|

The New York Times (19 January, 1892)

AMUSEMENTS.

_____

MISS CAYVAN AS KATHERINE THORPE.

The question why Mr. Daniel Frohman produced at the Lyceum Theatre a play like “Squire Kate,” an adaptation to the locale of British rustic drama by Robert Buchanan of an Ambigu-Comique idea, was asked many times before the curtain was rung up last night. The people who support the Ambigu-Comique in Paris are not the same kind of folks as those who go to Mr. Frohman’s theatre in New-York. The Ambigu is the home of lurid melodrama. Les etrangleurs flourish on its stage, and when the fun comes the people like it to be simple and broad and plentiful. The Lyceum audiences, on the other hand, are dainty and fastidious.

The question thus raised was answered very satisfactorily, however, in the second act of “Squire Kate.” Here Miss Georgia Cayvan’s acting, in a scene that is a faithful transcript from real life, was surprising in its force, thrilling in its genuine emotional power, and charmed the spectator by its unaffected simplicity. It was a piece of acting as near to reality as a good actor ever gets in the practice of his art. It was convincing, moving, flawless in conception and expression, and it will be remembered.

Miss Cayvan has not suddenly acquired new powers, but, for the first time since she has been the principal actress at the Lyceum Theatre, a chance has been given to her to exhibit her powers. And that is the secret of the production of “Squire Kate”—a production that in every way reflects credit upon Mr. Daniel Frohman’s zeal, liberality, and good taste as a theatre manager, for it is beautiful in a pictorial sense, and all the acting is thoughtful, careful, and harmonious.

The one great scene, in which Miss Cayvan’s acting recalls her worthy effort seven or eight years ago to save from inevitable failure a very bad piece called “Our Rich Cousin,” occurs rather too early in the play, perhaps, to secure a long-continued success for it. There is no other incident nearly so good. That, however, ought to attract to the Lyceum every person who honestly enjoys uncommonly good acting. We fear there are too few such persons nowadays to make success for any play. But their good opinion is worth striving for, and their influence is powerful.

The personages in the scene are two sisters—Tennyson’s “sisters,” of course. The elder has drudged and slaved for years to educate the younger, to fit her for a life of dainty luxury and ease. She loves her fondly. But this elder sister, although she is patient in adversity and thoughtful of the comfort of others, is no mere cipher devoid of hopes and aspirations of her own. She has an intensely passionate nature, and she is deeply in love with a commonplace, good- enough sort of a young man, whom her love has transformed into a hero. Good fortune has come to her. In a day she has become rich, and it seems that her dream of happiness is to be realized. She has every reason to believe that her love is returned. She is fooled to the top of her bent, and placed in a humiliating position. When she learns suddenly that her nice young man has chosen her silly little sister, under the influence of the shock she acts just as such a woman would act in real life. She does not remember copy-book maxims, and quote them. All the force of her passionate nature is exerted in the expression of her natural indignation and grief. Her broken, hysterical invective is exactly in harmony with her mood.

Miss Cayvan’s rendering of this scene could not be surpassed. Her powers are wholly equal to it. She brings tears of sympathy to every eye. Every tone of her voice is in keeping; every gesture is aptly expressive, and she lends to this perfectly simple and natural situation the effect of a great dramatic climax.

This is nature. We too often have had the same situation perverted on the stage. We have had a debilitating excess of mawkish amiability on the other side of the footlights. It would be much better for the world if we could have a little more of uncomplaining self-sacrifice and picturesque benevolence in real life and just a little less of them on the stage.

Miss Cayvan’s acting is strong and expert throughout the play, but she has no other scene that approaches the episode in the moonlit hayfield in naturalness and dramatic force. She had much applause last evening for her ingenious treatment of the inevitable scene of reconciliation between the sisters, in which Squire Kate assumes a cheerful manner to hide the sorrow that is still poignant. This was remarkably well done, but the art of the actress was necessarily plainly in evidence all the time. It is not a happily devised episode; and Mr. Buchanan, to tell the truth, is a very tedious and old- fashioned playwright.

As for the play, founded on “La Fermière,” in which Katherine Thorpe, called “Squire Kate,” is the central personage—well, it is H. T. Craven’s “Meg’s Diversions” again without H. T. Craven’s real humor; with a touch of Douglas Jerrold’s “Rent Day” and a hint or two of “Daddy Hardacre.” Kate is Meg again, and Kate’s sister Hetty is Meg’s well-educated sister, who is loved by the man Meg loves. Jasper Pidgeon is there disguised as Geoffrey Doone, the faithful overseer of Kate’s farm; Master Bullfrog, from “The Rent Day,” brags, makes comic love, and gets drunk and behaves like a donkey in the person of Mr. Nash, the tax collector. The only touch of new humor is in the horse doctor, who is also a general practitioner, and who, when a girl is poisoned, treats her for incipient typhoid fever and partial paralysis of the nerve centres. There is another old friend in evidence, too, who is surely Edie Ochiltree of “The Antiquary,” now a shepherd and a herb doctor, who looks like Walt Whitman, but talks a good deal more like Robert Buchanan.

Hodge and Joan are there, of course, as they are in every play of English rural life; there is the customary quantity of straw, and there is, moreover, a bent, scowling, leering, threatening, snarling, grasping, treacherous old miser, Gaffer Kingsley, who is in sight and in hearing much of the time. This is a fine part for Mr. Le Moyne, who makes it as grimly effective as the art of “make-up” and the skill of an experienced actor can make such a part. In most of Act III. this old miser has the centre of the stage; he poisons a girl, he lies about it, he leers awfully while he is splitting wood with a very sharp axe, he threatens, he cringes and whines. This is all old-fashioned melodrama, and good enough of its kind. Some of Mr. Buchanan’s humor, however, is very depressing.

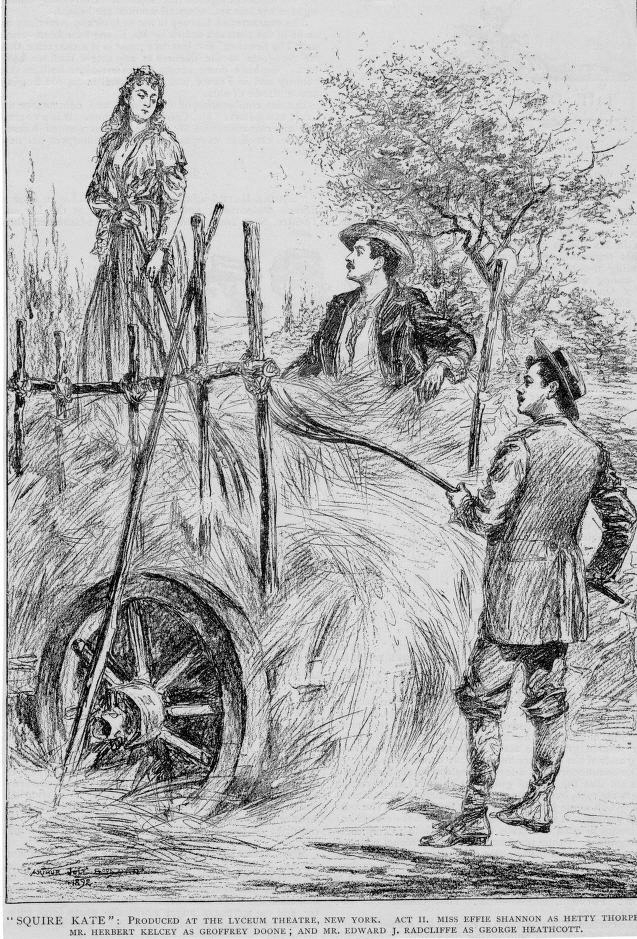

The acting is all good, as we have said. Miss Shannon is pretty and winning, Mrs. Walcot plays the hearty, stupid countrywoman in the good old style, and Mr. Kelcey plays a very thankless part in his accustomed conscientious manner. The scenery is capital, especially the views of the farm kitchen and the hayfield. The full cast of “Squire Kate” is appended:

Katherine Thorpe ....................................Georgia Cayvan

Hetty Thorpe...........................................Effie Shannon

Amanda J. Thistledown............................Mrs. Walcot

Geoffrey Doone.......................................Herbert Kelcey

Gaffer Kingsley........................................William J. Le Moyne

George Heathcott....................................Edward J. Ratcliffe

Jasper Arundel........................................Charles Walcot

Mr. Nash................................................Augustus Cook

Lord Silversnake.....................................Fritz Williams

Jack Dutton.............................................Charles Harbury

Jabez.......................................................Eugene Ormonde

Thomas....................................................John Hamersly

Silas.........................................................Hyde Robson

___

New-York Daily Tribune (19 January, 1892 - p.7)

THE DRAMA---MUSIC.

_____

LYCEUM THEATRE—“SQUIRE KATE.”

In the comedy of “Squire Kate,” by Robert Buchanan, which last night at the Lyceum Theatre had its first presentation in America, an effort has been made to freight with romantic interest and to invest with picturesque theatrical accessories an episode in the experience of two English girls—orphaned sisters, resident on a farm in beautiful Sussex—who loved the same man and whose affectionate intercourse was thereupon temporarily interrupted by anxious misapprehension and jealous rage. This effort has resulted in the fabrication of a play that fits the stage, because it provides opportunities for the actor and for the scenic artist, and because its course is enlivened by incident and crowned by effect. But this effort has been conducted with little or no regard for reason, coherence or the ascertained facts of human nature; and hence the comedy, while it may please at the instant view, appears, in the retrospect, both frail in construction and trivial in substance. It seemed in various ways to please a numerous and refined audience last night, for it was very richly caparisoned, and the lurid and fantastic aspects of its high-pressure love-story, together with its occasional interludes of bovine farce, in which absurdity stands for humor, were interpreted by actors of salient talent and deep sincerity. It will, therefore, enjoy a temporary vogue. A play that is false, however, is for that reason ephemeral.

The great truth of feminine intuition, in all matters of love, has been absolutely ignored throughout this piece; and when you put aside all thought of its adornments, and look with clear vision at the heart of it, you find that it offers for your contemplation nothing more important or more impressive than the spectacle of a young woman afflicted with hysteria because she has found out that the man of her choice is in love with her sister. This fact, in actual life, she would have known without the intervention of any theatrical machinery to apprise her of it; and whatever feeling, in actual life, she might have had, upon this subject, she would most sacredly have kept it to herself. The woman—in her senses—who becomes violent in her conduct and vituperative in her language because her love is not reciprocated may awaken pity, but certainly must forfeit respect. The woman—out of her senses—who suffers and rages because of an amatory disappointment is a subject for a doctor and not a dramatist. The heroine of this play is either one or the other, and, whichever way she is viewed, she is sad to contemplate and painful to remember. “Squire Kate” has been put together upon the principle that you must get your effect, no matter how you get it, and hence it will only please those (and will cease to please even them, when its novelty shall have worn off) who, if entertained at the moment, are completely indifferent alike to dramatic mechanism and dramatic substance. The number of that audience, meantime, is very large.

Mr. Buchanan’s first title for this piece was “The Little Sister,” and that title might wisely have been retained. The name of “Squire Kate” is suggestive of “The Squire,” by Arthur Pinero, of which drama Kate Verity is the principal character. In each case, furthermore, the heroine is a farmer, and in each case she is beloved by the patient, constant, manly, and much-enduring overseer of her farm. At that point, however, all resemblance ceases. Mr. Buchanan, though, like Mr. Pinero, has obviously felt the influence of the great novelist Thomas Hardy—of whom it may be said, if originality, imagination, absolute truthfulness, passionate feeling splendidly curbed, a Shakesperean humor, and a fine style are decisive, is the best author of fiction now writing the English language. It was Thomas Hardy who introduced into literature those strong, peculiar, female characters, full of the qualities of their sex, amid their unique surroundings in the rustic life of England; and when once he opened the path he soon had followers, both conscious and unconscious. Mr. Buchanan, in the making of this play of “Squire Kate,” has built upon the basis of “La Fermiere,” by MM. Armand d’Artois and Henri Paget; but the English soil in which his French roots are planted is unmistakably that of the novels of Thomas Hardy. The old shepherd Jasper Arundel and the sombre and gloomily grotesque scenes at his lonely hut, wherein the desperate Kate Thorpe comes to him for a love-philter and the sordid old ruffian and semi-maniac Gaffer Kingsley comes to him for a poison, are strikingly significant of that original—not necessarily in their plan, but in their attributes of character and in their atmosphere. The suggestions of haunted solitude, weird moonlight, a bleak wind, and the lamentable crying of the birds of night make those scenes exceedingly effective and supply for this comedy a genuine touch of poetic feeling such as would be valuable if anything came of it. And in themselves, apart from their context, they are excellent.

Gaffer Kingsley, the step-father of George Heathcott,—the youth who is loved by Kate Thorpe and by her sister Hetty,—is the strongest character in Mr. Buchanan’s play; but just as Kate Thorpe represents the dementia of thwarted love, so does Gaffer Kingsley represent the dementia of thwarted avarice. He is determined that George shall be married to Kate, and since Hetty stands in the way he will kill Hetty with poison; wherefore he mysteriously seeks the ancient shepherd by night and obtains, under the most suspicious circumstances, the drug most deadly and most fit for his purpose; and so, over this as over almost everything else in the piece there is the glare of extravagance and the disillusion of improbability. Act first, indeed, as a pastoral picture and as a display of the posture of the characters toward each other, is perfect, and it arouses a romantic interest at the same time that it pleases a refined taste. In this act Geoffrey Doone’s devotion to Squire Kate is touchingly indicated; the attitude of yet unspoken loves is made entirely clear, and the Squire, who is about to be evicted by the avaricious curmudgeon, Gaffer Kingsley, inherits a fortune. Act second,— requiring the spectator to believe that an uncommonly clear-sighted woman would accept at second hand and from a discredited source an offer of marriage from her sister’s lover,—moves rapidly to a climax of delirium. Act third shows Gaffer Kingsley’s quest of a poison, his successful administration of it, and his piteous hysteria when menaced with an exposure of his cruel and insane crime. Act fourth reveals the poisoner discomfited, the younger sister saved, and the elder,—momentarily under suspicion of having tried to destroy her rival,—shocked into sanity and delivered from the hateful thraldom of passion and of sin. She has had the common experience of loving and of losing, and those who have looked upon her conduct have seen that she has not borne it well. The value of this spectacle will be differently estimated by different observers. It would be welcome, indeed, if it could only be depended on to teach the young men and women who observe it the power and the beauty of a self-reliant character sustained by a pure spirit.

In a dramatic sense, the most interesting part of the play is the part relative to the unscrupulous and vindictive miser who would do murder rather than lose his object. This character is drawn with vigor and subtlety, and it was impersonated with thrilling force of sardonic will and snarling humor by Mr. Le Moyne. The make-up is particularly fine. The sour, sardonic, chuckling glee could not be improved. The sustainment of the personality is even and potent. There is, however, a tinge of unconscious kindness in the humor that is inappropriate, and the expression of frenzied terror is far less effective than that of frenzied rage. The action while actually giving the poison needs transparency. Concentration must not be carried to the extent of tameness. Mr. Le Moyne was wildly applauded and once was called back upon the scene. Miss Georgia Cayvan succeeded better in the love scenes that are provided for Kate Thorpe than in the delirium. Nothing could be more sweet or more true than her portraiture of the happy country lass; but the moment she struck the false note—which is Kate’s unwomanly conduct at the close of act second—she became artificial and merely vehement. An impassioned and sustained performance of the lover was contributed by Mr. E. J. Ratcliffe, who has the charm of grace, and Mr. Herbert Kelcey carried with fine feeling, delicately expressed, the cumbrous and colorless part of the patient waiter who does not lose at last. The piece should at once be shorn of some of the bumpkin talk and of the vacuous gabble of the tax collector. This is the cast:

Katherine Thorpe ....................................Georgia Cayvan

Hetty Thorpe...........................................Effie Shannon

Amanda Jane Thistledown........................Mrs. Walcot

Geoffrey Doone.......................................Herbert Kelcey

Gaffer Kingsley........................................William J. Le Moyne

George Heathcott....................................Edward J. Ratcliffe

Jasper Arundel........................................Charles Walcot

Mr. Nash................................................Augustus Cook

Lord Silversnake.....................................Fritz Williams

Jack Dutton.............................................Charles Harbury

Jabez.......................................................Eugene Ormonde

___

Pall Mall Gazette (27 January, 1892 - p.7)

“Squire Kate,” a new pastoral drama, specially written by Mr. Robert Buchanan, for the Lyceum Theatre, New York, has (says a cablegram) just been produced with complete success. The scene is laid in the English rural districts at the present day, and the subject is entirely domestic and realistic. The play will shortly be produced in London, where all rights are secured.

___

The Era (30 January, 1892)

THE DRAMA IN AMERICA.

_____

“SQUIRE KATE.”

Pastoral Drama, in Four Acts,

Adapted by Robert Buchanan from the French La Fermiere,

by MM. Armand d’Artois and Henri Pagat,

Produced for the First Time at the Lyceum Theatre, New York,

Jan. 18th, 1892.

Katherine Thorpe ............................. Miss GEORGIA CAYVAN

Hetty Thorpe..................................... Miss EFFIE SHANNON

Amanda Jane Thistledown................. Mrs. CHARLES WALCOT

Geoffrey Doone................................ Mr HERBERT KELCEY

Gaffer Kingsley................................. Mr WILLIAM J. LE MOYNE

George Heathcott............................. Mr EDWARD J. RATCLIFFE

Jasper Arundel................................. Mr CHARLES WALCOT

Mr. Nash......................................... Mr AUGUSTUS COOK

Lord Silversnake.............................. Mr FRITZ WILLIAMS

Jack Dutton..................................... Mr CHARLES HARBURY

Jabez............................................... Mr EUGENE ORMONDE

Thomas........................................... Mr JOHN HAMERSLY

Silas................................................ Mr HYDE ROBSON

(FROM OUR OWN CORRESPONDENT.)

NEW YORK, JAN. 20.—Mr Buchanan’s play made a profound sensation, and commanded a generally favourable verdict. It was very strongly acted in its principal parts by Miss Georgia Cayvan and Mr Le Moyne, and the supporting Lyceum company brought considerable ability to bear upon the performance. In his adaptation Mr Buchanan has changed the scene of the play to a Sussex farm, and made his characters entirely English. Otherwise the story of the original French piece is adhered to as closely as fidelity to English incident and character would permit. The play has been done into vigorous, terse dialogue, the fury of the disappointed heiress is depicted with great naturalness of action and language, and the interest of the poisoning episode in the third act has been worked up with considerable dramatic skill. The final act is somewhat tedious in conventionality, and is the only portion of the play that allowed the attention of the audience to slacken. Daniel Frohman will, however, quicken the interest of this act, and when its faults are removed the Buchanan play will, without doubt, be one of the most remarkable successes of the Lyceum management.

___

Cleveland Plain Dealer (7 February, 1892 - p.14)

The success of “Squire Kate” at the Lyceum theater has resulted in arrangements for its production in London. The author will use the acting version of the Lyceum, with all the changes and improvements made since the first production at that house. As in the case of “The Idler” and “The Maister of Woodbarrow,” first produced at the Lyceum, English managers have awaited the American verdict before producing “Squire Kate.”

___

The Era (20 February, 1892 - p.10)

IT is said that Mr Robert Buchanan has written a new Irish play, in collaboration with the boyish Mr Aubrey Boucicault, who feels that the time has come when he must go a-starring through the States, like his father. “I am convinced that young Boucicault will be one of the best paying stars in the world,” says Mr Arthur Rehan, his acting-manager—as what else should an acting-manager say? The play has the capital title of The Squireen, and it is odd to note that Mr Buchanan’s other new play is called Squire Kate—both names recalling Mr Pinero’s first great success. Squire Kate indeed, as we understand, is like “The Squire” Kate Verity, a lady farmer.

___

The Referee (28 February, 1892 - p.3)

“The English Rose” goes on at Proctor’s (Twenty Third-street) Theatre, New York, next Thursday evening. Aubrey Boucicault has been engaged to play Harry O’Mailley. Robert Buchanan’s “Squire Kate” has reached its fiftieth night at the Lyceum, New York, and will run on there till Easter Monday, when its place will be taken by “The Grey Mare” (Sims and Raleigh). Edwin F. Thorne will presently start an American tour with “The Golden Ladder” (Sims and Wilson Barrett). Our Mr. DAGONET and his collaborators seem to be all over the shop.

___

The Wichita Daily Eagle (2 March, 1892 - p.7)

NYM CRINKLE’S LETTER

_____

Some Sage Reflections on

Georgia Cayvan’s Art.

_____

SHE FAILED IN “SQUIRE KATE.”

_____

Mr. Buchanan’s Play Required a Woman

Who Could Change from a Sensible

Sweetheart to a Tearing Termagant at

the Drop of the Hat

NEW YORK, Jan. 27.—Miss Georgia Cayvan is the favorite actress at the Lyceum theater. She is a round faced, buxom woman of perhaps thirty. Her style of acting is of the quiet, demurely dignified order when she is at her best. She strikes you as a woman of strong personality, prim views and considerable intelligence. She is not as handsome as Mrs. Kendal was twenty years ago, when London fell in love with Madge Robertson, but her manner reminds you of that actress at times. It is less in the similarity of appearance than in similarity of temperament. Neither of them wears the actress’ trade mark—that indefinite, but always perceptible prononce air. They fit the domestic scenes easily and gracefully, and to see them at their best one must see them as happy wives, not as adventuresses or flirts or coquettes or courtesans.

Mrs. Kendal has charmed the American public by her drawing room romances. She seemed to have washed and bleached each one of them until there wasn’t a stain of carnality on them. They accepted her as the exemplar of the safe drama “that cheered but could not inebriate.”

I think Miss Georgia Cayvan was built for the same kind of work. When therefore Mr. Frohman put her into the new play called “Squire Kate” and gave her a role in which she had to be unnatural, unreasonable, vituperative and even vulgar, she signally failed.

Nobody appeared to have looked deep enough into the matter to see that Mr. Frohman’ loss was her gain, and that for the actress to fail was for the woman to triumph.

The play is an anomalous combination of exquisite rustic scenery and dramatic fustian. The most ridiculous things are done with sentimental seriousness and the absurdest actions take place amid the most delightful surroundings.

We are introduced to Squire Kate in her own kitchen, one of those old English kitchens which Mr. Frohman delights to reproduce to its minutest detail. She moves about among her yokels the kindly but dignified young mistress, who has had the responsibility of the farm suddenly put upon her and who has been accustomed to take her share of the work uncomplainingly.

You can picture the bright group for yourself—the men at the deal table under the smoky rafters drinking their home brewed ale and chaffing the maids; the overseer, who is in love with Kate, leaning against the great chimneypiece, moody and reticent as his eye follows the mistress in her bustling duties, and now and then whittling his buckthorn stick; the younger sister, who comes in like a moth, very sweet and innocent, as Miss Effie Shannon always makes younger sisters, and eats the plums while the squire makes the pudding. You can see the hedgerows through the broad, open casement and almost hear the lark singing. It is a delicious picture of English rustic life in its best estate. It might have been tinted by Jane Austin or sketched by Charles Reade.

But what is the story that evolves itself on this serene and sunny canvas?

Let me tell you as briefly as I can.

Squire Kate is heavily in debt. The farm is encumbered and there is a miserly old screw in the neighborhood who holds her in his relentless grip, and is determined to ruin her. He has a son, a rather manly young fellow, who is deeply in love with the younger sister, and who is disgusted with his father’s sordid spirit. Squire Kate is not aware of this attachment. She not only loves her sister tenderly, but she also consciously loves the young man. All at once another old miser somewhere dies and leaves all his wealth to Kate. She pays off the indebtedness on the farm and is herself a wealthy woman. We are now at the end of the first act, and the lark sings with redoubled energy.

We then proceed to the English hayfield, where Squire Kate in a French dress superintends the hayraking and is beset by an opera bouffe quartet of suitors. Among them is the Old Screw, who, now that she is wealthy, is anxious to have her marry his son and tells her that the son loves her, to her soul’s delight. But presently she discovers that it is false and that the young man loves her sister. And at that point the play goes all to pieces in theatric hysterics and inconceivable mumbo-jumbo.

In an instant the squire is converted from a wholesome, levelheaded housewife and prudent woman into an irresponsible and vituperative stage hussy. As soon as she gets the facts into her mind she hates her innocent sister, declares herself an enemy of the world and rants and raves unrestrainedly about her unreciprocated affection, and rushes off in the night to an old Polonius shepherd in a lonely wood to get a love philter or some mandragora to fix things up to her liking.

The most romantic of maiden observers of this catastrophe feels at once that the bottom has fallen out of the English picnic and that the spilled contents are cheap melodrama. One feels a little sorry that the wholesome Squire Kate should so quickly resolve herself into a superstitious lovelorn maiden of the Middle Ages. There is a strong desire in the human breast that she shall go on making pudding and raking the hay and behave herself. But no, she not only insists that the world is a soap bubble and her doll is stuffed with sawdust, but she proposes to declaim it in spite of decency and at the slightest provocation.

Mr. Buchanan, the author of this play, appears to think that the average heroine of the century doesn’t draw much of a line between serenely loving and severely hating. She either wears ashes of roses or oil of vitriol as the mood seizes her, and if she can’t have her own sweet way with her emotions, she becomes in the twinkling of an eye a confirmed nihilist. Her creed is devotion or dynamite. Beware, and love me!

Then Mr. Buchanan having got himself into this conscienceless human muddle, in which decorum resolves itself into drugs and character drops to inconsistency, sets himself to work to show that all this inconceivable nonsense on the part of Kate is a purely feminine spasm that is to be cured by a counter shock.

The counter shock is this, and mark how narrow and theatric it is:

The old miser, who is so anxious to have his son marry Kate’s farm, perceives that he never will so long as the pretty sister is in the way, so he goes to the same old Polonius in the dusky wood and gets some poisonous distillment, “gathered in the full of the moon.” His plea is that he wants to kill a troublesome dog and the shepherd, who keeps these poisons handy in his hut, furnishes the venom with many sage Shakespearean reflections and no compunctions, and the ruthless old bird of prey goes immediately and gives it to the pretty sister, with proper Macbeth accompaniments.

As soon as the innocent is brought to death’s door Squire Kate considers. “Hullo,” she says, “I love my sister, now that she is going to die. I’ve made a mistake. The best thing to do is to repent and stick to Yorkshire pudding and marry that chump of an overseer who has been mooning around here for five years.”

And that, oh, my theatrical brethren, is the happy ending of the play.

It violates the first principles of Goody Two Shoes. It presents a woman to us as a theatrical hit or miss dispenser of effects.

Well, you can fancy how the demure Miss Cayvan went through with the hysterics. It was like a Quakeress tooting for a sideshow. She tried to do what she didn’t believe in; that is, she screamed about her unrequited love and hurled anathemas at her innocent sister, and altogether tried to behave to the best of her ability like a very unreasonable and somewhat disreputable creature and failed.

She hasn’t got the headlongness for this sort of thing. She is too self conscious.

You can’t look into her round, unemotional face without feeling her soul’s conviction settling around her broad, firm mouth; and it is that twice two make four, and be hanged to Mr. Buchanan. Women who can make a Yorkshire pudding as deftly as she does do not love self sacrificingly up to 3:42 and then hate fiendishly till 7:30. They do not keep their feelings in a necromancer’s bottle, to turn out milk or Medford rum, as the playwright indicates.

And for that very reason, perhaps, they are not good actresses, as actresses go.

Who knows?

NYM CRINKLE.

___

The Era (13 August, 1892)

THE Leo Hunters of San Francisco thought recently they had captured Mr Robert Buchanan, and felt exceedingly foolish when they discovered that they had been wasting their enthusiasm over a prosaic English trader without even a spark of poetry in his bosom. Mr Robert Buchanan is at present enjoying the sea-breezes at a certain popular resort on the Kentish coast. Next season he will make his first experiment in comic opera, and will also give his London admirers an opportunity to see Squire Kate, already produced by Mr Frohman in New York. Mr Buchanan has written a piece for Mr Sothern, and it has gone out with the manager named. He is also completing another play ordered for the New York Lyceum; he has been commissioned by Mr Palmer to prepare an English adaptation of L’Ainé, in which Mr Willard will appear, and he is hoping soon to complete a contract with Mr Beerbohm Tree for a new piece at the Haymarket.

___

The Saint Paul Daily Globe (18 September, 1892 - p.20)

CHICAGO LETTER.

_____

Breezy Gossip of the Stage in the Windy City.

Special Correspondence of the Globe.

CHICAGO, Sept. 16.—

. . .

The only important event announced for the coming week will be the first performance in Chicago by Daniel Frohman’s Lyceum Theater company of “Squire Kate,” by Robert Buchanan. While confessing that he received part of the story from a French source, he has made this play almost entirely from a dramatization of his novel, “Come Live With Me and Be My Love.” The plot of the play can hardly be better presented than in a charming little poem, which Mr. Buchanan has written for the purpose, upon the play’s first production. Each verse, representing an act, runs as follows:

ACT I.

There grew two roses in the light,

Hey the winds and the weather;

And one was red and one was white,

And they shone in the sun together.

—Old Song.

ACT II.

Cold and chill the east wind blew,

Hey the wind and the weather;

And the roses drooped in the rain and the dew.

And saddened both together.

ACT III.

The red rose wept with a bitter pain,

Hey the wind and the weather;

And there came a storm which tore in twain

The roses that grew together.

ACT IV.

Sunlight comes when the storm has fled,

Hey the wind and the weather;

The white’s still white and the red’s still red,

And they bloom in the sun together.

As a poet and novelist Robert Buchanan gained his reputation with the British public; and it was some time thereafter that he turned his attention to dramatic work. In his younger days he was a great friend of Thomas Carlyle, being a neighbor of his in Edinburgh. It was Carlyle who advised young Buchanan to go to London, and seek success in the field of literature. He went, and, like all penniless young writers, had to fight that hard battle for fame which has been continually waged in the big, smoky metropolis from the time of Johnson and Goldsmith to the present day. But fame is more remunerative in this world’s fair year than it was in the past, as has been shown by the success of Jerome K. Jerome and others. Robert Buchanan is now probably forty-eight years old, and enjoys a large income coming entirely from literature.

___

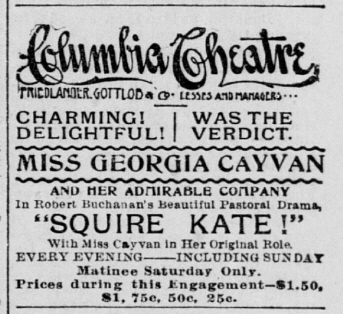

The New York Times (18 October, 1896)

The new theatrical incidents of this week will be the opening of Frank Murtha’s Murray Hill Theatre, at Forty-second Street and Lexington Avenue; the production of a new Irish operetta at the Broadway Theatre, which has been closed since “The Caliph” suddenly vanished, and the revival at Palmer’s, by Georgia Cayvan, of “Squire Kate,” a drama of rustic life, by Robert Buchanan, in which her acting was greatly admired at the Lyceum Theatre.

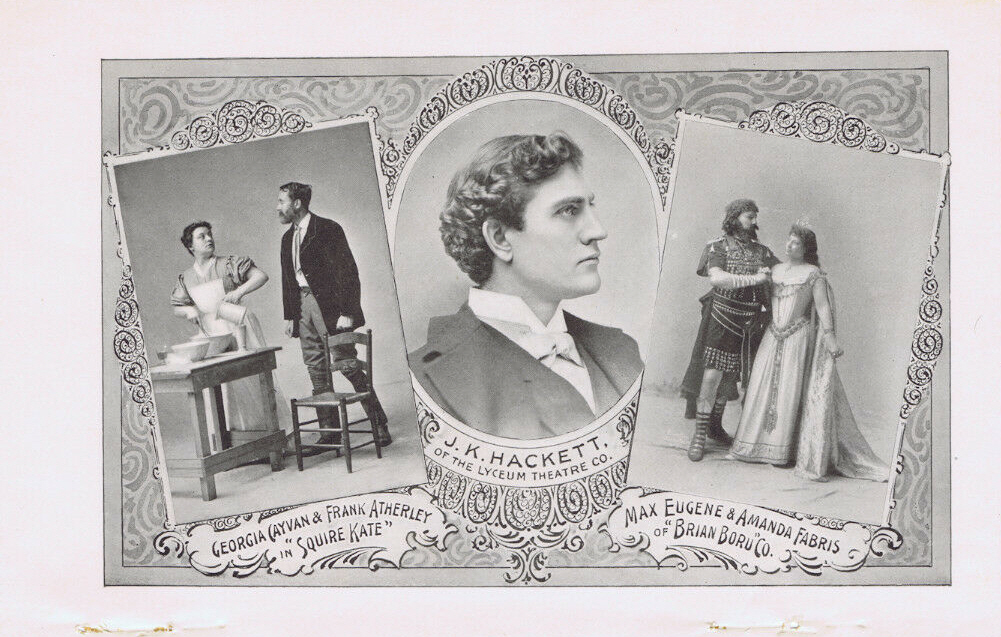

“Squire Kate,” is founded on a French drama called “La Fermiere.” Miss Cayvan has somewhat reduced its text and omitted two scenes. The play will now be presented in four acts, the scene of the first and fourth being Kate’s farmhouse, and that of the second and third the harvest field. New scenery has been painted, and great pains have been taken with the ensemble. The harvest merry-making will be elaborately represented. George Woodward will have the rôle of the miser, and other prominent parts will be taken by Frank Atherley, Orrin Johnson, Florence Conron, and Annie Sutherland.

___

The Era (31 October, 1896 - p.13)

“MARY PENNINGTON, SPINSTER,” has been withdrawn at Palmer’s, and was succeeded by an elaborate revival of Mr Robert Buchanan’s Squire Kate. Some changes have been made to suit the purpose of the star, Miss Georgia Cayvan, who played the heroine. The scene preceding the last act has been eliminated bodily, and various portions of the dialogue have been revised, not quite so thoroughly at certain points as is, perhaps, desirable. Miss Cayvan made a distinctly good impression in the strong scene which occurs between the heroine and her sister at the close of the third act. But notwithstanding all her efforts, ably seconded by those of Miss Florence Conron, Mr Orrin Johnson, and others, Miss Cayvan may find it difficult to run the play to profitable business long. According to the Palmer’s Theatre programmes Squire Kate will shortly be followed by a comedy-drama temporarily christened Marjory. Should this piece not be ready for production when required a light comedy, by Miss Elizabeth Bisland, entitled Goblin Castle, may precede it.

___

Brooklyn Eagle (1 November, 1896 - p.24)

Georgia Cayvan has proved herself one of the best actresses in America. Her appearance as a star has been clearly enough foreseen during her long service with the Lyceum stock company, and many of her admirers will be glad of an opportunity to welcome her in a field which will give a wider scope to the powers which the actress has often indicated, but has not yet fully displayed. The opportunity will come this week at the Park Theater, where Miss Cayvan will make her first appearance in Brooklyn as a nominal star. Almost exactly four years ago Robert Buchanan’s pastoral drama, “Squire Kate,” was seen for the first time in this city, being played by the Lyceum theater company, with Miss Cayvan as Kate. It returns to the Park theater now, when it will be presented by Miss Cayvan and her newly organized company. In the interim it has, however, been in large part rewritten, its incidents have been rearranged, and the critics of New York, where Miss Cayvan has been presenting it during the final two weeks of her engagement at Palmer’s theater, say that it has been vastly improved. “Squire Kate” is a story of English country life, and it breathes the freshness of the fields and the wholesomeness of rusticity. It tells a love story and tells it in a manner which compels sympathy and interest to the very last. Catherine Thorpe loves George Heathcote, but of this he suspects nothing, for he himself loves Catherine’s little sister, Hetty, whom Catherine has reared and been a mother to. The story is a struggle between Kate’s love for her sister and for her lover. The knot is cut by the poisoning of Hetty, and the plot complicated by the suspicion which falls for a time upon Kate. But the little sister is saved and Catherine is fully cleared, after which the story has a pleasant but unconventional ending. Miss Cayvan’s manager has staged the play well, the scenery having been painted by Mr. Homer Emens and the production being under the stage direction of Mr. Napier Lothian, jr. The company, too, is good. It includes Miss Anne Sutherland, Miss Florence Conron, Miss Winifred McCaull, Miss Mary Jerrold, Miss Kate Ten Eyck, Miss Louise Palmer, Messrs. George Woodward, Frank Atherley, Orrin Johnson, William Herbert, Albert Brown, Lionel Barrymore, Thomas Bridgeland and Charles Thropp. The engagement at the Park is for one week only.

___

Brooklyn Eagle (3 November, 1896 - p.9)

TWO STRONG ACTRESSES.

_____

GEORGIA CAYVAN AND OLGA

NETHERSOLE IN TOWN.

The American Star in “Squire Kate” and

the English Woman in a Strong Repertory,

Beginning with Denise—Chevalier at the Columbia

_____

If the rest of Georgia Cayvan’s starring tour moves as auspiciously as its opening at the Park Theater last night, she need have no misgivings that her place among the peripatetic actresses of America is assured for some years to come. Miss Cayvan has long been admired as the leading woman of the Lyceum company in new York, and it is inevitable that a good leading actor sooner or later starts out on his or her own account, taking the gambler’s hazard of the receipts at the door with the financial worry involved, in lieu of the comfortable salary and artistic freedom which the head of a stock company gives. But there is always more or less uncertainty about the success of the venture. Rose Coghlan, for instance, has not won the success which her merits as an actress deserved, and most people familiar with the theater can fill out a list of actors who would be better off if they had never left the ranks. Appearances last night indicated that Miss Cayvan’s was to be one of the successful experiments. If she has as many friends in other cities as in Brooklyn and if her stock of interesting plays holds out, there can be little question about the result. The Park was filled as Brooklyn theaters are filled only a few times during the season, there were four curtain calls after the third act and an emotion after the fourth and final scene which did not materialize in applause, chiefly because the pathos was too keen. The play was Robert Buchanan’s “Squire Kate,” which suggests Hardy’s novel, “Far From the Madding Crowd,” so sharply that the dramatist has time and time again been accused of borrowing the novel and has as often denied it until now his play is officially traced to a French original. Its spirit is thoroughly English, however, and remains so now that the play has been extensively altered. The melodramatic scenes have been cut out by Napier Lothian, jr., leaving a consistent pastoral drama which turns upon the love of Kate and her petted younger sister, Hetty, for the same man, and the sacrifice of Kate when she finds that George loves Hetty. A trace of melodrama remains in the attempt to poison Hetty by George’s miserly step-father, Gaffer Kingsley, but the attempt fails and is chiefly important because it brings George and Hetty nearer together, nerves Kate for her sacrifice and leads to a hint of her future happiness with Geoffrey, the faithful overseer who has loved her since her girlhood. This outline conveys little idea of the strength of the play, which comes from clearly drawn and faithfully realized characters and from natural and life like scenes. The first two acts are purely pastoral, a farm kitchen and a hay field in which types of rustic character based on those in Hardy’s novels are presented and which have something of the bucolic flavor of “The Old Homestead” and “Shore Acres,” though for Americans they lack the vividness of familiarity. In these two acts the comedy characters are prominent and Miss Cayvan is not particularly convincing. At the end of them, however, George has proposed to Hetty and his miserly old step-father, having guessed Kate’s love for him, has proposed in George’s name and won an acknowledgment from Kate that she loves and will marry his step-son. The last two acts are tense and rapid. First, Kate sees George and Hetty love making and is half crazed with grief. In her frenzy she turns upon Hetty, accuses her of trickery and orders her from the house. That is an intense and stirring scene and Miss Cayvan played it like a whirlwind last night, winning four curtain calls for her fiery denunciations of her sister and her sister’s lover. It was powerful acting of a school that has somewhat gone by. One may doubt if Miss Cayvan were still in a stock company whether she would have played it so violently. More repose would have been better art. But there is no question of the theatrical effectiveness of the scene. The actress caught the house and the four curtain calls, which were the high water mark of enthusiasm rewarded this scene. In the fourth act Miss Cayvan’s manner changed and she abundantly satisfied the lovers of quiet and naturalness. Hetty is supposed to be dying of poison and circumstances tend to throw suspicion upon Kate. The horror of such a suspicion kills the woman’s hate of her sister and rouses her better nature to the sacrifice which shall restore Hetty to the arms of the man they both love. In that situation Miss Cayvan acted with all the intellectual insight, the subtlety, delicacy and truth which have marked her performances of less exacting parts, and with the power which has at various times led her admirers to believe that she was intended by nature for the Jocastas and Lady Macbeths rather than for the drawing room style of drama, in which she is most familiar. It was beautiful, natural, true and poignantly pathetic. There are not four actresses on the American stage who could have done it so well. The company which supports Miss Cayvan is above the average of star companies. George Woodward played Gaffer Kingsley with a humor and power which won prompt recognition, and other parts were well filled by Orrin Johnson, Frank Atherly, William Herbert, Albert Brown, Charles Thropp, Florence Conron and Anne Sutherland. Special interest attached to the appearance of Lionel Barrymore, a young son of Maurice Barrymore. He has only been on the stage for three or four weeks, but his sketch of Lord Silversnake had the firmness and ease of a veteran, and it showed a touch of humor which may indicate a coming character comedian. The settings were about as good as they could have been if Miss Cayvan were still under the management of the Lyceum theater. The real hay had the pungency of the meadows and the scenes were solidly and well painted. Next week, “The Lilliputians.”

___

The Boston Daily Globe (26 January, 1897 - p.4)

DRAMA AND MUSIC.

_____

Miss Cayvan’s Debut as a

Star in Boston.

_____

. . .

TREMONT THEATER—“Squire Kate,” a pastoral drama in four acts, by Robert Buchanan. The cast:

Gaffer Kingsley . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Mr George Woodward

Jeoffrey Doone . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Mr Frank Atherley

George Heathcote . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Mr Orrin Johnson

Jasper Arundel . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Mr William Herbert

Mr Nash . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Mr Albert Brown

Lord Silversnake . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Mr Lionel Barrymore

Dr Dutton . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Mr Thomas Bridgeland

Jabez . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Mr Charles Thropp

Catherine Thorpe . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Miss Georgia Cayvan

Hetty Thorpe . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Miss Florence Conron

Amanda Jane Thistledown . . . . . . . . . . . Miss Annie Sutherland

Nancy . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Miss Winifred McCaull

Deborah . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Miss Mary Jerrold

Susan . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Miss Kate Ten Eyck

Mary . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Miss Louise Palmer

Thomas . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Mr Joseph Henry

Silas . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Mr Henry Howe

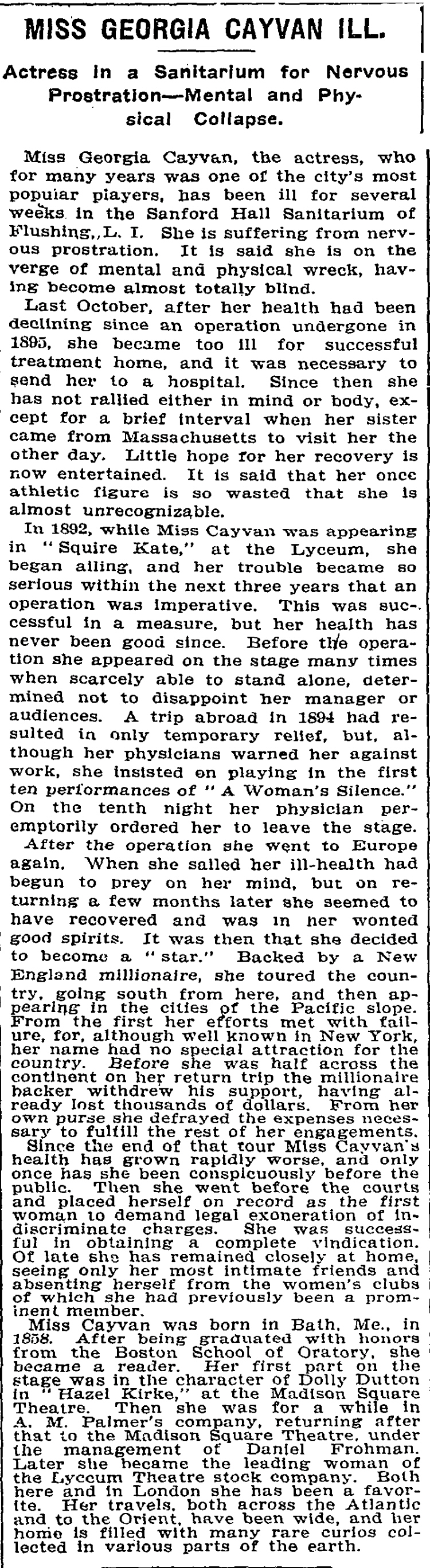

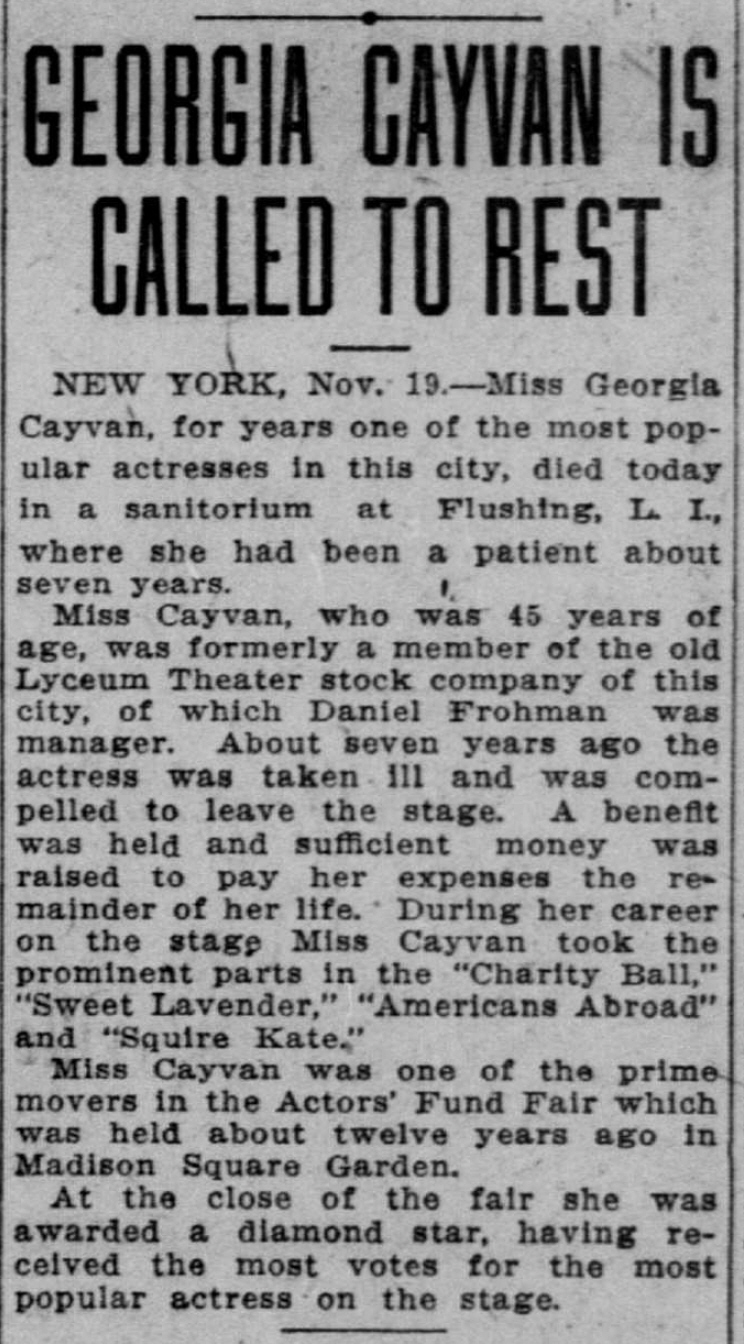

Miss Georgia Cayvan came to Boston as a star last evening and received cordial greetings from a crowd of friends gathered in the Tremont theater.

This charming woman and talented actress has long been a favorite here, and deservedly so. Few actresses have worked more earnestly for legitimate success, and few have to their credit a longer list of honorable achievements.

As the leading lady of Daniel Frohman’s Lyceum theater company she has endeared herself to playgoers throughout the country, and all will surely unite in heartily wishing her a prosperous career as a star. But good will alone is not sufficient to insure success in stellar roles: there must be individuality, adaptability and talent far above the commonplace.

That Miss Cayvan is equipped with all that is requisite for winning distinguished recognition as the leading member of a “stock” company has been amply proven, but it remains to be seen whether she will be equal to requirements in her new line of work.

She has been absent from the stage for two years, seeking good health and new plays. The former has evidently been found, for she was never more wholesome and robust in appearance, but her quest for plays seems to have been unrewarded.

It is a pity that she should have decided to begin her starring tour unequipped with plays worthy of her best efforts. First impressions count for much, and it must be frankly said that the friendly audience assembled in her honor last evening was very much disappointed.

She presented Robert Buchanan’s badly constructed comedy-melodrama, “Squire Kate,” a play that never was and probably never will be a success. It was presented here in September, 1892, with Miss Cayvan, then as now, in the title role.

Some of the dialogue has been rewritten and several of the situations have been changed, all for the better, no doubt, but the opinion regarding the play originally expressed in these columns remains unaltered.

The story is that of a woman who bravely takes on herself the care of a debt-laden farm and the care of a young sister, and struggles on, aided only by the loyalty of her overseer, whom she prizes as her friend, but who is hopelessly her lover. She herself loves the stepson of a neighboring miser, but he, never dreaming of such a state of affairs, has eyes and thought only for her fair young sister.

A timely bequest relieves her of her difficulties; she is made to believe that the man she loves has asked her hand, and her happiness is complete, only to be ruined by the sudden discovery of the truth. The sudden peril of the sister brings the two together again, and the play closes with the lovers united, and a gleam of hope lightening the cloud resting on the heavy hearth of Kate and her single-hearted lover.

This mass of melodramatic material has not been cleverly handled by the author. His work is never convincing, all seems unreal and improbable. He begins by sketching a noble character for his central figure and then proceeds to humiliate it in every possible way. The right kind of sympathy cannot be won for a character thus developed. The greatest actress in the world could not make a success of “Squire Kate.”

Miss Cayvan’s impersonation last evening was, so far as memory serves, practically the same characterization presented here four years ago. To expect anything better would be unreasonable. The opportunities are too limited. We must see her in other roles before attempting to express an opinion regarding her advancement in the dramatic art.

Her impersonation of Squire Kate is quite as good as the character deserves. She realizes the creation as suggested by the author’s lines. She is most agreeable in the first act and in the succeeding quiet scenes, but the greatest applause is won for the hysterical ending of the third act when the squire curses her little sister as long and as loudly as strength will permit, and then falls exhausted to the stage. There were five curtain calls last night.

An excellent supporting company surrounds Miss Cayvan. It is, of course, not equal to the old Lyceum company, but is quite satisfactory, and much above in merit the support selected by the average star.

Mr Woodward gives a rather exaggerated, but on the whole effective, impersonation of the old miser; Mr Atherley makes the most of his opportunities as the farm overseer; Mr Johnson is natural and manly as the young lover, whose misunderstood affection caused all the trouble. Mr Herbert is really capital as the shepherd, who dealt in love potions, and Mr Lionel Barrymore, son of a distinguished father, contributes a clever character study of a fragile lordling.

Miss Florence Conron is a winsomely feminine little woman, whose voice and style of acting suggests Annie Russell, without, however, the convincing sincerity of the latter, portrays the role of the younger sister with agreeable effect. Miss Annie Sutherland, who is pleasantly remembered here in operatic extravaganza, plays a delightful impersonation of a merry hay-making matron. The play is elaborately mounted and several of the settings are notable for realistic effect.

“Squire Kate” will be presented at every performance this week. For the second and last week of Miss Cayvan’s engagement at the Tremont the following repertory is announced: Monday, Tuesday, Wednesday and Thursday evenings and Wednesday matinee, a new play by W. R. Walkes, entitled “Mary Pennington, Spinster,” and for Friday and Saturday evenings and Saturday matinee a special double bill consisting of a new comedy, entitled “Goblin Castle,” by Miss Elizabeth Bisland, and a comedietta, “The Little Individual,” in both of which Miss Cayvan will appear.

|