, that the humbler patrons of the drama at the first performance of The Lights of Home, at the Hastings Theatre on Monday night, were moved to commit any such extravagances. Allowance must be made for the indifferent material which the artistes have to work upon, but, even considering that extenuating circumstance, there is room for a lot of improvement. There was a lack of realism in the representation, taking it all round; we were watching a performance, not “living in the piece,” rejoicing in the joys of the characters, or sorrowing with them in their troubles. Mr. Lynton’s Company did not evince that grip of the piece essential to the artistic success of the performance, viewing it as a whole, and there were individual defects which jarred on the nerves. It is not worth while to relate the plot in detail; there are many of the concomitants of melodrama, but they are woven together so ineffectively. The wronged lass, the aristocratic cigarette-smoking villains, the suspected hero, the good heroine who narrowly escapes getting married to one of the villains, a murder, a shipwreck—such a shipwreck, too!—a “swim for life”—all these were there, but there was a lack of finish both in the play itself and the acting. Philip Carrington was ably represented by Mr. Alex Calvert, who worked hard for the salvation of the production, and Mr. James B. La Fane’s low comedy business, as Jim Chowne, a private inquiry agent, at times convulsed the house. Messrs. Adam Alexander, Clinton Baddeley, and F. Denman-Wood were responsible for some creditable acting, and Miss Mary Brammer and Miss Ada Binning gave praiseworthy performances. In regard to the majority of the other artistes it is charitable to preserve silence. The scenery is excellent. ___

The Stage (23 August, 1894 - p.5) MERTHYR TYDFIL—ROYAL AND OPERA HOUSE (Lessee, Mr. Will Smithson).—This week we have Mr. Robert Lynton and Co. in The Lights of Home, which has been well received by large audiences. The piece is well mounted, and the scenery is most attractive. As Philip Carrington Mr. J. Malcolm Dunn deserves praise, and he is nightly the recipient of loud applause. Mr. Sydney Leyton as Edgar Garfield is capital. Mr. Sydney Halling is the Arthur Tredgold, Mr. Ivan Barlin is a commendable Dave Purvis, and Mr. Cecil Croft does well as Jim Chowne. Miss Mary Brammer plays Sybil Garfield with care and discretion, Miss Kate Perfrement is quite at home as Mrs. Purvis, and Miss Violet Rawlings does well as Mrs. Pretherick. Miss Louisa Biddulph impersonates Trees Purvis in a sympathetic and womanly manner, and Miss Cissy French makes a vivacious Martha Widgeon. The other parts are well represented. ___

Aberdeen Evening Express (20 November, 1894 - p.4) HER MAJESTY’S THEATRE. “THE LIGHTS OF HOME.” Those who are in a humour to enjoy a stirring bit of melodrama should pay a visit to Her Majesty’s Theatre this week. “The Lights of Home” is a powerfully written five-act play by Mr G. R. Sims and Mr Robert Buchanan, two playwrights who know well how to put on the stage to the best advantage a story of thrilling adventure dished with a good mixture of human interest. The piece was produced in Aberdeen about a year ago, and, judging by the excellent house of last night, it appears to have left a favourable impression. It is in the hands of a good all-round company on this occasion. Mr Malcom-Dunn makes a very successful Philip Carrington, and he is ably supported by Miss Maud Brammer, who plays Sybil Garfield with grace and good taste. Mr Leyton and Mr Loraine would be much more effective is they cultivated a somewhat quieter style of utterance, and could convince themselves that in order to be emphatic it is not at all necessary to give a display of lung power. Otherwise their acting is commendable enough. A very good character is that of Dave Purvis, and in the later scenes especially, Mr Ivan Berlin gives it an excellent rendering. Tress Purvis, too, is a most likable character, and gets every justice at the hands of Miss Louise Biddulph. The private agent, as depicted by Mr Cecil Croft, is a good enough variety performance, and the rest of the company can be fairly described as fit for the parts assigned to them. The play is excellently staged, the mechanical effects of the second scene of the fourth act being specially successful. |

|

|

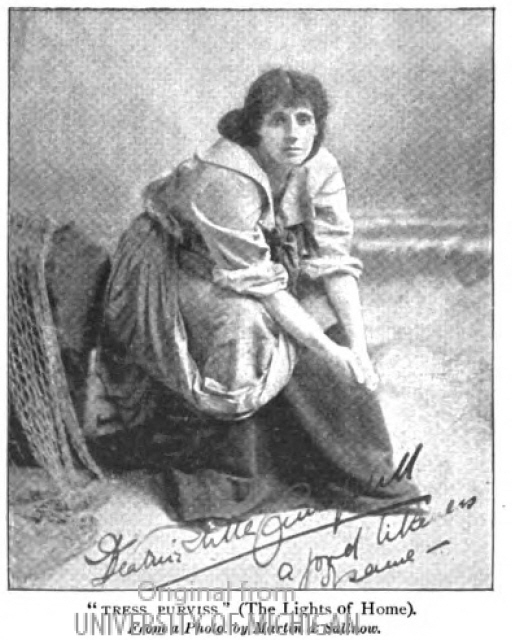

[Mrs. Patrick Campbell as Tress Purvis in the Adelphi production of The Lights of Home

The Era (13 August, 1910 - p.11) KENNINGTON THEATRE. That highly exciting drama, by Mr. G. R, Sims and Mr. R. Buchanan, The Lights of Home, has been presented at the Kennington Theatre during the present week, and throughout the five acts and nine scenes has enthralled the attention of the large audiences which have assembled nightly. The Kennington repertoire company have acquitted themselves during this production with credit, and the staging has been well done, the burning of the Northern Star being a particularly fine scene, while Maryland was a brightly painted set. Mr. Walter Gay was very good as Philip Carrington, falsely accused of the murder of Arthur Tredgold, making an ideal sailor lover of Sybil Garfield. In the latter rôle Miss Jessie Winter looked as fresh and ingenuous a heroine as ever. Mr. Frank Crimp made an excellent Arthur Tredgold, and was seen at his best in the struggle with Dave Purvis, the fisherman, indignantly demanding reparation for the injury wrought his daughter. In the part of Dave Purvis Mr. George Cockburn was magnificent, enacting it with great dramatic force. Mr. Charles Danvers made a big hit in the low comedy rôle of Jim Chowne, the inquiry agent, and he had admirable support from Miss Nellie Burdette as Mrs. Widgeon, landlady of the Lobster Smack. Between them the pair caused a lot of fun. Miss Burdette always showing genuine humour. Miss Elsie Videau was bright and lively as Jack Stebbing, the amorous sailor boy. Miss Winifred White won further laurels by her clever impersonation of Tress Purvis, and the part of Mrs. Purvis, her mother, was capitally portrayed by Miss Marie Kilpack. Mr. J. W. Yeldham was deserving of praise as Captain Petherick, and the rôle of Mrs. Petherick was filled with great naturalness by Miss Peggy Hogan. Mr. G. P. Polson was well placed as Edgar Garfield, the finally relenting enemy of Philip Carrington, and Messrs. H. Thomas, Leblanc, and Sheridan creditably enacted the parts of fishermen. Mr. Horatio Baker doubled the characters of Sambo in the Maryland scene and of the Clergyman in the last act with considerable success. _____

Next: The Black Domino (1893) Back to the Bibliography or the Plays

|

|

|

|

|

|

|