ROBERT WILLIAMS BUCHANAN (1841 - 1901)

|

ROBERT WILLIAMS BUCHANAN (1841 - 1901) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

BALLAD STORIES OF THE AFFECTIONS From the Scandinavian |

|

|

|

|

BALLAD STORIES OF THE AFFECTIONS.

FROM THE SCANDINAVIAN.

BY ROBERT BUCHANAN.

WITH ILLUSTRATIONS BY G. J. PINWELL W. SMALL A. B. HOUGHTON ENGRAVED BY THE BROTHERS DALZIEL.

LONDON: GEORGE ROUTLEDGE & SONS. BROADWAY, LUDGATE HILL.

PREFACE.

TRANSMITTED, in the same manner as the Scottish and Breton ballads, as a precious heritage from father to son, the old ballads of Scandinavia were preserved by popular recitation. With all their contradictions and inconsistencies, they are national—no ballads more so—distinguishable from the Scottish writings of the same class, although possessing many delicate points of similarity. As for the themes, some are of German and others of Southern origin, while many are chiefly Scandinavian. The adventurers who swept southward langsyne, to range themselves under the banners of strange chiefs, not seldom returned home brimful of wild exaggerated stories, to beguile many a winter night; and these stories in course of time became so imbedded in popular tradition, that it was difficult to guess whence they primarily came, and gathered so much moss of the soil in the process of rolling down the years, that their foreign colour soon faded into the sombre greys of Northern poesy. Travellers flocking northward in the middle ages added to the stock, bringing subtle delicacies from Germany, and fervid tendernesses from Italy and Spain. But much emanated from the North itself—from the storm-tost shores of Denmark, and from the wild realm of the eternal snow and midnight sun. There were heroes and giants breasting the Dovre Fjord, as well as striding over the Adriatic. Certain shapes there were which loved the sea-surrounded little nation only. The Lindorm, hugest of serpents, crawled near Verona; but the Valrafn, or Raven of Battle, loved the swell and roar of the fierce North Sea. The Dragon ranged as far south as Syria; but the Ocean-sprite iv liked cold waters, and flashed, icy bearded, through the rack and cloud of storm. In the Scottish ballad we find the Kelpie, but search in vain for the Mermaid. In the Breton ballad we see the ‘Korrigaun,’ seated with wild eyes by the side of the wayside well, but hear little of the mountain-loving Trolds and Elves. It is in supernatural conceptions, indeed, in the creation of typical spirits to represent certain ever-present operations of Nature, that the Danish ballads excel—being equalled in that respect only by the German Lieder, with which they have so very much in common. They seldom or never quite reach the rugged force of language shown in such Breton pieces as ‘Jannedik Flamm’ and the wild early battle-song. They are never so refinedly tender as the best Scottish pieces. We have to search in them in vain for the exquisite melody of the last portion of ‘Fair Annie of Lochryan,’ or for the pathetic and picturesque loveliness of ‘Clerk Saunders,’ in those exquisite lines after the murder— ‘Clerk Saunders he started, and Margaret she turned ‘And they lay still, and sleepèd sound, ‘But he lay still and sleepèd sound, But they have a truth and force of their own which stamp them as genuine poetry. In the mass, they might be described as a rough compromise of language with painfully vivid imagination. Nothing can be finer than the stories they contain, or more dramatic than the situations these stories entail; but no attempt is made to polish the v expression or refine the imagery. They give one an impression of intense earnestness—of a habit of mind at once reticent and shadowed with the strangest mysteries. That the teller believes heart and soul in the tale he is going to tell, is again and again proved by his dashing, at the very beginning of his narrative, into the catastrophe— ‘It was the young Herr Haagen, And all because he would not listen to the warnings of a mermaid, but deliberately cut her head off. There is no such pausing, no such description, as would infer a doubt of the reality of any folk in the story. The point is, not to convey the fact that sea- maidens exist, a truth of which every listener is aware, but to prove the folly of disregarding their advice when they warn us against going to sea in bad weather. ‘In nova fert Animus mutatas dicere formas might be the motto of any future translator of these pieces. How the Bear of Dalby turned out to be a King’s son; how Werner the Raven, through drinking the blood of a little child, changed into the fairest knight the eye of man could see; how an ugly serpent changed in the same way, and all by means of a pretty kiss from fair little Signe. But there are other and finer kinds of supernatural manifestation. The Elves flit on ‘Elfer Hill,’ and slay the young men; they dance in the grove by moonlight, and the daughter of the Elf King sends Herr Oluf home, a dying man, to his bride. The ballad in which the latter event occurs, bears, by the way, a striking resemblance to the Breton ballad of the ‘Korrigaun.’ The dead rise. A corpse accosts a horseman who is resting by a well, and makes him swear to avenge his death; and, late at night, tormented by the sin of having robbed two fatherless bairns, rides a weary ghost; the refrain concerning whom has been reported verbatim, for no earthly purpose, by Longfellow, in his ‘Saga of King Oluf:’— ‘Dead rides Sir Morten of Foglesang!’ The Trolds of the mountain besiege a peasant’s house, and the least of them all insists on having the peasant’s wife; but the catastrophe is a transformation—a prince’s son. ‘The Deceitful Merman’ beguiles Marstig’s daughter to her death, and the piece in which he does so is interesting as being the original of Goethe’s ‘Fisher.’* Another ballad, ‘Agnete and the Merman,’ begins— ‘On the high tower Agnete is pacing slow,

* Goethe found the poem translated in Herder’s ‘Volkslieder.’

vii ‘Agnete! Agnete!’ he cries, ‘wilt thou be my true-love—my all-dearest?’ ‘Yea, if thou takest me with thee to the bottom of the sea.’ They dwell together eight years, and have seven sons. One day, Agnete, as she sits singing under the blue water, ‘hears the clocks of England clang,’ and straightway asks and receives permission to go on shore to church. She meets her mother at the church-door. ‘Where hast thou been these eight years, my daughter?’ ‘I have been at the bottom of the sea,’ replies Agnete, ‘and have seven sons by the Merman.’ The Merman follows her into the church, and all the small images turn away their eyes from him. ‘Hearken, Agnete! thy small bairns are crying for thee.’ ‘Let them cry as long as they will;—I shall not return to them.’ And the cruel one cannot be persuaded to go back. This pathetic story, so capable of poetic treatment, has been exquisitely paraphrased by Oehlenschläger, whose poem I have here translated in preference to the original. The Danish Mermen, by the way, seem to have been good fellows, and badly used. One Rosmer Harmand does many kindly acts, but is rewarded with base ingratitude by everybody. The tale of Rosmer bears a close resemblance to the romance of Childe Rowland, quoted by Edgar in ‘Lear.’

* Robert Jamieson, who, among his ‘Popular Ballads,’ published in 1806, gave five from the Danish, rendered with a rugged picturesqueness transcending the best efforts in that direction of Scott himself. This Jamieson was a veritable singer, and struck some fine chords from a Scotch harp of his own. _____

ix

Page INDUCTION: THE SUNKEN CITY F. L. Höedt 1 EVEN-SONG Christian Juul 5 SIGNELIL THE SERVING-MAIDEN Antique 6 THE SOLDIER Eric Bögh 11 THE CHILDREN IN THE MOON Oehlenschläger 12 HELGA AND HILDEBRAND Antique 16 THE WEE, WEE GNOME Antique 21 THE TWO SISTERS Antique 28 EBBE SKAMMELSON Antique 32 MAID METTELIL Antique 45 THE OWL P. L. Möller 50 THE ELF DANCE Antique 52 THE LOVER’S STRATAGEM Antique 56 THE BONNIE GROOM Antique 63 CLOISTER ROBBING Antique 68 x AGNES Oehlenschläger 76 HOW SIR TONNE WON HIS BRIDE Antique 84 SIR MORTEN OF FOGELSONG Antique 97 THE LEAD-MELTING Claudius Rosenhoff 100 YOUNG AXELVOLD Antique 103 THE JOINER Claudius Rosenhoff 111 AAGE AND ELSIE Antique 112 AXEL AND WALBORG; OR, THE COUSINS Antique 117 THE BLUE COLOUR Claudius Rosenhoff 158 THE ROSE Claudius Rosenhoff 159 LITTLE CHRISTINA’S DANCE Antique 160 THE TREASURE-SEEKER Oehlenschläger 166 SIGNE AT THE WAKE Antique 171 xi LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS.

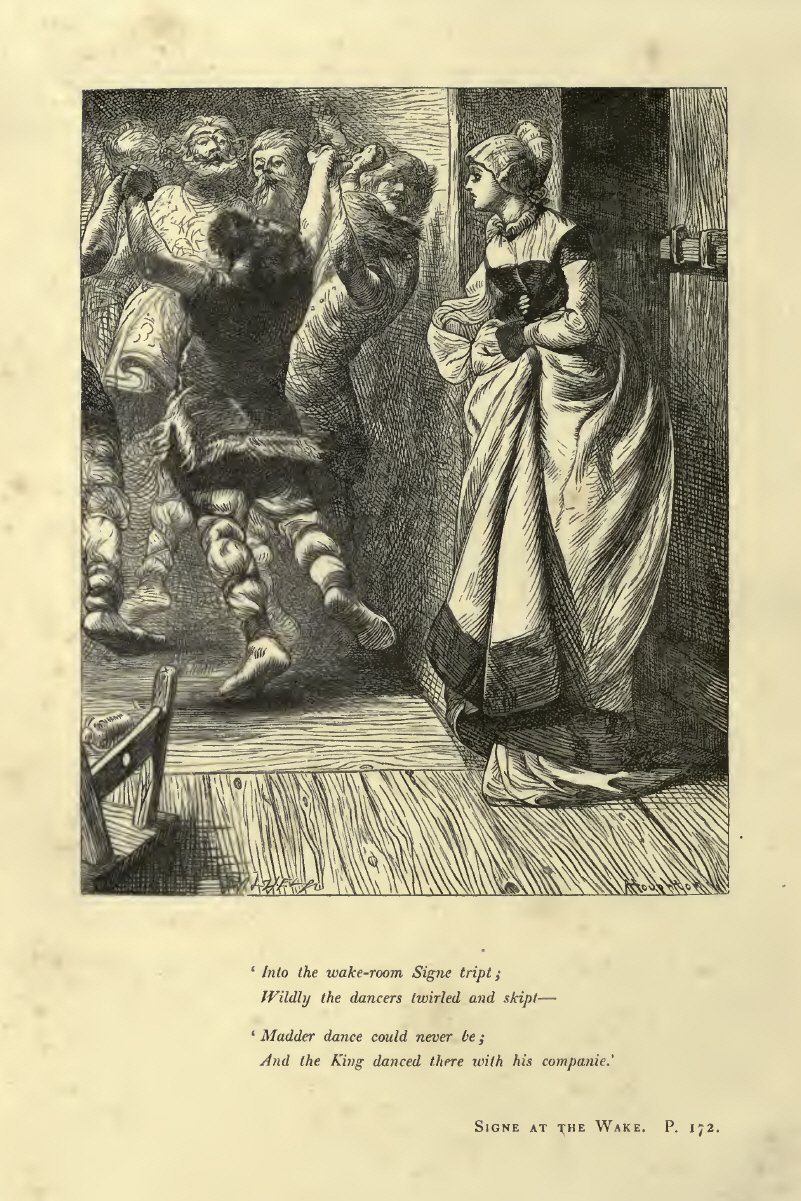

Subject. Artist. Page INDUCTION: THE SUNKEN CITY. ‘But go there, lonely, SIGNELIL THE SERVING-MAIDEN. ‘“My son hath plighted his troth to thee, ‘“Thou art my dearest, thou art my bride, THE CHILDREN IN THE MOON. ‘To the wayside well they trotted, HELGA AND HILDEBRAND ‘“My seam is wild and my work is mad THE WEE, WEE GNOME xii ‘The wee, wee gnome leapt up and laughed, THE TWO SISTERS. ‘They doff their garb from head to heel.; EBBE SKAMMELSON. ‘“Far better marry Peter, my son, ‘Alone in the wild wood wanders Ebbe Skammelson!’ J. D. WATSON. 43 MAID METTELIL. ‘“Rise up, Sir Oluf, and open the door— THE ELF DANCE. ‘The Elf King’s daughter is featest of all: THE LOVER’S STRATAGEM. ‘Upon her throbbing heart THE BONNIE GROOM. ‘The bonnie groom stands up in court, CLOISTER ROBBING. ‘All silent stood the holy maids, AGNES. ‘Maid Agnes musing sat alone ‘The Little herd-boy drove his geese HOW SIR TONNE WON HIS BRIDE xiii ‘Herr Tonne in the rose grove rode, ‘He slew the bear that watched the door, SIR MORTEN OF FOGELSONG. ‘“Say that my chamber slippers lie THE LEAD-MELTING. ‘They dropt the lead in water clear, YOUNG AXELVOLD. ‘God save thee, foster-mother dear! ‘Fair Ellen clutched her brooch of gold, AAGE AND ELSIE. ‘Home went little Elsie, AXEL AND WALBORG; OR, THE COUSINS. ‘They scattered dice on the golden board, ‘In cloister walls she learns to read, ‘There on the castle balcony, “‘Lord, saddle, saddle ten good steeds, ‘Sir Axel Thorsen sat apart, ‘With eight red wounds upon his breast ‘So sweet Walborg in cloister dwelt LITTLE CHRISTINA’S DANCE. ‘Little Christina, come dance with me, ‘The monarch trembled and tried to speak, THE TREASURE-SEEKER. ‘And bearing spade on shoulder SIGNE AT THE WAKE. ‘Into the wake-room Signe tript;

[Notes: The illustrated edition of Ballad Stories of the Affections: from the Scandinavian was published by George Routledge & Sons in December, 1866. In 1869, a cheap edition, minus the illustrations, was published by Sampson Low, Son, and Marston (London) and Scribner, Welford and Co. (New York). |

|

|||

|

|||

|

The motto on the cover of this edition,"The stretched metre of an antique song" is taken from Shakespeare’s Sonnet 17. Keats also used the line as the epigraph to Endymion: A Poetic Romance (1818). Apart from a few minor changes (‘countree’ in the original edition is replaced by ‘countrie’ in the cheap edition), the text of the poems is substantially the same. The Preface (‘Translator’s Preface’ in the cheap edition) has a few minor changes (‘in genius’ follows ‘distinguishable’ in the second sentence, ‘langsyne’ is replaced by ‘long ago’, and ‘Foglesong’ is corrected) but there is also an additional footnote: * Udvalgte Danske viser fra Middelalderen, efter A. S. Vedels og P. Syvs trykte Udgaver og efter Laandskrevne Samlinger udgivne paa ny af Abrahamson, Myerup, og Rahbek. (Copenhagen, 1812.) Such is the title of the work from which most of the antique ballads here translated have been taken; but numerous other collections—Swedish, Norwegian, and Danish—have been referred to and used. The modern pieces by Oehlenschläger are to be found among his collected poems, in the editions published at Copenhagen. Those by Hoëdt and Bögh are taken from a little miscellaneous collection of verse, edited by Ingemann, and picked up by me for a trifle at a Danish bookstall.—R. B. The Latin quotation, “In nova fert Animus mutatas dicere formas Corpora,” in the Preface is the first line of Ovid’s Metamorphoses - “My mind leads me to tell of forms changed into new bodies ... ”. The November, 1866 edition of The Argosy contained two poems from Ballad Stories of the Affections - ‘Agnes’ by ‘R. B.’ (‘after Oehlenschläger’), ‘The Lead-Melting’ by ‘Robert Buchanan’ (with no indication that it was a translation) - and there was also ‘Convent-Robbing’ by ‘Walter Hutcheson’, which was a complete reworking of the story of ‘Cloister Robbing’. Buchanan also included ‘Agnes’ at his second Reading at the Hanover-Square Rooms on 3rd March, 1869. None of the poems in Ballad Stories of the Affections: from the Scandinavian are included in the 1884 edition of The Poetical Works of Robert Buchanan (although ‘Convent Robbing’ is in the ‘Early Poems’ section). However, one poem, ‘The Lead-Melting’ was included in The New Rome (1898) and was also included in the 1901 edition of The Complete Poetical Works of Robert Buchanan, with no indication that it was a translation of the work of Claudius Rosenhoff. _____

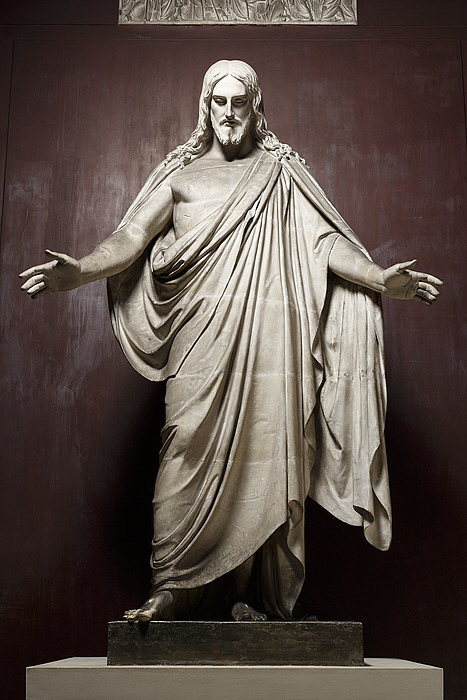

From Chapter IX of Harriett Jay’s biography: “Shortly after his marriage Mr. Buchanan went to Denmark. ‘Being one of the very few Englishmen of that day who knew the Danish language, he went to Schleswig-Holstein towards the end of the war as correspondent of the Morning Star. It was on his return from thence that he wrote so freely on Scandinavian literature, an unknown world to the bookmen of that day.’ (Pearson’s Weekly) He was accompanied on this expedition by his father (who also, I should imagine, went in some official capacity), and during the absence of the pair the young wife went to stay with her mother-in-law, who at that time was living in the neighbourhood of Shepherd’s Bush. It was during that visit to Denmark that he met Hans Christian Andersen; he also visited the famous Thorwaldsen Museum, and was so much impressed by the figures of Christ and the Apostles, that he purchased the one of Christ and brought it home as a present to his wife.” The Second War of Schleswig lasted from February to July 1864. Further details of the conflict are available on wikipedia. The picture below of the sculpture of Christ, which so impressed Buchanan, is from the Thorvaldsen Museum’s website.] |

|

|

Reviews of Ballad Stories of the Affections: from the Scandinavian Back to Poetry

|

|

|

|

|

|

|